1. Introduction

Stroke is defined by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) as a neurological deficit secondary to acute focal injury of the central nervous system (CNS) caused by conditions such as cerebral infarction, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) [

1]. Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) accounts for 65% of all stroke cases worldwide, with this proportion reaching up to 87% in some studies [

2,

3]. AIS, a significant cause of disability and mortality worldwide, affects approximately 57.93 million people annually [

4]. However, AIS is a treatable condition when addressed in its early stages [

5]. While various radiological imaging techniques can be used to detect AIS, diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI) is the most accurate method [

6].

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a sophisticated branch of technology that mimics human intelligence and has brought about revolutionary changes across various fields. This technology can generate original content in multiple forms, including text, images, music, and video. Applicable in nearly every sector—from healthcare to finance, education to transportation—AI stands out for its ability to solve complex problems, perform data analysis, and make predictions. Two of the most prominent examples of AI are Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer (ChatGPT) (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) and Claude (Anthropic, San Francisco, CA, USA), which have made groundbreaking advancements in the field of natural language processing. ChatGPT, developed by OpenAI and introduced on November 30, 2022, is one of the large language models (LLMs) capable of generating human-like text, responding to complex questions, and leveraging an extensive knowledge base [

7]. On the other hand, Claude, launched by Anthropic in March 2023, is an LLM designed with a particular emphasis on ethics and safety, incorporating a more controlled and transparent approach [

8]. Both models excel in interacting naturally with users, providing information on a wide range of topics, and generating creative content.

The integration of AI technology into radiological imaging systems holds significant potential for accelerating disease diagnosis processes, enhancing workflow efficiency, and minimizing errors caused by human factors [

9]. In the literature, there are several studies exploring the detection of pathologies from radiological images using ChatGPT [

10,

11,

12]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted on the detection of pathologies from radiological images using Claude.

The aim of this study is to investigate the detectability of AIS from DW-MRI images using the two most popular AI models, ChatGPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet, and to compare their diagnostic performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Cases

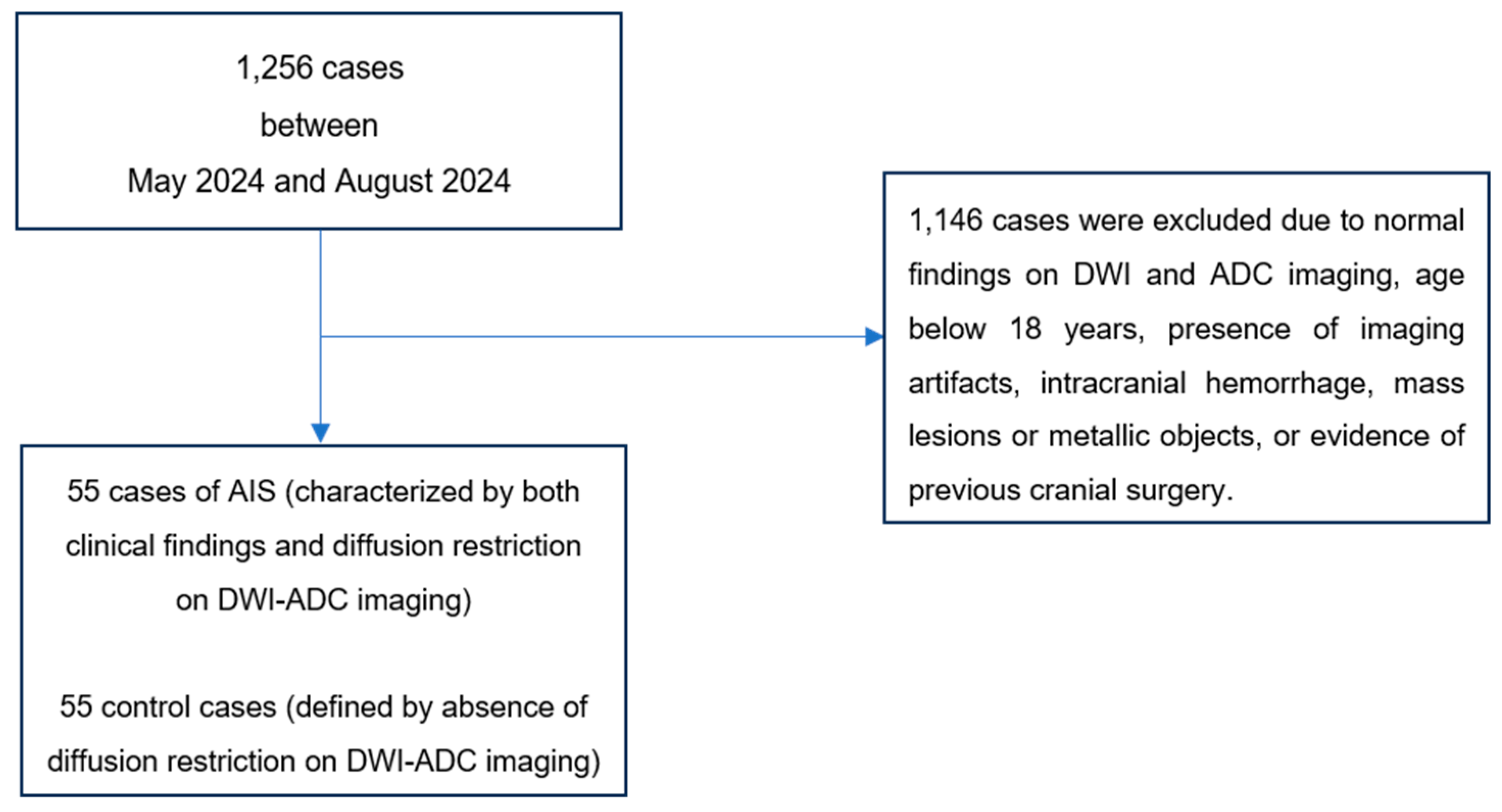

The diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps of a total of 1,256 patients recorded in our hospital's Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS) between May 2024 and September 2024 were reviewed.

The AIS group consisted of 55 cases identified with characteristic clinical symptoms (hemiparesis, aphasia, facial asymmetry, diplopia, and vision loss) recorded in the hospital information system and diffusion restriction detected on their DWI and ADC images (

Figure 1). The control group was composed of 55 healthy cases who underwent DWI and ADC imaging for various indications but showed no diffusion restriction (

Figure 1).

The cases were determined by consensus of two radiology specialists with 8 and 12 years of experience, respectively.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were defined as follows: for the AIS group, the presence of clinical symptoms and diffusion restriction on DWI-ADC images; for the control group, the absence of clinical findings and diffusion restriction.

The exclusion criteria for both groups were standardized as follows: the presence of artifacts limiting image evaluation, age under 18 years, a history of intracranial mass or recent cranial surgery, intracranial hemorrhage, or the presence of metallic objects.

2.3. Prompt Prepared for AI Models

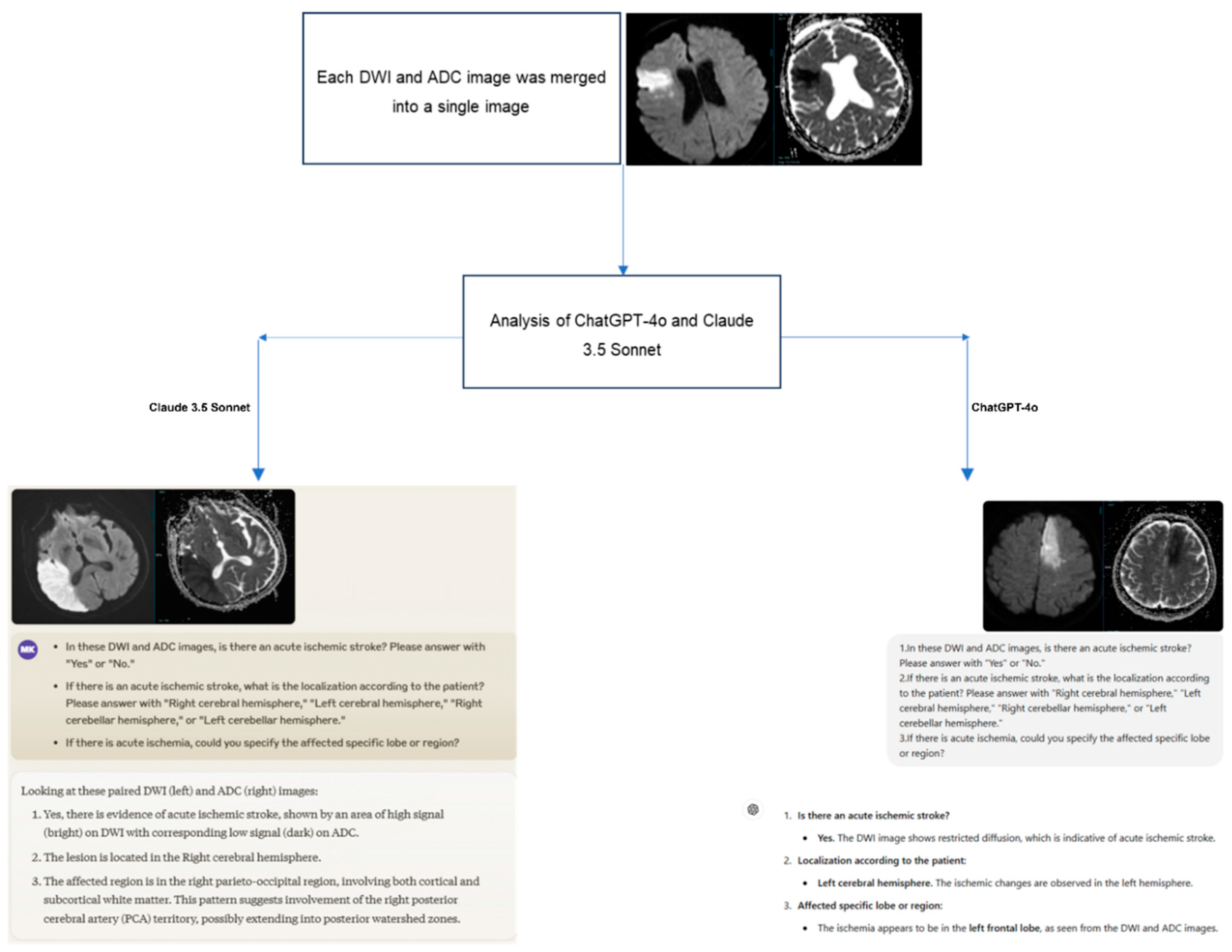

A structured three-question prompt was developed for the images presented to the ChatGPT-4 and Claude 3.5 Sonnet models as follows:

In these DWI and ADC images, is there an acute ischemic stroke? Please answer with "Yes" or "No."

If there is an acute ischemic stroke, what is the localization according to the patient? Please answer with "Right cerebral hemisphere," "Left cerebral hemisphere," "Right cerebellar hemisphere," or "Left cerebellar hemisphere."

If there is acute ischemia, could you specify the affected specific lobe or region?

2.4. Brain DWI and ADC İmages

The brain DWI and ADC images for all cases were obtained using a 1.5T MRI scanner (GE Signa Explorer; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin).

2.5. Preparation and Presentation of İmages to the Models

For AIS cases, the DWI slice where the lesion was optimally visualized and its corresponding ADC image were selected. In the control group, images corresponding to the slice levels of the AIS group were evaluated to ensure comparability. Considering the image analysis capabilities of current AI models (JPEG, PNG, and static GIF formats), the DWI and ADC images in DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) format were anonymized and converted to JPEG format using AW Volumeshare 7 software (AW 4.7 version, GE Healthcare, USA).

To enable comprehensive evaluation by the models, the DWI and ADC images were combined into a single image. Before uploading, orientation verification was performed by radiologists, and non-brain structures were removed from the images. To minimize bias, the cases were presented to the models in a randomized order, accompanied by the three-question prompt mentioned earlier. The responses provided by the models were recorded (

Figure 2).

Additionally, to assess intra-model reliability, all cases were reanalyzed with the same models two weeks later.

2.6. Evaluation of Outputs

To ensure standardization during the evaluation process, preliminary assessments were conducted on sample cases not included in the study to establish consensus on evaluation criteria among the radiologists. The response categorization criteria were defined as follows: a "correct" response required full agreement between the model’s answers and the radiologists’ reports, while a "wrong" response was defined as a mismatch in key findings or the presence of diagnostically critical errors.

Throughout the evaluation process, radiologists conducted their work using medical monitors on diagnostic imaging workstations.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 23 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of data distribution was assessed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. An Independent Samples T-test was used to compare age between groups, while a Chi-square test was applied for gender distribution comparisons. Quantitative data with normal distribution were presented as mean and standard deviation (Mean ± SD), and categorical data were reported as frequency (n) and percentage (%).

The imaging analysis performance of the models was evaluated in comparison to radiologist assessments (gold standard). The performance of ChatGPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet was assessed by calculating sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and diagnostic accuracy rates. The agreement between the models and radiologists, as well as inter- and intra-model reliability, was assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient.

The interpretation of the kappa coefficient was as follows: ≤0.20 as “slight agreement,” 0.21–0.40 as “fair agreement,” 0.41–0.60 as “moderate agreement,” 0.61–0.80 as “substantial agreement,” and 0.81–1.00 as “almost perfect agreement.” Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

2.8. Ethical Approval

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Kastamonu University on December 10, 2024, under approval number 2024-KAEK-134. The study adhered to the Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM) guidelines [

13]. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, written informed consent was not obtained from the patients.

3. Results

3.1. Results Obtained from Demographic Data

A total of 110 cases were included in the study, with 55 cases in the AIS group and 55 in the healthy control group. Both groups consisted of 25 females (45.5%) and 30 males (54.5%). The mean age of the AIS group was 73.11 ± 11.43 years, while the mean age of the healthy control group was 72.75 ± 10.75 years. No significant differences were found between the AIS and healthy control groups in terms of age or gender (p>0.05) (

Table 1).

3.2. Diagnostic Performance of the Models

In the diagnostic performance analysis of ChatGPT-4o for AIS detection, all cases in the AIS group (100%) yielded true positive results. However, in the control group, only two cases (3.6%) produced true negative results, while 53 cases (96.4%) resulted in false positive outcomes (

Table 2).

For Claude 3.5 Sonnet, the diagnostic performance for AIS detection showed 52 cases (94.5%) with true positive results and 3 cases (5.5%) with false negative results in the AIS group. In the control group, 41 cases (74.5%) produced true negative results, while 14 cases (25.5%) resulted in false positive outcomes (

Table 2).

Both models demonstrated high sensitivity for AIS detection (ChatGPT-4o: 100%, Claude 3.5 Sonnet: 94.5%), but specificity values differed significantly (ChatGPT-4o: 3.6%, Claude 3.5 Sonnet: 74.5%). The diagnostic accuracy of Claude 3.5 Sonnet (84.5%) was higher compared to ChatGPT-4o (51.8%). The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) for both models are presented in

Table 2.

3.3. Agreement Analysis Between Models and Radiologists

ChatGPT-4o demonstrated slight agreement with the radiologists' gold-standard assessment (κ = 0.036). In contrast, Claude 3.5 Sonnet showed substantial agreement with the radiologists (κ = 0.69) (

Table 3).

3.4. Performance of the Models in Detecting Hemispheric Localization of AIS

ChatGPT-4o correctly identified the hemisphere of AIS localization in 18 out of 55 cases (32.7%) in the AIS group (16 in the right cerebral hemisphere and 2 in the left cerebral hemisphere). However, in the healthy control group, it incorrectly made localization predictions in 53 out of 55 cases (96.4%) despite the absence of AIS (

Table 4).

In terms of hemispheric localization, ChatGPT-4o demonstrated slight agreement with radiologists (κ = 0.077).

Claude 3.5 Sonnet correctly identified the hemisphere of AIS localization in 37 out of 55 cases (67.3%) in the AIS group (17 in the right cerebral hemisphere and 20 in the left cerebral hemisphere). However, in the healthy control group, it incorrectly made localization predictions in 14 out of 55 cases (25.5%) despite the absence of AIS (

Table 5).

In detecting AIS localization by hemisphere, Claude 3.5 Sonnet demonstrated moderate agreement with the gold-standard radiologists (κ = 0.572). Additionally, Claude 3.5 Sonnet was statistically significantly more successful than ChatGPT-4o in accurately identifying AIS localization by hemisphere (p = 0.0006).

3.5. Performance of the Models in Detecting Specific AIS Localization

ChatGPT-4o correctly identified the specific localization of AIS in only 4 cases (7.3%) within the AIS group, while making incorrect determinations in the remaining 51 cases (92.7%). In contrast, Claude 3.5 Sonnet accurately identified the specific localization in 17 cases (30.9%) within the AIS group, but made incorrect determinations in 38 cases (69%) (

Table 6).

In detecting the specific lobe or region of AIS localization, ChatGPT-4o demonstrated slight agreement with radiologists (κ = 0.026), while Claude 3.5 Sonnet showed fair agreement (κ = 0.365). Claude 3.5 Sonnet was found to be statistically significantly more successful than ChatGPT-4o in accurately identifying the specific lobe or region of AIS localization (p = 0.0016).

3.6. Second Round of Model Evaluations and İntra-Model Agreement Analysis

After a two-week interval, the DWI-ADC images were reevaluated by the models. In the second evaluation, ChatGPT-4o again showed 100% true positive results for all AIS cases. In the healthy control group, 48 cases (87.3%) resulted in false positives, while 7 cases (12.7%) produced true negative results (

Table 7). Claude 3.5 Sonnet correctly identified 46 cases (83.6%) as true positive and 9 cases (16.4%) as false negative in the AIS group. In the healthy control group, 46 cases (83.6%) were identified as true negative, and 9 cases (16.4%) were false positive (

Table 7).

In the second evaluation, ChatGPT-4o showed an increase in specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and diagnostic accuracy (

Table 7). On the other hand, Claude 3.5 Sonnet showed a decrease in sensitivity, negative predictive value (NPV), and diagnostic accuracy, while specificity and PPV values increased (

Table 7).

Moderate agreement was found between the two evaluations for both ChatGPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet in detecting the presence of AIS (κ = 0.428 for ChatGPT-4o, κ = 0.582 for Claude 3.5 Sonnet).

In the assessment of hemispheric localization of AIS, fair agreement was found between the first and second round results of ChatGPT-4o (κ = 0.259), while moderate agreement was observed between the first and second round results of Claude 3.5 Sonnet (κ = 0.524).

In the evaluation of AIS localization in specific lobes or regions, moderate agreement was found between the first and second round results of ChatGPT-4o (κ = 0.443), while fair agreement was found between the results of Claude 3.5 Sonnet (κ = 0.384).

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the ability of the ChatGPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet AI models to detect the presence and localization of AIS from DWI and ADC images. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in the literature that uses both ChatGPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet for AIS detection. Our study demonstrates that advanced LLMs with advanced visual capabilities, such as ChatGPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet, can detect AIS from DWI and ADC images with a high degree of accuracy.

In this study, both models demonstrated significant success, but Claude 3.5 Sonnet achieved a higher diagnostic accuracy rate (84.5%) compared to ChatGPT-4o (51.8%). In the study by Kuzan et al., ChatGPT showed a sensitivity of 79.57% and specificity of 84.87% in stroke detection, whereas in our study, ChatGPT-4o exhibited a higher sensitivity (100%) but a significantly lower specificity (3.6%) [

14]. Kuzan et al. excluded lacunar infarcts smaller than 1 centimeter in their study. However, in our study, AIS cases of all sizes were included, which could affect the sensitivity and specificity values of the models. There is no existing literature data to compare the performance of Claude 3.5 Sonnet, and it is anticipated that our study will serve as a reference for future research.

Both models lagged behind in terms of AIS localization (hemispheric and specific region), compared to their success in detecting the presence of AIS. In hemispheric localization, Claude 3.5 Sonnet (67.3%) performed statistically significantly better than ChatGPT-4o (32.3%) (p = 0.0006). ChatGPT-4o's low hemispheric localization success (32.3%) is similar to the findings in Kuzan et al.'s study (26.2%) [

14]. Both models showed the lowest success in detecting the affected specific lobe or region. However, Claude 3.5 Sonnet demonstrated statistically significantly higher performance compared to ChatGPT-4o (31% vs. 7.3%, p = 0.0016). In Kuzan et al.'s study, the lowest success rate (20.4%) was also observed in detecting the specific lobe or region [

14]. These results indicate that Claude 3.5 Sonnet outperformed ChatGPT-4o in localizing AIS. Additionally, our study reveals that both models show performance limitations in situations requiring complex assessments.

In terms of detecting the presence of AIS, ChatGPT-4o showed slight agreement with the radiologists' gold-standard assessments (κ = 0.036), while Claude 3.5 Sonnet demonstrated substantial agreement (κ = 0.691). Both ChatGPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet showed moderate agreement in their internal evaluations regarding the presence of AIS (κ = 0.428 and κ = 0.582, respectively). When assessing hemispheric localization of AIS, ChatGPT-4o demonstrated fair internal agreement (κ = 0.259), while Claude 3.5 Sonnet showed moderate internal agreement (κ = 0.524). In evaluating the specific lobe or region localization of AIS, ChatGPT-4o exhibited moderate internal agreement (κ = 0.443), whereas Claude 3.5 Sonnet showed fair internal agreement (κ = 0.384). These findings indicate that the AI models demonstrate some level of consistency in AIS detection, with Claude 3.5 Sonnet showing relatively higher internal consistency. However, these results also suggest that both models need further development to optimize their diagnostic consistency.

LLMs like ChatGPT and Claude have stochastic output generation mechanisms [

14]. This characteristic leads to different results being produced in repeated processes for the same input. This stochastic nature has the potential to enhance user experience by increasing diversity and dynamism in human-machine interactions. However, this becomes a significant limiting factor when applied in areas that require precision, such as medical image analysis. Since consistency and repeatability are critical in medical diagnosis and interpretation processes, this structural feature of the models limits their reliability and validity in clinical applications. Both models produced false positive and false negative results, and the stochastic nature of the models may be one of the reasons for these outcomes. Additionally, the lack of specific training for medical image analysis and the limited image processing capabilities of these models could also contribute to the incorrect results.

LLMs, especially ChatGPT, in radiology is steadily increasing. In the study by Akinci D'Antonoli and colleagues, both the benefits and challenges of using language models in radiology are highlighted [

15]. Recent literature shows that these models are capable of tasks such as data mining from free-text radiology reports [

16], generating structured reports [

17], answering disease-related questions [

18], and responding to radiology board-style exam questions [

19]. Furthermore, recent studies suggest that evaluating radiological images with these models may be feasible [

11,

12,

20]. LLMs could assist radiologists in image assessment and clinicians in diagnosing at centers without radiologists, but it should be noted that these models are still in the early stages and can make errors.

Our study has some limitations. The first is that not all DWI and ADC slices from the patients were uploaded to the models. If the entire set of images had been uploaded, the diagnostic accuracy of both models might have increased. One of the methodological limitations of the study is the necessity of converting the original DICOM format radiological images to JPEG or PNG format for analysis by both models. This format conversion process could potentially lead to the loss of image details and metadata that are diagnostically critical, which may negatively affect the analysis capacity of the AI models and the reliability of the results [

12]. Another limitation of our study is the potential selection bias that may have occurred during the image selection process for DWI and ADC. The specific inclusion and exclusion criteria applied by the radiologists could have impacted the representativeness of the sample.

5. Conclusions

In light of the findings of our study, advanced language models such as ChatGPT and Claude AI can be considered as potential supportive tools in detecting the presence of AIS from DWI and ADC images. The low accuracy rates in localization detection highlight the need for further development of these models in this regard. The performance demonstrated by these models complements traditional radiological evaluation processes and represents an innovative approach that could be integrated into clinical decision-making mechanisms. However, before these technologies are routinely used in clinical practice, they need to be validated and optimized through larger-scale, multicenter studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K; methodology, M.K and I.T; validation, M.K and I.T; formal analysis, M.K; investigation, M.K; resources, M.K and I.T; data curation, M.K and I.T; writing—original draft preparation, M.K; writing—review and editing, M.K and I.T; visualization, M.K; supervision, I.T; project administration, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Kastamonu University, Turkey (Decision No: 2024-KAEK-134, Date: 10.12.2024).

Informed Consent Statement

In accordance with the retrospective nature of this investigation, the procurement of informed consent from study participants was deemed unnecessary. This exemption is consistent with institutional protocols governing retrospective analyses, where data collection and evaluation are performed on previously acquired medical records and imaging studies. Furthermore, all patient data were anonymized and handled in compliance with established medical research ethical guidelines and data protection regulations.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sacco, R. L.; Kasner, S. E.; Broderick, J. P.; Caplan, L. R.; Connors, J. J.; Culebras, A. … & Vinters, H. V. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013, 44, 2064–2089. [Google Scholar]

- Nentwich, L. M. Diagnosis of acute ischemic stoke. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2016, 34, 837–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, V.; Guada, L.; Yavagal, D. R. Global epidemiology of stroke and access to acute ischemic stroke interventions. Neurology 2021, 97 (20_Supplement_2), S6–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faletti, D. O.; Fakayode, O. O.; Adedara, V. O.; Kuteyi, A. O.; Adedara, C. A.; Ogunmoyin, T. E. … & Giwa, B. O. Comparative efficacy and safety of thrombectomy versus thrombolysis for large vessel occlusion in acute ischemic stroke: a systemic review. Cureus 2024, 16, e72323. [Google Scholar]

- Kurz, K. D.; Ringstad, G.; Odland, A.; Advani, R.; Farbu, E.; Kurz, M. W. Radiological imaging in acute ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol 2016, 23, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, M. M.; Schaefer, P. W. Ischemic stroke. Radiologic Clinics 2011, 49, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ChatGPT. Available online: https://chatgpt.com/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Claude. Available online: https://claude.ai/new (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Hosny, A.; Parmar, C.; Quackenbush, J.; Schwartz, L. H.; Aerts, H. J. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 18, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haver, H. L.; Bahl, M.; Doo, F. X.; Kamel, P. I.; Parekh, V. S.; Jeudy, J.; Yi, P. H. Evaluation of multimodal ChatGPT (GPT-4V) in describing mammography image features. Can Assoc Radiol J 2024, 75, 947–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mert, S.; Stoerzer, P.; Brauer, J.; Fuchs, B.; Haas-Lützenberger, E. M.; Demmer, W. … & Nuernberger, T. Diagnostic power of ChatGPT 4 in distal radius fracture detection through wrist radiographs. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2024, 144, 2461–2467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dehdab, R.; Brendlin, A.; Werner, S.; Almansour, H.; Gassenmaier, S.; Brendel, J. M. … & Afat, S. Evaluating ChatGPT-4V in chest CT diagnostics: a critical image interpretation assessment. Jpn J Radiol 2024, 42, 1168–1177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mongan, J.; Moy, L.; Kahn Jr, C. E. Checklist for artificial intelligence in medical imaging (CLAIM): a guide for authors and reviewers. Radiol Artif Intell 2020, 2, e200029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzan, B. N.; Meşe, İ.; Yaşar, S.; Kuzan, T. Y. A retrospective evaluation of the potential of ChatGPT in the accurate diagnosis of acute stroke. Diagn Interv Radiol 2024. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinci D'Antonoli, T.; Stanzione, A.; Bluethgen, C.; Vernuccio, F.; Ugga, L.; Klontzas, M. E. … & Koçak, B. Large language models in radiology: fundamentals, applications, ethical considerations, risks, and future directions. Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology 2024, 30, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, M. A.; Bischoff, A.; Fink, C. A.; Moll, M.; Kroschke, J.; Dulz, L. … & Weber, T. F. Potential of ChatGPT and GPT-4 for data mining of free-text CT reports on lung cancer. Radiology 2023, 308, e231362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adams, L. C.; Truhn, D.; Busch, F.; Kader, A.; Niehues, S. M.; Makowski, M. R.; Bressem, K. K. Leveraging GPT-4 for post hoc transformation of free-text radiology reports into structured reporting: a multilingual feasibility study. Radiology 2023, 307, e230725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahsepar, A. A.; Tavakoli, N.; Kim, G. H. J.; Hassani, C.; Abtin, F.; Bedayat, A. How AI responds to common lung cancer questions: ChatGPT versus Google Bard. Radiology 2023, 307, e230922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhayana, R.; Krishna, S.; Bleakney, R. R. Performance of ChatGPT on a radiology board-style examination: insights into current strengths and limitations. Radiology 2023, 307, e230582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haver, H. L.; Yi, P. H.; Jeudy, J.; Bahl, M. Use of ChatGPT to Assign BI-RADS Assessment Categories to Breast Imaging Reports. Am J Roentgenol 2024, 3, e2431093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).