Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

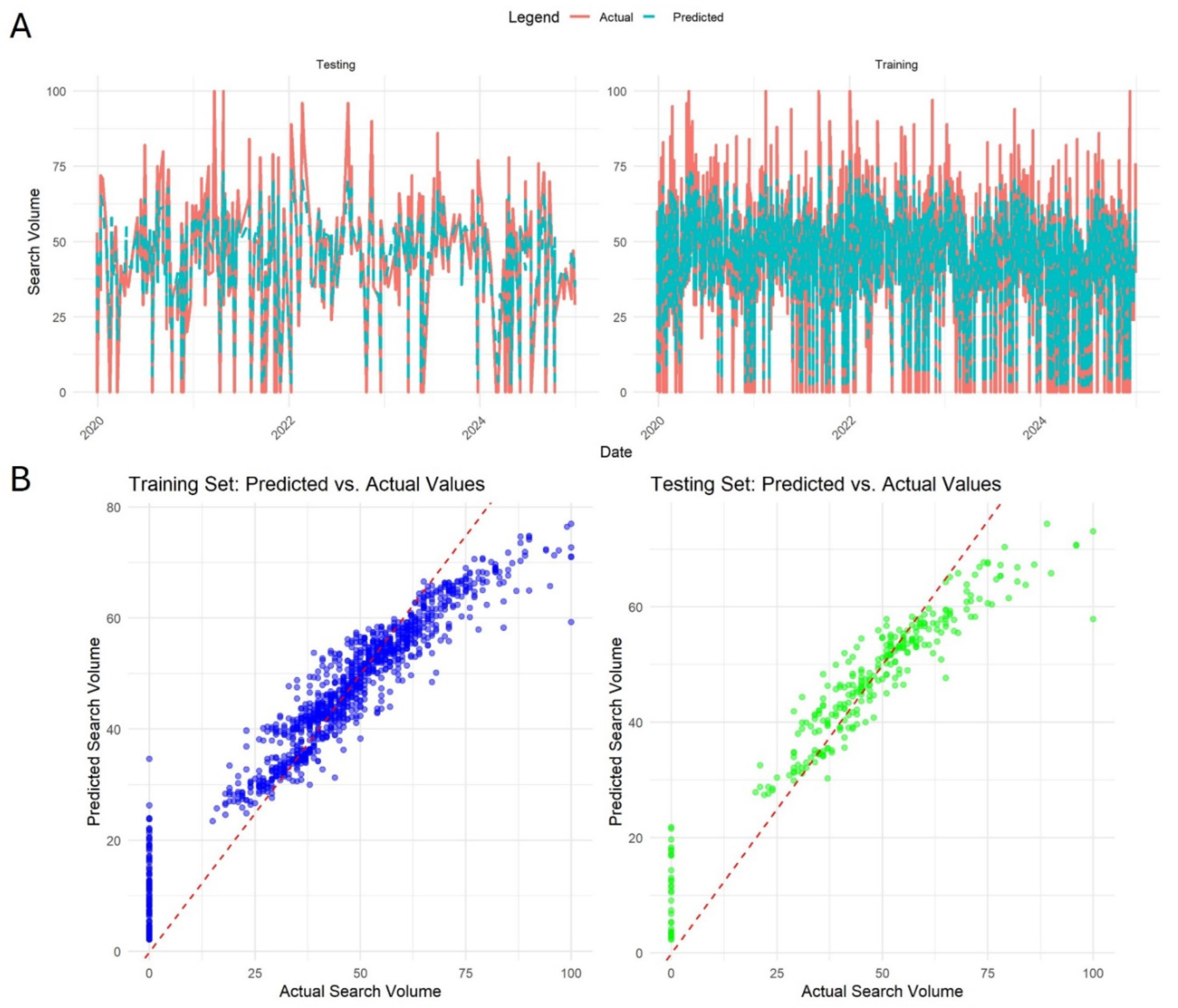

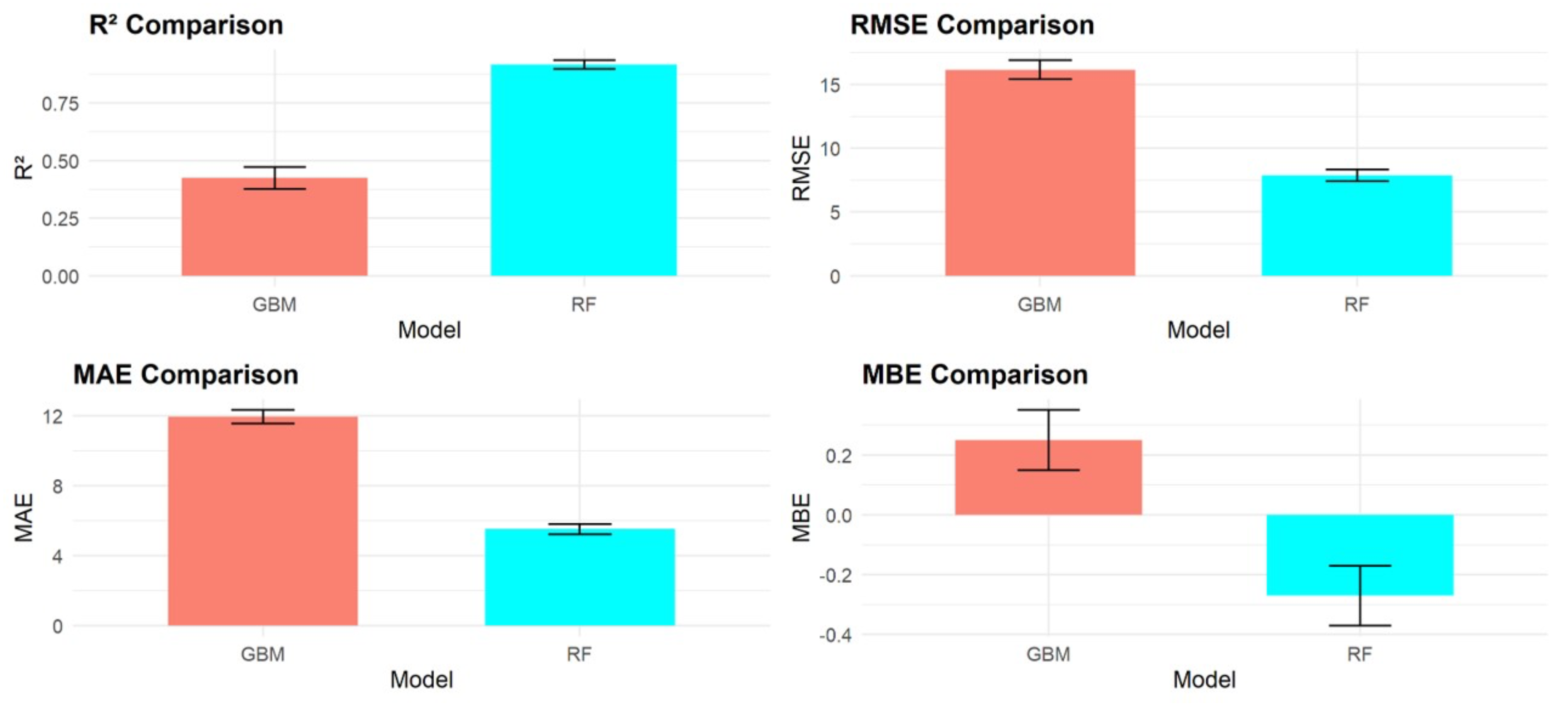

Epidural analgesia is widely regarded as the gold standard for pain relief during labor. Despite its effectiveness, significant disparities in adoption persist due to cultural, medical, and informational factors. This study aimed to analyze online search behaviors related to epidural analgesia in the six most populous European countries, evaluate temporal trends, and assess the predictive power of machine learning models for search volumes.MethodsWeekly search data from 2020 to 2024 were obtained from Google Trends for France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom (UK). Data were analyzed using linear regression, time-series decomposition, and Mann-Kendall tests to identify monotonic trends. An Auto Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model was developed to forecast search volumes for 2025. Machine learning models such as Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), were employed to evaluate the influence of variables such as country and temporal factors on search patterns. Model performance was assessed using specific metric (R², RMSE, MAE, and MBE) and statistical comparisons were made between the models.ResultsFrance and Turkey exhibited significant downward trends in search interest, while Germany showed a slight upward trend, and Italy, Spain, and the UK demonstrated stable patterns. ARIMA forecast indicated stable search volumes for most countries, with the UK reaching the highest activity. RF outperformed GBM, achieving R² values of 0.92 (testing) and 0.93 (training), with "Country" identified as the most influential predictor. Associated queries highlighted common public concerns, including epidural timing, risks, and side effects.ConclusionsThese findings reveal the value of understanding public interest in epidural analgesia to address concerns effectively. Healthcare providers should guide patients toward reliable online information. Future initiatives should include educational tools, national health programs, and interdisciplinary collaboration to enhance informed decision-making and optimize maternal care outcomes.

Keywords:

Condensation Page

- To analyze online search behaviors related to epidural labor analgesia across six European countries.

- To evaluate temporal trends, identify gaps and assess factors influencing search volumes.

- What are the key findings?

- Search trends vary across countries, reflecting differences in public interest on epidural labor analgesia.

- The UK exhibited the highest and most consistent search activity, while France and Turkey showed declining trends.

- Predictive modeling identified “Country” as the most influential predictor of search volumes.

- Highlights disparities in online interest in epidural labor analgesia across Europe.

- Demonstrates the need for tailored, evidence-based digital resources to address pregnant women’s informational needs and improve maternal health outcomes.

Introduction

Methods

Search Strategy and Data Collection

Data Processing and Analysis

Results

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARIMA | Auto Regressive Integrated Moving Average |

| GBM | Gradient Boosting Machine |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RSV | Relative Search Volume |

| LOESS | locally estimated scatterplot smoothing |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MBE | Mean Bias Error |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| PDA | Peridural Anaesthesia (German term for epidural analgesia) |

| UK | United Kingdom |

References

- Sng BL, Sia ATH. Maintenance of epidural labour analgesia: The old, the new and the future. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2017;31(1):15-22. [CrossRef]

- Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RM, Cyna AM, Cuthbert A. Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5(5):CD000331. [CrossRef]

- Mercieri M, Mercieri A, Paolini S, et al. Postpartum cerebral ischaemia after accidental dural puncture and epidural blood patch. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90(1):98-100.

- Callahan EC, Lee W, Aleshi P, George RB. Modern labor epidural analgesia: implications for labor outcomes and maternal-fetal health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228(5S):S1260-S1269. [CrossRef]

- Del Buono R, Pascarella G, Costa F, et al. Predicting difficult spinal anesthesia: development of a neuraxial block assessment score. Minerva Anestesiol. 2021;87(6):648-654. [CrossRef]

- Drake EJ, Coghill J, Sneyd JR. Defining competence in obstetric epidural anaesthesia for inexperienced trainees. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(6):951-957. [CrossRef]

- Mathur VA, Morris T, McNamara K. Cultural conceptions of Women’s labor pain and labor pain management: A mixed-method analysis. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2020;261:113240. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafeez AM, Alomari FK, Al Ghashmari HM, et al. Awareness and Attitude Toward Epidural Analgesia During Labor Among Pregnant Women in Taif City: A Hospital-Based Study. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e49367. [CrossRef]

- Kothari D, Bindal J. Impact of obstetric analgesia (regional vs. parenteral) on progress and outcome of labour: a review. In: ; 2011. Accessed January 3, 2025. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Impact-of-obstetric-analgesia-(regional-vs-on-and-a-Kothari-Bindal/195d70c0af2c7095483fc0c365ff9c64319c9b9f.

- Amadasun FE, Aziken ME. Knowledge And Attitude Of Pregnant Women To Epidural Analgesia In Labour. Ann Biomed Sci. 2008;7(1-2). [CrossRef]

- Brinkler R, Edwards Z, Abid S, et al. A survey of antenatal and peripartum provision of information on analgesia and anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(9):1101-1111. [CrossRef]

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, Applebaum S, Herrlich A. Major Survey Findings of Listening to Mothers(SM) III: Pregnancy and Birth: Report of the Third National U.S. Survey of Women’s Childbearing Experiences. J Perinat Educ. 2014;23(1):9-16. [CrossRef]

- Lagan BM, Sinclair M, Kernohan WG. Internet use in pregnancy informs women’s decision making: a web-based survey. Birth Berkeley Calif. 2010;37(2):106-115. [CrossRef]

- Muskens L, Boekhorst MGBM, Pop VJM, van den Heuvel MI. Browsing throughout pregnancy: The longitudinal course of social media use during pregnancy. Midwifery. 2024;129:103905. [CrossRef]

- Europe Population 2024. Accessed January 3, 2025. https://worldpopulationreview.com/continents/europe.

- Di Gennaro G, Licata F, Greco F, Beomonte Zobel B, Mallio CA. Interest in mammography across European countries: a retrospective “Google Trends” comparative study. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2023;13(11):7523-7529. [CrossRef]

- Zeger SL, Irizarry R, Peng RD. On time series analysis of public health and biomedical data. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:57-79. [CrossRef]

- Trull O, García-Díaz JC, Peiró-Signes A. Multiple seasonal STL decomposition with discrete-interval moving seasonalities. Appl Math Comput. 2022;433:127398. [CrossRef]

- Aigner W, Miksch S, Müller W, Schumann H, Tominski C. Visualizing time-oriented data—A systematic view. Comput Graph. 2007;31(3):401-409. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen E, Olsen KE, Bliddal M, Hornbak M, Persson GF, Green A. Forecasting lung cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence to year 2030. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):985. [CrossRef]

- Breiman L. Random Forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45(1):5-32. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Zhao Y, Canes A, Steinberg D, Lyashevska O, written on behalf of AME Big-Data Clinical Trial Collaborative Group. Predictive analytics with gradient boosting in clinical medicine. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(7):152. [CrossRef]

- Chicco D, Warrens MJ, Jurman G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2021;7:e623. [CrossRef]

- Nevitt J, Hancock GR. Improving the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation for Nonnormal Conditions in Structural Equation Modeling. J Exp Educ. 2000;68(3):251-268. [CrossRef]

- Di Novi C, Kovacic M, Orso CE. Online health information seeking behavior, healthcare access, and health status during exceptional times. J Econ Behav Organ. 2024;220:675-690. [CrossRef]

- Lo Bianco G, Papa A, Schatman ME, et al. Practical Advices for Treating Chronic Pain in the Time of COVID-19: A Narrative Review Focusing on Interventional Techniques. J Clin Med. 2021;10(11):2303. [CrossRef]

- Digitalisation in Europe – 2024 edition - Interactive publications - Eurostat. Accessed January 3, 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/digitalisation-2024.

- Kurup V, Considine A, Hersey D, et al. Role of the Internet as an information resource for surgical patients: a survey of 877 patients. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110(1):54-58. [CrossRef]

- Wieser T, Steurer MP, Steurer M, Dullenkopf A. Factors influencing the level of patients using the internet to gather information before anaesthesia: a single-centre survey of 815 patients in Switzerland : The internet for patient information before anaesthesia. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17(1):39. [CrossRef]

- Bakhireva LN, Young BN, Dalen J, Phelan ST, Rayburn WF. Patient utilization of information sources about safety of medications during pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 2011;56(7-8):339-343.

- Gao L ling, Larsson M, Luo S yuan. Internet use by Chinese women seeking pregnancy-related information. Midwifery. 2013;29(7):730-735. [CrossRef]

- Huberty J, Dinkel D, Beets MW, Coleman J. Describing the use of the internet for health, physical activity, and nutrition information in pregnant women. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(8):1363-1372. [CrossRef]

- Larsson M. A descriptive study of the use of the Internet by women seeking pregnancy-related information. Midwifery. 2009;25(1):14-20. [CrossRef]

- Bert F, Gualano MR, Brusaferro S, et al. Pregnancy e-health: a multicenter Italian cross-sectional study on Internet use and decision-making among pregnant women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(12):1013-1018. [CrossRef]

- Diaz JA, Griffith RA, Ng JJ, Reinert SE, Friedmann PD, Moulton AW. Patients’ use of the Internet for medical information. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(3):180-185. [CrossRef]

- Shieh C, Mays R, McDaniel A, Yu J. Health literacy and its association with the use of information sources and with barriers to information seeking in clinic-based pregnant women. Health Care Women Int. 2009;30(11):971-988. [CrossRef]

- Kavlak O, Atan SÜ, Güleç D, Oztürk R, Atay N. Pregnant women’s use of the internet in relation to their pregnancy in Izmir, Turkey. Inform Health Soc Care. 2012;37(4):253-263. [CrossRef]

- Sayakhot P, Carolan-Olah M. Internet use by pregnant women seeking pregnancy-related information: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:65. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Prado S, Sánchez-Ojeda M, Marmolejo-Martín J, Kapravelou G, Fernández-Gómez E, Martín-Salvador A. Cultural influence on the expression of labour-associated pain. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):836. [CrossRef]

- Ratiu D, Hayder AQ, Gilman E, et al. Shifting Trends in Obstetrics: An 18-year Analysis of Low-risk Births at a German University Hospital. Vivo Athens Greece. 2024;38(1):390-398. [CrossRef]

- Yu K, Ding Z, Yang J, Han X, Li T, Miao H. Bibliometric Analysis on Global Analgesia in Labor from 2002 to 2021. J Pain Res. 2023;16:1999-2013. [CrossRef]

- Pirbudak L, Balat O, Kutlar I, Uğur MG, Sarimehmetoğlu F, Oner U. Epidural analgesia in labor: Turkish obstetricians’ attitudes and knowledge. Agri Agri Algoloji Derneginin Yayin Organidir J Turk Soc Algol. 2006;18(2):41-46.

- Petruschke I, Ramsauer B, Borde T, David M. Differences in the Frequency of Use of Epidural Analgesia between Immigrant Women of Turkish Origin and Non-Immigrant Women in Germany - Explanatory Approaches and Conclusions of a Qualitative Study. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2016;76(9):972-977. [CrossRef]

- Lima-Pereira P, Bermúdez-Tamayo C, Jasienska G. Use of the Internet as a source of health information amongst participants of antenatal classes. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(3-4):322-330. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Liu W. The effect of Internet access on body weight: Evidence from China. J Health Econ. 2022;85:102670. [CrossRef]

- Dwyer DS, Liu H. The impact of consumer health information on the demand for health services. Q Rev Econ Finance. 2013;53(1):1-11. [CrossRef]

- Varrassi G, Bazzano C, Edwards WT. Effects of physical activity on maternal plasma beta-endorphin levels and perception of labor pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(3):707-712. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Leoni MLG, Shariff MN, Varrassi G. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Diagnostic Processes and Comprehensive Multimodal Models in Pain Medicine. J Pers Med. 2024;14(9):983. [CrossRef]

- Cascella M, Shariff MN, Viswanath O, Leoni MLG, Varrassi G. Ethical Considerations in the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Pain Medicine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2025;29(1):10. [CrossRef]

| Country | Slope | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | -0.0148 | -0.0217 to -0.00799 | p<0.001 |

| Germany | 0.00377 | 0.00110 to 0.00644 | 0.006 |

| Italy | -0.000775 | -0.00351 to 0.00196 | 0.58 |

| Spain | -0.00177 | -0.00665 to 0.00312 | 0.48 |

| Turkey | -0.00975 | -0.0126 to -0.00687 | p<0.001 |

| UK | 0.000865 | -0.00488 to 0.00661 | 0.77 |

| Associated queries | Percentage increase |

|---|---|

| Best time to get epidural during labor | 500% |

| How long does an epidural last during labor | 300% |

| Side effects of epidural during labor | 110% |

| Does epidural slow down labor | 90% |

| When can you get an epidural during labor | 80% |

| Epidural side effects | 70% |

| Epidural meaning | 50% |

| Risks of epidural | 50% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).