Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

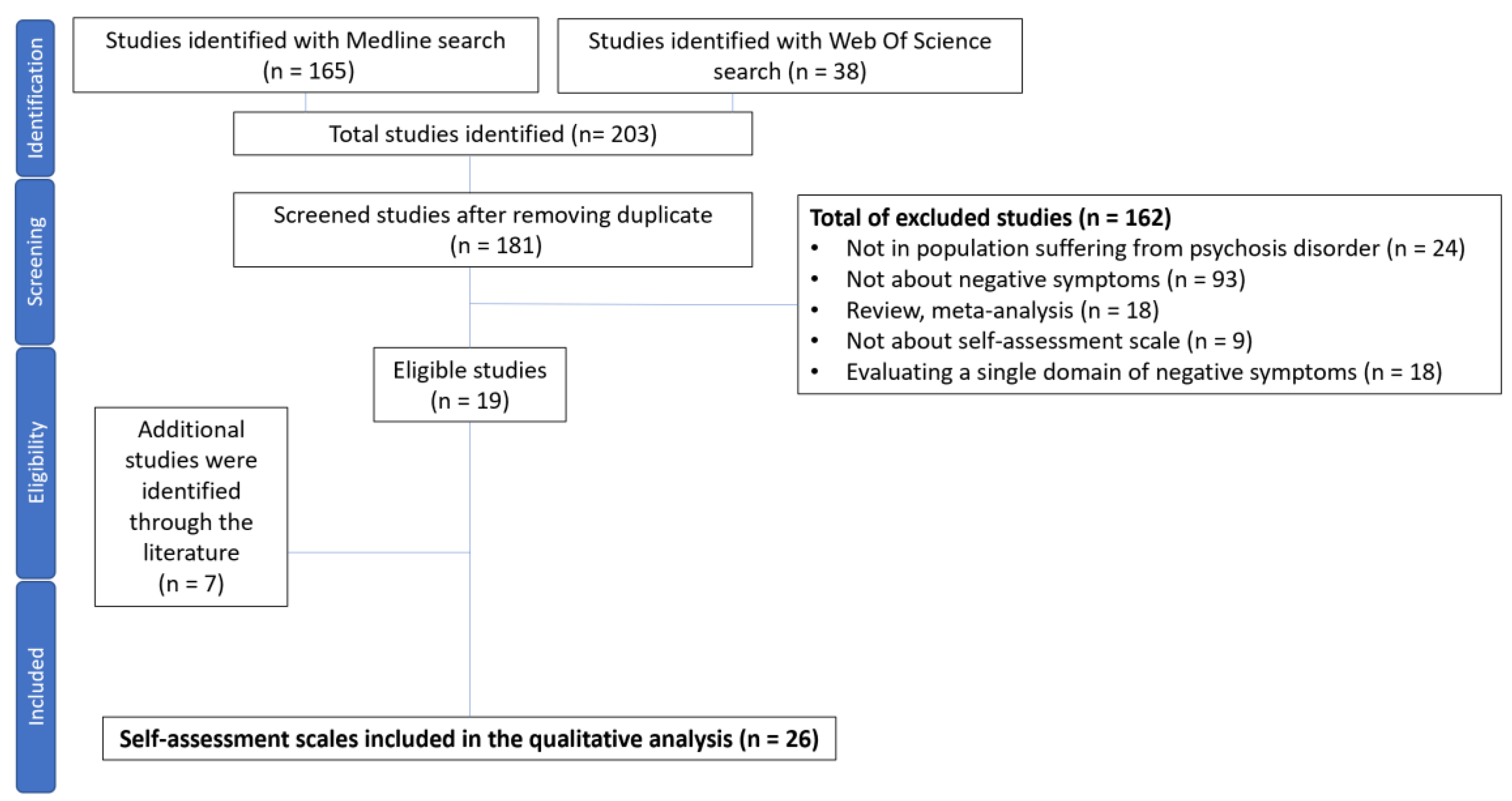

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. COSMIN Methodology

2.2. Search Method

2.3. Assessing the Risk of Bias and Updated Criteria for Good Measurement Properties

2.4. GRADE Approach

- -

- No downgrade: Multiple studies of at least adequate quality, or a single study of very good quality available

- -

- - 1 downgrade -serious risk of bias: Multiple studies of doubtful quality available, or only one study of adequate quality

- -

- - 2 downgrades-very serious risk of bias: Multiple studies of inadequate quality, or only one study of doubtful quality available

- -

- - 3 downgrades - extremely serious risk of bias: Only one study of inadequate quality available.

2.5. Recommendations

3. Results

3.1. The Subjective Experience of Negative Symptoms (SENS)

3.1.1. Risk of Bias and Criteria for Good Measurement Properties

3.1.2. GRADE Evaluation

3.2. The Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms – Self-Report (CAINS-SR)

3.2.1. Risk of Bias and Criteria for Good Measurement Properties

3.2.2. GRADE Evaluation

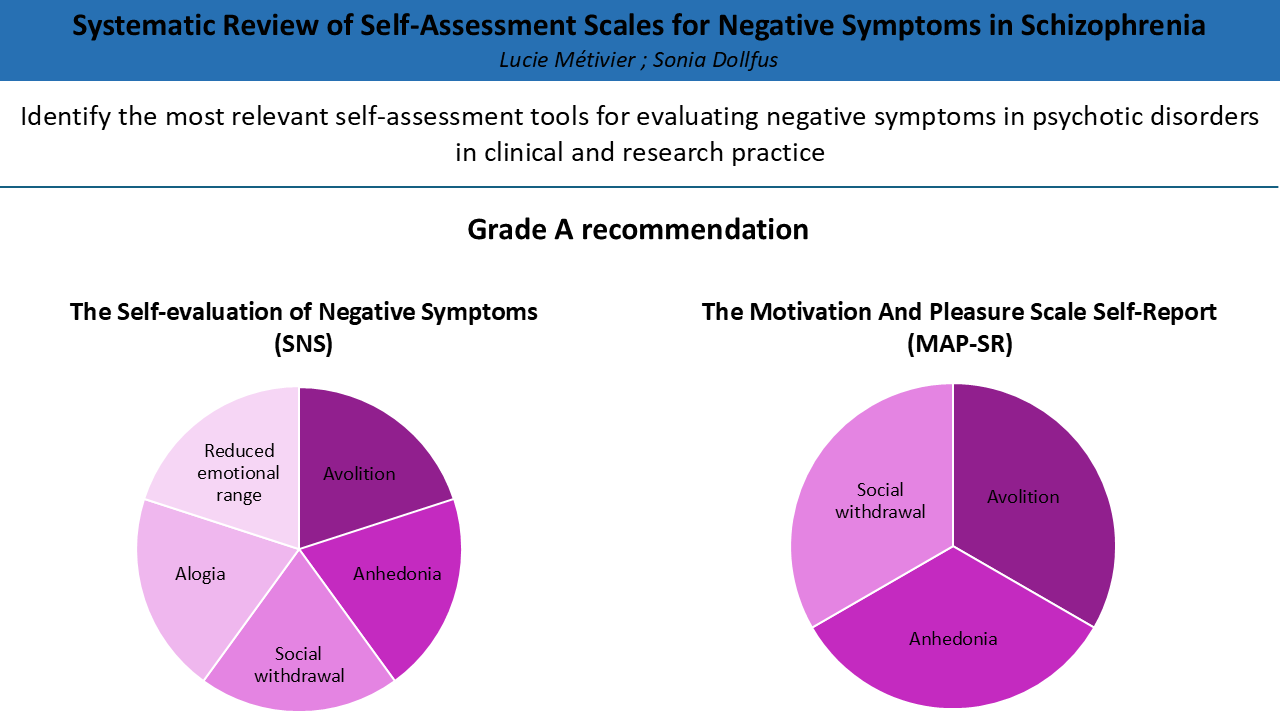

3.3. The Motivation and Pleasure Scale Self-Report (MAPS-SR)

3.3.1. Risk of Bias and Criteria for Good Measurement Properties

3.3.2. GRADE Evaluation

3.4. The Self Evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS)

3.4.1. Risk of Bias and Criteria for Good Measurement Properties

3.4.2. GRADE Evaluation

3.5. The Negative Symptoms Inventory Self-Report (NSI-SR)

3.5.1. Risk of Bias and Criteria for Good Measurement Properties

3.5.2. GRADE Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist item | Location where item is reported |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Yes |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | Yes |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | Yes |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Yes |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | Yes |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | Yes |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Yes |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Yes |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Yes |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g. for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | Yes |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g. participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | Yes | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Yes |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g. risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | NA |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g. tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | Yes |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | NA | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | Yes | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | Yes | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g. subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | NA | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | NA | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | NA |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | Yes |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | Yes |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | NA | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | Yes |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | Yes |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | NA |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | Yes |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | Yes | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | Yes | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | NA | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | NA |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | Yes |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | Yes |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | Yes | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | Yes | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | Yes | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | Yes |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | Yes | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | Yes | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | Yes |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | Yes |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | Yes |

References

- Kirkpatrick, B.; Fenton, W.S.; Carpenter, W.T.; Marder, S.R. The NIMH-MATRICS Consensus Statement on Negative Symptoms. Schizophr Bull 2006, 32, 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbj053. [CrossRef]

- Sicras-Mainar, A.; Maurino, J.; Ruiz-Beato, E.; Navarro-Artieda, R. Impact of Negative Symptoms on Healthcare Resource Utilization and Associated Costs in Adult Outpatients with Schizophrenia: A Population-Based Study. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 225. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0225-8. [CrossRef]

- Montvidas, J.; Adomaitienė, V.; Leskauskas, D.; Dollfus, S. Health-Related Quality of Life Prediction Using the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms Scale (SNS) in Patients with Schizophrenia. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 2021, 75, S21–S21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2021.2019934. [CrossRef]

- Stahl, S.M.; Buckley, P.F. Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia: A Problem That Will Not Go Away. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007, 115, 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00947.x. [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, T.M.; Dollfus, S.; Lyne, J. Current Developments and Challenges in the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. Schizophr Res 2017, 186, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.02.035. [CrossRef]

- Wehr, S.; Weigel, L.; Davis, J.; Galderisi, S.; Mucci, A.; Leucht, S. Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS): A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. Schizophr Bull 2024, 50, 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbad137. [CrossRef]

- Weigel, L.; Wehr, S.; Galderisi, S.; Mucci, A.; Davis, J.M.; Leucht, S. Clinician-Reported Negative Symptom Scales: A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. Schizophr Bull 2024, sbae168. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbae168. [CrossRef]

- Weigel, L.; Wehr, S.; Galderisi, S.; Mucci, A.; Davis, J.; Giordano, G.M.; Leucht, S. The Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS): A Systematic Review of Measurement Properties. Schizophrenia (Heidelb) 2023, 9, 45. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41537-023-00380-x. [CrossRef]

- Dollfus, S.; Delouche, C.; Hervochon, C.; Mach, C.; Bourgeois, V.; Rotharmel, M.; Tréhout, M.; Vandevelde, A.; Guillin, O.; Morello, R. Specificity and Sensitivity of the Self-Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SNS) in Patients with Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 2019, 211, 51–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2019.07.012. [CrossRef]

- Lindström, E.; Lewander, T.; Malm, U.; Malt, U.F.; Lublin, H.; Ahlfors, U.G. Patient-Rated versus Clinician-Rated Side Effects of Drug Treatment in Schizophrenia. Clinical Validation of a Self-Rating Version of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale (UKU-SERS-Pat). Nord J Psychiatry 2001, 55 Suppl 44, 5–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/080394801317084428. [CrossRef]

- Eisen, S.V.; Dickey, B.; Sederer, L.I. A Self-Report Symptom and Problem Rating Scale to Increase Inpatients’ Involvement in Treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2000, 51, 349–353. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.51.3.349. [CrossRef]

- Niv, N.; Cohen, A.N.; Mintz, J.; Ventura, J.; Young, A.S. The Validity of Using Patient Self-Report to Assess Psychotic Symptoms in Schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2007, 90, 245–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2006.11.011. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, B.; Strauss, G.P.; Nguyen, L.; Fischer, B.A.; Daniel, D.G.; Cienfuegos, A.; Marder, S.R. The Brief Negative Symptom Scale: Psychometric Properties. Schizophr Bull 2011, 37, 300–305. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbq059. [CrossRef]

- Kring, A.M.; Gur, R.E.; Blanchard, J.J.; Horan, W.P.; Reise, S.P. The Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS): Final Development and Validation. Am J Psychiatry 2013, 170, 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010109. [CrossRef]

- Dollfus, S.; Mach, C.; Morello, R. Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms: A Novel Tool to Assess Negative Symptoms. Schizophr Bull 2016, 42, 571–578. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbv161. [CrossRef]

- Llerena, K.; Park, S.G.; McCarthy, J.M.; Couture, S.M.; Bennett, M.E.; Blanchard, J.J. The Motivation and Pleasure Scale-Self-Report (MAP-SR): Reliability and Validity of a Self-Report Measure of Negative Symptoms. Compr Psychiatry 2013, 54, 568–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.12.001. [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, S.; Mucci, A.; Dollfus, S.; Nordentoft, M.; Falkai, P.; Kaiser, S.; Giordano, G.M.; Vandevelde, A.; Nielsen, M.Ø.; Glenthøj, L.B.; et al. EPA Guidance on Assessment of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 2021, 64, e23. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.11. [CrossRef]

- Schormann, A.L.A.; Pillny, M.; Haß, K.; Lincoln, T.M. “Goals in Focus”-a Targeted CBT Approach for Motivational Negative Symptoms of Psychosis: Study Protocol for a Randomized-Controlled Feasibility Trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2023, 9, 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-023-01284-4. [CrossRef]

- Grant, P.M.; Huh, G.A.; Perivoliotis, D.; Stolar, N.M.; Beck, A.T. Randomized Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy of Cognitive Therapy for Low-Functioning Patients with Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012, 69, 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.129. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2009, 62, 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [CrossRef]

- Prinsen, C. a. C.; Mokkink, L.B.; Bouter, L.M.; Alonso, J.; Patrick, D.L.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Guideline for Systematic Reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual Life Res 2018, 27, 1147–1157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3. [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Prinsen, C. a. C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias Checklist for Systematic Reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual Life Res 2018, 27, 1171–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1765-4. [CrossRef]

- Terwee, C.B.; Mokkink, L.B.; Knol, D.L.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W. Rating the Methodological Quality in Systematic Reviews of Studies on Measurement Properties: A Scoring System for the COSMIN Checklist. Qual Life Res 2012, 21, 651–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9960-1. [CrossRef]

- Raugh, I.M.; Luther, L.; Bartolomeo, L.A.; Gupta, T.; Ristanovic, I.; Pelletier-Baldelli, A.; Mittal, V.A.; Walker, E.F.; Strauss, G.P. Negative Symptom Inventory-Self-Report (NSI-SR): Initial Development and Validation. Schizophrenia Research 2023, 256, 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2023.04.015. [CrossRef]

- Selten, J.P.; Sijben, N.E.; van den Bosch, R.J.; Omloo-Visser, J.; Warmerdam, H. The Subjective Experience of Negative Symptoms: A Self-Rating Scale. Compr Psychiatry 1993, 34, 192–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-440x(93)90047-8. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.G.; Llerena, K.; McCarthy, J.M.; Couture, S.M.; Bennett, M.E.; Blanchard, J.J. Screening for Negative Symptoms: Preliminary Results from the Self-Report Version of the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms. Schizophr Res 2012, 135, 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2011.12.007. [CrossRef]

- Overall, J.E.; Gorham, D.R. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962, 10, 799–812. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1962.10.3.799. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-L.; Ma, E.P.Y.; Lui, S.S.Y.; Cheung, E.F.C.; Cheng, K.S.; Chan, R.C.K. Validation and Extension of the Motivation and Pleasure Scale-Self Report (MAP-SR) across the Schizophrenia Spectrum in the Chinese Context. Asian J Psychiatr 2020, 49, 101971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101971. [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.; Hesse, K.; Eberle, M.-C.; Eckstein, K.N.; Zimmermann, L.; Schreiber, L.; Burmeister, C.P.; Wildgruber, D.; Klingberg, S. Self-Assessment of Negative Symptoms – Critical Appraisal of the Motivation and Pleasure – Self-Report’s (MAP-SR) Validity and Reliability. Comprehensive Psychiatry 2019, 88, 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.007. [CrossRef]

- Engel, M.; Lincoln, T.M. Motivation and Pleasure Scale-Self-Report (MAP-SR): Validation of the German Version of a Self-Report Measure for Screening Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry 2016, 65, 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.11.001. [CrossRef]

- García-Portilla, M.P.; García-Álvarez, L.; de la Fuente-Tomás, L.; Dal Santo, F.; Velasco, A.; González-Blanco, L.; Zurrón-Madera, P.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; Bobes-Bascarán, M.T.; Sáiz, P.A.; et al. Spanish Validation of the MAP-SR: Two Heads Better Than One for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia. Psicothema 2021, 33, 473–480. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2020.457. [CrossRef]

- Cernvall, M.; Bengtsson, J.; Bodén, R. The Swedish Version of the Motivation and Pleasure Scale Self-Report (MAP-SR): Psychometric Properties in Patients with Schizophrenia or Depression. Nord J Psychiatry 2024, 78, 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2024.2324060. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Jang, S.-K.; Park, S.-C.; Yi, J.-S.; Park, J.-K.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, K.-H.; Lee, S.-H. Measuring Negative Symptoms in Patients with Schizophrenia: Reliability and Validity of the Korean Version of the Motivation and Pleasure Scale-Self-Report. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016, 12, 1167–1172. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S107775. [CrossRef]

- Kay, S.R.; Fiszbein, A.; Opler, L.A. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987, 13, 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, N.C. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): Conceptual and Theoretical Foundations. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1989, 49–58.

- Loas, G.; Monestes, J.-L.; Ameller, A.; Bubrovszky, M.; Yon, V.; Wallier, J.; Berthoz, S.; Corcos, M.; Thomas, P.; Gard, D.E. Traduction et Étude de Validation de La Version Française de l’échelle d’expérience Temporelle Du Plaisir (EETP, Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale [TEPS], Gard et al., 2006) : Étude Chez 125 Étudiants et Chez 162 Sujets Présentant Un Trouble Psychiatrique. Annales Médico-psychologiques, revue psychiatrique 2009, 167, 641–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2009.09.002. [CrossRef]

- Hajj, A.; Hallit, S.; Chamoun, K.; Sacre, H.; Obeid, S.; Haddad, C.; Dollfus, S.; Rabbaa Khabbaz, L. Validation of the Arabic Version of the “Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms” Scale (SNS). BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 240. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02647-4. [CrossRef]

- Montvidas, J.; Adomaitienė, V.; Leskauskas, D.; Dollfus, S. Validation of the Lithuanian Version of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms Scale (SNS). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 2021, 75, 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2020.1862295. [CrossRef]

- Polat, I.; Ince Guliyev, E.; Elmas, S.; Karakaş, S.; Aydemir, Ö.; Üçok, A. Validation of the Turkish Version of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms Scale (SNS). Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2022, 26, 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/13651501.2022.2082985. [CrossRef]

- Samochowiec, J.; Jabłoński, M.; Plichta, P.; Piotrowski, P.; Stańczykiewicz, B.; Bielawski, T.; Misiak, B. The Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms in Differentiating Deficit Schizophrenia: The Comparison of Sensitivity and Specificity with Other Tools. Psychopathology 2023, 56, 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1159/000529244. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Chen, J.; Tian, H.; Lin, C.; Zhu, J.; Ping, J.; Chen, L.; Zhuo, C.; Jiang, D. Validity and Reliability of a Chinese Version of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms. Brain Behav 2023, 13, e2924. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2924. [CrossRef]

- Goldring, A.; Borne, S.; Hefner, A.; Thanju, A.; Khan, A.; Lindenmayer, J.-P. The Psychometric Properties of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms Scale (SNS) in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia (TRS). Schizophrenia Research 2020, 224, 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.08.008. [CrossRef]

- Hervochon, C.; Bourgeois, V.; Rotharmel, M.; Duboc, J.-B.; Le Goff, B.; Quesada, P.; Campion, D.; Dollfus, S.; Guillin, O. [Validation of the French version of the self-evaluation of negative symptoms (SNS)]. Encephale 2018, 44, 512–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2017.10.002. [CrossRef]

- Wójciak, P.; Górna, K.; Domowicz, K.; Jaracz, K.; Gołębiewska, K.; Michalak, M.; Rybakowski, J. Polish Version of the Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS). Psychiatr Pol 2019, 53, 541–549. https://doi.org/10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/91490. [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, L.; Martínez-Cao, C.; Bobes-Bascarán, T.; Portilla, A.; Courtet, P.; de la Fuente-Tomás, L.; Velasco, Á.; González-Blanco, L.; Zurrón-Madera, P.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; et al. Validation of a European Spanish-Version of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS) in Patients with Schizophrenia. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Engl Ed) 2020, S1888-9891(20)30036-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2020.04.011. [CrossRef]

- Mazhari, S.; Karamooz, A.; Shahrbabaki, M.E.; Jahanbakhsh, F.; Dollfus, S. Validity and Reliability of a Persian Version of the Self- Evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS). BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 516. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03521-7. [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, L.; Martínez-Cao, C.; Bobes-Bascarán, T.; Portilla, A.; Courtet, P.; de la Fuente-Tomás, L.; Velasco, Á.; González-Blanco, L.; Zurrón-Madera, P.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E.; et al. Validation of a European Spanish-Version of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS) in Patients with Schizophrenia. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Engl Ed) 2022, 15, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsmen.2022.01.005. [CrossRef]

- Dollfus, S.; Mucci, A.; Giordano, G.M.; Bitter, I.; Austin, S.F.; Delouche, C.; Erfurth, A.; Fleischhacker, W.W.; Movina, L.; Glenthøj, B.; et al. European Validation of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS): A Large Multinational and Multicenter Study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 826465. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.826465. [CrossRef]

- Tam, M.H.W.; Ling-Ling, W.; Cheng, K.; Wong, J.O.Y.; Cheung, E.F.C.; Lui, S.S.Y.; Chan, R.C.K. Latent Structure of Self-Report Negative Symptoms in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Preliminary Study. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2021, 61, 102680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102680. [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J.; Guessoum, S.B.; Tebeka, S.; Le Strat, Y.; Dubertret, C. Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms in Adolescent and Young Adult First Psychiatric Episodes. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 2020, 103, 109988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109988. [CrossRef]

- Métivier, L.; Mauduy, M.; Beaunieux, H.; Dollfus, S. Revealing the Unseen: Detecting Negative Symptoms in Students. JCM 2024, 13, 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13061709. [CrossRef]

- Hajj, A.; Hallit, S.; Chamoun, K.; Sacre, H.; Obeid, S.; Haddad, C.; Dollfus, S.; Rabbaa Khabbaz, L. Validation of the Arabic Version of the “Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms” Scale (SNS). BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 240. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02647-4. [CrossRef]

- Wójciak, P.; Górna, K.; Domowicz, K.; Jaracz, K.; Szpalik, R.; Michalak, M.; Rybakowski, J. Polish Version of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS). Psychiatr Pol 2019, 53, 551–559. https://doi.org/10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/97352. [CrossRef]

- Haro, J.M.; Kamath, S.A.; Ochoa, S.; Novick, D.; Rele, K.; Fargas, A.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Rele, R.; Orta, J.; Kharbeng, A.; et al. The Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia Scale: A Simple Instrument to Measure the Diversity of Symptoms Present in Schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2003, 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.107.s416.5.x. [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, B.; Saoud, J.B.; Strauss, G.P.; Ahmed, A.O.; Tatsumi, K.; Opler, M.; Luthringer, R.; Davidson, M. The Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS): Sensitivity to Treatment Effects. Schizophr Res 2018, 197, 269–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.11.031. [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, B.N.; Goldman, R.S.; Alphs, L.D. Validation of the 16-Item Negative Symptom Assessment. J Psychiatr Res 1993, 27, 253–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(93)90036-2. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Testal, J.F.; Perona-Garcelán, S.; Dollfus, S.; Valdés-Díaz, M.; García-Martínez, J.; Ruíz-Veguilla, M.; Senín-Calderón, C. Spanish Validation of the Self-Evaluation of Negative Symptoms Scale SNS in an Adolescent Population. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 327. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2314-1. [CrossRef]

- Gard, D.E.; Gard, M.G.; Kring, A.M.; John, O.P. Anticipatory and Consummatory Components of the Experience of Pleasure: A Scale Development Study. Journal of Research in Personality 2006, 40, 1086–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.11.001. [CrossRef]

- Raffard, S.; Norton, J.; Van der Linden, M.; Lançon, C.; Benoit, M.; Capdevielle, D. Psychometric Properties of the BIRT Motivation Questionnaire (BMQ), a Self-Measure of Avolition in Individuals with Schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2022, 147, 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.01.033. [CrossRef]

- Tsui, H.K.H.; Wong, T.Y.; Sum, M.Y.; Chu, S.T.; Hui, C.L.M.; Chang, W.C.; Lee, E.H.M.; Suen, Y.; Chen, E.Y.H.; Chan, S.K.W. Comparison of Negative Symptom Network Structures Between Patients With Early and Chronic Schizophrenia: A Network and Exploratory Graph Analysis. Schizophr Bull 2024, sbae135. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbae135. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, G.P.; Ahmed, A.O.; Young, J.W.; Kirkpatrick, B. Reconsidering the Latent Structure of Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: A Review of Evidence Supporting the 5 Consensus Domains. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2018, 45, 725. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sby169. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ang, M.S.; Yee, J.Y.; See, Y.M.; Lee, J. Predictors of Functioning in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: The Role of Negative Symptoms and Neurocognition. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1444843. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1444843. [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, A.M.; McKenna, P.J.; Lund, C.E.; Mannuzza, S. Rating of Negative Symptoms Using the High Royds Evaluation of Negativity (HEN) Scale. Br J Psychiatry Suppl 1989, 89–92.

- Torous, J.; Bucci, S.; Bell, I.H.; Kessing, L.V.; Faurholt-Jepsen, M.; Whelan, P.; Carvalho, A.F.; Keshavan, M.; Linardon, J.; Firth, J. The Growing Field of Digital Psychiatry: Current Evidence and the Future of Apps, Social Media, Chatbots, and Virtual Reality. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20883. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Miller, L.C. Just-in-the-Moment Adaptive Interventions (JITAI): A Meta-Analytical Review. Health Communication 2020, 35, 1531–1544. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1652388. [CrossRef]

|

Scale |

Population | Mean Age (SD) | Gender(female %) | Countries validation |

Negative Symptoms domains |

Number of items | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Subjective Experience of Negative Symptoms (SENS) Selten et al., 1993 [25] |

52 patients with schizophrenia |

39.5 (10.8) |

34.6 |

Netherlands |

Anhedonia/asociality Avolition/apathy Affective flattening Alogia Attention |

21 | - |

|

Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms Self-Report (CAINS-SR) Park et al., 2020 [26] |

41 patients with schizophrenia32 patients with schizo-affective disorders |

47.1 (8.36) |

36.2 |

North America |

Anhedonia Avolition Alogia Blunted affect Asociality |

30 | - |

|

Motivation And Pleasure Scale Self-Report (MAPS-SR) Llerena et al., 2013 [16] Engel et al., 2016 [30] Wang et al., 2020 [28] Kim et al., 2016 [33] Richter et al., 2019 [29] Garcia-Portilla et al., 2021 [31] Cernvall et al., 2024 [32] |

37 patients with schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorders 50 patients with schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorders 150 patients with schizophrenia 139 patients with schizophrenia 93 patients with schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorder 174 patients with schizophrenia 33 patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders |

50.16 (5.12) 35.70 (10.36) 46.47 (8.37) 38.9 (11.1) 38.99 (10.99) 36.7 (12.2) 40.0 (11.0) |

35.1 44 51.3 45.3 33.3 37.4 36 |

North America Germany China Korea German Spain Sweden |

Anhedonia Avolition Social withdrawal |

15 | - |

|

Self-evaluation of Negative Symptoms (SNS) Dollfus et al., 2016 [15] Hervochon et al., 2018 [43] Wojciak et al., 2019 [44] Dollfus et al., 2019 [9] Hajj et al., 2019 [37] Mallet et al., 2020 [50] Garcia-Alvarez et al., 2020 [45] Goldring et al., 2020 [42] Tam et al., 2021 [49] Montvidas et al., 2021 [38] Mazhari et al., 2021 [46] Garcia-Alvarez et al., 2022 [47] Polat et al., 2022 [39] Dollfus et al., 2022 [48] Samochowiec et al., 2023 [40] Chen et al., 2023 [41] Métivier et al, 2024 [51] |

23 patients with schizophrenia 26 patients with schizo-affective disorders 60 patients with schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorders 40 patients with schizophrenia 109 patients with schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorders 99 healthy controls 206 patients with schizophrenia 29 patients with schizophrenia 22 patients with depressive disorder 59 healthy controls 104 patients with schizophrenia 50 patients with resistant schizophrenia 204 patients with schizophrenia 67 patients with schizophrenia 50 patients with schizophrenia 104 patients with schizophrenia 75 patients with schizophrenia 245 patients with schizophrenia 82 patients with schizophrenia 200 patients with schizophrenia 367 students with ultra-high risk of psychosis or major depressive disorders 1761 healthy students |

36.7 (11.6) 40.6 (10.7) 44.0 (13.0) 38.9 (11.3) 28.8 (13.2) 52.68 (12.0) 19.4 (3.0) 18.0 (2.0) 20.4 (2.8) 40.1 (13.9) 43.8 (11.19) 49.36 (10.23) 41.51 (13.76) 39.5 (11.1) 40.1 (13.9) 21.91 (5.44) 37.4 (11.3) NR 35.2 (3.9) NR NR |

20.4 20 50 NR NR 56.8 36.8 59.1 62.7 35.6 12 51.47 64.2 32 35.6 36 37 NR 53.5 NR NR |

27 languages (www.sns-dollfus.com/fr France France Poland France Lebanon France Spain North America Hong-Kong and China Lithuania Iran Spain Turkey European countries Poland China France |

Anhedonia Avolition Alogia Reduced emotional range Social withdrawal |

20 | 5 min |

|

Negative Symptoms Inventory Self-Report (NSI-SR) Raugh et al., 2023 [24] |

32 patients with schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorders 25 patients with clinical high-risk of psychosis |

40.12 (13.25) 41.32 (9.43) |

75 83.9 |

North America |

Anhedonia Avolition Social withdrawal |

11 | Few minutes |

| SENS [25] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Measurement property (no, of study assessing measurement property) |

Cosmin risk of bias |

Update criteria of good measurement |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Very good | Adequate | Doubtful | Inadequate | + | - | ? | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Structural validity (n = 0) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Internal consistency (n = 1) |

0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reliability (n = 1) |

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Criterion validity (n = 0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hypotheses testing for construct validity convergent validity (n = 0) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hypotheses testing for construct validity discriminant validity (n = 0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quality of evidence (GRADE) | Very Low | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recommendation | C | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAINS-SR [26] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Measurement property (no, of study assessing measurement property) |

Cosmin risk of bias |

Update criteria of good measurement |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Very good | Adequate | Doubtful | Inadequate | + | - | ? | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Structural validity (n = 0) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Internal consistency (n = 1) |

0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reliability (n = 0) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Criterion validity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hypotheses testing for construct validity convergent validity (n = 1) |

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hypotheses testing for construct validity discriminant validity (n = 1) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quality of evidence (GRADE) | Very Low | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recommendation | C | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MAP-SR [16,28,29,30,31,32,33] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Measurement property (no, of study assessing measurement property) |

Cosmin risk of bias |

Update criteria of good measurement |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Very good | Adequate | Doubtful | Inadequate | + | - | ? | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Structural validity (n = 2) [28,29] |

1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Internal consistency (n = 7) [16,28,29,30,31,32,33] |

2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reliability (n = 2) [28,29] |

0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Criterion validity (n = 0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hypotheses testing for construct validity convergent validity (n = 7) [16,28,29,30,31,32,33] |

2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hypotheses testing for construct validity discriminant validity (n = 7) [16,28,29,30,31,32,33] |

2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quality of evidence (GRADE) | Moderate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recommendation | A | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SNS [9,15,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Measurement property (no, of study assessing measurement property) |

Cosmin risk of bias |

Update criteria of good measurement |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Very good | Adequate | Doubtful | Inadequate | + | - | ? | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Structural validity (n = 9) [15,37,38,39,40,41,42,48,49] |

3 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Internal consistency (n = 12) [15,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] |

1 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reliability (n = 4) [15,37,42,43] |

2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Criterion validity (n = 5) [9,40,41,50,51] | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hypotheses testing for construct validity convergent validity (n = 13) [15,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] |

8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hypotheses testing for construct validity discriminant validity (n = 9) [15,38,39,42,43,45,47,48,52] |

3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quality of evidence (GRADE) | Moderate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recommendation | A | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NSI-SR [24] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Measurement property (no, of study assessing measurement property) |

Cosmin risk of bias |

Update criteria of good measurement |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Very good | Adequate | Doubtful | Inadequate | + | - | ? | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Structural validity (n = 1) |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Internal consistency (n = 1) |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reliability (n = 1) |

0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Criterion validity (n = 0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hypotheses testing for construct validity convergent validity (n = 1) |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hypotheses testing for construct validity discriminant validity (n = 1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Quality of evidence (GRADE) | Low | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recommendation | B | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).