1. Introduction

In the year 2020, there were more than 370,000 new cases of oral cancer that were detected, and the disease was responsible for more than 170,000 fatalities [

1,

2,

3]. Oral cancer screening programs are an essential alternative for reducing the death rate associated with oral cancer. Both Sankaranarayanan (2013) and Rajaraman (2015) agree with the assertion that oral cancer screening programs contribute to a decrease in the mortality rate associated with oral cancer [

4,

5]. According to Chuang (2017), there is a significant reduction in the death rate of oral cancer in stages III and IV, with a relative risk of 0.53 [

6]. Smoking cigarettes, chewing betel quid, drinking alcohol, oral infections, and oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) are the leading causes of oral cancer [

7,

8,

9]. Oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs) are a group of conditions in the mouth that have a higher risk of developing into oral cancer, including leukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucous fibrosis, lichen planus, and actinic cheilitis. These disorders manifest as various types of lesions or abnormalities in the oral mucosa and serve as early warning signs for potential oral cancer, particularly squamous cell carcinoma. Common risk factors for OPMDs include tobacco use, alcohol consumption, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, and a diet low in fruits and vegetables. Regular monitoring, biopsy, and histopathological examination are essential for managing these disorders and intervening early if malignant transformation occurs [

10,

11,

12]. The oral cancer screening program aims to both diagnose oral cancer at an early stage and provide education to participants regarding the risk factors and behaviors associated with oral cancer. It will be interesting to monitor the alterations in participants' behavior following the completion of this program.

Because of the ever-changing nature of human beings, conduct can shift throughout the course of time. The purpose of this study is to investigate the possibility of individuals changing their behaviors of smoking and chewing betel quid, as well as the characteristics, such as gender, age, level of education, and health issues, that are likely to have an effect on an individual's ability to change those behaviors.

The analysis of projected oral behavior changes across different severity levels, along with the identification of associated factors, can help developing coping strategies and improving screening programs. This information would be valuable for the participants, especially for those exhibiting the most adverse behavior patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Collection

Since 2004, Taiwanese citizens have undergone biennial screenings for oral neoplasia as part of an initiative aimed at reducing the incidence and mortality rates associated with oral cancer. This screening program is connected to the National Cancer Registry, facilitating the retrieval of information regarding screening results, intervals, detection methods, and the stage of oral cancer. Demographic characteristics and the survival status of patients with oral cancer were obtained from the National Death Registry, utilizing codes from the International Classification of Diseases. Chuang (2017) delineated the coding issues and specifics related to this screening process. Through face-to-face interviews conducted in communities and hospitals, a questionnaire was employed to gather information on demographic characteristics and either cigarette consumption or betel quid chewing. Participants underwent visual examinations of their oral cavity administered by dentists or physicians with appropriate training for Oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMD) encompassing clinical diagnoses such as oral leukoplakia, erythroleukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucous fibrosis, and verrucous hyperplasia [

6].

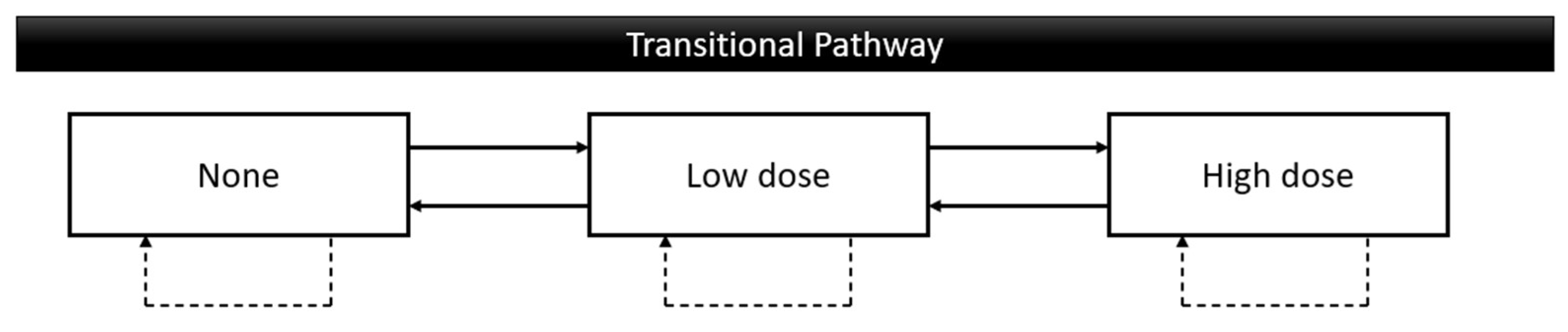

This study uses data from about 2.57 million participants from the Taiwan Oral Cancer Screening program from 2010 to 2021 aged 30 years over and attended at least two times. The data involved oral behaviors, age, gender, education level, living area, screening place, and OPMDs. Education of oral cancer risks was done as a part of the screening program to follow up on their effectiveness the oral behavior changes were collected every time of screening. The possible behavior changes included unchanged, none to low dose, none to high doses, low dose to none, low dose to high dose, high dose to none, and high dose to low dose. These 3 levels of the possible pathway of both smoking and betel quid chewing are definite as none: never use or cessation, low dose: using less than twenty values per day, high dose: using over twenty values per day (

Figure 1).

2.2. Statistical Analysis

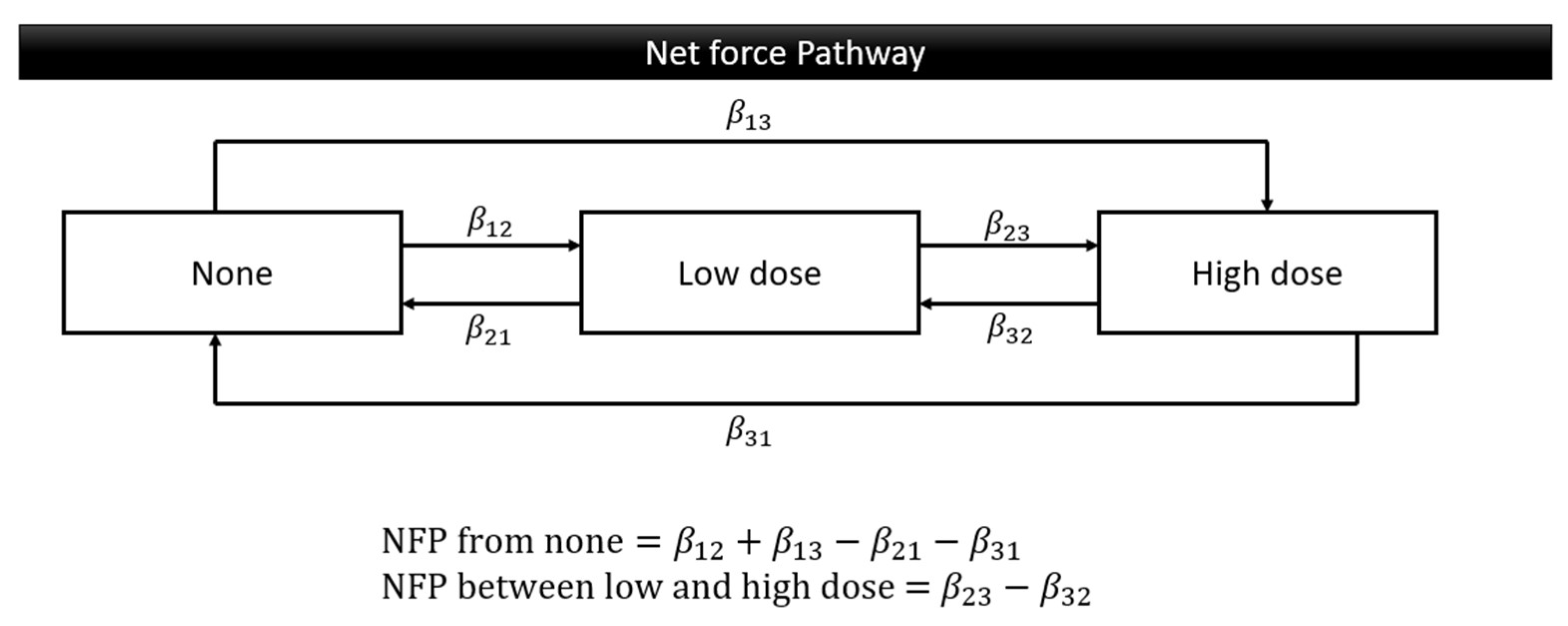

The demographics of this data; gender, age group, education level, living area, screening place, OPMDs, and oral cancer were summarized as frequency and percent. The Markov chain model provides an investigation of the transitional probability whether deteriorating, maintaining, or improving. Using the exponential regression form representing behavior weights for respective progression and regression, we translated three transition parameters into two patterns of Net Force Progression (NFP): NFP from none and NFP between low and high doses. The NFP from none was calculated by subtracting any regressions to the none stage from progressions from the none stage. This was done to analyze the tendency to initiate oral risky behavior compared to ceasing such behavior. The NFP between low and high doses was determined by subtracting the regressions from high to low dose from the progressions from low to high dose, to study trends in increasing or decreasing the daily dosage of oral risky behaviors (

Figure 2). The SAS version 9.4 software was used for all analyses in this study.

3. Results

Table 1 comprehensively summarizes the proportion of smoking and betel quid chewing behaviors among different demographic categories. Among the male participants, 20.6% stated that they did not smoke, 47.7% reported smoking a small amount, and 31.7% reported smoking a large amount. In addition, 75.1% reported not chewing betel quid, 17.7% reported chewing a small amount, and 7.3% reported chewing a large amount. The aggregate number of male participants amounted to 2,190,949. Out of the female participants, 32.7% stated that they did not smoke, 52.5% reported smoking a small amount, and 14.8% reported smoking a large amount. Additionally, 85.7% indicated that they did not chew betel quid, while 10.9% reported chewing a small amount and 3.4% reported chewing a large amount. There was a total of 387,296 female participants. The study found that those under 61 reported the following rates: 16.6% did not smoke, 51.8% smoked a low amount, and 31.6% smoked a high amount. Additionally, 74.3% did not chew betel quid, 18.2% chewed a low amount, and 7.5% chewed a high amount. The aggregate number of individuals in this specific age category amounted to 1,877,590. Individuals who were 61 years old or older said that 38% did not smoke, 39.2% smoked a small amount, and 22.8% smoked a large amount. Additionally, 83% did not chew betel quid, 12.5% chewed a small amount, and 4.5% chewed a large amount. The overall number of participants in this age category amounted to 700,655. Individuals who had completed elementary and middle school education reported the following percentages: 29.3% did not smoke, 40.9% smoked a low amount, and 29.8% smoked a high amount. In addition, 74.8% did not chew betel quid, 16.9% chewed a low amount, and 8.3% chewed a large amount. The total number of participants in this category with a low level of education was 515,778. Participants who had completed high school or higher education reported the following percentages: 17.5% did not smoke, 54.5% smoked a small amount, and 28% smoked a large amount. In addition, 79.9% did not chew betel quid, 15% chewed a small amount, and 5.1% chewed a large amount. The aggregate number of individuals in this higher education cohort amounted to 860,054. 18.3% of people living in urban areas reported not smoking, 52% reported smoking a low amount, and 29.7% reported smoking a high amount. Additionally, 80.8% reported not chewing betel quid, 14% reported chewing a low amount, and 5.2% reported chewing a high amount. The urban population amounted to 1,609,524 individuals. The rural population reported the following percentages: 29.2% abstained from smoking, 42.5% smoked low-dose, and 28.3% smoked high-dose. Additionally, 69.9% did not chew betel quid, while 21% engaged in low-dose chewing and 9.1% engaged in high-dose chewing. The rural population amounted to 968,718 individuals. The participants surveyed at large hospitals indicated the following percentages: 22.3% reported not smoking, 49.2% reported smoking in low doses, and 28.5% reported smoking in high doses. Additionally, 78.2% reported not chewing betel quid, 15.5% reported chewing it in low doses, and 6.2% reported chewing it in high doses. There was a total of 726,200 participants in large hospitals. The surveyed participants in small hospitals indicated the following percentages: 22.4% reported not smoking, 48.1% reported smoking a low amount, and 29.5% reported smoking a high amount. In addition, 76.1% reported not chewing betel quid, 17.1% reported chewing a low amount, and 6.8% reported chewing a high amount. The aggregate number of participants at small hospitals amounted to 1,851,831. The participants who screened positive for OPMD reported the following percentages: 15% did not smoke, 42.2% smoked a low dosage, and 42.8% smoked a high dose. Additionally, 59.8% did not chew betel quid, 23.9% chewed a moderate dose, and 16.3% chewed a high dose. A total of 193,256 people reported being positive during the initial screening. The participants who screened negative for OPMD on the screening reported the following percentages: 23% did not smoke, 48.9% smoked a low amount, and 28.1% smoked a high amount. Additionally, 78% did not chew betel quid, 16.1% chewed a low amount, and 5.9% chewed a high amount. The negative screening findings were noticed by 2,384,989 participants.

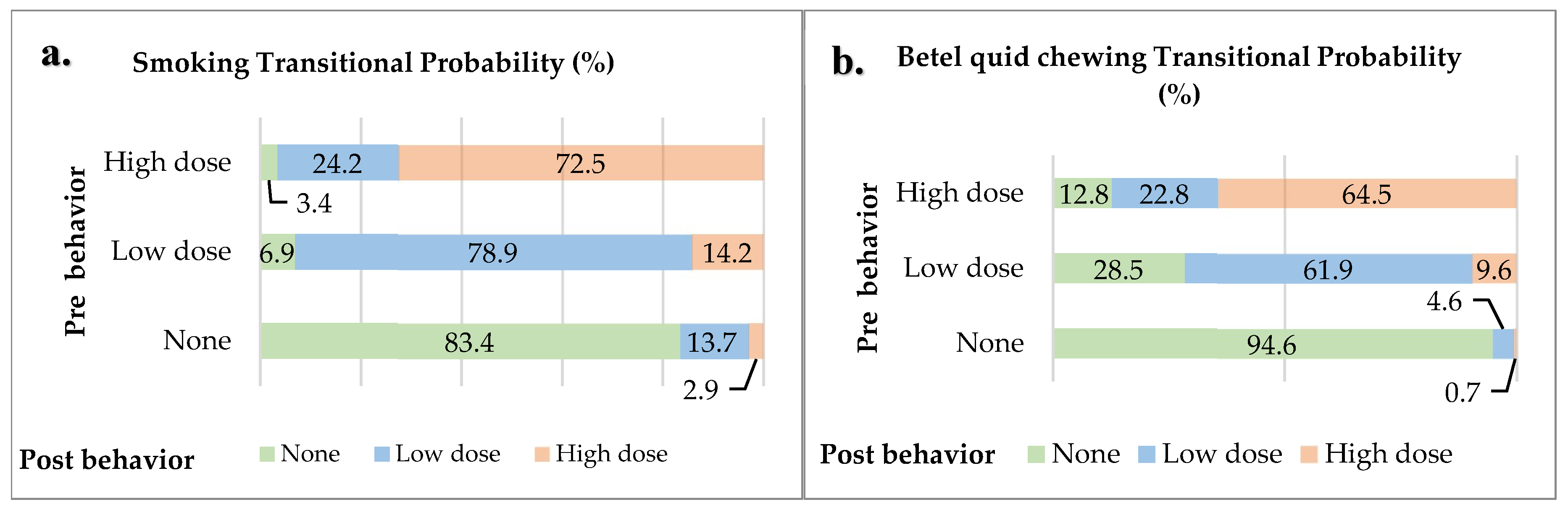

3.1. Transitional Probability

The Markov chain model shows the probability of behavior change after participating in the oral cancer screening program for the groups categorized as none, low dose, and high dose. The probability of change for non-smokers was found to be 83.4% remaining non-smokers, 13.7% starting to smoke at a low dose, and 2.9% starting to smoke at a high dose. The probability of change for low-dose smokers was found to be 78.9% continuing to smoke at a low dose, 14.2% increasing to a high dose, and 6.9% quitting smoking. The probability of change for high-dose smokers was found to be 72.5% continuing to smoke at the same level, 24.2% reducing to a low dose, and 3.4% quitting smoking. The probability of change for non-betel quid chewers was found to be 94.6% remaining non-chewers, 4.6% starting to chew at a low dose, and 0.7% starting to chew at a high dose. The probability of change for low-dose betel quid chewers was found to be 61.9% continuing to chew at a low dose, 28.5% quitting chewing, and 9.6% increasing to a high dose. The probability of change for high-dose betel quid chewers was found to be 64.5% continuing to chew at a high dose, 22.8% reducing to a low dose, and 12.8% quitting chewing (

Figure 3).

3.2. Effect Risk Factors on Multiple Transitions for Smoking Behavior

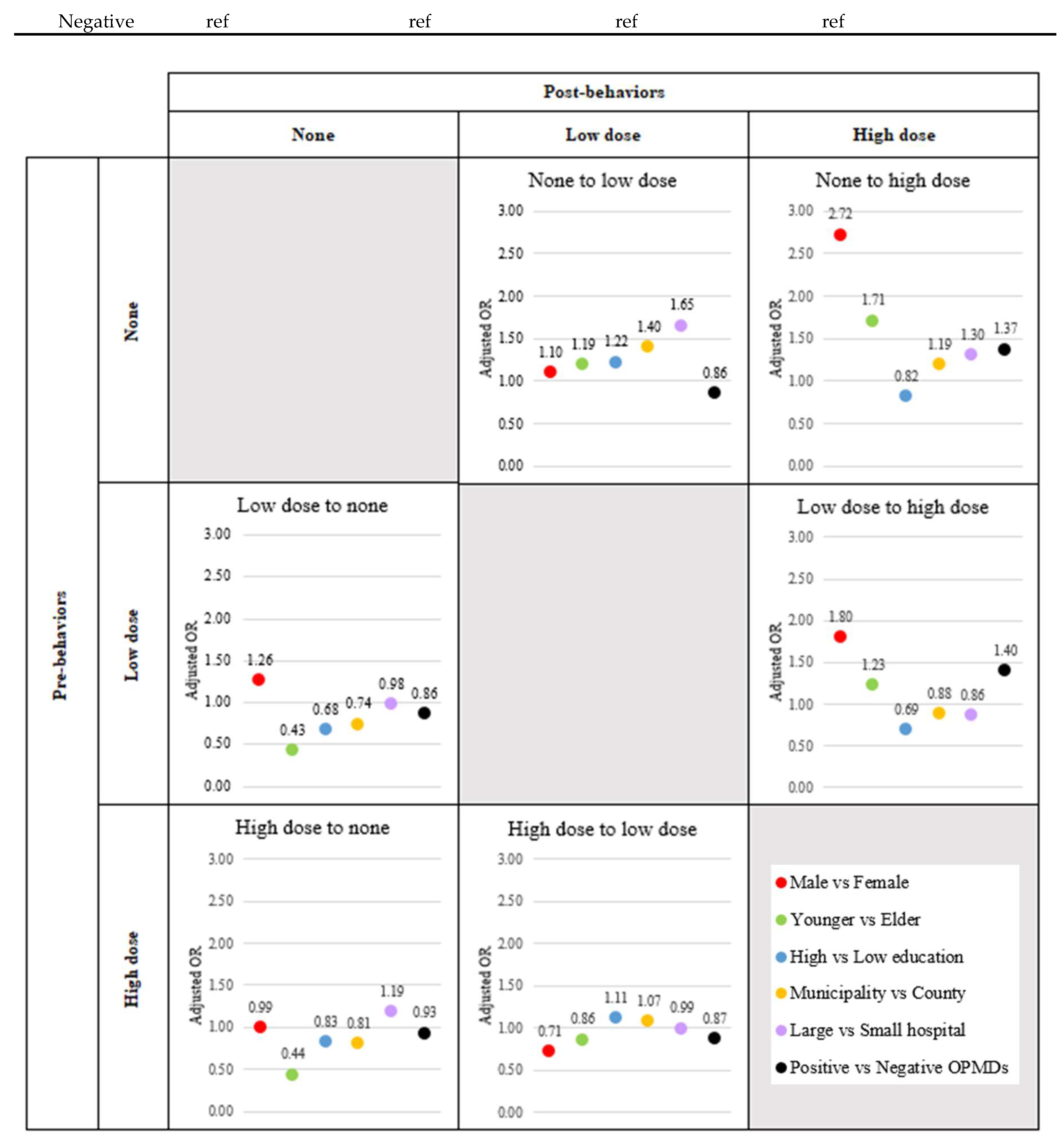

Table 2 shows the adjusted relative risk (aRR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) regarding the effect of each factor on Net Force Progression (NFP) by considering all risk factors. Men were at increased risk for both NFP from none and NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 2.4 (2.26-2.57) and 2.53 (2.49-2.56), respectively. Considering stage by stage, it was found that only the reduction in smoking among the high dose group was not significantly influenced by males, with an aRR of 0.71 (95% CI: 0.70-0.72) (

Figure 4,

Supplementary Table S1). Younger people were at increased risk for both NFP from none and NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 10.85 (10.53-11.17) and 1.43 (1.42-1.45), respectively. Considering stage by stage, it was found that younger people could not induce the cessation of smoking or dose reduction. The adjusted relative risks (aRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were as follows: for the transition from low dose to none, the aRR was 0.43 (95% CI: 0.42-0.434); for the transition from high dose to none, the aRR was 0.44 (95% CI: 0.43-0.45); and for the transition from high dose to low dose, the aRR was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.85-0.87) (

Figure 4,

Supplementary Table S1). High education was at increased risk for NFP from none at aRR (95%CI) 1.8 (1.74-1.86), however, high education was inversely associated with risk for NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 0.63 (0.62-0.631). Considering stage by stage, it was found that high education induced the transformation from none to low dose and from high to low dose. The adjusted relative risks (aRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were 1.22 (95% CI: 1.21-1.24) for the transition from none to low dose, and 1.11 (95% CI: 1.09-1.12) for the transition from high to low dose (

Figure 4,

Supplementary Table S1). Urban living was at increased risk for NFP from none at aRR (95%CI) 2.77 (2.7-2.84), however, urban living was inversely associated with risk for NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 0.83 (0.82-0.84). Considering stage by stage, it was found that urban living could enhance behavior improvement only in the transition from high dose to low dose, with an adjusted relative risk (aRR) of 1.07 (95% CI: 1.06-1.08) (

Figure 4,

Supplementary Table S1). Screening in the large hospital was at increased risk for NFP from none at aRR (95%CI) 1.86 (1.8-1.91), however, screening in the large hospital was inversely associated with risk for NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 0.87 (0.86-0.88). Considering stage by stage, it was found that screening in large hospitals could enhance smoking cessation only in high dose smokers, with an adjusted relative risk (aRR) of 1.19 (95% CI: 1.16-1.21) (

Figure 4,

Supplementary Table S1). Positive finding of OPMDs was at increased risk for both NFP from none and NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 1.46 (1.4-1.53) and 1.61 (1.59-1.63), respectively. Considering stage by stage, it was found that a positive OPMD enhanced the development to high dose smoking. The adjusted relative risks (aRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were 1.37 (95% CI: 1.32-1.43) for the transition from none to high dose, and 1.4 (95% CI: 1.37-1.42) for the transition from low to high dose (

Figure 4,

Supplementary Table S1).

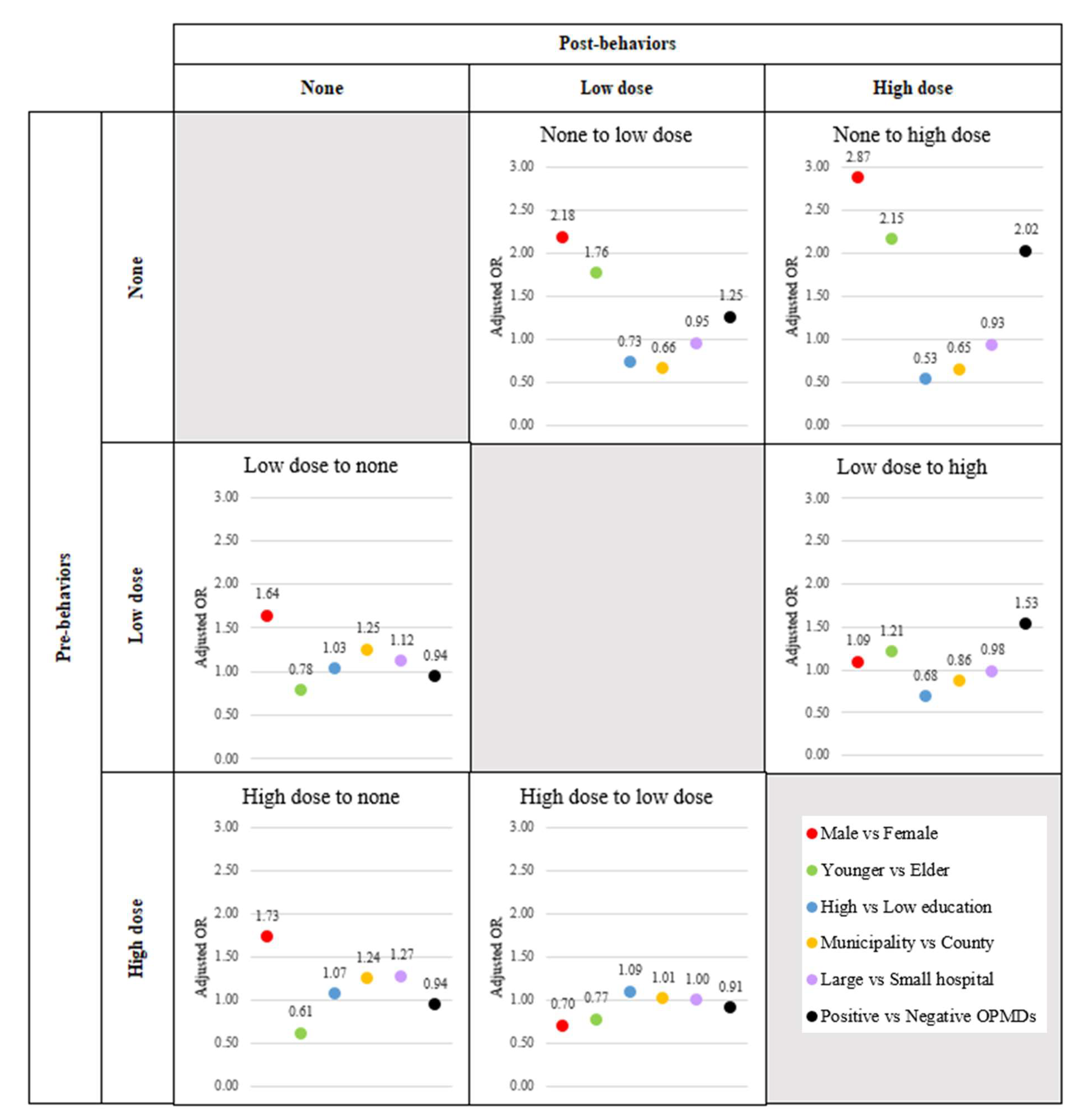

3.3. Effect Risk Factors on Multiple Transitions for Betel Quid Chewing Behavior

Table 3 shows the adjusted relative risk (aRR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) regarding the effect of each factor on Net Force Progression (NFP) by considering all risk factors. Men were at increased risk for both NFP from none and NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 2.21 (2.09-2.37) and 1.57 (1.53-1.62), respectively. Considering stage by stage, it was found that only the reduction in betel quid chewing among high dose group was not significantly influenced by males with aRR of 0.7 (95% CI: 0.67-0.72) (

Figure 5,

Supplementary Table S2). Younger people were at increased risk for both NFP from none and NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 7.93 (7.66-8.2) and 1.58 (1.54-7.62), respectively. Considering stage by stage, it was found that younger people could not induce the cessation of betel quid chewing or dose reduction. The adjusted relative risks (aRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were as follows: for the transition from low dose to none, the aRR was 0.78 (95% CI: 0.77-0.79); for the transition from high dose to none, the aRR was 0.61 (95% CI: 0.59-0.63); and for the transition from high dose to low dose, the aRR was 0.77 (95% CI: 0.75-0.79) (

Figure 5,

Supplementary Table S2). High education was inversely associated with risk for both NFP from none and NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 0.35 (0.34-0.36) and 0.62 (0.61-0.64), respectively. Considering stage by stage, it was found that high education could induce the cessation of betel quid chewing and dose reduction. The adjusted relative risks (aRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were as follows: for the transition from low dose to none, the aRR was 1.03 (95% CI: 1.02-1.05); for the transition from high dose to none, the aRR was 1.07 (95% CI: 1.04-1.1); and for the transition from high dose to low dose, the aRR was 1.09 (95% CI: 1.06-1.12) (

Figure 5,

Supplementary Table S2). Urban living was inversely associated with risk for both NFP from none and NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 0.28 (0.27-0.29) and 0.85 (0.83-0.87), respectively. Considering stage by stage, it was found that high education could induce the cessation of betel quid chewing and dose reduction. The adjusted relative risks (aRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were as follows: for the transition from low dose to none, the aRR was 1.25 (95% CI: 1.24-1.26); for the transition from high dose to none, the aRR was 1.24 (95% CI: 1.21-1.26); and for the transition from high dose to low dose, the aRR was 1.01 (95% CI: 0.98-1.03) (

Figure 5,

Supplementary Table S2). Screening in large hospital was inversely associated with risk for NFP from none significantly and NFP between low and high dose non-significantly at aRR (95%CI) 0.62 (0.6-0.64) and 0.98 (0.95-1), respectively. Considering stage by stage, it was found that high education could induce the cessation of betel quid chewing and dose reduction. The adjusted relative risks (aRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were as follows: for the transition from low dose to none, the aRR was 1.12 (95% CI: 1.11-1.13); and for the transition from high dose to none, the aRR was 1.27 (95% CI: 1.25-1.3) (

Figure 5,

Supplementary Table S2). Positive findings of OPMDs was at increased risk for both NFP from none and NFP between low and high dose at aRR (95%CI) 2.87 (2.76-2.99) and 1.68 (1.63-1.72), respectively. Considering stage by stage, it was found that positive findings of OPMDs could not induce the cessation of betel quid chewing or dose reduction. The adjusted relative risks (aRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were as follows: for the transition from low dose to none, the aRR was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.92-0.95); for the transition from high dose to none, the aRR was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.92-0.96); and for the transition from high dose to low dose, the aRR was 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89-0.93) (

Figure 5,

Supplementary Table S2).

4. Discussion

A study shows that most people do not change their behavior. It found that smoking cessation occurs in less than 10% of cases, while cessation of betel quid chewing occurs in more than 10%. In the group that starts with low-dose smoking, there is a higher rate of progressive transition than cessation. Conversely, in the group that starts with low-dose betel quid chewing, cessation is more common than progressive transition. Considering the factors influencing behavior change can enhance our understanding and promote future behavior improvement.

4.1. Smoking

This study demonstrated that individuals diagnosed with OPMD are more inclined to encourage smoking initiation among non-smokers rather than assisting current smokers in their efforts to quit. A previous study of the identical dataset examined the improvements in behavior between the initial and final screenings. It revealed that those who smoked only experienced improvement as a result of positive OPMD (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.18, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.16-1.2). During this study, an extensive analysis was conducted on individuals who only smoked. The results revealed that positive OPMD (oral potentially malignant disorder) only led to smoking cessation in the high-dose group (

Supplementary Table S3). Nevertheless, the NFP revealed that smoking only does not lead to behavioral improvement in individuals with positive OPMD. The key difference between these two researches was the time taken: this study observed alterations in behavior every two years, whereas the previous one had a wider interval. Thus, it was hypothesized that positive OPMD alone does not have the ability to alter behavior, but positive OPMD combined with enough duration (exceeding two years) can. A study conducted in Korea also found that illness could significantly induce smoking improvement, with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 1.4 (95% CI: 1.07-1.85) for hypertension and 1.68 (95% CI: 1.03-2.75) for cardiovascular disease. However, cancer was found to non-significantly induce smoking improvement, with an aOR of 4.63 (95% CI: 0.9-23.93) [

13].

This study showed that males are more inclined to encourage smoking initiation among non-smokers rather than assisting current smokers in their efforts to quit. Previous studies did not find that males influence smoking behavior modification, with non-significant adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) of 0.96 (0.78-1.17) for the United States [

14] and 0.81 (0.43-1.5) for China [

15].

This study demonstrated that younger individuals are more likely to encourage non-smokers to start smoking rather than aiding smokers in quitting. However, previous studies conducted in the US, China, and Korea found that age did not significantly impact smoking behavior modification. The adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) for smoking cessation were 1.19 (0.96-1.47) for younger individuals in the US [

14], 0.94 (0.4-2.23) for the elderly in China [

15], and 2.35 (0.48-11.45) for the elderly in Korea [

16].

This study demonstrated that individuals with higher education are more likely to encourage non-smokers to start smoking rather than helping current smokers quit. However, higher education can also promote a reduction in smoking dosage. Previous studies have shown that higher education significantly influences smoking behavior modification, with adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) of 3.19 (1.02-9.98) in Korea [

16] and 0.54 (0.4-0.71) in Pakistan for smoking prevalence [

17]. Considering the results of this study, it is suggested that the increased difficulty associated with higher education may lead individuals to rely on smoking to alleviate stress. Nonetheless, higher educational attainment can also enhance awareness and understanding of the dangers of smoking, thereby encouraging individuals to reduce and control their smoking levels.

This study demonstrated that urban living is more likely to encourage non-smokers to start smoking rather than aiding current smokers in quitting. However, urban living can also promote a reduction in smoking dosage. Supporting this, a study in Pakistan found that residing in urban areas induced smoking spread, with an adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) of 1.55 (1.28-1.87). Considering the results of this study, it is suggested that living in urban areas, where people often face higher stress levels, intense competition, and greater pollution than in rural areas, leads to increased smoking initiation. Nevertheless, urban residents have better access to medical centers and educational resources compared to those in rural areas. This access allows individuals to become more aware of the dangers of smoking and to control their smoking levels, even if they do not quit entirely.

This study demonstrated that screening in large hospitals is more likely to encourage non-smokers to start smoking rather than aiding current smokers in quitting. However, screening in large hospitals can also promote a reduction in smoking dosage. Large hospitals or medical centers are hubs of numerous health experts, and their advice is crucial in influencing individuals to modify their behavior and pay more attention to their health [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. While complete smoking cessation may not be achieved, the influence of these healthcare professionals can significantly reduce the daily smoking dosage.

4.2. Betel Quid Chewing

This study provides evidence that individuals diagnosed with OPMD are more inclined to initiate the behavior of chewing betel quid rather than discontinue it if they are already users. Moreover, the diagnosis also tends to enhance their everyday consumption. Prior studies have established a correlation between betel quid consumption and the likelihood of developing OPMD. Nevertheless, there was a lack of research on the impact of an OPMD diagnosis on betel quid chewing behavior.

According to this study, men who have never chewed betel quid are more inclined to start doing so rather than stop if they are already using it. Additionally, males tend to increase their daily consumption of betel quid. Previous research has shown that both males and females influence the progression of betel quid use. The study provided the adjusted Hazard Rate Ratio (aHRR) and 95% Confidence Interval (95%CI) for women in Malaysia as aHRR (95%CI) 5 (4.2–6) and for males in Taiwan as 1.38 (1.2-1.59) [

24]. The study reported the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for women in Bangladesh [

25] as aOR (95% CI) of 63.54 (43.02–96.82), and for males in Taiwan as 1.14 (1.01–1.3) [

26]. The evidence suggests that both males and females can contribute to the progress of betel quid chewing, with varying impacts according to the geographical region.

This study reveals that persons below the age of 60 are more likely to initiate betel quid consumption than discontinue it if they are already users. Moreover, the diagnosis leads to an increase in their daily chewing frequency. Taiwan conducted a study that revealed a lower likelihood of older adults joining the betel quid chewing group compared to younger individuals. The study reported an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 0.84 (with a 95% confidence interval (95%CI) of 0.72-0.97) [

26]. Nevertheless, in Malaysia, as individuals aged older, their chances of quitting betel quid chewing declined. The adjusted Hazard Rate Ratio (aHRR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) support this, with values of 0.18 (0.05–0.63) for individuals aged 41–50 years and 0.11 (0.03-0.38) for those aged 51 years and above [

24]. An adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 63.54 (95% confidence interval: 43.02–96.82) from a study in Bangladesh showed that older people significantly influenced the prevalence of betel quid usage [

25]. Differences in health awareness and adherence to traditional practices can explain the variability in health outcomes across regions.

This study reveals that those with higher levels of education demonstrate an enhancement in their betel quid chewing behaviors, such as the cessation or reduction of the amount consumed. Existing research provided evidence that higher levels of education were associated with improved betel quid chewing behaviors. We observed in Bangladesh that individuals with a high level of education significantly prevent betel quid usage, with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 0.17 and a 95% confidence interval (95%CI) ranging from 0.15 to 0.2 [

25]. In Taiwan, individuals with lower levels of education were less likely to attempt quitting betel quid, with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 0.58 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.34-0.98) [

27]. They also had a higher prevalence of betel quid chewing, with an aOR of 2.02 (95% CI: 1.75-2.34) [

26]. Furthermore, individuals with a junior high school education had an adjusted hazard rate ratio (aHRR) of 2.33 (95% CI: 1.83-2.97), while those with a senior high school education had an aHRR of 2.51 (95% CI: 1.99-3.17) compared to college and above [

28]. Increased levels of education can help to improve comprehension of the hazards associated with chewing betel quid.

This study observes that individuals living in urban areas have positive changes in their betel quid chewing behaviors, such as stopping or reducing the amount consumed. A Bangladeshi study found that living in cities was linked to a lower likelihood of using betel quid. The study's adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was 0.58, and its 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was 0.54 to 0.62 [

25]. Urban areas exhibit dynamic trends, making it easier to replace traditional betel quid chewing practices than in other areas.

This study discovers that implementing screening programs in large hospitals has a substantial positive impact on betel quid chewing behaviors, specifically in motivating individuals to quit, when compared to screening programs in small hospitals. Hospitals or large medical centers are centers of specialized health specialists, which means that the advice and knowledge from these sources are highly reputable and have a greater chance of effectively influencing people's actions [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

4.3. Limitation

The study focused on a specific group of individuals who had participated in the screening program on at least two occasions. Therefore, it is not appropriate to extrapolate the findings of this study to those who only took part in the project once.

5. Conclusions

Participation in the Oral Cancer Screening program contributes to enhancing smoking and betel quid chewing behaviors. While the rates of smoking cessation are below 10% for both low and high-dose smokers, the high-dose group shows a significant drop of over 20% in daily smoking, which is worth mentioning. Furthermore, participation in this program benefited betel quid chewing behavior, as the low-dose group achieved a cessation rate of over 20% and the high-dose group achieved a reduction in dosage of over 20%. Furthermore, those with greater levels of education, residing in urban areas, and receiving screening at large hospitals contribute to the enhancement of oral risk behaviors. For better oral health and to reduce the risk of oral cancer, encouraging the public to reduce risky oral behaviors is essential. Participating in oral cancer screening programs is one way to help people monitor their oral health and enhance their knowledge and understanding of proper oral care practices. Special emphasis can be placed on targeting groups residing in rural or suburban areas with education levels below the high school degree.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Associated factors of smoking behavior transformations [aRR(95%CI)]; Table S2: Associated factors of betel quid chewing behavior transformations [aRR(95%CI)]; Table S3: Associated factors of only smoking behavior transformations [aRR(95%CI)].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y.; methodology, A.Y. and S.C.; software, P.M.; validation A.Y.; formal analysis, P.M.; investigation, A.Y.; resources, A.Y.; data curation, A.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M.; writing—review and editing, A.Y.; visualization, S.C.; supervision, A.Y. and S.C.; project administration, A.Y. and S.C.; funding acquisition, A.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare (A1111113) of the Taiwanese government and the National Science and Technology Council grant (113-2314-B-038 -085 -MY3). The funding source had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, report writing or the decision to submit this paper for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research ethics committee of National Taiwan University Hospital approved this project and granted a waiver for informed consent (202302142W) pursuant to the regulations of the institutional review board. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Health Promotion Administration of Taiwanese government. The approvement follows the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent according to the Ethics Committee regulations.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OPMDs |

Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders |

References

- World Cancer Research Fund International. Mouth and oral cancer statistics [Internet]. World Cancer Research Fund International. 2022. Available from: https://www.wcrf.

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaranarayanan, R.; Ramadas, K.; Thara, S.; Muwonge, R.; Thomas, G.; Anju, G.; Mathew, B. Long term effect of visual screening on oral cancer incidence and mortality in a randomized trial in Kerala, India. Oral Oncol. 2013, 49, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaraman, P.; O Anderson, B.; Basu, P.; Belinson, J.L.; Cruz, A.D.; Dhillon, P.K.; Gupta, P.; Jawahar, T.S.; Joshi, N.; Kailash, U.; et al. Recommendations for screening and early detection of common cancers in India. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e352–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang SL, Su WWY, Chen SLS, Yen AMF, Wang CP, Fann JCY, et al. Population-based screening program for reducing oral cancer mortality in 2,334,299 Taiwanese cigarette smokers and/or betel quid chewers. Cancer. 2017;123(9):1597–1609.

- Anwar, N.; Pervez, S.; Chundriger, Q.; Awan, S.; Moatter, T.; Ali, T.S. Oral cancer: Clinicopathological features and associated risk factors in a high risk population presenting to a major tertiary care center in Pakistan. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0236359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose M, Rajagopal V, Thankam FG. Chapter 9 - Oral tissue regeneration: Current status and future perspectives. In: Sharma CPBT-RO, editor. Academic Press; 2021. p. 169–187. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128210857000099.

- Xiao X, Wang Z. Oral Cancer. In: Zhou X, Zhang Z, editors. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2021. p. Ch. 1. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Debta, P.; Dixit, A. Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders: Etiology, Pathogenesis, and Transformation Into Oral Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 825266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, A.; Mahmood, M.; Montilla, H.; Enciso, R.; Han, P.P.; Suarez-Durall, P. Oral potentially malignant disorders in older adults: A review. Dent. Rev. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya, S. Oral potentially malignant disorders: A comprehensive review on clinical aspects and management. 2020, 102, 104550. [CrossRef]

- Eum, Y.H.; Kim, H.J.; Bak, S.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, J.; Park, S.H.; Hwang, S.E.; Oh, B. Factors related to the success of smoking cessation: A retrospective cohort study in Korea. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2022, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagan, P.; Augustson, E.; Backinger, C.L.; O’connell, M.E.; Vollinger, R.E.; Kaufman, A.; Gibson, J.T. Quit Attempts and Intention to Quit Cigarette Smoking Among Young Adults in the United States. Am. J. Public Heal. 2007, 97, 1412–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, G.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Q.; Yong, H.-H.; Elton-Marshall, T.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Sansone, N.; Fong, G.T. Individual-level factors associated with intentions to quit smoking among adult smokers in six cities of China: findings from the ITC China Survey. Tob. Control. 2010, 19, i6–i11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeom, H.; Lim, H.-S.; Min, J.; Lee, S.; Park, Y.-H. Factors Affecting Smoking Cessation Success of Heavy Smokers Registered in the Intensive Care Smoking Cessation Camp (Data from the National Tobacco Control Center). Osong Public Heal. Res. Perspect. 2018, 9, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, M.; Malik, M.I.; Ullah, A.; Junaid, N. Smoking Dynamics: Factors Supplementing Tobacco Smoking in Pakistan. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 5367–5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, L.F.; Buitrago, D.; Preciado, N.; Sanchez, G.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Lancaster, T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD000165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlebach, S.; Hamilton, S. Understanding the nurse’s role in smoking cessation. Br. J. Nurs. 2009, 18, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice VH, Hartmann-Boyce J, Stead LF. Nursing interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2013 Aug;(8):CD001188.

- Luh, D.-L.; Chen, S.L.-S.; Yen, A.M.-F.; Chiu, S.Y.-H.; Fann, C.-Y.; Chen, H.-H. Effectiveness of advice from physician and nurse on smoking cessation stage in Taiwanese male smokers attending a community-based integrated screening program. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2016, 14, 15–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammemägi, M.C.; Berg, C.D.; Riley, T.L.; Cunningham, C.R.; Taylor, K.L. Impact of Lung Cancer Screening Results on Smoking Cessation. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siewchaisakul, P.; Luh, D.-L.; Chiu, S.Y.H.; Yen, A.M.F.; Chen, C.-D.; Chen, H.-H. Smoking cessation advice from healthcare professionals helps those in the contemplation and preparation stage: An application with transtheoretical model underpinning in a community-based program. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020, 18, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghani, W.M.; A Razak, I.; Yang, Y.-H.; A Talib, N.; Ikeda, N.; Axell, T.; Gupta, P.C.; Handa, Y.; Abdullah, N.; Zain, R.B. Factors affecting commencement and cessation of betel quid chewing behaviour in Malaysian adults. BMC Public Heal. 2011, 11, 82–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flora MS, Mascie-Taylor N, Rahman M. Betel quid chewing and its risk factors in Bangladeshi adults. 2012.

- Lin, C.-F.; Wang, J.-D.; Chen, P.-H.; Chang, S.-J.; Yang, Y.-H.; Ko, Y.-C. Predictors of betel quid chewing behavior and cessation patterns in Taiwan aborigines. BMC Public Heal. 2006, 6, 271–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.; Shieh, T.; Yang, Y.C.; Chong, M.; Hung, H.; Tsai, C. Factors associated with quitting areca (betel) quid chewing. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiology 2006, 34, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, S.-F.; Ho, P.-S.; Kuo, H.-C.; Yang, Y.-H. Comparing factors affecting commencement and cessation of betel quid chewing behavior in Taiwanese adults. BMC Public Heal. 2008, 8, 199–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).