Submitted:

01 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

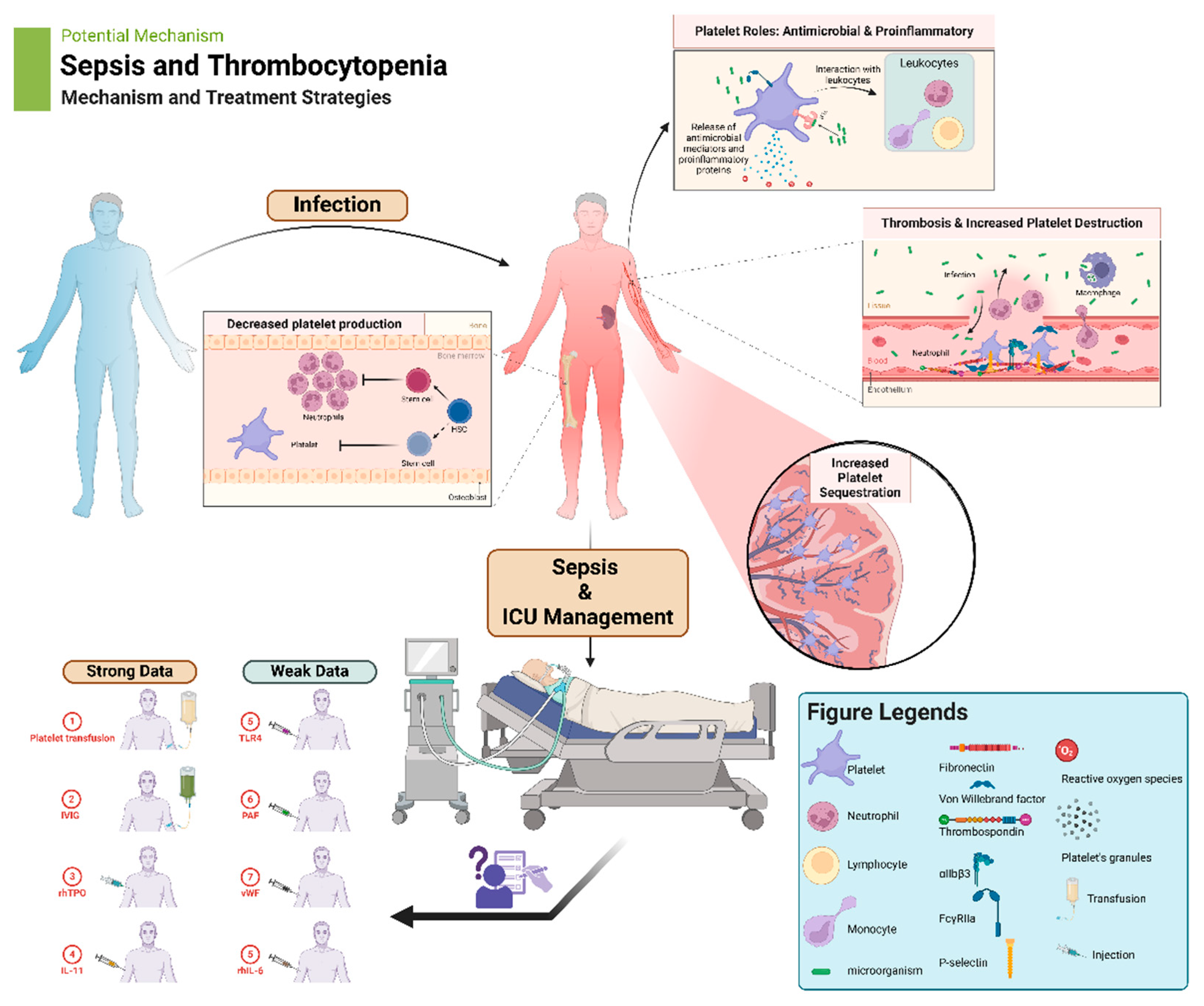

Platelets, traditionally known for their role in hemostasis, have emerged as key players in immune response and inflammation. Sepsis, a life-threatening condition characterized by systemic inflammation, often presents with thrombocytopenia, which at times can be significant. Platelets contribute to the inflammatory response by interacting with leukocytes, endothelial cells, and the innate immune system. However, excessive platelet activation and consumption can lead to thrombocytopenia and exacerbate the severity of sepsis. Understanding the multifaceted roles of platelets in sepsis is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies. Targeting platelet-mediated inflammatory responses and promoting platelet production may offer potential avenues for improving outcomes in septic patients with thrombocytopenia. Future research should focus on elucidating the mechanisms underlying platelet dysfunction in sepsis and exploring novel therapeutic approaches to optimize platelet function and mitigate inflammation. This review explores the intricate relationship between platelets, inflammation, and thrombosis in the context of sepsis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Additional Platelet Physiological Roles

3. Immune-Associated Platelet Functions in Sepsis

4. Clinical Implications

5. Management of Thrombocytopenia

5.1. Platelet Transfusions

5.2. Intravenous Immunoglobulins (IVIG)

5.3. Recombinant Human Thrombopoietin (rhTPO)

5.4. Recombinant Human IL-11

5.5. Recombinant Human IL-6

5.6. TLR4 Inhibition

5.7. Platelet-Activating Factor (PAF) Inhibition

5.8. Von Willebrand Factor (vWF)-Binding Function

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holinstat, M. Normal platelet function. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2017, 36, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Xiao, W.; Maitta, R.W. Steady increment of immature platelet fraction is suppressed by irradiation in single-donor platelet components during storage. PLoS One 2014, 9, e85465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repsold, L.; Joubert, A.M. Platelet Function, Role in Thrombosis, Inflammation, and Consequences in Chronic Myeloproliferative Disorders. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefrancais, E.; Ortiz-Munoz, G.; Caudrillier, A.; Mallavia, B.; Liu, F.; Sayah, D.M.; Thornton, E.E.; Headley, M.B.; David, T.; Coughlin, S.R.; et al. The lung is a site of platelet biogenesis and a reservoir for haematopoietic progenitors. Nature 2017, 544, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurden, A.; Nurden, P. Advances in our understanding of the molecular basis of disorders of platelet function. J Thromb Haemost 2011, 9 Suppl 1, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broos, K.; Feys, H.B.; De Meyer, S.F.; Vanhoorelbeke, K.; Deckmyn, H. Platelets at work in primary hemostasis. Blood Rev 2011, 25, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arman, M.; Krauel, K.; Tilley, D.O.; Weber, C.; Cox, D.; Greinacher, A.; Kerrigan, S.W.; Watson, S.P. Amplification of bacteria-induced platelet activation is triggered by FcgammaRIIA, integrin alphaIIbbeta3, and platelet factor 4. Blood 2014, 123, 3166–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, M. Cell biology. Beyond clotting: the powers of platelets. Science 2010, 328, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzey, B.D.; Tian, J.; Jensen, R.J.; Swanson, A.K.; Lees, J.R.; Lentz, S.R.; Stein, C.S.; Nieswandt, B.; Wang, Y.; Davidson, B.L.; et al. Platelet-mediated modulation of adaptive immunity. A communication link between innate and adaptive immune compartments. Immunity 2003, 19, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diacovo, T.G.; Puri, K.D.; Warnock, R.A.; Springer, T.A.; von Andrian, U.H. Platelet-mediated lymphocyte delivery to high endothelial venules. Science 1996, 273, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeaman, M.R.; Bayer, A.S. Antimicrobial peptides from platelets. Drug Resist Updat 1999, 2, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Q.; Yeaman, M.R.; Selsted, M.E. Antimicrobial peptides from human platelets. Infect Immun 2002, 70, 6524–6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, S.S.; McEver, R.P.; Weyrich, A.S.; Morrell, C.N.; Hoffman, M.R.; Arepally, G.M.; French, P.A.; Dauerman, H.L.; Becker, R.C.; Platelet Colloquium, P. Platelet functions beyond hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost 2009, 7, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.T.; Corken, A.; Ware, J. Platelets at the interface of thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer. Blood 2015, 126, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauel, K.; Potschke, C.; Weber, C.; Kessler, W.; Furll, B.; Ittermann, T.; Maier, S.; Hammerschmidt, S.; Broker, B.M.; Greinacher, A. Platelet factor 4 binds to bacteria, [corrected] inducing antibodies cross-reacting with the major antigen in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood 2011, 117, 1370–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greinacher, A.; Kohlmann, T.; Strobel, U.; Sheppard, J.A.; Warkentin, T.E. The temporal profile of the anti-PF4/heparin immune response. Blood 2009, 113, 4970–4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuhaus, F.C.; Baddiley, J. A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of D-alanyl-teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2003, 67, 686–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauel, K.; Weber, C.; Brandt, S.; Zahringer, U.; Mamat, U.; Greinacher, A.; Hammerschmidt, S. Platelet factor 4 binding to lipid A of Gram-negative bacteria exposes PF4/heparin-like epitopes. Blood 2012, 120, 3345–3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senchenkova, E.Y.; Ansari, J.; Becker, F.; Vital, S.A.; Al-Yafeai, Z.; Sparkenbaugh, E.M.; Pawlinski, R.; Stokes, K.Y.; Carroll, J.L.; Dragoi, A.M.; et al. Novel Role for the AnxA1-Fpr2/ALX Signaling Axis as a Key Regulator of Platelet Function to Promote Resolution of Inflammation. Circulation 2019, 140, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur, R.; Semple, J.W. Platelets as immune-sensing cells. Blood Adv 2016, 1, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallance, T.M.; Zeuner, M.T.; Williams, H.F.; Widera, D.; Vaiyapuri, S. Toll-Like Receptor 4 Signalling and Its Impact on Platelet Function, Thrombosis, and Haemostasis. Mediators Inflamm 2017, 2017, 9605894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andonegui, G.; Kerfoot, S.M.; McNagny, K.; Ebbert, K.V.; Patel, K.D.; Kubes, P. Platelets express functional Toll-like receptor-4. Blood 2005, 106, 2417–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Zhang, G.; Guo, L.; Li, X.A.; Morris, A.J.; Daugherty, A.; Whiteheart, S.W.; Smyth, S.S.; Li, Z. Platelets protect from septic shock by inhibiting macrophage-dependent inflammation via the cyclooxygenase 1 signalling pathway. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Xu, R.; Xie, P.; Liu, X.; Ling, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Z.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J. EGFR of platelet regulates macrophage activation and bacterial phagocytosis function. J Inflamm (Lond) 2024, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemetson, K.J. Platelets and pathogens. Cell Mol Life Sci 2010, 67, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, A.; Nandi, D.; Batra, H.; Singhal, R.; Annarapu, G.K.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Seth, T.; Dar, L.; Medigeshi, G.R.; Vrati, S.; et al. Platelet activation determines the severity of thrombocytopenia in dengue infection. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 41697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claushuis, T.A.M.; de Vos, A.F.; Nieswandt, B.; Boon, L.; Roelofs, J.; de Boer, O.J.; van 't Veer, C.; van der Poll, T. Platelet glycoprotein VI aids in local immunity during pneumonia-derived sepsis caused by gram-negative bacteria. Blood 2018, 131, 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutting, S.; Bender, M.; Nieswandt, B. Platelet GPVI: a target for antithrombotic therapy?! Trends Pharmacol Sci 2012, 33, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, M.; Handtke, S.; Palankar, R.; Wesche, J.; Kohler, T.P.; Kohler, C.; Gruel, Y.; Hammerschmidt, S.; Greinacher, A. Activated platelets kill Staphylococcus aureus, but not Streptococcus pneumoniae-The role of FcgammaRIIa and platelet factor 4/heparinantibodies. J Thromb Haemost 2020, 18, 1459–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.L.; Liu, D.Q.; Bian, Z.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zen, K. Down-regulation of platelet surface CD47 expression in Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection-induced thrombocytopenia. PLoS One 2009, 4, e7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; McDermott, P.; Schreiber, A.D. Characterization of the Fc gamma receptor on human platelets. Cell Immunol 1990, 128, 462–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, K.; Xie, F.; Gibson, A.W.; Edberg, J.C.; Kimberly, R.P.; Wu, J. Functional expression of IgA receptor FcalphaRI on human platelets. J Leukoc Biol 2008, 84, 1492–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindemann, S.; Tolley, N.D.; Dixon, D.A.; McIntyre, T.M.; Prescott, S.M.; Zimmerman, G.A.; Weyrich, A.S. Activated platelets mediate inflammatory signaling by regulated interleukin 1beta synthesis. J Cell Biol 2001, 154, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, V.; Slupsky, J.R.; Grafe, M.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Forster, R.; Muller-Berghaus, G.; Kroczek, R.A. CD40 ligand on activated platelets triggers an inflammatory reaction of endothelial cells. Nature 1998, 391, 591–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danese, S.; Katz, J.A.; Saibeni, S.; Papa, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Vecchi, M.; Fiocchi, C. Activated platelets are the source of elevated levels of soluble CD40 ligand in the circulation of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gut 2003, 52, 1435–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoub, D.; Hachem, A.; Theoret, J.F.; Gillis, M.A.; Mourad, W.; Merhi, Y. Enhanced levels of soluble CD40 ligand exacerbate platelet aggregation and thrombus formation through a CD40-dependent tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor-2/Rac1/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010, 30, 2424–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Conde, I.; Cruz, M.A.; Zhang, H.; Lopez, J.A.; Afshar-Kharghan, V. Platelet activation leads to activation and propagation of the complement system. J Exp Med 2005, 201, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.H.; Jenne, C.N.; Petri, B.; Chrobok, N.L.; Kubes, P. Nucleation of platelets with blood-borne pathogens on Kupffer cells precedes other innate immunity and contributes to bacterial clearance. Nat Immunol 2013, 14, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagasawa, T.; Nakayasu, C.; Rieger, A.M.; Barreda, D.R.; Somamoto, T.; Nakao, M. Phagocytosis by Thrombocytes is a Conserved Innate Immune Mechanism in Lower Vertebrates. Front Immunol 2014, 5, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer, J.; Esteban, M.A.; Rodriguez, A. Are thrombocytes and platelets true phagocytes? Microsc Res Tech 2002, 57, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koupenova, M.; Clancy, L.; Corkrey, H.A.; Freedman, J.E. Circulating Platelets as Mediators of Immunity, Inflammation, and Thrombosis. Circ Res 2018, 122, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Yoon, B.R.; Kim, H.Y.; Yoo, S.J.; Kang, S.W.; Lee, W.W. Activated Platelets Convert CD14(+)CD16(-) Into CD14(+)CD16(+) Monocytes With Enhanced FcgammaR-Mediated Phagocytosis and Skewed M2 Polarization. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 611133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carestia, A.; Kaufman, T.; Schattner, M. Platelets: New Bricks in the Building of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Front Immunol 2016, 7, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.R.; Ma, A.C.; Tavener, S.A.; McDonald, B.; Goodarzi, Z.; Kelly, M.M.; Patel, K.D.; Chakrabarti, S.; McAvoy, E.; Sinclair, G.D.; et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med 2007, 13, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carestia, A.; Kaufman, T.; Rivadeneyra, L.; Landoni, V.I.; Pozner, R.G.; Negrotto, S.; D'Atri, L.P.; Gomez, R.M.; Schattner, M. Mediators and molecular pathways involved in the regulation of neutrophil extracellular trap formation mediated by activated platelets. J Leukoc Biol 2016, 99, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrottmaier, W.C.; Kral-Pointner, J.B.; Salzmann, M.; Mussbacher, M.; Schmuckenschlager, A.; Pirabe, A.; Brunnthaler, L.; Kuttke, M.; Maier, B.; Heber, S.; et al. Platelet p110beta mediates platelet-leukocyte interaction and curtails bacterial dissemination in pneumococcal pneumonia. Cell Rep 2022, 41, 111614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.; Ganji, G.; Lemech, C.; Burris, H.A.; Han, S.W.; Swales, K.; Decordova, S.; DeYoung, M.P.; Smith, D.A.; Kalyana-Sundaram, S.; et al. A First-Time-in-Human Study of GSK2636771, a Phosphoinositide 3 Kinase Beta-Selective Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2017, 23, 5981–5992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyrich, A.S.; Zimmerman, G.A. Platelets: signaling cells in the immune continuum. Trends Immunol 2004, 25, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D. Bacteria-platelet interactions. J Thromb Haemost 2009, 7, 1865–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, J.R.; Foster, T.J.; Cox, D. The interaction of bacterial pathogens with platelets. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006, 4, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrigan, S.W.; Jakubovics, N.S.; Keane, C.; Maguire, P.; Wynne, K.; Jenkinson, H.F.; Cox, D. Role of Streptococcus gordonii surface proteins SspA/SspB and Hsa in platelet function. Infect Immun 2007, 75, 5740–5747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Seaghdha, M.; van Schooten, C.J.; Kerrigan, S.W.; Emsley, J.; Silverman, G.J.; Cox, D.; Lenting, P.J.; Foster, T.J. Staphylococcus aureus protein A binding to von Willebrand factor A1 domain is mediated by conserved IgG binding regions. FEBS J 2006, 273, 4831–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourbakos, A.; Yuan, Y.P.; Jenkins, A.L.; Travis, J.; Andrade-Gordon, P.; Santulli, R.; Potempa, J.; Pike, R.N. Activation of protease-activated receptors by gingipains from Porphyromonas gingivalis leads to platelet aggregation: a new trait in microbial pathogenicity. Blood 2001, 97, 3790–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Sharma, M.; Majumder, M.; Steier, W.; Sangal, A.; Kalawar, M. Thrombocytopenia in septic shock patients--a prospective observational study of incidence, risk factors and correlation with clinical outcome. Anaesth Intensive Care 2007, 35, 874–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderschueren, S.; De Weerdt, A.; Malbrain, M.; Vankersschaever, D.; Frans, E.; Wilmer, A.; Bobbaers, H. Thrombocytopenia and prognosis in intensive care. Crit Care Med 2000, 28, 1871–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S.; Ravi, S.; Budhathoki, R.; Arjyal, L.; Hamal, S.; Bista, A.; Khadka, S.; Uprety, D. Current understanding and future implications of sepsis-induced thrombocytopenia. Eur J Haematol 2021, 106, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Sharma, M.; Majumder, M.; Steier, W.; Sangal, A.; Kalawar, M. Thrombocytopenia in Septic Shock Patients—A Prospective Observational Study of Incidence, Risk Factors and Correlation with Clinical Outcome. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 2007, 35, 874–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Zarazúa, O.; González-Carrillo, P.L.; Vélez-Ramírez, L.N.; Alcocer-León, M.; Salceda-Muñoz, P.A.T.; Palomares-Anda, P.; Nava-Quirino, O.A.; Escalante-Martínez, N.; Sánchez-Guzmán, S.; Mondragón, J.D. Survival in septic shock associated with thrombocytopenia. Heart & Lung 2021, 50, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yin, W.; Li, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zou, T. Association between minimal decrease in platelet counts and outcomes in septic patients: a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad Sahu, D.; Wasnik, M.; Kannauje, P.K. Factors Influencing Corrected Count Increment After Platelet Transfusion in Thrombocytopenic Patients. Cureus 2023, 15, e46161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reizine, F.; Le Marec, S.; Le Meur, A.; Consigny, M.; Berteau, F.; Bodenes, L.; Geslain, M.; McQuilten, Z.; Le Niger, C.; Huntzinger, J.; et al. Prophylactic platelet transfusion response in critically ill patients: a prospective multicentre observational study. Critical Care 2023, 27, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reizine, F.; Le Marec, S.; Le Meur, A.; Consigny, M.; Berteau, F.; Bodenes, L.; Geslain, M.; McQuilten, Z.; Le Niger, C.; Huntzinger, J.; et al. Prophylactic platelet transfusion response in critically ill patients: a prospective multicentre observational study. Crit Care 2023, 27, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Fan, C.; He, S.; Chen, Y.; Xie, C. Impact of Platelet Transfusion Thresholds on Outcomes of Patients With Sepsis: Analysis of the MIMIC-IV Database. Shock 2022, 57, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Fan, C.; Ma, J.; Tang, C.; Chen, Y. Platelet Transfusion in Patients With Sepsis and Thrombocytopenia: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis Using a Large ICU Database. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 830177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, Z.; Xiao, W.; Hua, T.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, M. Efficacy and Safety of Recombinant Human Thrombopoietin on Sepsis Patients With Thrombocytopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Feng, T.; Xie, Y.; Huang, P.; Xie, H.; Tian, R.; Qian, B.; Wang, R. The effect of recombinant human thrombopoietin (rhTPO) on sepsis patients with acute severe thrombocytopenia: a study protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RESCUE trial). BMC Infectious Diseases 2019, 19, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platelet Transfusion: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the AABB. Annals of Internal Medicine 2015, 162, 205–213. [CrossRef]

- van Baarle, F.L.F.; van de Weerdt, E.K.; van der Velden, W.; Ruiterkamp, R.A.; Tuinman, P.R.; Ypma, P.F.; van den Bergh, W.M.; Demandt, A.M.P.; Kerver, E.D.; Jansen, A.J.G.; et al. Platelet Transfusion before CVC Placement in Patients with Thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med 2023, 388, 1956–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Q.; Pan, J.; Zhou, A. Platelet transfusion and mortality in patients with sepsis-induced thrombocytopenia: A propensity score matching analysis. Vox Sanguinis 2022, 117, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Belsher, J.; Yilmaz, M.; Afessa, B.; Winters, J.L.; Moore, S.B.; Hubmayr, R.D.; Gajic, O. Fresh-frozen plasma and platelet transfusions are associated with development of acute lung injury in critically ill medical patients. Chest 2007, 131, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Ness, P.M.; Takemoto, C.M.; Krishnamurti, L.; King, K.E.; Tobian, A.A.R. Platelet transfusions in platelet consumptive disorders are associated with arterial thrombosis and in-hospital mortality. Blood 2015, 125, 1470–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.H.; Neal, M.D.; Herman, J.H. Bacterial contamination of platelets for transfusion: strategies for prevention. Crit Care 2018, 22, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-Z.; Xia, R. Pro-inflammatory effects after platelet transfusion: a review. Vox Sanguinis 2020, 115, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, M.; Pati, S. Targeting repair of the vascular endothelium and glycocalyx after traumatic injury with plasma and platelet resuscitation. Matrix Biology Plus 2022, 14, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho-Tin-Noé, B.; Demers, M.; Wagner, D.D. How platelets safeguard vascular integrity. J Thromb Haemost 2011, 9 Suppl 1, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, A.; Youssef, D.; Mohammadi, A. Unusual Presentation of Corynebacterium Endocarditis in a Patient Without Conventional Risk Factors: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e54970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitink-Pollé, K.M.J.; Uiterwaal, C.; Porcelijn, L.; Tamminga, R.Y.J.; Smiers, F.J.; van Woerden, N.L.; Wesseling, J.; Vidarsson, G.; Laarhoven, A.G.; de Haas, M.; et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin vs observation in childhood immune thrombocytopenia: a randomized controlled trial. Blood 2018, 132, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.J.; Balthasar, J.P. Intravenous immunoglobulin mediates an increase in anti-platelet antibody clearance via the FcRn receptor. Thromb Haemost 2002, 88, 898–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsam, S.J.; Psaila, B.; Forestier, M.; Page, L.K.; Sloane, P.A.; Geyer, J.T.; Villarica, G.O.; Ruisi, M.M.; Gernsheimer, T.B.; Beer, J.H.; et al. Platelet production and platelet destruction: assessing mechanisms of treatment effect in immune thrombocytopenia. Blood 2011, 117, 5723–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhu, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, P.; Liu, K.-Y.; Zhang, X. The Combination of Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) and Low Does Recombinant Human Thrombopoietin (rhTPO) for the Management of Corticosteroid/IVIG Monotherapy-Resistant Immune Thrombocytopenia in Pregnancy. Blood 2023, 142, 1213–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, E.R.; Lee, V.; Rubinstein, A. Treatment of septic thrombocytopenia with immune globulin. Journal of Clinical Immunology 1991, 11, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzdorff, A.; Meyer, O.; Ostermann, H.; Kiefel, V.; Eberl, W.; Kühne, T.; Pabinger, I.; Rummel, M. Immune Thrombocytopenia - Current Diagnostics and Therapy: Recommendations of a Joint Working Group of DGHO, ÖGHO, SGH, GPOH, and DGTI. Oncology Research and Treatment 2018, 41, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, E.R.; Lee, V.; Rubinstein, A. Treatment of septic thrombocytopenia with immune globulin. J Clin Immunol 1991, 11, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincic, Z.; Skopec, B.; Rener, K.; Mavric, M.; Vovko, T.; Jereb, M.; Lukic, M. Severe immune thrombocytopenia in a critically ill COVID-19 patient. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 99, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S.; Du, J.; Cui, N.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.X.; Yue, M.; Wu, Y.X.; Yang, T.; Zhang, X.A.; et al. Clinical efficacy of immunoglobulin on the treatment of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. EBioMedicine 2023, 96, 104807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Sun, P.; Pei, R.; Lin, F.; Cao, H. Efficacy of IVIG therapy for patients with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Translational Medicine 2023, 21, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warkentin, T.E. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment and prevention of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: a review. Expert Review of Hematology 2019, 12, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, A.; Jones, C.G.; Pechauer, S.M.; Curtis, B.R.; Bougie, D.W.; Irani, M.S.; Bryant, B.J.; Alperin, J.B.; Deloughery, T.G.; Mulvey, K.P.; et al. IVIg for Treatment of Severe Refractory Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia. Chest 2017, 152, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuter, D.J. Managing thrombocytopenia associated with cancer chemotherapy. Oncology (Williston Park) 2015, 29, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Ren, J.; Wu, X.; Wang, G.; Gu, G.; Liu, S.; Wu, Y.; Hu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J. Recombinant human thrombopoietin improves platelet counts and reduces platelet transfusion possibility among patients with severe sepsis and thrombocytopenia: a prospective study. J Crit Care 2014, 29, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, Z.; Xiao, W.; Hua, T.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, M. Efficacy and Safety of Recombinant Human Thrombopoietin on Sepsis Patients With Thrombocytopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Jin, G.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Guo, L. Recombinant human thrombopoietin in critically ill patients with sepsis-associated thrombocytopenia: A clinical study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 98, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadhan-Raj, S.; Verschraegen, C.F.; Bueso-Ramos, C.; Broxmeyer, H.E.; Kudelkà, A.P.; Freedman, R.S.; Edwards, C.L.; Gershenson, D.; Jones, D.; Ashby, M.; et al. Recombinant human thrombopoietin attenuates carboplatin-induced severe thrombocytopenia and the need for platelet transfusions in patients with gynecologic cancer. Ann Intern Med 2000, 132, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, R.; Zou, P.; Hou, M.; Wu, D.; Shen, Z.; Lu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Niu, T.; et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of recombinant human thrombopoietin treatment in patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia. Int J Hematol 2012, 96, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Fan, Z.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, X.; He, L.; et al. Recombinant human thrombopoietin promotes hematopoietic reconstruction after severe whole body irradiation. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 12993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorner, A.J.; Goldman, S.J.; Keith, J.C., Jr. Interleukin-11. BioDrugs 1997, 8, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Williams, D.A. Interleukin-11: review of molecular, cell biology, and clinical use. Blood 1997, 89, 3897–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sands, B.E.; Bank, S.; Sninsky, C.A.; Robinson, M.; Katz, S.; Singleton, J.W.; Miner, P.B.; Safdi, M.A.; Galandiuk, S.; Hanauer, S.B.; et al. Preliminary evaluation of safety and activity of recombinant human interleukin 11 in patients with active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1999, 117, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, B.; Zhang, H.; Fu, H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Yin, J.; Wan, Y.; Shi, Y. Recombinant human interleukin-11 (IL-11) is a protective factor in severe sepsis with thrombocytopenia: A case-control study. Cytokine 2015, 76, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Williams, D.A. Interleukin-11: Review of Molecular, Cell Biology, and Clinical Use. Blood 1997, 89, 3897–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Park, D.W.; Moon, S.; Cho, H.J.; Park, J.H.; Seok, H.; Choi, W.S. Diagnostic and prognostic value of interleukin-6, pentraxin 3, and procalcitonin levels among sepsis and septic shock patients: a prospective controlled study according to the Sepsis-3 definitions. BMC Infect Dis 2019, 19, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ture, S.K.; Nieves-Lopez, B.; Blick-Nitko, S.K.; Maurya, P.; Livada, A.C.; Stahl, T.J.; Kim, M.; Pietropaoli, A.P.; Morrell, C.N. Thrombocytopenia Independently Leads to Changes in Monocyte Immune Function. Circulation Research 2024, 134, 970–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Shen, A.; Chen, Y.; Qi, Z. Rational Use of Tocilizumab in the Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. Clinical Drug Investigation 2020, 40, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interleukin-6 Receptor Antagonists in Critically Ill Patients with Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine 2021, 384, 1491–1502. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zeng, H.; Chen, H.; Fan, L.; Xu, C.; Huang, H.; Tang, T.; Li, M. Current knowledge of thrombocytopenia in sepsis and COVID-19. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Devalaraja, M.; Baeres, F.M.M.; Engelmann, M.D.M.; Hovingh, G.K.; Ivkovic, M.; Lo, L.; Kling, D.; Pergola, P.; Raj, D.; et al. IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherosclerotic risk (RESCUE): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. The Lancet 2021, 397, 2060–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, J.B.; Pimentel-Nunes, P.; Roncon-Albuquerque, R.; Leite-Moreira, A. The role of lipopolysaccharide/toll-like receptor 4 signaling in chronic liver diseases. Hepatol Int 2010, 4, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nature Immunology 2010, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, G. TLR4 inhibitor alleviates sepsis-induced organ failure by inhibiting platelet mtROS production, autophagy, and GPIIb/IIIa expression. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2022, 54, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, R.; Speck, E.R.; Kim, M.; Crow, A.R.; Bang, K.W.A.; Nestel, F.P.; Ni, H.; Lazarus, A.H.; Freedman, J.; Semple, J.W. Platelet Toll-like receptor expression modulates lipopolysaccharide-induced thrombocytopenia and tumor necrosis factor-α production in vivo. Blood 2006, 107, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnevale, R.; Cammisotto, V.; Bartimoccia, S.; Nocella, C.; Castellani, V.; Bufano, M.; Loffredo, L.; Sciarretta, S.; Frati, G.; Coluccia, A.; et al. Toll-Like Receptor 4-Dependent Platelet-Related Thrombosis in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Circulation Research 2023, 132, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schattner, M. Platelet TLR4 at the crossroads of thrombosis and the innate immune response. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2019, 105, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchiya, R.; Kyotani, K.; Scott, M.A.; Nishizono, K.; Ashida, Y.; Mochizuki, T.; Kitao, S.; Yamada, T.; Kobayashi, K. Role of platelet activating factor in development of thrombocytopenia and neutropenia in dogs with endotoxemia. Am J Vet Res 1999, 60, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, D.P.; Metzler, M.; Opal, S.; Lowry, S.; Balk, R.; Abraham, E.; Levy, H.; Slotman, G.; Coyne, E.; Souza, S.; et al. Recombinant platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase to prevent acute respiratory distress syndrome and mortality in severe sepsis: Phase IIb, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial*. Critical Care Medicine 2003, 31, 1612–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harishkumar, R.; Hans, S.; Stanton, J.E.; Grabrucker, A.M.; Lordan, R.; Zabetakis, I. Targeting the Platelet-Activating Factor Receptor (PAF-R): Antithrombotic and Anti-Atherosclerotic Nutrients. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Kwong, A.C.; Madarati, H.; Kunasekaran, S.; Sparring, T.; Fox-Robichaud, A.E.; Liaw, P.C.; Kretz, C.A. Characterization of ADAMTS13 and von Willebrand factor levels in septic and non-septic ICU patients. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0247017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peetermans, M.; Meyers, S.; Liesenborghs, L.; Vanhoorelbeke, K.; De Meyer, S.F.; Vandenbriele, C.; Lox, M.; Hoylaerts, M.F.; Martinod, K.; Jacquemin, M.; et al. Von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS13 impact on the outcome of Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2020, 18, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peetermans, M.; Meyers, S.; Liesenborghs, L.; Vanhoorelbeke, K.; De Meyer, S.F.; Vandenbriele, C.; Lox, M.; Hoylaerts, M.F.; Martinod, K.; Jacquemin, M.; et al. Von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS13 impact on the outcome of Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. J Thromb Haemost 2020, 18, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Stojanovic-Terpo, A.; Xu, W.; Corken, A.; Zakharov, A.; Qian, F.; Pavlovic, S.; Krbanjevic, A.; Lyubimov, A.V.; Wang, Z.J.; et al. Role for platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX and effects of its inhibition in endotoxemia-induced thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and mortality. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013, 33, 2529–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardon-Bounes, F.; Ruiz, S.; Gratacap, M.P.; Garcia, C.; Payrastre, B.; Minville, V. Platelets Are Critical Key Players in Sepsis. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkata, C.; Kashyap, R.; Farmer, J.C.; Afessa, B. Thrombocytopenia in adult patients with sepsis: incidence, risk factors, and its association with clinical outcome. J Intensive Care 2013, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.; Auerbach, H.E. New-onset acute thrombocytopenia in hospitalized patients: pathophysiology and diagnostic approach. Journal of Community Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives 2017, 7, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, H.G.; Peng, J.; Ni, H.; Hou, M.; Jansen, A.J.G. Low platelet count as risk factor for infections in patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia: a retrospective evaluation. Ann Hematol 2018, 97, 1701–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzey, B.D.; Tian, J.; Jensen, R.J.; Swanson, A.K.; Lees, J.R.; Lentz, S.R.; Stein, C.S.; Nieswandt, B.; Wang, Y.; Davidson, B.L.; et al. Platelet-Mediated Modulation of Adaptive Immunity: A Communication Link between Innate and Adaptive Immune Compartments. Immunity 2003, 19, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Zeng, H.; Chen, H.; Fan, L.; Xu, C.; Huang, H.; Tang, T.; Li, M. Current knowledge of thrombocytopenia in sepsis and COVID-19. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1213510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.; Liu, Y.; Barty, R.; Cook, R.; Rochwerg, B.; Iorio, A.; Warkentin, T.E.; Heddle, N.M.; Arnold, D.M. The association between platelet transfusions and mortality in patients with critical illness. Transfusion 2019, 59, 1962–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, S.R.; Garrigue, D.; Nougue, H.; Meyer, A.; Boutonnet, M.; Meaudre, E.; Culver, A.; Gaertner, E.; Audibert, G.; Vigué, B.; et al. Impact of platelet transfusion on outcomes in trauma patients. Critical Care 2022, 26, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Fan, C.; Ma, J.; Tang, C.; Chen, Y. Platelet Transfusion in Patients With Sepsis and Thrombocytopenia: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis Using a Large ICU Database. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).