Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

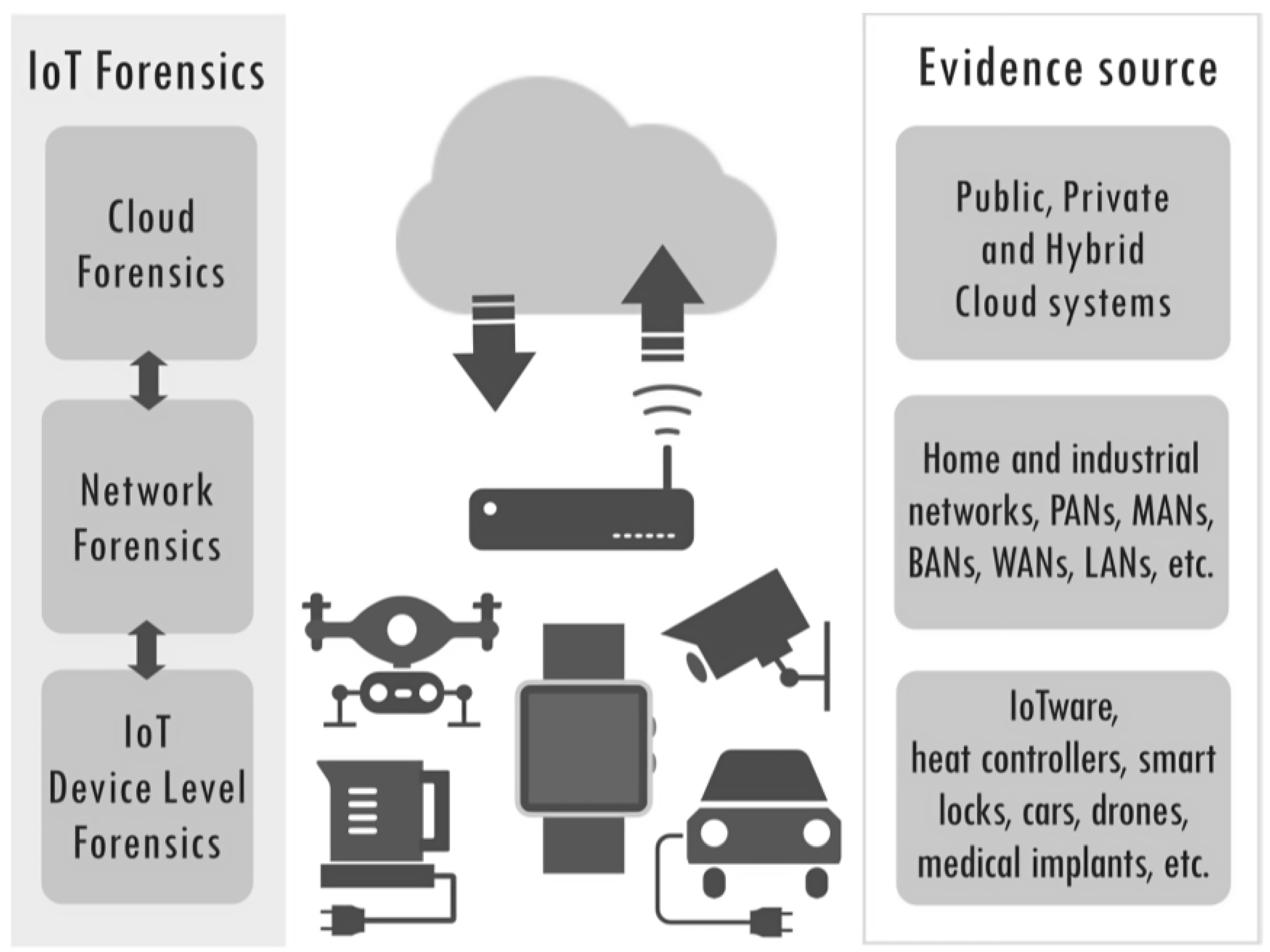

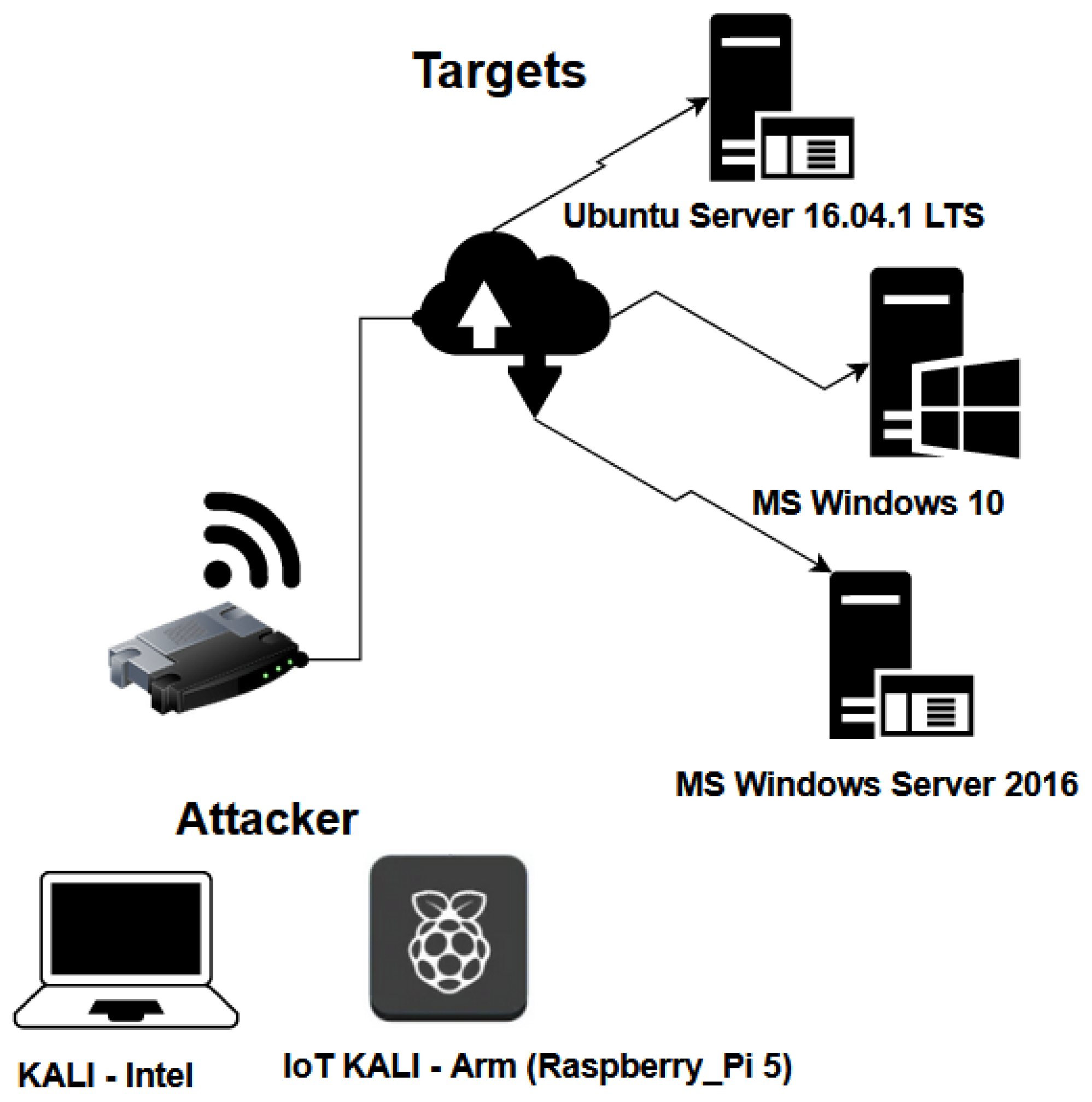

The proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices has introduced new challenges for digital forensic investigators due to their diverse architectures, communication protocols, and security vulnerabilities. This research paper presents a case study focusing on the forensic investigation of an IoT device, specifically a Raspberry Pi configured with Kali Linux as a hacker machine. The study aims to highlight differences and challenges in investigating weaponised IoT as well as establish a comprehensive methodology for analysing IoT devices involved in cyber incidents. The investigation begins with the acquisition of digital evidence from the Raspberry Pi device, including volatile memory and disc images. Various forensic tools and utilities are utilised to extract and analyse data, such as Exterro FTK and Magnet AXIOM, as well as open-source tools like Volatility, Wireshark, and Autopsy. The analysis involves examining system artefacts, logfiles, installed applications, and network connections to reconstruct the device's activity and identify potential evidence proving that the user perpetrated security breaches or malicious activities. The research results help improve IoT forensics by showing the best ways to look at IoT devices, especially those that are set up to be hacker machines. The case study demonstrates how the research results are helping to improve IoT forensic capabilities by showing the best ways to look at IoT devices, especially those that have been set up as hacker machines. The case study shows how forensic methods can be applied in IoT settings. It helps in creating guidelines, standards, and training for those who work as IoT forensic investigators. In the end, improving forensic readiness in IoT deployments is needed to keep essentials safe from cyber threats, keep digital evidence safe, and keep IoT ecosystems running smoothly, which protects the integrity of IoT ecosystems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Criminal-operated Linux systems (e.g., command-and-control servers).

- Abused or misused Linux systems (e.g., by suspect users)

- Imaged systems (e.g., dead disks)

- Standalone artefacts from Linux distributions

- Raspberry Pi devices running Kali Linux

- Metapackages from other platforms

1.1. Research Motivation

1.2. Research Questions

- RQ1: How do forensic processes differ between conventional computers and IoT Devices such as Raspberry Pi devices?

- RQ2: What are the key differences in terms of meaningful forensics artefacts between conventional computers and IoT Devices?

- RQ3: What are the current challenges and limitations in IoT Forensics and possible best practices to implement to overcome these challenges?

2. Literature Review

- Device Diversity: IoT devices come in various forms, including single-board computers (SBC), sensors, actuators, wearables, smart home appliances, and industrial controllers making the task address the diversity in device types, architectures, communication protocols, and operating systems challenging.

- Data Acquisition: Retrieving data from IoT devices while preserving its integrity and ensuring admissibility in legal proceedings is complex with many challenges such as accessing data stored in volatile memory, retrieving logs and configuration settings, and capturing network traffic.

- Distributed Nature: IoT environments involve numerous geographically distributed devices, making data collection and analysis challenging, especially with real-time data generation.

- Scalability Issues: The vast number of devices and data in IoT systems demands new forensic approaches to efficiently process and analyse large-scale information.

- Heterogeneous Protocols: IoT devices use various communication protocols, requiring forensic experts to understand and analyse diverse and often complex interactions.

- Privacy and Legal Concerns: IoT devices collect sensitive data, raising privacy issues. Forensic investigations must navigate legal frameworks to ensure evidence is admissible without violating privacy rights.

2.1. Comparison with Existing Research

2.2. TABLE I: Summary of Related Works

3. Methodology

| Algorithm 1 Forensic Analysis on Linux OS Using FTK and UFED. |

|

3.1. Testbed Design

3.2. Experimental Setup and Comparative Analysis

3.3. Dataset Elaboration

3.4. Data Capturing

3.5. Comparative Forensics Analysis

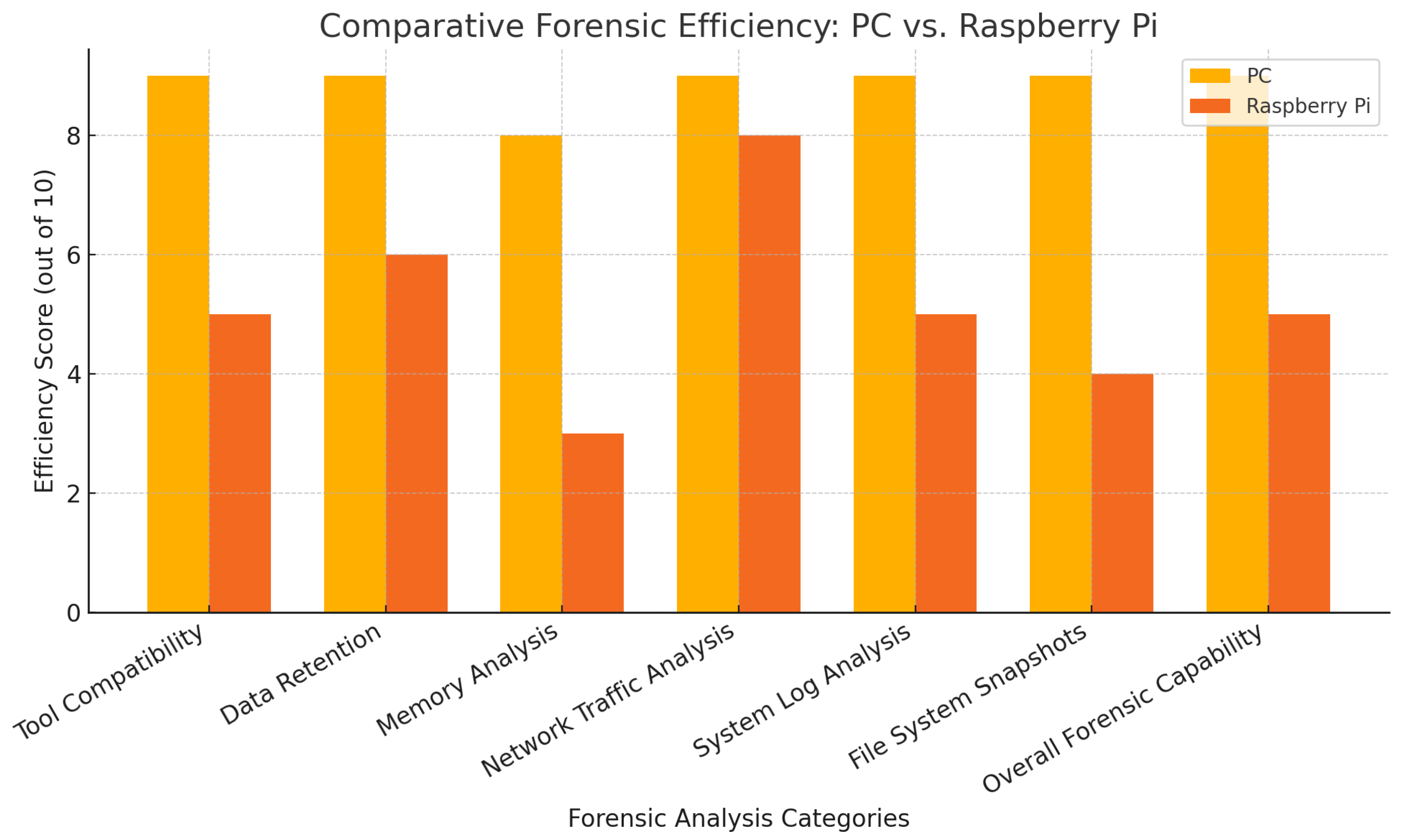

- Tool compatibility: The comparative forensic analysis highlighted several significant differences and challenges between conventional computers and IoT devices. Traditional PCs demonstrated high compatibility with most forensic tools, which facilitated a more robust forensic investigation. On the other hand, some of the forensics do not widely support the Raspberry Pi’s ARM architecture, leading to significant limitations in its analysis.

- Data Retention: Data retention also varied, with PCs retaining extensive logs and system data, allowing for a detailed forensic investigation. The Raspberry Pi, however, had limited storage and logging capabilities, which resulted in fewer retrievable forensic artefacts and challenges in performing thorough analyses.

- Memory Analysis: Memory analysis was another area where differences were evident. While memory analysis on PCs was effective, with tools like Volatility providing detailed data from memory dumps, the Raspberry Pi’s architecture and limited tool support made this process much more challenging, if not impossible.

- network traffic analysis: Network traffic analysis was consistent across both devices, with Wireshark effectively capturing relevant data. However, the contextual information provided by logs and memory analysis was more detailed for the PC, offering a more comprehensive view of the attacks.

- system log analysis: System log analysis further underscored the differences, with PCs offering comprehensive and detailed logs that enabled deeper forensic examinations. In contrast, the Raspberry Pi provided limited logs, restricting the scope of analysis.

- file system snapshots: Finally. While PCs allowed for detailed file system snapshots before and after the attacks, revealing significant changes, the Raspberry Pi’s limited storage capacity resulted in fewer detectable changes, further constraining forensic analysis.

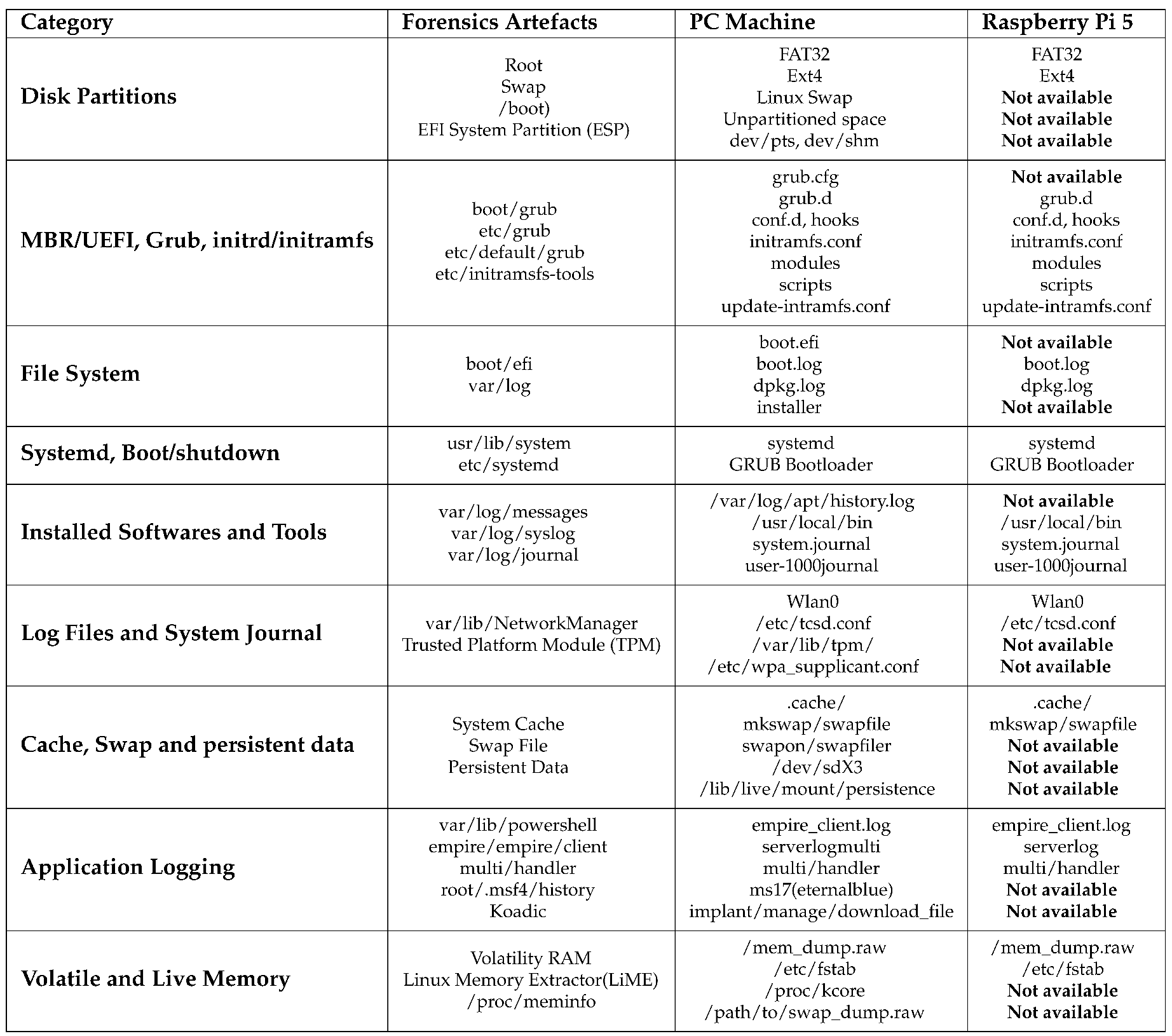

3.5.1. DisPartitions of the File System

3.5.2. MRBF/EFI/Config/Initramfs Files

3.5.3. File System: Boot/EFI Logs

3.5.4. Systemd Boot/Shutdown

3.5.5. Comparative Forensics Analysis Highlighting Main Similarities and Differences

3.5.6. Installed Software and System Logbook

3.5.7. Network Log Files

3.5.8. Cache, Swap, and Persisted Data

3.5.9. Other Applications Logging

3.5.10. Volatile Memory (RAM)

4. Research Findings and Discussion

4.1. Key Differences Between PC and Raspberry Pi

4.2. Comparative Forensic Performance Evaluation

4.3. Summary of the Overall Forensics Investigation Difference

4.4. Challenges with Raspberry Pi

4.5. Edge and Fog forensic issues

4.6. Addressing Research Questions

- Tool Compatibility: Many existing forensic tools are not compatible with the diverse architectures and operating systems used by IoT devices, such as the ARCH architecture in Raspberry Pi.

- Data Retention and Storage: IoT devices typically have limited storage capacity and simplified logging mechanisms, which result in insufficient forensic data retention.

- Live Memory Analysis: Acquiring and analysing live memory from IoT devices is challenging due to tool incompatibility and the technical complexity of configuring existing tools for different architectures.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wanic, E. and Rowe, N. (2018). Assessing Deterrence Optinos for Cyber Weapons. in 2018 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), pp. 13–18. [CrossRef]

- Kebande, V.R., 2022. Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) forensics: The forgotten concept in the race towards industry 4.0. Forensic Science International: Reports, 5, p.100257. [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, M.S., Saleem, Y., Almogren, A., Arshad, J., Jaffery, M.H., Rehman, A.U., Shafiq, M. and Hamam, H., 2022. Forensic analysis on Internet of Things (IoT) device using machine-to-machine (M2M) framework. Electronics, 11(7), p.1126. [CrossRef]

- Y. Salem, M. Owda and A. Y. Owda. A Comprehensive Review of Digital Forensics Frameworks for Internet of Things (IoT) Devices. 2023 International Conference on Information Technology (ICIT), Amman, Jordan, 2023, pp. 89-96. [CrossRef]

- Dunsin, D., Ghanem, M.C., Ouazzane, K. and Vassilev, V., 2024. A comprehensive analysis of the role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in modern digital forensics and incident response. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, 48, p.301675. [CrossRef]

- Nelufule, N., Singano, T., Masemola, K., Shadung, D., Nkwe, B., Mokoena, J.2024. An Adaptive Digital Forensic Framework for the Evolving Digital Landscape in Industry 4.0 and 5.0, 2024 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT), pp.1686-1693, 202. [CrossRef]

- Dunsin, D., Ghanem, M.C., Ouazzane, K. and Vassilev, V., 2025. Reinforcement learning for an efficient and effective malware investigation during cyber Incident response. High-Confidence Computing, p.100299. [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.C., Mulvihill, P., Ouazzane, K., Djemai, R. and Dunsin, D., 2023. D2WFP: a novel protocol for forensically identifying, extracting, and analysing deep and dark web browsing activities. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 3(4), pp.808-829. [CrossRef]

- T. Bakhshi. Forensic of Things: Revisiting Digital Forensic Investigations in Internet of Things. 2019 4th International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering, Sciences and Technology (ICEEST), Karachi, Pakistan, 2019, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Farzaan, M.A.M., Ghanem, M.C., El-Hajjar, A. and Ratnayake, D.N., 2024. AI-Enabled System for Efficient and Effective Cyber Incident Detection and Response in Cloud Environments. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.05602.

- Stoyanova, M., Nikoloudakis, Y., Panagiotakis, S., Pallis, E. and Markakis, E.K., 2020. A survey on the Internet of Things (IoT) forensics: challenges, approaches, and open issues. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 22(2), pp.1191-1221. [CrossRef]

- Yevdokymenko, M., Mohamed, E. and Onwuakpa, P. (2017) ’Ethical hacking and penetration testing using Raspberry PI’, in 2017 4th International Scientific-Practical Conference Problems of Info-communications. Science and Technology (PIC S&T), pp. 179–181. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Bakry, B. B., Bt Adenan, A. R. and Mohd Yussoff, Y. B. (2022) ‘Security Attack on IoT RelatedDevices Using Raspberry Pi and Kali Linux’, in 2022 International Conference on Computer and Drone Applications (IConDA), pp. 40–45. [CrossRef]

- Yudha, F., Ramadhani, E. and Komaryan, R. M. (2021) ’A Prototype of Portable Digital Forensics Imaging Tools using Raspberry Device’, IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 1077(1), p. 012064. [CrossRef]

- Cusack, B., Tian, Z. and Kyaw, A.K., 2017. Identifying DOS and DDOS attack origin: IP traceback methods comparison and evaluation for IoT. In Interoperability, Safety and Security in IoT: Second International Conference, InterIoT 2016 and Third International Conference, SaSeIoT 2016, Paris, France, October 26-27, 2016, (pp. 127-138). [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, A. K., Chen, Y. and Joseph, J. (2015) ’Pi-IDS: evaluation of open-source intrusion detection systems on Raspberry Pi 2’, in 2015 Second International Conference on Information Security and Cyber Forensics (InfoSec). Cape Town: IEEE, pp. 165–170. [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.C., Chen, T.M., Ferrag, M.A. and Kettouche, M.E., 2023. ESASCF: expertise extraction, generalization and reply framework for optimized automation of network security compliance. IEEE Access, 11, pp.129840-129853. [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, O. and Asif, R. (2019) ’Drone Hacking with Raspberry-Pi 3 and WiFi Pineapple: Security and Privacy Threats for the Internet-of-Things’, in 2019 1st International Conference on Unmanned Vehicle Systems-Oman (UVS). Muscat, Oman: IEEE, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Alam M. N. and Kabir, M. S. Forensics in the Internet of Things: Application Specific Investigation Model, Challenges and Future Directions, 2023. 4th International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), Belgaum, India, 2023, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Torabi, S., Bou-Harb, E., Assi, C. and Debbabi, M., 2020. A scalable platform for enabling the forensic investigation of exploited IoT devices and their generated unsolicited activities. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, 32, p.300922. [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.M. and Burmester, M. (2021). Cyber Forensics on Internet of Things: Slicing and Dicing Raspberry Pi. International Journal of Cyber Forensics and Advanced Threat Investigations, 2(1). pp.29–49. [CrossRef]

- Premsankar, G., Di Francesco, M. and Taleb, T., 2018. Edge computing for the Internet of Things: A case study. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 5(2), pp.1275-1284. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8289317.

- Cook, M., Marnerides, A., Johnson, C. and Pezaros, D., 2023. A survey on industrial control system digital forensics: challenges, advances and future directions. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. [CrossRef]

- Case, A. and Richard III, G.G., 2017. Memory forensics: The path forward. Digital investigation, 20, pp.23-33. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Year | IoT | Digital Forensics | Offensive Security | Technique & Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | 2018 | ✗ | ✔ | ✗ | Evaluation and proposal for strategies to deter cyber attacks, particularly those initiated by nation-states. Differences between Cyber and Conventional Weapons, motivation and objectives of cyber operations, deterrence methods (evaluation and effectiveness) |

| [11] | 2020 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Surveying challenges, approaches, and open issues in the field of IoT forensic, research broadly highlighted differences and similarities between mobile and IoT forensic, and tackled forensic by design and digital forensic as a service (DFaaS). |

| [12] | 2018 | ✔ | ✗ | ✔ | Comprehensive overview of ethical hacking practices, emphasizing the use of low-cost, portable hardware like the Raspberry Pi. Define Ethical Hacking, penetration testing, reconnaissance techniques, and remote penetration testing with the RPI combining theoretical and practical aspects. |

| [13] | 2022 | ✔ | ✔ | ✗ | The article focuses on demonstrating the vulnerability of IoT devices using a Raspberry Pi 4 with Raspberry Pi OS. Attacks with Kali Linux and automated tools are employed highlighting the security concerns associated with IoT devices. The methodology of executing the attacks is discussed emphasising the importance of securing IoT devices to prevent exploitation. |

| [14] | 2021 | ✔ | ✗ | ✔ | The paper focuses on developing a low-cost, and portable digital forensic imaging tool using the RPI. The goal is to create an image that can be used and analysed as reliable evidence. |

| [16] | 2015 | ✔ | ✔ | ✗ | Focus on evaluating and comparing the performance, efficiency, and efficacy of two open-source intrusion detection systems (IDSs) running in the Raspberry Pi 2 (Model B). Aim to determine their suitability for use in cost-sensitive network environments. |

| [18] | 2019 | ✔ | ✔ | ✗ | Identify and exploit vulnerabilities in two commercial drones. Aim to demonstrate the security weakness present in these drones by using the Raspberry Pi as an automated tool to interact with the drones. |

|

| Aspect | PC | Raspberry Pi |

|---|---|---|

| Tool Compatibility | High - Most tools work effectively | Low - Many tools face compatibility issues |

| Data Retention | Extensive logs and system data | Limited logs and storage capacity |

| Memory Analysis | Effective with rich data from memory dumps | Challenging due to tool configuration issues |

| Network Traffic Analysis | Detailed and consistent analysis | Similar results but less contextual data |

| System Log Analysis | Comprehensive and detailed | Limited and less detailed |

| File System Snapshots | Detailed snapshots before and after attacks | Limited changes detected due to small storage |

| Overall Forensic Capability | High - Robust forensic analysis possible | Low - Significant limitations in forensic analysis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).