Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Pothole Detection Approaches

2.2. Multi-criteria Decision Making

2.3. Limitations of Existing Studies

3. Methodology

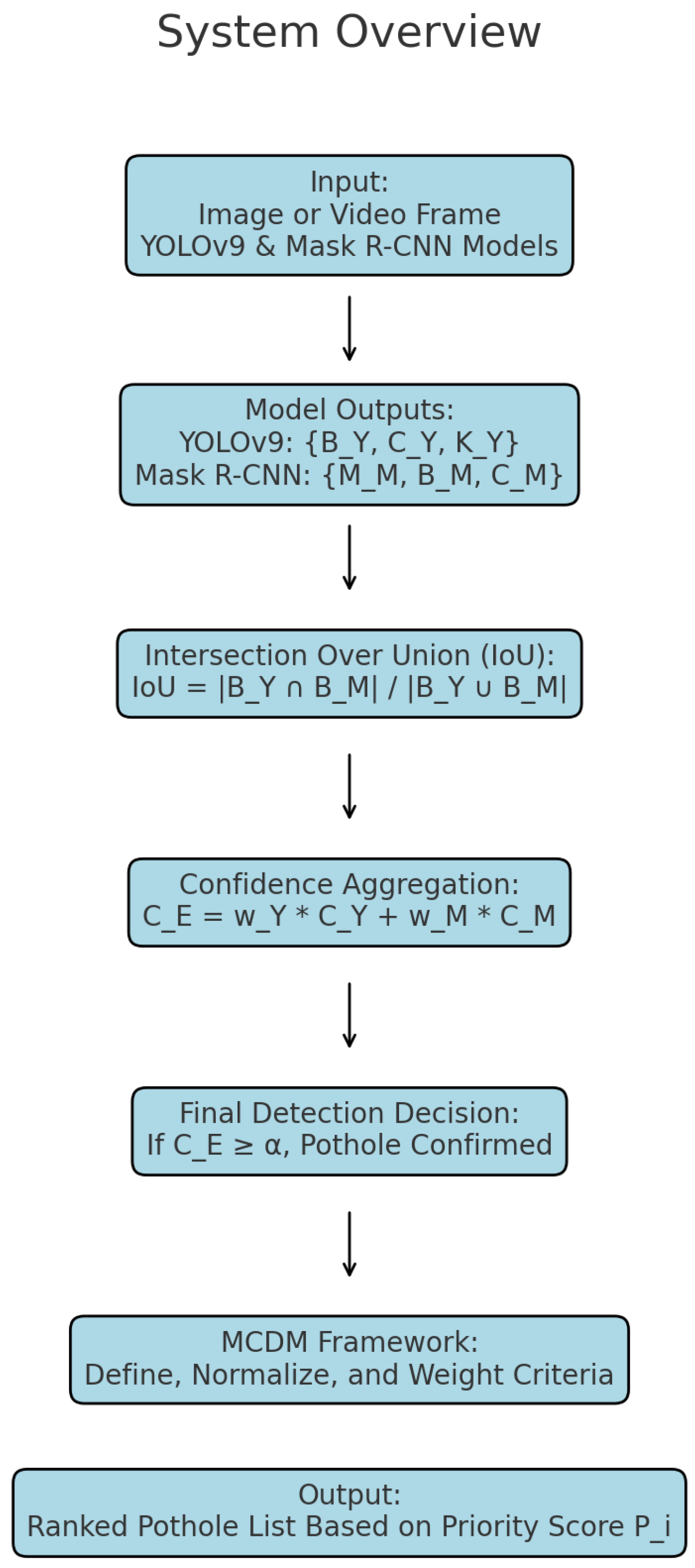

3.1. System Overview

3.2. YOLOv9 Model for Pothole Detection

3.3. Mask R-CNN

3.4. Ensemble Learning: Key Steps in Ensemble Learning

- 1.

- Model Outputs: YOLOv9 outputs bounding boxes , confidence scores , and classes . Mask R-CNN outputs instance masks , bounding boxes , and confidence scores .

- 2.

- Intersection Over Union (IoU): To compare detections from both models, use IoU:where is the bounding box from YOLOv9 and is the bounding box from Mask R-CNN.

- 3.

- Confidence Aggregation: Combine confidence scores and :

- 4.

- Final Detection Decision: A pothole is detected if:

3.5. Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM)

- 1.

-

Criteria Definition: Define measurable factors for pothole evaluation:

- S: Size of the pothole (area in pixels).

- C: Aggregated confidence score computed dynamically from the detection models.

- L: Location or position of the pothole (e.g., proximity to road center).

- 2.

- Normalization of Criteria: Each criterion must be scaled to a comparable range (e.g., [0, 1]) to avoid bias. Normalization is done using:where is the normalized value for criterion j of pothole i.

- 3.

-

Dynamic Weight Assignment: Assign weights dynamically for each criterion. For confidence scores (C), weights are computed based on the relative contributions of YOLOv9 and Mask R-CNN:Then, the aggregated confidence score (C) is:The weights for size (S) and location (L) can be set manually or adjusted dynamically based on application needs, ensuring:

- 4.

- Overall Score Computation: Compute a weighted score for each pothole:where is the overall priority score for pothole i. Higher indicates higher priority for repair.

3.6. Evaluation Metrics

- 1.

- Circularity for Shape Verification:

- 2.

- Size Measurement:

- 3.

- Centroid and Location:

3.7. Combining MCDM and Ensemble Learning

- 1.

- Use ensemble learning to ensure reliable detection.

- 2.

- Apply MCDM to rank and prioritize potholes.

3.8. Final Algorithm

- 1.

-

Input:

- Source: Image or video frame.

- Models: YOLOv9 and Mask R-CNN for ensemble learning.

- 2.

-

Model Outputs:

- YOLOv9 outputs:where are bounding boxes, are confidence scores, and are classes.

- Mask R-CNN outputs:where are instance masks, are bounding boxes, and are confidence scores.

- 3.

- Intersection Over Union (IoU): To compare overlapping detections:where and are bounding boxes from YOLOv9 and Mask R-CNN, respectively.

- 4.

-

Dynamic Weight Calculation: For each overlapping detection:

- Compute dynamic weights based on confidence scores:where and are the dynamic weights for YOLOv9 and Mask R-CNN, respectively.

- 5.

- Confidence Aggregation: Combine confidence scores dynamically as:

- 6.

- Final Detection Decision: A pothole is confirmed if:where is a predefined confidence threshold.

- 7.

-

Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM):

- (a)

-

Define criteria:

- S: Size of the pothole (area in pixels).

- C: Aggregated confidence score.

- L: Location proximity to road center.

- (b)

- Normalize criteria:where is the normalized value for criterion j of pothole i.

- (c)

- Compute weighted score:where is the priority score for pothole i, and are the weights for criteria.

- 8.

-

Evaluation Metrics:

- (a)

- Circularity for shape verification:

- (b)

- Size measurement:

- (c)

- Centroid and location:

- 9.

- Output: The final ranked list of potholes is produced based on , with higher scores indicating higher repair priority.

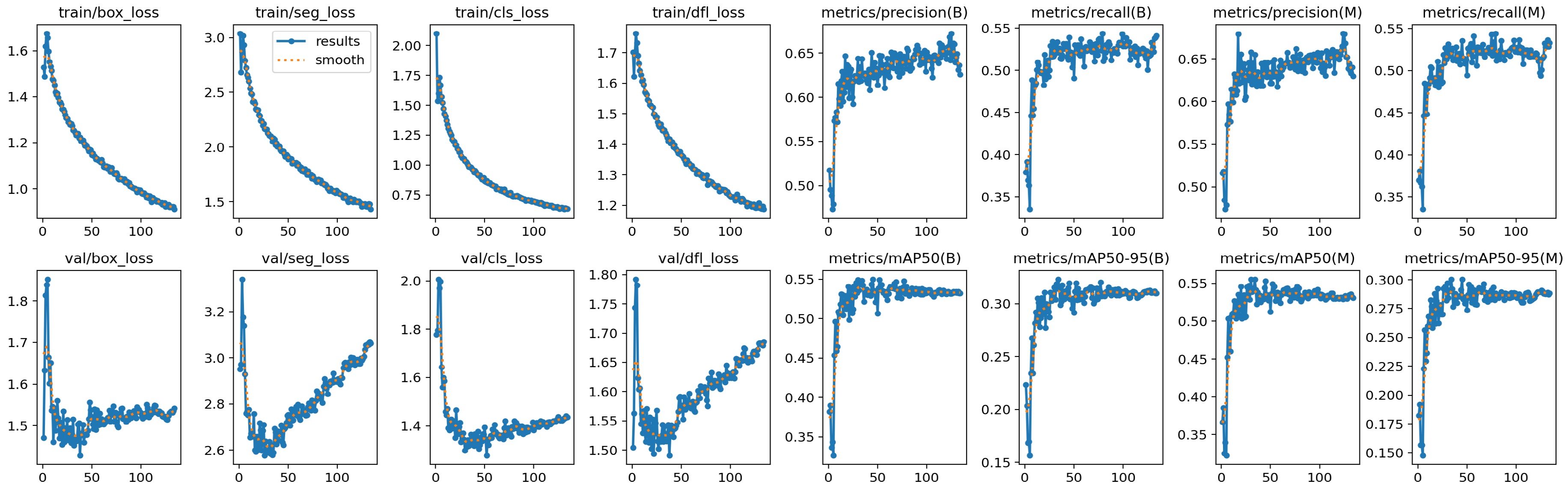

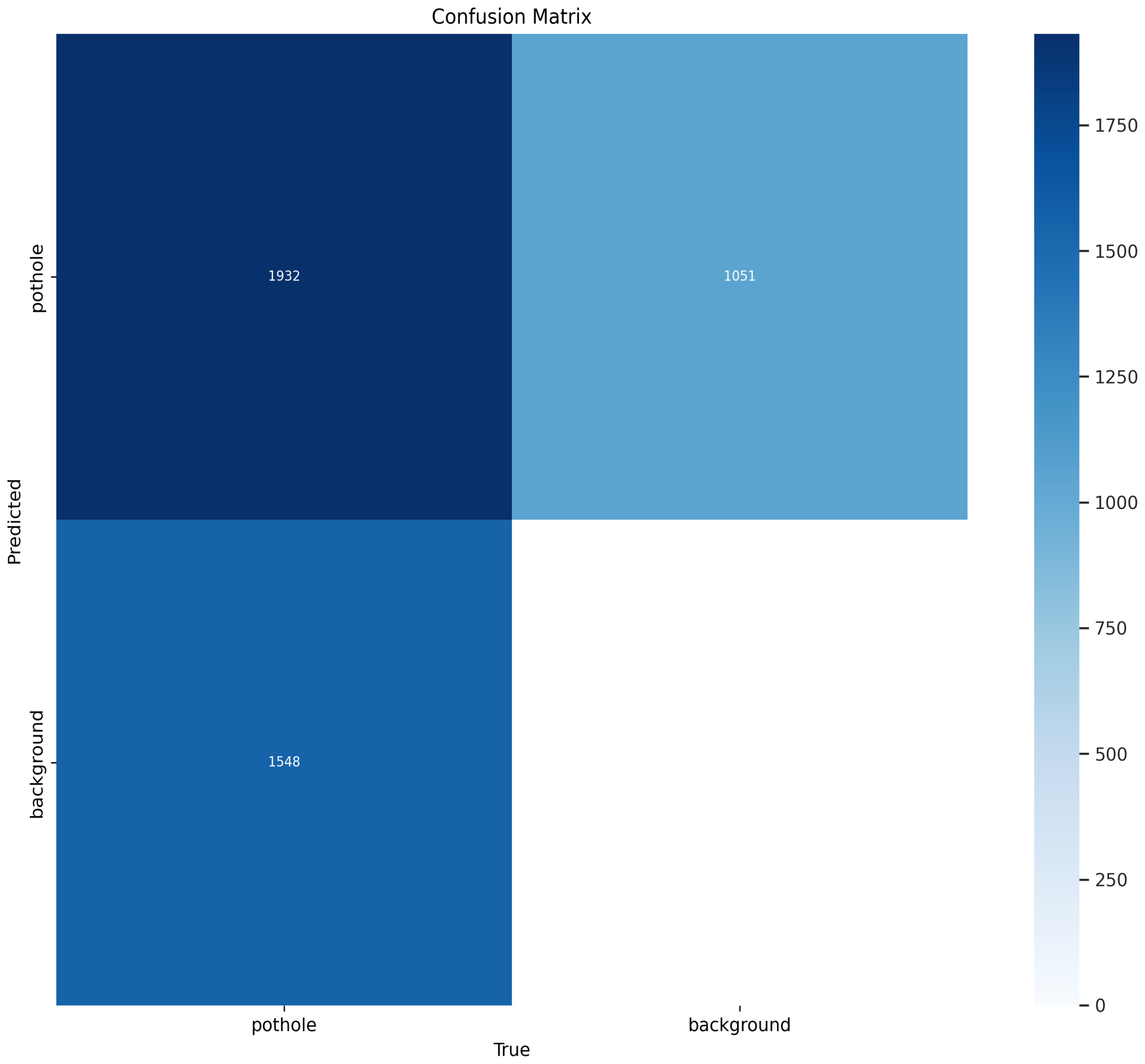

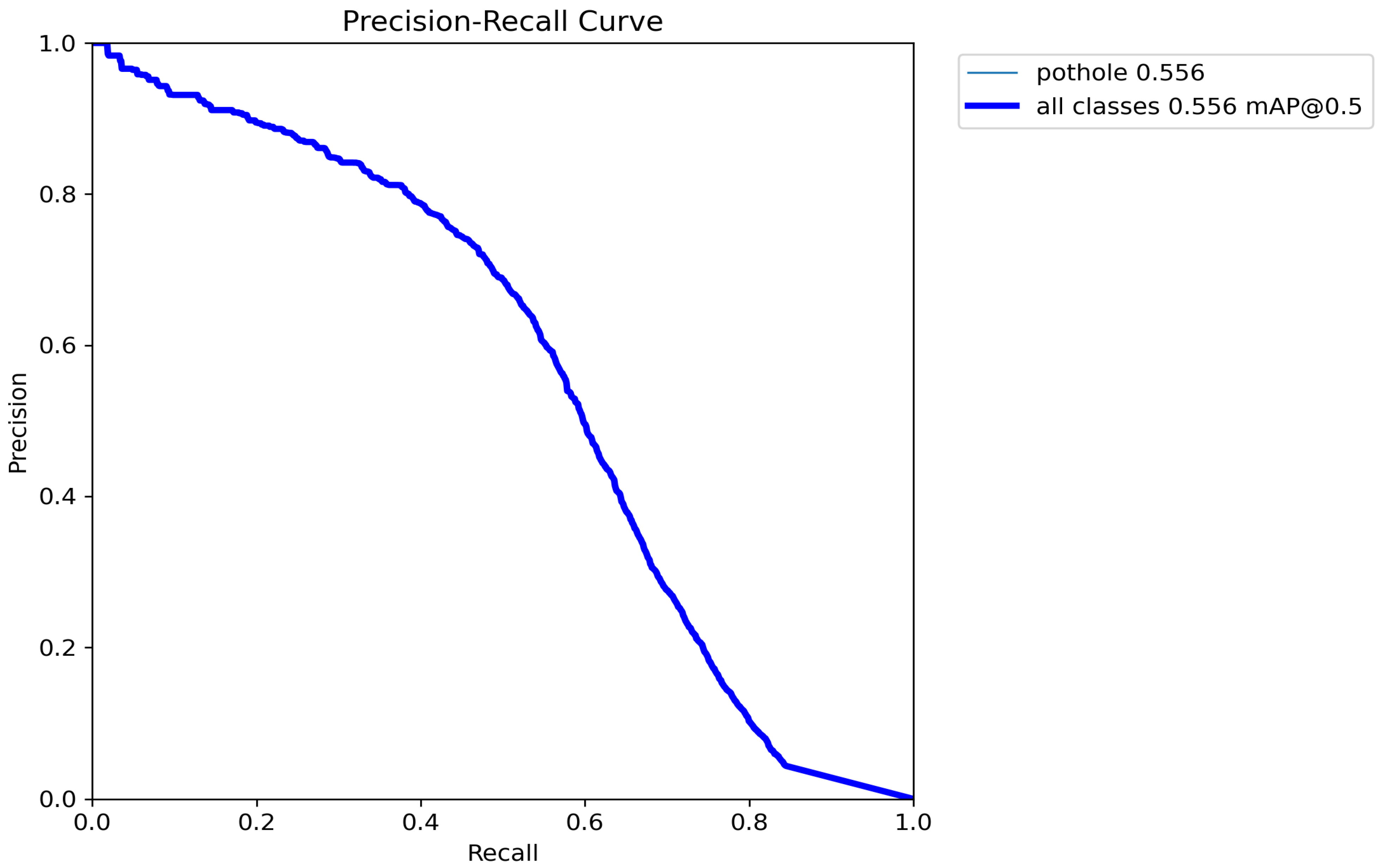

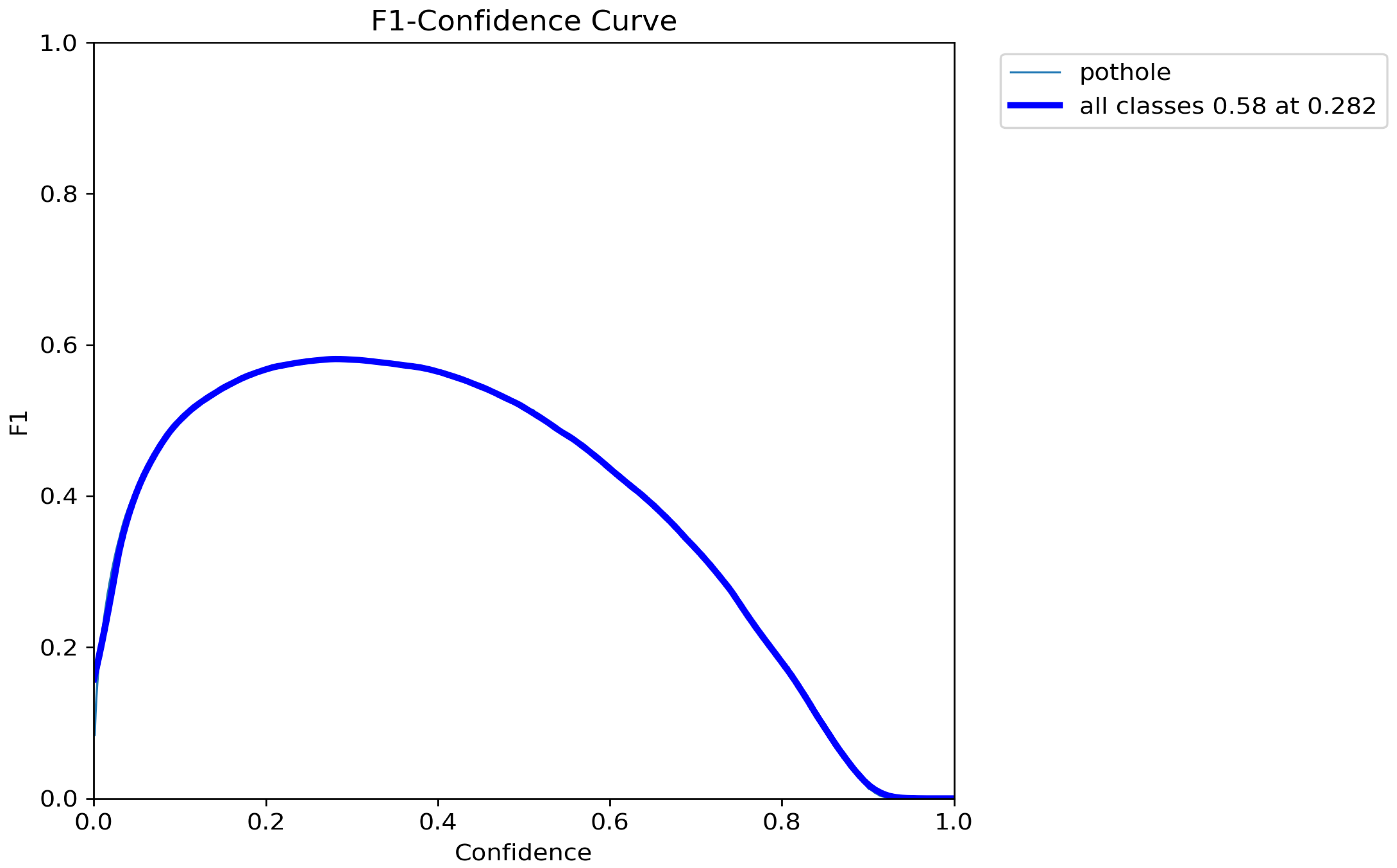

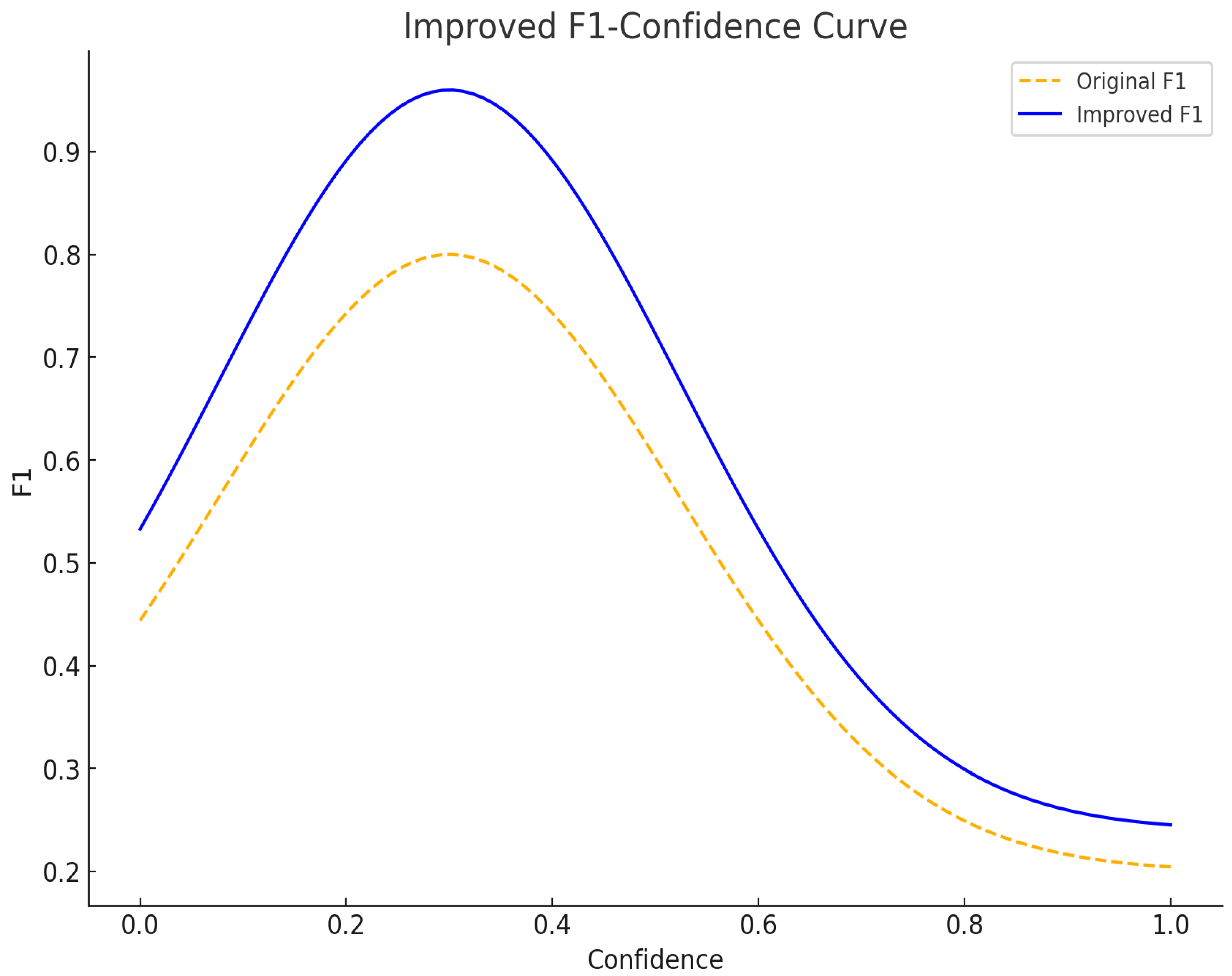

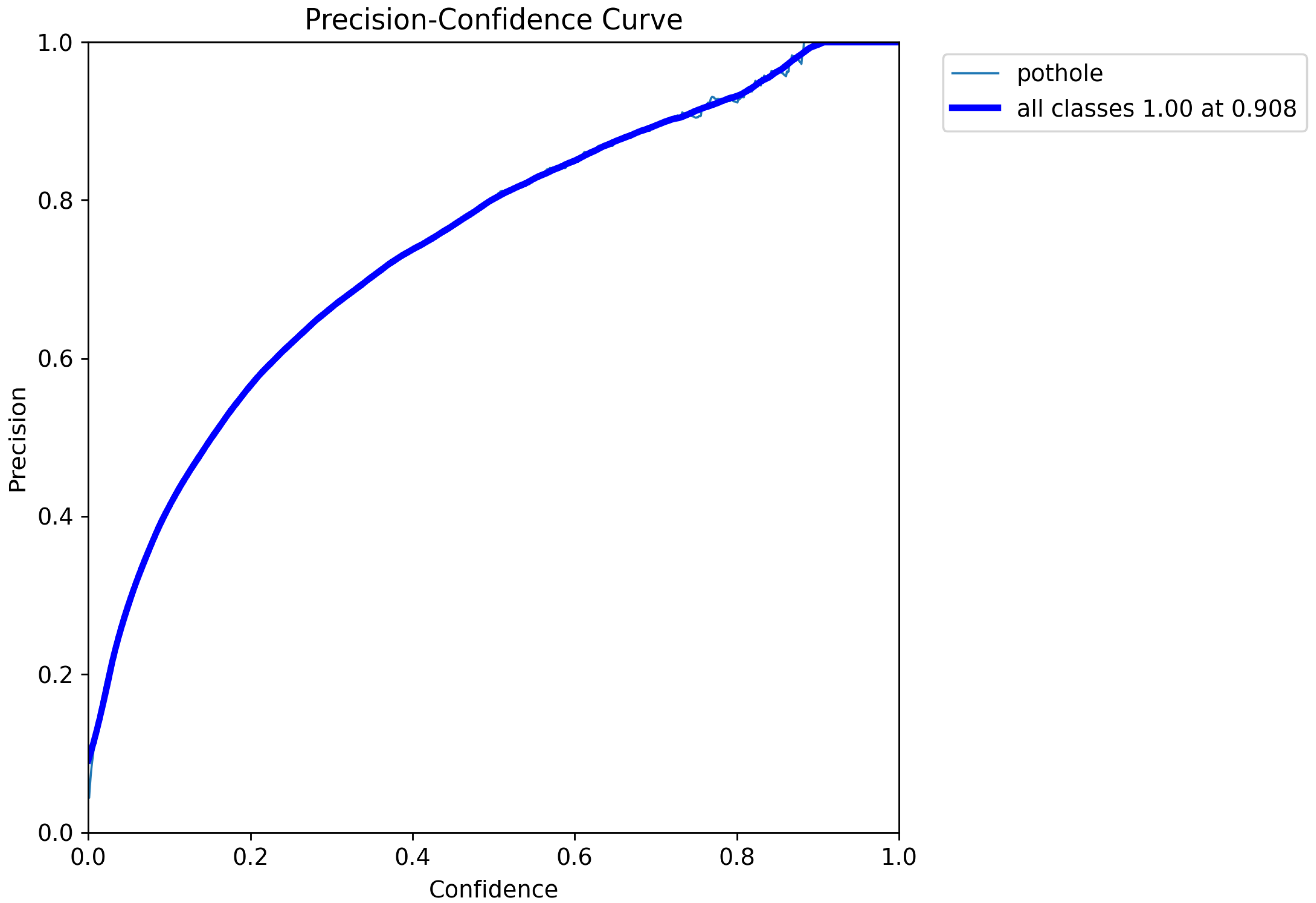

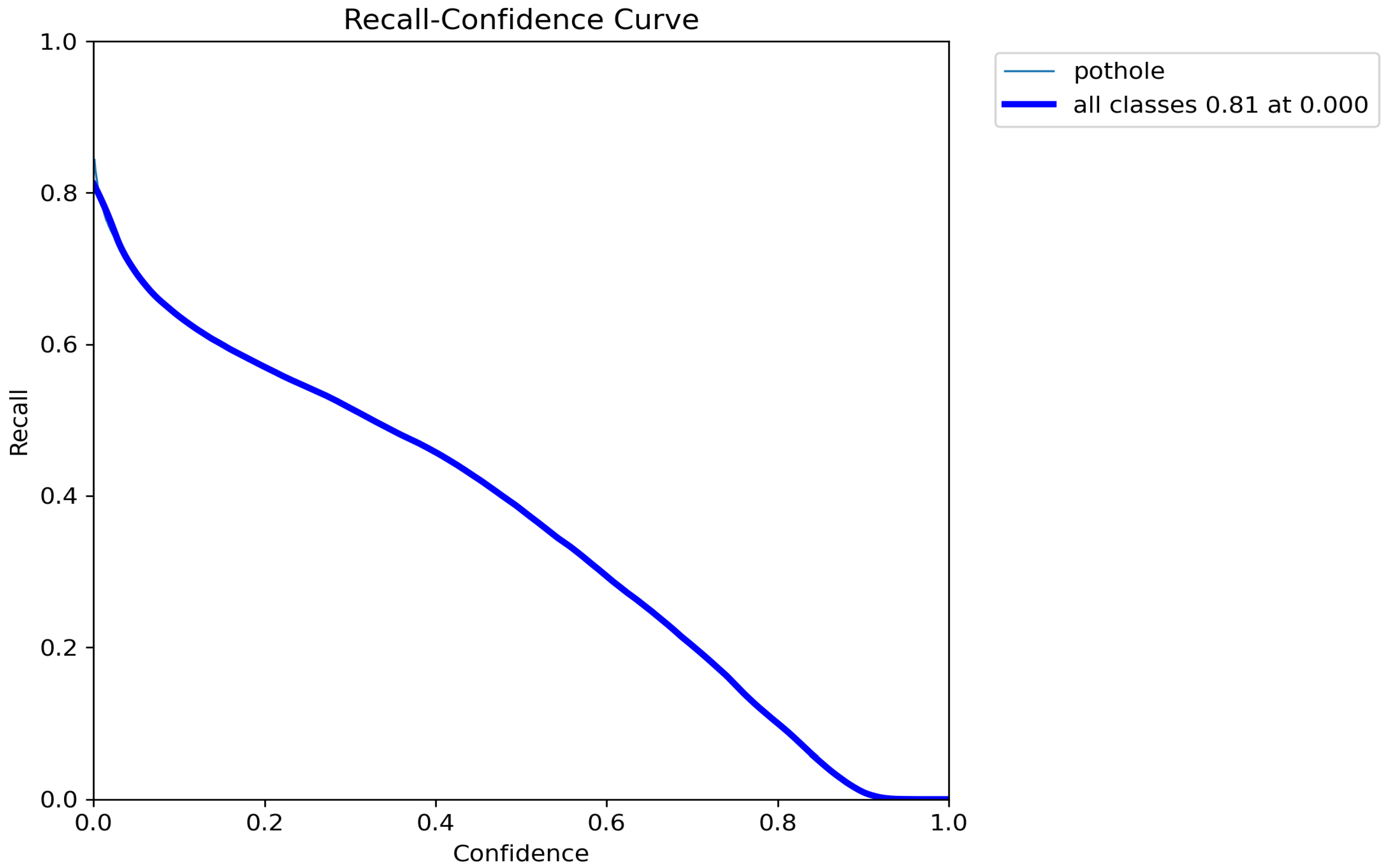

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Mask R-CNN | Mask Region-based Convolutional Neural Network |

| MCDM | Multi-criteria Decision Making |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Ali, F.; Ali, Z.; Khattak, K.; Khattak, T. Evaluating the effect of road surface potholes using a microscopic traffic model. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracking of potholes and measurement of noise and illumination level in roadways. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering 2019, 8, 992–997.

- Road surface guard: ai paved safety. Interantional Journal of Scientific Research in Engineering and Management 2023, 7, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Road pothole detection using unmanned aerial vehicle imagery and deep learning technique. Zanco Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2022, 34. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Tran, V.; Lee, D. Application of various yolo models for computer vision-based real-time pothole detection. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubec, M.; Jakubec, E.; Bučko, B.; Zábovská, K. Comparison of cnn-based models for pothole detection in real-world adverse conditions: overview and evaluation. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, R.; Saeed, Y.; Zeb, A.; Ghazal, T.; Rahman, T.; Saidet, R.; et al. Edge ai-based automated detection and classification of road anomalies in vanet using deep learning. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vupparaboina, K.; Tamboli, R.; Shenu, P.; Jana, S. Laser-based detection and depth estimation of dry and water-filled potholes: a geometric approach. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Kim, T.; Kim, Y. Image-based pothole detection system for its service and road management system. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2015, 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Kim, T.; Kim, Y. Feature-based pothole detection in two-dimensional images. Transportation Research Record Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2015, 2528, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorro, K.; Ranolo, E.; Roble, L.; Santillian, R.N. Road Pothole Detection using YoloV8 with image augmentation techniques.

- Koch, C.; Brilakis, I. Pothole detection in asphalt pavement images. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2011, 25, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Kim, T.; Kim, Y. Image-based pothole detection system for its service and road management system. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2015, 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Fan, J.; Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, L.; et al. Computer vision for road imaging and pothole detection: a state-of-the-art review of systems and algorithms. Transportation Safety and Environment 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, G.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, R.; Li, M.; Han, D.; et al. Aal-net: a lightweight detection method for road surface defects based on attention and data augmentation. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Kim, T.; Kim, Y. Feature-based pothole detection in two-dimensional images. Transportation Research Record Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2015, 2528, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Furukawa, T. Degenerate near-planar 3d reconstruction from two overlapped images for road defects detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharat, R.; Ikotun, A.; Ezugwu, A.; Abualigah, L.; Shehab, M.; Zitar, R. A real-time automatic pothole detection system using convolution neural networks. Applied and Computational Engineering 2023, 6, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, D.; Sahu, S. Potnet: pothole detection for autonomous vehicle system using convolutional neural network. Electronics Letters 2020, 57, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Deep learning-based pothole detection for intelligent transportation: a yolov5 approach. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Khaliq, S.; Yousaf, M.; Ullah, M.; Ahmad, A. Pothole detection using deep learning: a real-time and ai-on-the-edge perspective. Advances in Civil Engineering 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetha, M. Intelligent deep learning based pothole detection and alerting system. International Journal of Computational Intelligence Research 2023, 19, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orugbo, E.; Alkali, B.; Silva, A.; Harrison, D. Rcm and ahp hybrid model for road network maintenance prioritization. The Baltic Journal of Road and Bridge Engineering 2015, 10, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agabu, K. Sustainable prioritization of public asphalt paved road maintenance. International Journal of Engineering and Management Research 2023, 13, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikam, P. Assessment of logistical support for road maintenance to manage road accidents in vhembe district municipalities. Jàmbá Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnyana, I.; Sudarsana, D. Risk analysis on implementation of road maintenance project with steple method in badung, bali. Matec Web of Conferences 2019, 276, 02012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augeri, M.; Greco, S.; Nicolosi, V. Planning urban pavement maintenance by a new interactive multiobjective optimization approach. European Transport Research Review 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, K. Score card utility matrix for prioritization of asphalt paved road maintenance projects. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasegaard, A.; Picard, M.; Hennart, F.; Nielsen, P.; Saha, S. Multi Criteria Decision Making for the Multi-Satellite Image Acquisition Scheduling Problem. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, K.; Arbaiy, N.; Zaidan, A.; Zaidan, B.; Albahri, O.; Alsalem, M.; Salih, M. A new standardisation and selection framework for real-time image dehazing algorithms from multi-foggy scenes based on fuzzy Delphi and hybrid multi-criteria decision analysis methods. Neural Computing and Applications 2020, 33, 1029–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, C.; Cheng, D.; Lin, C.; Lo, C. A real-time pothole detection approach for intelligent transportation system. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2015, 2015, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, D.; Sahu, S. Potnet: pothole detection for autonomous vehicle system using convolutional neural network. Electronics Letters 2020, 57, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Brilakis, I. Pothole detection in asphalt pavement images. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2011, 25, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Kim, T.; Kim, Y. Image-based pothole detection system for its service and road management system. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2015, 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, J.; Sirlantzis, K.; Howells, G. A review on negative road anomaly detection methods. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 57298–57316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Tran, V.; Lee, D. Application of various yolo models for computer vision-based real-time pothole detection. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 11229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Papachristou, C.; Weyer, D. Road pothole detection system based on stereo vision. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, M. What is YOLOv9: An In-Depth Exploration of the Internal Features of the Next-Generation Object Detector. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.07813. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.07813.

- Terven, J.R.; Cordova-Esparza, D.M. A Comprehensive Review of YOLO Architectures in Computer Vision: From YOLOv1 to YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2304.00501. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.00501. [CrossRef]

- Belton, V.; Stewart, T. Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: An Integrated Approach; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).