1. Introduction

Computed tomography (CT) and Computer-aided design/computer-assisted manufacture (CAD/CAM) technologies have significantly enhanced implant surgery. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) imaging, intraoral surface scanning, and three-dimensional (3D) surgical planning software have allowed clinicians to analyze the patient's anatomic structures and prosthetic parameters and virtually plan the optimal implant position and direction [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Surgical guides are essential in this workflow as they transfer virtual planning to the operative field, improving the accuracy and predictability of implant placement [

5,

6].

However, as surgical guides may ensure matching the planned and actual positions of the implants, their accuracy is essential, even if this depends on cumulative and interactive possible errors, ranging from data acquisition, management, merging, guide stabilization, and bone characteristics to dimensional stability [

7].

Additionally, several factors, including manufacturing and post-processing, printing materials, and environmental exposure, can impact the dimensional stability of 3D surgical guides. Another critical aspect is sterilization, which is needed to prevent infections and post-operative complications. Indeed, surgical guides, coming into contact with the patient's blood, oral tissues and exposed bone, are subject, as other medical devices, to the same safety standards set by EU Medical Device Regulation guidelines and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, USA) [

8,

9,

10].

Numerous studies have recently examined how printing materials, processing and post-processing technology, and sterilization methods can affect potential changes in the dimensional stability of 3D surgical guides [

11].

Knowing this information before the clinical use of surgical guides is important to understand their behaviour in surgical procedures and making informed decisions, especially in light of the increasing diffusion of in-house manufacturing. Therefore, the present in-vitro study aimed to investigate the effect of Light Crystal Display (LCD) 3D printing technology, steam sterilization and storage times on the dimensional stability of SGO1 polymer resin for manufacturing 3D surgical guides.

The null hypothesis was that different LCD-3D printers, sterilization and storage times would not significantly affect the accuracy of the test bodies manufactured with the resin tested.

2. Materials and Methods

The manuscript was drafted in accordance with the modified Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for in vitro studies on dental materials [

12].

2.1. Study Design

In this in-vitro study, the Shining 3D surgical guide resin SG01 (chemical composition: phenyl bis (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)-phosphine oxide, Polymeric urethane acrylate, 2-Propen-1-one, 1-(4-morpholinyl), (Octahydro-4,7-methano-1H-indenediyl)bis(methylene) diacrylate, Ethoxylated Bisphenol A, Poly[oxy(methyl-1,2-ethanediyl)], α,α'-(2,2-dimethyl-1,3-propanediyl)bis[ω-[(1-oxo-2-propen-1-yl)oxy]), was used as the printing material. This transparent, biocompatible photopolymer resin is certified by the China FDA as a Class I medical device and meets ISO 10993 standards. The resin is designed explicitly for 3D-printed customized dental models that are non-implantable and can be used for body contact for up to 24 hours.

The selected LCD-3D printers were AccuFab-L4D (Shining 3D Tech. Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China), Elegoo Mars Pro 3 (Elegoo Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), and Zortrax Inspire (Zortrax S.A., Olsztyn, Poland) outlined in

Table 1.

Test bodies were used as a reference because they are the simplest benchmark objects for evaluating the dimensional stability of 3D printing resin [

13].

The study protocol involved manufacturing 5 different test body designs, each printed 5 times using three LCD-3D printers (total=75) and evaluating dimensional changes at four different time points: immediately after printing and post-processing (T0), one month after (T1), immediately after sterilization (T2), and one month after (T3).

2.2. Test Bodies Manufacturing

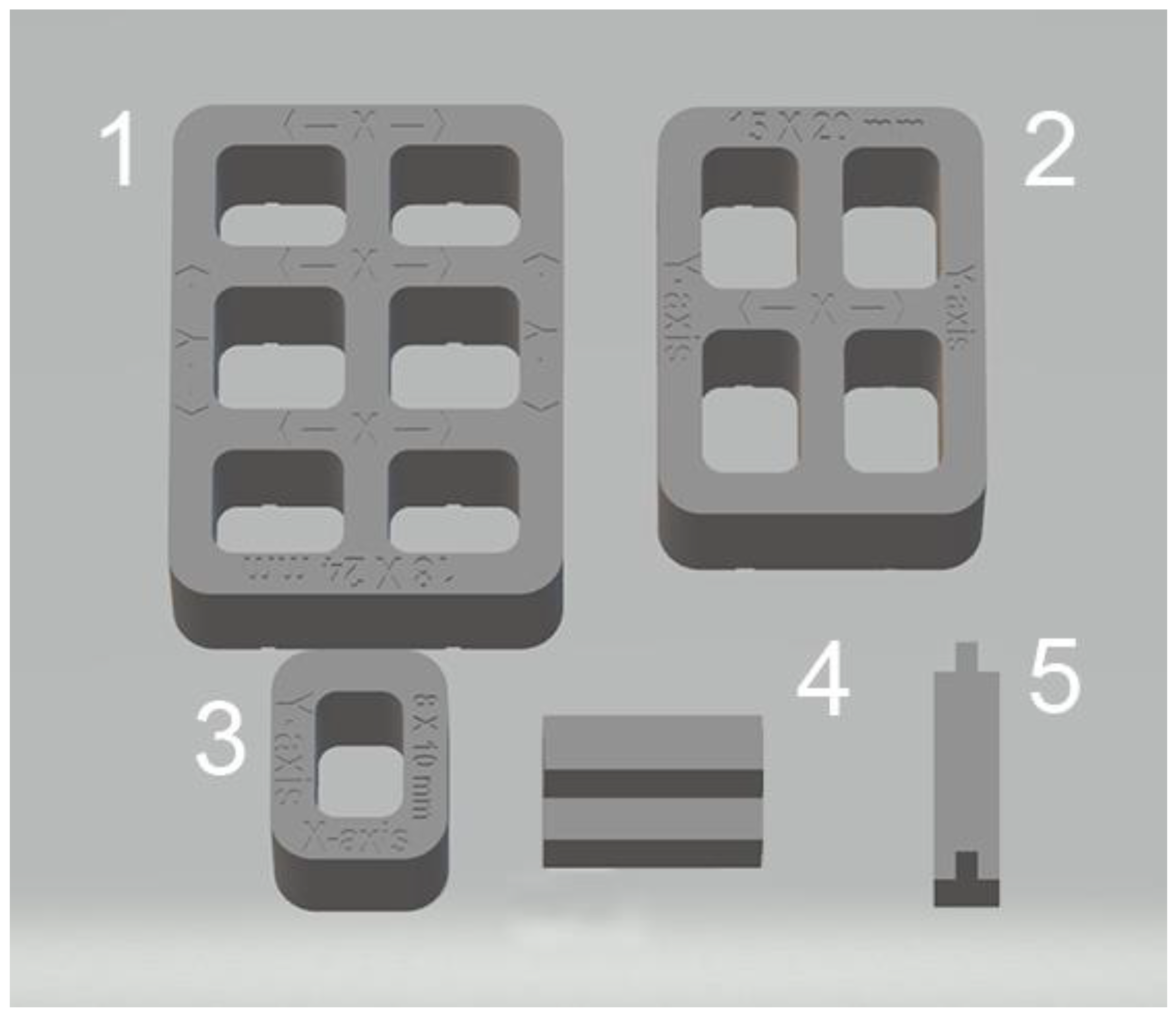

Test bodies were designed in five different geometric shapes and dimensions using a computer-aided design (CAD) software program (SolidWorks 3D CAD, Dassault Systèmes) to replicate implant surgical guide characteristics (Fig.1).

Figure 1.

Shapes and Cad reference values in mm of test bodies designs: 1) x-axis=18, y-axis= 24; 2) x-axis=15, y-axis= 20; 3) x-axis=8, y-axis=10; 4) thickness = 2; 5; thickness = 1. .

Figure 1.

Shapes and Cad reference values in mm of test bodies designs: 1) x-axis=18, y-axis= 24; 2) x-axis=15, y-axis= 20; 3) x-axis=8, y-axis=10; 4) thickness = 2; 5; thickness = 1. .

The CAD files were exported as a standard tessellation language (STL) file format and then imported into the respective slicing software of the three 3D printers selected to manufacture 25 test bodies from each. Each test body was positioned on the build platform at a 0° orientation without additional support structures to minimize potential deformation due to uneven thermal or mechanical stresses during printing and the support removal. The same specific parameters for Shining 3D surgical guide resin SG01 (100 µm layer printing and 405 nm wavelength) were set up in the printers' software to optimize the resin's curing process and prevent warping or shrinkage. Each test body was labelled for future identification using a letter for the printer and a number for the design.

After 3D printing, all 75 test bodies underwent post-processing using the Shining 3D FabWash system (Shining 3D Tech. Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) to remove any uncured resin from the print surface, and Shining3D FabCure 2 Post-curing unit (Shining 3D Tech. Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) to maximize the material’s mechanical properties. The washing was an automatic process involving a 6-minute bath in 90% isopropyl alcohol (IPA) and air drying overnight. For post-curing, each side was exposed to a powerful UV light emitted by 30 multi-directional LEDs for 5 minutes, as recommended by the resin manufacturer.

Following post-processing, test bodies were measured, sealed in separate plastic bags, and stored at room temperature. One month later, they were measured again, placed in separate sealed sterilization pouches, and autoclaved at 134°C and 2 bar for 10 minutes. The steam sterilization method was chosen because it is widely used in medical and dental practices and effectively ensures sterility without introducing chemical residues.

2.3. Dimension Assessment

Test bodies were measured at four different time points using a digital calliper (Mitutoyo America, Aurora, Illinois, USA) with an accuracy of ±0.03 mm and a resolution of 0.01 mm. Dimensional changes were assessed after the 3D printing and post-processing at T0 and following sterilization at T2. Measures at T1 and T3 referred to the time frames typically elapsing between production and sterilization and between sterilization and the intraoperative use of the surgical guides, respectively.

Measurements of the linear dimensions (distances between fixed points) and thicknesses taken on test bodies were compared to the known standard dimensions of the five virtual designs. The CAD reference values for the five test bodies (

Figure 1) were:18 mm (x-axis) and 24 mm (y-axis) for sample 1; 15 mm (x-axis) and 20 mm (y-axis) for sample 2; 8 mm (x-axis) and 10 mm (y-axis) for sample 3; 2 mm thickness (z-axis) for sample 4; 1 mm thickness (z-axis) for sample 5. The average of these eight CAD reference values resulted in an overall CAD reference value of 12.25 mm. Identifying nine measurements allowed an accurate dimensional evaluation of each group of test bodies.

All data were collected in triplicate by two blinded examiners, and the averages were used to assess dimensional changes.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were presented as means (± standard deviations). The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to assess the normality of the data distribution. Box plots were used to identify any potential outliers within the data. A two-way ANOVA was conducted on normally distributed data to assess the effects of printer type and time variable (T0, T1, T2, and T3) on dimensional stability. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Bonferroni adjustment where necessary. Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) were calculated to assess intra-operator and inter-operator reliability. Reliability was evaluated using repeated measurements by two investigators at two and three weeks after the initial measurements. Values greater than 0.90 were considered excellent, 0.75–0.90 as good, 0.50–0.75 as moderate, and below 0.50 as poor. A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was set for all statistical tests.

3. Results

All 75 manufactured test bodies were successfully included in the analysis, with no exclusions due to defects, incomplete curing, or measurement errors. The dataset detailing the mean value of measurements for all test bodies at different time points (T0, T1, T2, T3) was reported in

Table 2.

3.1. Effect of Printing and Post-Processing (T0).

After printing and post-processing, the AccuFab test bodies demonstrated the best dimensional stability, followed by those from Elegoo and Zortrax printers, with deviations of -0.051 mm, -0.157 mm, and -0.177 mm from the overall CAD reference of 12.25 mm, respectively. The higher accuracy of the AccuFab prints than the samples from the other two printers was also confirmed by the x-, y- axis, and thickness measurements. For virtual design 1, having the largest dimensions, deviations from individual CAD reference values (y-axis=24 mm, x-axis=18 mm) were -0.096 mm (y-axis), -0.020 mm (x-axis) for AccuFab test bodies, -0.209 mm (y-axis), -0.114 mm (x-axis) for Elegoo test bodies, and -0.175 mm (y-axis) and -0.122 mm (x-axis) for Zortrax test bodies. For virtual design 3, which had the smallest dimensions, deviations from individual CAD reference values (y-axis=10mm, x-axis=8 mm) were: for AccuFab specimens -0.071 mm (y-axis) and -0.036 mm (x-axis); for Elegoo specimens -0.056 mm (y-axis) and -0.021 mm (x-axis); for Zortrax specimens -0.062 mm (y-axis) and -0.022 mm (x-axis). For virtual design 4, the thickness evaluation further supported the AccuFab printer's superiority compared to Elegoo and Zortrax, with a deviation from individual CAD reference (2,5 mm) of -0.059 mm, -0.533 mm, and -0.482 mm, respectively.

3.2. Effect of Storage Time After Printing and Post-Processing (T1)

At 1-month storage after printing and post-processing, slight dimensional changes were observed in all test bodies. The deviations measured from the overall CAD reference of 12.25 mm were -0.028 mm for samples printed by AccuFab, -0.154 mm for those by Elegoo, and -0.067 mm for those by Zortrax. Compared to individual reference values of the larger sample (y-axis=24 mm, x-axis=18 mm), AccuFab prints showed minimal deviations (y-axis=+0.011 mm, x-axis=+0.007 mm) than prints by Elegoo (y-axis= -0.039 mm, x-axis=-0.109 mm) and Zortrax (y-axis=-0.119 mm, x-axis=-0.135 mm). Additionally, measurements of the smallest size sample (y-axis=10mm, x-axis=8 mm) confirmed that test bodies printed with AccuFab displayed greater resilience to dimensional changes over the storage period with deviations of -0.087 mm on the y-axis and -0.063 mm on the x-axis compared to those printed by Eligoo (y-axis= 0.074 mm, x-axis=0.079 mm) and by Zortrax (y-axis=-0.082 mm, x-axis=-0.091). The thickness evaluation of sample 4 confirmed better dimensional stability for AccuFab specimens than those from Elegoo and Zortrax, with deviations from individual CAD references of -0.035 mm, -0.131 mm, and -0.115 mm, respectively.

3.3. Effect of Steam Sterilization (T2)

The impact of steam sterilization on dimensional changes showed significant variations from the overall CAD reference value (12.25 mm) in all test bodies, with a slight expansion trend. The AccuFab prints reported a minor deviation (+0.093 mm) compared to samples manufactured by Elegoo (+0.047 mm) and Zortrax (+0.116 mm) printers. Analysis of individual measures revealed that steam sterilization led to more pronounced dimensional changes in smaller test bodies, particularly for Zortrax and Elegoo. For virtual design 3 (y-axis=10mm, x-axis=8 mm), the least deviations were observed for AccuFab (y-axis= +0.098 mm, x-axis=+0.151 mm), followed by Elegoo (y-axis=+0.089 mm, x-axis=+0.126 mm), and Zortrax (y-axis=+0.113 mm, x-axis= +0.134 mm). In sample 4 (CAD reference = 2.5 mm), test bodies printed by AccuFab, Elegoo, and Zortrax exhibited thickness deviations of 0.052 mm, +0.105 mm, and +0.083 mm, respectively.

In the design 4 specimens (2,5 mm), no thickness changes were observed in the test bodies printed by the AccuFab device. Meanwhile, the samples from Elegoo and Zortrax showed deviations of -0.067mm and -0.083, respectively.

3.4. Effect of Storage Time After Steam Sterilization (T3)

After an additional month of storage following sterilization, compared to the overall CAD reference value (12.25mm), no dimensional changes in the AccuFab specimens and minimal dimensional recovery of the samples from Elegoo (-0.067mm) and Zortrax (-0.083 mm) were detected. Individual measurements of the largest test bodies (virtual design 1) displayed slight deviations for those printed by AccuFab (y-axis = -0.033 mm, x-axis = -0.009 mm), Elegoo (y-axis = -0.055 mm, x-axis = -0.012 mm), and Zortrax (y-axis = -0.112 mm, x-axis = -0.017 mm), suggesting a compounded effect of storage and sterilization.

Dimensional stability with minimal cumulative effects over time was validated by assessment of the smaller size test bodies (virtual design 3) and thickness (virtual design 4). For smaller-dimensional specimens, deviations from the individual CAD reference (y-axis = 10 mm, x-axis = 8 mm) were y-axis = -0.041 mm, x-axis = -0.013 mm for those printed by AccuFab; y-axis = -0.089 mm, x-axis = -0.131 mm for Elegoo samples; and y-axis = -0.091 mm, x-axis = -0.087 mm for Zortrax samples. For thickness, deviations were +0.013 mm for AccuFab prints, +0.057 mm for Elegoo prints, and +0.040 mm for Zortrax prints.

According to these results, prolonged storage post-sterilization seemed to have a negligible impact on the dimensional stability of all test specimens, with those printed by AccuFab showing better performance.

3.5. Effect of Printer Type and Time (T0, T1, T2, and T3) Variable

The combined analysis of printer type (p-value = 0.034) and time variable (p-value = 0.020) significantly influenced the dimensional changes of all test bodies. Samples printed by the AccuFab device achieved better accuracy than those produced by Elegoo and Zortrax across all four time points, with the highest value at TO.

The effect of the time variable was particularly notable at T2 and less significant at T1 and T3, suggesting that storage alone (before or after sterilization) had a negligible impact on dimensional stability compared to heat and moisture during sterilization. The interaction between printer type and time variable was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.765), indicating that the differences between test bodies from the different printers were consistent at all four time points.

4. Discussion

The null hypothesis was rejected based on the statistical analysis of the results, which confirmed that the dimensional stability of the test bodies manufactured with the SGO1 polymer resin was affected by different LCD-3D printers, steam sterilization and storage times.

All test bodies showed deviations from the overall CAD reference value of 12.25 mm after printing and post-processing (T0) and following steam sterilization (T2). A similar trend was observed for the effect of storage times at T1 and T3. The AccuFab prints demonstrated better dimensional stability than the Elegoo and Zortrax samples.

To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the only study that evaluated the dimensional stability of SG01 resin used for printing surgical guides with LCD-3D technology. Therefore, comparing current findings with previous in-vitro reports on the accuracy of 3D-printed surgical guides has been challenging due to differences in study designs, 3D printers, printing materials, printing and post-processing parameters, and evaluation methodologies.

Several studies have explored how different additive manufacturing technologies, 3D printers, and resin materials influence the accuracy of surgical guides, reporting slightly contrasting results [

6,

7,

14,

15].

In in-vitro research, Chen et al. evaluated the dimensional changes of CAD-CAM surgical guides produced using three different materials and additive manufacturing technologies immediately after production and after a one-month storage period. They showed that combinations of various materials and 3D printers influenced surgical templates' accuracy, reproducibility, and stability. However, the absolute values of all dimensional differences, even if statistically significant, were small and may not cause any clinically notable effects [

16]

A clinically acceptable accuracy between the definitive and planned implant position was also shown in the in-vitro study conducted by Herschdorfer et al. for assessing the effect of various additive manufacturing technologies on the fabrication of surgical templates [

17].

Wegmüller et al. reached similar conclusions when they compared consumer-level desktop 3D printers and high-end professional 3D models. They found statistically significant differences in producing drill guides but negligible deviations from a clinical point of view. In the authors' opinion, desktop 3D printers can produce drill guides with an accuracy comparable to that of professional models and at reduced costs [

18].

Recently, Bathija et al., in an in-vitro study, compared the accuracy of CAD-CAM surgical templates fabricated from five different additive manufacturing technologies by evaluating the final implant position against the initial digital implant planning. Despite significant implant deviations between different printing technologies, the results for all groups were still clinically acceptable because they were within the 2 mm safety margins of the mesial, distal, buccal, lingual, and apicocoronal limits.

In addition to manufacturing processes, the time since production may influence the dimensional stability of 3D surgical guides [

19].

In an in vitro study, Lo Russo et al. analyzed the dimensional stability at 0, 5, 10, and 20 days of templates manufactured by DLP processing technology, stored at room temperature, sealed in plastic bags, and enclosed in dark containers. The time post-manufacturing, alone or nested with guide volume, impacted the dimensional variability of these devices, although the variations were limited [

20].

Another critical aspect that might lead to inaccuracies in implant insertion is the impact of steam sterilization on guide dimensional changes and material biomechanical properties. Numerous studies have explored the effects of autoclaving at different cycles on samples manufactured using different printing technologies and resin materials, reporting conflicting results.

Labakoum et al. recently assessed the effects of steam sterilization at 121°C, + 1 bar for 20 minutes and at 134°C, + 2 bar for 10 minutes on dimensional and mechanical characteristics of 3D surgical guides made with a procedure similar to that adopted in the present study [

21]. The samples were printed using LCD technology (Mars 2 PRO printer -Elegoo, Shenzhen, China) and SG100 resin, immersed in 99% isopropanol alcohol for 5 min, air-dried, and then subjected to photopolymerization at a wavelength of 405 nm and temperature of 25 °C for 10 min. The results indicated that the mechanical and geometric characteristics were influenced by steam sterilization. After being autoclaved at 121 °C, the samples showed decreased tensile load and deformation during bending. However, when autoclaved at 134 °C, the maximum compressive load and compressive strength increased significantly, standard tensile tests revealed only slight deformation and findings from flexion evaluations remained unchanged.

Autoclaving-induced dimensional changes were also found by Hüfner et al. investigating 3D surgical guides made from different resin/printer combinations. All samples, except for the E-Guide/Micro Plus XL combination, experienced minor shrinkage, which varied in all dimensions [

22]. Furthermore, changes differed significantly among the materials following autoclaving with the cycle at 121°C, whereas no significant difference was shown between the groups when the cycle at 134°C was employed.

In a similar study on 3D-printed surgical templates from five different materials, Yazigi et al. evaluated the accuracy after sterilization in an autoclave at 121° C and a pressure of 2 bar for 20 minutes [

23]. Significant dimensional changes in increased vertical discrepancy and angulation levels were detected for all materials. However, these changes were still acceptable when an additional load was applied during the repositioning of the guides onto test models. Moreover, the choice of material significantly impacted the measured vertical discrepancies but did not affect the angulation measurements.

Mean and labial deformations and changes in the axial position of implants were reported by Li et al. in surgical guides printed using DLP technology, autoclaved at 134°C for 5 minutes and dried for 15 minutes [

24]. Based on their findings, the authors concluded that this sterilization method was unsuitable for the clinical treatment of surgical guides.

Effects of disinfection and autoclave sterilization on the mechanical properties of surgical guides made using SLA and DLP printing were tested by POP et al. [

25]. Regarding the DLP-printing method, templates autoclave-sterilized at 121°C, +1 bar, for 20 min showed statistically significant increases in the flexural strength and flexural modulus values. Compared to those autoclave-sterilized at 134°C, +2 bar for 10 min, these specimens demonstrated a significant increase in flexural strength and flexural strain and a decrease in flexural modulus. Conversely, the tensile strength, tensile modulus, and tensile strain values were decreased in templates sterilized at 134°C rather than those autoclaved at 121°C. It was not only the temperature value that influenced the mechanical behaviour but also the exposure time of the materials at that temperature because a more extended time increases the material stiffness. In the authors' opinion, the increased rigidity of the material could have implications in the clinical setting, making the guides more likely to fracture when pressure against the dental arches during surgery subjects them to combined loading (compression accompanied by bending).

Kirschner et al. studied how steam sterilization influenced the Vickers hardness and flexural modulus of insertion guides 3D printed with five different methods and resin materials [

26]. The results indicated that the autoclaving cycles led to more pronounced changes in Vickers hardness and a minor impact on the flexural modulus (lower for all specimens). The variations observed depended on the specific resin and printer combination. The authors concluded that steam sterilization could alter the mechanical properties of the templates to some extent, especially with the cycle at 134°C.

Unlike the results mentioned above, some studies found no significant effects of steam sterilization on the accuracy of 3D-printed surgical guides.

In a pilot study by Marie et al., the impact of steam heat sterilization at 121°C for 20 minutes on the dimensional stability of surgical guides 3D-printed both in-office and in the laboratory using Class I biocompatible resin material was examined [

27]. The findings showed no significant impact on the dimensional changes of the tested parts and no statistical differences between the in-office and laboratory 3D-printed samples.

Similar conclusions were reached by Sharma et al., who deemed not clinically relevant the overall linear expansion observed in test bodies manufactured in-house using PolyJet Glossy and SLA-LT printers and five different Class IIa biocompatible resins (proprietary and third-party) [

13]. Additionally, even though statistically significant differences were noted among the two resin groups, the dimensional accuracy of test bodies fabricated with third-party resins was within a comparable range to proprietary materials. This finding would support the use of support third-party resins as a cost-effective alternative for in-house 3D printing setups.

Likewise, Török et al.did not show any measurable deformation or structural change in 3D surgical guides printed PolyJet technology after sterilization both at 121°C for 20 min under a pressure of 1 bar and at 134°C for 10 min under a pressure of 2 bar [

28]. The only exception was the significant difference in the hardness strength of the autoclave sterilized specimens at 134°C. According to these results, the authors considered low- and high-temperature sterilization an appropriate method for sterilizing 3D-printed dental implant drill guide templates.

The present study presents some limitations. The first was the difference between test bodies and surgical guides in geometric morphology, which is flat in the former and convex or concave, related to the shape of the jaws in the latter. Additionally, the absence of metal sleeves could impact dimensional changes, as adding sleeves causes extra tension. However, recent studies have shown no significant differences between 3D-printed surgical guides with and without metal sleeves [

29,

30].

Furthermore, the resin biomechanical properties, such as flexural strength and hardness, were not analyzed. Variations in these parameters potentially lead to fracturing and bending during surgical guide application, ultimately resulting in inaccuracies in implant insertion [

25,

26]. Another limitation is that the study only focused on one steam sterilization protocol and did not consider other chemical disinfection techniques or sterilization methods such as dry heat, ethylene oxide (ETO) gas, and hydrogen peroxide gas plasma. However, it's important to note that the chosen protocol is widely used in dental practices due to its simplicity and effectiveness.