Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: Patellofemoral pain (PFP) is one of the most common multifactorial musculoskeletal pathologies affecting the knee joint. The prevalence of PFP in the general population ranges from 11% to 17%, with higher rates observed in specific groups such as females, runners, military personnel, and young athletes. To assess symptoms associated with PFP, the Patellofemoral subscale (KOOS-PF) was developed, consisting of 11 questions that evaluate pain, stiffness, and quality of life. The KOOS-PF scale has already been validated and shown to be reliable in both Spanish and Arabic. Objectives: The aim of this study was to assess the reliability and validity of the KOOS-PF scale in the Greek language among the Greek population with Patellofemoral pain. Methods: Fifty-five participants aged 18-65 years who suffered from PFP were evaluated in two phases on the 1st and 3rd days regarding the reliability and validity of the measures of KOOS-PF in the Greek language. Construct validity was assessed using the Knee Outcome Survey scale - Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADLS). Reliability was measured through Repeated measurements (test-retest) using intraclass coefficient correlation (ICC), standard error (SEM) and smallest detectable change (SDD. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s coefficient a. The significance level was set at 5% (α=0.05). Results: The KOOS-PF measures showed high internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's alpha 0.87, p=0.05) and high test-retest reliability (ICC=0.95, p=0.05, SEM= 3.7, SDC=13.57). Additionally, the Greek version of the KOOS-PF exhibited high construct validity when correlated with the KOS-ADLS scale (r=0.72, p=0.001). Conclusions: The KOOS-PF scale was displayed high reliability and construct validity for measuring Patellofemoral pain in the Greek population.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.2.1. Translation

- Initial translation: A bilingual expert translated the KOOS-PF scale from English to Greek ensuring that the knowledge of medical terminology.

- Back- translated: Another bilingual expert translated the Greek version back into English to check for consistency with the original text.

- Expert Review: A panel of researchers and clinicians reviewed both the Greek and back-translated English versions to ensure that the meaning and context were preserved.

- Pre-testing: The translated questionnaire was administered to a small group of Greek-speaking individuals to assess clarity and relevance.

- 5.

- Final Adjustments: Based on feedback from the pre-testing phase, necessary revisions were made to improve comprehension and cultural appropriateness.

- 6.

- Approval: The final Greek version was submitted to the main authors [13] for approval to ensure fidelity to the original subscale.

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.3.1. Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

2.3.2. Patellofemoral Subscale (KOOS-PF)

2.3.3. Knee Outcome Survey-Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADLS)

2.4. Psychometric Assessment

2.4.1. Reliability

2.4.2. Construct Validity

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Reliability

3.2. Construct Validity

3.3. Structural Validity

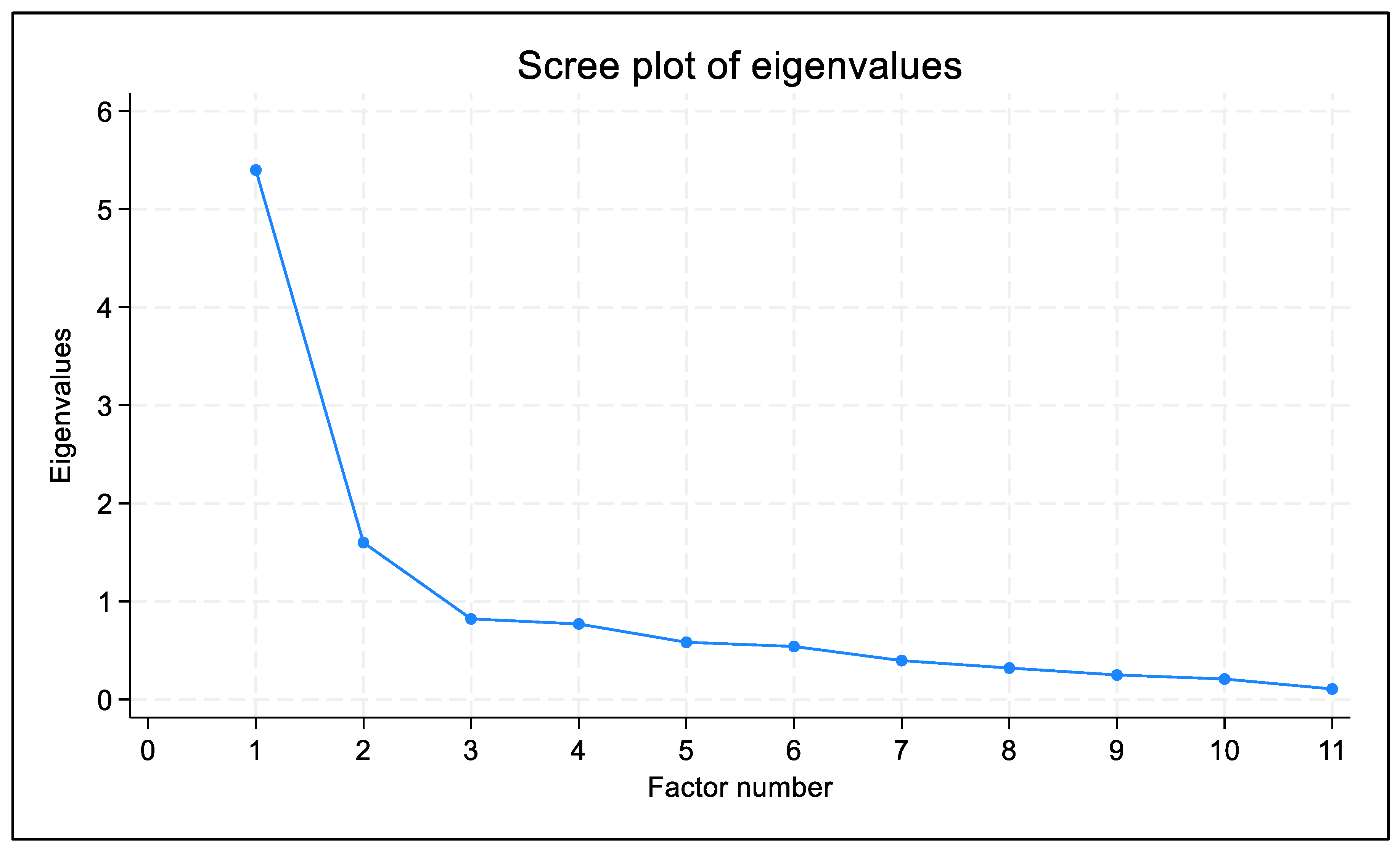

3.4. Factorial Validity

3.5. Floor and Ceiling Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, B.E.; Selfe, J.; Thacker, D.; Hendrick, P.; Bateman, M.; Moffatt, F.; Rathleff, M.S.; Smith, T.O.; Logan, P. Incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crossley, K.M.; van Middelkoop, M.; Callaghan, M.J.; Collins, N.J.; Rathleff, M.S.; Barton, C.J. 2016 Patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester. Part 2: Recommended physical interventions (exercise, taping, bracing, foot orthoses and combined interventions). British journal of sports medicine 2016, 50, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, W.; Ellermann, A.; Gösele-Koppenburg, A.; Best, R.; Rembitzki, I.V.; Brüggemann, G.-P.; Liebau, C. Patellofemoral pain syndrome. Knee surgery sports traumatology arthroscopy 2014, 22, 2264–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bricca, A.; Juhl, C.B.; Steultjens, M.; Wirth, W.; Roos, E.M. Impact of exercise on articular cartilage in people at risk of, or with established, knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. British journal of sports medicine 2019, 53, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallis, J.A.; Roddy, L.; Bottrell, J.; Parslow, S.; Taylor, N.F. A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for physical therapist management of patellofemoral pain. Physical therapy 2021, 101, pzab021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.R.; Teixeira-Salmela, L.F.; Souza, R.B.; Resende, R.A. Hip and knee strengthening is more effective than knee strengthening alone for reducing pain and improving activity in individuals with patellofemoral pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. journal of orthopaedic sports physical therapy 2018, 48, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, C.; Constantinou, A.; Cheimonidou, A.-Z.; Stasinopoulos, D. Greek cultural adaption and validation of the Kujala anterior knee pain scale in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Disability and rehabilitation 2017, 39, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, C.; Nardi, L.; Antoniadou, M.; Stasinopoulos, D. Greek adaptation and validation of the patellofemoral pain syndrome severity scale. Hong Kong Physiotherapy Journal 2013, 31, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, K.M.; Macri, E.M.; Cowan, S.M.; Collins, N.J.; Roos, E.M. The patellofemoral pain and osteoarthritis subscale of the KOOS (KOOS-PF): Development and validation using the COSMIN checklist. British journal of sports medicine 2018, 52, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ateef, M. Measurement properties of the knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score patello-femoral questionnaire in saudi arabians. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cano, J.P.; Vernaza-Obando, D.; Chica, J.; Castro, A.M. Cross-cultural translation and validation of the Spanish version of the patellofemoral pain and osteoarthritis subscale of the KOOS (KOOS-PF). BMC Research Notes 2021, 14, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, E.M.; Roos, H.P.; Lohmander, L.S.; Ekdahl, C.; Beynnon, B.D. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)--development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998, 28, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, D.A.; Lambert, B.S.; Boutris, N.; McCulloch, P.C.; Robbins, A.B.; Moreno, M.R.; Harris, J.D. Validation of digital visual analog scale pain scoring with a traditional paper-based visual analog scale in adults. JAAOS Global Research Reviews 2018, 2, e088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Bot, S.D.; de Boer, M.R.; Van der Windt, D.A.; Knol, D.L.; Dekker, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2007, 60, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heale, R.; Twycross, A. Validity and reliability in quantitative studies. Evidence-based nursing 2015, 18, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapreli, E.; Panelli, G.; Strimpakos, N.; Billis, E.; Zacharopoulos, A.; Athanasopoulos, S. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Greek version of the Knee Outcome Survey–activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADLS). The Knee 2011, 18, 424–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Graaf, V.A.; Wolterbeek, N.; Scholtes, V.A.; Mutsaerts, E.L.; Poolman, R.W. Reliability and validity of the IKDC, KOOS, and WOMAC for patients with meniscal injuries. The American journal of sports medicine 2014, 42, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.H.; Park, Y.-B.; Song, M.-K.; Lim, J.-W.; Lee, H.-J. Reliability and validity of the femorotibial mechanical axis angle in primary total knee arthroplasty: Navigation versus weight bearing or supine whole leg radiographs. Knee surgery related research 2018, 30, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, N.; Saleeb, M.; Gebreal, A.; Ghazy, R.M. The internal reliability and construct validity of the evidence-based practice questionnaire (EBPQ): Evidence from healthcare professionals in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. In Proceedings of the Healthcare, 2023; p. 2168.

- Alfadhel, S.A.; Vennu, V.; Alnahdi, A.H.; Omar, M.T.; Alasmari, S.H.; AlJafri, Z.; Bindawas, S.M. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Saudi Arabic version of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS). Rheumatology international 2018, 38, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthoine, E.; Moret, L.; Regnault, A.; Sébille, V.; Hardouin, J.-B. Sample size used to validate a scale: A review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health and quality of life outcomes 2014, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komorowski, M.; Marshall, D.; Salciccioli, J.; Crutain, Y. Exploratory Data Analysis. 2016; pp. 185–203.

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Research in Science Education 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobak, C.A.; Barr, P.J.; O’Malley, A.J. Estimation of an inter-rater intra-class correlation coefficient that overcomes common assumption violations in the assessment of health measurement scales. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018, 18, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth Analg 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tighe, J.; McManus, I.; Dewhurst, N.G.; Chis, L.; Mucklow, J. The standard error of measurement is a more appropriate measure of quality for postgraduate medical assessments than is reliability: An analysis of MRCP (UK) examinations. BMC medical education 2010, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (1). Restorative dentistry endodontics 2012, 37, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulledge, C.M.; Smith, D.G.; Ziedas, A.; Muh, S.J.; Moutzouros, V.; Makhni, E.C. Floor and ceiling effects, time to completion, and question burden of PROMIS CAT domains among shoulder and knee patients undergoing nonoperative and operative treatment. JBJS Open Access 2019, 4, e0015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, N.; Berduszek, R.; Dijkstra, P.; Sluis, C. Validity and Reliability of the Upper Extremity Work Demands Scale. Journal of occupational rehabilitation 2017, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzhrani, M. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Patellofemoral Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties among Females of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, D.B.; LaBrish, C.; Chalmers, R.P. Old and new ideas for data screening and assumption testing for exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Frontiers in psychology 2012, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Winter, J.C.; Dodou, D. Factor recovery by principal axis factoring and maximum likelihood factor analysis as a function of factor pattern and sample size. Journal of applied statistics 2012, 39, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Hattori, M.; Trichtinger, L. Target Rotation With Both Factor Loadings and Factor Correlations. Psychological Methods 2018, 24, 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.G.; Kim, R.S.; Aloe, A.M.; Becker, B.J. Extracting the variance inflation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 2017, 39, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevopoulos, E.; Christakou, A.; Karanasios, S.; Louka, A.P.; Pamboris, G.M.; Papandreou, M. Translation, Adaptation and Validation of the Greek Version of the Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic Shoulder and Elbow Score in Greek Overhead Athletes. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, HF. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika. 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistic | Absolute magnitude of the observed statistic | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.01-0.06 | Non-acceptable internal consistency |

| 0.61-0.70 | Acceptable internal consistency | |

| 0.71-0.80 | Good and acceptable internal consistency | |

| 0.81-0.90 | Good internal consistency | |

| 0.91-1.00 | Excellent internal consistency | |

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient | 0.00-0.49 | Poor test-retest reliability |

| 0.50-0.75 | Moderate test-retest reliability | |

| 0.75-0.90 | Good test-retest reliability | |

| 0.91-1.00 | Excellent test-retest reliability | |

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.00-0.10 | Negligible correlation |

| 0.10-0.39 | Weak correlation | |

| 0.40-0.69 | Moderate correlation | |

| 0.70-0.89 | High correlation | |

| 0.90-1.00 | Excellent correlation |

| Variable (continuous) | Mean value (SD) | Median value (Q1-Q3) | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 38.9 (14.8) | 35.0 (26.0 – 55.0) | 55 |

| Height (centimetres) | 172.5 (10.0) | 171.0 (165.0 -180.0) | 55 |

| Weight (kilograms) | 76.7 (19.9) | 70.0 (63.0 – 86.0) | 55 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 25.6 (5.3) | 24.5 (22.2 – 27.3) | 55 |

| Pain duration (Months) | 7.5 (10.7) | 4.0 (3.0 – 5.0) | 55 |

| Pain intensity (VAS score)1 | 7.0 (0.9) | 7.0 (6.0 – 8.0) | 55 |

| KOOS-PF score2 | 36.3 (16.6) | 30.1 (22.7 – 50.0) | 55 |

| KOS-ADL score3 | 50.6 (18.1) | 47.1 (38.6 – 64.3) | 55 |

| Variable (dichotomous) | Absolute frequency | Relative frequency | 55 |

| Gender assigned at birth | |||

| Female | 31 | 56.4% | |

| Male | 24 | 43.6% |

| Statistic | Point estimate | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.87 | 0.85 to 0.93 | <0.001 |

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient | 0.95 | 0.71 to 0.99 | <0.001 |

| Standard Error of Measurement (SEM) | 3.7 | - | - |

| Smallest Detectable Difference (SDD) | 13.6 | - | - |

| Correlation coefficients | Point estimate | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| KOOS-PF versus KOS-ADL1 | 0.72 | 0.57 to 0.83 | <0.001 |

| KOOS-PF versus VAS2 | - 0.64 | -0.45 to -0.77 | <0.001 |

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | Item 9 | Item 10 | Item 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 1.0000 | ||||||||||

| Item 2 | 0.4308 | 1.0000 | |||||||||

| Item 3 | 0.3345 | 0.5710 | 1.0000 | ||||||||

| Item 4 | 0.4079 | 0.3871 | 0.5240 | 1.0000 | |||||||

| Item 5 | 0.6000 | 0.4642 | 0.5785 | 0.5939 | 1.0000 | ||||||

| Item 6 | 0.5838 | 0.5241 | 0.6206 | 0.6291 | 0.8323 | 1.0000 | |||||

| Item 7 | 0.3400 | 0.2739 | 0.3290 | 0.4740 | 0.4183 | 0.4050 | 1.0000 | ||||

| Item 8 | 0.0529 | 0.1129 | 0.2565 | 0.4381 | 0.3456 | 0.5449 | 0.3122 | 1.0000 | |||

| Item 9 | 0.0739 | 0.1754 | 0.1949 | 0.3380 | 0.4226 | 0.4543 | 0.4342 | 0.6514 | 1.0000 | ||

| Item 10 | 0.4454 | 0.5646 | 0.6306 | 0.5508 | 0.6176 | 0.6774 | 0.4376 | 0.3488 | 0.2928 | 1.0000 | |

| Item 11 | 0.4432 | 0.3205 | 0.5417 | 0.4075 | 0.5627 | 0.6267 | 0.2170 | 0.3997 | 0.2358 | 0.5142 | 1.0000 |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Item1 | 0.8220 | -0.3115 |

| Item2 | 0.6852 | -0.1357 |

| Item3 | 0.8573 | -0.0988 |

| Item4 | 0.5770 | 0.2652 |

| Item5 | 0.7612 | 0.1691 |

| Item6 | 0.7030 | 0.3539 |

| Item7 | 0.3818 | 0.3816 |

| Item8 | -0.0152 | 0.9079 |

| Item9 | -0.0530 | 0.9216 |

| Item10 | 0.7840 | 0.1131 |

| Item11 | 0.7634 | -0.0262 |

| Eigenvalue | 5.1241 | 3.0158 |

| %ofvariance | 46.58 | 27.42 |

| KOOS-PF scale | KOOS-PF value | % scoring | Effect classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Floor effects | 0 (minimum/worst score) |

0 % | negligible |

| Ceiling effects | 100 (maximum/best score) |

0 % | negligible |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).