1. Introduction

Thyroid cancer (TC) is the most common endocrine malignancy although it accounts for only 2.2% of all new cancer cases in the United States [

1]. Incidence rate of TC has been increasing until recently, a fact that could be partially attributed to the extended use of diagnostic imaging tools such as ultrasound (U/S), computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), where even small thyroid nodules are incidentally detected during medical work-up of a disease other than thyroid [

2,

3,

4]. However, since 2014, a decreasing trend has been observed, which is due to the adoption of stricter diagnostic criteria. Nevertheless, the number of new cases and deaths remains relatively high. It is estimated that in 2024 new thyroid cancer cases will be up to 44,020 (12,500 in men and 31,520 in women) while deaths will be up to 2,170 (990 in men and 1,180 in women) [

5,

6].

The majority of TC cases (~90%) arise from thyroid follicular cells with the well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma (WDTC) being the most common pathological entity. WDTC is further divided, based on histopathological criteria, into two main subtypes, papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC, 75 - 80% of cases) and follicular (FTC, 8 - 10% of cases) [

7,

8]. In the updated World Health Organization (WHO) 2022 classification of thyroid neoplasms, invasive encapsulated follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma (IEFV - PTC) and oncocytic carcinoma (OCA), which based on the previous WHO 2017 classification, was called Hürthle cell, are described as autonomous pathological entities [

9,

10]. Prognosis of WDTC is favorable with the 5-year relative survival rate (data from 2012 - 2018) being up to 98% even in cases of locoregional metastatic disease, while in cases of distant metastases, this falls to 67 - 74% [

11,

12]. FTC tends to behave more aggressively than PTC, presenting more frequently vascular invasion and distant metastases thus, characterized by poorer prognosis [

13,

14,

15]. Other types of thyroid carcinomas include medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) (~3 - 5% of thyroid carcinomas) which arises from the parafollicular C - cells of the thyroid gland, differentiated high-grade thyroid carcinoma (DHGTC) which compromises a new pathological entity with intermediate prognosis, poorly differentiated (PDTC) (2 – 5%), and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) (~1%) both characterized by a relatively poor prognosis [

16,

17,

18].

Albeit WDTC is characterized by an excellent prognosis structural incomplete response (SIR) to the initial treatment (i.e surgery and selective use of Radioiodine (RAI) Ablation) may be present in 2 - 6% of American Thyroid Association (ATA) low risk patients, 19 – 28% of ATA intermediate risk and up to 75% of ATA high risk thus, leading to additional treatments and active monitoring [

19,

20,

21,

22]. The term SIR may refer to disease persistence or recurrence and thus appropriate discrimination should be applied regarding these two different entities. According to the largest study to date which managed to elucidate the differences between persistence and recurrence in TC, persistence was defined as the “presence of disease ab initio since diagnosis” while true recurrence was defined as a “relapse after being 12 months disease-free”, with the two conditions being characterized by different clinical outcomes [

23]. Local persistence or recurrence is present in 5 – 7% of WDTC patients with surgical central or/and lateral neck dissection constituting the optimal therapeutic approach, under the condition of biopsy-proven disease [

19,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Surgery is particularly recommended for central neck nodes ≥ 8 mm and lateral neck nodes ≥ 10 mm in the smallest diameter that can be localized on anatomic imaging [

19]. On the other hand, in cases of, smaller or/and iodine refractory local metastases, patient reluctance or inability to undergo revision surgery, active surveillance (AS) and non-surgical, minimally invasive treatments (MIT) should be considered [

19,

28]. These may include, but are not limited to, ethanol ablation, laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), microwave ablation, cryoablation and high-intensity focused U/S [

19,

24].

RFA is a thermal ablation technique that can be used to destroy neoplastic tissue by increasing the intra-tumoral temperature to more than 55

0C, through an electrode tip which combines frictional and conduction heat, generated from high-frequency alternating electric current oscillating between 200 - 1200 kHz [

25,

29]. It was introduced as an alternative therapeutic modality to treat local recurrence of WDTC by Dupuy in 2001 with very promising results [

30]. Currently, RFA has gained increasing interest for the treatment both of benign thyroid nodules (including autonomously functioning thyroid adenomas) to overcome symptomatic disease or cosmetic issues as well as of malignant thyroid tissue (micro-PTC or local persistence / recurrence) in selective cases [

31,

32,

33,

34]. The use of RFA as palliative treatment is also under consideration in a few cases of advanced MTC and ATC [

26,

29,

35]. Regarding cervical WDTC recurrence, RFA has emerged as a reasonable therapeutic modality showing adequate efficacy in numerous studies, albeit the majority of them included small patient cohorts [

32,

33,

34,

36,

37,

38,

39]. It is characterized by a low complication rate of 2.38 %, with minor adverse events such as pain, hematoma, vomiting, skin burns, and transient thyroiditis. Major complications are rare and may include dysphonia (permanent or transient), nodule rupture, permanent hypothyroidism, and brachial plexus injury [

40]. Other serious complications may result from injury to the esophagus, trachea, and other nerves such as sympathetic ganglion, spinal accessory and phrenic nerves [

41,

42]. As data regarding RFA’s efficacy in recurrent thyroid cancer are still limited coming mainly from single-center studies, it has not yet been established as a widely recommended therapeutic modality by clinicians, especially in Western Europe and the United States [

26,

34]. The aim of this retrospective study is to present eight DTC cases with locoregional SIR (persistent or recurrent disease) and evaluate for the first time in Greece the safety and efficacy of RFA as an alternative treatment modality for locoregional disease control.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

A total number of eight patients (6 women) were retrospectively studied between June 2021 and December 2024 after they referred to the Thyroid Cancer Outpatient Clinic of the 401 General Military Hospital of Athens due to locoregional SIR as detected by high-resolution U/S and confirmed by U/S-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and measurement of Thyroglobulin (Tg) in the washout fluid. Main inclusion criteria were: personal history of DTC as confirmed by histopathological examination with disease persistence or recurrence following initial treatment (i.e total thyroidectomy with or without lymph node (LN) dissection according to presurgical findings on U/S and with or without RAI ablation), number of lesions (cervical LNs and/or malignant soft tissue) ≤ 2, size of lesions ≤ 8 mm (central compartment) and ≤ 10 (lateral compartments) in the smallest diameter, patient’s unwillingness to undergo AS or revision surgery, written informed consent to undergo RFA with the annotations that: the optimal treatment for cervical recurrent/persistent disease is surgery, AS is a reasonable choice in cases of smaller lesions, existence of other malignant cervical lesions not detected by high-resolution U/S cannot be excluded. Exclusion criterion was the presence of distant metastases as confirmed by anatomic imaging (post-RAI Whole Body Scan (WBS), CT scan, MRI, Fludeoxyglucose-18 (FDG) Positron Emission Tomography (PET) - CT scan). Persistent or recurrent disease was defined as SIR < 12 or ≥ 12 months respectively, after initial surgical treatment [

23]. The following information was extracted from patients’ medical records: demographics, clinical, histopathological and biochemical data, therapeutic interventions and complications of treatment. Patients were followed with biochemical profile (Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), Free Thyroxine (FT4), Antithyroglobulin antibodies (AntiTgs)) and high-resolution U/S at regular time intervals, one month, three months and then every three months, after RFA was performed.

2.2. Biochemistry

Measurements of thyroid biochemical parameters (TSH, FT4, Tg, AntiTg) were made on blood samples collected between 8:00 and 9:00 AM prior to RFA and during follow – up by Beckman Coulter RIA/IRMA (Radioimmunoassay/Immunoradiometric Assay) KIT, according to standard laboratory protocols. The same KIT was used to evaluate Tg levels of washout fluid.

2.3. RFA Procedure

The RFA procedure was performed at the Day Clinic of Saint Savvas Anticancer Oncological Hospital of Athens by the same experienced interventional radiologist. Patients were placed in supine position with their neck fully extended. Targeted lesions and anatomic structures were visualized by U/S in real time using a GE LOGIQ P9 U/S system with linear probe operating at a frequency of 6 to 14 MHz. Volume of targeted lesions was calculated using the equation:

Local anesthesia with lidocaine (2 % cream) was applied for mild local analgesia after routine disinfection. RFA was performed with the moving shot technique after hydrodissection using cold (0-4 °C) dextrose 5% in water (D5W) which was injected between the targeted lesion and vital structures to create a safe zone thus preventing thermal injury. A 19-gauge internally cooled electrode (STARMed, Seoul, South Korea) that was 7 cm in length with a 0.5-cm active tip was used powered by a VIVA RF generator (STARMed). Voice evaluation was assessed by asking patients to verbalize during the procedure; patient’s vital signs were continuously observed, accordingly. The energy applied per unit volume (E/V) was calculated as follows:

Ablation was completed when the targeted lesion became hyperechoic. Consequently, every patient was hospitalized in the Short Stay Unit (SSU) for at least 2 hours post-ablation to evaluate for possible short-term minor or major complications.

2.4. Statistical Analysis:

Descriptive data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables; otherwise, median value and interquartile range (IQR) are shown. To assess the normal distribution of the data we used the Shapiro-Wilk test. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare tumor volume, and serum Tg concentrations before RFA and at the last follow-up visit. The level of significance was defined as p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 24, IBM Corp, SPSS, Chicago, IL).

3. Results

Clinical characteristics and histopathological data of the 8 enrolled patients (6 women/2 men) at baseline are illustrated in

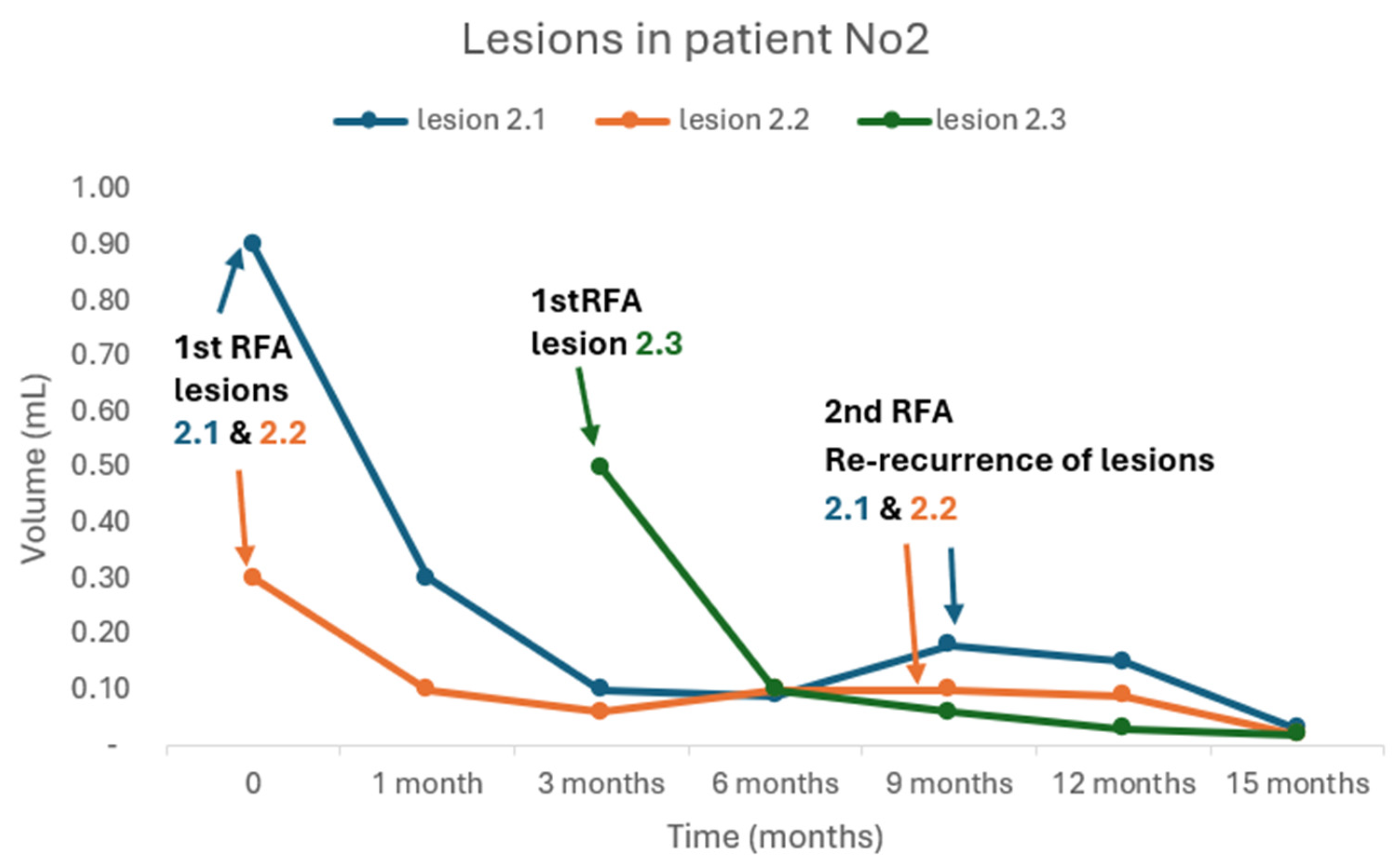

Table 1. Mean age was 39.3 ± 16.4 years (range: 17-69). Median time interval between the last surgery for every patient and the documentation of persistence/recurrence by high-resolution U/S was 22.5 (IQR: 39) months (range: 3 - 66). All patients prior to RFA had undergone one surgery (total thyroidectomy with or without LN dissection according to the presurgical findings as were documented in high-resolution U/S) except for one (patient No2) who had undergone three surgeries due to consecutive locoregional recurrences in the thyroid bed concomitantly with biochemical recurrence, albeit the initial excellent response to treatment (i.e thyroidectomy and RAI ablation with negative imaging in WBS and undetectable Tg levels). It is worth mentioning that the first recurrence of patient No2 was documented 34 months after the first surgery was performed, while the second recurrence was documented 13 months after the first recurrence. Mean number of RAI ablation treatments (RAI-A-T) was 1.5 ± 0.93 (range, 0 – 3); no RAI-A-T in one, one RAI-A-T in three, two RAI-A-T in three, and three RAI-A-T in one patient) with a mean RAI activity of 160 ± 107.97 mCi (range 0 - 300). Two of the patients were diagnosed with aggressive histological variants; patient No2: oncocytic (OCA) widely invasive, patient No3: follicular with trabecular/insular/solid patterns. LN infiltration was already present in five patients at the time of diagnosis.

In total, 14 malignant lesions were ablated by RF. Mean number of ablated lesions per patient was 1.75 ± 0.7 (range: 1 - 3). Four patients were treated for two lesions and three patients were treated for one lesion. One patient (patient No2) was initially treated for two lesions and three months after the first RFA treatment, a new lesion was detected and was treated successfully by a second RFA. Six lesions located in the central (level VI) and eight in the lateral compartments (levels III and IV). Mean largest and smallest lesion diameters were, 10.67 ± 1.99 mm (range: 8 – 13.9) and 5.69 ± 1.68 mm (range: 3.2-9.2), respectively. Median lesion volume was 0.24 mL (IQR: 0.24, range: 0.09 – 0.9). Power used for ablation ranged from 5 to 20 W (median: 10, IQR: 8.75), and the ablation time ranged from 98 to 948 seconds (median: 300, IQR: 254). The energy delivered per mL of pretreatment lesion ranged from 1633.33 to 13542.9 J/mL (mean: 7594.9, SD: 4867.2) and the total energy delivered ranged from 670 J to 40160 J (median: 18410, IQR: 28870). The mean follow-up period from the time the first RFA was performed to the last visit was 13.25 ± 7.5 months (range: 4 - 24).

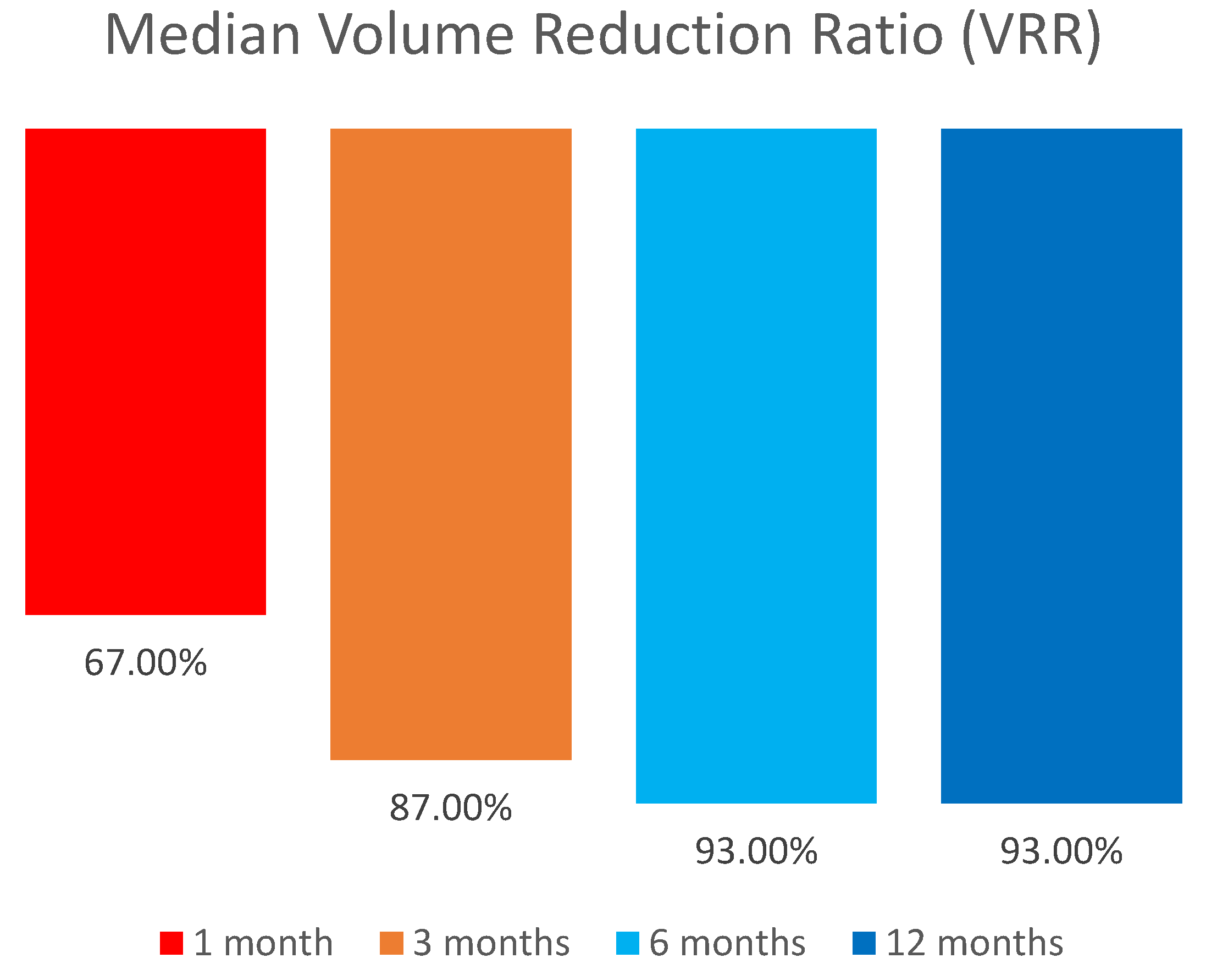

We compared the lesions’ volume reduction after the final RFA. Median volume of the lesions reduced significantly from 0.24 mL (IQR: 0.24, range: 0.09–0.9) to 0.02 (IQR: 0.01, range: 0 - 0.03), (p=0.001) with a median volume reduction ratio (VRR) of 94.5% (IQR: 3.25, range: 78 - 100) (

Table 2 and

Table 3). Median VRR increased from 67% in one month to 93% in 12 months follow-up (

Figure 1). Volume reduction ratio was calculated as:

Out of 14 lesions that were treated, two (14.3%) were no longer visible in the U/S.

All patients underwent a single session of RFA except patient Νο2 who received an additional RFA for a new recurrence. Meanwhile, in the same patient, re-recurrence of the two lesions that were treated with RFA was documented 9 months after the first RFA. Both lesions were re-treated successfully with a second RFA (

Figure 2).

TSH levels in the whole cohort ranged between 0.1 - 0.5 mIU/L throughout the follow-up period, while median Tg levels at baseline were 1.05 ng/mL (IQR: 6.64, range 0.2 - 9.97) and reduced significantly to 0.2 ng/mΛ (IQR: 0.34, range: 0 - 0.5), (p=0.028) at the end of follow up (

Table 2 and

Table 3). Anti-Tg antibodies were negative in all but two patients (No3 and No8); in these two patients anti-Tgs reduced, from 88 times the upper reference limit (URL) to 40 times the URL and from 4.9 times the URL to 3.5 times the URL, respectively. Nevertheless, in patient No3 a rise in AntiTg levels was documented at last follow-up (21 months after first RFA) which was subsequently followed by detection of two new locoregional recurrences (0.24 mL and 0.07 mL) plus two distant metastases measuring up to 9 mm at the left lower lung lobe.

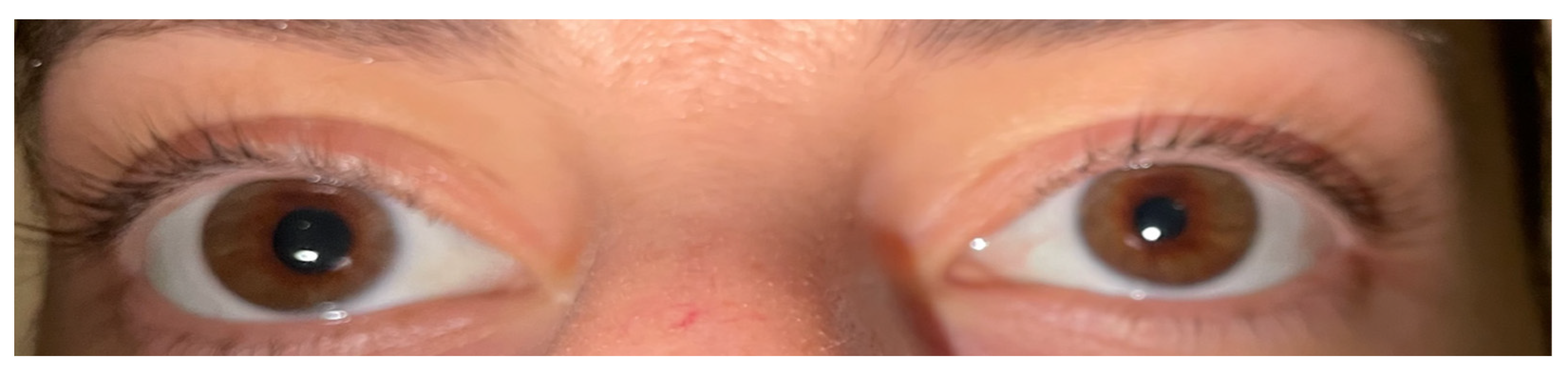

During the treatment, two patients developed Horner syndrome with unilateral myosis, ptosis and anhidrosis as a complication of RFA. The apraclonidine test causing reversal anisocoria was used to establish the diagnosis (

Figure 3) [

43]. Glucocorticoid administration (0.5 mg/kg/d) was initiated for 7 days followed by tapering the dose over 3 days. Complete resolution of the signs and symptoms was documented within 6 months. There were no other significant complications or voice changes except for tolerable pain or burning sensation during the RFA treatment. In general, all the patients tolerated the RFA procedure well.

4. Discussion

WDTC is characterized by an excellent prognosis and no need for long-term follow-up or additional diagnostic and therapeutic interventions are needed in the majority of cases. Nevertheless, SIR (i.e locoregional recurrence or disease persistence) can be encountered in a subgroup of patients, especially when they are diagnosed with an aggressive histology and classified as ATA intermediate and high risk [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Surgery is the standard of care, in cases where the malignant lesion is resectable. RAI ablation may be considered as adjuvant treatment in RAI-avid lesions usually after revision surgery has been performed, albeit it has not shown superiority regarding prognosis and recurrence-free survival, with the ATA-risk classification and histology being the most important prognostic factors of response to treatment [

44,

45]. Similarly, reoperation for SIR has shown inconclusive results with a range of efficacy between 40% and 100%, mainly because of not well-defined criteria for patient selection and determination of a successful surgery; moreover complications from reoperation should be considered in the decision making process [

46]. On the other hand, in cases of smaller or/and iodide refractory local metastases, patient reluctance or inability to undergo revision surgery MIT, like RFA, may be considered [

19,

24]. In the present study we have aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of RFA in a cohort of mainly ATA intermediate risk Caucasian patients who experienced locoregional disease recurrence/persistence.

In our cohort RFA seems to be an efficient MIT achieving a high level of structural response with a median VRR of 94.5%. Interestingly, two lesions of two different patients were no longer visible in the U/S. Accordingly, biochemical remission was documented with a significant decrease in serum Tg and AntiTg levels in all but one patient (patient No3). Our results are supported from a large number of studies in the literature where RFA has been shown to be an effective therapeutic modality in recurrent DTC with a VRR ranging from 53 % to 100 % [

33,

34,

36,

38,

47]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses confirm the safety and effectiveness of the method in reducing the lesion volume and serum Tg levels as well, with some studies reporting complete eradication of the targeted lesions in a percentage of up to 92% after 24 months of follow-up [

32,

48,

49].

Recent studies with extended follow-up support the aforementioned findings, as well. In a Chinese cohort of 32 patients and 58 locoregional recurrent PTC lesions, all but one lesion, had been completely eradicated at the end of the follow-up period which was not earlier than 60 months post-ablation [

37]. In a large retrospective analysis including 119 patients with 172 locoregional recurrent DTC lesions the VRR after RFA was 81.2%, with 72.1% of the lesions completely disappearing after a mean follow-up period of 47.9 months. Lesions characterized by invasion into the airways demonstrated the most unfavorable prognostic outcomes. Nevertheless, even in such cases RFA should be considered as 50% of the lesions invading the trachea were completely eradicated [

50]. It should be noted that RFA may be considered in small and not large malignant lesions, according to the international guidelines and recommendations [

19,

24]. In a Taiwanese cohort of 23 patients with 52 locoregional recurrent DTC lesions, 29 out of 52 lesions (55.8%) had completely disappeared at a follow-up of 6-month period with a mean VRR of 86.6%. Nevertheless, lesions with a maximum diameter exceeding 3.2 cm prior to the RFA, demonstrated the least favorable therapeutic outcomes [

47].

One of our patients (patient No2) experienced a re-recurrance which was successfully treated with a revision of the RFA. Re-recurrences after RFA had also been described in the literature during long-term follow-ups with a revision RFA achieving adequate control of tumor growth [

36,

37]. Especially OCA, previously called “Hürthle cell”, is characterized by locoregional metastases and RAI refractoriness as it is our case. Notably, this patient had experienced local recurrencies twice, before the initial RFA, despite the preceded successful surgeries and adjuvant RAI-A-T with negative post therapy WBS. Tailoring of the monitoring and treatment is of great importance towards the best therapeutic decision in this aggressive type of TC [

51].

In one of our patients (patient No3) two new recurrences were documented at the end of the follow-up period while distant metastases were revealed in 18F-FDG PET-CT scan. This patient was diagnosed with FTC presenting trabecular/insular/solid patterns, histopathological characteristics towards dedifferentiation process and aggressive biological behavior [

9,

15]. This patient had been treated twice with RAI before RFA was performed and no uptake in WBS was documented, even in the thyroid bed, where recurrences were documented by high-resolution U/S. Due to older age (69 years old) and comorbidities the patient preferred RFA instead of surgery. In general, locoregional SIR in ATA intermediate and high risk patients is an independent prognostic factor for progressive metastatic disease [

19,

52]. In such cases it is of great importance to balance the risk/benefit ratio of any therapeutic modality in order to

“first do no harm”. Such patients are candidates for TKIs (Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors) treatment but no sooner than they fulfil the RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours) criteria for disease progression and / or locoregional disease poses a threat for vital structures (i.e trachea). Any kind of locoregional therapies, including RFA, come first to the therapeutic arsenal before initiation of systemic treatment [

19].

Finally, in two of our patients Horner syndrome was diagnosed as a short-term complication of RFA. Horner syndrome is a very rare side effect of RFA described only in a very few case reports of the literature [

53,

54]. It is resolved in a short period of time without leaving any permanent signs or symptoms. It can be rarely present after thyroidectomy or revision surgery for locoregional disease, as well [

55,

56].

Our study has strengths and some limitations. We have included Caucasian patients with both persistent and recurrent disease, followed up for a reasonable period of time; most studies in the literature come from Asia thus it is of value to collect data from a European country and far to our knowledge this is the first study to be published regarding data from Greece. Moreover, we included patients with re-recurrence and new recurrence as well, studying the efficacy and safety of RFA in these cases. Finally, the inclusion of patients with aggressive histology is of great importance as data regarding these patients and appropriate therapeutic management are still gathered. Regarding the limitations, the most obvious is that of the small sample size. This study was further limited by its retrospective design.

5. Conclusion

Despite the small sample size we showed that RFA is an effective and safe therapeutic modality to be considered in selective DTC cases with locoregional SIR (persistent/recurrent disease) achieving a VRR of 94.5% and subsequent biochemical remission. Smaller lesions and DTC cases characterized by increased risk of local re-recurrence (i.e aggressive RAI refractory histological variants) may be considered as candidates for this type of MIT providing that the patient has meticulously been informed about the risk/benefit ratio of all the available therapeutic choices. Additional prospective studies with longer follow-up periods and larger sample size should be performed towards tailored therapeutic approach, especially in more aggressive histological variants of TC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.; methodology, G.S., A.K. and M.G.; software, A.K.; validation, G.S., A.K., R.P. and M.G.; formal analysis, A.K. and R.P; investigation, G.S. and A.K.; resources, G.S, A.K, R.P, P.G, P.K, C.K., M.Z. and M.G.; data curation, G.S, A.K, R.P, P.G, P.K, C.K., M.Z. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, G.S., A.K. and R.P., visualization, G.S. and A.K.; supervision, G.S and M.G..; project administration, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its retrospective nature.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Written informed consent has been obtained only from the patient whose eyes are depicted in

Figure 3.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TC |

Thyroid cancer |

| U/S |

Ultrasound |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| WDTC |

Well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma |

| PTC |

Papillary thyroid carcinoma |

| FTC |

Follicular thyroid carcinoma |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| IEFV |

Invasive encapsulated follicular variant |

| OCA |

Oncocytic carcinoma |

| MTC |

Medullary thyroid carcinoma |

| DHGTC |

Differentiated high grade thyroid carcinoma |

| PDTC |

Poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma |

| ATC |

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma |

| SIR |

Structural incomplete response |

| RAI |

Radioiodine |

| ATA |

American Thyroid Association |

| MIT |

Minimally invasive treatments |

| RFA |

Radiofrequency ablation |

| FNAC |

Fine-needle aspiration cytology |

| Tg |

Thyroglobulin |

| LN |

Lymph node |

| AS |

Active surveillance |

| WBS |

Whole-body scan |

| FDG |

Fludeoxyglucose |

| PET |

Positron emission tomography |

| TSH |

Thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| FT4 |

Free thyroxine |

| Anti-Tgs |

Antithyroglobulin antibodies |

| RIA |

Radioimmunoassay |

| IRMA |

Immunoradiometric Assay |

| D5W |

Dextrose 5% in water |

| E/V |

Energy applied per unit volume |

| SSU |

Short stay unit |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| RAI-A-T |

RAI ablation treatment |

| TNM |

Tumor, node, metastasis |

| VRR |

Volume reduction ratio |

| URL |

Upper reference limit |

| TKI |

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

| RECIST |

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

References

- NIH National Cancer Insitute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer Stat Facts: Thyroid Cancer, 2024.

- Seib, C.D.; Sosa, J.A. Evolving Understanding of the Epidemiology of Thyroid Cancer. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2019, 48, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaccarella, S.; Franceschi, S.; Bray, F.; Wild, C.P.; Plummer, M.; Dal Maso, L. Worldwide Thyroid-Cancer Epidemic? The Increasing Impact of Overdiagnosis. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 614–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Dal Maso, L.; Vaccarella, S. Global Trends in Thyroid Cancer Incidence and the Impact of Overdiagnosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020, 8, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key Statistics for Thyroid Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/thyroid-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Lim, H.; Devesa, S.S.; Sosa, J.A.; Check, D.; Kitahara, C.M. Trends in Thyroid Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA 2017, 317, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagin, J.A.; Wells, S.A. Biologic and Clinical Perspectives on Thyroid Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 1054–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, E. Oncogenesis of Thyroid Cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2017, 18, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhlin, C.C.; Mete, O.; Baloch, Z.W. The 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Tumors: Novel Concepts in Nomenclature and Grading. Endocrine-Related Cancer 2023, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, Z.W.; Asa, S.L.; Barletta, J.A.; Ghossein, R.A.; Juhlin, C.C.; Jung, C.K.; LiVolsi, V.A.; Papotti, M.G.; Sobrinho-Simões, M.; Tallini, G.; et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO Classification of Thyroid Neoplasms. Endocrine Pathology 2022, 33, 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Survival Rates for Thyroid Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/thyroid-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Megwalu, U.C.; Moon, P.K. Thyroid Cancer Incidence and Mortality Trends in the United States: 2000–2018. Thyroid 2022, 32, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, L.E.; Pfeifer, J.D.; Baranski, T.J.; DeWees, T.; Grigsby, P.W. Long-Term Outcomes of Follicular Variant vs Classic Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Endocr Connect 2018, 7, 1226–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, D.; Yuan, A.; Wang, L.; Ranganath, R.; Adilbay, D.; Harries, V.; Patel, S.; Tuttle, M.; Xu, B.; Ghossein, R.; et al. Follicular and Hurthle Cell Carcinoma: Comparison of Clinicopathological Features and Clinical Outcomes. Thyroid 2022, 32, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.-H.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Lu, Y.-L.; Lin, S.-F. Risk Factors and Prognosis for Metastatic Follicular Thyroid Cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.Y.; Won, J.-K.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, D.J.; Jung, K.C.; Sung, M.-W.; Wu, H.-G.; Kim, K.H.; Park, Y.J.; Hah, J.H. Changes of Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Survival Outcomes of Anaplastic and Poorly Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma. Thyroid 2016, 26, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harahap, A.S.; Roren, R.S.; Imtiyaz, S. A Comprehensive Review and Insights into the New Entity of Differentiated High-Grade Thyroid Carcinoma. Curr Oncol 2024, 31, 3311–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bible, K.C.; Kebebew, E.; Brierley, J.; Brito, J.P.; Cabanillas, M.E.; Clark, T.J.; Di Cristofano, A.; Foote, R.; Giordano, T.; Kasperbauer, J.; et al. 2021 American Thyroid Association Guidelines for Management of Patients with Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2021, 31, 337–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, B.R.; Alexander, E.K.; Bible, K.C.; Doherty, G.M.; Mandel, S.J.; Nikiforov, Y.E.; Pacini, F.; Randolph, G.W.; Sawka, A.M.; Schlumberger, M.; et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 2016, 26, 1–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filetti, S.; Durante, C.; Hartl, D.; Leboulleux, S.; Locati, L.D.; Newbold, K.; Papotti, M.G.; Berruti, A. Thyroid Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Annals of Oncology 2019, 30, 1856–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, R.I.; Bischoff, L.; Ball, D.; Bernet, V.; Blomain, E.; Busaidy, N.L.; Campbell, M.; Dickson, P.; Duh, Q.; Ehya, H.; et al. Thyroid Carcinoma, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2022, 20, 925–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, F.; Fuhrer, D.; Elisei, R.; Handkiewicz-Junak, D.; Leboulleux, S.; Luster, M.; Schlumberger, M.; Smit, J.W. 2022 ETA Consensus Statement: What Are the Indications for Post-Surgical Radioiodine Therapy in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer? Eur Thyroid J 2021, 11, e210046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapuppo, G.; Tavarelli, M.; Belfiore, A.; Vigneri, R.; Pellegriti, G. Time to Separate Persistent from Recurrent Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: Different Conditions with Different Outcomes. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2018, 104, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, G.; Hegedüs, L.; Bandula, S.; Cazzato, R.L.; Czarniecka, A.; Dudeck, O.; Fugazzola, L.; Netea-Maier, R.; Russ, G.; Wallin, G.; et al. European Thyroid Association and Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Use of Minimally Invasive Treatments in Malignant Thyroid Lesions. European Thyroid Journal 2021, 10, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalheiro, B.G.; Shah, J.P.; Randolph, G.W.; Medina, J.E.; Tufano, R.P.; Zafereo, M.; Hartl, D.M.; Nixon, I.J.; Guntinas-Lichius, O.; Vander Poorten, V.; et al. Management of Recurrent Well-Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma in the Neck: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2023, 15, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasim, S.; Patel, K.N.; Randolph, G.; Adams, S.; Cesareo, R.; Condon, E.; Henrichsen, T.; Itani, M.; Papaleontiou, M.; Rangel, L.; et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Disease State Clinical Review: The Clinical Utility of Minimally Invasive Interventional Procedures in the Management of Benign and Malignant Thyroid Lesions. Endocrine Practice 2022, 28, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malandrino, P.; Latina, A.; Marescalco, S.; Spadaro, A.; Regalbuto, C.; Fulco, R.A.; Scollo, C.; Vigneri, R.; Pellegriti, G. Risk-Adapted Management of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Assessed by a Sensitive Measurement of Basal Serum Thyroglobulin. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2011, 96, 1703–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufano, R.P.; Clayman, G.; Heller, K.S.; Inabnet, W.B.; Kebebew, E.; Shaha, A.; Steward, D.L.; Tuttle, R.M. Management of Recurrent/Persistent Nodal Disease in Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: A Critical Review of the Risks and Benefits of Surgical Intervention Versus Active Surveillance. Thyroid 2015, 25, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orloff, L.A.; Noel, J.E.; Stack, B.C.; Russell, M.D.; Angelos, P.; Baek, J.H.; Brumund, K.T.; Chiang, F.Y.; Cunnane, M.B.; Davies, L.; et al. Radiofrequency Ablation and Related Ultrasound-Guided Ablation Technologies for Treatment of Benign and Malignant Thyroid Disease: An International Multidisciplinary Consensus Statement of the American Head and Neck Society Endocrine Surgery Section with the Asia Pacific Society of Thyroid Surgery, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons, European Thyroid Association, Italian Society of Endocrine Surgery Units, Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology, Head & Neck 2022, 44, 633–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, D.E.; Monchik, J.M.; Decrea, C.; Pisharodi, L. Radiofrequency Ablation of Regional Recurrence from Well-Differentiated Thyroid Malignancy. Surgery 2001, 130, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, S.P.J.; Coerts, H.I.; Gunput, S.T.G.; van Velsen, E.F.S.; Medici, M.; Moelker, A.; Peeters, R.P.; Verhoef, C.; van Ginhoven, T.M. Assessment of Radiofrequency Ablation for Papillary Microcarcinoma of the Thyroid: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2022, 148, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Tian, G.; Kong, D.; Jiang, T. Meta-Analysis of Radiofrequency Ablation for Treating the Local Recurrence of Thyroid Cancers. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 2016, 39, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegeni, H.; Ebrahiminik, H.; Mosadegh Khah, A.; Malekzadeh, H.; Abbasi, M.; Molooghi, K.; Fadaee, N.; Kargar, J. Ultrasound-Guided Radiofrequency Ablation of Locally Recurrent Thyroid Carcinoma. CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology 2022, 45, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Aljammal, J.; Orozco, I.; Raashid, S.; Zulfiqar, F.; Nikravan, S.P.; Hussain, I. Radiofrequency Ablation of Cervical Thyroid Cancer Metastases—Experience of Endocrinology Practices in the United States. Journal of the Endocrine Society 2023, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Baek, J.H.; Lim, H.K.; Ahn, H.S.; Baek, S.M.; Choi, Y.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Chung, S.R.; Ha, E.J.; Hahn, S.Y.; et al. 2017 Thyroid Radiofrequency Ablation Guideline: Korean Society of Thyroid Radiology. Korean Journal of Radiology 2018, 19, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.R.; Baek, J.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, J.H. Ten-Year Outcomes of Radiofrequency Ablation for Locally Recurrent Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Korean Journal of Radiology 2024, 25, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yan, L.; Xiao, J.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Luo, Y. Long-Term Results of Radiofrequency Ablation for Locally Recurrent Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. International Journal of Hyperthermia 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, J. Efficacy and Safety of Percutaneous Ultrasound Guided Radiofrequency Ablation for Treating Cervical Metastatic Lymph Nodes from Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2017, 143, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, C.H.; Baek, J.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, J.H. Efficacy and Safety of Radiofrequency and Ethanol Ablation for Treating Locally Recurrent Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thyroid 2016, 26, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.R.; Suh, C.H.; Baek, J.H.; Park, H.S.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, J.H. Safety of Radiofrequency Ablation of Benign Thyroid Nodules and Recurrent Thyroid Cancers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Hyperthermia 2017, 33, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.E.; Baek, J.H.; Lee, J.H. Radiofrequency and Ethanol Ablation for the Treatment of Recurrent Thyroid Cancers. Current Opinion in Oncology 2013, 25, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.H.; Baek, J.H.; Ha, E.J.; Lee, J.H. Radiofrequency Ablation of Thyroid Nodules: Basic Principles and Clinical Application. International Journal of Endocrinology 2012, 2012, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, F. Apraclonidine Is Better Than Cocaine for Detection of Horner Syndrome. Front Neurol 2019, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvet, C.; Barres, B.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Batisse-Lignier, M.; Chafai El Alaoui, M.; Kauffmann, P.; Cachin, F.; Tauveron, I.; Kelly, A.; Maqdasy, S. Re-Treatment With Adjuvant Radioactive Iodine Does Not Improve Recurrence-Free Survival of Patients With Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadena-Piñeros, E.; Escobar, J.V.; Carreño, J.A.; Rojas, J.G. Second Adjuvant Radioiodine Therapy after Reoperation for Locoregionally Persistent or Recurrent Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. World J Nucl Med 2022, 21, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamartina, L.; Borget, I.; Mirghani, H.; Al Ghuzlan, A.; Berdelou, A.; Bidault, F.; Deandreis, D.; Baudin, E.; Travagli, J.-P.; Schlumberger, M.; et al. Surgery for Neck Recurrence of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: Outcomes and Risk Factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017, 102, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.C.; Chou, C.K.; Chang, Y.H.; Chiang, P.L.; Lim, L.S.; Chi, S.Y.; Luo, S.D.; Lin, W.C. Efficacy of Radiofrequency Ablation for Metastatic Papillary Thyroid Cancer with and without Initial Biochemical Complete Status. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, C.H.; Baek, J.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, J.H. Efficacy and Safety of Radiofrequency and Ethanol Ablation for Treating Locally Recurrent Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thyroid 2016, 26, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Yan, L.; Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, Y. Value of Radiofrequency Ablation for Treating Locally Recurrent Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis for 2-Year Follow-Up. Endocrine 2024, 85, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.R.; Baek, J.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Sung, T.-Y.; Song, D.E.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, J.H. Efficacy of Radiofrequency Ablation for Recurrent Thyroid Cancer Invading the Airways. European Radiology 2021, 31, 2153–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, L.A.; Ganly, I.; Fugazzola, L.; Buczek, E.; Faquin, W.C.; Haugen, B.R.; McIver, B.; McMullen, C.P.; Newbold, K.; Rocke, D.J.; et al. Molecular Alterations and Comprehensive Clinical Management of Oncocytic Thyroid Carcinoma: A Review and Multidisciplinary 2023 Update. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2024, 150, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamartina, L.; Grani, G.; Durante, C.; Borget, I.; Filetti, S.; Schlumberger, M. Follow-up of Differentiated Thyroid Cancer - What Should (and What Should Not) Be Done. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018, 14, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, W.B.; Sung, T.Y.; Baek, J.H. Complications Encountered in Ultrasonography-Guided Radiofrequency Ablation of Benign Thyroid Nodules and Recurrent Thyroid Cancers. European Radiology 2017, 27, 3128–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, T.D.; Saputri, K.M.; Purwanto, D.J. Second Order Horner Syndrome Concurrent with Brachial Plexus Injury Following Thyroid Radiofrequency Ablation: A Case Report. Acta Neurologica Indonesia 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsote, M.; Nistor, C.-E.; Popa, F.L.; Stanciu, M. Horner’s Syndrome and Lymphocele Following Thyroid Surgery. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2023, 12, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; Gan, H.; Yu, D.; Sun, W.; Shi, Z. Horner Syndrome as a Postoperative Complication after Minimally Invasive Video-Assisted Thyroidectomy: A Case Report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017, 96, e8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).