Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Effects of Metformin on Metabolism and the Brain

3. Effects of Metformin on Cognitive Function

4. Biovariance: A New Frontier in Personalized Medicine

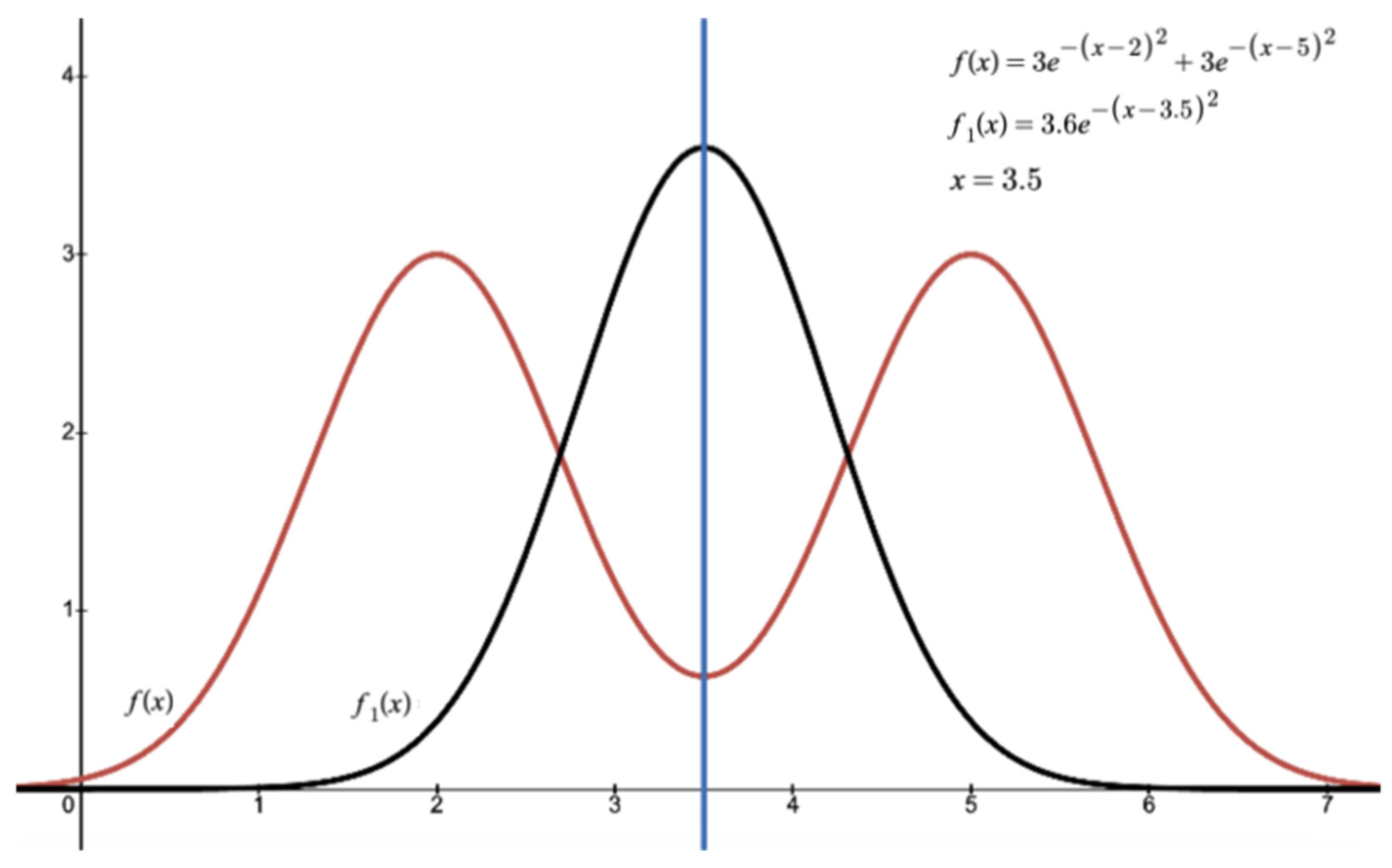

4.1. Role of Biovariance in Shaping Clinical Trial Design

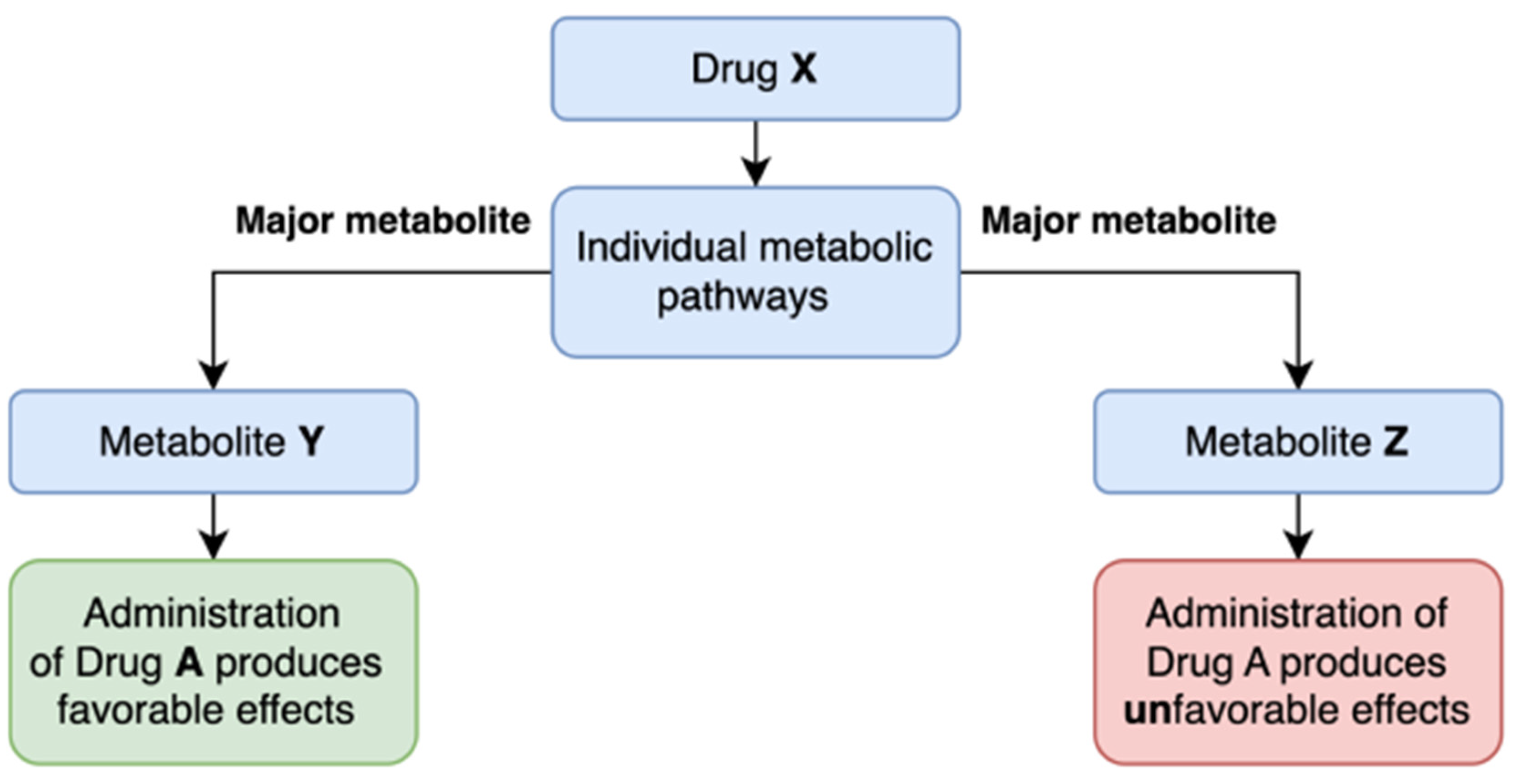

4.2. Metabolic Profiling Drugs. Metabolic Markers

5. Conclusions

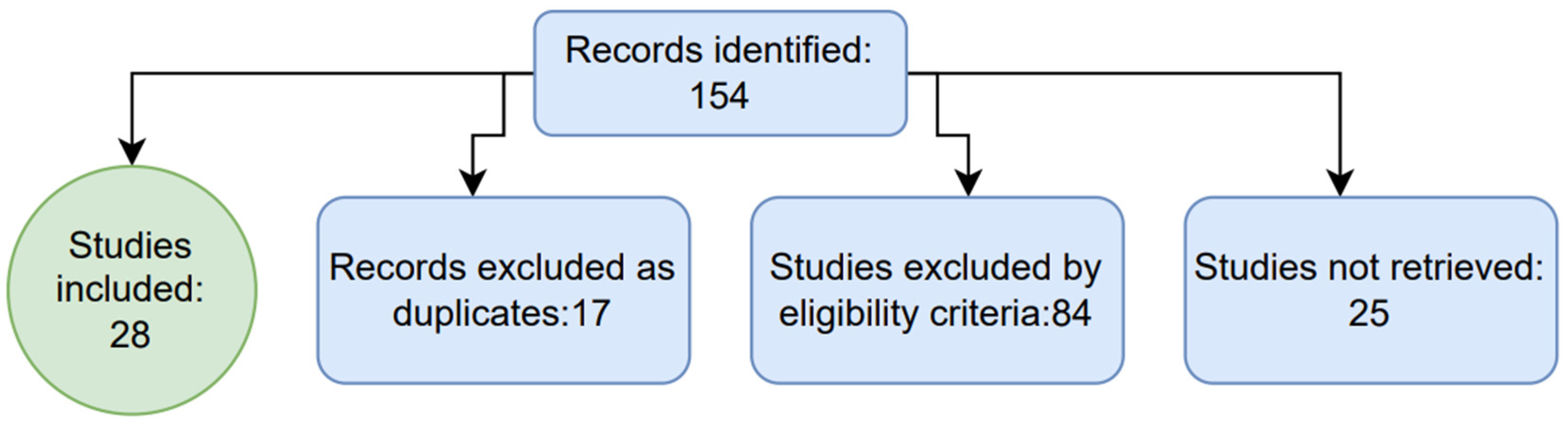

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, H., Huang, D., Zhou, H., Sima, X., Wu, Z., Sun, Y., Wang, L., Ruan, Y., Wu, Q., Wu, F., She, T., Chu, Y., Huang, Q., Ning, Z., & Zhang, H. (2022). Metformin: A promising drug for human cancers. Oncology letters, 24(1), 204. [CrossRef]

- Attia, G. M., Almouteri, M. M., & Alnakhli, F. T. (2023). Role of Metformin in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)-Related Infertility. Cureus, 15(8), e44493. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Z., & Li, Y. R. (2023). Cardiovascular Protection by Metformin: Latest Advances in Basic and Clinical Research. Cardiology, 148(4), 374–384. [CrossRef]

- Ziqubu, K., Mazibuko-Mbeje, S. E., Mthembu, S. X. H., Mabhida, S. E., Jack, B. U., Nyambuya, T. M., Nkambule, B. B., Basson, A. K., Tiano, L., & Dludla, P. V. (2023). Anti-Obesity Effects of Metformin: A Scoping Review Evaluating the Feasibility of Brown Adipose Tissue as a Therapeutic Target. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(3), 2227. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. Y., Wang, Z., & Pang, H. (2023). Role of metformin in inflammation. Molecular biology reports, 50(1), 789–798. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, I., Hollenberg, M. D., Ding, H., & Triggle, C. R. (2021). A Critical Review of the Evidence That Metformin Is a Putative Anti-Aging Drug That Enhances Healthspan and Extends Lifespan. Frontiers in endocrinology, 12, 718942. [CrossRef]

- Battini, V., Cirnigliaro, G., Leuzzi, R., Rissotto, E., Mosini, G., Benatti, B., Pozzi, M., Nobile, M., Radice, S., Carnovale, C., Dell'Osso, B., & Clementi, E. (2023). The potential effect of metformin on cognitive and other symptom dimensions in patients with schizophrenia and antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Frontiers in psychiatry, 14, 1215807. [CrossRef]

- Xue, M., Xu, W., Ou, Y. N., Cao, X. P., Tan, M. S., Tan, L., & Yu, J. T. (2019). Diabetes mellitus and risks of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 144 prospective studies. Ageing research reviews, 55, 100944. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Q., Wang, L., Wei, M. M., Xia, X. S., Tian, X. L., Cui, X. H., & Li, X. (2020). Relationship Between Type 2 Diabetes and White Matter Hyperintensity: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in endocrinology, 11, 595962. [CrossRef]

- LaMoia, T. E., & Shulman, G. I. (2021). Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Metformin Action. Endocrine reviews, 42(1), 77–96. [CrossRef]

- Herman, R., Kravos, N. A., Jensterle, M., Janež, A., & Dolžan, V. (2022). Metformin and Insulin Resistance: A Review of the Underlying Mechanisms behind Changes in GLUT4-Mediated Glucose Transport. International journal of molecular sciences, 23(3), 1264. [CrossRef]

- Kaneto, H., Kimura, T., Obata, A., Shimoda, M., & Kaku, K. (2021). Multifaceted Mechanisms of Action of Metformin Which Have Been Unraveled One after Another in the Long History. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(5), 2596. [CrossRef]

- Polianskyte-Prause, Z., Tolvanen, T. A., Lindfors, S., Dumont, V., Van, M., Wang, H., Dash, S. N., Berg, M., Naams, J. B., Hautala, L. C., Nisen, H., Mirtti, T., Groop, P. H., Wähälä, K., Tienari, J., & Lehtonen, S. (2019). Metformin increases glucose uptake and acts renoprotectively by reducing SHIP2 activity. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 33(2), 2858–2869. [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen S. (2020). SHIPping out diabetes-Metformin, an old friend among new SHIP2 inhibitors. Acta physiologica (Oxford, England), 228(1), e13349. [CrossRef]

- Graham, G. G., Punt, J., Arora, M., Day, R. O., Doogue, M. P., Duong, J. K., Furlong, T. J., Greenfield, J. R., Greenup, L. C., Kirkpatrick, C. M., Ray, J. E., Timmins, P., & Williams, K. M. (2011). Clinical pharmacokinetics of metformin. Clinical pharmacokinetics, 50(2), 81–98. [CrossRef]

- Sun, M. L., Liu, F., Yan, P., Chen, W., & Wang, X. H. (2023). Effects of food on pharmacokinetics and safety of metformin hydrochloride tablets: A meta-analysis of pharmacokinetic, bioavailability, or bioequivalence studies. Heliyon, 9(7), e17906. [CrossRef]

- Ezzamouri, B., Rosario, D., Bidkhori, G., Lee, S., Uhlen, M., & Shoaie, S. (2023). Metabolic modelling of the human gut microbiome in type 2 diabetes patients in response to metformin treatment. NPJ systems biology and applications, 9(1), 2. [CrossRef]

- Induri, S. N. R., Kansara, P., Thomas, S. C., Xu, F., Saxena, D., & Li, X. (2022). The Gut Microbiome, Metformin, and Aging. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 62, 85–108. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., & Hu, N. (2020). Effects of Metformin on the Gut Microbiota in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity : targets and therapy, 13, 5003–5014. [CrossRef]

- Elbere, I., Silamikelis, I., Dindune, I. I., Kalnina, I., Ustinova, M., Zaharenko, L., Silamikele, L., Rovite, V., Gudra, D., Konrade, I., Sokolovska, J., Pirags, V., & Klovins, J. (2020). Baseline gut microbiome composition predicts metformin therapy short-term efficacy in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes patients. PloS one, 15(10), e0241338. [CrossRef]

- Thinnes, A., Westenberger, M., Piechotta, C., Lehto, A., Wirth, F., Lau, H., & Klein, J. (2021). Cholinergic and metabolic effects of metformin in mouse brain. Brain research bulletin, 170, 211–217. [CrossRef]

- Łabuzek, K., Suchy, D., Gabryel, B., Bielecka, A., Liber, S., & Okopień, B. (2010). Quantification of metformin by the HPLC method in brain regions, cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of rats treated with lipopolysaccharide. Pharmacological reports : PR, 62(5), 956–965. [CrossRef]

- Mortby, M. E., Janke, A. L., Anstey, K. J., Sachdev, P. S., & Cherbuin, N. (2013). High "normal" blood glucose is associated with decreased brain volume and cognitive performance in the 60s: the PATH through life study. PloS one, 8(9), e73697. [CrossRef]

- Xue, M., Xu, W., Ou, Y. N., Cao, X. P., Tan, M. S., Tan, L., & Yu, J. T. (2019). Diabetes mellitus and risks of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 144 prospective studies. Ageing research reviews, 55, 100944. [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, M. J., Khan, S. K., Pappachan, J. M., & Jeeyavudeen, M. S. (2023). Diabetes and cognitive function: An evidence-based current perspective. World journal of diabetes, 14(2), 92–109. [CrossRef]

- Dao, L., Choi, S., & Freeby, M. (2023). Type 2 diabetes mellitus and cognitive function: understanding the connections. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity, 30(1), 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Cao, F., Yang, F., Li, J., Guo, W., Zhang, C., Gao, F., Sun, X., Zhou, Y., & Zhang, W. (2024). The relationship between diabetes and the dementia risk: a meta-analysis. Diabetology & metabolic syndrome, 16(1), 101. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. Y., Wang, Z., & Pang, H. (2023). Role of metformin in inflammation. Molecular biology reports, 50(1), 789–798. [CrossRef]

- Petrasca, A., Hambly, R., Kearney, N., Smith, C. M., Pender, E. K., Mac Mahon, J., O'Rourke, A. M., Ismaiel, M., Boland, P. A., Almeida, J. P., Kennedy, C., Zaborowski, A., Murphy, S., Winter, D., Kirby, B., & Fletcher, J. M. (2023). Metformin has anti-inflammatory effects and induces immunometabolic reprogramming via multiple mechanisms in hidradenitis suppurativa. The British journal of dermatology, 189(6), 730–740. [CrossRef]

- Buczyńska, A., Sidorkiewicz, I., Krętowski, A. J., & Adamska, A. (2024). Examining the clinical relevance of metformin as an antioxidant intervention. Frontiers in pharmacology, 15, 1330797. [CrossRef]

- Manica, D., Sandri, G., da Silva, G. B., Manica, A., da Silva Rosa Bonadiman, B., Dos Santos, D., Flores, É. M. M., Bolzan, R. C., Barcelos, R. C. S., Tomazoni, F., Suthovski, G., Bagatini, M. D., & Benvegnú, D. M. (2023). Evaluation of the effects of metformin on antioxidant biomarkers and mineral levels in patients with type II diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study. Journal of diabetes and its complications, 37(7), 108497. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J. J., Deedwania, P., Acharya, T., Aguilar, D., Bhatt, D. L., Chyun, D. A., Di Palo, K. E., Golden, S. H., Sperling, L. S., & American Heart Association Diabetes Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Hypertension (2022). Comprehensive Management of Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 145(9), e722–e759. [CrossRef]

- Dal Canto, E., Ceriello, A., Rydén, L., Ferrini, M., Hansen, T. B., Schnell, O., Standl, E., & Beulens, J. W. (2019). Diabetes as a cardiovascular risk factor: An overview of global trends of macro and micro vascular complications. European journal of preventive cardiology, 26(2_suppl), 25–32. [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Providencia, R., Jiang, W., Liu, M., Yu, L., Gu, C., Chang, A. C. Y., & Ma, H. (2022). Association of Metformin with the Mortality and Incidence of Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Pre-existing Cardiovascular Diseases. Drugs, 82(3), 311–322. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y., Xie, H., Liu, Y., Gao, P., Yang, X., & Shen, Z. (2019). Effect of metformin on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with coronary artery diseases: a systematic review and an updated meta-analysis. Cardiovascular diabetology, 18(1), 96. [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, T., Pafundi, P. C., Galiero, R., Rinaldi, L., Caturano, A., Vetrano, E., Aprea, C., Albanese, G., Di Martino, A., Ricozzi, C., Imbriani, S., & Sasso, F. C. (2020). Can Metformin Exert as an Active Drug on Endothelial Dysfunction in Diabetic Subjects?. Biomedicines, 9(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Ameen, O., Samaka, R. M., & Abo-Elsoud, R. A. A. (2022). Metformin alleviates neurocognitive impairment in aging via activation of AMPK/BDNF/PI3K pathway. Scientific reports, 12(1), 17084. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Yuan, J., Han, J., Hu, W., Li, L., Zhang, L., ... & Wang, Y. (2021). Long-Term Use of Metformin Is Associated With Reduced Risk of Cognitive Impairment With Alleviation of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Burden in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 13, 773797. [CrossRef]

- Samaras, K., Makkar, S., Crawford, J. D., Kochan, N. A., Wen, W., Draper, B., ... & Sachdev, P. S. (2020). Metformin Use Is Associated With Slowed Cognitive Decline and Reduced Incident Dementia in Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: The Sydney Memory and Ageing Study. Diabetes Care, 43(11), 2691–2701. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., Brinton, R. D., Chen, Z., Farland, L. V., Klimentidis, Y., Migrino, R., ... & Zhou, J. J. (2022). Use of oral diabetes medications and the risk of incident dementia in U.S. veterans aged ≥60 years with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, 10(5), e002894. [CrossRef]

- Hui, S. C., Chan, J. C., Ma, R. C., Chow, E. Y., Tang, C., & Lam, V. C. (2024). Metformin use is associated with lower risks of dementia, anxiety, and depression: The Hong Kong Diabetes Study. Journal of Diabetes Research, 2024, 377322485.

- Tang, H., Guo, J., Shaaban, C. E., Feng, Z., Wu, Y., ... & Bian, J. (2024). Heterogeneous treatment effects of metformin on risk of dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes: A longitudinal observational study. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 20(2), 975–985. [CrossRef]

- Defo, A. K., Bakula, V., Pisaturo, A., Labos, C., Wing, S. S., & Daskalopoulou, S. S. (2024). Diabetes, antidiabetic medications and risk of dementia: A systematic umbrella review and meta-analysis. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism, 26(2), 441-462. [CrossRef]

- Doran, W., Tunnicliffe, L., Muzambi, R., Rentsch, C. T., Bhaskaran, K., & Warren-Gash, C. (2024). Incident dementia risk among patients with type 2 diabetes receiving metformin versus alternative oral glucose-lowering therapy: An observational cohort study using UK primary healthcare records. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, 12(1), e003548. [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z., Feng, J., Qi, Q., Dong, Y., Xiao, Y., Xie, X., Meng, N., Chen, H., Zhang, W., & Lv, P. (2021). Long-term use of metformin is associated with reduced risk of cognitive impairment with alleviation of cerebral small vessel disease burden in patients with type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 13, 773797. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-Q., Li, W.-S., Liu, Z., Zhang, H.-L., Ba, Y.-G., & Zhang, R.-X. (2020). Metformin therapy and cognitive dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore), 99(10), e19378. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B., Su, B., Ahmadi-Abhari, S., Kapogiannis, D., Tzoulaki, I., Riboli, E., & Middleton, L. (2023). Dementia risk in patients with type 2 diabetes: Comparing metformin with no pharmacological treatment. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 19(12), 5681-5689. [CrossRef]

- Rosell-Díaz, M., & Fernández-Real, J. M. (2024). Metformin, cognitive function, and changes in the gut microbiome. Endocrine Reviews, 45(2), 210–226. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S. Y., Kim, E. W., Park, S. J., Phillips, B. U., Jeong, J., Kim, H., ... & Kim, E. (2024). Reconsidering repurposing: long-term metformin treatment impairs cognition in Alzheimer's model mice. Translational Psychiatry, 14(1), 34. [CrossRef]

- Shao, T., Huang, J., Zhao, Y., Wang, W., Tian, X., Hei, G., ... & Wu, R. (2023). Metformin improves cognitive impairment in patients with schizophrenia: associated with enhanced functional connectivity of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Translational Psychiatry, 13, 315. [CrossRef]

- Alnaaim, S. A., Al-Kuraishy, H. M., Al-Gareeb, A. I., Ali, N. H., Alexiou, A., Papadakis, M., ... & Batiha, G. E. (2023). New insights on the potential anti-epileptic effect of metformin: Mechanistic pathway. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 27(24), 3953-3965. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Sarangi, S. C., & Tripathi, M. (2022). A review on role of metformin as a potential drug for epilepsy treatment and modulation of epileptogenesis. Seizure, 101, 253-261. [CrossRef]

- Malazy, O. T., Bandarian, F., Qorbani, M., Mohseni, S., Mirsadeghi, S., Peimani, M., & Larijani, B. (2022). The effect of metformin on cognitive function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 36(6), 666-679. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y., & Xie, X. (2023). The association between metformin use and risk of developing severe dementia among AD patients with type 2 diabetes. Biomedicines, 11(11), 2935. [CrossRef]

- Ha, J., Choi, D.-W., Kim, K. J., Cho, S. Y., Kim, H., Kim, K. Y., Koh, Y., Nam, C. M., & Kim, E. (2021). Association of metformin use with Alzheimer's disease in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a population-based nested case-control study. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 24069. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-H., Tsai, Y.-F., Lee, C. B., Gau, S.-Y., Tsai, T.-H., Chung, N.-J., & Lee, C.-Y. (2023). The correlation between metformin use and incident dementia in patients with new-onset diabetes mellitus: A population-based study. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 13(5), 738. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K. H., Chang, Y. L., Gau, S. Y., Tsai, T. H., & Lee, C. Y. (2022). Dose-Response Association of Metformin with Parkinson's Disease Odds in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Pharmaceutics, 14(5), 946. [CrossRef]

- Newby, D., Linden, A. B., Fernandes, M., Molero, Y., Winchester, L., Sproviero, W., ... & Nevado-Holgado, A. J. (2022). Comparative effect of metformin versus sulfonylureas with dementia and Parkinson's disease risk in U.S. patients over 50 with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, 10(5), e003036. [CrossRef]

- Ping, F., Jiang, N., & Li, Y. (2020). Association between metformin and neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care, 8(1), e001370. [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, S., Raei Dehaghi, G., Ghahri Lalaklou, Z., Beig Verdi, H., Emami, D., & Dalvandi, B. (2023). Metformin attenuates white matter microstructural changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology Letters, 3(2), 39. [CrossRef]

- Agostini, F., Masato, A., Bubacco, L., & Bisaglia, M. (2021). Metformin Repurposing for Parkinson Disease Therapy: Opportunities and Challenges. International journal of molecular sciences, 23(1), 398. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, Y. K., Go, J., Park, H. Y., Choi, Y. K., Seo, Y. J., Choi, J. H., Rhee, M., Lee, T. G., Lee, C. H., & Kim, K. S. (2020). Metformin regulates astrocyte reactivity in Parkinson's disease and normal aging. Neuropharmacology, 175, 108173. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., Li, Z., Shi, X., Ding, J., & Wang, X. (2023). Metformin attenuates white matter injury and cognitive impairment induced by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 43(2 Suppl), 78–94. [CrossRef]

- Rabieipoor, S., Zare, M., Ettcheto, M., Camins, A., & Javan, M. (2023). Metformin restores cognitive dysfunction and histopathological deficits in an animal model of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Heliyon, 9(7), e17873. [CrossRef]

- Baradaran, Z., Vakilian, A., Zare, M., Hashemzehi, M., Hosseini, M., Dinpanah, H., & Beheshti, F. (2021). Metformin improved memory impairment caused by chronic ethanol consumption: Role of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Behavioral Brain Research, 411, 113399. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., Zhou, Y., Ling, P., Feng, X., Luo, S., Zheng, X., Little, P. J., Xu, S., & Weng, J. (2021). Metformin in cardiovascular diabetology: a focused review of its impact on endothelial function. Theranostics, 11(19), 9376–9396. [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, T., Pafundi, P. C., Galiero, R., Rinaldi, L., Caturano, A., Vetrano, E., & Sasso, F. C. (2021). Can metformin exert as an active drug on endothelial dysfunction in diabetic subjects? Biomedicines, 9(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Aylor, K. W., Chai, W., Barrett, E. J., & Liu, Z. (2022). Metformin prevents endothelial oxidative stress and microvascular insulin resistance during obesity development in male rats. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 322(3), E293-E306. [CrossRef]

- Paridari, P., Jabermoradi, S., Gholamzadeh, R., Vazifekhah, S., Vazirizadeh-Mahabadi, M., Roshdi Dizaji, S., & Yousefifard, M. (2023). Can metformin use reduce the risk of stroke in diabetic patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome, 17(2), 102721. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N., Singh, R., Kamran, S., Babu, B., Sivasankaran, S., Joseph, S., & Shuaib, A. (2022). Chronic metformin treatment and outcome following acute stroke. Frontiers in Neurology, 13, 849607. [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.-J., Liu, Z., Chao, B.-H., Yan, F., Ma, L., Cao, L., & Ji, X.-M. (2022). Metformin use is associated with low risk of case fatality and disability rates in first-ever stroke patients with type 2 diabetes. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease, 13, 20406223221076894. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. M., Zong, H. C., Qi, Y. B., Chang, L. L., Gao, Y. N., Zhou, T., Yin, T., Liu, M., Pan, K. J., Chen, W. G., Guo, H. R., Guo, F., Peng, Y. M., Wang, M., Feng, L. Y., Zang, Y., Li, Y., & Li, J. (2023). Anxiolytic effect of antidiabetic metformin is mediated by AMPK activation in mPFC inhibitory neurons. Molecular psychiatry, 28(9), 3955–3965. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zhang, B., Liu, W. X., Lu, K., Pan, H., Wang, T., Oh, C. D., Yi, D., Huang, J., Zhao, L., Ning, G., Xing, C., Xiao, G., Liu-Bryan, R., Feng, S., & Chen, D. (2020). Metformin limits osteoarthritis development and progression through activation of AMPK signalling. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 79(5), 635–645. [CrossRef]

- Apostolova, N., Iannantuoni, F., Gruevska, A., Muntane, J., Rocha, M., & Victor, V. M. (2020). Mechanisms of action of metformin in type 2 diabetes: Effects on mitochondria and leukocyte-endothelium interactions. Redox biology, 34, 101517. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rodríguez, S., de Pablos-Velasco, P., & Calbet, J. A. L. (2020). Mitochondrial Complex I Inhibition by Metformin: Drug-Exercise Interactions. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM, 31(4), 269–271. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J., Wang, X., Ye, X., Ares, I., Lopez-Torres, B., Martínez, M., Martínez-Larrañaga, M. R., Wang, X., Anadón, A., & Martínez, M. A. (2022). Mitochondria as an important target of metformin: The mechanism of action, toxic and side effects, and new therapeutic applications. Pharmacological research, 177, 106114. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X., Li, X., Yang, W., Liao, W., Shen, J. Z., Ai, W., Pan, Q., Sun, Y., Zhang, K., Zhang, R., Qiu, Y., Dai, Q., Zheng, H., & Guo, S. (2021). Metformin Targets Foxo1 to Control Glucose Homeostasis. Biomolecules, 11(6), 873. [CrossRef]

- Cao, G., Gong, T., Du, Y., Wang, Y., Ge, T., & Liu, J. (2022). Mechanism of metformin regulation in central nervous system: Progression and future perspectives. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 156, 113686. [CrossRef]

- Van Nostrand, J. L., Hellberg, K., Luo, E. C., Van Nostrand, E. L., Dayn, A., Yu, J., Shokhirev, M. N., Dayn, Y., Yeo, G. W., & Shaw, R. J. (2020). AMPK regulation of Raptor and TSC2 mediate metformin effects on transcriptional control of anabolism and inflammation. Genes & development, 34(19-20), 1330–1344. [CrossRef]

- Emwas, A. H., Szczepski, K., Al-Younis, I., Lachowicz, J. I., & Jaremko, M. (2022). Fluxomics - New Metabolomics Approaches to Monitor Metabolic Pathways. Frontiers in pharmacology, 13, 805782. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D. R., Patel, R., Kirsch, D. G., Lewis, C. A., Vander Heiden, M. G., & Locasale, J. W. (2021). Metabolomics in cancer research and emerging applications in clinical oncology. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 71(4), 333–358. [CrossRef]

- Alarcon-Barrera, J. C., Kostidis, S., Ondo-Mendez, A., & Giera, M. (2022). Recent advances in metabolomics analysis for early drug development. Drug discovery today, 27(6), 1763–1773. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Covarrubias, V., Martínez-Martínez, E., & Del Bosque-Plata, L. (2022). The Potential of Metabolomics in Biomedical Applications. Metabolites, 12(2), 194. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Guo, Y., Wrighton, S. A., Cooke, G. E., & Sadee, W. (2011). Intronic polymorphism in CYP3A4 affects hepatic expression and response to statin drugs. The pharmacogenomics journal, 11(4), 274–286. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S. F., Xue, C. C., Yu, X. Q., Li, C., & Wang, G. (2007). Clinically important drug interactions potentially involving mechanism-based inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4 and the role of therapeutic drug monitoring. Therapeutic drug monitoring, 29(6), 687–710. [CrossRef]

- Zhou S. F. (2009). Polymorphism of human cytochrome P450 2D6 and its clinical significance: Part I. Clinical pharmacokinetics, 48(11), 689–723. [CrossRef]

| Ref. No. | Study Title | Objective | Methodoly | Conclusion |

| [38] | Long-Term Use of Metformin Is Associated With Reduced Risk of Cognitive Impairment With Alleviation of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Burden in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes | Evaluate the relationship between metformin use, cognitive impairment, and cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) in type 2 diabetes patients | Cross-sectional study of patients with type 2 diabetes; | Long-term metformin use was associated with reduced cognitive decline |

| [39] | Metformin Use Is Associated With Slowed Cognitive Decline and Reduced Incident Dementia in Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: The Sydney Memory and Ageing Study | Evaluate if metformin use in older adults with type 2 diabetes is linked to a slower cognitive decline and lower incidence of dementia. | Prospective study comparing metformin users to non-users and non-diabetics over 6 years | Metformin users showed significantly slower decline in global cognition and executive function compared to non-users. Metformin also reduced dementia risk compared to non-users |

| [46] | Metformin Therapy and Cognitive Dysfunction in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review | Assessing the association between metformin therapy and cognitive dysfunction in type 2 diabetes patients | Meta-analysis of observational studies | Metformin therapy is linked to a reduced risk of neurodegenerative diseases, although effects vary based on treatment duration |

| [60] | Metformin Attenuates White Matter Microstructural Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease | Examine metformin’s effect on white matter microstructural integrity in non-demented diabetic individuals | Study of non-demented diabetic subjects, divided into metformin users and non-users | Metformin users showed higher fractional anisotropy (FA) in the left hippocampal cingulum and right internal capsule, suggesting reduced neurodegeneration compared to non-users. |

| [48] | Metformin, Cognitive Function, and Changes in the Gut Microbiome | To explore the impact of metformin on cognitive function and gut microbiome in T2DM | Review of human studies, focusing on microbiome changes, cognitive function, and metabolic implications related to metformin | Metformin was shown to partially restore gut dysbiosis related to diabetes and may reduce dementia risk, although study results were not entirely consistent. |

| [40] | Use of Oral Diabetes Medications and the Risk of Incident Dementia in U.S. Veterans Aged ≥60 Years With Type 2 Diabetes | Assess dementia risk among veterans with type 2 diabetes using different drugs, including metformin | Observational study. Dementia risk comparison among those on metformin, sulfonylurea (SU), or thiazolidinedione (TZD) | Metformin alone had a moderate protective effect against dementia |

| [63] | Metformin Attenuates White Matter Injury and Cognitive Impairment Induced by Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion | Examine metformin's impact on white matter integrity and cognitive impairment under chronic hypoperfusion conditions | Mouse model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion | Metformin reduced white matter damage and improved cognitive function by preserving oligodendrocyte function |

| [58] | Comparative Effect of Metformin Versus Sulfonylureas With Dementia and Parkinson's Disease Risk in U.S. Patients Over 50 With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | To assess the dementia and Parkinson's disease risks in older adults with type 2 diabetes (metformin compared to sulfonylureas) | Study on metformin users and sulfonylurea users over a 5-year follow-up | MET users had a lower risk of all-cause dementia, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular dementia compared to SU users.No significant difference for Parkinson's disease. |

| [53] | The Effect of Metformin on Cognitive Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis | Assess the relationship between metformin therapy and cognitive performance | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 studies | Metformin therapy showed no significant improvement in cognitive function or protection against dementia |

| [56] | The Correlation Between Metformin Use and Incident Dementia in Patients with New-Onset Diabetes Mellitus: A Population-Based Study | Examine the association between metformin use and dementia risk in patients with T2DM | Population-based study with 3- and 5-year follow-ups, categorizing patients by cumulative defined daily dose of metformin | Low-intensity metformin use was associated with a reduced dementia risk, while higher doses showed no protective effect. |

| [41] | Metformin Use Is Associated With Lower Risks of Dementia, Anxiety, and Depression: The Hong Kong Diabetes Study | Evaluate the effects of metformin on dementia, anxiety, and depression risks in diabetic patients | Retrospective cohort study | Metformin use was linked to significantly reduced risks of dementia, anxiety, and depression |

| [42] | Heterogeneous Treatment Effects of Metformin on Risk of Dementia in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Longitudinal Observational Study | To evaluate varied effects of metformin on dementia risk in T2DM patients | Longitudinal study on participants aged ≥50 with normal cognition at baseline | Metformin was linked to a reduced overall dementia risk, with varied effects across subgroups |

| [43] | Diabetes, Antidiabetic Medications and Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Umbrella Review and Meta-Analysis | Study the impact of diabetes and antidiabetic drugs on dementia risk | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 100 reviews and 27 cohort/case-control studies | MET, TZD, pioglitazone, GLP1 receptor agonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced dementia risk, particularly in Western populations. |

| [44] | Incident Dementia Risk Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Receiving Metformin Versus Alternative Oral Glucose-Lowering Therapy | To assess the dementia and mild cognitive impairment risks in T2DM patients using metformin versus other oral hypoglycemic drugs | Observational cohort study using UK primary healthcare records | Metformin use was associated with a 14% lower risk of dementia, with a more pronounced effect in patients under 80 |

| [45] | Long-Term Use of Metformin Is Associated With Reduced Risk of Cognitive Impairment With Alleviation of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Burden in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes | Investigate metformin’s effects on cognitive impairment and cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) in patients with type 2 diabetes | Case-control study | Metformin was associated with reduced cognitive impairment risk |

| [54] | The Association Between Metformin Use and Risk of Developing Severe Dementia Among AD Patients with Type 2 Diabetes | Study the link between metformin use and severe dementia risk in Alzheimer’s patients with T2DM | Cohort study. Compared metformin users and non-users over 3.6 years | No significant association between metformin use and reduced severe dementia risk |

| [49] | Reconsidering Repurposing: Long-Term Metformin Treatment Impairs Cognition in Alzheimer's Model Mice | Evaluate effects of long-term metformin treatment on cognitive function in Alzheimer’s model mice | The study examines the cognitive domains in transgenic and non-transgenic mice after 1 and 2 years of metformin treatment. | Metformin enhanced cognition in younger mice but impaired learning and memory in older AD model mice, increasing amyloid pathology and tau protein phosphorylation |

| [64] | Metformin Restores Cognitive Dysfunction and Histopathological Deficits in an Animal Model of Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease | Evaluate the therapeutic effects of metformin in a Alzheimer’s mice model | Alzheimer’s disease induced in mice using streptozotocin; treated with metformin, assessed with memory/cognitive tests and histopathological analysis | Metformin reduced neuroinflammation, preserved neuron integrity, and improved memory in Alzheimer's model mice |

| [59] | Association Between Metformin and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis | Evaluate the effect of metformin on the incidence of neurodegenerative diseases (NDs), including dementia and Parkinson disease | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 19 observational studies with 285,966 participants | Metformin showed no significant protective effect on overall NDs. However, metformin monotherapy was linked to an increased Parkinson’s risk compared to non-metformin |

| [65] | Metformin Improved Memory Impairment Caused by Chronic Ethanol Consumption | Investigate the protective effects of metformin on memory impairment and oxidative stress caused by chronic ethanol exposure in adolescent rats | Adolescent rats were given ethanol with varying doses of metformin; memory and biochemical markers were assessed | Metformin reduced oxidative stress and neuroinflammation, preserving memory function in ethanol-exposed rats |

| [47] | Dementia Risk in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Comparing Metformin With No Pharmacological Treatment | Compare dementia risk in T2DM patients treated with metformin versus those untreated | Observational cohort study | MET users showed a 12% lower dementia risk compared to untreated patients, with long-term users experiencing the greatest reduction |

| [50] | Metformin Improves Cognitive Impairment in Patients With Schizophrenia: Enhanced Functional Connectivity of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex | Investigate metformin’s effects on cognitive impairment and brain connectivity in patients with schizophrenia | Open-label, evaluator-blinded study on 72 schizophrenia patients randomized to metformin plus antipsychotics or antipsychotics alone | Metformin combined with antipsychotics improved cognitive scores significantly |

| [51] | New Insights on the Potential Anti-Epileptic Effect of Metformin: Mechanistic Pathway | Investigate metformin’s anti-seizure effects and underlying mechanisms | Review study analyzing metformin's influence on pathways like AMPK and mTOR | Metformin exerts anti-seizure effects by activating AMPK and inhibiting mTOR, promoting neuroprotection via BDNF expression and reducing inflammation |

| [52] | A Review on Role of Metformin as a Potential Drug for Epilepsy Treatment and Modulation of Epileptogenesis | Evaluate metformin’s potential in epilepsy treatment | Systematic review of preclinical and clinical evidence | Metformin shows anticonvulsant effects by activating AMPK, inhibiting mTOR, protecting the blood-brain barrier, and reducing oxidative stress |

| [55] | Association of Metformin Use With Alzheimer's Disease in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes: A Population-Based Nested Case-Control Study | Investigate the relationship between metformin use and Alzheimer’s disease risk in newly diagnosed T2DM patiens | Retrospective, case-control study of dementia-free type 2 diabetes patients from Korea’s National Health Insurance database | Metformin use was associated with an increased risk of AD, particularly in patients with longer diabetes duration and concurrent depression |

| [69] | Can Metformin Use Reduce the Risk of Stroke in Diabetic Patients? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis | To evaluate the impact of metformin on stroke risk in T2DM patients | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies, comparing stroke risk in metformin users versus other treatments | Metformin monotherapy was associated with a 34% reduction in stroke risk in randomized and cohort studies; |

| [70] | Chronic Metformin Treatment and Outcome Following Acute Stroke | Evaluate the impact of chronic metformin use on stroke severity, outcome, and mortality in diabetic stroke patients | Analysis of acute stroke patients from Qatar; outcomes were compared between diabetic metformin users and non-users | Diabetic patients on metformin had significantly improved 90-day functional outcomes and lower mortality compared to those on other hypoglycemics |

| [71] | Metformin Use Is Associated With Low Risk of Case Fatality and Disability Rates in First-Ever Stroke Patients With Type 2 Diabetes | Assess the impact of metformin on fatality and disability rates post-stroke in T2DM patients | Cohort study of 7,587 first-ever stroke patients in China, comparing metformin users vs. non-users over a 1-year follow-up | Metformin users had significantly lower in-hospital fatality rates and 12 month disability rates |

| Ref. No. | Hypothesized cellular target | Biological function | Metformin action |

| [72,73] | AMPK | AMPK is a crucial kinase for cellular energy homeostasis, acting as a sensor of cellular energy status. Under low-energy conditions, AMPK activates pathways that promote ATP production and suppresses anabolic processes to conserve energy. | Metformin activates AMPK in neuronal tissues, potentially providing neuroprotective effects by promoting autophagy, reducing oxidative stress, and supporting mitochondrial function. |

| [74] | GPD2 | GPD2 (Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 2) is a mitochondrial enzyme involved in redox transfer between the cytoplasm and mitochondria, particularly within the glycerophosphate shuttle. | Metformin modulates GPD2 activity indirectly through mitochondrial effects, promoting efficient glucose use. |

| [75,76] | Complex I | Complex I, also known as NADH oxidoreductase, is a key component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC). | Metformin inhibits Complex I, leading to controlled reductions in ATP, which activates AMPK. In neurons, this may promote protective autophagy, reduce oxidative damage, and improve mitochondrial efficiency |

| [77] | FOXO1 | FOXO1 is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of genes in many types of tissues, playing a central role in glucose homeostasis. | Metformin reduces FOXO1 activity by activating AMPK, which may limit neuronal apoptosis and enhance neurogenesis |

| [78] | BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) is a key neurotrophin essential for brain health, known for its role in promoting the growth, survival, and differentiation of neurons. | Metformin has been found to increase BDNF levels, supporting neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and potentially offering cognitive protection against neurodegenerative diseases. |

| [79] | mTORC1 | mTORC1 (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1) is a protein complex that regulates cell growth, protein synthesis, and nutrient sensing. It integrates signals related to nutrient availability, energy levels, and growth factors | Metformin inhibits mTORC1 activity, which may enhance autophagy in neurons and reduce pathological protein accumulation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).