Submitted:

01 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Sample and Experimental Method

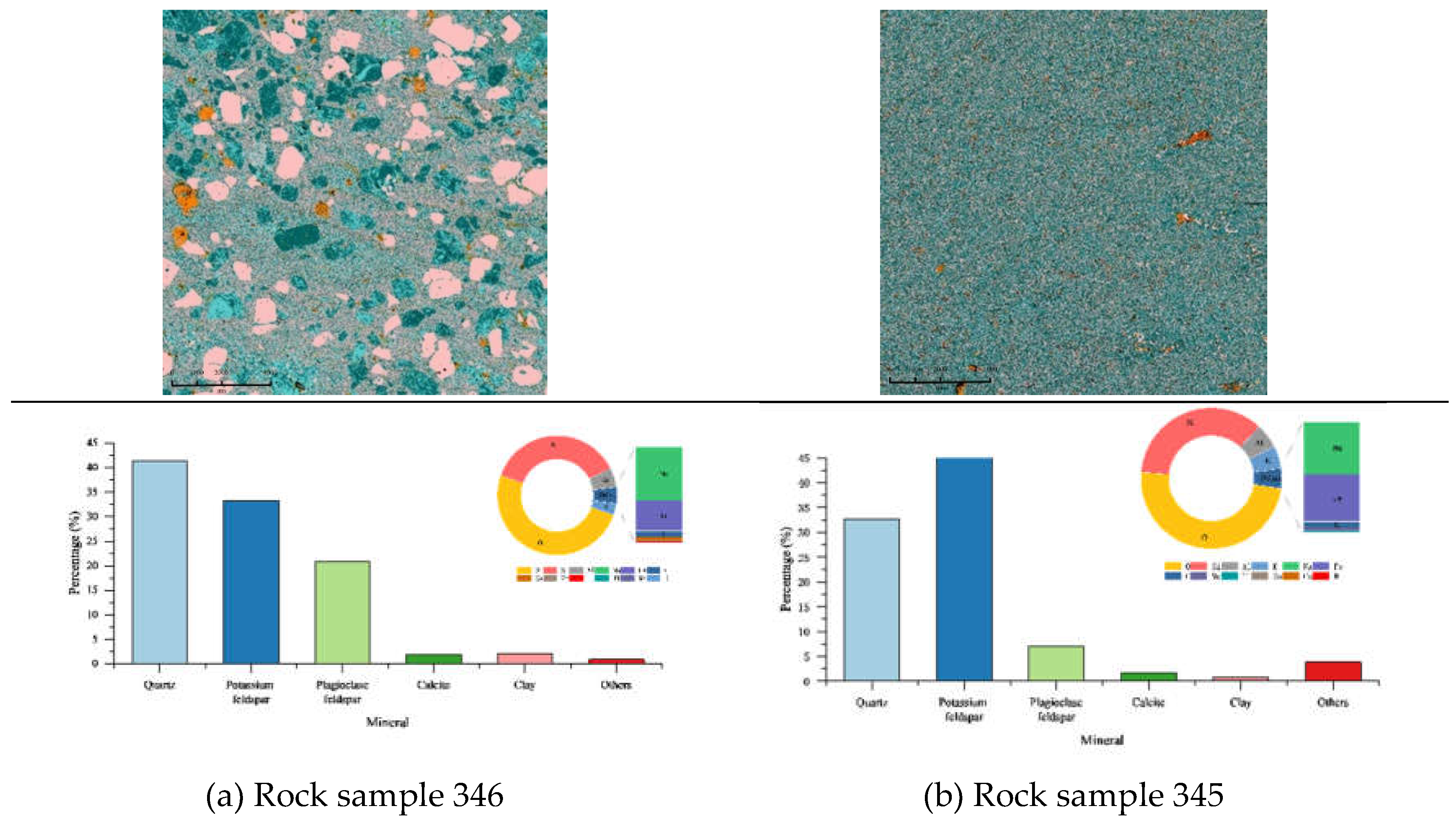

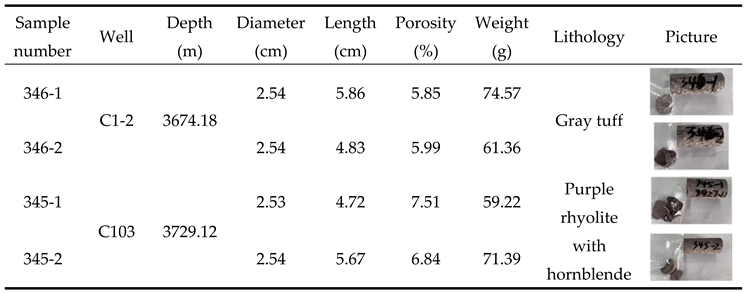

2.1. Experimental Sample

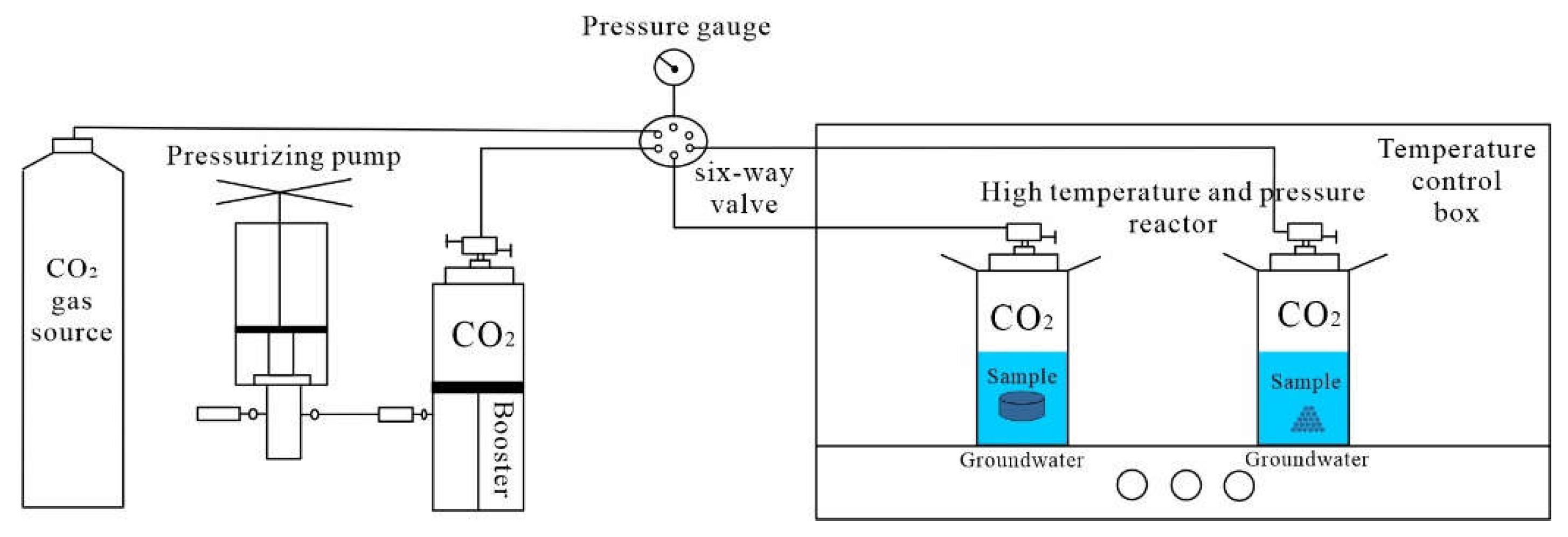

2.2. Laboratory Equipment

2.3. Experimental Process

2.3.1. Subsubsection

| Sample | Na+ | K+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | Cationic total | pH |

| C1-2 | 6695.44 | 2134.42 | 10.44 | 25.93 | 8866.24 | 7.29 |

| C103 | 6836.09 | 1973.89 | 7.65 | 14.54 | 8832.17 | 7.4 |

| Sample | Cl- | SO42- | HCO3- | CO32- | Anionic total | Water-based |

| C1-2 | 3594.99 | 324.03 | 17526.21 | 812.22 | 22257.45 | NaHCO3 |

| C103 | 2999.76 | 575.9 | 17579.07 | 654.36 | 21758.06 | NaHCO3 |

| Na+ | K+ | Mg2+ | Ca2+ | Cationic total | pH | |

| Simulated groundwater | 6925.25 | 2028.27 | 21.3319 | 14.9311 | 8989.783 | 7.34 |

| Cl- | SO42- | HCO3- | CO32- | Anionic total | Water-based | |

| Simulated groundwater | 2407.23 | 398.307 | 21044.78 | 735.12 | 23850.32 | NaHCO3 |

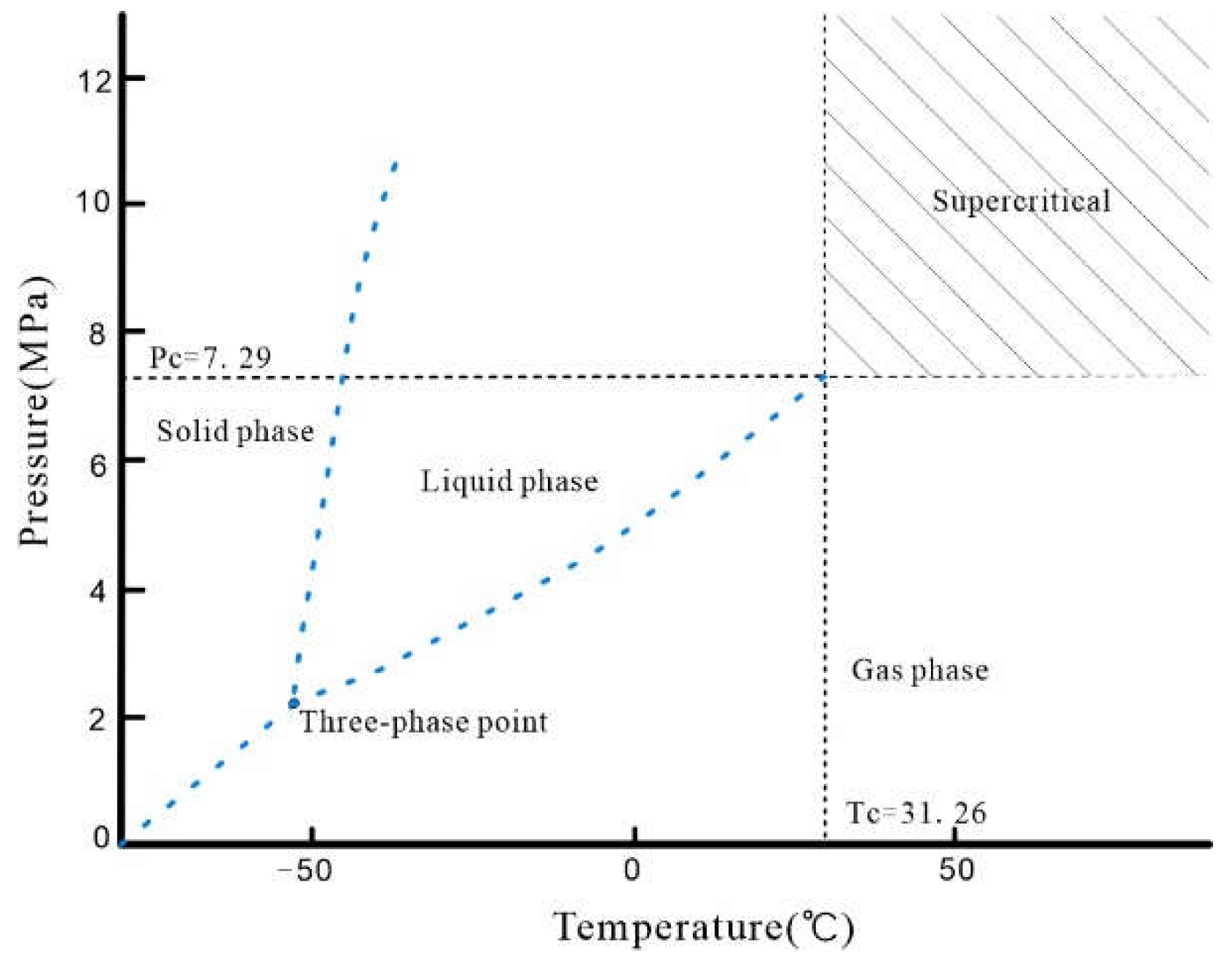

2.3.2. Design of a Solution Reaction Experiment

3. Analysis of Experimental Results

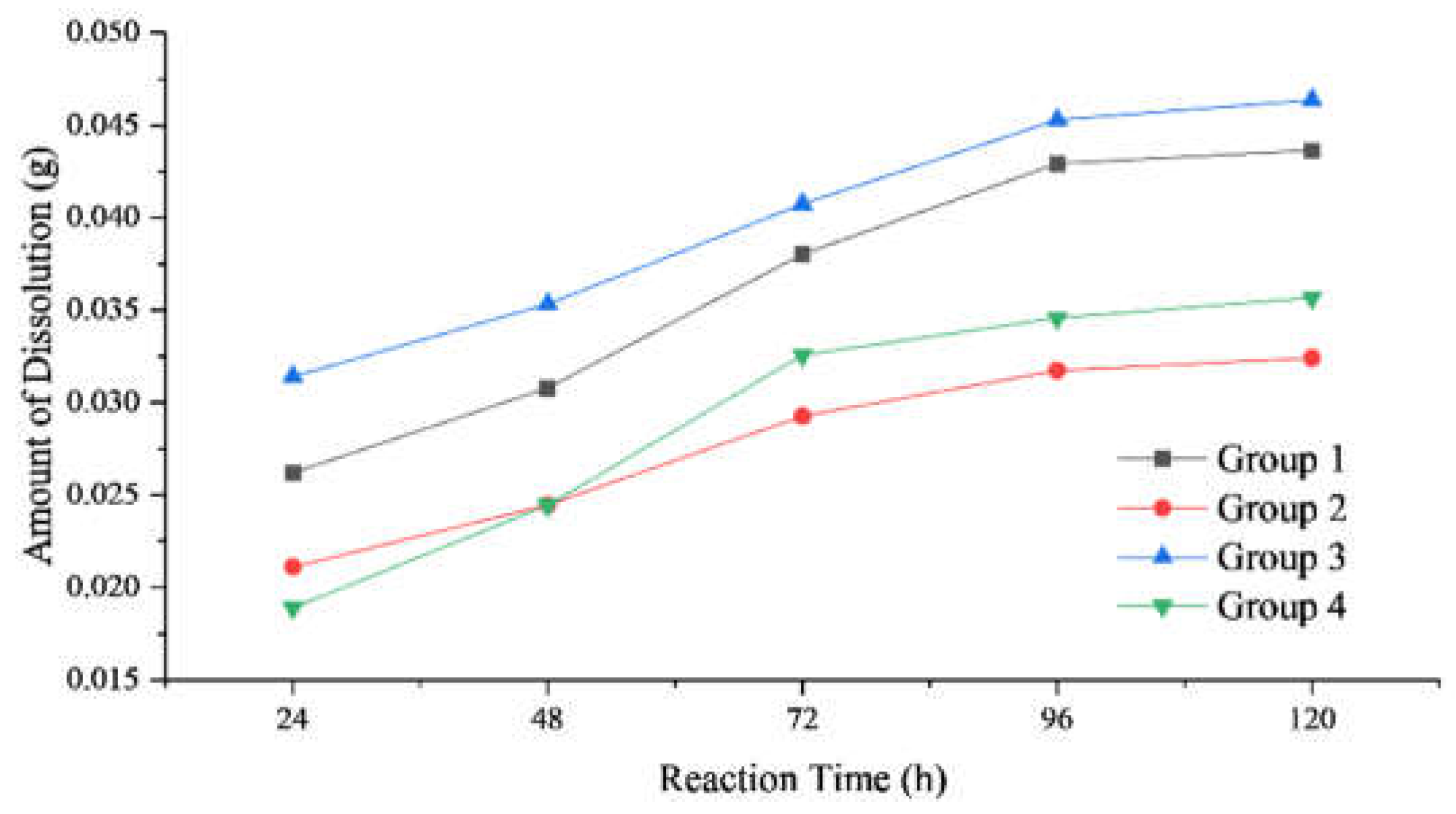

3.1. Experimental Response Equilibrium Time Determination

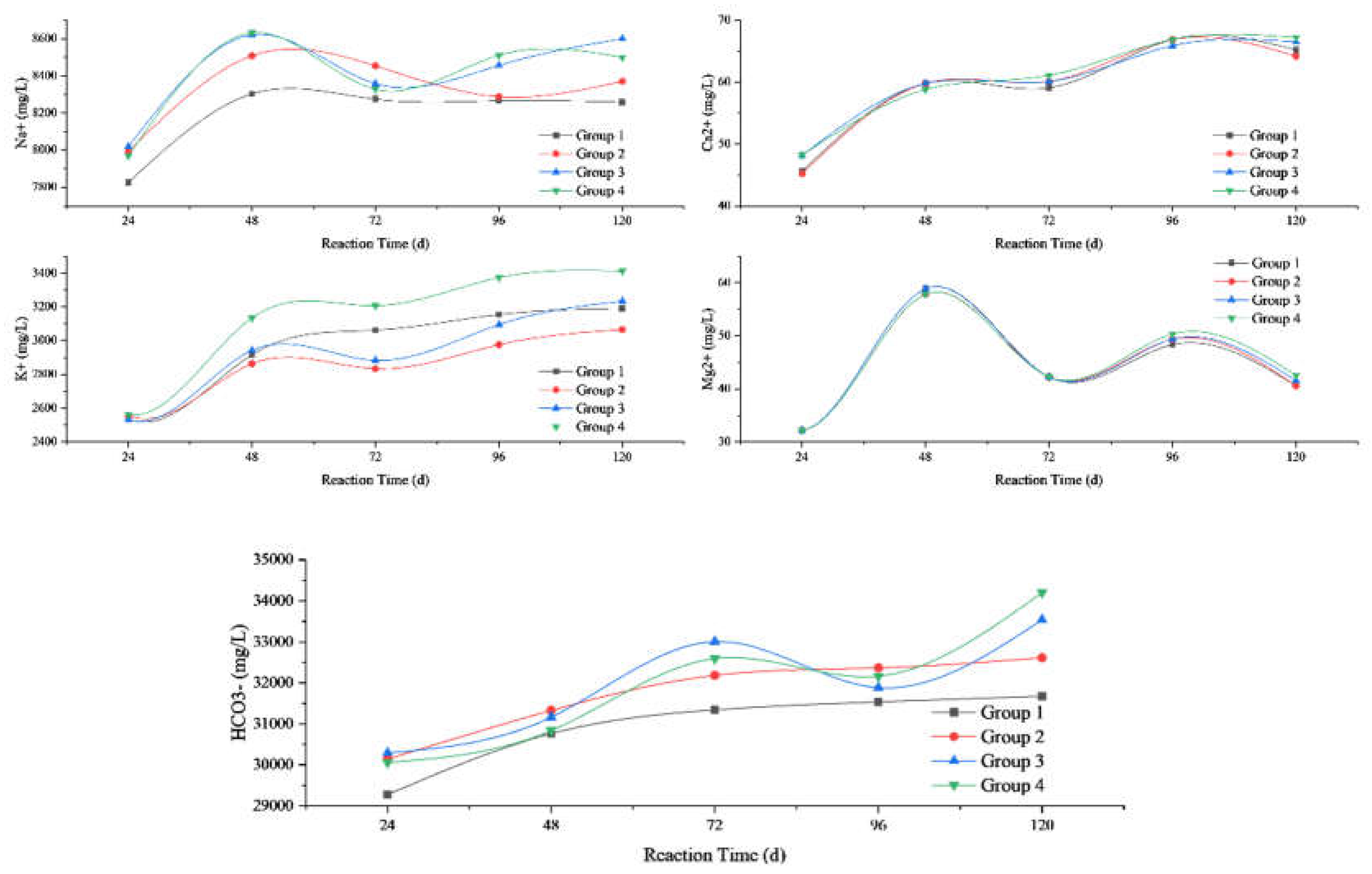

3.2. Variations in the Mass Concentration of Ions and pH Value of Groundwater

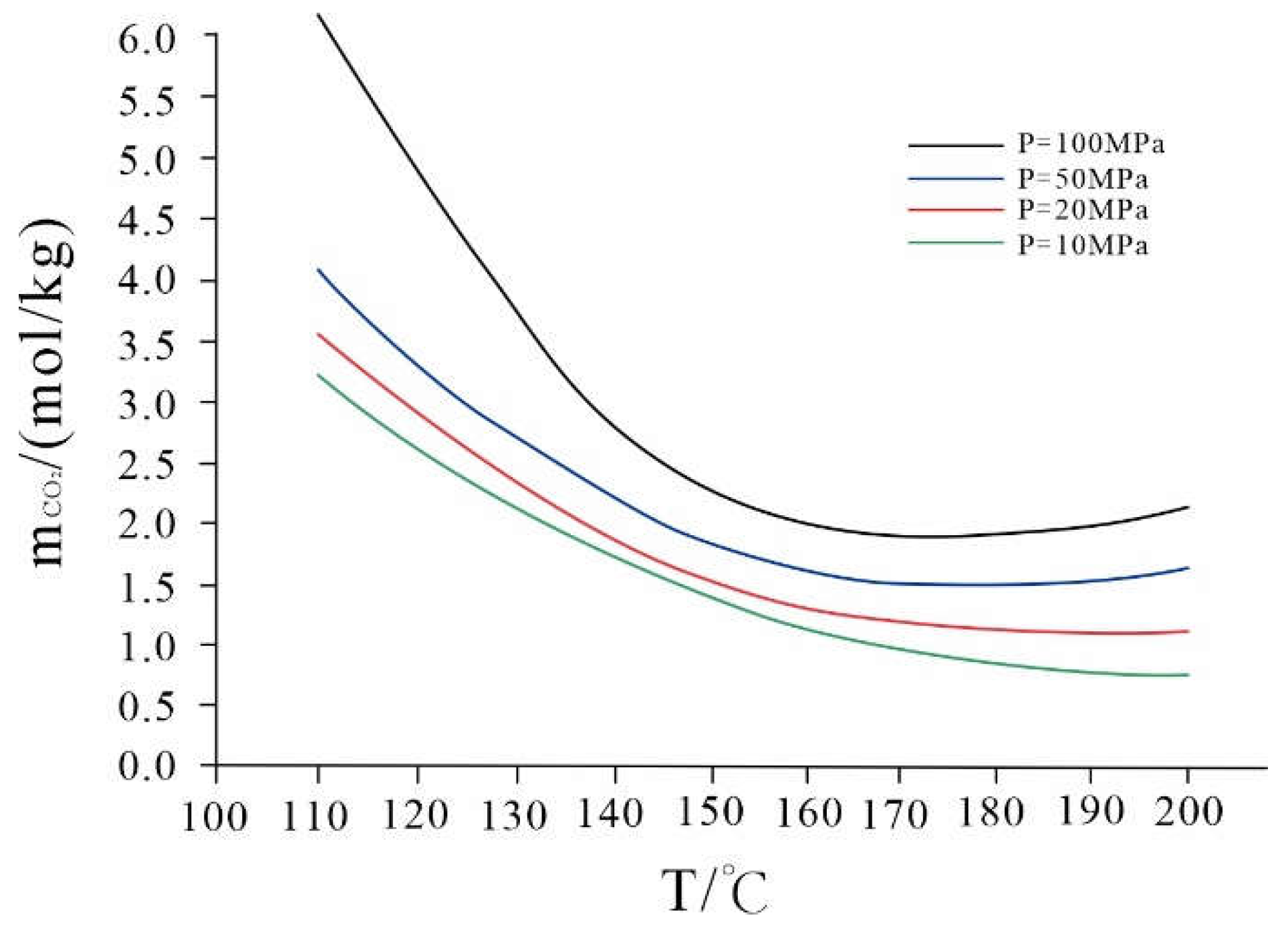

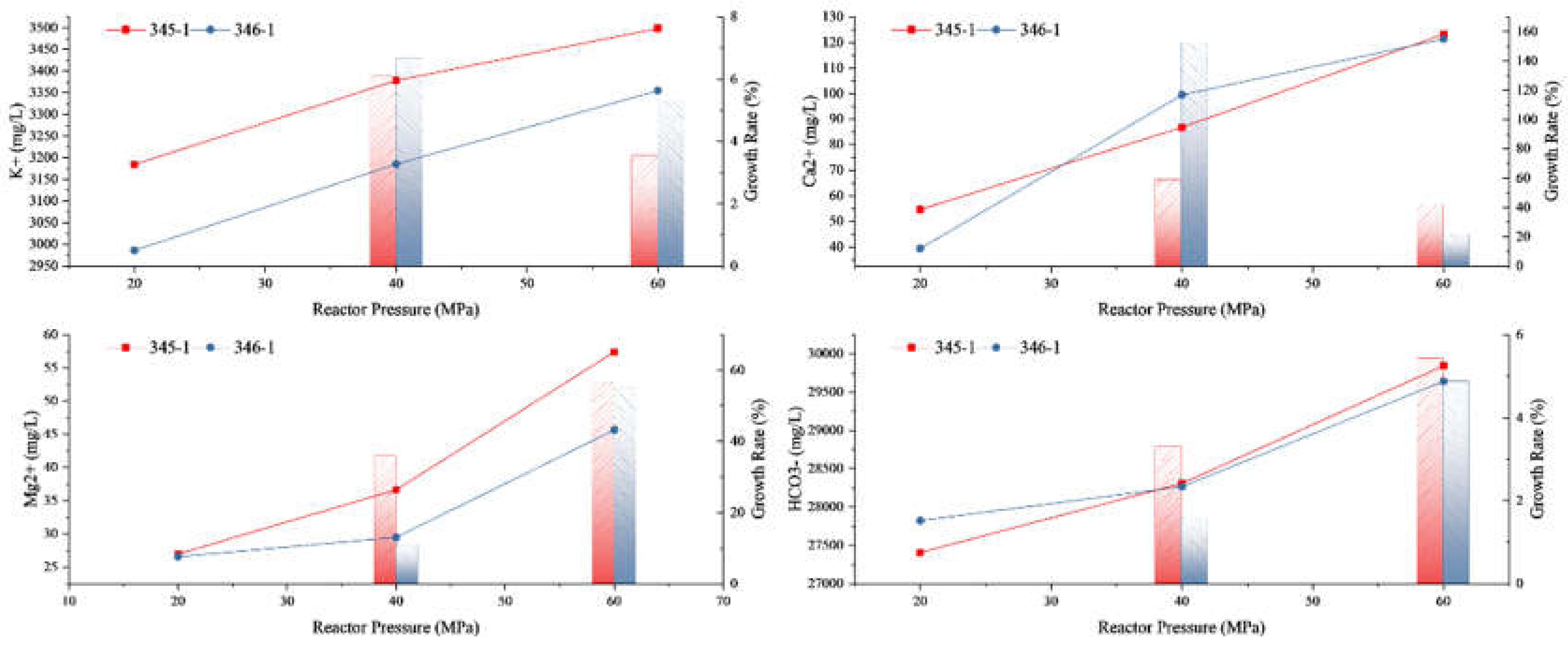

3.2.1. The Influence of Different Experimental Pressures on the Solution Reaction

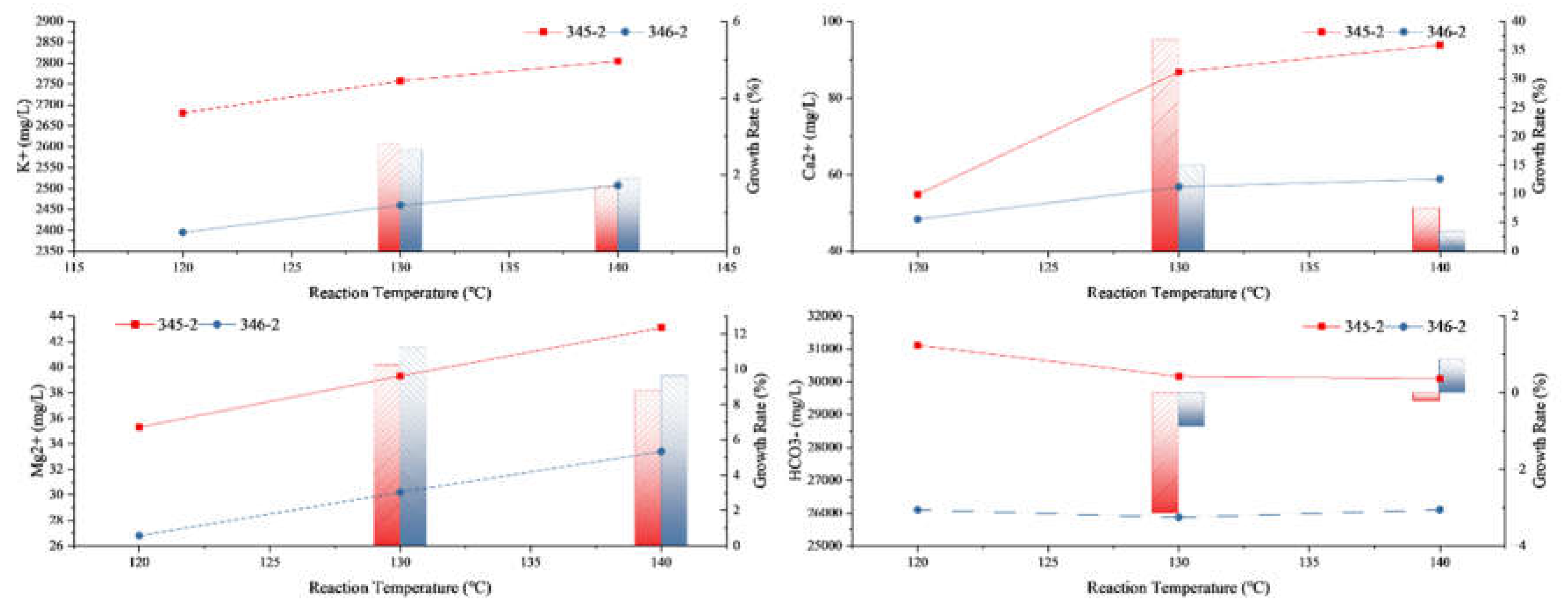

3.2.2. The Influence of Different Experimental Temperatures on the Water Rock Reaction

3.3. Variations in the Microscopic Surface Features of Rock Samples

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Dissolution Mechanism

4.2. Experimental Geological Significance

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- TAKAYA Y, NAKAMURA K, KATO Y. Dissolution of altered tuffaceous rocks under conditions relevant for CO2 storage. Applied Geochemistry 2015, 58, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHAO Y, WU S, CHEN Y, et al. CO2-Water-Rock Interaction and Pore Structure Evolution of the Tight Sandstones of the Quantou Formation, Songliao Basin. Energies, 2022; 15.

- BERTIER P, SWENNEN R, LAENEN B, et al. Experimental identification of CO2-water-rock interactions caused by sequestration of CO2 in Westphalian and Buntsandstein sandstones of the Campine Basin (NE-Belgium). Journal of Geochemical Exploration 2006, 89, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HELLEVANG H, PHAM V T H, AAGAARD P. Kinetic modelling of CO2-water-rock interactions. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2013, 15, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHANG L, ZHANG T, ZHAO Y, et al. A review of interaction mechanisms and microscopic simulation methods for CO2-water-rock system. Petroleum Exploration and Development 2024, 51, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JENSEN G K, S. Weyburn oilfield core assessment investigating cores from pre and post CO2 injection: Determining the impact of CO2 on the reservoir. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2016, 54, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FARQUHAR S M, PEARCE J K, DAWSON G K W, et al. A fresh approach to investigating CO2 storage: Experimental CO2-water-rock interactions in a low-salinity reservoir system. Chemical Geology 2015, 399, 98–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOU W, LIN M, JIANG W, et al. Importance of diagenetic heterogeneity in Chang 7 sandstones for modeling CO2-water-rock interactions. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, 2024; 132.

- LI H, XIE L, REN L, et al. Influence of CO2-water-rock interactions on the fracture properties of sandstone from the Triassic Xujiahe Formation, Sichuan Basin. Acta Geophysica 2021, 69, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WANG W, YAN Z, CHEN D, et al. The mechanism of mineral dissolution and its impact on pore evolution of CO2 flooding in tight sandstone: A case study from the Chang 7 member of the Triassic Yanchang formation in the Ordos Basin, China. Geoenergy Science and Engineering, 2024; 235.

- ZUO Q, ZHANG Y, ZHANG M, et al. Numerical Simulation of CO2 Dissolution and Mineralization Storage Considering CO2-Water-Rock Reaction in Aquifers. Acs Omega, 2023.

- LIU D, LI Y, AGARWAL R K. Numerical simulation of long-term storage of CO2 in Yanchang shale reservoir of the Ordos basin in China. Chemical Geology 2016, 440, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIGAND M, CAREY J W, SCHUTTA H, et al. Geochemical effects of CO2 sequestration in sandstones under simulated in situ conditions of deep saline aquifers. Applied Geochemistry 2008, 23, 2735–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WANDREY M, FISCHER S, ZEMKE K, et al. Monitoring petrophysical, mineralogical, geochemical and microbiological effects of CO2 exposure - Results of long-term experiments under in situ conditions[C]. 10th International Conference on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies 2011, 3644-3650.

- KETZER J M, IGLESIAS R, EINLOFT S, et al. Water-rock- CO2 interactions in saline aquifers aimed for carbon dioxide storage: Experimental and numerical modeling studies of the Rio Bonito Formation (Permian), southern Brazil. Applied Geochemistry 2009, 24, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIQUEIRA T A, IGLESIAS R S, KETZER J M. Carbon dioxide injection in carbonate reservoirs - a review of CO2-water-rock interaction studies. Greenhouse Gases-Science and Technology 2017, 7, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HEINEMANN N, WILKINSON M, HASZELDINE R S, et al. CO2 sequestration in a UK North Sea analogue for geological carbon storage. Geology 2013, 41, 411–414. [Google Scholar]

- AHMAT K, CHENG J, YU Y, et al. CO2-Water-Rock Interactions in Carbonate Formations at the Tazhong Uplift, Tarim Basin, China. Minerals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHEN B, LI Q, TAN Y, ALVI I H. Dissolution and Deformation Characteristics of Limestones Containing Different Calcite and Dolomite Content Induced by CO2-Water-Rock Interaction. Acta Geologica Sinica-English Edition 2023, 97, 956–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CUI G, ZHANG L, TAN C, et al. Injection of supercritical CO2 for geothermal exploitation from sandstone and carbonate reservoirs: CO2-water-rock interactions and their effects. Journal of CO2 Utilization 2017, 20, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WANG T, WANG H, ZHANG F, XU T. Simulation of CO2-water-rock interactions on geologic CO2 sequestration under geological conditions of China. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2013, 76, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EGERMANN P, LENORMAND R. A new methodology to evaluate the impact of localized heterogeneity on petrophysical parameters (kri, Pci) applied to carbonate rocks. Petrophysics 2005, 46, 335–345. [Google Scholar]

- PARK J, CHOI B-Y, LEE M, YANG M. Porosity changes due to analcime in a basaltic tuff from the Janggi Basin, Korea: experimental and geochemical modeling study of CO2-water-rock interactions. Environmental Earth Sciences 2021, 80. [Google Scholar]

- RENDEL P M, WOLFF-BOENISCH D, GAVRIELI I, GANOR J. A novel experimental system for the exploration of CO2-water-rock interactions under conditions relevant to CO2 geological storage. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 334, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MA B, CAO Y, ZHANG Y, ERIKSSON K A. Role of CO2-water-rock interactions and implications for CO2 sequestration in Eocene deeply buried sandstones in the Bonan Sag, eastern Bohai Bay Basin, China. Chemical Geology, 2020; 541.

- LIN H, FUJII T, TAKISAWA R, et al. Experimental evaluation of interactions in supercritical CO2/water/rock minerals system under geologic CO2 sequestration conditions. Journal of Materials Science 2008, 43, 2307–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J B C, M S, D C. Magmatic CO2 in natural gases in the Permian Basin,West Texas: identifying the regional source and filling history. Geochem Explor, 2020; 69~70, 59–63.

| Rock Samples | Reaction Temperature (℃) |

Reactive Pressure (MPa) |

Weight of Rock Sample (Before) (g) |

Porosity (Anhydrous ethanol) (%) |

Reaction Time (h) |

| 345-1-1 | 130 | 20 | 12.23 | 7.20 | 96 |

| 345-1-2 | 130 | 40 | 13.11 | 7.09 | 96 |

| 345-1-3 | 130 | 60 | 12.30 | 6.56 | 96 |

| 345-2-1 | 120 | 40 | 12.38 | 6.65 | 96 |

| 345-2-2 | 130 | 40 | 12.50 | 6.42 | 96 |

| 345-2-3 | 140 | 40 | 12.46 | 6.49 | 96 |

| 346-1-1 | 130 | 20 | 12.57 | 6.03 | 96 |

| 346-1-2 | 130 | 40 | 12.65 | 6.22 | 96 |

| 346-1-3 | 130 | 60 | 12.54 | 6.13 | 96 |

| 346-2-1 | 120 | 40 | 12.60 | 5.95 | 96 |

| 346-2-2 | 130 | 40 | 12.55 | 6.20 | 96 |

| 346-2-3 | 140 | 40 | 12.42 | 5.84 | 96 |

| Rock Samples | Reactive Pressure (MPa) | Rock Sample Quality (Before) (g) |

Rock Sample Quality (After) (g) |

Amount of Dissolution (g) |

Improved Porosity (%) | Pre-Reaction (pH) | After Reaction (pH) |

| 345-1 | 20 | 12.23 | 12.01 | 0.2254 | 4.43 | 3.26 | 7.33 |

| 40 | 13.11 | 12.86 | 0.2489 | 4.57 | 3.14 | 7.35 | |

| 60 | 12.30 | 12.04 | 0.2638 | 5.18 | 3.07 | 7.53 | |

| 346-1 | 20 | 12.57 | 12.37 | 0.1965 | 3.72 | 3.26 | 7.28 |

| 40 | 12.65 | 12.42 | 0.2297 | 4.39 | 3.14 | 7.32 | |

| 60 | 12.54 | 12.30 | 0.2449 | 4.66 | 3.07 | 7.51 |

| Rock Samples | Reaction Temperature ℃ |

Rock Sample Quality (Before) (g) |

Rock Sample Quality (After) (g) |

Amount of Dissolution (g) |

Improved Porosity (%) | Pre-Reaction (pH) | After Reaction (pH) |

| 345-2 | 120 | 12.38 | 12.09 | 0.2803 | 4.37% | 3.11 | 7.79 |

| 130 | 12.50 | 12.24 | 0.2645 | 4.21% | 3.14 | 7.69 | |

| 140 | 12.46 | 12.23 | 0.2242 | 3.04% | 3.18 | 7.62 | |

| 346-2 | 120 | 12.60 | 12.34 | 0.2581 | 5.01% | 3.11 | 7.33 |

| 130 | 12.55 | 12.31 | 0.2345 | 4.55% | 3.14 | 7.33 | |

| 140 | 12.42 | 12.19 | 0.2274 | 4.42% | 3.18 | 7.36 |

| Reaction Equation | ||

| (1) | ||

| (2) | ||

| (3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).