1. Introduction

One of the major risk factors for the health of inhabitants in urban agglomerations is air pollution. It is generated by human activities, such as road traffic, the use of energy production plants, and industrial activities, which favor the diffusion of gases and very fine dust in the atmosphere.

Pollutants released into the air can be responsible for various pathologies: among the most common are respiratory tract, cardiovascular, and immune system diseases.

Many researchers have addressed the detection of the most critical urban areas, more sensitive to the diffusion of the pollutant and those, instead, more resilient.

Some authors have proposed models for identifying the areas of urban settlements where ventilation was most impeded. In [

1] a method for the detection of ventilation zones in urban settlements was developed, taking into account the compactness of the urban form, the average height of the buildings, and the typology of the prevalent road model. The method was adopted to determine which urban areas were less ventilated and therefore, more at risk in the presence of air pollutants. In [

2] a GIS-based framework has been built aimed at identifying urban areas with lower ventilation potential, which are more at risk in the presence of high concentrations of air pollutants.

Other authors have analyzed the distribution of the pollutant in the urban fabric to evaluate in which types of urban patterns and soils the concentration of the pollutant was particularly high. In [

3] a study was carried out to model, starting from data acquired by mobile stations, the spatial distribution of air pollutants in the metropolitan area of Kano, Nigeria. The study highlighted that the areas most exposed to air pollution are the urban patterns mainly concerning industrial and commercial areas.

In [

4] an air pollution urban hotspots detection method based on the spatiotemporal trend of air pollutants is proposed. To detect hotspots, three parameters are taken into account: the temporal frequency of exceeding threshold values given by the percentage of days in which the thresholds are exceeded, the level of exceeding the threshold values, and the number of consecutive days of exceeding. The method has been applied to detect hotspots in Delhi city, India, considering PM2.5 concentration measurements in the summer months of the years from 2018 to 2021.

A hierarchical clustering method is applied in [

5] to detect urban air pollutant hotspots using data acquired by mobile stations installed on trash-trucks driven along urban streets of Cambridge, Massachusetts. The analysis of the detected hotspots allowed to determine which were the main sources of pollution.

The need to have a large amount of measurements of the concentration of the pollutant makes it difficult to carry out these methods in different urban settlements. Furthermore, they do not take into account other types of environmental and climatic risk that can further increase the phenomenon and the risk for the health of the resident population. In particular, emerging climatic scenarios, such as the presence of increasingly intense summer heat waves, can aggravate both the concentration of air pollutants, for example, due to the absence of ventilated and current areas during periods of heat waves, and the health problems associated with the cardio-respiratory system.

A significant correlation has been highlighted in [

6] between the increase in allergic respiratory diseases, such as rhinitis and bronchial asthma, and environmental and climatic risk factors such as air pollution and the increase in average temperatures. Recent studies have shown that the main determining factors for the onset of respiratory problems among urban residents are the increase in temperatures and exposure to high levels of air pollution. A collection of the results of these studies is included in [

7]. A research in [

8] starting from an analysis of the emotional categories expressed by citizens during heatwaves, has highlighted that the areas where unpleasant emotions prevail and citizens’ discomfort is most felt are urban areas with a high population density of poor and vulnerable.

Several factors can increase or reduce the concentration of pollutants in the atmosphere. These factors are mainly local, connected both to the morphology of the urban settlement (presence or absence of ventilation channels, proximity to the sea, density of buildings, presence of green wooded areas, etc.) and to specific anthropogenic factors such as the presence of industrial plants, excessive use of air conditioners, and road traffic. Furthermore, especially in dense urban settlements, for an analysis of correlations between the concentration of air pollutants and the increase in temperatures it is necessary to consider multiple parameters that characterize the study area.

A study of the distribution of air pollutants in urban settlements to determine critical urban areas was performed in [

9]. The authors propose a method in which the urban settlement is partitioned into Thiessen polygons based on the daily concentration of pollutants measured by fixed air quality monitoring stations located in the urban settlement during a heatwave period. They test the method on the city of Bologna in Italy. This method is computationally fast; however, the partitioning into Thiessen polygons can provide a poor, accurate spatial distribution of the pollutant concentration; this can affect the spatial accuracy of the detected hotspots.

The kernel density method is applied in [

10] to assess the spatial distribution of pollutant concentration and to detect hotspots. This method, however, is not applicable to detect air pollutant hotspots from fixed air quality monitoring stations, as it requires a high spatial resolution of the measurement points.

Forecasting models are proposed by some authors for assessing the air pollutant spatial distributions. Fuzzy time series [

11,

12] and fuzzy Markov chains [

13] are applied for predicting the daily air pollution indices. The critical point of these models is that the forecasting accuracy depends on the number of partitions of the model.

To increase the forecasting accuracy and the spatial accuracy of the air pollutant hotspots, deep learning techniques based on long short-term memory networks have been recently proposed in [

14,

15,

16,

17] to predict the spatial distribution of air pollutant concentrations. Although increasing the accuracy of predictions compared to traditional models, these models are computationally expensive and require metaheuristic approaches for parameter setting [

18].

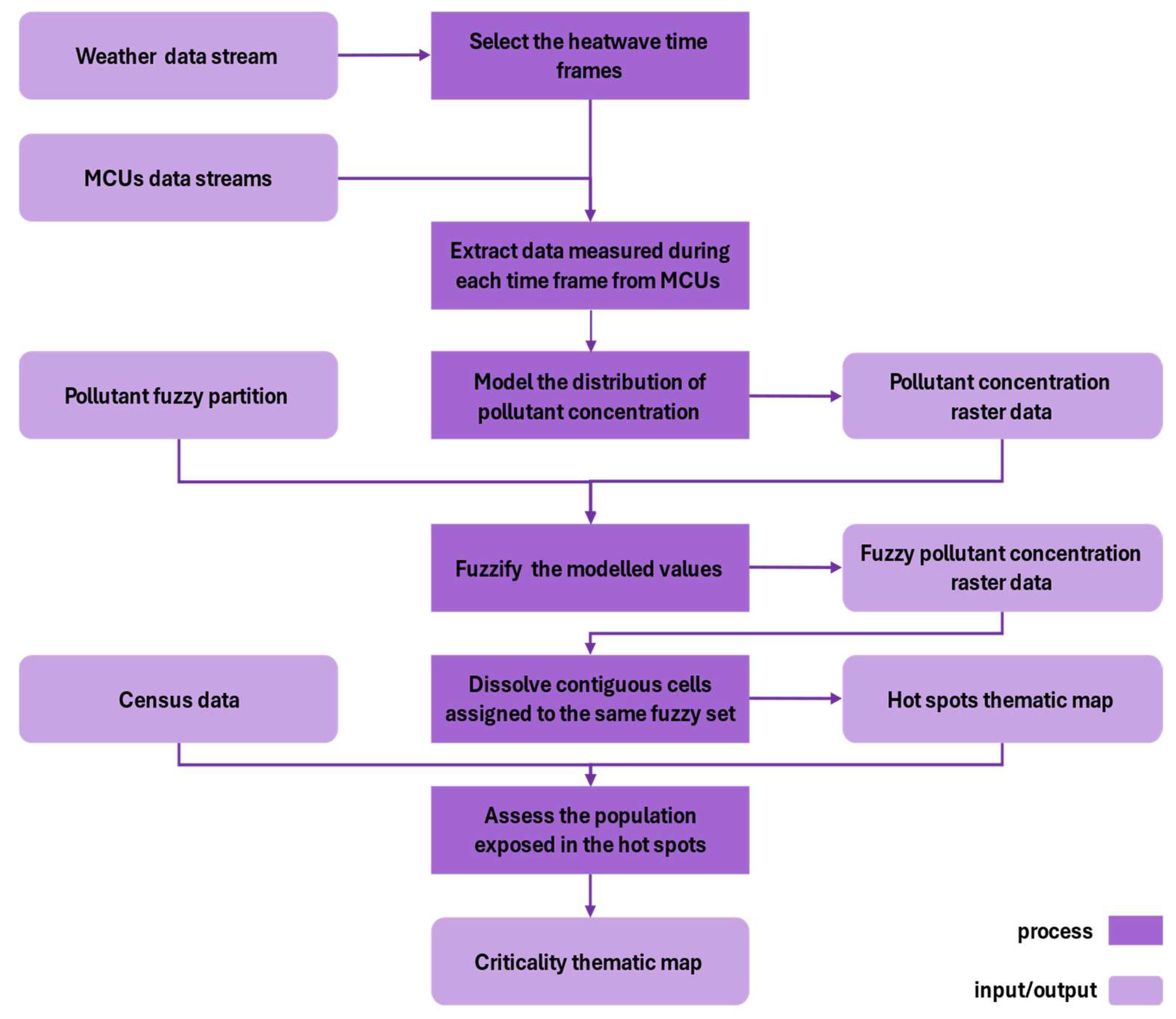

In this research we propose a new method for detecting air pollution hotspots in urban settlements, aimed at detecting urban air pollution hotspots generated during heatwaves and determining which urban areas included in hotspots are more critical due to a greater risk for the health of vulnerable citizens.

Following [

19], to detect hotspots, a pre-analysis is carried out to determine, during the investigation period, those time steps in which the phenomenon occurred in the study area. For this purpose, a preprocessing phase is set up in which the time intervals in which heat waves occurred (time frames) are determined for the entire investigated period.

For each time frame, daily data on the concentration of the air pollutant measured by a set of monitoring central units (MCUs) are collected, and daily weighted averages of the concentration of the pollutant during the time frames are calculated, considering as a weight the duration of the heatwave in number of consecutive days. The spatial distribution of the air pollutant during hotspots is modeled using a spatial interpolation method.

After modeling the average distribution of the pollutant during the time frames, a fuzzification process is used to classify the urban areas based on the level of criticality for the health of the residents. The urban areas classified with high levels of air pollutant concentration are identified as hotspots. Finally, a criticality map is built in which, within each hotspot, the most critical areas are detected for a higher density of weak population, exposed to the risk of worsening of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

The model provides a high portability as it does not require a considerable amount of data, using only the daily measurements of the stations and the population census data necessary to determine the density of residents exposed to risk. Furthermore, it is user-friendly, as it does not require the setting of numerous parameters and uses a fuzzification approach that allows the user to better evaluate the potential critical issues for the health of residents in hotspot areas during heatwaves. It can become a useful tool to support local decision-makers in determining which urban areas are most at risk; it is a priority to adopt design strategies and interventions to protect the health of residents.

The proposed method is discussed in detail in section 2. In section 3 the case study is presented. The results of the experimental tests are shown and discussed in

Section 3. Concluding remarks are given in

Section 4.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, a method of detection of hotspots of the study area was tested, in which critical values of an air pollutant are measured during heat waves that occurred in the summer months.

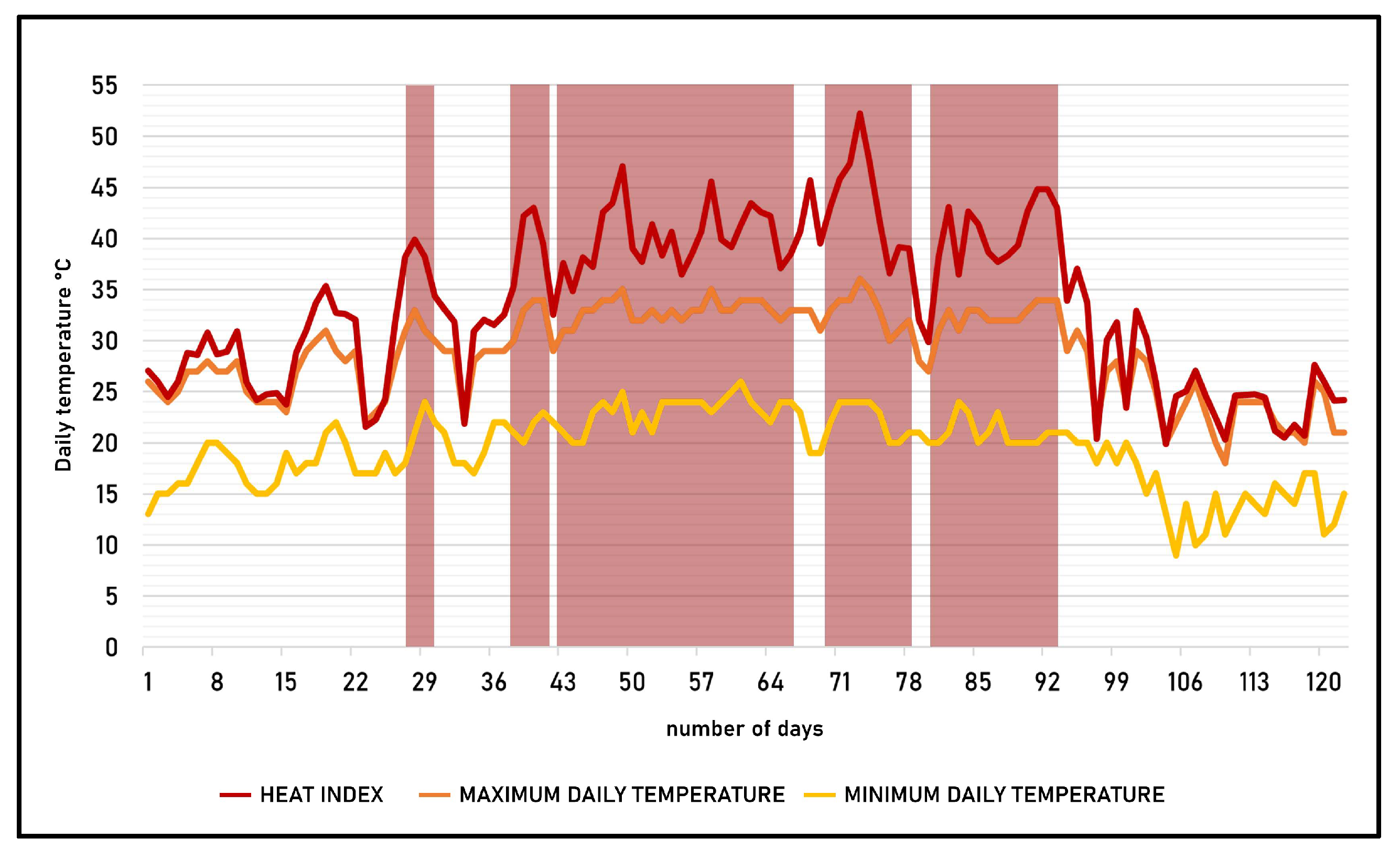

In the investigation period, the time frames in which heat waves were recorded in the study area are determined. Following [

20], a heatwave time frame is detected by the presence of a Heat Index value higher than 32 °C for at least three consecutive days, where the Heat Index is a measure of perceived temperature defined by the USA National Weather Service, combining daily air temperature and relative humidity [

21].

Subsequently, for each of these time frames, the daily measurements of the air pollutant concentration recorded by the monitoring central units (MCU) located in the study area are extracted. For each time frame, a spatial interpolation algorithm is performed to model the distribution of the pollutant concentration in the study area. Upon completion of the construction of the pollutant distribution for each time frame, a raster data is generated in which each cell is assigned the average value of the pollutant concentration in the individual time frames, weighted by the duration of the time frame. Then, a fuzzification process is performed in which each cell is assigned the label of the fuzzy set to which it belongs with the highest degree of membership. Finally, an aggregation process is performed in which the contiguous cells assigned to the same fuzzy sets are merged to form polygons on the map. The result of this process is a thematic map in which the polygons classified as polygons classified with high danger levels constitute hot spots where the population is most at risk.

Formally, let t1, …, tn be the time frames in which occurred a heatwave and let di the duration of the ith heatwave, given in number of days. With is denoted the average daily peak of pollutant concentration recorded by the jth monitoring station in the ith time frame. The set Mi = {} represents the set of average daily peak of pollutant concentration registered by all the N monitoring units located in the study area.

The result of the spatial interpolation process applied to the set of data points Mi is a raster data in which denote the interpolated value in the (h,k)th cell covering the study area

At the end of the spatial interpolation process performed for all n time frames, a raster is constructed in which each cell is assigned the weighted average of the interpolated values, where the weight is the duration of the heatwave. The value assigned to the (h,k)

th cell is given by:

To perform the fuzzification process a fuzzy partition of the concentration of air pollutants is created by an expert, based on the severity on people’s health. The fuzzy partition is constructed using fuzzy numbers and respecting Ruspini condition, a constraint which establishes that the sum of the membership degrees of an element to the fuzzy sets of the fuzzy partition is equal to 1 [

22].

The fuzzification process assigns to the (h,k)th cell the label of the fuzzy set to which the value belongs with the greatest membership degree.

Then, all contiguous cells belonging to the same fuzzy set are dissolved to form a polygon on the map. Polygons classified with high danger levels are considered hot spots.

In order to determine the most critical areas, an assessment of the population most exposed to health risk residing in each hotspot is carried out. This is done by acquiring population census data and calculating the estimate of the exposed population residing in the hot spot.

The result of the process is a thematic map in which the hotspots are classified based on the criticality for residents exposed to health risk.

The component labelled Model the distribution of pollutant concentration executes for each time frame a spatial interpolation process; then it creates a raster called Pollutant concentration raster data using the formula (1).

The component labelled Fuzzify the modelled values use the fuzzy partition of the concentration of pollutant (Pollutant fuzzy partition) to fuzzify the values of the concentration of pollutant, returning a raster in which each cell is assigned the label of the fuzzy set to which it belongs with the highest membership degree (Fuzzy pollutant concentration raster data). After dissolving contiguous cells classified with the same label a thematic map showing the hot spots in the area of study is extracted, where are considered hot spots, polygons classified with high concentration of pollutant.

Finally, the functional component Assess the population exposed in the hotspot estimates, starting from the population census data, the population most at risk for health residing in each hotspot, and builds a thematic map in which each hotspot is classified with criticality levels based on the resident population exposed.

3. The Case Study

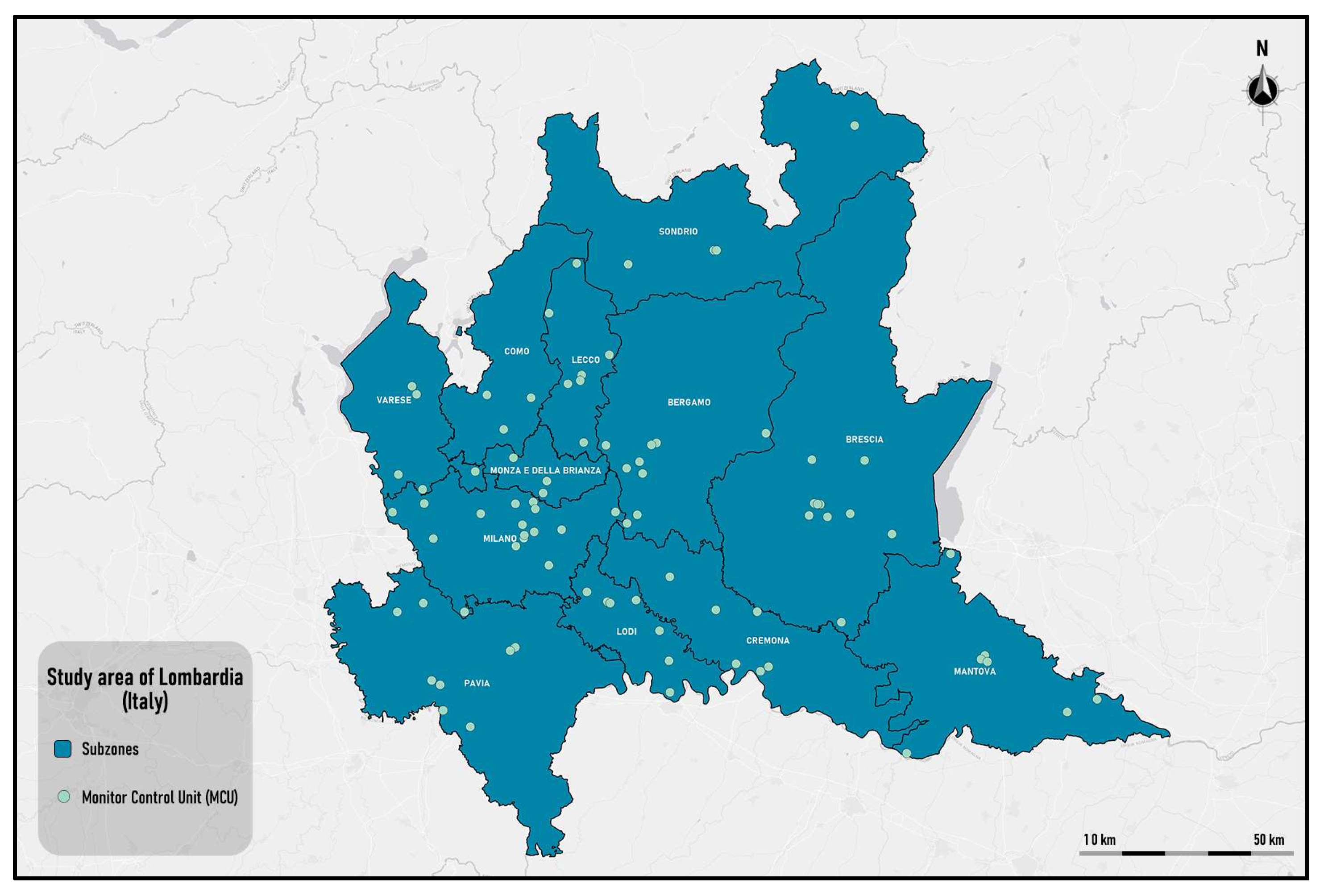

The framework was tested on a study area extending to the Lombardy region, in Italy, to detect the most critical areas for the presence of high concentrations of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) during heatwaves in the year 2024.

Nitrogen dioxide is formed in the atmosphere by the oxidation of nitrogen monoxide (NO) emitted mainly by anthropogenic sources due to industrial combustion processes, heating systems and vehicular traffic, as well as by production processes without combustion, such as the use of nitrogen fertilizers in agriculture.

It causes alterations in lung function in humans, generating chronic bronchitis, asthma and pulmonary emphysema. The subjects most at risk are children and people already affected by respiratory diseases (asthmatics), as well as those living near roads with high traffic density due to long-term exposure.

The surface of Lombardy is divided almost equally between plains (which represent about 47% of the territory) and mountainous areas (which represent 41%). The remaining 12% of the region is hilly.

Lombardy is the Italian region with the highest population density and is the one with the greatest industrial vocation. Air pollution is among the issues that have most worried local administrators, which for several years have promoted policies to reduce pollutants with the aim of respecting the limit values of the annual averages. In particular, in recent years the average annual values of NO2 recorded by the MCUs located in the Lombardy region have been below the limit value of 40 μg/m3.

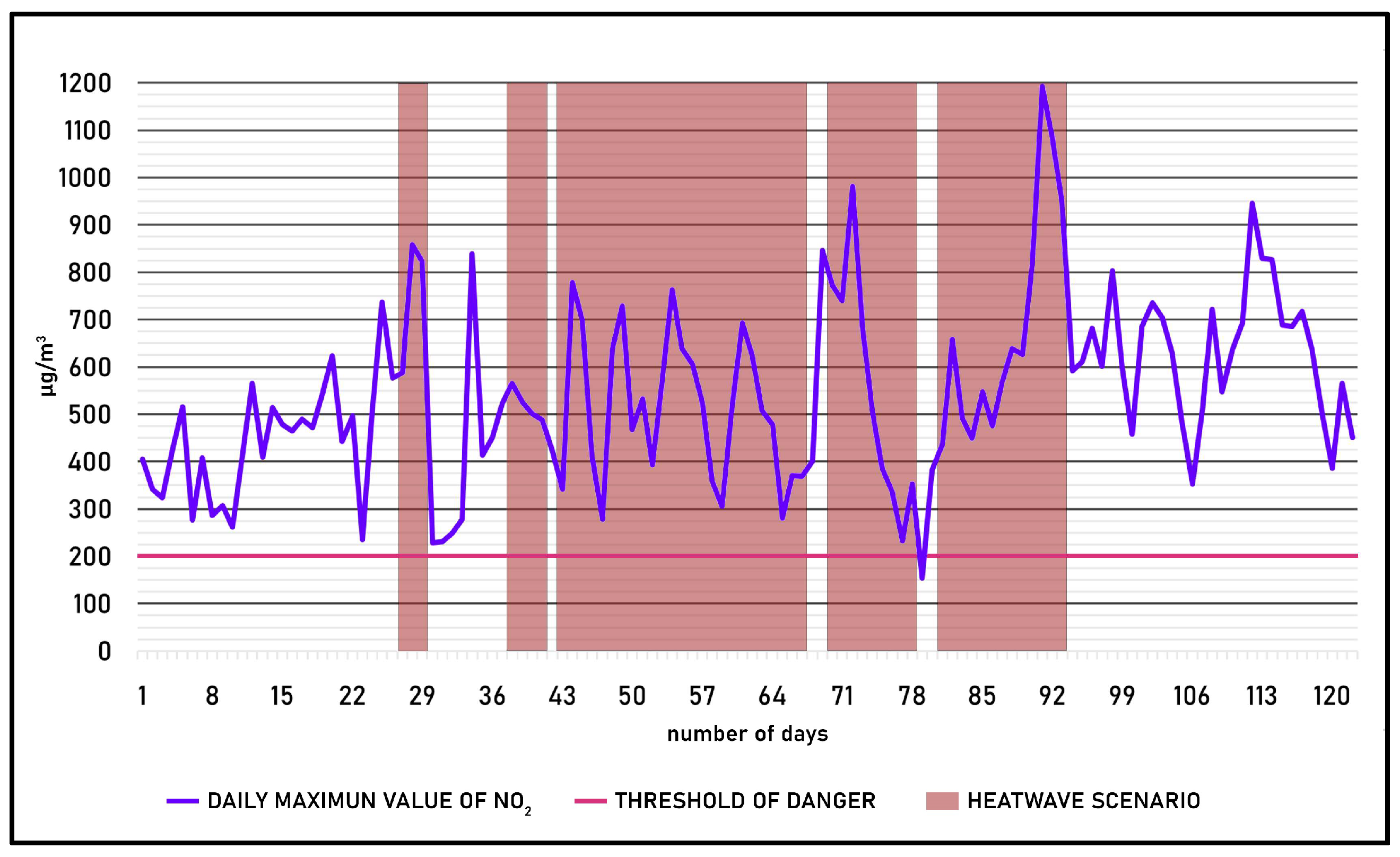

However, in several periods of the year, hourly values higher than the hourly threshold of 200 μg/m3defined by the World Health Organization have been recorded, especially in dense urban settlements.

The Lombardia Region is divided into twelve Provinces: Bergamo, Brescia, Como, Cremona, Lecco, Lodi, Mantua, Milan, Monza and Brianza, Pavia, Sondrio, Varese.

The Monitor Control Unites that record the different types of pollutants are 162 in total, of which 85, shown on the map, monitor the NO2 parameter.

The largest number of MCUs is concentrated in the provinces of Milan (16) while the province of Sondrio has the smallest number of MCUs in its territory (4).

The analysed time period extends from June 1st to September 30th, 2024, for a total of 123 consecutive natural days.

Figure 3 shows the trend of the indicators needed to estimate the heatwave scenario: the daily maximum temperature, the daily minimum temperature, and the heat index.

The figure shows that during the analysed period five heatwave scenarios with different durations occurred.

Table 1 shows the summary data of the scenarios.

The heatwave scenario with the longest duration is number 3 with a total duration of 25 consecutive natural days.

By analyzing the data of the NO

2 parameter, obtained from the MCU of the study area located in the province of Milano, the trend of the parameter was calculated in the entire period by comparing it with the recorded heatwave scenarios; the trend is shown in

Figure 4.

The graph shows that there is no strong correspondence between the concentration peaks of the NO2 parameter and the heatwave scenarios; However, it is evident that the parameter records its highest values during the occurrence of some heatwave scenarios.

The fuzzy partition was created by referring to the Italian national legislative decree n° 155 of 2010, which establishes, as thresholds for the health of citizens, two hourly thresholds of NO

2 concentration, a minimum threshold of 100 μg/m

3 and a maximum of 140 μg/m

3, equal to 50% and 70%, respectively, of the hourly limit value of 200 μg/m

3 established by the World Health Organization [

23]. Furthermore, the legislative decree establishes a highly critical alarm threshold of 400 μg/m

3, equal to 2 times the limit value.

Figure 5 shows the fuzzy partition. It is composed of five fuzzy sets, labeled

Normal, To be monitored, Dangerous, Critical and

Very critical. Each fuzzy set is constructed as a triangular fuzzy number.

The population exposed to risk is constituted by the disadvantaged resident density [

20], measured as the number of disadvantaged residents per square kilometer, where the number of disadvantaged residents is given by the number of children under 6 years of age and elderly people over 74 years of age.

To calculate the index, the 2024 population census data provided by the Italian Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) were acquired, the national body that periodically carries out the population census by census area throughout the Italian territory.

Following [

20], the disadvantaged resident density is considered critical if is equal or greater than 5000 disadvantaged residents per square kilometer. The criticality map is built determining the critical areas inside hotspots. In

Table 2 is shown the classification of the disadvantaged population density.

The model was implemented in the GIS platform the ESRI ArcGIS Pro Suite using the ESRI Python library.

The test results are presented and discussed in the next section.

4. Results

The spatial distribution of the NO2 parameter was performed through a kriging operation. Starting from the daily readings of the NO2 parameter in the 85 stations of the study area, for each heatwave scenario, the daily peaks were considered as input data for the kriging process. The process settings include a size of each cell of 50x50 meters, and the use of the exponential semivariogram model.

The kriging was performed for all five heatwave scenarios, subsequently, with a Map algebra process, a raster was created through the weighted average of the kriging of the individual scenarios, in which the weights are attributed based on the duration of each scenario, expressed in numbers of consecutive days as reported in

Table 2. The raster calculator result is shown in

Figure 6.

Starting from the average kriging, we classified the raster into five classes, based on the values reported in the Italian national legislative decree n° 155 of 2010, shown in

Table 3.

In

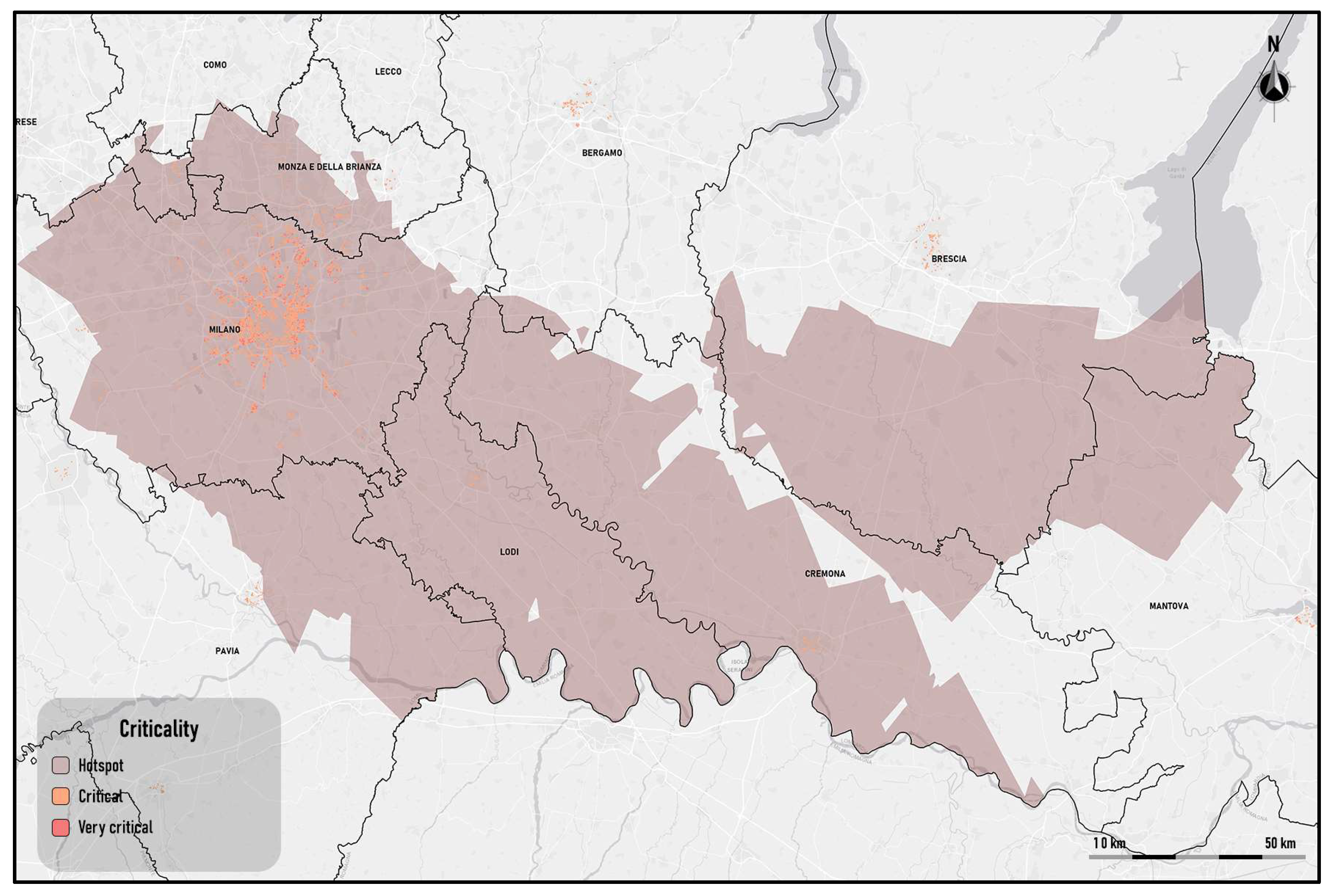

Figure 7, are shown the two hotspots emerged.

The first extends over almost the entire area of the province of Milan and Cremona, completely including the province of Lodi.

The other hotspot, compared to the previous one, has a smaller surface extension, and it is in the immediate vicinity of the former, specifically in the southern area of the province of Brescia, on the border with the district of Mantova.

Figure 8 shows the distribution of disadvantaged population density in the study area. The thematic map classes were developed starting from

Table 2.

The areas with the highest density are concentrated in the provinces of Milan, Monza and Brianza, Bergamo and Brescia. The northern provinces have the lowest density of disadvantaged population.

These outcomes are in line with the results of the analysis performed in [

24] where both a network of ground-based sensors and satellite images were used to obtain a precision distribution of NO2 concentration over ta an area including the metropolitan city of Milan. The most critical zones were the ones including the city of Milan and the areas of the provinces of Monza and Brianza.

Starting from the detection of NO2 hotspots and the assessment of the exposed population, the most critical areas for the population exposed to NO2 emissions have been identified.

The hotspot located in the east does not present critical areas; on the contrary, the hotspot with the largest extension presents Critical and Very Critical areas near the city of Milan, in the southern area of the province of Monza and Brianza, and in correspondence with the densest urban aggregates of the provinces of Lodi and Cremona.

This result confirms the conclusion of a work carried out in [

25] in which the air quality was assessed in 14 large Italian cities, in the decade from 2006 to 2016, collecting data on the concentration of PM

10, PM

2.5 and NO

2 from ground-based stations, as well as data on public transport and emissions from motor vehicles. Even with a gradual decrease, it was found that the most critical areas where the concentration of NO

2 remains very high and, above all, due to the exhaust gas produced by motor vehicles, are the two large cities of northern Italy Turin and Milan.

5. Conclusion

An air pollutant hotspot detection method in urban settlements during heatwaves is presented.

After selecting the time frames during which heatwaves were recorded over the study area, the data relating to the concentration of the pollutant measured by MCUs during the time frames were extracted and a daily mean value of the pollutant weighted for the duration of the heatwave was calculated. A spatial interpolation algorithm is used to obtain the distribution of the concentration of the pollutant. Then, through a fuzzification process, the hotspots consisting of the areas where the concentration of the pollutant is highly critical for the health of the inhabitants are extracted. Finally, by analyzing the distribution of the exposed population within the hotspots, a criticality map is extracted in which the areas of greatest criticality included in the hotspots are highlighted. The method was tested on an urban study area extended to the Lombardy region, in Italy. The population density younger than 6 years and older than 74 years was considered as the value exposed to risk.

The results highlight a critical urban area that includes the metropolitan city of Milan, in line with the experts’ assessments and with assessments and predictions in the literature.

Compared to other air pollutant hotspot detection approaches, this method has the advantage of not requiring the setting of parameters to be optimized and of pollutant concentration measurements with high spatial resolution, ensuring high portability. It represents a tool to support various decision makers, such as local administrators, air pollution monitoring and control bodies, and citizen health protection bodies.

The critical point of this method is that it may be inaccurate if the density of MCUs in the study area is insufficient to ensure the restitution of an accurate spatial distribution of the pollutant. This may happen in rural areas or with low population density, where the number of MCUs covering the study area is unsatisfactory to provide an accurate spatial distribution of the pollutant.

In the future we intend to extend the application of the method to different types of air pollutants and to various types of population exposed to health risks. Additionally, further development of the research will concern the integration of the method in medium and long-term forecasting models to predict possible future scenarios of alarm for the health of citizens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; methodology, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; software, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; validation, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; formal analysis, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; investigation, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; resources, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; data curation, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; writing—review and editing, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; visualization, B.C., F.D.M., C.M., and V.M.; supervision, B.C., F.D.M., and V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, B.-J.; Ding, L.; Prasad, D. Enhancing urban ventilation performance through the development of precinct ventilation zones: A case study based on the Greater Sydney, Australia Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badach, J.; Voordeckers, D.; Nyka, L.; Van Acker, M. A framework for Air Quality Management Zones—Useful GIS-based tool for urban planning: Case studies in Antwerp and Gdańsk. Build. Environ. 2020, 174, 106743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oji, S.; Adamu, H. Air Pollution Exposure Mapping by GIS in Kano Metropolitan Area. Pollution 2021, 7, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Gulia, S.; Goyal, S.K. Identification of air pollution hotspots in urban areas - An innovative approach using monitored concentrations data. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 798, 149143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouza, P.; Anjomshoaa, A.; Duarte, F.; Kahn, R.; Kumar, P.; Ratti, C. Air quality monitoring using mobile low-cost sensors mounted on trash-trucks: methods development and lessons learned. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 60, 102239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, G.; Vitale, C.; De Martino, A.; Viegi, G.; Lanza, M.; et al. Effects on asthma and respiratory allergy of Climate change and air pollution. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2015, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholy, J.; Pongrácz, R. A brief review of health-related issues occurring in urban areas related to global warming of 1.5 °C. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 30, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardone, B.; Di Martino, F.; Miraglia, V. A GIS-Based Hot and Cold Spots Detection Method by Extracting Emotions from Social Streams. Future Internet 2023, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardone, B.; Di Martino, F.; Miraglia, V. A GIS-Based Fuzzy Model to Detect Critical Polluted Urban Areas in Presence of Heatwave Scenarios. Computers 2024, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-P.; Chu, H.-J.; Wu, C.-F.; Chang, T.-K.; Chen, C.-Y. Hotspot Analysis of Spatial Environmental Pollutants Using Kernel Density Estimation and Geostatistical Techniques. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, H.; Lu, H. Application of a novel early warning system based on fuzzy time series in urban air quality forecasting in China. Applied Soft Computing. 2018, 71, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.W.; Wong, S.W.; Selvachandran, G.; Long, H.V. Prediction of Air Pollution Index in Kuala Lumpur using fuzzy time series and statistical models. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health. 2020, 75, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousifi, Y.; Othman, M.; Sokkalingam, R.; Faye, I.; Silva, P.C.L. Predicting Daily Air Pollution Index Based on Fuzzy Time Series Markov Chain Model. Symmetry 2020, 12, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navares, L.; Aznarte, J.L. Predicting air quality with deep learning LSTM: Towards comprehensive models. Ecol. Inform. 2020, 55, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Wang, W.; Jiao, L.; Zhao, S.; Liu, A. Modeling air quality prediction using a deep learning approach: Method optimization and evaluation Sustainable. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacanin, B.N.; Sarac, M.; Budimirovic, N.; Zivkovic, M.; AlZubi, A.A.; Bashir, A.K. Smart wireless health care system using graph LSTM pollution prediction and dragonfly node localization. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2022, 35, 100711–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavana, H.; Prathik, N.R. Deep Learning-Based Air Pollution Forecasting System Using Multivariate LSTM. In Artificial Intelligence Tools and Technologies for Smart Farming and Agriculture Practices; Gupta, R.K., Jain, A., Wang, J., Bharti, S.K., Patel, S., Eds.; IGI Global Publishing: Beijing, China, 2023; pp. 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewil, G.I.; Al-Bahadili, R.J. Air pollution prediction using LSTM deep learning and metaheuristics algorithms. Meas. Sens. 2022, 24, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardone, B.; Di Martino, F. Fuzzy-Based Spatiotemporal Hot Spot Intensity and Propagation—An Application in Crime Analysis. Electronics 2022, 11, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, V.; Di Martino, F.; Miraglia, M. A GIS-based framework to assess heatwave vulnerability and impact scenarios in urban systems. Scientific Report 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, G. Brooke; Bell, Michelle L.; Peng, Roger D. Methods to Calculate the Heat Index as an Exposure Metric in Environmental Health Research”. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2013, 121, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruspini, E.H. A new approach to clustering. Inf. Control. 1969, 15, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide. World Health Organization. 2021. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/345329 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Cedeno Jimenez, J.R.; Brovelli, M.A. NO2 Concentration Estimation at Urban Ground Level by Integrating Sentinel 5P Data and ERA5 Using Machine Learning: The Milan (Italy) Case Study. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassetti, L. , Torre, M., Tratzi, P., Paolini, V., Rizza, V., Segreto, M., & Petracchini, F. Evaluation of air quality and mobility policies in 14 large Italian cities from 2006 to 2016. Journal of Environmental Science and Health 2020, 55, 886–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).