Submitted:

07 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

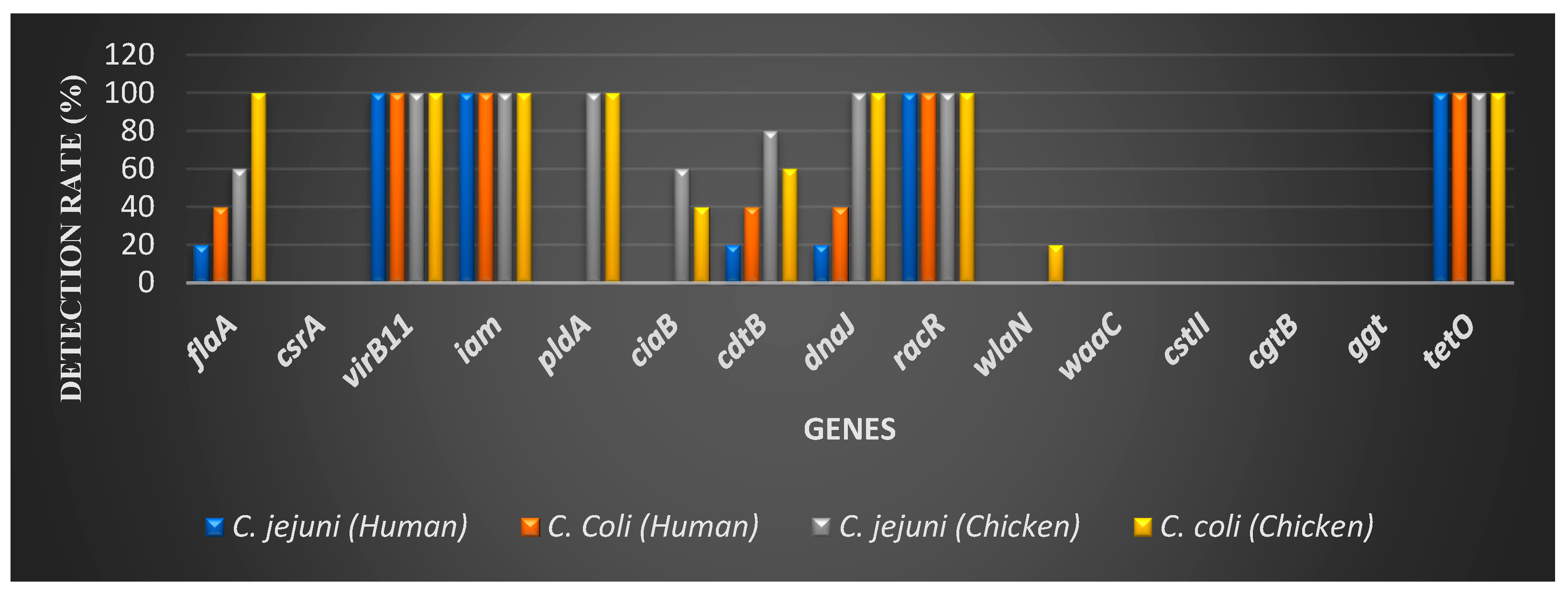

Campylobacter is considered to be the most leading bacterial cause of human gastroenteritis worldwide. Consumption of undercooked or contaminated chicken food is the main source of human campylobacteriosis. Although Campylobacter is a leading cause of gastroenteritis, data on the comparative virulence gene profiles of Campylobacter jejuni (C. jejuni) and Campylobacter coli (C. coli) from chicken and human sources in Egypt remain scarce. This study aimed to characterize the virulence genes profiles of both C. jejuni and C. coli isolated from chicken and human fecal samples in Ismailia governorate, Egypt. A total of 20 isolates of each species were screened for 15 virulence genes. All isolates carried virB11, iam, racR, and tetO. In chicken isolates, the prevalence of additional virulence genes was higher, with pldA, dnaJ, flaA, cdtB, ciaB, and wlaN detected in 100%, 100%, 100%, 80%, 60%, and 0% of C. jejuni isolates and 100%, 100%, 60%, 60%, 40%, and 20% of C. coli isolates, respectively. In contrast, human isolates showed a markedly lower prevalence, with dnaJ, flaA, and cdtB detected in 20% of C. jejuni and 40% of C. coli isolates, while pldA, ciaB, and wlaN were absent in all human isolates. qPCR revealed significantly higher expression levels of dnaJ, virB11, flaA, and iam in chicken isolates compared to human isolates, with mean fold changes of 11.5, 7.16, 5.39, and 3.72 for C. jejuni, and 8.34, 5.21, 2.84, and 2.5 for C. coli, respectively. Differential expression of racR, cdtB, and tetO was not significant. Ganglioside mimicry genes (Cst11, wlaN, Waac, ggt, and cgtB) were absent in all human isolates. These findings underscore the significant variability in virulence gene profiles between chicken and human Campylobacter isolates and highlight the importance of molecular characterization in risk assessment and epidemiological surveillance of Campylobacter infections.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and Bacterial Isolation

2.2. Molecular Confirmation and Identification of Campylobacter Virulence Genes by PCR

2.3. Gene Expression of 7 Campylobacter Virulence Genes in Chicken Samples Versus Human Samples

| Gene | Reverse transcription | Primary denaturation |

Amplification (40 cycles) | Dissociation curve (1 cycle) | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary denaturation | Annealing (Optics on) |

Extension | Secondary denaturation | Annealing |

Final denaturation | ||||

| 23S rRNA | 50˚C 30 min. |

94˚C 15 min. |

94˚C 15 sec. |

55˚C 30 sec. |

72˚C 30 sec. |

94˚C 1 min. |

55˚C 1 min. |

94˚C 1 min. |

[12] |

| cdtB | 50˚C 30 min. |

94˚C 15 min. |

94˚C 15 sec. |

51˚C 30 sec. |

72˚C 30 sec. |

94˚C 1 min. |

51˚C 1 min. |

94˚C 1 min. |

[21] |

| dnaJ | 50˚C 30 min. |

94˚C 15 min. |

94˚C 15 sec. |

42˚C 30 sec. |

72˚C 30 sec. |

94˚C 1 min. |

42˚C 1 min. |

94˚C 1 min. |

[17] |

| flaA | 50˚C 30 min. |

94˚C 15 min. |

94˚C 15 sec. |

55˚C 30 sec. |

72˚C 30 sec. |

94˚C 1 min. |

55˚C 1 min. |

94˚C 1 min. |

[14] |

| racR | 50˚C 30 min. |

94˚C 15 min. |

94˚C 15 sec. |

45˚C 30 sec. |

72˚C 30 sec. |

94˚C 1 min. |

45˚C 1 min. |

94˚C 1 min. |

[22] |

| VirB11 | 50˚C 30 min. |

94˚C 15 min. |

94˚C 15 sec. |

53˚C 30 sec. |

72˚C 30 sec. |

94˚C 1 min. |

53˚C 1 min. |

94˚C 1 min. |

[9] |

| Iam | 50˚C 30 min. |

94˚C 15 min. |

94˚C 15 sec. |

50˚C 30 sec. |

72˚C 30 sec. |

94˚C 1 min. |

50˚C 1 min. |

94˚C 1 min. |

[23] |

| tetO | 50˚C 30 min. |

94˚C 15 min. |

94˚C 15 sec. |

55˚C 30 sec. |

72˚C 30 sec. |

94˚C 1 min. |

55˚C 1 min. |

94˚C 1 min. |

[16] |

2.4. Analysis of the SYBR Green RT-PCR for Gene Expression

2.5. Ethical Statement

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Campylobacter Virulence Genes and tetO Gene

| Virulence gene | Human | Chicken | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. jejuni (%) | C. Coli (%) | C. jejuni (%) | C. Coli (%) | |

| flaA | 20 | 40 | 60 | 100 |

| csrA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| virB11 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| iam | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| pldA | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| ciaB | 0 | 0 | 60 | 40 |

| cdtB | 20 | 40 | 80 | 60 |

| dnaJ | 20 | 40 | 100 | 100 |

| racR | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| wlaN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| waaC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| cstII | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| cgtB | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ggt | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| tetO | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

3.2. Expression of 7 Campylobacter Virulence Genes in Chicken Samples Versus Human Samples

| source | C. jejuni | C. coli | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gene |

Human Group (control) |

Chicken Group |

Human Group (control) |

Chicken Group | |

| flaA | 1b | 5.39a | 1b | 2.84a | |

| VirB11 | 1b | 7.16a | 1b | 5.21a | |

| iam | 1b | 3.72a | 1b | 2.5a | |

| cdtB | 1a | 0.7a | 1a | 0.8a | |

| dnaJ | 1b | 11.5a | 1b | 8.34a | |

| racR | 1a | 0.81a | 1a | 0.86a | |

| tetO | 1a | 1.06a | 1a | 1.1a | |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kirk, M.D., et al., World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 22 Foodborne Bacterial, Protozoal, and Viral Diseases, 2010: A Data Synthesis. PLoS Med, 2015. 12(12): p. e1001921.

- Kotloff, K.L.; Nataro, J.P.; Blackwelder, W.C.; Nasrin, D.; Farag, T.H.; Panchalingam, S.; Wu, Y.; Sow, S.O.; Sur, D.; Breiman, R.F.; et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 2013, 382, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshbakht, R., et al., Occurrence of virulence genes and strain diversity of thermophilic campylobacters isolated from cattle and sheep faecal samples. Iranian Journal of Veterinary Research, 2014. 15(2): p. 138-144.

- OIE, Chapter 2. 9. 3. infection with Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli. OIE Terrestrial Manual 2017.

- Facciolà, A.; Riso, R.; Avventuroso, E.; Visalli, G.; Delia, S.A.; Laganà, P. Campylobacter: from microbiology to prevention. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2017, 58, E79–E92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pielsticker, C., G. Glünder, and S. Rautenschlein, Colonization properties of Campylobacter jejuni in chickens. European Journal of Microbiology and Immunology, 2012. 2(1): p. 61-65.

- Noormohamed, A.; Fakhr, M.K. Prevalence and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Campylobacter spp. in Oklahoma Conventional and Organic Retail Poultry. Open Microbiol. J. 2014, 8, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidal, A.B.; Colles, F.M.; Rodgers, J.D.; McCarthy, N.D.; Davies, R.H.; Maiden, M.C.J.; Clifton-Hadley, F.A. Genetic Diversity of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli Isolates from Conventional Broiler Flocks and the Impacts of Sampling Strategy and Laboratory Method. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 2347–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Niwa, H.; Itoh, K. Prevalence of 11 pathogenic genes of Campylobacter jejuni by PCR in strains isolated from humans, poultry meat and broiler and bovine faeces. J. Med Microbiol. 2003, 52, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizal, A., A. Kumar, and A.S. Vidyarthi, Prevalence of pathogenic genes in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from poultry and human. Internet Journal of Food Safety, 2010. 12: p. 29-34.

- Steele, T.W.; McDermott, S. The use of membrane filters applied directly to the surface of agar plates for the isolation of campylobacter jejuni from feces. Pathology 1984, 16, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G., et al., Colony multiplex PCR assay for identification and differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, C. upsaliensis, and C. fetus subsp. fetus. Journal of clinical microbiology, 2002. 40(12): p. 4744-4747.

- Shin, E.; Lee, Y. Comparison of three different methods for campylobacter isolation from porcine intestines. Journal of microbiology and biotechnology 2009, 19, 647–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J., et al., Adherence to and invasion of human intestinal epithelial cells by Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates from retail meat products. Journal of food protection, 2006. 69(4): p. 768-774.

- González-Hein, G.; Huaracán, B.; García, P.; Figueroa, G. Prevalence of virulence genes in strains of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from human, bovine and broiler. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, K.; Osek, J. Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms amongCampylobacter. BioMed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 340605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chansiripornchai, N.; Sasipreeyajan, J. PCR Detection of Four Virulence-Associated Genes of Campylobacter jejuni Isolates from Thai Broilers and Their Abilities of Adhesion to and Invasion of INT-407 Cells. J. Veter- Med Sci. 2009, 71, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, D., et al., Phase variation of a β-1, 3 galactosyltransferase involved in generation of the ganglioside GM1-like lipo-oligosaccharide of Campylobacter jejuni. Molecular microbiology, 2000. 37(3): p. 501-514.

- Pratt, A.; Korolik, V. Tetracycline resistance of Australian Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2005, 55, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C., et al., Application of real-time PCR for quantitative detection of Campylobacter jejuni in poultry, milk and environmental water. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology, 2003. 38(3): p. 265-271.

- Nahar, N. and R. Rashid, Genotypic Analysis of the Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Campylobacter species in silico. Journal of Bio analysis and Biomedicine, 2018. 10(1): p. 13-23.

- Talukder, K.A.; Aslam, M.; Islam, Z.; Azmi, I.J.; Dutta, D.K.; Hossain, S.; Nur-E-Kamal, A.; Nair, G.B.; Cravioto, A.; Sack, D.A.; et al. Prevalence of Virulence Genes and Cytolethal Distending Toxin Production in Campylobacter jejuni Isolates from Diarrheal Patients in Bangladesh. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 1485–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibreel, A., et al., Incidence of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter jejuni isolated in Alberta, Canada, from 1999 to 2002, with special reference to tet (O)-mediated tetracycline resistance. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2004. 48(9): p. 3442-3450.

- Thibodeau, A.; Fravalo, P.; Yergeau, .; Arsenault, J.; Lahaye, L.; Letellier, A. Chicken Caecal Microbiome Modifications Induced by Campylobacter jejuni Colonization and by a Non-Antibiotic Feed Additive. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0131978. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Zishiri, O.T. Genetic characterisation of virulence genes associated with adherence, invasion and cytotoxicity in Campylobacter spp. isolated from commercial chickens and human clinical cases. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 2018, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinga Wieczorek, J.O., Molecular characterization of Campylobacter spp. isolated from poultry faeces.

- and carcasses in Poland. Acta Veterinaria Brno, 2011. 80: p. 19-27.

- Murphy, H.M.; Prioleau, M.D.; Borchardt, M.A.; Hynds, P.D. Review: Epidemiological evidence of groundwater contribution to global enteric disease, 1948–2015. Hydrogeol. J. 2017, 25, 981–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Min, W.; Ku, B.-K.; Kim, Y.-H. Prevalence of virulence and cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) genes in thermophilic Campylobacter spp. from dogs and humans in Gyeongnam and Busan, Korea. Korean J. Veter- Sci. 2014, 54, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stintzi, A. Gene Expression Profile of Campylobacter jejuni in Response to Growth Temperature Variation. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 2009–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Fields, J.; A Thompson, S. Campylobacter jejuni CsrA complements an Escherichia coli csrA mutation for the regulation of biofilm formation, motility and cellular morphology but not glycogen accumulation. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 233–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.J.; Alm, R.A.; Burr, D.H.; Hu, L.; Kopecko, D.J.; Ewing, C.P.; Trust, T.J.; Guerry, P. Involvement of a Plasmid in Virulence of Campylobacter jejuni 81-176. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 4384–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, K. and J. Osek, Identification of virulence genes in Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli isolates by PCR. Bull Vet Inst Pulawy, 2008. 52(1): p. 211-6.

- Krutkiewicz, A.; Klimuszko, D. Genotyping and PCR detection of potential virulence genes in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates from different sources in Poland. Folia Microbiol. 2010, 55, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, H.; Sellami, H.; Ben Hassena, A.; Gdoura, R. Prevalence of Putative Virulence Genes in Campylobacter and Arcobacter Species Isolated from Poultry and Poultry By-Products in Tunisia. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 1705–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, D.; Hannon, S.J.; Townsend, H.G.; Potter, A.; Allan, B.J. Genes coding for virulence determinants of Campylobacter jejuni in human clinical and cattle isolates from Alberta, Canada, and their potential role in colonization of poultry. Int. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazão, M.R.; Medeiros, M.I.C.; Duque, S.D.S.; Falcão, J.P. Pathogenic potential and genotypic diversity of Campylobacter jejuni: a neglected food-borne pathogen in Brazil. J. Med Microbiol. 2017, 66, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, A.C.T.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; Ramos-Cervantes, P.; Cervantes, L.-E.; Jiang, X.; Pickering, L.K. Molecular Characterization of Invasive and Noninvasive Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli Isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanain, N.A., Antimicrobial resistant Campylobacter jejuni isolated from humans and animals in Egypt. Global Veterinaria, 2011. 6(2): p. 195-200.

- Bardoň, J., et al., Virulence and antibiotic resistance genes in Campylobacter spp. in the Czech Republic. Epidemiologie, mikrobiologie, imunologie: casopis Spolecnosti pro epidemiologii a mikrobiologii Ceske lekarske spolecnosti JE Purkyne, 2017. 66(2): p. 59-66.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).