1. Introduction

In recent years, the global market for indoor positioning and navigation systems has experienced substantial growth, propelled by the increasing demand for precise location services in environments where traditional GPS signals are inadequate [

1]. Industry reports indicate that the indoor positioning and navigation market was valued at over USD 8.3 billion in 2023, with projections to exceed USD 25 billion by 2030, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of more than 16% over the next decade [

2]. This surge underscores the critical reliance on indoor location services across various sectors, including retail, healthcare, and manufacturing. Given that 80% of the global population is expected to spend up to 90% of their time indoors [

3], the demand for robust and accurate navigation systems in complex indoor spaces is more pressing than ever.

Industries such as logistics and manufacturing are increasingly adopting indoor localization systems to enhance operational efficiency [

4], while the retail sector leverages these technologies to elevate customer experiences through targeted location-based services [

5]. Research indicates that implementing indoor navigation tools can boost productivity by up to 30% in warehouse management [

6] and reduce search times by as much as 25% in expansive facilities [

7]. However, despite these advantages, current indoor localization technologies encounter significant challenges related to accuracy, signal interference, and the ability to navigate dynamic environments filled with obstacles.

As our world becomes more interconnected, the demand for advanced navigation systems has surged, particularly in indoor settings where traditional Global Positioning System (GPS) signals fall short [

8]. The rapid expansion of wireless networks has facilitated innovative localization techniques, utilizing technologies such as Wireless Fidelity (Wi-Fi) and Bluetooth [

9]. These methods, based on trilateration and signal strength analysis, present viable solutions for tracking individuals and assets within intricate indoor environments. As urban landscapes grow increasingly complex, the necessity for effective navigation tools capable of functioning under these conditions becomes paramount.

Indoor localization systems find diverse applications, from enhancing user experiences in retail and hospitality environments to supporting autonomous robot movement in warehouses and factories [

10,

11]. These systems often rely on algorithms that utilize signal strength measurements for accurate positioning. The Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI) is particularly effective in this context, providing real-time data that reflects device proximity to access points (APs). By leveraging RSSI values, localization systems can estimate user positions and adapt dynamically to environmental changes, offering a flexible solution for indoor navigation.

Despite advancements in indoor positioning technologies, challenges persist [

12]. Signal interference, arising from physical barriers and environmental noise, can significantly undermine the accuracy of RSSI-based localization [

13]. Also, the presence of multiple obstacles complicates pathfinding, as traditional algorithms often struggle to navigate around barriers while maintaining optimal routes [

14]. Consequently, there is an urgent need for sophisticated algorithms that can merge localization data with efficient pathfinding strategies to ensure seamless navigation through complex indoor environments.

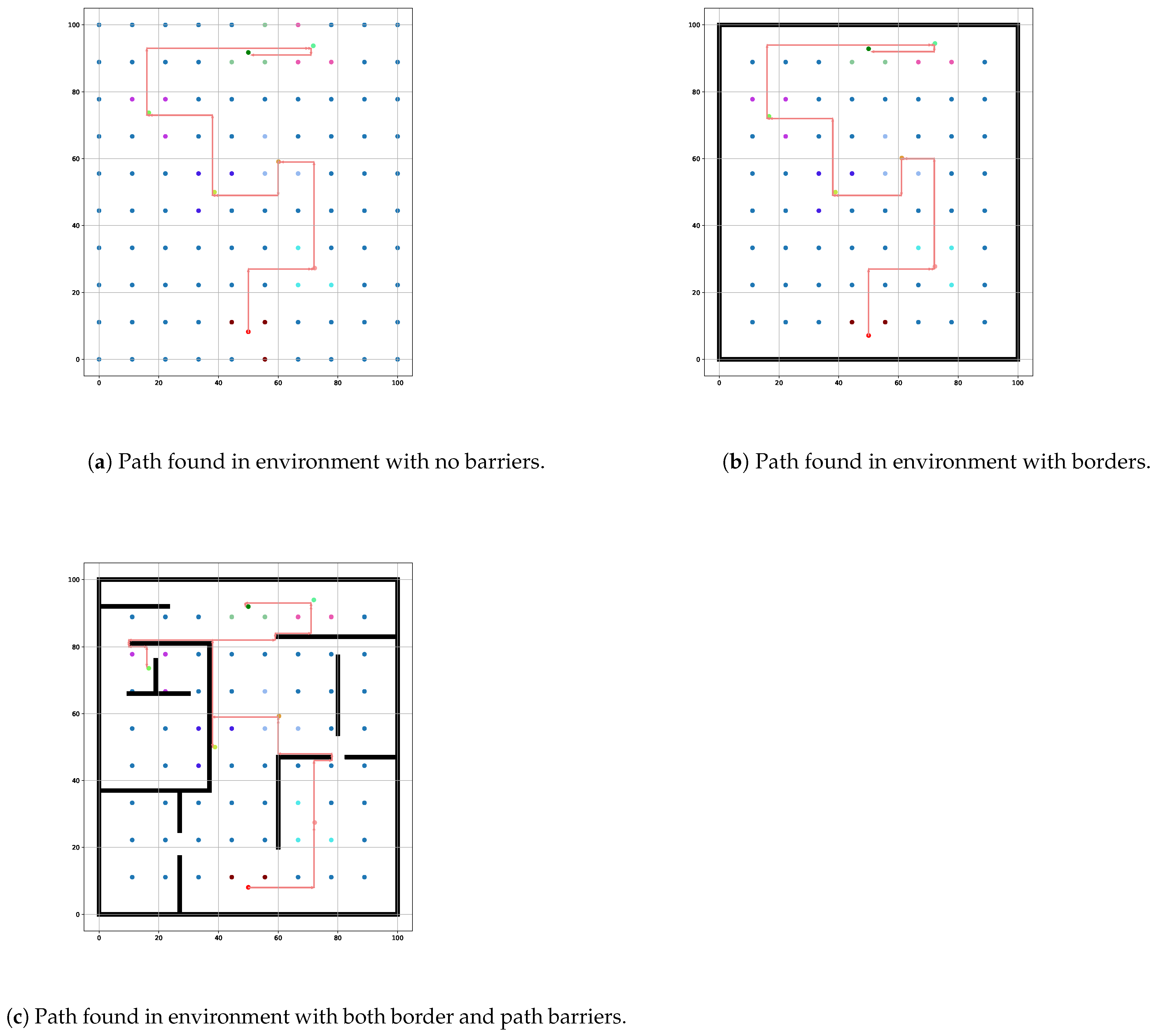

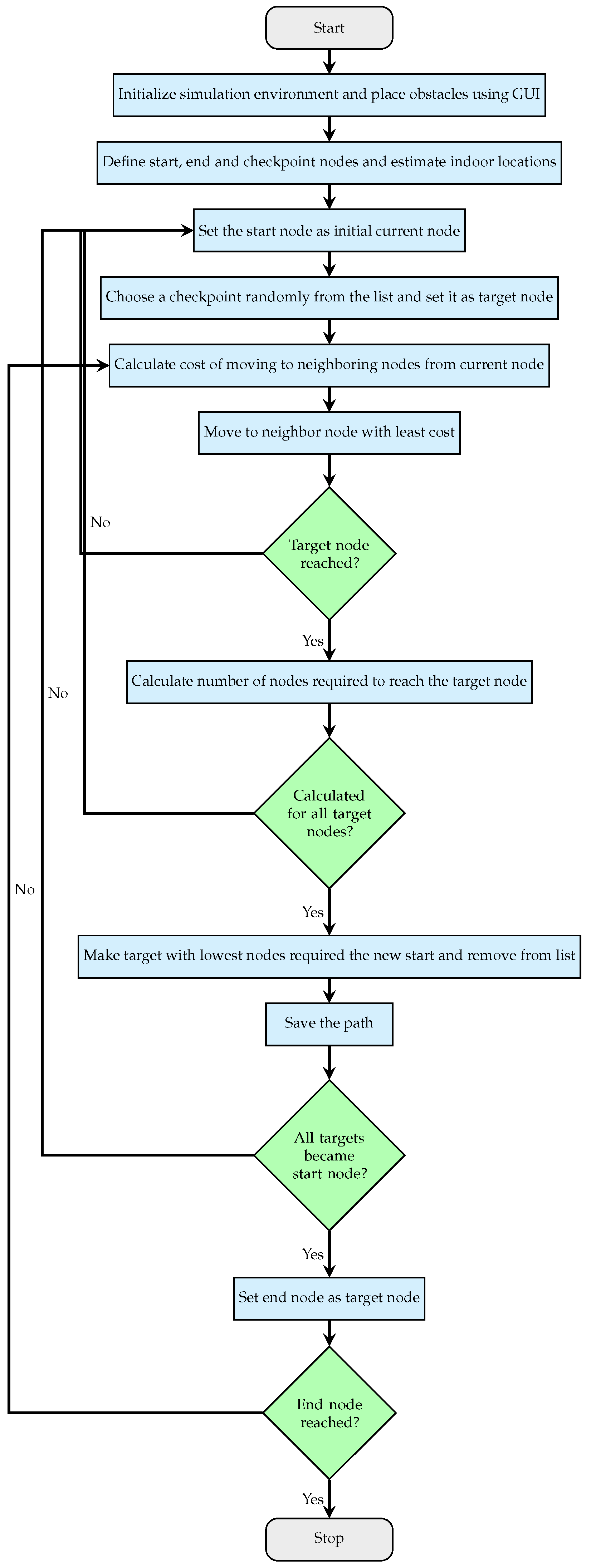

The algorithm proposed in this paper addresses these challenges by integrating advanced indoor mapping techniques with a refined pathfinding approach. Our algorithm features a user-friendly graphical user interface (GUI) that facilitates intuitive barrier placement, creating a scalable representation of the physical environment. This model empowers users to define start and end points and select multiple checkpoints along their desired routes. Using RSSI values, the system identifies the three closest APs and applies a trilateration algorithm to accurately determine the indoor location of the user. This synthesis of user-driven environment mapping and advanced localization techniques forms a robust framework for navigating through obstacles.

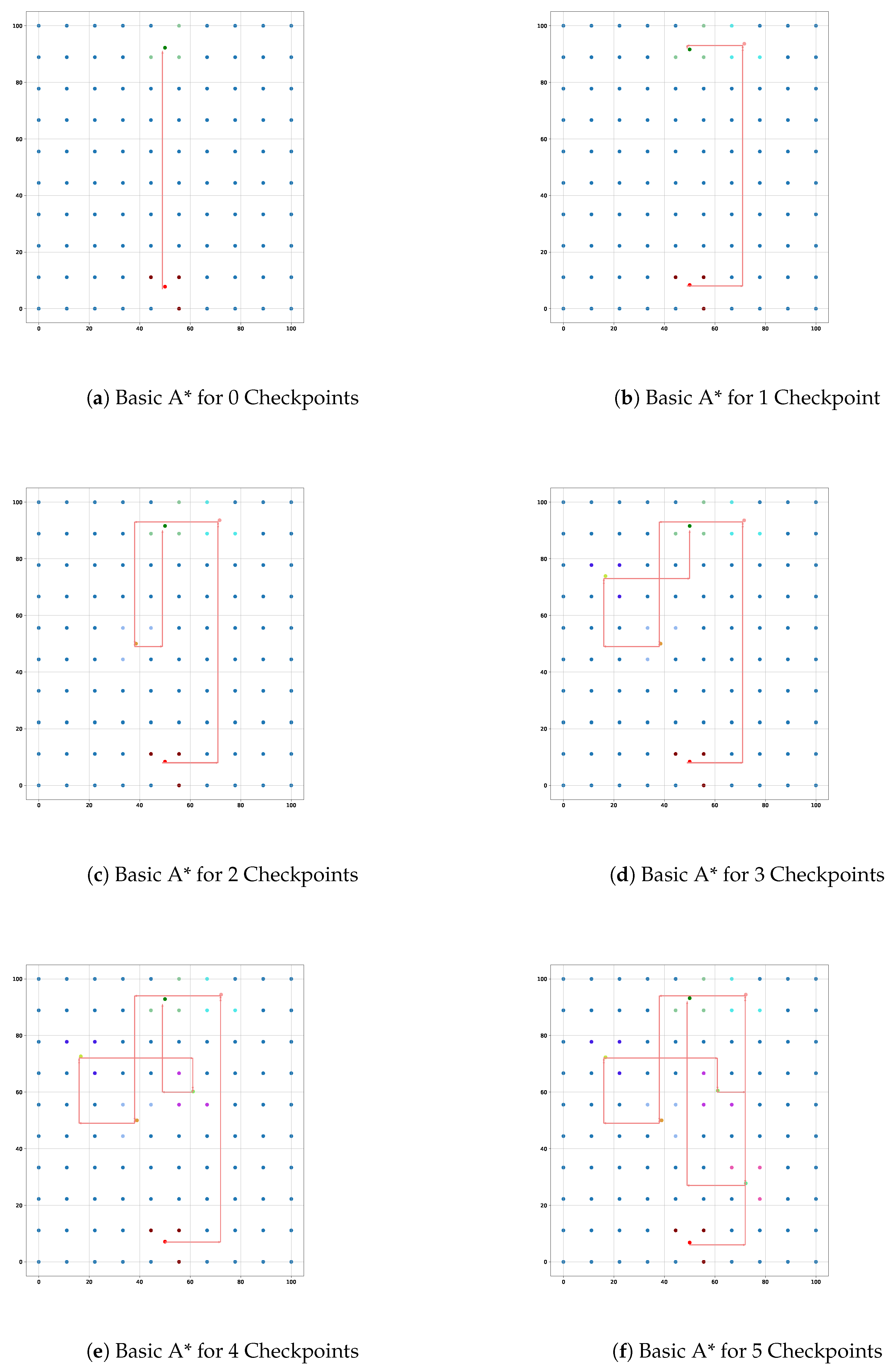

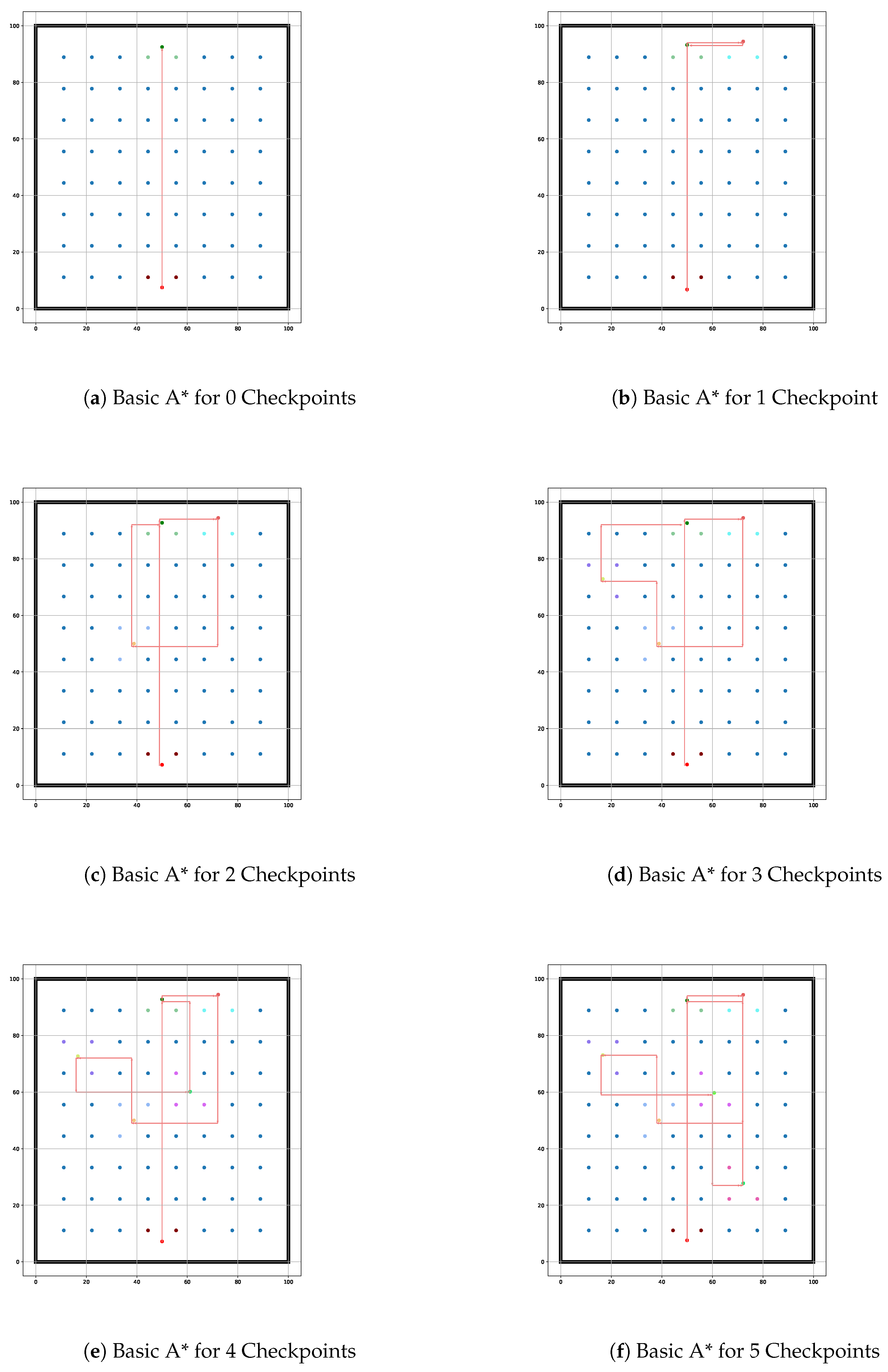

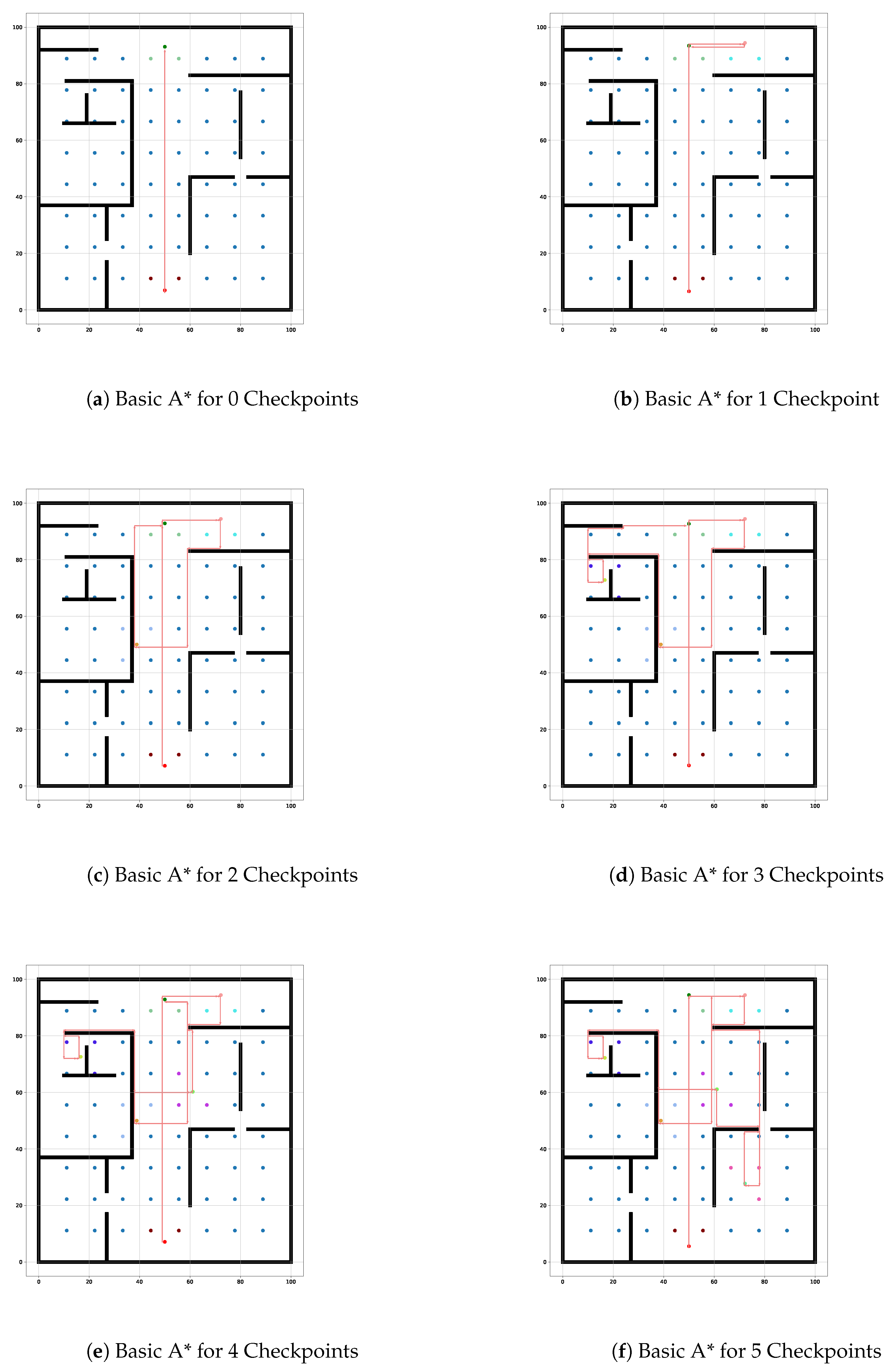

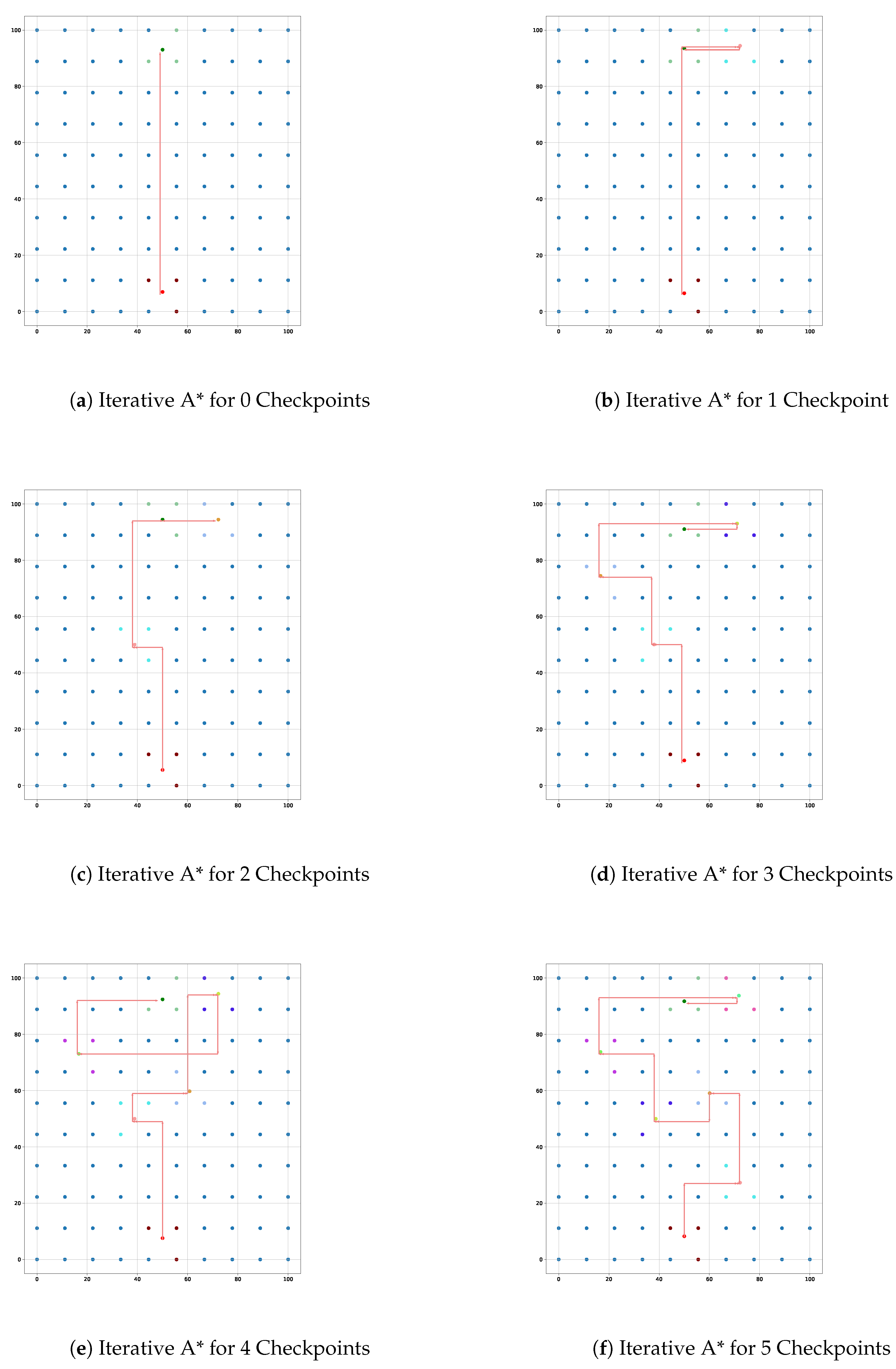

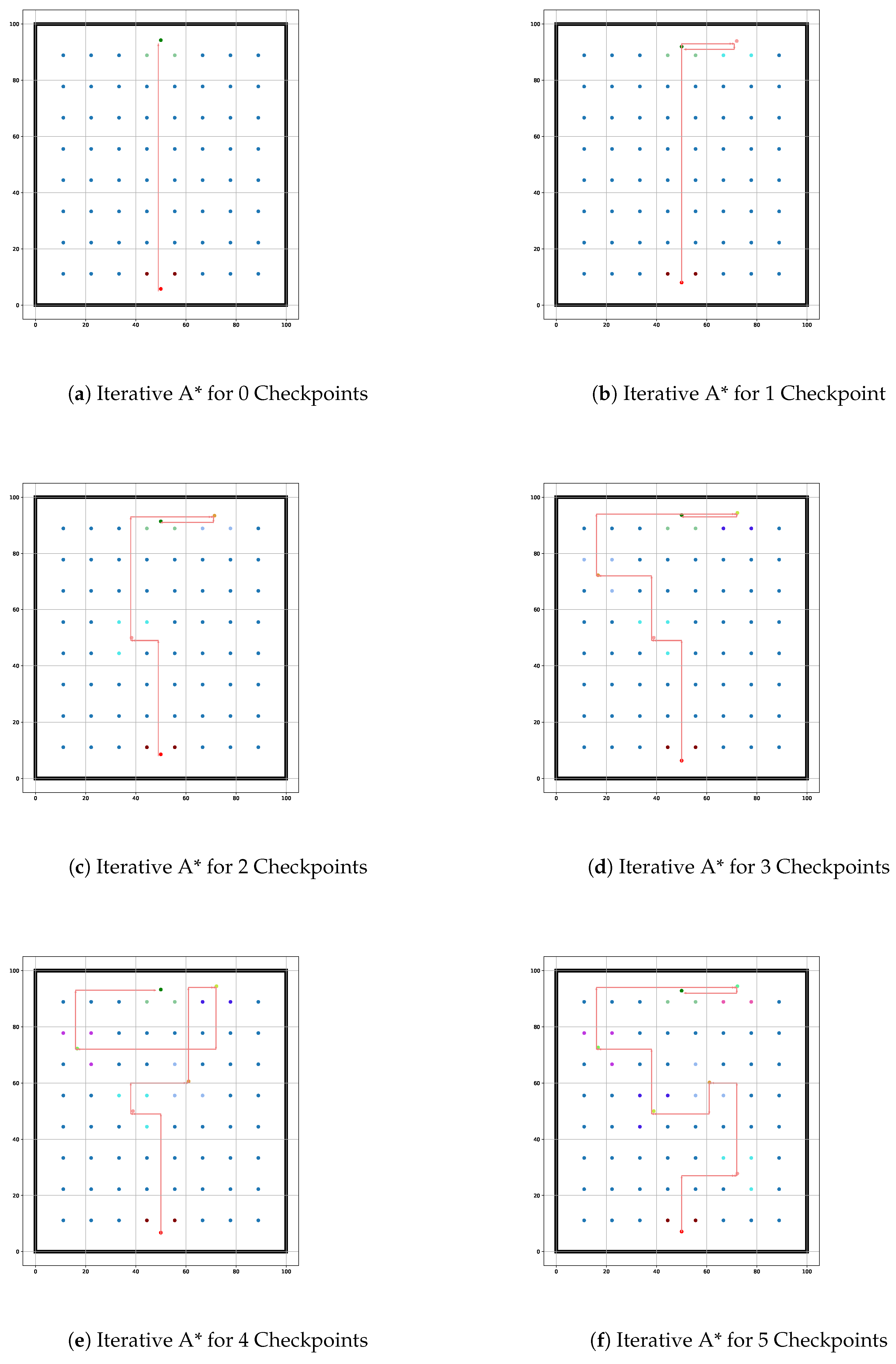

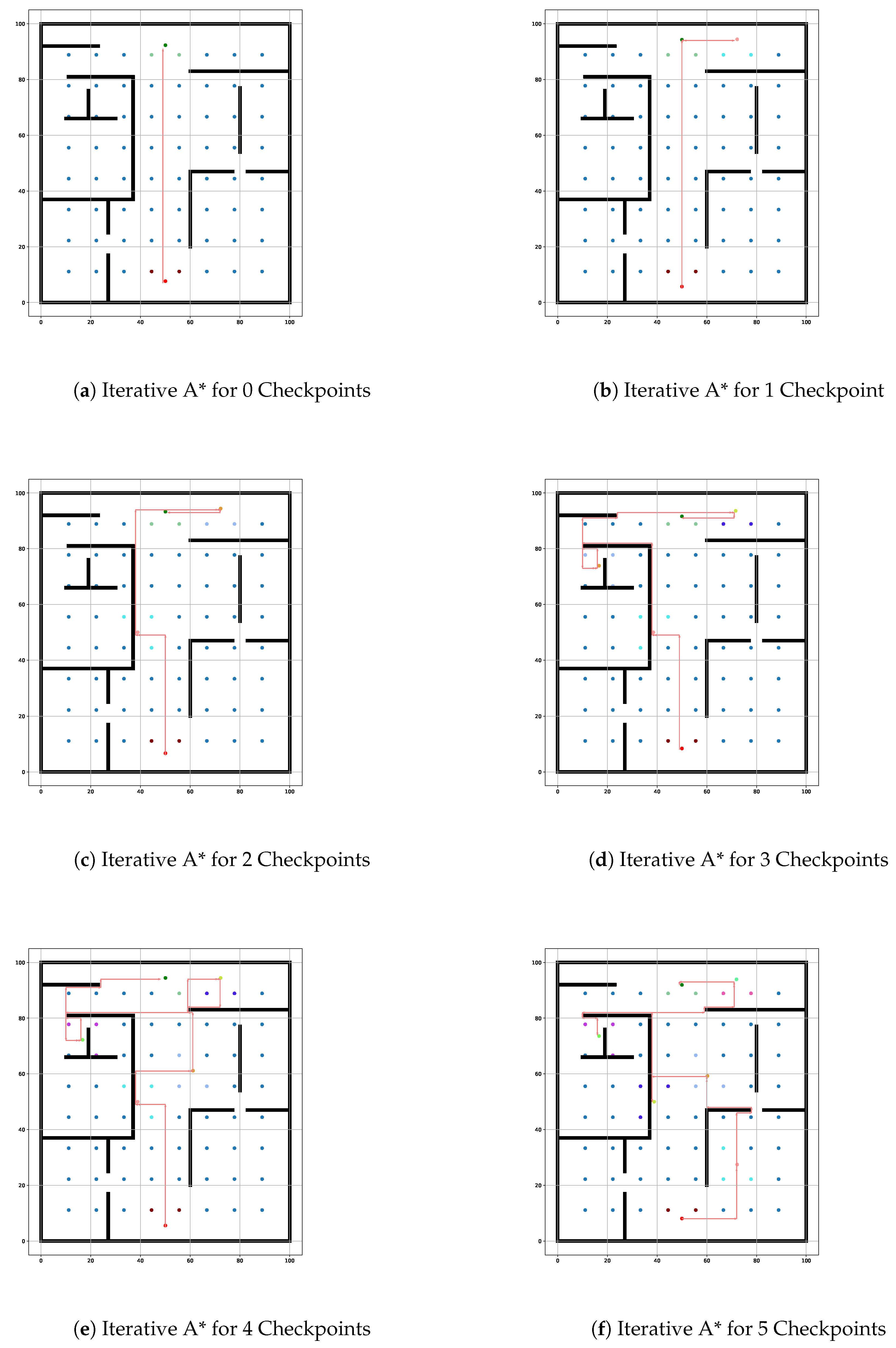

To optimize the pathfinding process, we implement an iterative A* algorithm that assesses potential routes based on a cost function derived from Manhattan distance calculations. This iterative approach ensures a balance between computational efficiency and the identification of the most optimal path. By dynamically rearranging checkpoints according to proximity, the algorithm enhances traversal efficiency within the indoor environment, enabling users to navigate effectively while accommodating the constraints of their surroundings.

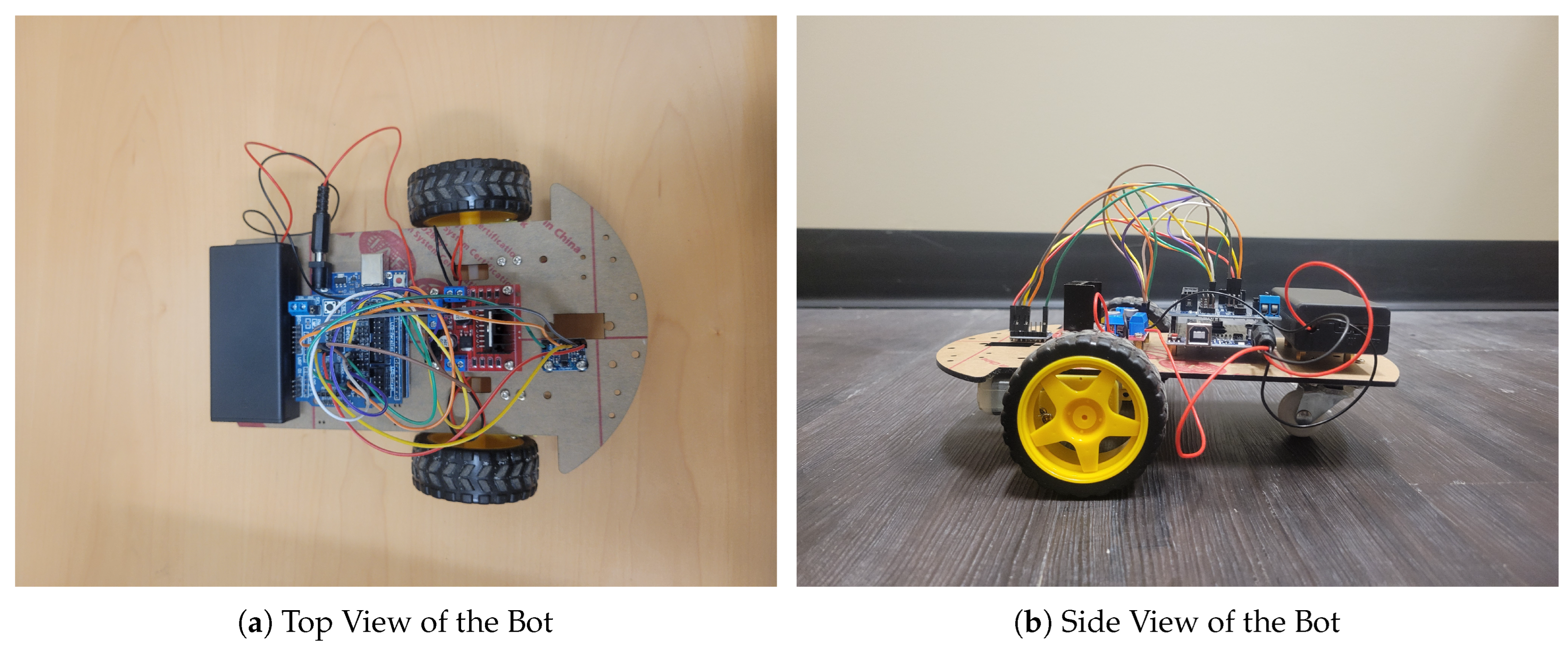

The proposed algorithm not only emphasizes pathfinding efficiency but also addresses the necessity of robust performance in real-world scenarios. To validate the simulation results, practical experiments were conducted using a two-wheeled bot, demonstrating the effectiveness of the optimized path generated by the algorithm. The data derived from the simulation was transferred to an Arduino microcontroller, allowing the bot to navigate through a scaled version of the simulated environment with remarkable accuracy. These experiments underscore the practical applicability of our proposed algorithm and highlight its potential to enhance navigation experiences across various indoor settings. The proposed algorithm’s main contributions are summarized as follows:

Provides a user-friendly GUI to simulate real-world spaces, allowing for barrier placement and indoor mapping before real-world application.

Accurately determines the user’s location using signal strengths from the three nearest APs without requiring additional hardware.

Utilizes existing infrastructure (APs) and trilateration techniques to reduce the need for additional resources, maintaining high efficiency and low operational costs.

Dynamically rearranges user-defined checkpoints to find the most computationally efficient path, balancing speed and accuracy.

Reduces unnecessary nodes in the path by eliminating redundant points, improving computational efficiency and runtime without sacrificing accuracy.

Translates optimized path data into real-world robot navigation, proving the algorithm’s applicability and effectiveness in practical indoor environments.

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces foundational concepts and essential background information for understanding the proposed algorithm’s development.

Section 3 offers a comprehensive review of related work, highlighting existing approaches, methodologies, and their limitations in indoor positioning and navigation. In

Section 4, we detail the proposed algorithm and its core features. Section 5 evaluates the algorithm through simulations and practical experiments. Section 6 discusses the proposed algorithm from various aspects, including its practical applications in real-world scenarios and acknowledging its limitations. Also, it outlines potential avenues for future research. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper by summarizing its key contributions.

2. Preliminary

To build an efficient and accurate indoor localization and pathfinding system, it is essential to understand the core principles that underlie these technologies. Indoor positioning systems, particularly those based on RSSI measurements, rely on the relationship between signal attenuation and distance to estimate user locations. However, the presence of obstacles and signal interference complicates this process, necessitating advanced techniques to enhance accuracy. Once localization is achieved, the A* algorithm is widely used for pathfinding, offering an effective solution for navigating complex indoor spaces. This section delves into the foundational concepts of RSSI-based localization, trilateration, signal interference, and adaptive pathfinding, highlighting the key challenges and strategies for optimizing performance in dynamic environments.

2.1. Indoor Localization using RSSI

Indoor localization systems frequently rely on the RSSI as a primary metric for estimating the distance between wireless devices [

15]. RSSI measures the strength of the signal transmitted from an AP to a receiver, with signal attenuation providing an approximate indication of distance. Given that signal strength diminishes in proportion to the square of the distance, RSSI data can be used to triangulate the receiver’s location. This process is typically conducted using trilateration, which calculates the user’s position based on distance estimates from three or more known AP locations.

However, indoor environments introduce a range of complexities that can affect the accuracy of RSSI measurements [

16]. Physical barriers, such as walls and furniture, as well as environmental factors like signal reflection and absorption, create noise in the signal, often leading to imprecise localization. To overcome these challenges, techniques such as filtering (e.g., Kalman filters) or machine learning models can be employed to smooth fluctuations in signal strength and improve location estimates. The design of the localization system must carefully consider the trade-off between increasing the density of APs to enhance accuracy and managing the complexity introduced by overlapping signals, which can lead to ambiguity in the trilateration process.

2.2. Trilateration and Signal Interference

Trilateration, as the primary method of location estimation in RSSI-based systems, depends on the accuracy of the distance data derived from signal strength [

17]. The success of trilateration is influenced by the spatial configuration of APs. Optimally placed APs provide distinct, non-overlapping coverage zones that improve the precision of location estimates. In contrast, suboptimal placement or dense networks can result in overlapping zones, causing interference and ambiguity in the user’s position.

Signal interference is further exacerbated by the nature of indoor environments, where signals are scattered, reflected, or absorbed by obstacles. Consequently, the effective signal range varies across different spaces, introducing inconsistencies in the RSSI readings. Advanced filtering techniques are often integrated to counteract this interference, ensuring smoother signal transitions and more accurate localization outcomes. Understanding and mitigating the effects of signal interference remains a critical challenge in the design of robust indoor positioning systems.

2.3. Pathfinding with the A* Algorithm

Once the user’s position has been accurately established, the next challenge is efficient navigation within the indoor environment. The A* algorithm is widely utilized for pathfinding due to its ability to balance exploration and efficiency [

18]. It operates by calculating a cost function for each possible route, combining both the known distance traveled from the starting point and a heuristic estimate of the remaining distance to the destination. The heuristic, often based on the Manhattan distance in grid-based environments, guides the algorithm towards the most promising paths while avoiding computationally expensive detours.

The strength of A* lies in its flexibility and adaptability. In scenarios where new obstacles emerge or dynamic changes occur within the environment, A* can dynamically update its search parameters to reflect the altered landscape. This is particularly useful in indoor environments, where users may encounter shifting obstacles such as movable furniture or temporary barriers. By continuously recalculating potential routes based on real-time information, A* ensures that the navigation system remains both efficient and reliable, even under changing conditions.

2.4. Integration of Localization and Pathfinding

The fusion of RSSI-based localization and A* pathfinding represents a comprehensive approach to indoor navigation. Once trilateration provides an accurate position estimate, the A* algorithm can generate the most efficient path while considering potential obstacles and environmental constraints. The iterative nature of A*, combined with real-time updates from the localization system, allows for dynamic rerouting as the user’s position or environment changes.

Moreover, user-driven factors—such as preferred routes or checkpoints—can be seamlessly integrated into the pathfinding process, allowing for more customized navigation experiences. For example, in scenarios where users must navigate through specific checkpoints or avoid certain areas, the system can adjust paths in real time, optimizing the route based on both user preferences and environmental factors. This interplay between localization and adaptive pathfinding forms the backbone of sophisticated indoor navigation systems, ensuring both precision and flexibility in complex indoor environments.

6. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the practical benefits and applications of the proposed algorithm, highlighting its organizational convenience, user-centric design, and resource efficiency.

6.1. Organizational Convenience

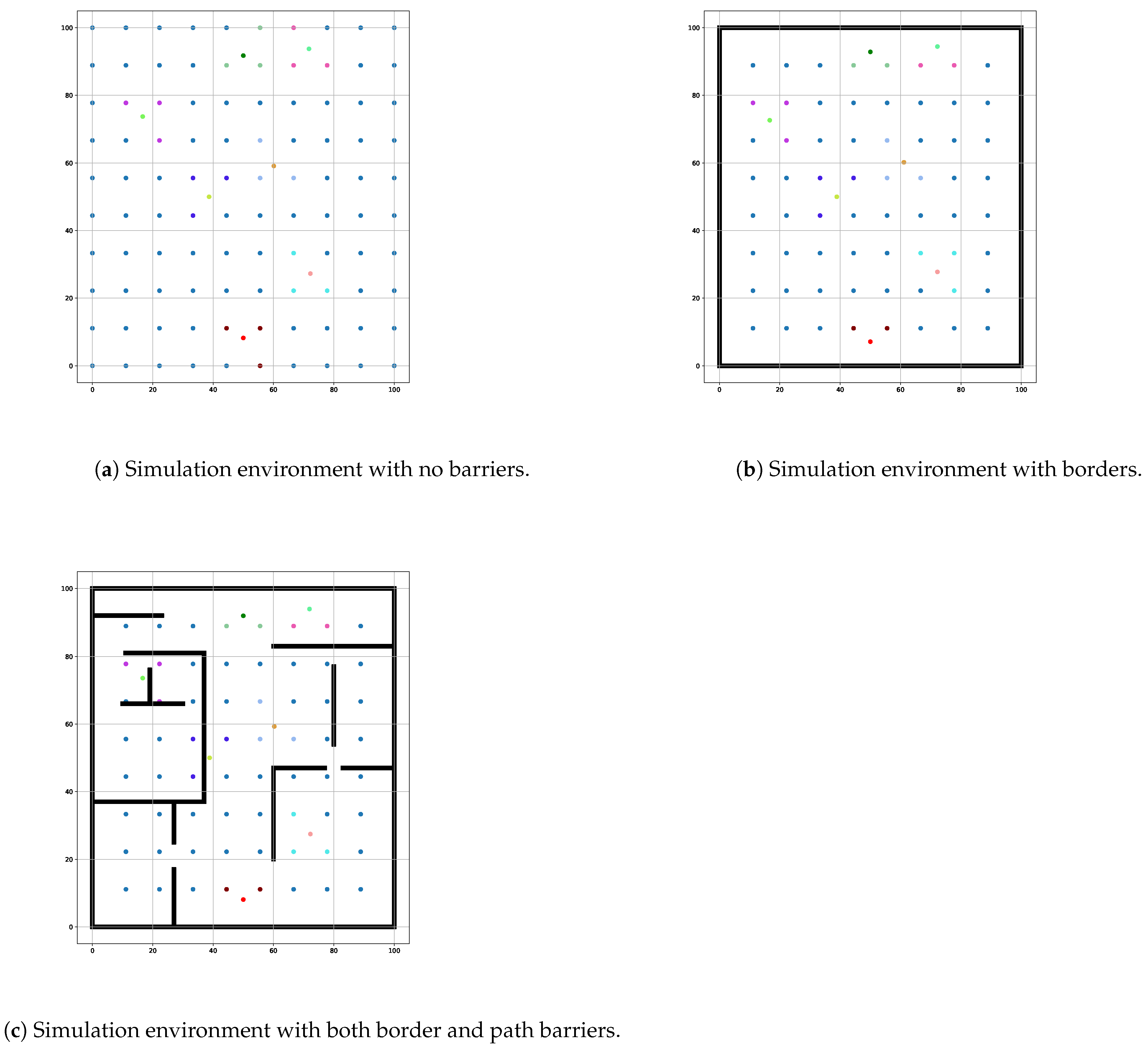

The proposed algorithm facilitates an organizational convenience by allowing organizations to utilize the simulated tool/code prior to implementing the actual algorithm. This initial phase focuses on mapping the physical indoor environment into a simulated grid layout. The grid is designed by uniformly distributing APs, enabling accurate indoor tracking via RSSI data.

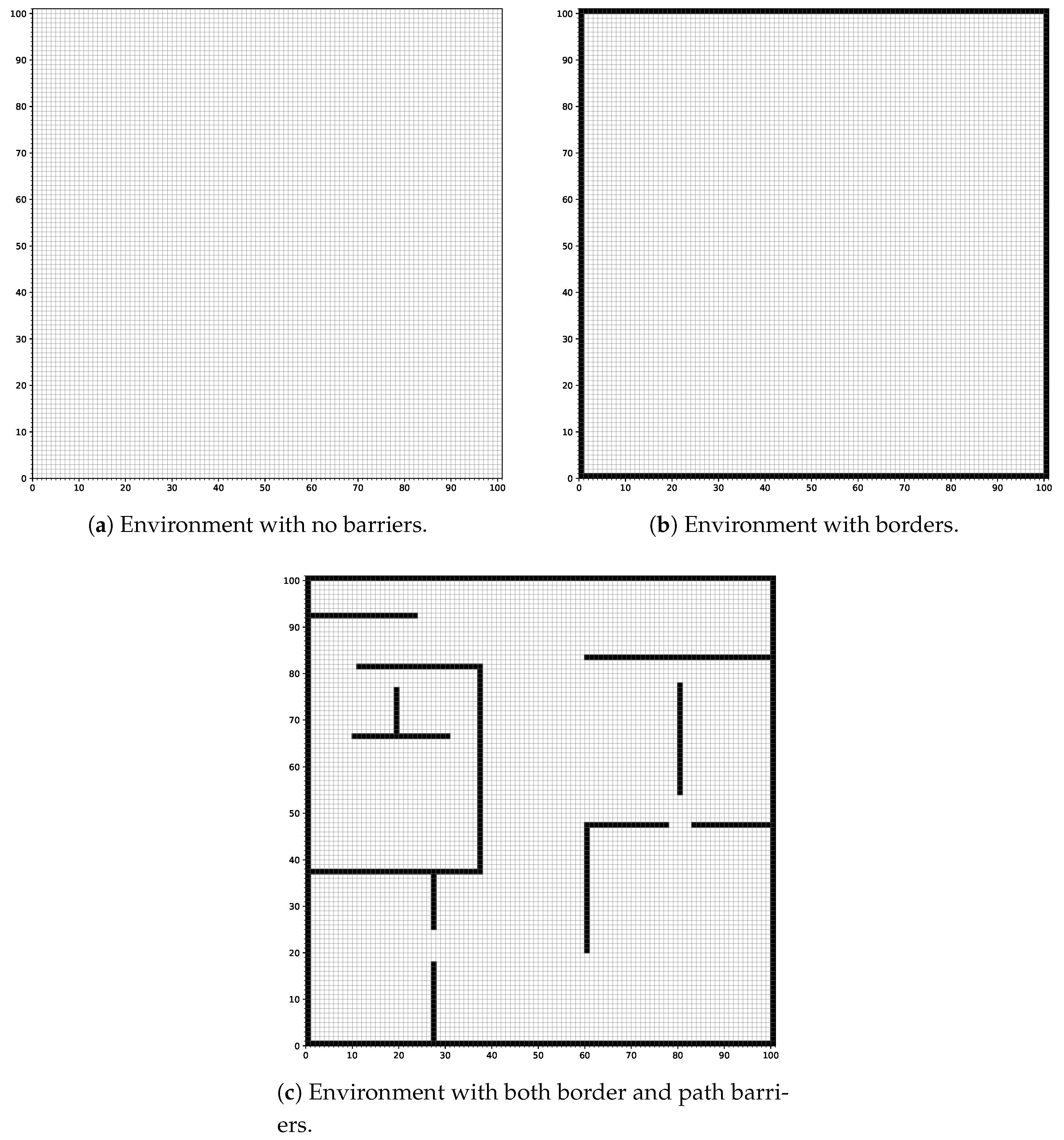

To enhance user interaction, a GUI captures user inputs for barrier placement, dynamically reflecting any adjustments made. This approach ensures the placement of barriers does not exceed grid boundaries, facilitating the identification of the shortest path while avoiding obstacles. The dynamic GUI is illustrated in Figure 2, underscoring its role in fostering user engagement.

6.2. User Convenience

Enhancing user convenience is a central goal of the iterative A* algorithm and path optimization features. Following the determination of user and checkpoint coordinates, the iterative A* algorithm computes the most efficient route that navigates through all checkpoints to reach the final destination. The algorithm initiates with all nodes assigned an infinite cost and recalibrates based on user movement and proximity to checkpoints, as illustrated in equation (

9). In the initial iteration, the algorithm identifies the nearest checkpoint based on the minimum steps required, effectively streamlining user navigation. The total iterations are defined by equation (

10).

6.3. User Experience

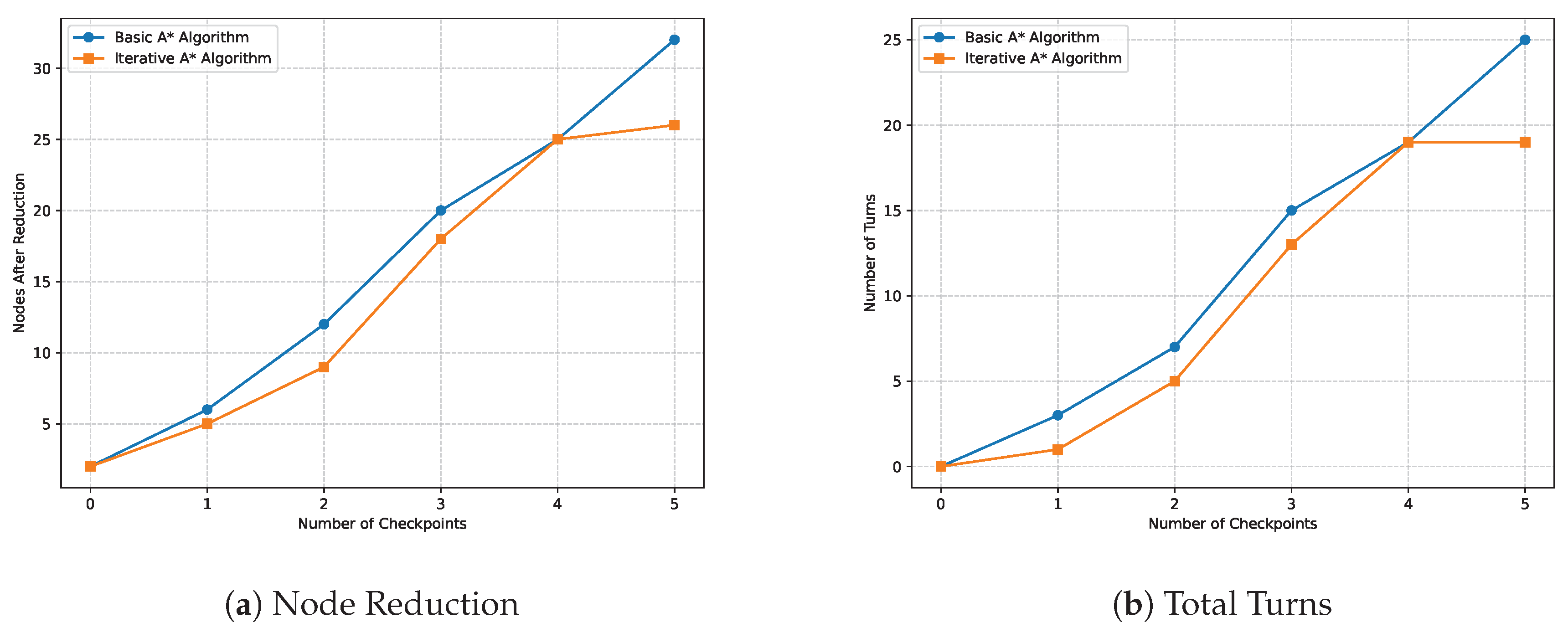

To further enhance user experience, a node reduction algorithm is integrated to optimize the path determined by the iterative A* algorithm. This process reduces the number of nodes in the path, ensuring a smoother trajectory. The algorithm operates by evaluating straight-line paths and eliminating unnecessary nodes, as described in Algorithm 1.

The node reduction algorithm operates by assessing each node’s position relative to its neighbors, ensuring only relevant nodes remain. This careful consideration results in a path that maintains clarity while reducing computational overhead, ultimately benefiting the user’s navigation experience.

6.4. Cost Efficiency

The integration of RSSI-based trilateration and multiple checkpoints emphasizes cost efficiency, utilizing existing environmental elements without the need for additional infrastructure. The algorithm leverages RSSI data to estimate user positions and the locations of checkpoints. By identifying the three nearest APs based on the highest RSSI values, the algorithm calculates user and checkpoint coordinates using established trilateration equations.

This efficiency is further highlighted by the ability to manage multiple checkpoints, allowing users to traverse a dynamic path through the indoor environment while utilizing the same infrastructure. The algorithm recalibrates checkpoint distances based on user movement, ensuring that the path remains optimal.

6.5. Energy Efficiency

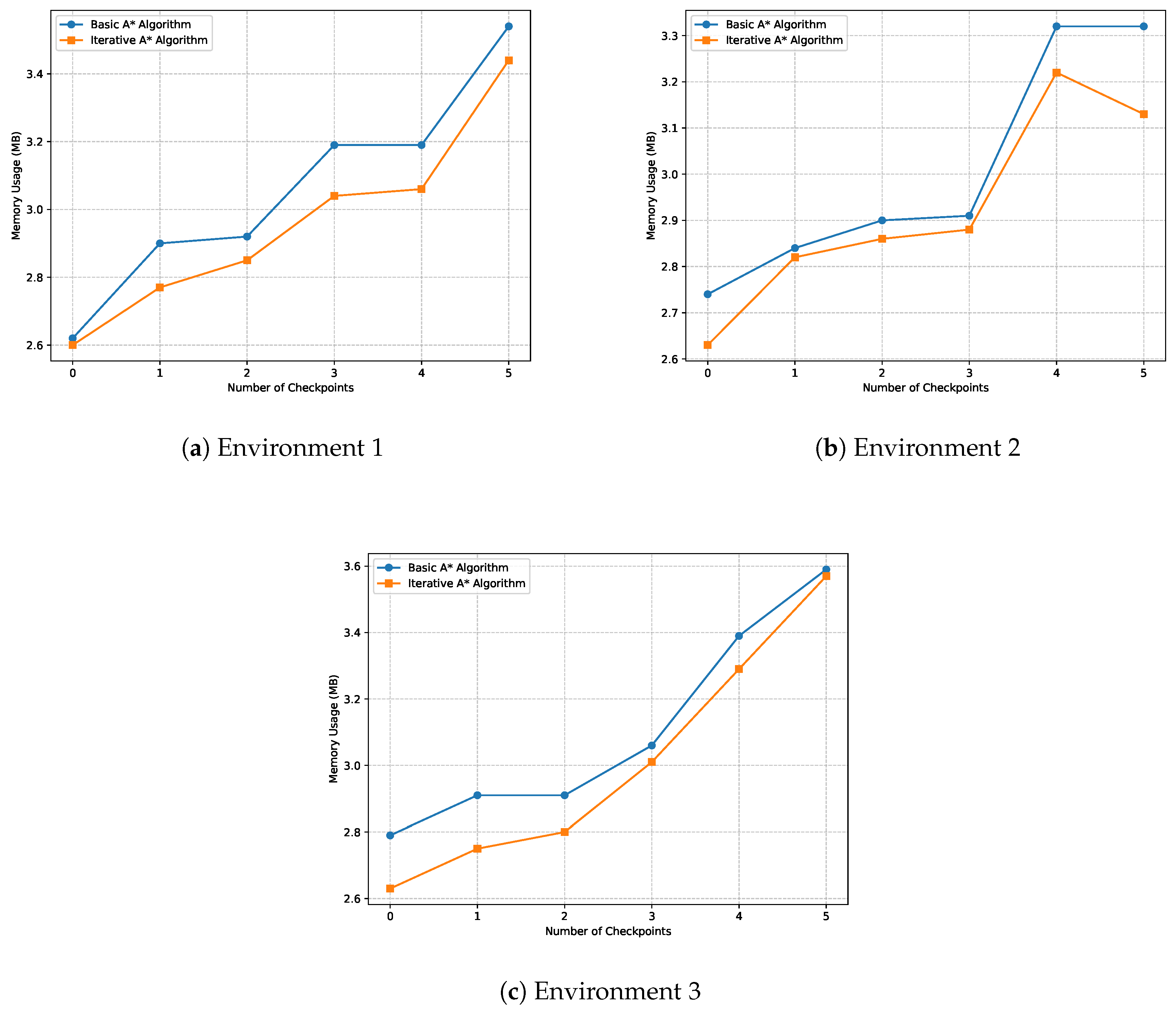

Energy efficiency is a critical feature of the proposed algorithm, setting it apart from traditional pathfinding methods. By focusing on minimizing computational overhead, the algorithm not only reduces execution time but also conserves the system’s energy resources, making it especially suitable for environments where battery-powered devices, such as robots or IoT systems, are in operation. This efficiency is achieved through the combination of iterative processing and node reduction techniques, both of which ensure that the algorithm calculates the shortest, most optimized paths with minimal resource consumption.

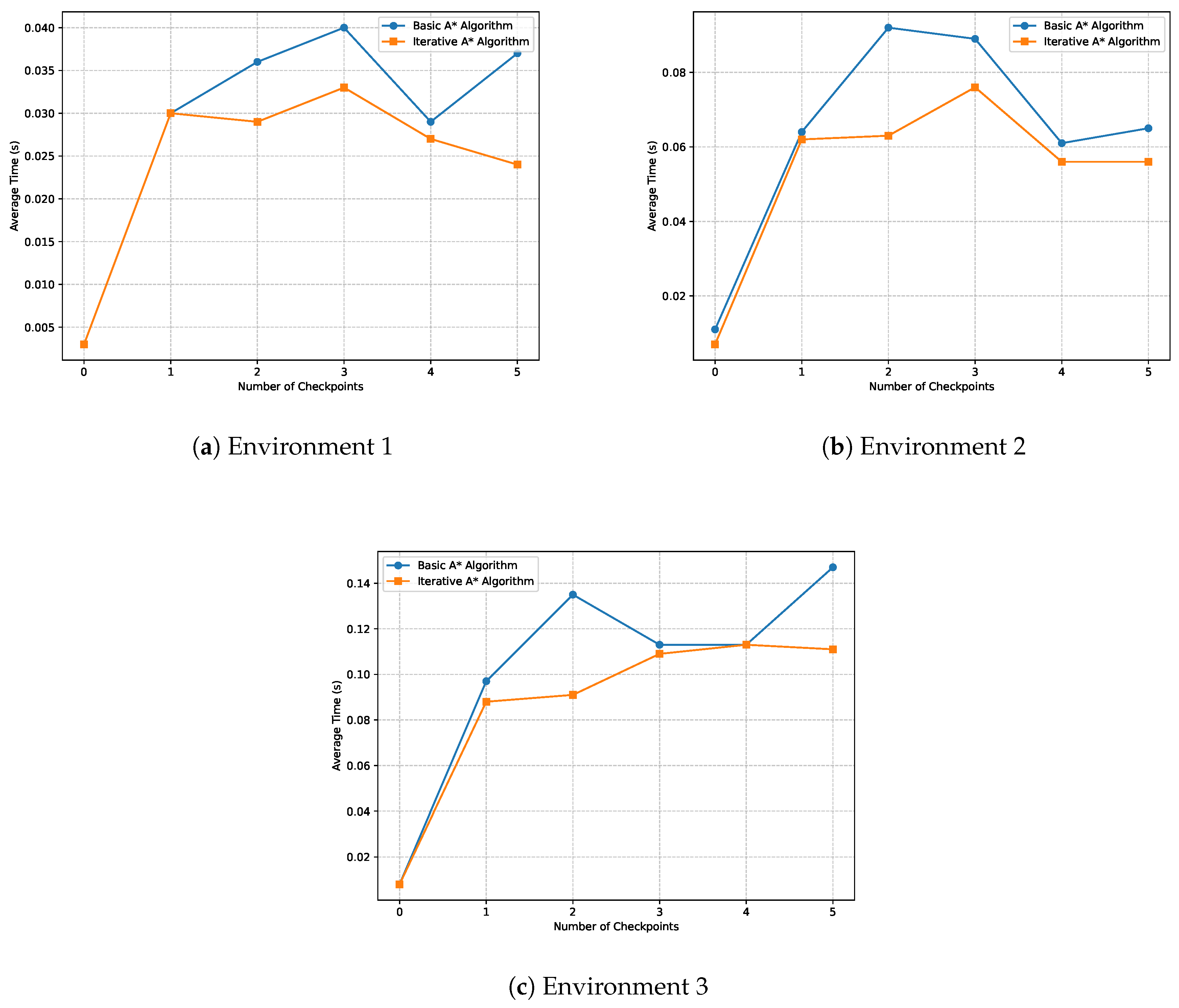

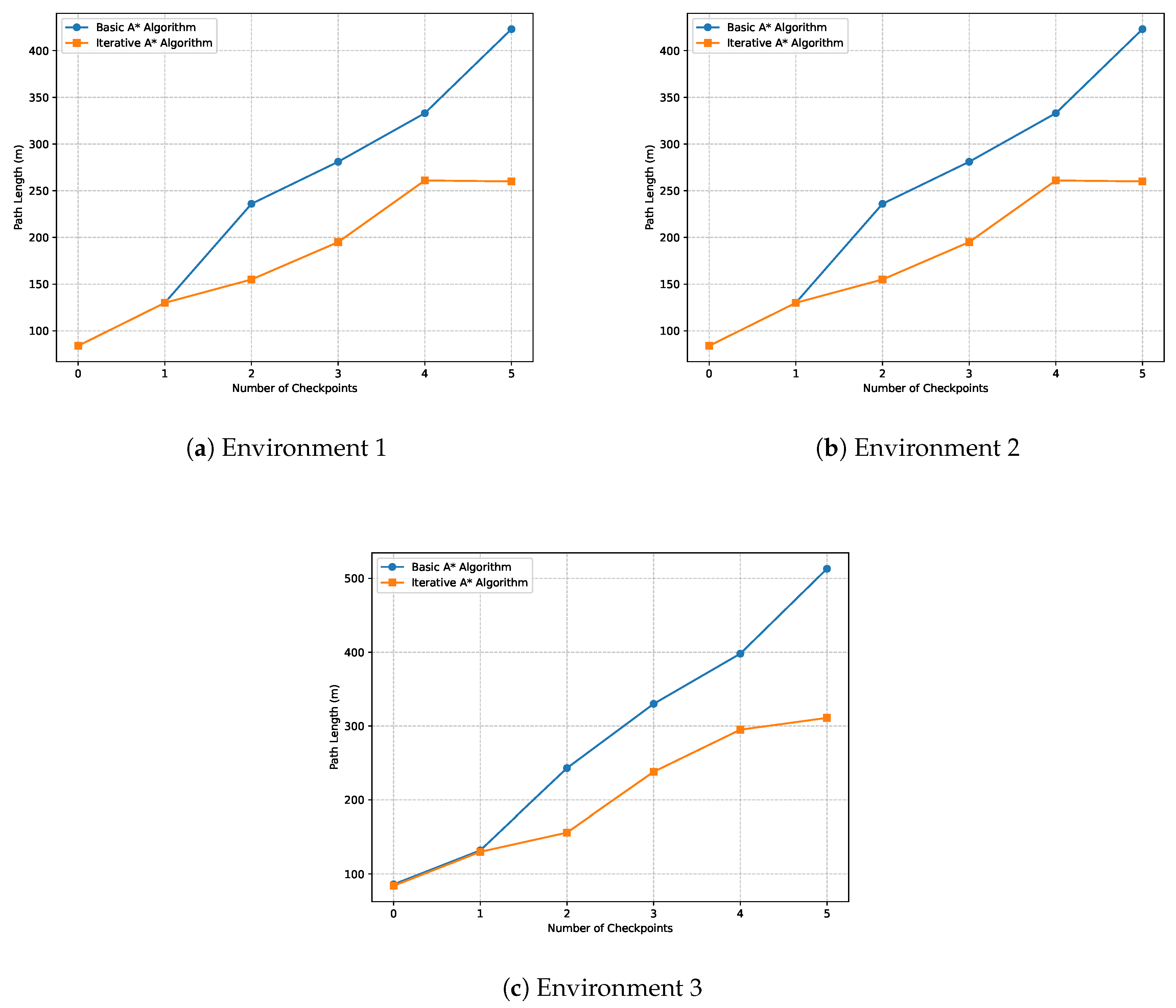

For instance, as seen in the simulation results presented in

Table 3,

Table 4, and

Table 5, the Iterative A* consistently outperforms the Basic A* algorithm in terms of memory usage and path length. This optimization directly correlates with lower power consumption. A robot employing the Iterative A* algorithm, for example, would require fewer computational cycles to compute paths, resulting in reduced energy usage and extended operational time. The reduction in nodes, particularly after the node reduction phase, further amplifies this energy-saving characteristic, as fewer nodes translate to less processing and less strain on the hardware.

In addition, the algorithm’s efficiency in navigating complex environments, such as those with borders and static obstacles, showcases its ability to handle increased complexity without a proportional rise in energy consumption. By leveraging efficient pathfinding strategies, the algorithm avoids the pitfalls of traditional approaches that may unnecessarily expend energy recalculating redundant paths or processing excessive nodes. This distinction is vital in real-world applications, such as search-and-rescue operations or warehouse automation, where energy efficiency directly influences the system’s overall performance and sustainability.

6.6. Application

The proposed algorithm has a wide range of practical applications, particularly in environments where indoor navigation, positioning, and path optimization are critical. Its adaptability makes it highly suitable for industries and sectors that require efficient movement through complex indoor spaces while accounting for obstacles and varying layouts.

One key application is in automated warehouse management. In modern warehouses, robots and autonomous vehicles are increasingly used to streamline inventory management and product retrieval. By leveraging the proposed algorithm, these systems can dynamically navigate through warehouse aisles, avoiding barriers such as shelves or temporary obstructions. The use of RSSI-based trilateration ensures precise indoor positioning, enabling the algorithm to guide robots along the most efficient paths, even as the environment evolves due to rearranged inventory or new shelving configurations.

In healthcare facilities, such as hospitals or large medical centers, the algorithm can be used for guiding autonomous service robots or for providing real-time navigation assistance to both staff and visitors. These environments often feature complex layouts with multiple checkpoints—such as patient rooms, medical supply areas, or operating theaters—that must be reached efficiently. The proposed pathfinding and node reduction techniques ensure that essential services are delivered quickly, improving overall facility efficiency and enhancing patient care.

Another potential application lies in smart building management. Modern smart buildings rely on sophisticated systems to monitor and control various functions, from lighting and security to heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC). The proposed algorithm can be integrated into these systems to assist with tasks such as monitoring maintenance robots as they navigate through buildings to perform inspections or repairs. The ability to adapt to real-time changes in the environment ensures that these systems can operate continuously, even when unforeseen obstacles are introduced.

In the field of indoor rescue operations, particularly in situations where GPS signals are unavailable or unreliable, such as underground facilities or high-rise buildings, the algorithm can play a pivotal role. Rescue robots equipped with the algorithm can efficiently navigate disaster-stricken environments, locating survivors and delivering critical supplies. The combination of RSSI-based positioning and optimized pathfinding minimizes delays, which is essential when time-sensitive operations are involved.

Moreover, the algorithm finds practical use in indoor retail environments. Retailers are adopting technology-driven solutions to enhance customer experience, such as in-store navigation apps that guide customers to products in large, complex shopping centers or supermarkets. The proposed algorithm, when implemented in such systems, can offer precise directions while accounting for temporary store rearrangements or high-traffic areas, thus improving both customer satisfaction and operational efficiency.

Finally, in robotic swarm intelligence, the algorithm can serve as a key component in coordinating multiple robots working together in enclosed spaces. Swarm robots, used in tasks such as environmental monitoring, cleaning, or surveillance, need to efficiently cover an area without colliding with one another or missing any sections. The algorithm’s ability to handle multiple checkpoints and dynamically adjust paths based on real-time positioning allows for smooth and efficient coordination of these swarms, maximizing their coverage while minimizing operational costs.

6.7. Limitations and Future Considerations

While the proposed algorithm offers a robust solution for indoor positioning and navigation, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the reliance on RSSI-based trilateration introduces inherent inaccuracies due to signal interference, multi-path effects, and fluctuations in signal strength within indoor environments. Such variations can reduce the precision of location estimates, particularly in dynamic environments with high-density barriers or reflective surfaces. To mitigate this, future research could explore the integration of alternative localization techniques, such as time-of-flight or angle-of-arrival measurements, which may provide more stable and accurate positioning in complex indoor environments.

Another limitation pertains to the scalability of the iterative A* algorithm when applied to large-scale environments. As the number of checkpoints increases, the computational cost and time required for path optimization grow exponentially. This limitation becomes especially apparent when dealing with highly cluttered environments where numerous obstacles must be accounted for. Future improvements could focus on optimizing the search space and incorporating hierarchical or multi-level pathfinding techniques, which would allow for faster computations without sacrificing accuracy. Additionally, leveraging parallel computing or cloud-based solutions could significantly reduce computation time, making the algorithm more suitable for real-time applications in larger, more complex environments.

The node reduction technique, while effective in simplifying paths, may occasionally eliminate nodes that contribute to smoother trajectories, particularly in environments where fine-tuned navigation is essential. Future research could explore adaptive node reduction strategies that preserve critical waypoints based on the specific characteristics of the environment, user preferences, or the robot’s physical constraints.

Moreover, the current algorithm does not account for dynamic changes in the environment, such as moving obstacles or alterations in the layout post-deployment. Addressing this limitation will require future work to integrate real-time environmental updates and re-calculations into the pathfinding process. This could involve combining machine learning techniques to predict obstacle movements or incorporating simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) to adaptively update the environment in real-time.

In terms of applicability, while the algorithm has been successfully implemented in a controlled simulation and later deployed on a microcontroller, its performance in real-world environments is still subject to constraints such as hardware limitations, sensor accuracy, and environmental unpredictability. Future work should explore more extensive real-world testing in various settings, including highly dynamic environments, to better assess the algorithm’s robustness and adaptability. Investigating the potential of integrating additional sensory inputs, such as lidar or computer vision, could further enhance the algorithm’s effectiveness in diverse real-world scenarios.

Finally, expanding the algorithm’s applicability to multi-agent systems is a promising direction. Coordinating multiple robots to navigate complex environments introduces additional challenges in path planning, collision avoidance, and resource optimization. Future research should focus on developing distributed algorithms that allow multiple agents to operate efficiently within the same environment, further extending the versatility of the proposed solution.

7. Conclusion

In this paper, we presented a comprehensive algorithm designed to optimize indoor positioning and navigation. By integrating multiple features such as RSSI-based trilateration, iterative A* pathfinding, and node reduction, the algorithm achieves both efficiency and accuracy in navigating dynamic environments. The user-friendly interface allows for seamless customization of barriers and checkpoints, ensuring the tool adapts to a wide range of indoor layouts. This adaptability, combined with the algorithm’s cost efficiency through the use of existing infrastructure, demonstrates its practical applicability.

Key performance metrics, including computational runtime, memory usage, and the number of steps required, highlight the algorithm’s balance between complexity and performance. Furthermore, the incorporation of a node reduction technique enhances the efficiency of pathfinding, reducing the computational burden without sacrificing precision. The algorithm’s deployment onto a microcontroller for real-world implementation bridges the gap between theoretical simulation and practical use.

In conclusion, this algorithm not only addresses the complexities of indoor navigation but also offers a scalable and adaptable solution that can be implemented across diverse environments. Its integration of user interaction, computational optimization, and real-world applicability positions it as a valuable contribution to the field of indoor positioning systems.