1. Introduction

Root coverage techniques have been developed to treat gingival recession, which occurs for various reasons [

1]. Various treatment techniques have been developed to achieve predictive and esthetic root coverage, such as free gingival grafts, coronally advanced flaps, laterally positioned flaps, and guided tissue regeneration [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Among these treatment techniques, the combination of a subepithelial connective tissue graft and a coronally advanced flap is currently considered the most predictable and ‘gold standard’ root coverage technique [

6].

A previous study on the mean root coverage by tooth type reported that the mean root coverage (95.7%) of the mandibular anterior region was lower than that of other regions (97.1–100%) [

7]. Among them, the unique anatomy of mandibular anterior teeth may be related to the lower mean root coverage. These include thin phenotype, minimal vestibular depth, crowding of teeth, high frenum attachment, and mentalis muscle activity. Owing to these factors, root coverage is complicated and recurrence is high [

8].

Allen introduced a method of root coverage at the recipient site formed through tunneling without a coronally advanced flap [

9]. However, the exposed portion of the graft results in a higher risk of necrosis, which reduces the predictability of root coverage. Stimmelmayr et al. induced root coverage using partially de-epithelialized connective tissue (PE-CTG) so that the exposed root surface could be covered by the epithelial portion [

10]. This technique does not advance the flap coronally, so there is no displacement of the mucogingival junction or flattening of the vestibule. Additionally, it reduces the risk of connective tissue necrosis.

Stimmelmayr et al.’s method was to harvest connective tissue except for the designed epithelial portion with a blade using the one-incision technique [

10]. This harvesting method thins the epithelium, increasing the possibility of necrosis of the donor site. Therefore, in a previous study, several authors introduced a technique to harvest grafts in the form of free gingival grafts (FGGs) after de-epithelialization of the intraoral area using a high-speed handpiece diamond round bur [

11,

12,

13].

Stimmelmayr et al. and Lim et al. used the gingival sulcus to create a tunnel for sulcular access to form the recipient site. However, this approach may traumatize the anterior gingival sulcus of the mandible and increase the risk of perforation. Therefore, in this study, we prepared a recipient site with vestibular incision subperiosteal tunnel access (VISTA), as introduced by Zadeh [

14]. This technique reduces the risk of perforation by tunneling the recipient site through a vertical incision in the vestibule, thereby enabling predictive root coverage.

Currently, there are few simple and predictable root coverage surgeries for the lower anterior teeth. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to retrospectively compare and evaluate two types of PE-CTG using a high-speed handpiece bur with introducing a graft via tunneling sulcular access (tPECTG) and a vestibular incision with subperiosteal tunnel access (vPECTG).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

Among the healthy patients who visited the periodontal department of Chosun University Dental Hospital between January 2016 and March 2024, we selected those who underwent root coverage of the lower anterior teeth using the PE-CTG, with all surgical procedures performed by a single skilled periodontologist (W.-P.L.), and had electronic medical records and clinical pictures taken 6 months after surgery. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Chosun University Dental Hospital (CUDHIRB-2403-007). All treatment plans and procedures were explained, and a consent form for surgery was completed.

2.2. Surgical Procedure

All patients underwent clinical and radiological examinations before surgery. Gingival recession depth and keratinized tissue width (KT) were evaluated at baseline and at the 6-month follow-up. Vertical recession (Rec) was defined as the deepest point of gingival recession.

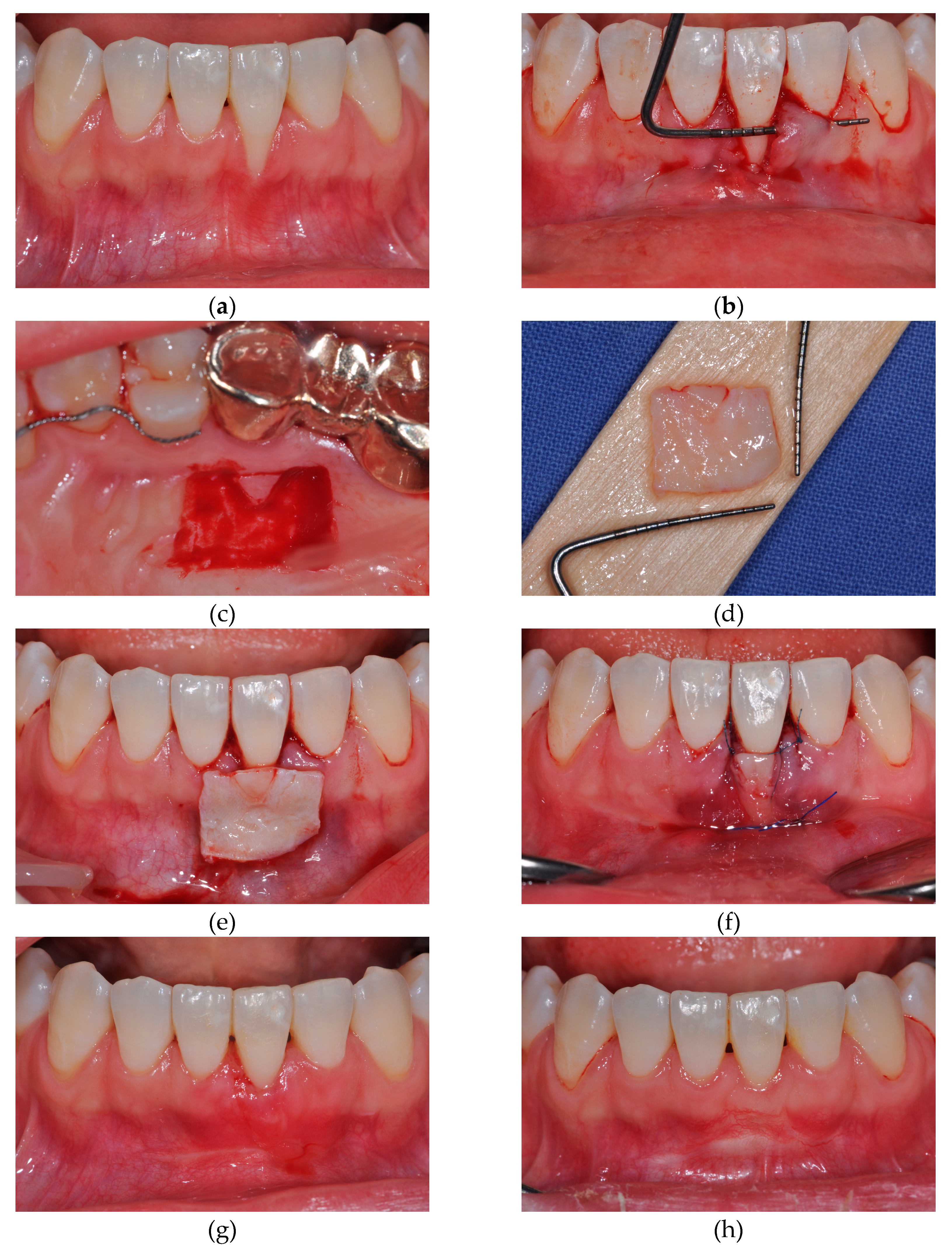

2.2.1. tPECTG

In the tPECTG group, the procedure was performed as previously described [

11]. Gargling was performed for 1 min using a 0.12% chlorhexidine solution before surgery. After local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine containing epinephrine (1:100,000) (Yuhan, Seoul, Korea), all inflamed tissues were removed using a Gracey curette (LM-Dental, Parainen, Finland), and root planing was performed on the exposed root surfaces. A sulcular incision was made and extended into the adjacent teeth, creating a labial supraperiosteal tunnel. At this time, it was ensured that no trauma had occurred to the marginal gingiva. When harvesting the graft from the donor site, it was designed according to the shape and size of the gingival recession defect measured previously from the first to the second premolar area using the blade. The tissue was de-epithelialized to a depth of 1 mm using a 2-mm diamond round bur and a high-speed handpiece, excluding the part where the epithelium was to be left. Subsequently, a PE-CTG with a thickness of 2 mm was obtained using a blade [

7]. The PE-CTG was introduced into the tunnel. The epithelial portion of the graft was then positioned on the exposed root. Suturing and fixation was performed using a non-resorbable monofilament (Rexlon 5–0; Metavision, Seoul, Korea). After suturing, gentle compression was applied to the surgical site for 5 min using wet gauze. The patients were instructed to rinse with 0.12% chlorohexidine twice daily for 2 weeks and avoid mechanical home care at the surgical site for 6 weeks. The sutures were removed 2 weeks after surgery and follow-up was performed subsequently (

Figure 1).

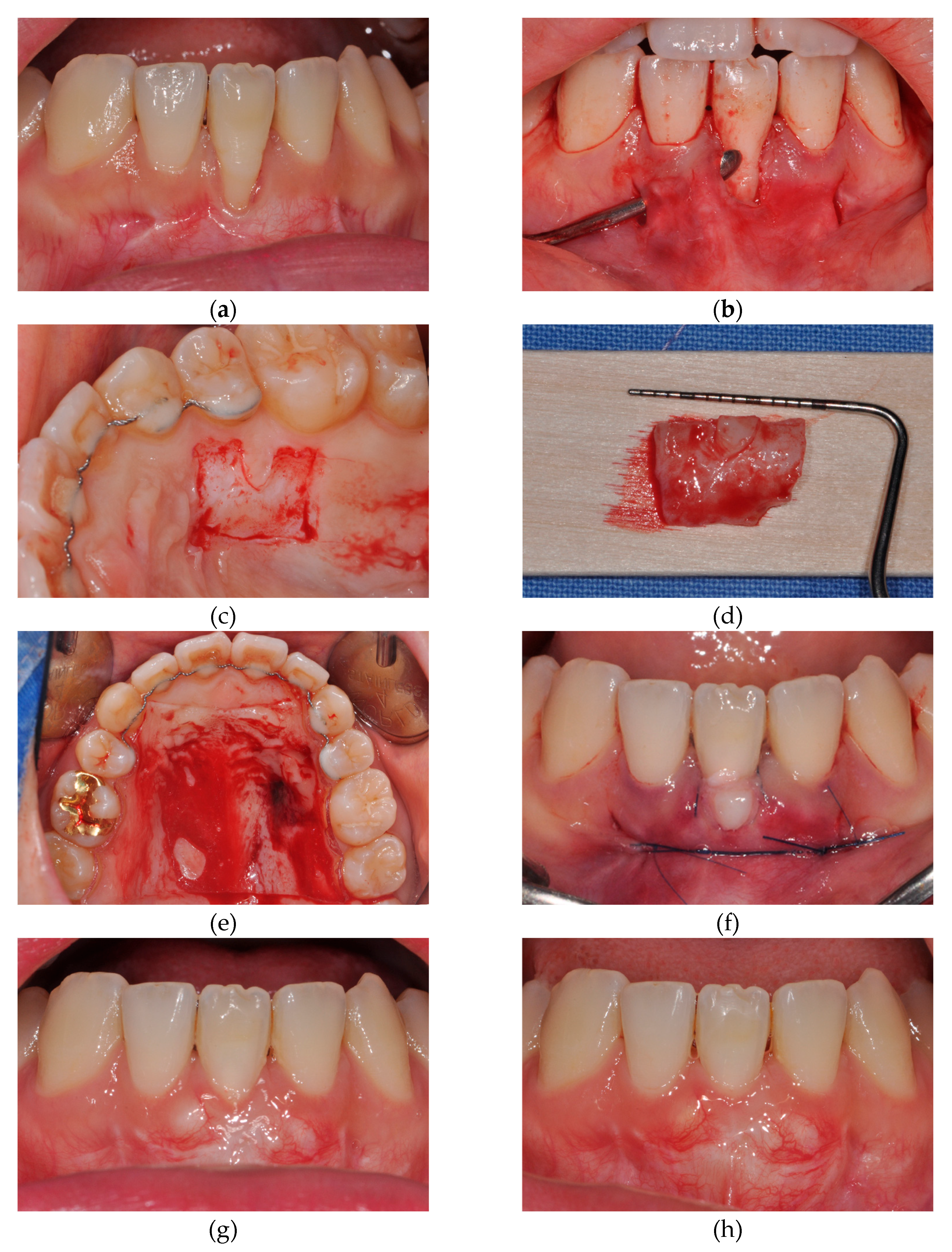

2.2.2. vPECTG

In the vPECTG group, the procedure for harvesting of the donor site was performed in the same way as described above. To form the recipient site, the VISTA method proposed by Zadeh was used to sufficiently tunnel through the subperiosteum [

14]. Thereafter, the PE-CTG was placed with the epithelium remaining in the graft placed on the exposed root. It was secured with a sling-suture technique using a non-resorbable monofilament, and a single interrupted suture was made in the vertical incision. The postoperative procedures and patient education were performed in the same manner (

Figure 2).

2.3. Results Analysis

2.3.1. Clinical Evaluation

After root coverage was performed on 20 teeth in 18 patients, the percentage of root coverage was evaluated based on Rec and KT values before and 6 months after surgery.

2.3.2. Statistical Analysis

Each quantitative variable was expressed as an average and standard deviation. The data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to test for significance among groups. The significance level was set at P< 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 22.0; IBM, Armonk, NY).

3. Results

Eighteen patients (20 teeth; 5 men, 13 women) were selected, and their ages ranged from 18–63 years (mean, 31.8 ± 13.9 years). Cases 1–8 underwent tPECTG, and Cases 9–20 underwent vPECTG. All cases were diagnosed with Miller class III recession and Cairo type 2 recession. Two patients had two adjacent sites treated, rather than one single tooth.

The clinical parameters evaluated are summarized in

Table 1, and the comparative clinical results of tPECTG and vPECTG are summarized in

Table 2. The Rec change was measured between baseline and 6 months after surgery. A total of 18 patients (20 teeth) have been treated with two different root coverage techniques, with an overall mean root coverage of 89.01%. The Rec change was 3.95 ± 1.32 mm, and the gain in KT was 3.48 ± 1.37 mm. In the tPECTG group, the Rec change was 4.25 ± 1.49 mm while in the vPECTG group, it was 3.75 ± 1.22 mm, with no significant difference between groups (P>0.05). The change in KT was measured between baseline and 6 months after surgery. The KT change was 3.9 ± 1.74 mm in the tPECTG group and 3.17 ± 1.03 mm in the vPECTG group, with no significant differences between groups (P>0.05). The mean root coverage was 87.85% in the tPECTG group and 89.78% in the vPECTG group, with no significant differences between groups (P>0.05). Complete root coverage was achieved in four out of eight cases (50%) in the tPECTG group and in seven out of twelve cases (58%) in the vPECTG group.

4. Discussion

This study retrospectively evaluated two novel root coverages on the lower anterior teeth. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the results of a comparison of tPECTG and vPECTG. Moreover, we focused on the clinical and patient benefits of vPECTG, which we recommend for root coverage on the lower anterior region. At 6 months’ follow-up, the vPECTG group showed similar results to the tPECTG group.

The mean root coverage was 87.9% and 89.8% in the tPECTG and vPECTG groups, respectively even though all cases were diagnosed with Miller class III recession. Esteibar et al. reported a mean root coverage of 74.4% in Miller class III recession with subepithelial connective tissue grafts introduced by Langer and Langer and Holbrook and Ochsenbein reported a mean root coverage of 80% with FGGs [

15,

16,

17]. In Miller class III recession, tPECTG and vPECTG showed higher mean root coverage than the other techniques. Therefore, PE-CTG showed more predictable results than other root coverage procedures for Miller class III and Cairo type 2 recessions.

A well-known benefit of root coverage with connective tissue grafts is an increase in the keratinized gingiva. Han et al. reported that leaving 1–2 mm of the uncovered graft resulted in a greater increase in KT and prevention of displacement of the mucogingival junction [

18]. However, when only the connective tissue was exposed, as the amount of graft exposed increased, necrosis of the graft occurred, making complete root coverage difficult. According to Stimmelmayr et al. and Lim et al., when the epithelium is partially left in the connective tissue graft, only the epithelial portion is sloughed off and vascularization occurs in the connective tissue below [

10,

11]. Consequently, a predictable root coverage was possible.

However, using the gingival sulcus with a tunneling sulcular access to form the recipient site may traumatize the mandibular anterior gingival sulcus and increase the risk of perforation. In the group of vPECTG, we prepared the recipient site with the VISTA method, as described by Zadeh [

14]. This technique reduces the risk of trauma and perforation. In addition, because no horizontal incision is made, scar tissue is not formed, and interruption of the blood flow supply can be minimized.

Several studies have reported that primary postoperative pain at the donor site is caused by epithelial sloughing during healing [

19,

20,

21]. According to Zucchelli et al., there was no significant difference in the dose of analgesics between the trap-door and FGG harvesting approaches, but a high dose of analgesics was noted when epithelial sloughing occurred in the trap-door approach [

22]. In addition, Harris reported that the graft obtained in the FGG approach was collagen-rich and had little fat tissue [

23]. Therefore, partial de-epithelialization with a high-speed handpiece and then harvesting in the form of FGGs, as Lim et al. suggested, can obtain collagen-rich connective tissue with low postoperative pain [

11].

According to Yotnuengnit et al., the outcome of root coverage is related to the ratio of graft tissue area (GTA) to the visible denuded area (VDA) [

24]. They showed that this ratio should be at least 11:1 to achieve complete root coverage. In the tPECTG group, complete root coverage was achieved in four of eight cases; the GTA:VDA ratios in patients who achieved complete root coverage were 7.7:1, 10.1:1, 12.4:1, and 7.8:1, respectively, and were in the range of 7.7:1 to 12.4:1. In the vPECTG group, complete root coverage was achieved in seven of 12 cases; the GTA:VDA ratios in patients who achieved complete root coverage were 8:1, 9.4:1, 8.9:1, 9:1, 5.4:1, 8.4:1, and 8.5:1, respectively, and were in the range of 5.4:1 to 9.4:1. In this study, complete root coverage was possible with PE-CTG, which had smaller ratios than those suggested by Yotnuengnit et al.. Therefore, higher mean root coverage is possible with smaller connective tissue grafts, and the patient’s modality will also decrease.

The original technique of a coronally advanced flap combined with a subepithelial connective tissue graft involved the elevation of a partial-thickness flap at the recipient site into the supraperiosteal region to enhance revascularization of the graft. However, the partial-thickness flap requires more skill than the full-thickness flap, especially in mandibular anterior teeth with a thin phenotype. Mazzocco et al. performed a coronally advanced flap combined with a subepithelial connective tissue graft using full- or partial-thickness flaps and reported that there was no significant difference between the two [

25]. These results are consistent with this study. There were no significant differences in the Rec change, KT change, or percentage of root coverage between tPECTG, which involves partial-thickness flap elevation, and vPECTG, which involves full-thickness flap elevation. Therefore, vPECTG is considered predictive of root coverage in thin phenotypes, such as the mandibular anterior region.

This study was retrospective in nature and has some limitations. No controls were included in this study to assess conditions that could affect the results of root coverage, such as patient age, tooth malposition, and systemic conditions (smoking and periodontitis). In addition, to compare the effects of the two different root coverage techniques, the timeframe was limited to 6 months to exclude the effect of creeping attachment according to the difference in the follow-up period. Therefore, the follow-up period in all cases was relatively short, and long-term follow-up is required. In addition, since the number of subjects in each group was relatively small and the follow-ups for all cases were short-term, analyses of the mid- and long-term results are recommended, and a prospective clinical study with a robust design and more samples is needed.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, we concluded that vPECTG was as effective as tPECTG in partially de-epithelialized connective tissue grafts using a high-speed handpiece. In particular, vPECTG is easier and can be performed in thin phenotypes, such as those in the mandibular anterior region. In both groups, KT increased and the mucogingival junction remained unchanged. This is thought to be a valuable treatment for gingival recession of the anterior mandibular teeth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.-P.L.; methodology, W.-P.L.; software, M.-Y.G.; validation, M.-Y.G., S.-K.L., and K.-M.K.; formal analysis, M.-Y.G.; investigation, S.-K.L.; resources, W.-P.L; data curation, M.-Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.-Y.G.; writing—review and editing, W.-P.L; visualization, M.-Y.G.; supervision, W.-P.L.; project administration, W.-P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Dental Hospital of Chosun University in Gwangju, South Korea (CUDHIRB-2403-007).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dong-Su Lee (Professor, Department of Computer Science and Statistics, Chosun University, Gwangju, Republic of Korea) for statistical consulting and some of the data analysis. This study was supported by a research fund from the Chosun University, 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zucchelli G., Mounssif I. Periodontal plastic surgery. Periodontol 2000. 2015;68(1):333-68. [CrossRef]

- Nabers J.M. Free gingival graft. Periodontics. 1966;4:243-5.

- Harvey P.M. Surgical reconstruction of the gingiva. II. Procedures. N Z Dent J. 1970;66(303):42-52.

- Grupe H.E., Warren R.F., Jr. Repair of gingival defects by a sliding flap operation. J Periodontol. 1956;27(2):92-5. [CrossRef]

- Prato G.P., Tinti C., Vincenzi G., Magnani C., Cortellini P., Clauser C. Guided tissue regeneration versus mucogingival surgery in the treatment of human buccal gingival recession. J Periodontol. 1992;63(11):919-28. [CrossRef]

- Chambrone L., Botelho J., Machado V., Mascarenhas P., Mendes J.J., Avila-Ortiz G. Does the subepithelial connective tissue graft in conjunction with a coronally advanced flap remain as the gold standard therapy for the treatment of single gingival recession defects? A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2022;93(9):1336-52. [CrossRef]

- Harris R.J. The connective tissue with partial thickness double pedicle graft: The results of 100 consecutively-treated defects. J Periodontol. 1994;65(5):448-61. [CrossRef]

- Harris R.J., Miller L.H., Harris C.R., Miller R.J. A comparison of three techniques to obtain root coverage on mandibular incisors. J Periodontol. 2005;76(10):1758-67. [CrossRef]

- Allen A.L. Use of the supraperiosteal envelope in soft tissue grafting for root coverage. I. Rationale and technique. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1994;14(3).

- Stimmelmayr M., Allen E.P., Gernet W., Edelhoff D., Beuer F., Schlee M., et al. Treatment of Gingival Recession in the Anterior Mandible Using the Tunnel Technique and a Combination Epithelialized-Subepithelial Connective Tissue Graft--A Case Series. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2011;31(2).

- Lim K.O., Kim B.O., Lee W.P. Technical Note on Root Coverage of Lower Anterior Teeth Using a Partially Deepithelialized Connective Tissue Graft (PE-CTG) Aided by a High-Speed Handpiece. Case Rep Dent. 2020;2020. [CrossRef]

- Bakhishov H., Isler S.C., Bozyel B., Yıldırım B., Tekindal M.A., Ozdemir B. De-epithelialized gingival graft versus subepithelial connective tissue graft in the treatment of multiple adjacent gingival recessions using the tunnel technique: 1-year results of a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2021;48(7):970-83. [CrossRef]

- Zazou N., El Nahass H., Ezz El-Arab A. A technical modified method for harvesting palatal de-epithelialized connective tissue graft for root coverage: a case report. Advanced Dental Journal. 2019;1(3):72-6. [CrossRef]

- Zadeh H.H. Minimally invasive treatment of maxillary anterior gingival recession defects by vestibular incision subperiosteal tunnel access and platelet-derived growth factor BB. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2011;31(6):653.

- Esteibar J., Zorzano L., Cundín E.E., Blanco J., Medina J. Complete root coverage of Miller Class III recessions. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2011;31(4):e1-e7.

- Langer B., Langer L. Subepithelial connective tissue graft technique for root coverage. J Periodontol. 1985;56(12):715-20. [CrossRef]

- Holbrook T., Ochsenbein C. Complete coverage of the denuded root surface with a one-stage gingival graft. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1983;3(3):8-27.

- Han J.S., John V., Blanchard S.B., Kowolik M.J., Eckert G.J. Changes in gingival dimensions following connective tissue grafts for root coverage: comparison of two procedures. J Periodontol. 2008;79(8):1346-54. [CrossRef]

- Edel A. Clinical evaluation of free connective tissue grafts used to increase the width of keratinised gingiva. J Clin Periodontol. 1974;1(4):185-96. [CrossRef]

- Jahnke P.V., Sandifer J.B., Gher M.E., Gray J.L., Richardson A.C. Thick free gingival and connective tissue autografts for root coverage. J Periodontol. 1993;64(4):315-22. [CrossRef]

- Harris R.J. A comparison of two techniques for obtaining a connective tissue graft from the palate. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1997;17(3):261-71.

- Zucchelli G., Mele M., Stefanini M., Mazzotti C., Marzadori M., Montebugnoli L., et al. Patient morbidity and root coverage outcome after subepithelial connective tissue and de-epithelialized grafts: a comparative randomized-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37(8):728-38. [CrossRef]

- Harris R.J. Histologic evaluation of connective tissue grafts in humans. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2003;23(6).

- Yotnuengnit P., Promsudthi A., Teparat T., Laohapand P., Yuwaprecha W. Relative connective tissue graft size affects root coverage treatment outcome in the envelope procedure. J Periodontol. 2004;75(6):886-92. [CrossRef]

- Mazzocco F., Comuzzi L., Stefani R., Milan Y., Favero G., Stellini E. Coronally advanced flap combined with a subepithelial connective tissue graft using full-or partial-thickness flap reflection. J Periodontol. 2011;82(11):1524-9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).