Submitted:

05 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Roles of Endothelial Cells, smooth Muscle Cells and Macrophages in Atherosclerosis

2.1. Endothelial Cells

2.2. Smooth Muscle Cells

2.3. Endothelial Cells

3. Crosstalk

3.1. Crosstalk Between Endothelial Cells and Smooth Muscle Cells

3.1.1. Direct Contact

3.1.2. Paracrine Secretion

Vasoactive Substance

Extracellular Vesicle

3.1.3. Extracellular Matrix

3.2. Crosstalk Between Endothelial Cells and Macrophages

3.2.1. Direct Contact

3.2.2. Paracrine Secretion

Vasoactive Substance

Extracellular Vesicle

3.2.3. Extracellular Matrix

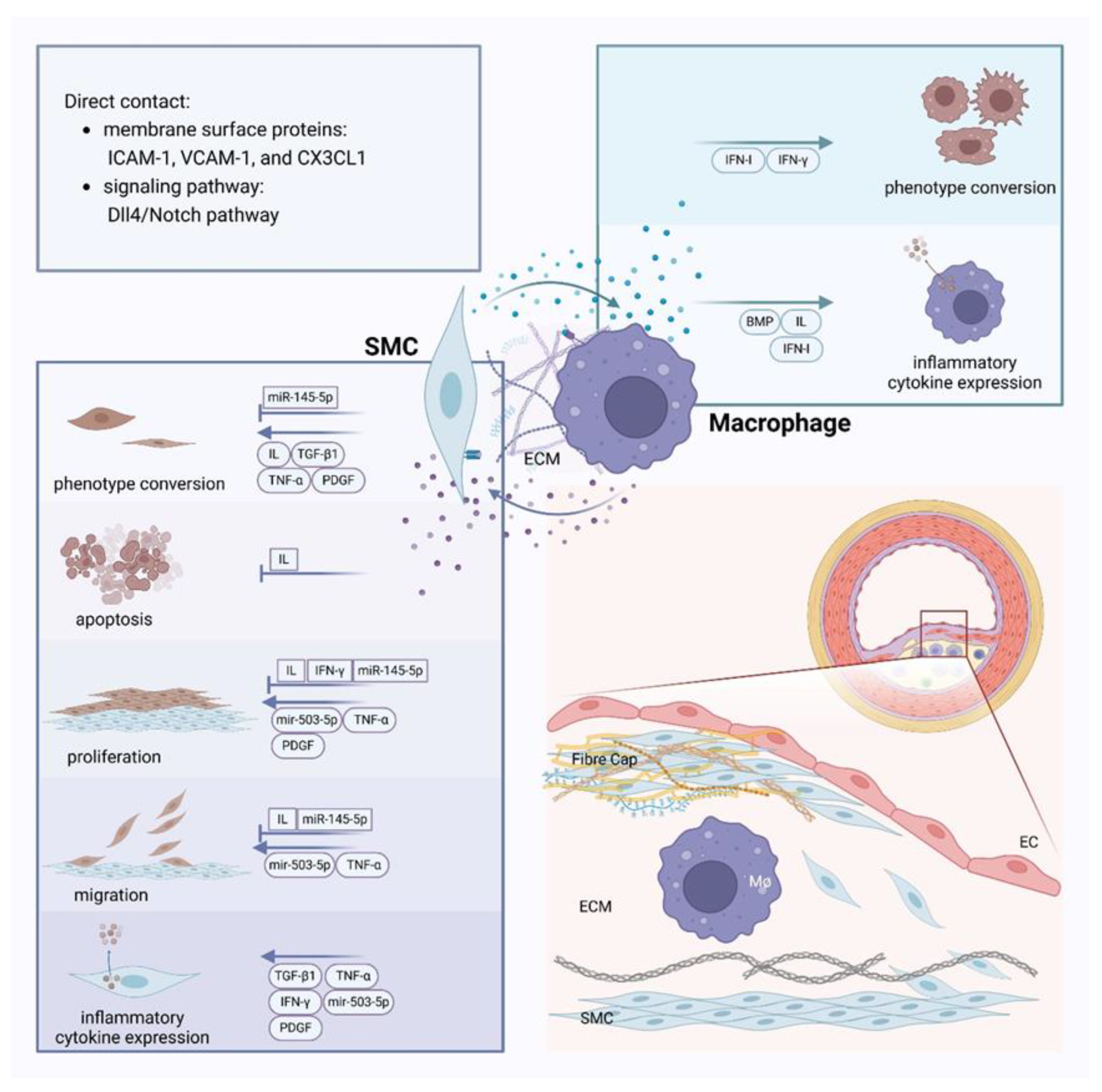

3.3. Crosstalk Between Smooth Muscle Cells and Macrophages

3.3.1. Direct Contact

3.3.2. Paracrine Secretion

Vasoactive Substance

Extracellular Vesicle

3.3.3. Extracellular Matrix

4. Discussion and Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Depuydt, M.A.; Prange, K.H.; Slenders, L.; Örd, T.; Elbersen, D.; Boltjes, A.; de Jager, S.C.; Asselbergs, F.W.; de Borst, G.J.; Aavik, E.; et al. Microanatomy of the Human Atherosclerotic Plaque by Single-Cell Transcriptomics. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 1437–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Ilyas, I.; Little, P.J.; Li, H.; Kamato, D.; Zheng, X.; Luo, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Han, J.; et al. Endothelial Dysfunction in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases and Beyond: From Mechanism to Pharmacotherapies. Pharmacol. Rev. 2021, 73, 924–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Lyu, Q.R.; Ilyas, I.; Tian, X.-Y.; Weng, J. Vascular homeostasis in atherosclerosis: A holistic overview. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 976722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corliss, B.A.; Azimi, M.S.; Munson, J.M.; Peirce, S.M.; Murfee, W.L. Macrophages: An Inflammatory Link Between Angiogenesis and Lymphangiogenesis. Microcirculation 2015, 23, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.P.; Hunziker, P. Atherosclerosis: Insights into Vascular Pathobiology and Outlook to Novel Treatments. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2020, 13, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinnouchi, H.; Guo, L.; Sakamoto, A.; Torii, S.; Sato, Y.; Cornelissen, A.; Kuntz, S.; Paek, K.H.; Fernandez, R.; Fuller, D.; et al. Diversity of macrophage phenotypes and responses in atherosclerosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 77, 1919–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushenkova, N.V.; Nikiforov, N.G.; Melnichenko, A.A.; Kalmykov, V.; Shakhpazyan, N.K.; Orekhova, V.A.; Orekhov, A.N. Functional Phenotypes of Intraplaque Macrophages and Their Distinct Roles in Atherosclerosis Development and Atheroinflammation. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogoda, K.; Kameritsch, P. Molecular regulation of myoendothelial gap junctions. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2019, 45, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, B.R.; Mulhaupt, F.; Veillard, N.; Gros, D.B.; Mach, F. Altered Pattern of Vascular Connexin Expression in Atherosclerotic Plaques. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002, 22, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Fu, Y.; Yan, H.; Wang, X.; Li, T.; Peng, W.; Luo, D. Rutaecarpine prevented ox-LDL-induced VSMCs dysfunction through inhibiting overexpression of connexin 43. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 853, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; He, W.; Yang, R.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Si, J.; Li, X.; Ma, K. Inhibition of Connexin 43 reverses ox-LDL-mediated inhibition of autophagy in VSMC by inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allagnat, F.; Dubuis, C.; Lambelet, M.; Le Gal, L.; Alonso, F.; Corpataux, J.-M.; Déglise, S.; Haefliger, J.-A. Connexin37 reduces smooth muscle cell proliferation and intimal hyperplasia in a mouse model of carotid artery ligation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, C.A.; Lampe, P.D. Injury-triggered Akt phosphorylation of Cx43: a ZO-1-driven molecular switch that regulates gap junction size. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 127, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedovy, M.W.; Leng, X.; Leaf, M.R.; Iqbal, F.; Payne, L.B.; Chappell, J.C.; Johnstone, S.R. Connexin 43 across the Vasculature: Gap Junctions and Beyond. J. Vasc. Res. 2022, 60, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; A Cotgreave, I. Differential regulation of gap junctions by proinflammatory mediators in vitro. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 2312–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mui, K. L.; Chen, C. S.; Assoian, R. K. , The mechanical regulation of integrin-cadherin crosstalk organizes cells, signaling and forces. J Cell Sci 2016, 129, (6), 1093–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson-Beadling, S.K.; Fisher, C. A potential role for N-cadherin in mediating endothelial cell-smooth muscle cell interactions in the rat vasculature. .Lab Invest 1993, 69, 203–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, C.A.; Koutsouki, E.; Aguilera, C.M.; Blaschuk, O.W.; George, S.J. Inhibition of N-cadherin retards smooth muscle cell migration and intimal thickening via induction of apoptosis. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 52, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, C.A.; Wadey, K.S.; George, S.J. Soluble N-cadherin: A novel inhibitor of VSMC proliferation and intimal thickening. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2016, 78, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.F.; Nelson, C.M.; Tan, J.L.; Chen, C.S. Cadherins, RhoA, and Rac1 Are Differentially Required for Stretch-Mediated Proliferation in Endothelial Versus Smooth Muscle Cells. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, e44–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Janssens, S.P.; Wingler, K.; Schmidt, H.H.H.W.; Moens, A.L. Modulating endothelial nitric oxide synthase: a new cardiovascular therapeutic strategy. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2011, 301, H634–H646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhoutte, P.M.; Shimokawa, H.; Feletou, M.; Tang, E.H.C. Endothelial dysfunction and vascular disease - a 30th anniversary update. Acta Physiol. 2017, 219, 22–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.-F.; Liang, X.-Y.; Liu, W.; Lv, S.; He, S.-J.; Kuang, H.-B.; Yang, S.-L. Roles of eNOS in atherosclerosis treatment. Inflamm. Res. 2019, 68, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, R.M.J.; Ferrige, A.G.; Moncada, S. Nitric oxide release accounts for the biological activity of endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nature 1987, 327, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Meinberg, E.G.; Stanley, J.C.; Gordon, D.; Webb, R.C. Nitric Oxide Reversibly Inhibits the Migration of Cultured Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Circ. Res. 1996, 78, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhu, P.; Xu, S.-F.; Li, Y.-Q.; Deng, J.; Yang, D.-L. Ginsenoside Re inhibits PDGF-BB-induced VSMC proliferation via the eNOS/NO/cGMP pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 115, 108934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Lv, J.; Zeng, H. sGC agonist BAY1021189 promotes thoracic aortic dissection formation by accelerating vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype switch. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 952, 175789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stencel, M. G.; VerMeer, M.; Giles, J.; Tran, Q. K. , Endothelial regulation of calmodulin expression and eNOS-calmodulin interaction in vascular smooth muscle. Mol Cell Biochem 2022, 477, (5), 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulides, N.; Durante, W.; Kroll, M.H.; Schafer, A.I. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Heme Oxygenases Generate Guanylyl Cyclase–Stimulatory Carbon Monoxide. Circulation 1995, 91, 2306–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, H.S.; Yan, L.M.; Fu, M.G.; Wang, X.H.; Pang, Y.Z.; Su, J.Y.; Tang, C.S. [The role of endogenous CO in the regulation of endothelin-induced VSMC proliferation and MAPK activity]. .Sheng Li Xue Bao 1999, 51, 315–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. P.; Wang, X.; Nakao, A.; Kim, S. I.; Murase, N.; Choi, M. E.; Ryter, S. W.; Choi, A. M. , Caveolin-1 expression by means of p38beta mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates the antiproliferative effect of carbon monoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 11319–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Tulis, D.; Keswani, A.N.; Peyton, K.J.; Wang, H.; I Schafer, A.; Durante, W. Local administration of carbon monoxide inhibits neointima formation in balloon injured rat carotid arteries. .Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2005, 51, 441–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, A.I.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Kelley, E.E.; Pagano, P.J.; Zuckerbraun, B.S.; Bauer, P.M. HO-1 and CO Decrease Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-Induced Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Migration Via Inhibition of Nox1. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, T.; Kourembanas, S. Endothelial cell expression of vasoconstrictors and growth factors is regulated by smooth muscle cell-derived carbon monoxide. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 96, 2676–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. H.; Lee, D. K.; Park, W.; Park, M.; Kim, S.; Hwang, J. Y.; Won, M. H.; Choi, Y. K.; Ryoo, S.; Ha, K. S.; Kwon, Y. G.; Kim, Y. M. , Carbon monoxide prevents TNF-α-induced eNOS downregulation by inhibiting NF-κB-responsive miR-155-5p biogenesis. Exp Mol Med 2017, 49, (11), e403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.-Y.; Liou, J.-Y.; Wu, K.K. Prostacyclin protects vascular integrity via PPAR/14-3-3 pathway. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2015, 118-119, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narumiya, S.; Sugimoto, Y.; Ushikubi, F. Prostanoid Receptors: Structures, Properties, and Functions. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 1193–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Chu, L.-Y.; Yang, S.-F.; Chen, H.-L.; Yet, S.-F.; Wu, K.K. Prostacyclin and PPARα Agonists Control Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Apoptosis and Phenotypic Switch through Distinct 14-3-3 Isoforms. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e69702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M. C.; Chen, L.; Zhou, J.; Tang, Z.; Hsu, T. F.; Wang, Y.; Shih, Y. T.; Peng, H. H.; Wang, N.; Guan, Y.; Chien, S.; Chiu, J. J. , Shear stress induces synthetic-to-contractile phenotypic modulation in smooth muscle cells via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/delta activations by prostacyclin released by sheared endothelial cells. Circ Res 2009, 105, 471–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, Y.; Lawson, J.; Funk, C. D.; Fitzgerald, G. A. , Cyclooxygenases, microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1, and cardiovascular function. J Clin Invest 2006, 116, 1391–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawa, H.; Flavahan, N.A.; Lorenz, R.R.; Vanhoutte, P.M. Prostacyclin releases endothelium-derived relaxing factor and potentiates its action in coronary arteries of the pig. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988, 95, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flammer, A.J.; Lüscher, T.F. Human endothelial dysfunction: EDRFs. Pfl?gers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2010, 459, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taddei, S.; Ghiadoni, L.; Virdis, A.; Buralli, S.; Salvetti, A. Vasodilation to Bradykinin Is Mediated by an Ouabain-Sensitive Pathway as a Compensatory Mechanism for Impaired Nitric Oxide Availability in Essential Hypertensive Patients. Circulation 1999, 100, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csányi, G.; Gajda, M.; Franczyk-Zarow, M.; Kostogrys, R.; Gwoźdź, P.; Mateuszuk, L.; Sternak, M.; Wojcik, L.; Zalewska, T.; Walski, M.; Chlopicki, S. , Functional alterations in endothelial NO, PGI₂ and EDHF pathways in aorta in ApoE/LDLR-/- mice. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2012, 98, 107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, S.M.; Hilgers, R.H.P.; Das, K.C. Decreased EDHF-mediated relaxation is a major mechanism in endothelial dysfunction in resistance arteries in aged mice on prolonged high-fat sucrose diet. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkor, M.A.; Quyyumi, A.A. Endothelium-Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor and Vascular Function. Cardiol. Res. Pr. 2011, 2011, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mather, S.; Dora, K.A.; Sandow, S.L.; Winter, P.; Garland, C.J. Rapid Endothelial Cell–Selective Loading of Connexin 40 Antibody Blocks Endothelium-Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor Dilation in Rat Small Mesenteric Arteries. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montezano, A.C.; Cat, A.N.D.; Rios, F.J.; Touyz, R.M. Angiotensin II and Vascular Injury. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2014, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Paul, A.; Corbett, C. B.; Okune, R.; Autieri, M. V. , Angiotensin II, Hypercholesterolemia, and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells: A Perfect Trio for Vascular Pathology. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, (12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, H.; Suzuki, H.; Ohtsu, H.; Chao, J.Y.; Utsunomiya, H.; Frank, G.D.; Eguchi, S. Angiotensin II Regulates Vascular and Endothelial Dysfunction: Recent Topics of Angiotensin II Type-1 Receptor Signaling in the Vasculature. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2006, 4, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra, J.; Llorente-Cortés, V.; Costales, P.; Huesca-Gómez, C.; Badimon, L. Angiotensin II upregulates LDL receptor-related protein (LRP1) expression in the vascular wall: a new pro-atherogenic mechanism of hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 78, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Dandapat, A.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Hermonat, P.L.; Carey, R.M.; Mehta, J.L. Over-expression of angiotensin II type 2 receptor (agtr2) reduces atherogenesis and modulates LOX-1, endothelial nitric oxide synthase and heme-oxygenase-1 expression. Atherosclerosis 2008, 199, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Chen, M.-F.; Xiao, Z.-L.; Yu, G.-L.; Chen, X.-B.; Xie, X.-M. The Effect of Endothelial Progenitor Cells on Angiotensin II–induced Proliferation of Cultured Rat Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2011, 58, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Yanagisawa, M.; Kimura, S.; Kasuya, Y.; Miyauchi, T.; Goto, K.; Masaki, T. The human endothelin family: three structurally and pharmacologically distinct isopeptides predicted by three separate genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1989, 86, 2863–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neylon, C.B. VASCULAR BIOLOGY OF ENDOTHELIN SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1999, 26, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, M.A.; Dempsey, E.C.; Walchak, S.J.; Stelzner, T.J. BQ123, an ETA Receptor Antagonist, Inhibits Endothelin-1-mediated Proliferation of Human Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1993, 9, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khimji, A. K.; Rockey, D. C. , Endothelin--biology and disease. Cell Signal 2010, 22, 1615–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seif, F.; Little, P.J.; Niayesh-Mehr, R.; Zamanpour, M.; Babaahmadi-Rezaei, H. Endothelin-1 increases CHSY-1 expression in aortic endothelial cells via transactivation of transforming growth factor β type I receptor induced by type B receptor endothelin-1. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, L.; Li, H.; Eriksson, U. The PDGF family: four gene products form five dimeric isoforms. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004, 15, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, D.G.; Miller, K.G.; Lourenssen, S.R.; Blennerhassett, M.G. Inflammatory cytokines promote growth of intestinal smooth muscle cells by induced expression of PDGF-Rβ. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, Y.; Xie, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Kong, W.; Zhu, Y. Homocysteine activates vascular smooth muscle cells by DNA demethylation of platelet-derived growth factor in endothelial cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2012, 53, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondy, J.S.; Lindner, V.; Miyashiro, J.K.; Berk, B.C.; Dean, R.H.; Geary, R.L.; T, Z.; J, L.; X, C.; J, P.; et al. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Ligand and Receptor Expression in Response to Altered Blood Flow In Vivo. Circ. Res. 1997, 81, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, T.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Pi, J.; Kuang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tomlinson, B.; Chan, P.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; et al. Cell-Specific Effects of GATA (GATA Zinc Finger Transcription Factor Family)-6 in Vascular Smooth Muscle and Endothelial Cells on Vascular Injury Neointimal Formation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 888–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeCouter, J.; Ferrara, N. EG-VEGF and the concept of tissue-specific angiogenic growth factors. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2002, 13, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammela, T.; Enholm, B.; Alitalo, K.; Paavonen, K. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factors. Cardiovasc Res 2005, 65, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Nawaz, M.I. Molecular mechanism of VEGF and its role in pathological angiogenesis. J. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 123, 1938–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J.; Waltenberger, J. VEGF-A Induces Expression of eNOS and iNOS in Endothelial Cells via VEGF Receptor-2 (KDR). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 252, 743–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.J.; Park, J.S.; Kim, M.H.; Hong, M.H.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, S.M.; Shin, B.A.; Ahn, B.W.; Jung, Y.D. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases and AP-1 mediate the up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor by PDGF in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2006, 28, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Orekhov, A.N.; Bobryshev, Y.V. Extracellular vesicles and atherosclerotic disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 2697–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, I.K.H.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Armstrong, A.J.; Kinchen, J.M.; Juncadella, I.J.; Bayliss, D.A.; Ravichandran, K.S. Unexpected link between an antibiotic, pannexin channels and apoptosis. Nature 2014, 507, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabaei, S.; Tabaee, S.S. Implications for MicroRNA involvement in the prognosis and treatment of atherosclerosis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Bian, Z.; Sun, F.; Lu, J.; Yin, Y.; Cai, X.; et al. Secreted Monocytic miR-150 Enhances Targeted Endothelial Cell Migration. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hergenreider, E.; Heydt, S.; Tréguer, K.; Boettger, T.; Horrevoets, A.J.G.; Zeiher, A.M.; Scheffer, M.P.; Frangakis, A.S.; Yin, X.; Mayr, M.; et al. Atheroprotective communication between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells through miRNAs. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Yuan, S.; Li, S.; Li, L.; Liu, M.; Wan, S. The Exosome-Derived Biomarker in Atherosclerosis and Its Clinical Application. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2018, 12, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Y. S.; Nguyen, P.; Wang, K. C.; Weiss, A.; Kuo, Y. C.; Chiu, J. J.; Shyy, J. Y.; Chien, S. , Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell turnover by endothelial cell-secreted microRNA-126: role of shear stress. Circ Res 2013, 113, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Mil, A.; Grundmann, S.; Goumans, M.-J.; Lei, Z.; Oerlemans, M.I.; Jaksani, S.; Doevendans, P.A.; Sluijter, J.P. MicroRNA-214 inhibits angiogenesis by targeting Quaking and reducing angiogenic growth factor release. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 93, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Balkom, B.W.M.; de Jong, O.G.; Smits, M.; Brummelman, J.; Ouden, K.D.; de Bree, P.M.; van Eijndhoven, M.A.J.; Pegtel, D.M.; Stoorvogel, W.; Würdinger, T.; et al. Endothelial cells require miR-214 to secrete exosomes that suppress senescence and induce angiogenesis in human and mouse endothelial cells. Blood 2013, 121, 3997–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, K.R.; Sheehy, N.T.; White, M.P.; Berry, E.C.; Morton, S.U.; Muth, A.N.; Lee, T.-H.; Miano, J.M.; Ivey, K.N.; Srivastava, D. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature 2009, 460, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xie, Y.; Salvador, A.M.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, K.; Li, G.; Xiao, J. Exosomes: Multifaceted Messengers in Atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2020, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Yin, W. N.; Suzuki, T.; Zhang, X. H.; Zhang, Y.; Song, L. L.; Jin, L. S.; Zhan, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, J. S.; Wen, J. K. , Exosome-Mediated miR-155 Transfer from Smooth Muscle Cells to Endothelial Cells Induces Endothelial Injury and Promotes Atherosclerosis. Mol Ther 2017, 25, (6), 1279–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Yang, H.C.; Rhee, W.J.; Kang, H. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell-Derived Exosomal MicroRNAs Regulate Endothelial Cell Migration Under PDGF Stimulation. Cells 2020, 9, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez-Barbero, N.; Gutiérrez-Muñoz, C.; Blanco-Colio, L.M. Cellular Crosstalk between Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells in Vascular Wall Remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongiat, M.; Andreuzzi, E.; Tarticchio, G.; Paulitti, A. Extracellular Matrix, a Hard Player in Angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taipale, J.; Keski-Oja, J. , Growth factors in the extracellular matrix. Faseb j 1997, 11, 51–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G. E.; Senger, D. R. , Endothelial extracellular matrix: biosynthesis, remodeling, and functions during vascular morphogenesis and neovessel stabilization. Circ Res 2005, 97, 1093–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, P.; Valcarcel-Jimenez, L.; Frezza, C.; Dupont, S. Crosstalk between mechanotransduction and metabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjisavva, R.; Anastasiou, O.; Ioannou, P.S.; Zheltkova, M.; Skourides, P.A. Adherens junctions stimulate and spatially guide integrin activation and extracellular matrix deposition. Cell Rep. 2022, 40, 111091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.M.; Jeong, K.; Lim, S.-T.S. FAK Family Kinases in Vascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, P.; Bean, P.; Whitelock, J. Inhibition of endothelial cell adhesion and proliferation by extracellular matrix from vascular smooth muscle cells: role of type V collagen. Atherosclerosis 1998, 141, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.-H.; Huang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, S.-M.; Guan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Tian, S.; Deng, K.; et al. Mindin regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype and prevents neointima formation. Clin. Sci. 2015, 129, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnigoni, A.; Viola, M.; Karousou, E.; Rovera, S.; Giaroni, C.; Passi, A.; Vigetti, D. Hyaluronan in pathophysiology of vascular diseases: specific roles in smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2022, 323, C505–C519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Urabe, G.; Marcho, L.; Stratton, M.; Guo, L.-W.; Kent, C.K. ALDH1A3 Regulations of Matricellular Proteins Promote Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation. iScience 2019, 19, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Ha, H. C.; Yang, G.; Jang, J. M.; Park, B. K.; Fu, Z.; Shin, I. C.; Kim, D. K. , Hyaluronic acid and proteoglycan link protein 1 suppresses platelet derived growth factor-BB-induced proliferation, migration, and phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells. BMB Rep 2023, 56, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapir, L.; Tzlil, S. , Talking over the extracellular matrix: How do cells communicate mechanically? Semin Cell Dev Biol 2017, 71, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, Y.; Yanagisawa, H. The molecular mechanism of mechanotransduction in vascular homeostasis and disease. Clin. Sci. 2020, 134, 2399–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, Y.; Thang, B.Q.; Ramirez, K.; Shin, S.J.; Kohata, T.; Ohata, S.; Nguyen, T.A.V.; Ohtsuki, S.; Nagayama, K.; Yanagisawa, H. Matrix mechanotransduction mediated by thrombospondin-1/integrin/YAP in the vascular remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 9896–9905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, R.; Tjwa, M.; Vandervoort, P.; Van Kerckhoven, S.; Holvoet, P.; Hoylaerts, M. F. , Thrombospondin-1 deficiency accelerates atherosclerotic plaque maturation in ApoE-/- mice. Circ Res 2008, 103, 1181–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, P.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Feng, B. , Role of macrophages in angiogenesis. Chinese Journal of Immunology 2021, 37, 2710–2714. [Google Scholar]

- Jetten, N.; Verbruggen, S.; Gijbels, M.J.; Post, M.J.; De Winther, M.P.J.; Donners, M.M.P.C. Anti-inflammatory M2, but not pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages promote angiogenesis in vivo. Angiogenesis 2014, 17, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnasamy, K.; Limbourg, A.; Kapanadze, T.; Gamrekelashvili, J.; Beger, C.; Häger, C.; Lozanovski, V.J.; Falk, C.S.; Napp, L.C.; Bauersachs, J.; et al. Blood vessel control of macrophage maturation promotes arteriogenesis in ischemia. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Xu, J.; Warren, C.M.; Duan, D.; Li, X.; Wu, L.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L. Endothelial cells provide an instructive niche for the differentiation and functional polarization of M2-like macrophages. Blood 2012, 120, 3152–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammela, T.; Zarkada, G.; Nurmi, H.; Jakobsson, L.; Heinolainen, K.; Tvorogov, D.; Zheng, W.; Franco, C.A.; Murtomäki, A.; Aranda, E.; et al. VEGFR-3 controls tip to stalk conversion at vessel fusion sites by reinforcing Notch signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 1202–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantin, A.; Vieira, J.M.; Gestri, G.; Denti, L.; Schwarz, Q.; Prykhozhij, S.; Peri, F.; Wilson, S.W.; Ruhrberg, C. Tissue macrophages act as cellular chaperones for vascular anastomosis downstream of VEGF-mediated endothelial tip cell induction. Blood 2010, 116, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Akahori, H.; Harari, E.; Smith, S.L.; Polavarapu, R.; Karmali, V.; Otsuka, F.; Gannon, R.L.; Braumann, R.E.; Dickinson, M.H.; et al. CD163+ macrophages promote angiogenesis and vascular permeability accompanied by inflammation in atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 1106–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; He, Y.; Dai, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Ruan, Q. Vascular endothelial growth factor modified macrophages transdifferentiate into endothelial-like cells and decrease foam cell formation. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Zhang, D.; Lu, L.; Qiu, H.; Wang, J. Vascular endothelial growth factor-modified macrophages accelerate reendothelialization and attenuate neointima formation after arterial injury in atherosclerosis-prone mice. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 10652–10661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Muri, J.; Fitzgerald, G.; Gorski, T.; Gianni-Barrera, R.; Masschelein, E.; D’hulst, G.; Gilardoni, P.; Turiel, G.; Fan, Z.; et al. Endothelial Lactate Controls Muscle Regeneration from Ischemia by Inducing M2-like Macrophage Polarization. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 1136–1153.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalan-Dibene, J.; McIntyre, L. L.; Zlotnik, A. , Interleukin 30 to Interleukin 40. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2018, 38, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, A.; Matsushima, K.; Vandamme, J.; Wang, J.; Polentarutti, N.; Dejana, E.; Colotta, F.; Mantovani, A. IL-1 TRANSCRIPTIONALLY ACTIVATES THE NEUTROPHIL CHEMOTACTIC FACTOR IL-8 GENE IN ENDOTHELIAL-CELLS. 1990, 69, 548–553.

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, W.; Xing, D.; Li, P.; Fu, J.; Gong, K.; Hage, F.G.; Oparil, S.; Chen, Y.-F.; Giordano, S.; et al. Endothelial cells overexpressing IL-8 receptor reduce cardiac remodeling and dysfunction following myocardial infarction. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2013, 305, H590–H598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, W.; Liao, Y. Targeting IL-1β in the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Pober, J.; Wheeler, M.; Cotran, R.; Gimbrone, M. INTERLEUKIN-1 ACTIVATION OF VASCULAR ENDOTHELIUM - EFFECTS ON PROCOAGULANT ACTIVITY AND LEUKOCYTE ADHESION. 1985, 121, 394–403.

- Yang, Y.; Luo, N.-S.; Ying, R.; Xie, Y.; Chen, J.-Y.; Wang, X.-Q.; Gu, Z.-J.; Mai, J.-T.; Liu, W.-H.; Wu, M.-X.; et al. Macrophage-derived foam cells impair endothelial barrier function by inducing endothelial-mesenchymal transition via CCL-4. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-Y.; Qin, L.; Li, G.; Wang, Z.; Dahlman, J.E.; Malagon-Lopez, J.; Gujja, S.; Cilfone, N.A.; Kauffman, K.J.; Sun, L.; et al. Endothelial TGF-β signalling drives vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 912–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, G.; You, B.; Chen, S.-P.; Liao, J.K.; Sun, J. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Downregulates Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase mRNA Stability via Translation Elongation Factor 1-α 1. Circ. Res. 2008, 103, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyers, C. M.; Miller, F. J. , Endothelial dysfunction in chronic inflammatory diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2014, 15, 11324–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinbongard, P.; Heusch, G.; Schulz, R. TNFα in atherosclerosis, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion and heart failure. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 127, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, J.; Okigaki, M.; Takahashi, T.; Katsume, A.; Adachi, Y.; Yamaguchi, S.; Matsunaga, S.; Takeda, M.; Matsui, A.; Kishita, E.; et al. Endothelial FGF receptor signaling accelerates atherosclerosis. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2011, 300, H154–H161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parma, L.; Peters, H.A.B.; Sluiter, T.J.; Simons, K.H.; Lazzari, P.; de Vries, M.R.; Quax, P.H.A. bFGF blockade reduces intraplaque angiogenesis and macrophage infiltration in atherosclerotic vein graft lesions in ApoE3*Leiden mice. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Nie, W.; Pu, X.; Xu, X.; Zhu, J. Exosomes derived from oxidized LDL-stimulated macrophages attenuate the growth and tube formation of endothelial cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 4605–4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, R.; Zhao, H. Effect of microRNA-144-5p on the proliferation, invasion and migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells by targeting SMAD1. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 19, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D. Up-regulation of MiR-145-5p promotes the growth and migration in LPS-treated HUVECs through inducing macrophage polarization to M2. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. 2020, 41, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, N.; Wang, Y.; Dakhlallah, D.; Moldovan, L.; Agarwal, K.; Batte, K.; Shah, P.; Wisler, J.; Eubank, T.D.; Tridandapani, S.; et al. Macrophage microvesicles induce macrophage differentiation and miR-223 transfer. Blood 2013, 121, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zheng, J.; Peng, L.; Zhou, Y.; Song, Y.; Lu, Z. Extracellular-vesicle containing miRNA-503-5p released by macrophages contributes to atherosclerosis. Aging 2021, 13, 12239–12257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Zhao, M.; Du, F.; Li, K.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Su, G. , Macrophage-derived exosomal miR-4532 promotes endothelial cells injury by targeting SP1 and NF-κB P65 signalling activation. J Cell Mol Med 2022, 26, (20), 5165–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Luo, H.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; Zhu, X.; Ke, S.; Liu, H.; Lu, Z.; Chen, M. Regulation of capillary tubules and lipid formation in vascular endothelial cells and macrophages via extracellular vesicle-mediated microRNA-4306 transfer. J. Int. Med Res. 2018, 47, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njock, M.-S.; Cheng, H.S.; Dang, L.T.; Nazari-Jahantigh, M.; Lau, A.C.; Boudreau, E.; Roufaiel, M.; Cybulsky, M.I.; Schober, A.; Fish, J.E. Endothelial cells suppress monocyte activation through secretion of extracellular vesicles containing antiinflammatory microRNAs. Blood 2015, 125, 3202–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, C.; Xiao, J.; Li, D.; Sun, Z.; Li, M. Endothelial extracellular vesicles modulate the macrophage phenotype: Potential implications in atherosclerosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 2018, 87, e12648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagase, H.; Visse, R.; Murphy, G. Structure and function of matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 69, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, K.; Kagota, S.; McGuire, J.J.; Wakuda, H.; Yoshikawa, N.; Nakamura, K.; Shinozuka, K. Enhanced Nitric Oxide Synthase Activation via Protease-Activated Receptor 2 Is Involved in the Preserved Vasodilation in Aortas from Metabolic Syndrome Rats. J. Vasc. Res. 2015, 52, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.Y.; Birkland, T.P.; Howe, J.D.; Rowan, A.D.; Fidock, M.; Parks, W.C.; Gavrilovic, J. Macrophage Migration and Invasion Is Regulated by MMP10 Expression. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e63555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. Y.; Chan, C. K.; Braun, K. R.; Green, P. S.; O'Brien, K. D.; Chait, A.; Day, A. J.; Wight, T. N. , Monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation: synthesis and secretion of a complex extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 14122–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck-Joseph, J.; Lehoux, S. Molecular Interactions Between Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells and Macrophages in Atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, R.; Rashed, L.; Abdelkader, R.; Hashem, K. Stem cell therapy targets the neointimal smooth muscle cells in experimentally induced atherosclerosis: involvement of intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM) and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM). Braz. J. Med Biol. Res. 2021, 54, e10807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butoi, E. D.; Gan, A. M.; Manduteanu, I.; Stan, D.; Calin, M.; Pirvulescu, M.; Koenen, R. R.; Weber, C.; Simionescu, M. , Cross talk between smooth muscle cells and monocytes/activated monocytes via CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis augments expression of pro-atherogenic molecules. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1813, 2026–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Pan, S.; Zhu, L.; Cui, Q.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, F. Advanced Glycation End Products Induce Atherosclerosis via RAGE/TLR4 Signaling Mediated-M1 Macrophage Polarization-Dependent Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotypic Conversion. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, J. J.; Bowyer, D. E.; Weissberg, P. L.; Bennett, M. R. , Human blood-derived macrophages induce apoptosis in human plaque-derived vascular smooth muscle cells by Fas-ligand/Fas interactions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001, 21, 1402–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, J.J.; Weissberg, P.L.; Bennett, M.R. Human Macrophage-Induced Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Apoptosis Requires NO Enhancement of Fas/Fas-L Interactions. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002, 22, 1624–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Blanchard, V.; Francis, G. A. , Smooth Muscle Cell-Macrophage Interactions Leading to Foam Cell Formation in Atherosclerosis: Location, Location, Location. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 921597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Ren, Q.; Yu, A.; Ruan, Y. IL-5 overexpression attenuates aortic dissection by reducing inflammation and smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Life Sci. 2020, 241, 117144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazighi, M.; Pellé, A.; Gonzalez, W.; Mtairag el, M.; Philippe, M.; Hénin, D.; Michel, J. B.; Feldman, L. J. , IL-10 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell activation in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2004, 287, H866–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, W.; Chen, R.; Chen, J.; Touyz, R.M.; Wang, J.; Huang, H. Interleukin-18 Enhances Vascular Calcification and Osteogenic Differentiation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Through TRPM7 Activation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1933–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdis, M.; Burgler, S.; Crameri, R.; Eiwegger, T.; Fujita, H.; Gomez, E.; Klunker, S.; Meyer, N.; O'Mahony, L.; Palomares, O.; Rhyner, C.; Ouaked, N.; Schaffartzik, A.; Van De Veen, W.; Zeller, S.; Zimmermann, M.; Akdis, C. A. , Interleukins, from 1 to 37, and interferon-γ: receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011, 127, 701–21e1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.-W.; Corden, B.; Ng, B.; Vanezis, K.; D’agostino, G.; Widjaja, A.A.; Song, W.-H.; Xie, C.; Su, L.; Kwek, X.-Y.; et al. Interleukin-11 is important for vascular smooth muscle phenotypic switching and aortic inflammation, fibrosis and remodeling in mouse models. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurdagul, A. Crosstalk Between Macrophages and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Atherosclerotic Plaque Stability. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M. W.; Watanabe, M.; Lebedeva, M. A.; Depina, A. S.; Hanai, J.; Mammoto, T.; Frederick, J. P.; Wang, X. F.; Sukhatme, V. P.; Jain, M. K. , Transforming growth factor-beta1 inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell activation is mediated via Smad3. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 16388–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.Y.S.; Bub, G.L.; Campos, A.H. BMP-2 and -4 produced by vascular smooth muscle cells from atherosclerotic lesions induce monocyte chemotaxis through direct BMPRII activation. Atherosclerosis 2014, 235, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ding, Y.; Tao, W.; Zhang, W.; Liang, T.; Liu, C. Naringenin inhibits TNF-α induced VSMC proliferation and migration via induction of HO-1. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3025–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, S.M.; Chen, N.X. Pathophysiology of Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, F.S.; Choi, H.; Miller, M.R.; Stark, R.J. TNFα and Reactive Oxygen Signaling in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Hypertension and Atherosclerosis. Am. J. Hypertens. 2020, 33, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunokawa, Y.; Ishida, N.; Tanaka, S. Cloning of Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase in Rat Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993, 191, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, K.; Hertzog, P. J.; Ravasi, T.; Hume, D. A. , Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol 2004, 75, 163–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, Y.; Mohandas, R.; Lee, P.; Liu, Z.; Sautina, L.; Mu, W.; Li, S.; Wen, X.; Croker, B.; Segal, M.S.; et al. Effects of Long-Term Type I Interferon on the Arterial Wall and Smooth Muscle Progenitor Cells Differentiation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.-N.; Velichko, S.; Vincelette, J.; Fitch, R.M.; Vergona, R.; Sullivan, M.E.; Croze, E.; Wang, Y.-X. Interferon-beta attenuates angiotensin II-accelerated atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 2008, 197, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Medley, S.C.; Hu, T.; Hinsdale, M.E.; Lupu, F.; Virmani, R.; Olson, L.E. PDGFRβ signalling regulates local inflammation and synergizes with hypercholesterolaemia to promote atherosclerosis. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.A.C.; Serbulea, V.; Baylis, R.A.; Shankman, L.S.; Bradley, X.; Alencar, G.F.; Owsiany, K.; Deaton, R.A.; Karnewar, S.; Shamsuzzaman, S.; et al. Multiple cell types contribute to the atherosclerotic lesion fibrous cap by PDGFRβ and bioenergetic mechanisms. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Mao, D.; Li, C.; Li, M. miR-145-5p Inhibits Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (VSMCs) Proliferation and Migration by Dysregulating the Transforming Growth Factor-b Signaling Cascade. Med Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 4894–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaker, L.; Tebani, A.; Lesueur, C.; Dias, C.; Jung, V.; Bekri, S.; Guerrera, I.C.; Kamel, S.; Ausseil, J.; Boullier, A. Extracellular Vesicles From LPS-Treated Macrophages Aggravate Smooth Muscle Cell Calcification by Propagating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 823450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Lu, X.; Huang, J. MicroRNAs involved in the TGF-β signaling pathway in atherosclerosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 146, 112499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butoi, E.; Gan, A.; Tucureanu, M.; Stan, D.; Macarie, R.; Constantinescu, C.; Calin, M.; Simionescu, M.; Manduteanu, I. Cross-talk between macrophages and smooth muscle cells impairs collagen and metalloprotease synthesis and promotes angiogenesis. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2016, 1863, 1568–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galis, Z.S.; Sukhova, G.K.; Lark, M.W.; Libby, P. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases and matrix degrading activity in vulnerable regions of human atherosclerotic plaques. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 94, 2493–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Khalil, R. A. , Matrix Metalloproteinases, Vascular Remodeling, and Vascular Disease. Adv Pharmacol 2018, 81, 241–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, A.C.; Newby, A.C. Effect of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Knockout on Vein Graft Remodelling in Mice. J. Vasc. Res. 2009, 47, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jiang, J.; Chen, W.; Li, W.; Chen, Z. Vascular Macrophages in Atherosclerosis. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 4354786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Qian, M.; Kyler, K.; Xu, J. Endothelial–Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Interactions in Atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nambo-Venegas, R.; Palacios-González, B.; Mas-Oliva, J.; Aurioles-Amozurrutia, A.K.; Cruz-Rangel, A.; Moreno, A.; Hidalgo-Miranda, A.; Rodríguez-Dorantes, M.; Vadillo-Ortega, F.; Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; et al. Conversion of M1 Macrophages to Foam Cells: Transcriptome Differences Determined by Sex. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, R.A.; Kleemann, R.; Schaapherder, A.F.; Bogaerdt, A.v.D.; Hedin, U.; Matic, L.; Lindeman, J.H. Validating human and mouse tissues commonly used in atherosclerosis research with coronary and aortic reference tissue: similarities but profound differences in disease initiation and plaque stability. JVS: Vasc. Sci. 2023, 4, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Millican, R.; Lynd, T.; Gangasani, M.; Malhotra, S.; Sherwood, J.; Hwang, P.T.; Cho, Y.; Brott, B.C.; et al. Recent Progress in in vitro Models for Atherosclerosis Studies. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 8, 790529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navab, M.; Hough, G.P.; Stevenson, L.W.; Drinkwater, D.C.; Laks, H.; Fogelman, A.M. Monocyte migration into the subendothelial space of a coculture of adult human aortic endothelial and smooth muscle cells. J. Clin. Investig. 1988, 82, 1853–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaku, M.; Wada, Y.; Jinnouchi, K.; Takeya, M.; Takahashi, K.; Usuda, H.; Naito, M.; Kurihara, H.; Yazaki, Y.; Kumazawa, Y.; et al. An In Vitro Coculture Model of Transmigrant Monocytes and Foam Cell Formation. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999, 19, 2330–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noonan, J.; Grassia, G.; MacRitchie, N.; Garside, P.; Guzik, T.J.; Bradshaw, A.C.; Maffia, P. A Novel Triple-Cell Two-Dimensional Model to Study Immune-Vascular Interplay in Atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Samant, S.; Vasa, C.H.; Pedrigi, R.M.; Oguz, U.M.; Ryu, S.; Wei, T.; Anderson, D.R.; Agrawal, D.K.; Chatzizisis, Y.S. Co-culture models of endothelial cells, macrophages, and vascular smooth muscle cells for the study of the natural history of atherosclerosis. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0280385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Martin, R.; Wang, G.; Brandão, B.B.; Zanotto, T.M.; Shah, S.; Patel, S.K.; Schilling, B.; Kahn, C.R. MicroRNA sequence codes for small extracellular vesicle release and cellular retention. Nature 2021, 601, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).