Submitted:

21 December 2024

Posted:

23 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

We introduce ShapeBand, a new shape-changing wristband designed for exploring multisensory and interactive anxiety regulation with soft materials and physiological sensing. Our approach takes a core principle of self-help psychotherapeutic intervention, aiming to help users to recognize anxiety triggers and engage in regulation with attentional distraction. We conducted user-centered design activities to iteratively refine our design requirements and delve into users’ rich experiences, preferences and feelings. With ShapeBand, we explored bidirectional and dynamic interaction flow in anxiety regulation and subjective factors influencing its use. Our findings suggest that integrating both active and passive modulations can significantly enhance user engagement for effective anxiety intervention. This study provides valuable insights into the future design of tangible anxiety-regulation interfaces that can be tailored to subjective feelings and individual needs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- ShapeBand: a shape-changing wristband iteratively designed with a user-centered design approach for exploring multisensory and interactive anxiety regulation.

- Insights from a qualitative study into main design factors that affect anxiety regulation with both active and passive methods through the interface.

2. Related Work

2.1. Meditation, Mindfulness and Anxiety Regulation

2.2. Potential Benefits of Shape-Changing Interfaces for Anxiety Regulation

2.3. Fabrication of Shape Changing Wristband

3. ShapeBand: Design Approach

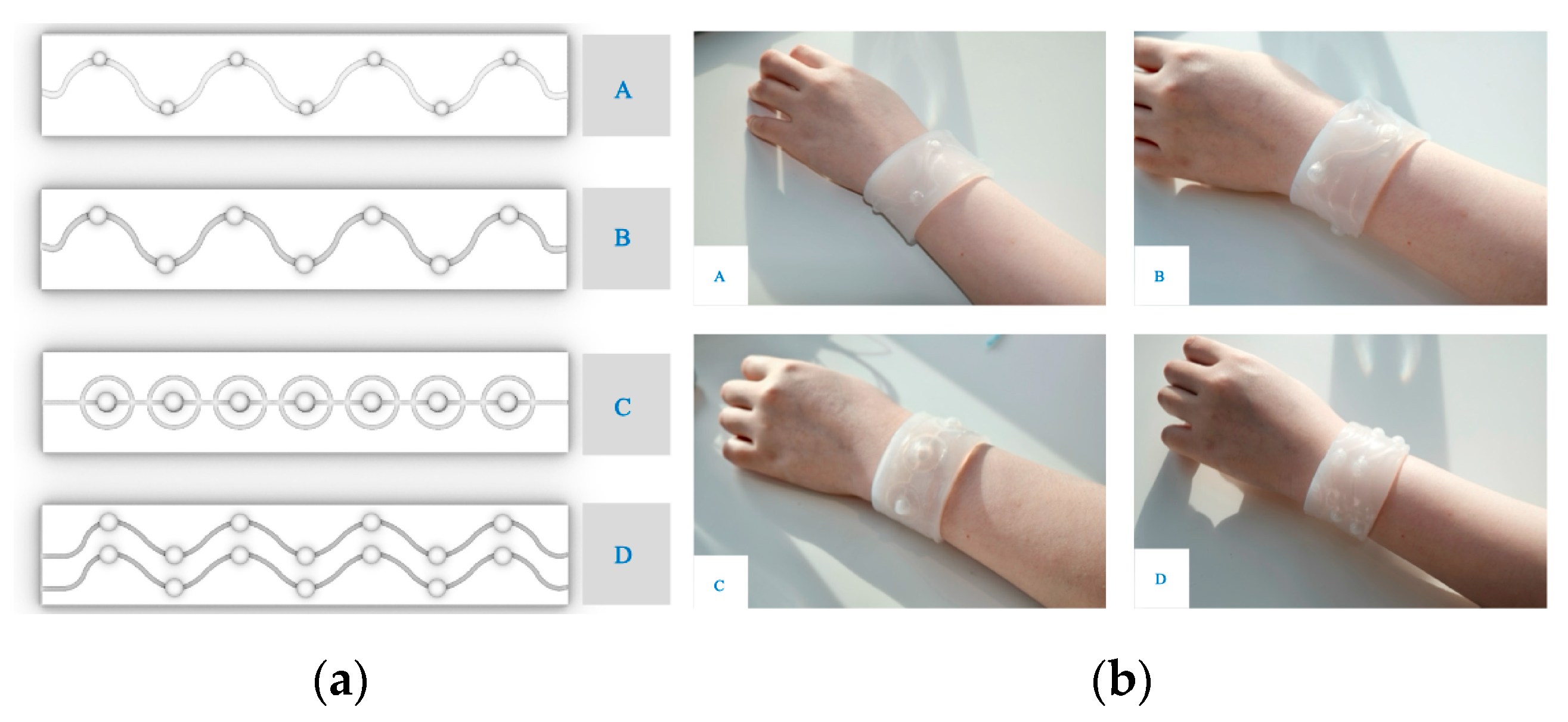

3.1. Silicone Wristband Fabrication

3.2. Design Workshop and Iteration

3.2.1. Design Workshop to Iterate the Design

3.2.2. Results

- Theme 1: The form changing of the air bubbles in the centre due to the pressing action provides haptic feedback.

- Theme 2: Applicability of different changing mechanisms for anxiety regulation wearable devices.

- Theme 3: Haptic feedback is obtained by deforming the shape-changing interface with different movements.

- Theme 4: Demonstrate different personal preferences when using shape-shifting wristbands.

3.2.3. Initial Design Phase Outcome.

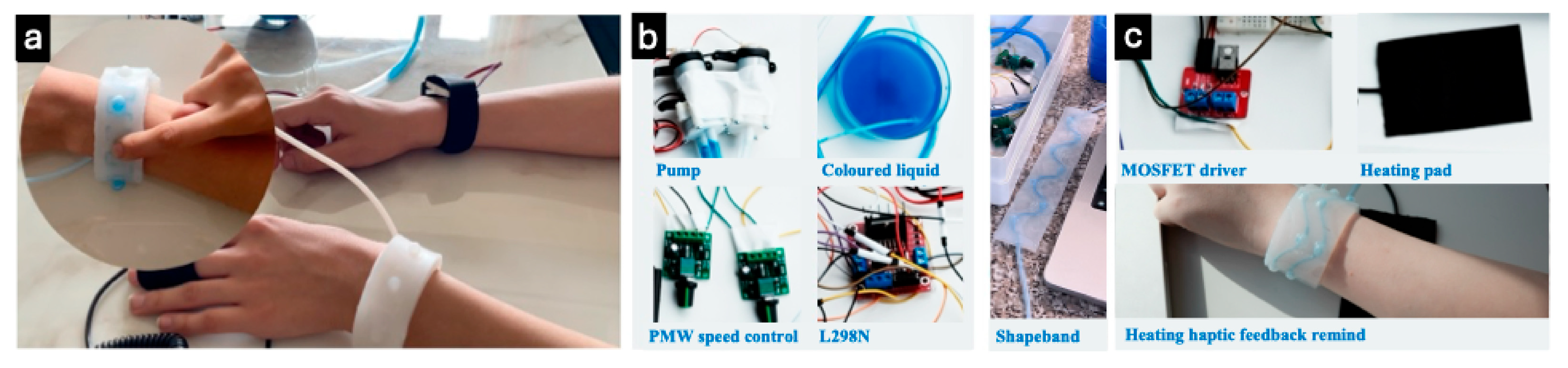

3.2.4. Final Design and Implementation

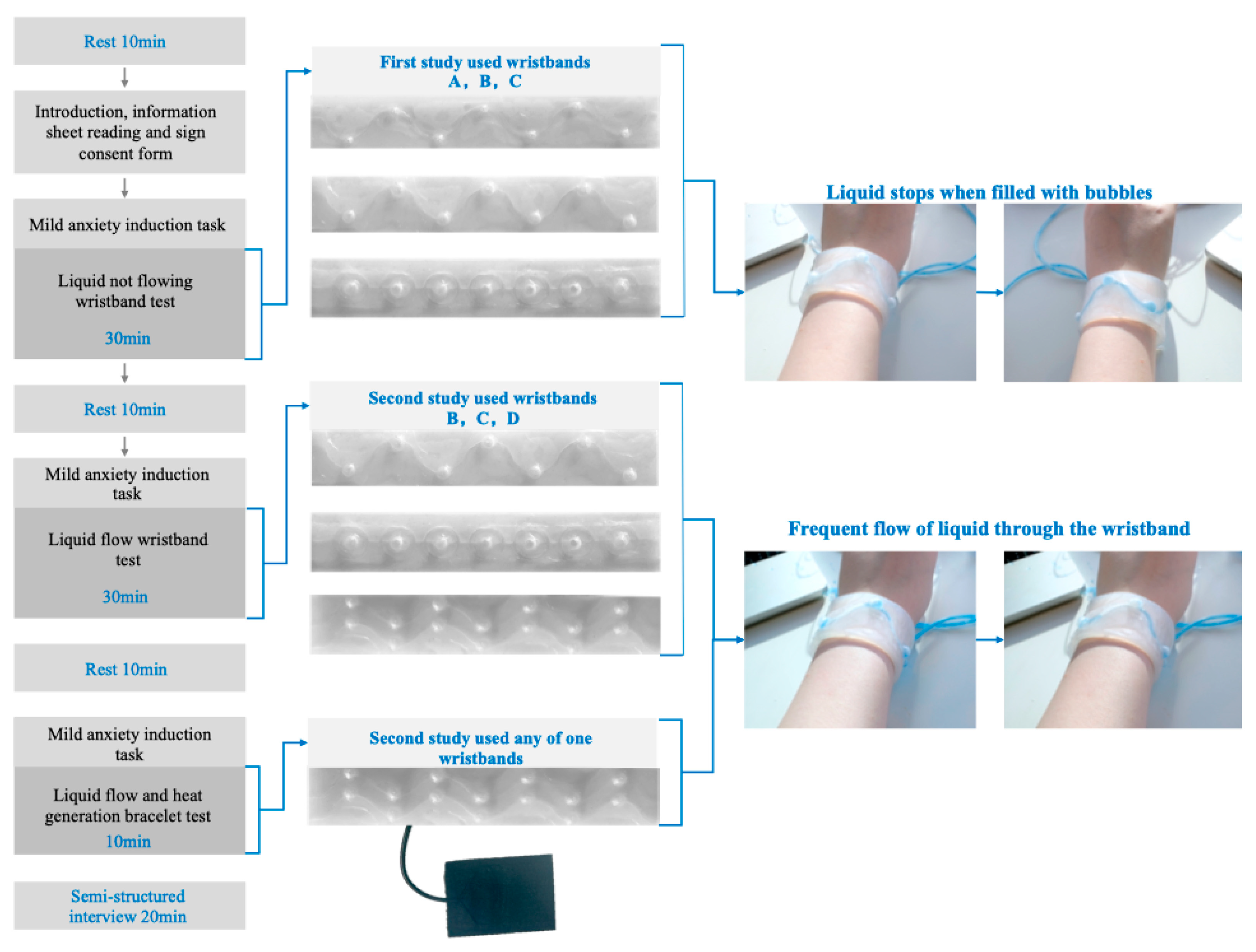

4. Diving into ShapeBand: Interviews

4.1. Interview Study

4.2. Data Colleaction and Analysis

5. Result

- Theme 1: Pros and cons of active and passive anxiety regulation methods.

- Theme 1.1: Active haptic feedback can help regulate anxiety through attentional distraction.

- Theme 1.2: Active haptic feedback is however limited by users’ intention, self-management, and the level of stimulus.

- Theme 1.3: Anxiety relief through passive distraction and respiratory modulation supported by visual feedback

- Theme 1.4: Passive attentional shifts are stimulated by a single stimulus, lacking guidance and being time-consuming.

- Theme 2: Roles of wristband information changes in unimodal feedback

- Theme 2.1: haptic feedback’s attentional distraction

- Theme 2.2: Visual Feedback and Timeliness of Anxiety Reminders

- Theme 2.3: Visual Design Variations and Their Impact on Anxiety Regulation

- Theme 3: Interaction effects employing both active and passive adjustment methods

- Theme 4: Multi-sensory channels of touch and vision influence the intensity of distracting stimuli and timely reminders.

6. Discussion

Future Work and Limitation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mukholil, M. KECEMASAN DALAM PROSES BELAJAR. Eksponen 2018, 8, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, O.J.; Krimsky, M.; Grillon, C. The Impact of Induced Anxiety on Response Inhibition. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013, 7. [CrossRef]

- Hale, A.S. ABC of Mental Health: Anxiety. BMJ 1997, 314, 1886–1886. [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H. Unraveling the Mysteries of Anxiety and Its Disorders from the Perspective of Emotion Theory. American Psychologist 2000, 55, 1247–1263. [CrossRef]

- Amstadter, A. Emotion Regulation and Anxiety Disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2008, 22, 211–221. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.M.; McElroy, S.L.; Mutasim, D.F.; Dwight, M.M.; Lamerson, C.L.; Morris, E.M. Characteristics of 34 Adults with Psychogenic Excoriation. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1998, 59, 509–514. [CrossRef]

- Eisner, L.R.; Johnson, S.L.; Carver, C.S. Positive Affect Regulation in Anxiety Disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 2009, 23, 645–649. [CrossRef]

- Bandelow, B.; Michaelis, S.; Wedekind, D. Generalized Anxiety Disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2017, 19. [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing Coping Strategies: A Theoretically Based Approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1989, 56, 267–283. [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, B.; Totterdell, P. Classifying Affect-Regulation Strategies. Cognition & Emotion 1999, 13, 277–303. [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, F.; Martucci, K.T.; Kraft, R.A.; McHaffie, J.G.; Coghill, R.C. Neural Correlates of Mindfulness Meditation-Related Anxiety Relief. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 2014, 9, 751–759. [CrossRef]

- Webb, T.L.; Miles, E.; Sheeran, P. Dealing with Feeling: A Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Strategies Derived from the Process Model of Emotion Regulation. Psychological Bulletin 2012, 138, 775–808. [CrossRef]

- Hashini Senaratne Detecting Temporal Phases of Anxiety in the Wild: Toward Continuously Adaptive Self-Regulation Technologies. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Murnane, E.L.; Cosley, D.; Chang, P.; Guha, S.; Frank, E.; Gay, G.; Matthews, M. Self-Monitoring Practices, Attitudes, and Needs of Individuals with Bipolar Disorder: Implications for the Design of Technologies to Manage Mental Health. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2016, 23, 477–484. [CrossRef]

- Qu, D.; Liu, D.; Cai, C.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, K.; Wei, Z.; Tan, J.; Cui, Z.; et al. Process Model of Emotion Regulation-Based Digital Intervention for Emotional Problems. Digital Health 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Moge, C., Wang, K. and Cho, Y. Shared user interfaces of physiological data: Systematic review of social biofeedback systems and contexts in hci. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2022, pp. 1-16.

- Cho, Y., Julier, S.J. and Bianchi-Berthouze, N. Instant stress: detection of perceived mental stress through smartphone photoplethysmography and thermal imaging. JMIR mental health 2019, 6(4), p.e10140. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Su, H.; Peng, Q.; Yang, Q.; Cheng, X. Exam Anxiety Induces Significant Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Increase in College Students. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension 2011, 33, 281–286. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J. and Cho, Y. iBVP Dataset: RGB-Thermal rPPG Dataset With High Resolution Signal Quality Labels. Electronics 2024, 13(7), p.1334. [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, P.; Eddie, D. Dynamic Processes in Regulation and Some Implications for Biofeedback and Biobehavioral Interventions. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2013, 38, 143–155. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. and Cho, Y. Exploring Artistic Visualization of Physiological Signals for Mindfulness and Relaxation: A Pilot Study. 2023, arXiv:2310.14343.

- Yeo, S.K.; Lee, W.K. The Relationship between Adolescents’ Academic Stress, Impulsivity, Anxiety, and Skin Picking Behavior. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 2017, 28, 111–114. [CrossRef]

- Seneviratne, S.; Hu, Y.; Nguyen, T.; Lan, G.; Khalifa, S.; Thilakarathna, K.; Hassan, M.; Seneviratne, A. A Survey of Wearable Devices and Challenges. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2017, 19, 2573–2620. [CrossRef]

- Appelboom, G.; Camacho, E.; Abraham, M.E.; Bruce, S.S.; Dumont, E.L.; Zacharia, B.E.; D’Amico, R.; Slomian, J.; Reginster, J.Y.; Bruyère, O.; et al. Smart Wearable Body Sensors for Patient Self-Assessment and Monitoring. Archives of Public Health 2014, 72. [CrossRef]

- Frederik Ølgaard Jensen; Sigurd Dalsgaard Pedersen; Pakanen, M. SuspenderMender - Designing for a Shared Management of Anxiety in Higher Education Context through a Pair of Wearables Simulating Physical Touch. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, K.; Cao, Y.; Girouard, A.; Loke, L. Breathing Scarf: Using a First-Person Research Method to Design a Wearable for Emotional Regulation. Sixteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction 2022. [CrossRef]

- MacLean, D.; Roseway, A.; Czerwinski, M. MoodWings. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments - PETRA ’13 2013. [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, V.A.; Armour, K.M. Young People’s Perspectives on and Experiences of Health-Related Social Media, Apps, and Wearable Health Devices. Social Sciences 2018, 7, 137. [CrossRef]

- Qamar, I.; Groh, R.; Holman, D.; Roudaut, A. HCI Meets Material Science: A Literature Review of Morphing Materials for the Design of Shape-Changing Interfaces. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Pedersen, E.W.; Petersen, M.G.; Hornbæk, K. Shape-Changing Interfaces. Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’12 2012. [CrossRef]

- Beltzer, M.L.; Ameko, M.K.; Daniel, K.E.; Daros, A.R.; Boukhechba, M.; Barnes, L.E.; Teachman, B.A. Building an Emotion Regulation Recommender Algorithm for Socially Anxious Individuals Using Contextual Bandits. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 2021, 61, 51–72. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Ahmad Khan, I.; Saleem, T. ANXIETY and EMOTIONAL REGULATION; The Professional Medical Journal 2019, 26. [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Antecedent- and Response-Focused Emotion Regulation: Divergent Consequences for Experience, Expression, and Physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1998, 74, 224–237. [CrossRef]

- OCHSNER, K.; GROSS, J. The Cognitive Control of Emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2005, 9, 242–249. [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Carlson, L.E.; Astin, J.A.; Freedman, B. Mechanisms of Mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2006, 62, 373–386. [CrossRef]

- Edenfield, T.M.; Saeed, S.A. An Update on Mindfulness Meditation as a Self-Help Treatment for Anxiety and Depression. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2012, 5, 131–141. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, C.B.; Bizarro, L. Effects of Focused Meditation on Difficulties in Emotion Regulation and Trait Anxiety. Psychology & Neuroscience 2015, 8, 350–365. [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, A.; Vine, V.; Klemanski, D.H.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. MINDFULNESS and EMOTION REGULATION in DEPRESSION and ANXIETY: COMMON and DISTINCT MECHANISMS of ACTION. Depression and Anxiety 2013, 30, 654–661. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Gómez, A.F. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Anxiety and Depression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2017, 40. [CrossRef]

- Haynes, A.C.; Lywood, A.; Crowe, E.M.; Fielding, J.L.; Rossiter, J.M.; Kent, C. A Calming Hug: Design and Validation of a Tactile Aid to Ease Anxiety. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0259838–e0259838. [CrossRef]

- McCaul, K.D.; Malott, J.M. Distraction and Coping with Pain. Psychological Bulletin 1984, 95, 516–533. [CrossRef]

- MacLean, K.E. Designing with Haptic Feedback. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/844146.

- Nakamura, T.; Yamamoto, A. Multi-Finger Electrostatic Passive Haptic Feedback on a Visual Display. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Helbig-Lang, S.; Petermann, F. Tolerate or Eliminate? A Systematic Review on the Effects of Safety Behavior across Anxiety Disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2010, 17, 218–233. [CrossRef]

- MacLean, K.E. Putting Haptics into the Ambience. IEEE Transactions on Haptics 2009, 2, 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y., Bianchi, A., Marquardt, N. and Bianchi-Berthouze, N. RealPen: Providing realism in handwriting tasks on touch surfaces using auditory-tactile feedback. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology 2016, pp. 195-205.

- Miri, P.; Flory, R.; Uusberg, A.; Uusberg, H.; Gross, J.J.; Isbister, K. HapLand. Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI EA ’17 2017. [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, M.; Mamaev, I.; Ditzen, B.; Sailer, U. Calming Effects of Touch in Human, Animal, and Robotic Interaction—Scientific State-of-The-Art and Technical Advances. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Galal, S.; Vyas, D.; Hackett, R.K.; Rogan, E.; Nguyen, C. Effectiveness of Music Interventions to Reduce Test Anxiety in Pharmacy Students. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 10. [CrossRef]

- KEELE, S.W.; W. TRAMMELL NEILL MECHANISMS of ATTENTION. Elsevier eBooks 1978, 3–47. [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C.D. The Effects of Divided Attention on Information Processing in Manual Tracking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 1976, 2, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Ley, R. The Modification of Breathing Behavior. Behavior Modification 1999, 23, 441–479. [CrossRef]

- Bentley, T.G.K.; D’Andrea-Penna, G.; Rakic, M.; Arce, N.; LaFaille, M.; Berman, R.; Cooley, K.; Sprimont, P. Breathing Practices for Stress and Anxiety Reduction: Conceptual Framework of Implementation Guidelines Based on a Systematic Review of the Published Literature. Brain Sciences 2023, 13, 1612. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-C.; Chen, J.-S.; Chang, K.-J.; Hsu, S.-C.; Lee, M.-S.; Hung, Y.-P. I − M − Breath: The Effect of Multimedia Biofeedback on Learning Abdominal Breath. Lecture notes in computer science 2011, 548–558. [CrossRef]

- Antti Pirhonen; Tuuri, K. Calm down – Exploiting Sensorimotor Entrainment in Breathing Regulation Application. Lecture notes in computer science 2011, 61–70. [CrossRef]

- Braendholt1, M.; Kluger2, D.; Varga4, S.; Heck5, D.; Gross2, J.; Allen1, M. Breathing in Waves: Understanding Respiratory-Brain Coupling as a Gradient of Predictive Oscillations.

- Wang, J.; Lu, J.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X. When Lights Can Breathe: Investigating the Influences of Breathing Lights on Users’ Emotion. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 13205. [CrossRef]

- Jerath, R.; Beveridge, C. Respiratory Rhythm, Autonomic Modulation, and the Spectrum of Emotions: The Future of Emotion Recognition and Modulation. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.Y.; Ishii, H. AmbienBeat. Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction 2020. [CrossRef]

- Höök, K. Affective Loop Experiences – What Are They? Lecture notes in computer science 2008, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Niiyama, R.; Ou, J.; Follmer, S.; Della Silva, C.; Ishii, H. PneUI. Proceedings of the 26th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and technology 2013. [CrossRef]

- Nakagaki, K.; Vink, L.; Counts, J.; Windham, D.; Leithinger, D.; Follmer, S.; Ishii, H. Materiable. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’16 2016. [CrossRef]

- Albraikan, A.; Hafidh, B.; El Saddik, A. IAware: A Real-Time Emotional Biofeedback System Based on Physiological Signals. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 78780–78789. [CrossRef]

- Apsite, I.; Biswas, A.; Li, Y.; Ionov, L. Microfabrication Using Shape-Transforming Soft Materials. Advanced Functional Materials 2020, 30, 1908028. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.; Zigelbaum, J. Shape-Changing Interfaces. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing 2010, 15, 161–173. [CrossRef]

- Ravindra Kempaiah; Nie, Z. From Nature to Synthetic Systems: Shape Transformation in Soft Materials. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2014, 2, 2357–2368. [CrossRef]

- Elango, N.; Faudzi, A.A.M. A Review Article: Investigations on Soft Materials for Soft Robot Manipulations. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2015, 80, 1027–1037. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Md. Najib Alam; Yewale, M.A.; Park, S. Robust Performance for Composites Using Silicone Rubber with Different Prospects for Wearable Electronics. Polymers for Advanced Technologies 2023, 35. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, S.; Markvicka, E.J.; Majidi, C.; Feinberg, A.W. 3D Printing Silicone Elastomer for Patient-Specific Wearable Pulse Oximeter. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2020, 9, 1901735. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J., Wang, K. and Cho, Y. PhysioKit: An Open-Source, Low-Cost Physiological Computing Toolkit for Single-and Multi-User Studies. Sensors 2023, 23(19), p.8244.

- Zhu, J.; Ji, L.; Liu, C. Heart Rate Variability Monitoring for Emotion and Disorders of Emotion. Physiological Measurement 2019, 40, 064004. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y., Julier, S.J., Marquardt, N. and Bianchi-Berthouze, N. Robust tracking of respiratory rate in high-dynamic range scenes using mobile thermal imaging. Biomedical optics express 2017, 8(10), pp.4480-4503.

- Cho, Y., Bianchi-Berthouze, N. and Julier, S.J. DeepBreath: Deep learning of breathing patterns for automatic stress recognition using low-cost thermal imaging in unconstrained settings. In 2017 Seventh international conference on affective computing and intelligent interaction (ACII), 2017, pp. 456-463.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.N.M.; Jamali, N.; Suhaimi, A.I.H. Exploring Gamification Design Elements for Mental Health Support. International Journal of Advanced Technology and Engineering Exploration 2021, 8, 114–125. [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.H.; Gevirtz, R.N.; Gharbo, R.S.; Thiam, M.A.; Ginsberg, J.P. Pilot Study on Reducing Symptoms of Anxiety with a Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Wearable and Remote Stress Management Coach. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2021. [CrossRef]

- Brule, E., Bailly, G., Brock, A., Valentin, F., Denis, G. and Jouffrais, C. MapSense: multi-sensory interactive maps for children living with visual impairments. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems 2016, pp. 445-457.

- Cho, Y. Rethinking eye-blink: Assessing task difficulty through physiological representation of spontaneous blinking. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 2021, pp. 1-12.

- Joshi, J., Agaian, S.S. and Cho, Y. FactorizePhys: Matrix Factorization for Multidimensional Attention in Remote Physiological Sensing. Advances in neural information processing systems 2024, 37.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).