Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

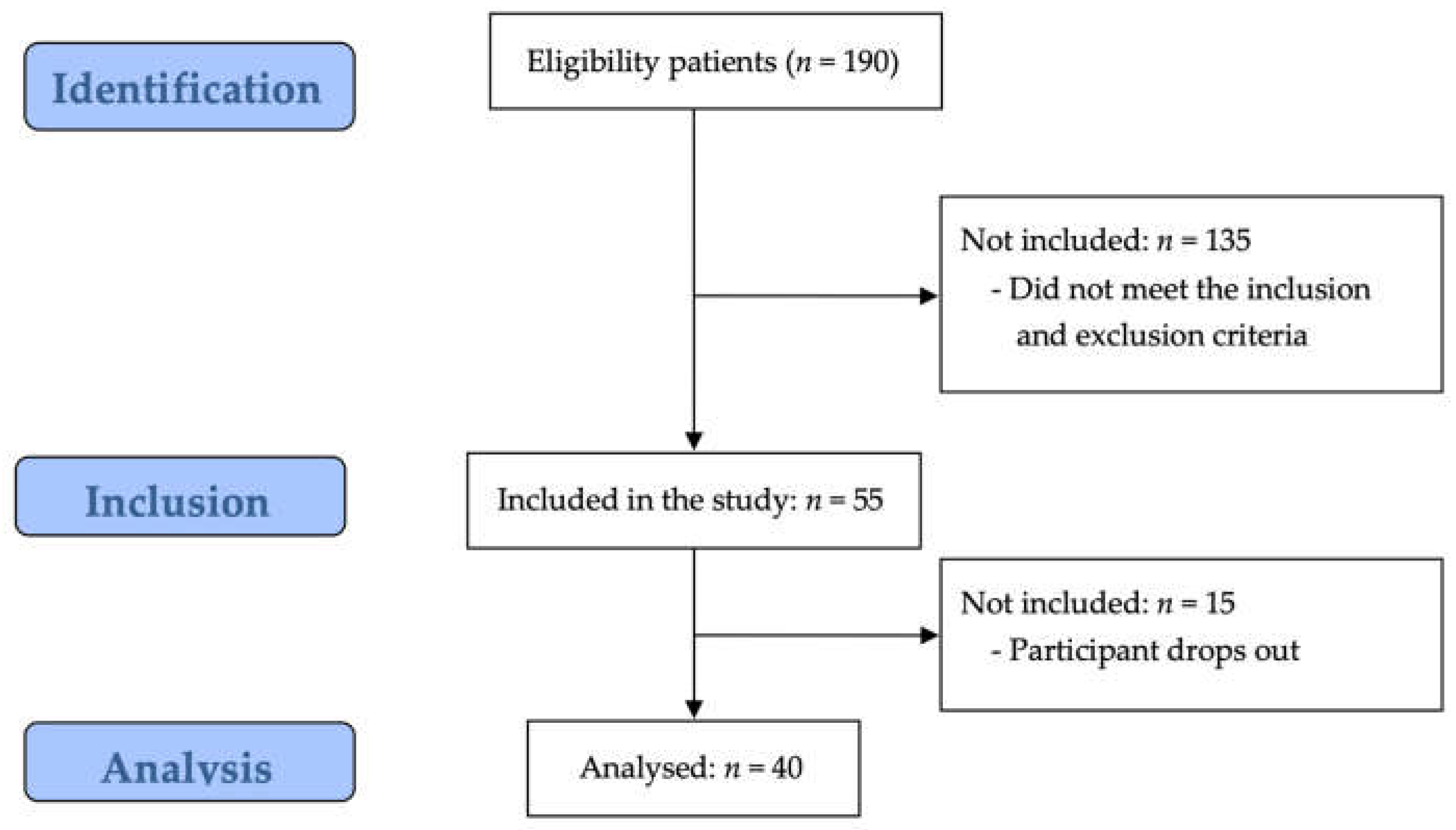

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Ethics

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Outcomes

2.4.1. Central Sensitization

2.4.2. Respiratory Mobility

2.4.3. Respiratory Pattern

2.4.4. Respiratory Strength

2.4.5. Muscle Tone & Muscle Stiffness

2.4.6. Pain Intensity

2.4.6. Pain Cognition

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Participant Characteristics

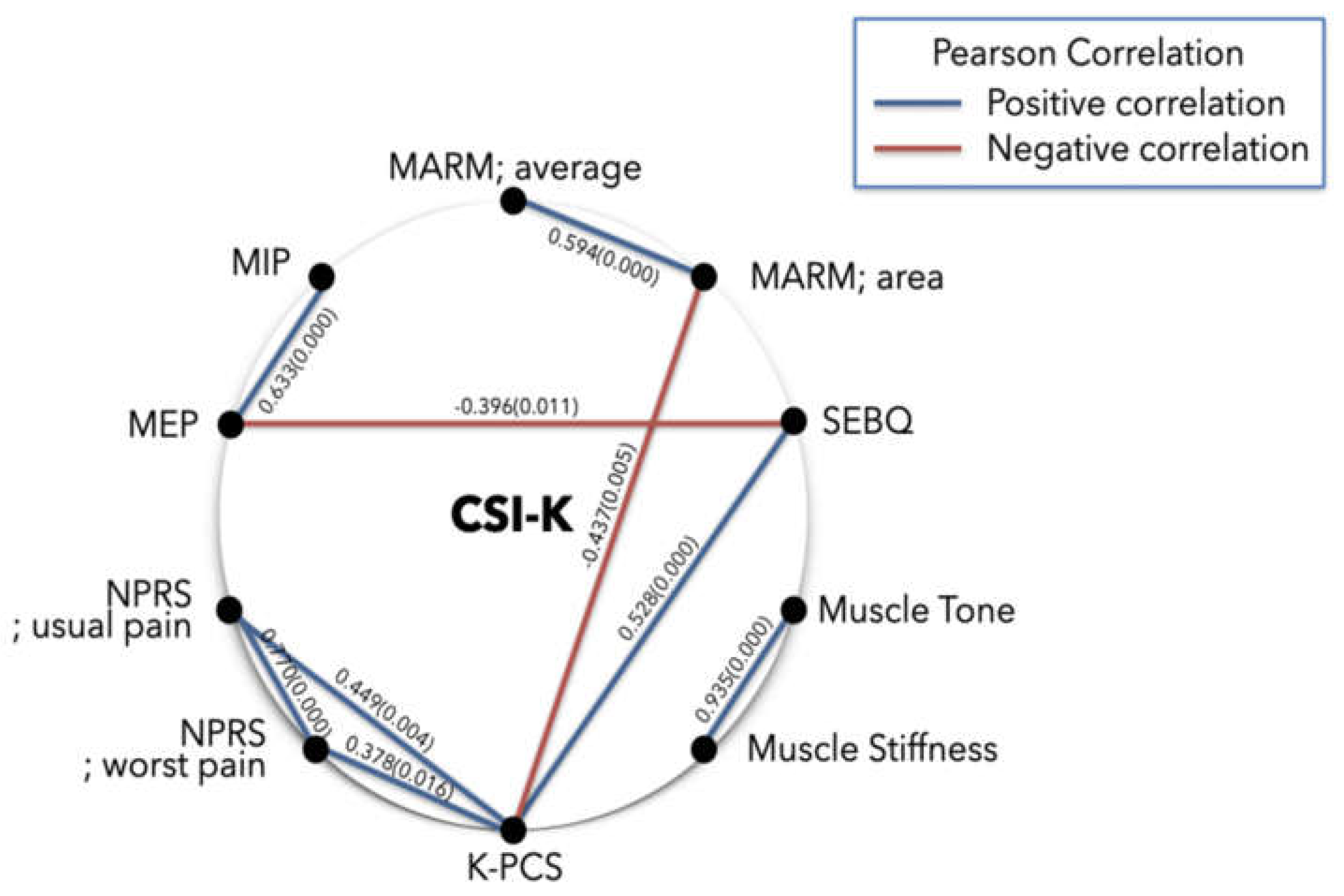

3.2. Correlation Analysis Between Variables

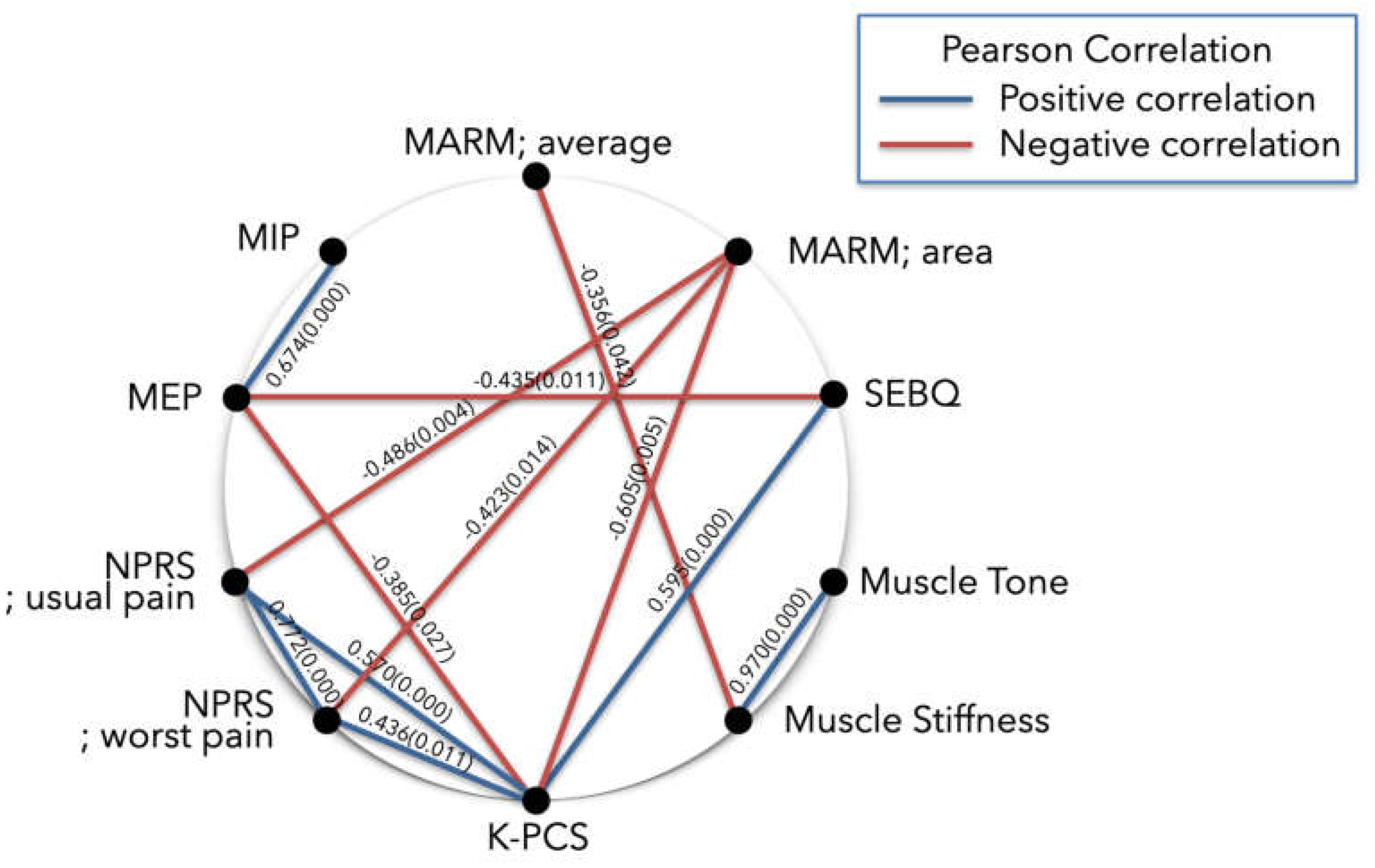

3.2.1. Subanalysis: MARM; Average (≥100 Degrees)

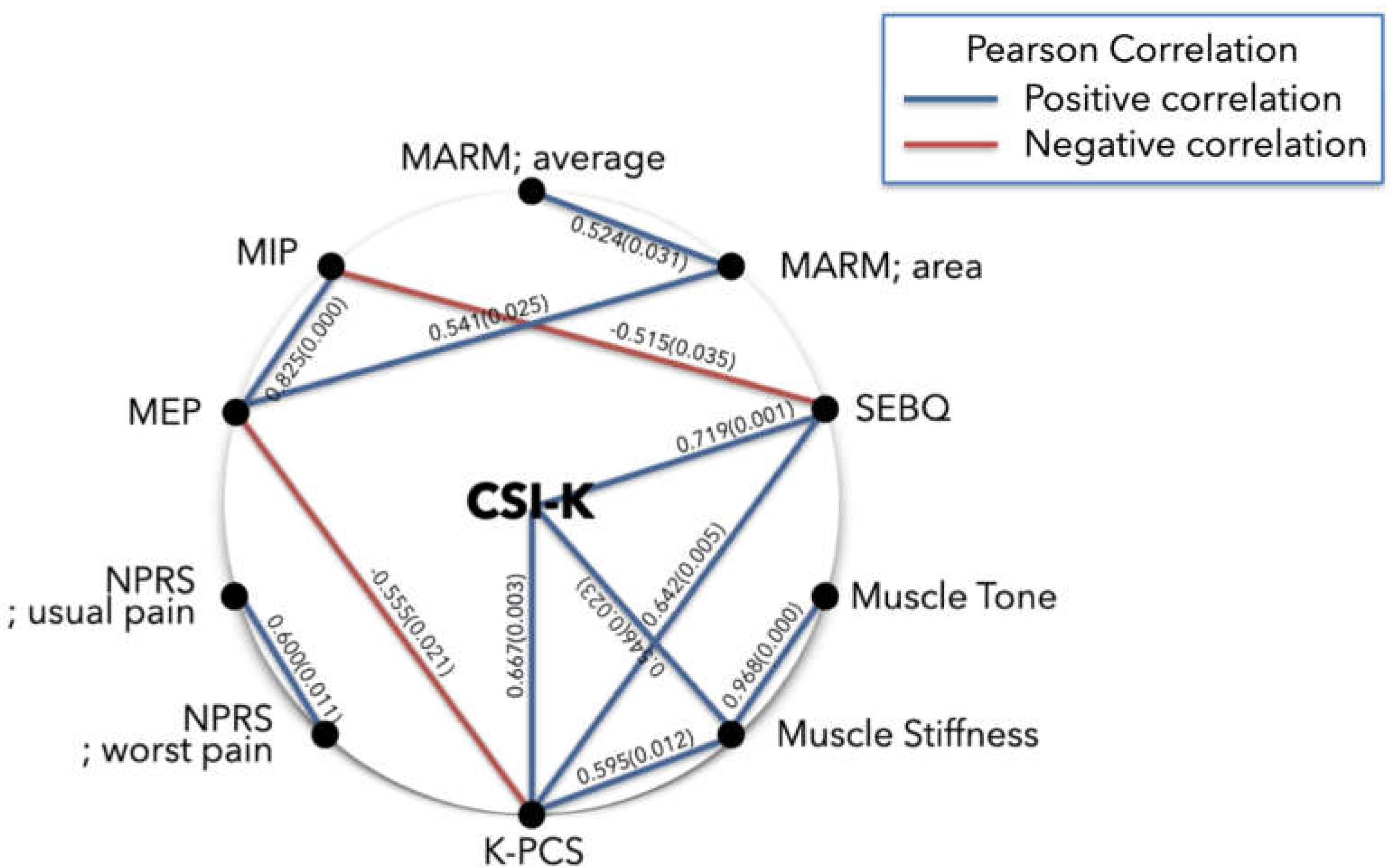

3.2.2. Subanalysis: NPRS; Usual Pain (≥ 4 points)

3.3. Regression Analysis Between Variables

3.3.1. Simple Regression Analysis

3.3.2. Multiple Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woolf, Clifford "Central Sensitization: Implications for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pain." Pain 152, no. 3 (2011): S2-S15.

- Jafari, H.; Gholamrezaei, A.; Franssen, M.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Aziz, Q.; Bergh, O.V.D.; Vlaeyen, J.W.; Van Diest, I. Can Slow Deep Breathing Reduce Pain? An Experimental Study Exploring Mechanisms. J. Pain 2020, 21, 1018–1030. [CrossRef]

- Aydede, Murat "Defending the Iasp Definition of Pain." The Monist 100, no. 4 (2017): 439-64.

- Staud, R.; Craggs, J.G.; Robinson, M.E.; Perlstein, W.M.; Price, D.D. Brain activity related to temporal summation of C-fiber evoked pain. Pain 2007, 129, 130–142. [CrossRef]

- Wijma, A.J.; van Wilgen, C.P.; Meeus, M.; Nijs, J. Clinical biopsychosocial physiotherapy assessment of patients with chronic pain: The first step in pain neuroscience education. Physiother. Theory Pr. 2016, 32, 368–384. [CrossRef]

- Harte, S.E.; Harris, R.E.; Clauw, D.J. The neurobiology of central sensitization. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2018, 23, e12137. [CrossRef]

- Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Morlion, B.; Perrot, S.; Dahan, A.; Dickenson, A.; Kress, H.G.; Wells, C.; Bouhassira, D.; Drewes, A.M. Assessment and manifestation of central sensitisation across different chronic pain conditions. Eur. J. Pain 2018, 22, 216–241. [CrossRef]

- Kindler, L.L.; Bennett, R.M.; Jones, K.D. Central Sensitivity Syndromes: Mounting Pathophysiologic Evidence to Link Fibromyalgia with Other Common Chronic Pain Disorders. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2009, 12, 15–24. [CrossRef]

- Lluch, E.; Torres, R.; Nijs, J.; Van Oosterwijck, J. Evidence for central sensitization in patients with osteoarthritis pain: A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Pain 2014, 18, 1367–1375. [CrossRef]

- Solem, I.K.L.; Varsi, C.; Eide, H.; Kristjansdottir, O.B.; Børøsund, E.; Schreurs, K.M.G.; Waxenberg, L.B.; E Weiss, K.; Morrison, E.J.; Haaland-Øverby, M.; et al. A User-Centered Approach to an Evidence-Based Electronic Health Pain Management Intervention for People With Chronic Pain: Design and Development of EPIO. J. Med Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15889. [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Yeung, A.; Quan, X.; Boyden, S.D.; Wang, H. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Mindfulness-Based (Baduanjin) Exercise for Alleviating Musculoskeletal Pain and Improving Sleep Quality in People with Chronic Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2018, 15, 206. [CrossRef]

- Wyns, A.; Hendrix, J.; Lahousse, A.; De Bruyne, E.; Nijs, J.; Godderis, L.; Polli, A. The Biology of Stress Intolerance in Patients with Chronic Pain—State of the Art and Future Directions. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2245. [CrossRef]

- Neblett, R.; Hartzell, M.M.; Mayer, T.G.; Cohen, H.; Gatchel, R.J. Establishing Clinically Relevant Severity Levels for the Central Sensitization Inventory. Pain Pr. 2016, 17, 166–175. [CrossRef]

- Kiesel, K.; Rhodes, T.; Mueller, J.; Waninger, A.; Butler, R. DEVELOPMENT OF A SCREENING PROTOCOL TO IDENTIFY INDIVIDUALS WITH DYSFUNCTIONAL BREATHING. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2017, 12, 774–786. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jung, J.; Lee, S. Prefrontal Cortex Activation during Diaphragmatic Breathing in Women with Fibromyalgia: An fNIRS Case Report. Phys. Ther. Rehabilitation Sci. 2023, 12, 334–339. [CrossRef]

- CliftonSmith, T.; Rowley, J. Breathing pattern disorders and physiotherapy: inspiration for our profession. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2011, 16, 75–86. [CrossRef]

- Chaitow, Leon "Breathing Pattern Disorders, Motor Control, and Low Back Pain." Int J Osteopath Med 7, no. 1 (2004): 33-40.

- Courtney, Rosalba "The Functions of Breathing and Its Dysfunctions and Their Relationship to Breathing Therapy." Int J Osteopath Med 12, no. 3 (2009): 78-85.

- Crockett, H.C.; Gross, L.B.; Wilk, K.E.; Schwartz, M.L.; Reed, J.; Omara, J.; Reilly, M.T.; Dugas, J.R.; Meister, K.; Lyman, S.; et al. Osseous Adaptation and Range of Motion at the Glenohumeral Joint in Professional Baseball Pitchers. Am. J. Sports Med. 2002, 30, 20–26. [CrossRef]

- Scascighini, L, V Toma, Sprott Dober-Spielmann, and Haiko Sprott. "Multidisciplinary Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review of Interventions and Outcomes." Rheumatol 47, no. 5 (2008): 670-78.

- Neblett, R. The central sensitization inventory: A user’s manual. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2018, 23. [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.D.O.; Rathleff, M.S.; Petersen, K.; de Azevedo, F.M.; Barton, C.J. Manifestations of Pain Sensitization Across Different Painful Knee Disorders: A Systematic Review Including Meta-analysis and Metaregression. Pain Med. 2018, 20, 335–358. [CrossRef]

- Arribas-Romano, A.; Fernández-Carnero, J.; Molina-Rueda, F.; Angulo-Diaz-Parreño, S.; Navarro-Santana, M.J. Efficacy of Physical Therapy on Nociceptive Pain Processing Alterations in Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 2502–2517. [CrossRef]

- Martarelli, D.; Cocchioni, M.; Scuri, S.; Pompei, P. Diaphragmatic Breathing Reduces Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 932430. [CrossRef]

- O’sullivan, P.B.; Beales, D.J. Diagnosis and classification of pelvic girdle pain disorders—Part 1: A mechanism based approach within a biopsychosocial framework. Man. Ther. 2007, 12, 86–97. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Koh, I.J.; Kim, C.K.; Choi, K.Y.; Kim, C.Y.; In, Y. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Korean version of the Central Sensitization Inventory in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty for knee osteoarthritis. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0242912. [CrossRef]

- Crockett, J.E.; Cashwell, C.S.; Tangen, J.L.; Hall, K.H.; Young, J.S. Breathing Characteristics and Symptoms of Psychological Distress: An Exploratory Study. Couns. Values 2016, 61, 10–27. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, T.G.; Neblett, R.; Cohen, H.; Howard, K.J.; Choi, Y.H.; Williams, M.J.; Perez, Y.; Gatchel, R.J. The Development and Psychometric Validation of the Central Sensitization Inventory. Pain Pr. 2011, 12, 276–285. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Koh, I.J.; Lee, S.Y.; In, Y. Central sensitization is a risk factor for wound complications after primary total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2018, 26, 3419–3428. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S. Effects of pain neuroscience education on kinesiophobia in patients with chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys. Ther. Rehabilitation Sci. 2020, 9, 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Courtney, R.; van Dixhoorn, J. "Questionnaires and Manual Methods for Assessing Breathing Dysfunction." Recog treat breath disor (2014): 137-46.

- Yach, B.; Linens, S.W. The Relationship Between Breathing Pattern Disorders and Scapular Dyskinesis. Athl. Train. Sports Heal. Care 2019, 11, 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Courtney, R.; Biland, G.; Ryan, A.; Grace, S.; Gordge, R. Improvements in multi-dimensional measures of dysfunctional breathing in asthma patients after a combined manual therapy and breathing retraining protocol: a case series report. Int. J. Osteopat. Med. 2019, 31, 36–43. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Bacon, C.J.; Moran, R.W. Reliability and Determinants of Self-Evaluation of Breathing Questionnaire (SEBQ) Score: A Symptoms-Based Measure of Dysfunctional Breathing. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2015, 41, 111–120. [CrossRef]

- Sriboonreung, T.; Leelarungrayub, J.; Yankai, A.; Puntumetakul, R. Correlation and Predicted Equations of MIP/MEP from the Pulmonary Function, Demographics and Anthropometrics in Healthy Thai Participants aged 19 to 50 Years. Clin. Med. Insights: Circ. Respir. Pulm. Med. 2021, 15. [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.-R.; Kim, N.-S. The correlation of respiratory muscle strength and cough capacity in stroke patients. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 2803–2805. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Kyeongbong "Correlation between Respiratory Muscle Strength and Pulmonary Function with Respiratory Muscle Length Increase in Healthy Adults." Phys Ther Rehabil Sci 10, no. 4 (2021): 398-405.

- Ko, C.-Y.; Choi, H.-J.; Ryu, J.; Kim, G. Between-day reliability of MyotonPRO for the non-invasive measurement of muscle material properties in the lower extremities of patients with a chronic spinal cord injury. J. Biomech. 2018, 73, 60–65. [CrossRef]

- Kim, CS, and MK Kim. "Mechanical Properties and Physical Fitness of Trunk Muscles Using Myoton." Korean J Phys Edu 55, no. 1 (2016): 633-42.

- Kim, Kyu Ryeong, Houng Soo Shin, Sang Bin Lee, Hyun Sook Hwang, and Hee Joon %J Journal of international academy of physical therapy research Shin. "Effects of Negative Pressure Soft Tissue Therapy to Ankle Plantar Flexor on Muscle Tone, Muscle Stiffness, and Balance Ability in Patients with Stroke." 9, no. 2 (2018): 1468-74.

- Ferraz, M.; Quaresma; Aquino, L.; Atra, E.; Tugwell, P.; Goldsmith, C. RELIABILITY OF PAIN SCALES IN THE ASSESSMENT OF LITERATE AND ILLITERATE PATIENTS WITH RHEUMATOID-ARTHRITIS. 1990, 17, 1022–1024.

- Rodriguez, Carmen S "Pain Measurement in the Elderly: A Review." Pain Manag Nurs 2, no. 2 (2001): 38-46.

- Jensen, Rigmor, Birthe Krogh Rasmussen, Birthe Pedersen, and Jes Olesen. "Muscle Tenderness and Pressure Pain Thresholds in Headache. A Population Study." Pain 52, no. 2 (1993): 193-99.

- Kang, H.; Uhm, J.-Y. Validation of the PAINAD-K Scale for Nonverbal Pain Assessment in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit. J. Korean Acad. Fundam. Nurs. 2023, 30, 90–101. [CrossRef]

- Darnall, B.D.; Sturgeon, J.A.; Cook, K.F.; Taub, C.J.; Roy, A.; Burns, J.W.; Sullivan, M.; Mackey, S.C. Development and Validation of a Daily Pain Catastrophizing Scale. J. Pain 2017, 18, 1139–1149. [CrossRef]

- Franchignoni, F.; Giordano, A.; Ferriero, G.; Monticone, M. Measurement precision of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale and its short forms in chronic low back pain. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kim, H.-Y.; Lee, J.-H. Validation of the Korean version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale in patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 22, 1767–1772. [CrossRef]

- Courtney, R.; van Dixhoorn, J.; Cohen, M. Evaluation of Breathing Pattern: Comparison of a Manual Assessment of Respiratory Motion (MARM) and Respiratory Induction Plethysmography. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2008, 33, 91–100. [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, S.N.; Critchley, H.D. Threat and the Body: How the Heart Supports Fear Processing. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2015, 20, 34–46. [CrossRef]

- Gea, J.; Casadevall, C.; Pascual, S.; Orozco-Levi, M.; Barreiro, E. Respiratory diseases and muscle dysfunction. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2012, 6, 75–90. [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; George, S.Z.; Clauw, D.J.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Kosek, E.; Ickmans, K.; Fernández-Carnero, J.; Polli, A.; Kapreli, E.; Huysmans, E.; et al. Central sensitisation in chronic pain conditions: latest discoveries and their potential for precision medicine. 2021, 3, e383–e392. [CrossRef]

- Gifford, L.S.; Butler, D.S. The integration of pain sciences into clinical practice. J. Hand Ther. 1997, 10, 86–95. [CrossRef]

- Giardino, N.D.; Curtis, J.L.; Abelson, J.L.; King, A.P.; Pamp, B.; Liberzon, I.; Martinez, F.J. The impact of panic disorder on interoception and dyspnea reports in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Biol. Psychol. 2010, 84, 142–146. [CrossRef]

- Jerath, R.; Crawford, M.W.; Barnes, V.A.; Harden, K. Self-Regulation of Breathing as a Primary Treatment for Anxiety. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2015, 40, 107–115. [CrossRef]

- Courtney, R.; van Dixhoorn, J.; Greenwood, K.M.; Anthonissen, E.L.M.; Do; M.D.; Ph.D. Medically Unexplained Dyspnea: Partly Moderated by Dysfunctional (Thoracic Dominant) Breathing Pattern. J. Asthma 2011, 48, 259–265. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A.; Hoggart, B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J. Clin. Nurs. 2005, 14, 798–804. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, C.N.; Porta, C.; Casucci, G.; Casiraghi, N.; Maffeis, M.; Rossi, M.; Bernardi, L. Slow Breathing Improves Arterial Baroreflex Sensitivity and Decreases Blood Pressure in Essential Hypertension. Hypertension 2005, 46, 714–718. [CrossRef]

- Zaccaro, A.; Piarulli, A.; Laurino, M.; Garbella, E.; Menicucci, D.; Neri, B.; Gemignani, A. How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 353. [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.A.; Santarelli, D.M.; O’rourke, D. The physiological effects of slow breathing in the healthy human. Breathe 2017, 13, 298–309. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Louvaris, Z.; Dacha, S.; Janssens, W.; Pitta, F.; Vogiatizis, I.; Gosselink, R.; Langer, D. Differences in Respiratory Muscle Responses to Hyperpnea or Loaded Breathing in COPD. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 52, 1126–1134. [CrossRef]

- Laghi, F.; Tobin, M.J. Disorders of the Respiratory Muscles. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 168, 10–48. [CrossRef]

- Klein, T.; Magerl, W.; Hopf, H.-C.; Sandkühler, J.; Treede, R.-D. Perceptual Correlates of Nociceptive Long-Term Potentiation and Long-Term Depression in Humans. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 964–971. [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, B.; Marelli, F.; Morabito, B.; Sacconi, B. Depression, anxiety and chronic pain in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the influence of breath. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2017, 87, 811–811. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Seymour, B. Technology for Chronic Pain. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R930–R935. [CrossRef]

- Latremoliere, A.; Woolf, C.J. Central Sensitization: A Generator of Pain Hypersensitivity by Central Neural Plasticity. 2009, 10, 895–926. [CrossRef]

- de Tommaso, M.; Delussi, M.; Vecchio, E.; Sciruicchio, V.; Invitto, S.; Livrea, P. Sleep features and central sensitization symptoms in primary headache patients. J. Headache Pain 2014, 15, 64–64. [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, M.; Vlaeyen, J.W.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Giamberardino, M.A.; Goebel, A.; et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. PAIN® 2019, 160, 28–37. [CrossRef]

- Thanapal, M. R., M. D. Tata, A. J. Tan, T. Subramaniam, J. M. Tong, K. Palayan, S. Rampal, and R. Gurunathan. "Pre-Emptive Intraperitoneal Local Anaesthesia: An Effective Method in Immediate Post-Operative Pain Management and Metabolic Stress Response in Laparoscopic Appendicectomy, a Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Study." ANZ J Surg 84, no. 1-2 (2014): 47-51.

- Kirk, E.A.; Gilmore, K.J.; Stashuk, D.W.; Doherty, T.J.; Rice, C.L. Human motor unit characteristics of the superior trapezius muscle with age-related comparisons. J. Neurophysiol. 2019, 122, 823–832. [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean±SD |

|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 7/33 |

| Age (years) | 56.38±8.05 |

| Height (cm) | 160.75±5.96 |

| Weight (kg) | 61.50±9.00 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.80±3.29 |

| Variables | CSI-K | MARM; average | MARM; area | MIP | MEP | SEBQ | NPRS; usual pain | NPRS; worst pain | K-PCS | Muscle tone |

Muscle stiffness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSI-K | 1 | ||||||||||

| MARM; average |

0.138 | 1 | |||||||||

| MARM; area |

0.003 | 0.594** | 1 | ||||||||

| MIP | 0.141 | 0.213 | 0.184 | 1 | |||||||

| MEP | -0.121 | 0.137 | 0.131 | 0.633** | 1 | ||||||

| SEBQ | 0.209 | -0.058 | -0.142 | -0.302 | -0.396* | 1 | |||||

| NPRS; usual pain | 0.050 | 0.000 | -0.275 | 0.001 | -0.080 | 0.285 | 1 | ||||

| NPRS; worst pain | 0.221 | -0.037 | -0.217 | -0.039 | -0.155 | 0.134 | 0.770** | 1 | |||

| K-PCS | 0.144 | -0.038 | -0.437* | -0.267 | -0.278 | 0.528** | 0.449** | 0.378* | 1 | ||

| Muscle tone |

0.074 | -0.123 | -0.005 | -0.160 | -0.052 | 0.204 | -0.058 | -0.119 | 0.243 | 1 | |

| Muslce stiffness |

0.111 | -0.175 | -0.116 | -0.071 | -0.126 | 0.304 | -0.039 | -0.120 | 0.298 | 0.935** | 1 |

| Variables | CSI-K | MARM; average | MARM; area | MIP | MEP | SEBQ | NPRS; usual pain | NPRS; worst pain | K-PCS | Muscle tone |

Muscle stiffness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSI-K | 1 | ||||||||||

| MARM; average |

0.202 | 1 | |||||||||

| MARM; area |

0.005 | 0.303 | 1 | ||||||||

| MIP | 0.217 | 0.215 | 0.179 | 1 | |||||||

| MEP | -0.117 | 0.125 | 0.147 | 0.674** | 1 | ||||||

| SEBQ | 0.187 | -0.259 | -0.277 | -0.342 | -0.435* | 1 | |||||

| NPRS; usual pain | 0.099 | -0.050 | -0.486** | -0.007 | -0.089 | 0.342 | 1 | ||||

| NPRS; worst pain | 0.281 | -0.180 | -0.423* | 0.001 | -0.162 | 0.168 | 0.772** | 1 | |||

| K-PCS | 0.201 | -0.155 | -0.605** | -0.299 | -0.385* | 0.595** | 0.570** | 0.436* | 1 | ||

| Muscle tone |

0.120 | -0.311 | -0.069 | -0.172 | -0.089 | 0.197 | -0.059 | -0.142 | 0.172 | 1 | |

| Muslce stiffness |

0.209 | -0.356* | -0.180 | -0.143 | -0.142 | 0.304 | -0.013 | -0.080 | 0.272 | 0.970** | 1 |

| Variables | CSI-K | MARM; average | MARM; area | MIP | MEP | SEBQ | NPRS; usual pain | NPRS; worst pain | K-PCS | Muscle tone |

Muscle stiffness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSI-K | 1 | ||||||||||

| MARM; average |

-0.060 | 1 | |||||||||

| MARM; area |

-0.164 | 0.524* | 1 | ||||||||

| MIP | -0.408 | 0.032 | 0.397 | 1 | |||||||

| MEP | -0.422 | 0.021 | 0.541* | 0.825** | 1 | ||||||

| SEBQ | 0.719** | 0.181 | -0.051 | -0.515* | -0.468 | 1 | |||||

| NPRS; usual pain | 0.232 | -0.220 | -0.035 | -0.318 | -0.307 | 0.181 | 1 | ||||

| NPRS; worst pain | 0.072 | -0.267 | -0.317 | -0.278 | -0.443 | 0.013 | 0.600* | 1 | |||

| K-PCS | 0.667** | 0.247 | -0.298 | -0.419 | -0.555* | 0.642** | 0.209 | 0.236 | 1 | ||

| Muscle tone |

0.388 | 0.102 | 0.260 | -0.156 | 0.035 | 0.305 | 0.134 | -0.120 | 0.441 | 1 | |

| Muslce stiffness |

0.546* | 0.046 | 0.120 | -0.243 | -0.106 | 0.446 | 0.212 | -0.027 | 0.594* | 0.967** | 1 |

| Dependent variable |

Independent variable |

Unstandardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients |

t (p) | F | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | |||||

| Simple regression analysis between respiratory variables: CSI-K (≥ 40 points) (n = 40) | |||||||

| MARM; area | (constant) | 49.064 | 4.817 | 10.186 (0.000) | 8.957** | 0.191 | |

| K-PCS | -0.686 | 0.229 | -0.437 | -2.992 (0.005) | |||

| MIP | (constant) | -20.838 | 18.342 | -1.136 (0.263) | 25.421** | 0.633 | |

| MEP | 1.209 | 0.240 | 0.633 | 5.042 (0.000) | |||

| MEP | (constant) | 83.188 | 3.653 | 22.772 (0.000) | 7.058* | 0.157 | |

| SEBQ | -0.407 | 0.153 | -0.396 | -2.657 (0.011) | |||

| Simple regression analysis between pain variables: CSI-K (≥ 40 points) (n = 40) | |||||||

| NPRS; usual pain | (constant) | -1.161 | 0.604 | -1.922 (0.062) | 55.491** | 0.594 | |

| NPRS; worst pain | 0.824 | 0.111 | 0.770 | 7.449 (0.000) | |||

| NPRS; usual pain | (constant) | 2.182 | 0.380 | 5.741 (0.000) | 12.729** | 0.237 | |

| K-PCS | 0.061 | 0.017 | 0.487 | 3.568 (0.004) | |||

| NPRS; worst pain | (constant) | 4.472 | 0.382 | 11.702 (0.000) | 6.324** | 0.143 | |

| K-PCS | 0.046 | 0.018 | 0.378 | 2.515 (0.016) | |||

| Simple regression analysis between other variables: CSI-K (≥ 40 points) (n = 40) | |||||||

| MARM; area | (constant) | 49.064 | 4.817 | 10.186 (0.000) | 8.957** | 0.191 | |

| K-PCS | -0.686 | 0.229 | -0.437 | -2.992 (0.005) | |||

| SEBQ | (constant) | 11.219 | 2.878 | 3.899 (0.000) | 14.699** | 0.279 | |

| K-PCS | 0.525 | 0.137 | 0.528 | 3.834 (0.000) | |||

| Muscle Tone | (constant) | 6.967 | 0.618 | 11.271 (0.000) | 264.823** | 0.875 | |

| Muscle Stiffness | 0.029 | 0.002 | 0.935 | 16.273 (0.000) | |||

| Subanalysis; simple regression analysis between variables: MARM; average (≥ 100 degrees) (n = 33) | |||||||

| MARM; area | (constant) | 59.948 | 5.977 | 10.030 (0.000) | 9.607** | 0.237 | |

| NPRS; usual pain | -5.056 | 1.631 | -0.486 | -3.099 (0.004) | |||

| (constant) | 68.348 | 9.898 | 6.905 (0.000) | 6.773* | 0.179 | ||

| NPRS; worst pain | -4.618 | 1.774 | -0.423 | -2.603 (0.014) | |||

| (constant) | 56.852 | 4.093 | 13.891 (0.000) | 17.857** | 0.366 | ||

| K-PCS | -0.806 | 0.191 | -0.605 | -4.226 (0.000) | |||

| MEP | (constant) | 81.968 | 3.627 | 22.600 (0.000) | 5.402** | 0.148 | |

| K-PCS | -0.393 | 0.169 | -0.385 | -2.324 (0.027) | |||

| SEBQ | (constant) | 10.599 | 3.160 | 3.354 (0.002) | 17.024** | 0.354 | |

| K-PCS | 0.608 | 0.147 | 0.595 | 4.126 (0.000) | |||

| Muscle Tone | (constant) | 6.418 | 0.480 | 13.362 (0.000) | 493.335** | 0.941 | |

| Muscle Stiffness | 0.031 | 0.001 | 0.970 | 22.211 (0.000) | |||

| Muscle Stiffness | (constant) | 707.909 | 174.285 | 4.062 (0.000) | 17.024** | 0.354 | |

| MARM; average | -3.206 | 1.513 | -0.356 | -2.119 (0.042) | |||

| Subanalysis; Simple regression analysis between respiratory variables: NPRS; usual pain (≥ 4 points) (n = 17) | |||||||

| MARM; area | (constant) | -9.989 | 17.290 | -0.578 (0.572) | 6.220** | 0.246 | |

| MEP | 0.572 | 0.229 | 0.541 | 2.494 (0.025) | |||

| MIP | (constant) | 84.648 | 8.850 | 9.565 (0.000) | 5.402* | 0.265 | |

| SEBQ | -0.691 | 0.297 | -0.515 | -2.324(0.035) | |||

| Subanalysis; Simple regression analysis between other variables: NPRS; usual pain (≥ 4 points) (n = 17) | |||||||

| Muscle Tone | (constant) | 6.629 | 0.681 | 9.739 (0.000) | 215.724** | 0.935 | |

| Muscle Stiffness | 0.030 | 0.002 | 0.967 | 3.242 (0.000) | |||

| Muscle Stiffness | (constant) | 268.996 | 24.868 | 10.817 (0.000) | 8.199* | 0.353 | |

| K-PCS | 2.616 | 0.914 | 0.594 | 2.863 (0.012) | |||

| CSI-K | (constant) | 42.098 | 2.020 | 20.837 (0.000) | 16.096** | 0.518 | |

| SEBQ | 0.272 | 0.068 | 0.719 | 4.012 (0.001) | |||

| (constant) | 41.780 | 2.353 | 17.753 (0.000) | 12.030** | 0.445 | ||

| K-PCS | 0.300 | 0.086 | 0.667 | 3.468 (0.003) | |||

| (constant) | 30.283 | 7.404 | 4.090 (0.001) | 6.361* | 0.298 | ||

| Muscle Stiffness | 0.056 | 0.022 | 0.546 | 2.522 (0.023) | |||

| Dependent variable |

Independent variable |

Unstandardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients |

t (p) | F | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | β | |||||

| Multiple regression analysis between variables: CSI-K (≥ 40 points) (n = 40) | |||||||

| MARM; area | (constant) | -75.530 | 24.717 | -3.056 (0.004) | 20.428* | 0.525 | |

| MARM; average | 1.116 | 0.219 | 0.578 | 5.100 (0.000) | |||

| K-PCS | -0.651 | 0.178 | -0.415 | -3.658 (0.001) | |||

| K-PCS | (constant) | 15.522 | 24.717 | 3.381 (0.002) | 20.428* | 0.525 | |

| MARM; area | -0.235 | 0.081 | -0.369 | -2.898 (0.006) | |||

| SEBQ | 0.479 | 0.128 | 0.476 | 3.735 (0.001) | |||

| Subanalysis; Multiple regression analysis between variables: MARM; average (≥ 100 degrees) (n = 33) | |||||||

| NPRS; usual pain | (constant) | -1.012 | 0.621 | -1.629 (0.114) | 29.624* | 0.664 | |

| NPRS; worst pain | 0.678 | 0.123 | 0.647 | 5.498 (0.000) | |||

| K-PCS | 0.037 | 0.015 | 0.288 | 2.452 (0.020) | |||

| K-PCS | (constant) | 22.527 | 5.657 | 3.982 (0.000) | 19.388* | 0.564 | |

| MARM; area | -0.357 | 0.094 | -0.476 | -3.794 (0.001) | |||

| SEBQ | 0.454 | 0.123 | 0.463 | 3.693 (0.001) | |||

| Sub-analysis; Multiple regression analysis between variables: NPRS; usual pain (≥ 4 points) (n = 17) | |||||||

| MARM; area | (constant) | -95.780 | 33.026 | -2.900 (0.012) | 8.756* | 0.556 | |

| MARM; average | 0.779 | 0.271 | 0.513 | 2.877 (0.012) | |||

| MEP | 0.560 | 0.188 | 0.531 | 2.978 (0.010) | |||

| Muscle Stiffness | (constant) | -201.736 | 29.960 | -6.734 (0.000) | 195.627* | 0.978 | |

| CSI-K | 1.210 | 0.542 | 0.124 | 2.233 (0.044) | |||

| K-PCS | 0.583 | 0.250 | 0.132 | 2.329 (0.037) | |||

| Muscle Tone | 27.883 | 1.489 | 0.861 | 18.731 (0.000) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).