Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Background

2.1. What Is M-AR and Why?

2.2. M-AR as a Participatory Tool

2.3. Placemaking and AR

2.3.1. Sociability and M-AR

2.3.2. Physical Setting and M-AR

2.3.3. Image and M-AR

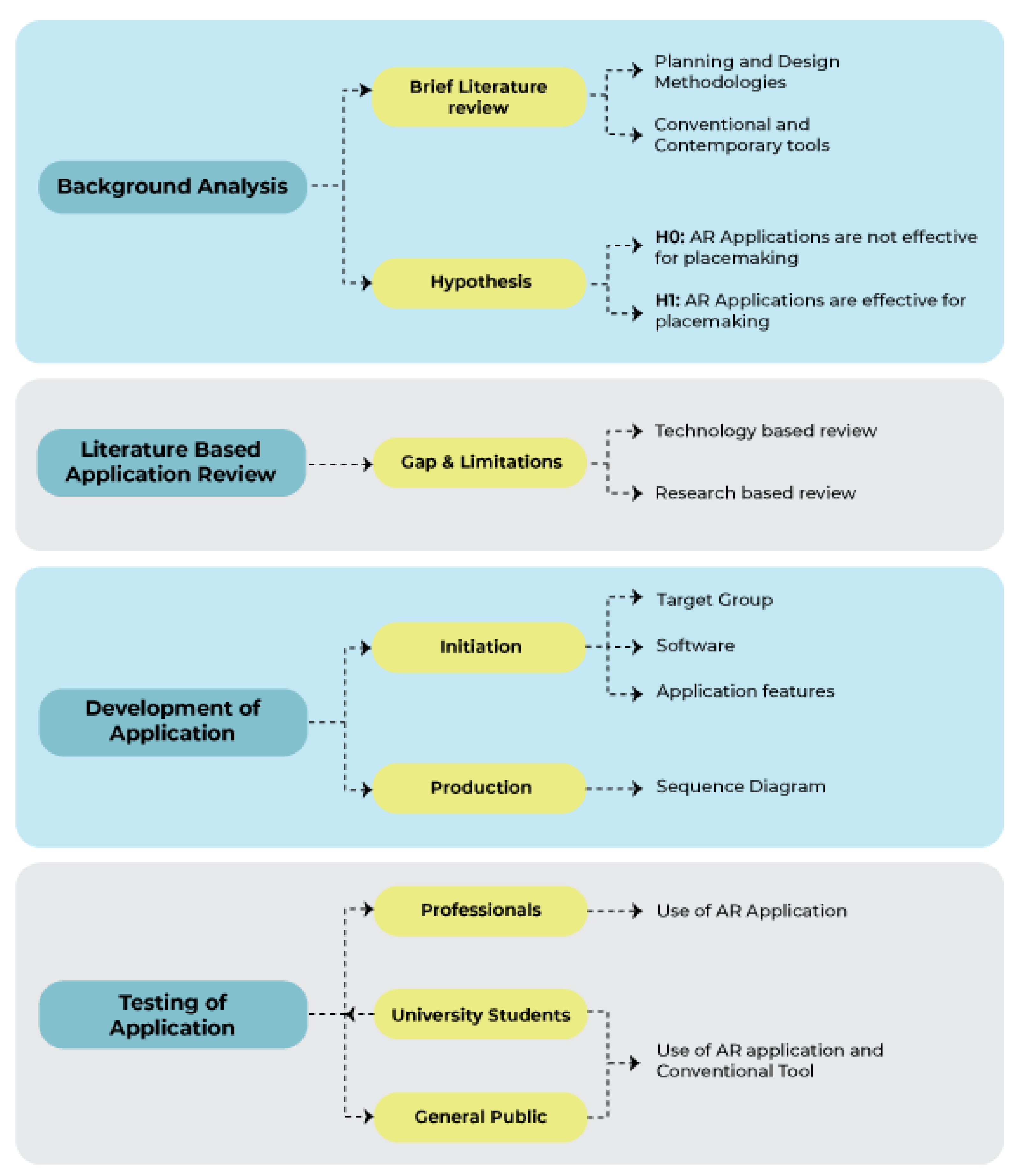

3. Research Design

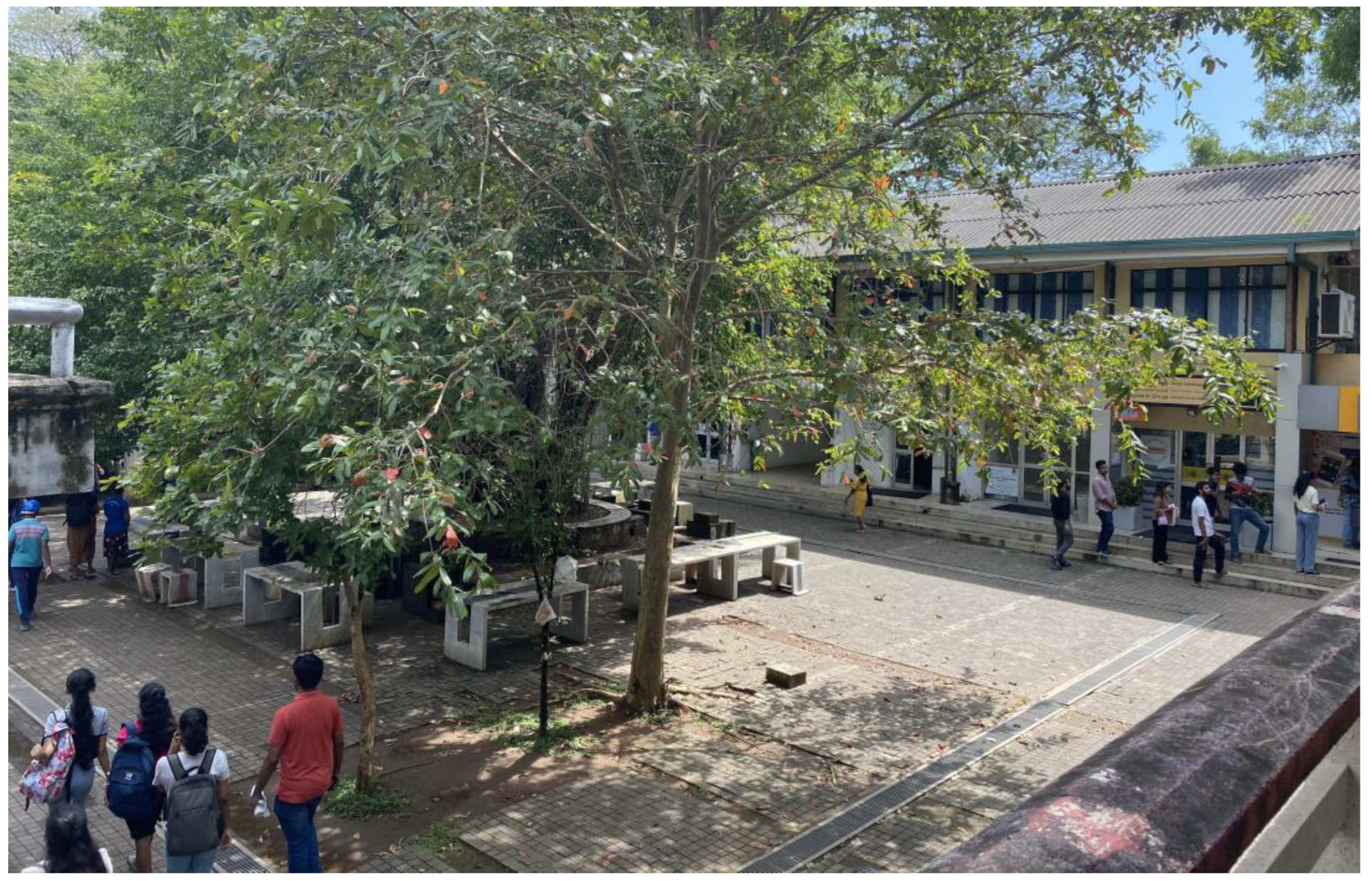

3.1. Background Analysis

3.2. Literature-Based Application Review

| No | AR Application | Type | Focus | Developer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ways2gether | Mobile | Traffic Planning | Jauschneg & Stoik | http://www.junaio.com |

| 2 | Augmented Reality UJI (ARUJI) | Mobile | AR guiding app for the students and visitors around the University of Jaume I and available for Android devices as an unsigned application | Francisco Ramos, Sergio Trilles, Joaquín Torres-Sospedra and Francisco J. Perales |

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ijgi/special_issues/safety_security |

| 3 | Green Living Augmented + virtual ReAlity (GLARA) | Mobile | Microclimatic effects | Fluxguide | https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.Fluxguide.GLARA&pcampaignid=web_share |

| 4 | Smart [AR] Mini-Application | Mobile | Digital placemaking app | Samaneh Sanaeipoor; Khashayar Hojjati Emami | https://doi.org/10.1109/SCIOT50840.2020.9250208 |

| 5 | City 3D-AR | Web / Mobile |

Provide 3D object placement in real space for enhanced visualization |

Arnis Cirulisa, Kristaps Brigis Brigmanisb |

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2013.11.009 |

| 6 | Junaio | Mobile | Create, explore and share information in a completely new way using augmented reality |

Metaio | http://www.junaio.com/ |

| 7 | Change Explorer | Watch / mobile / web | A smartphone app that notifies the public when they are close to an area that has plans for redevelopment. |

Alexander Wilson | https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808317712515 |

| 8 | In-Citu AR | Mobile | City Governments. Make urban development accessible and visible using AR, city-wide | Dana Chermesh-Reshef | https://www.incitu.us/ |

| 9 | CitySense App | Mobile | Co-creation of buildings, spaces | H2020 European Projects | https://re.public.polimi.it/handle/11311/1175121 |

| 10 | Augmented Reality Participatory Platform (ARPP) | Mobile | Platform uses mobile augmented reality (M- AR) to engage residents, particularly in under-resourced communities, in identifying the design improvements necessary to enhance neighborhood walkability | Saeed Ahmadi Oloonabadi, Perver Baran | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104441 |

| 11 | Tinmith-Metro | Mobile | Visualisation of designed buildings |

Thomas, Piekarski, and Gunther, 1999 | http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2071536.2071538 |

| 12 | StudierStubeES software(StbES) |

Mobile | Tracking and visualisation framework | Schmalstieg and Wagner, 2007 | http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2071536.2071538 |

| 13 | City View AR | Mobile | Disaster Visualization – Earthquake | Mark Billinghurst, Gun Lee, Jason Mill, Rob Lindeman, Adrian Clark, Thammathip Piumsomboon, Rory Clifford, Shunsuke Fukuden | https://www.hitlabnz.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/cityviewar_qrcode.png |

| 14 | Architeque – 3D & AR | Mobile | Platform for Product Presentations in 3D & Augmented Reality |

Architeque LLC | http://www.ar-chiteque.com/ |

| 15 | Vidente | Mobile | Demonstrating underground infrastructure virtualization in the field. |

Schall, Mendez et al. (2009) | http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2071536.2071538 |

| 16 | Urban Sketcher | Computer Based | Users can directly alter the real scene by sketching 2D images which are then applied to the 3D surfaces of the augmented scene | Sareika and Schmalstieg (2007) | http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2071536.2071538 |

| 17 | Wikitude | Mobile | M-AR application which captures images from the surrounding environment (e.g. sights, restaurants, streets, and shops) and displays relevant information, on the screen of the mobile device. |

Wikitude GmbH | http://wikitude.com/ |

| 18 | Nokia city lens | Mobile | Uses your device’s camera to display nearby restaurants, stores, and other notable locations in augmented reality style | Andrew Webster | http://www.windowsphone.com/s?appId=93301a45-5849-4aad-a68e-c7c95df83ca1 |

| 19 | ARQuake game | Computer Based | ARQuake is an Augmented Reality (AR)version of the popular Quake game. Augmented Reality is the overlaying of computer-generated information onto the real world | Thomas et al(2000) | http://www.tinmith.net |

| 20 | Archeoguide | Mobile | Augmented Reality based Cultural Heritage On-site GUIDE | Vlahakis V., et al. 2002 | http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/584993.585015 |

| 21 | Mentira | Mobile | Example of location-based M-AR for Albuquerque city. The purpose of the game is learning Spanish as a foreign language and addresses visitors among others | Prof. Chris Holden, Prof. Julie Sykes | http://www.mentira.org/ |

| 22 | GUIDE & Augmenting the Visitor Experience | Mobile | Location based M-AR applications for the residents and the tourists, developed for the area of Keswick of Lake District, Cumbria, UK | University of Nottingham, University College London and Leicester University constitute | |

| 23 | Frequency 1550 | Mobile | City mobile game enabling students to learn about the history of Amsterdam. | Montessori Scholengemeenschap Amsterdam, IVLOS, Uva -ILO, OSB Open Schoolgemeenschap, Bijlmer | https://waag.org/en/project/frequency-1550 |

| 24 | Dow Day | Mobile | Uses a journalistic narration genre and player takes the role of a news reporter and investigate the different perceptions of virtual characters who participated in protests against Dow Chemical Corporation for making napalm for the war in 1967. | Aris Games | http://arisgames.org/featured/dow-day/ |

| 25 | Road of Rhodes game | A game application which introduces the user in the cultural history of the island, and it was created using the ARIS authoring tool |

Aris Games | ISBN 978-960-99791-2-2 | |

| 26 | CityScope | Mobile | Community engagement platform | MIT Media Lab’s Changing Places Group (CPG) | 10.1016/j.procs.2017.08.180 |

| 27 | Urban CoBuilder | Mobile | Outdoor urban simulation tool based on AR. | Hyekyung Imottesjo, Jaan-Henrik Kai | https://imottesjo.se/Urban-CoBuilder |

| 28 | EduPARK | Mobile | Use image-based AR, with marker-based tracking, to display mainly botanical content. | Lúcia Pombo, Margarida Morais Marques | http://edupark.web.ua.pt/mobile_app?lang=en |

| 29 | ARGarden | Mobile | Enabling AR handheld device with multi-user interaction to create 3D outdoor designs. | F E Fadzli, M A Mohd Yusof, A W Ismail, M S Hj Salam and N Aismail | http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/979/1/012001 |

| 30 | Vítica | Mobile | Reactivation of Cisneros Market Square’s cultural heritage and its surroundings using GPS and augmented reality. | Mauricio Hincapi, Christian Díaz, Maria-Isabel Zapata-Cardenas, Henry de Jesus Toro Rios, Dalia Valencia, David Güemes-Castorena | http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2827856 |

| 31 | Magical Park | Mobile | Encourages children to explore the park and run around, by engaging them in games played inside a blended virtual environment | GEO AR Games | https://www.geoar.com/magical-park |

| 32 | Minecraft Earth | Mobile | This game brings the blocky construction set into the physical world. Minecraft Earth users do not pursue any specific goal; they can merely create, build, and explore in freedom while playing alone or cooperatively in a real territory or in an environment created by the players | Mojang Studios in 2009 | https://www.minecraft.net/en-us/article/new-game--minecraft-earth |

| 33 | Geocaching | Web Based/ | This high-tech treasure hunting game, users hide a cache (typically a small waterproof container) in some location and post its coordinates along with some clues on the Internet. | Stuart Aldrich, Erika Zhou, Thomas M., Thomas Manoka, Ruhais Li | https://www.geocaching.com/plan/lists/BM58MPC |

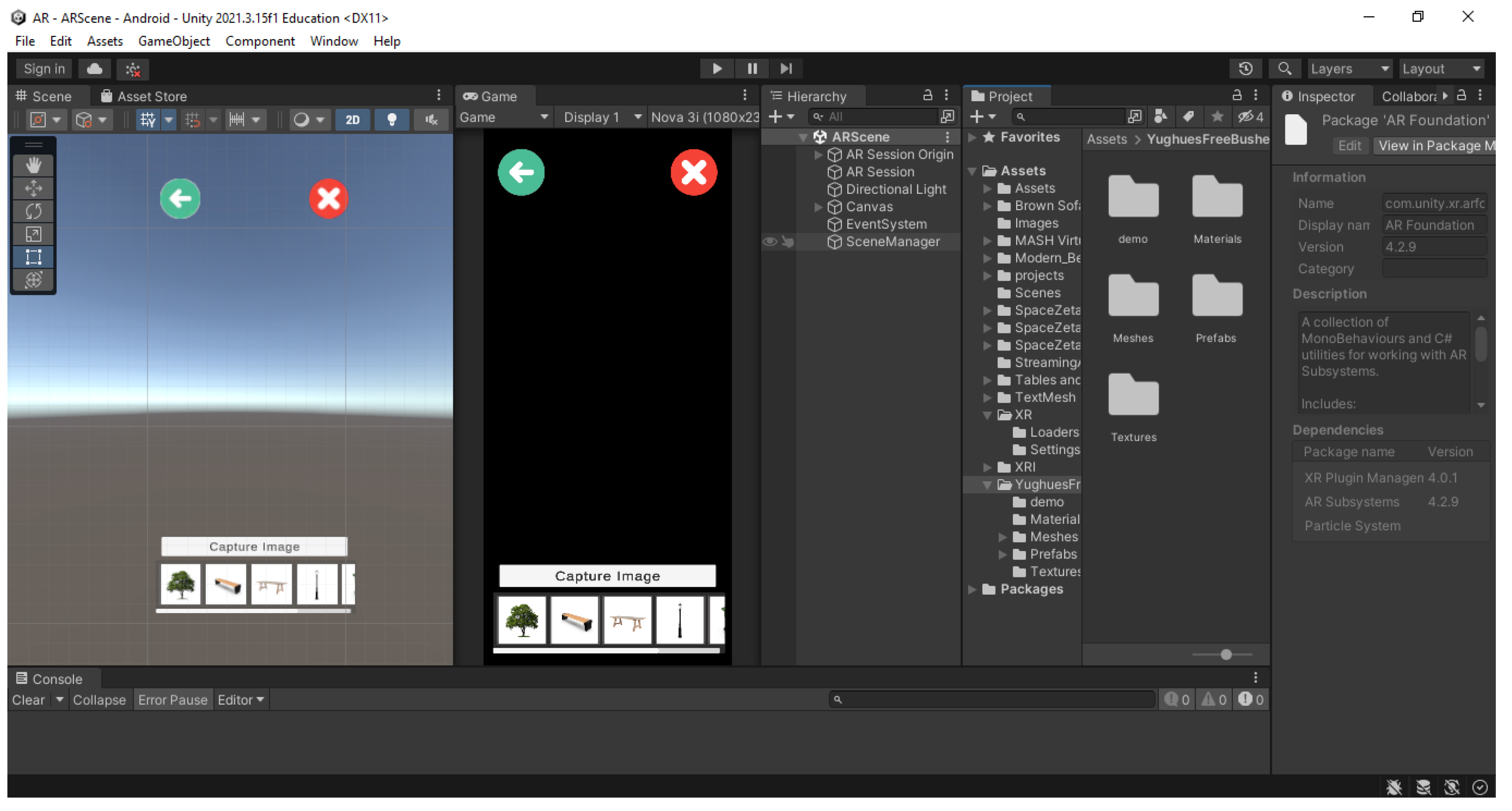

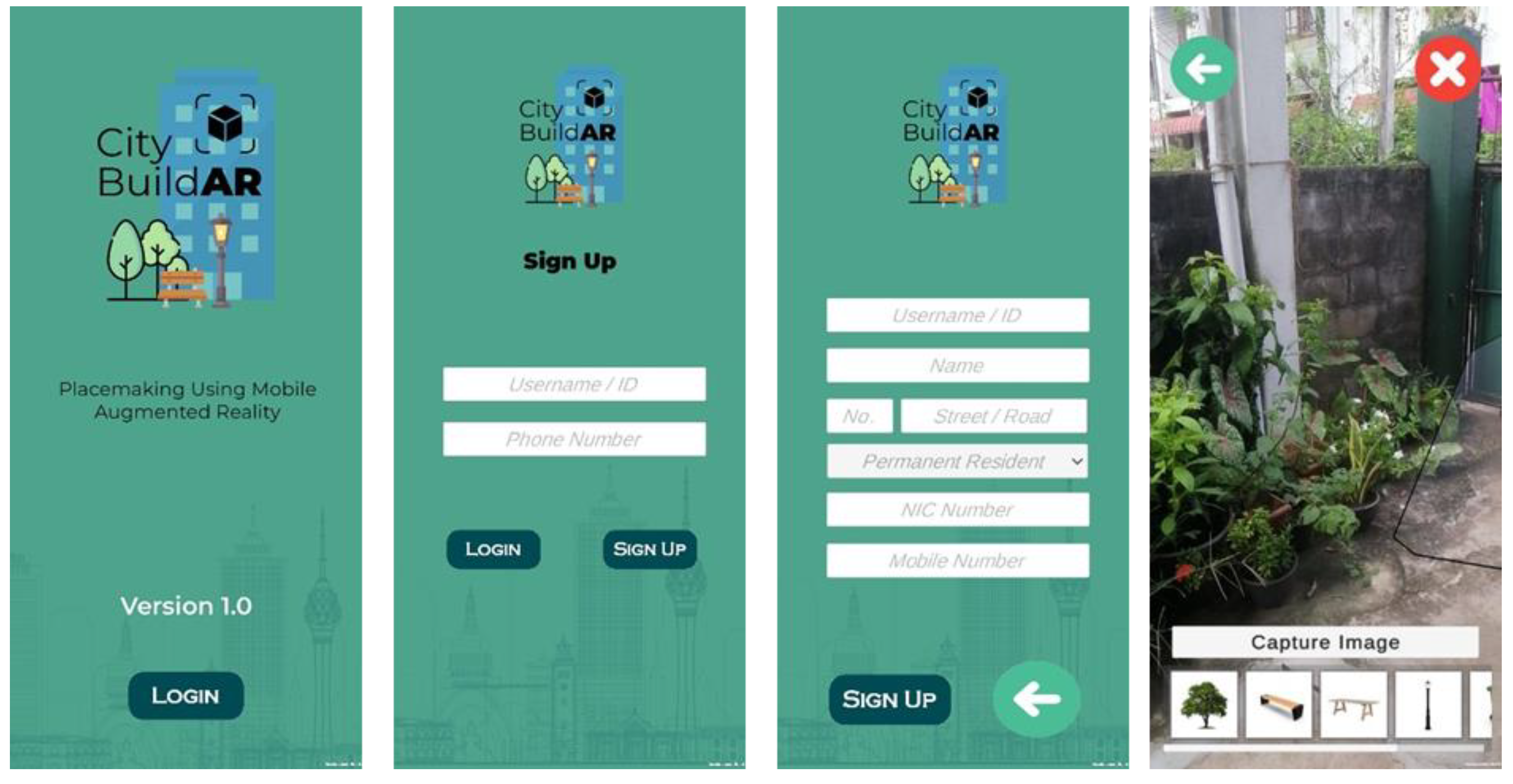

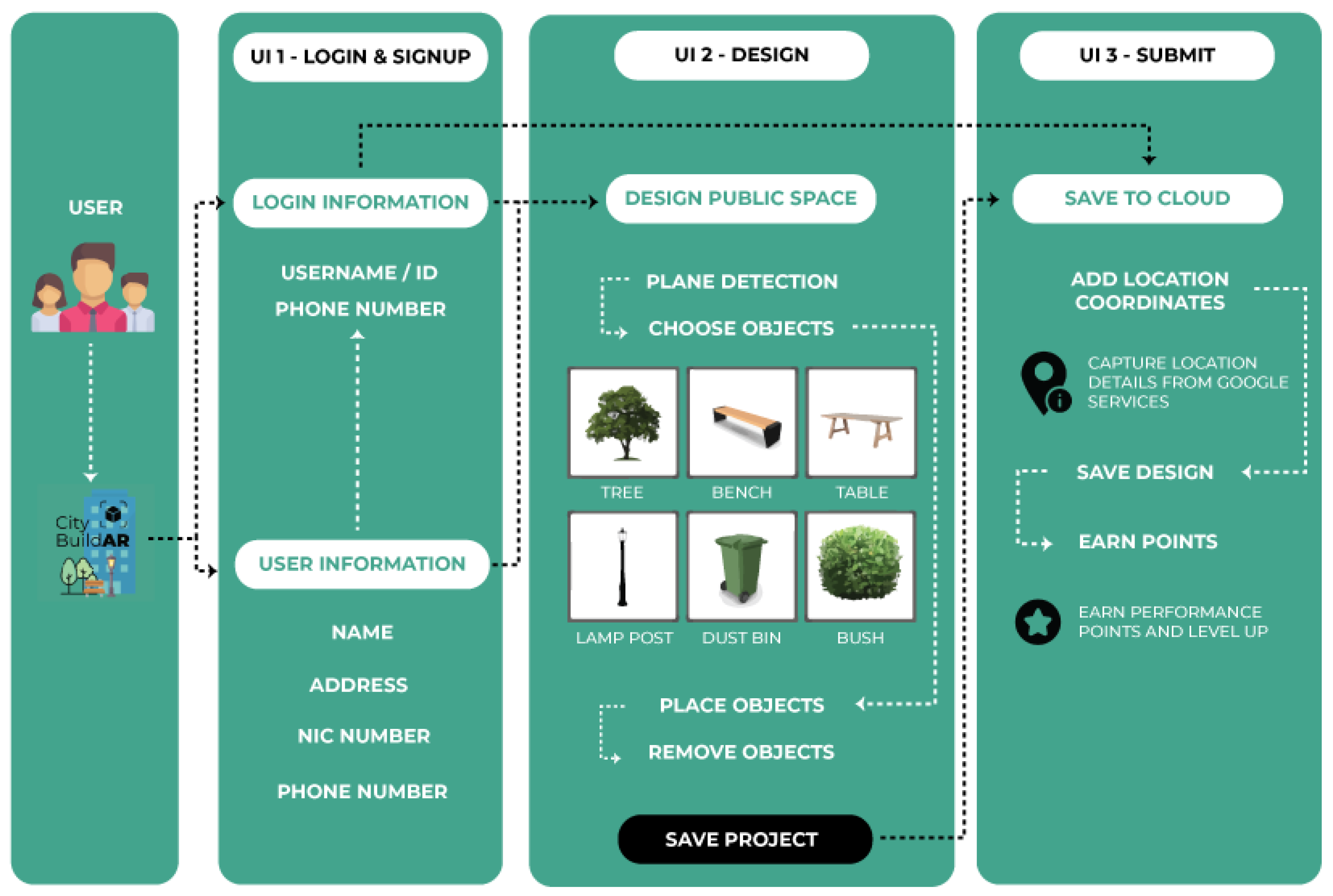

3.3. Development of Application

3.3.1. Initiation

3.3.2. Target Group

3.3.3. Software

3.3.4. Application Features

3.3.5. Production

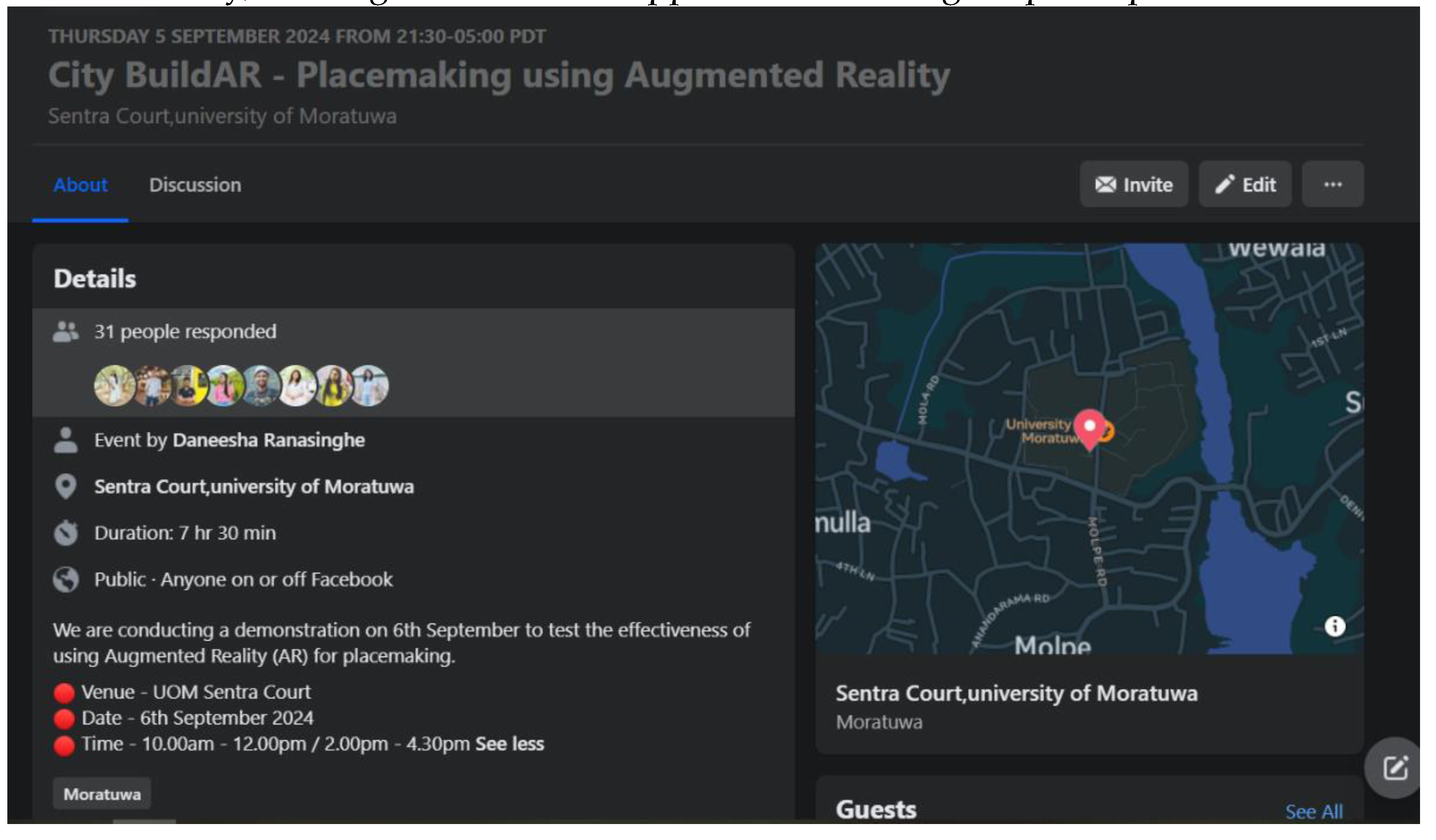

3.3.6. Testing the Application

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Overview

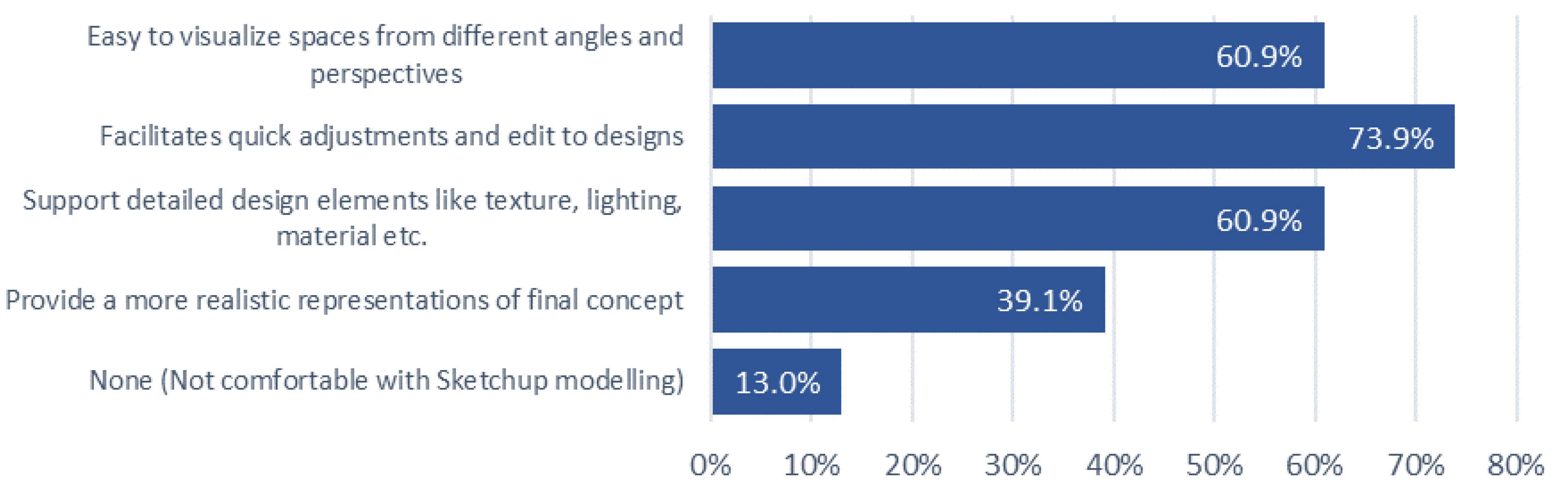

4.2. Comparing Hand Sketching, Software with CityBuildAR

4.3. Place-Making with CityBuildAR

4.4. Image Analysis

4.5. Opinion Analysis

4.5.1. Ability to Visualize and Design with Limited Skills

- Participant 1 - “I have limited drawing skills, so I usually engaged in collaborating with ideas as a group member while another member will visualize. But using this AR app I can do my own design by myself. But the list of elements and features should expand to make a unique design.”

- Participant 2 - “I really liked the interface and elements of the app. It creates a nice design of myself with limited skills. Wish I had more time to get familiar with this app.”

- Participant 3 - “Simple and effective for non-designers.”

4.5.2. Impact on Creativity of Users

- Participant 1 - “Great concept for enhancing placemaking through real-time visualization. However, the limited design options and occasional bugs limit its potential in professional landscape projects. Expanding its feature set would make it more versatile.”

- Participant 2 - “App doesn’t allow to create & visualize unique designs. It generalizes the designs and with the given elements, it’s limited to create my own design. Realtime visualization is interesting somehow.”

- Participant 3 - “Expanding the range of features and addressing performance concerns would make it a highly effective tool for professional urban planning and participatory processes.”

4.5.3. Technical Constraints

- Participant 1 - “App elements are difficult to understand in the beginning, needed assistance to understand. I had the ability to do a design for cafeteria using this app, which I wouldn't be able to do with sketching or other software.”

- Participant 2 - “Expanding the range of features and addressing performance concerns would make it a highly effective tool for professional urban planning and participatory processes.”

- Participant 3 - “Using app for designing is good for me because I have poor drawing skills. However, it is difficult to understand and design within this limited time given.”

5. Findings and Conclusions

5.1. To What Extent Does the CityBuildAR App Bridge the Gap Between Professionals and the General Public in Placemaking?

5.2. Can Mobile-AR Tools Like CityBuildAR Replace Traditional Participatory Planning Methods?

5.3. Conclusion

5.4. Limitations

- Plane detection problems: The program necessitates the completion of plane detection before object placement, as it is incapable of identifying additional planes after objects have been positioned.

- Restricted design elements: Participants were given a limited array of items for space design, perhaps hindering their creativity and design alternatives

- Scaling limitations: Users cannot resize items, constraining design flexibility.

- Deletion errors: Specific elements experience faults during deletion, resulting in difficulties in altering the design.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akbar, P.N.G. Placemaking. In Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing; Edward Elgar Publishing: 2022; pp. 515–517. [CrossRef]

- Amirzadeh, M.; Sharifi, A. The evolutionary path of place making: From late twentieth century to post-pandemic cities. Land Use Policy 2024, 141, 107124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, L. New inroads on community-centric placemaking. Nature Cities 2024, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichowsky, A.; Gaul-Stout, J.; McNew-Birren, J. Creative Placemaking and Empowered Participatory Governance. Urban Affairs Review 2023, 59, 1747–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanidou, A.; Vlachokyriakos, V. Participatory, location-based systems in community place-making. In Proceedings of the 7th South-East Europe Design Automation, Computer Engineering, Computer Networks and Social Media Conference (SEEDA-CECNSM), Ioannina, Greece, 23–25 September 2022; IEEE: 2022; pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Naef, P. Touring the ‘comuna’: Memory and transformation in Medellin, Colombia. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 2018, 16, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestes, O.M.; Ultramari, C.; Caetano, F.D. Public transport innovation and transfer of BRT ideas: Curitiba, Brazil as a reference model. Case Studies on Transport Policy 2022, 10, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, N. The Placemaker’s Guide to Building Community; Routledge: 2010. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, R.; Lu, H.; Fernandez, J.; Wang, T. Why do we love the high line? A case study of understanding long-term user experiences of urban greenways. Computational Urban Science 2023, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, K. Imbricated Spaces: The High Line, Urban Parks, and the Cultural Meaning of City and Nature. Sociological Theory 2016, 34, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellery, P.J.; Ellery, J. Strengthening Community Sense of Place through Placemaking. Urban Planning 2019, 4, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, V. Good Places Through Community-Led Design. In Sustainable Development and Planning IX; WIT Press: 2018; pp. 155–164. [CrossRef]

- Fingerhut, Z.; Alfasi, N. Operationalizing Community Placemaking: A Critical Relationship-Based Typology. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abesinghe, S.; Kankanamge, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Pancholi, S. Image of a City through Big Data Analytics: Colombo from the Lens of Geo-Coded Social Media Data. Future Internet, 2023, 15(1), 32. [CrossRef]

- Kangana, N.; Kankanamge, N.; De Silva, C.; Goonetilleke, A.; Mahamood, R.; Ranasinghe, D. Bridging Community Engagement and Technological Innovation for Creating Smart and Resilient Cities: A Systematic Literature Review. Smart Cities, 2024, 7(6), 3823-3852. [CrossRef]

- Pesce, M.F.; Bove, L.; Punzo, S.; Romano, M. Participatory Place-based Storytelling: A Tool to Beat Stereotypes and Unlock the Power of Communities. Procedia CIRP 2024, 12, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolaj, U. Understanding Inclusive Placemaking Processes through the Case of Klostergata56 in Norway. The Journal of Public Space 2022, 7, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GĄSOWSKA-KRAMARZ, A. PRUITT IGOE VS CITY OF THE FUTURE. Architecture, Civil Engineering, Environment 2020, 12, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pınar, E. Entangled histories of Architecture and Dispossession in The Pruitt-Igoe Myth (2011). GRID - Architecture Planning and Design Journal 2024. [CrossRef]

- Beckus, A.; Atia, G.K. Sketch-based community detection in evolving networks. Physical Review E 2022, 106, 044306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeynayake, T.; Meetiyagoda, L.; Kankanamge, N.; Mahanama, P. K. S. Imageability and legibility: cognitive analysis and visibility assessment in Galle heritage city. Journal of Architecture and Urbanism, 2022. 46(2), 126-136. [CrossRef]

- Assumma, V.; Ventura, C. Role of Cultural Mapping within Local Development Processes: A Tool for the Integrated Enhancement of Rural Heritage. Advanced Engineering Forum 2014, 11, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Esparza, J.A.; Nikšić, M. Revealing the Community’s Interpretation of Place: Integrated Digital Support to Embed Photovoice into Placemaking Processes. Urban Planning 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Kankanamge, N. Urban Analytics with Social Media Data: Foundations, Applications and Platforms. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2022,.

- Carmigniani, J.; Furht, B. Augmented Reality: An Overview. In Handbook of Augmented Reality; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 3–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, R.T. A Survey of Augmented Reality. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 1997, 6, 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesim, M.; Ozarslan, Y. Augmented Reality in Education: Current Technologies and the Potential for Education. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 2012, 47, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalender, K.; Singla, B. Augmenting Reality (AR) and Its Use Cases. In Proceedings of the Augmented Reality Applications Conference; 2024; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Designing AR Interfaces for Enhanced User Experience. Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education 2024, 21, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirulis, A.; Brigmanis, K.B. 3D Outdoor Augmented Reality for Architecture and Urban Planning. Procedia Computer Science 2013, 25, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shree, N.; Selvarani, G. Mobile Marker-Based AR Children App for Learning Map. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Circuit Power and Computing Technologies (ICCPCT), IEEE: 2024; pp. 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Blazhko, O.; Shtefan, N. Development of Marker-Based Web Augmented Reality Educational Board Games for Learning Process Support in Computer Science. In Proceedings of the 6th Experiment@ International Conference (exp.at’23), IEEE: 2023; pp. 146–151. [CrossRef]

- Dhar, P.; Rocks, T.; Samarasinghe, R.M.; Stephenson, G.; Smith, C. Augmented reality in medical education: Students’ experiences and learning outcomes. Medical Education Online 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisno, B.; Wibawa, K.; Khaerudin. Digital Storytelling for Early Childhood Creativity: Diffusion of Innovation ‘3-D Coloring Quiver Application Based on Augmented Reality Technology’ in Children’s Creativity Development. International Journal of Online and Biomedical Engineering (iJOE) 2022, 18, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoro, M.F.A.P.; Anistyasari, Y. Implementasi Markerless Location-Based Dalam Aplikasi Peta Augmented Reality Fakultas Teknik Unesa Berbasis Android. Journal of Informatics and Computer Science (JINACS) 2022, 4, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messi, L.; Spegni, F.; Vaccarini, M.; Corneli, A.; Binni, L. Infrastructure-Free Localization System for Augmented Reality Registration in Indoor Environments: A First Accuracy Assessment. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Living Environment (MetroLivEnv), 2024; pp. 110–115. [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.; Sethi, D.; Loh, C.Y.; Lateef, F. Going forward with Pokemon Go. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock 2018, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prananta, A.W.; Biroli, A.; Afifudin, M. Augmented Reality for Science Learning in the 21st Century: Systematic Literature Review. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA 2024, 10, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhrík, M.; Kupko, A.; Krpalová, M.; Hajtmanek, R. Augmented reality and tangible user interfaces as an extension of computational design tools. Architecture Papers of the Faculty of Architecture and Design STU 2022, 27, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Singhal, A. Augmented Reality and its effect on our life. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing, IEEE: 2019, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence); pp. 510–515. [CrossRef]

- Jindal, A. Augmented Reality Applications in Mechanical System Design and Prototyping. Darpan International Research Analysis 2024, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinwald, F.; Berger, M.; Stoik, C.; Platzer, M.; Damyanovic, D. Augmented Reality at the Service of Participatory Urban Planning and Community Informatics—A Case Study from Vienna. The Journal of Community Informatics 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braud, T.; Bijarbooneh, F.H.; Chatzopoulos, D.; Hui, P. Future Networking Challenges: The Case of Mobile Augmented Reality. In Proceedings of the 37th IEEE International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Atlanta, GA, USA, 5–8 June 2017; IEEE, 2017; pp. 1796–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyanovsky, B.B.; Belghasem, M.; White, B.A.; Kadavakollu, S. Incorporating Augmented Reality Into Anatomy Education in a Contemporary Medical School Curriculum. Cureus 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardullo, V.; Wang, C. Pre-service Teachers Perspectives of Google Expedition. Early Childhood Education Journal 2022, 50, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturkcan, S. Service Innovation: Using Augmented Reality in the IKEA Place App. Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases 2021, 11, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounavis, C.D.; Kasimati, A.E.; Zamani, E.D. Enhancing the Tourism Experience through Mobile Augmented Reality: Challenges and Prospects. International Journal of Engineering Business Management 2012, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, V.; Anand, V.; Aggarwal, P.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, G.R. Revolutionizing Military Training: A Comprehensive Review of Tactical and Technical Training through Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Haptics. In Proceedings of the 9th IEEE International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), Pune, India, 7–9 April 2024; IEEE, 2024; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y. Attractiveness of Game Elements, Presence, and Enjoyment of Mobile Augmented Reality Games: The Case of Pokémon Go. Telematics and Informatics 2021, 62, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boboc, R.G.; Gîrbacia, F.; Butilă, E.V. The Application of Augmented Reality in the Automotive Industry: A Systematic Literature Review. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R.S. Immersive Learning Experiences: Technology-Enhanced Instruction, Adaptive Learning, Augmented Reality, and M-Learning in Informal Learning Environments. i-Manager’s Journal of Educational Technology 2019, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza, J.L.; Stephenson, G.; Samarasinghe, R.M.; Rocks, T.; Smith, C. CityScope Platform for Real-Time Analysis and Decision-Support in Urban Design Competitions. International Journal of E-Planning Research 2021, 10, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederer, S.; Priester, R. Smart Citizens: Exploring the Tools of the Urban Bottom-Up Movement. Computer Supported Cooperative Work 2016, 25, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaver, K. Augmented Reality as a Participation Tool for Youth in Urban Planning Processes: Case Study in Oslo, Norway. Frontiers in Virtual Reality 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argo, T.A.; Prabonno, S.; Singgi, P. Youth Participation in Urban Environmental Planning through Augmented Reality Learning: The Case of Bandung City, Indonesia. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 2016, 227, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y. CitySense. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems, Shenzhen, China, 4–7 November 2018; ACM, 2018; pp. 379–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Oloonabadi, S.; Baran, P. Augmented Reality Participatory Platform: A Novel Digital Participatory Planning Tool to Engage Under-Resourced Communities in Improving Neighborhood Walkability. Cities 2023, 141, 104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Regenbrecht, H.; Abbott, M. Smart-Phone Augmented Reality for Public Participation in Urban Planning. In Proceedings of the 23rd Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference, Canberra, Australia, 28 November–2 December 2011; ACM, 2011; p. 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, D.; Govilkar, S. Comparative Study of Augmented Reality SDKs. International Journal on Computational Science & Applications 2015, 5, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Zagalo, N.; Vairinhos, M. Towards Participatory Activities with Augmented Reality for Cultural Heritage: A Literature Review. Computers & Education: X Reality 2023, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, L.; Marques, M.M. Marker-Based Augmented Reality Application for Mobile Learning in an Urban Park: Steps to Make It Real Under the EduPARK Project. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Symposium on Computers in Education (SIIE), Lisbon, Portugal, 6–8 November 2017; IEEE, 2017; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarznia, T.; Pietsch, M.; Krug, R. Testing the Effectiveness of Augmented Reality in the Public Participation Process: A Case Study in the City of Bernburg. Journal of Digital Landscape Architecture 2017, 2, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imottesjo, H.; Kain, J.-H. The Urban CoBuilder—A Mobile Augmented Reality Tool for Crowd-Sourced Simulation of Emergent Urban Development Patterns: Requirements, Prototyping and Assessment. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2018, 71, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Baper, S.Y. Assessment of Livability in Commercial Streets via Placemaking. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchia, L.; Spegni, F.; Vaccarini, M.; Corneli, A.; Binni, L. The Impact of Social Environment and Interaction Focus on User Experience and Social Acceptability of an Augmented Reality Game. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Quality of Multimedia Experience (QoMEX), Ghent, Belgium, 18–20 June 2024; IEEE, 2024; pp. 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammack, P.L. Narrative and the Cultural Psychology of Identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2008, 12, 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Research on the Application of AR Technology in Reconstructing the Digital Presentation of Urban Identity. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Digital Image Processing, Beijing, China, 6–8 May 2023; ACM: 2023; pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Khor, C.Y.; Mubin, S.A. AR Mobile Application for Enhancing National Museum Heritage Visualization. International Journal of Software Engineering and Computer Systems 2024, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, T.; Holston, J. Participatory urban planning in Brazil. Urban Studies, (2015). 52(11), 2001–2017. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kodmany, K. Visualization Tools and Methods for Participatory Planning and Design. Journal of Urban Technology, 2001. 8(2), 1–37. [CrossRef]

- Othengrafen, F.; Sievers, L.; Reinecke, E. Using augmented reality in urban planning processes: Sustainable urban transitions through innovative participation. GAIA - Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society,. (2023). 32(1), 54–63. [CrossRef]

- Sabah, S., Hossain, I., Weiss, D., & Tillmann, A. Towards Increasing Active Citizen Involvement in Urban Planning through Mixed Reality Technologies. (2023).

- Santana, J. M. , Wendel, J., Trujillo, A., Suárez, J. P., Simons, A., & Koch, A. (2017). Multimodal location based services—semantic 3D city data as virtual and augmented reality. Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography, 329–353. [CrossRef]

- Sanaeipoor, S.; Emami, K. H. Smart [AR] Mini-Application: Engaging Citizens in Digital Placemaking Approach. Proceeding of 4th International Conference on Smart Cities, Internet of Things and Applications, SCIoT 2020, 84–90. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Tewdwr-Jones, M.; Comber, R. Urban planning, public participation and digital technology: App development as a method of generating citizen involvement in local planning processes. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City (2019). Science, 46(2), 286–302. [CrossRef]

- Innes. J; Booher D..; Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy. [CrossRef]

- Pissourios, I.; Top-Down and Bottom-Up Urban and Regional Planning: Towards a Framework for The Use of Planning Standards. European Spatial Research and Policy. (2014) 21. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, E. , Baldwin-Philippi, J. and Balestra, M.; 'Why We Engage: How Theories of Human Behavior Contribute to Our Understanding of Civic Engagement in a Digital Era,(2013)'SSRN Electronic Journal [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T. Australian local governments' practice and prospects with online planning. URISA Journal 2006, 18, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, M.; Soro, A.; Brown, R.; Harman, J.; Yigitcanlar, T. Augmenting community engagement in city 4.0: Considerations for digital agency in urban public space. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Degirmenci, K.; Butler, L.; Desouza, K. What are the key factors affecting smart city transformation readiness? Evidence from Australian cities. Cities 2022, 120, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Question Type | Question | Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Closed-ended | How comfortable were you using hand sketching (2D drawing) techniques for placemaking? | 5-Point Likert Scale |

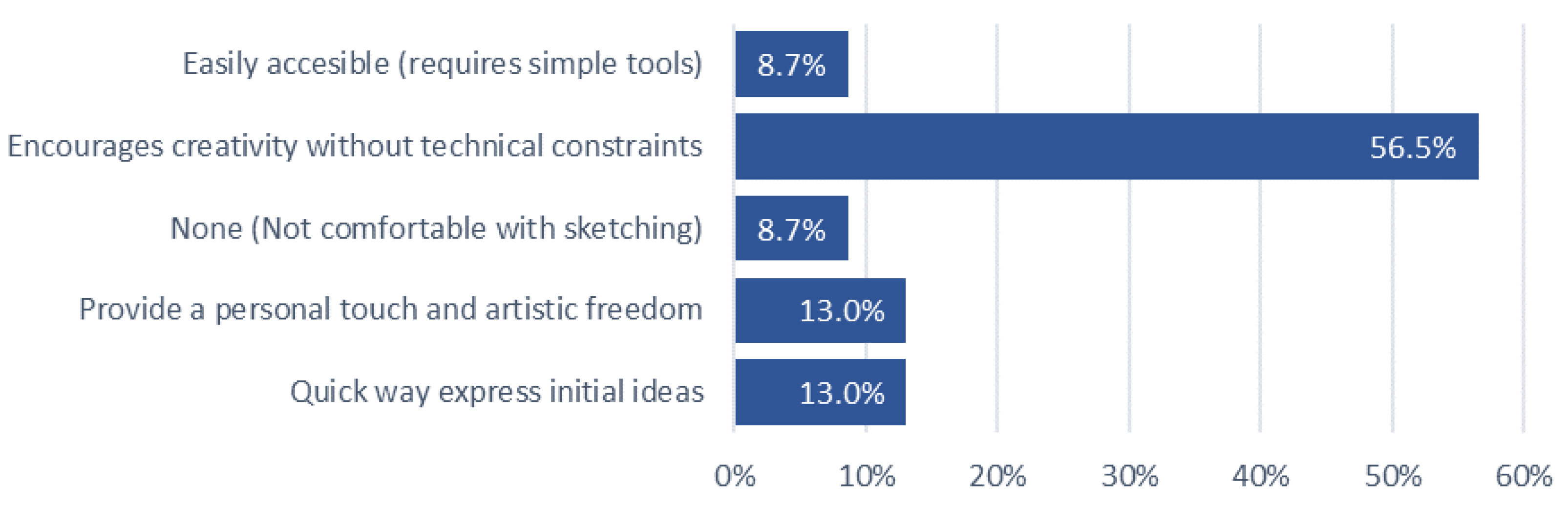

| Q2 | Mixed | What are the positives you experienced while using hand sketching (2D drawing) for placemaking? | Multiple checkboxes and text |

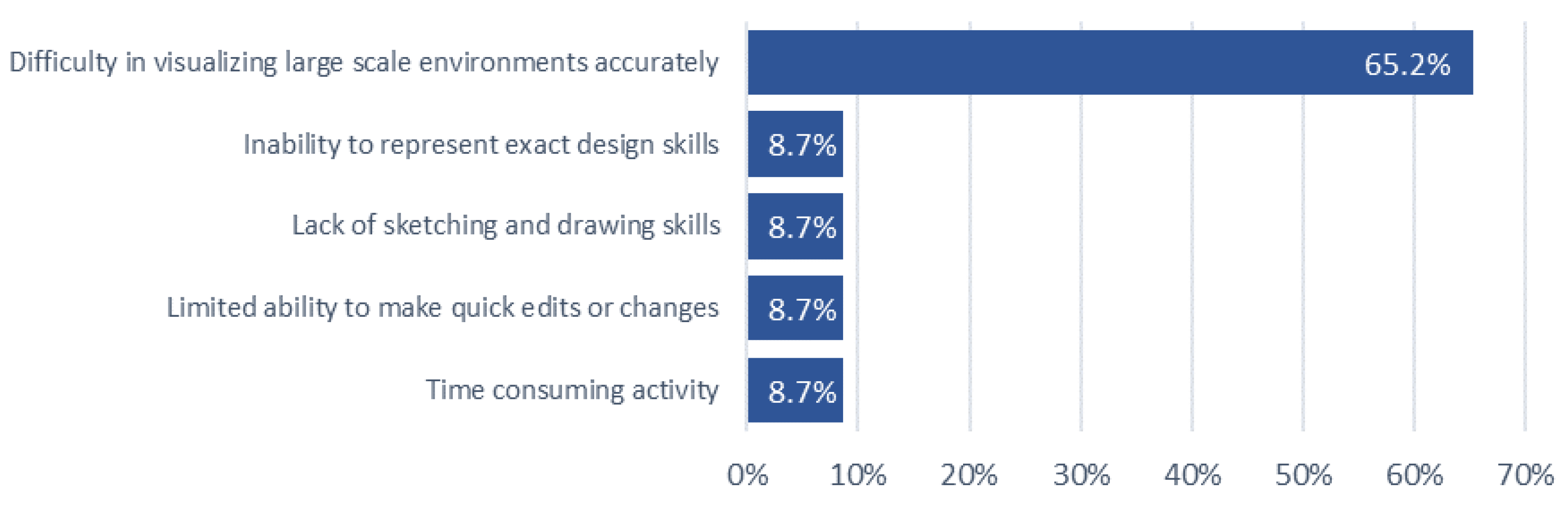

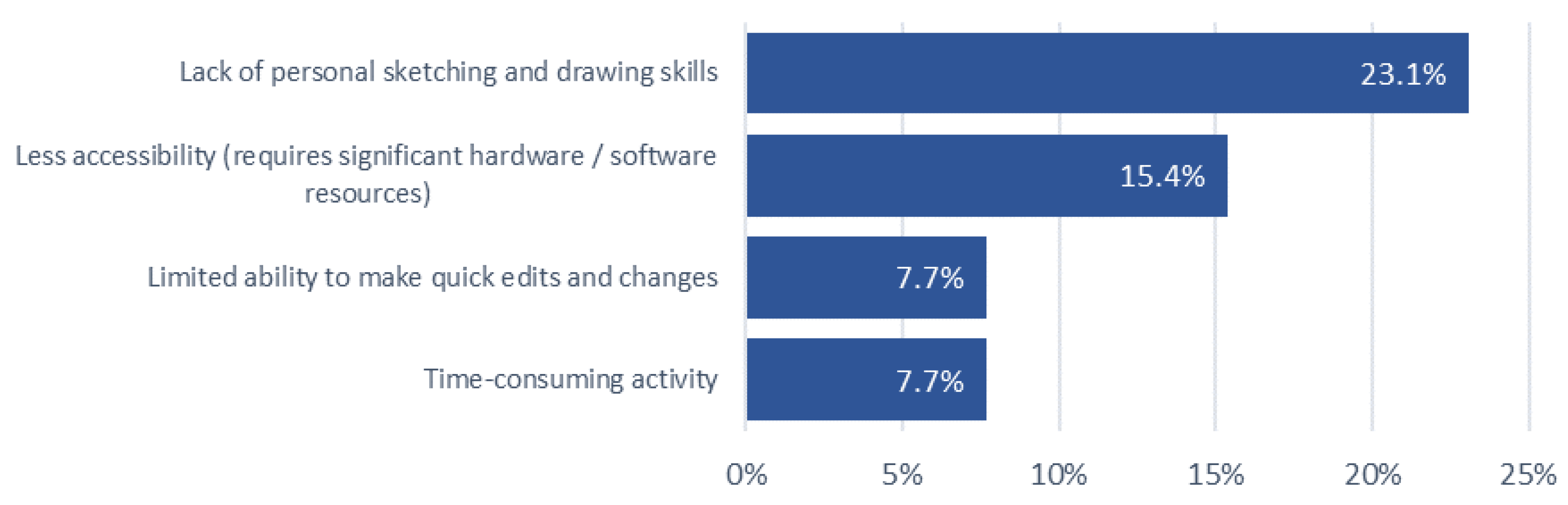

| Q3 | Mixed | What challenges did you face while using hand sketching (2D drawing) for placemaking? | Multiple checkboxes and text |

| Q4 | Closed-ended | How comfortable were you using SketchUp software (3D modelling) techniques for placemaking? | 5-Point Likert Scale |

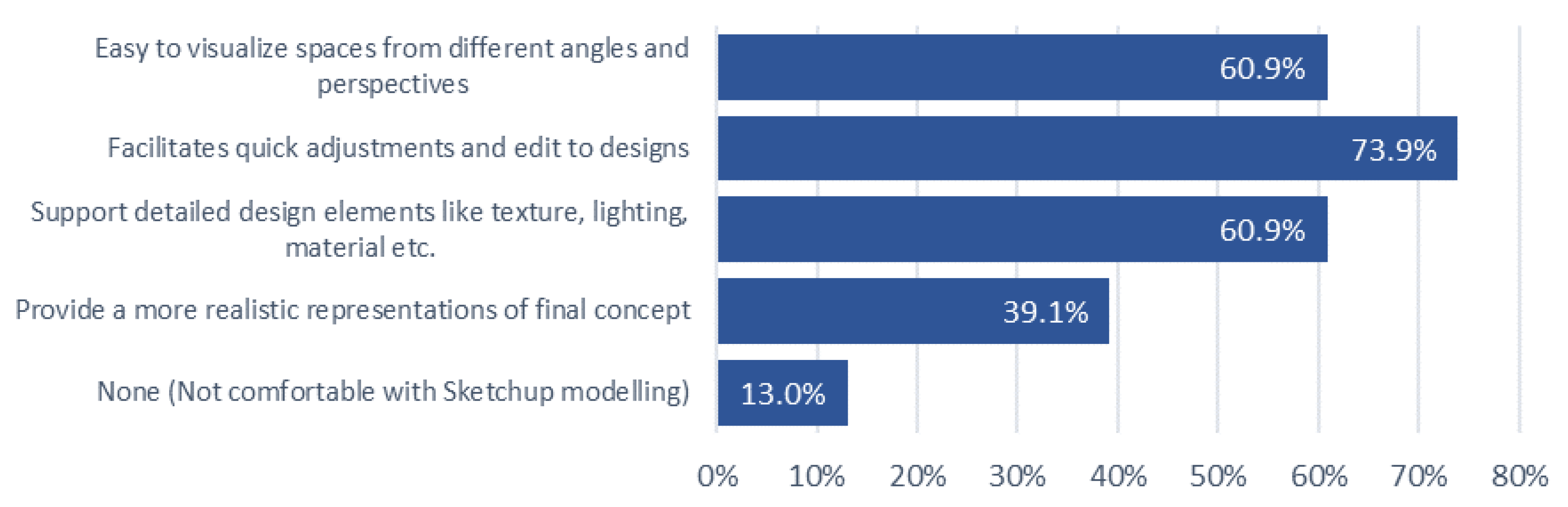

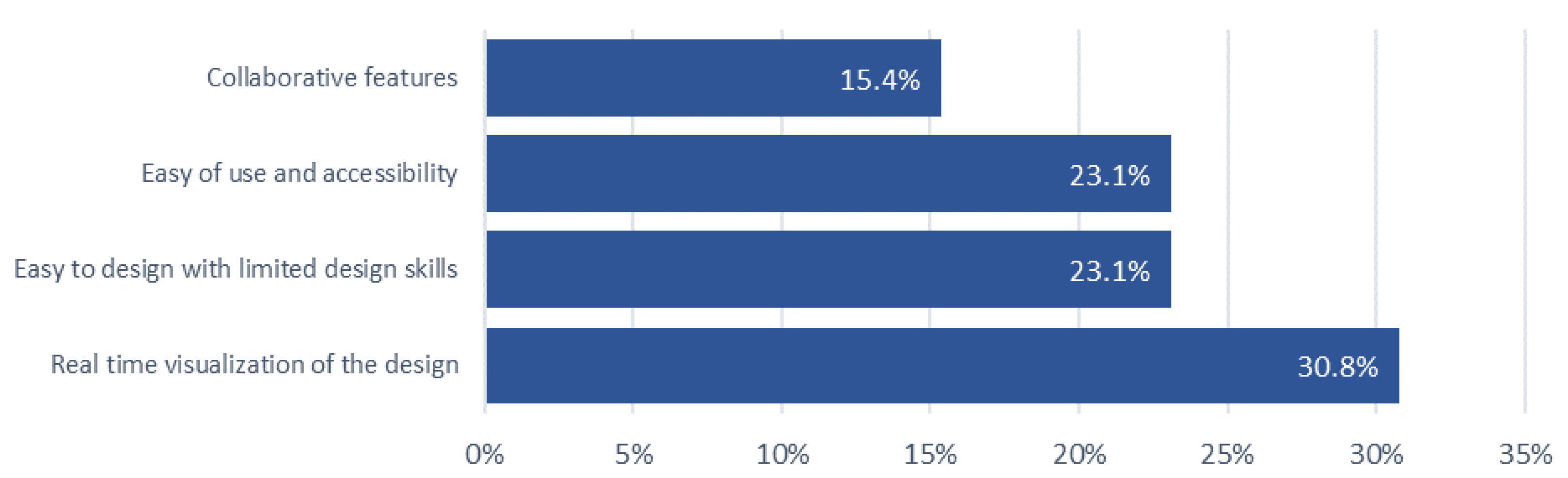

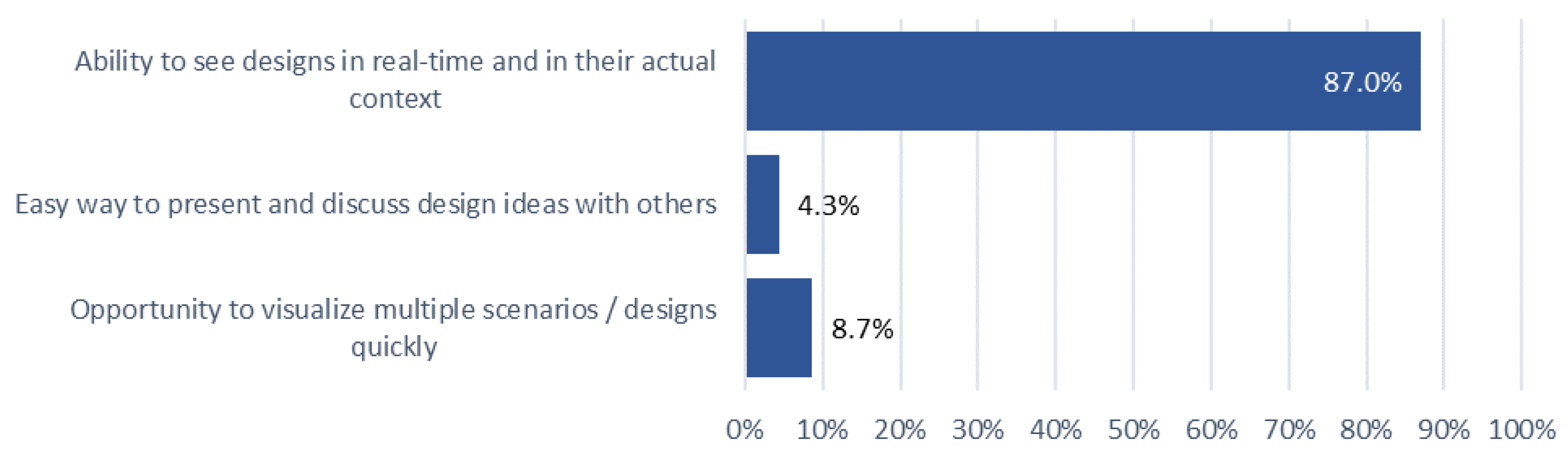

| Q5 | Mixed | What are the positives you experienced while SketchUp software (3D modelling) for placemaking? | Multiple checkboxes and text |

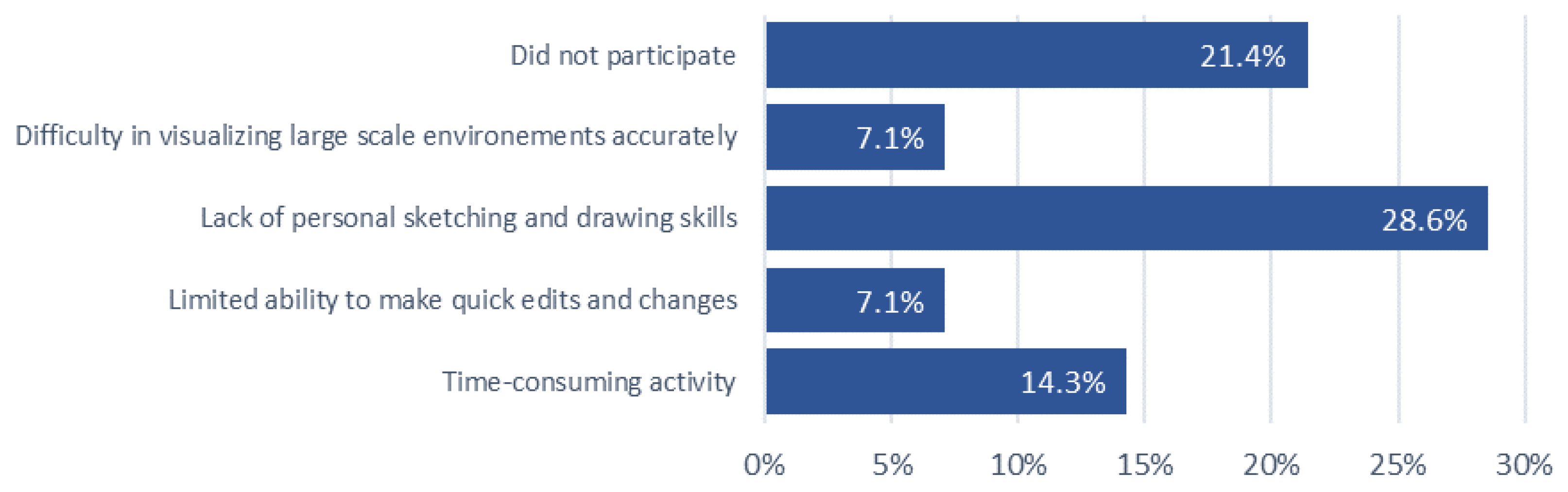

| Q6 | Mixed | What challenges did you face while using hand sketching (2D drawing) / SketchUp software (3D modelling) for placemaking? | Multiple checkboxes and text |

| Q7 | Closed-ended | To what extent do you think AR is effective in visualizing and understanding placemaking concepts? | 5-Point Likert Scale |

| Q8 | Closed-ended | How easy was it to navigate and use the AR application for placemaking? | 5-Point Likert Scale |

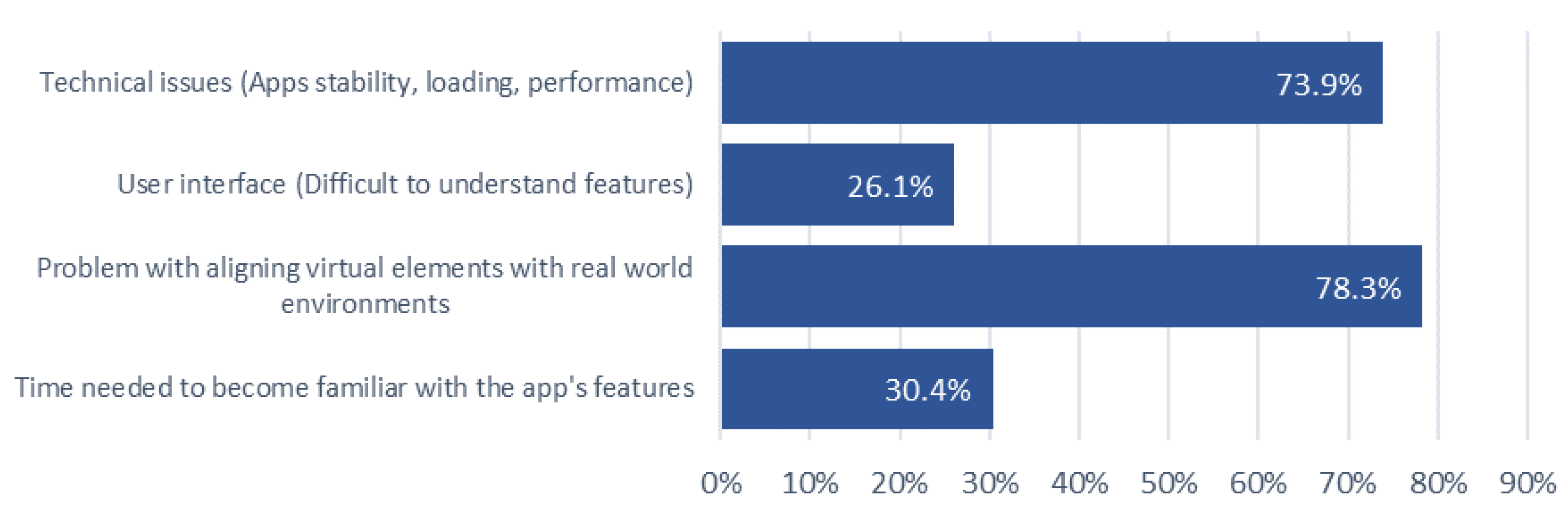

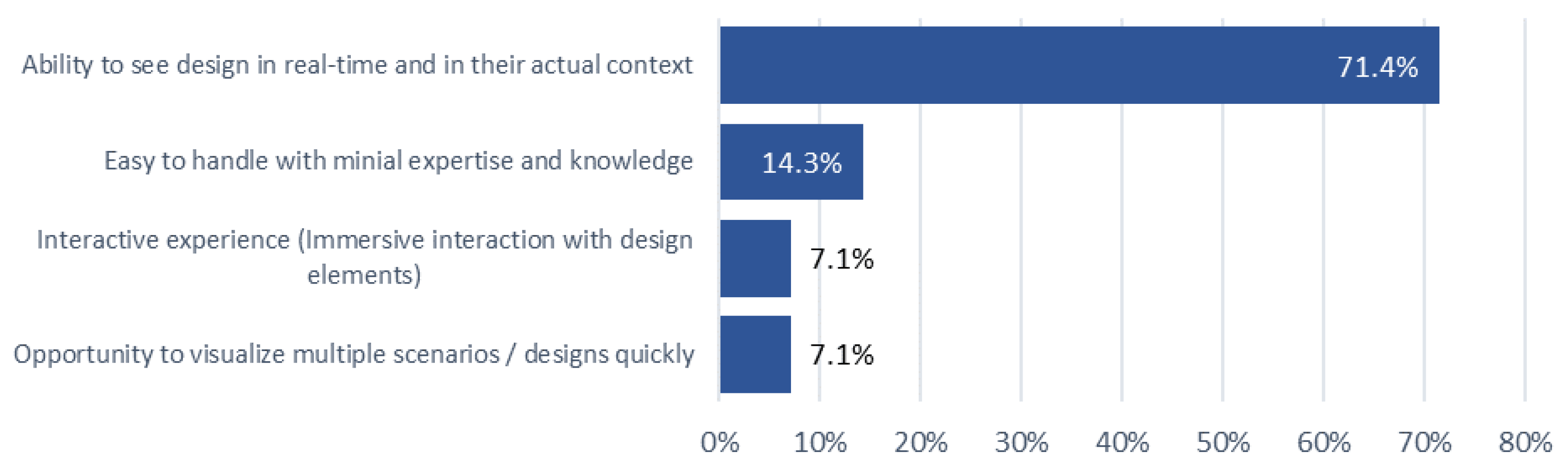

| Q9 | Mixed | What challenges did you face, and positives did you experience while using the AR app for placemaking? | Multiple checkboxes and text |

| Q10 | Closed-ended | Compared to hand sketching / 3D modelling software, do you find AR to be a better tool for placemaking? | 5-Point Likert Scale |

| Q11 | Closed-ended | Do you believe that AR can enhance your involvement in urban planning and placemaking? | 5-Point Likert Scale |

| Q12 | Closed-ended | Rate your interaction and experience with "Activities - Diversity, People's activities, Cafes etc." during placemaking activity using these tools. | 3-Point Likert Scale |

| Q13 | Closed-ended | Rate your interaction and experience with "Physical Setting - Human & Building scale, walkability, accessibility etc." during placemaking activity using these tools. | 3-Point Likert Scale |

| Q14 | Closed-ended | Rate your interaction and experience with "Imageability - attractiveness, physical comfort, attachment etc." during placemaking activity using these tools. | 3-Point Likert Scale |

| Q15 | Closed-ended | Rate app features according to your experience | 3-Point Likert Scale |

| Q16 | Open-ended | Are there any features you believe should be added or modified in the AR app? | Text |

| Q17 | Closed-ended | How willing are you to use AR applications for placemaking activities in the future? |

5-Point Likert Scale |

| Criteria | Professional | University Student | General Public | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of element | Tree | 23 (1.77) 1 | 43 (1.87) | 33 (2.36) |

| Bushes | 55 (4.23) | 104 (4.52) | 30 (2.14) | |

| Table | 10 (0.77) | 26 (1.13) | 13 (0.93) | |

| Benches | 37 (2.85) | 87 (3.78) | 28 (2.00) | |

| Lamp posts | 15 (1.15) | 35 (1.52) | 11 (0.79) | |

| Garbage bins | 1 (0.08) | 15 (0.65) | 7 (0.50) | |

| Functionality | Seating | Y – 11, N - 2 | Y – 23, N – 0 | Y – 11, N – 3 |

| Walking | Y – 13, N - 0 | Y – 17, N – 6 | Y – 8, N – 6 | |

| Lighting | Y – 7, N – 6 | Y – 19, N – 4 | Y – 8, N – 6 | |

| Greenery | Y – 7, N – 6 | Y – 20, N – 3 | Y – 11, N – 3 | |

| Physical Setting | Y – 13, N – 0, M – 0 | Y – 23, N – 0, M – 0 | Y – 6, N – 0, M – 8 | |

| User Interaction | Sociability | Y – 10, N – 0, M – 3 | Y – 18, N – 0, M – 5 | Y – 2, N – 4, M – 8 |

| Imageability | Y – 7, N – 0, M – 6 | Y – 21, N – 0, M – 2 | Y – 5, N – 8, M – 1 | |

| Incorporating AR features | Designing | Y – 9, N – 0, M – 4 | Y – 23, N – 0, M – 0 | Y – 5, N – 0, M – 8 |

| Visualizing | Y – 0, N – 0, M – 13 | Y – 23, N – 0, M – 0 | Y – 5, N – 0, M – 8 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).