1. Introduction

The Parvovirus B19 (B19V) is a globally distributed single-stranded DNA virus from the Parvoviridae family. This human pathogen can infect individuals of all ages, though it is primarily associated with mild and self limiting infections in childhood. In children, the disease typically manifests as erythema infectiosum, commonly referred to as the “slapped cheek” rash. In adults and high-risk populations, signs and symptoms may vary and often include arthralgia and anaemia. Notably, up to 25% of infections in both children and adults may be asymptomatic. Additionally, subclinical infections with non-specific, cold-like symptoms can occur, though they are infrequently attributed to B19V[

1,

2,

3].

Certain populations, including individuals with red blood cell deficiencies, immunocompromised patients, and pregnant women are at high-risk for developing specific complications from B19V infection. In individuals with red blood cell deficiencies, hemoglobinopathies, or other haematological disorders, B19V infection can lead to aplastic crises and congestive heart failure, particularly in children. Patients who are immunocompromised, whether due to underlying diseases or immunosuppressive therapies, are at risk of developing chronic B19V infection, which may lead to pure red cell aplasia, often without the presence of rash and arthralgia[

2]. Pregnant women infected with B19V have a 17% to 35% probability of transplacental transmission to the foetus, typically occurring 1 to 3 weeks after maternal infection. Foetal infection can result in severe anaemia, nonimmune hydrops fetalis (NIHF), and intrauterine foetal death (IUFD). Although the risk of complications cannot be excluded at any stage of pregnancy, the risk is minimal if the infection is contracted during the second half of pregnancy, with the highest risk of foetal death observed when maternal infection is acquired between 9 and 16 weeks of gestation[

4].

Additionally, B19V infection has been associated with other conditions, including hepatitis, myocarditis, autoimmune disorders, and a plethora of central and peripheral nervous system manifestations[

2,

3,

5,

6]. Although these and other associations have long been considered rare, recent studies suggest underreporting due to lack of testing and awareness or indicate a stronger-than-expected association[

7,

8]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of predominantly European studies found the prevalence of B19V infection in myocarditis cases to be 23.7% (95% CI: 18.7%-29.5%), suggesting a possible causal relationship. However, the exact role played by B19V in myocarditis remains uncertain, as a similar prevalence of the virus was found in endomyocardial biopsies of healthy subjects and those with myocarditis and dilated cardiomyopathy. It has been suggested that B19V may play a role in conjunction with other viruses, or pathogenesis may depend on viral load or replication activity[

7].

Regardless of clinical manifestations, individuals typically undergo seroconversion and develop immunity following infection, even in asymptomatic cases. Globally, seroconversion rates increase with age, ranging from 2% to 20% in children under 5 years, 15% to 40% in those aged 5 to 18 years, and 40% to 80% in adults, although some geographical regions may exhibit deviations from this trend[

3]. Consistent with these findings, women of reproductive age show a susceptibility to B19V infection ranging from 26% to 44%, commonly cited as 40%. Consequently, the risk of infection in pregnant women is estimated at approximately 1% to 2% during endemic periods, rising to 10% during epidemic outbreaks[

4]. In effect, seroconversion reduces the number of susceptible individuals in a population, which is one of the factors influencing B19V circulation. Another factor influencing viral circulation is the disease's transmission dynamics, with non immunised groups acting as primary drivers of an epidemic. Notably, recent studies reported a near-absence of B19V circulation during the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting a potential decline in population specific immunity and the risk of subsequent rebound outbreaks[

9,

10]. In April 2024, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) reported an increase in B19V infection notifications across several EU/EEA countries towards the end of 2023 and during 2024[

11]. At that time, in Italy, notification of B19V infection was not required by law, meaning that cases were usually not reported to health authorities for surveillance[

12]. As a result, data on the incidence of B19V infections in Italy are currently limited to trends in positive plasma units for fractionation, with no comprehensive epidemiological data on the national historical trend of infections and their prevailing clinical presentation [

13].

The objective of this study is first and foremost to assess the epidemiological situation of B19V infections in the Veneto Region, Italy, to determine whether the recent outbreak has affected this region.

A secondary aim is to collect data on the clinical presentation of B19V infection both in the not-high-risk and the high-risk populations previously described, specifically focusing on hospitalised cases.

Finally, the study seeks to gather additional data on conditions considered rare but associated with B19V infection, such as myocarditis, to contribute to the limited literature on these topics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

In response to the ECDC Report, an observational study was conducted to assess the epidemiology of B19V infection in the Veneto Region, Italy, from January 1, 2024, to August 4, 2024 (weeks 1–31). The study period encompassed both retrospective data collection (January 1 to May 2, 2024) and enhanced surveillance initiated on May 3, 2024, when mandatory disease reporting was established by Regional mandate.

2.2. Case Definition

The cases reported in the study include probable and confirmed cases. Probable cases were defined as those presenting with erythema infectiosum, characterised by the hallmark slapped cheek sign, and/or an epidemiological link to a confirmed case, with the exclusion of other probable causes.

The diagnostic approach for B19V infection included nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) and serological testing. Serological testing was conducted using a chemiluminescent immunoassay (CLIA) to detect IgM and IgG antibodies in serum or plasma samples, while nucleic acid testing involved quantitative real-time PCR performed on whole blood or amniotic fluid samples to detect viral DNA. Diagnostic procedures for pregnant women were conducted in accordance with the national AMCLI (Associazione Microbiologi Clinici Italiani) guidelines, ensuring that testing and interpretation adhered to the latest evidence-based standards[

14]. The selection of tests was individualised by attending physician based on clinical presentation and specific patient populations. Molecular testing (PCR) was performed in hospitalised patients, immunocompromised individuals, pregnant women, or when specifically requested by the prescribing physician. Serological testing was conducted in hospitalised patients (alongside PCR) and in any case where requested by the physician.

2.3. Data Collection

The Veneto Region issued a communication on May 3, 2024 (week 18), addressed to all Local Health Authorities (LHAs), Hospital Organisations, and the Veneto Institute of Oncology. The communication required the following actions:

mandatory reporting of all cases of erythema infectiosum (fifth disease) or B19V infection;

epidemiological investigation of all reported cases to identify contacts with individuals at high-risk;

provision of diagnostic testing free of charge for all high-risk contacts associated with probable or confirmed cases.

Clinicians were also requested to provide retrospective data on confirmed cases diagnosed from January 1, 2024, onwards.

Information regarding the risks associated with B19V infection in pregnant women was disseminated. The directive also recommended collaboration with relevant hospital departments and clinicians, including Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pediatrics, Microbiology, Infectious Diseases, General Practitioners, and Pediatricians, to ensure effective implementation of the outlined measures.

Physicians reported positive cases by submitting documentation to their respective Public Health Office, part of the Local Health Authorities (LHAs). Public Health staff conducted epidemiological investigations and forwarded the information to the regional and national authorities through the Regional Infectious Diseases Notification Platform, SIRMI. SIRMI is integrated with the National Disease Surveillance Platform, PREMAL.

The regional authority, in accordance with the national regulation, accessed data from the infectious disease surveillance platform and conducted an analysis of disease trends for public health purposes.

Data collected included patient demographics, date of symptom onset as reported by the patient, date of notification, clinical presentation, hospitalisation status, and any comorbidities.

2.4. Data Organisation and Analysis

Anonymised data were organised and stored using Google Sheets for preliminary management and presentation. The information was categorised by age groups, symptom onset dates, notification dates, hospitalisation status, and comorbidities.

Data analysis was performed using RStudio (version 2021.09.1 Build 372). Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the distribution of cases and hospitalisation rates across different age groups. Confidence intervals were calculated to estimate the proportion of severe cases requiring hospitalisation.

A chi-square test with Bonferroni correction was employed to assess whether the likelihood of hospitalisation differed across various age groups.

The clinical presentations of hospitalised individuals were analysed both collectively and by comorbidity.

To support the discussion of reported symptoms and comorbidities, the most frequent clinical presentations were categorised as: generic, dermatologic, rheumatologic, cardiac, haematologic, neurologic, obstetric, and other. Detailed categorization is provided in Supplementary 1.

Finally, Granger causality analysis was employed to assess whether the temporal trends of cases in the 1-5 years and 6-11 years age groups, characterised by a lower seroprevalence, influenced trends and informed the prediction of future cases in other age groups, thereby suggesting a potential causal relationship. A 3-day lag was applied in the Granger causality test to account for potential delays in transmission dynamics.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological Trends

Preliminary data on B19V surveillance in Veneto for 2024, as of week 31 (July 29th – August 4th), indicate an increase in cases beginning primarily from epidemiological week 19 (May 6th-12th). This was followed by a peak in week 21 (May 20th-26th), with a subsequent steady decline in the following weeks, reaching the lowest number of cases in week 31. During the surveillance period, 3,156 B19V cases were reported to the Local Health Authorities (LHAs), while laboratories identified 684 NAAT positive cases and detected 3,061 cases positive for both IgM and IgG antibodies, resulting in an almost one-to-one match between case notifications and laboratory confirmations.

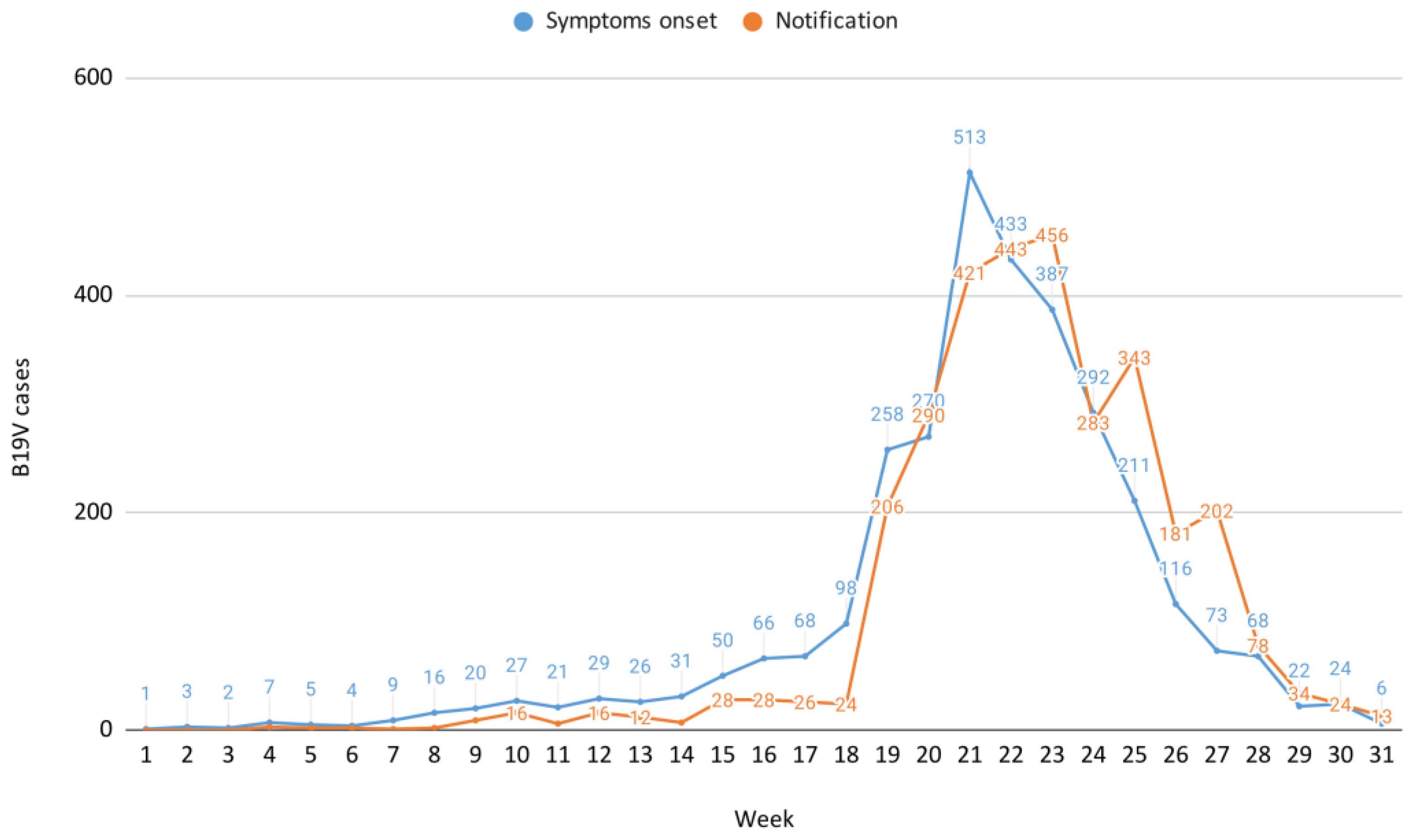

The B19V case distribution by symptom onset and notification, weeks 1-31, 2024 is reported in

Figure 1, which also illustrates a notification delay of approximately one week compared to the onset of symptoms, consistent with reporting at the time of rash appearance.

3.2. Demographic Distribution, Influence on Transmission, and Hospitalisation Rates

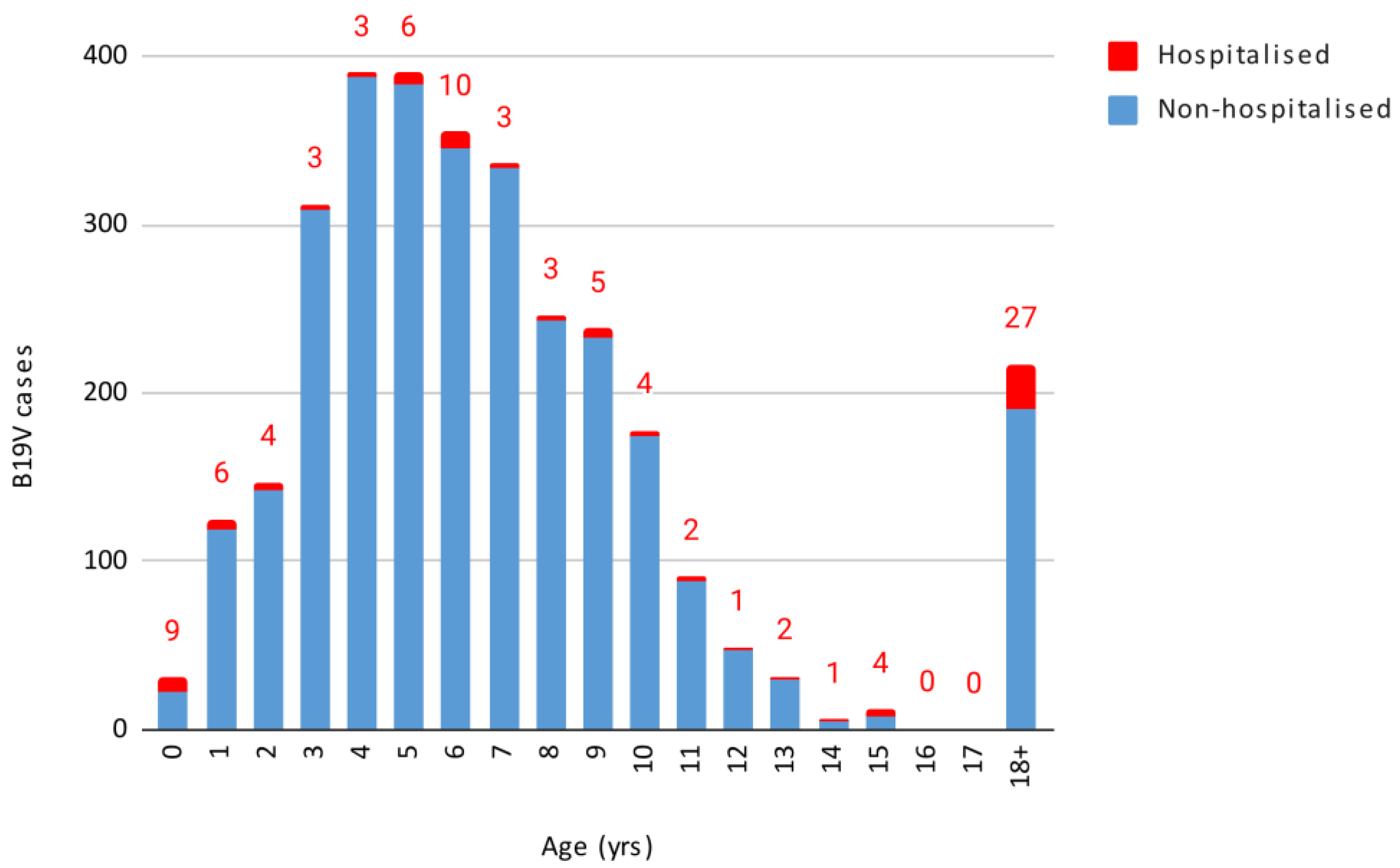

Out of the 3,156 cases, 1,619 were females and 1,537 were males, without a statistically significant difference. The infection predominantly impacted children aged 1-5 and 6-11 years, with both age groups showing a peak in week 21, consistent with the overall data. These age groups overlap with the typical age of nursery and elementary school students.

Figure 2 displays the number of B19V cases and hospitalisations by age.

When performing the Granger causality test to determine whether the age groups with the highest number of cases affected the incidence in the other age groups, with a 3-day lag, the results were as follows. The 1-5 years age group had a significant influence both on the incidence of cases in all other age groups combined (p-value = 0.0086) and individually on the 6-11 years (p-value = 0.000499) and 18-40 years age groups (p-value = 0.0146). Conversely, the 6-11 years age group did not show a statistically significant influence on all other age groups combined or on most other age groups when considered individually, except for a potential effect on those under 1 year of age (p-value = 0.0292).

Out of 3,156 cases, 93 (2.9%, 95% CI 2.4-3.5%) required hospitalisation, with varying rates across different age groups (

Table 1).

The highest hospitalisation rate (29%) was observed in children under 1 year of age, although this includes infants hospitalised for postnatal monitoring. The 18-40 years age group exhibited a hospitalisation rate of 17.5%, the 12-17 years age group of 8% and those over 40 years of 5.5%. The chi-squared test revealed that children under 1 year of age and adults aged 18-40 years had significantly higher hospitalisation rates compared to other age groups (p < 2.2×10−16). After applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, the findings remained significant (adjusted α=0.0033).

3.3. Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation data was available for 50 of the 93 hospitalised individuals. The most common signs and symptoms at admission were fever (18/50 cases, 36.0%), anaemia (11/50 cases, 22.0%), skin rash (7/50 cases, 14.0%), and arthralgia or myalgia (7/50 cases, 14.0%).

Examining the severity of clinical presentations, two women were admitted for miscarriage during the second trimester of pregnancy. Two cases developed myocarditis, while another case presented with pericarditis. Additionally, two more cases were admitted for suspected myocarditis. One particularly severe case involved a patient admitted with cardiorespiratory arrest, acute renal failure, and anoxic-ischemic brain injury with cerebral oedema, who ultimately died. Another case developed Henoch -Schönlein purpura with cutaneous, articular, and gastrointestinal involvement. Neurological presentations included one case of febrile seizures, one case of acute-onset ataxia, and one case of severe headache with speech impairment, which was diagnosed as possible encephalitis. Haematological presentations included one case of hemolytic crisis, one case of vaso-occlusive crisis, one case of cytopenia, one case of medullary aplasia, one case of leukopenia, and two cases of leuko-thrombocytopenia, along with one case of an unspecified alteration of the hemogram. Other nonspecific presentations included asthenia (2 cases), reduced appetite (1 case), and low-grade fever below 38°C (1 case). Additional dermatological presentations included urticaria (2 cases).

3.4. Comorbidities and Pregnancy in Hospitalised Cases

Comorbidities were present in 20 out of 93 (21.5%) hospitalised cases. Haematological diseases were the most common comorbidity, accounting for 60% (12/20) of cases. These included spherocytosis (4 cases), beta thalassemia minor (2 cases), sickle cell disease (2 cases), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, leukaemia, heterozygous HbS/HbC, and an unspecified hemoglobinopathy. Infectious diseases were the next most common comorbidity, representing 25% (5/20) of cases, including Epstein-Barr virus (n=2), tuberculosis (n=1), enterovirus detected in cerebrospinal fluid (n=1), and an unspecified bacterial infection. Other comorbidities included an unspecified malignancy, multiple sclerosis, and an eating disorder.

Clinical presentation was available for 13 out of the 20 hospitalised patients with comorbidities. The distribution of symptoms among hospitalised individuals varied depending on comorbidity status. In patients without comorbidities, generic symptoms were the most prevalent (48.6%, 18/37 cases), followed by hematologic (32.4%, 12/37 cases), dermatologic (24.3%, 9/37 cases), rheumatologic (16.2%, 6/37 cases), and neurologic (13.5%, 5/37 cases) symptoms. Additionally, 5.4% (2/37 cases) reported miscarriage and 35.1% (13/37 cases) experienced "other" symptoms. Haematological disorders were most frequently associated with haematologic symptoms (77.8%, 7/9 cases) and less commonly with generic (11.1%, 1/9 cases) and cardiac (11.1%, 1/9 cases) symptoms. Infectious comorbidities were primarily linked to generic symptoms (50%, 1/2 cases) and "other" symptoms (50%, 1/2 cases). Other comorbidities were associated with generic symptoms (50%, 1/2 cases) and cardiac and "other" symptoms (50%, 1/2 cases each).

It should be highlighted that all cases of miscarriage (n=2), myocarditis (n=2), suspected myocarditis (n=2), Henoch-Schönlein purpura (n=1), febrile seizures (n=1), ataxia (n=1), and possible encephalitis (n=1) occurred in individuals with no reported comorbidities. The case presenting with pericarditis occurred in a patient with a documented eating disorder. The unique case presenting with cardiorespiratory arrest, acute renal failure, and anoxic-ischemic brain injury accompanied by cerebral oedema, was also in a patient with no reported comorbidities. Anaemia was observed in both patients with haematological disorders (5 out of 12 cases with reported clinical presentation) and those without comorbidities (6 out of 50 cases with reported clinical presentation). Cases of hemolytic crisis (n=1) and vaso-occlusive crisis (n=1) were reported exclusively in individuals with haematologic comorbidities, whereas other haematologic presentations, such as cytopenia (n=1), medullary aplasia (n=1), leukopenia (n=1), and leuko-thrombocytopenia (n=2) occurred in individuals with no reported comorbidities. No comorbidities were reported in individuals presenting with a skin rash.

Pregnancy was reported in 4.3% (4/93) of hospitalised cases. Three of these women had no concomitant diseases or symptoms. One woman, who had beta thalassemia minor, required blood transfusions due to anaemia.

4. Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the epidemiological patterns, clinical characteristics, and impact of comorbidities in the 2024 parvovirus B19 outbreak in the Veneto Region. The implications of these findings are discussed in the context of existing literature, considering the potential role of comorbidities and co-infections in disease severity, as well as outlining limitations and future directions for B19V surveillance and research.

The implementation of mandatory reporting for B19V significantly enhanced the collection of prospective data, enabling a comprehensive analysis of its epidemiological trajectory and insights into unusual severe manifestations of the disease. Continued surveillance in this setting could facilitate rapid detection and response to future outbreaks while contributing valuable data to the national and international public health framework. Consequently, the Veneto Region will maintain ongoing monitoring. Additionally, implementing genotypic surveillance could enable the detection of specific B19V genotypes during outbreaks.

This study suggests a possible B19V circulation during late winter and spring, followed by a decline in cases as summer approaches, likely reflecting the expected seasonality of this virus[

2,

3,

10,

15]. Additionally, the study captures the decline phase of the B19V epidemiological curve, providing precise epidemiological insights into the local progression of the outbreak. Notably, surveillance data showed that cases continued to occur until June-July, which suggests prolonged onward transmission. The reporting system operated with a one-week delay relative to the onset of symptoms, which aligns with a typically delayed healthcare-seeking behaviour, whereby patients do not immediately consult general practitioners or specialists for testing and probably wait until the development of a cutaneous rash.

The analysis of age-related transmission patterns indicates that younger children, particularly those aged 1-5 years, played a significant role in the spread of the virus, possibly triggering the circulation and amplification of transmission in other age-groups. This is consistent with prior research, which identifies young children as being the most susceptible to and infected with B19V[

3]. However, to our knowledge this study is the first to demonstrate a direct impact of infections in the 1-5 year age group on other age groups. Settings where these children congregate, such as daycare centres and preschools, are likely critical points of transmission. These findings suggest that public health interventions targeting the 1-5 years age group could significantly impact outbreak control, both in the 1-5 years and in the remaining age groups. Such interventions may include enhanced infection control measures in early childhood education environments and targeted public health messaging for parents [

16]. Additionally, targeted monitoring of cases in the 1-5 years age group could serve as an early warning for local healthcare authorities, facilitating improved preparedness and response to the spread of infection to other age cohorts in subsequent weeks.

Although severe and life-threatening disease as a consequence of infection was relatively rare overall, hospitalisation rates were notably high in certain age groups, including the <1 year cohort, which had a hospitalisation rate of 29%, and the 18-40 years cohort, with a rate of 17.5%. These rates are considerably higher than the overall 2.9% hospitalisation rate and also exceed those reported in a recent study, which reported a 1.8% hospitalisation rate among children under 15 years attending the emergency department[

17]. Among hospitalised cases, the clinical presentation varied, with fever, anaemia, skin rash, and arthralgia or myalgia being the most prevalent symptoms. Notably, some cases exhibited severe complications including myocarditis, pericarditis, and severe neurological conditions such as possible encephalitis, which have been increasingly linked to B19V[

7,

18,

19,

20]. The occurrence of two miscarriages underscores the well-documented risks of B19V in pregnancy[

21,

22]. This aligns with recent findings by Russcher et al., who reported adverse outcomes, including perinatal death, termination of pregnancy, persistent hydrops, or severe cerebral anomalies, in 36% of foetuses who required intrauterine transfusions during the 2023-2024 parvovirus B19 epidemic in Northwestern Europe[

23]. Some authors have even suggested evaluating the introduction of universal serological testing for B19V in pregnant women during epidemic periods, to enable early infection management and potentially reduce adverse foetal outcomes[

24]. These findings highlight the need to raise awareness among clinicians about the potential for severe complications in a disease typically considered to be mild. Prompt recognition is critical for appropriate follow-up and treatment strategies, especially in pregnant women, individuals with cardiac complications, and those with anaemia [

25,

26].

Ultimately, the presence of concurrent pathologies in a significant proportion of hospitalised cases (22%) suggests that these comorbidities may exacerbate the severity of the disease, and vice versa. The high prevalence of concurrent haematological disorders in hospitalised cases, including spherocytosis and beta-thalassemia minor, highlights the interaction between B19V and underlying conditions. This is consistent with findings from other outbreaks, where individuals with haematological disorders were disproportionately affected by severe B19V complications[

3,

17]. Additionally, co-infections with pathogens such as Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, and tuberculosis were present in 25% (5/20) of cases. Literature also suggests that B19V co-infections with other viruses, such as influenza or Epstein-Barr virus, may exacerbate disease severity and further complicate clinical outcomes[

27,

28,

29].

In conclusion, our findings underscore the importance of targeted public health interventions, particularly among high-risk groups, and highlight areas where enhanced surveillance could strengthen outbreak detection and management, aligning with recent recommendations from the Italian Ministry of Health. Specifically, the Ministry has recommended that all Regions and Autonomous Provinces increase physician awareness of B19V, communicate risks to vulnerable groups (such as pregnant women, immunocompromised individuals, and patients with chronic blood disorders), and conduct multidisciplinary analyses of historical data to track transmission trends and patterns[

30,

31]. Future research should focus on understanding B19V’s interactions with co-infections and assessing the benefits of a national surveillance framework. Integrating these findings will help refine public health responses and improve clinical outcomes in subsequent outbreaks.

This study has some limitations. Most of the reported cases lacked microbiological data, as national reporting of B19V is not mandatory and there is no structured data collection form in place. Additionally, it was not possible to cross-reference patient laboratory data with notification records due to regulations governing the processing of personal data. Furthermore, the request for retrospective data has not led to the collection of substantial numbers of cases before the request for mandatory notification. This may be attributed to a lower epidemiological presence of B19V in the region, as well as potential underdiagnosis due to low awareness and insufficient testing, alongside underreporting of historical cases. This inference is supported by the limited but existent national data on B19V-positive plasma units intended for fractionation.

Another key limitation is the uncertainty regarding the nature of the reported comorbidities. It is unclear whether these comorbidities represent longstanding conditions, as the term suggests, or newly diagnosed concurrent diseases, such as infectious conditions like Epstein-Barr virus, enterovirus, or tuberculosis, identified at the time of hospitalisation.

Finally, clinical presentation data were not available for 43 out of the 93 hospitalised cases, which weakens the robustness of the findings regarding hospitalisation rates, as some patients, such as newborns and pregnant women, may have been hospitalised for testing or reasons unrelated to the infection.

5. Conclusions

This study contributes to the broader understanding of the disease's transmission dynamics, clinical manifestations, and the impact of comorbidities. The findings provide valuable insights for public health authorities and clinicians, offering a basis for improved prevention and treatment strategies in future outbreaks. The feasibility of implementing a mandatory systematic and potentially EU-wide surveillance system for B19V, with active international communication and collaboration, should be explored. Additionally, integrating B19V genomic surveillance could provide additional valuable insights on viral diversity and pathogenicity, further guiding targeted public health interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T and D.G; methodology, M.T, D.G, V.B, S-A.P; software, D.G and F.D.R.; validation, FL.R, A.T.P, R.C and FR. R; formal analysis, M.T and D.G.; investigation, A.F, N.C,D.B, F.Z, M.T.P, M.P, S.M, M.M, M.N, G.P, M.S.V.; resources, R.C, M.S.V, M.P., A.F; data curation, D.G, S.A.P, F.D.R, G.P and MT; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.P, D.G, M.T, FL. R,N.C, A.F; writing—review and editing, S.A.P, D.G, M.T, FL. R, M.N, M.M, G.P, FR. R, A.T.P, V.B, F.D.R, M.S.V; visualization, D.G, M.T and S.A.P.; supervision, V.B, FR. R and R.C; project administration, M.T, F.R and V.B.; funding acquisition, V.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by EU funding within the NextGenerationEU-MUR PNRR Estended Partnership initiative on Emerging Infectious Disease (Project no. PE00000007, INF-ACT)

Institutional Review Board Statement

This is an observational study. No ethical approval is required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Leung, A.K.C.; Lam, J.M.; Barankin, B.; Leong, K.F.; Hon, K.L. Erythema Infectiosum: A Narrative Review. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2024, 20, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reno, M.L.; Cox, C.R.; Powell, E.A. Parvovirus B19: a Clinical and Diagnostic Review. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 2022, 44, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Soderlund-Venermo, M.; Young, N.S. Human Parvoviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 43–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attwood, L.O.; Holmes, N.E.; Hui, L. Identification and management of congenital parvovirus B19 infection. Prenat. Diagn. 2020, 40, 1722–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardi, C.; Tinazzi, E.; Bason, C.; Dolcino, M.; Corrocher, R.; Puccetti, A. Human parvovirus B19 infection and autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2008, 8, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewska, K.; Arvia, R.; Bua, G.; Margheri, F.; Gallinella, G. Parvovirus B19: Insights and implication for pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Asp. Mol. Med. 2023, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, A.; Razizadeh, M.H.; Ghadirali, M.; Yazdani, S.; Bahadory, S.; Soleimani, A. Association of parvovirus B19 and myocarditis/dilated cardiomyopathy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 162, 105207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bihari, C.; Rastogi, A.; Saxena, P.; Rangegowda, D.; Chowdhury, A.; Gupta, N.; Sarin, S.K. Parvovirus B19 Associated Hepatitis. Hepat. Res. Treat. 2013, 2013, 472027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russcher, A.; van Boven, M.; Benincà, E.; Verweij, E.J.T. (.; Backer, M.W.A.M.-D.; Zaaijer, H.L.; Vossen, A.C.T.M.; Kroes, A.C.M. Changing epidemiology of parvovirus B19 in the Netherlands since 1990, including its re-emergence after the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mor, O.; Wax, M.; Arami, S.-S.; Yitzhaki, M.; Kriger, O.; Erster, O.; Zuckerman, N.S. Parvovirus B19 Outbreak in Israel: Retrospective Molecular Analysis from 2010 to 2023. Viruses 2024, 16, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Communicable disease threats report, week 16, 2024. Final report. Accessed August 12, 2024. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/communicable-disease-threats-report-week-16-2024_final.pdf.

- Italian Ministry of Health. Decree of 7 March 2022 - Revision of the infectious disease reporting system (PREMAL). (22A02179) Official Gazette of the Italian Republic - General Series. 7 April 2022; No. 82. Accessed August 13, 2024. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/04/07/22A02179/sg.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Risks posed by reported increased circulation of human parvovirus B19. Final report. Accessed August 13, 2024. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Risks%20posed%20by%20reported%20increased%20circulation%20of%20human%20parvovirus%20B19%20FINAL.pdf.

- AMCLI ETS. Percorso Diagnostico "Infezioni a Trasmissione Verticale da Parvovirus B19" - Rif. 2023-10, rev. 2023", Available online: https://www.amcli.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/10_PD_B19_def25mag2023.pdf, accessed on 06.11.2024.

- Nicolay, N.; Cotter, S. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of parvovirus B19 infections in Ireland, January 1996-June 2008. Eurosurveillance 2009, 14, 19249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC, Emergency Preparedness and Response, Increase in Human Parvovirus B19 Activity in the United States,, Distributed via the CDC Health Alert Network, August 13, 2024, 2:30 PM ET, Available online: https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2024/han00514.asp. (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- D’humières, C.; Fouillet, A.; Verdurme, L.; Lakoussan, S.-B.; Gallien, Y.; Coignard, C.; Hervo, M.; Ebel, A.; Soares, A.; Visseaux, B.; et al. An unusual outbreak of parvovirus B19 infections, France, 2023 to 2024. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2400339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ivanova, S.K.; Angelova, S.G.; Stoyanova, A.P.; Georgieva, I.L.; Nikolaeva-Glomb, L.K.; Mihneva, Z.G.; Korsun, N.S. Serological and Molecular Biological Studies of Parvovirus B19, Coxsackie B Viruses, and Adenoviruses as Potential Cardiotropic Viruses in Bulgaria. Folia Medica 2016, 58, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douvoyiannis, M.; Litman, N.; Goldman, D.L. Neurologic Manifestations Associated with Parvovirus B19 Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1713–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poeta, M.; Moracas, C.; Carducci, F.I.C.; Cafagno, C.; Buonsenso, D.; Maglione, M.; Sgubbi, S.; Liberati, C.; Venturini, E.; Limongelli, G.; et al. Outbreak of paediatric myocarditis associated with parvovirus B19 infection in Italy, January to October 2024. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Jong, E.P.; Walther, F.J.; Kroes, A.C.M.; Oepkes, D. Parvovirus B19 infection in pregnancy: new insights and management. Prenat. Diagn. 2011, 31, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigi, C.E.; Anumba, D.O. Parvovirus b19 infection in pregnancy – A review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 264, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russcher, A.; Verweij, E. (.; Maurice, P.; Jouannic, J.-M.; Benachi, A.; Vivanti, A.J.; Devlieger, R. Extreme upsurge of parvovirus B19 resulting in severe fetal morbidity and mortality. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e475–e476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetin, I.; Tassis, B.; Parisi, F.; Parodi, V.; Romagnoli, V.; Giacomel, G. Universal serological screening for Parvovirus B19 in pregnancy during European epidemic. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 300, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordholm, A.C.; Møller, F.T.; Ravn, S.F.; Sørensen, L.F.; Moltke-Prehn, A.; Mollerup, J.E.; Funk, T.; Sperling, L.; Jeyaratnam, U.; Franck, K.T.; et al. Epidemic of parvovirus B19 and disease severity in pregnant people, Denmark, January to March 2024. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2400299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, M.E.S.; Hassan, S.A.; Seleim, T.; Lateef, R.A. Parvovirus B19 infection in children with a variety of hematological disorders. Hematology 2006, 11, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callon, D.; Berri, F.; Lebreil, A.-L.; Fornès, P.; Andreoletti, L. Coinfection of Parvovirus B19 with Influenza A/H1N1 Causes Fulminant Myocarditis and Pneumonia. An Autopsy Case Report. Pathogens 2021, 10, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stojkovic-Filipovic, J.; Skiljevic, D.; Brasanac, D.; Medenica, L. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome associated with Ebstein-Barr virus and Parvovirus B-19 coinfection in a male adult: case report and review of the literature. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014; 151, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karrasch, M.; Felber, J.; Keller, P.M.; Kletta, C.; Egerer, R.; Bohnert, J.; Hermann, B.; Pfister, W.; Theis, B.; Petersen, I.; et al. Primary Epstein–Barr virus infection and probable parvovirus B19 reactivation resulting in fulminant hepatitis and fulfilling five of eight criteria for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 28, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Circular of the Italian Ministry of Health. (2024, November 6). Oggetto: Aumento dei rilevamenti di infezione da Parvovirus B19 – Raccomandazioni (No. 0033146-06/11/2024-DGPRE-DGPRE-P).

- Yee, M.E.; Kalmus, G.G.; Patel, A.P.; Payne, J.N.; Tang, A.; Gee, B.E. Notes from the Field: Increase in Diagnoses of Human Parvovirus B19–Associated Aplastic Crises in Children and Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease — Atlanta, Georgia, December 14, 2023–September 30, 2024. Mmwr-Morbidity Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 1090–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).