Submitted:

05 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

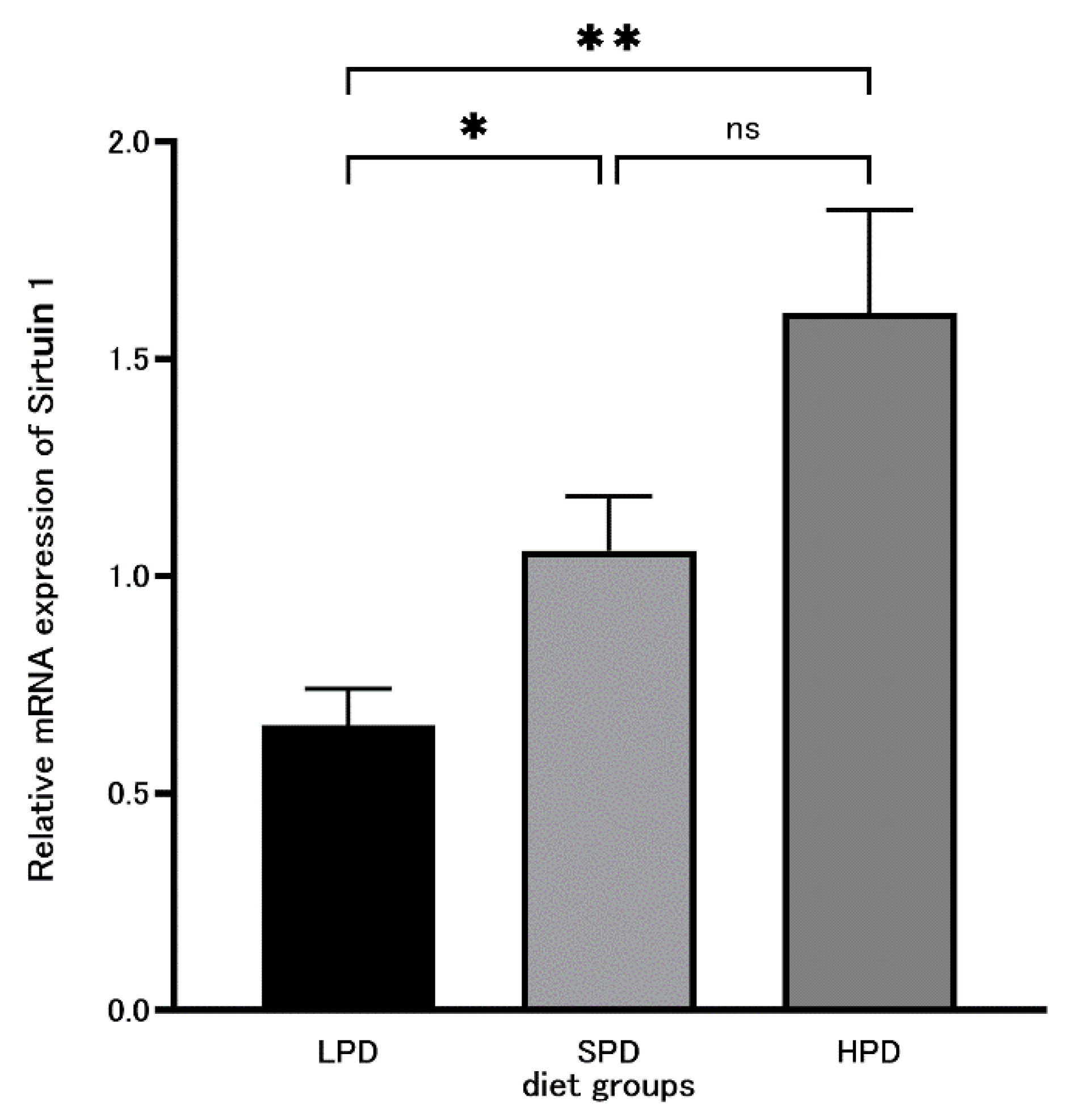

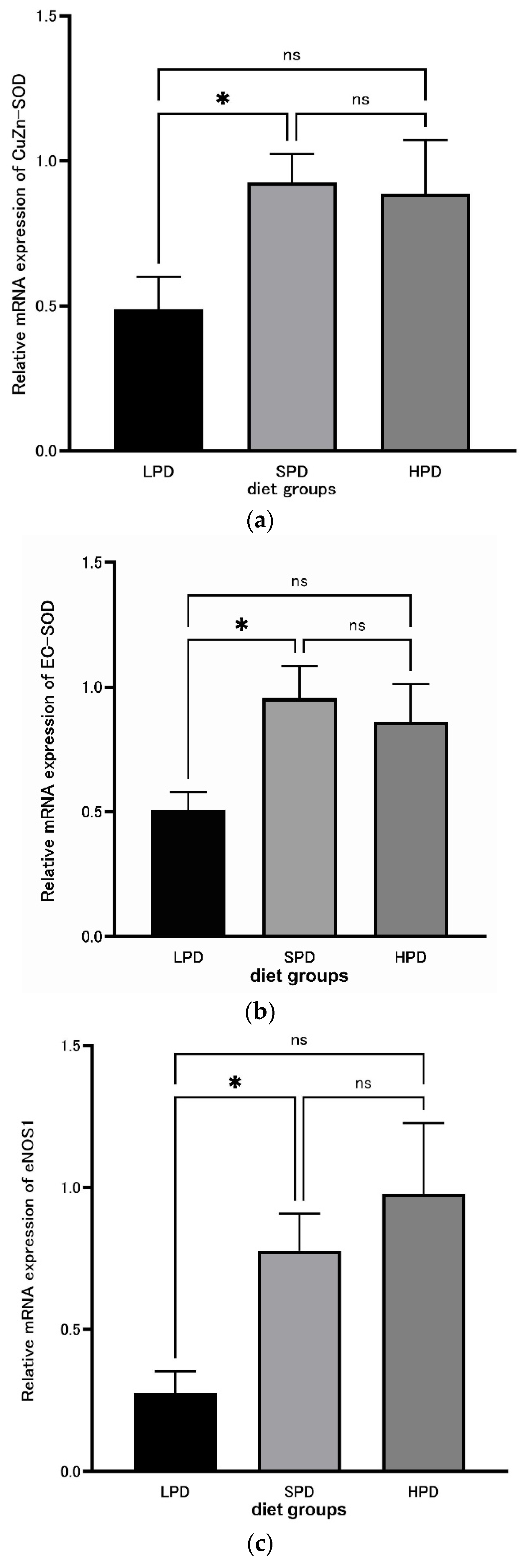

Background: The relationship between aging or disease and diets, as in the relationship between the intake of calories and disease, has been studied. Appropriate protein intake is im-portant for disease, frailty, and the life span. However, little is knew regarding to protein diet on any disease and lifespan. So we analyze the effects of high protein diets on rat liver oxidative stress and tumor marker. Methodology: Rats were separated into three groups: LPD with 5% protein, SPD with 20% protein, and HPD with 40% protein, administered over 4 weeks. The qRT-PCR method was used for measuring mRNA expression levels. as the expression of the an-ti-aging-related enzyme Sirtuin 1, superoxide dismutase (SOD), CuZn-SOD, EC-SOD, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), tumor suppressor protein p53, and nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF-1). Results: A significant difference (p = 0.03853) was observed between the LPD and SPD groups for Sirtuin 1 and also between the LPD and HPD groups (p = 0.004914). There were signif-icant differences in CuZn-SOD and EC-SOD between the LPD and SPD groups (CuZn-SOD: p = 0.02062, EC-SOD: p = 0.01906). A significant difference (p = 0.01359) between the LPD and SPD groups was also observed for eNOS. Conclusions: A significant difference in Sirtuin 1 expression was observed between the LPD and SPD, and between the LPD and HPD groups, indicates that high protein intake promotes Sirtuin 1 and prevents aging. As for CuZn-SOD, EC-SOD, and eNOS, the significant difference between the SPD and LPD groups indicates that low protein intake lowers the production of SOD and increases reactive oxygen species (ROS). An appropriate amount of protein is necessary for the prevention of aging, lifestyle-related diseases, and arteriosclerotic diseases caused by oxidative stress and to extend the life span.

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rat

2.2. Sample Collection

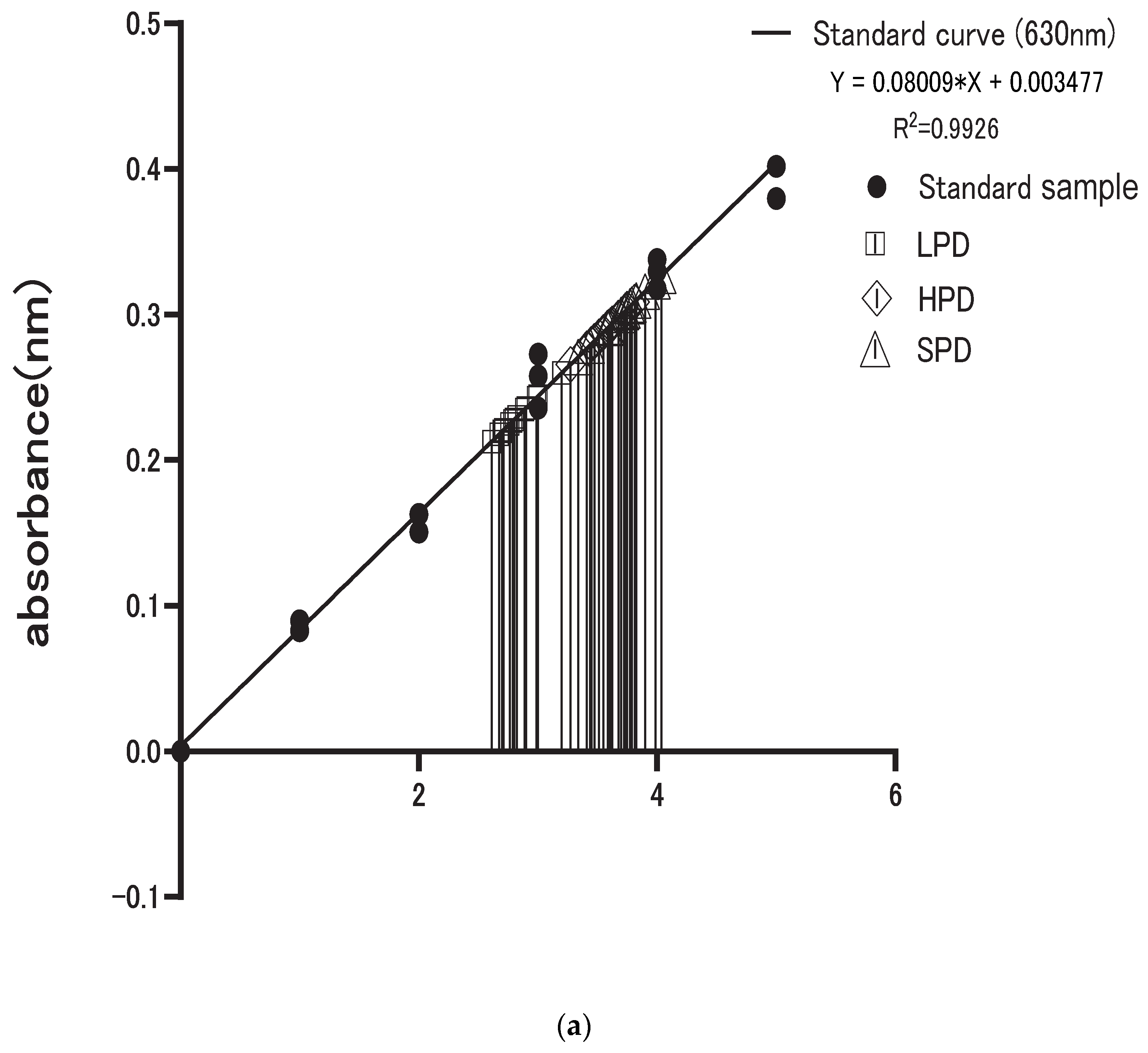

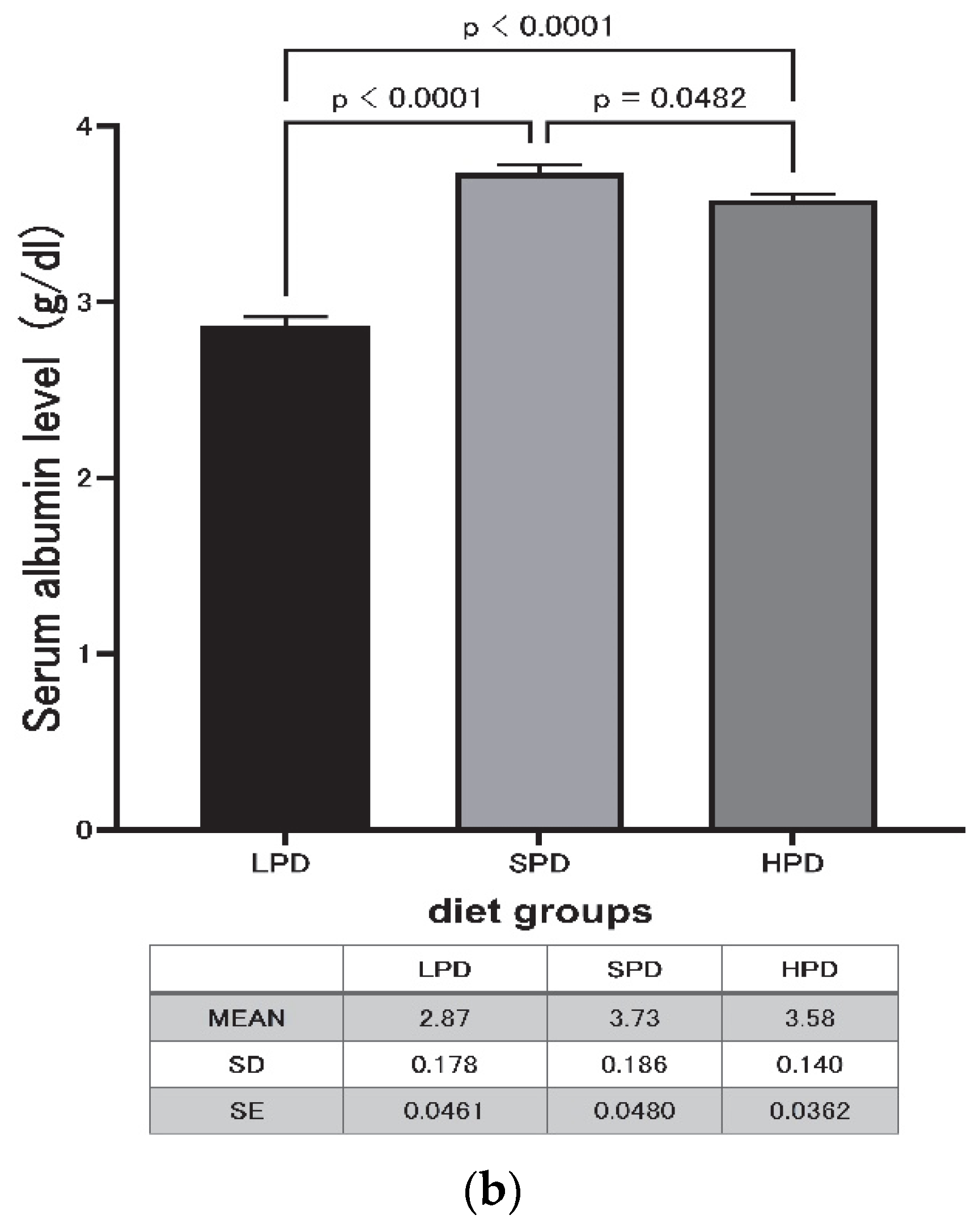

2.3. Determination of Serum Total Protein and Serum Albumin Levels

2.4. Quantitative Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

2.4.1. Extraction of Total RNA and cDNA Production

2.4.2. mRNA Measurement

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

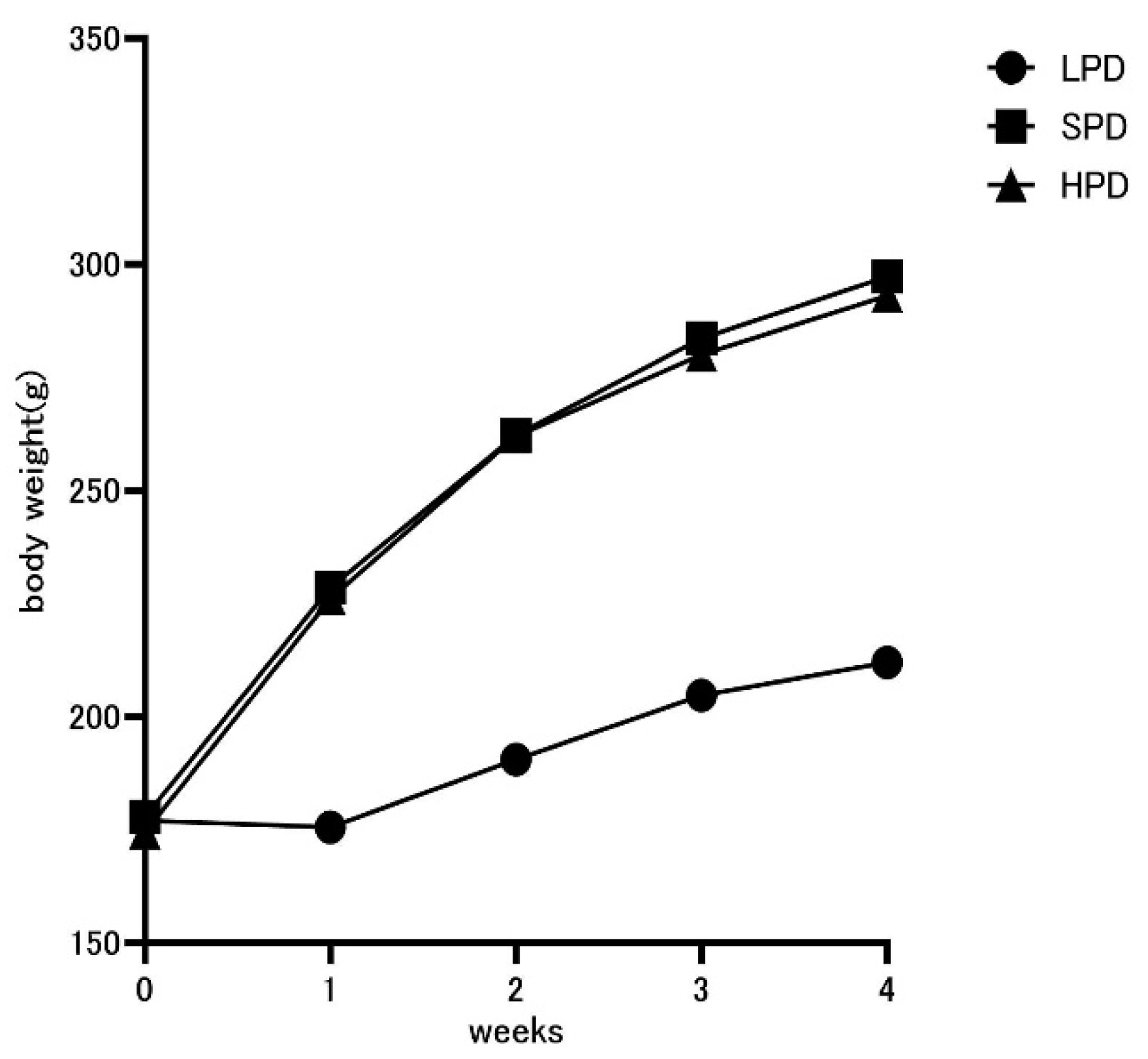

3.1. Effects of High Protein Intake on Body Weight

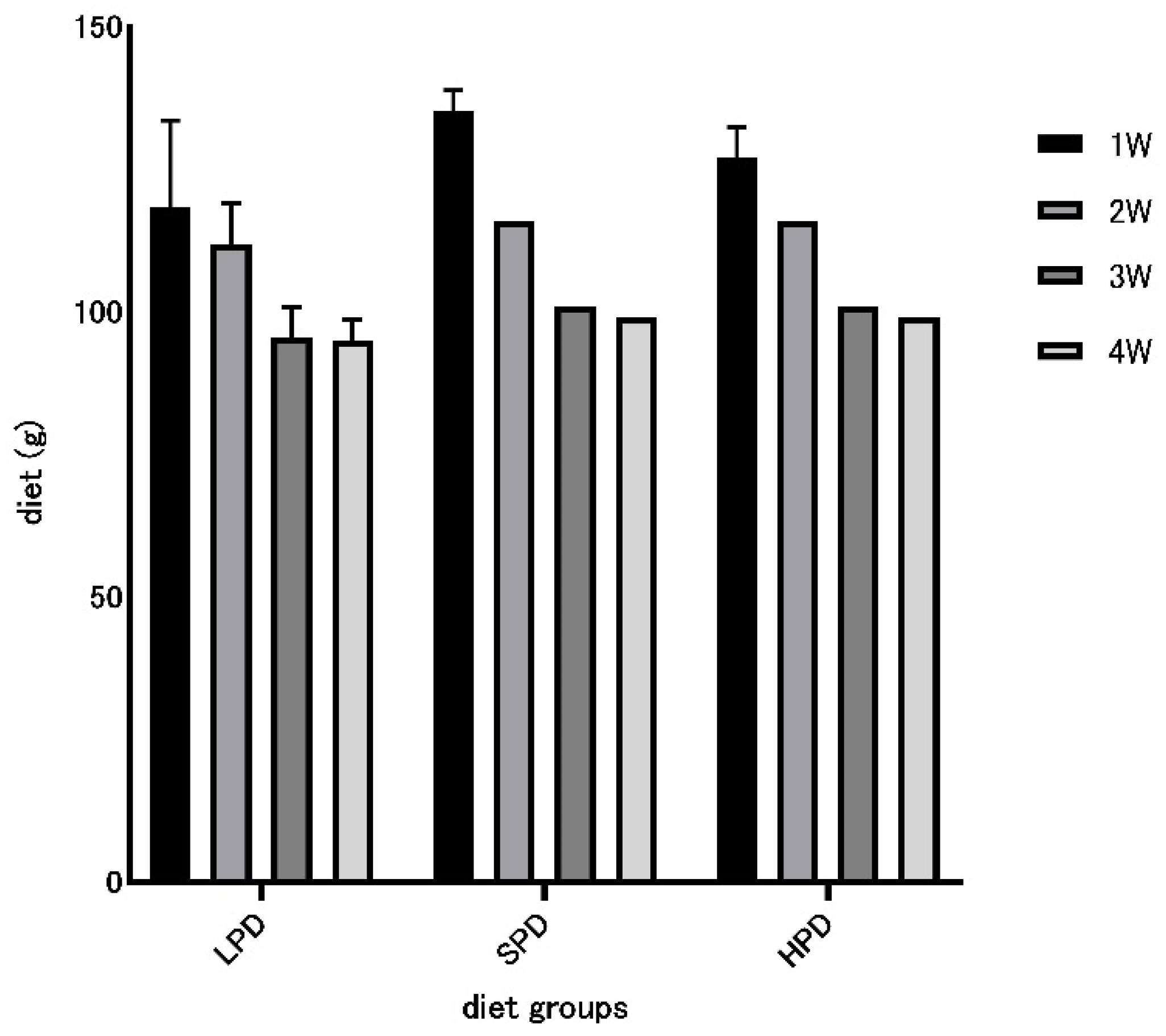

3.2. Effect of High Protein Intake on Serum Protein Levels

3.3. Sirtuin 1

3.4. SOD

3.5. P53 and NRF-1

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McCay, C.M.; Crowell, M.F.; Maynard, L.A. The effect of retarded growth upon the length of life span and upon the ultimate body size. 1935. Nutrition 1989, 5, 155–171, discussion 172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zelko, I.N.; Mariani, T.J.; Folz, R.J. Superoxide dismutase multigene family: A comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz, D.; Serrano, M. SIRTUIN 1: Recent lessons from mouse models. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tikoo, K.; Tripathi, D.N.; Kabra, D.G.; Sharma, V.; Gaikwad, A.B. Intermittent fasting prevents the progression of type I diabetic nephropathy in rats and changes the expression of Sir2 and p53. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astrup, A.; Raben, A.; Geiker, N. The role of higher protein diets in weight control and obesity-related comorbidities. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petzke, K.J.; Elsner, A.; Proll, J.; Thielecke, F.; Metges, C.C. Long-term high protein intake does not increase oxidative stress in rats. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 2889–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boily, G.; Seifert, E.L.; Bevilacqua, L.; He, X.H.; Sabourin, G.; Estey, C.; Moffat, C.; Crawford, S.; Saliba, S.; Jardine, K.; et al. Sirtuin 1 regulates energy metabolism and response to caloric restriction in mice. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercken, E.M.; Hu, J.; Krzysik-Walker, S.; Wei, M.; Li, Y.; McBurney, M.W.; de Cabo, R.; Longo, V.D. SIRTUIN 1 but not its increased expression is essential for lifespan extension in caloric-restricted mice. Aging Cell 2014, 13, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfluger, P.T.; Herranz, D.; Velasco-Miguel, S.; Serrano, M.; Tschop, M.H. Sirtuin 1 protects against high-fat diet-induced metabolic damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9793–9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.J.; Fwu, M.L. Protein insufficiency aggravates the enhanced lipid peroxidation and reduced activities of antioxidative enzymes in rats fed diets high in polyunsaturated fat. J. Nutr. 1992, 122, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.J.; Fwu, M.L. Degree of protein deficiency affects the extent of the depression of the antioxidative enzyme activities and the enhancement of tissue lipid peroxidation in rats. J. Nutr. 1993, 123, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, W.W.; Dridi, S.; Shouse, S.A.; Wu, H.; Hawley, A.; Lee, S.O.; Gu, X.; Baum, J.I. A High-Protein Diet Reduces Weight Gain, Decreases Food Intake, Decreases Liver Fat Deposition, and Improves Markers of Muscle Metabolism in Obese Zucker Rats. Nutrients 2017, 9, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLennan, W.J.; Martin, P.; Mason, B.J. Protein intake and serum albumin levels in the elderly. Gerontology 1977, 23, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Higashiyama, A.; Kokubo, Y.; Ono, Y.; Okayama, A.; Okamura, T. Protein intakes and serum albumin levels in a Japanese general population: NIPPON DATA90. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 20 (Suppl. 3), S531–S536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slonaker, J.R. The Effect of Different Per Cents of Protein in the Diet. Am. J. Physiol.-Leg. Content 1931, 98, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, R.J.; Anderson, R.M.; Johnson, S.C.; Kastman, E.K.; Kosmatka, K.J.; Beasley, T.M.; Allison, D.B.; Cruzen, C.; Simmons, H.A.; Kemnitz, J.W.; et al. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science 2009, 325, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, T.E.; Kovács, S.J.; Ehsani, A.A.; Klein, S.; Holloszy, J.O.; Fontana, L. Long-term caloric restriction ameliorates the decline in diastolic function in humans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, T.; Guarente, L. SnapShot: Sirtuins, NAD, and aging. Cell Metab. 2014, 20(1), 192–192. e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, S.-I.; Guarente, L. NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2014, 24, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, S.; Yoshino, J. The importance of NAMPT/NAD/SIRTUIN 1 in the systemic regulation of metabolism and ageing. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2013, 15 (Suppl. 3), 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.K.; Barnard, R.J.; Sindhu, R.K.; Jurczak, M.; Ehdaie, A.; Vaziri, N.D. Oxidative stress and dysregulation of NAD (P) H oxidase and antioxidant enzymes in diet-induced metabolic syndrome. Metabolism 2006, 55, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, M.; McCord, I.F. Superoxide Dismutase: The first twenty years (1968–1988). J. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1988, 5, 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Marklund, S.L. Human copper-containing superoxide dismutase of high molecular weight. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 7634–7638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraci, F.M.; Didion, S.P. Vascular protection: Superoxide dismutase isoforms in the vessel wall. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukai, E.; Kume, N.; Hayashida, K.; Minami, M.; Yamada, Y.; Seino, Y.; Kita, T. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor induces expression of lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor-1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis 2004, 176, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mügge, A.; Brandes, R.; Böger, R.; Dwenger, A.; Bode-Böger, S.; Kienke, S.; Frölich, J.; Lichtlen, P. Vascular release of superoxide radicals is enhanced in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1994, 24, 994–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.J.; Scarpulla, R.C. NRF-1: A trans-activator of nuclear-encoded respiratory genes in animal cells. Genes Dev 1990, 4, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virbasius, C.A.; Virbasius, J.V.; Scarpulla, R.C. NRF-1, an activator involved in nuclear-mitochondrial interactions, utilizes a new DNA-binding domain conserved in a family of developmental regulators. Genes Dev. 1993, 7, 2431–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, W.M.; Walker, S.J.; Vrana, K.E. Quantitative RT-PCR: Pitfalls and Potential. BioTechniques 1999, 26, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, X.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Lin, X. An improvement of the 2ˆ(−delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat. Bioinform. Biomath. 2013, 3, 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, I.H. Summary comments: Epidemiological and methodological problems in determining nutritional status of older persons. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1989, 50, 1231–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, V.; Bernetti, A.; Mangone, M.; Paoloni, M. Clinical definition of sarcopenia. Clin. Cases Miner. Bone Metab. 2014, 11(3), 177–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houston, D.K.; Nicklas, B.J.; Ding, J.; Harris, T.B.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Newman, A.B.; Lee, J.S.; Sahyoun, N.R.; Visser, M.; Kritchevsky, S.B. Dietary protein intake is associated with lean mass change in older, community-dwelling adults: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.; Biolo, G.; Cederholm, T.; Cesari, M.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Morley, J.E.; Phillips, S.; Sieber, C.; Stehle, P.; Teta, D. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: A position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 542–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Asakura, K.; Suga, H.; Sasaki, S. High protein intake is associated with low prevalence of frailty among old Japanese women: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamura, T.; Hayakawa, T.; Hozawa, A.; Kadowaki, T.; Murakami, Y.; Kita, Y.; Abbott, R.D.; Okayama, A.; Ueshima, H.; Group, N.D.R. Lower levels of serum albumin and total cholesterol associated with decline in activities of daily living and excess mortality in a 12-year cohort study of elderly Japanese. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhong, G.; Li, S.; Deng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, D.; Jin, L.; Wang, X. Use of serum albumin and activities of daily living to predict mortality in long-lived individuals over 95 years of age: A population-based study. Age 2015, 37, 9809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camiletti-Moiron, D.; Aparicio, V.A.; Nebot, E.; Medina, G.; Martinez, R.; Kapravelou, G.; Andrade, A.; Porres, J.M.; Lopez-Jurado, M.; Aranda, P. High-protein diet induces oxidative stress in rat brain: Protective action of high-intensity exercise against lipid peroxidation. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 31, 866–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żebrowska, E.; Maciejczyk, M.; Żendzian-Piotrowska, M.; Zalewska, A.; Chabowski, A. High Protein Diet Induces Oxidative Stress in Rat Cerebral Cortex and Hypothalamus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, G.; Rikardt Andersen, J.; Ritz, C.; Silvestre, M.P.; Navas-Carretero, S.; Jalo, E.; Christensen, P.; Simpson, E.; Taylor, M.; Martinez, J.A.; et al. Higher Protein Intake Is Not Associated with Decreased Kidney Function in Pre-Diabetic Older Adults Following a One-Year Intervention-A Preview Sub-Study. Nutrients 2018, 10(1), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, G.J.; Rhee, C.M.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Joshi, S. The Effects of High-Protein Diets on Kidney Health and Longevity. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 31, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemoto, S.; Fergusson, M.M.; Finkel, T. Nutrient availability regulates SIRTUIN 1 through a forkhead-dependent pathway. Science 2004, 306, 2105–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Shi, Q.; Wang, W. Higher expression of SIRTUIN 1 induced resistance of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells to cisplatin. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015, 7, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakino, S.; Hasegawa, K.; Itoh, H. Sirtuin and metabolic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015, 88, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| material | LPD | SPD | HPD |

| protein (casein) | 5 | 20 | 40 |

| hydrocarbon | 76.2 | 62.9 | 41.4 |

| lipid (soybean oil) | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Cellulose | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Minerals | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Others | 3.3 | 1.6 | 3.1 |

| total (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Gene name | Accession number | Sequence (5'-3') | position and length (bp) | total bp | |||

| Sirtuin-1 | NM_001372090 | F | 5'- | GGAAC CTCTG CCTCA TCTAC AT | 3' | 734-755 (20) | 97 |

| R | 5'- | GCATACTCGCCACCTAACC | 3' | 811-830 (20) | |||

| CuZnSOD | NM_017050 | F | 5'- | GGTCCAGCGGATGAAGAG | 3' | 313-330 (18) | 77 |

| R | 5'- | GGACA CATTG GCCAC ACC | 3' | 373-390 (18) | |||

| ECSOD | NM_012880 | F | 5'- | CTTGG GAGAG CTTGT CAGGT | 3' | 99-118 (20) | 70 |

| R | 5'- | CACCA GTAGC AGGTT GCAGA | 3' | 149-168 (20) | |||

| eNOS | NM_021838 | F | 5'- | TGACC CTCAC CGATAC AACA | 3' | 1136-1155 (20) | 452 |

| R | 5'- | CGGGT GTCTA GATCC ATGC | 3' | 1148-1167 (20) | |||

| p53 | HM_030989 | F | 5'- | AGAGAGCACTGCCCACCA | 3' | 1038-1055 (18) | 110 |

| R | 5'- | AACATCTCGAAGCGCTCA | 3' | 1130-1147 (18) | |||

| NRF-1 | NM_001100708 | F | 5'- | TTATT CTGCT GTGGC TGATG G | 3' | 1286-1306 | 91 |

| R | 5'- | CCTCT GATGC TTGCG TCGTCT | 3' | 1357-1376 | |||

| GAPDH | NM_017008 | F | 5'- | ACCAC AGTCC ATGCC ATCAC | 3' | 595-614 (20) | 61 |

| R | 5'- | TCCAC CACCC TGTTG CTGTA | 3' | 1027-1046 (20) | |||

| LP | STD | HP | |

| start | 177.1±2.47 | 177.9±1.56 | 174.5±2.46 |

| 7 days | 175.6±2.18 | 228.6±2.12 | 226.1±2.82 |

| 14 days | 190.6±2.21 | 262.3±2.03 | 262.0±2.15 |

| 21 days | 204.8±2.54 | 283.7±2.38 | 280.1±2.17 |

| 28 days | 212.0±2.59 | 297.3±2.83 | 293.1±2.16 |

| LPD | SPD | HPD | |

| Mean(g/dL) | 4.86 | 5.26 | 5.00 |

| SD | 0.856 | 0.331 | 0.334 |

| SE | 0.2210 | 0.0855 | 0.0863 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).