1. Introduction

This study aims to use the segment-geospatial (samgeo), an advanced AI-based segmentation model, to identify and delineate areas of flood water within the orthomosaic imagery captured by a drone. The samgeo package leverages the Segment Anything Model (SAM) developed by Meta AI. A state-of-the-art, general image segmentation model, SAM is capable of segmenting unfamiliar objects and images without requiring additional training [

1,

2]. Considered a crucial task in computer vision, image segmentation plays an important role in a range of applications, including object recognition, tracking, and detection, medical imaging, and robotics [

3]. The goal of image segmentation is to partition an image into distinct and interpretable regions or objects [

1]. Here, samgeo is applied in segmenting a drone imagery to detect flood water at Kachulu, Lake Chilwa Basin, in the aftermath of Tropical Cyclone Freddy. In March 2023, Tropical Cyclone Freddy brought heavy rains to the region, resulting in lakeshore flooding at Kachulu Trading Centre as rising lake waters were pushed further inland [

4]. Consequently, houses and croplands proximal to the lake were submerged. A sensitive and vulnerable basin to climate change, Lake Chilwa and its surrounding wetlands play an important role in agricultural, fish production and biodiversity conservation [

5]. Designated as a wetland of importance (RAMSAR site No. 869) in 1997, the Lake Chilwa Wetland provides habitats for a wide diversity of birdlife, fish and other flora and fauna, and fertile arable lands for irrigated rice, maize and dimba cultivation [

5,

6]. However, increasing intensity and occurrence of floods and other extreme weather events are challenging agriculture, fishery and biodiversity conservation. For example, in recent decades, a reduction in annual precipitation alongside extreme weather events such as droughts has been observed across the basin [

5].

In this work, the following research questions are addressed: 1. is flood water at Kachulu detectable in a multispectral drone imagery? 2. Can the use of a pre-trained AI model be implemented to segment and delineate flood water within Lake Chilwa Basin? The novelty of this study is that it demonstrates, for the first time, the ability of samgeo to achieve high levels of accuracy in detecting flood water at Kachulu. By leveraging the capabilities of AI, this study seeks to demonstrate the accuracy, efficiency, and automation of flood water extraction tasks from drone imagery using the samgeo. This approach holds potential for upscaling and mainstreaming the application of AI for rapid flood monitoring and response efforts at Kachulu and across similar contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Contextualization

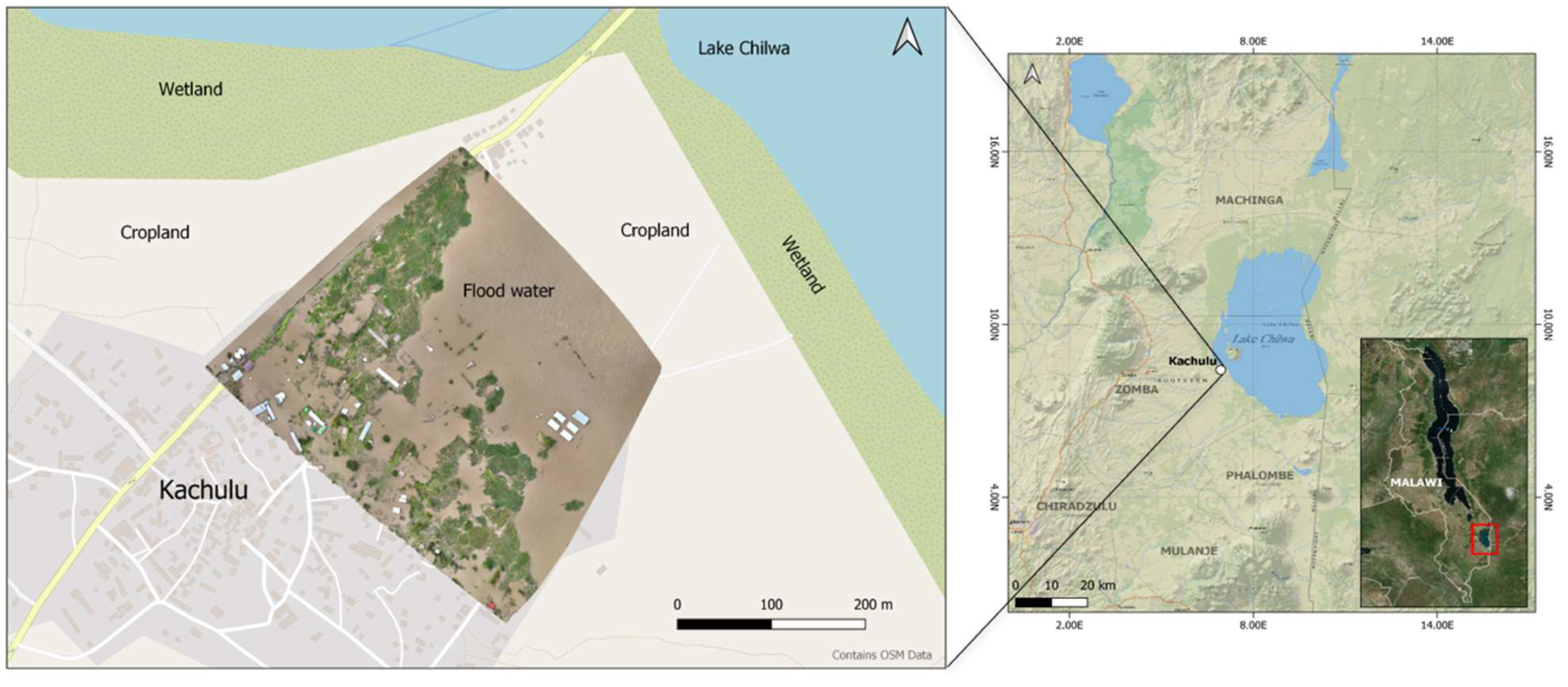

The study area is Kachulu Trading Centre (South: 15.3742984, East: 35.5860822, Elevation: ~627m), situated along the shores of Lake Chilwa in southern Malawi (

Figure 1). Lake Chilwa plays a significant role in the local ecosystem and supports various ecological functions. It serves as a habitat for numerous species of plants and animals, including a diverse range of fish species [

6]. The lake’s shallow nature makes it highly productive, fostering the growth of aquatic vegetation and providing an abundant food source for both resident and migratory bird populations. The lake’s hydrology is influenced by both rainfall and inflow from surrounding rivers. During periods of heavy rainfall, Lake Chilwa experiences significant expansion as it has no output, while prolonged dry spells can lead to a decrease in water levels [

5]. This fluctuation in water levels has a direct impact on the lake’s ecology and the livelihoods of communities residing in its vicinity. Additionally, Lake Chilwa is susceptible to climate change impacts, including changes in precipitation patterns and increased frequency of droughts. These changes can further exacerbate water level fluctuations and pose risks to both the lake’s ecosystem and the livelihoods of local communities dependent on its resources.

2.2. Drone Data

In response to the flood situation at Kachulu, the Leadership for Environment and Development (LEAD, Zomba) obtained MSI drone images on 05 April 2023, using a small commercial-grade drone, Mavic 3 (DJI Shenzen, China). The drone images were combined to create an orthomosaic with a spatial resolution of 2 x 2m in WebODM (OpenDroneMap).

2.3. Image Segmentation

This study employs samgeo, an open-source Python package for segmenting remotely sensed imagery using the SAM [

7]. SAM, a state-of-the-art deep learning model, is trained on an extensive dataset comprising 11 million images and 1.1 billion masks [

2]. The model excels at instance-level semantic segmentation, which identifies and isolates individual objects within an image. SAM operates through a two-stage framework: an initial proposal generation phase followed by a refinement phase.

In the first stage, SAM uses a fully convolutional network (FCN) to generate preliminary object proposals. FCNs are neural networks optimized for dense prediction tasks like semantic segmentation [

8,

9]. These networks process the input image to produce masks or bounding boxes that potentially contain objects of interest. To account for objects of varying sizes and shapes, the bounding boxes are generated at multiple scales and aspect ratios. During training, the FCN learns to estimate the likelihood that each pixel belongs to an object, which informs the generation of initial object proposals.

In the second refinement stage, SAM improves these preliminary object proposals by combining deep feature extraction and spatial information. It utilizes a region-based fully convolutional network (R-FCN) to capture high-level semantic details from each proposed region. These deep features provide a more nuanced understanding of the objects within the proposals, enabling SAM to deliver precise segmentation results.

The present study utilizes Python 3 in Google Collab to undertake the segmentation using the samgeo model. All the work on the computer was carried out using a Desktop computer with 64 GB RAM and 3.7 GHz processor.

2.4. Image Segmentation

For comparison, a supervised (i.e., human-assisted) machine learning method using the geospatial object-based image analysis (GEOBIA) approach in QGIS 3.22.1 and Orfeo ToolBox (OTB) 7.1.0 was employed. The Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm was used to segment the flood water, serving as the ground truth for performance evaluation. For the purposes of this study, only flood water was delineated and exported as a shapefile. The supervised GEOBIA involved the selection of training areas and classification using the SVM algorithm.

2.5. Performance Evaluation of Samgeo

To assess the performance of the samgeo model, we employed the Intersection over Union (IoU) metric, also known as the Jaccard Index. The IoU is a widely used method for evaluating the accuracy of image segmentation models and is calculated as the ratio of the area of overlap (intersection) between the predicted segmentation mask and the ground truth mask to the area of their combined space (union) [

10]. This is expressed mathematically as:

Where:

A represents the predicted segmentation mask generated by the AI model, in this case the predicted flood water mask. B represents the ground truth mask, in this case the flood water extent provided by human-supervised segmentation.

The IoU value ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating a perfect match between the predicted and actual segmentation [

10]. Here, a higher IoU value would indicate that the samgeo model has accurately segmented flood water, suggesting better model performance.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Flood Water Segmentation

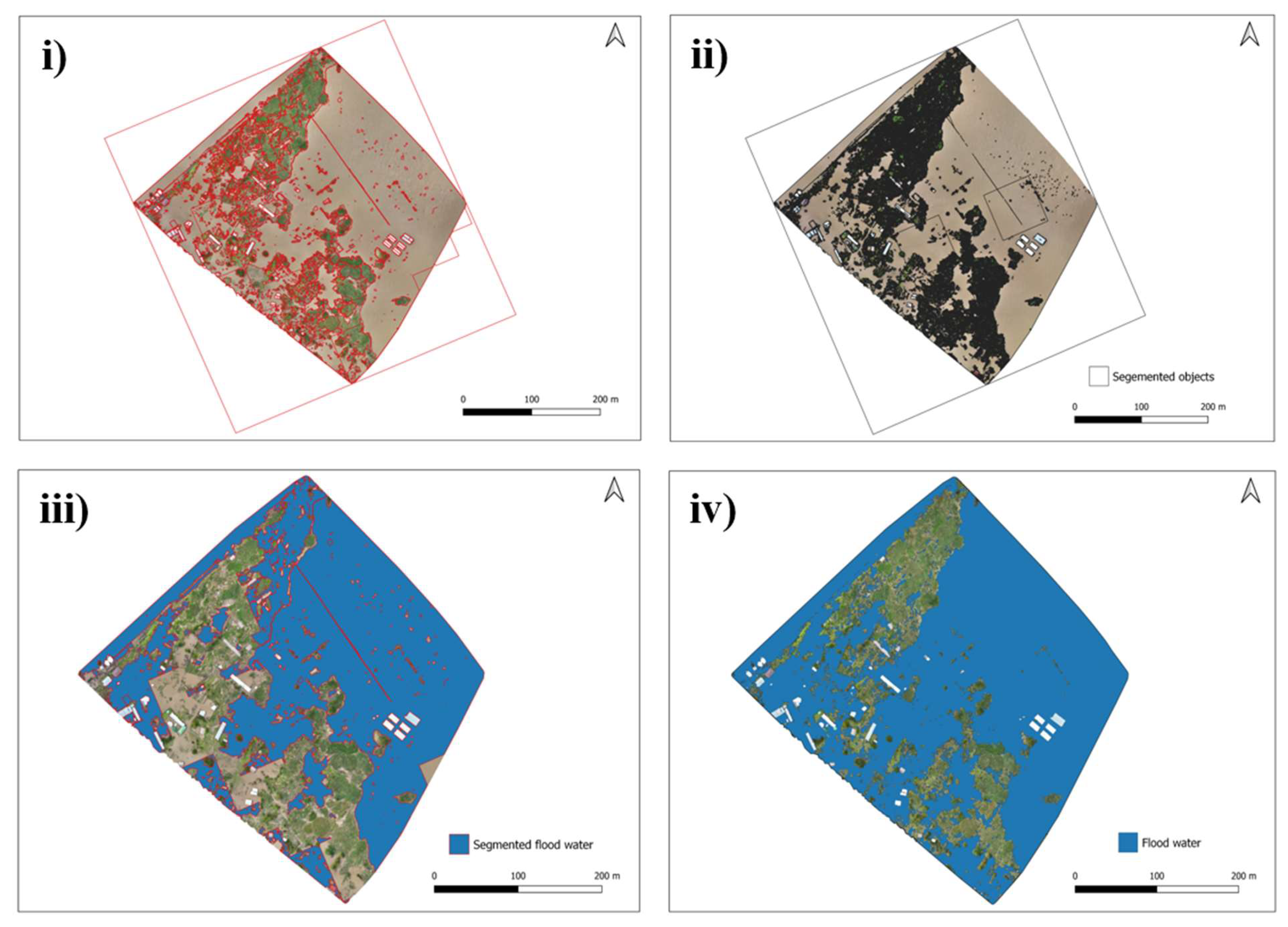

The segmentation results are illustrated in

Table 1. The results reveal that the samgeo model effectively segmented flood water, including vegetation and built structures (buildings). Furthermore, the flood water extents extracted by both segmentation methods were quantified. The AI-based model detected a flood water extent of 80,276 sq.m, while the human-assisted method identified and delineated 95,399 sq.m. This indicates that the samgeo model was able to detect and delineate approximately 84.1% of the total flood water extent identified by OTB model. The IoU metric was calculated to be 72.8%, indicating substantial overlap in the areas detected.

The results, as shown in

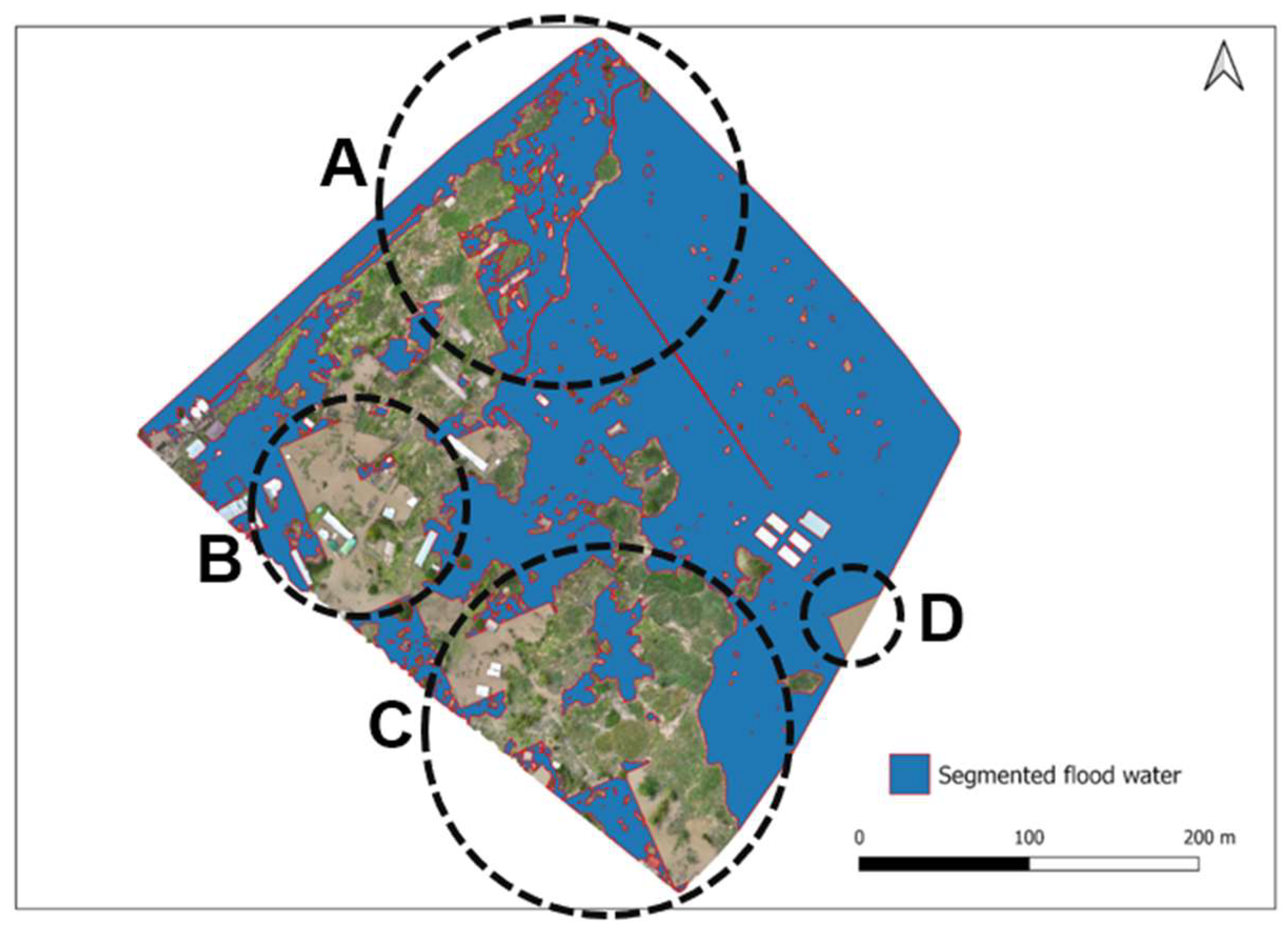

Figure 2, highlight the efficacy of samgeo in flood water detection, achieving a substantial accuracy without the need for extensive new training samples. However, the differences in extracted areas suggest that while samgeo performs well, there is certainly potential for improvement in detecting flood water in mosaic landscapes. A closer examination of samgeo output (

Figure 3) indicates that mis-segmentaion occurred: vegetation mis-segmented as water (A). In addition, samgeo could not fully detect and delineate water (B, C and D). The AI model’s ability to approximate human-assisted segmentation methods underscores its viability as an alternative approach for flood extent mapping, which can be particularly beneficial in scenarios where timely data analysis is crucial.

5. Conclusions

This study underscores the utility of AI-assisted segmentation in large-scale geospatial analysis and its potential to complement or replace traditional methods in flood mapping. The results of this study indicate that the AI demonstrates capability in identifying key land cover features within high-resolution drone imagery, particularly in delineating flood water extent. These results add to the rapidly expanding field of geospatial AI applications, particularly in automated disaster management and environmental monitoring. The contribution of this study has been to confirm the potential of AI-assisted segmentation to provide a reliable, time-efficient alternative to traditional human-supervised methods, especially for large-scale and near real-time flood mapping.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CN., P.L. and S.C.; methodology, C.N.; software, C.N.; validation, C.N.; formal analysis, C.N.; investigation, C.N.; resources, C.N., P.L., S.C.; data curation, C.N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.N.; writing—review and editing, C.N.; P.L.; S.C.; visualization, C.N.; supervision, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The data collection was funded by Leadership for Environment and Development (LEAD).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author ethical restrictions, a statement is still required.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Kachulu fishing community for supporting the drone data collection at Kachulu Trading Centre. C.N also thank the African Drone and Data Academy (ADDA) for providing drone training.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SAM |

Segment Anything Model |

| samgeo |

Geospatial segment anything model |

| OTB |

Orfeo Tool Box |

| GEOBIA |

Geospatial Object-Based Image Analysis |

| IoU |

Intersection over Union |

References

- Zhao, Z.; Fan, C.; Liu, L. Geo SAM: A QGIS Plugin Using Segment Anything Model (SAM) to Accelerate Geospatial Image Segmentation 2023.

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.-Y.; et al. Segment Anything 2023.

- Abdulateef, S.; Salman, M. A Comprehensive Review of Image Segmentation Techniques. Iraqi J. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2021, 17, 166–175. [CrossRef]

- WMO Tropical Cyclone Freddy May Set New Record 2023.

- Chiotha, S.S.; Likongwe, P.J.; Sagona, W.; Mphepo, G.Y.; Likoswe, M.; Tsirizeni, M.D.; Chijere, A.; Mwanza, P. Lake Chilwa Basin Climate Change Adaptation Programme: Impact 2010 – 2017 2017.

- WorldFish Centre The Structure and Margins of the Lake Chilwa Fisheries in Malawi: A Value Chain Analysis 2012.

- Wu, Q.; Osco, L.P. Samgeo: A Python Package for Segmenting Geospatial Datawith the Segment Anything Model (SAM). J. Open Source Softw. 2023, 8, 5663. [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Li, Y.; He, K.; Sun, J. R-FCN: Object Detection via Region-Based Fully Convolutional Networks 2016.

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Boston, MA, USA, June 2015; pp. 3431–3440.

- Shi, R.; Ngan, K.N.; Li, S. Jaccard Index Compensation for Object Segmentation Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP); IEEE: Paris, France, October 2014; pp. 4457–4461.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).