1. Introduction

In Indonesia, climate change and poverty are closely linked. Climate change has the potential to cause an increase in the poverty rate. Data from March 2022 recorded 26.16 million people, or 9.54% of the total population, living below the poverty line. Meanwhile, 67% of Indonesia's population is in the vulnerable position of poverty; those who are not at the poverty line but also not in the middle class will be pushed to the poverty line if affected by climate change [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The risk of declining commodity production looms over farmers and the public as consumers in the agricultural sector. The economic losses incurred are significant. At least in 2023, the total financial loss due to climate change reached IDR 115.53 trillion, with losses in the agricultural sector reaching IDR 19.94 trillion. This loss includes 27 million household farmers, including 17 million rice farmers with average land ownership of 0.6 ha [

5]. In general, household farms in Indonesia are undereducated, adopting and using inefficient technologies [

6].

Rice is an important food crop among the various crops cultivated in Indonesia. This rice crop is highly affected by climate change [

7,

8], and rice farmers carry out adaptation strategies as a location-specific global phenomenon [

9]. In the tropics, the main factors that influence farm households' decisions to adapt to climate change include [

10], lack of access to agricultural extension services [

11], access to climate information [

12,

13,

14], changes in rainfall patterns [

14,

15], and yield loss [

16,

17]. In addition, climate change is impacting tropical plants due to increased temperature stress [

18]. Many adaptation strategies at the farm level relate to planting and harvesting dates [

19], crop rotation, quality seed selection [

20,

21], selection of crops and crop varieties for cultivation, water consumption for irrigation [

22], fertilizer use, and tillage practices [

23]. These natural adaptations result from producers' goal to maximize returns to their land resources. Each adaptation can reduce potential yield losses due to climate change or increase yields where climate change can be utilized [

24,

25,

26].

Adaptation strategies related to climate change have been widely discussed by researchers with a tendency to discuss economic incentives [

26,

27], overcoming negative impacts on various crop production [

28,

29]. Examining adaptation strategies in agriculture to climate change is important to increase adaptive capacity by empowering communities and improving ecosystem functionality, especially when these diversification strategies are adopted [

30]. Various adaptation strategies to sustain crop yields in different countries that can be adopted have been demonstrated, such as in Uganda, such as fertilizer application, planting of adaptive crop varieties, and using improved irrigation methods or water collection technologies. Agronomic adaptation measures include early planting, mulching and terrace creation, contour plowing, land emptying, shifting cultivation, use of compost fertilizer, intercropping, and crop rotation. Off-farm adaptive measures include migration, loans, and taking off-farm jobs [

31] or diversifying crops from rice to cassava, oil palm, sugarcane, mango, watermelon, and vegetables, changing planting calendars and crop varieties, increasing the use of farm machinery or shifting planting locations. Farmers have formed cooperatives to implement these adaptation measures as they are not affordable to do individually [

32].

Meanwhile, the application of adaptation strategies with social farmer participation and discussing the impact of climate change on the culture and traditional knowledge of farming communities is minimal, including using different irrigation systems. This paper illustrates this by looking at the differences between rice farmers in hilly areas who use irrigation systems as a source of water for their farms (called irrigation farmers) and rice farmers who farm in the plains close to the water source of Lake Toba but do not use irrigation systems (called non-irrigation farmers). Both are in the same highland area but have different farming methods and water sources. This affects the differences in their rice farmers' awareness, behavior, and adaptation strategies to climate change from planting to harvesting rice. The awareness of rice farmers is not based on their production and economic value [

33]. However, it is also important to see how the adaptation practices of these two different communities use traditional knowledge to deal with climate change and maintain their crop yields.

2. Materials and Methods

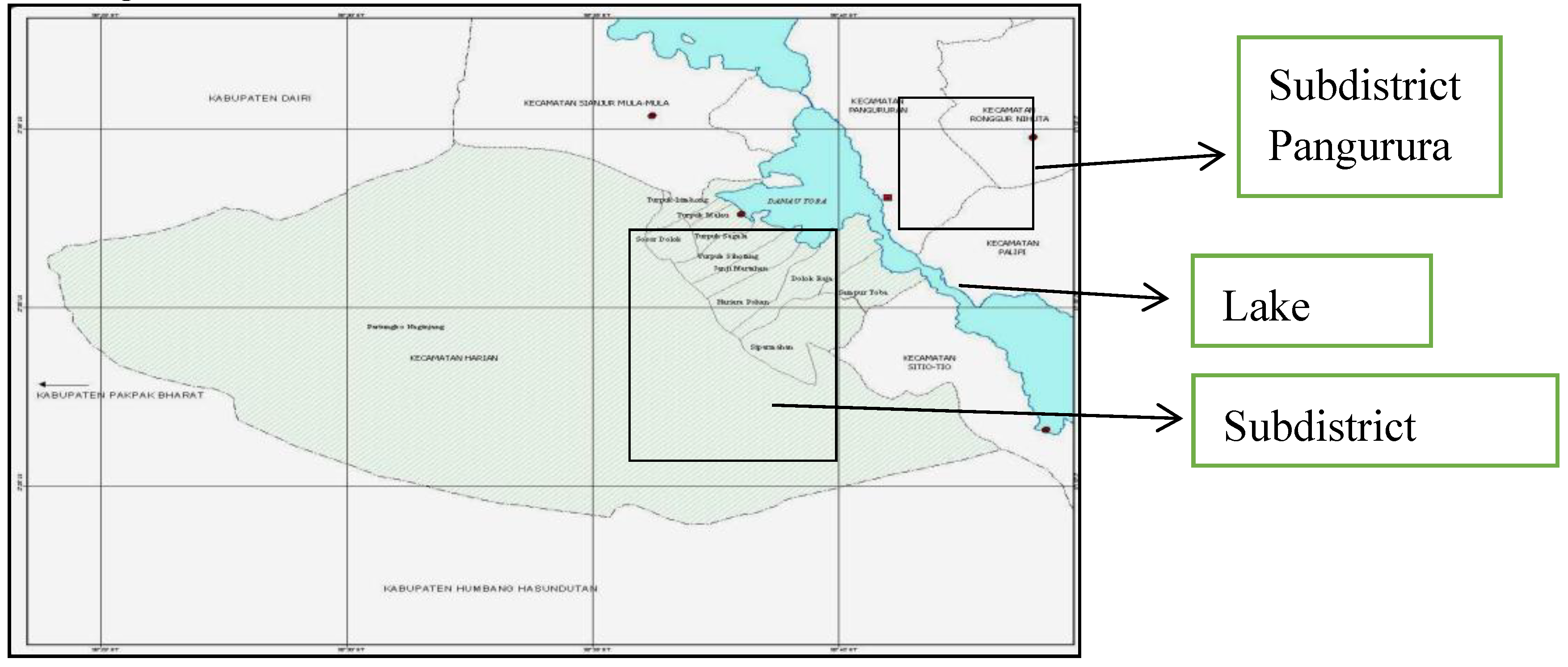

This study was conducted in Samosir Regency, North Sumatra Province, by taking two sub-district locations: Harian and Pangururan. It is located between 2021'38''- 2049'48'' North Latitude and 98024'00'' - 99001'48'' East Longitude with an altitude between 904 - 2,157 meters above sea level with an area of ± 2,069.05 km2. Geographically, the area is surrounded by towering mountains, and only a little flat land is on the coast of Lake Toba. Mostly, it is in a closed valley that leads directly to Lake Toba and Samosir Island. The position of this area, surrounded by mountains, makes it look like it is isolated from the outside world. This location is in the Lake Toba tourist area. This location area was chosen based on the different farming systems used by rice farmers, namely irrigated farming in Harian District and non-irrigated farming in Pangururan District. Farmers with non-irrigated farming systems often experience water shortages due to prolonged droughts, while farmers with irrigated farming systems often experience strong winds that damage their rice. Farmers in Harian District utilize water sources from the Efrata waterfall to irrigate their rice fields. In contrast, farmers in Panguruan District utilize lake water sources by using water pumps to irrigate their rice fields. In addition, the communities in this area are recognized as having a variety of traditional knowledge in various matters, such as in the field of health [

34,

35,

36,

37], agricultural and forest [

38].

This research method uses a descriptive qualitative approach. Data was collected through in-depth interviews and FGDs with farmer group leaders, traditional leaders, and religious leaders who also work as farmers, climatology officers, local officials, and the oldest farmers who have long been involved in rice farming. Meanwhile, interviews and questionnaires were distributed in each area by random sampling to 130 respondents. The questionnaires were distributed to rice farmers who manage their farms near Lake Toba as a water source, farmers who manage farms located in hilly areas far from water sources in the Pangururan sub-district, and farmers who manage their land in hilly areas but get water sources from waterfalls in Harian sub-district.

Map 1.

Study Area around Lake Toba.

Map 1.

Study Area around Lake Toba.

3. Results

3.1. Climate Change Awareness

Irrigated and non-irrigated rice farming communities' awareness of climate change in this area is measured based on their knowledge of: (a). occurrence of extreme situations over the last 10 years, (b). rainfall, (c). water discharge in rivers, and (d). air temperature. The extreme situation in question is a prolonged dry season: drought and frequent strong winds. This situation is believed by 43 irrigated rice farmers (66.1%) and 64 non-irrigated rice farmers (98.5%). Meanwhile, the decreasing rainfall is believed to result from 47.8% of irrigated farmers and 93.9% of non-irrigated farmers. The situation of river water discharge that continues to decline to irrigate rice fields is mentioned by 33.8% of irrigated farmers and 84.6% of non-irrigated farmers. Meanwhile, the increase in air temperature in the last 10 years has been felt by 37.0% of irrigated rice farmers and 52.3% of non-irrigated farmers.

Table 1.

Local community awareness of climate change.

Table 1.

Local community awareness of climate change.

| Statements |

Paddy Planting |

| Irrigation |

Non–Irrigation |

| Extreme situations that have been experienced |

Drought |

43 (66.1%) |

64 (98.5%) |

| Heavy Rains |

3 (4.7%) |

- |

| High winds |

15 (23.0%) |

- |

| Not experienced |

4 (6.2%) |

1 (1.5%) |

| Rainfall conditions in this area over the last 10 years |

Unchanged |

19 (29.2%) |

2 (3.1%) |

| Uncertain |

9 (13.8%) |

1(1.5%) |

| Decrease |

31(47.8%) |

61(93.9%) |

| Increase |

6 (9.2%) |

1(1.5%) |

| The state of river water discharge used for irrigation for the past 10 years |

Unchanged |

26 (40.0%) |

3 (4.7%) |

| Uncertain |

13 (20.0%) |

6 (9.2%) |

| Decrease |

22 (33.8%) |

55 (84.6%) |

| Increase |

4 (6.2%) |

1(1.5%) |

| Air temperature conditions in this area over the last 10 years |

Unchanged |

16 (24.6%) |

28 (43.0%) |

| Uncertain |

18 (27.7%) |

- |

| Decrease |

7 (10.7%) |

3 (4.7%) |

| Increase |

24 (37.0%) |

34 (52.3%) |

In general, rice farmers' views on climate change in this area are only related to (a) the occurrence of extreme rains and (b) the emergence of extreme winds. Extreme rain occurs when heavy rain comes suddenly and then suddenly gets hot again. Also, when frequent `hot rain' (locally known as “

singgar”) occurs, rain and heat co-occur. This situation has a terrible impact on the rice crop. As a result of these two weather conditions, rice farmers will experience a situation where the rice stalks have begun to turn yellow. However, the paddy seeds are empty or contain smelly caterpillars. On the other hand, extreme wind is defined by the sudden arrival of strong winds at night that break the stalks of rice or corn stalks. Usually, these extreme winds only occur during the prolonged dry season. This situation shows that irrigated rice farmers have less awareness of climate change than non-irrigated rice farmers. Climate change is interpreted when extreme events apply to their agricultural produce. In other parts of the world, as noted by Petersen-Rockney Margiana [

39], there is still a gap between scientific understanding of climate change and farmers' adoption of adaptation and mitigation practices [

40]. Many US farmers do not believe in anthropogenic climate change [

41], do not consider climate change a local risk to their farming operations [

42], and have not implemented management practices that reduce emissions or foster resilience [

43]. In addition, farmers often distrust public agricultural advisors such as Cooperative Extension staff who discuss climate change [

44].

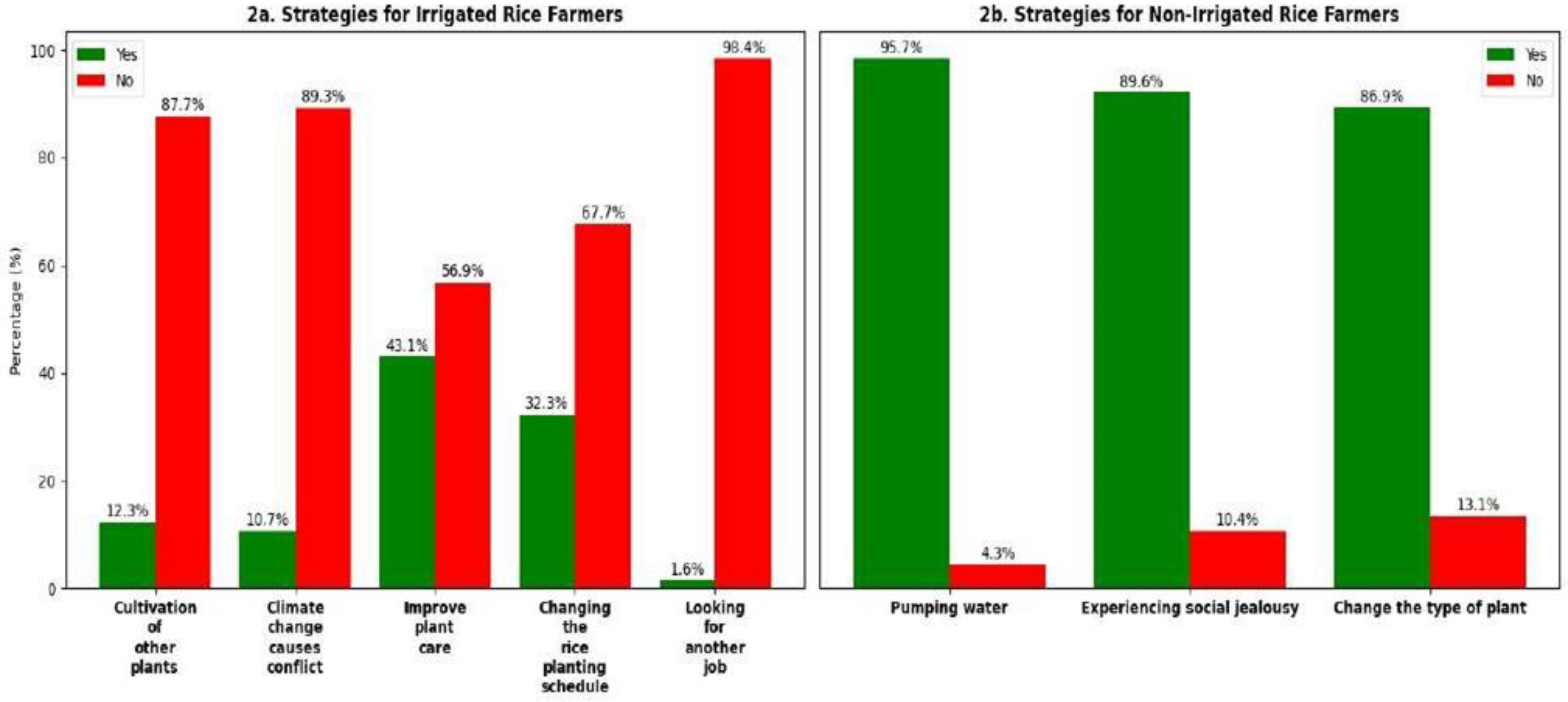

3.2. Behavior of Irrigated and Non-Irrigated Rice Farmers in Facing Climate Change

The behavior of rice farmers towards climate change is seen in (a). adaptation strategies of irrigated farmers living in mountainous areas (b). adaptation strategies of non-irrigated farmers in the lowlands, and (c). Irrigated and non-irrigated rice farmers carry out adaptation strategies based on experience dealing with climate change. Behavioral differences are seen based on differences in the location of rice planting land and irrigation facilities on their farms. However, they also have the same experience in dealing with climate change. The differences and similarities of adaptation strategies to climate change in these two types of rice farmers can be seen in the table below:

3.2.1. Adaptation Strategies of Irrigated Rice Farmers

Irrigated rice farmers mentioned that they fully depend on rice farming for their livelihoods and economic activities, making it difficult to change the type of crop with other crops. For the Toba Batak people, rice has its own cultural value, not only as the main food but also as a source of family honor [

45,

46].

Chart 1.

Rice Farmers' Behavior in Facing Climate Change Source: Authors’ work, 2024.

Chart 1.

Rice Farmers' Behavior in Facing Climate Change Source: Authors’ work, 2024.

Table 2a shows that only 12.3% of irrigated rice farmers want to change their rice crop with other crops that are more economically valuable when the dry season is prolonged. Farmers who change the crop type reasoned that changing the rice crop with other crops will improve and increase soil fertility and will return to planting rice when the rainy season arrives. This will also impact the quality of rice that will be planted in the following season [

47,

48]. Another reason is that diversifying crops can reduce the impact of economic losses on farmers. Several cases were found where people with sizeable agricultural land diversify crops by planting rice and other food crops such as corn. Maize is one of the food crops resistant to weather changes in this area. This aims to reduce the enormous losses incurred when extreme weather changes occur. When rice crops experience crop failure, farmers will not get a significant loss because they have corn or other crops as alternative crops [

49,

50].

Conflicts over water sources occurred during the prolonged dry season, as mentioned by 10.7% of irrigated rice farmers. Irrigation is used as the artificial channeling or delivery of water to agricultural land to ensure the availability and supply of water throughout the year. Irrigation is an important technique farmers use to adapt to climate change [

51]. The water source for the rice area comes from the Efrata waterfall, which has a height of about 26 meters and a width of approximately 12 meters and has never experienced drought. When the extreme dry season occurred, the waterfall did not experience drought, but the discharge of the waterfall source that flowed into the rice farmers' agricultural land decreased. This is what began to cause conflict among the farmers. Farmers whose rice fields are higher in the mountains will have close access to water to the rice fields of farmers below, so rice fields on the lower slopes of the mountains will lack water, resulting in the arrival of pests. Farmers often carry out these conflicts over water at night, where farmers close the water channels to other farmers' fields and stand guard overnight until their farms get the required water flow. Increased care of rice plants is done by 43.1% of irrigated farmers when extreme climate change occurs. They fertilize, weed the rice, clear the bunds of weeds, and protect the rice from animal attacks. Increased care of rice plants is done by 43.1% of irrigated farmers when extreme climate change occurs. They fertilize, weed the rice, clear the bunds of weeds, and protect the rice from animal attacks. Disruptions that occur disrupt practices and negatively affect agricultural yields. The effectiveness of these activities can only save a fraction of the target rice harvest [

52]. Such disruptions have consequences at multiple levels, ranging from direct personal impacts on farmers and their communities to indirect levels that impact the socioeconomic structure of countries and regions. The choice to change the rice planting schedule was only made by 32.3% of irrigated rice farmers in the event of extreme climate change. The schedule change is only done by rice farmers whose paddy fields are at the foot of the mountains due to the fear of insufficient water.

Accommodating climate change by changing planting and harvesting dates is not fully applicable [

53] for irrigated farmers in this region, and rice varieties also need to be considered [

54]. Switching to other occupations for irrigated rice farmers is possible, but leaving this occupation for good is rare. Only 4.6% intend to switch jobs but will return to rice farming if extreme droughts do not occur again.

3.2.2. Adaptation Strategies of Non-Irrigated Rice Farmers

The results of the adaptation strategies of non-irrigated rice farmers are presented in

Table 2b. The results show that 95.7% of non-irrigated rice farmers conduct pumping to irrigate their farmlands. Water pumps are an alternative used by non-irrigation farmers for rice fields located close to Lake Toba. Non-irrigation farmers use pumping when the dry season arrives. Lake Toba's machine and pipe water flows directly into the farmers' agricultural land. For the use of pumps, non-irrigated rice farmers must pay a rent of Rp.30,000/hour. The length of time to use the pump to irrigate the rice field depends on the size of the field, usually taking more than 12 hours. The high cost and disproportionate yields have led them to switch jobs as farm laborers elsewhere or leave their land fallow for a season until the rainy season arrives. Climate change is the biggest challenge farmers face with non-irrigated farming systems, which the community calls

sabah langit.

However, if the farmland is located in a hilly area far from Lake Toba, they cannot use a pump, so they can only expect rainfall or rain-fed rice fields. According to the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture's 2024 records, rain-fed rice fields amount to 2.7 million hectares or 36% of the 7.5 million hectares of rice fields. Therefore, conjunctive water uses utilizing and prioritizing different water sources, viz harvested rainwater, treated wastewater, desalinized water, and groundwater, is vital in sustainable water resources management [

55]. This social jealousy occurs when the extreme dry season comes, and water starts to run low. This form of social jealousy in non-irrigated farmers is due to (1). irrigated rice farmers in mountainous areas have a water source like a waterfall that never dries; only the water discharge decreases (2). non-irrigated rice farmers on the shores of Lake Toba, it is still possible to get water for their agricultural land using water pumping. A total of 89.6% of non-irrigated farmers experience social jealousy based on differences in the geographical location of their farms.

Figure 1.

Pumping equipment and pumping rice fields.

Figure 1.

Pumping equipment and pumping rice fields.

With the occurrence of extreme climate change in this area, 86.9% of non-irrigated rice farmers made changes in crop types. They change it with short-term crops, which are crops that have a process of planting to harvest in a short period, only within 3-4 months, such as corn (

Zea mays), long beans (

Phaseolus vulgaris), and ginger (

Zingiber officinale Rosc.). After that, they return to planting rice when the rainy season arrives. In this way, some informants experienced an increase in agricultural yields, as seen from last year's harvest, which reached 150 cans, and the last harvest, which reached 200 cans. The harvest will then be sold by the informants and partly for family consumption. The above types of plants can be grown on rainfed land using multiple cropping or agroforestry systems between perennial crops [

56], improving the economy of farming families [

57].

3.3. Adaptation Strategies of Irrigated and Non-Irrigated Rice Farmers Based on Shared Experiences in Facing Climate Change

Table 3 presents the similarities between irrigated and non-irrigated rice farmers' experiences with climate change. However, these shared experiences will be further analyzed based on each rice farmer's unique habits and traditional knowledge. For instance, this includes their responses to crop failures caused by climate change. Both show a similar experience: as many as 72 respondents (55.4%) have experienced crop failure, and another 58 respondents (44.6%) have never experienced crop failure. However, there were differences in the experience of crop failure. For irrigated rice farmers, crop failure is associated with decreased productivity. They still get rice yields even though there is a decrease in harvests compared to the previous year. Meanwhile, for non-irrigated rice farmers, crop failure means not getting any harvest at all. Harvest failure in irrigated rice farmers is caused by (1). strong winds that cause rice plants to duck, or because (2). continuous rain causes excessive water volume in rice, making it difficult for rice to bear fruit. This prolonged rain then causes the emergence of pests and moldy rice, or (3). A prolonged drought occurs, and the rice plants become burned and wither. Meanwhile, for non-irrigated farmers, crop failure is always caused by a prolonged dry season. This often forces them to change their rice planting schedule and crops and even not plant rice for the year if there is no sign of rain. There is nothing non-irrigated farmers can do to fight for their rice crop when the rains do not come.

Farmers' knowledge of high-yielding and wind-resistant varieties of rice seedlings in these two areas showed that 80 respondents (61.5%) did not know of wind-resistant varieties of rice seedlings, and only 50 other respondents (38.5%) knew of wind-resistant varieties. Some of the rice types local farmers use are: (a) `siserang,` a rice seedling with a short stem. Farmers choose it because it can withstand strong winds (b). `sibandung` rice seedlings are used by farmers. After all, they are more resistant to strong winds than other seedlings and have more elastic stems that do not break easily (c). The `Sirambu Manis` rice seedling is only thigh to adult height (d). Meanwhile, `Sisiopol` rice seedlings are known by farmers to resist drought. Some farmers have used local rice seeds for generations, but some change the seeds at every planting period.

The majority of rice farmers have joined farmer groups (91.5%). The main reasons for joining a farmer group are easy access to low-priced fertilizer, good rice seeds, and the organization program. The price of fertilizer on the market is relatively high for farmers, and they have recently complained that it is challenging to obtain fertilizer. Farmer groups in the community can also not routinely distribute fertilizer to their members because it is difficult to receive it from the government regularly. When the planting season arrives, but farmers do not get fertilizer, the rice schedule that should enter the fertilization stage will be delayed. This then impacts the time the rice will turn yellow or be harvested. This farmer group has never shared information on climate change with its members (71.4%). This farmer group is a gathering place for all farmers and an information center for its members, who should provide information about the time to plant rice. They also never received information or socialization about climate change from the local government. Finally, they plant rice without relying on climate change information (87.7%). Although they are aware that there have been changes in agricultural productivity (91.9%) due to climate change, they argue that the causes of changes in agricultural production in these two areas are rising temperatures 14.3%, lack of irrigation facilities 5.7%, poor quality seeds 1.9%, lack of fertilizer because it is expensive 35.2%, lack of equipment 2.9%, pest problems 14.3%, lack of labor 6.7%, changeable weather 12.4%, long drought 6.7%. From this data, it can be seen that climate change is not the absolute cause of the decline in rice yields, but other things still cause a decrease in rice yields.

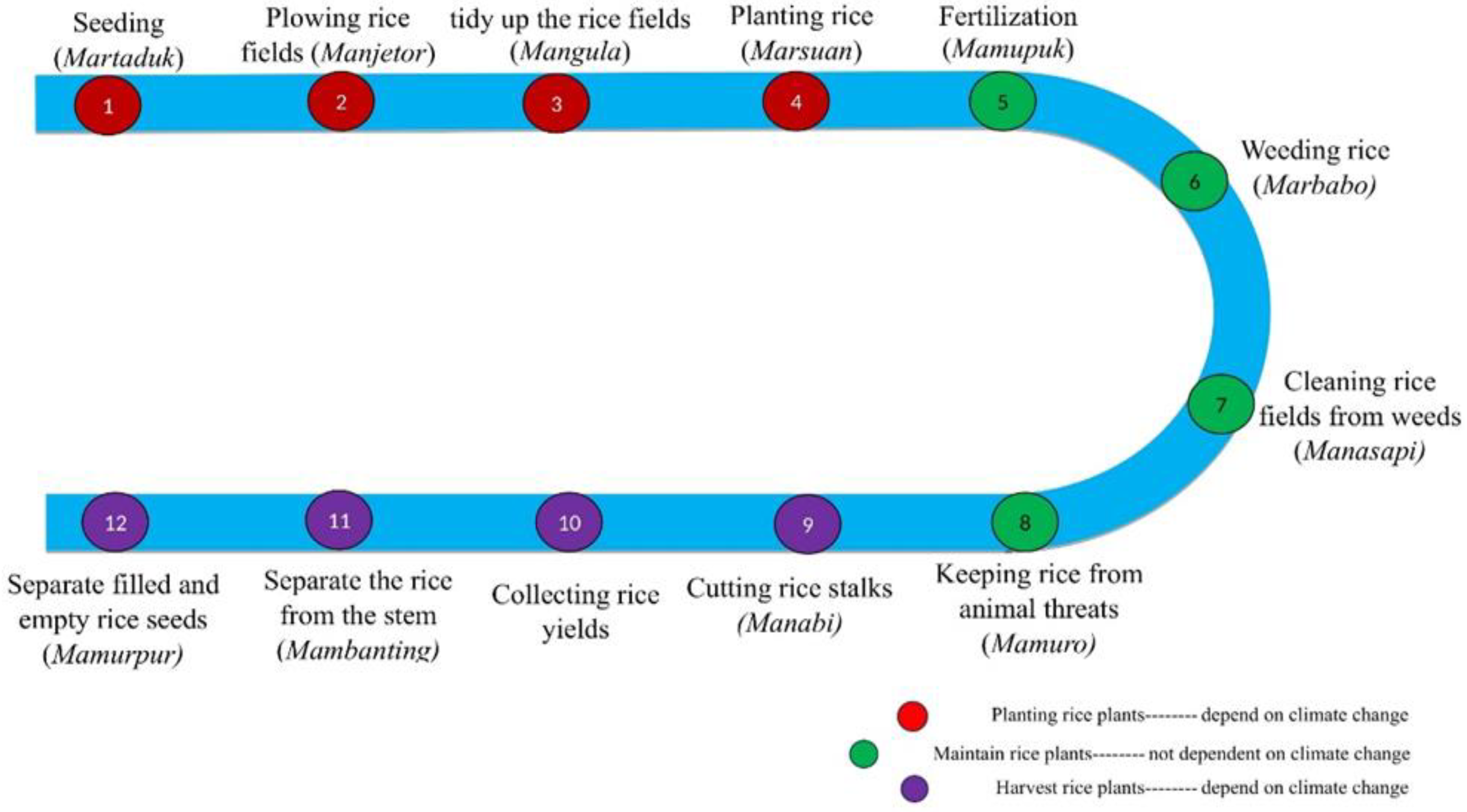

3.4. Erosion of Traditional Knowledge of Rice Farmers

Without information on climate change from the government or farmer groups, they usually use traditional knowledge based on their experience to guide their agricultural activities. However, this condition is increasingly eroded due to climate change. This process is the most weather-dependent period for planting rice plants. The rainy season is the long-awaited and most suitable time for planting rice, so the seedlings do not lack water. Rice farmers know that August to December every year is the approximate time when the rainy season will arrive. So, it is the right time for farmers to start planting. Meanwhile, January to July is the dry season. This guideline has become local knowledge for the community. In addition, some local wisdom about the rainy season will occur.

Figure 2.

Stages of Rice Cultivation and Their Dependency on Climate Change.

Figure 2.

Stages of Rice Cultivation and Their Dependency on Climate Change.

Among other things, it is characterized by the direction of the wind from Lake Toba blowing north towards the hilly area, and the wind makes a sound. In addition to seeing the direction of the wind, other signs are the appearance of many fish in the waters of Lake Toba. However, nowadays, the community has felt the occurrence of climate change, and the signs of traditional knowledge about the schedule of the rainy and dry seasons have begun to change. As many as 96.7% of informants stated that the weather is no longer as predictable as it used to be. They should have started planting rice in September, but the rains did not come until October, so they had to postpone the planting process. Climate change has meant that they only plant rice once a year, compared to previously planting rice twice a year.

Rice plant maintenance activities start from the fertilization stage (manganpui) to protect rice from pests and animals (mamuro). In this process, rice farmers are not dependent on climate change. They use traditional knowledge that has been done before climate change, for example, drying the rice fields when fertilizing so that the fertilizer is not wasted following the flow of water down and flowing water back into the fields when the fertilizer is considered to be absorbed in the soil. Other activities are carried out to protect rice from animal pests and birds, as well as clean weeds so that the rice is ready to harvest with the characteristics of seeds, leaves, and rice stems already appearing yellow. While in the agricultural activity of harvesting, when the rice starts to turn yellow and the rice seeds have ducked, traditional knowledge emerges to save the crop due to climate change. The most critical adaptation strategy carried out by rice farmers is to guard the rice (mamuro) before the harvest period arrives. The guarding that is done: (1). When heavy rains come suddenly. This rain can break the stems of rice that are ready to be harvested, especially for the type of rice with tall stems. The fallen rice stalks need to be tied up in groups. In this way, some rice stalks can stand upright again. (2). When strong winds accompany the dry season. This climate change causes drought, and rice ripens prematurely (masak sadari). Strong winds will knock the rice seeds to the ground. There is nothing that can be done except to accept fate. The solution is to harvest the rice ahead of time. The dry season with strong winds is the main enemy of farmers, especially in recent years when strong winds can come at any time. (3). Extreme rains that fall continuously every day for a long duration, such as rains that always fall for half a day, from morning to noon or from noon to evening. Harvesting during the rainy season will slow down post-harvest work and can cause damage to the rice. If the paddy is left in the field too long, it causes shedding and crop failure. Meanwhile, rice collected in a particular place can return to sprouts quickly if exposed to continuous water. Such a situation forces farmers to return the paddy home in a dirty state. Cleaning, separating the grains, and drying the paddy was done in the courtyard of the house in a limited and slow manner.

4. Conclusions

This research needs to be known by stakeholders, such as the government and those with the resources to make policy. Understanding farmers' awareness of climate change in the tropics should be understood as an approach to conducting early adaptation strategies in upland rice farming. Farmers in this area, irrigated and non-irrigated rice farmers, have a concept of climate change that is not the same as those of other communities. Climate change is only interpreted when rain, water discharge, drought, or wind are extreme. The fading of traditional knowledge in rice farming due to climate change will be caused by adjustments and other adaptation strategies based on traditional knowledge that they already have. The inability of traditional knowledge owned by the community to predict or read the climate changes causes the community's traditional knowledge to begin to fade. All efforts made by the community to survive any impact caused by climate change have failed. In the end, local communities choose to surrender to the situation. Currently, farmers can only take advantage of fertilizer subsidies provided by the government and wait for the rains to come. The reality of the farmers' conditions above shows that the local government must take action against the agricultural failures experienced by the community. The government is no longer just assisting with fertilizer and seed subsidies, but the government must make efforts to help farmers deal with climate change. Some of the efforts made by the government include providing information about climate change that occurs to farmers [

58,

59], providing training related to mitigation and adaptation efforts that can be carried out by farmers so that farmers can an understanding of climate change that occurs [

60,

61] and no less important is understanding traditional agriculture as a climate-smart approach for the sustainable food production and also deliberates the correlation between climate change and traditional agriculture [

62,

63,

64]. This is related to regional food security, which is one of the targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author, as the data will be used for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: RI, ER, SL, RM, DS; Methodology: RI, EHK, RS; Writing—original draft preparation: RI, ER, SL, RM, BH; Writing—review and editing: EHK, RS, RHH, DS; Visualization: RHH, DS; Supervision: RI, BH; Project Administration: RS, DS; Formal Analysis: ER, RM; Investigation: SL, RM; Funding Acquisition: BH, RM; Data Curation: RHH. After several reviews and edits, all authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Talenta Fund Research Universitas Sumatera Utara by Research Contract Number: 11119.1/UN5.1. R/PPM/2022, dated 08 August 2022.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Research Ethics Committee of The Social and Political Faculty, Universitas Sumatera Utara approved the research proposal including its ethical procedures, before data collection began. Consents were obtained from the participants and their data were kept confidential.

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the farmers in Samosir Regency who helped researchers in sharing their stories about this topic research. The author also thanks the Universitas Sumatera Utara as the institution that funded this research.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest. “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- S. Hallegatte, M. Fay, and E. B. Barbier, “Poverty and climate change: Introduction,” Environ. Dev. Econ., vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 217–233, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Hallegatte and J. Rozenberg, “Climate change through a poverty lens,” Nat. Clim. Chang., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 250–256, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Taylor, “Climate change and development,” Essent. Guid. to Crit. Dev. Stud., pp. 311–318, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. L. Indraswari, “Mitigasi Perubahan Iklim Turut Mencegah Peningkatan Kemiskinan,” Kompas.com, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.kompas.id/baca/riset/2022/09/16/mitigasi-perubahan-iklim-turut-mencegah-peningkatan-kemiskinan.

- Bapenas, “Institutional Arrangement for Climate Resilience.,” Jakarta, 2021.

- C. A. Otekhile and N. Verter, “The socioeconomic characteristics of rural farmers and their net income in OJO and Badagry local government areas of Lagos state, Nigeria,” Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendelianae Brun., vol. 65, no. 6, pp. 2037–2043, 2017. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen and S. Chen, “China feels the heat: negative impacts of high temperatures on China’s rice sector,” Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ., vol. 62, no. 4, pp. 576–588, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sumiati, Musdalipa, A. T. Darhyati, A. T. Fitriyah, Baharuddin, and F. Ma, “The impact of climate change on agricultural production with a cases study of Lake Tempe, district of Wajo, South Sulawesi,” EurAsian J. Biosci. , vol. 14, no. March, pp. 6761–6771, 2020.

- B. S. Choudri, A. Al-Busaidi, and M. Ahmed, “Climate change, vulnerability and adaptation experiences of farmers in Al-Suwayq Wilayat, Sultanate of Oman,” Int. J. Clim. Chang. Strateg. Manag., vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 445–454, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Zakari, G. Ibro, B. Moussa, and T. Abdoulaye, “Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change and Impacts on Household Income and Food Security: Evidence from Sahelian Region of Niger,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. O. Popoola, S. F. G. Yusuf, and N. Monde, “South African national climate change response policy sensitization: An assessment of smallholder farmers in Amathole District Municipality, Eastern Cape Province,” Sustain., vol. 12, no. 7, pp. 20–24, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. D. Hewitt et al., “Making Society Climate Resilient,” Am. Meteorol. Soc., no. October 2019, pp. 237–252, 2020.

- G. Nsengiyumva et al., “Transforming access to and use of climate information products derived from remote sensing and in situ observations,” Remote Sens., vol. 13, no. 22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Obsi Gemeda, D. Korecha, and W. Garedew, “Determinants of climate change adaptation strategies and existing barriers in Southwestern parts of Ethiopia,” Clim. Serv., vol. 30, no. February, p. 100376, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Fahad et al., “Crop production under drought and heat stress: Plant responses and management options,” Front. Plant Sci., vol. 8, no. June, pp. 1–16, 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Benkeblia, Agroecology, Ecosystems, and Sustainability. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Yu, D. A. Hennessy, J. Tack, and F. Wu, “Climate change will increase aflatoxin presence in US Corn,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 17, no. 5, p. 054017, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Malhi, M. Kaur, and P. Kaushik, “Impact of climate change on agriculture and its mitigation strategies: A review,” Sustain., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 1–21, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Destaw and M. Fenta, “Climate change adaptation strategies and their predictors amongst rural farmers in Ambassel district, Northern Ethiopia,” Jàmbá J. Disaster Risk Stud., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–11, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Begum and R. Mahanta, “Adaptation to climate change and factors affecting it in Assam,” Indian J. Agric. Econ., vol. 72, no. 3, pp. 446–455, 2017.

- M. F. Olabanji, N. Davis, T. Ndarana, A. G. Kuhudzai, and D. Mahlobo, “Assessment of smallholder farmers’ perception and adaptation response to climate change in the olifants catchment, South Africa,” J. Water Clim. Chang., vol. 12, no. 7, pp. 3388–3403, 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. O. Abidoye, P. Kurukulasuriya, and R. Mendelsohn, “SOUTH-EAST ASIAN FARMER PERCEPTIONS of CLIMATE CHANGE,” Clim. Chang. Econ., vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 1–8, 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. P. H. D, N. S. Athira, and B. Mathew, “Climate Change Adaptation : A Global Review of Farmers Strategies Climate Change Adaptation : A Global Review of Farmers Strategies,” no. November, 2023.

- R. M. Adams, B. H. Hurd, S. Lenhart, and N. Leary, “Effects of global climate change on agriculture: An interpretative review,” Clim. Res., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 19–30, 1999. [CrossRef]

- E. Grigorieva, A. Livenets, and E. Stelmakh, “Adaptation of Agriculture to Climate Change: A Scoping Review,” Climate, vol. 11, no. 10, pp. 1–37, 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Wiréhn, “Nordic agriculture under climate change: A systematic review of challenges, opportunities and adaptation strategies for crop production,” Land use policy, vol. 77, no. April, pp. 63–74, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Kiley, “Growth at risk from climate change,” Econ. Inq., Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Niles, M. Lubell, and V. R. Haden, “Perceptions and responses to climate policy risks among california farmers,” Glob. Environ. Chang., vol. 23, no. 6, pp. 1752–1760, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Rosenzweig et al., “Assessing agricultural risks of climate change in the 21st century in a global gridded crop model intercomparison,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 111, no. 9, pp. 3268–3273, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Petersen-Rockney, “Farmers adapt to climate change irrespective of stated belief in climate change: a California case study,” Clim. Change, vol. 173, no. 3–4, pp. 1–31, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Mugagga, A. Nimusiima, and J. Elepu, “An Appraisal of Adaptation Measures to Climate Variability by Smallholder Irish Potato Farmers in South Western Uganda,” Am. J. Clim. Chang., vol. 09, no. 03, pp. 228–242, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Shrestha, N. Raut, L. Swe, and T. Tieng, “Climate Change Adaptation Strategies in Agriculture: Cases from Southeast Asia,” Sustain. Agric. Res., vol. 7, no. 3, p. 39, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Fachri, K. Tarigan, and H. Hasyim, “Perbedaan Produksi dan Pendapatan Usahatani Padi Sawah Sistem Irigasi Teknis dengan Sistem Pompanisasi (Studi Kasus: Desa Makmur, Kec. Teluk Mengkudu, Kab. Serdang Bedagai, Dan Di Desa Sei Rejo, Kec. Sei Rampah, Kab. Serdang Bedagai).,” Universitas Sumatera Utara, 2014.

- R. Ismail, R. Manurung, D. Sihotang, H. M. Munthe, and I. Tiar, “Specialization of skills and traditional treatment methods by namalo in batak toba community, Indonesia,” Stud. Ethno-Medicine, vol. 13, no. 4, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Manurung, R. Ismail, and H. Daulay, “Namalo - Traditional healer in Batak Toba Society, Indonesia: Knowledge of drug and traditional treatment process,” Man India, vol. 97, no. 24, pp. 369–384, 2017.

- R. Manurung, R. Ismail, H. M. Munthe, and T. S. Nababan, “Batak toba empowerment in lake toba tourism area, North Sumatera, Indonesia: Analysis of entrepreneurship potential in batak women,” Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res., vol. 9, no. 3, 2020.

- E. Revida, R. Ismail, P. Lumbanraja, F. Trimurni, S. A. B. Sembiring, and S. Purba, “The Effectiveness of Attractions in Increasing the Visits of Tourists in Samosir, North Sumatera,” J. Environ. Manag. Tour., vol. 13, no. 8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Silaban, R. Sibarani, and M. E. Fachry, “Indahan siporhis ‘the very best boiled rice mixed with herbs and species’ for the women’s mental and physical health in ritual of traditional agricultural farming,” Enfermería Clínica, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 354–356, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Petersen-Rockney et al., “Narrow and Brittle or Broad and Nimble? Comparing Adaptive Capacity in Simplifying and Diversifying Farming Systems,” Front. Sustain. Food Syst., vol. 5, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Davidson, C. Rollins, L. Lefsrud, S. Anders, and A. Hamann, “Just don’t call it climate change: climate-skeptic farmer adoption of climate-mitigative practices,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 1–10, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Arbuckle et al., “Climate change beliefs, concerns, and attitudes toward adaptation and mitigation among farmers in the Midwestern United States,” Clim. Change, vol. 117, no. 4, pp. 943–950, 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. Stuart, R. L. Schewe, and M. McDermott, “Responding to Climate Change,” Organ. Environ., vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 308–327, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Schewe and D. Stuart, “Why Don’t They Just Change? Contract Farming, Informational Influence, and Barriers to Agricultural Climate Change Mitigation,” Rural Sociol., vol. 82, no. 2, pp. 226–262, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. Grantham, F. Kearns, S. Kocher, L. Roche, and T. Pathak, “Building climate change resilience in California through UC Cooperative Extension,” Calif. Agric., vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 197–200, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Silalahi, Nisyawati, and D. Pandiangan, “Medicinal plants used by the Batak Toba tribe in Peadundung Village, North Sumatra, Indonesia,” Biodiversitas, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 510–525, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. D. H. Sitanggang, E. A. M. Zuhud, B. Masy’ud, and R. Soekmadi, “Ethnobotany of the Toba Batak Ethnic Community in Samosir District, North Sumatra, Indonesia,” Biodiversitas, vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 6114–6118, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. He et al., “Agricultural diversification promotes sustainable and resilient global rice production,” Nat. Food, vol. 4, no. 9, pp. 788–796, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Li et al., “Crop diversification promotes soil aggregation and carbon accumulation in global agroecosystems: A meta-analysis,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 350, no. November 2023, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Griffin et al., “The persistence of precarity: youth livelihood struggles and aspirations in the context of truncated agrarian change, South Sulawesi, Indonesia,” Agric. Human Values, vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 293–311, 2024. [CrossRef]

- I. Hashmiu, F. Adams, S. Etuah, and J. Quaye, “Food-cash crop diversification and farm household welfare in the Forest-Savannah Transition Zone of Ghana,” Food Secur., vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 487–509, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Ajetomobia, A. Abiodunb, and R. Hassanc, “Impacts of climate change on rice agriculture in Nigeria,” Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 613–622, 2011.

- T. Hu et al., “Climate change impacts on crop yields: A review of empirical findings, statistical crop models, and machine learning methods,” Environ. Model. Softw., vol. 179, p. 106119, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Kemi, A. A., & Olusegun, “Climate Change impact on cassava agriculture in Nigeria,” J. Xi’an Shiyou Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed., vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 22–31, 2020.

- S. Li, F. Wu, Q. Zhou, and Y. Zhang, “Adopting agronomic strategies to enhance the adaptation of global rice production to future climate change: a meta-analysis,” Agron. Sustain. Dev., vol. 44, no. 3, 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. A. Alotaibi, M. B. Baig, M. M. M. Najim, A. A. Shah, and Y. A. Alamri, “Water Scarcity Management to Ensure Food Scarcity through Sustainable Water Resources Management in Saudi Arabia,” Sustain., vol. 15, no. 13, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Suntoro, M. Mujiyo, H. Widijanto, and G. Herdiansyah, “Cultivation of rice (Oryza sativa), corn (zea mays) and soybean (glycine max) based on land suitability,” J. Settlements Spat. Plan., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 9–16, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Anuja, A. Kumar, S. Saroj, and K. N. Singh, The impact of crop diversification towards high-value crops on economic welfare of agricultural households in eastern India, vol. 118, no. 10. Routledge, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. S. Berck, P. Berck, and S. Di Falco, Eds., Agricultural Adaptation to Climate Change in Africa. New York, NY : RFF Press, 2018.: Routledge, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Hogarth, Climate change and the USDA: Agency efforts, challenges, and plans. UK: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2015.

- P. Dorward, G. Clarkson, S. Poskitt, and R. Stern, “Putting the farmer at the center of climate services,” One Earth, vol. 4, no. 8, pp. 1059–1061, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Lane, A. Chatrchyan, D. Tobin, K. Thorn, S. Allred, and R. Radhakrishna, “Climate change and agriculture in New York and Pennsylvania: risk perceptions, vulnerability and adaptation among farmers,” Renew. Agric. Food Syst., vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 197–205, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Singh and G. S. Singh, “Traditional agriculture: a climate-smart approach for sustainable food production,” Energy, Ecol. Environ., vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 296–316, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. T. Erekalo and T. A. Yadda, “Climate-smart agriculture in Ethiopia: Adoption of multiple crop production practices as a sustainable adaptation and mitigation strategies,” World Dev. Sustain., vol. 3, p. 100099, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Mbanasor et al., “Climate smart agriculture practices by crop farmers: Evidence from south east Nigeria,” Smart Agric. Technol., vol. 8, p. 100494, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

Table 2.

Behavior of Irrigated Rice Farmers and Non-irrigated Rice Farmers in Facing Climate Change.

Table 2.

Behavior of Irrigated Rice Farmers and Non-irrigated Rice Farmers in Facing Climate Change.

| Adaptation Strategies of Irrigated and Non-irrigated Rice Farmers |

The percentage |

| Have experienced crop failure due to climate change |

72 (55.4%) |

| Farmers are not aware of low emission rice varieties |

80 (61.5%) |

| Joining a farmer group |

119 (91.5%) |

| Farmer groups do not share information on climate change |

93 (71.4%) |

| Farming systems no longer depend on climate change information |

114 (87.7%) |

| Making changes to the harvest period due to erratic and sudden changes in the weather |

70 (53.8 %) |

| Changes in agricultural productivity |

119 (91.1%) |

| Loss of farmers' traditional knowledge related to rainy and dry season schedules |

126 (96.7%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).