1. Introduction

The study of atomically thin two-dimensional (2D) systems has become one of the most important research topics of condensed matter physics due to their fascinating and tunable properties, accompanied by numerous possible applications [

1,

2]. The pursuit of tailoring electronic, vibronic and optical properties with the number of atomic layers in the 2D crystals is a central goal in this area [

3,

4]. After the discovery of graphene [

5], many new 2D materials have been predicted theoretically, synthesized, and investigated experimentally. Their electronic properties may vary with the number of atomic layers. For instance, monolayer and few-layer transition metal dichalcogenides usually exhibit a thickness-induced indirect to direct band gap [

6]. Among the interesting 2D systems are layered group-III monochalcogenides, with important vibrational, electronic and optical properties [

2,

4,

7,

8].

Monolayers of Al monochalcogenides have been predicted to show an excellent thermoelectric performance [

8]. Despite their character as indirect band gap semiconductors [

9], they may be of interest for optoelectronic and photovoltaic applications [

10]. However, Al monochalcogenides have been less investigated as compared with Ga- and In-based compounds and layered systems.

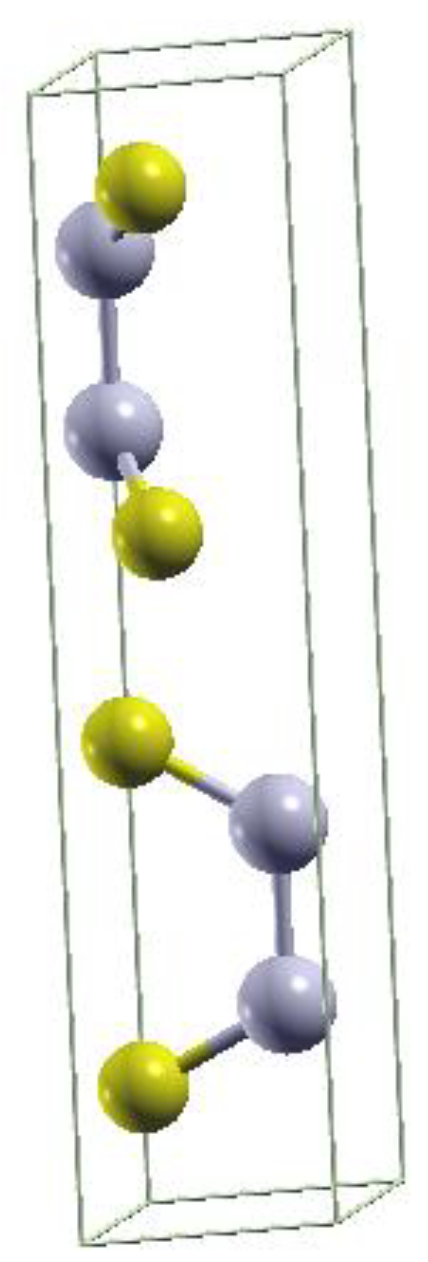

In this work, as an example for Al monochalcogenides, AlSe in the bulk and layered form is studied in a systematic manner. An “AlSe monolayer” is represented by a Se-Al-Al-Se tetralayer (TL) similar to the InSe [

4] or GaSe [

7] one. It consists of four covalently bonded atomic planes. The corresponding few-tetralayer systems, 2TL and 3TL, as well as the bulk AlSe (with 2 TLs in one unit cell) are vertically stacked in an AC manner, leading to the ε-polytype in the bulk case (see

Figure 1). The TLs are held together by weak interactions including the van der Waals (vdW) one [

11]. We optimize the atomic geometrics of the layered systems applying several exchange-correlation (XC) functionals in the density functional theory (DFT). We derive atomic geometries with and without vdW interaction. Phonon branches are investigated using the local density approximation (LDA). They are used to predict Raman and infrared (IR) spectra for several thicknesses, 1TL, 2TL, 3TL and bulk. Besides DFT band structures, the energy gaps are also investigated by taking quasiparticle (QP) effects into account in an approximate manner. The results are compared with available theoretical and experimental data.

2. Theoretical and Computational Methods

The DFT [

12] is applied to optimize the atomic configurations of bulk AlSe and several layered systems using different XC functionals, the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) [

13] as proposed by Perdew, Burke and Ernzerhof of (PBE) [

14] and the local density approximation (LDA) [

14]. They are implemented in the ab initio simulation package Quantum Espresso (QE) [

15]. The use of pseudopotentials is combined with a plane-wave expansion of the single-particle electronic wave functions. The vdW interaction between the TLs within the multilayer stacks and the bulk crystal is taken into account by adding a semiempirical dispersion (D) term to the conventional total energy in DFT [

12] through a pair-wise force field following Grimme’s DFT-D2 approach [

16].

Several approximations are used to compute the electronic band structure of the TL stacks and of the AlSe bulk. Beside the LDA, we applied the PBE functional but together with atomic positions from the PBE-vdW calculations. Moreover, to overcome the underestimation of fundamental gaps and interband distances between conduction and valence bands, we added approximate QP corrections [

17] by applying the screened-hybrid functional according to the Heyd, Scuseria and Ernzerhof (HSE06) [

18,

19].

The 2D stacks of AlSe are treated within the repeated slab approximation [

17] using periodic boundary conditions and a vacuum region of about 18 Å between 1TL, 2TL, and 3TL in normal direction of the stacks, which is sufficient to make the interaction among the periodic images negligible. The AC stacking of bulk ε-AlSe is also applied for 2TL and 3TL few-layer systems. The Brillouin zone (BZ) integration in performed using Monkhorst Pack k-point sets [

20] of 18×18×1 for the stacks and 6×6×6 for the bulk system. The atomic geometries are relaxed until Hellmann-Feynman forces are below 10

-8 a.u. The energy cutoff of the plane-wave expansion is taken at 150 Ry, while the total energy convergence is fixed at 10

-16 Ry.

The phonon branches and the Raman and IR spectra ruled by zone-center optical phonons are computed within the density functional perturbation theory [

21] and the LDA. A mesh of 7×7×7 (7×7×1) q-points is applied to compute frequencies and spectra for AlSe bulk (2D stacks 1TL, 2TL, and 3TL). The long-range interaction mediated by a macroscopic electric field in 3D (only perpendicular to the stacking direction) is also taken into account [

22,

23].

3. Atomic and Electronic Structures

3.1. Geometries and Energies

An AlSe single TL (1TL) possesses a honeycomb structure, i.e., a 2D hexagonal Bravais lattice with a lattice constant

a=2.542 (2.582, 2.556) Aº in LDA (PBE, PBE+vdW, see

Table I). A unit cell consists of two inner Al and two outer Se atoms (see

Figure 1). The mainly strongly covalently bonded structure in one unit cell is determined by the Al-Al (d

Al-Al) and Al-Se (d

Al-Se) bond lengths and the vertical Se-Se distance (d

Se-Se), which also rules the thickness of the TL. The three values obtained within LDA (PBE, PBE+vdW) show the expected trend [

17], an overbinding in LDA and an underbinding in PBE and including generalized gradient corrections. Adding the attractive vdW interaction to the PBE treatment, intermediate distances appear in Table I. Our PBE results are in excellent agreement with those of similar calculations [

2,

9,

10,

24]. Other first-principles calculations [

8] gave slightly deviating lengths.

The single AlSe TL has a hexagonal D

13h (D

3h) space (point) group symmetry [

25]. Bulk crystalline AlSe phases may exist in different polytypes β, γ and ε. Our test total energy calculations suggest the ε-polytype as the energetically most stable one. It shows an AC stacking of two TLs in the unit cell as illustrated in

Figure 1. This result agrees with experimental findings for GaSe, where flakes deposited on graphite [

26,

27] and bulk samples, grown by the Bridgman method [

28], occur in the ε form. On the other hand, growth of bulk InSe seems to favor the β polytype [

29,

30]. In the case of

ɛ stacking only one pair of Al or Se atoms is aligned with the Se or Al atoms in another TL. In the 2TL arrangement the actual stacking without inversion center slightly lowers the symmetry to the trigonal C

13v (C

3v) space (point) group [

32]. The 3TL few-layer system exhibits the same symmetry as the monolayer case. In the bulk AlSe with 2 TLs in the unit cell we investigate the same symmetry as for the bilayer system.

The trends with increasing numbers of atomic layers 1TL, 2TL, 3TL to bulk in Table I are not unique. While the Al-Al bond length dAl-Al increases, we notice that other lengths such as a, dSe-Se, and dAl-Se, present slightly fluctuating values, somewhat also depending on the applied XC functional LDA or PBE+vdW. This also holds for the distance DSe-Se between TLs. The characteristic average value in LDA DSe-Se=3.195 is not too different from the PBE+vdW average result DSe-Se=3.272 Å. Despite the vdW bonding between the TLs, the PBE+vdW distances are only slightly above LDA lengths. Therefore, the LDA XĊ functional is a reasonable starting point to compute the phonon spectra within the Density Functional Perturbation Theory (DFTP).

In order to characterize the inter-tetralayer interaction in the multilayer stacks 2TL, 3TL and bulk, we determine the interlayer bonding energy E

b by taking the total energy of a layered system per unit cell and per TL and subtract the value for the monolayer 1TL system. The lowering of the total energy ΔE

tot per TL is displayed in Table I. Independent of the XC functional, LDA or PBE+vdW, we observe a gain in the total energy by ΔE

tot= -0.8 (-0.8), -1.0 (-0.8) and -1.3 (-0.8) eV/TL along 2TL, 3TL, and bulk in LDA (PBE+vdW). These quantities can be projected onto the fraction of interfaces between two TL, 1/2 (2TL), 2/3 (3TL) and 1 (bulk), which occur in the considered layered systems. Consequently, the binding energy per interface E

b = 1.5 (1.5), 1.5 (1.2) and 1.3 (0.8) eV/interface in 2TL, 3TL and bulk, respectively, appears. All these energy values show that the interaction between two TLs is stronger in LDA compared to the results obtained within PBE+vdW. Interestingly, for AlSe the energies ΔE

tot and E

b exceed the corresponding values found in the other layered selenides GaSe and InSe [

4,

33,

34].

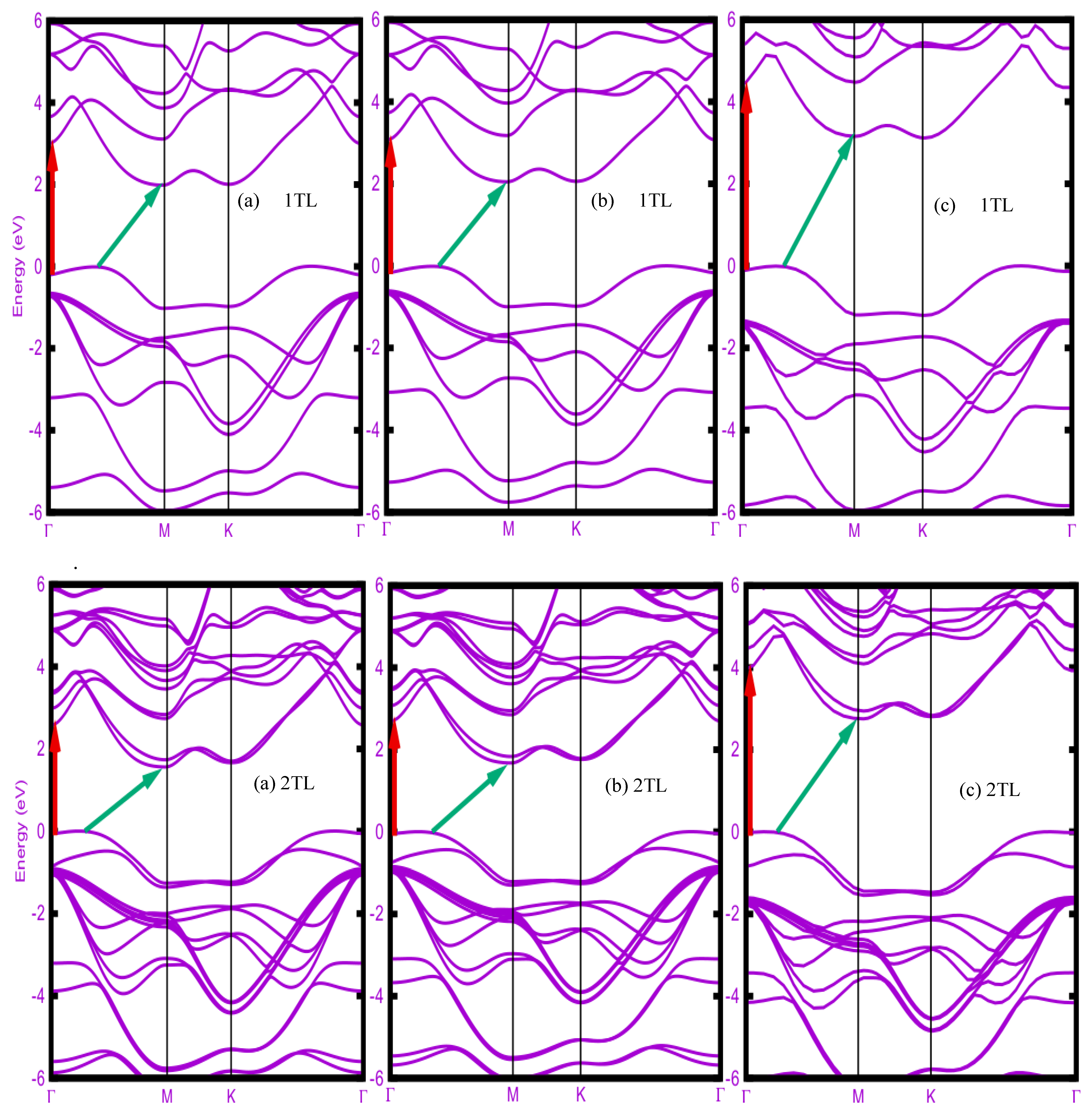

3.2. Band Structures

Figure 2 displays the electronic band structures in (a) LDA, (b) PBE, and (c) HSE06 quality of ε-stacked AlSe upon increasing number of tetralayers from 1TL, 2TL and 3TL to the bulk crystal. The atomic coordinates are derived either within LDA [case (a)] or within PBE+vdW [cases (b) and (c)]. The band dispersion is rather similar independent of the XC functional used. The number of bands follows the number of TLs in a primitive unit cell.

The conduction band minimum (CBM) appears for all considered system at the M point of the 2D or 3D hexagonal BZ. The valence band maximum (VBM) occurs on the ГM line, not on the ГK line as also found elsewhere [

10]. Its position moves toward the Г point with an increasing number of tetralayers along 1TL, 2TL and 3TL until the Г point for bulk ε-AlSe. The interband distances between conduction and valence bands vary with the number of tetralayers, with a decreasing of the gaps accompanying an increasing number of tetralayers. This is easily visible for the direct gap E

gdir and the indirect one E

gind. The indirect gap ГM

→M is always smaller than the direct gар Г

→Г. Consequently, all layered AlSe systems represent indirect semiconductors. A transition from an indirect to a direct character going from the few-layer systems semiconductor to the bulk, as in the cases of ß-InSe [

4] and ε-GaSe [

7], does not happen here since the CBM is found at M and not at Г.

The direct and indirect energy gaps in Table I do hardly vary between LDA and PBE. Surprisingly, the PBE values are slightly above the LDA ones. This is mainly a consequence of the overcompensation of gap underestimates of the two XC functionals and shorter bond lengths in LDA compared to PBE+vdW. The direct gaps are by about 1 eV larger than the indirect ones for all considered layered systems and independent of the XC functional. In the mono-tetralayer case the indirect gap agrees extremely well with values of about 2 eV from other PBE calculations [

8,

9,

10]. The inclusion of QP corrections in an approximate manner by applying the hybrid functional HSE06 significantly increases the direct and indirect gaps by 1-2 eV with the largest effect on 1TL. This QP increase is larger than found by other calculations [

10,

35].

4. Vibrational Frequencies and Spectra

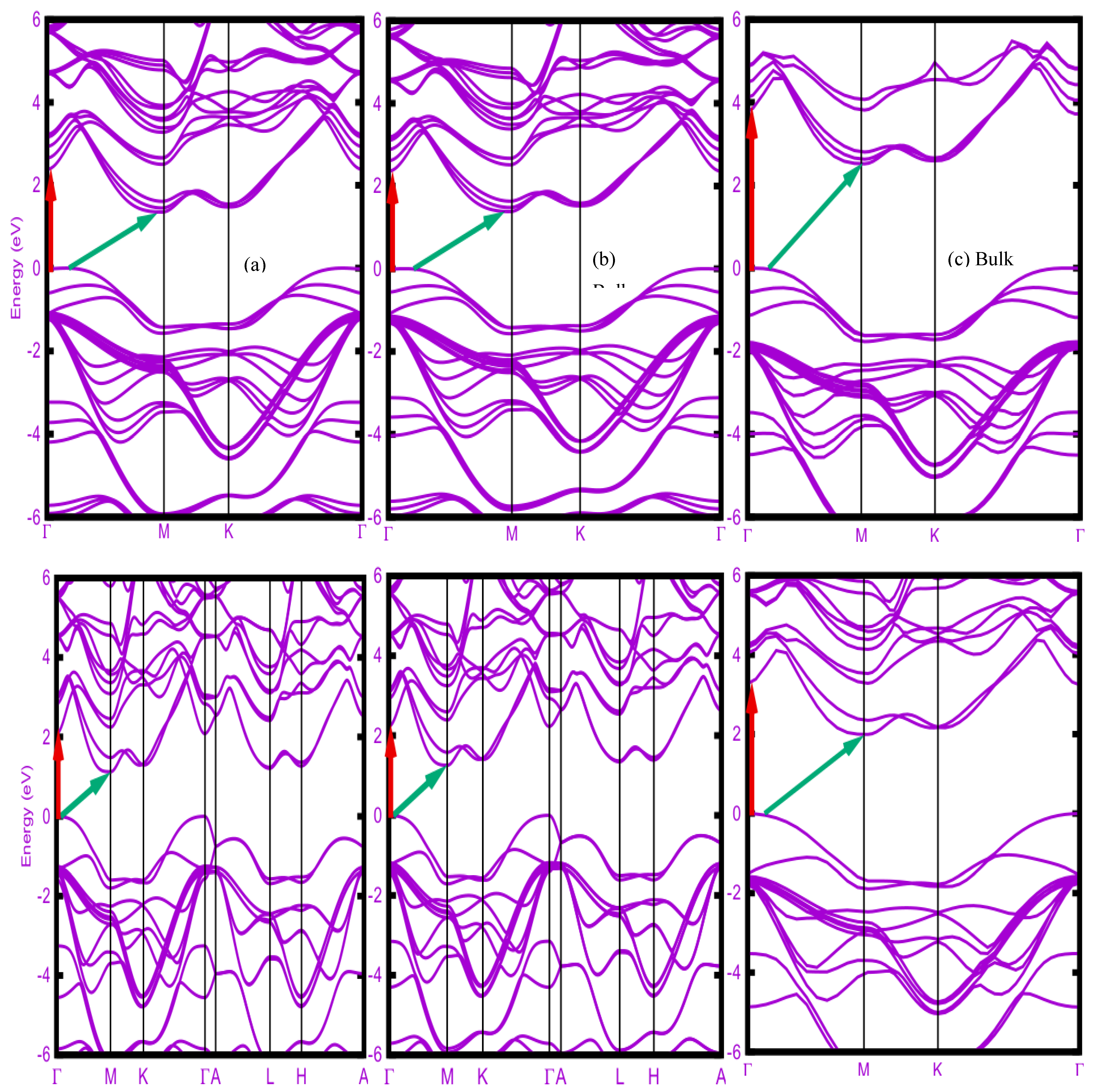

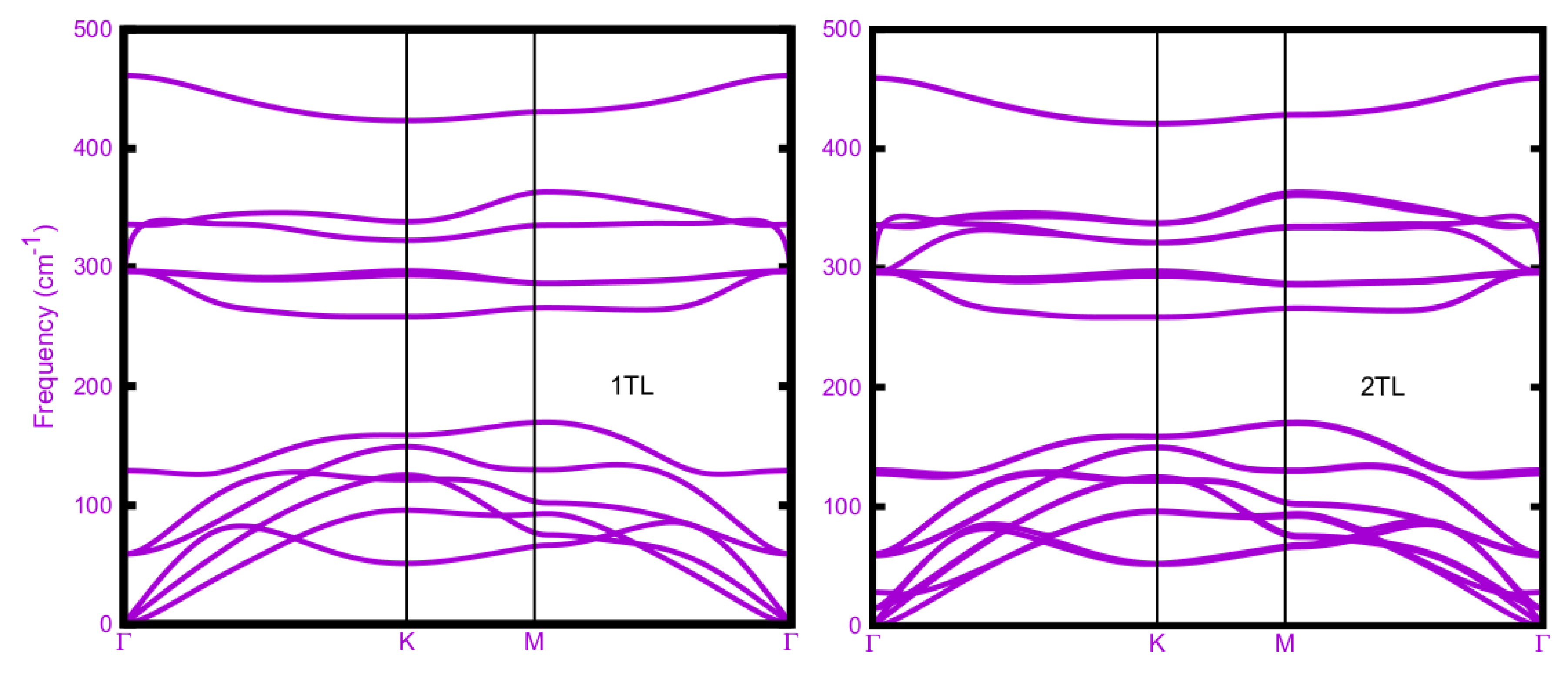

4.1. Phonon Branches

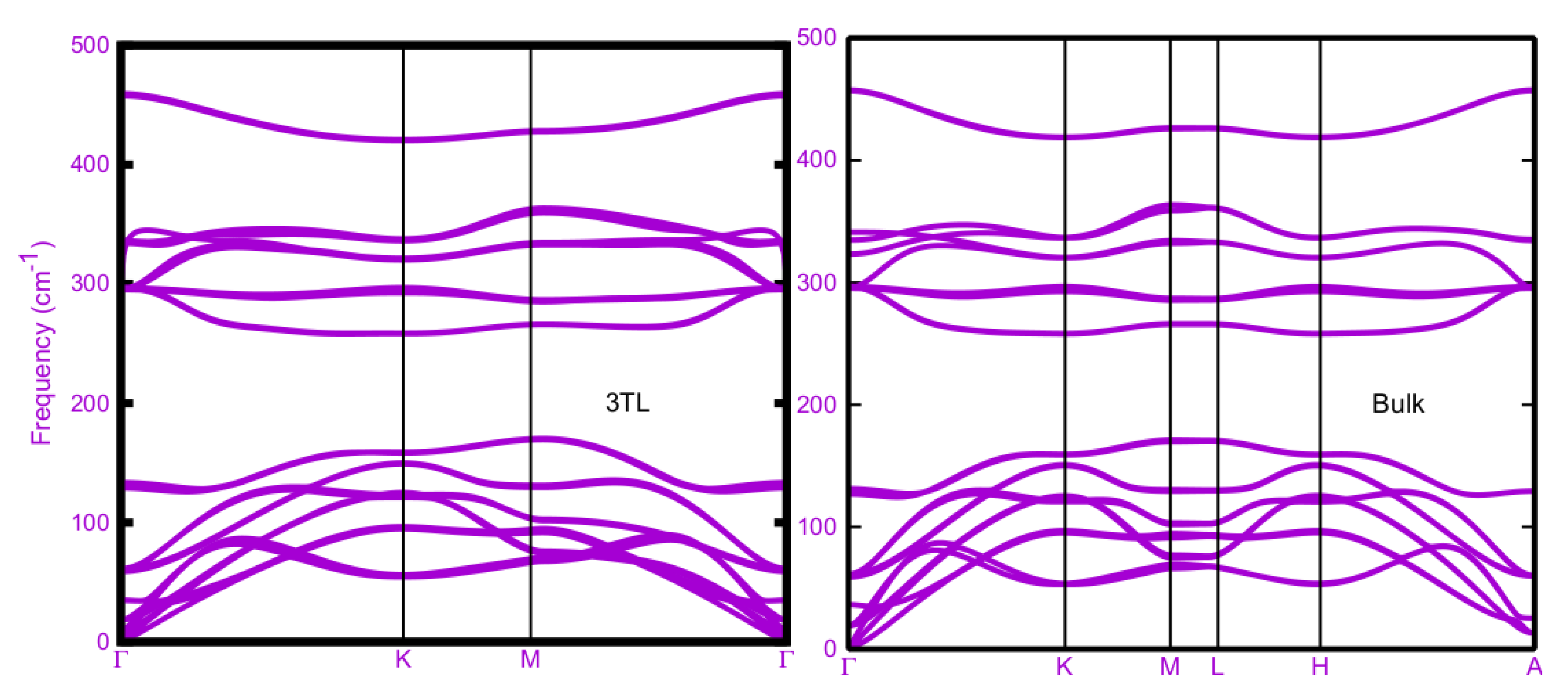

The phonon branches obtained within DFPT-LDA are plotted in

Figure 3 along the high-symmetry lines Г-K-M-Г in the 2D hexagonal BZ for tetralayer stacks and along the 3D hexagonal BZ high symmetry lines in the case of bulk ε-AlSe. All spectra show three groups of acoustic modes and energetically similar modes appear between 0-180 cm

-1. Three acoustic branches near Г approach zero for vanishing wave vector. A second bunch of optical modes is visible in the range 260-380 cm

-1. In addition, well isolated branches occur around 450 cm

-1 with almost vanishing dispersion. In general, the phonon branches are rather similar in the four AlSe structures. They mainly differ with respect to the number of TLs in a unit cell. The panels in

Figure 3 mainly vary with the number of phonon branches, 12 (1TL), 24 (2TL), 36 (3TL) and 24 (bulk). In addition, the various numbers of TLs give rise to small splittings describing the weak inter-TL interaction. In the bulk, additional modifications appear close to the BZ boundary. No vanishing or imaginary frequencies appears. This is a clear indication that all the four studied layered AlSe phases are also dynamically stable, in agreement with previous studies [

8,

24].

The mono-tetralayer AlSe is described by the space group D

13h (with the point group D

3h) [

7,

25,

31]. This symmetry also holds for the 3TL system [

7,

32]. We expect (2N A'

1+2NE") Raman-active optical modes, (2N-1) A"

2 IR-active optical modes and (2N-1) E' Raman- and IR-active optical modes with N=1, 3, as illustrated in Table II. In the 1TL monolayer case, there are two Al and two Se atoms in a primitive unit cell. Therefore, the phonon spectrum in

Figure 3 (upper left panel) totally includes 12 phonon branches, three acoustic and nine optical branches. As a 2D system the three acoustic modes contain two E' modes with linear dispersion near Г, the longitudinal acoustic (LA) and a transverse acoustic (TA) one, for in-plane vibrations. The third acoustic branch, the flexural one (ZA) with A"

2 symmetry describes out-of-plane vibrations. It goes quadratically which the vanishing wave vector to zero frequency at Г. The general behavior is similar for 2TL and 3TL but also for the bulk layered ε-AlSe crystal. In total the single tetralayer AlSe has eight (four double degenerate) in-plane modes, E' and E", and four (nondegenerate) out-of-plane ones, A'

1 and A"₂, according to the irreducible representation of its D

3h point group [

7,

31,

35]. The number of phonon branches follows the number atoms or TLs in the unit cell. Consequently, 12N branches are visible in the four panels of

Figure 3 according to the NTL layer system or the bulk with N=2 tetralayers in the unit cell. The used denotation, in particular for the Γ modes, follows the symmetry of the four considered structures.

The ε-stacked 2TL and bulk systems has a C

3v1 space group with the C

3v point group with six symmetry operations. It is not centrosymmetric. Nevertheless, the phonon branches in

Figure 3, upper and lower right panels, are rather similar to those observed for the 1TL and 2TL systems. The 24 Г modes can be decomposed into four groups of four doubly degenerate E modes and four nondegenerate A

1 modes as done in Table II. All the corresponding optical modes at Γ are both Raman- and IR-active [

7,

32] (see Table II). The symmetry lowering has, however, only a minor influence on the mode intensities.

4.2. Frequencies of Optical Г Modes

Results of DFPT calculations for vibrations with vanishing wave vector are summarized in Table II. The basic structure, the mono-tetralayer 1TL, has nine nondegenerate (A) and doubly degenerate (E) optical modes with frequencies 59 (E"), 129 (A'

1), 297 (E'), 297 (E"), 336 (A"₂) and 461 (A'

1) cm

-1, which can be also nearly observed in

Figure 3 (upper left panel). Because of the same symmetry the main effects of the inter TL interaction in the 3TL system are tiny splittings of the branches at Г resulting in by a factor 3 increased numbers of frequencies 11 (E"), 19 (E'), 35(A'

1) 35 (A"

2), 59 (E"), 60 (E'), 61 (E"), 129, 133 (A'

1+A"

2), 295, 296, 296, 296, 297, 297 (E'+E"), 334, 336 (A'

1+A"

2) and 336, 458, 459, 459 (A'

1+A"

2) cm

-1. The small frequency splitting of the same mode type of a somewhat less than 2 cm

-1 are due to the interlayer interaction. As visible in

Figure 3, lower left panel, below 59 cm

-1 further E'+E" modes at 19 and 11 cm

-1 as well two A'

1+A"

2 modes at 35, 35 cm

-1 occur compared to the 1TL case. Their wide spread frequency range may be explained by folding of acoustic branches due to the presence of three TLs instead of one.

Despite the lowering of the symmetry from D

3h to C

3v the two systems with two tetralayers in the unit cell, 2TL and bulk ε-AlSe, show a behavior between that of 1TL and 3TL (see

Figure 3, right panels). In Table II the listed optical phonons frequencies for 2TL are 15 (E), 28 (A

1), 59, 61 (E), 128, 130 (A

1), 296, 296, 297, 297 (E), 336, 336 (A

1) and 459, 459 (A

1). In the bulk case the frequencies are very similar with 19 (E'), 36 (A"

2), 59, 61 (E"), 127, 131 (A'

1), 295, 296, 296, 297 (E'+E"), 323, 335 (A"

2), and 457, 457 (A'

1). The extremely low frequency deviations above 59 cm

-1 again indicate the weak influence of the interlayer interaction. The deviations only slightly increase to 4-8 cm

-1 in the lower frequency range and somewhat less in the range of higher optical modes. In contrast to the frequencies the variation of the Raman- and IR-intensities are seemingly much stronger.

4.3. Raman and IR Spectra

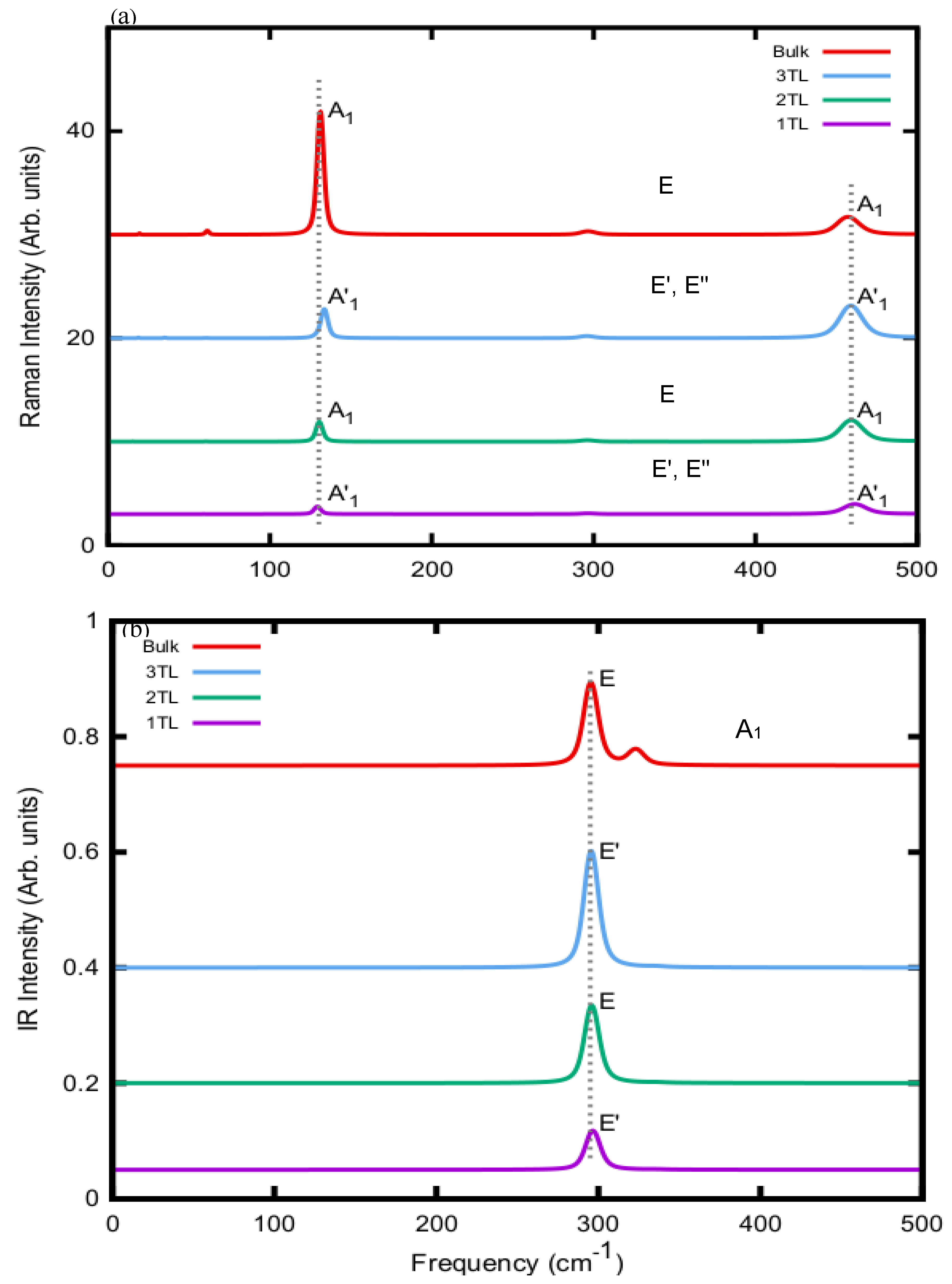

The optical Г modes listed with their frequencies in Table II also rule the Raman and IR spectra. For that reason, the calculated averaged Raman and IR intensities as listed in Table II are used to derive the spectra in

Figure 4. They widely follow the symmetry constraints discussed above with or without inversion symmetry.

The Raman spectra in

Figure 4 (a) show three main peaks, the very strong A'

1 modes in the 127-130 cm

-1 range and in the 457-461 cm

-1 region and a significantly weaker E', E" peak around 295-297 cm

-1. Exactly at this E' position also a peak occurs in the all four IR spectra, indicating that this mode is both Raman- and IR-active. Very similar Raman spectra are visible for all four systems. One visible effect is the broadening of the high-frequency A'

1 Raman peaks split by about 1 cm

-1 due to contribution of two (except in 1TL) strong Raman peaks. The peak shows a minor shift of about 4 cm

-1 going from bulk AlSe to 1TL. The larger splittings of the lower A'

1 modes around 130 cm

-1 is not really observable, because of the low intensity of the second mode of the same symmetry (see Table II). The two systems with two tetralayers in the unit cell, 2TL and bulk, exhibit similar peak positions but modified intensities. In the bulk case the lower Raman peak possesses heights intensity compared to the other bulk AlSe geometries. The in-plane E' and E" modes give rise only to a very weak Raman peak somewhat below 300 cm

-1. The IR spectra in

Figure 4 (b) essentially show only one strong peak around 296 cm

-1 due to E' (or E) modes, which are both Raman- and IR-active. Its frequency shift with the number of TLs is negligibly small. There is only a variation of the intensity with the TLs. In contrast to the few-layer TL systems the bulk

ɛ-AlSe system displays a second IR peak at about 323 cm

-1, which is related to one A'

1 mode with a substantial IR intensity (see Table II). The appearance of this peak in a measured spectrum may be interpreted to the formation of a multi-TL or bulk AlSe system with

ɛ stacking. In addition, for comparison with experiments we have to mention that, in general, the Raman tensor significantly depends on the light polarizations, and on the symmetry of the vibrational mode [

35]. The spectra in

Figure 4 (a), however, display averages.

5. Summary and Conclusions

In this paper we have investigated the atomic geometries together with the resulting band structures and vibrational properties of ε-stacked few-tetralayer systems, 1TL, 2TL and 3TL of AlSe by means of density functional and density functional perturbation theory. In the electronic structure case, we accounted for excited-state quasiparticle corrections in an approximate way by applying a hybrid XC functional. For comparison, the same quantities and properties as for the layered systems have been calculated for the bulk ε-AlSe polytype.

We found that all these AlSe structures are not only statically, but also dynamically stable. The interaction between the Se-Al-Al-Se tetralayers is attractive. Consequently, the total energies per TL lower with the number of TLs and reach the deepest value for bulk ε-AlSe. The structural results do not significantly depend on the chosen XC functional. However, the typical overestimation (underestimation) of the chemical bonding using LDA (PBE) is observed also after inclusion of vdW interaction in the PBE functional.

The band structures of all AlSe systems studied clearly indicate indirect semiconductors with the conduction band minimum at M, while the valence band maximum appears at the ГM line and moves toward the Г point with rising number of tetralayers. This fact is observed independently of the XC functional. The application of the HSE06 hybrid functional, however, widens the fundamental energy gaps between the lowest conduction and highest valence band significantly, by 1-2 eV, independently of the number of layers. The largest quasiparticle shift happens for 1TL.

The phonon branches and corresponding Raman and IR intensities show strong similarities with results for other monoselenides. Mainly the scaling with the lighter mass of Al in comparison to Ga and In has to be taken in consideration. In addition, we predicted Raman and IR spectra for the AlSe systems. We observed minor splittings, and sizeable intensity changes, with the number of tetralayers. Our results shows that AlSe behaves similarly to GaSe and InSe, with minor modifications due to the actual AC stacking, i.e., the symmetry.

References

- Gupta, T. Sakthivel, and S. Seal, Progress in Materials Science 73, 44 (2015).

- H. Cai, Y. Gu, Y.-C. Lin, Y. Yu, D. B. Geohegan, and K. Xiao, Applied Physics Reviews 6 (2019).

- D. K. Sang, H. Wang, M. Qiu, R. Cao, Z. Guo, J. Zhao, Y. Li, Q. Xiao, D. Fan, and H. Zhang, Nanomaterials 9, 82 (2019).

- M. Bejani, O. Pulci, N. Karimi, E. Cannuccia, and F. Bechstedt, Physical Review Materials 6, 115201 (2022).

- A. K. Geim and K. S. Novoselov, Nature Materials 6, 183 (2007).

- W. S. Yun, S. W. Han, S. C. Hong, I. G. Kim, and J. D. Lee, Physical Review B 85, 033305 (2012).

- M. Bejani, O. Pulci, J. Barvestani, A. S. Vala, F. Bechstedt, and E. Cannuccia, Physical Review Materials 3, 124003 (2019).

- X. Chen, Y. Huang, J. Liu, H. Yuan, and H. Chen, ACS Omega 4, 17773 (2019).

- G. S. Khosa, S. Kumar, S. Gupta, and R. Kumar, Pramana 96, 124 (2022).

- Z. Haman, N. Khossossi, M. Kibbou, I. Bouziani, D. Singh, I. Essaoudi, A. Ainane, and R. Ahuja, Applied Surface Science 556, 149561 (2021).

- J. F. Sánchez-Royo, G. Muñoz-Matutano, M. Brotons-Gisbert, J. P. Martínez-Pastor, A. Segura, A. Cantarero, R. Mata, J. Canet-Ferrer, G. Tobias, E. Canadell et al., Nano Research 7, 1556 (2014).

- P. Hohenberg and W. Kohn, Physical Review 136, B864 (1964).

- W. Kohn and L. J. Sham, Physical Review 140, A1133 (1965).

- J. P. Perdew, K. Burke, and M. Ernzerhof, Physical Review Letters 77, 3865 (1996).

- P. Giannozzi, O. Andreussi, T. Brumme, O. Bunau, M. Buongiorno Nardelli, M. Calandra, R. Car, C. Cavazzoni, D. Ceresoli, M. Cococcioni et al., J Phys Condens Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

- S. Grimme, J. Antony, S. Ehrlich, and H. Krieg, J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

- F. Bechstedt, Many-Body Approach to Electronic Excitations, Springer, Berlin, (2015).

- J. Heyd, G. E. Scuseria, and M. Ernzerhof, J. chem. Phys. 118, 8207 (2003).

- J. Heyd, G. E. Scuseria, and M. Ernzerhof, J. chem. Phys. 124, 219906 (2006).

- H. J. Monkhorst and J. D. Pack, Physical Review B 13, 5188 (1976).

- S. Baroni, S. de Gironcoli, A. Dal Corso, and P. Giannozzi, Reviews of Modern Physics 73, 515 (2001).

- T. Pandey, D. S. Parker, and L. Lindsay, Nanotechnology 28, 455706 (2017).

- A. Shafique and Y.-H. Shin, Scientific reports 10, 1093 (2020).

- S. Demirci, N. Avazlı, E. Durgun, and S. Cahangirov, Physical Review B 95, 115409 (2017).

- M. K. Niranjan, Physical Review B 103, 195437 (2021).

- R. D. Rodriguez, S. Müller, E. Sheremet, D. R. T. Zahn, A. Villabona, S. A. López-Rivera, and P. Tonndorf, J. Vac. Sci. Technol B 32, 04E106 (2014).

- N. Curreli, M. Serri, M. I. Zappia, D. Spirito, G. Bianca, J. Buha, L. Najafi, Z. Sofer, R. Krahne, V. Pellegrini et al., Adv. Electron. Mater. 7, 2001080 (2021).

- R. M. Hoff, J. C. Irwin, and R. M. A. Lieth, Can. J. Phys. 53, 1606 (1975).

- A. Politano, D. Campi, M. Cattelan, I. Ben Amara, S. Jaziri, A. Mazzotti, A. Barinov, B. Gürbulak, S. Duman, S. Agnoli et al., Scientific reports 7, 3445 (2017).

- L. Kang, L. Shen, Y. J. Chen, S. C. Sun, X. Gu, H. J. Zheng, Z. K. Liu, J. X. Wu, H. L. Peng, F. W. Zheng et al., Physical Review Materials 4, 124604 (2020).

- R. Longuinhos and J. Ribeiro-Soares, Physical Review Applied 11, 024012 (2019).

- R. Longuinhos and J. Ribeiro-Soares, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 18, 25401 (2016).

- A. V. Kosobutsky, Science Evolution 2, 11 (2017).

- D. Wines, K. Saritas, and C. J. T. J. o. c. p. Ataca, J. Chem. Phys. 153 154704 (2020).

- M. Demirtas, M. J. Varjovi, M. M. Cicek, and E. Durgun, Physical Review Materials 4, 114003 (2020).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).