1. Introduction

Host plants have evolved disease resistance strategies to resist pathogens during their interaction. Sheath blight (ShB) in rice, caused by Rhizoctonia solani, is the one of the most important diseases in rice, which can cause up to 50% yield loss (Chen et al., 2016). Previous studies revealed that the resistance against ShB is controlled by multiple genes. At present, some of the quantitative trait locus (QTL)–linked genes have been cloned and functionally verified (Pinson et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2021). Phytohormone signals play an important role in the process of resistance of rice to ShB. Jasmonic acid (JA), salicylic acid (SA), and auxin signals regulate the resistance of rice to ShB (Kouzai et al., 2018; Qiao et al., 2020). Our previous study confirmed that ethylene and brassinosteroid (BR) signals positively and negatively regulate resistance of rice to ShB, respectively (Yuan et al., 2018). WRKY transcription factors (TFs) are widely involved in the resistance of rice to ShB (Peng et al., 2016). OsWRKY53 negatively regulates ShB resistance by activating SWEET2a (Gao et al., 2021). A recent study reported that the effector protein AOS2 from R. solani interacts with the rice TFs OsWRKY53 and OsGT1 and forms a TF complex to activate the expression of OsSWEET2a and OsSWEET3a, thereby promoting the pathogenesis of ShB (Yang et al., 2023).

The results of genome-wide association study revealed that the natural variation of ZmFBL41 in maize affected the interaction between ZmFBL41 and ZmCAD, further affecting the host resistance (Li et al., 2019). Our previous study confirmed that OsLPA1 overexpression improves the resistance of rice to ShB (Sun et al., 2019a). Further study reported that OsLPA1 regulates the resistance of rice to ShB through interaction with OsKLP (Chu et al., 2021). OsPhyB and OsLAZY1 negatively regulate the resistance of rice to ShB (Sun et al., 2019b). OsDEP1 interacts with OsLPA1 and inhibits the transcriptional activation of OsLPA1 downstream genes, thereby inhibiting the resistance of rice to ShB (Miao Liu et al., 2021). In addition, the protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit (PP2A-1) positively regulates the resistance of rice to ShB (Lin et al., 2021).

The interaction between plant pathogens and hosts is a complex and prolonged process. Extensive breeding practices have proven that improving host disease resistance often reduces crop yield, which is a trade-off between plant development and disease resistance (He et al., 2022; Ning et al., 2017). Therefore, effective disease prevention and control, particularly exploring important genes that can simultaneously increase yield and disease resistance, is of great significance for ensuring national food security. The SA and JA pathways typically interact in an antagonistic manner and interact with the pathways of other plant hormones such as abscisic acid (ABA), gibberellic acid (GA), BR, and auxin to jointly regulate the trade-off between growth and immunity (Denancé et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2007). TFs are important factors that balance plant growth and immunity (Wang and Wang, 2014). BZR1 blocks PTI signaling by interacting with different WRKYs or via transcriptional regulation with different WRKYs in Arabidopsis (Ning et al., 2017). Our previous study reported that PIL15 negatively regulates rice resistance to sheath blight. (Yuan et al., 2023). In addition, PIL15 activated miR530, a negative regulator of grain size to negatively regulate grain size (Sun et al., 2020). The immune receptor NLR and cell-wall-associated kinase (WAK) play a dual role in balancing immunity and production. The two NLR genes at the Pigm locus not only confer resistance to Aspergillus oryzae but also increase yield (Deng et al., 2017). Xa4 encodes a WAK and confers race-specific persistent resistance to Xoo without losing production potential (Hu et al., 2017).

SWEET is a family of sugar transporters. It has the function of bidirectional transport of sugar substances (Yuan and Wang, 2013) and is involved in regulating plant–pathogen interactions (Bezrutczyk et al., 2018). Most studies have reported that activating the expression of the SWEETs is beneficial for pathogenic bacteria to hijack carbohydrate nutrients from plants to promote their growth (Jeena et al., 2019; Yuan and Wang, 2013). In addition, some studies have reported that inhibiting the expression of SWEET can reduce the sugar content in the extracellular space and inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria (Kim et al., 2021). OsSWEET11/Xa13/Os8N3, OsSWEET13/Xa25, and OsSWEET14/Os11N3 are important genes in rice regulating resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae(Li et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2011).

Our previous study reported that OsSWEET11 is significantly induced by R. solani infection, and sweet11 mutants are less susceptible to ShB (Gao et al., 2018). However, in sweet11 mutants, the sucrose concentration in the embryo sacs significantly decreased and led to defective grain filling, which resulted in significantly lower 100-grain weight in sweet11 mutants than in wild-type plants (Ma et al., 2017). In addition, we previously demonstrated Rubisco promoter expressing sucrose transport activity defected SWEET11 mutant protein increased ShB resistance and maintained normal grain filling (Gao et al., 2018). Tissue specific activation of DOF11 promoted rice resistance to ShB via activation of SWEET14 without yield loss (Kim et al., 2021). This suggested that tissue-specific regulation of SWEETs expression might achieve the goal of improvement in ShB resistance without developmental defect in rice. Numerous studies have reported that WRKY TFs are widely involved in the resistance of rice to ShB (Gao et al., 2021; John Lilly and Subramanian, 2019). In addition, our previous study reported that PIL15 repressors and overexpressors were less and more susceptible to ShB, respectively (Yuan et al., 2023). However, the regulation of SWEETs by TFs to modulate plant defense has not been studied in detail.

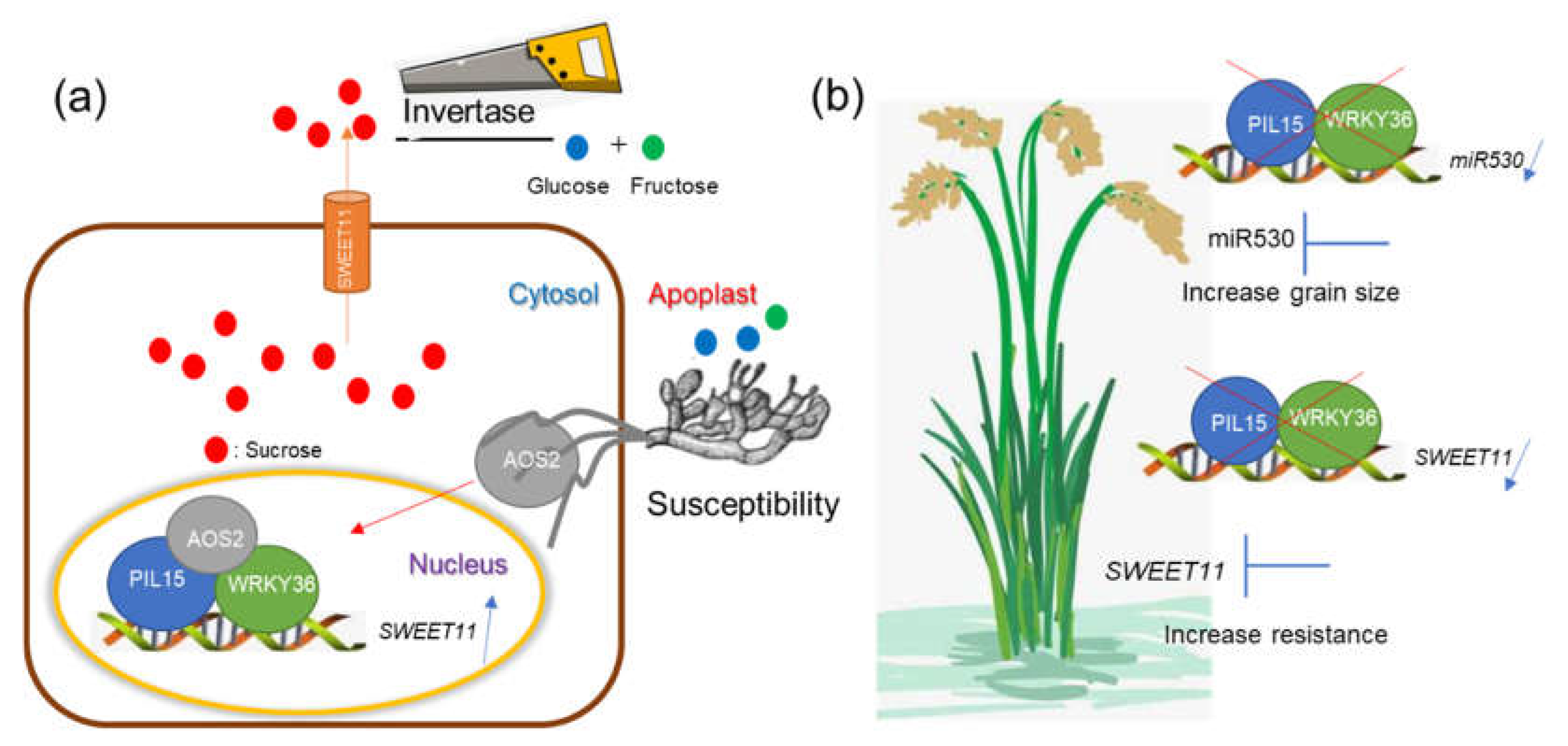

In this study, we observed that the WRKY36 and PIL15 activate SWEET11. Further, WRKY36 interacted with PIL15 to activate SWEET11, which negatively regulated rice resistance to ShB. In addition, WRKY36–PIL15 activated miR530 to negatively regulate grain size. R. solani effector protein AOS2 interacted with WRKY36 and PIL15 to activate SWEET11 for sugar efflux, via which R. solani activated SWEET11 expression as well as subsequent sugar efflux. Our study revealed the mechanism by which R. solani activated SWEET11 for sugar efflux and identified WRKY36 and PIL15 as the potential molecular targets in ShB resistant breeding.

2. Results

2.1. WRKY36 and PIL15 Negatively Regulates Resistance of Rice to ShB

To isolate transcription factor which might tissue specifically regulates

SWEET11, the yeast-one hybrid screening was performed using 2.0 kb of

SWEET11 promoter as the bait. The results identified 15 putative transcriptional regulators including WRKY36 and PIL15. Previously, WRKYs and PIL15 were reported to regulate rice ShB resistance (Peng et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2023); therefore, WRKY36 and PIL15 were further analyzed their regulation on

SWEET11 transcription. The

R. solani-dependent expression patterns revealed that

PIL15 were significantly induced, whereas

WRKY36 expression had no significant difference by

R. solani infection (

Figure S1). Therefore, the functions of

WRKY36 and

PIL15 in resistance of rice to ShB were further investigated. Via genome-editing,

wrky36 and

pil15 mutants were generated.

wrky36-10 and

wrky36-11 mutants have 1-bp insertion and 4-bp deletion at the 1

st exon, respectively (

Figure 1a). After

R. solani inoculation,

wrky36 mutants were less susceptible to ShB than the wild-type plants (

Figure 1b, c).

pil15-13 and

pil15-14 mutants have 3-bp deletion and 1-bp insertion at the 2

st exon, respectively (

Figure 1d). After

R. solani inoculation,

pil15 mutants were less susceptible to ShB than the wild-type plants (

Figure 1e, f).

Since

wrky36 and

pil15 mutants were less susceptible to ShB, the mechanisms of

WRKY36 and

PIL15 in ShB resistance were further examined. To further evaluate the defense mechanism, plants overexpressing

WRKY36 and

PIL15 were tested.

WRKY36 expression level was clearly higher in

WRKY36 OX 1 and

OX 2 than in wild-type plants (

Figure 1g). After

R. solani inoculation,

WRKY36 OX plants were more susceptible to ShB than the wild-type plants (

Figure 1h, i).

PIL15 expression level was clearly higher in

PIL15 eGFP OX 5 and

OX 10 than in wild-type plants (

Figure 1j). After

R. solani inoculation,

PIL15 eGFP OX plants were more susceptible to ShB than the wild-type plants (

Figure 1k, l). Similarly, the

PIL15 overexpression (

PIL15 OX) and repressor (

PIL15 RD) lines were examined (Xie et al., 2019).

PIL15 RDs were less susceptible to ShB than the wild-type plants, whereas

PIL15 OXs were more susceptible to ShB than the wild-type plants (

Figure 1m, n).

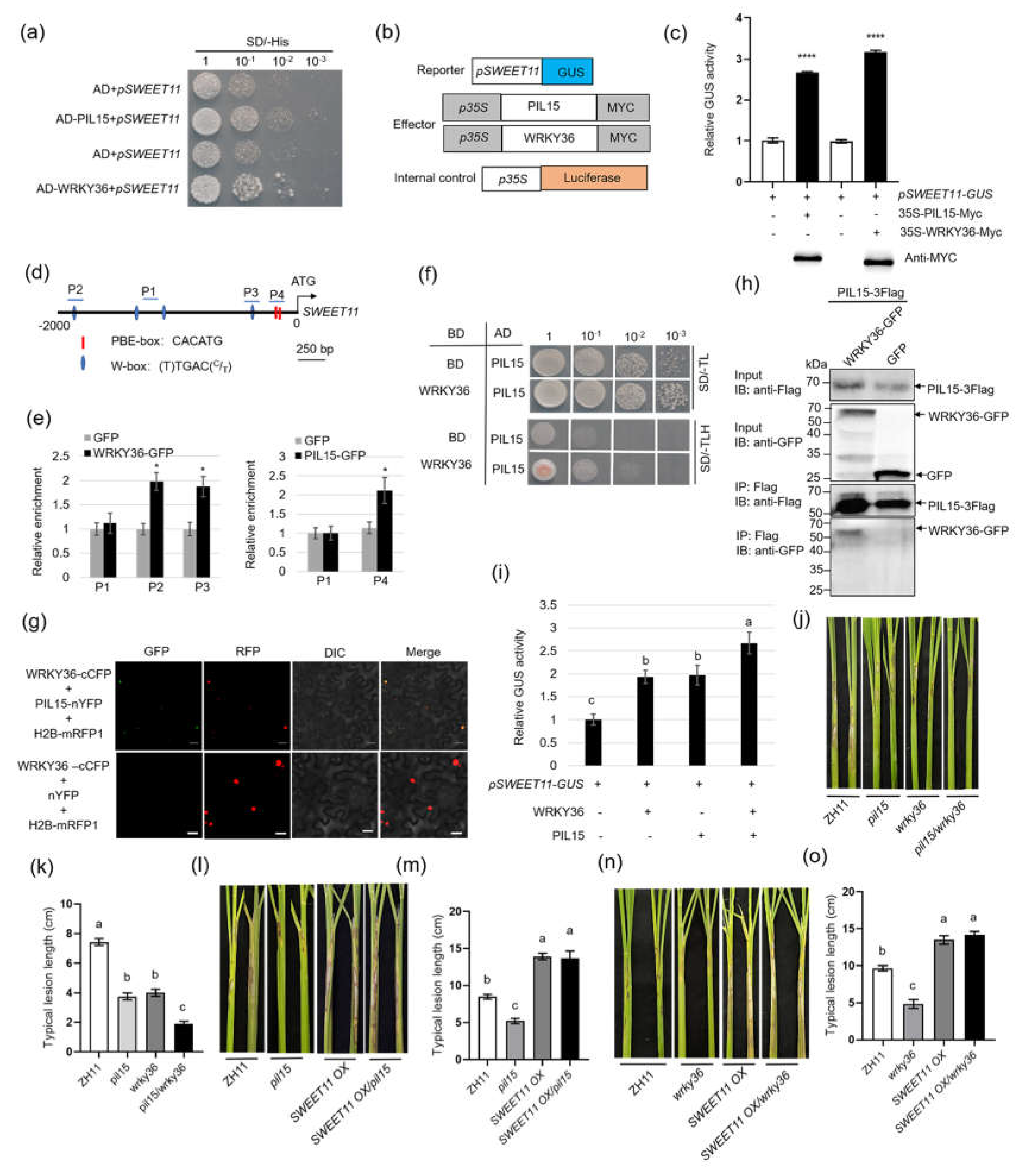

2.2. WRKY36 Interacts with PIL15 to Activate SWEET11

Yeast-one hybrid (Y1H) assay results revealed that WRKY36 or PIL15 activates 2.0-kb

SWEET11 promoter (

Figure 2a). To verify the Y1H assay results, a transient assay was performed in rice protoplast cells. The results revealed that the coexpression of WRK36-Myc or PIL15-Myc with 2.0 kb of

pSWEET11-GUS significantly activated

GUS expression level than the expression of

pSWEET11-GUS alone. Western blot analysis was performed to detect successful expression of WRK36-Myc or PIL15-Myc in the rice protoplast using anti-Myc antibody (

Figure 2b, c). Further, the

SWEET11 promoter sequences were analyzed. The results indicated that

SWEET11 promoter region contains (T)TGAC(

C/

T) W-box (WRKY-binding) and (CACATG) PBE-box (PIL-binding) motifs (

Figure 2d). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay using WRKY36-GFP and PIL15-GFP plant calli as well as anti-GFP antibody revealed that WRKY36 bound to P2 and P3 region harboring W-box motif, whereas PIL15 bound to P4 with the enrichment of PBE-box motifs (

Figure 2e).

Since both WRKY36 and PIL15 activate

SWEET11, the interaction between WRKY36 and PIL15 was investigated. Yeast-two hybrid (Y2H) assay revealed that WRKY36 interacts with PIL15 (

Figure 2f). Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay with WRKY36 and PIL15 expression in

Nicotiana benthamiana leaves revealed that WRKY36 interacts with PIL15 in the nucleus (

Figure 2g). Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay was performed by coexpressing WRKY36-GFP and PIL15-3xFlag or GFP and PIL15-3xFlag. Subsequent immunoprecipitation via anti-Flag antibody as well as western blot analysis indicated that WRKY36-GFP interacts with PIL15-3xFlag (

Figure 2h).

Furthermore, the function of WRKY36–PIL15 in

SWEET11 activation was analyzed. The transient assay results revealed that WRKY36 or PIL15 expression activated

pSWEET11, whereas coexpression of WRKY36 and PIL15 exhibited a stronger transcription activation activity than the expression of WRKY36 or PIL15 alone (

Figure 2i). Further,

wrky36/pil15 double mutants and

SWEET11 OX/pil15 or

SWEET11 OX/wrky36 plants were generated. After

R. solani inoculation,

pil15 and wrky36 single mutant were less and more susceptible to diseases than wile-type and

wrky36/pil15 double mutants, respectively (

Figure 2j, k). Inoculation of

R. solani showed that

SWEET11 OX and

SWEET11 OX/pil15 plants exhibited similar lesion length, and

SWEET11 OX and

SWEET11 OX/pil15 plants were more susceptible than

pil15 (

Figure 2l, m). Similarly, inoculation of

R. solani identified that

SWEET11 OX and

SWEET11 OX/wrky36 plants developed similar lesion length, and

SWEET11 OX and

SWEET11 OX/wrky36 plants were more susceptible than

wrky36 (

Figure 2n, o). In addition, the expression levels of

SWEET11 in

wrky36/pil15 double mutants and

SWEET11 OX/pil15 or

SWEET11 OX/wrky36 leaf sheaths were also detected. The results showed that the expression level of

SWEET11 in

pil15 and wrky36 single mutant were lower than that in the wild type and higher than that in

wrky36/pil15 double mutants (

Figure S2a).

The expression levels of

SWEET11 in

SWEET11 OX and

SWEET11 OX/pil15 leaf sheaths were similar, and

SWEET11 OX and

SWEET11 OX/pil15 plants were higher than

pil15 and wild-type plants (

Figure S2b). Similarly, the expression levels of

SWEET11 in

SWEET11 OX and

SWEET11 OX/wrky36 leaf sheaths were similar, and

SWEET11 OX and

SWEET11 OX/wrky36 plants were higher than

wrky36 and wild-type plants (

Figure S2c). Meanwhile, the expression levels of

SWEET11 in

PIL15 eGFP OX and

WRKY36 OX leaf sheaths were also detected. The results showed that the expression level of

SWEET11 in

PIL15 eGFP OX and

WRKY36 OX plants was higher than that in wild-type plants (

Figure S2d).

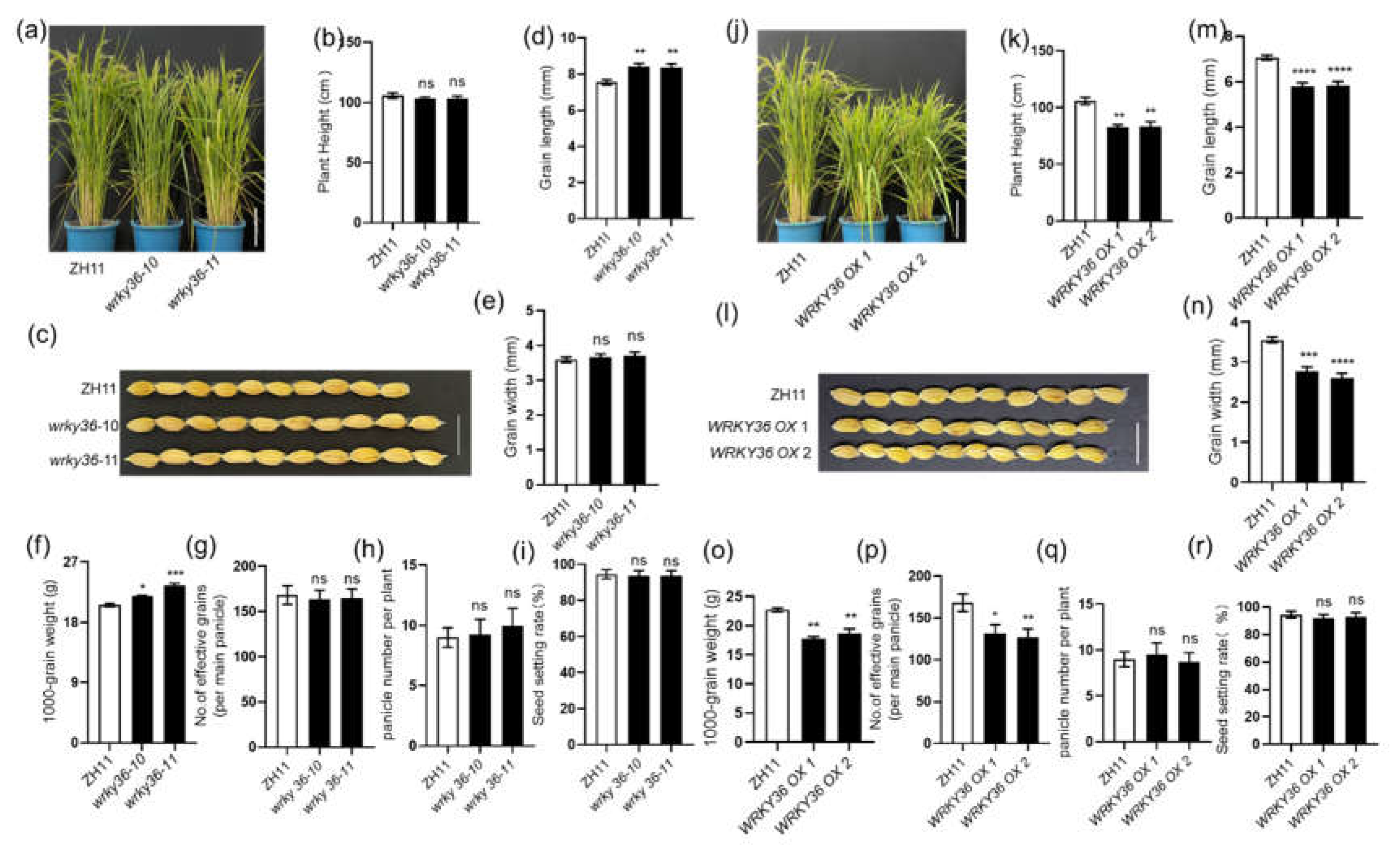

2.3. WRKY36 and PIL15 Negatively Regulate Seed Development

WRKY36–PIL15 activates

SWEET11 to regulate resistance of rice to ShB, and

sweet11 mutants exhibited defective seed development. Therefore, the seed development of

WRKY36 and

PIL15 mutants or overexpression plants was assessed. First, the plant height of

wrky36 mutants and wild-type plants was similar (

Figure 3a, b). Interestingly,

wrky36 mutants developed relatively longer seeds than wild-type plants (

Figure 3c, d); however, the width of seeds of

wrky36 mutants and wild-type plants were similar (

Figure 3e). Additionally, 1000-grain weight of

wrky36 mutants was higher than that of wild-type plants (

Figure 3f). However, there is no difference in the seed setting ration, panicle number per plant, and seed number per panicle between

wrky36 mutants and wild-type plants (

Figure 3g-i). The height of

WRKY36 OX plants was significantly shorter than that of wild-type plants (

Figure 3j, k).

WRKY36 OX plants developed smaller seeds than wild-type plants. The seed length of

WRKY36 OX plants was shorter, whereas the width was narrower than wild-type plants (

Figure 3l–n). This developmental feature resulted in lower 1000-grain weight in

WRKY36 OX than in wild-type plants (

Figure 3o).

WRKY36 OX plants have fewer seed number per panicle compared to wild-type plants (

Figure 3p). However, there is no difference in the seed setting ration and panicle number per plant between

WRKY36 OX and wild-type plants (

Figure 3q, r).

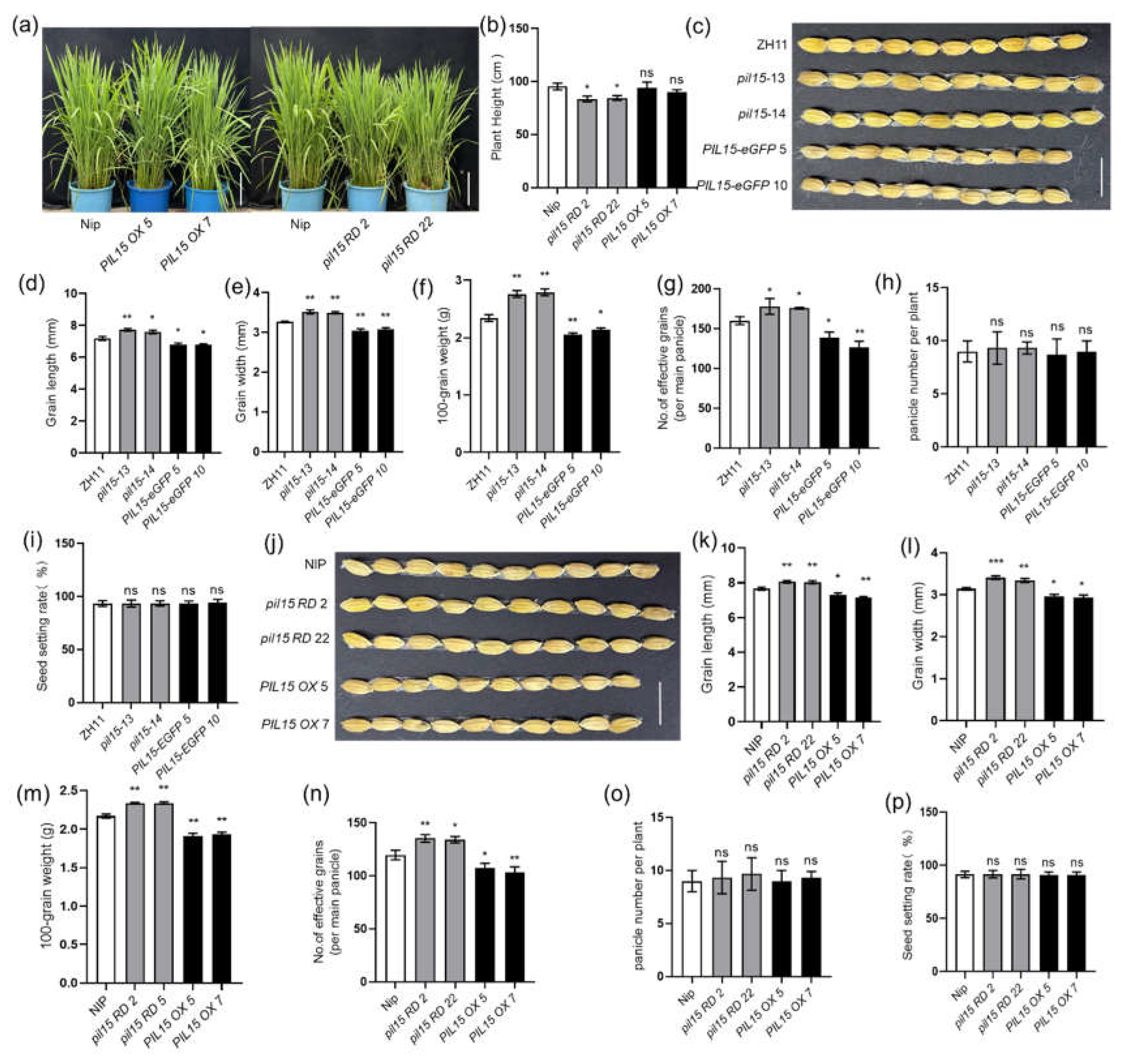

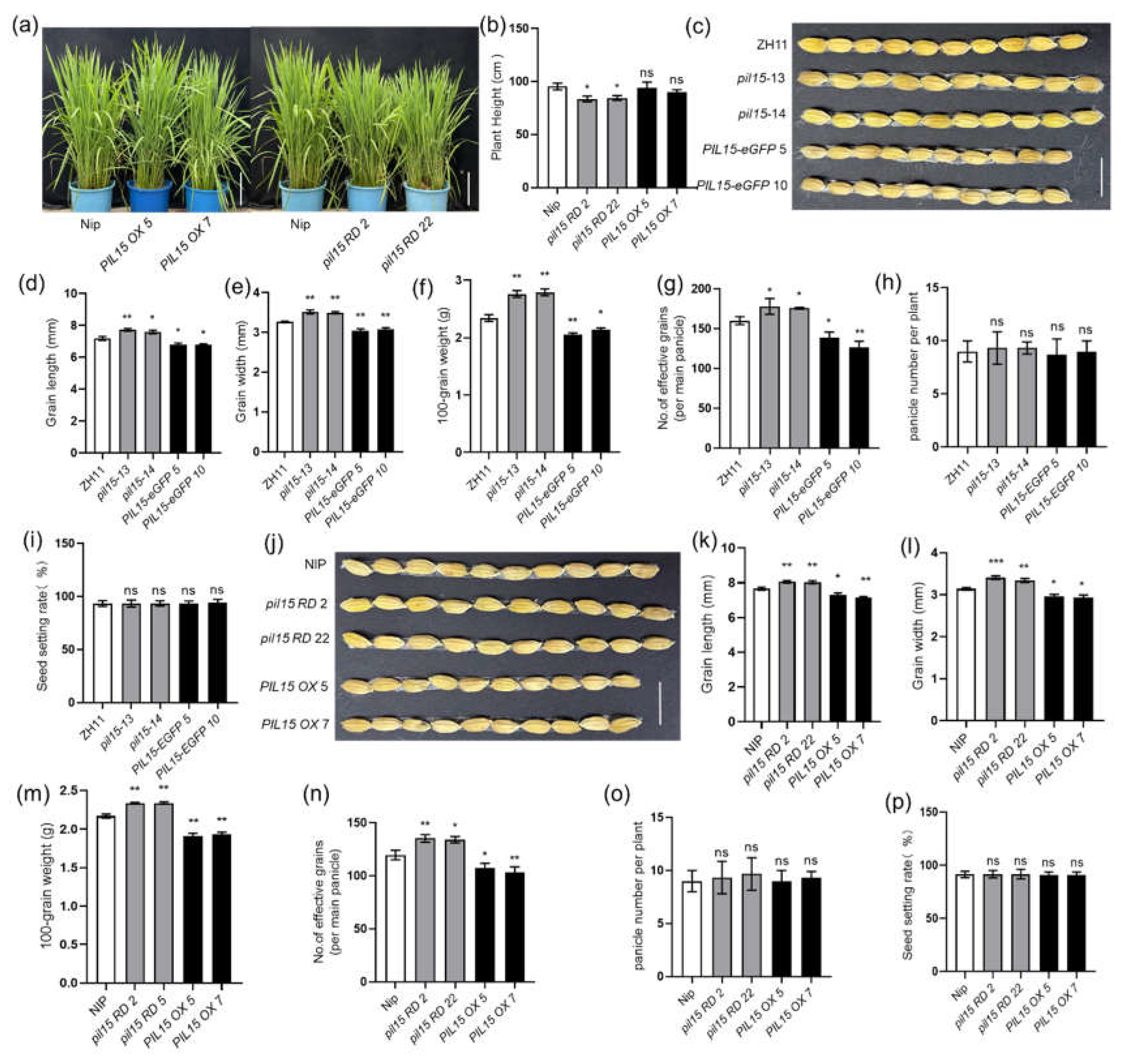

First, the plant height of

pil15 RD mutants,

PIL15 OX plants and wild-type plants was detected. (

Figure 4a, b).

pil15 RD mutants have a shorter plant height than the wild-type plants, while

PIL15 OX plants show no difference. Next, the function of

PIL15 in rice seed development was analyzed. The seed length and width of

pil15 mutants were relatively longer, whereas those of

PIL15 eGFP OX plants were relatively shorter than those of wild-type plants (

Figure 4c–e). These developmental differences resulted in higher 100-grain weight of

pil15 mutants and lower 100-grain weight of

PIL15 eGFP OX than that of wild-type plants (

Figure 4f). In addition, compared with the wild-type plants,

PIL15 eGFP OX plants have fewer seed number per panicle, while

pil15 mutants has more seed number per panicle (

Figure 4g). However, the seed setting ration and panicle number per plant of

pil15 mutants,

PIL15 eGFP OX and wild-type plants were similar (

Figure 4h, i). Similarly,

PIL15 OXs and

PIL15 RDs were examined.

PIL15 RDs developed larger seeds, whereas

PIL15 OXs developed smaller seeds than wild-type plants (

Figure 4j–l), and the 100-grain weight was higher in

PIL15 RDs but lower in

PIL15 OXs than in wild-type plants (

Figure 4m). In addition, compared with wild-type plants,

PIL15 OXs have fewer seed number per panicle, while

PIL15 RDs have more seed number per panicle (

Figure 4n). However, the seed setting ration and panicle number per plant of

pil15 RDs,

PIL15 OXs and wild-type plants was similar (

Figure 4o, p).

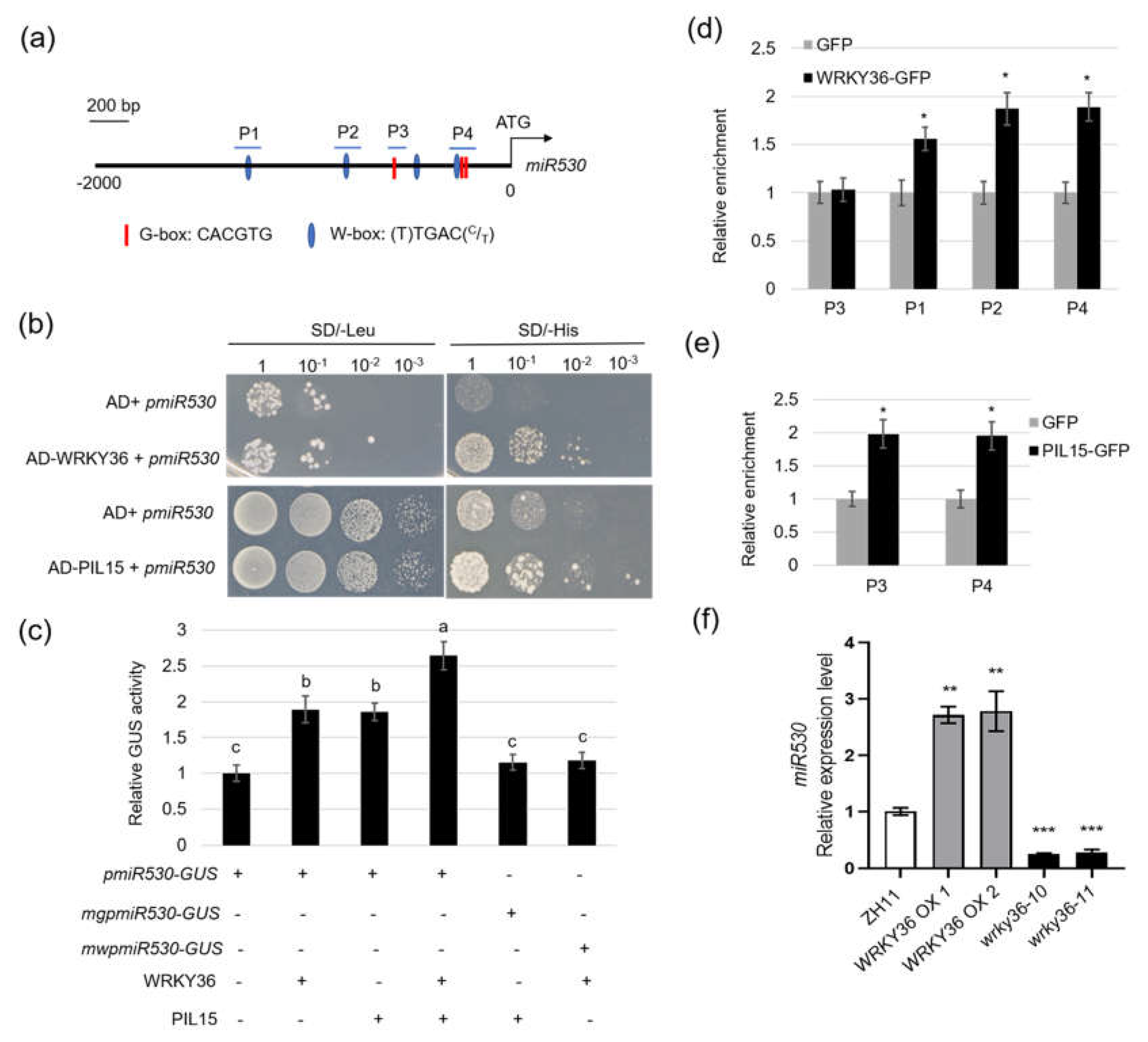

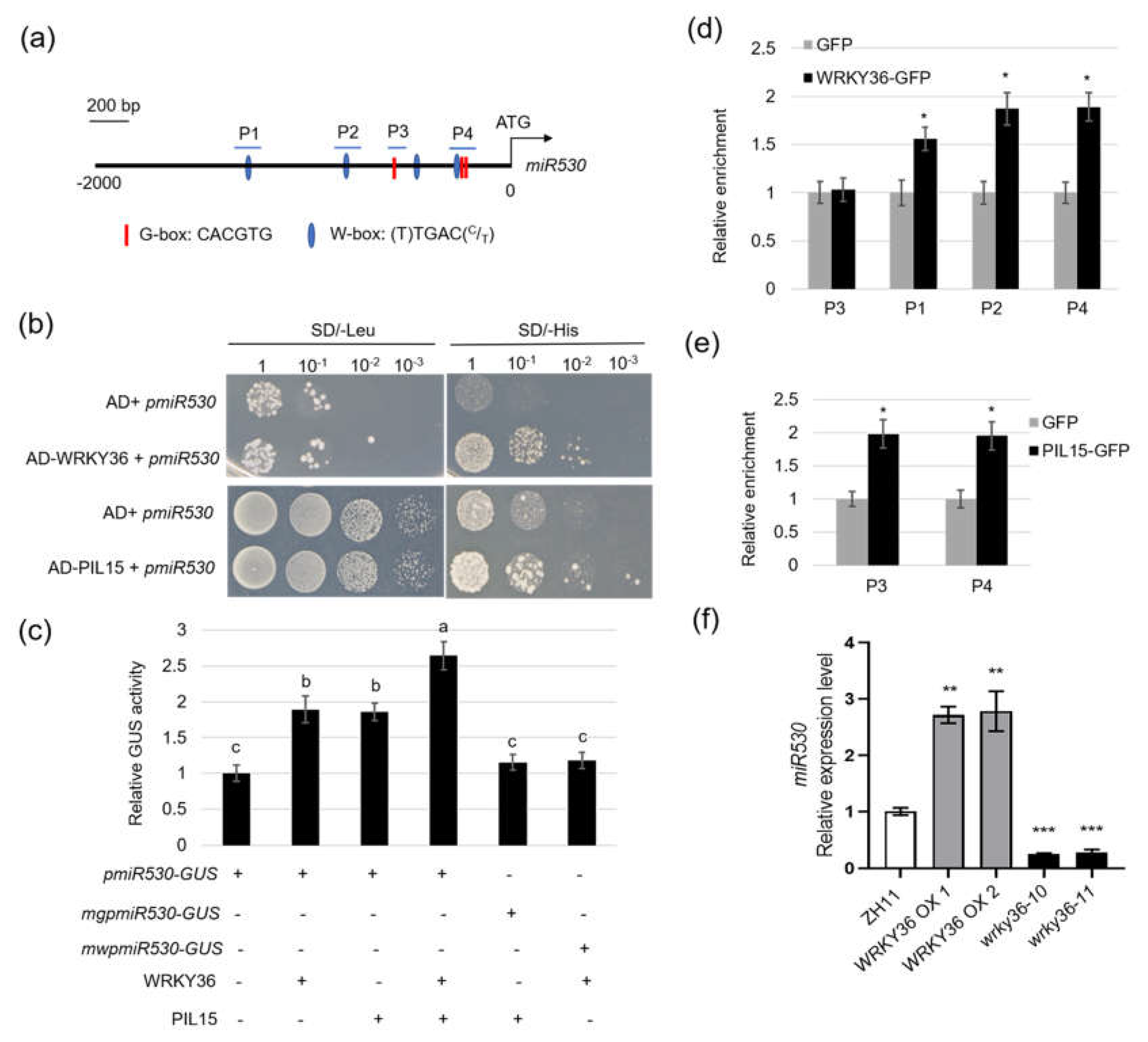

2.4. WRKY36–PIL15 Directly Activates miR530

WRKY36 and PIL15 activate

SWEET11 to regulate resistance of rice to ShB, and

sweet11 mutants exhibited defective seed development, the expression levels of

SWEET11 in the seeds of

WRKY36 and

PIL15 mutants were examined. The results showed that there was no difference in the expression level of

SWEET11 between

WRKY36 and

PIL15 mutants compared to wild-type plants (

Figure S3). It is proved that WRKY36 and PIL15 might regulate the expression of

SWEET11 in leaf sheaths, but not in the seeds. A previous study revealed that PIL15 activates

miR530 to negatively regulate grain size (Sun et al., 2020). To analyze whether WRKY36 also activates

miR530,

miR530 promoter sequences were analyzed. The W-box motif was observed within 2.0 kb of

miR530 promoter region (

Figure 5a). The Y1H assay results indicated that both WRKY36 and PIL15 activate

pmiR530 (

Figure 5b). To verify the results of Y1H assay, the transient assay was performed. In the protoplast cells, WRKY36 or PIL15 activated

pmiR530 but not W-box (

mwpmiR530)- or G-box (

mgpmiR530)-mutated

pmiR530. Additionally, coexpression of WRKY36 and PIL15 exhibited an additive effect on the activation of

pmiR530 (

Figure 5c). ChIP–PCR results further confirmed that WRKY36 and PIL15 bound to the

miR530 promoter (

Figure 5d, e). To analyze

miR530 expression levels in

wkry36 mutants and

WRKY36 OX plants, the

miR530 expression levels were assessed in the developing caryopsis of

wrky36 mutants,

WRKY36 OX, and wild-type plants. RT-qPCR results revealed that

miR530 expression level was significantly lower in

wrky36 mutants but higher in

WRKY36 OX plants than in wild-type plants (

Figure 5f).

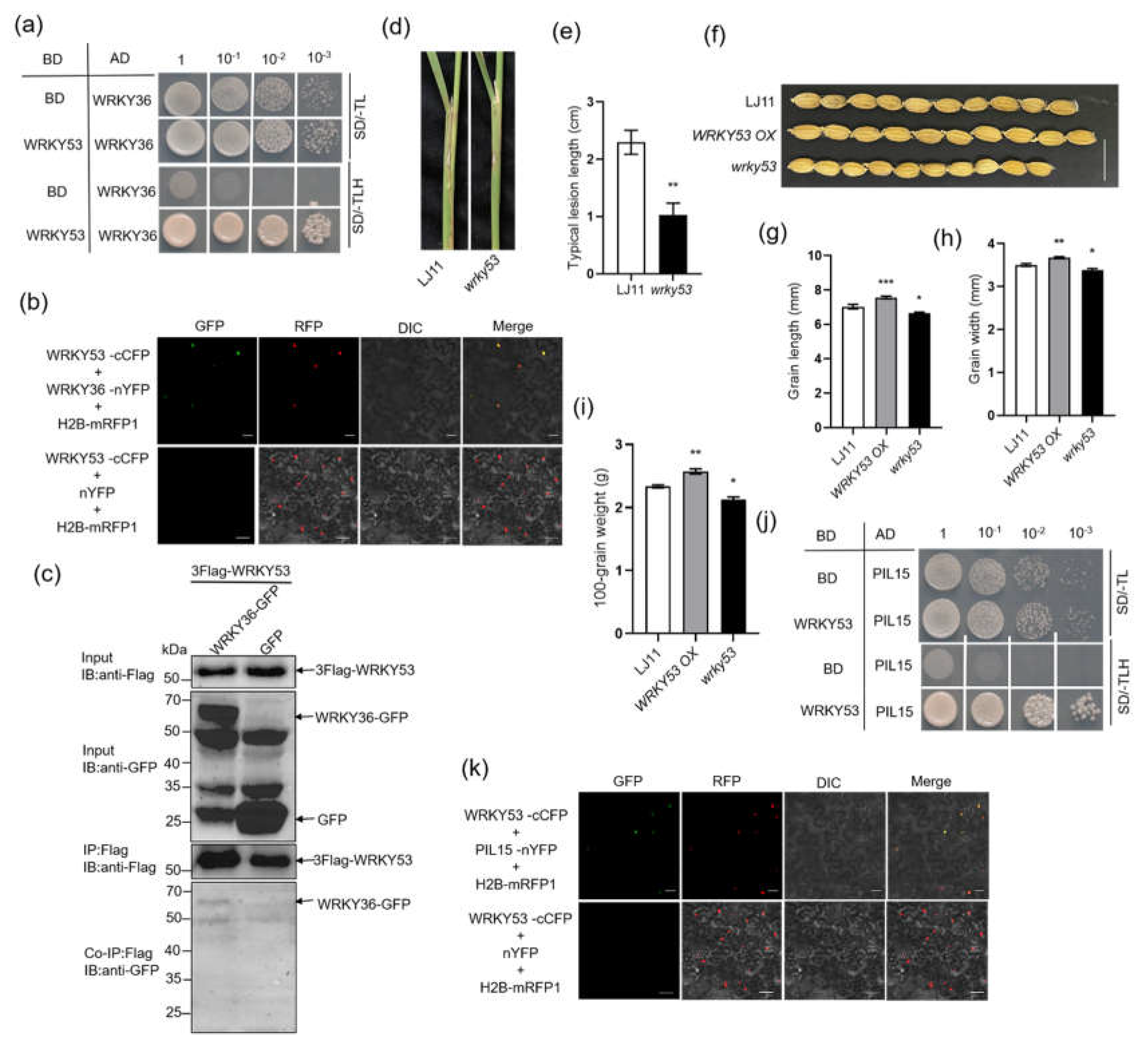

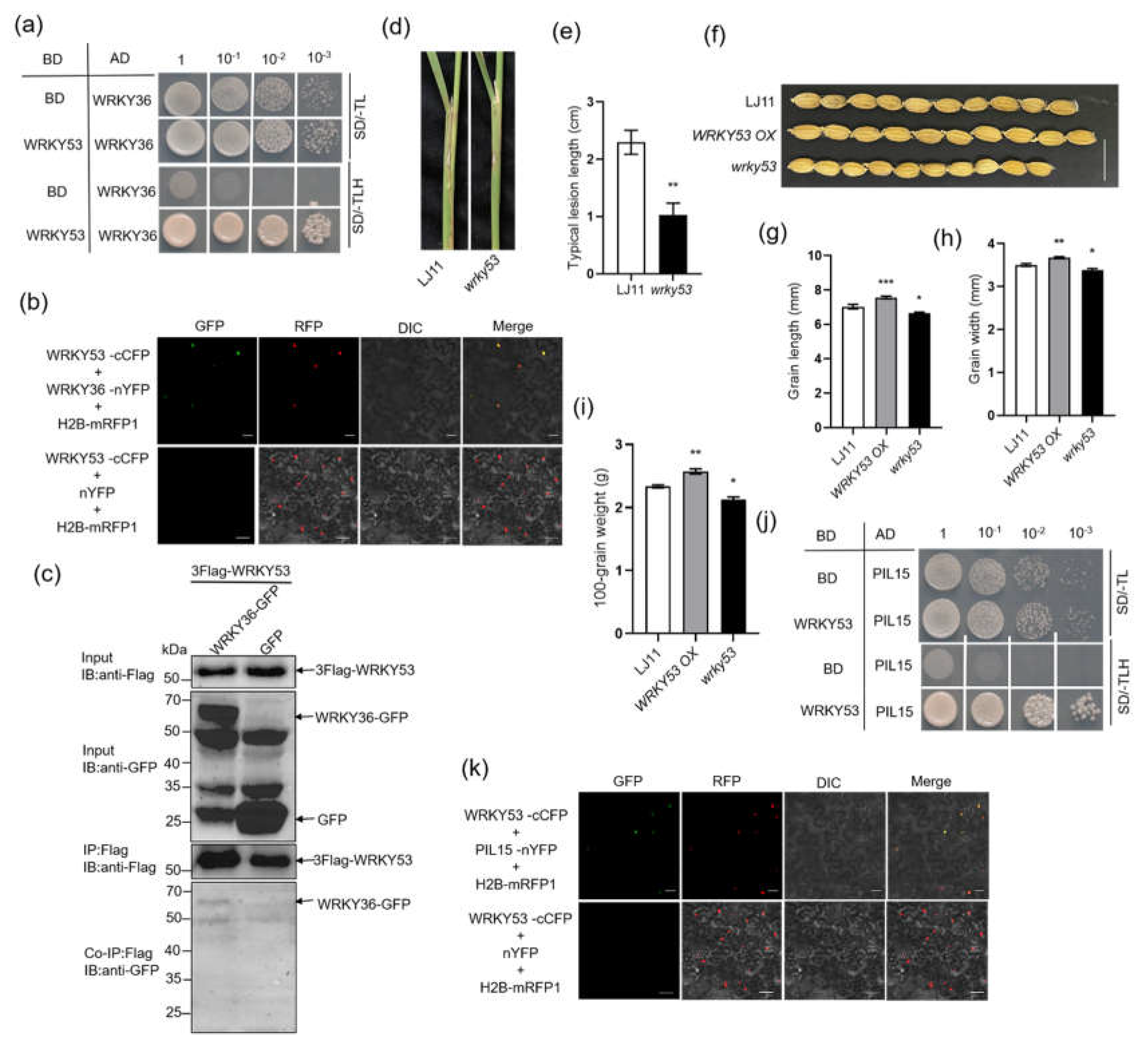

2.5. AOS2 Interacts with WRKY36 and PIL15 to Activate SWEET11

Plants overexpressing

WRKY36 exhibited enlarged lamina joint angle (

Figure 3g), a typical BR signaling phenotype in rice (Zhang et al., 2014). Further Y2H assay revealed that WRKY36 interacts with WRKY53 (

Figure 6a), the key BR signaling TF (Tian et al., 2021). BiFC assay results confirmed that WRKY36 and WRKY53 interact in the nucleus of tobacco cells (

Figure 6b). In addition, Co-IP assay results indicated that 3xFlag-WRKY53 interacts with WRKY36-GFP but not with GFP, indicating that WRKY36 interacts with WRKY53 (

Figure 6c). After

R. solani inoculation,

wrky53 mutants were less susceptible to the ShB than wild-type plants (

Figure 6d, e). However,

wrky53 mutant seeds were smaller, and

WRKY53 OX seeds were bigger than wild-type seeds, which was different from the results of

wrky36 mutants (

Figure 6f–i) (Tian et al., 2021). In addition, the interaction between PIL15 and WRKY53 was assessed. The results of Y2H assay revealed that WRKY53 interacts with PIL15 (

Figure 6j). BiFC results confirmed that WRKY53 interacts with PIL15 in the nucleus of tobacco cells (

Figure 6k). However, unlike WRKY36 and PIL15, WRKY53 did not directly activate

SWEET11 promoter (

Figure S4). The results indicated that WRKY53 might play a similar function as that of WRKY36 and PIL15 in the resistance of rice to ShB but not in grain development.

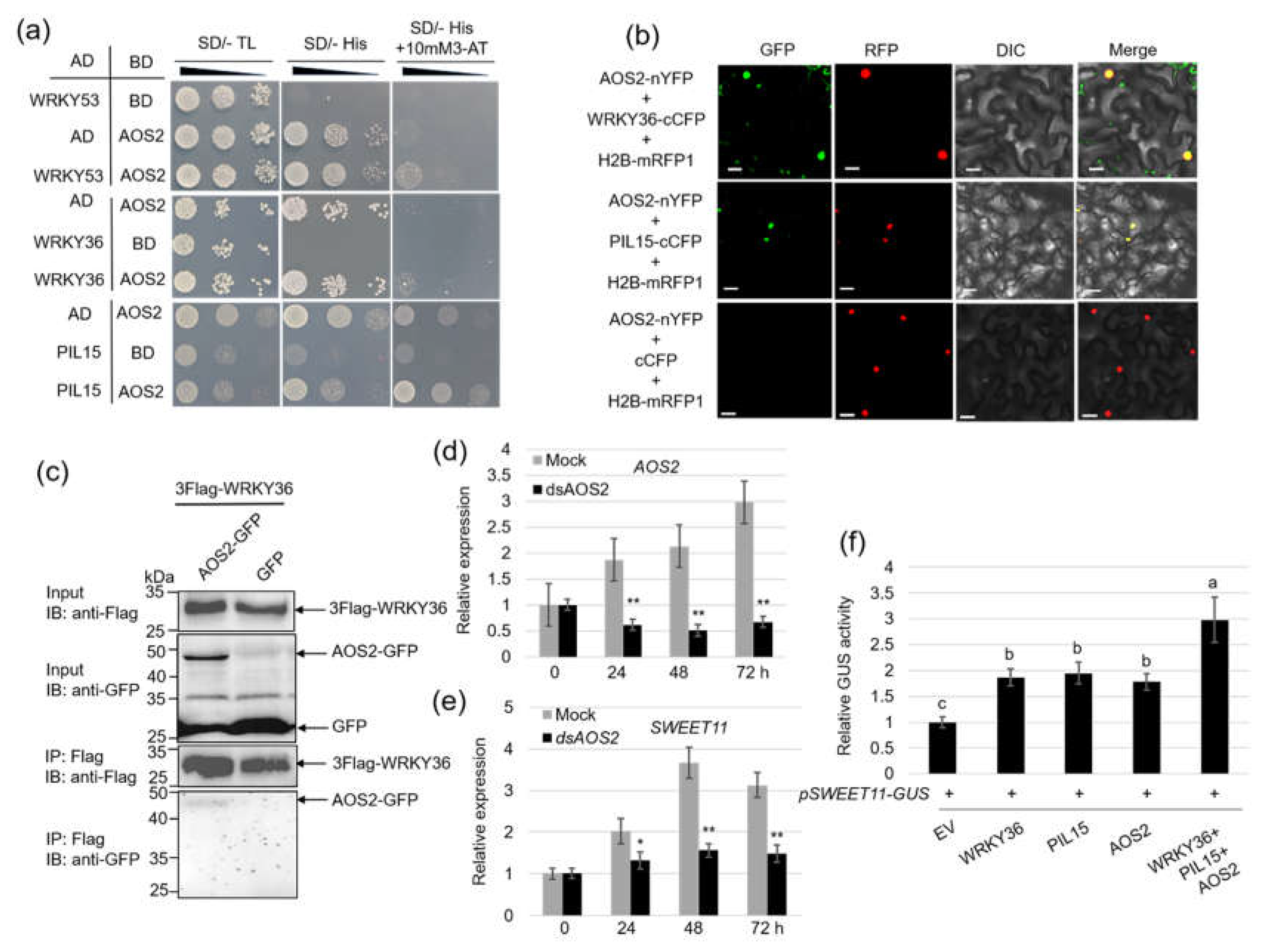

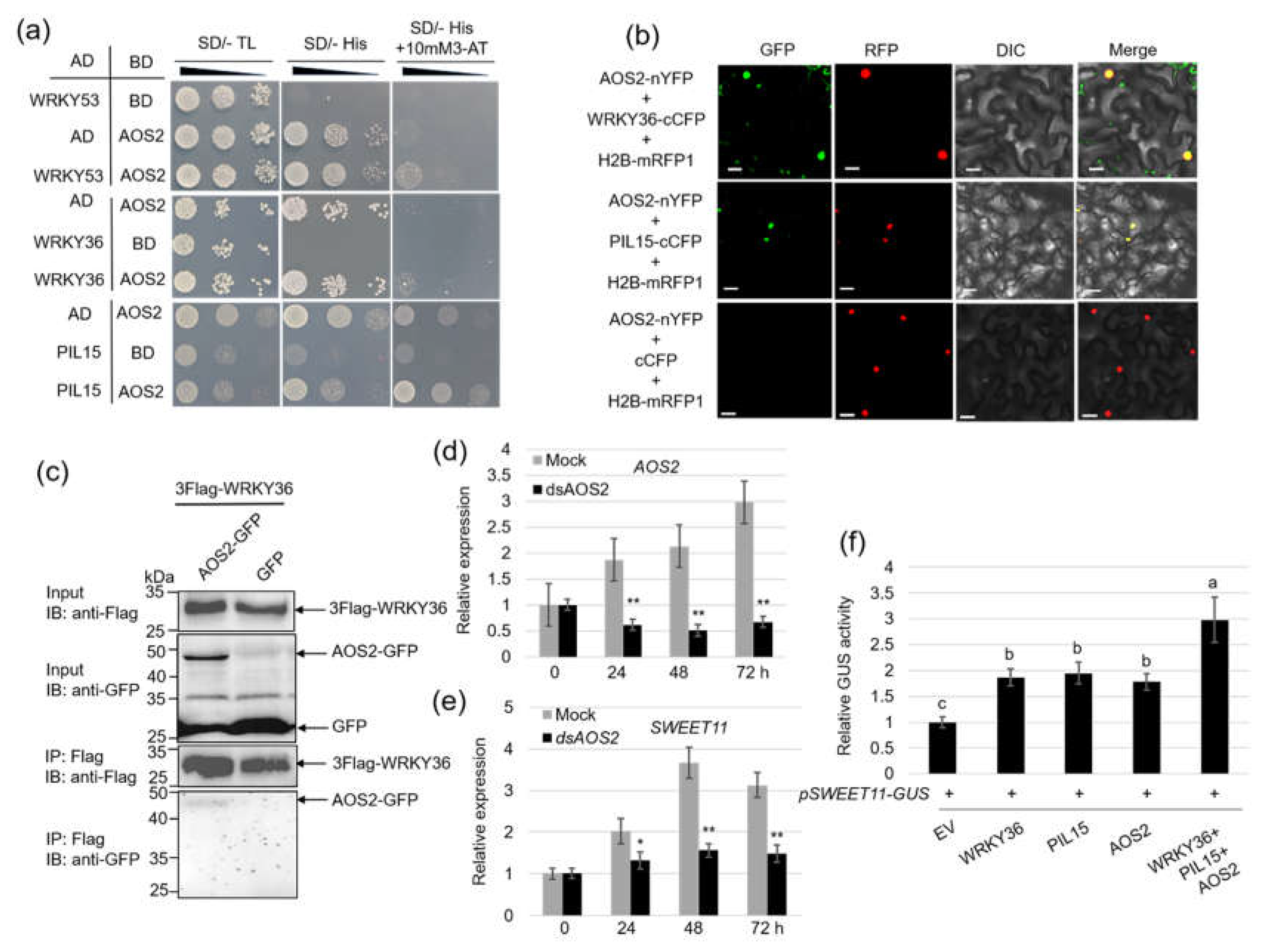

Recently, we identified that

R. solani effector protein AOS2 interacts with WRKY53 to activate

SWEET2a and

SWEET3a for sugar nutrition in pathogen (Yang et al., 2023). Since WRKY36 and PIL15 interact with WRKY53, the interaction between AOS2 and WRKY36 as well as AOS2 and PIL15 was assessed. The results of Y2H assay revealed that AOS2 interacts with WRKY36 and PIL15 (

Figure 7a). BiFC results confirmed that AOS2 interacts with WRKY36 and PIL15 in the nucleus of tobacco cells (

Figure 7b). In addition, Co-IP assay results indicated that 3xFlag-WRKY36 interacts with AOS2-GFP but not with GFP, indicating that WRKY36 interacts with AOS2 (

Figure 7c). Spray-induced gene silencing (SIGS) of

AOS2 inhibited

R. solani-induced

SWEET11 expression (

Figure 7d, e). To investigate whether AOS2–WRKY36–PIL15 form a transcriptional complex to activate

SWEET11, the transient assay was performed. The results indicated that AOS2, WRKY36, and PIL15 activate

pSWEET11, and coexpression of AOS2–WRKY36–PIL15 revealed higher activation against

pSWEET11 than the expression of AOS2, WRKY36, or PIL15 alone (

Figure 7f).

3. Discussion

In any infection, the goal of pathogens is to hijack nutrients from the host. Extensive studies revealed that SWEET sugar transporters are the targets of various pathogens (Breia et al., 2021; Gupta et al., 2021; Ji et al., 2022). Pathogenic infection activates SWEET expression during the early infection stage to obtain sugars from host plants; therefore, inhibition of SWEET activation during pathogen infection could successfully control disease (Gao et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2023). However, SWEET also plays key roles in grain filling. Mutation of SWEET genes exhibited defects in grain development (Li et al., 2022). Some studies reported that the mutation of TAL-binding sequences in SWEET gene promoters successfully improved the resistance of rice to bacterial blight without any growth defect (Xu et al., 2023). However, the TFs which regulate SWEET in tissue-specific manner to balance rice resistance and normal growth are not studied in detail.

3.1. WRKY36–PIL15–AOS2 Activates SWEET11 to Efflux Sugar

SWEET11 negatively regulated resistance of rice to ShB, suggesting that

SWEET11 is a susceptible gene to ShB; however, it positively controlled the grain filling. To assess whether

SWEET11 expression is tissue specific, Y1H assay was conducted between

SWEET11 and the TFs WRKY36 and PIL15 that regulate resistance to

R. solani. Y1H assay revealed that WRKY36 and PIL15 bind to the promoter to activate

SWEET11. After

R. solani inoculation,

wrky36 and

pil15 mutants were less susceptible whereas

WRKY36 OXs and

PIL15 OXs were more susceptible to ShB. Further genetic combinations revealed that

wrky36/pil15 was less susceptible to ShB than

wrky36 and

pil15. In addition, overexpression of

SWEET11 in

wrky36 or

pil15 background increased

wrky36 or

pil15 ShB resistant phenotype, and the lesion lengths on

SWEET11 OX/wrky36 and

SWEET11 OX/pil15 were similar with on

SWEET11 OX. These data suggested that WRKY36 and PIL15 might activate

SWEET11 to increase susceptibility of ShB. Furthermore, WRKY36 interacted with PIL15 to form a transcriptional complex, and WRKY36 and PIL15 had synergistic effects on the activation of

SWEET11.

WRKY36 OX plants exhibited an enlarged lamina joint angle, a typical BR signaling phenotype. Further screening revealed that WRKY36 interacts with WRKY53, a key BR signaling TF. However,

wrky36 mutant is different from

wrky53 mutant (Lan et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2021); it developed normal plant height, suggesting that WRKY36 might has functional redundancy with other WRKY genes for regulating BR signaling. Furthermore, WRKY53 interacted with PIL15; however,

pil15 mutants and

PIL15 OX plants did not exhibit BR signaling phenotype (data not shown). However, WRKY36, PIL15, and WRKY53 negatively regulated resistance of rice to ShB. These data suggested that WRKY36–PIL15–WRKY53 might form a transcriptional complex to regulate defense of rice to ShB. Recently, we demonstrated that AOS2, an effector protein secreted from

R. solani, interacts with WKRY53 to activate

SWEET2a and

SWEET3a to hijack sugar nutrition from rice (Yang et al., 2023). Interestingly, AOS2 also interacts with WRKY36 and PIL15 in the nucleus to activate

SWEET11, and suppression of

AOS2 expression by SIGS approach inhibited

R. solani-infection-mediated induction of

SWEET11. These data suggested that

R. solani secrets effector protein AOS2 into the nucleus of plant cell; further, AOS2–WRKY36–PIL15 transcriptional complex activates sucrose transporter

SWEET11 for obtaining sugars from rice plants (

Figure 8a). Since transcription factor complex involving AOS2 activates multiple

SWEETs, the expression levels of

SWEET2a and

SWEET3a in

PIL15 and

WRKY36 mutants and overexpressing plants were detected. RT-qPCR results showed that the expression of

SWEET2a and

SWEET3a in

PIL15 and

WRKY36 mutants and overexpressing plants did not exhibit a certain pattern. In addition, the expression levels of

SWEET11 in

WRKY53 mutants, overexpressing plants, and

gt1 mutant plants were also detected. RT-qPCR results showed that the expression level of

SWEET11 in

WRKY53 overexpressing plants was higher than that in wild-type plants, but there was no difference between

wrky53 mutant and wild-type plants. Meanwhile, there was no difference in the expression level of

SWEET11 between the

gt1 mutant and wild-type plants (

Figure S5), implying that

R. solani effector AOS2 might interact with different rice transcription factors to activate different set of

SWEETs for sugar nutrition.

3.2. WRKY36–PIL15–miR530 Signaling Negatively Regulates Grain Size

sweet11 mutant exhibited improved resistance to ShB but defective grain filling. WRKY36 and PIL15 activate SWEET11 to negatively regulate resistance of rice to ShB; therefore, seed development was examined in the mutants. Unlike sweet11 mutant, wrky36 and pil15 mutants developed larger seeds than wild-type plants. The seed length of wrky36 mutant was longer but the width was the same compared with wild-type plants. The seed length and width of pil15 mutant were longer than those of wild-type plants. The seeds of WRKY36 OX and PIL15 OX were smaller than the wild-type seeds. These developmental features resulted in higher 1000-grain weight of wrky36 mutants, higher 100-grain weight of pil15 mutants, lower 1000-grain weight of WRKY36 OX and lower 100-grain weight of PIL15 OX than that of their corresponding wild-types. The seed setting ration, panicle number per plant, and seed number per panicle of wrky36 mutants were similar than wild-type plants. WRKY36 OX plants have fewer seed number per panicle compared to wild-type plants, but the seed setting ration and panicle number per plant of wrky36 mutants were similar than wild-type plants. The seed setting ration and panicle number per plant of pil15 mutants or pil15 RDs and PIL15 eGFP OX or PIL15 OXs were similar than wild-type plants. Compared with wild-type plants, PIL15 eGFP OX or PIL15 OXs have fewer seed number per panicle, while pil15 mutants or pil15 RDs have more seed number per panicle, suggesting that WRKY36 and PIL15 are specifically inhibit seed size in rice.

WRKY53 positively regulates seed size by activating BR signaling, suggesting the differential regulation of seed development by WRKY53 and WRKY36. Previously, PIL15 was reported to activate

miR530, a negative regulator of seed development (Sun et al., 2020). Promoter sequence analysis indicated that W-box and G-box appear in the

miR530 promoter. Y1H, transient, and ChIP assays confirmed that WRKY36 bound to

miR530 promoter to activate its transcription. In addition,

miR530 expression level was significantly lower in the developing caryopsis of

wrky36 mutants but higher in

WRKY36 OX plants, which further confirmed the transcriptional activation of WRKY36 to

miR530 in plants. These data suggested that WRKY36–PIL15–SWEET11 in the green tissues negatively regulated the resistance of rice to ShB, and WRKY36–PIL15–miR530 in the seeds negatively regulated grain size (

Figure 8b).

3.3. The Potential Application of WRKY36–PIL15 in ShB-Resistant Breeding

Increasing yield and resistance is one of the main goals of crop breeding. However, the signaling pathways of resistance and yield are often antagonistically regulated (Ning et al., 2017). Our study demonstrated that WRKY36 and PIL15 activate SWEET11 and miR530 in the green tissue and seeds, respectively. wrky36 and pil15 mutants exhibited increased resistance to ShB and yield by controlling grain size, respectively. This suggested that WRKY36 and PIL15 might be the molecular targets for ShB-resistant rice breeding. wrky36 and pil15 mutants exhibited increased yield under the normal condition; however, we believe they will have advantage under R. solai infection. Currently, the genome sequence of rice core resources is available, and Crispr/Cas9-mediated genome editing technique is improving fast. Therefore, identification of useful gene sources for resistance and yield trade-off will be helpful for the precise design of molecular breeding. Our data revealed that a complex transcriptional regulation by WRKY36–PIL15 has advantages in both resistance and yield and demonstrated the potential of using a single gene for controlling both yield and resistance.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Wild-type (WT) (Oryza sativa L. Nipponbare, Zhonghua 11, and Longjing 11), sweet11 mutants (Nip), PIL15 OXs (Nip), pil15 RDs (Nip), wrky36 mutants (ZH11), WRKY36 OXs (ZH11), pil15 mutants (ZH11), PIL15 eGFP OXs (ZH11), wrky53 (LJ11), and WRKY53 OXs (LJ11) were used in this study. The plants were inoculated with R. solani AGI-1A and grown for approximately 2 months in a greenhouse at 30–24 ℃ (day and night). The tobacco used for injection (N. benthamiana) was grown for approximately 1 month in a 22 ℃ light incubator (16 h day/8 h night).

4.2. Pathogens

R. solani AG1-IA was cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium. The 0.4 × 0.8 cm

2 of wood bark was placed on the edge of a 90 mm PDA medium. Further, 1 cm

2 of fungal mass was placed at the center. The

Petri dish was incubated in dark at 30 ℃ for approximately 2 days. The infected bark was placed at the angle between the penultimate leaf sheath of rice. Image J software was used to measure the typical lesion length after 7 days of inoculation (

http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). Six leaf sheaths from each line were analyzed, and the experiments were repeated three times. The data in disease spot statistical chart are presented as the mean ± SE (n > 10).

4.3. Generation of Transgenic Rice Plants

To generate overexpression lines, Ubi: WRKY36 and 35S: PIL15 were transformed into ZH11 plant calli. CRISPR/Cas9-generated mutants (sweet11, wrky36, and pil15) were used. PIL15 OXs (Nip), pil15 RD (Nip), wrky53 (LJ11), and WRKY53 OX (LJ11) were generated as described previously (Tian et al., 2017; Xie et al., 2019). A specific 300-bp fragment from WRKY36 was cloned into the pH7GWIWG2(II) vector and then transformed into pil15 to construct wrky36/pil15 double mutants. SWEET11 was cloned into the pCambia1381-Ubi vector and then transformed into the pil15 to construct SWEET11 OX/pil15. SWEET11 was cloned into the pCambia1381-Ubi vector and then transformed into the wrky36 to construct SWEET11 OX/wrky36.

4.4. Yeast-One Hybrid Assay

In the study, all

pHISi-1 carriers were linearized using

XhoI before transformation. The 2.0 kb of

SWEET11 promoter sequences (

XhoI site was mutated) and rice cDNA TF library (Ouyibio, Shanghai, China) were cloned into

pHISi-1 and

pGAD424 to obtain

pSWEET11-pHISi-1 and

pGAD424-TF yeast vectors, respectively. The

pGAD424-TF plasmid was used to transform YM4271 yeast strain carrying the linearized

pSWEET11-pHISi-1. Two DNA fragments containing two adjacent G-box and one normal G-box element in the 2.0 kb of

miR530 promoter were inserted into

pHISi-1 to obtain the

pmiR530 A-pHISi-1 and

pmiR530 B-pHISi-1 plasmids, respectively. Similarly, four fragments predicted on the 2.0 kb of

miR530 promoter, each containing one W-box, were inserted into

pHISi-1 to obtain the

pmiR530 a/b/c/d -pHISi-1 plasmids, respectively. The coding sequences of

PIL15 and

WRKY36 were cloned into the

pGAD424 vector. The recombinant

pGAD424-WRKY36/PIL15 plasmid was used to transform YM4271 yeast strain carrying the linearized

pmiR530 A/B/a/b/c/d-pHISi-1.

pGAD424 empty vector was used as the control. The analysis of the interaction between proteins and DNA were conducted on synthetic dropout (SD) -Leu or -His media containing various concentrations of 3-aminotriazole (3-AT). The relevant primer information is given in

Table S1.

4.5. Yeast-Two Hybrid Assay

The coding sequences of

WRKY36,

PIL15,

WRKY53, and

AOS2 were cloned into the yeast expression vector

pGAD424 or

pGBT9. The recombinant

pGAD424-PIL15/

WRKY36/WRKY53 plasmid was used to transform AH109 yeast strain. The

pGBT9-WRKY36/

WRKY53/AOS2 plasmid was used to transform Y187 yeast strain. The diploid yeast cells were grown on SD/-Leu-Trp, -His, or -Leu-Trp-His media containing various concentrations of 3-AT to screen for interactions between proteins after mating. The relevant primer information is given in

Table S1.

4.6. Co-IP

The coding sequences of

PIL15,

WRKY36,

AOS2, and

WRKY53 were cloned into the

pGD3G3Flag and

pGD3GGM vectors, respectively, to generate the

PIL15-3xFlag, WRKY36-GFP,

AOS2-GFP,

3xFlag-WRKY36 and

3xFlag-WRKY53 plasmids. All plasmids were used to transform

Agrobacterium GV3101 and expressed in

N. benthamiana leaves by co-infiltration. The injected leaves were placed in dark for 2 days. Co-IP experiment was conducted as described previously (Yuan et al., 2023). The relevant primer information is given in

Table S1.

4.6. BiFC Assay

The

PIL15,

WRKY36, and

AOS2 were fused with partial YFP in

PXNGW and

PXCGW.

PIL15-nYFP,

WRKY36-nYFP,

AOS2-nYFP,

WRKY36-cYFP,

WRKY53-cYFP, and

PIL15-cYFP were generated.

Agrobacterium GV3101 was used for the transient transformation of tobacco. The injected leaves were placed in dark for 2 days. BiFC assay was conducted as described previously (Yuan et al., 2023). The relevant primer information is given in

Table S1.

4.7. Transactivation Assay

Effectors

35S: PIL15,

35S: WRKY36, reporter

pSWEET11 GUS, and internal control

35S: LUC were transformed into protoplasts (Yamaguchi et al., 2010). The β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity was detected using the GUS assay kit (Promega, Madison, USA). The expression of luciferase (LUC) was detected using a luciferase assay kit (Promega, Madison, USA) (Xuan et al., 2013; Yoo et al., 2007). The relevant primer information is given in

Table S1.

4.8. RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from rice seedlings or inoculated leaves using RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara, Dalian, China), and genomic DNA was removed. cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Dalian, China) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The relevant primer information is given in

Table S1.

Ubiquitin was used as the internal control for RT-qPCR. The data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3)

4.9. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR Assay

According to the reference paper, three-week-old overexpressing rice plants with GFP tags were subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation. DNA was used for QPCR sequencing analysis (Yu et al., 2023). The relevant primer information is given in

Table S1.

4.10. SIGS Assay

One-month-old rice were sprayed with enzyme free water and

dsAOS2, and inoculated with

R. solani. Sample and extract RNA from 0-72 hours after inoculation to detect the expression levels of

AOS2 and

SWEET11. The relevant primer information is given in

Table S1.

4.11. Lamina Joint Assay

The 1 cm of the flag leaf, the lamina joint, and 1 cm of the leaf sheath were selected with good growth conditions at the rice heading stage. The angles of lamina joint bending were measured using ImageJ software (

http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/)(http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) (Tong et al., 2009).

4.12. Production Shape Assay

For the statistical analyses of seed length and width, more than 100 seeds from WRKY36, PIL15, and WRKY53 mutants and overexpressions were calculated. For the statistical analyses of plant height, number of effective grains per main panicle, panicle number per plant, and seed number per panicle, the number of statistical samples for WRKY36 and PIL15 mutants and overexpressions were 20 plants.

4.13. Statistical Analysis

Prism 8 was used for statistical analysis (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). All data were expressed as mean ± standard error. The comparison between different groups was conducted through one-way analysis of variance. Significance was determined using student’s t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Significant differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 (Student’s t-test). Different letters above the bars denote statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

Supplementary Materials

Information can be found on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Siting Wang: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Qian Sun: Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis. Shuo Yang: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Huan Chen: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. De Peng Yuan: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Changxi Gan: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Haixia Chen: Validation, Formal analysis. Yongxi Zhi: Validation, Formal analysis. Hongyao Zhu: Validation, Formal analysis. Siting Wang: Writing – review & editing. Yue Gao: Methodology, Investigation, Validation. Yuan Hu Xuan and Xiaofeng Zhu: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32372482, 32072406, 32272499 and 32302379). This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2021-MS-223). This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Education Department of Liaoning Province (LJKZ0641).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bezrutczyk, M., Yang, J., Eom, J.S., Prior, M., Sosso, D., Hartwig, T., Szurek, B., Oliva, R., Vera-Cruz, C., White, F.F., Yang, B. and Frommer, W.B. (2018) Sugar flux and signaling in plant-microbe interactions. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology 93, 675-685.

- Breia, R., Conde, A., Badim, H., Fortes, A.M., Gerós, H. and Granell, A. (2021) Plant SWEETs: from sugar transport to plant-pathogen interaction and more unexpected physiological roles. Plant physiology 186, 836-852. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.J., Chen, Y., Zhang, L.N., Xu, B., Zhang, J.H., Chen, Z.X., Tong, Y.H., Zuo, S.M. and Xu, J.Y. (2016) Overexpression of OsPGIP1 Enhances Rice Resistance to Sheath Blight. Plant disease 100, 388-395. [CrossRef]

- Chu, J., Xu, H., Dong, H. and Xuan, Y.H. (2021) Loose Plant Architecture 1-Interacting Kinesin-like Protein KLP Promotes Rice Resistance to Sheath Blight Disease. Rice (New York, N.Y.) 14, 60. [CrossRef]

- Denancé, N., Sánchez-Vallet, A., Goffner, D. and Molina, A. (2013) Disease resistance or growth: the role of plant hormones in balancing immune responses and fitness costs. Frontiers in plant science 4, 155. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y., Zhai, K., Xie, Z., Yang, D., Zhu, X., Liu, J., Wang, X., Qin, P., Yang, Y., Zhang, G., Li, Q., Zhang, J., Wu, S., Milazzo, J., Mao, B., Wang, E., Xie, H., Tharreau, D. and He, Z. (2017) Epigenetic regulation of antagonistic receptors confers rice blast resistance with yield balance. Science (New York, N.Y.) 355, 962-965. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Xue, C.Y., Liu, J.M., He, Y., Mei, Q., Wei, S. and Xuan, Y.H. (2021) Sheath blight resistance in rice is negatively regulated by WRKY53 via SWEET2a activation. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 585, 117-123. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Zhang, C., Han, X., Wang, Z.Y., Ma, L., Yuan, P., Wu, J.N., Zhu, X.F., Liu, J.M., Li, D.P., Hu, Y.B. and Xuan, Y.H. (2018) Inhibition of OsSWEET11 function in mesophyll cells improves resistance of rice to sheath blight disease. Molecular plant pathology 19, 2149-2161. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.K., Balyan, H.S. and Gautam, T. (2021) SWEET genes and TAL effectors for disease resistance in plants: Present status and future prospects. Molecular plant pathology 22, 1014-1026. [CrossRef]

- He, Z., Webster, S. and He, S.Y. (2022) Growth-defense trade-offs in plants. Current biology : CB 32, R634-r639.

- Hu, K., Cao, J., Zhang, J., Xia, F., Ke, Y., Zhang, H., Xie, W., Liu, H., Cui, Y., Cao, Y., Sun, X., Xiao, J., Li, X., Zhang, Q. and Wang, S. (2017) Improvement of multiple agronomic traits by a disease resistance gene via cell wall reinforcement. Nature plants 3, 17009. [CrossRef]

- Jeena, G.S., Kumar, S. and Shukla, R.K. (2019) Structure, evolution and diverse physiological roles of SWEET sugar transporters in plants. Plant molecular biology 100, 351-365. [CrossRef]

- Ji, J., Yang, L., Fang, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhuang, M., Lv, H. and Wang, Y. (2022) Plant SWEET Family of Sugar Transporters: Structure, Evolution and Biological Functions. Biomolecules 12.

- John Lilly, J. and Subramanian, B. (2019) Gene network mediated by WRKY13 to regulate resistance against sheath infecting fungi in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant science : an international journal of experimental plant biology 280, 269-282. [CrossRef]

- Kim, P., Xue, C.Y., Song, H.D., Gao, Y., Feng, L., Li, Y. and Xuan, Y.H. (2021) Tissue-specific activation of DOF11 promotes rice resistance to sheath blight disease and increases grain weight via activation of SWEET14. Plant biotechnology journal 19, 409-411. [CrossRef]

- Kouzai, Y., Kimura, M., Watanabe, M., Kusunoki, K., Osaka, D., Suzuki, T., Matsui, H., Yamamoto, M., Ichinose, Y., Toyoda, K., Matsuura, T., Mori, I.C., Hirayama, T., Minami, E., Nishizawa, Y., Inoue, K., Onda, Y., Mochida, K. and Noutoshi, Y. (2018) Salicylic acid-dependent immunity contributes to resistance against Rhizoctonia solani, a necrotrophic fungal agent of sheath blight, in rice and Brachypodium distachyon. The New phytologist 217, 771-783.

- Lan, J., Lin, Q., Zhou, C., Ren, Y., Liu, X., Miao, R., Jing, R., Mou, C., Nguyen, T., Zhu, X., Wang, Q., Zhang, X., Guo, X., Liu, S., Jiang, L. and Wan, J. (2020) Small grain and semi-dwarf 3, a WRKY transcription factor, negatively regulates plant height and grain size by stabilizing SLR1 expression in rice. Plant molecular biology 104, 429-450. [CrossRef]

- Li, N., Lin, B., Wang, H., Li, X., Yang, F., Ding, X., Yan, J. and Chu, Z. (2019) Natural variation in ZmFBL41 confers banded leaf and sheath blight resistance in maize. Nature genetics 51, 1540-1548. [CrossRef]

- Li, P., Wang, L., Liu, H. and Yuan, M. (2022) Impaired SWEET-mediated sugar transportation impacts starch metabolism in developing rice seeds. The Crop Journal 10, 98-108. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, H., Zhang, Q., Zhai, H., Liu, Q. and He, S. (2017) The Plasma Membrane-Localized Sucrose Transporter IbSWEET10 Contributes to the Resistance of Sweet Potato to Fusarium oxysporum. Frontiers in plant science 8, 197. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.J., Chu, J., Kumar, V., Yuan, P., Li, Z.M., Mei, Q. and Xuan, Y.H. (2021) Protein Phosphatase 2A Catalytic Subunit PP2A-1 Enhances Rice Resistance to Sheath Blight Disease. Frontiers in genome editing 3, 632136. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q., Yuan, M., Zhou, Y., Li, X., Xiao, J. and Wang, S. (2011) A paralog of the MtN3/saliva family recessively confers race-specific resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae in rice. Plant, cell & environment 34, 1958-1969.

- Livak, K.J. and Schmittgen, T.D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (San Diego, Calif.) 25, 402-408.

- Ma, L., Zhang, D., Miao, Q., Yang, J., Xuan, Y. and Hu, Y. (2017) Essential Role of Sugar Transporter OsSWEET11 During the Early Stage of Rice Grain Filling. Plant & cell physiology 58, 863-873. [CrossRef]

- Miao Liu, J., Mei, Q., Yun Xue, C., Yuan Wang, Z., Pin Li, D., Xin Zhang, Y. and Hu Xuan, Y. (2021) Mutation of G-protein γ subunit DEP1 increases planting density and resistance to sheath blight disease in rice. Plant biotechnology journal 19, 418-420.

- Ning, Y., Liu, W. and Wang, G.L. (2017) Balancing Immunity and Yield in Crop Plants. Trends in plant science 22, 1069-1079. [CrossRef]

- Peng, X., Wang, H., Jang, J.C., Xiao, T., He, H., Jiang, D. and Tang, X. (2016) OsWRKY80-OsWRKY4 Module as a Positive Regulatory Circuit in Rice Resistance Against Rhizoctonia solani. Rice (New York, N.Y.) 9, 63. [CrossRef]

- Pinson, S.R.M., Capdevielle, F.M. and Oard, J.H. (2005) Confirming QTLs and Finding Additional Loci Conditioning Sheath Blight Resistance in Rice Using Recombinant Inbred Lines. Crop Science 45, 503-510. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L., Zheng, L., Sheng, C., Zhao, H., Jin, H. and Niu, D. (2020) Rice siR109944 suppresses plant immunity to sheath blight and impacts multiple agronomic traits by affecting auxin homeostasis. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology 102, 948-964. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q., Li, T.Y., Li, D.D., Wang, Z.Y., Li, S., Li, D.P., Han, X., Liu, J.M. and Xuan, Y.H. (2019a) Overexpression of Loose Plant Architecture 1 increases planting density and resistance to sheath blight disease via activation of PIN-FORMED 1a in rice. Plant biotechnology journal 17, 855-857.

- Sun, Q., Liu, Y., Wang, Z.Y., Li, S., Ye, L., Xie, J.X., Zhao, G.Q., Wang, H.N., Wang, Y., Li, S., Wei, S.H. and Xuan, Y.H. (2019b) Isolation and characterization of genes related to sheath blight resistance via the tagging of mutants in rice. Plant Gene 19.

- Sun, W., Xu, X.H., Li, Y., Xie, L., He, Y., Li, W., Lu, X., Sun, H. and Xie, X. (2020) OsmiR530 acts downstream of OsPIL15 to regulate grain yield in rice. The New phytologist 226, 823-837. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X., He, M., Mei, E., Zhang, B., Tang, J., Xu, M., Liu, J., Li, X., Wang, Z., Tang, W., Guan, Q. and Bu, Q. (2021) WRKY53 integrates classic brassinosteroid signaling and the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway to regulate rice architecture and seed size. The Plant cell 33, 2753-2775. [CrossRef]

- Tian, X., Li, X., Zhou, W., Ren, Y., Wang, Z., Liu, Z., Tang, J., Tong, H., Fang, J. and Bu, Q. (2017) Transcription Factor OsWRKY53 Positively Regulates Brassinosteroid Signaling and Plant Architecture. Plant physiology 175, 1337-1349. [CrossRef]

- Tong, H., Jin, Y., Liu, W., Li, F., Fang, J., Yin, Y., Qian, Q., Zhu, L. and Chu, C. (2009) DWARF AND LOW-TILLERING, a new member of the GRAS family, plays positive roles in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology 58, 803-816. [CrossRef]

- Wang, A., Shu, X., Jing, X., Jiao, C., Chen, L., Zhang, J., Ma, L., Jiang, Y., Yamamoto, N., Li, S., Deng, Q., Wang, S., Zhu, J., Liang, Y., Zou, T., Liu, H., Wang, L., Huang, Y., Li, P. and Zheng, A. (2021) Identification of rice (Oryza sativa L.) genes involved in sheath blight resistance via a genome-wide association study. Plant biotechnology journal 19, 1553-1566.

- Wang, D., Pajerowska-Mukhtar, K., Culler, A.H. and Dong, X. (2007) Salicylic acid inhibits pathogen growth in plants through repression of the auxin signaling pathway. Current biology : CB 17, 1784-1790. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. and Wang, Z.Y. (2014) At the intersection of plant growth and immunity. Cell host & microbe 15, 400-402. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C., Zhang, G., An, L., Chen, X. and Fang, R. (2019) Phytochrome-interacting factor-like protein OsPIL15 integrates light and gravitropism to regulate tiller angle in rice. Planta 250, 105-114. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., Xu, X., Li, Y., Liu, L., Wang, Q., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Yan, J., Cheng, G., Zou, L., Zhu, B. and Chen, G. (2023) Tal6b/AvrXa27A, a Hidden TALE Targeting both the Susceptibility Gene OsSWEET11a and the Resistance Gene Xa27 in Rice. Plant communications, 100721. [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Y.H., Priatama, R.A., Huang, J., Je, B.I., Liu, J.M., Park, S.J., Piao, H.L., Son, D.Y., Lee, J.J., Park, S.H., Jung, K.H., Kim, T.H. and Han, C.D. (2013) Indeterminate domain 10 regulates ammonium-mediated gene expression in rice roots. The New phytologist 197, 791-804.

- Yamaguchi, M., Ohtani, M., Mitsuda, N., Kubo, M., Ohme-Takagi, M., Fukuda, H. and Demura, T. (2010) VND-INTERACTING2, a NAC domain transcription factor, negatively regulates xylem vessel formation in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell 22, 1249-1263.

- Yang, S., Fu, Y., Zhang, Y., Peng Yuan, D., Li, S., Kumar, V., Mei, Q. and Hu Xuan, Y. (2023) Rhizoctonia solani transcriptional activator interacts with rice WRKY53 and grassy tiller 1 to activate SWEET transporters for nutrition. Journal of advanced research 50, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.D., Cho, Y.H. and Sheen, J. (2007) Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nature protocols 2, 1565-1572. [CrossRef]

- Yu, J., Zhu, C., Xuan, W., An, H., Tian, Y., Wang, B., Chi, W., Chen, G., Ge, Y., Li, J., Dai, Z., Liu, Y., Sun, Z., Xu, D., Wang, C. and Wan, J. (2023) Genome-wide association studies identify OsWRKY53 as a key regulator of salt tolerance in rice. Nature communications 14, 3550. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M. and Wang, S. (2013) Rice MtN3/saliva/SWEET family genes and their homologs in cellular organisms. Molecular plant 6, 665-674. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P., Yang, S., Feng, L., Chu, J., Dong, H., Sun, J., Chen, H., Li, Z., Yamamoto, N., Zheng, A., Li, S., Yoon, H.C., Chen, J., Ma, D. and Xuan, Y.H. (2023) Red-light receptor phytochrome B inhibits BZR1-NAC028-CAD8B signaling to negatively regulate rice resistance to sheath blight. Plant, cell & environment 46, 1249-1263.

- Yuan, P., Zhang, C., Wang, Z.Y., Zhu, X.F. and Xuan, Y.H. (2018) RAVL1 Activates Brassinosteroids and Ethylene Signaling to Modulate Response to Sheath Blight Disease in Rice. Phytopathology 108, 1104-1113. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Bai, M.Y. and Chong, K. (2014) Brassinosteroid-mediated regulation of agronomic traits in rice. Plant cell reports 33, 683-696. [CrossRef]

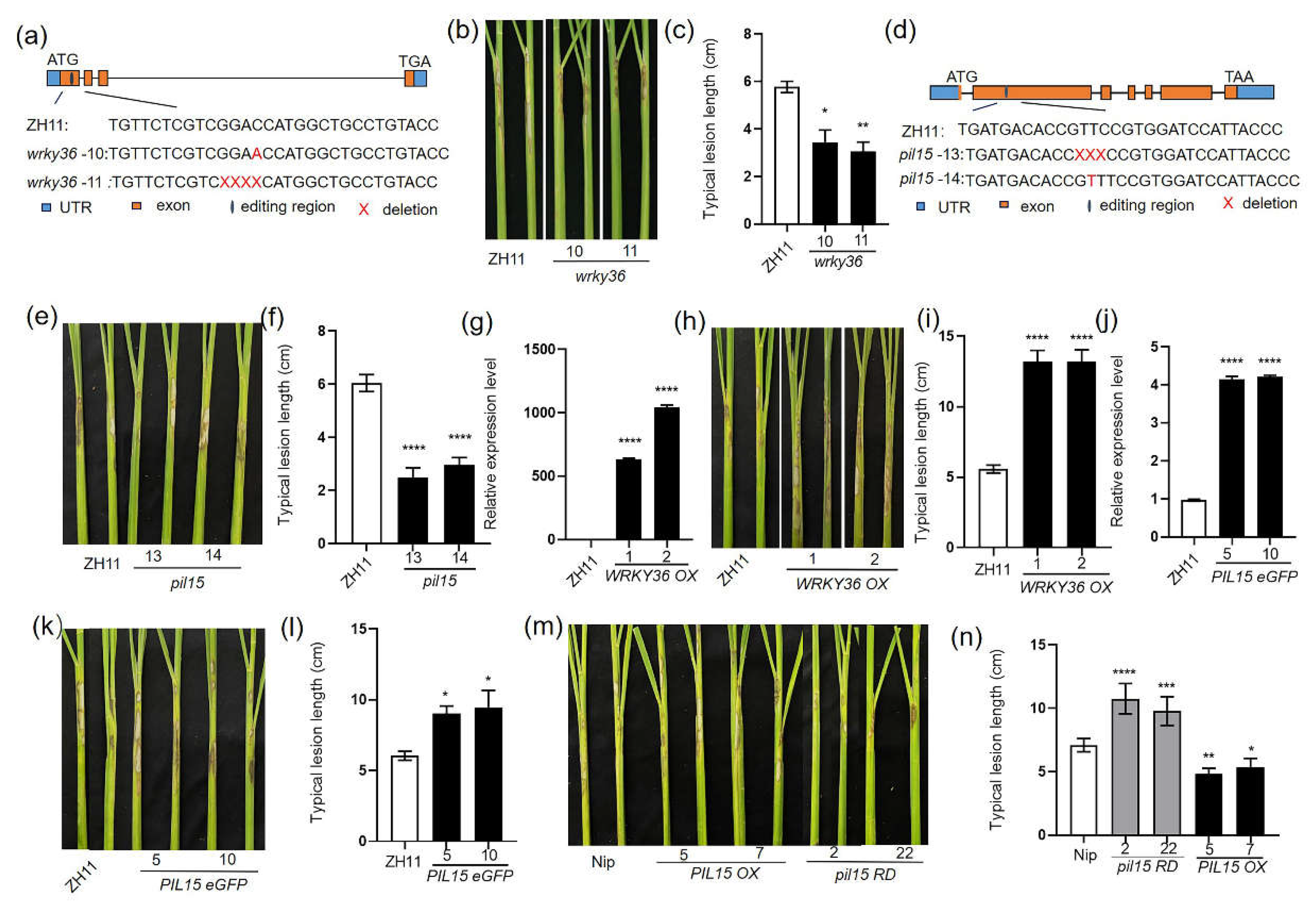

Figure 1.

Response of WRKY36 and PIL15 to Rhizoctonia solani AG1-1A. (A and D) Mutation site sequence information of WRKY36 and PIL15 genome-editing mutants generated using CRISPR/Cas9. (B) WT and wrky36 mutants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath surface was measured (C). (E) WT and pil15 mutants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath surface was measured (F). (G) The expression of WRKY36 in WT and WRKY36 OXs was examined using RT-qPCR. (H) WT and WRKY36 OXs were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath surface was measured (I). (J) The expression of PIL15 in WT and PIL15 eGFP OXs was examined using RT-qPCR. (K) WT and PIL15 eGFP OXs were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath surface was measured (L). (M) WT, PIL15 OXs and pil15 RDs were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesion on the leaf sheath surface was measured (N).

Figure 1.

Response of WRKY36 and PIL15 to Rhizoctonia solani AG1-1A. (A and D) Mutation site sequence information of WRKY36 and PIL15 genome-editing mutants generated using CRISPR/Cas9. (B) WT and wrky36 mutants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath surface was measured (C). (E) WT and pil15 mutants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath surface was measured (F). (G) The expression of WRKY36 in WT and WRKY36 OXs was examined using RT-qPCR. (H) WT and WRKY36 OXs were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath surface was measured (I). (J) The expression of PIL15 in WT and PIL15 eGFP OXs was examined using RT-qPCR. (K) WT and PIL15 eGFP OXs were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath surface was measured (L). (M) WT, PIL15 OXs and pil15 RDs were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesion on the leaf sheath surface was measured (N).

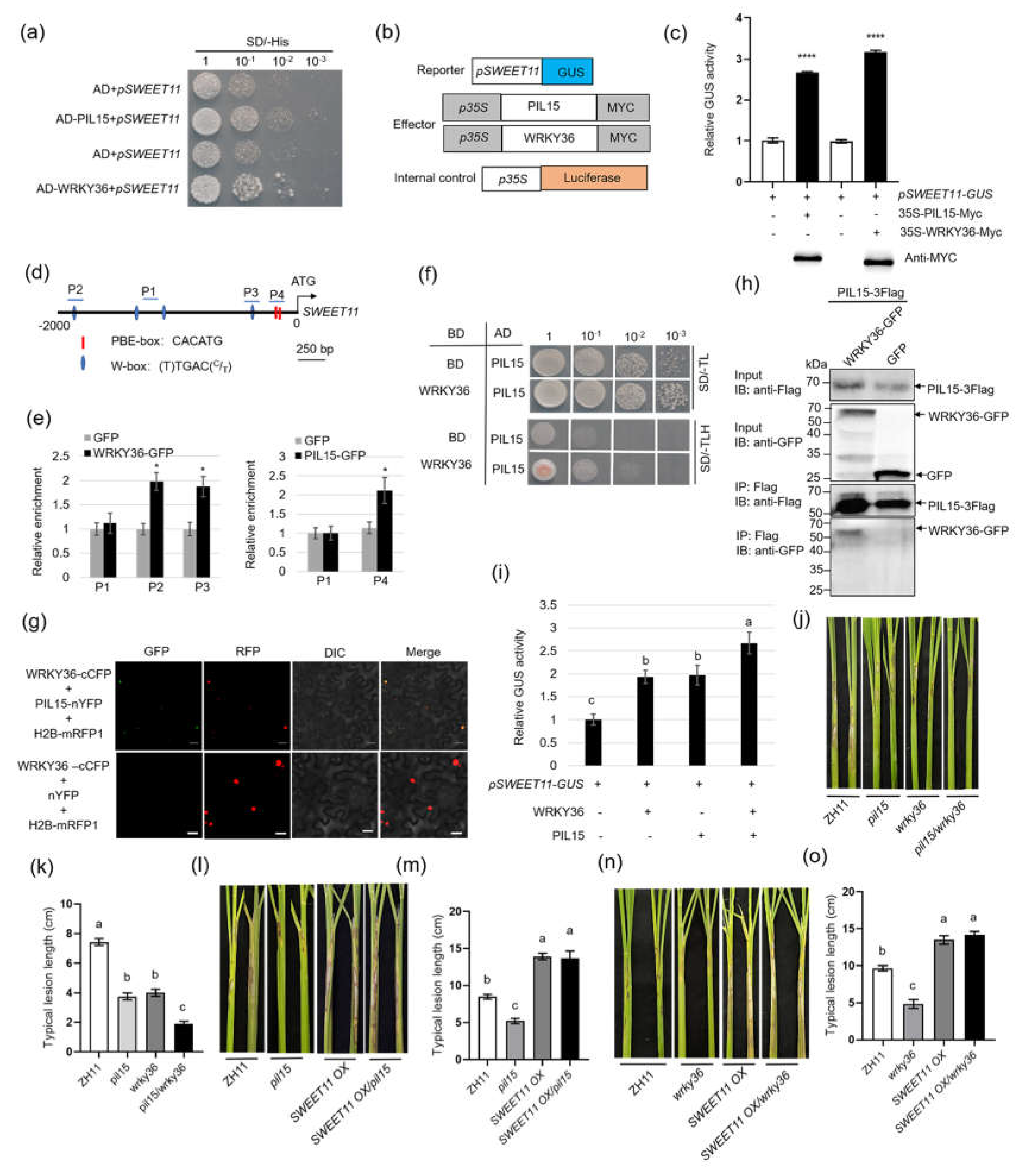

Figure 2.

Confirmation of activation of SWEET11 by WRKY36 or PIL15, and the interaction between WRKY36 and PIL15. (A) Yeast-one hybrid assay of the binding of PIL15 or WRKY36 to the SWEET11 promoter. (B) Reporter, effector, and internal control vector diagram. (C) Transactivation assays verified that WRKY36 and PIL15 activated SWEET11 expression. (D) The putative W-box and PBE-box elements in the 2.0-kb region of the SWEET11 promoter. (E) ChIP-qPCR assay showing that WRKY36 and PIL15 directly bind to the W-box and PBE-box motif in the SWEET11 promoter, respectively. The promoter fragment of SWEET11 containing the W-box motif (P2, P3) was enriched in the ChIP-qPCR analysis rather than in the negative control (P1). Similarly, the promoter fragment of SWEET11 containing the PBE-box motif (P4) was enriched in the ChIP-qPCR analysis rather than in the negative control (P1). (F) Yeast-two hybrid assay verified the interaction between PIL15 and WRKY36. (G) BiFC assay verified the interaction between PIL15 and WRKY36 in N. benthamiana leaves. Co-transformation of PIL15-nYFP and WRKY36-cCFP led to the reconstitution of GFP signal, whereas no signal was detected when WRKY36-cCFP and nYFP were coexpressed. (H) Co-IP assays indicated the interaction between PIL15 and WRKY36 in plants. PIL15-3xFlag and WRKY36-GFP were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. The coexpression of PIL15-3xFlag and GFP was used as a negative control. (I) The transient assay showed that WRKY36 and PIL15 both activated SWEET11 expression in an additive manner. The promoter of the SWEET11-driven reporter gene was co-expressed with WRKY36 or PIL15 individually or together. (J) WT, pil15, wrky36, wrky36/pil15 plants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath was measured (K). (L) WT, pil15, SWEET11 OX, SWEET11 OX/pil15 plants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath was measured (M). (N) WT, wrky36, SWEET11 OX, SWEET11 OX/wrky36 plants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath was measured (O).

Figure 2.

Confirmation of activation of SWEET11 by WRKY36 or PIL15, and the interaction between WRKY36 and PIL15. (A) Yeast-one hybrid assay of the binding of PIL15 or WRKY36 to the SWEET11 promoter. (B) Reporter, effector, and internal control vector diagram. (C) Transactivation assays verified that WRKY36 and PIL15 activated SWEET11 expression. (D) The putative W-box and PBE-box elements in the 2.0-kb region of the SWEET11 promoter. (E) ChIP-qPCR assay showing that WRKY36 and PIL15 directly bind to the W-box and PBE-box motif in the SWEET11 promoter, respectively. The promoter fragment of SWEET11 containing the W-box motif (P2, P3) was enriched in the ChIP-qPCR analysis rather than in the negative control (P1). Similarly, the promoter fragment of SWEET11 containing the PBE-box motif (P4) was enriched in the ChIP-qPCR analysis rather than in the negative control (P1). (F) Yeast-two hybrid assay verified the interaction between PIL15 and WRKY36. (G) BiFC assay verified the interaction between PIL15 and WRKY36 in N. benthamiana leaves. Co-transformation of PIL15-nYFP and WRKY36-cCFP led to the reconstitution of GFP signal, whereas no signal was detected when WRKY36-cCFP and nYFP were coexpressed. (H) Co-IP assays indicated the interaction between PIL15 and WRKY36 in plants. PIL15-3xFlag and WRKY36-GFP were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. The coexpression of PIL15-3xFlag and GFP was used as a negative control. (I) The transient assay showed that WRKY36 and PIL15 both activated SWEET11 expression in an additive manner. The promoter of the SWEET11-driven reporter gene was co-expressed with WRKY36 or PIL15 individually or together. (J) WT, pil15, wrky36, wrky36/pil15 plants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath was measured (K). (L) WT, pil15, SWEET11 OX, SWEET11 OX/pil15 plants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath was measured (M). (N) WT, wrky36, SWEET11 OX, SWEET11 OX/wrky36 plants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath was measured (O).

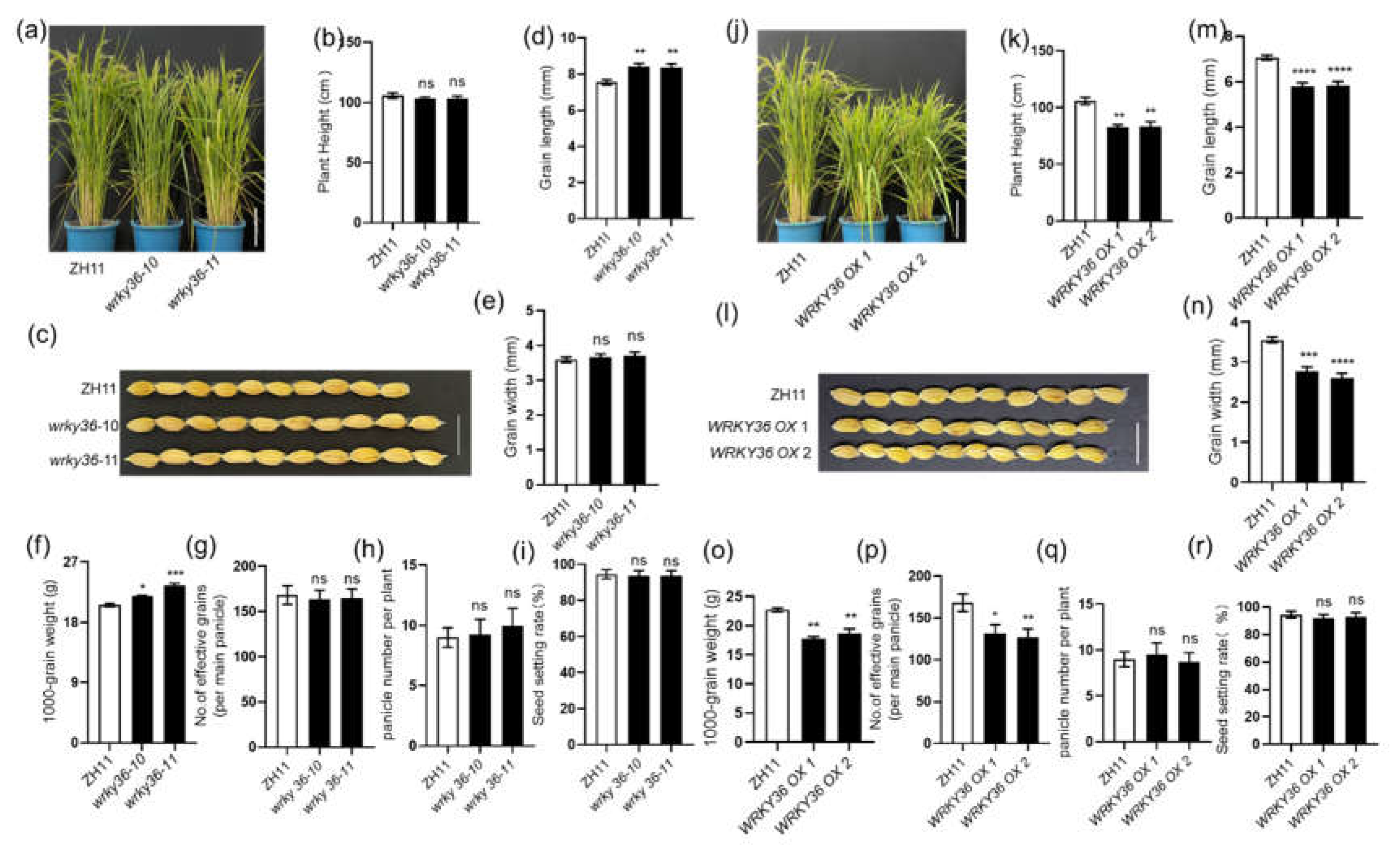

Figure 3.

WRKY36 regulates seed development. (A) Phenotypes of 3-month-old wrky36 mutants and WT plants. Scale bar = 20 cm. The height of plants was measured (B). (C) Grains with hulls from wrky36 and WT. Scale bar = 1 cm. (D) Seed length of wrky36 and WT. (E) Seed width of wrky36 and WT. (F) The 1000-grain weight of wrky36 and WT. (G) Number of effective grains per panicle in wrky36 and WT. (H) Panicle number per plant of wrky36 and WT. (I) The seed setting rate (%) of wrky36 and WT. (J) Phenotypes of 3-month-old WRKY36 OXs and WT plants. Scale bar = 20 cm. The height of plants was measured (K). (L) Grains with hulls from WRKY36 OXs and WT. Scale bar = 1 cm. (M) Seed length of WRKY36 OXs and WT. (N) Seed width of WRKY36 OXs and WT. (O) The 1000-grain weight of WRKY36 OXs and WT. (P) Number of effective grains per panicle in WRKY36 OX and WT. (Q) Panicle number per plant of WRKY36 OX and WT. (R) The seed setting rate (%) of WRKY36 OX and WT. The data in (B, D–I, K, and M–R) are presented as the mean ± SE (B, G, H, I, K, P, Q, and R, n = 20 plants; C–F and L–O, n >100 seeds; F and O, n = 3 replicates).

Figure 3.

WRKY36 regulates seed development. (A) Phenotypes of 3-month-old wrky36 mutants and WT plants. Scale bar = 20 cm. The height of plants was measured (B). (C) Grains with hulls from wrky36 and WT. Scale bar = 1 cm. (D) Seed length of wrky36 and WT. (E) Seed width of wrky36 and WT. (F) The 1000-grain weight of wrky36 and WT. (G) Number of effective grains per panicle in wrky36 and WT. (H) Panicle number per plant of wrky36 and WT. (I) The seed setting rate (%) of wrky36 and WT. (J) Phenotypes of 3-month-old WRKY36 OXs and WT plants. Scale bar = 20 cm. The height of plants was measured (K). (L) Grains with hulls from WRKY36 OXs and WT. Scale bar = 1 cm. (M) Seed length of WRKY36 OXs and WT. (N) Seed width of WRKY36 OXs and WT. (O) The 1000-grain weight of WRKY36 OXs and WT. (P) Number of effective grains per panicle in WRKY36 OX and WT. (Q) Panicle number per plant of WRKY36 OX and WT. (R) The seed setting rate (%) of WRKY36 OX and WT. The data in (B, D–I, K, and M–R) are presented as the mean ± SE (B, G, H, I, K, P, Q, and R, n = 20 plants; C–F and L–O, n >100 seeds; F and O, n = 3 replicates).

Figure 4.

PIL15 regulates seed development. (A) Phenotypes of 3-month-old PIL15 RD mutants, PIL15 OXs and WT plants. Scale bar = 20 cm. The height of plants was measured (B). (C) Grains with hulls from pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. Scale bar = 1 cm. (D) Seed length of pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (E) Seed width of pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (F) The 100-grain weight of pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (G) Number of effective grains per panicle in pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (H) Panicle number per plant of pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (I) The seed setting rate (%) of pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (J) Grains with hulls from pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. Scale bar = 1 cm. (K) Seed length of pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. (L) Seed width of pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. (M) The 100-grain weight of pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. (N) Number of effective grains per panicle in pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. (O) Panicle number per plant of pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. (P) The seed setting rate (%) of pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. The data in (B–I and K–P) are presented as the mean ± SE (B, G, H, I, N, O, and P, n = 20 plants; C–F and J–M, n >100 seeds; F and M, n = 3 replicates).

Figure 4.

PIL15 regulates seed development. (A) Phenotypes of 3-month-old PIL15 RD mutants, PIL15 OXs and WT plants. Scale bar = 20 cm. The height of plants was measured (B). (C) Grains with hulls from pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. Scale bar = 1 cm. (D) Seed length of pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (E) Seed width of pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (F) The 100-grain weight of pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (G) Number of effective grains per panicle in pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (H) Panicle number per plant of pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (I) The seed setting rate (%) of pil15 mutants, PIL15 eGFP OXs, and WT. (J) Grains with hulls from pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. Scale bar = 1 cm. (K) Seed length of pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. (L) Seed width of pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. (M) The 100-grain weight of pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. (N) Number of effective grains per panicle in pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. (O) Panicle number per plant of pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. (P) The seed setting rate (%) of pil15 RDs, PIL15 OXs, and WT. The data in (B–I and K–P) are presented as the mean ± SE (B, G, H, I, N, O, and P, n = 20 plants; C–F and J–M, n >100 seeds; F and M, n = 3 replicates).

Figure 5.

Confirmation of activation of miR530 by WRKY36–PIL15. (A) Putative W-box and G-box elements in the 2.0-kb region of the miR530 promoter. (B) Yeast-one hybrid assay of the binding of PIL15 and WRKY36 to the miR530 promoter. (C) The transient assay showed that WRKY36 and PIL15 both activated miR530 expression in an additive manner. WRKY36 and PIL15 cannot activate miR530 transcription with W-box and G-box site mutations in the miR530 promoter (mwpmiR530 and mgpmiR530). (D) ChIP-qPCR assay showing that WRKY36 directly bind to the W-box motif in the miR530 promoter. The promoter fragment of miR530 containing the W-box motif (P1, P2, and P4) was enriched in the ChIP-qPCR analysis rather than in the negative control (P3). (E) ChIP-qPCR assay showing that PIL15 directly bind to the G-box motif in the miR530 promoter. The promoter fragment of miR530 containing the G-box motif (P3, P4) was enriched in the ChIP-qPCR analysis. (F) Expression of miR530 (miR530 precursor) in wkry36, WRKY36 OX and WT plants. Ubiquitin was used as the internal control for RT-qPCR. The data in (C–F) are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3). Significant differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01;.

Figure 5.

Confirmation of activation of miR530 by WRKY36–PIL15. (A) Putative W-box and G-box elements in the 2.0-kb region of the miR530 promoter. (B) Yeast-one hybrid assay of the binding of PIL15 and WRKY36 to the miR530 promoter. (C) The transient assay showed that WRKY36 and PIL15 both activated miR530 expression in an additive manner. WRKY36 and PIL15 cannot activate miR530 transcription with W-box and G-box site mutations in the miR530 promoter (mwpmiR530 and mgpmiR530). (D) ChIP-qPCR assay showing that WRKY36 directly bind to the W-box motif in the miR530 promoter. The promoter fragment of miR530 containing the W-box motif (P1, P2, and P4) was enriched in the ChIP-qPCR analysis rather than in the negative control (P3). (E) ChIP-qPCR assay showing that PIL15 directly bind to the G-box motif in the miR530 promoter. The promoter fragment of miR530 containing the G-box motif (P3, P4) was enriched in the ChIP-qPCR analysis. (F) Expression of miR530 (miR530 precursor) in wkry36, WRKY36 OX and WT plants. Ubiquitin was used as the internal control for RT-qPCR. The data in (C–F) are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3). Significant differences: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01;.

Figure 6.

Confirmation of the interaction between WRKY36 and WRKY53. (A) Yeast-two hybrid assay verified the interaction between WRKY53 and WRKY36. (B) BiFC assay indicated the interaction between WRKY53 and WRKY36 in N. benthamiana leaves. Co-transformation of WRKY36-nYFP and WRKY53-cCFP led to the reconstitution of GFP signal, whereas no signal was detected when WRKY53-cCFP and nYFP were coexpressed. (C) Co-IP assays indicated the interaction between WRKY53 and WRKY36 in plants. 3xFlag-WRKY53 and WRKY36-GFP were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. The coexpression of 3xFlag-WRKY53 and GFP was used as a negative control. (D) WT and wrky53 mutants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath surface was measured (E). (D) Six leaf sheaths from each line were analyzed, and the experiments were repeated three times. The data in (E) are presented as the mean ± SE (n > 10). (F) Grains with hulls from wrky53, WRKY53 OX, and WT. Scale bar = 1 cm. (G) Seed length of wrky53, WRKY53 OX, and WT. (H) Seed width of wrky53, WRKY53 OX, and WT. (I) The 100-grain weight of wrky53, WRKY53 OX, and WT. The data in (G–I) are presented as the mean ± SE. (F–H, n >100 seeds; I, n = 3 replicates). (J) Yeast-two hybrid assay verified the interaction between WRKY53 and PIL15. (K) BiFC assay indicated the interaction between WRKY53 and PIL15 in N. benthamiana leaves. Co-transformation of PIL15-nYFP and WRKY53-cCFP led to the reconstitution of GFP signal, whereas no signal was detected when WRKY53-cCFP and nYFP were coexpressed.

Figure 6.

Confirmation of the interaction between WRKY36 and WRKY53. (A) Yeast-two hybrid assay verified the interaction between WRKY53 and WRKY36. (B) BiFC assay indicated the interaction between WRKY53 and WRKY36 in N. benthamiana leaves. Co-transformation of WRKY36-nYFP and WRKY53-cCFP led to the reconstitution of GFP signal, whereas no signal was detected when WRKY53-cCFP and nYFP were coexpressed. (C) Co-IP assays indicated the interaction between WRKY53 and WRKY36 in plants. 3xFlag-WRKY53 and WRKY36-GFP were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. The coexpression of 3xFlag-WRKY53 and GFP was used as a negative control. (D) WT and wrky53 mutants were inoculated with R. solani. The length of lesions on the leaf sheath surface was measured (E). (D) Six leaf sheaths from each line were analyzed, and the experiments were repeated three times. The data in (E) are presented as the mean ± SE (n > 10). (F) Grains with hulls from wrky53, WRKY53 OX, and WT. Scale bar = 1 cm. (G) Seed length of wrky53, WRKY53 OX, and WT. (H) Seed width of wrky53, WRKY53 OX, and WT. (I) The 100-grain weight of wrky53, WRKY53 OX, and WT. The data in (G–I) are presented as the mean ± SE. (F–H, n >100 seeds; I, n = 3 replicates). (J) Yeast-two hybrid assay verified the interaction between WRKY53 and PIL15. (K) BiFC assay indicated the interaction between WRKY53 and PIL15 in N. benthamiana leaves. Co-transformation of PIL15-nYFP and WRKY53-cCFP led to the reconstitution of GFP signal, whereas no signal was detected when WRKY53-cCFP and nYFP were coexpressed.

Figure 7.

AOS2–WRKY36–PIL15 transcriptional complex activates SWEET11. (A) Yeast-two hybrid assay verified the interaction of WRKY53, PIL15, and WRKY36 with AOS2. (B) BiFC assay indicated the interaction of WRKY36 and PIL15 with AOS2 in N. benthamiana leaves. Co-transformation of AOS2-nYFP and WRKY36-cCFP or AOS2-nYFP and PIL15-cCFP led to the reconstitution of GFP signal, whereas no signal was detected when AOS2-nYFP and cCFP were coexpressed. (C) Co-IP assays indicated the interaction between WRKY36 and AOS2 in plants. 3xFlag-WRKY36 and AOS2-GFP were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. The coexpression of 3xFlag-WRKY36 and GFP was used as a negative control. (D) RT-qPCR analysis of AOS2 gene expression levels 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after R. solani inoculation. Mock was treated with RNase-free water. Rs-α-tubulin was used as the internal control for RT-qPCR. (E) RT-qPCR analysis of SWEET11 gene expression levels 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after R. solani inoculation. Mock was treated with RNase-free water. Ubiquitin was used as the internal control for RT-qPCR. (F) The transient assay showed that WRKY36, PIL15, and AOS2 both activated SWEET11 expression in an additive manner. The data in (D–F) are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3).

Figure 7.

AOS2–WRKY36–PIL15 transcriptional complex activates SWEET11. (A) Yeast-two hybrid assay verified the interaction of WRKY53, PIL15, and WRKY36 with AOS2. (B) BiFC assay indicated the interaction of WRKY36 and PIL15 with AOS2 in N. benthamiana leaves. Co-transformation of AOS2-nYFP and WRKY36-cCFP or AOS2-nYFP and PIL15-cCFP led to the reconstitution of GFP signal, whereas no signal was detected when AOS2-nYFP and cCFP were coexpressed. (C) Co-IP assays indicated the interaction between WRKY36 and AOS2 in plants. 3xFlag-WRKY36 and AOS2-GFP were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. The coexpression of 3xFlag-WRKY36 and GFP was used as a negative control. (D) RT-qPCR analysis of AOS2 gene expression levels 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after R. solani inoculation. Mock was treated with RNase-free water. Rs-α-tubulin was used as the internal control for RT-qPCR. (E) RT-qPCR analysis of SWEET11 gene expression levels 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after R. solani inoculation. Mock was treated with RNase-free water. Ubiquitin was used as the internal control for RT-qPCR. (F) The transient assay showed that WRKY36, PIL15, and AOS2 both activated SWEET11 expression in an additive manner. The data in (D–F) are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3).

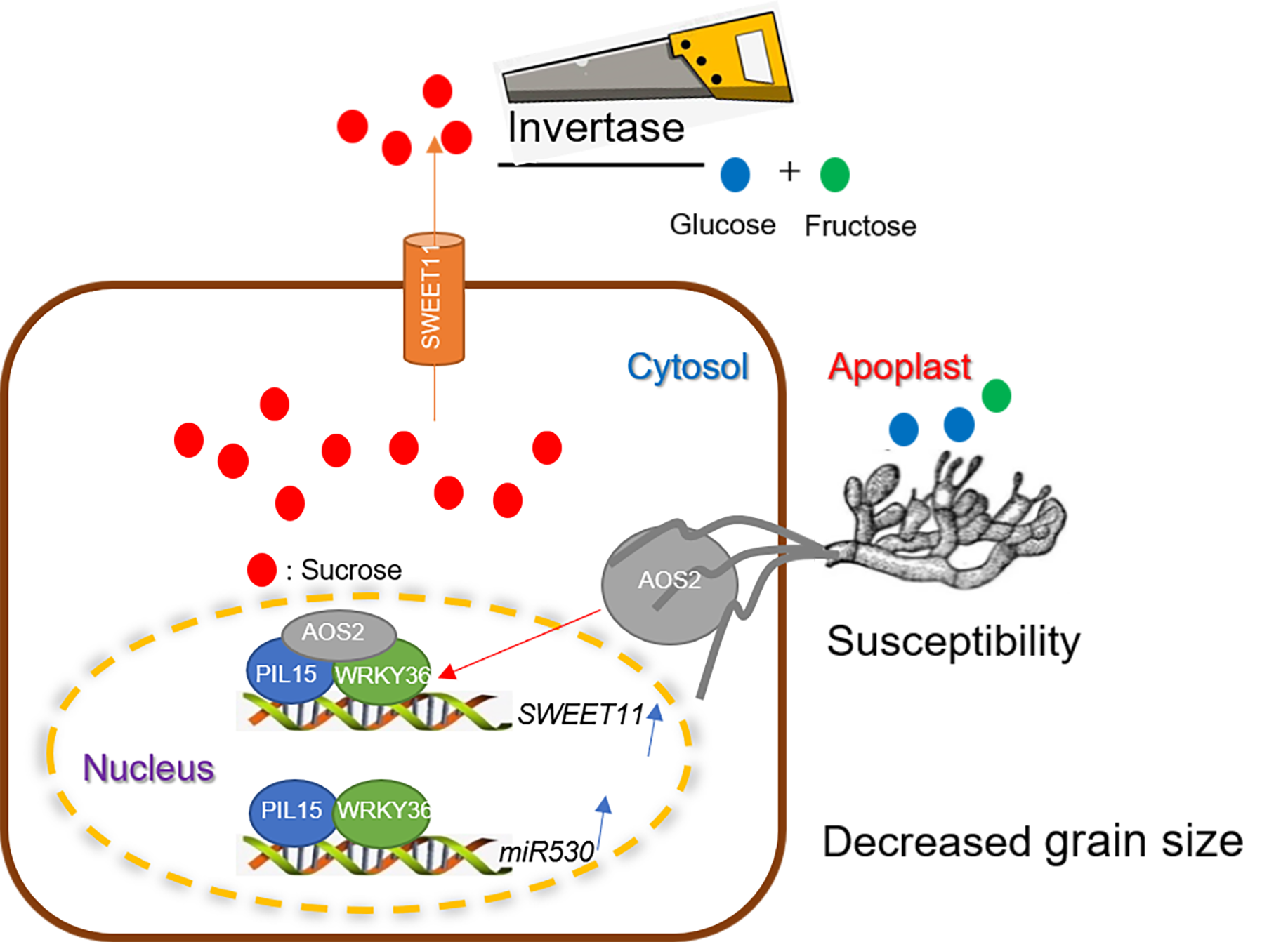

Figure 8.

Speculative model shows the the PIL15-WRKY36 transcription complex regulates sheath blight resistance and seed development in rice. (A) The AOS2 secreted by Rhizoctonia solani and WRKY36-PIL15 form a transcription factor complex, activating SWEET11 in the nucleus. Sucrose is exported from the cytoplasm to the extracellular vesicles through SWEET11, and is metabolized into glucose and fructose through cell wall invertase, which are utilized by Rhizoctonia solani. (B) The PIL15 and WRKY36 transcription factor complexes negatively regulate rice grain size and resistance to sheath blight by activating miR530 and SWEET11. If the activations of miR530 and SWEET11 by PIL15 and WRKY36 are inhibited, rice yield and sheath blight resistance are improved.

Figure 8.

Speculative model shows the the PIL15-WRKY36 transcription complex regulates sheath blight resistance and seed development in rice. (A) The AOS2 secreted by Rhizoctonia solani and WRKY36-PIL15 form a transcription factor complex, activating SWEET11 in the nucleus. Sucrose is exported from the cytoplasm to the extracellular vesicles through SWEET11, and is metabolized into glucose and fructose through cell wall invertase, which are utilized by Rhizoctonia solani. (B) The PIL15 and WRKY36 transcription factor complexes negatively regulate rice grain size and resistance to sheath blight by activating miR530 and SWEET11. If the activations of miR530 and SWEET11 by PIL15 and WRKY36 are inhibited, rice yield and sheath blight resistance are improved.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).