1. Introduction

Understanding the dynamics of migration, discrimination and social attitudes in Slovenia requires a focused analysis of how the changing flows of goods and people influence hatred and intolerance. Migration is not just a demographic phenomenon, but a multi-layered process shaped by historical, economic, and political forces. These forces create a complex interplay of benefits and challenges. Migration contributes to economic growth and labor market diversification but also provokes social tensions, discrimination, and integration issues.

This paper addresses the research question: "How do the changing flows of goods and people affect the rise of hate and discrimination in Slovenia?" Sub-questions include: What role do economic interdependencies and trade flows play in shaping societal attitudes toward migration in Slovenia and the EU? How do historical and modern migration trends impact Slovenia’s demographic and social landscape? How do cultural differences and perceptions of threats to local identity and security contribute to discrimination and hatred? What role do media and political rhetoric play in influencing public opinions about migrants? How effective are EU migration policies in addressing integration challenges, and how do Slovenia’s unique historical and social factors shape its experience with migration and discrimination?

Using Slovenia as a case study, the specific socio-political dynamics of the country are examined within the broader European framework. As an EU member state, Slovenia operates within the legal and political structures of the European Union, while at the same time grappling with its unique historical and social challenges. This dual approach allows for an in-depth examination of how local and regional factors interact to shape societal attitudes toward migration and discrimination.

The methodology of this study is based on a qualitative content analysis that focuses on academic literature, statistical data, and historical sources to examine economic, political, and social factors that influence hatred and discrimination. By incorporating historical migration patterns, political conflicts, and socio-economic inequalities, the study assesses how these elements shape societal perceptions of migration in Slovenia and the EU. Statistical data from sources such as Eurostat and national reports are used to provide an empirical basis, while the analysis offers a critical reflection on the impact of migration flows on societal attitudes and policy-making.

The findings aim to provide a comprehensive analysis of migration and its societal impact in Slovenia, with implications for the broader European context. This study contributes to existing scholarship by examining Slovenia as a microcosm of broader EU dynamics, offering insights into the interplay between migration, discrimination, and societal integration. In doing so, it addresses critical questions about the balance between protecting national interests and upholding universal human rights in a globalized world.

Having outlined the foundational role of migration in shaping societal attitudes in Slovenia, the analysis now delves into the economic and democratic factors that influence these dynamics.

2. Economic Development and Democracy

Economic growth and the development of favorable conditions

1 that have a positive impact on people and their environment are stimulating conditions that trigger personal satisfaction, happiness, and the will to progress. Economic development can also be understood as an economic condition that represents the process of improving the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, a region, a local community, or an individual, in accordance with the programs or set goals of an individual nation, a state, a federation of states,...

2 The world's politicians are developing projects to eradicate poverty, which was the basis for the conquest of new markets or the colonization of raw materials.

3. As a result, we understand economic growth as a political phenomenon that demonstrates the well-being of people and is defined as a phenomenon of market productivity measured and represented by the increase in the gross national product (GDP) of an individual country, a union of countries or even continents (Europe is an example). Amartya Kumar Sen, Indian economist and 1998 Nobel Prize winner, redefined economic development as a process that aims to expand human freedoms and capabilities and is not limited to economic growth alone. He criticized the traditional focus on metrics such as gross domestic product and emphasized that true development must improve the well-being and opportunities of individuals. His work inspired researchers and policy makers to adopt a broader view of socio-economic development and include aspects such as health, education and equity in the assessment of a nation's progress.

4 There are also definitions of socio-economic development which we will not mention due to the limited scope of this article.

Democracy, which is considered an indicator of corporate governance, good governance, and political stability, is one of the factors that influence economic growth.

5 But what do we mean by the term democracy? Democracy can generally be understood as the rule of the people, where the power and the right to govern comes from, and is intended for the people themselves. It is assumed that the people exercise their rights directly, which is not true, as there are established models of representative democracy in which the people can only elect their political representatives and give them a mandate to govern on their behalf for a certain period. From this form emerge the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, which are otherwise unified in terms of political dominance, only the functions are divided and mean mutual control. The individual branches of government have specific functions, which they exercise within the framework of the given powers and according to their conscience, over which the citizens have no influence until the next election. The bipolar division of today's world shows that the countries of the West are considered democratic countries and the BRICS countries are autocratic or non-democratic countries where people do not have the basic rights and freedoms laid down in the Declaration of Universal Human Rights

6.

The link between economic development and democracy should ensure a decent life for all people on the human planet, the supply of basic food and drinking water to the population, the development of industrial and other production, and the flow of raw materials, materials, goods, people, and capital.

7. Industry 4.0 has enabled rapid development, a broad market, and a decent standard of living in the developed industrial world, especially in Europe, the USA, Canada, Australia, and some other countries. Models of (soft) advanced manufacturing have emerged where humans are replaced by machines or autonomous devices in many difficult tasks in production or service activities. They have developed models of raw material supply named after the Japanese "Just in Time" model, i.e. the delivery of raw materials to the right place at the right time, eliminating many unnecessary logistics processes and speeding up the production and delivery of products to the market.

8. Europe and the rich countries of the West are becoming countries, regions, or economies where many of the planet's inhabitants want to work and build a new life. However, this independence is not complete, as industry, production, and service companies are dependent on raw materials, materials, and goods from the BRICS countries, which have raw materials, materials and goods that European industry urgently needs.

As a result of the desire to increase production, maintain the market, and develop and expand economic, military, and other power, there is also a need for labor, which is in short supply in Europe, mainly due to the aging of the population. Low birth rates and higher life expectancy have changed the age pyramid in the European Union, which is changing the age structure in Europe. As a result, Europe needs many workers from the economically underdeveloped part of the world as it cannot meet this demand with its population, indicating an increased need for migration.

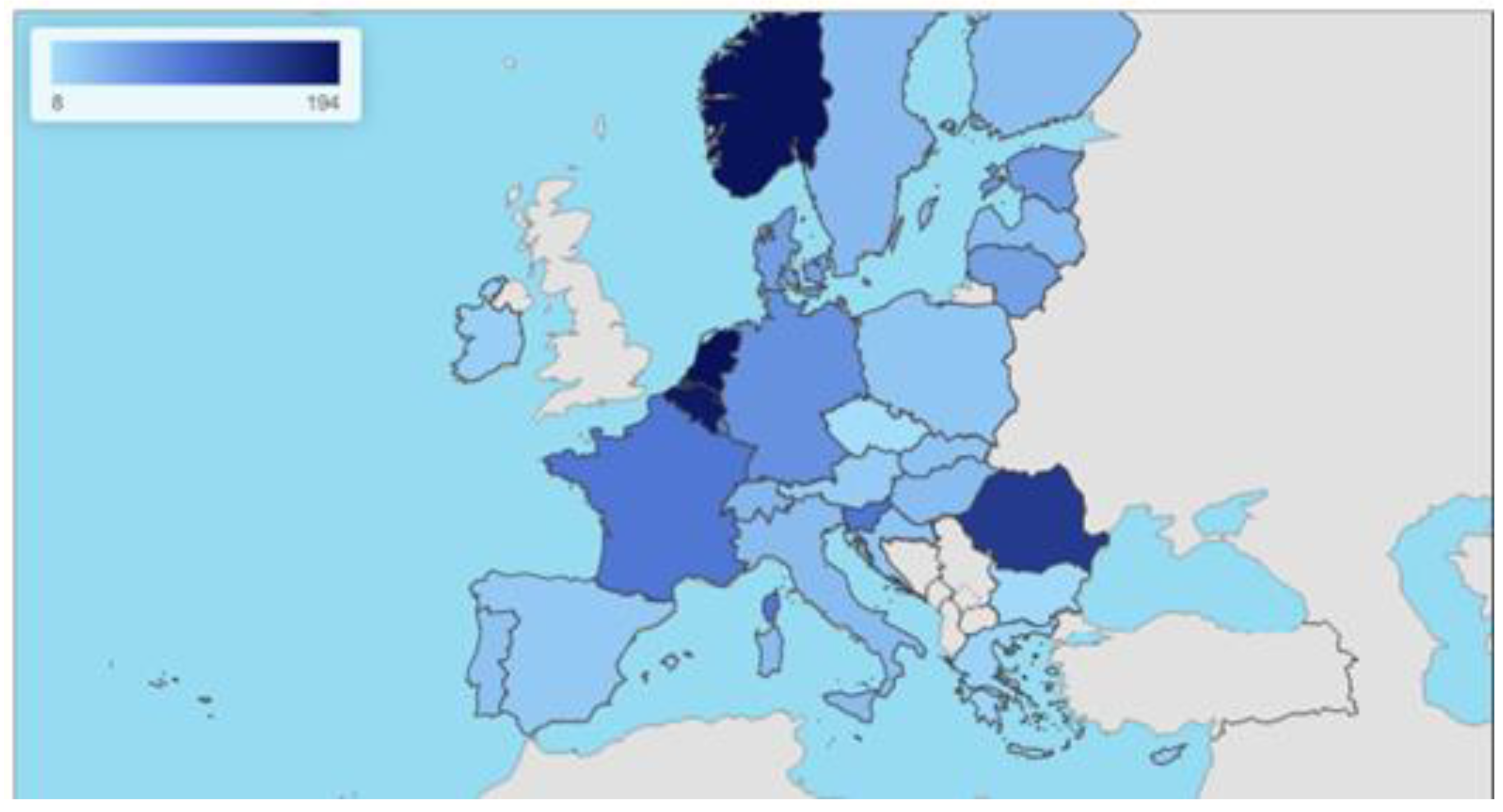

9. The figure below shows the current labor shortages in individual European countries, with the greatest shortages being in welders, plumbers, truck drivers, mechanics, waiters, electricians, cooks, etc., indicating the need for additional labor. As labor shortages have already been identified in many EU countries, migrants are often seen as a potential solution to meet these needs, allowing the economy to adapt more quickly to the needs of the market. However, this often leads to a sense of insecurity and hostility among the local population, as the employment of migrants in these sectors is associated with a threat to the livelihood of the local workforce.

Building upon the interplay between economic growth and democracy, we explore how disparities in development drive global migration patterns and influence societal perceptions.

Figure 1.

Labor shortages in Europe. Source: EURES, "Labour Shortages and Surpluses in Europe".

Figure 1.

Labor shortages in Europe. Source: EURES, "Labour Shortages and Surpluses in Europe".

3. Impacts of Development on World Changes

Differences in development between nations, countries, and continents open up a series of complex questions that often take the form of ambitions or needs for personal progress and the search for new opportunities. The crucial question is how to participate in these development processes – that is, how to contribute through economic, financial, or social mechanisms. Many people therefore choose to migrate to economically more attractive countries such as Europe, which is perceived by many as the "promised land"." In this context, development opportunities represent a key research hypothesis that allows a more accurate understanding of the factors that lead European residents to react in a hostile and discriminatory manner towards immigrants from less developed areas of the world. The fundamental question, then, is whether workers and migrants from less economically developed countries can threaten the existing European social and economic order. This could serve as a basis for analyzing the causes and dynamics of the rise of hatred and discrimination against "other" people, i.e. people from socially and economically different environments.

In the past, people migrated due to various needs - the need to discover new natural resources, the need to explore, the desire to work, or they were forcibly emigrated - as slaves (slavery was interpreted as the status of a person owned by someone and exercising a property right, which they even enshrined in law in the form of a property right, whereby the slave was equal to property (owner's property right), due to which the owner could sell such a person)

10. With the extraction of natural resources and the need for labor, workers were brought in, especially from the Far East and Africa, to serve the economic development of Europe and especially some countries that had the right to colonize. Through education, colonialism can be understood as a general definition of a certain type of relationship or relation between human communities based on total inequality. In them, there is a hierarchy in which one human community exercises control or direct authority over another community, often this form is imposed on a larger number of communities. It is dominated by the ruling class of the dominant global society, which determines the rules of behavior, operation, management, and use of material and other resources, and defines relationships according to the norms it sets. The period of slavery is an important element in the historical analysis of human migration.

For ease of presentation of the considerations in this article, we will use the classification of the world's countries into developed economies, economies in transition, and developing economies

11. Otherwise, we are aware that the division of the world into developing and emerging economies has become increasingly problematic in recent decades, but as it remains entrenched in legal documents, foreign policy discourse, and colloquial usage, we will summarize the discourse to highlight migration trends and use it in this article. In the figure below, we see the countries that are defined as developed economies and which are also the destination countries of migration.

Figure 2.

Developed economies. Source: United Nations, 2014.

Figure 2.

Developed economies. Source: United Nations, 2014.

Economies that define themselves as "developed" achieve high levels of economic prosperity, technological progress, and social stability, including factors such as high GDP, advanced infrastructure, and widespread access to education and health services.

12 These characteristics of developed economies also have a significant impact on global migration patterns.

In addition, modern forms of engineering and technology use, the development of Industry 4.0, and digitalization - supported by globalization and market dynamics - enable people around the world to access knowledge and information, which increases the visibility of opportunities in developed economies and promotes international mobility. As a result, people in countries with lower economic development are more easily informed about the labor needs and economic opportunities available in the countries of the European Union and other economically developed regions. At the same time, the high standard of living in Europe and the favorable conditions for education and employment represents an attractive option for young generations from less developed countries.

Such economic and social incentives encourage migration flows, especially of young people from less economically developed areas, to economically developed countries such as Europe, the United States of America, Canada, and Australia. There they seek better living conditions and opportunities for professional and personal development. This makes them part of global mobility trends and contributes to the globalization of the workforce.

The reverse analysis approach provides a deeper insight into the flow of goods, where one can observe the arrival of raw materials in European industry and the return of finished products to the markets of economically less developed countries, which promotes the flow of information and creates the need for constant adjustments. This process raises issues of globalization and dominance in the handling and trade of raw materials, energy products, and finished goods, with capital-rich countries - those with significant economic, industrial, commodity, financial, market, and military power - regulating these flows in accordance with their interests and often subjugating weaker countries economically, similar to the historical period of colonization.

Economically or militarily powerful countries often provoke conflicts and wars that block access to food, drinking water, and other basic means of survival, forcing people in the less economically developed parts of the world to look for alternatives for their survival. This creates migration flows and the entry of different nations, cultures, religions, colors, and beliefs into European countries, including Slovenia. Years ago, Zelenika predicted in his works changes in traffic and the flow of goods, and predicted progress and economic growth in Europe and the Western world.

13. In this concept of economic development, we can recognize many elements that today have a decisive influence on the flow of goods and migration trends that arise in the context of global economic integration.

As development disparities drive migration, the following section examines the role of trade flows in shaping economic interdependencies and their social implications.

4. Trade Flows and the Changing World

Trade flows have a considerable influence on the development of individual continents and the spread of industrial and other forms of production. These are complex international arrangements in which the influence of capital dominates, while law (such as international legal regulations) often plays only a limited role.

When it comes to the flow of goods in Slovenia, the Slovenian port of Luka Koper is often at the forefront as a "window to the world" for the Slovenian economy and the wider economic hinterland of Central Europe. Simulations predict an increase in cargo throughput in all Adriatic and Mediterranean ports, which would gradually increase the annual throughput in the port of Koper to around 28 to 39 million tons by 2030 and to 50 million tons by 2050. In recent years, annual throughput growth of around 4% has been recorded, which coincides with the period of stable raw material flows when the industry was based on "just-in-time" raw material supply models. Economic growth in Europe and the European Union has occasionally been characterized by recessions in some areas, but these did not significantly affect the planning of raw material flows. Such periods coincided with favorable purchases of energy products, particularly fossil fuels from Russia, which consequently reduced the influence of the USA. In this context, debates have emerged in the European Union, particularly in France, where President Macron has proposed the creation of a European defense, which would involve the creation of a common European army and a possible withdrawal from the NATO alliance. This hypothetical defense model aimed to create a unified security and defense policy that would guarantee Europe's autonomy. Despite these efforts, no unity could be achieved among the members of the European Union, which was also evident during the Covid-19 pandemic. The pandemic revealed the differences in the functioning of the members and the advantage that certain countries had, which is the principle of the idea of equivalence within the European Union.

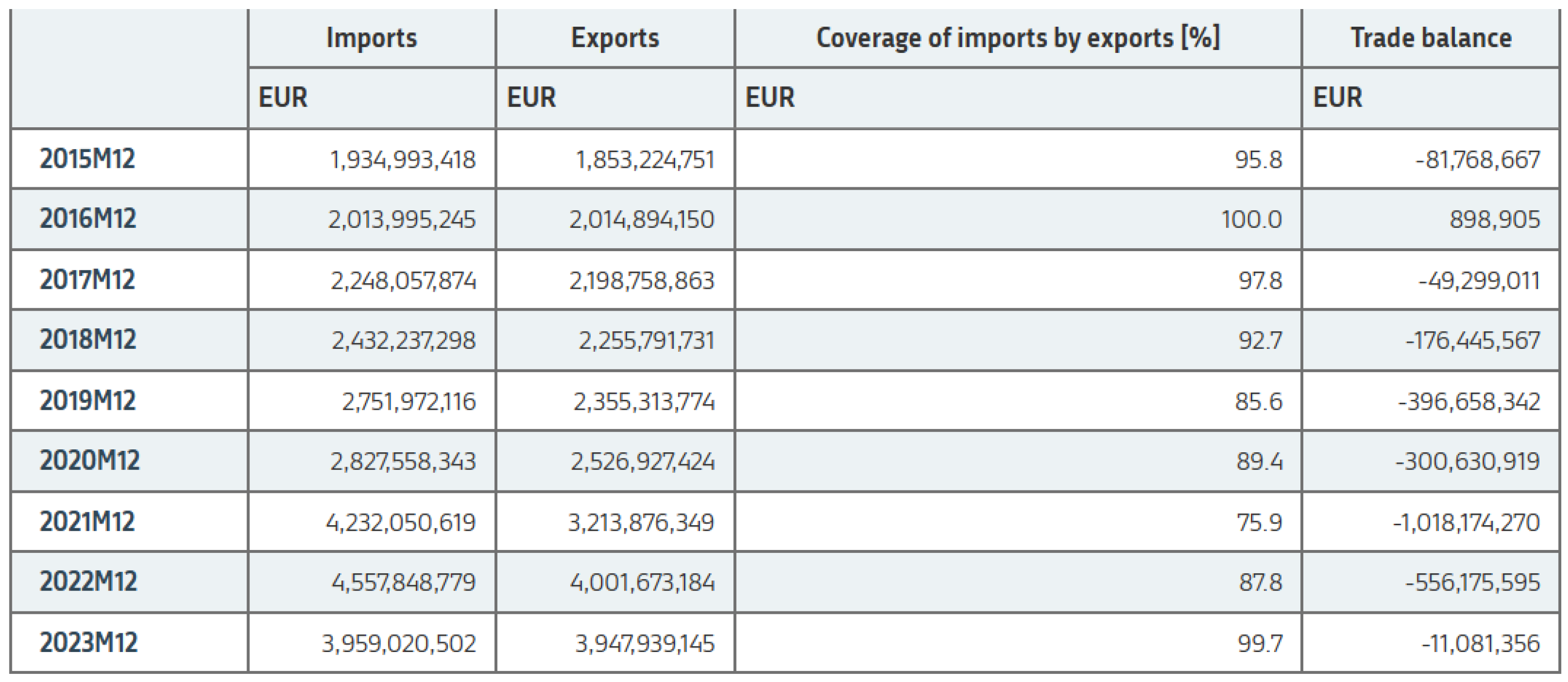

When thinking about the economy of a particular country and its connection to discrimination and hatred, one must also examine the trade segment. So, if we look at Slovenia, we can see that Slovenia exports more than it imports, as can be seen in the figure below.

Figure 3.

Exports, imports, trade balance, and coverage of imports by exports, Slovenia, monthly. Source: Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2024a.

Figure 3.

Exports, imports, trade balance, and coverage of imports by exports, Slovenia, monthly. Source: Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, 2024a.

As we can see from the table below, which shows the values of imports and exports between the EU and countries from different economic areas, from more developed countries (e.g. Germany, Switzerland) to developing countries (e.g. Bangladesh, Mozambique, Egypt, Turkey), Slovenia has the most exports and imports from EU countries, but a significant share of imports comes from developing countries, which indicates their role as suppliers of raw materials and cheaper products.

The import figure of €57,084,306,389.00 compared to export value (€54,997,826,815.00) reflects a slight trade deficit. While this imbalance is not extreme, it may reinforce narratives of economic vulnerability or dependency, potentially fueling nationalist or protectionist sentiments within Slovenia.

Among major import, partners include India and China which could be perceived as competitors in providing low-cost goods or labor. Specifically, India (AND) ranks 2nd with imports worth €1,612,678,414.00. China (CN) ranks 8th with imports worth €7,394,358,304.00. Many other developing countries are included in the list with a major trade presence such as Vietnam (€51,670,671.00), Indonesia (€116,871,793.00) and Egypt (€175,712,650.00).

At the same time, EU countries export goods to less developed countries, for example, Somalia receives exports worth €18,154,433, and Algeria (€99,810,445) and Uzbekistan (€97,987,519) are also listed as export destinations.

So, in less developed countries new markets for European products often emerge. This reciprocal trade increases the economic dependence of the countries, which can lead to imbalances in the EU economy. The above perception is in line with the dependency theory derived from economic theory, which emphasizes how economically stronger countries, which often have industrialized infrastructure and technological progress, maintain their economic influence on less developed countries. This dependency is also reflected in migration flows, where less developed countries with limited economic opportunities contribute labor, while more developed countries, such as EU members, use this labor for their economic growth. In the context of Slovenia and the EU, migrants from less developed countries are a source of cheap labor that contributes to the EU's economic growth, but at the same time creates social tensions, as the local population often perceives this as an intrusion into their economic situation. It is also necessary to mention the world systems theory developed by Immanuel Wallerstein, which states that countries are divided into core, semi-periphery, and periphery according to their economic and political influence. The core countries, which include leading EU members such as Germany and France, attract migrants from the periphery, where there are no equal opportunities for economic development. Slovenia, which is located in the semi-periphery, thus becomes both a destination and a transit point for migrants from the periphery coming to the EU. This position of Slovenia in the world system allows the country to benefit economically from immigrants, but at the same time leads to friction in society, as there is a perception that immigrants are 'invading' the domestic labor market and affecting cultural identity. Tensions can also arise if the local population has the impression that the import of cheap goods from abroad have a negative impact on local jobs and economic stability.

Flows of goods are often accompanied by migration flows, as trade relations between the EU and developing countries also encourage migration from these countries. People often follow the trade route, seeking better opportunities and working in countries with which their home countries have trade links. This can lead to an increase in the immigrant population in the EU, often resulting in social change and sometimes disapproval from the local population, who perceive immigrants as competition for jobs or a burden on social services.

High imports from countries with low production costs (e.g. China, Bangladesh) can give the impression that globalization is putting pressure on local production, which can lead to the European population feeling threatened. This increases the risk of stereotypes and discriminatory views towards immigrants from these countries, which can lead to hostile rhetoric or even physical attacks. According to a report by Spletno Oko migrants are the most common targets, comprising 42% of cases

14.

In countries such as Slovenia and other EU member states, feelings towards immigrants can be driven by a sense of economic pressure and competition, which can lead to discriminatory practices. For instance, foreign workers had equal labor rights as citizens in law, still, discrimination is possible in practice, and conditions of exploitation occurred in some sectors (U.S. Department of State, 2023). Another good example is that of the Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS). The SDS positions itself as the guardian of Slovenian identity, culture, and security, portraying immigrants as threats to these values

15. Populist movements often blame immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers for economic and social challenges, fueling fear and resentment among citizens

16. The SDS uses alternative media and direct messaging strategies, such as slogans and visuals, to amplify its anti-immigrant narrative

17. These platforms allow them to bypass traditional media scrutiny and appeal directly to their audience. The SDS also critiques EU policies, such as mandatory migrant quotas, portraying them as ineffective and a threat to national sovereignty

18.

Countries with high export values (e.g. Switzerland, Germany, Italy) are highly integrated into the global economy, which enables their growth but also increases their dependence on foreign markets. Despite economic growth, integration also brings social challenges, as many members of the local population see this international dependence as a threat to national identity and economic sovereignty.

As the National Research Council notes, without the flow of goods, people, and ideas, cities fail, economies stagnate, and society atrophies. Moreover, a vast empirical literature supports the existence of a positive relationship between migration and bilateral trade linkages, which is confirmed by authors such as Herander and Saavedra, Felbermayr and Toubal

19, because as Figueiredo, Lima and Orefice

20 note, international migrants (especially if they are highly skilled) can provide additional information about the country of origin, thus reducing bilateral trade costs, which encourages exports from the host country to the migrants' country of origin. We can therefore say that migrants help local companies overcome cultural barriers to trade (language, local consumer tastes, etc.) and build international business relationships. In this way, they contribute to greater integration into global markets, where goods flow more easily between host countries and their partners, strengthening trade dynamics and connecting economically less developed and developed regions. Despite these positive effects, increasing migration flows and the globalization of trade routes can create feelings of hostility and discrimination in host countries, mainly due to the perception that immigrants are taking jobs away from locals or changing existing social structures. In addition, cultural differences between migrants and natives in certain contexts can hinder social integration, leading to the emergence of prejudices and exclusionary attitudes that further increase tensions between different groups in the host society, which we will discuss in more detail in later subsections.

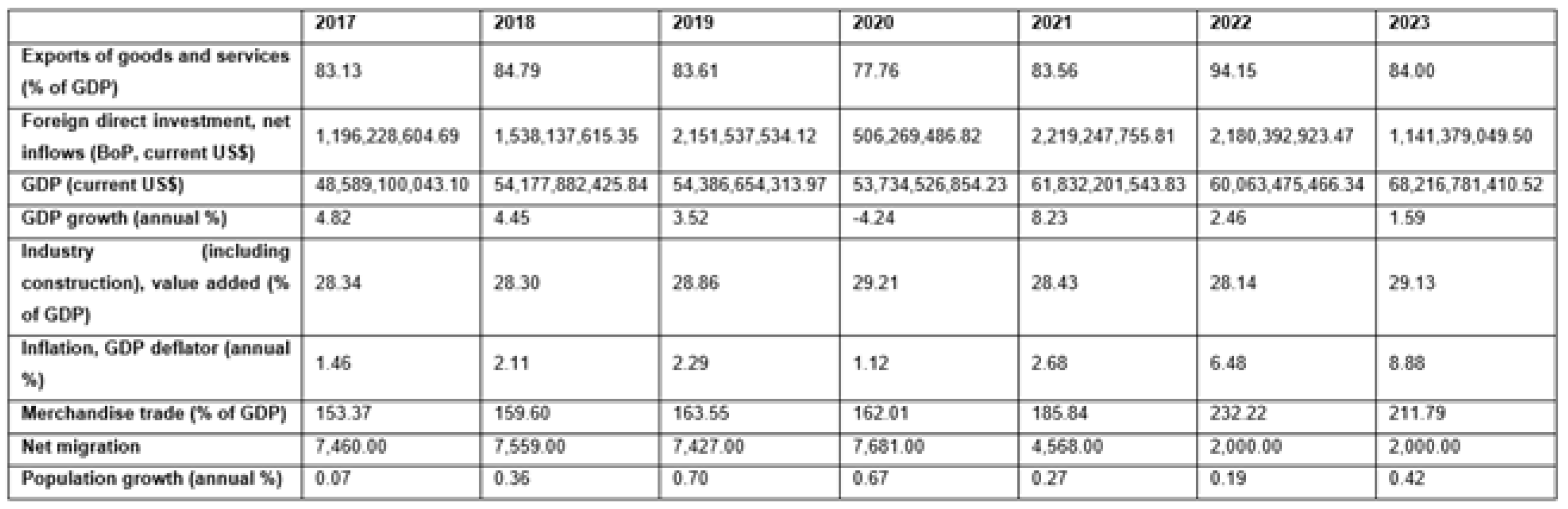

The table below shows that exports account for a significant share of GDP in Slovenia, fluctuating between 77% and 94% in the years under review. A high dependence on exports, especially in smaller economies such as Slovenia, can make the economy vulnerable to fluctuations in global trade. Growing dependence on exports could increase economic insecurity among residents in the face of a potential downturn in global markets, which may fuel xenophobia as migrants are seen as a threat to local jobs and economic stability. In addition, foreign direct investment inflows show the volatility and reduced attractiveness of Slovenia for foreign investors. GDP growth is fluctuating, with strong negative growth in 2020 (-4.24%) during the pandemic, leading to a sense of insecurity, especially among the low-income population, which can lead to discontent if locals feel that migrants or foreign-born residents are receiving undue benefits. The Slovenian economy, which is highly dependent on industrial production, could attract workers from abroad to fill low-paid, high-demand jobs. However, such behavior could be perceived as direct competition by the local population, which could lead to increased discriminatory attitudes, especially in regions struggling with economic difficulties.

The high proportion of exports and merchandise trade relative to GDP (94.15% in 2022 for exports, 232.22% in 2022 for merchandise trade) signals Slovenia's heavy integration into global supply chains. This dependency makes the economy sensitive to global market shifts, which could heighten public anxieties about foreign competition. Trade with countries like India and China (

Table 1) further illustrates Slovenia’s reliance on cost-effective imports, which might be viewed as undermining local production or employment.

In addition, the increase in inflation, especially in 2022 and 2023, where it reached 6.48% and 8.88% respectively, hit lower-income households harder, affecting the local population's attitude towards immigrants, as there were public complaints that funds were being diverted to support migrants rather than the local population.

Figure 4.

World Development Indicators – Slovenia (2017-2023). Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Figure 4.

World Development Indicators – Slovenia (2017-2023). Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

The above-mentioned rhetoric could be seen both on social networks and in right-wing media such as Moja Dolenjska, where we can read:

"While the majority of citizens are busy surviving and businesses are busy with declining orders and providing money for increasingly taxed salaries and other expenses, while the poverty rate in the country is rising and most of the public service is on strike, the ruling coalition (Svoboda movement, SD and Left) has accelerated preparations for the reception of tens of thousands of new illegal immigrants, while shifting its focus to Palestine, euthanasia, drug use, etc. At the taxpayers' expense, of course."

The Slovenian police dealt with a substantially higher number of cases involving migrants illegally crossing into Slovenia from Croatia along the Balkan route in 2023 compared to the previous year. Specifically, they handled 58,193 such cases last year, representing an 84% rise from 2022

21. Moreover, these cases made up 96% of all unauthorized border crossings recorded in Slovenia in 2023 (The Slovenia Times, 2024). As we have already mentioned, this discourse was also visible on social networks, since the above-mentioned discourse, which was then adopted by the public, was also spread by prominent politicians. In the picture below, we see the entry of the leader of the largest opposition party SDS, Mr. Janez Janša, who states: "They gave the money that was intended for your grandmother to illegal immigrants. The Golob’s government calls this a balanced social policy."

22 The publication emerged as a political campaign in June 2024 in connection with the holding of consultative referendums on the regulation of the right to assistance in the voluntary termination of life (this euthanasia referendum), on the introduction of preferential votes for elections to the National Assembly and the cultivation and processing of cannabis for medical purposes and the cultivation and possession of cannabis for limited personal use.

23 This discourse, propagated through posts like Janša’s, reflects a broader strategy to align economic and social fears with anti-immigration stances, framing migration as detrimental to the interests of the local population.

Figure 4.

Facebook posts about the migrants. Source: Janša, Facebook post, December 17, 2022.

Figure 4.

Facebook posts about the migrants. Source: Janša, Facebook post, December 17, 2022.

The impact of trade flows naturally intersects with migration trends, particularly within Europe, where economic opportunities draw individuals seeking improved living conditions

5. Migration to Europe and Members of the European Union

Migration flows to Europe have a long history, as immigration to the European continent has existed since the beginning of mankind. The recorded periods of migration date back to the 20th century, when the dynamics of migration were significantly influenced by world wars, the need for reconstruction, demographic deficits, and the economic need for labor. An important historical factor is the colonialism of Western European countries, which was linked to the exploitation of natural resources, raw materials, capital, and labor, followed by strong immigration to these countries after the end of the Second World War. As a result of economic migration, European countries have gradually developed into culturally and ethnically diverse societies in which both migrants of European and non-European origin live today.

The processes of modern globalization, such as the search for new markets, raw materials, and energy sources, have accelerated migration to Europe, which has created the impression among societies in economically less developed regions that Europe is the "promised land". In the second half of the last century, this led to certain negative reactions of the European population (including the Slovenian population) towards immigrants. Thus, hatred of those who are different - in terms of ethnicity, language, culture, religion, or education - also arises from a sense of threat, in which the inhabitants of Europe (and Slovenia) perceive insecurities regarding their employment opportunities, their security and the preservation of their cultural and religious identity.

24

In the various periods of migration, Europe sometimes encouraged and sometimes restricted immigration, which led to the introduction of specific categories for evaluating the various migratory movements. Immigrants were divided into several categories: The first category includes labor migrants, consisting of legal (lawful) migrants who came to Europe with properly regulated permits to work, and illegal (unlawful) workers who regulated their legal status later (when they could). The second category consists of refugees fleeing the political regimes and conditions in their countries of origin.

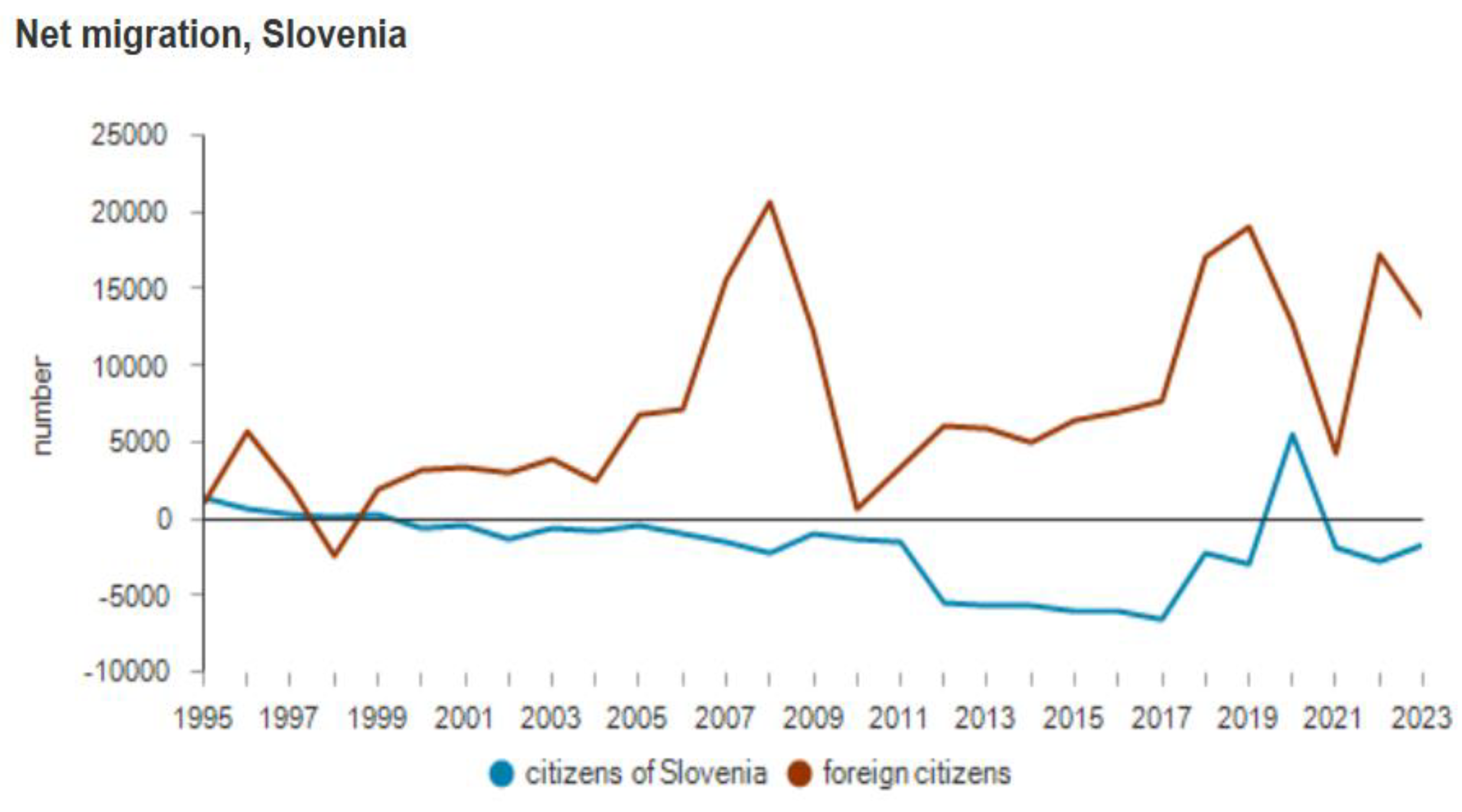

Figure 5.

Net migration Slovenia 1995-2023. Source: Republic of Slovenia Statistical Office (2023).

Figure 5.

Net migration Slovenia 1995-2023. Source: Republic of Slovenia Statistical Office (2023).

Figure 6.

Net migration in Slovenia. Source: Republic of Slovenia Statistical Office (2023).

Figure 6.

Net migration in Slovenia. Source: Republic of Slovenia Statistical Office (2023).

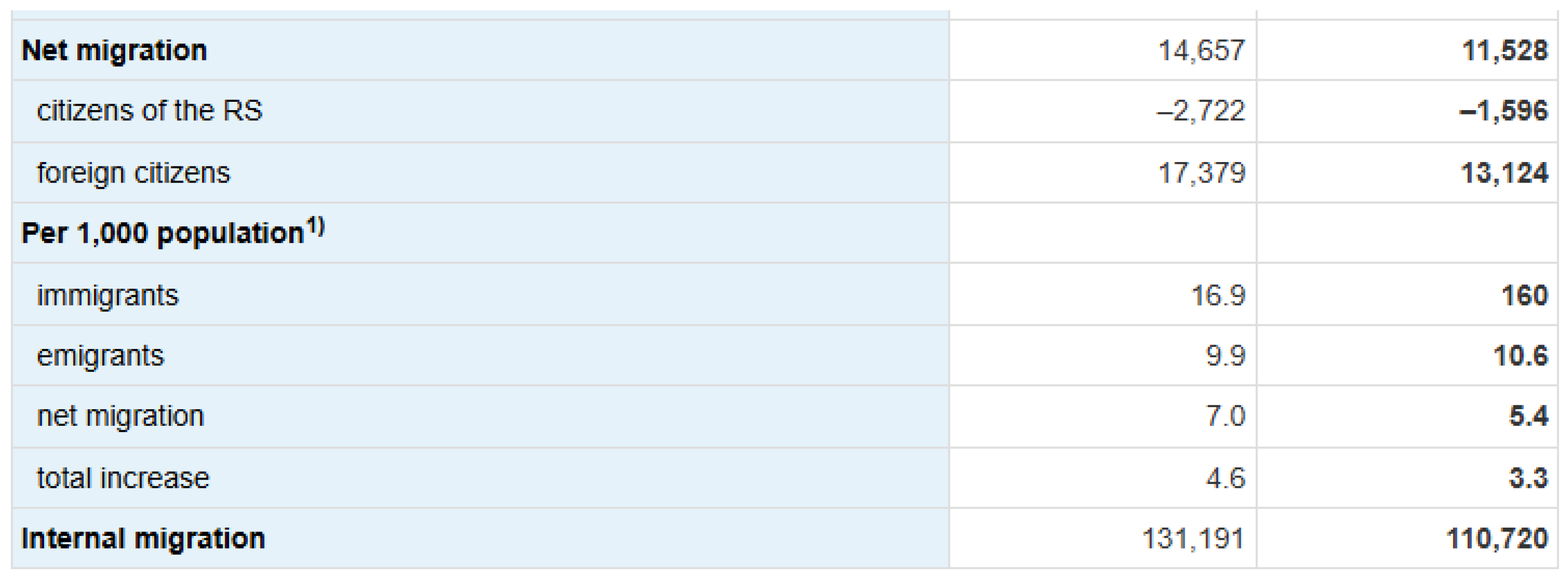

The table highlights Slovenia's migration trends for 2022 and 2023. Net migration remained positive, driven by foreign citizens (17,379 in 2022 and 13,124 in 2023), while Slovenian citizens had a negative net migration (-2,722 in 2022 and -1,596 in 2023). Immigration per 1,000 population surged, while emigration rates were stable, leading to a slight decline in net migration from 7.0 in 2022 to 5.4 in 2023. Internal migration also decreased, from 131,191 moves in 2022 to 110,720 in 2023. These trends suggest Slovenia remains a key destination for foreign nationals despite slowing overall migration growth. The EU, formed by its member states, is a unique partnership between European countries, also known as EU members. Together, these countries cover most of the European territory and have a population of about 447 million people, which is about 6% of the world's population. The EU is conceived as a unique economic and political union based on several mutual treaties concluded after the Second World War to promote stability, peace, and economic progress. The original aim of this union was economic cooperation, based on the idea that economically interdependent countries reduce the likelihood of disputes and conflicts.

The European Economic Community (EEC) was founded in 1958 as an economic union of six European countries: Belgium, Germany, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. Today, the EU comprises 27 member states linked by four fundamental freedoms: free movement of persons, free movement of capital, free movement of goods, and free movement of services. We also have a common currency, the euro, which enables close economic, financial, and political cooperation.

An important step towards greater integration was the adoption of an agreement on the free movement of persons within the EU with the implementation of the 1985 Schengen Agreement, which gives citizens of the Member States and their family members the right to live and work anywhere in the EU. This freedom of movement does not apply to non-EU citizens and members of the European Economic Area (EEA) unless they have a long-term residence permit in the Schengen area, which is only valid for tourist visits of up to three months. Critics of this agreement, particularly lawyers and migration policy experts, point to the potential incentives for undeclared work that freedom of movement in the Schengen area may entail.

Western European countries' need for affordable labor has led to an increased influx of migrants from Eastern Europe, mainly to Spain, Greece, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and the UK, which countries have tacitly accepted as a benefit. Despite initial concerns about cultural threats and intolerance due to ethnic or religious differences, these countries eventually focused on the economic benefits of immigration. Migration flows were characterized by historical, geographical, linguistic, and cultural connections. For example, Great Britain was a frequent choice for Poles, while Spain and Italy attracted mainly Romanians and Bulgarians.

These immigrants have successfully adapted to the new social and professional conditions while maintaining their cultural identity and contributing to diversity through the exchange of cultural values, cuisine, and tourist practices. Modern expressions of cultural differences often take the form of cultural events and festivals that promote understanding and cultural exchange, thus reducing the intolerance that characterized such migrations in the past and strengthening the bonds between the different cultures in Europe.

A standardized form of education within the member states of the European Union for all students within the member states of the EU has also been achieved.

25. This process is known as the Bologna Process and the European Higher Education Area, which enables better coordination of European higher education systems. It is about creating the European Higher Education Area, which facilitates the mobility of students and staff, improves the integration and accessibility of higher education, and strengthens the attractiveness and competitiveness of European higher education on a global scale. This process also enables internal migration, where young people have the opportunity to work anywhere in the EU.

Under the Schengen Agreement and the unified Bologna education system, perceived intolerance or hostility between the nations of the European Union has gradually diminished as EU citizens increasingly acquire a common identity of European citizenship.

However, it must be recognized that migration "is “also a controversial issue; because they bring with them the unknown, they trigger fears of the destruction of local culture, traditions, and customs, of the dominance of migrants /.../",

26 which will form part of the findings of the present study.

Focusing on Europe as a migration destination, the discussion now narrows to the movement of individuals from economically underdeveloped countries and their unique challenges.

6. Migration from Economically Underdeveloped Countries

The study of commodity flows and the movement of raw materials from economically underdeveloped countries shows that movements and migrations are closely linked to the development of industry, with capital having a significant influence on the development of the industrial sector and thus on the increase in demand for labor. Even internal population movements within the European Union could not meet the demand for labor, necessitating a soft form of labor migration from countries with lower economic development. The increase in migration flows became more evident as early as the 1980s, mainly as a result of global economic inequalities between rich and poor countries.

In May 2009, the European Commission adopted an initiative to introduce the EU Blue Card to attract highly skilled workers from less developed countries and give them access to employment in any of the participating EU Member States

27. It is the EU's response to the global race for talent. With the update of the Blue Card Directive in October, the conditions for entry and residence of highly skilled workers from third countries will be further harmonized by 2021, with a particular focus on sectors where there is a shortage of expertise. With these measures, the EU has become a more attractive destination for talent from less economically developed countries, whose work contributes to the development of technological innovation and the advancement of scientific achievements in the Union. This approach enables the legal immigration of highly qualified people from these countries, who use their skills to contribute to the development of cutting-edge technologies and solutions in the EU.

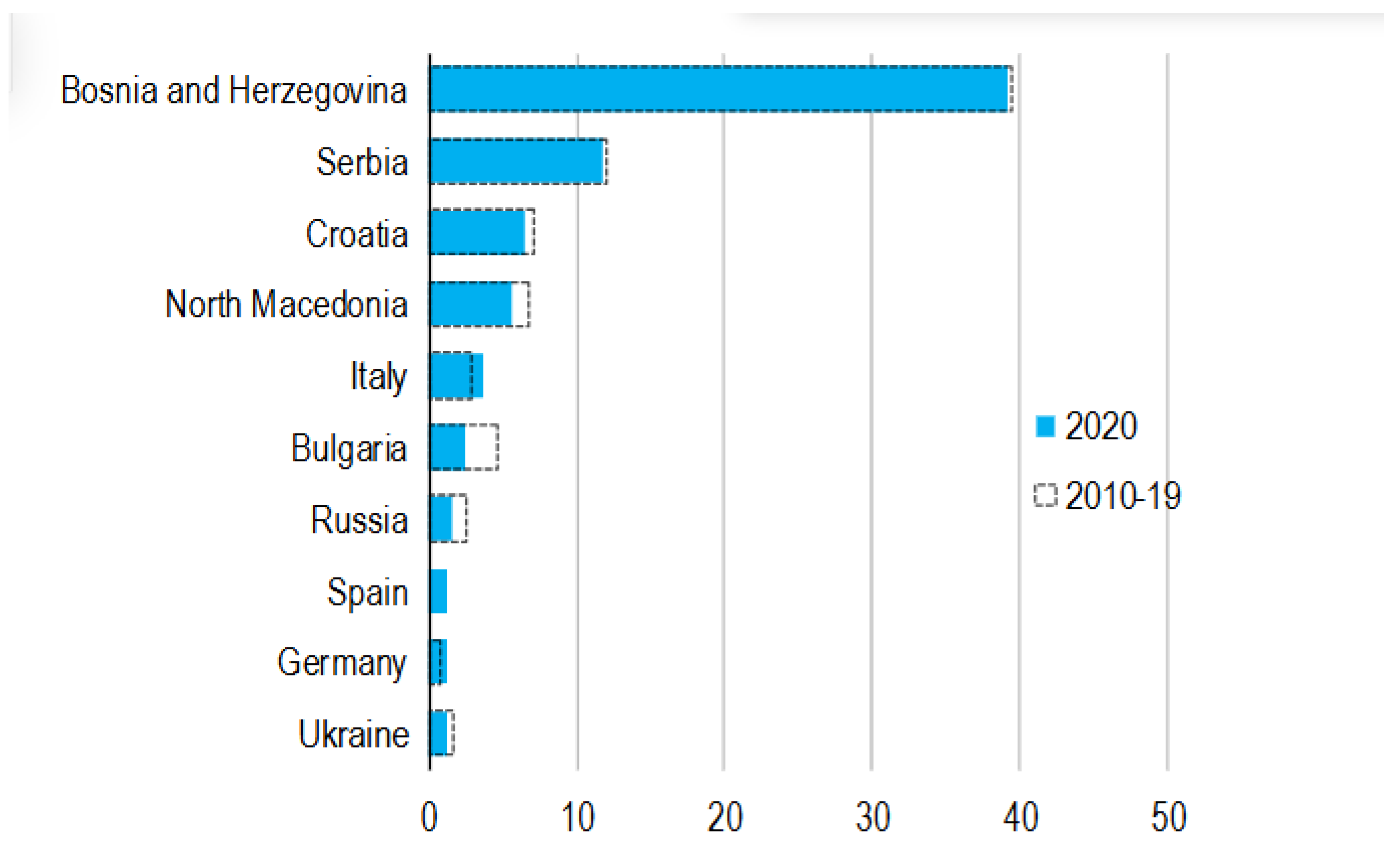

The figure shows the percentage distribution of total foreign population inflows to Slovenia, comparing data for 2020 with the average for 2010–2019

28. Bosnia and Herzegovina consistently dominate as the largest source of immigrants, accounting for nearly 40% of foreign inflows in both periods

29. Serbia ranks second, followed by Croatia, North Macedonia, and Italy, each contributing a smaller but noticeable share. Other countries, such as Bulgaria, Russia, Spain, Germany, and Ukraine which are developing countries.

Figure 7.

% of total inflows of foreign population in Slovenia. Source: Macedonia (2022).

Figure 7.

% of total inflows of foreign population in Slovenia. Source: Macedonia (2022).

Table 2.

Asylum Applications Slovenia in 2021 Source: Macedonia (2022).

Table 2.

Asylum Applications Slovenia in 2021 Source: Macedonia (2022).

| Year |

2021 |

| Total First Asylum Applicants |

5,200 (+50.6% compared to 2020) |

| Top Countries of Origin |

Afghanistan: 2,600 |

|

Pakistan: 500 |

|

Iran: 300 |

In 2021, the number

of first-time asylum seekers rose significantly by over 50% to approximately 5,200 people

30. The largest groups of

applicants came from Afghanistan with 2,600 people, Pakistan with 500 people, and Iran with 300 people

31. Since 2020, there has been a huge rise in applicants from Afghanistan, nearly 1,900 more

32.

There has been a steady increase in the number of immigrants. In 2023, Slovenia recorded a total of 33,939 immigrants from abroad

33.

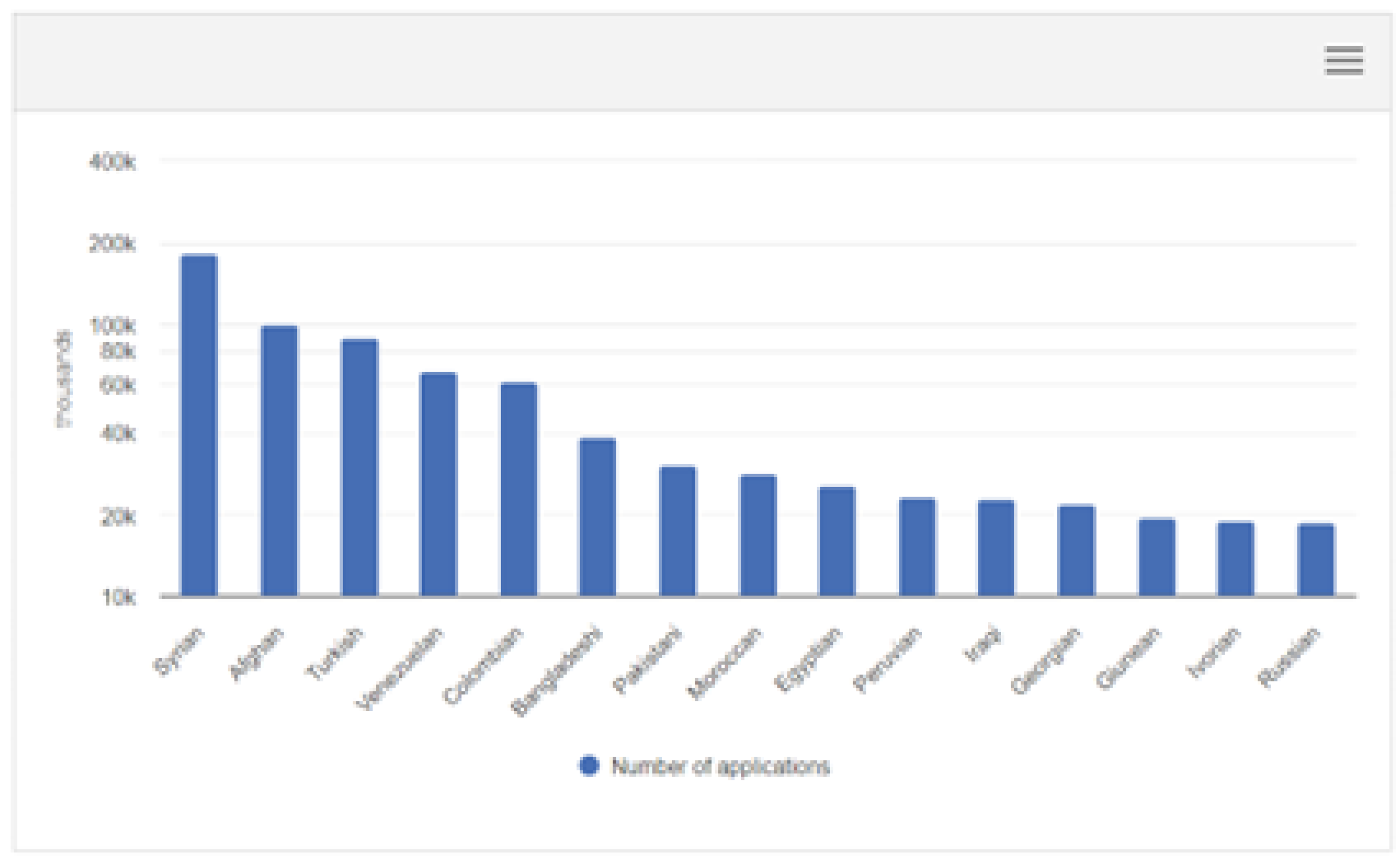

Figure 8.

Number of applications. Source: SiStat, 2023.

Figure 8.

Number of applications. Source: SiStat, 2023.

As a member of the EU, Slovenia complies with directives and agreements such as the Dublin Regulation

34, which allocates responsibility for asylum applications, and the Blue Card Directive, aimed at attracting highly skilled workers

35. Additionally, the Schengen Agreement facilitates free movement across EU borders, and the Returns Directive establishes common standards for handling irregular migrants

36 37. In the past, Slovenia functioned within the framework of the common state of Yugoslavia, in which the inhabitants of six republics and two autonomous regions enjoyed equality, rights, and fundamental freedoms, as laid down in the common constitution. This equality also included equal opportunities in employment and education for all nations and nationalities in Yugoslavia. After the disintegration of Yugoslavia and Slovenia's independence, there were specific social and political changes that shaped Slovenia's migration policy in a way that is not entirely comparable to the situation in other EU member states.

Immigration from the republics of the former Yugoslavia has been key to Slovenia's demographic and socio-economic development over the last fifty years. Even after Slovenia's independence, the direction of migration flows between Slovenia and the former Yugoslav republics did not change significantly, as many people from these republics became citizens of the Republic of Slovenia. Even today, they attract relatives, students, and friends who migrate to Slovenia for professional, educational, and personal reasons. Slovenia continues to be an attractive destination for people from the former Yugoslavia, which is due to the high regard in which Slovenia is held by the inhabitants of these countries.

Citizens and immigrants from other republics of the former common country enjoy the same opportunities for residence, employment, education, and activity throughout Slovenia, which contributes to tolerant and harmonious coexistence. Cultural affinity, common customs, linguistic similarities (Slovenian is the official language in Slovenia), and, to some extent, common religious affiliation are important factors that reduce the possibility of direct intolerance or hostility between the inhabitants.

The migration influx from economically underdeveloped regions introduces distinct challenges, particularly evident during the migration crisis following 2014.

7. Challenges of Migration in Slovenia and Europe After 2014

The extraction of raw materials and energy products and the creation of economic, market, financial, military, and other global inequalities are key factors that encourage migration and the movement of people to countries and cities where people see a greater chance of better living conditions. In recent years, the EU has faced the largest-ever influx of migrants, which member states described as a humanitarian and political crisis between 2014 and 2016. During this period, migrants from various countries suffering from political, military, or criminal oppression tried to reach Europe by land, sea, on foot, or by boat to obtain asylum. One of the main reasons for migration has been wars and conflicts in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and African countries, which is reflected in the statistics of forcibly displaced persons, which exceeded 60 million people at the end of 2014 — the highest number since the Second World War.

38

Refugee camps were set up in the Middle East, but without adequate conditions for survival, leading to mass migration across the Mediterranean and the Balkan route towards EU countries. EU members were not adequately prepared for the arrival of such a large number of migrants, triggering feelings of fear and insecurity among the population in the face of growing numbers of people from less economically developed areas.

In 2013, the European Union laid the foundations for a common asylum policy with the introduction of the Dublin Regulation

39. According to this regulation, the member state to which the applicant first enters is responsible for processing an asylum seeker. This significantly increased the procedures and financial burden, which led to difficulties in implementing the regulation, particularly in Greece and Italy, where the authorities often avoided the prescribed procedures due to the burden of the processes. As a result, the implementation of the Dublin Regulation

40 was temporarily suspended in August 2015.

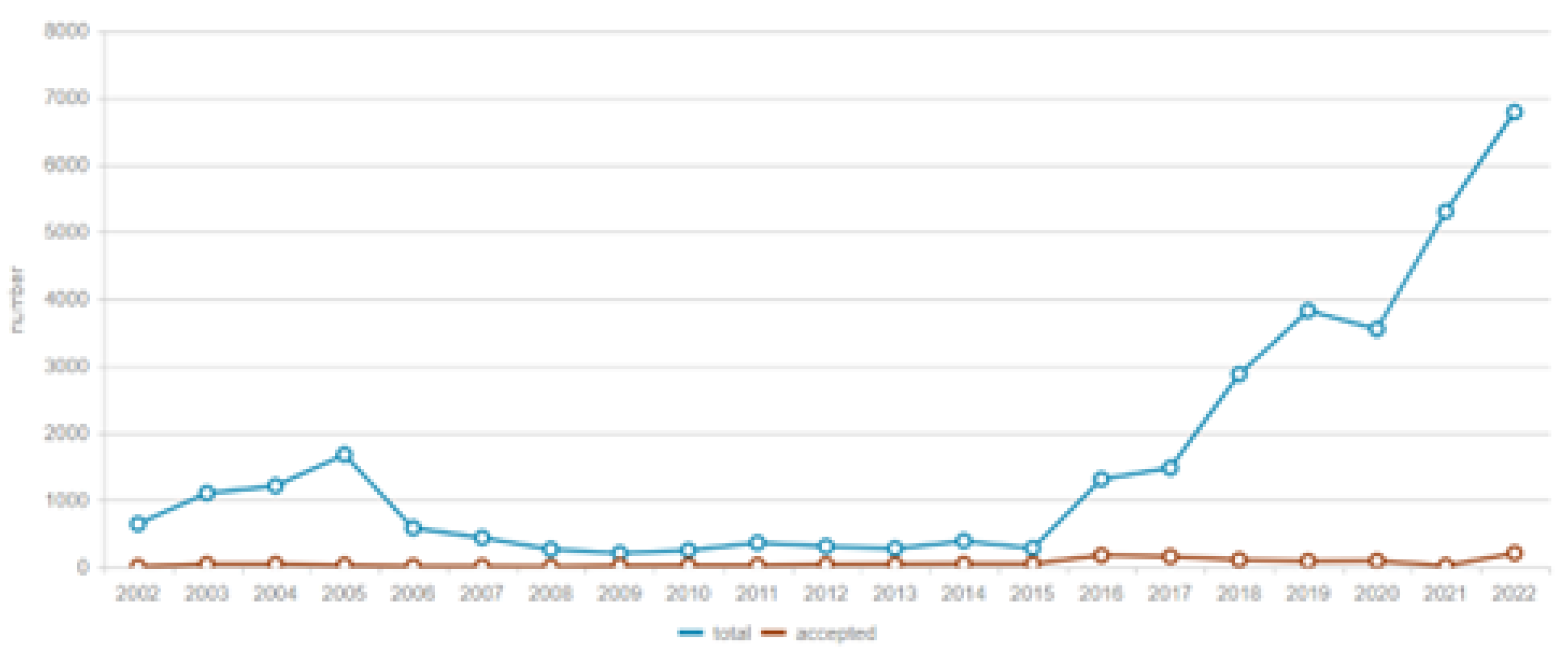

Slovenia, which is in a key geographical position on the Balkan route, was under great pressure during the refugee crisis, as most of the migration flow passed through its territory. Statistics show that between October 17, 2015, and January 25, 2016, 422,724 migrants crossed Slovenia, with Syrian nationals (45%) dominating, followed by Afghans (30%) and Iraqis (17%), while other nationalities accounted for 8%. Between 2015 and 2022, Slovenia granted asylum status to 46 people in 2015, 170 people in 2016, 152 people in 2017, 102 people in 2018, 85 people in 2019, 89 people in 2020, 17 people in 2021, and 203 people in 2022, as can be seen in the

Figure 11. In this period (2015-2022), 864 out of a total of 25,393 applications were approved, which corresponds to only 3.4% of all applications.

Figure 9.

Number of asylum applications – total and accepted (from year 2015 to 2022). Source: Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia 2024b.

Figure 9.

Number of asylum applications – total and accepted (from year 2015 to 2022). Source: Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia 2024b.

The European Union and Turkey concluded an agreement

41 to limit migration flows along the Balkan route, in which the COVID-19 pandemic played an important role, as it prevented the arrival of large numbers of refugees in Slovenia and other European regions due to the risk of the virus spreading. In this context, a sense of threat arose in society, which manifested itself in fear for personal safety and the security of property. There were cases of alienation of assets such as private vehicles (used by migrants for travel), food, and essential goods, which in certain cases directly threatened the population of the European Union. Such events have contributed to the development of a hostile and intolerant attitude towards migrants from economically less developed parts of the world.

The challenges brought by migration have broader societal implications, including the rise of discrimination and hatred, which warrant a deeper examination.

8. Discrimination and Hatred

Europe today is facing an alarming rise in hate speech and hate crime.

42 The study by Šabec and Pucelj (2019) examined hate speech targeting refugees and migrants from the Middle East and North Africa (2015-2016 migration wave), Muslims, and covered Muslim women in Slovenia. It investigated whether the influx of refugees and migrants had led to increased hate speech against pre-existing Muslim communities and whether hate speech against covered Muslim women had grown. According to the research by Šabec and Pucelj (2019), hate speech towards refugees, migrants, and Muslims was increasing, particularly due to the migration wave. A significant correlation existed between the perception of increased hate speech and recent migration trends. Hate speech was often found on forums, social networks, and media, with public discourse also playing a role.

When we look at the concept of discrimination, we try to create a definition based on historical experience, explaining that discrimination means unequal treatment of a person compared to others based on nationality, ethnicity, ethnic origin, gender, health status, disability, language, religious beliefs, age, sexual orientation, education, socio-economic status or other personal circumstances. The Constitution of the Republic of Slovenia explicitly prohibits such treatment, as it constitutes an act that threatens or restricts the exercise of human rights and fundamental freedoms of the individual. Nevertheless, it is often difficult to identify discriminatory practices, as we only speak of direct discrimination when a certain person is treated less favorably than another person in the same or a comparable situation due to certain personal circumstances such as ethnicity, religion, disability, age, or gender orientation.

43

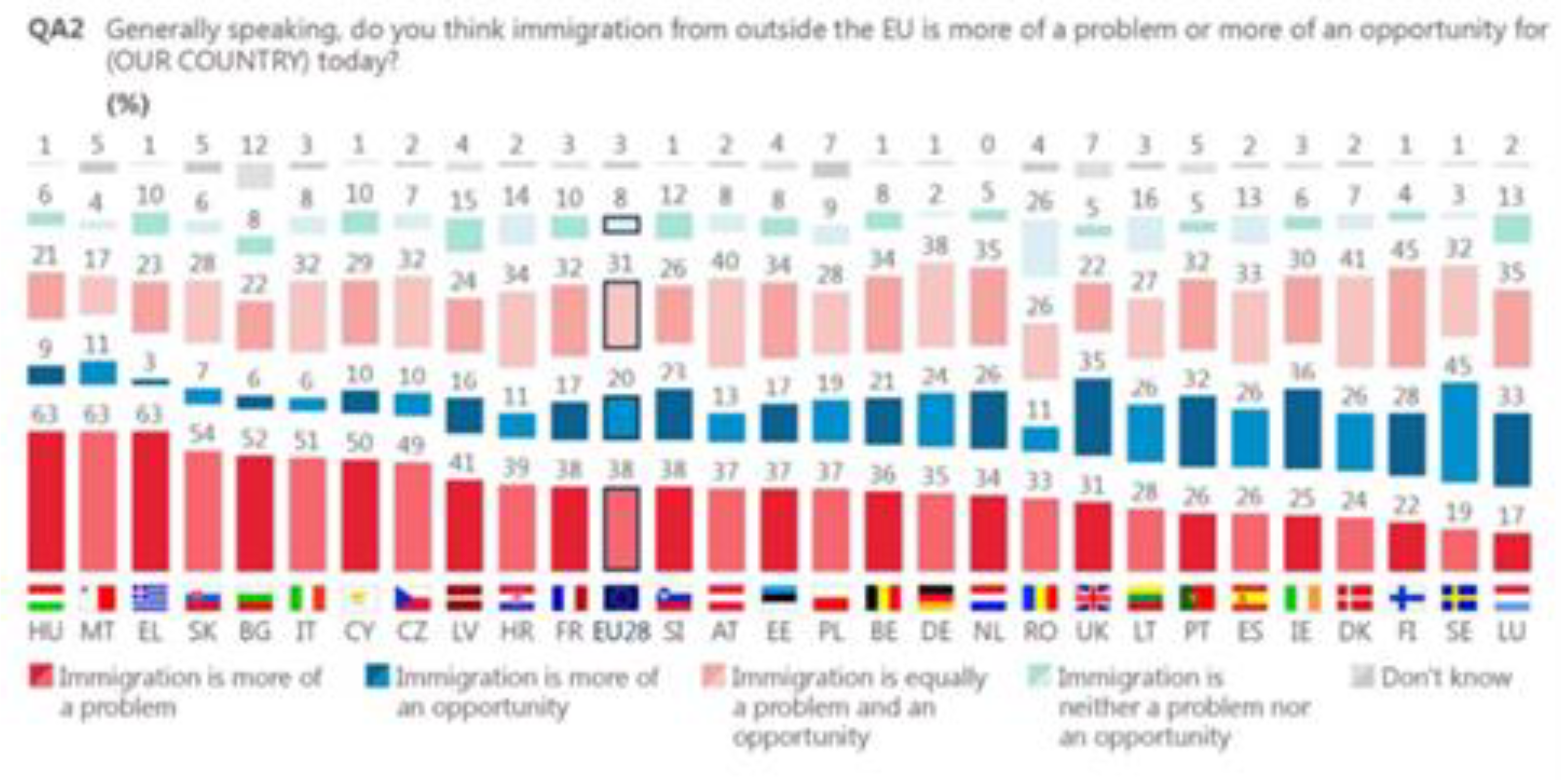

The Eurobarometer survey shows a gradual increase in discrimination over the years. While around 16% of respondents felt discriminated against in 2009, this figure rose to 21% in 2015

44. The following figure shows that a negative perception of migrants still prevails in some European countries.

Figure 10.

Attitude towards migration. Source: Eyes on Europe 2020.

Figure 10.

Attitude towards migration. Source: Eyes on Europe 2020.

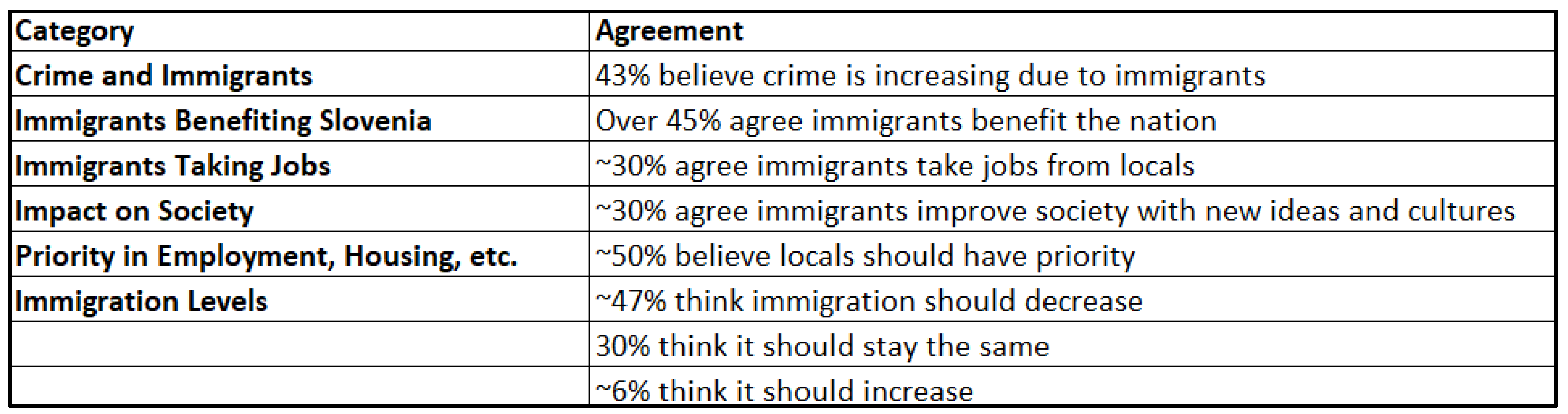

The results of the survey, which was conducted by the authors Medvešek, Bešter, and Pirc

45, show that respondents in Slovenia generally have cautious views on immigration and immigration policy. The majority (59.6%) are in favor of stricter immigration conditions, while 65% believe that Slovenia's demographic and economic needs do not justify increased immigration. In addition, 58.1% were against greater openness towards refugees. Although most were in favor of the restrictions, they recognized that immigrants perform important tasks in some sectors of the economy. More than half of respondents favored a selective immigration policy that focuses on recruiting highly skilled and well-educated individuals. In particular, 66.7% believe that immigrants abuse the social welfare system, 44.2% associate immigration with increased crime and 44.4% believe that immigrants undermine Slovenian culture. Similar results can also be seen in the Eyes of Europe survey. More European citizens agree than disagree with the statement that immigrants are a burden on the social system (56 agree overall, 38 disagree overall) and that they exacerbate the crime problem in their countries (55 agree overall, 45 disagree overall).

46

Figure 11.

Public Opinions on Immigration in Slovenia. Source: (Public Opinion and Mass Communication Research Centre 2024).

Figure 11.

Public Opinions on Immigration in Slovenia. Source: (Public Opinion and Mass Communication Research Centre 2024).

The results of the above-mentioned research are in line with the research of Zupančič and Premec, as they have shown that the inhabitants of Slovenian border areas are relatively hostile towards migrants and that they are generally afraid of migration in various aspects. They also found that the approval of the border population was higher in the past (e.g. in 2015, when migrants started to come to Slovenia en masse) than on the day of the survey, when a larger number of migrants had already been coming to this area for five years.

47. The above results contradict the findings of contact theory, which assumes that, under the right conditions, greater proximity and regular contact between different ethnic groups or interpersonal interactions between the majority population and immigrants can effectively reduce the majority population's prejudices against immigrants and promote positive attitudes towards diversity.

48. The above findings therefore belong in the context of group threat theory, which assumes that the negative opinions of the population are the result of the perceived threat they see in the presence of immigrants and/or permissive integration policies that allow immigrants access to resources.

49. Dominant groups therefore have the power to influence legislation and law enforcement to advance their interests, especially when those interests appear to be threatened

50.

The research analyses whose rights and fundamental freedoms are at risk of being violated in connection with migration. It considers both citizens of Slovenia and other EU Member States, whose personal rights and freedoms are guaranteed by constitutional and international law, as well as persons from economically less developed countries seeking similar protection. The critical question arises as to whether measures targeting migrants constitute indirect discrimination and how such discrimination can be determined.

Slovenian legislation defines indirect discrimination as a situation in which a neutral act, measure, or procedure results in a person being placed in an unfavorable position due to personal circumstances such as ethnicity, religion, disability, age, or sexual orientation. However, the law allows for exceptions where such measures are objectively justified by the legitimate purpose of the public authority or official.

51. This definition emphasizes the need for a nuanced assessment of whether certain measures, seemingly neutral in their intention, have a disproportionate negative impact on migrants. Slovenian law also recognizes harassment as a form of discrimination

52, which it defines as unwanted conduct based on personal circumstances that creates an intimidating, hostile, or humiliating environment and affects a person's dignity. In the present case, it is not clear who the harassment concerns, as the presence of foreigners from less developed countries, can be a burden for the citizens of Slovenia and the EU, which provide material support to immigrants with public funds, often higher than the minimum social support provided for citizens. This raises the issue of reverse discrimination, as Slovenian citizens may feel unequally treated compared to foreigners using the existing support systems.

Slovenian law also recognizes harassment as a form of discrimination, which it defines as unwanted conduct that is based on a personal circumstance, creates an intimidating, hostile, or humiliating environment, and insults the dignity of the person. In this case, the question of who is the victim of such behavior remains open: whether it is citizens of Slovenia and the EU who feel insecure about their social and economic security due to the presence of foreigners from less developed countries, or foreigners who may benefit more from the existing social support systems than citizens.

In the treatment of migrants, a behavior that the law defines as victimization can be observed in the relations between officials, non-governmental organizations, and the public. It is a behavior that exposes individuals or official institutions when they point out discrimination by officials or others, either on their own behalf or on behalf of others, thereby risking negative consequences.

Defining the concept of hatred in a modern context is a challenge. Hatred can be understood as a personal or group-specific state arising from certain historical experiences or a sense of current threat. It is an intense negative emotion that can range from frustration and disappointment to deep loathing and hatred. In this research, we look for the causes of hostility towards migrants among Slovenian and European citizens. From a philosophical point of view, hatred encompasses the whole spectrum of hostile feelings that can be triggered by various factors, such as the feeling of disturbance caused by the presence of others in our environment, the threat to one's way of life or values, and the loss of a sense of security and belonging.

Milivojević defines hate as a phenomenon that needs a trigger and a context in which people are emotionally or financially dependent, with the triggers placing the individual in a powerless and vulnerable position.

53 In our research context, it is possible to recognize the role of migration in Slovenian society as a trigger of hatred, whereby the intrusion of migrants into the social and physical environment of residents - their property, peace of life, jobs, etc. - creates a sense of threat and abuse among residents. This concerns various perceptions of negative consequences, such as environmental pollution, threats to personal safety, and violations of public order and peace, whereby migration can threaten the sense of autonomy and independence of Slovenian citizens. Cultural and linguistic differences and a different norm of behavior create a sense of vague mutual respect and security, which in turn raises questions that voters address to the power structures.

Often, armed conflicts and the restriction of trade flows trigger hatred towards certain nations, states, or confederations. In the context of the war between Russia and Ukraine, for example, a dominant negative connotation about Russia and the Russian nation can also be observed in Slovenia, while support is directed towards Ukraine and the Ukrainian people, albeit often without a full understanding of the complexity of the conflict itself.

The dominant power of large countries and confederations of states is evident in their control over raw materials, commodity flows, and economic and military power, which often translates into the spread of hatred, market monopolies, wars, and in some cases even genocide. These factors have a significant impact on the perceptions of individuals, who associate their beliefs with the attitudes of like-minded people, thereby reinforcing a sense of group affiliation and hostility towards certain groups.

Workers from Balkan countries like Bosnia came to Slovenia during socialism to work in heavy industries (Kuzmanić, 2000). This caused resentment as local workers saw them as competition for jobs. Having so many immigrant workers in places like Jesenice and Velenje led to economic and social tensions (Kuzmanić, 2000). Some Slovenians see foreign products and cultural influences as weakening their unique Slovenian identity (Kuzmanić, 2000). The importing of outside goods is a sign for some that Slovenia is losing its own culture and independence. This has helped fuel xenophobic or anti-foreigner attitudes.

According to the Eurobarometer 100 survey, in Slovenia, millennials aged 24-39 now have stronger anti-immigration views than even baby boomers aged 58-76 (Clark & Duncan, 2024). 74% of millennials in Slovenia feel negatively about immigration from outside the European Union

54. This is compared to 70% of baby boomers and 73% of those aged 40-57

55. Furthermore, 35% of millennials say they have very negative feelings about immigration

56. This is a higher percentage than the 31% of baby boomers with very negative views. This suggests that younger generations in Slovenia may hold more extreme anti-immigration positions compared to older cohorts. Surprisingly, millennials are even more skeptical of immigration than baby boomers, who one might expect to be more set in their ways.

Ostro

57 describes the experiences of several refugees and migrants trying to seek asylum in Slovenia and Croatia. In many cases, the police violence described includes beatings, theft of belongings, and dropping people off far from the border. The refugees assert they have a right to apply for asylum but are ignored.

According to Bajt

58 while migration for work is significant, particularly in sectors like construction, it is rarely recognized positively. Migrant workers are sometimes viewed as "third-class citizens," reflecting discriminatory attitudes. Migrants are often portrayed in media and political rhetoric as undermining economic stability by "taking jobs" or straining welfare systems. This depiction fuels xenophobia and justifies stricter immigration controls. Political and media narratives often exaggerate migrants' economic impacts, emphasizing competition for jobs and resources, which influences public opinion and policy toward more restrictive measures

59.

Summary

The following table summarizes the factors influencing hate and discrimination as discussed in the present research:

| Category |

Key Factors |

| Economic Factors |

- Labor shortages driving migration |

| |

- Dependency on BRICS for raw materials |

| |

- Perceived job competition |

| Social and Cultural Dynamics |

- Threats to cultural identity |

| |

- Misinformation about welfare abuse |

| |

- Stereotypes and xenophobia |

| Political and Legal Factors |

- Migration policies (e.g., Dublin Regulation, EU Blue Card) |

| |

- Populist anti-immigration rhetoric |

| Historical and Migration Patterns |

- Post-WWII reconstruction |

| |

- Colonial legacies |

| |

- Refugee crises from conflict zones |

| Media and Public Discourse |

- Social media amplifying negative sentiment |

| |

- Politically driven anti-migrant narratives |

| Integration and Perception |

- Perceived competition for resources |

| |

- Group threat theory vs. contact theory |

| |

- Integration challenges |

9. Conclusions

The research analyzed the impact of trade flows, wars, and migration on the rise of hate and discrimination in Slovenia and the European Union. The results show a complex relationship between economic interests, social dynamics, and the perceived cultural influence of migrants on the native population. The research question of whether migration flows and changing commodity flows contribute to an increase in hostile feelings was confirmed by the analysis, which showed that economic inequality and cultural differences fuel intolerance and hatred under certain circumstances. Far-reaching economic changes and an increasing presence of migrants contribute to the perception of threat, which can manifest itself in the form of discriminatory practices and strained relationships.

The research question – how changing flows of goods and people contribute to the rise of hate and discrimination in Slovenia and the EU – is answered with findings suggesting that economic integration and labor migration contribute to complex social images despite economic advantages in areas with labor shortages. Economic pressures, cultural diversity, and increased competition for resources in receiving countries increase the sense of threat and lead to polarized views on migration.

In the research, we asked ourselves about the possible intolerance of Slovenians and other European citizens towards migrants, especially those from economically less developed countries. We have linked the question of whether the protection of one's interests and the level of prosperity achieved is an expression of hatred or discrimination with the analysis of broader differences in development between nations and countries, which often give rise to a desire to improve one's living conditions. In this case, economically developed countries are seen as the "promised land" that attracts migration from less developed regions, which can be the basis for various forms of hatred and discrimination against immigrants. The results of the survey on the perception of migrants in Slovenia and the EU are also in line with the theory of dependency and the theory of world systems. The native population often perceives migrants as competition in the labor market, which reinforces hostile feelings and encourages discrimination. As part of the EU, Slovenia benefits from the free movement of goods and labor, which promotes economic growth, but at the same time fosters the development of prejudices and social tensions due to the presence of migrants who come from economically less developed countries.

As immigration and labor migration have increased, reported hate crimes have risen as well. This suggests there could be a connection where more migration leads to more tension and incidents of hate speech, possibly due to perceptions of competition over jobs and resources. Trade volumes have consistently grown over time, which might indirectly impact hate crimes if economic uncertainties or fears about globalization are fueling divisions in society. However, without deeper regional data directly tying specific trade events to hate crimes, the relationship remains speculative. The proportion of migrants who come to work is growing steadily as a percentage of all new immigrants. This corresponds directly to economic demands and could be exacerbating local worries about job competition, potentially inflaming hateful rhetoric. The hypothesis that trade and migration influence hate speech in Slovenia is preliminarily supported by the observed patterns. However, migration appears to have a stronger immediate connection to hate crimes versus trade.

Although the research findings are important, some limitations of the present research should be recognized. It is mainly based on secondary sources, which may limit deeper insights into specific contexts, especially when considering more recent empirical data. Future research should include face-to-face surveys or interviews with the local population in the areas most affected by migration, as this would allow for a more detailed understanding of responses at the local level. Furthermore, it would be beneficial for further research to use a broader theoretical framework such as dependency theory and social identity theory to shed light on how economic roles and identity tensions contribute to perceived social divisions. Due to the specificities of the Slovenian setting and its relationship to migration, the findings may be difficult to generalize to the wider European setting. The analysis was limited to a specific period. By including a longer period, it could provide more holistic insights into the development and long-term consequences of migration flows.

Further research is needed to gain a deeper understanding of the impact of migration on hate and discrimination. We suggest that additional social and cultural factors, such as the level of integration, the impact of EU migration policies, and the role of the media in shaping public opinion, should be considered in future research. An in-depth study could also include a comparative analysis of neighboring countries, which would make it possible to compare the Slovenian experience of migration with the wider European context. To gain insight into the lived experiences of the population, future research could include interviews or surveys with native and migrant communities to understand their attitudes and challenges in adapting to demographic change. Future studies should focus on examining the role of digital media in influencing public perceptions of migrants and migration policy, as social media platforms have become primary channels for both the dissemination of information and misinformation.

By highlighting the economic interdependencies, cultural exchanges, and socio-political challenges of migration, the research emphasizes the need for policies that strike a balance between economic integration and social cohesion. By promoting mutual understanding within the EU, it would be possible to mitigate some of the negative effects of migration and support a more inclusive approach to economic and social policy development. Policies should focus on promoting community engagement programs that encourage positive interactions between natives and immigrants. Awareness campaigns could help demystify common misconceptions about the impact of migration on local labor markets and culture.

| 1 |

Examples of these favorable conditions include, for example, an appropriate relationship between economic growth and employment opportunities, an appropriate relationship between economic development and access to education, an appropriate relationship between economic growth and health, an appropriate relationship between economic growth and environmental sustainability/social equality, and so on. |

| 2 |

Government of British Columbia 2023. |

| 3 |

Finnemore 1996, 89–97. |

| 4 |

Asia Society 2004. |

| 5 |

Karış 2020. |

| 6 |

Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1948. |

| 7 |

This is also confirmed by authors such as Heo and Tan 2001, Acemoglu et al. 2016 and Sima 2023. |

| 8 |

Business world 2024. |

| 9 |

Eurostat 2024. |

| 10 |

Brace 2004, 6. |

| 11 |

Barros Leal Farias 2023. |

| 12 |

ScienceDirect, Developed Country. |

| 13 |

Zelenika 2010. |

| 14 |

Intervista 2019. |

| 15 |

Rahmadan 2021. |

| 16 |

Ibid. |

| 17 |

Ibid. |

| 18 |

Ibid. |

| 19 |

Herander and Saavedra 2005; Felbermayr and Toubal 2012. |

| 20 |

Figueiredo Lima & Orefice 2020. |

| 21 |

The Slovenia Times 2024. |

| 22 |

Janša, Facebook post, December 17, 2022 |

| 23 |

Družina, "Volivci podprli vsa referendumska vprašanja, tudi o evtanaziji". |

| 24 |

Marozzi 2015. |

| 25 |

European Commission 2024a. |

| 26 |

Zupančič and Premec 2021, 53. |

| 27 |

European Council, n.d |

| 28 |

Macedonia 2022. |

| 29 |

Ibid. |

| 30 |

Macedonia 2022. |

| 31 |

Ibid. |

| 32 |

Ibid. |

| 33 |

SiStat 2023. |

| 34 |

Regulation (EU) No 604/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national or a stateless person (European Union 2013c). |

| 35 |

Davis 2020. |

| 36 |

GSC 2015; Wagner et al. 2024. |

| 37 |

We can point some EU directives and pact's as example of such compliency: a) New Pact on Migration and Asylum, adopted in 2024 (European Commission 2024c), b) Directive 2009/50/EC on the conditions of entry and residence of third-country nationals for the purpose of highly qualified employment, (commonly known as the "EU Blue Card" directive) (European Union 2009), c) Directive 2011/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2011 on standards for the qualification of third-country nationals or stateless persons as beneficiaries of international protection, for a uniform status for refugees or for persons eligible for subsidiary protection, and for the content of the protection granted (European Union 2011), d) Directive 2013/32/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection (European Union 2013a), e) Directive 2013/33/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 laying down standards for the reception of applicants for international protection (European Union 2013b). |

| 38 |

UNHCR 2015. |

| 39 |

Regulation (EU) No 604/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national or a stateless person (European Union 2013c). |

| 40 |

Ibid. |

| 41 |

European Council 2016. |

| 42 |

European Commission 2024b. |

| 43 |

Act on the Implementation of the Principle of Equal Treatment 2007. |

| 44 |

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, "Survey on the Perception and Experience of Discrimination in Slovenia". |

| 45 |

Medvešek, Bešter & Pirc 2022. |

| 46 |

Medvešek, Bešter & Pirc 2022. |

| 47 |

Zupančič and Premec 2021. |

| 48 |

Allport 1954; Medvešek, Bešter & Pirc 2022, 29–47. |

| 49 |

Medvešek, Bešter & Pirc 2022, 29–47. |

| 50 |

Vogel and Messner 2024. |

| 51 |

Protection Against Discrimination Act 2013. |

| 52 |

Ibid. |

| 53 |

Milivojević 2008. |

| 54 |

Clark & Duncan 2024. |

| 55 |

Ibid. |

| 56 |

Ibid. |

| 57 |

Ostro 2019. |

| 58 |

Bajt 2019. |

| 59 |

Bajt 2019. |

References

- Acemoglu, Daron, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James A. Robinson. "Democracy Does Cause Growth." Journal of Political Economy (2016). Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.bu.edu/econ/files/2019/05/Democracy-and-growth-JPE-Revised-November-15-2016.pdf.

- Act on the Implementation of the Principle of Equal Treatment (ZUNEO). Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, no. 93/07 – official consolidated text, 33/16 – ZVarD.

- Allport, Gordon W. The Nature of Prejudice. New York: Addison-Wesley, 1954.

- Asia Society. (n.d.). Amartya Sen: A more human theory of development. Retrieved from https://asiasociety.org/amartya-sen-more-human-theory-development.

- Bajt, V. (2019). The schengen border and the criminalization of migration in slovenia. Comparative Southeast European Studies, 67(3), 304–327.

- Barros Leal Farias. (2023). Barros Leal Farias, Deborah. "Unpacking the 'Developing' Country Classification: Origins and Hierarchies." Review of International Political Economy 31, no. 2 (2023): 651–73. [CrossRef]

- Brace, Laura. The Politics of Property: Labour, Freedom and Belonging. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-7486-1535-3.

- Business world "Just in Time, Methods to Increase Productivity." Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.poslovnisvet.si/podjetnistvo/metode-za-povecevanje-produktivnosti/.

- Clark, A., & Duncan, P. (2024, May 28). Young more anti-immigration than old in parts of Europe, polling shows. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2024/may/28/young-more-anti-immigration-than-old-in-parts-of-europe-polling-shows.

- Davis, K. (2020). The European Union’s Dublin Regulation and the Migrant Crisis. Wash. U. Global Stud. L. Rev., 19, 261.

- Družina. "Volivci podprli vsa referendumska vprašanja, tudi o evtanaziji." Accessed October 25, 2024. https://www.druzina.si/clanek/referendumi-trije-referendumi-stiri-vprasanja-v-zivo.

- EURES. "Labor Shortages and Surpluses in Europe." EURES - European Job Mobility Portal. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://eures.europa.eu/living-and-working/labour-shortages-and-surpluses-europe_en.

- European Commission. "Tackling Hatred in Society." Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://citizens.ec.europa.eu/tackling-hatred-society_en.

- European Commission. European Education Area, Quality Education, and Training for All: Uniform Education According to the Bologna Agreement of EU Members. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://education.ec.europa.eu/sl/education-levels/higher-education/inclusive-and-connected-higher-education/bologna-process.

- European Commission. "Pact on Migration and Asylum." Migration and Home Affairs. Accessed December 6, 2024. https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/migration-and-asylum/pact-migration-and-asylum_en.

- European Council. "EU-Turkey Statement, 18 March 2016." Accessed December 6, 2024. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/.

- European Council. "EU Blue Card: Attracting Talent in Various Fields and Professions of Individual Fields." Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/sl/infographics/eu-blue-card/.

- European Union. "Directive 2009/50/EC of the Council of 25 May 2009 on the Conditions of Entry and Residence of Third-Country Nationals for Highly Qualified Employment." Official Journal of the European Union L 155 (June 18, 2009): 17–29. Accessed December 6, 2024. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2009:155:0017:0029:en:PDF.

- European Union. "Directive 2011/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2011 on Standards for the Qualification of Third-Country Nationals or Stateless Persons as Beneficiaries of International Protection." Official Journal of the European Union L 337 (December 20, 2011): 9–26. Accessed December 6, 2024. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2011/95/oj.