1. Introduction

Tumor have always been a significant threat to human health. According to the study released by International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 2024, one-fifth of people will develop cancer in their lifetime, and the global death toll from cancer will reach 9.7 million in 2022 [

1]. Photodynamic therapy (PDT), as a non-invasive emerging antitumor therapy, is widely used in various types of tumors. The photosensitizers (PSs) can produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) when exposed to light of a specific wavelength [

2,

3]. This leads to an imbalance in the tumor cell redox microenvironment, with an excessive accumulation of ROS reaching a toxicity threshold, and ultimately triggering various programmed cell deaths [

4,

5,

6]. Due to the high precision of external light irradiation, although photosensitizers are typically administered systemically, only the irradiated area can exert biological activity. Therefore, PDT is considered to have more potential in tumor treatment compared to traditional radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

To fully harness the potential of PDT, three essential conditions must be met: the presence of light, photosensitizers, and oxygen, as delineated in the underlying mechanism of PDT [

3,

7,

8]. PDT comprises two sequential processes: Initially, PSs in their ground state accumulate in tumor tissue. Upon absorbing photons energy, these PSs transition to an excited singlet state. Through intersystem crossing (ISC), the unstable singlet-state PSs convert to a triplet state, where PSs generate various bio-toxic ROS through electron or energy transfer mechanisms [

9,

10]. There are two types of photosensitizers: Type II PSs rely on tissue oxygen and convert triplet oxygen into singlet oxygen (¹O₂) through energy transfer, while type I PSs are less reliant on oxygen and can generate diverse ROS through electron transfer. Regardless of the type of photosensitizer, illumination from a light source within the excitation band is necessary [

3,

8,

11]. The excitation light sources for commonly used photosensitizers, such as 5-ALA, Chlorin e6, phthalocyanines, etc. can be mainly classified into blue light and near-infrared (NIR) light. The near-infrared light, which offers the strongest tissue penetration, typically penetrates tissues by less than 1 mm, while the blue light has even weaker penetration [

12]. Extracorporeal light source has been a significant advantage of PDT, allowing for spatiotemporally controlled activation of PSs. However, with the development of PDT, in vitro light sources have become a limitation in clinical application due to their insufficient tissue penetration.

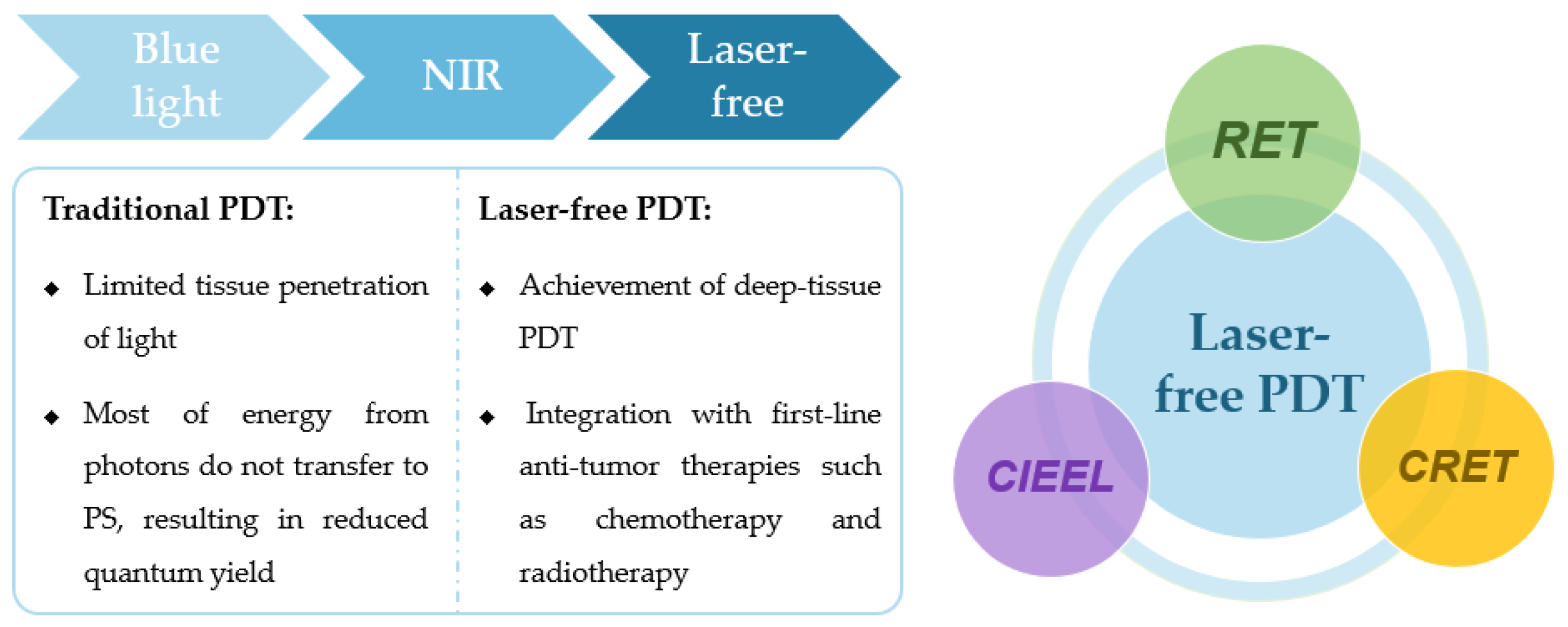

In recent years, there has been a surge of research focused on enhancing the photosensitive system, overcome the limitations of external light sources and enable in vivo self-luminescence for PDT. These laser-free PDT systems herald a renaissance for many previously overlooked blue light-dependent photosensitizers, offering the potential for effective deep tissue treatment and imaging. This article reviews the latest advancements in laser-free PDT systems, with a special emphasis on resonant energy transfer (RET), chemically induced electron exchange luminescence (CIEEL), and Cherenkov radiation energy transfer (CRET). It aims to provide a theoretical foundation for the development of novel laser-free PDT systems, thereby expanding the application scope of PDT and offering new insights into various combination therapies for tumors.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the PDT evolution, the main categories of laser-free PDT and their differences from traditional PDT.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the PDT evolution, the main categories of laser-free PDT and their differences from traditional PDT.

2. Laser-free PDT Based on Resonance Energy Transfer (RET)

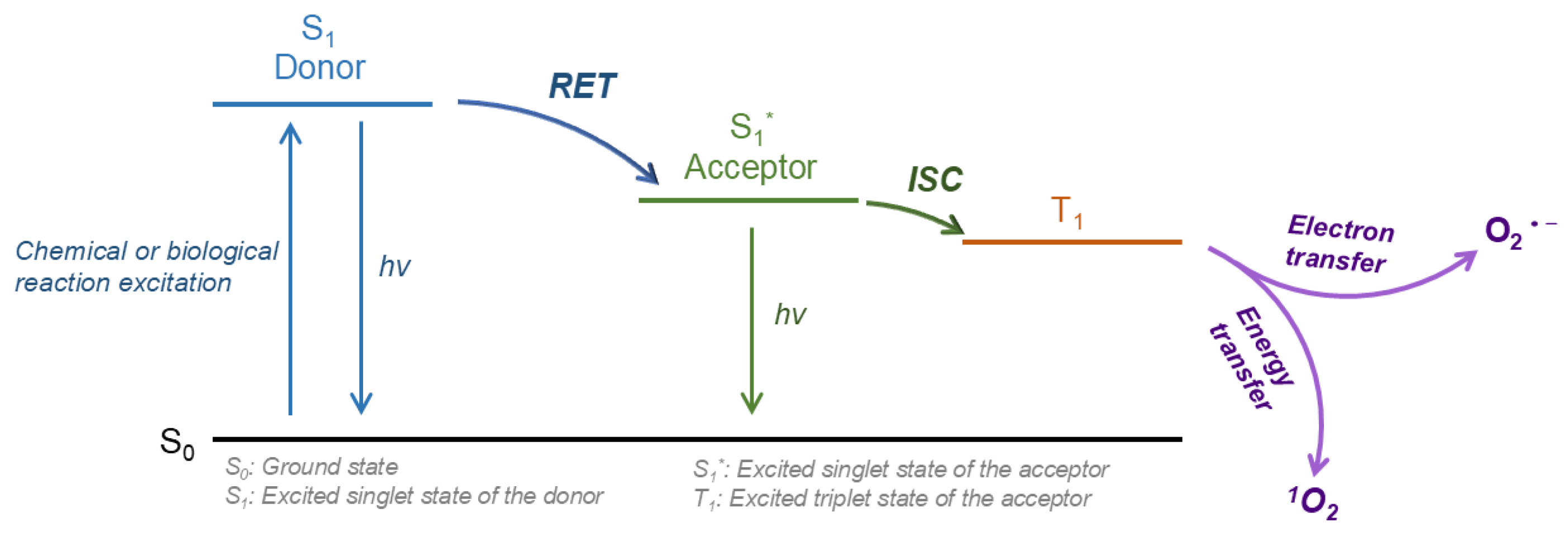

The most widely studied laser-free PDT system is based on Resonance Energy Transfer (RET). RET arises from the dipole-dipole interaction between two closely spaced fluorescent molecules: the donor molecule and the acceptor molecule. When the donor is excited, energy is transferred to receptors located within a critical radius, leading to a decrease in donor fluorescence and an increase in receptor fluorescence [

13,

14]. The stimulated receptors, i.e. the PSs that actually exert bioactivity, can generate different types of ROS through electron transfer (type I PS) or energy transfer (type II PS) (

Figure 2). The selection of donor and acceptor molecules must meet two conditions: (1) the emission spectrum of the donor overlaps with the excitation spectrum of the acceptor[

15]; (2) the distance between the donor and acceptor is less than the critical radius (1-10 nm)[

16]. And the alignment of the energy levels of the donor and acceptor is also a crucial factor which can greatly influence the efficiency of RET.

Currently, research on RET is primarily divided into three main categories: Chemiluminescent Resonance Energy Transfer (sometimes abbreviated as CRET, though in this review, CRET specifically refers to Cherenkov radiation energy transfer), Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET), and Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET). However, since FRET is limited by the need for excitation light to excite donor molecules, this review will focus on chemiluminescence and bioluminescence RET, rather than FRET. Given the highly similar mechanisms underlying both chemiluminescence and bioluminescence RET, which often lead to confusion between these two concepts in some research, this article primarily categorizes various RET systems based on the donor molecules involved, without making a detailed distinction between the two.

2.1. Luminol/H2O2 Donor Systems

So far, the most extensively studied donor luminescence is primarily blue light, with luminol being one of the most widely used substance. Luminol is a classic chemiluminescent reagent that, when oxidized by H

2O

2 in the presence of certain catalysts (such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP), Fe

2+, or Cu

2+), produces an excited-state aminophosphate that emits blue light (around 425 nm) for approximately 30 minutes [

17,

18]. Due to the overexpression of H

2O

2 in the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

19,

20,

21], luminol has always been considered an excellent RET donor molecule. In 2006, Huang et al. first proposed the concept of chemiluminescence RET and achieved energy transfer between luminol and quantum dots through the luminol/H

2O

2 chemiluminescence reaction catalyzed by HRP [

22]. However, H

2O

2 also reacts with PSs (acceptor), leading to irreversible photobleaching and a subsequent reduction in the chemiluminescence efficiency (CL). Moreover, the CL collection efficiency in this system is low, with a chemiluminescence RET ratio of only about 0.3. In 2012, Chen et al. first proposed the concept of

in situ PDT with Fe

2+, luminol, and 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) [

23]. Since 5-ALA facilitated the more rapid synthesis of PpIX (the actually effective PS) in normal cells compared to tumor cells, the excitation of luminol was timed to coincide with this synthetic window, thereby safeguarding normal cells. Despite the luminol's light dose being significantly lower than that of direct light irradiation, this combined approach still demonstrates a notable capacity to trigger cell necrosis and apoptosis in vitro, hinting at promising potential for the further advancement of the luminol donor.

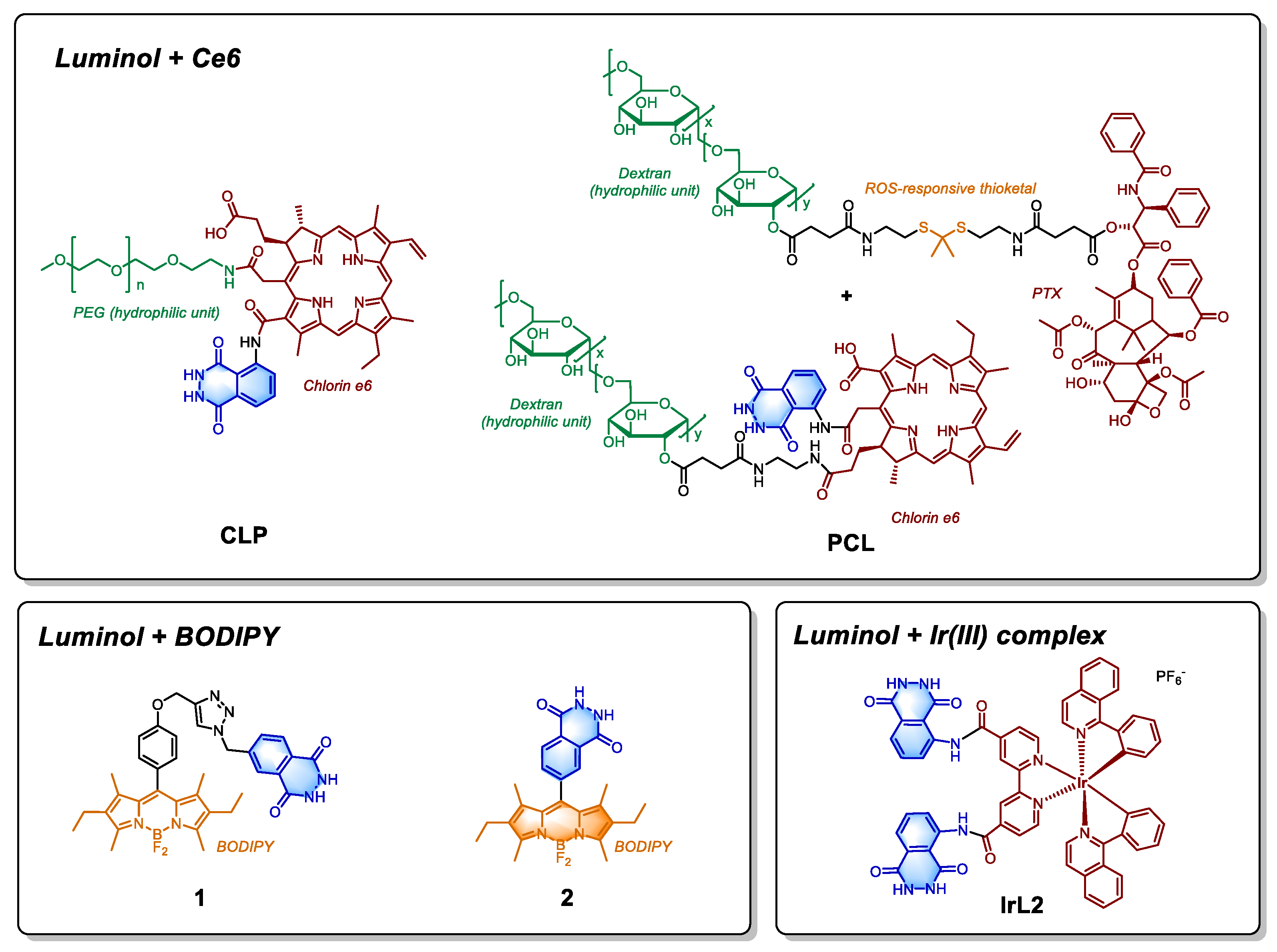

In recent years, the application of luminol reaction has expanded and the above-mentioned problems have significantly been addressed. For example, Xu et al. designed a nanoparticle called CLP, containing Chlorin e6 (Ce6), luminol and polyethylene glycol (PEG) units (

Figure 3) for inflammation imaging and tumor treatment [

24]. The CL reaction of nanoparticles is driven by the elevated hydrogen peroxide levels in the TME. Since luminol and Ce6 are covalently linked, the distance between them is optimized for efficient energy transfer. While the system yields promising results in imaging inflammatory tissues, its effectiveness in tumor treatment is less satisfactory. This limitation is not only due to CL efficiency issues and the absence of catalyst, but also largely stems from factors such as the structural design of nanoparticles, drug dosage, and the ability of Ce6 to generate singlet oxygen. To enhance the efficiency of CL, the types of catalyst that facilitate the oxidation of luminol are crucial. Weng et al. innovatively combined the hemin/G-quadruplex DNAzyme containing UiO-66 nanoplatform with chemiluminescence RET based photodynamic therapy (PDT), creating an integrated nanoplatform for both targeted therapy and imaging. In order to address the issue of insufficient treatment effectiveness, some researchers have also explored combination therapy. For example, Ding et al. synthesized multi-component PCL-NPs (

Figure 3) based on pectin, incorporating a ROS-activable thioketal-based paclitaxel (PTX) prodrug along with luminol/Ce6 [

25]. ROS generated from chemiluminescence RET mediated PDT primarily serves to release PTX and achieve the combination therapy of PDT and chemotherapy, directly mediating cell death.

In addition to Ce6, boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) is another widely used class of photosensitizers (PS). Degirmenci et al. developed two heavy-atom free luminol-BODIPY small molecule drugs (

Figure 3, Compound

1 and

2), which are designed to enhance the yield of triplet oxygen by enhancing the intersystem crossing (ISC) process [

26]. The distance between the luminol unit and BODIPY units in compounds

1 and

2 differs, the RET efficiencies could reach 0.53 and 0.99, respectively. Between these two, compound

2, activated exclusively by H

2O

2, demonstrates high selectivity. However, both compounds exhibited low activity in laser free in vitro experiments, likely due to the possible absence of catalyst, although they did show cytotoxicity upon red light excitation. In 2024, Wu et al. employed a similar approach to activate hybrid protein oxygen nanocarrier coated graphene quantum dots through chemiluminescence RET, using luminol as the donor. This strategy resulted in an in vitro activity of 16 μg/mL in L929 cell line [

27]. Since luminol was placed on a separate nanoparticle, its potential toxic effects may be mitigated through controlled, separate administration.

The aforementioned photosensitizers (PSs) are both type II PSs, with their ability to generate singlet oxygen largely dependent on the oxygen content in tumor tissue. In contrast, the Ir(III)-based nanoplatform IrL2H developed by Liu et al. is a type I PS, capable of generating various ROS such as superoxide radicals (O2

·-). IrL2H liposomes contains Ir(III) complexes covalently linked to two molecules of luminol (IrL2,

Figure 3), with hemoglobin (Hb) serving as a catalyst for the chemiluminescence reaction. IrL2H is effective in hypoxic tumor tissues, producing enhanced ROS and demonstrating strong activity in both in vivo and in vitro experiments.

The blue light emitted by luminol/H

2O

2 chemiluminescence (CL) reaction aligns with excitation wavelengths of various PS receptors, making it highly applicable in PDT. However, several challenges remain that limit the clinical applicability of luminol in certain contexts: (1) Luminol is highly susceptible to oxidation by hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) in alkaline environments (pH ≥ 9), but the tumor microenvironment (TME) typically has a much lower pH, which results in reduced chemiluminescence (CL) efficiency in the absence of effective catalysts. This discrepancy in pH can hinder the compound's performance under physiological conditions [

28,

29]; (2) There is evidence suggesting that luminol may have potential genotoxicity, raising concerns about its safety profile, especially with prolonged exposure or in high concentrations [

30]; and (3) Luminol has a high affinity for proteins, which could lead to non-specific binding and interfere with its intended actions, potentially affecting its overall therapeutic efficacy and bioavailability [

31]. These issues need to be addressed for luminol to be considered a viable option for clinical use. Currently, its use is largely limited to tumor imaging. To unlock luminol's full therapeutic potential, the development of advanced drug delivery systems and more efficient resonance energy transfer (RET) pathways may be necessary. The ultimate goal would be to achieve cytotoxicity primarily through photodynamic therapy (PDT), rather than relying solely on the drug molecules themselves.

2.2. Luciferase-Catalyzed Donor Systems

Alongside luminol, the luciferase-catalyzed luciferin system is another important example of resonance energy transfer (RET). Luciferase is a general term for enzymes that produce biological fluorescence. Currently, the research mainly focuses on firefly luciferase (FL), which can catalyze the oxidative decarboxylation of D-luciferin in the presence of Mg

2+, ATP, and oxygen, emitting yellowish-green visible light (550-580 nm). Since its first isolation in 1956, FL has received widespread attention across various fields. The reaction catalyzed by luciferases is considered a key representative of bioluminescence energy resonance transfer (BRET). FL catalyzed D-luciferin was used as the donor to activate various PSs, such as Rose Bengal [

32], hypericin [

33], m-THPC (Temoporfin) [

34], and quantum dots [

35].

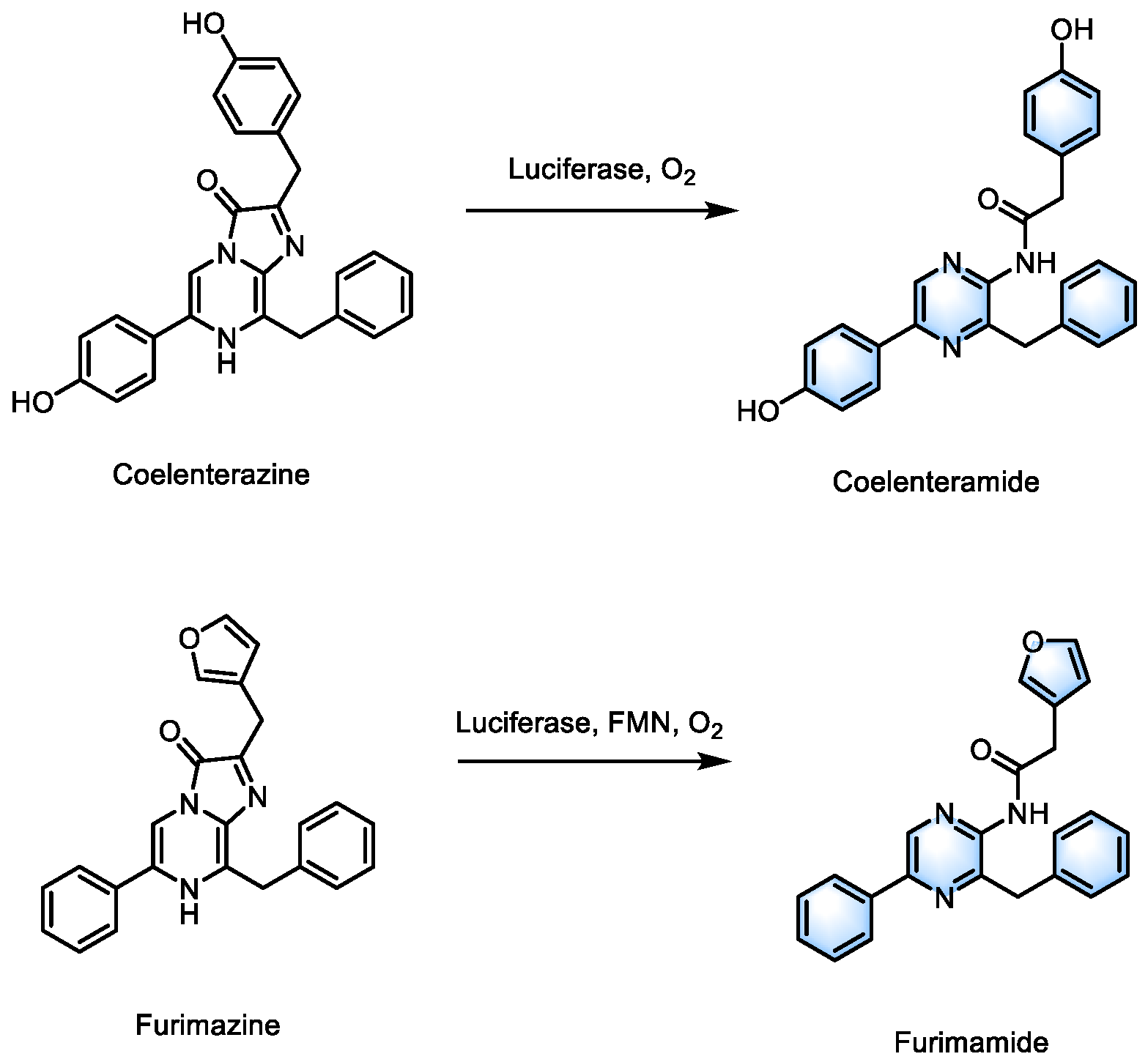

In addition to traditional FL/D-luciferin, various novel luciferase enzymes and substrates have also been developed. Coelenterazine (CTZ), a luciferin derived from marine organisms, can be oxidized and emit light at 400-480 nm in the presence of luciferase with only oxygen as a cofactor (

Scheme 1)[

36,

37]. The RLuc8-Ce6 conjugates, developed by Yan and colleagues, catalyze the substrate methoxy e-coelenterazine (a CTZ analogue) and stimulate Ce6 to achieve PDT through the

Renilla renormalizis Luciferase 8 (RLuc8) protein [

38]. As a natural low-toxicity compound, CTZ can be administered via direct intravenous injection in in vivo experiments. In vitro studies demonstrated that the conjugates exhibit a significantly lower IC

50 (approximately one-third) in 4T1 cells and MDA-MB-231 cells compared to laser-induced PDT. Additionally, the activation rate of this conjugate, defined as the ratio of photons transferred to activate Ce6 to the total photons generated by bioluminescence, can reach up to 80%. This conjugate has also shown a strong ability to produce ROS in vivo and in vitro experiments, leading to complete tumor regression in the early three negative breast cancer (TNBC) tumor modeling.

Although small molecule fluorescent substrates are generally regarded as having low toxicity, they may still pose other risks in therapeutic applications. In contrast, more stable and less toxic photosensitive proteins offer the potential for expanding the application of BRET-PDT. In 2022, Shramova's team proposed a gen-encoded PDT platform that utilizes genetically engineered NanoLuc luciferase to catalyze furimazine as the donor and phototoxic flavoprotein miniSOG as the PS, while generating multiple ROS through type I and II photoreactions [

39]. However, NanoLuc catalysis requires Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN) as a cofactor, so additional riboflavin mononucleotide needs to be supplied to enhance the endogenous concentration of FMN. In 2023, the same BL reaction and the SOPP3 protein were employed by Shramova's team to achieve higher

1O

2 yield and higher photoinduced phototoxicity [

40]. However, in the absence of external laser irradiation, the PDT system lacked the targeting capability typically associated with light-activated therapies. In 2024, this limitation was addressed by incorporating a targeting protein module, DARPin into the NanoLuc-SOPP3 BRET platform. Such modification enabled successful targeting of HER2 positive cells in both in vitro 3D spheroid models and in vivo experiments [

41].

Scheme 1.

Structures of luciferase substrates and their catalytic products.

Scheme 1.

Structures of luciferase substrates and their catalytic products.

The emission light of the donor and the excitation light of the acceptor should ideally overlap as much as possible, but not all donor/acceptor pairs can perfectly meet this spectral overlap requirement. Therefore, a two-stage relay energy transfer process, “donor-intermediate-acceptor” may be more suitable for achieving efficient RET. Foscan

® (m-THPC) is a commercially available photosensitizer with an excitation wavelength of 652 nm. The emission wavelength of coelenterazine catalyzed by luciferase (RLuc8) ranges between 390-600 nm, which does not effectively overlap with the excitation wavelength, thus hindering efficient RET. Therefore, Hsu et al. incorporated quantum dots (QDs-655,

λabs=600-710 nm) into their BRET based nanoplatform, enabling effective activation by BRET and meeting the requirements of Foscan

® [

42]. Through the energy transfer of quantum dots, the BRET ratio can reach 0.92, and in vivo experiments have shown significant inhibition of tumor tissue growth.

The luciferase-based BRET system requires the co-existence of substrates, luciferase, and its cofactor to effectively transfer energy to the PS acceptor, a complex process that may introduce unintended errors in tissues. Additionally, the toxicity associated with systemic administration of these substrates and cofactors presents a significant challenge to its practical application. Furthermore, the immunogenicity of luciferase, an exogenous protein, upon release in vivo remains unclear. Therefore, future research may focus on developing fluorescent enzymes that function independently of cofactors and novel fluorescent substrates with reduced toxicity.

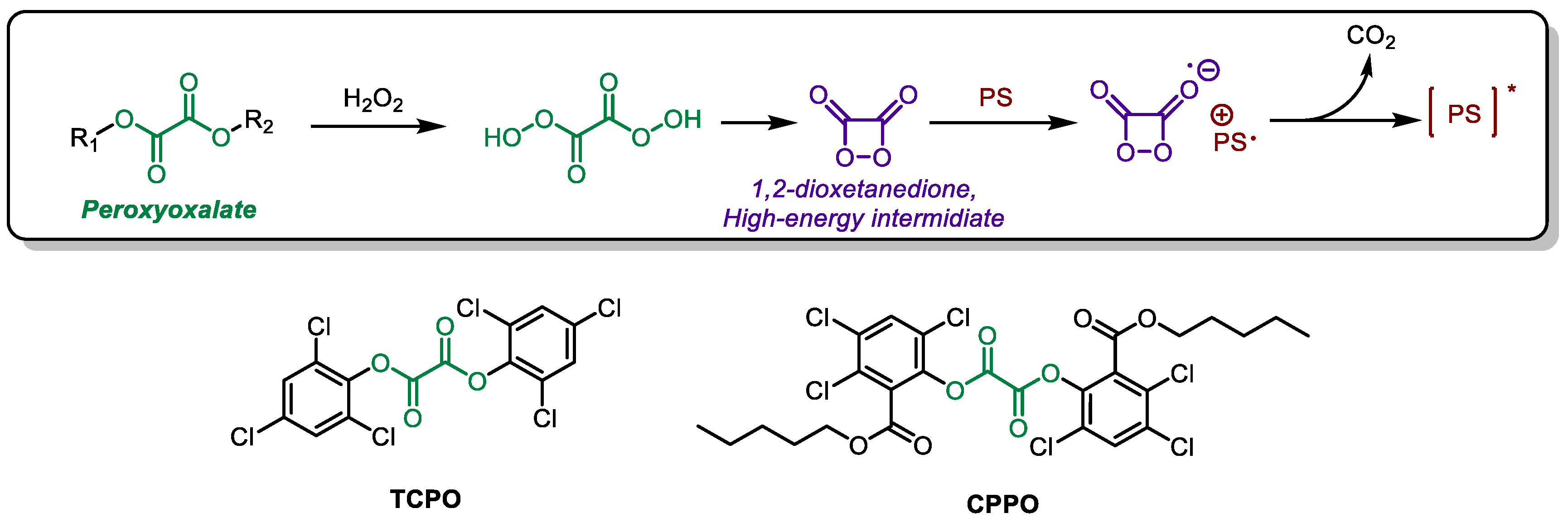

3. Chemically Initiated Electron Exchange Luminescence (CIEEL)

Another form of chemiluminescence (CL) besides RET is chemically initiated electron exchange luminescence (CIEEL). At present, the application of CIEEL is mainly focused on Peroxyoxalate (PO) systems. Luminol exhibits unstable CL efficiency and potential toxicity, while the luciferase system appears too complex for biological tissues. In contrast, Peroxyoxalate Chemiluminescence (POCL) is a promising alternative to luminol and luciferase. PO does not require additional catalysts and can react in an H

2O

2 environment to produce 1,2-dioxetanedione, a high-energy intermediate (HEI). This HEI can further interact with an activator, such as a PS in PDT systems, to excite the PS through CIEEL (

Scheme 2)[

43,

44]. Unlike the Förster energy transfer process, the Dexter mechanism governs the energy transfer in CIEEL. CIEEL does not require spectral overlap between the donor and acceptor; instead, it primarily depends on the proximity of the HEI and activator molecules [

45]. CIEEL possesses the capability to emit light of multiple colors from a single donor, rendering it a more versatile and widely used technique in imaging applications.

TCPO, a classic molecule in peroxyoxalate systems (

Scheme 1), was employed by Liang et al. to activate Ce6. As a type II photosensitizer (PS), Ce6 generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) in an oxygen-dependent manner. To address this, perfluorohexane (PFC) was incorporated into the nanoparticles to serve as an oxygen carrier. [

46] Given the close relationship between POCL efficiency and H

2O

2 levels in tumor tissue, increasing endogenous H

2O

2 levels clearly has the potential to enhance POCL efficiency. Yu et al. employed glucose oxidase (GOx) to catalyze the conversion of glucose to H

2O

2 and induce glucose starvation in the CPPO-Ce6 nanosystem, a strategy similar to that of Liang et al. [

47]. In in vivo experiments, this strategy showed good efficacy against both primary and metastasis tumors. Similarly, Mao et al. developed a treatment imaging integrated nanoprobe using a comparable approach [

48]. They chose TBD, a PS with far red/near infrared (FR/NIR) emission and high singlet oxygen yield, as the receptor for the nanoprobes. Notably, the alignment of HOMO of TBD with the LUMO energy levels of 1,2-dioxetanedione intermediate significantly enhances energy transfer, thus improving the efficiency of PS excitation [

49]. likewise, Liu et al. incorporated cinnamaldehyde (CA) to upregulate intramolecular NADPH levels, which indirectly elevates the concentration of H

2O

2 [

50].

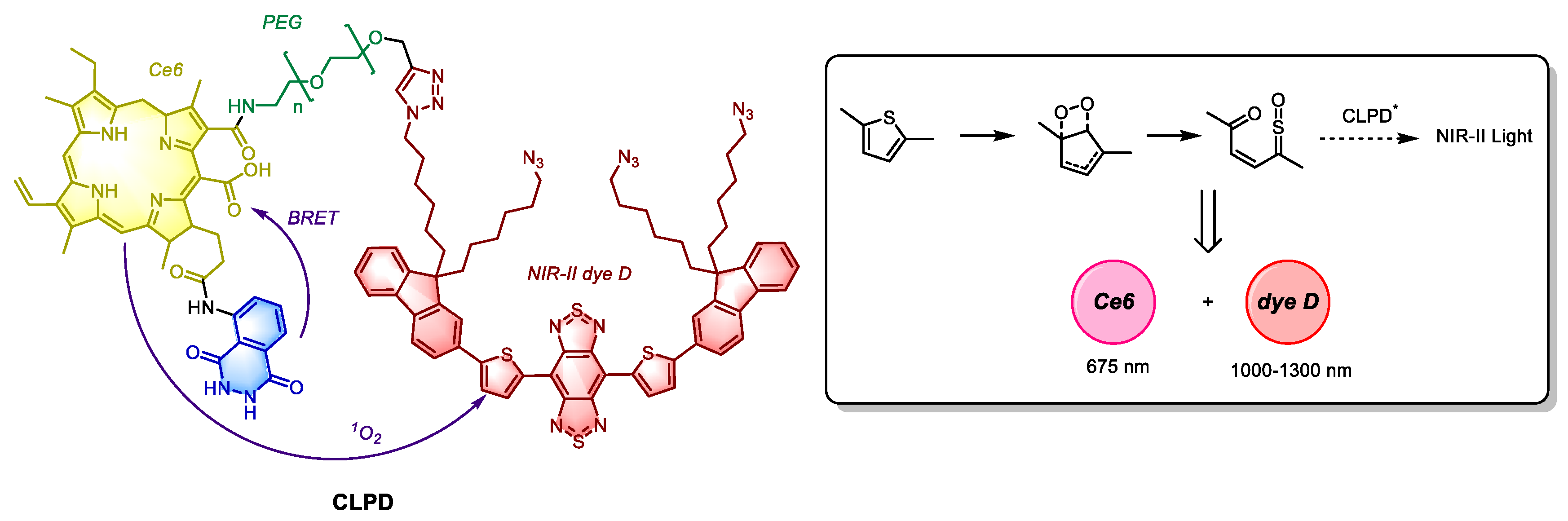

In Yuan’s strategy, a more advanced approach was adopted through a luminol-Ce6-NIR-II dye D nanosystem called CLPD (

Figure 4). In this system, luminol is oxidated by H

2O

2 and excess myeloperoxidase (MPO) present in tumor tissue, which subsequently activates Ce6 via Förster resonance energy transfer (RET). The

1O

2 generated by activated Ce6 then oxidizes the S-C bond of thiophene in dye D through π

2-π

2 cycloaddition, forming a thiophene-dioxetane intermediate. Although the absorption band of dye D overlaps with the emission band of Ce6, its excitation is not driven by RET, but rather by CIEEL following

1O

2 oxidation. In both in vitro and in vivo experiments, the CLPD system demonstrated significant PDT therapeutic effect, and enabled deep tissue imaging of inflammatory regions [

51]. The CIEEL process observed in CLPD, which is independent of peroxyoxalate compounds, holds substantial promise for the development of novel laser free, CIEEL-mediated photosensitive systems.

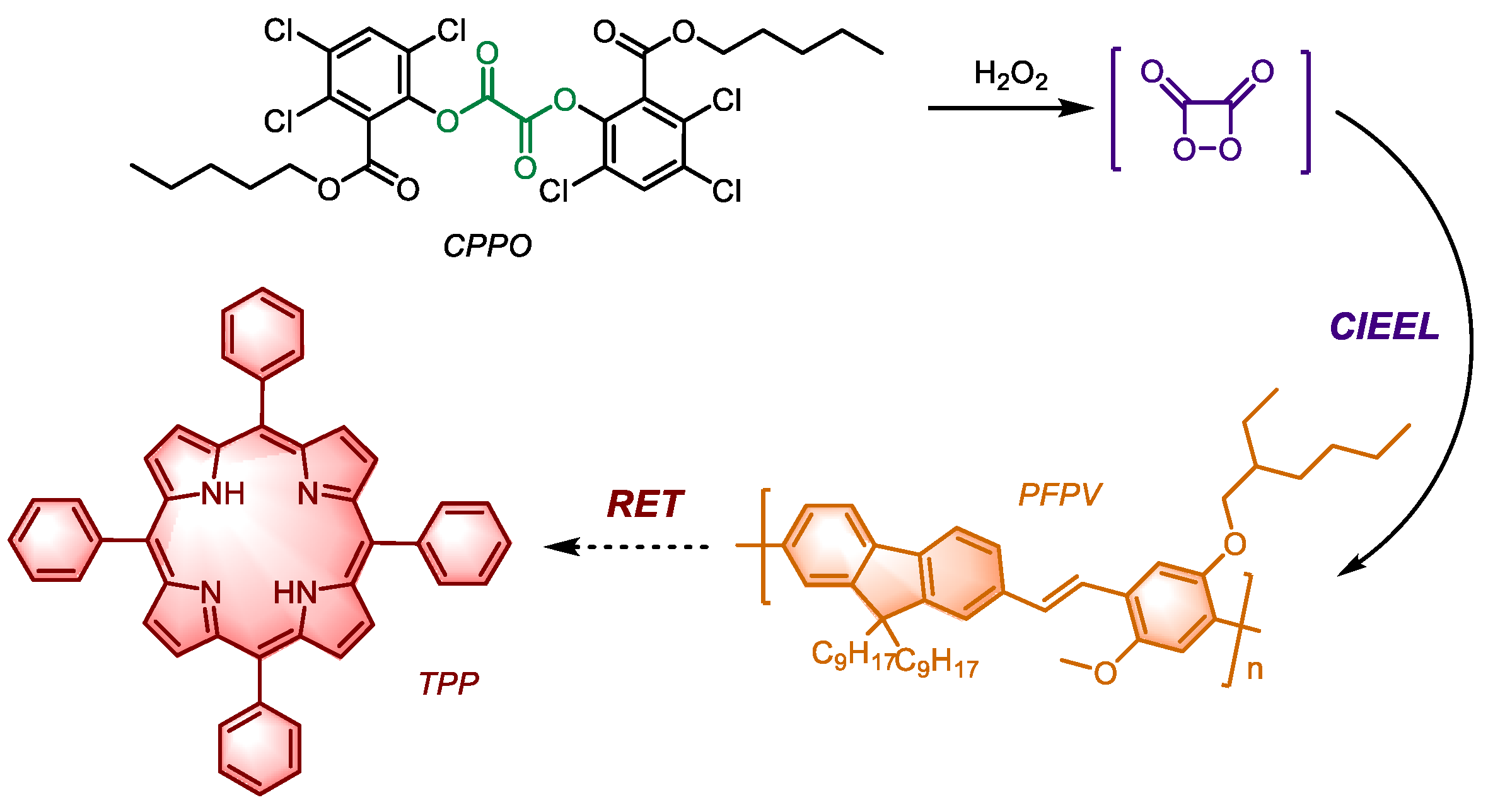

The combination of CIEEL and RET-mediated luminescence represents another promising approach. The nanoparticle POCL (

Figure 5) developed by Wu et al. incorporates CPPO and the first-generation photosensitizer TPP, alongside PFPV as a chemiluminescence donor to enhance energy transfer efficiency. Notably, the emission wavelength of PFBT can overlap with the Q-band (Weak absorption band generated by n - π transition of porphyrin compounds) of TPP, however, due to the large difference in energy levels between its HOMO and LUMO of HEI in CIEEL, it is not an effective intermediate for energy transfer. On the other hand, PFPV satisfies the energy transfer requirements of the previous stage, also can align with the Q-band absorbance wavelength of TPP, thereby significantly improving the quantum yield.

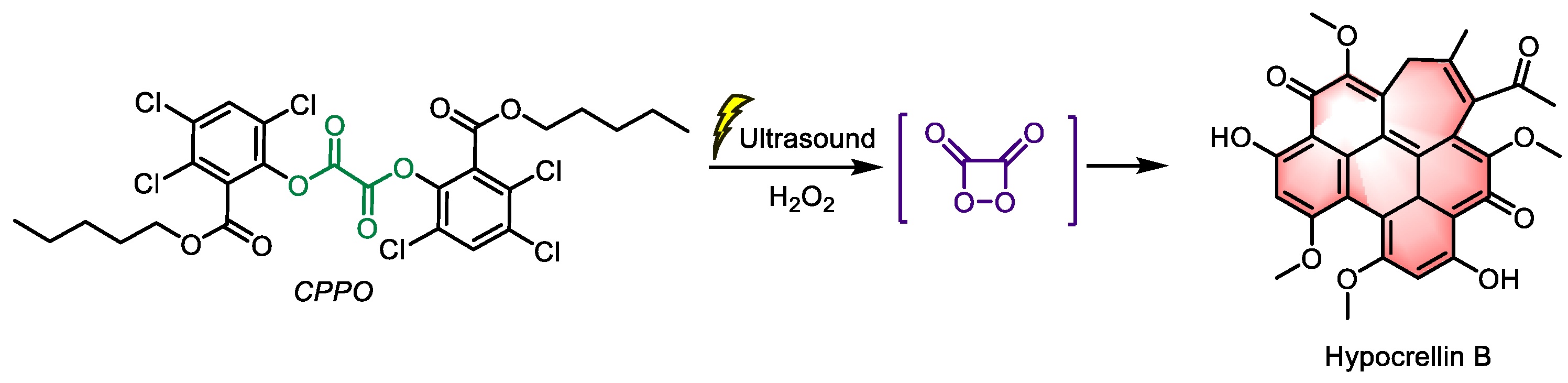

Additionally, ultrasound enhanced chemiluminescence (UECL) is gaining increasing attention as ultrasound can enhance the intensity of CL [

52]. Ding et al. developed a UECL PDT system, using CPPO as the donor and hypocrellin B (

Figure 6, a type II PS from Chinese natural herbs with high

1O

2 yield) as the acceptor [

53]. This nanoparticle was introduced into A549 cells cultured in vitro. Without ultrasound, there was minimal ROS production, however, after ultrasound treatment (1 W/cm

−2, 1 MHz, 50% cycle, 30 s), significant death was observed. With the development of sonodynamic therapy, an increasing number of PSs are being recognized for their sono-sensitive characteristics. This nano-system, with its UECL-RET mechanism, can potentially exert a synergistic effect in photo-sonosensitizers, creating an integrated ultrasound-mediated platform for photo-sonodynamic therapy.

The primary constraint of the PO systems, as revealed by their applications, lies in the concentrations of H2O2 and oxygen. Nevertheless, this challenge can be addressed through established strategies, such as oxygen self-supply mechanisms and methods to enhance H2O2 levels. Additionally, UECL shows significant potential when combined with sonodynamic therapy, and further broadening the scope of the chemiluminescence applications.

4. Cherenkov Radiation Energy Transfer (CRET) Induced PDT

When a charged particle (usually an electron) moves through medium at a speed exceeding the speed of light, it disturbs the electromagnetic field in the medium. This disturbance generates a shockwave-like electromagnetic field structure that trails behind the particles. This shockwave propagates at the speed of light in the medium and emits electromagnetic radiation, a phenomenon known as Cherenkov radiation [

54,

55,

56]. Cherenkov radiation is produced by the decay of radionuclides, such as

82Gb,

89Zr, and

198Au, which emit β

+ particles, and

90Y,

131I, ad

177Lu, which emit β

- particles. And these high-speed particles induce local polarization along their direction of motion, generating detectable optical signals known as Cherenkov luminescence, as the medium returns to equilibrium,. The spectrum of Cherenkov luminescence is continuous (200-1000 nm), with the highest intensities in the high-frequency ultraviolet (UV) and blue light range (200-400 nm). This light is sufficiently intense to excite photosensitizers (PSs) [

57,

58,

59].

Positron emission tomography (PET), a widely used imaging modality for tumor detection, identifies tumors within the body by detecting contrast agents containing radionuclides (such as

18F,

64Cu,

68Ga, etc.) that emit positrons (β

+)[

60]. Dutring β

+ decay, if the initial velocity of high-energy β

+ particles exceed the speed of light in tissue, Cherenkov radiation is produced.

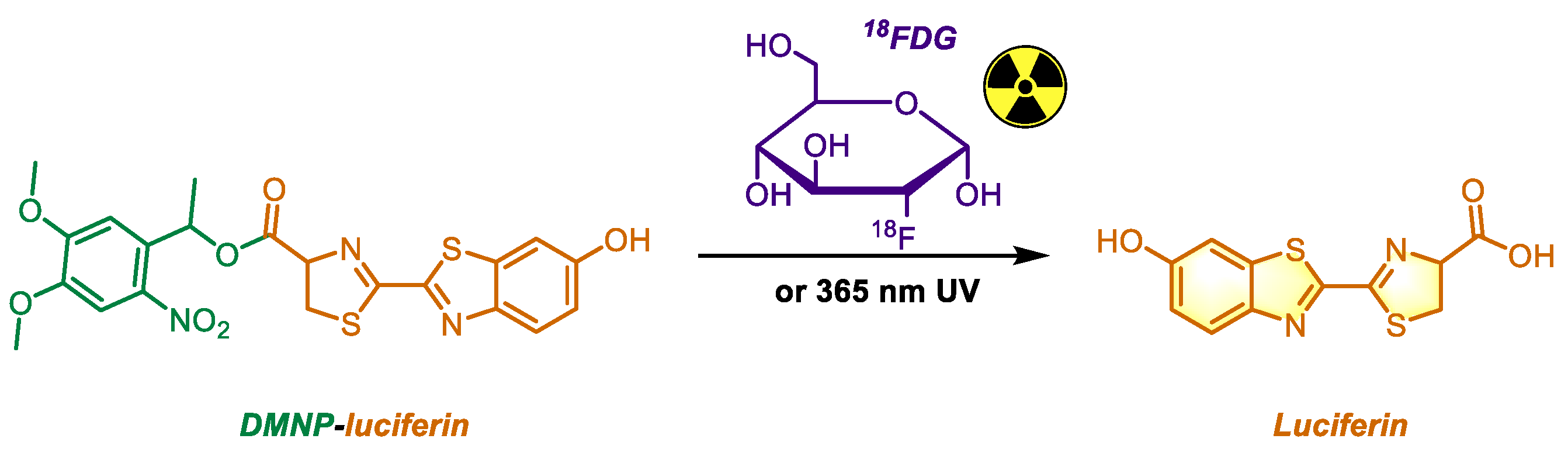

18F, with a half-life of 109.8 min, is an ideal radioisotope for PET, and 2-deoxy-2-[

18F] fluoro-D-glucose (

18FDG) is the most commonly used PET tracer in clinical practice [

61,

62]. In 2012, Ran et al. used

18FDG, a PET radiotracer, and combined with photocaged luciferin to verify its ability to generate Cherenkov radiation and release free luciferin (

Figure 7). In their in vivo experiment, the fluorescence signal intensity of luciferin 1-(4,5-dimethoxy-2-nitrophenyl) ethyl ester (DMNP-luciferin) combined with

18FDG was 12.5 times higher than that of

18FDG alone, peaking at 70 minutes after administration. DMNP, a well-known photocage unlocked by UV light at 365 nm, demonstrated high stability [

63], providing strong evidence for

18FDG to produce Cherenkov radiation in vivo. Eleven years later, Guo et al. applied

18FDG o CRET-induced photodynamic therapy (PDT). They utilized goat milk-derived extracellular vesicles loaded with

18FDG and Ce6 to achieve CRET-induced PDT [

64]. This photosensitizing system, incorporating

18FDG, shows potential for therapeutic applications while simultaneously enabling PET imaging, paving the way for the integration of therapy and imaging.

The intensity of Cherenkov luminescence mainly depends on the selection of radionuclides [

55]. Among them,

82Rb is considered the optimal, producing approximately 80 photons per decay. Other radionuclides, such as

68Ga,

62Cu,

90Y, can also generate over 30 photons per decay, significantly surpassing the 1.3 photons per decay produced by

18F [

62]. This disparity may explain why, despite the widespread clinical use of

18FDG, its combination with PDT is not particularly effective. In a study by Lioret et al., eosin (a type II PS, λ

abs at 524 nm, λ

em at 544 nm, and a fluorescence quantum yield of 0.67) was incorporated into the system to achieve PDT induced by Cherenkov luminescence from

68Ga,

90Y and

18F. They employed two approaches: directly mixing

18F-FDG or

90Y-YCl

3 with eosin to achieve intermolecular-CRET, and covalently binding

68Ga with eosin (

Figure 8) to facilitate both intra- and intermolecular CRET. The 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF), a widely used

1O

2 probe, was used to verify the PDT effect of these systems. Notably, eosin with and without

68Ga are essentially two distinct compounds, and their biological activities cannot be directly compared. However,

68Ga was found to significantly enhance the PDT effect. In cell experiments, when eosin was used at low doses where its inherent toxicity was negligible, its combination with radionuclides exhibited significant cytotoxicity, which can be attributed to PDT. As the exposure time increases, the cytotoxicity also escalated, likely due to the synergistic effects of radiotherapy, PDT, and the compound itself.

In 2023, Zhang et al. developed a hydrogel containing R837 (the immune adjuvant imiquimod) and

89Zr-HG-PpIX to achieve CRET-induced PDT [

65]. This hydrogel exhibits minimal phototoxicity in normal tissues, and low radiation leakage, with its safety validated in both in vivo and in vitro tests. Additionally, the overexpression of tumor-associated antigens induced by PDT, in combination with the adjuvant R837, significantly enhances the immune response in vivo. This advancement lays a strong foundation for integrating CRET-induced PDT and immunotherapy.

CRET-induced PDT shares similarities with the combination therapy that integrates radiotherapy and PDT. In fact, several treatment approaches combining X-ray with PDT have also been developed based on radiotherapy [

66,

67]. However, this article focuses exclusively on the laser-free PDT systems, which are designed as self-exciting systems independent of external triggers. Since X-ray activated PDT has not fully addressed this limitation, it will not be discussed in detail here.

5. Persistent Luminescence (PL) Systems

In recent years, persistent luminescence (PL, also known as afterglow luminescence) has emerged as a prominent research focus. Despite the fact that the PL systems requires pre-charging via UV irradiation in vitro and have not yet fully overcome the constraints posed by lasers, their 'endurance' is remarkably prolonged, lasting for several hours or even days, making them well suited for PDT applications [

68]. While this review primarily focuses on laser-free PDT systems, it is evident that PL systems are steadily gaining significance in PDT research. The mechanism of PL luminescence is relatively intricate but can be summarized as the capture and storage of energy in traps through charge carriers (electrons and/or holes), followed by its gradual release facilitated by thermal energy. Based on this principle, Zhao et al. developed a DNA nanocomplex integrating persistent-luminescence nanoparticles (PLNP) [

69]. The surface of PLNP is coated with a layer of MnO

2, which helps reduce energy dissipation before reaching the tumor and responds to high expression of GSH in tumor tissue by generating oxygen to alleviate hypoxia in the tumor. Additionally, an AS1411 aptamer-conjugated ultra-long single stranded DNA chain is incorporated to target nucleolin, overexpressed on tumor cells. This DNA chain also serves as a scaffold for the photosensitizer silicon phthalocyanine dichloride. In in vivo experiments, this strategy demonstrated an inhibition rate of over 50%, proving its effectiveness. However, the aptamer itself exhibited notable cytotoxicity suggesting that further advancements are needed to develop novel, safe PL systems with higher energy storage capacity and quantum yield. In the same year, Zhao published another study, incorporating 1-methyltrypsin alongside the aforementioned components. This modification enhanced T cell proliferation within tumor tissue, ultimately leading to the remodeling of the hypoxic and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) [

70].

Persistent luminescence (PL) systems face a significant challenge: energy dissipation in PLNPs after excitation. Even though certain PLNPs can sustain luminescence for several days, their energy gradually diminishes over time. Consequently, when PLNPs are introduced into the body, they exhibit their peak energy, maximum PDT activity, and the initial highest cytotoxicity. After several cycles and upon reaching the tumor tissue, their activity is significantly reduced. This intrinsic characteristic of PLNP cannot be addressed merely by structural modifications, which presents a considerable challenge in the development of the novel PL systems.

6. Limitations and Prospects

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a promising tumor treatment approach, but its effectiveness is often limited by the insufficient penetration of light through tissues. Recent advancements of photosensitizers (PSs) have gradually shifted from those activated by blue light to those activated by near-infrared light or even ultrasound. The advent of laser-free PDT systems has expanded the potential of PDT. Unlike traditional PDT, which relies on external light source for photon activation, laser-free systems leverage energy transfer mechanisms such as RET (Resonance Energy Transfer) or CRET (Cherenkov Radiation Energy Transfer), these mechanisms offer higher energy utilization efficiency and quantum yields. Additionally, laser free systems typically generate rapidly decaying blue light from energy donors within the tissue, minimizing risk to surrounding normal tissues. This innovation has revived interest in PSs previously considered unsuitable due to their reliance on blue light activation, unlocking their potential for tumor therapy. Moreover, laser-free PDT systems can be seamlessly integrated with other anti-tumor therapies and are often compatible with treatment imaging modalities, making them highly valuable for enhancing the precision of personalized treatments.

Research on laser-free PDT systems is still in its early stages and several challenges remain, preventing these systems from advancing to clinical trials. One of the most significant issues is their limited therapeutic efficacy. This limitation arises from the inherent constraints of the laser-free systems but also reflects a broader challenge in PDT, especially in the absence of external laser irradiation. While these systems, with their relatively weaker therapeutic capabilities, hold promise for integration with other cancer therapies, it is crucial to optimize the photosensitizing efficiency of PSs to maximize ROS generation. Achieving this optimization is essential to enhance the overall effectiveness of laser-free PDT and advance its potential as a viable treatment option.

In the RET process, the distance between the donor and acceptor must be smaller than the critical radius for effective energy transfer. If the molecules are not covalently linked, ensuring effective energy transfer could be challenging, and simply encapsulating them within nanoparticles may not adequately address this issue. Additionally, proper alignment of the HOMO energy level of the donor and the LUMO energy level of the acceptor in RET is also crucial, as improper alignment can significantly impede the energy transfer. In CRET systems, selecting an appropriate radionuclide is equally essential, requiring a careful balance of factors such as half-life, photon yield, and cytotoxicity to optimize performance and safety.

Furthermore, safety concerns also pose a significant challenge. Achieving self-excitation in many systems mentioned above require administration of more than three components. This added complexity raises questions about the practicality of implementing such treatments. While some individual components may exhibit minimal cytotoxicity, their combined use in a more complex system could pose unforeseen risks to normal tissues. Additionally, some studies have failed to conclusively demonstrate that the observed anti-tumor effects are exclusively attributable to PDT, as opposed to the inherent toxicity of the compounds used. These studies often only report increased ROS levels, which makes certain laser-free systems diverge from traditional PDT, at times resembling chemotherapy or radiotherapy under the guise of PDT.

7. Conclusions

Due to the insufficient tissue penetration of light, photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been largely restricted to the treatment of superficial tumors, significantly hindering its clinical applications. The emergence of laser-free PDT systems may mark a potential turning point in the evolution of PDT. This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest advancements in laser-free PDT systems, highlighting key energy transfer principles in their design, including resonance energy transfer (RET), chemically induced electron exchange luminescence (CIEEL), and Cherenkov radiation energy transfer (CRET). Although still in its nascent stages, this field holds immense potential to expand the scope of PDT applications. This review aims to provide a theoretical framework to guide the development of novel laser-free PDT systems and to propose directions for future research in PDT and its integration with combination therapy for tumor treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yi Li and Ruixue Jia; investigation and resources, Ruixue Jia; Shunyun Zhang and Jicheng Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, Ruixue Jia; writing—review and editing, Yi Li.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the Postgraduate Research Scholarships (PGRS) at XJTLU for providing the PhD scholarship (FOSA2312035) to R.J.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations |

Full name |

| PDT |

Photodynamic therapy |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

|

1O2

|

Singlet oxygen |

| PS |

Photosensitizer |

| NP |

Nanoparticle |

| RET |

Resonance energy transfer |

| CL |

Chemiluminescence |

| BL |

Bioluminescence |

| CRET |

Cherenkov radiation energy transfer |

| CIEEL |

Chemically initiated electron exchange luminescence |

| TME |

Tumor microenvironment |

| Ce6 |

Chlorin e6 |

| PO |

Peroxyoxalate |

| HOMO |

Highest occupied molecular orbital |

| LUMO |

Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital |

| NIR |

Near infrared light |

| UV |

Ultraviolet |

| UCEL |

Ultrasound-enhanced chemiluminescence |

| HEI |

High-energy intermediate |

| CTZ |

Coelenterazine |

| PL |

persistent luminescence |

References

- Global cancer burden growing, amidst mounting need for services. Saudi Med J 2024, 45, 326–327.

- Dolmans, D. E.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R. K. , Photodynamic therapy for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2003, 3, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostinis, P.; Berg, K.; Cengel, K. A.; Foster, T. H.; Girotti, A. W.; Gollnick, S. O.; Hahn, S. M.; Hamblin, M. R.; Juzeniene, A.; Kessel, D.; Korbelik, M.; Moan, J.; Mroz, P.; Nowis, D.; Piette, J.; Wilson, B. C.; Golab, J. , Photodynamic therapy of cancer: an update. CA Cancer J Clin 2011, 61, 250–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, L.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Y. , Photodynamic Therapy Combined with Ferroptosis Is a Synergistic Antitumor Therapy Strategy. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessel, D. , Apoptosis, Paraptosis and Autophagy: Death and Survival Pathways Associated with Photodynamic Therapy. Photochem Photobiol 2019, 95, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. N. , Mechanisms of tumor necrosis induced by photodynamic therapy. J Photochem Photobiol B 1989, 3, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, S.; Knap, B.; Przystupski, D.; Saczko, J.; Kędzierska, E.; Knap-Czop, K.; Kotlińska, J.; Michel, O.; Kotowski, K.; Kulbacka, J. , Photodynamic therapy - mechanisms, photosensitizers and combinations. Biomed Pharmacother 2018, 106, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, T. J.; Gomer, C. J.; Henderson, B. W.; Jori, G.; Kessel, D.; Korbelik, M.; Moan, J.; Peng, Q. , Photodynamic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998, 90, 889–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilgers, F.; Bitzenhofer, N. L.; Ackermann, Y.; Burmeister, A.; Grünberger, A.; Jaeger, K. E.; Drepper, T. , Genetically Encoded Photosensitizers as Light-Triggered Antimicrobial Agents. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Xu, D.; Wen, X.; Chen, C.; Liu, G.; Lu, Z. , Internal Light Sources-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy Nanoplatforms: Hope for the Resolution of the Traditional Penetration Problem. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2024, 13, 2301326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichiara, M.; Prezzavento, O.; Marrazzo, A.; Pittalà, V.; Salerno, L.; Rescifina, A.; Amata, E. , Recent advances in drug discovery of phototherapeutic non-porphyrinic anticancer agents. Eur J Med Chem 2017, 142, 459–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Shen, S.; Sun, P.; Gu, Z.; Bai, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. , Bioorthogonal chemistry for prodrug activation in vivo. Chem Soc Rev 2023, 52, 7737–7772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, N. T.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, J.; Lin, J.; Huang, P. , Recent Advances in Self-Exciting Photodynamic Therapy. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jares-Erijman, E. A.; Jovin, T. M. , FRET imaging. Nat Biotechnol 2003, 21, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugland, R. P.; Yguerabide, J.; Stryer, L. , Dependence of the kinetics of singlet-singlet energy transfer on spectral overlap. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1969, 63, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A. K.; Noumani, A.; Yadav, A. K.; Solanki, P. R. , FRET Based Biosensor: Principle Applications Recent Advances and Challenges. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X. L.; Zhang, N. N.; Shu, G. F.; Liu, D.; Qi, J.; Jin, F. Y.; Ji, J. S.; Du, Y. Z. , A Luminol-Based Self-Illuminating Nanocage as a Reactive Oxygen Species Amplifier to Enhance Deep Tumor Penetration and Synergistic Therapy. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 19394–19408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, T. B.; Basel, M. T. , Using Naturally Occurring Bioluminescent Enzymes to Track Specific Cell Populations. Methods Mol Biol 2020, 2126, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N.; Xiao, W.; Song, X.; Wang, W.; Dong, X. , Recent Advances in Tumor Microenvironment Hydrogen Peroxide-Responsive Materials for Cancer Photodynamic Therapy. Nanomicro Lett 2020, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, F.; Li, X.; Niu, G.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Jiang, Y. , Tumor microenvironment-responsive fenton nanocatalysts for intensified anticancer treatment. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; You, D. G.; Um, W.; Lee, J.; Kim, C. H.; Shin, S.; Kwon, S.; Park, J. H. , Chemiluminescence resonance energy transfer-based nanoparticles for quantum yield-enhanced cancer phototheranostics. Sci Adv 2020, 6, eaaz8400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Li, L.; Qian, H.; Dong, C.; Ren, J. , A resonance energy transfer between chemiluminescent donors and luminescent quantum-dots as acceptors (CRET). Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2006, 45, 5140–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.-C.; Huang, L.; Liu, C.-C.; Chao, P.-J.; Lin, F.-H. , Luminol as the light source for in situ photodynamic therapy. Process Biochemistry 2012, 47, 1903–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; An, H.; Zhang, D.; Tao, H.; Dou, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, J. , A self-illuminating nanoparticle for inflammation imaging and cancer therapy. Sci Adv 2019, 5, eaat2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Shi, Z.; Ou, M.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Wang, W.; Huang, Q.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Zeng, X.; Chen, H.; Mei, L. , Dextran-based micelles for combinational chemo-photodynamic therapy of tumors via in vivo chemiluminescence. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 319, 121192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, A.; Sonkaya, Ö.; Soylukan, C.; Karaduman, T.; Algi, F. , BODIPY and 2,3-Dihydrophthalazine-1,4-Dione Conjugates As Heavy Atom-Free Chemiluminogenic Photosensitizers. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2021, 4, 5090–5098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, P.; Yang, D. , A laser free self-luminous nanosystem for photodynamic therapy of cervical cancer cells. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2023, 44, 103756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Liu, Y.-T. , Mechanistic Insight into pH-Dependent Luminol Chemiluminescence in Aqueous Solution. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2020, 124, 7682–7693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toksoy, A.; Pekcan, S.; Susam, A.; Erkan, D. S.; Algi, M. P.; Algi, F. , A generic platform for self-illuminating unimolecular systems enabling photodynamic therapy. Dyes and Pigments 2023, 219, 111577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.-H.; Yan, J.-L.; Tu, Y.-F. , Study on a Luminol-based Electrochemiluminescent Sensor for Label-Free DNA Sensing. Sensors 2010, 10, 9481–9492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Song, Z. , Study on the proteins-luminol binding by use of luminol as a fluorescence probe. Spectrochimica Acta - Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2013, 114, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodossiou, T.; Hothersall, J. S.; Woods, E. A.; Okkenhaug, K.; Jacobson, J.; MacRobert, A. J. , Firefly luciferin-activated rose bengal: In vitro photodynamic therapy by intracellular chemiluminescence in transgenic NIH 3T3 cells. Cancer Research 2003, 63, 1818–1821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ng, J.; Henriquez, N.; Kitchen, N.; Williams, N.; Novelli, M.; Oukrif, D.; MacRobert, A.; Bown, S. , Suppression of tumour growth from transplanted astrocytoma cells transfected with luciferase in mice by bioluminescence mediated, systemic, photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2024, 45, 103923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, J.; Henriquez, N.; MacRobert, A.; Kitchen, N.; Williams, N.; Bown, S. , Bioluminescence-activated photodynamic therapy for luciferase transfected, grade 4 astrocytoma cells in vitro. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2022, 38, 102856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboi, S.; Jin, T. , BRET-Based Dual-Color (Visible/Near-Infrared) Molecular Imaging Using a Quantum Dot/EGFP-Luciferase Conjugate. Methods Mol Biol 2022, 2525, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nishihara, R.; Niwa, K.; Tomita, T.; Kurita, R. , Coelenterazine Analogue with Human Serum Albumin-Specific Bioluminescence. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2020, 31, 2679–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, E.; Mizukami, S.; Ibata, K.; Miyawaki, A.; Kikuchi, K. , Development of luminescent coelenterazine derivatives activatable by β-galactosidase for monitoring dual gene expression. Chemistry 2013, 19, 14970–14976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Forward, S.; Kim, K. H.; Wu, Y.; Hui, J.; Kashiparekh, A.; Yun, S. H. , All-natural-molecule, bioluminescent photodynamic therapy results in complete tumor regression and prevents metastasis. Biomaterials 2023, 296, 122079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shramova, E. I.; Chumakov, S. P.; Shipunova, V. O.; Ryabova, A. V.; Telegin, G. B.; Kabashin, A. V.; Deyev, S. M.; Proshkina, G. M. , Genetically encoded BRET-activated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of deep-seated tumors. Light Sci Appl 2022, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shramova, E. I.; Filimonova, V. P.; Frolova, A. Y.; Pichkur, E. B.; Fedotov, V. R.; Konevega, A. L.; Deyev, S. M.; Proshkina, G. M. , HER2-specific liposomes loaded with proteinaceous BRET pair as a promising tool for targeted self-excited photodynamic therapy. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2023, 193, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shramova, E. I.; Frolova, A. Y.; Filimonova, V. P.; Deyev, S. M.; Proshkina, G. M. , System for Self-excited Targeted Photodynamic Therapy Based on the Multimodal Protein DARP-NanoLuc-SOPP3. Acta Naturae 2023, 15, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-W.; Yu, H.-P.; Lin, Y.-F.; Lai, P.-S. , Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer using luciferase-immobilized quantum dots for self-illuminated photodynamic therapy. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciscato, L. F. M. L.; Bartoloni, F. H.; Bastos, E. L.; Baader, W. J. , Direct Kinetic Observation of the Chemiexcitation Step in Peroxyoxalate Chemiluminescence. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 2009, 74, 8974–8979. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, M. , Advanced chemistry of dioxetane-based chemiluminescent substrates originating from bioluminescence. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C: Photochemistry Reviews 2004, 5, 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, J. C.; Kung, A. L. , In vivo imaging of endogenous enzyme activities using luminescent 1,2-dioxetane compounds. J Biomed Sci 2015, 22, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xue, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Niu, K. , Oxygen self-supplied nanoparticle for enhanced chemiexcited photodynamic therapy. Biomedical Materials 2024, 19, 015013. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Zhou, P.; Pan, W.; Li, N.; Tang, B. , A biomimetic nanoreactor for synergistic chemiexcited photodynamic therapy and starvation therapy against tumor metastasis. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 5044. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, D.; Wu, W.; Ji, S.; Chen, C.; Hu, F.; Kong, D.; Ding, D.; Liu, B. , Chemiluminescence-Guided Cancer Therapy Using a Chemiexcited Photosensitizer. Chem 2017, 3, 991–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama, T.; Narita, S.; Motoyoshiya, J. , The Hammett correlation between distyrylbenzene substituents and chemiluminescence efficiency providing various ρ-values for peroxyoxalate chemiluminescence of several oxalates. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry 2013, 252, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Bu, H.; Duan, X.; Li, H.; Bai, Y. , Host–Guest Interaction-Based Supramolecular Self-Assemblies for H2O2 Upregulation Augmented Chemiluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer-Induced Cancer Therapy. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2023, 15, 38264–38272. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.; Fang, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Xiao, S.; Yang, S.; Du, W.; Song, J. , NIR-II Self-Luminous Molecular Probe for In Vivo Inflammation Tracking and Cancer PDT Effect Self-Evaluating. Small 2023, 19, 2206666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, D.; Dhamecha, D.; Gonsalves, A.; Menon, J. U. , Ultrasound-Enhanced Chemiluminescence for Bioimaging. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Liu, W.; Wu, J.; Zheng, X.; Ge, J.; Ren, H.; Zhang, W.; Lee, C.-S.; Wang, P. , Ultrasound-Enhanced Self-Exciting Photodynamic Therapy Based on Hypocrellin B. Chemistry – An Asian Journal 2021, 16, 1221–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdus Subhan, M.; Torchilin, V. P. , Advances with antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer treatment. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2021, 169, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelley, J. V. , Cerenkov radiation and its applications. British Journal of Applied Physics 1955, 6, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, A. E.; Boschi, F. , Novel biomedical applications of Cerenkov radiation and radioluminescence imaging. Phys Med 2015, 31, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dothager, R. S.; Goiffon, R. J.; Jackson, E.; Harpstrite, S.; Piwnica-Worms, D. , Cerenkov radiation energy transfer (CRET) imaging: a novel method for optical imaging of PET isotopes in biological systems. PLoS One 2010, 5, e13300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, T. M.; Pratt, E. C.; Grimm, J. , Utilizing the power of Cerenkov light with nanotechnology. Nat Nanotechnol 2017, 12, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioret, V.; Bellaye, P.-S.; Bernhard, Y.; Moreau, M.; Guillemin, M.; Drouet, C.; Collin, B.; Decréau, R. A. , Cherenkov Radiation induced photodynamic therapy - repurposing older photosensitizers, and radionuclides. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2023, 44, 103816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonti, R.; Conson, M.; Del Vecchio, S. , PET/CT in radiation oncology. Semin Oncol 2019, 46, 202–209. [Google Scholar]

- Fueger, B. J.; Czernin, J.; Hildebrandt, I.; Tran, C.; Halpern, B. S.; Stout, D.; Phelps, M. E.; Weber, W. A. , Impact of animal handling on the results of 18F-FDG PET studies in mice. J Nucl Med 2006, 47, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gill, R. K.; Mitchell, G. S.; Cherry, S. R. , Computed Cerenkov luminescence yields for radionuclides used in biology and medicine. Physics in Medicine & Biology 2015, 60, 4263. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Li, J.; Wu, D.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, Y. , Chemistry and biological applications of photo-labile organic molecules. Chem Soc Rev 2010, 39, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Jiang, D.; Gai, Y.; Qian, R.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Jing, B.; Yang, B.; Lan, X.; An, R. , Chlorin e6-loaded goat milk-derived extracellular vesicles for Cerenkov luminescence-induced photodynamic therapy. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2023, 50, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, K.; Liu, H.; Ruan, Y.; Chen, R.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Tang, L.; Sun, X. , Self-Illuminating In Situ Hydrogel with Immune-Adjuvant Amplify Cerenkov Radiation-Induced Photodynamic Therapy. Chem Biomed Imaging 2024, 2, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhou, Z.; Pratx, G.; Chen, X.; Chen, H. , Nanoscintillator-Mediated X-Ray Induced Photodynamic Therapy for Deep-Seated Tumors: From Concept to Biomedical Applications. Theranostics 2020, 10, 1296–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Yu, X.; Li, W. , Recent Progress and Trends in X-ray-Induced Photodynamic Therapy with Low Radiation Doses. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 19691–19721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Huang, L.; Li, D.; Fan, W.; Han, G. , Direct Aqueous-Phase Synthesis of Sub-10 nm "Luminous Pearls" with Enhanced in Vivo Renewable Near-Infrared Persistent Luminescence. J Am Chem Soc 2015, 137, 5304–5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, L.; Li, F.; Liu, C.; Huang, M.; Li, J.; Gao, F.; Ruan, X.; Yang, D. , An Energy-Storing DNA-Based Nanocomplex for Laser-Free Photodynamic Therapy. Advanced Materials 2022, 34, 2109920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhang, R.; Guo, J.; Yang, D. , Energy-storing DNA-based hydrogel remodels tumor microenvironments for laser-free photodynamic immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2024, 309, 122620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).