Submitted:

07 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

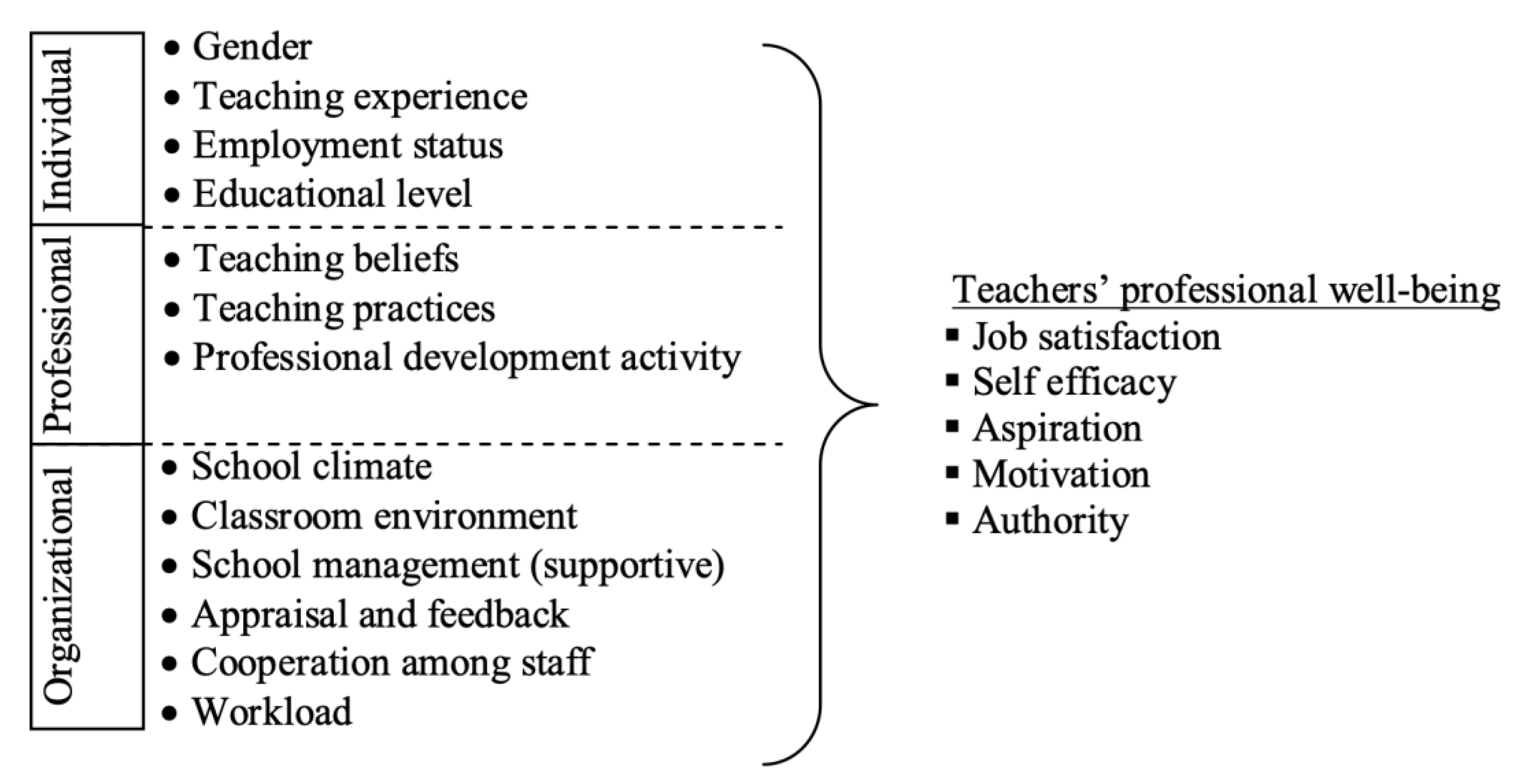

1.1. School Music Teacher’s Professional Well-being

1.2. Importance of Teacher Well-being Studies in China

1.3. Policy, Educational, and Professional Development Context

1.4. Literature Review (TJSS & MTSS & MTRS & MCIQ)

1.5. Well-Being (Psychological)

1.6. Job Satisfaction (Professional)

1.7. Self-Efficacy (Psychological)

1.8. Teacher’s Professional Identity (Aspiration, Motivation, Authority; Situational)

1.9. Music Curriculum Implementation (Environmental)

1.10. Resilience (Behavioural)

1.11. PERMA (Framework)

1.12. Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Research Toolkit

Multi-construct survey (TJSS & MTSS & MTR & MCIQ + PERMA)

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Data Collection

2.3.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Reliability, Validity, CFA, and EFA Analysis

3.2. Structural Equation Modelling & Path Analysis

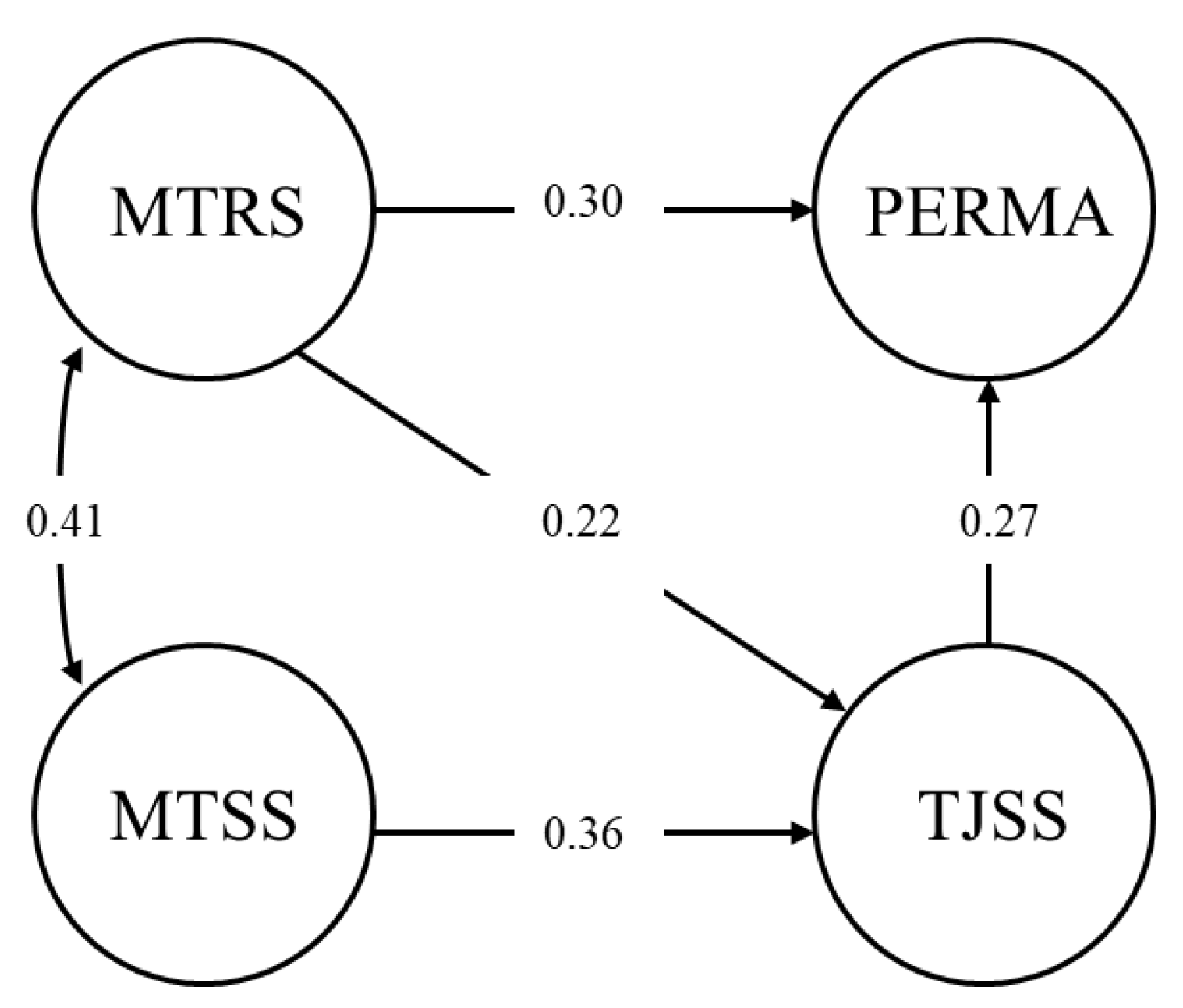

3.2.1. SEM1: Profiling Music Teachers’ Well-Being

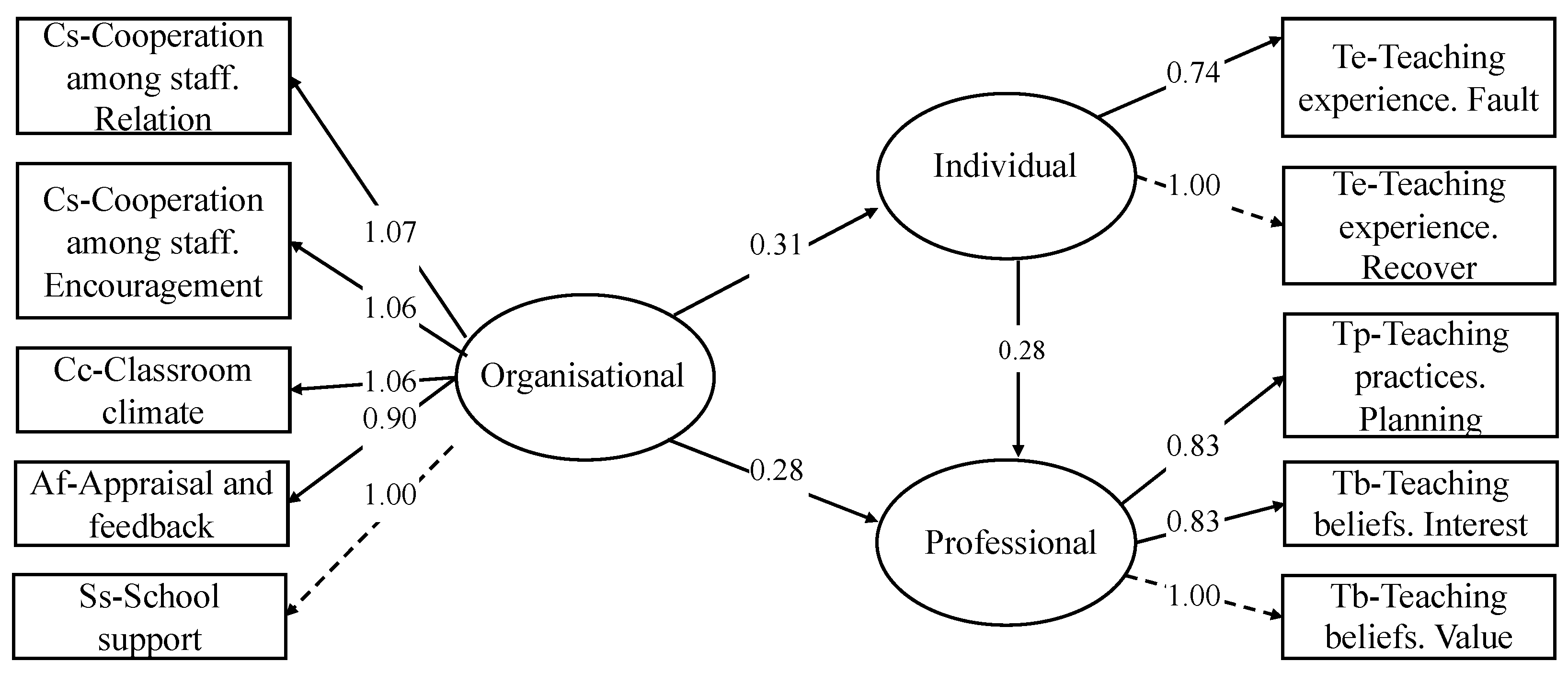

3.2.2. SEM2: Functional Model for Music Teachers’ Well-Being Development

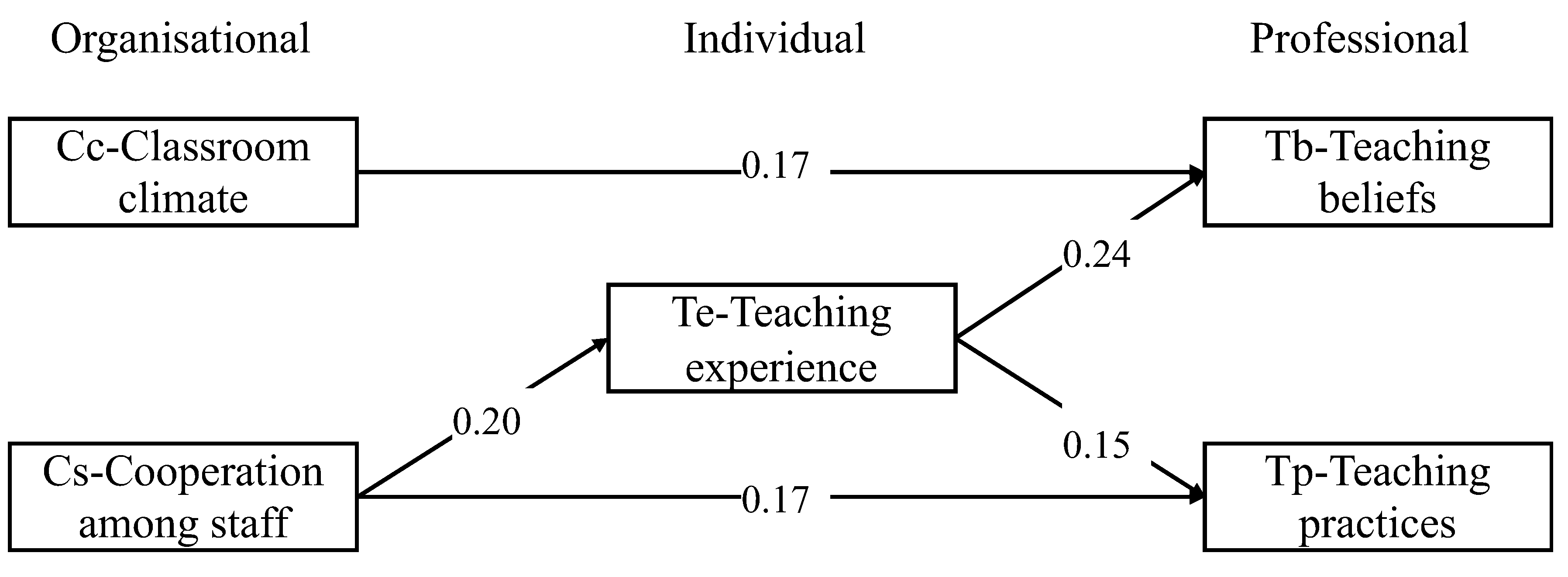

3.2.3. Path Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. RQ1: Individual Aspects

4.2. RQ2: Organizational Aspects

4.3. Interpersonal Relationships

- Professional Development and Collaboration: Provide access to external training and exchange programs while encouraging group cooperation among teachers to share resources and experiences.

- Recognition and Support: Regularly acknowledge outstanding performance and offer timely feedback, fostering a sense of achievement and belonging among teachers.

- Improved Working Conditions: Enhance the working environment with comfortable office spaces, necessary teaching resources, and reduce administrative workloads to allow teachers to focus on teaching.

- Transparent Evaluation and Mental Health Support: Establish clear evaluation mechanisms with transparent criteria and provide psychological counselling services to support teachers' mental health and help them cope with stress.

5. Conclusion

6. Limitations

References

- Aelterman, A.; Engels, N.; Van Petegem, K.; Pierre Verhaeghe, J. The well-being of teachers in Flanders: the importance of a supportive school culture. Educational studies 2007, 33, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J.J.; Christenson, S.L.; Kim, D.; Reschly, A.L. Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the Student Engagement Instrument. Journal of school psychology 2006, 44, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeline, V.R. Motivation, Professional Development, and the Experienced Music Teacher. Music Educators Journal 2014, 101, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, N.; Zhang, S.; Tian, G.; Zhu, X.; Kang, X. Exploring teacher well-being in educational reforms: A Chinese perspective. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 14, 1265536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auliah, A.; Thien, L.M.; Kho, S.H.; Abd Razak, N.; Jamil, H.; Ahmad, M.Z. Exploring positive school attributes: evidence from school leader and teacher perspectives. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211061572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, J.; Canham, N. Understanding music teachers’ perceptions of themselves and their work: An importance–confidence analysis. International Journal of Music Education 2022, 41, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B. Flow among music teachers and their students: The crossover of peak experiences. Journal of vocational behavior 2005, 66, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevene, P.; De Stasio, S.; Fiorilli, C. Well-being of schoolteachers in their work environment. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolat, Ö. Bolat, Ö. & Toytok, E.H. (2023) Exploring teacher’s professional identity in relationship to leadership: A latent profile analysis [Preprint]. [CrossRef]

- Butt, R.; Retallick, J. Professional well-being and learning: A study of administrator-teacher workplace relationships. The Journal of Educational Enquiry 2002, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. & Kern, M.L. (2015). The PERMA profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Kern Publications.

- Bonner, A.D. (2023). Special Education Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Resilience as Predictors of Well-being (Doctoral dissertation, Grand Canyon University).

- Botha, M.G. (2022). Challenges, rewards and coping strategies associated with teachers’ well-being in the 21st century (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria (South Africa)).

- Calik, M. 2013. “Effect of Technology-Embedded Scientific Inquiry on Senior Science Student Teachers’ Self-Efficacy.” Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education 9 (3): 223–232. [CrossRef]

- Cadima, J.; Guedes, C.; Grande, C.; Charalambous, V.; Agathokleous, A.; Vrasidas, C. ;... & Halamandaris, R. (2021). Literature review on early childhood teachers’ careers and professional development, teachers’ well-being (PERMA) and children’s socio-emotional support (SWPBS).

- Chen, F.X. “Persistence” or “escape” - qualitative study based on the investigation of rural teachers’ turnover intention. Advances in Education 2022, 12, 3575–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Reimaging teacher resilience for flourishing. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher.

- Dreer, B. Teachers’ well-being and job satisfaction: The important role of positive emotions in the workplace. Educational Studies 2024, 50, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Support. (2019). Teacher well-being index 2019. Education Support.

- Falk, D.; Shephard, D.; Mendenhall, M. “I always take their problem as mine”–understanding the relationship between teacher-student relationships and teacher well-being in crisis contexts. International Journal of Educational Development 2022, 95, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.; Gouveia, M.J.; Silva, J.C.; Peixoto, F. Positive education’: A professional learning programme to foster teachers’ resilience and well-being. Cultivating teacher resilience 2021, 103. [Google Scholar]

- García-Álvarez, D.; Soler, M.J.; Cobo-Rendón, R.; Hernández-Lalinde, J. Teacher professional development, character education, and well-being: multicomponent intervention based on positive psychology. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.; Wilcox, G.; Nordstokke, D. Teacher mental health, school climate, inclusive education and student learning: A review. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 2017, 58, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, T.; Mercer, S.; MacIntyre, P.; Talbot, K.; Banga, C.A. Understanding language teacher well-being: An ESM study of daily stressors and uplifts. Language Teaching Research 2023, 27, 862–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T.; Waber, J. Teacher well-being: A systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educational Research Review 2021, 34, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T.; Beltman, S.; Mansfield, C. Teacher well-being and resilience: Towards an integrative model. Educational research 2021, 63, 416–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T.; Waber, J. Teacher well-being: A systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educational research review 2021, 34, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W. Chinese English as a foreign language teachers’ job satisfaction, resilience, and their psychological well-being. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 12, 800417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy WK, Miskel CG (2010). Educational administration: theory, research and practice. (Trans. Ed. Turan S). Ankara: Nobel. (Original work published 1998).

- Hong, J.Y. (2010a) ‘Pre-service and beginning teachers’ professional identity and its relation to dropping out of the profession’, Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, pp. 1530–1543. /: http. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yin, H.; Lv, L. Job characteristics and teacher well-being: the mediation of teacher self-monitoring and teacher self-efficacy. Educational psychology 2019, 39, 313-331.Isbell, D.S. Musicians and Teachers: The Socialization and Occupational Identity of Preservice Music Teachers. Journal of Research in Music Education 2008, 56, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Yoo, H. Music Teachers’ Psychological Needs and Work Engagement as Predictors of Their Well-being. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 2019, 221, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.M.; and M., M. Chiu. 2010. “Effects on Teachers’ Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction: Teacher Gender, Years of Experience, and Job Stress.” Journal of Educational Psychology 102 (3): 741–756. [CrossRef]

- Kouhsari, M.; Chen, J.; Baniasad, S. Multilevel analysis of teacher professional well-being and its influential factors based on TALIS data. Research in Comparative and International Education 2023, 18, 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun, A.; Gadanecz, P. Workplace happiness, well-being and their relationship with psychological capital: A study of Hungarian Teachers. Current Psychology 2022, 41, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarides, R.; Warner, L.M. Teacher self-efficacy. Oxford research encyclopedia of education 2020, 1e22. [Google Scholar]

- Loerbroks, A.; Meng, H.; Chen, M.-L.; Herr, R.; Angerer, P.; Li, J. Primary school teachers in China: associations of organisational justice and effort–reward imbalance with burnout and intentions to leave the profession in a cross-sectional sample. International archives of occupational and environmental health 2014, 87, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, s. , & Teddlie, C. Case studies of educational effectiveness in rural China. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR) 2009, 14, 334–355. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Li, Z.; Tinmaz, H. The influence of professional identity and occupational well-being on retention intention of rural teachers in China. International Journal of Chinese Education 2024, 13, 2212585X241253918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luekens, M.T. (2004). Teacher attrition and mobility: Results from the teacher followup survey. 2000e01. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Dept. of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. E.D.

- Liu, L.B.; Song, H.; Miao, P. Navigating individual and collective notions of teacher well-being as a complex phenomenon shaped by national context. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 2018, 48, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Norman, S.; Combs, G. Psychological capital development: Toward a micro-intervention. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2006, 27, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avey, J.B.; Patera, J.L. (2008). Experimental analysis of a web-based intervention to develop positive psychological capita.

- McCallum, F.; Price, D. (2016). Nurturing well-being development in education: From little things, big things grow. London: Routledge.

- Mullen, C.A.; Shields, L.B.; Tienken, C.H. Developing teacher resilience and resilient school cultures. Journal of Scholarship & Practice 2021, 18, 8–24. [Google Scholar]

- Miksza, P.; Parkes, K.; Russell, J.A.; Bauer, W. The well-being of music educators during the pandemic Spring of 2020. Psychology of Music 2022, 50, 1152–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (2009). Creating effective teaching and learning environments: First results from TALIS, Paris: OECD Publication.

- Ortan, F.; Simut, C.; Simut, R. Self-efficacy, job satisfaction and teacher well-being in the K-12 educational system. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 12763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Baumeister, R.F. Meaning in life and adjustment to daily stressors. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2017, 12, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretsch, J.; Flunger, B.; Schmitt, M. Resilience predicts well-being in teachers, but not in non-teaching employees. Social Psychology of Education 2012, 15, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qianli, L. Occupational Environment, Professional Development, and Well-being of High School Teachers in China. Sustainable Development 2024, 12, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Reppa, P.G. and Gournelou, P. (2012) ‘The professional identity of primary and secondary school music teachers in Greece’, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, pp. 2611–2614. [CrossRef]

- Richards, K.A. R.; Levesque-Bristol, C.; Templin, T.J.; and Graber, K. The impact of resilience on role stressors and burnout in elementary and secondary teachers. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 19 2016, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, D.L.; Koomen, H.M.; Spilt, J.L.; Oort, F.J. The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of educational research 2011, 81, 493–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2018, 13, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman M. E., P.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive Psychology: An introduction. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/. [CrossRef]

- Seligman M. E., P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

- Song, H.; Lin, M.; Ou, Y.; Wang, X. Reframing teacher well-being: A case study and a holistic exploration through a Chinese lens. Teachers and Teaching 2024, 30, 818–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J. Higher education teachers’ professional well-being in the rise of managerialism: Insights from China. Higher Education 2024, 87, 1121–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M.; and, S. Skaalvik. 2011. “Teachers’ Feeling of Belonging, Exhaustion, and Job Satisfaction: The Role of School Goal Structure and Value Consonance.” Anxiety, Stress, and Coping 24 (4): 369–385. [CrossRef]

- Trent, J. Wither teacher professional development? The challenges of learning teaching and constructing identities across boundaries in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Education 2020, 40, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.; Theilking, M. Teacher well-being: Its effects on teaching practice and student learning. Issues in Educational Research 2019, 29, 938–960. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, K.; Thielking, M.; Prochazka, N. Teacher well-being and social support: A phenomenological study. Educational Research 2022, 64, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tickle, B.R.; Chang, M.; Kim, S. Administrative support and its mediating effect on US public school teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education 2011, 27, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.; Thielking, M.; Meyer, D. Teacher well-being, teaching practice and student learning. Issues in Educational research 2021, 31, 1293–1311. [Google Scholar]

- Wagoner, C.L. Measuring music teacher identity: Self-efficacy and commitment among music teachers. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, (205).

- Yang, Y. Professional identity development of preservice music teachers: A survey study of three Chinese universities. Research Studies in Music Education 2022, 44, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Challenges in teachers’ professional identity development under the national teacher training programme: An exploratory study of seven major cities in Mainland China. Music Education Research 2023, 25, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, K. Main factors of teachers professional well-being. Educational Research and Reviews 2014, 9, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Yan, Z. Trajectory of Teacher Well-being Research between 1973 and 2021: Review Evidence from 49 Years in Asia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 12342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reliability | Fit Measures | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSEA 90% CI | ||||||||

| Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | Lower | Upper | |

| TJSS | 0.941 | 0.942 | 0.994 | 0.979 | 0.0131 | 0.0503 | 0.0238 | 0.0763 |

| MTSS | 0.893 | 0.894 | 0.992 | 0.984 | 0.0161 | 0.0507 | 0.0218 | 0.0789 |

| MTRS | 0.930 | 0.930 | 0.990 | 0.981 | 0.0181 | 0.0546 | 0.0311 | 0.0784 |

| MCIQ* | 0.821 | 0.833 | 0.988 | 0.975 | 0.0265 | 0.0490 | 0.0176 | 0.0788 |

| PERMA | 0.937 | 0.937 | 0.993 | 0.985 | 0.0147 | 0.0479 | 0.0242 | 0.0709 |

| SEM | EFA Factors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Path | Items codes by subscales | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Uniqueness |

| O-Ss | TJSS_SS / MCIQ_S.Helping | 0.797 | 0.395 | |||||

| * | O-Cs | TJSS_RC.Encouragement | 0.776 | 0.391 | ||||

| * | O-Af | TJSS_SS.Supervising | 0.769 | 0.381 | ||||

| P-Pda | TJSS_PD.Training | 0.764 | 0.430 | |||||

| * | P-Pda | TJSS_PD / MCIQ_S.Support | 0.739 | 0.469 | ||||

| I-Emp | TJSS_RM.Income | 0.737 | 0.491 | |||||

| O-Cc | TJSS_RE.Resource | 0.731 | 0.432 | |||||

| * | O-Wl | TJSS_WL.Workload | 0.723 | 0.452 | ||||

| * | O-Cs | * | TJSS_RC.Relation | 0.718 | 0.409 | |||

| O-Cc | TJSS_RS.Respect | 0.718 | 0.435 | |||||

| O-Af | TJSS_RC.Recognition | 0.710 | 0.450 | |||||

| * | O-Ss | TJSS_RE.Equipment | 0.710 | 0.482 | ||||

| I-Emp | TJSS_RM.Financing | 0.692 | 0.471 | |||||

| P-Tp | TJSS_WI / MCIQ_K.Skill | 0.679 | 0.499 | |||||

| O-Cc | TJSS_RS.StRelation | 0.678 | 0.427 | |||||

| * | O-Sc | TJSS_WC.Improvement | 0.677 | 0.634 | ||||

| * | P-Tp | TJSS_WI / MCIQ_S.Opportunity | 0.673 | 0.517 | ||||

| * | P-Tp | TJSS_TA / MCIQ_K.Autonomy | 0.673 | 0.486 | ||||

| O-Wl | TJSS_WL.Admin | 0.645 | 0.646 | |||||

| * | * | MTRS_E.Calm | 0.869 | 0.295 | ||||

| * | MTRS_S.Understanding | 0.831 | 0.341 | |||||

| * | MTRS_E.Growth | 0.816 | 0.359 | |||||

| * | MTRS_P / MCIQ_M.Scheduling | 0.796 | 0.328 | |||||

| P-Tp | MTRS_M.Improve | 0.794 | 0.329 | |||||

| P-Tb | MTRS_M.Expectation | 0.772 | 0.408 | |||||

| * | I-Te | MTRS_M.Fault | 0.765 | 0.392 | ||||

| P-Tb | MTRS_M.Confident | 0.756 | 0.371 | |||||

| I-Te | MTRS_E.Recover | 0.755 | 0.466 | |||||

| P-Tp | * | MTRS_M.Challenge | 0.753 | 0.458 | ||||

| P-Tp | * | MTRS_P.Reflection | 0.746 | 0.381 | ||||

| P-Tp | MTRS_P.Flexibility | 0.713 | 0.412 | |||||

| * | * | MTRS_M.Target | 0.709 | 0.395 | ||||

| P-Tp | PERMA_E.Concentrate | 0.853 | 0.304 | |||||

| P-Tb | * | PERMA_M.Value | 0.828 | 0.334 | ||||

| O-Cs | PERMA_R.Satisfaction | 0.820 | 0.350 | |||||

| * | O-Cs | MCIQ_S / PERMA_R.PeerSupport | 0.819 | 0.304 | ||||

| P-Tp | * | PERMA_M.Planning | 0.816 | 0.410 | ||||

| P-Tb | PERMA_A.Goals | 0.783 | 0.369 | |||||

| P-Tb | PERMA_E.Interest | 0.775 | 0.358 | |||||

| O-Cs | PERMA_R.Prease | 0.771 | 0.367 | |||||

| * | PERMA_P.Happiness | 0.764 | 0.409 | |||||

| * | PERMA_P.Positive | 0.756 | 0.376 | |||||

| P-Tb | * | MTSS_AB / MCIQ_A.Confidence | 0.894 | 0.275 | ||||

| * | P-Tp | * | MTSS_AB.Objectives | 0.825 | 0.333 | |||

| P-Tp | * | TJSS_TA / MTSS_PS.Innoviation | 0.813 | 0.370 | ||||

| * | MTSS_AB.Competance | 0.788 | 0.380 | |||||

| * | MTSS_AB.Participation | 0.772 | 0.366 | |||||

| * | MTSS_AB.LifeValue | 0.707 | 0.434 | |||||

| * | MTSS_AC.Activity | 0.660 | 0.538 | |||||

| * | * | * | MTSS_PV.StSuccess | 0.322 | 0.389 | 0.620 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).