Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Geometric Signatures of Topological Changes

2.2. Numerical Methods

3. Results

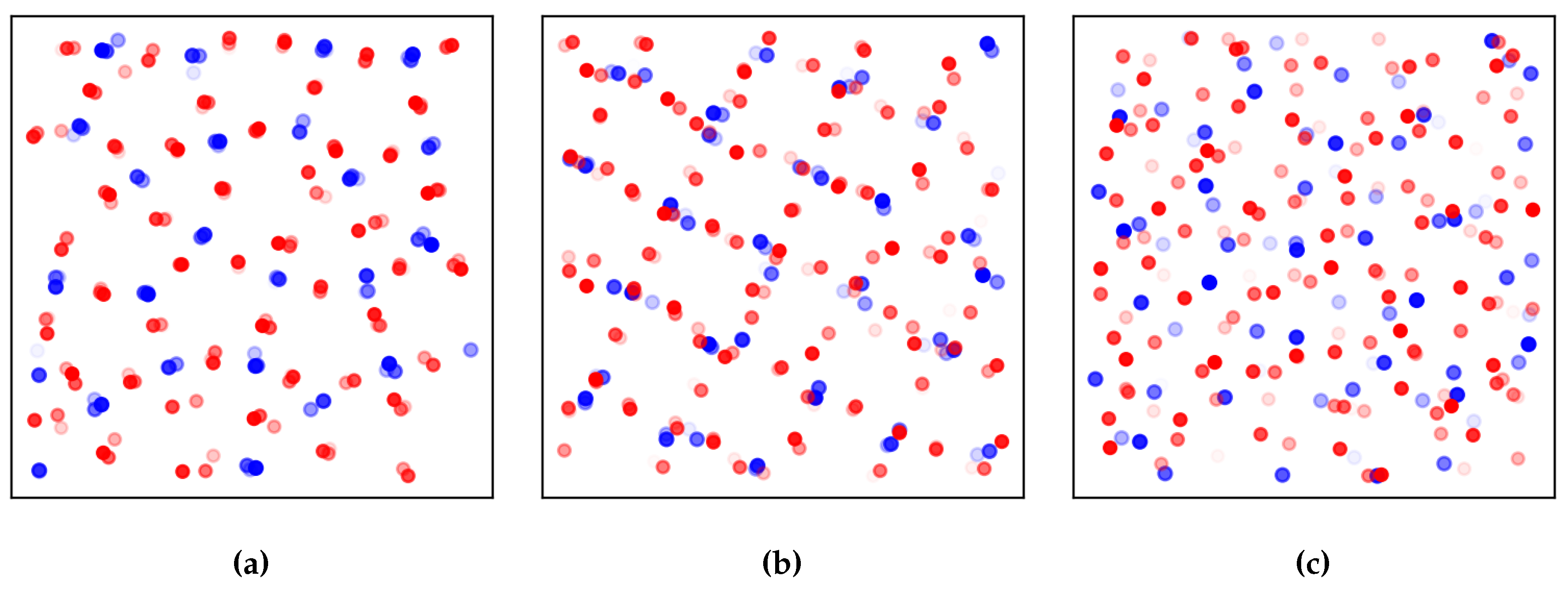

3.1. Model

3.2. Characterization of the Phase Transition

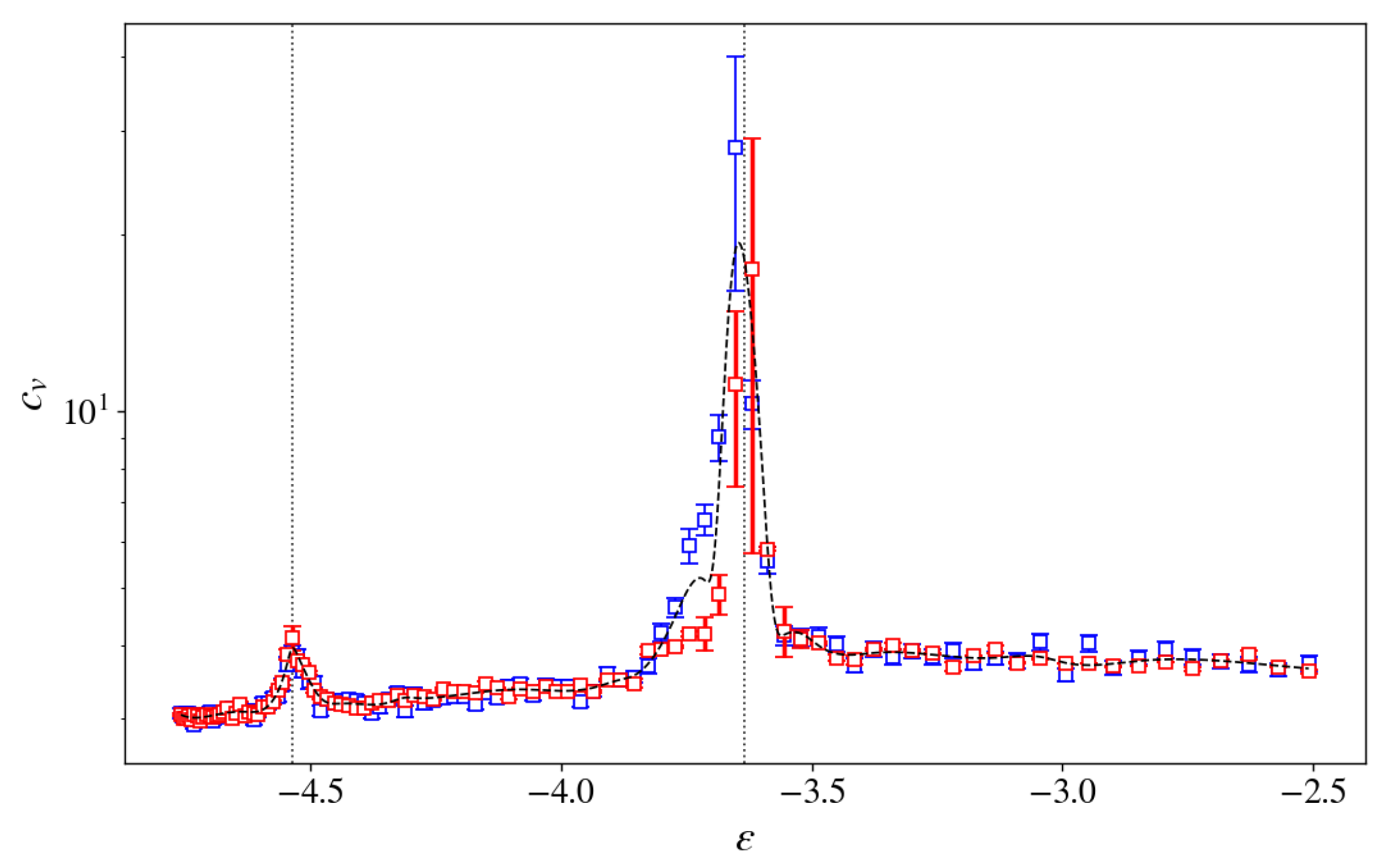

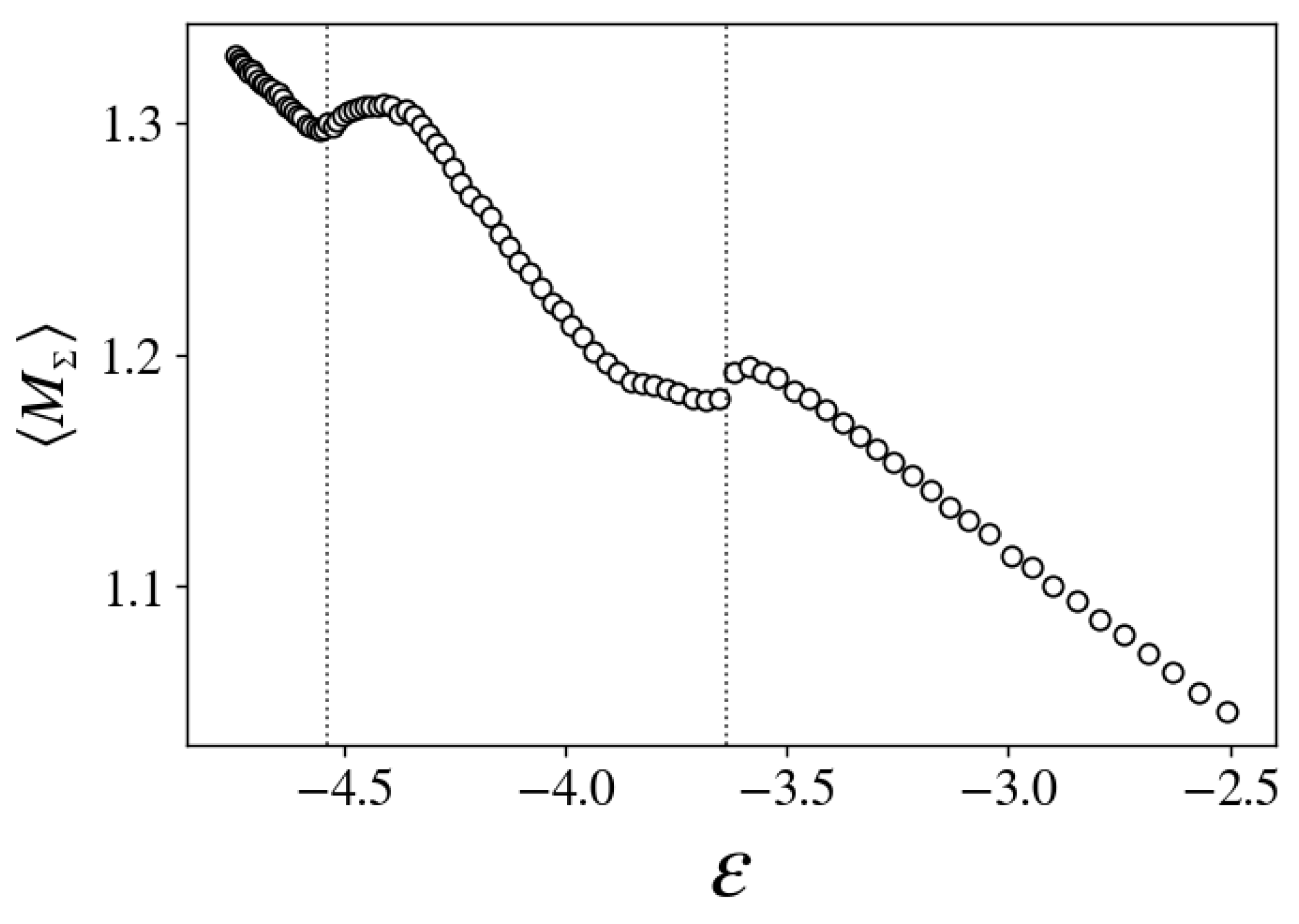

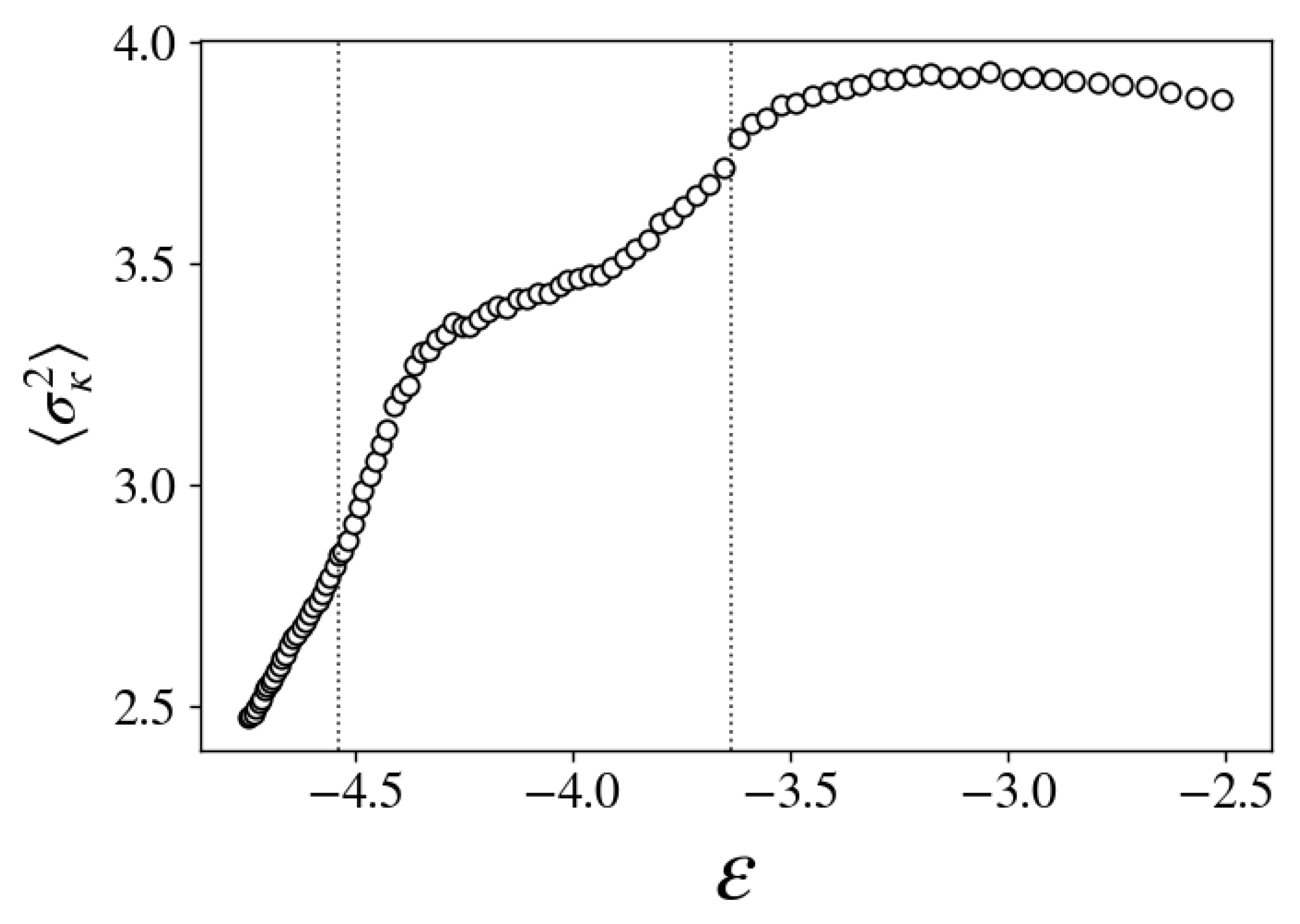

3.2.1. Specific Heat, Caloric Curve and Entropy Derivatives

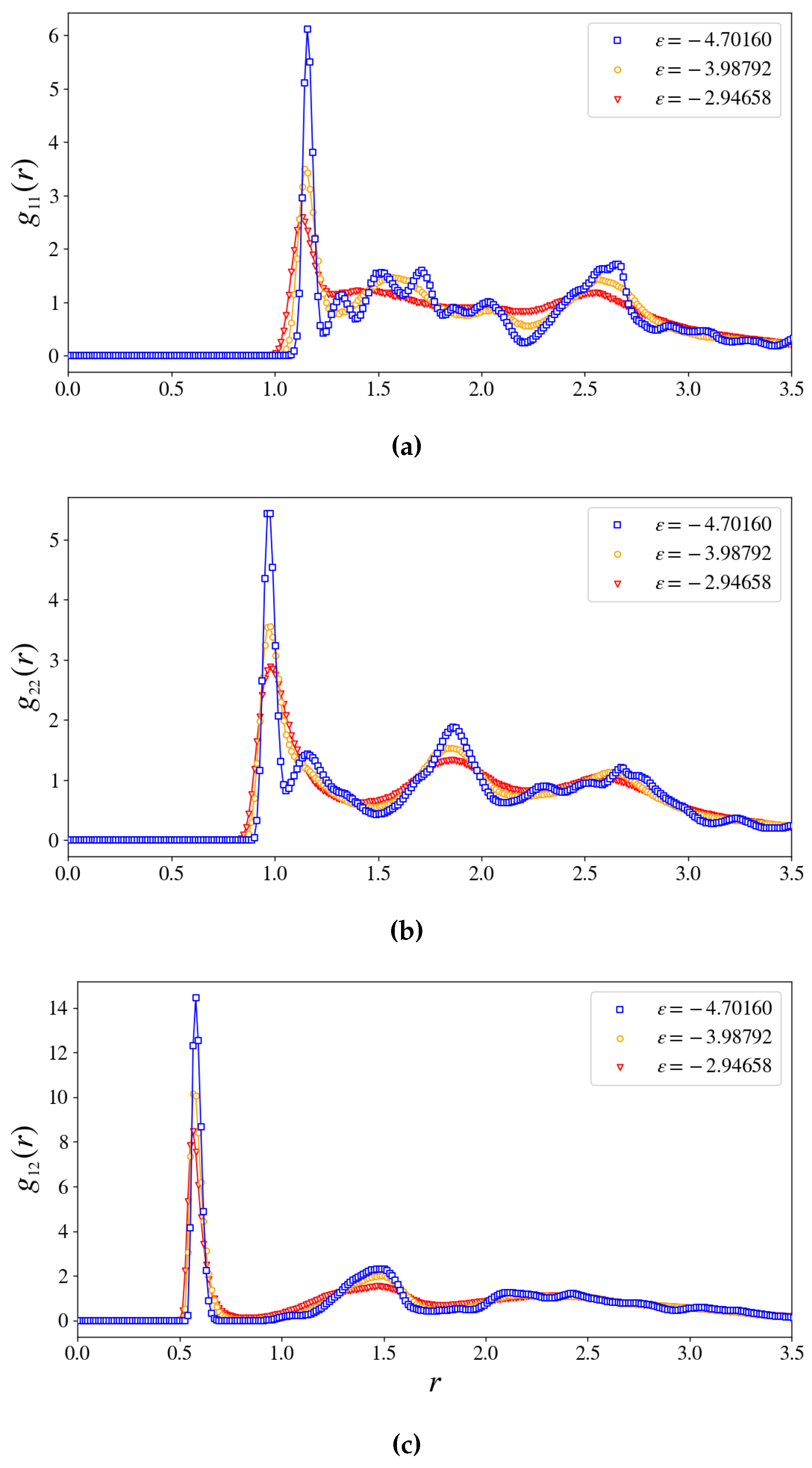

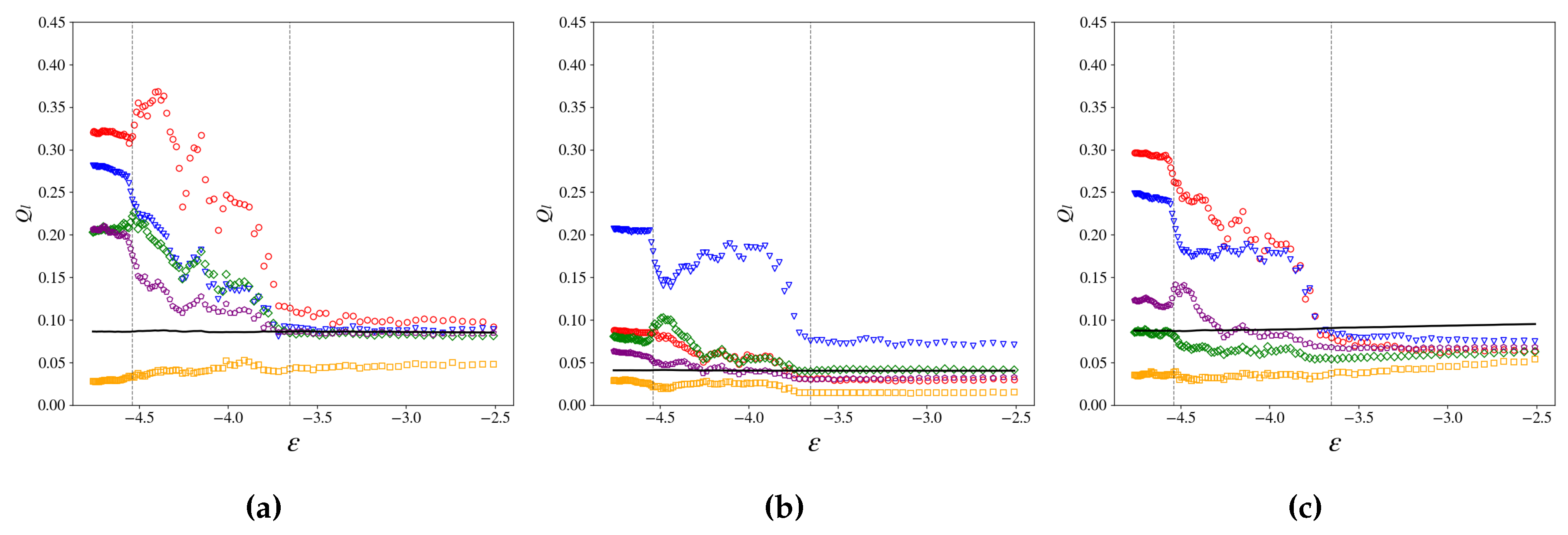

3.2.2. Translational and Orientational Order

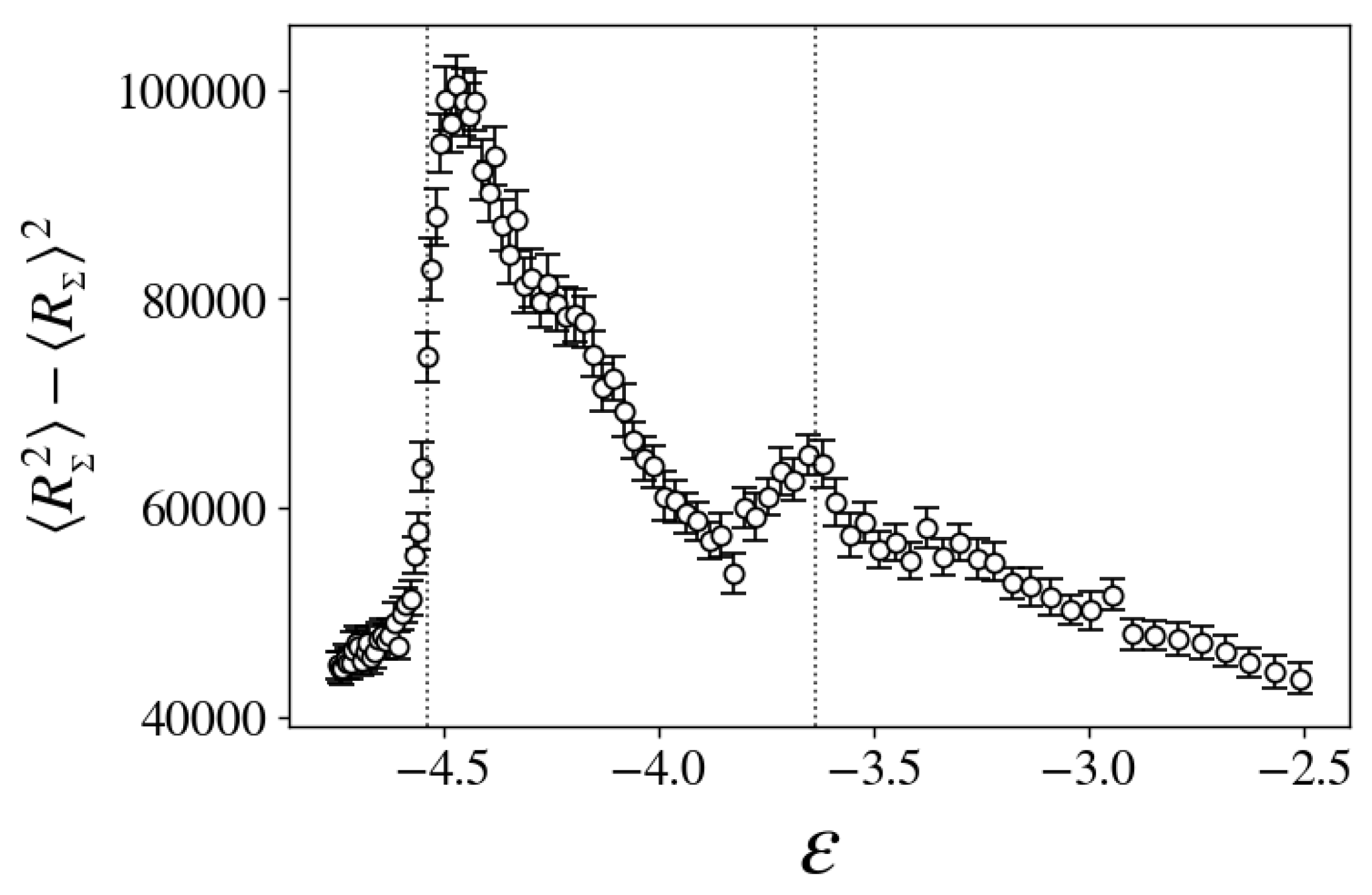

3.3. Topological Changes

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Monte Carlo Methods

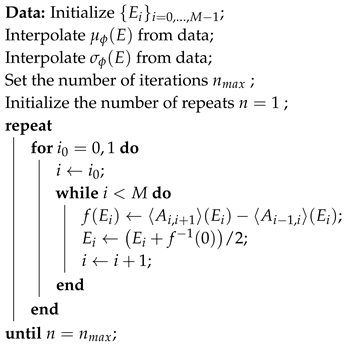

| Algorithm: E-range optimization through U-overlap method |

|

Appendix B. Initial Configuration, Periodic Boundary Conditions and Cutoff

References

- Pettini, M. Geometry and Topology in Hamiltonian Dynamics and Statistical Mechanics; Vol. 33, Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics, Springer New York: New York, NY, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angell, C. Perspective on the Glass Transition. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 1988, 49, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, G. The Physics of the Glass Transition. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2000, 280, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelani, L.; Di Leonardo, R.; Ruocco, G.; Scala, A.; Sciortino, F. Saddles in the Energy Landscape Probed by Supercooled Liquids. Physical Review Letters 2000, 85, 5356–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broderix, K.; Bhattacharya, K.K.; Cavagna, A.; Zippelius, A.; Giardina, I. Energy Landscape of a Lennard-Jones Liquid: Statistics of Stationary Points. Physical Review Letters 2000, 85, 5360–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, M. The Calculus of Variations in the Large, repr ed.; Number 18 in Colloquium Publications / American Mathematical Society, American Mathematical Society: Providence, R.I, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gori, M.; Franzosi, R.; Pettini, M. Topological Origin of Phase Transitions in the Absence of Critical Points of the Energy Landscape. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2018, 2018, 093204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cairano, L.; Gori, M.; Pettini, M. Topology and Phase Transitions: A First Analytical Step towards the Definition of Sufficient Conditions. Entropy 2021, 23, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cairano, L.; Gori, M.; Pettini, G.; Pettini, M. Hamiltonian Chaos and Differential Geometry of Configuration Space–Time. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 2021, 422, 132909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leocmach, M.; Tanaka, H. Roles of Icosahedral and Crystal-like Order in the Hard Spheres Glass Transition. Nature Communications 2012, 3, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H. Bond Orientational Order in Liquids: Towards a Unified Description of Water-like Anomalies, Liquid-Liquid Transition, Glass Transition, and Crystallization: Bond Orientational Order in Liquids. The European Physical Journal E 2012, 35, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel-Hadj-Aissa, G.; Gori, M.; Penna, V.; Pettini, G.; Franzosi, R. Geometrical Aspects in the Analysis of Microcanonical Phase-Transitions. Entropy 2020, 22, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, E.M.; Halicioglu, T.; Tiller, W.A. Laplace-Transform Technique for Deriving Thermodynamic Equations from the Classical Microcanonical Ensemble. Physical Review A 1985, 32, 3030–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cairano, L.; Capelli, R.; Bel-Hadj-Aissa, G.; Pettini, M. Topological Origin of the Protein Folding Transition. Physical Review E 2022, 106, 054134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel-Hadj-Aissa, G.; Gori, M.; Franzosi, R.; Pettini, M. Geometrical and Topological Study of the Kosterlitz–Thouless Phase Transition in the XY Model in Two Dimensions. Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 2021, 2021, 023206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coslovich, D.; Pastore, G. Dynamics and Energy Landscape in a Tetrahedral Network Glass-Former: Direct Comparison with Models of Fragile Liquids. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2009, 21, 285107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigera, T.S.; Parisi, G. Fast Monte Carlo Algorithm for Supercooled Soft Spheres. Physical Review E 2001, 63, 045102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettini, G.; Gori, M.; Franzosi, R.; Clementi, C.; Pettini, M. On the Origin of Phase Transitions in the Absence of Symmetry-Breaking. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2019, 516, 376–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, S.; Seaton, D.T.; Landau, D.P.; Bachmann, M. Microcanonical Entropy Inflection Points: Key to Systematic Understanding of Transitions in Finite Systems. Physical Review E 2011, 84, 011127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, K.; Bachmann, M. Classification of Phase Transitions by Microcanonical Inflection-Point Analysis. Physical Review Letters 2018, 120, 180601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M. Novel Concepts for the Systematic Statistical Analysis of Phase Transitions in Finite Systems. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2014, 487, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, P.J.; Nelson, D.R.; Ronchetti, M. Bond-Orientational Order in Liquids and Glasses. Physical Review B 1983, 28, 784–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errington, J.R.; Debenedetti, P.G.; Torquato, S. Quantification of Order in the Lennard-Jones System. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2003, 118, 2256–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, L.C.; Affouard, F.; Descamps, M.; Habasaki, J. Mixing Effects in Glass-Forming Lennard-Jones Mixtures. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2009, 130, 154505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truskett, T.M.; Torquato, S.; Debenedetti, P.G. Towards a Quantification of Disorder in Materials: Distinguishing Equilibrium and Glassy Sphere Packings. Physical Review E 2000, 62, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J.; Barkema, G.T. Monte Carlo Methods in Statistical Physics; Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press: Oxford : New York, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, J.R. Microcanonical Ensemble Monte Carlo Method. Physical Review A 1991, 44, 4061–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lustig, R. Microcanonical Monte Carlo Simulation of Thermodynamic Properties. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1998, 109, 8816–8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hukushima, K. Domain-Wall Free Energy of Spin-Glass Models: Numerical Method and Boundary Conditions. Physical Review E 1999, 60, 3606–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozada, I.; Aramon, M.; Machta, J.; Katzgraber, H.G. Effects of Setting the Temperatures in the Parallel Tempering Monte Carlo Algorithm. Physical Review E 2019, arXiv:cond-mat, physics:physics/1907.03906]100, 043311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holian, B.L.; Evans, D.J. Shear Viscosities Away from the Melting Line: A Comparison of Equilibrium and Nonequilibrium Molecular Dynamics. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1983, 78, 5147–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).