Submitted:

25 December 2024

Posted:

26 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

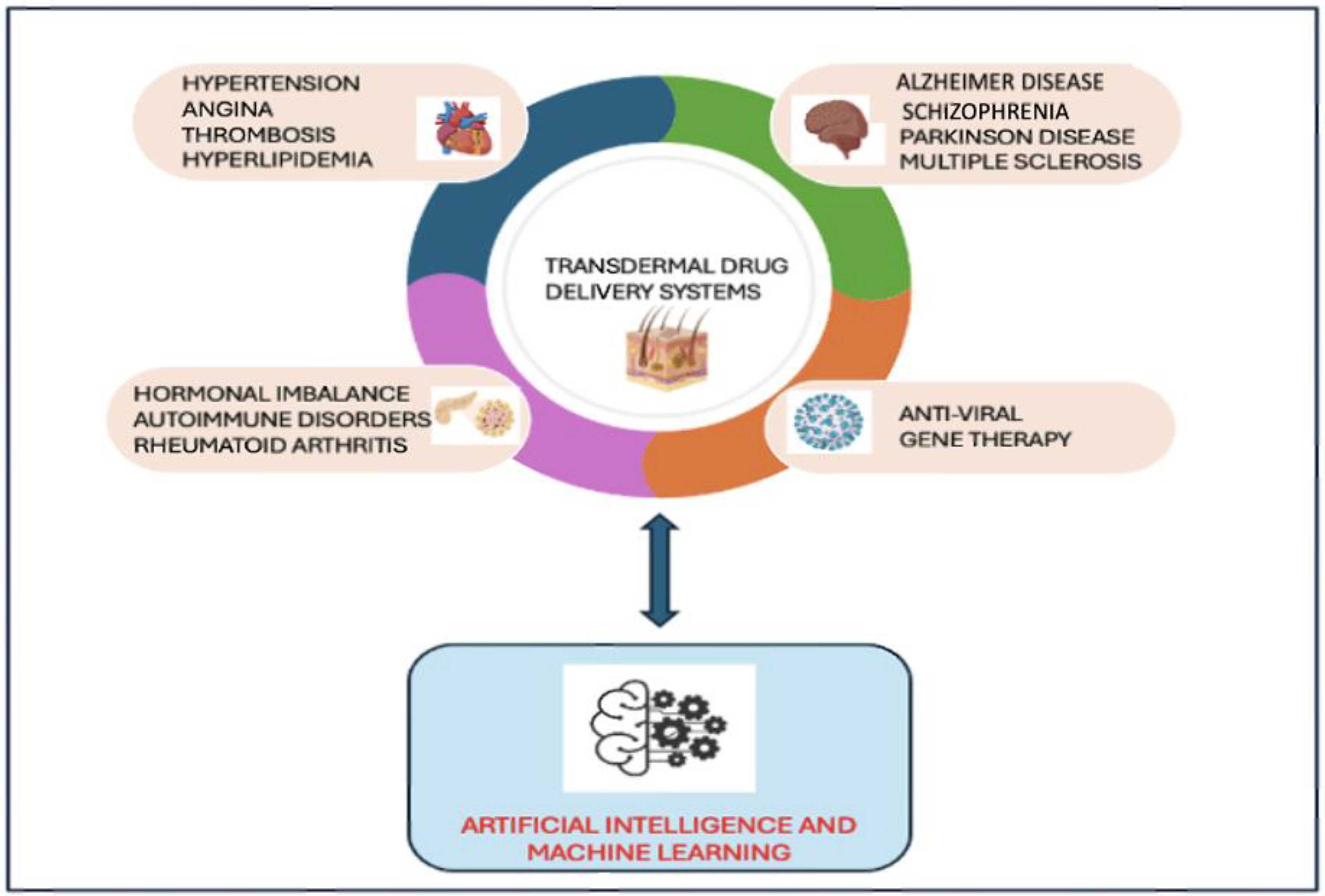

2. Emerging TDDS for the Treatment of Viral Infections and Other Vital Organ Disorders

2.1. TDDS for the Treatment of Viral Infections

2.2. TDDS for the Treatment of Central Nervous System (CNS) Disorders

2.3. TDDS for the Treatment of Cardiovascular (CV) Diseases

2.4. TDDS for the Treatment of Other Complications Such as Hormonal Imbalance and Autoimmune Disorders

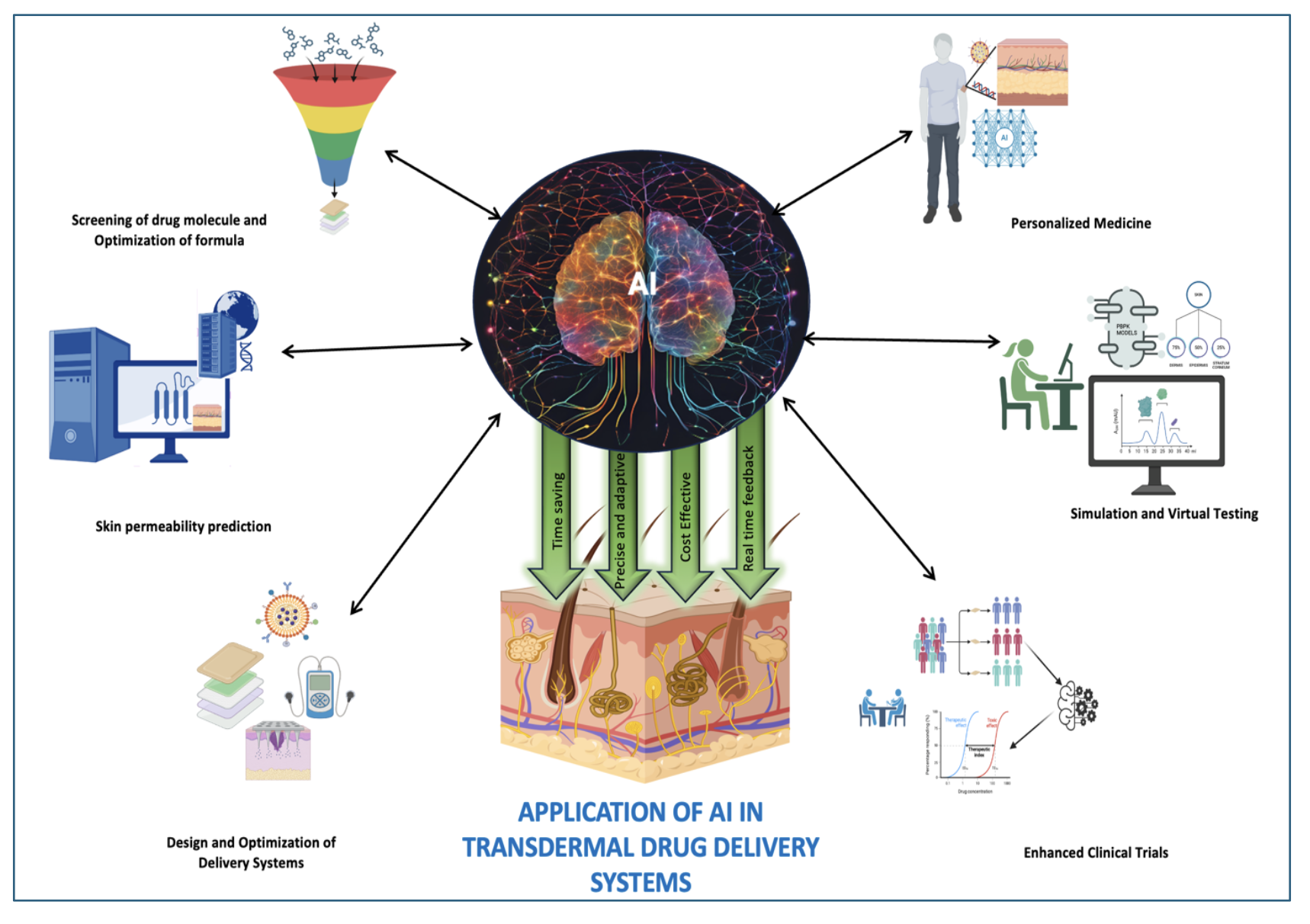

3. Application of AI in Various Stages of TDDS

3.1. Screening of Drug Molecules and Optimizing Formula

3.2. Skin Permeability Prediction

3.3. Design and Optimization of Delivery Systems

3.4. Personalized Medicine

3.5. Simulation and Virtual Testing

3.6. Efficiency in Clinical Trials

3.7. Addressing Challenges

4. Future Potential of AI in Overcoming Obstacles in TDDS

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkilani, A.Z.; Nasereddin, J.; Hamed, R.; Nimrawi, S.; Hussein, G.; Abo-Zour, H.; Donnelly, R.F. Beneath the skin: a review of current trends and future prospects of transdermal drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaid Alkilani, A.; McCrudden, M.T.; Donnelly, R.F. Transdermal drug delivery: innovative pharmaceutical developments based on disruption of the barrier properties of the stratum corneum. Pharmaceutics 2015, 7, 438–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.Y.; Kwon, M.; Choi, H.E.; Kim, K.S. Recent advances in transdermal drug delivery systems: A review. Biomaterials research 2021, 25, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Dubey, A.; Mishra, A.; Tiwari, P. Ethosomes: A Novel Approach in Transdermal Drug Delivery System. International journal of pharmacy & life sciences 2020, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Prausnitz, M.R. A practical assessment of transdermal drug delivery by skin electroporation. Advanced drug delivery reviews 1999, 35, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phatale, V.; Vaiphei, K.K.; Jha, S.; Patil, D.; Agrawal, M.; Alexander, A. Overcoming skin barriers through advanced transdermal drug delivery approaches. Journal of controlled release 2022, 351, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadon, D.; McCrudden, M.T.; Courtenay, A.J.; Donnelly, R.F. Enhancement strategies for transdermal drug delivery systems: Current trends and applications. Drug delivery and translational research 2021, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, M.; Diab, R.; Elaissari, A.; Fessi, H. Lipid nanocarriers as skin drug delivery systems: Properties, mechanisms of skin interactions and medical applications. International journal of pharmaceutics 2018, 535, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.A. Permeation enhancement and advanced strategies: a comprehensive review of improved topical drug delivery. International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science 2024, 6, 6691–6702. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, D.S.; Uppal, N.; Goyal, S.; Mehta, N.; Gupta, A.K. Permeation enhancer for TDDS from natural and synthetic sources: a review. J Biomed Pharm Res 2013, 2, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Matharoo, N.; Mohd, H.; Michniak-Kohn, B. Transferosomes as a transdermal drug delivery system: Dermal kinetics and recent developments. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2024, 16, e1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Chen, C.; Mi, X.; Tan, R.; Wang, J.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, R.; Chen, M.; Tan, W.-Q. Transdermal drug delivery system: current status and clinical application of microneedles. ACS Materials Letters 2024, 6, 801–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.; Mehta, P.; Arshad, M.; Kucuk, I.; Chang, M.; Ahmad, Z. Transdermal microneedles—a materials perspective. Aaps Pharmscitech 2020, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, S.; Singhvi, G. Microneedles-based drug delivery strategies: A breakthrough approach for the management of pain. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 155, 113717. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Maaden, K.; Jiskoot, W.; Bouwstra, J. Microneedle technologies for (trans) dermal drug and vaccine delivery. Journal of controlled release 2012, 161, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, P.; Jathar, S.; Kale, S.; Pal, K. Transdermal drug delivery system (TDDS)-a multifaceted approach for drug delivery. J Pharm Res 2014, 8, 1805–1835. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, K.T.; Gavitt, T.D.; Farrell, N.J.; Curry, E.J.; Mara, A.B.; Patel, A.; Brown, L.; Kilpatrick, S.; Piotrowska, R.; Mishra, N. Transdermal microneedles for the programmable burst release of multiple vaccine payloads. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2021, 5, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.R.; Munni, M.N.; Campbell, L.; Mostofa, G.; Dobson, L.; Shittu, M.; Pattanayek, S.K.; Uddin, M.J.; Das, D.B. Translation of polymeric microneedles for treatment of human diseases: Recent trends, Progress, and Challenges. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, B.Z.; Wang, Q.L.; Jin, X.; Guo, X.D. Fabrication of coated polymer microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2017, 265, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvi, I.A.; Madan, J.; Kaushik, D.; Sardana, S.; Pandey, R.S.; Ali, A. Comparative study of transfersomes, liposomes, and niosomes for topical delivery of 5-fluorouracil to skin cancer cells: preparation, characterization, in-vitro release, and cytotoxicity analysis. Anti-cancer drugs 2011, 22, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, R.; Mandru, A. Enhancement of skin permeability with thermal ablation techniques: concept to commercial products. Drug delivery and translational research 2021, 11, 817–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajwa, M.N.; Muta, K.; Malik, M.I.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Braun, S.A.; Homey, B.; Dengel, A.; Ahmed, S. Computer-aided diagnosis of skin diseases using deep neural networks. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ye, Z.; Gao, H.; Ouyang, D. Computational pharmaceutics-A new paradigm of drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 338, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, S.; Pathak, A.; Rao, N.R.; Nehra, S.; Asthana, A.; Sharma, V.; Katyal, G.; Bhardwaj, A.; Sharma, L.; Prakash, S. AI-assisted Formulation Design for Improved Drug Delivery and Bioavailability. Pakistan Heart Journal 2023, 56, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hamet, P.; Tremblay, J. Artificial intelligence in medicine. metabolism 2017, 69, S36–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mech, D.J.; Murugappan, S.; Buddhiraju, H.S.; Eranki, A.; Rengan, A.K.; Rizvi, M.S. AI on DDS for regenerative medicine. In Artificial Intelligence in Tissue and Organ Regeneration, Elsevier, 2023; pp 133-153.

- Elder, A.; Cappelli, M.O.D.; Ring, C.; Saedi, N. Artificial intelligence in cosmetic dermatology: An update on current trends. Clinics in Dermatology 2024, 42, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, P.; Atyabi, F.; Dinarvand, R. The significance of artificial intelligence in drug delivery system design. Advanced drug delivery reviews 2019, 151, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dara, S.; Dhamercherla, S.; Jadav, S.S.; Babu, C.M.; Ahsan, M.J. Machine learning in drug discovery: a review. Artificial intelligence review 2022, 55, 1947–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vora, L.K.; Gholap, A.D.; Jetha, K.; Thakur, R.R.S.; Solanki, H.K.; Chavda, V.P. Artificial intelligence in pharmaceutical technology and drug delivery design. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, R.M.; Hasan, H.E.; Hammad, A. Predictive modeling of skin permeability for molecules: Investigating FDA-approved drug permeability with various AI algorithms. PLOS Digital Health 2024, 3, e0000483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, D.R.; Luciano, F.C.; Anaya, B.J.; Ongoren, B.; Kara, A.; Molina, G.; Ramirez, B.I.; Sánchez-Guirales, S.A.; Simon, J.A.; Tomietto, G. Artificial intelligence (AI) applications in drug discovery and drug delivery: revolutionizing personalized medicine. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, O.; Matin, R.; Van der Schaar, M.; Bhayankaram, K.P.; Ranmuthu, C.; Islam, M.; Behiyat, D.; Boscott, R.; Calanzani, N.; Emery, J. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms for early detection of skin cancer in community and primary care settings: a systematic review. The Lancet Digital Health 2022, 4, e466–e476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antontsev, V.; Jagarapu, A.; Bundey, Y.; Hou, H.; Khotimchenko, M.; Walsh, J.; Varshney, J. A hybrid modeling approach for assessing mechanistic models of small molecule partitioning in vivo using a machine learning-integrated modeling platform. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 11143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaCount, T.D.; Zhang, Q.; Hao, J.; Ghosh, P.; Raney, S.G.; Talattof, A.; Kasting, G.B.; Li, S.K. Modeling temperature-dependent dermal absorption and clearance for transdermal and topical drug applications. The AAPS journal 2020, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbehzadeh, M.; Nopour, R.; Kazemi-Arpanahi, H. Developing an artificial neural network for detecting COVID-19 disease. Journal of education and health promotion 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, Y.; Qin, Z.; Yan, A. Classification of HIV-1 protease inhibitors by machine learning methods. ACS omega 2018, 3, 15837–15849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Cheng, C.-M. Transdermal drug delivery systems for fighting common viral infectious diseases. Drug delivery and translational research 2021, 11, 1498–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Machekposhti, S.A.; Narayan, R.J. Evolution of transdermal drug delivery devices and novel microneedle technologies: A historical perspective and review. JID Innovations 2023, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitley, R.J.; Roizman, B. Herpes simplex virus infections. The lancet 2001, 357, 1513–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konicke, K.; Olasz, E. Successful treatment of recalcitrant plantar warts with bleomycin and microneedling. Dermatologic Surgery 2016, 42, 1007–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshehri, S.; Hussain, A.; Altamimi, M.A.; Ramzan, M. In vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo studies of binary ethosomes for transdermal delivery of acyclovir: A comparative assessment. Journal of drug delivery science and technology 2021, 62, 102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghonemy, S.; Ibrahim Ali, M.; Ebrahim, H.M. The efficacy of microneedling alone vs its combination with 5-fluorouracil solution vs 5-fluorouracil intralesional injection in the treatment of plantar warts. Dermatologic Therapy 2020, 33, e14179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xiu, X.; Li, Z.; Su, R.; Li, X.; Ma, S.; Ma, F. Coated Porous Microneedles for Effective Intradermal Immunization with Split Influenza Vaccine. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2023, 9, 6880–6890. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Erdos, G.; Huang, S.; Kenniston, T.W.; Balmert, S.C.; Carey, C.D.; Raj, V.S.; Epperly, M.W.; Klimstra, W.B.; Haagmans, B.L. Microneedle array delivered recombinant coronavirus vaccines: Immunogenicity and rapid translational development. EBioMedicine 2020, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Meira, A.; Battistel, A.P.; Teixeira, H.F.; Volpato, N.M. Development of nanoemulsions containing penciclovir for herpes simplex treatment and a liquid chromatographic method to drug assessment in porcine skin layers. Drug Analytical Research 2020, 4, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Sharma, G.; Gupta, V.; Ratho, R.K.; Shishu; Katare, O. P. Enhanced acyclovir delivery using w/o type microemulsion: preclinical assessment of antiviral activity using murine model of zosteriform cutaneous HSV-1 infection. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology 2018, 46, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, G.; Kim, M.; Lee, Y.; Yang, H.; Seong, B.-L.; Jung, H. Egg microneedles for transdermal vaccination of inactivated influenza virus. Biomaterials Science 2024, 12, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyna, D.; Bejster, I.; Chadderdon, A.; Harteg, C.; Anjani, Q.K.; Sabri, A.H.B.; Brown, A.N.; Drusano, G.L.; Westover, J.; Tarbet, E.B. A five-day treatment course of zanamivir for the flu with a single, self-administered, painless microneedle array patch: Revolutionizing delivery of poorly membrane-permeable therapeutics. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2023, 641, 123081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinani, G.; Sessevmez, M.; Şenel, S. Applications of chitosan in prevention and treatment strategies of infectious diseases. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, S.; Hu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Gui, S.; Long, Y.; Wu, D.; He, N. Development and Assessment of Acyclovir Gel Plaster Containing Sponge Spicules. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 112, 2879–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, G.M.; Lhatoo, S.D. CNS adverse events associated with antiepileptic drugs. CNS drugs 2008, 22, 739–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gage, S.B.; Bégaud, B.; Bazin, F.; Verdoux, H.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Pérès, K.; Kurth, T.; Pariente, A. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia: prospective population based study. Bmj 2012, 345. [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani, A.H.; Levin, E.D. Cognitive effects of nicotine. Biological psychiatry 2001, 49, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quik, M. Smoking, nicotine and Parkinson's disease. Trends in neurosciences 2004, 27, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Pillay, V.; Choonara, Y.E. Advances in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Progress in neurobiology 2007, 81, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsterdam, J.D. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the safety and efficacy of selegiline transdermal system without dietary restrictions in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2003, 64, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indermun, S.; Luttge, R.; Choonara, Y.E.; Kumar, P.; Du Toit, L.C.; Modi, G.; Pillay, V. Current advances in the fabrication of microneedles for transdermal delivery. Journal of controlled release 2014, 185, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, H.-J.; Hampel, H.; Hegerl, U.; Schmitt, W.; Walter, K. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial on the efficacy and tolerability of a physostigmine patch in patients with senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Pharmacopsychiatry 1999, 32, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaskari, T.; Vuorio, M.; Kontturi, K.; Urtti, A.; Manzanares, J.A.; Hirvonen, J. Controlled transdermal iontophoresis by ion-exchange fiber. Journal of controlled release 2000, 67, (2–3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winblad, B.; Cummings, J.; Andreasen, N.; Grossberg, G.; Onofrj, M.; Sadowsky, C.; Zechner, S.; Nagel, J.; Lane, R. A six-month double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of a transdermal patch in Alzheimer's disease––rivastigmine patch versus capsule. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: A journal of the psychiatry of late life and allied sciences 2007, 22, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamsani, N.H.; Hasan, M.S.; Rullah, K.; Haris, M.S. Nicotine-Loaded Polyvinyl Alcohol Electrospun Nanofibers as Transdermal Patches for Smoking Cessation: Formulation and Characterization. Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal 2024, 57, 1637–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, A.; Brandeis, R.; Treves, T.; Meshulam, Y.; Mawassi, F.; Feiler, D.; Wengier, A.; Glikfeld, P.; Grunwald, J.; Dachir, S. Transdermal physostigmine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders 1994, 8, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, K.; Muller, M.; Barkworth, M.; Nieciecki, A.; Stanislaus, F. Pharmacokinetics of physostigmine in man following a single application of a transdermal system. British journal of clinical pharmacology 1995, 39, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utsuki, T.; Uchimura, N.; Irikura, M.; Moriuchi, H.; Holloway, H.W.; Yu, Q.-S.; Spangler, E.L.; Mamczarz, J.; Ingram, D.K.; Irie, T. Preclinical investigation of the topical administration of phenserine: transdermal flux, cholinesterase inhibition, and cognitive efficacy. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2007, 321, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, M.; Ganji, F.; Taghizadeh, S.M.; Daraei, B. Preparation and characterization of rivastigmine transdermal patch based on chitosan microparticles. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research: IJPR 2016, 15, 283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.; Jain, S.; Madan, P.; Lin, S. Influence of electronic and formulation variables on transdermal iontophoresis of tacrine hydrochloride. Pharmaceutical development and technology 2015, 20, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, A.M.; Freitag, F.; Pearlman, S.H. Innovative delivery systems for migraine: the clinical utility of a transdermal patch for the acute treatment of migraine. CNS drugs 2010, 24, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Sui, D. Neuroprotective effects of pramipexole transdermal patch in the MPTP-induced mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 2018, 138, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, H.D. First donepezil transdermal patch approved for Alzheimer disease. JAMA 2022, 327, 1642–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raeder, V.; Boura, I.; Leta, V.; Jenner, P.; Reichmann, H.; Trenkwalder, C.; Klingelhoefer, L.; Chaudhuri, K.R. Rotigotine transdermal patch for motor and non-motor Parkinson’s disease: a review of 12 years’ clinical experience. CNS drugs 2021, 35, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Song, W.; Wang, N.; Ren, Y.; Liu, H. Tip-concentrated microneedle patch delivering everolimus for therapy of multiple sclerosis. Biomaterials advances 2022, 135, 212729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verana, G.; Tijani, A.O.; Puri, A. Nanosuspension-based microneedle skin patch of baclofen for sustained management of multiple sclerosis-related spasticity. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2023, 644, 123352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Derakhshanian, S.; Rath, A.; Bertrand, S.; DeGraw, C.; Barlow, R.; Menard, A.; Kaye, A.M.; Hasoon, J.; Cornett, E.M. Asenapine transdermal patch for the management of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 2020, 50, 60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iwata, N.; Ishigooka, J.; Kim, W.-H.; Yoon, B.-H.; Lin, S.-K.; Sulaiman, A.H.; Cosca, R.; Wang, L.; Suchkov, Y.; Agarkov, A. Efficacy and safety of blonanserin transdermal patch in patients with schizophrenia: a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Schizophrenia research 2020, 215, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaat, K.; Kumar, B.; Das, S.K.; Ul Hasan, R.; Prajapati, S. Novel nanoemulsion as vehicles for transdermal delivery of Clozapine: In vitro and in vivo studies. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2013, 5 (SUPPL 3), 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.; Sen, S.O.; Maji, R.; Nayak, A.K.; Sen, K.K. Transferosomal gel for transdermal delivery of risperidone: Formulation optimization and ex vivo permeation. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2017, 38, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, M.K.; Sireesha, R.; Mounica, N.; Divya, K.; Hemprasad, M. Design and characterization of olanzapine transfersomes for percutaneous administration. Indian Journal of Research in Pharmacy and Biotechnology 2015, 3, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, H.K.; Shah, C.V.; Shah, V.H.; Upadhyay, U.M. Design, development and in vitro evaluation OF controlled release gel for topical delivery of quetiapine using box-behnken design. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2012, 3, 3384. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, R.; Stachnik, J.M.; Echizen, H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of drugs in patients with heart failure: an update (part 1, drugs administered intravenously). Clinical pharmacokinetics 2013, 52, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lainscak, M.; Vitale, C.; Seferovic, P.; Spoletini, I.; Trobec, K.C.; Rosano, G.M. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cardiovascular drugs in chronic heart failure. International journal of cardiology 2016, 224, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangoni, A.A.; Jarmuzewska, E.A. The influence of heart failure on the pharmacokinetics of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular drugs: a critical appraisal of the evidence. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2019, 85, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahad, A.; Aqil, M.; Kohli, K.; Sultana, Y.; Mujeeb, M.; Ali, A. Interactions between novel terpenes and main components of rat and human skin: mechanistic view for transdermal delivery of propranolol hydrochloride. Current drug delivery 2011, 8, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, M.; Liu, J.-C.; Chien, Y.W. Bioavailability of propranolol following oral and transdermal administration in rabbits. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 1990, 79, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwossabi, A.M.; Albegali, A.A.; Al-Ghani, A.M.; Albaser, N.A.; Alnamer, R.A. Advancements in Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems: Innovations, Applications, and Future Directions. Al-Razi University Journal for Medical Sciences 2024, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, N.; Marsh, A. A short history of nitroglycerine and nitric oxide in pharmacology and physiology. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology 2000, 27, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholls, M. Nitric oxide discovery Nobel Prize winners: Robert F. Furchgott, Louis J. Ignarro, and Ferid Murad shared the Noble Prize in 1998 for their discoveries concerning nitric oxide as a signalling molecule in the cardiovascular system. European Heart Journal 2019, 40, 1747–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noonan, P.K.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Ruggirello, D.; Tomlinson, J.; Babcock-Atkinson, E.; Ray, M.; Golub, A.; Cohen, A. Relative bioavailability of a new transdermal nitroglycerin delivery system. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 1986, 75, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka, H.; Kuwajima, I.; Shimada, K.; Mitamura, H.; Saruta, T. Comparison of efficacy and safety between bisoprolol transdermal patch (TY-0201) and bisoprolol fumarate oral formulation in Japanese patients with grade I or II essential hypertension: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2013, 15, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Yagi, S.; Akaike, M.; Sata, M. Transdermal patch of bisoprolol for the treatment of hypertension complicated with aortic dissection. International Journal of Cardiology 2015, 198, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, M.; Fujino, T.; Koike, H.; Kitahara, K.; Kinoshita, T.; Yuzawa, H.; Suzuki, T.; Fukunaga, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Aoki, J. Assessment of a novel transdermal selective β1-blocker, the bisoprolol patch, for treating frequent premature ventricular contractions in patients without structural heart disease. Journal of cardiology 2017, 70, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuchi, S.; Hisatake, S.; Kabuki, T.; Oka, T.; Dobashi, S.; Fujii, T.; Sano, T.; Ikeda, T. Bisoprolol transdermal patch improves orthostatic hypotension in patients with chronic heart failure and hypertension. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension 2020, 42, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasui, T.; Oka, T.; Shioyama, W.; Oboshi, M.; Fujita, M. Bisoprolol transdermal patch treatment for patients with atrial fibrillation after noncardiac surgery: A single-center retrospective study of 61 patients. SAGE open medicine 2020, 8, 2050312120907817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onesti, G.; Bock, K.D.; Heimsoth, V.; Kim, K.E.; Merguet, P. Clonidine: a new antihypertensive agent. The American Journal of Cardiology 1971, 28, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, M.J.; Cortese, S. Current pharmacological treatments for ADHD. New Discoveries in the Behavioral Neuroscience of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, 2022; 19–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gossop, M. Clonidine and the treatment of the opiate withdrawal syndrome. Drug and alcohol dependence 1988, 21, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popli, S.; Stroka, G.; Daugirdas, J.; Norusis, M.; Hano, J.; Gandhi, V. Transdermal clonidine for hypertensive patients. Clinical Therapeutics 1983, 5, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elliott, W.J.; Prisant, L.M. Drug delivery systems for antihypertensive agents. Blood Pressure Monitoring 1997, 2, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, A.; Ebihara, A.; Ohashi, K. i.; Shiga, T.; Kumagai, Y.; Nakashima, H.; Kotegawa, T. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of oral (Catapres) and transdermal (M-5041T) clonidine in healthy subjects. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1994, 34, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, R.; Anwer, M.K.; Shams, M.S.; Ali, A.; Khar, R.K.; Shakeel, F.; Taha, E.I. Proniosomal transdermal therapeutic system of losartan potassium: development and pharmacokinetic evaluation. Journal of drug targeting 2009, 17, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilurzo, F.; Minghetti, P.; Gennari, C.G.; Casiraghi, A.; Selmin, F.; Montanari, L. Formulation study of a patch containing propranolol by design of experiments. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy 2014, 40, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, R.; Khan, Y.; Aman, T. Formulation and Evaluation of Bisoprolol Hemifumarate Emulgel for Transdermal Drug Delivery. DISSOLUTION TECHNOLOGIES 2022, 29, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, H.; Ghorab, M.; El-Nahhas, S.; Kamel, R. Design of a transdermal delivery system for aspirin as an antithrombotic drug. International journal of pharmaceutics 2006, 327, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwhekar, G.; Jain, D.K.; Patidar, V.K. Formulation and evaluation of transdermal drug delivery system of clopidogrel bisulfate. Asian J Pharm Life Sci ISSN 2011, 2231, 4423. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, C.; Gerber, M.; Du Preez, J.L.; Du Plessis, J. Optimised transdermal delivery of pravastatin. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2015, 496, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitorino, C.; Almeida, J.; Gonçalves, L.; Almeida, A.; Sousa, J.; Pais, A. Co-encapsulating nanostructured lipid carriers for transdermal application: from experimental design to the molecular detail. Journal of controlled release 2013, 167, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabareesh, M.; Khan, P.R.; Sudheer, B. Formulation and evaluation of lisinopril dihydrate transdermal proniosomal gels. Journal of applied pharmaceutical science 2011, (Issue), 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, H.L.; Bonham, L.; Hughes, C.M.; Donnelly, R.F. Design of a dissolving microneedle platform for transdermal delivery of a fixed-dose combination of cardiovascular drugs. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2015, 104, 3490–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, M.; Ita, K.B.; Popova, I.E.; Parikh, S.J.; Bair, D.A. Microneedle-assisted delivery of verapamil hydrochloride and amlodipine besylate. European journal Of pharmaceutics and biopharmaceutics 2014, 86, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardesai, M.; Shende, P. Engineering of nanospheres dispersed microneedle system for antihypertensive action. Current Drug Delivery 2020, 17, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Su, C.; Yu, B.; Liu, D.; Chen, H.-J.; Lin, D.-a.; Yang, C.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Q. Biodegradable therapeutic microneedle patch for rapid antihypertensive treatment. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2019, 11, 30575–30584. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Yi, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, H.; Wang, Z. Transdermal hormone delivery: Strategies, application and modality selection. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 104730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Files, J.; Kling, J.M. Transdermal delivery of bioidentical estrogen in menopausal hormone therapy: a clinical review. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery 2020, 17, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Özel, B.; Stanczyk, F.Z.; Felix, J.C.; Mishell Jr, D.R. The effect of transdermal and vaginal estrogen therapy on markers of postmenopausal estrogen status. Menopause 2008, 15, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, O. Engineering for Obstetrics and Gynaecology: Fabrication of the Transdermal Progesterone Patch. UCL (University College London), 2024.

- Suriyaamporn, P.; Aumklad, P.; Rojanarata, T.; Patrojanasophon, P.; Ngawhirunpat, T.; Pamornpathomkul, B.; Opanasopit, P. Fabrication of controlled-release polymeric microneedles containing progesterone-loaded self-microemulsions for transdermal delivery. Pharmaceutical Development and Technology 2024, 29, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banov, D.; Biundo, B.; Ip, K.; Shan, A.; Banov, F.; Song, G.; Carvalho, M. Testosterone Therapy for Late-Onset Hypogonadism: A Clinical, Biological, and Analytical Approach Using Compounded Testosterone 0.5–20% Topical Gels. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varnum, A.A.; van Leeuwen, L.; Velasquez, D.A.; Ledesma, B.; Deebel, N.A.; Codrington, J.; Evans, A.; Diaz, A.; Miller, D.; Ramasamy, R. Testosterone replacement therapy in adolescents and young men. Journal of men's health (Amsterdam) 2024, 20, 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Vashishth, R.; Chuong, M.C.; Duarte, J.C.; Gharat, Y.; Kerr, S.G. Two Sustained Release Membranes Used in Formulating Low Strength Testosterone Reservoir Transdermal Patches. Current Drug Delivery 2024, 21, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fini, A.; Bergamante, V.; Ceschel, G.C.; Ronchi, C.; De Moraes, C.A.F. Control of transdermal permeation of hydrocortisone acetate from hydrophilic and lipophilic formulations. AAPS PharmSciTech 2008, 9, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febrianti, N.Q.; Aziz, A.Y.R.; Tunggeng, M.G.R.; Ramadhany, I.D.; Syafika, N.; Azis, S.B.A.; Djabir, Y.Y.; Asri, R.M.; Permana, A.D. Development of pH-Sensitive Nanoparticle Incorporated into Dissolving Microarray Patch for Selective Delivery of Methotrexate. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Cao, J.; Fang, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhen, Y.; Wu, F.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Applications and recent advances in transdermal drug delivery systems for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2023, 13, 4417–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.-G.; Lei, X.-F.; Ren, B.-D.; Lv, S.-Y.; Zhang, J.-L. Diclofenac transdermal patch versus the sustained release tablet: A randomized clinical trial in rheumatoid arthritic patients. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 2017, 16, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Chao, S.; Lu, W.; Zhang, P. Transdermal delivery of inflammatory factors regulated drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. Drug Delivery 2022, 29, 1934–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Z.; Su, J.; Yang, J.; Han, J.; Zhao, Y. Microneedle-assisted transdermal delivery of etanercept for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobse, J.; Ten Voorde, W.; Tandon, A.; Romeijn, S.G.; Grievink, H.W.; van der Maaden, K.; van Esdonk, M.J.; Moes, D.J.A.; Loeff, F.; Bloem, K. Comprehensive evaluation of microneedle-based intradermal adalimumab delivery vs. subcutaneous administration: results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. British journal of clinical pharmacology 2021, 87, 3162–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzaka, Y.; Uesawa, Y. A Deep Learning-Based Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship System Construct Prediction Model of Agonist and Antagonist with High Performance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defraeye, T.; Bahrami, F.; Rossi, R.M. Inverse mechanistic modeling of transdermal drug delivery for fast identification of optimal model parameters. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 641111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, S.J.M.; Baqersad, J. Mechanical modeling and characterization of human skin: A review. Journal of biomechanics 2022, 130, 110864. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, K.A.; Mohin, S.; Mondal, P.; Goswami, S.; Ghosh, S.; Choudhuri, S. Influence of artificial intelligence in modern pharmaceutical formulation and drug development. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Kong, S.; Lin, R.; Xie, Y.; Zheng, S.; Yin, Z.; Huang, X.; Su, L.; Zhang, X. Machine Learning Assists in the Design and Application of Microneedles. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, A.A.; Dhondale, M.R.; Agrawal, A.K.; Serrano, D.R.; Mishra, B.; Kumar, D. Advancements in microneedle fabrication techniques: artificial intelligence assisted 3D-printing technology. Drug Delivery and Translational Research 2024, 14, 1458–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.A.; Dhondale, M.R.; Singh, M.; Agrawal, A.K.; Muthudoss, P.; Mishra, B.; Kumar, D. Development and comparison of machine learning models for in-vitro drug permeation prediction from microneedle patch. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2024, 199, 114311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagde, A.; Dev, S.; Sriram, L.M.K.; Spencer, S.D.; Kalvala, A.; Nathani, A.; Salau, O.; Mosley-Kellum, K.; Dalvaigari, H.; Rajaraman, S. Biphasic burst and sustained transdermal delivery in vivo using an AI-optimized 3D-printed MN patch. International journal of pharmaceutics 2023, 636, 122647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakashan, D.; Kaushik, A.; Gandhi, S. Smart sensors and wound dressings: Artificial intelligence-supported chronic skin monitoring–A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 154371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-H.; Li, Y.-L.; Wei, M.-Y.; Li, G.-Y. Innovation and challenges of artificial intelligence technology in personalized healthcare. Scientific reports 2024, 14, 18994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundborg, M.; Wennberg, C.; Lidmar, J.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E.; Norlén, L. Skin permeability prediction with MD simulation sampling spatial and alchemical reaction coordinates. Biophysical Journal 2022, 121, 3837–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risueño, I.; Valencia, L.; Jorcano, J.; Velasco, D. Skin-on-a-chip models: General overview and future perspectives. APL bioengineering 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutterby, E.; Thurgood, P.; Baratchi, S.; Khoshmanesh, K.; Pirogova, E. Microfluidic skin-on-a-chip models: Toward biomimetic artificial skin. Small 2020, 16, 2002515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.T.; Budha, R.R.; Kumar, G.R.; Nagamani, B.; Rao, G.K. Exploring Nano-Based Therapeutics by Quantum Computational Modeling. Drug Delivery Systems Using Quantum Computing 2024, 93–139. [Google Scholar]

- Fultinavičiūtė, U. AI benefits in patient identification and clinical trial recruitment has challenges in sight. Clinical Trials Arena https://www. clinicaltrialsarena. com/features/ai-clinical-trial-recruitment, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alowais, S.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Alsuhebany, N.; Alqahtani, T.; Alshaya, A.I.; Almohareb, S.N.; Aldairem, A.; Alrashed, M.; Bin Saleh, K.; Badreldin, H.A. Revolutionizing healthcare: the role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC medical education 2023, 23, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diseases | Virus | TDDS | TDDS role | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herpes simplex | Herpes simplex viruses (HSV) | Binary Ethosome | Drug delivery of acyclovir sodium | [42] |

| Water-in-oil microemulsion containing acyclovir | Enhanced acyclovir delivery using w/o type microemulsion | [47] | ||

| Acyclovir gel plaster containing sponge spicules (AGP-SS) | To achieve synergistic improvements in skin absorption and deposition of acyclovir | [51] | ||

| Hydrogel Nanoemulsion containing penciclovir | Develop Nanoemulsion containing penciclovir for transdermal drug delivery | [46] | ||

| Influenza | Influenza virus | Influenza vaccine loaded egg microneedles. | Influenza vaccine | [48] |

| The microneedle array patch (MAP) is loaded with ZAN. | Drug delivery of zanamivir | |||

| Warts | HPV | Solid microneedles | Facilitated penetration of topical 5-FU |

[50] |

| COVID-19 | SARS-CoV-2 | Fluorocarbon-modified chitosan (FCS)based transdermal delivery platforms of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines |

COVID-19 Vaccines | [50] |

| Dissolving microneedles containing embedded SARS-CoV-2-S1 subunits |

COVID-19 vaccines | [45] |

| Drug | Indication | TDDS | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine | Dementia, Alzheimer's disease | Transdermal patch-matrix | [62] |

| Physostigmine | Alzheimer disease | Transdermal patch-control release | [63,64] |

| Phenserine | Cognition impairment | Transdermal patch-reservoir type | [65] |

| Rivastigmine | Behavioral disorders | Transdermal patch-control release | [66] |

| Tacrine | Alzheimer disease | TDDS by iontophoresis | [67] |

| Sumatriptan | Migraine | Transdermal patch-control release | [68] |

| Pramipexole | Parkinson’s disease | Transdermal patch | [69] |

| Donepezil | Alzheimer disease | Transdermal patch | [70] |

| Rotigotine | Parkinson’s disease | Transdermal patch | [71] |

| Everolimus | Multiple sclerosis | Microneedle-based transdermal patch | [72] |

| Baclofen | Multiple sclerosis | Nanosuspension-based microneedle skin patch | [73] |

| Asenapine | Schizophrenia | Transdermal patch | [74] |

| Blonaserin | Schizophrenia | Transdermal patch | [75] |

| Clozapine | Schizophrenia | Nanoemulsion-based transdermal drug delivery system | [76] |

| Risperidone | Antipsychotic | Transferosomal gel-transdermal | [77] |

| Olanzapine | Antipsychotic | Transferosomal TDDS | [78] |

| Quetiapine | Antipsychotic | Liposomal TDDS | [79] |

| Drug | Indication | TDDS | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitroglycerin | Angina pectoris | Microneedle Transdermal patch | [88] |

| Propranolol | Antihypertensive | Gel-based transdermal patch | [101] |

| Bisoprolol | Atrial fibrillation | Gel-based transdermal patch | [102] |

| Clonidine | Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | Polymeric transdermal patch | [99] |

| Losartan | Antihypertensive | Proniosome TDDS | [100] |

| Aspirin | Antithrombotic | Hydrocarbon gel-based TDDS | [103] |

| Clopidogrel | Antithrombotic | Polymeric transdermal patch | [104] |

| Pravastatin | Antithrombotic | emulgel based transdermal patch | [105] |

| Simvastatin | Hypercholesterolemia | Nanostructured lipid carrier-based TDDS | [106] |

| Lisinopril | Congestive heart failure | Lipid-based transdermal gels | [107] |

| Atorvastatin | Hypercholesterolemia | Microneedle based TDDS | [108] |

| Verapamil hydrochloride and amlodipine besylate | Chronic hypertension | Microneedle-based transdermal patch | [109] |

| Diltiazem and nifedipine | Chronic hypertension | Nanosphere-based microneedle TDDS | [110] |

| Sodium nitroprusside | Hypertensive emergency | Dissolvable microneedle patch | [111] |

| Drug | Indication | Formulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estrogen, Progesterone | Hormonal imbalance, Menopause | Transdermal patches, gels | [114,115,116] |

| Testosterone | Hormonal imbalance | Transdermal gels, patches | [117,118,119] |

| Hydrocortisone | Inflammation, Hormonal imbalance | Transdermal creams, gels | [120,121] |

| Methotrexate | Autoimmune Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) | Transdermal patches | [121] |

| Hydrocortisone | Autoimmune (RA), inflammation | Transdermal patches, creams | [122] |

| Diclofenac (NSAID) | Autoimmune (RA), pain relief | Transdermal patches | [123] |

| Etanercept (TNF inhibitor) | Autoimmune (RA) | Transdermal patches, microneedles | [124,125] |

| Adalimumab (TNF inhibitor) | Autoimmune (RA) | Transdermal patches, microneedle | [126] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).