Submitted:

23 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

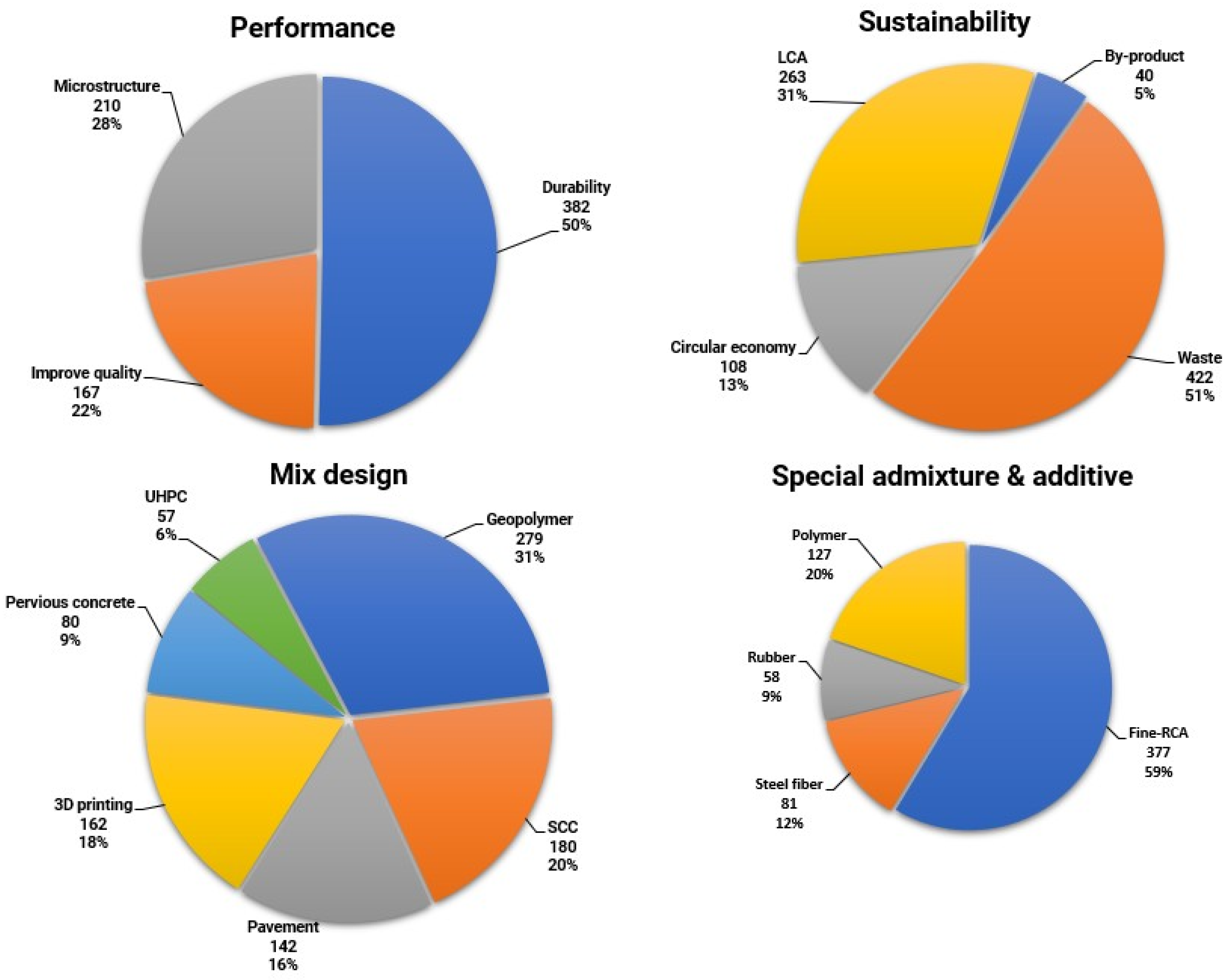

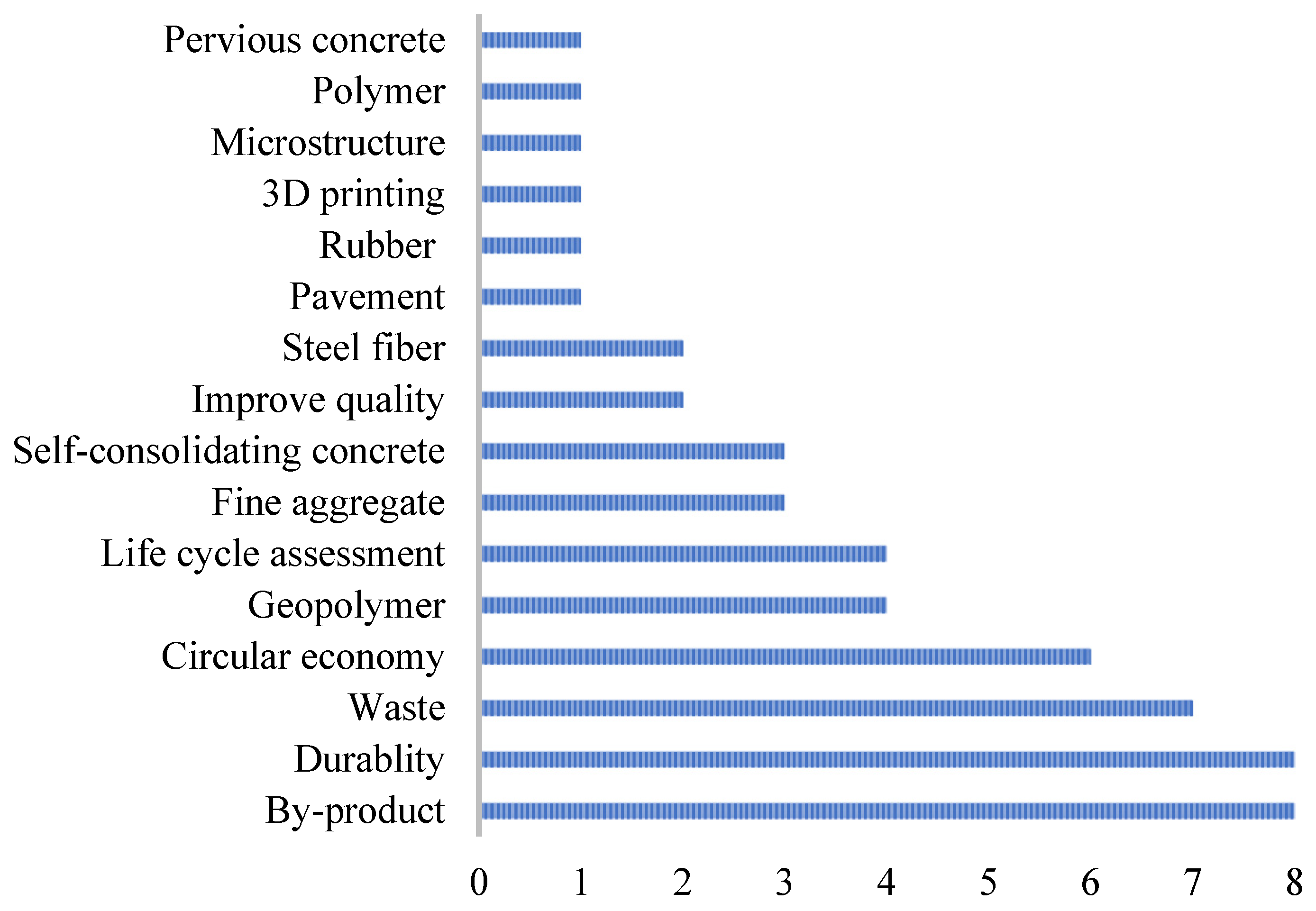

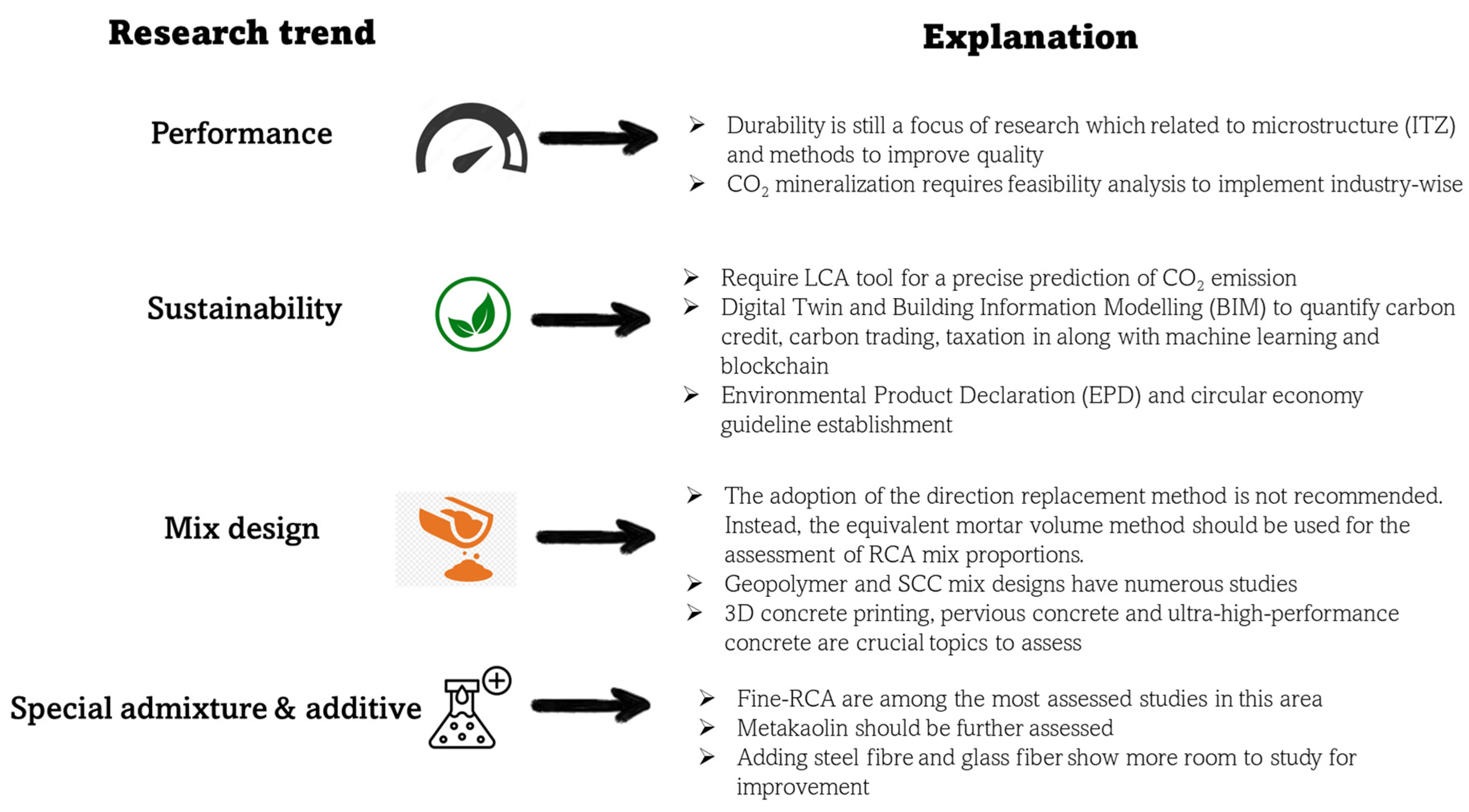

1.1. Scope of the Review Paper

1.2. Significance of the Review

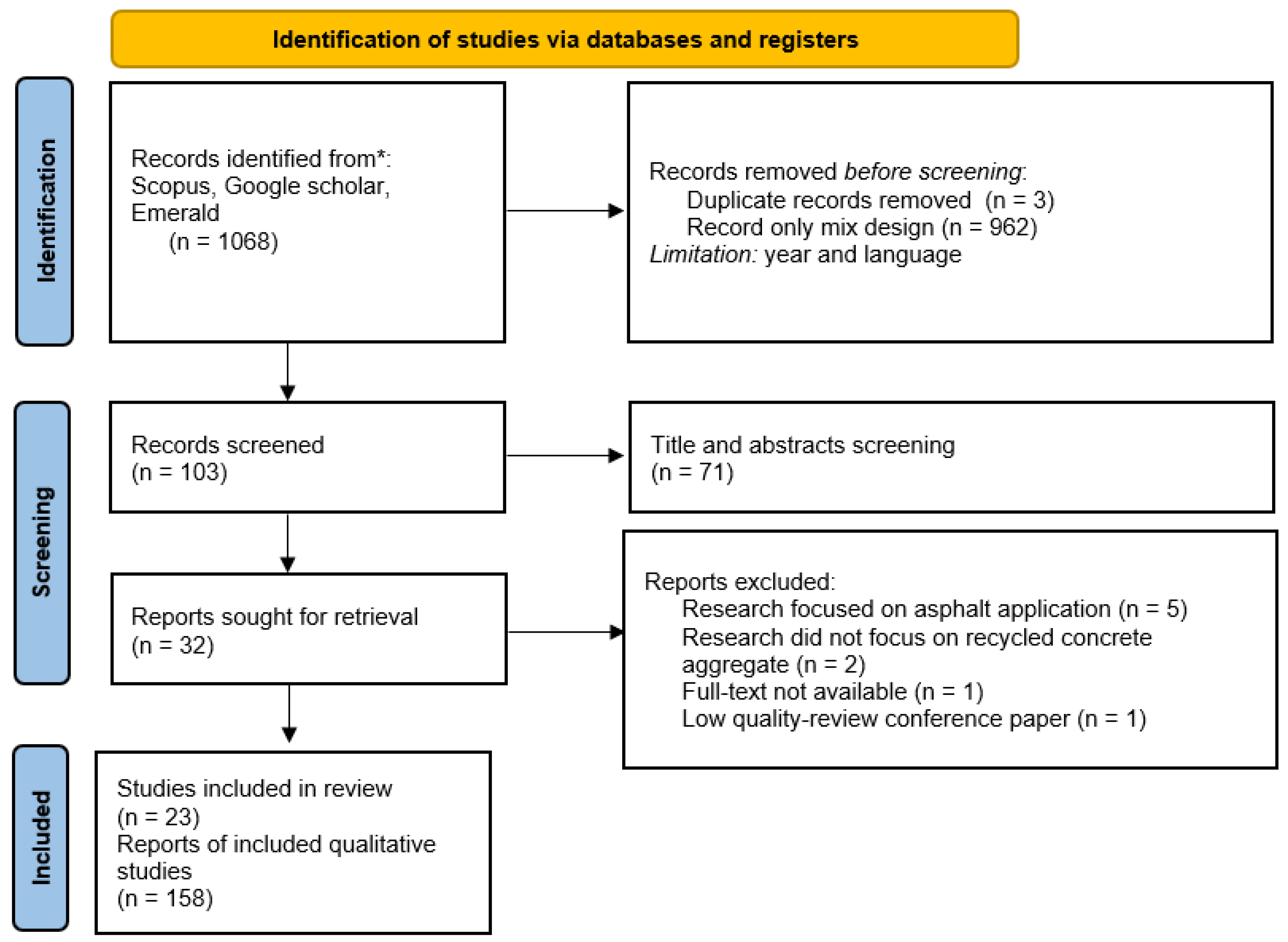

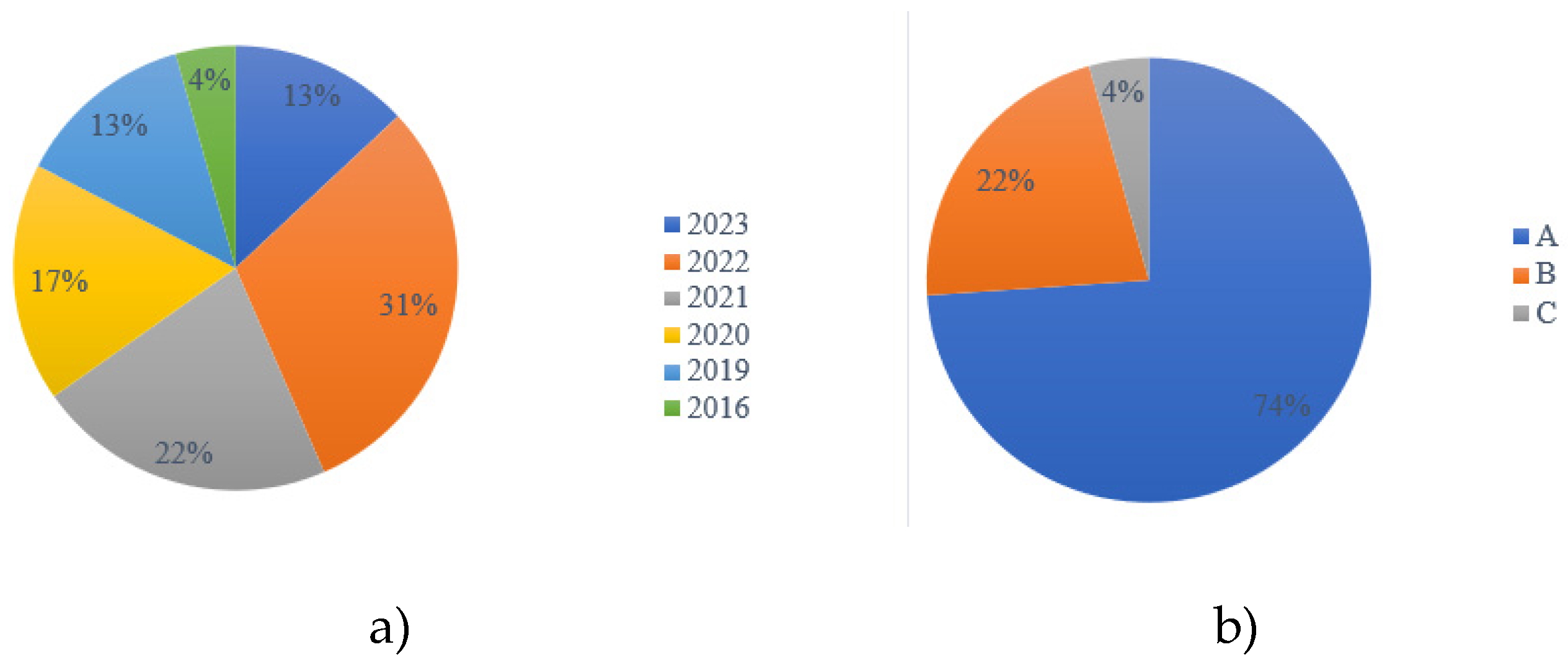

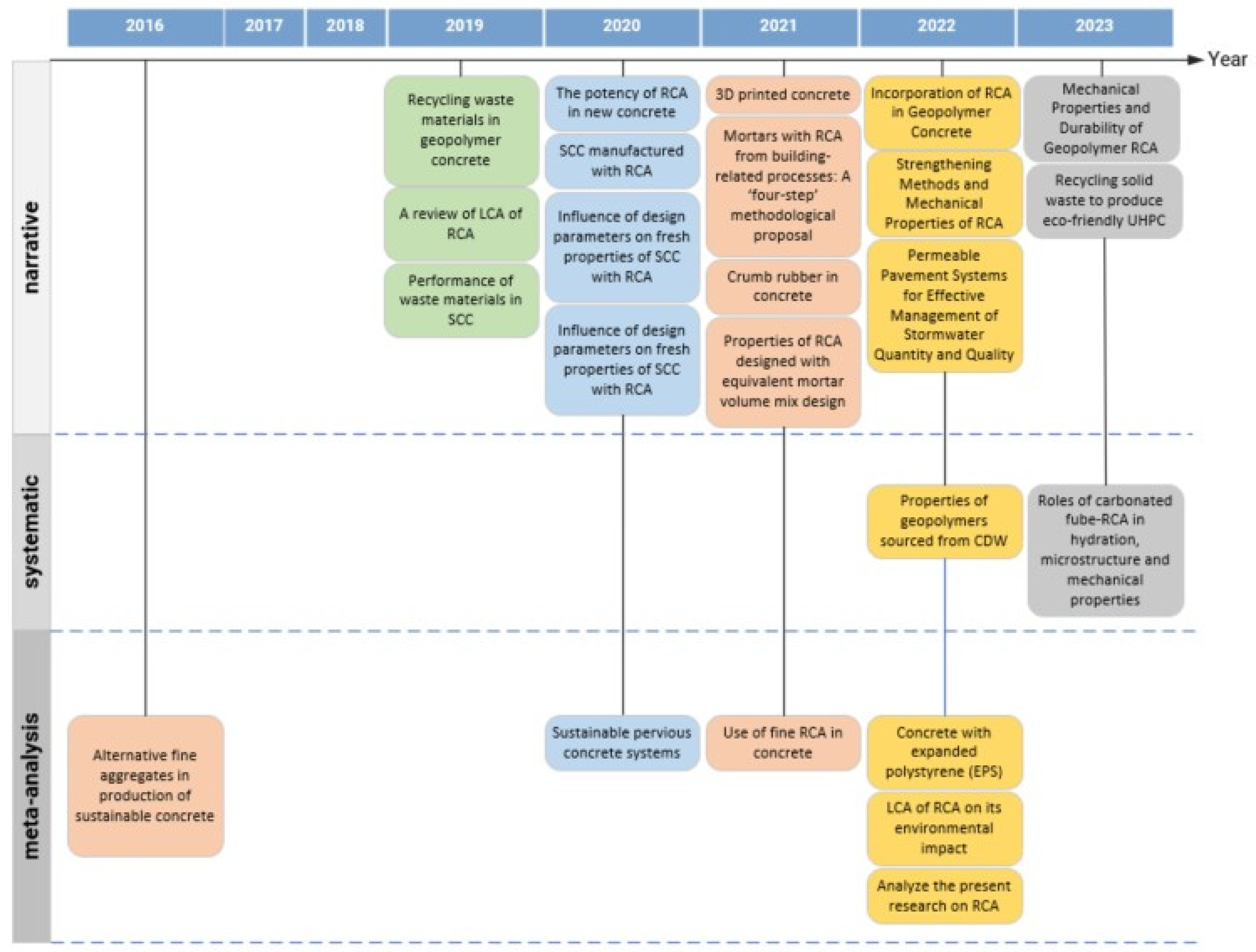

2. Methodology

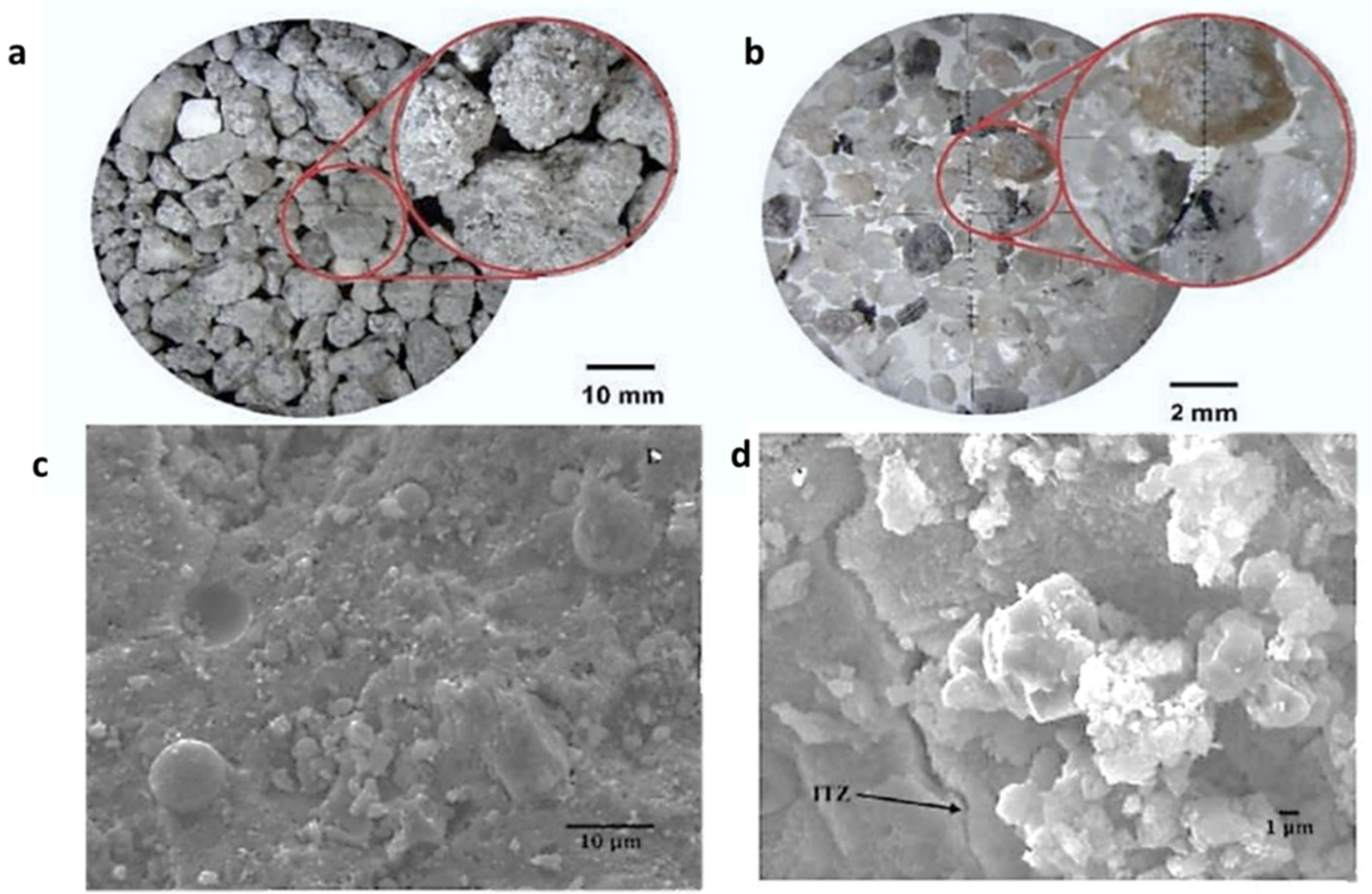

3. RCA

3.1. Definition of RCA

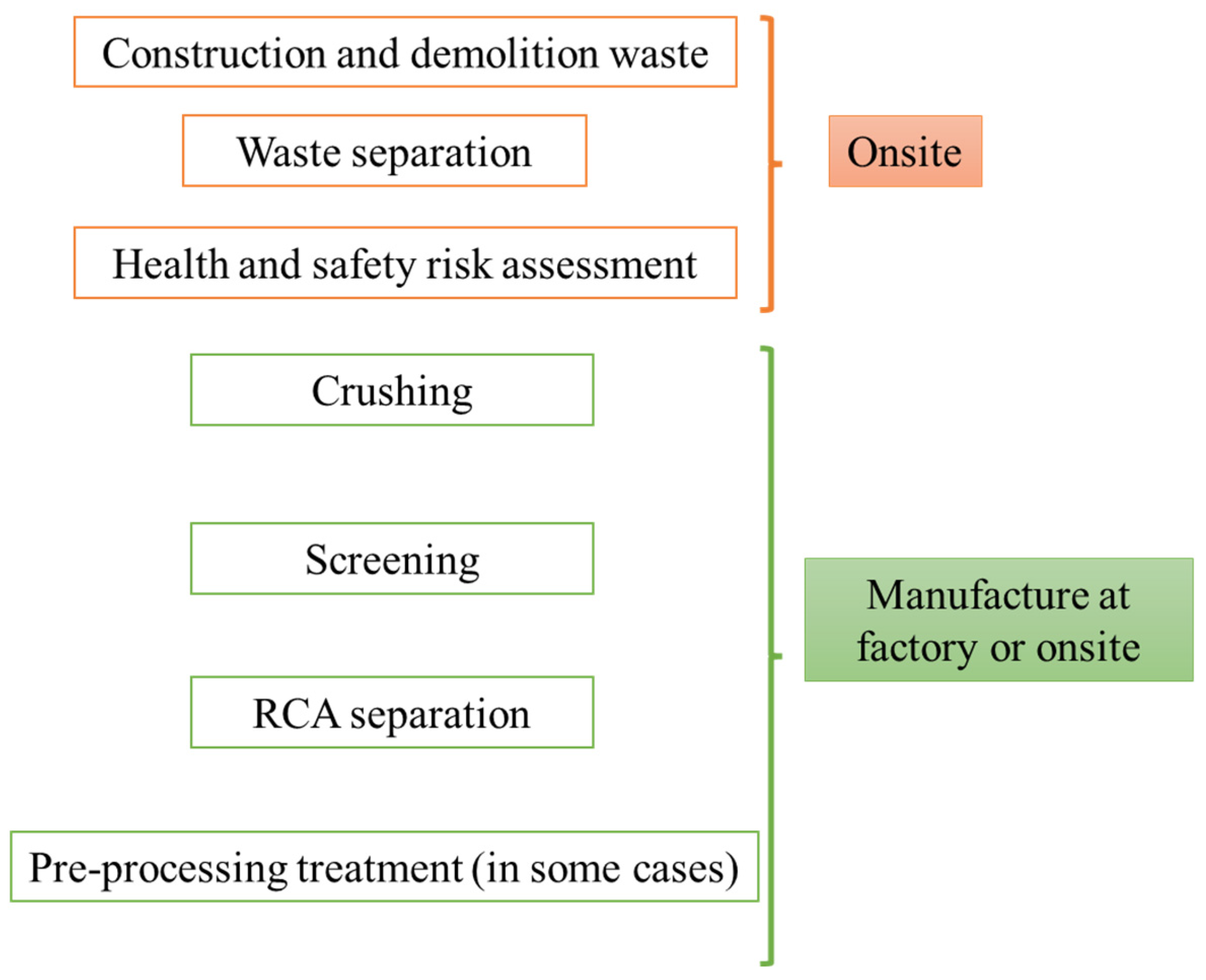

3.2. Production Process of RCA

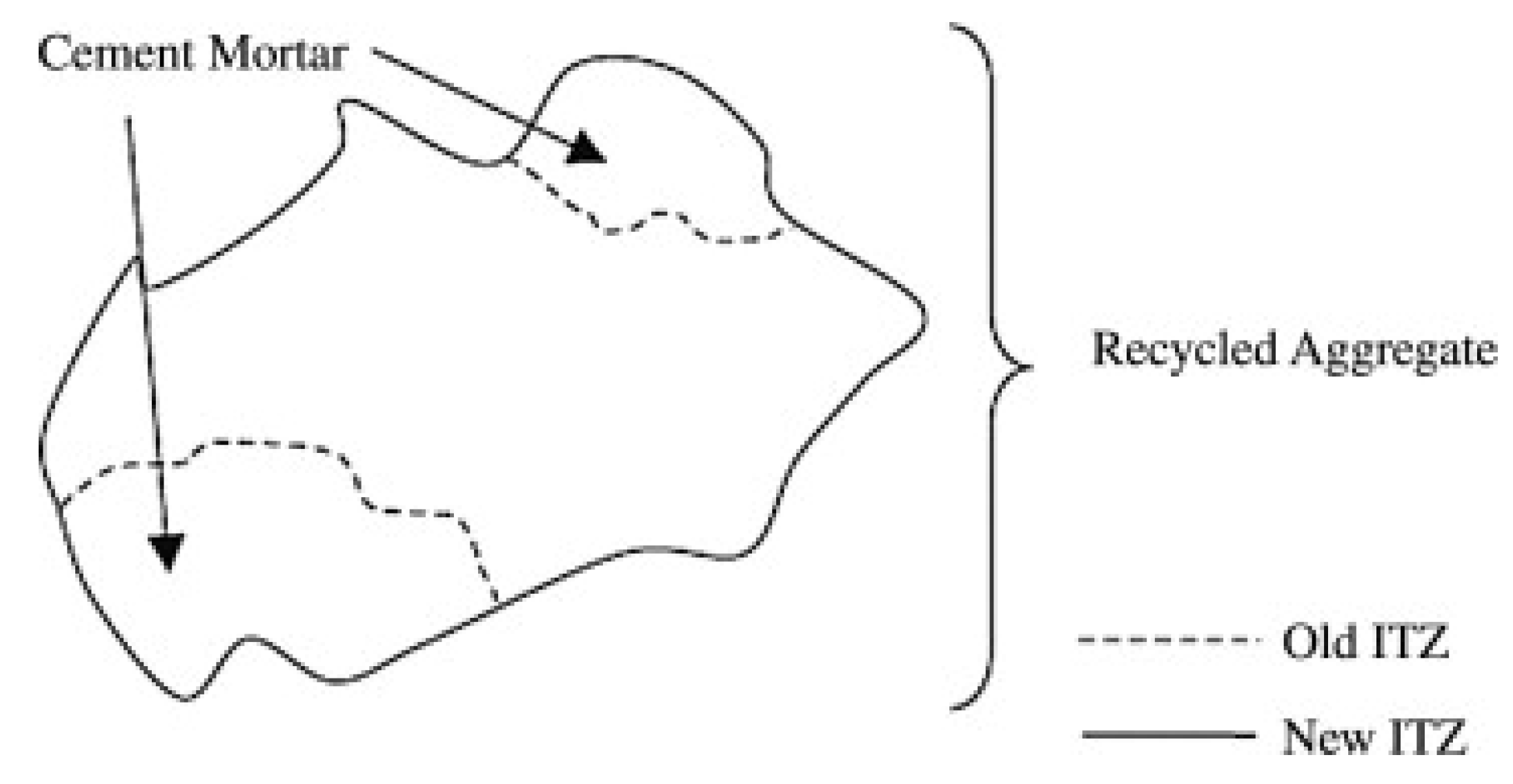

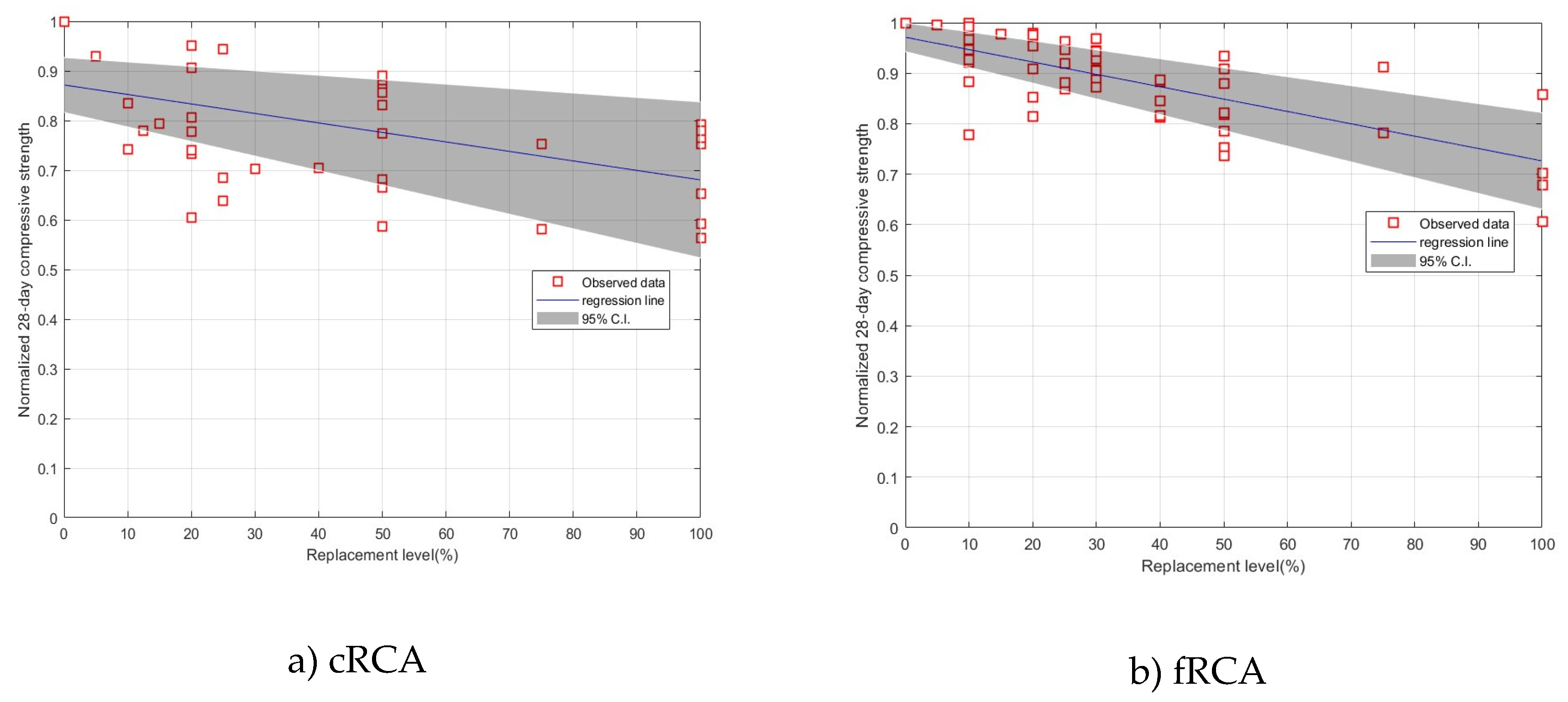

3.3. Mechanical Properties of RCA

4. Mix Proportions

4.1. General Mix Design

4.2. RCA Concrete with By-Products

4.3. Wastes

4.4. Fine-RCA

4.5. Geopolymer

4.6. Self-Consolidating Concrete

4.7. Other Mix Designs with RCA for 3D Concrete Printing, Pervious Concrete and Ultra-High-Performance Concrete

5. Performance Aspect

5.1. Durability

5.2. Methods to Improve RCA Quality and Reliability

6. Environmental Impact Aspect

6.1. Life Cycle Assessment

6.2. Circular Economy

8. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RCA | recycle concrete aggregate |

| CDW | construction and demolition waste |

| NA | natural aggregate |

| EPA | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

| cRCA | coarse recycle concrete aggregate |

| fRCA | fine recycle concrete aggregate |

| OPC | Ordinary Portland Cement |

| SF | silica fume |

| SCC | self-consolidating concrete |

| 3DCP | 3D concrete printing |

| UHPC | ultra-high-performance concrete |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| ITZ | interfacial transition zone |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| SCM | supplementary cementing material |

| FA | fly ash |

| BA | bottom ash |

| MK | metakaolin |

| RHA | rice husk ash |

| EPS | expanded polystyrene |

| PU | polyurethane |

| PET | polyethylene terephthalate |

| ECO2 | embodied CO2 |

| BIM | Building Information Modelling |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declarations |

| FIB | International Federation for Structural Concrete |

Appendix A. Baseline Characteristics of Reviews Assessing Concrete Mix Design Containing RCA

| Authors | Title | Source title | Outcome | Suggestion | Future research |

| Hamada et al. | Recycling solid waste to produce eco-friendly ultra-high-performance concrete: A review of durability, microstructure and environment characteristics | Science of the Total Environment | Typical UHPC generated high carbon and consume natural resources | Internal curing, filling, pozzolan can used to reduce large ITZ and microcracks from RCA | Performance in aggressive environments, design methods and testing standards |

| Zhang et al. | Mechanical Properties and Durability of Geopolymer Recycled Aggregate Concrete: A Review | Polymers | Better quality of RCA geopolymer can be made by changing the curing temperature, using different precursor materials, adding fibers and nanoparticles, and setting optimal mix ratios | Use several ingredients in geopolymer is better than using one added ingredient | Treatment for removing mortar, effects from adding MK, regulation establishment |

| Zhang et al. | Roles of carbonated recycled fines and aggregates in hydration, microstructure and mechanical properties of concrete: A critical review | Cement and Concrete Composites | Through physical interlocking and chemical bonding, carbonated recycled aggregates improve concrete's interfacial transition zone micromechanical characteristics. | RCA concrete varies from region to region and thus reasonable transportation network and high-efficient carbonation process are essential | low-carbon concrete with recycled concrete as a carbon sink |

| Singer et al. | Permeable Pavement Systems for Effective Management of Stormwater Quantity and Quality: A Bibliometric Analysis and Highlights of Recent Advancements | Sustainability (Switzerland) | Innovative permeable pavement Systems using recycled aggregates have good mechanical and hydrologic qualities and were more sustainable. | Lack of models to predict their long-term performance. | Incorporate both model and experimental simulations to simulate field experiments |

| Liu et al. | Review of the Strengthening Methods and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete (RAC) | Crystals | Performance was improved by adding superplasticizer and SF | Each RAC mix design method has advantages such that consensus between methodologies and standardized RAC mix design would be helpful | Shotcrete containing RCA and its alkali-aggregate reaction |

| Nikmehr et al. | A State-of-the-Art Review on the Incorporation of Recycled Concrete Aggregates in Geopolymer Concrete | Recycling | RCA derived from concrete lab specimens, CDW landfilled, and demolished buildings. Specific gravity, density, dry density, saturated density, bulk density, and apparent density of RCA are less than NA | Alumina silicates like slag and MK, the Na2SiO3/NaOH ratio, and the alkali-activator-to-binder ratio improve hardened geopolymer concrete. However, increasing the ratios reduce its workability. | SCC, effect of RCA on their compressive strength, optimum amount of their mix components |

| Alhawat et al. | Properties of geopolymers sourced from construction and demolition waste: A review | Journal of Building Engineering | Due to the many geopolymer mix design characteristics, trial-and-error is still the most typical method. | fRCA, notably those under 75 μm, have higher compressive strengths, and thermal curing at 60–90 °C improves mechanical performance and durability. | possibility of efflorescence formation or formation of salt on the surface of concrete |

| Zhang et al. | A scientometric analysis approach to analyze the present research on recycled aggregate concrete | Journal of Building Engineering | RCA concrete has inferior mechanical and durability performance than normal concrete. Improvements methods can improve RCA concrete: mixing process modification, pre-coating and adding admixtures | Due to its poor mechanical and durability features, high improving process costs, and lack of standards for RCA processing, manufacture, and mix design, RCA concrete is yet not suitable for large-scale applications. | Large-scale production and applications and economic viability |

| Xing et al. | Life cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete on its environmental impacts: A critical review | Construction and Building Materials | Numerous inconsistencies and uncertainties existing in LCA processes that avoid LCA results from comparisons | Cement manufacture dominates concrete's environmental impact, followed by mix design and raw material treatment technique. LCA phase selections, system boundary, allocation rule, LCI, and LCIA methodology are subjective, creating further ambiguities that prevent study comparisons. | Mix design modifications and LCA procedure inconsistencies might create a holistic and multi-criteria study for comparison. |

| Prasittisopin et al. | Review of concrete with expanded polystyrene (EPS): Performance and environmental aspects | Journal of Cleaner Production | Many product types such as concrete brick, lightweight masonry mortar, rendering mortar, SCC, and gypsum-based materials can be added | Cement-based systems with polymers are currently considered unsustainable. The polymer releases hazardous gas during combustion. | Data-driven techniques and additive manufacturing |

| Kim | Properties of recycled aggregate concrete designed with equivalent mortar volume mix design | Construction and Building Materials | Adoption of the equivalent mortar volume method leads to savings in raw materials. | Environmental pollution can be mitigated with the equivalent mortar volume mix design | Accurately measuring adhered mortar content from RCA |

| Kara De Maeijer et al. | Crumb rubber in concrete—the barriers for application in the construction industry | Infrastructures | Concrete has high dampness ratio, which is suitable for railway sleepers, seismic-prone constructions, concrete columns and bridges due to its vibration absorption and moisture absorption. | Barriers of utilizing RCA rubber (1) the cost of rubber recycling, (2) mechanical properties reduction, (3) insufficient research about leaching criteria and ecotoxicological risks and (4) recyclability of rubber | Study the cost-effectiveness of various surface treatment procedures. |

| Nedeljkovic et al. | Use of fine recycled concrete aggregates in concrete: A critical review | Journal of Building Engineering | Challenged properties of fRCA are identified as their high-water absorption, moisture state, agglomeration of particles and adhered mortar. | More continuity in terms of chemistry | Concrete mix design must account for fRCA's limiting features using advanced characterisation and concrete technology methods. |

| Vitale et al. | Mortars with recycled aggregates from building-related processes: A ‘four-step’ methodological proposal for a review | Sustainability (Switzerland) | Mortars were mostly characterized by their physical and mechanical properties, with limited durability and thermal evaluations. | Lack of confidence in RCA, a survey could be conducted involving the main stakeholders of the building process—designers, end customers, construction companies, and producers—to investigate, by questionnaire, opinions, confidence, and difference about waste reuse. | Distinguishment of RCA types best for rendering mortars or lighter applications. |

| Hou et al. | A review of 3D printed concrete: Performance requirements, testing measurements and mix design | Construction and Building Materials | Recycled sand can be applied in 3DCP to improve its performance | Recycled sand significantly affected early mechanical behavior. Green strength and buildability increased while open time decreased. | Recycled materials need to be considered in their mix design |

| Martínez-García et al. | Influence of design parameters on fresh properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled aggregate—a review | Materials | SCC with RCA has good structural qualities according to EFNRARC criteria. | RCA would improve concrete manufacturing sustainability and benefit construction and the CE. | Its qualities and the creation of RA concrete guidelines and standards |

| Singh et al. | A review of sustainable pervious concrete systems: Emphasis on clogging, material characterization, and environmental aspects | Construction and Building Materials | Full replacement of NA with RA increased waste recycling to 73% by volume and decreased carbon emissions by 24%. | Permeability depended more on portland cement mix porosity than aggregate type. | Their long-term performance evaluation |

| Revilla-Cuesta et al. | Self-compacting concrete manufactured with recycled concrete aggregate: An overview | Journal of Cleaner Production | RCA may make a good SCC using meticulous designs for optimal performance. | The higher amount of RCA implies higher dispersion in the hardened performance. | combination of SCC and RCA is still needed |

| Kirthika et al. | Alternative fine aggregates in production of sustainable concrete- A review | Journal of Cleaner Production | Concrete with RCA increases economic, sustainability, and social benefits. | Mineral admixtures including FA, SF, micro silica, MK, and others improve concrete mechanics and durability regardless of alternative fine aggregate type. | Environmental imbalance, waste management, and fRCA should be aware. Needs to gather experimental data and create guidelines/codes, policies |

| Anike et al. | The potency of recycled aggregate in new concrete: a review | Construction Innovation | RCA contributes less strength than NA. RA's mortar increases water absorption and lowers density compared to NA's. | Controlled RCA quantity, mixing and proportioning procedures, admixtures, and strengthening ingredients like steel fibres can improve their mechanical and durability. | Construct a mix design for RAC that incorporates all RA traits like correct gradation. |

| Zhang et al. | A review of life cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete | Construction and Building Materials | LCA issues include mixture design approach, functional unit selection, inventory allocation, CO2 uptake, and recycled aggregate transport distance. | When comparing concrete with NA and RCA environmental impact, distance from transportation can be a key factor | Investigate an allocation approach that combines quality, mass, and market pricing. |

| Mohajerani et al. | Recycling waste materials in geopolymer concrete | Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy | Geopolymeric binders are stronger due to their chemical matrix than aggregate interaction. | Potassium silicate solutions are more user-friendly and thus better for industry uptake. | Extremely changeable character of waste materials and mix designs that use locally avail |

| Ismail et al. | A review on performance of waste materials in self-compacting concrete (SCC) | Jurnal Teknologi | RCA increases water absorption and decreases compressive strength in SCC. | Fresh and hardened SCC should match. | Exploring design efficiency, practicability, and economic worth |

References

- Mies, A.; Gold, S. Mapping the social dimension of the circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 321, 128960. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Sovacool, B.K.; Bazilian, M.; Griffiths, S.; Lee, J.; Yang, M.; Lee, J. Decarbonizing the iron and steel industry: A systematic review of sociotechnical systems, technological innovations, and policy options. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Vasilakopoulou, K. Present and future energy consumption of buildings: Challenges and opportunities towards decarbonisation. e-Prime-Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy 2021, 1, 100002. [CrossRef]

- Alhawat, M.; Ashour, A.; Yildirim, G.; Aldemir, A.; Sahmaran, M. Properties of geopolymers sourced from construction and demolition waste: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Msigwa, G.; Osman, A.I.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.-S. Circular economy strategies for combating climate change and other environmental issues. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 21, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Reimagining our buildings and spaces for a circular economy. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/built-environment/overview (accessed on 31 Mar).

- Hinton-Beales, D. EU circular economy could create two million jobs by 2030. Available online: https://www.theparliamentmagazine.eu/news/article/eu-circular-economy-could-create-two-million-jobs-by-2030#:~:text=The%20commission%20has%20calculated%20that,economy%20also%20strengthens%20our%20security. (accessed on 31 Mar).

- The Royal BAM Group. Circularity. Available online: https://www.bam.com/en/sustainability/circularity (accessed on 31 Mar).

- Salmenperä, H.; Pitkänen, K.; Kautto, P.; Saikku, L. Critical factors for enhancing the circular economy in waste management. Journal of cleaner production 2021, 280, 124339. [CrossRef]

- Turkyilmaz, A.; Guney, M.; Karaca, F.; Bagdatkyzy, Z.; Sandybayeva, A.; Sirenova, G. A comprehensive construction and demolition waste management model using PESTEL and 3R for construction companies operating in Central Asia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1593. [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, S.; Lavagna, M.; Campioli, A. Guidelines for effective and sustainable recycling of construction and demolition waste. Designing sustainable technologies, products and policies: From science to innovation 2018, 211-221.

- Asgari, A.; Ghorbanian, T.; Yousefi, N.; Dadashzadeh, D.; Khalili, F.; Bagheri, A.; Raei, M.; Mahvi, A.H. Quality and quantity of construction and demolition waste in Tehran. J. Environ. Heal. Sci. Eng. 2017, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsworthy, K. Design for Cyclability: pro-active approaches for maximising material recovery. Making Futures 2014, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Duangmanee, V.; Tuprakay, S.; Kongsong, W.; Prasittisopin, L.; Charoenrien, S. Influencing Factors in Production and Use of Recycle Concrete Aggregates (RCA) in Thailand. J. Inform. Technol. Manag. Innov 2018, 5, 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Kittinaraporn, W.; Tuprakay, S.; Prasittisopin, L. Effective Modeling for Construction Activities of Recycled Aggregate Concrete Using Artificial Neural Network. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2022, 148, 04021206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wang, X.; Kua, H.; Geng, Y.; Bleischwitz, R.; Ren, J. Construction and demolition waste management in China through the 3R principle. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez, P.V.; Osmani, M. A diagnosis of construction and demolition waste generation and recovery practice in the European Union. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Martos, J.-L.; Styles, D.; Schoenberger, H.; Zeschmar-Lahl, B. Construction and demolition waste best management practice in Europe. Resources, conservation and recycling 2018, 136, 166–178. [CrossRef]

- Purchase, C.K.; Al Zulayq, D.M.; O’Brien, B.T.; Kowalewski, M.J.; Berenjian, A.; Tarighaleslami, A.H.; Seifan, M. Circular economy of construction and demolition waste: A literature review on lessons, challenges, and benefits. Materials 2022, 15, 76. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Grady, T.; Minunno, R.; Chong, H.-Y.; Morrison, G.M. Design for disassembly, deconstruction and resilience: A circular economy index for the built environment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 175, 105847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Tam, V.W.; Le, K.N.; Osei-Kyei, R. Factors affecting the price of recycled concrete: A critical review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lage, I.; Vázquez-Burgo, P.; Velay-Lizancos, M. Sustainability evaluation of concretes with mixed recycled aggregate based on holistic approach: Technical, economic and environmental analysis. Waste Manag. 2020, 104, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffar, S.H.; Burman, M.; Braimah, N. Pathways to circular construction: An integrated management of construction and demolition waste for resource recovery. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, M.; Iversen, L.L.; Best, J.; Franks, D.M.; Hackney, C.R.; Latrubesse, E.M.; Tusting, L.S. Sand, gravel, and UN Sustainable Development Goals: Conflicts, synergies, and pathways forward. One Earth 2021, 4, 1095–1111. [CrossRef]

- Söderholm, P. Taxing virgin natural resources: Lessons from aggregates taxation in Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, A.; Sarmah, A.K. Construction and demolition waste generation and properties of recycled aggregate concrete: A global perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 186, 262–281. [CrossRef]

- EPA. Construction and Demolition Debris Generation in the United States, 2015; Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: 2018; p. 26.

- Makul, N. Recycled Aggregate Concrete: Technology and Properties; CRC Press: 2023.

- Sereewatthanawut, I.; Prasittisopin, L. Environmental evaluation of pavement system incorporating recycled concrete aggregate. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2020, 13, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmoorian, F.; Samali, B. Laboratory investigations on the utilization of RCA in asphalt mixtures. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2018, 11, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayasundara, M.; Mendis, P.; Crawford, R.H. Methodology for the integrated assessment on the use of recycled concrete aggregate replacing natural aggregate in structural concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evidence Implementation 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodorou, S. Umbrella reviews: what they are and why we need them. Eur. J. Epidemiology 2019, 34, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of internal medicine 2009, 151, W-65–W-94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boell, S.K.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. On being ‘systematic’in literature reviews in IS. Journal of Information Technology 2015, 30, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group*, t. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pae, C.-U. Why systematic review rather than narrative review? Psychiatry investigation 2015, 12, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P.; Gillett, R. How to do a meta-analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 2010, 63, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habert, G.; Miller, S.A.; John, V.M.; Provis, J.L.; Favier, A.; Horvath, A.; Scrivener, K.L. Environmental impacts and decarbonization strategies in the cement and concrete industries. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Fang, Q.; Yu, H.; Haiyan, M. Mesoscopic modelling of concrete material under static and dynamic loadings: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, T.; Behdinan, K. Insight of discrete scale and multiscale methods for characterization of composite and nanocomposite materials. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering 2023, 30, 1231-1265. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.D.; Kuramochi, T.; Wicke, B. The status of corporate greenhouse gas emissions reporting in the food sector: An evaluation of food and beverage manufacturers. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 361, 132279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Humpenöder, F.; Churkina, G.; Reyer, C.P.O.; Beier, F.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Popp, A. Land use change and carbon emissions of a transformation to timber cities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller-Casseres, E.; Edelenbosch, O.Y.; Szklo, A.; Schaeffer, R.; van Vuuren, D.P. Global futures of trade impacting the challenge to decarbonize the international shipping sector. Energy 2021, 237, 121547. [CrossRef]

- Shah, I.H.; Miller, S.A.; Jiang, D.; Myers, R.J. Cement substitution with secondary materials can reduce annual global CO2 emissions by up to 1.3 gigatons. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robalo, K.; Costa, H.; Carmo, R.D.; Júlio, E. Experimental development of low cement content and recycled construction and demolition waste aggregates concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 273, 121680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria, M.; Vázquez, E.; Marí, A. Microstructure analysis of hardened recycled aggregate concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2006, 58, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, M.J.; Davis, M.; de la Rosa, A.; Weldon, B.D.; Kurama, Y.C. Strength and stiffness of concrete with recycled concrete aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa, M.E.; Zaccardi, Y.A.V.; Zega, C.J. A critical review of the resulting effective water-to-cement ratio of fine recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 313, 125536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verian, K.P.; Ashraf, W.; Cao, Y. Properties of recycled concrete aggregate and their influence in new concrete production. 2018, 133, 30–49. [CrossRef]

- Hayles, M.; Sanchez, L.F.; Noël, M. Eco-efficient low cement recycled concrete aggregate mixtures for structural applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 169, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.; Kwan, W.H.; Ramli, M. Mechanical strength and durability properties of concrete containing treated recycled concrete aggregates under different curing conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 155, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berndt, M.L. Properties of sustainable concrete containing fly ash, slag and recycled concrete aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 2606–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Tiwari, B.; Kumar, S.; Barai, S.V. Comparative LCA of recycled and natural aggregate concrete using Particle Packing Method and conventional method of design mix. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 228, 679-691. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, W.; Fan, Y.; Huang, X. An overview of study on recycled aggregate concrete in China (1996–2011). Construction and Building Materials 2012, 31, 364–383. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, J. A review of life cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete. 2019, 209, 115–125. [CrossRef]

- Anike, E.E.; Saidani, M.; Ganjian, E.; Tyrer, M.; Olubanwo, A.O. The potency of recycled aggregate in new concrete: a review. Constr. Innov. 2019, 19, 594–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xuan, D.; Sojobi, A.; Liu, S.; Poon, C.S. Efficiencies of carbonation and nano silica treatment methods in enhancing the performance of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, A.; Aslam, F.; Joyklad, P. A scientometric analysis approach to analyze the present research on recycled aggregate concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 46, 103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, F.; Nicolella, M. Mortars with Recycled Aggregates from Building-Related Processes: A ‘Four-Step’ Methodological Proposal for a Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Tam, V.W.; Le, K.N.; Hao, J.L.; Wang, J. Life cycle assessment of recycled aggregate concrete on its environmental impacts: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fonteboa, B.; Martínez-Abella, F. Concretes with aggregates from demolition waste and silica fume. Materials and mechanical properties. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faella, C.; Lima, C.; Martinelli, E.; Pepe, M.; Realfonzo, R. Mechanical and durability performance of sustainable structural concretes: An experimental study. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 71, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, N. Influence of recycled concrete aggregates and Coal Bottom Ash on various properties of high volume fly ash-self compacting concrete. Journal of Building Engineering 2020, 32, 101491,. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; M, M.; Arya, S. Utilization of coal bottom ash in recycled concrete aggregates based self compacting concrete blended with metakaolin. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 144, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; M. , M.; Arya, S. Influence of coal bottom ash as fine aggregates replacement on various properties of concretes: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 138, 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakararoj, N.; Tran, T.N.H.; Sukontasukkul, P.; Attachaiyawuth, A.; Tangchirapat, W.; Ban, C.C.; Rattanachu, P.; Jaturapitakkul, C. Effects of High-Volume bottom ash on Strength, Shrinkage, and creep of High-Strength recycled concrete aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 356, 129233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruji, S.; Brake, N.A.; Hosseini, S.; Adesina, M.; Nikookar, M. Enhancing Recycled Aggregate Concrete Using a Three-Stage Mixed Coal Bottom Ash Slurry Coating. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduli, R.; Mukharjee, B.B. Performance assessment of concrete incorporating recycled coarse aggregates and metakaolin: A systematic approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 233, 117223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Singh, S. Carbonation and electrical resistance of self compacting concrete made with recycled concrete aggregates and metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 121, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduli, R.; Mukharjee, B.B. Effect of incorporation of metakaolin and recycled coarse aggregate on properties of concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 209, 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rais, M.S.; Khan, R.A. Strength and durability characteristics of binary blended recycled coarse aggregate concrete containing microsilica and metakaolin. Innov. Infrastruct. Solutions 2020, 5, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, N.; Tagnit-Hamou, A. Development of ultra-high-performance concrete using glass powder – Towards ecofriendly concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 125, 600–612,. [CrossRef]

- Faried, A.S.; Mostafa, S.A.; Tayeh, B.A.; Tawfik, T.A. The effect of using nano rice husk ash of different burning degrees on ultra-high-performance concrete properties. 2021, 290, 123279. [CrossRef]

- de Siqueira, A.A.; Cordeiro, G.C. Properties of binary and ternary mixes of cement, sugarcane bagasse ash and limestone. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasittisopin, L.; Trejo, D. Effects of Mixing Time and Revolution Count on Characteristics of Blended Cement Containing Rice Husk Ash. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04017262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo, D.; Prasittisopin, L. Chemical Transformation of Rice Husk Ash Morphology. ACI Mater. J. 2015, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Agwa, I.S. Effects of nano cotton stalk and palm leaf ashes on ultrahigh-performance concrete properties incorporating recycled concrete aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 302, 124196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Jamaluddin, N.; Shahidan, S. A review on performance of waste materials in self compacting concrete (SCC). Jurnal Teknologi 2016, 78, 29-35. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Huang, W.; Zhang, L.; Fu, S.; Chen, M.; Ding, S.; Han, B. Mechanical properties of low-carbon ultrahigh-performance concrete with ceramic tile waste powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Suter, D.; Jeffrey-Bailey, T.; Song, T.; Arulrajah, A.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Law, D. Recycling waste materials in geopolymer concrete. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2019, 21, 493–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.; Castro-Gomes, J.P.; Albuquerque, A. Effect of immersion in water partially alkali-activated materials obtained of tungsten mine waste mud. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 35, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraldo, S.; Lopes, S.; Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Lopes, A. Advantages and shortcomings of the utilization of recycled wastes as aggregates in structural concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 298, 123729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara De Maeijer, P.; Craeye, B.; Blom, J.; Bervoets, L. Crumb rubber in concrete—the barriers for application in the construction industry. Infrastructures 2021, 6. [CrossRef]

- Valadares, F.; Bravo, M.; de Brito, J. Concrete with used tire rubber aggregates: Mechanical performance. ACI Materials Journal-American Concrete Institute 2012, 109, 283. [Google Scholar]

- Prasittisopin, L.; Termkhajornkit, P.; Kim, Y.H. Review of concrete with expanded polystyrene (EPS): Performance and environmental aspects. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.-K.; Um, N.; Kim, Y.-J.; Cho, N.-H.; Jeon, T.-W. New policy framework with plastic waste control plan for effective plastic waste management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6049. [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.; Arulrajah, A.; Wong, Y.C.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Maghool, F. Utilizing recycled PET blends with demolition wastes as construction materials. Construction and building materials 2019, 221, 200–209. [CrossRef]

- Gillani, S.T.A.; Hu, K.; Ali, B.; Malik, R.; Elhag, A.B.; Elhadi, K.M. Life cycle impact of concrete incorporating nylon waste and demolition waste. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 50269–50279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, N.K.; Satomi, T.; Takahashi, H. Influence of industrial by-products and waste paper sludge ash on properties of recycled aggregate concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytekin, B.; Mardani-Aghabaglou, A. Sustainable Materials: A Review of Recycled Concrete Aggregate Utilization as Pavement Material. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2021, 2676, 468–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; Park, C. Compressive strength and resistance to chloride ion penetration and carbonation of recycled aggregate concrete with varying amount of fly ash and fine recycled aggregate. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 2352–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revilla-Cuesta, V.; Faleschini, F.; Zanini, M.A.; Skaf, M.; Ortega-López, V. Porosity-based models for estimating the mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete with coarse and fine recycled concrete aggregate. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 44, 103425. [CrossRef]

- Vintimilla, C.; Etxeberria, M. Limiting the maximum fine and coarse recycled aggregates-Type A used in structural concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliyavaradhan, S.K.; Ling, T.-C.; Guo, M.-Z. Upcycling of wastes for sustainable controlled low-strength material: A review on strength and excavatability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 16799–16816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.A.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, C.; Zhao, B.; Xuan, D.; Poon, C.S. Valorization of fine recycled C&D aggregate and incinerator bottom ash for the preparation of controlled low-strength material (CLSM). Clean. Waste Syst. 2022, 3, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.A.; Arshad, M.F.; Nor, N.M. The need of statistical approach for optimising mixture design of controlled low-strength materials. Analytical methods 2021, 28, 29. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Huang, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, S.; Liu, Y. Relationship between internal humidity and drying shrinkage of recycled aggregate thermal insulation concrete considering recycled aggregate content. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomopoulou, K.; Savva, P.; Polydorou, T.; Demetriou, D.; Nicolaides, D.; Petrou, M.F. Effect of Mechanically Treated and Internally Cured Recycled Concrete Aggregates on Recycled Aggregate Concrete. In Proceedings of the Building for the Future: Durable, Sustainable, Resilient, Cham, 2023; 2023//; pp. 957–966. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Nayak, D.; Pandey, A.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, V. Effects of recycled fine aggregates on properties of concrete containing natural or recycled coarse aggregates: A comparative study. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sun, X.; Wang, F.; Wang, J. Mechanical Properties and Durability of Geopolymer Recycled Aggregate Concrete: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikmehr, B.; Al-Ameri, R. A State-of-the-Art Review on the Incorporation of Recycled Concrete Aggregates in Geopolymer Concrete. Recycling 2022, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Deng, X.; Liu, J.; Hui, D. Mechanical properties and microstructures of hypergolic and calcined coal gangue based geopolymer recycled concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 221, 691–708. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.S.; Yang, J.; Bahurudeen, A.; Chinnu, S.; Abdalla, J.A.; Hawileh, R.A.; Siddika, A.; Hamada, H.M. Geopolymer concrete incorporating recycled aggregates: A comprehensive review. Clean. Mater. 2022, 3, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmak, P.; Sukmak, G.; De Silva, P.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Kassawat, S.; Suddeepong, A. The potential of industrial waste: Electric arc furnace slag (EAF) as recycled road construction materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Maghool, F.; Arulrajah, A.; Horpibulsuk, S. Alkali activation of recycled concrete and aluminum salt slag aggregates for semi-rigid column inclusions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasittisopin, L.; Sereewatthanawut, I. Effects of seeding nucleation agent on geopolymerization process of fly-ash geopolymer. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2017, 12, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerzouri, M.; Hamzaoui, R.; Ziyani, L.; Alehyen, S. Influence of slag based pre-geopolymer powders obtained by mechanosynthesis on structure, microstructure and mechanical performance of geopolymer pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuaklong, P.; Jongvivatsakul, P.; Pothisiri, T.; Sata, V.; Chindaprasirt, P. Influence of rice husk ash on mechanical properties and fire resistance of recycled aggregate high-calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete. 2019, 252, 119797. [CrossRef]

- Prasittisopin, L. Power plant waste (fly ash, bottom ash, biomass ash) management for promoting circular economy in sustainable construction: emerging economy context. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment 2024, ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.W.; Aljubory, N.H.; Zidan, R.S. Properties and Performance of Polypropylene Fiber Reinforced Concrete : A review. Tikrit J. Eng. Sci. (TJES) 2021, 27, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuaklong, P.; Wongsa, A.; Boonserm, K.; Ngohpok, C.; Jongvivatsakul, P.; Sata, V.; Sukontasukkul, P.; Chindaprasirt, P. Enhancement of mechanical properties of fly ash geopolymer containing fine recycled concrete aggregate with micro carbon fiber. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damrongwiriyanupap, N.; Srikhamma, T.; Plongkrathok, C.; Phoo-Ngernkham, T.; Sae-Long, W.; Hanjitsuwan, S.; Sukontasukkul, P.; Li, L.-Y.; Chindaprasirt, P. Assessment of equivalent substrate stiffness and mechanical properties of sustainable alkali-activated concrete containing recycled concrete aggregate. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e00982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushkbaghi, M.; Alipour, P.; Tahmouresi, B.; Mohseni, E.; Saradar, A.; Sarker, P.K. Influence of different monomer ratios and recycled concrete aggregate on mechanical properties and durability of geopolymer concretes. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 205, 519–528. [CrossRef]

- Nuaklong, P.; Sata, V.; Chindaprasirt, P. Influence of recycled aggregate on fly ash geopolymer concrete properties. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2300–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, O.; Siad, H.; Lachemi, M.; Dadsetan, S.; Şahmaran, M. Extensive rheological evaluation of geopolymer mortars incorporating maximum amounts of recycled concrete as precursors and aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Li, W.; Tam, V.W.; Luo, Z. Investigation on dynamic mechanical properties of fly ash/slag-based geopolymeric recycled aggregate concrete. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2020, 185, 107776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-Cuesta, V.; Skaf, M.; Faleschini, F.; Manso, J.M.; Ortega-López, V. Self-compacting concrete manufactured with recycled concrete aggregate: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-X.; Ling, T.-C.; Mo, K.-H. Progress in developing self-consolidating concrete (SCC) constituting recycled concrete aggregates: A review. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2021, 28, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, R.; Jagadesh, P.; Fraile-Fernández, F.J.; Pozo, J.M.M.; Juan-Valdés, A. Influence of design parameters on fresh properties of self-compacting concrete with recycled aggregate—a review. Materials 2020, 13, 1-24. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K. Properties of SCC containing pozzolans, Wollastonite micro fiber, and recycled aggregates. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sua-Iam, G.; Makul, N. Recycling prestressed concrete pile waste to produce green self-compacting concrete. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 4587–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-Cuesta, V.; Ortega-López, V.; Skaf, M.; Manso, J.M. Effect of fine recycled concrete aggregate on the mechanical behavior of self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrane, M.; Kenai, S.; Kadri, E.-H.; Aït-Mokhtar, A. Performance and durability of self compacting concrete using recycled concrete aggregates and natural pozzolan. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudali, S.; Kerdal, D.; Ayed, K.; Abdulsalam, B.; Soliman, A. Performance of self-compacting concrete incorporating recycled concrete fines and aggregate exposed to sulphate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasittisopin, L. How 3D Printing Technology Makes Cities Smarter: A Review, Thematic Analysis, and Perspectives. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 3458–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Nerella, V.N.; Krishna, A.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Mechtcherine, V.; Banthia, N. Mix design concepts for 3D printable concrete: A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasittisopin, L.; Jiramarootapong, P.; Pongpaisanseree, K.; Snguanyat, C. Lean manufacturing and thermal enhancement of single-layer wall with an additive manufacturing (AM) structure. ZKG Intern 2019, 4, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sereewatthanawut, I.; Pansuk, W.; Pheinsusom, P.; Prasittisopin, L. Chloride-induced corrosion of a galvanized steel-embedded calcium sulfoaluminate stucco system. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 44, 103376. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, I.; Mechtcherine, V. Effects of volume fraction and surface area of aggregates on the static yield stress and structural build-up of fresh concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 1551. [CrossRef]

- Mechtcherine, V.; Nerella, V.N.; Will, F.; Näther, M.; Otto, J.; Krause, M. Large-scale digital concrete construction–CONPrint3D concept for on-site, monolithic 3D-printing. Automation in construction 2019, 107, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; He, C.; Liu, S.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Bai, G. Study on the rheology and buildability of 3D printed concrete with recycled coarse aggregates. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Sampath, P.V.; Biligiri, K.P. A review of sustainable pervious concrete systems: Emphasis on clogging, material characterization, and environmental aspects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, S.B.; Goudar, S.K.; Thanu, H.; Monisha, B. Performance evaluation of alkali activated slag based recycled aggregate pervious concrete. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Strieder, H.L.; Dutra, V.F.P.; Graeff. G.; Núñez, W.P.; Merten, F.R.M. Performance evaluation of pervious concrete pavements with recycled concrete aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 315, 125384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonicelli, A.; Fuentes, L.G.; Bermejo, I.K.D. Laboratory investigation on the effects of natural fine aggregates and recycled waste tire rubber in pervious concrete to develop more sustainable pavement materials. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2017; p. 032081. [CrossRef]

- Hamada, H.M.; Shi, J.; Abed, F.; Al Jawahery, M.S.; Majdi, A.; Yousif, S.T. Recycling solid waste to produce eco-friendly ultra-high performance concrete: A review of durability, microstructure and environment characteristics. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 876, 162804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Que, Z.; Su, D.; Liu, T.; Zhou, A.; Li, Y. Sustainable use of recycled autoclaved aerated concrete waste as internal curing materials in ultra-high performance concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Gupta, S.; Pang, S.D.; Kua, H.W. Waste Valorisation using biochar for cement replacement and internal curing in ultra-high performance concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, C.; Castellote, M.; Llorente, I.; Andrade, C. Ground water leaching resistance of high and ultra high performance concretes in relation to the testing convection regime. 2006, 36, 1583–1594. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Properties of recycled aggregate concrete designed with equivalent mortar volume mix design. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lee, H. Structural Performance of Reinforced RCA Concrete Beams Made by a Modified EMV Method. Sustainability 2017, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, J.; Kong, X.; Chen, C.; Lehman, D.E. Mechanical and durability properties of sustainable self-compacting concrete with recycled concrete aggregate and fly ash, slag and silica fume. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 231, 117115. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Liu, J.; Shi, C. Autogenous shrinkage and drying shrinkage of recycled aggregate concrete: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.P.; Gunasekara, C.; Law, D.W.; Houshyar, S.; Setunge, S.; Cwirzen, A. A critical review on drying shrinkage mitigation strategies in cement-based materials. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-B.; He, Z.-H.; Shi, J.-Y.; Liang, C.-F.; Shibro, T.-G.; Liu, B.-J.; Yang, S.-Y. Mechanical properties, drying shrinkage, and nano-scale characteristics of concrete prepared with zeolite powder pre-coated recycled aggregate. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 319, 128710. [CrossRef]

- Qaidi, S.; Najm, H.M.; Abed, S.M.; Özkılıç, Y.O.; Al Dughaishi, H.; Alosta, M.; Sabri, M.M.S.; Alkhatib, F.; Milad, A. Concrete Containing Waste Glass as an Environmentally Friendly Aggregate: A Review on Fresh and Mechanical Characteristics. Materials 2022, 15, 6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltese, C.; Pistolesi, C.; Lolli, A.; Bravo, A.; Cerulli, T.; Salvioni, D. Combined effect of expansive and shrinkage reducing admixtures to obtain stable and durable mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 2244–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, M.Z.Y.; Wong, K.S.; Rahman, M.E.; Meheron, S.J. Deterioration of marine concrete exposed to wetting-drying action. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 278, 123383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheela, V.S.; John, M.; Biswas, W.; Sarker, P. Combating urban heat island effect—A review of reflective pavements and tree shading strategies. Buildings 2021, 11, 93. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, H.; Ma, C.; Sun, J.; Lai, J. Review of the Strengthening Methods and Mechanical Properties of Recycled Aggregate Concrete (RAC). Crystals 2022, 12, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M. Roles of carbonated recycled fines and aggregates in hydration, microstructure and mechanical properties of concrete: A critical review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, K.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Song, B.; Guo, H.; Li, G.; Shi, C. Influence of pre-treatment methods for recycled concrete aggregate on the performance of recycled concrete: A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-R.; Hong, Z.-Q.; Zhang, J.-L.; Kou, S.-C. Pore size distribution and ITZ performance of mortars prepared with different bio-deposition approaches for the treatment of recycled concrete aggregate. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 111, 103631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Shen, A.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Guo, Y. Properties and mechanisms of brick-concrete recycled aggregate strengthened by compound modification treatment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 315, 125678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, Y.; Orhan, E. Investigation of the effect on the physical and mechanical properties of the dosage of additive in self-consolidating concrete. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 2849–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, W.M.; Yang, J.; Su, H.; Mo, K.H.; Li, L.; Xie, J. Quality improvement techniques for recycled concrete aggregate: A review. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2019, 17, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, W.F.; Quattrone, M.; John, V.M.; Angulo, S.C. Roughness, wettability and water absorption of water repellent treated recycled aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 146, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasittisopin, L.; Thongyothee, C.; Chaiyapoom, P.; Snguanyat, C. Quality improvement of recycled concrete aggregate by a large-scale tube mill with steel rod. J. Asian Concr. Fed. 2018, 4, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushnood, R.A.; Qureshi, Z.A.; Shaheen, N.; Ali, S. Bio-mineralized self-healing recycled aggregate concrete for sustainable infrastructure. Sci. Total. Environ. 2020, 703, 135007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagrán-Zaccardi, Y.A.; Marsh, A.T.; Sosa, M.E.; Zega, C.J.; De Belie, N.; Bernal, S.A. Complete re-utilization of waste concretes–Valorisation pathways and research needs. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2022, 177, 105955. [CrossRef]

- Dündar, B.; Tuğluca, M.S.; İlcan, H.; Şahin, O.; Şahmaran, M. The effects of various operational- and materials-oriented parameters on the carbonation performance of low-quality recycled concrete aggregate. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68, 106138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, M.; Skocek, J.; Skibsted, J.; Ben Haha, M. CO2 mineralization of demolished concrete wastes into a supplementary cementitious material – a new CCU approach for the cement industry. RILEM Tech. Lett. 2021, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Q.; Huang, T.; Peng, W. Mineralization and utilization of CO2 in construction and demolition wastes recycling for building materials: A systematic review of recycled concrete aggregate and recycled hardened cement powder. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 298, 121512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.; Kim, S. CO2 emission and construction cost reduction effect in cases of recycled aggregate utilized for nonstructural building materials in South Korea. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 360, 131962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, L.; Eklund, M. Environmental evaluation of reuse of by-products as road construction materials in Sweden. Waste Manag. 2003, 23, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, V.W.; Butera, A.; Le, K.N. Carbon-conditioned recycled aggregate in concrete production. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 672–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanbakhsh, A.; Bank, L.C.; Baez, T.; Wernick, I. Comparative LCA of concrete with natural and recycled coarse aggregate in the New York City area. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 23, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoeri, C.; Sanyé-Mengual, E.; Althaus, H.-J. Comparative LCA of recycled and conventional concrete for structural applications. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schepper, M.; Van den Heede, P.; Van Driessche, I.; De Belie, N. Life Cycle Assessment of Completely Recyclable Concrete. Materials 2014, 7, 6010–6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.; Innis, S.; Kunz, N.C.; Steen, J. The mining industry as a net beneficiary of a global tax on carbon emissions. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; AbdelHadi, M.; Kongpuang, M.; Pansuk, W.; Remennikov, A.M. Digital Twins for Managing Railway Bridge Maintenance, Resilience, and Climate Change Adaptation. Sensors 2022, 23, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, Y.; Petri, I.; Barati, M. Blockchain supported BIM data provenance for construction projects. Comput. Ind. 2022, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamledari, H.; Fischer, M. The application of blockchain-based crypto assets for integrating the physical and financial supply chains in the construction & engineering industry. Autom. Constr. 2021, 127, 103711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayeta, M. BIM: blockchain interface framework for the construction industry. International journal of sustainable real estate and construction economics 2021, 2, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaskova, K.; Ward, P.; Svabova, L. Deep learning-assisted smart process planning, cognitive automation, and industrial big data analytics in sustainable cyber-physical production systems. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics 2021, 9, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, L.P.d.S.; Lewandrowski, T.; Liu, P.; Kaewunruen, S. Environmental risks and uncertainty with respect to the utilization of recycled rolling stocks. Environments 2017, 4, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.V.; de Brito, J.; Dhir, R.K. Use of recycled aggregates arising from construction and demolition waste in new construction applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschi, E.; Bonoli, A. The Commitment of Packaging Industry in the Framework of the European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Forés, V.; Pacheco-Blanco, B.; Capuz-Rizo, S.; Bovea, M.D. Environmental Product Declarations: exploring their evolution and the factors affecting their demand in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 116, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereewatthanawut, I.; Panwisawas, C.; Ngamkhanong, C.; Prasittisopin, L. Effects of extended mixing processes on fresh, hardened and durable properties of cement systems incorporating fly ash. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Béton, F.I. fib model code for concrete structures 2010; Wiley-vch Verlag Gmbh: 2013.

- Marinković, S.; Josa, I.; Braymand, S.; Tošić, N. Sustainability assessment of recycled aggregate concrete structures: A critical view on the current state-of-knowledge and practice. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 1956–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadawo, A.; Sadagopan, M.; During, O.; Bolton, K.; Nagy, A. Combination of LCA and circularity index for assessment of environmental impact of recycled aggregate concrete. J. Sustain. Cem. Mater. 2023, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.; Wijayasundara, M.; Pathirana, P.N.; Law, K. De-risking resource recovery value chains for a circular economy – Accounting for supply and demand variations in recycled aggregate concrete. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2021, 168, 105312. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yazan, D.M.; Bhochhibhoya, S.; Volker, L. Towards Circular Economy through Industrial Symbiosis in the Dutch construction industry: A case of recycled concrete aggregates. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 293, 126083. [CrossRef]

| Study type | TITLE-ABS-KEY ( review ) |

| AND | |

| Recycled concrete aggregate | TITLE-ABS-KEY ( recycl* AND aggregate ) |

| OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( recycl* AND aggregate AND concrete ) | |

| OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( recycl* AND concrete ) | |

| OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( reclaime* AND aggregate ) | |

| AND | |

| Mix design | TITLE-ABS-KEY ( mix* AND design ) |

| OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( mix* AND proportion* ) |

| Authors | Quality of papers reviewed | Classification of review |

| Hamada et al. | 85 | Narrative |

| Zhang et al. | 111 | Narrative |

| Zhang et al. | 142 | Systematic |

| Singer et al. | 162 | Narrative |

| Liu et al. | 133 | Narrative |

| Nikmehr et al. | 192 | Narrative |

| Alhawat et al. | 210 | Systematic |

| Zhang et al. | 90 | Meta-analysis |

| Xing et al. | 253 | Meta-analysis |

| Prasittisopin et al. | 108 | Meta-analysis |

| Kim | 174 | Narrative |

| Kara De Maeijer et al. | 171 | Narrative |

| Nedeljkovic et al. | 30 | Meta-analysis |

| Vitale et al. | 162 | Narrative |

| Hou et al. | 97 | Narrative |

| Martínez-García et al. | 159 | Meta-analysis |

| Singh et al. | 108 | Meta-analysis |

| Revilla-Cuesta et al. | 107 | Narrative |

| Kirthika et al. | 103 | Narrative |

| Anike et al. | 95 | Narrative |

| Zhang et al. | 57 | Narrative |

| Mohajerani et al. | 196 | Meta-analysis |

| Ismail et al. | 172 | Meta-analysis |

| Parameter | Number of observations | a | M |

| cRCA | 42 | 0.871657 | -0.001913 |

| fRCA | 54 | 0.969544 | -0.002418 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).