Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Aims

Primary

Secondary

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Sample and Criteria

2.4. Endpoints

- Sensor Glucose (SG) mean, Standard Deviation (SD), and Coefficient of Variation (CV);

- Time Below Range level 2 (TBR2): percentage of time spent below 54 mg/dL;

- Time Below Range level 1 (TBR1): percentage of time spent between 54-69 mg/dL;

- Time Below Range (TBR): percentage of time spent below 70 mg/dL;

- Time In Range (TIR): percentage of time spent within 70-180 mg/dL;

- Time Above Range level 1 (TAR1): percentage of time spent between 181-250 mg/dL;

- Time Above Range level 2 (TAR2): percentage of time spent above 250 mg/dL;

- Time Above Range (TAR): percentage of time spent above 180 mg/dL.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.5.1. General Methodology

2.5.2. Data Analysis

2.5.3. Derived Variables

2.5.4. Bedtime Hours

2.5.5. Handling of Missing Data and Outliers and Validation Requirements

3. Results

3.1. Patient Disposition

3.2. Sleep Quality

3.3. Patient Characteristics

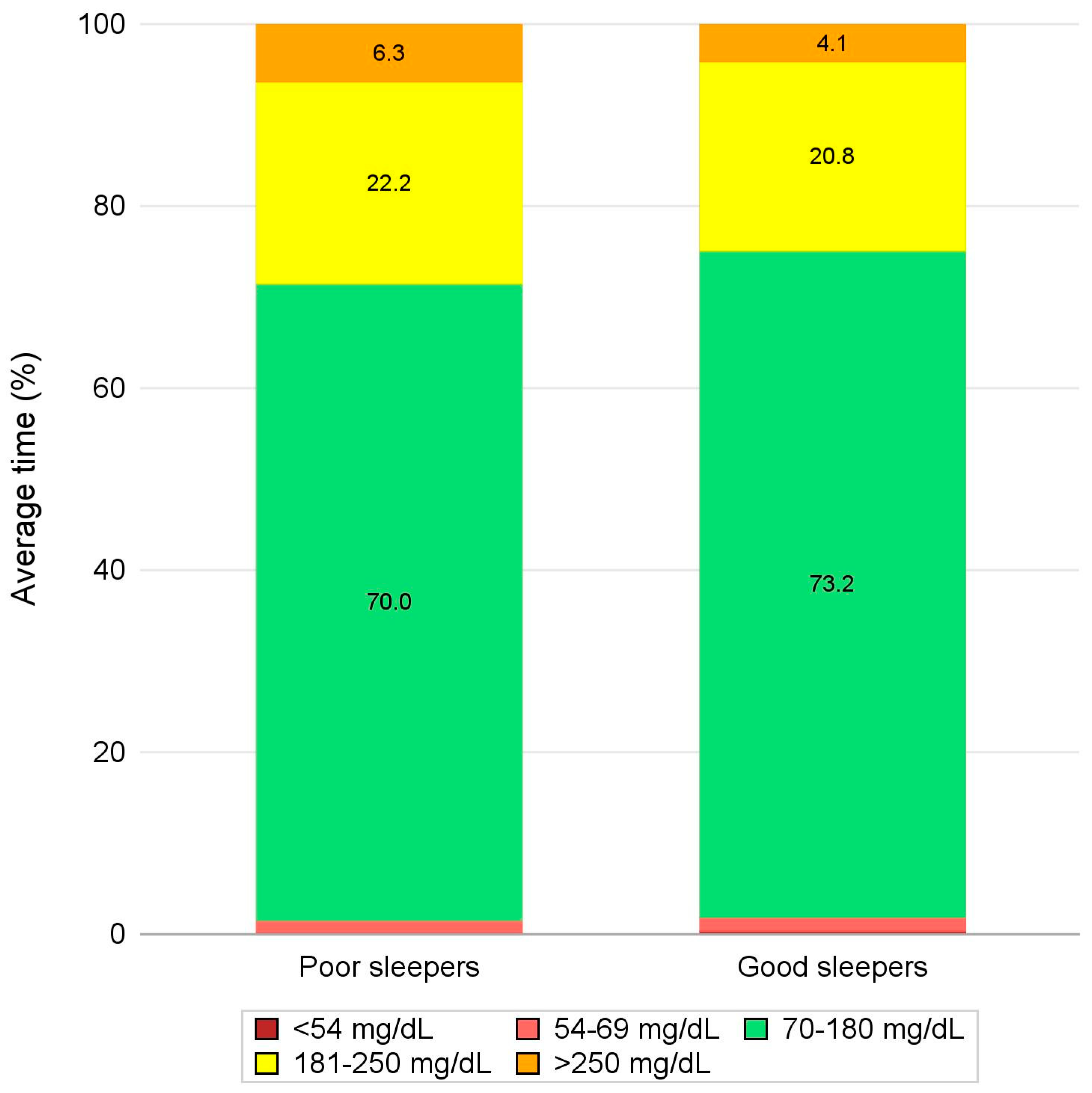

3.4. Glycemic Outcomes

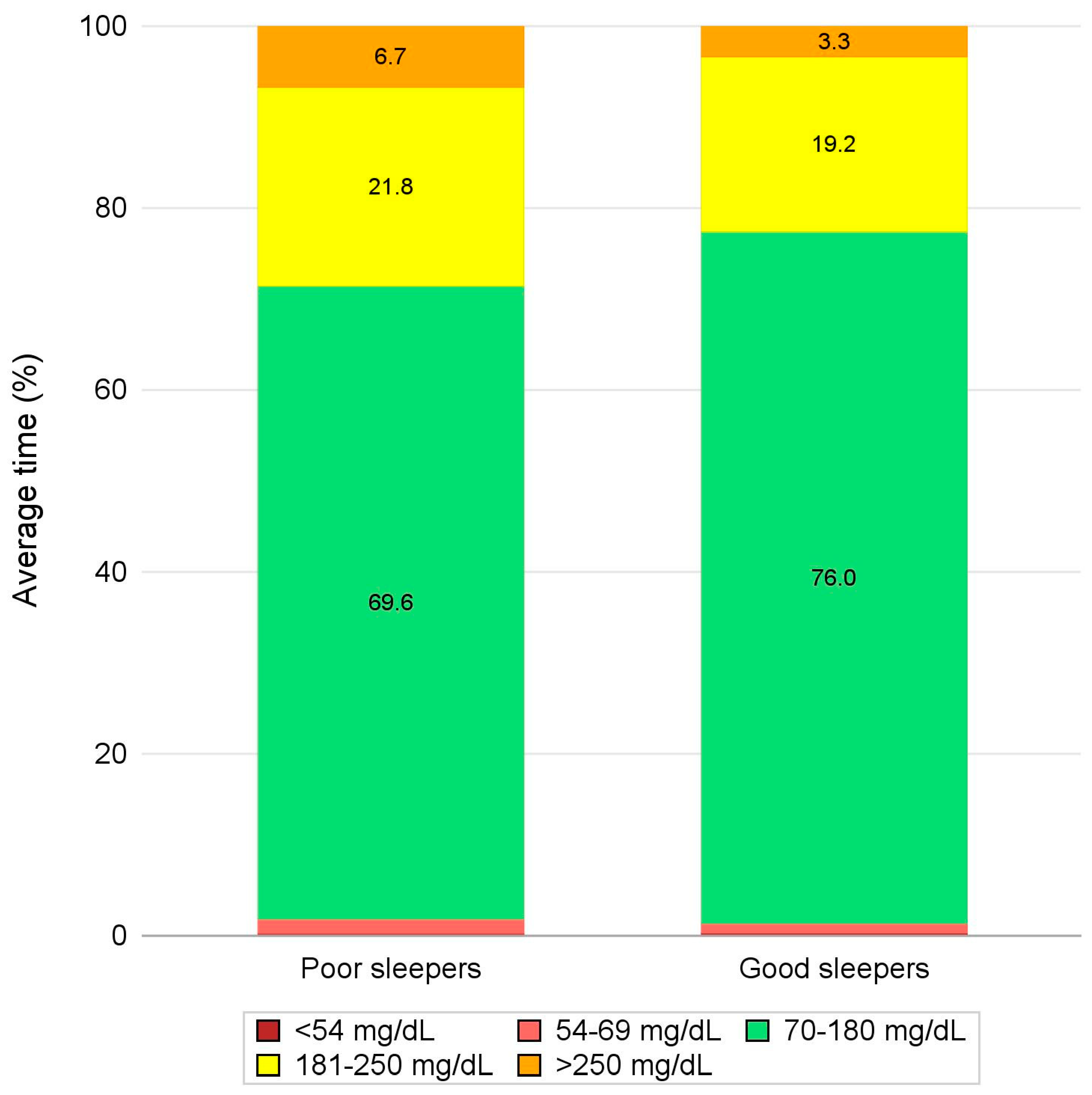

3.5. Glycemic Outcomes during Bedtime Hours

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmad, E.; Lim, S.; Lamptey, R.; Webb, D.R.; Davies, M.J. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2022, 400, 1803–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J. Committee IDFDAtes. IDF diabetes atlas. In Idf Diabetes Atlas; International Diabetes Feeration ©: Brussels, Belgium, Volume 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, N.D.; Sattar, N. Cardiovascular risk in diabetes mellitus: Epidemiology, assessment and prevention. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Diabetes. Available on: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (access ). 25 November.

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Results. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Available on: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (access on , 2024). 1 November.

- GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2023, 402, 203–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrelli, F.; Cangelosi, G.; Scuri, S.; Nguyen, C.T.T.; Debernardi, G.; Benni, A.; et al. Conoscenze alimentari in pazienti afferenti ad un centro di diabetologia [Food knowledge of patients at the first access to a Diabetology center]. Acta Biomed, 2020, 91(3-S), 160-164. [CrossRef]

- Cangelosi, G.; Grappasonni, I.; Nguyen, C.T.T.; Acito, M.; Pantanett,i P. ; Benni, A.; Petrelli, F. Mediterranean Diet (MedDiet) and Lifestyle Medicine (LM) for support and care of patients with type II diabetes in the COVID-19 era: a cross-observational study. Acta Biomed. 2023, 94, e2023189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangelosi, G.; Acito, M.; Grappasonni, I.; Nguyen, C.T.T.; Tesauro, M.; Pantanetti, P.; et al. Yoga or Mindfulness on Diabetes: Scoping Review for Theoretical Experimental Framework. Ann Ig. 2024, 36, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen LM, Sherr JL, Considine E, Chen A, Peeling SM, Hulsmans M, Charleer S, Urazbayeva M, Tosur M, Alamarie S, Redondo MJ, Hood KK, Gottlieb PA, Gillard P, Wong JJ, Hirsch IB, Pratley RE, Laffel LM, Mathieu C; ADA/EASD PMDI. Utility and precision evidence of technology in the treatment of type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Commun Med, 2023; 3, 132. [CrossRef]

- Mallik R, Kar P, Mulder H, Krook A. The future is here: an overview of technology in diabetes. Diabetologia, 2019; ;67. [CrossRef]

- Handelsman Y, Hellman R, Lajara R, Roberts VL, Rodbard D, Stec C, Unger J. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: The Use of Advanced Technology in the Management of Persons With Diabetes Mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2021, 27, 505–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 7. Diabetes Technology: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, Jan 1;47(Suppl 1):S126-S144. [CrossRef]

- Cangelosi, G.; Mancin, S.; Morales Palomares, S.; Pantanetti, P.; Quinzi, E.; Debernardi, G.; Petrelli, F. Impact of School Nurse on Managing Pediatric Type 1 Diabetes with Technological Devices Support: A Systematic Review. Diseases. 2024, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayedi, A.; Zargar, M.S.; Emadi, A.; Aune, D. Walking speed and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2024, 58, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; An, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Global epidemiology of type 2 diabetes in patients with NAFLD or MAFLD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, G.A.; Robinson, T.I.G.; Linklater, S.E.; Wang, F.; Colagiuri, S.; de Beaufort, C.; Donaghue, K.C.; International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas Type 1 Diabetes in Adults Special Interest Group; et al. Global incidence, prevalence, and mortality of type 1 diabetes in 2021 with projection to 2040: a modelling study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 741–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anandhakrishnan, A.; Hussain, S. Automating insulin delivery through pump and continuous glucose monitoring connectivity: Maximizing opportunities to improve outcomes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhat, I.; Drishti, S.; Bochner, R.; Bargman, R. Do hybrid closed loop insulin pump systems improve glycemic control and reduce hospitalizations in poorly controlled type 1 diabetes? J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, F.; Cangelosi, G.; Scuri, S.; Pantanetti, P.; Lavorgna, F.; Faldetta, F.; et al. Diabetes and technology: A pilot study on the management of patients with insulin pumps during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020, 169, 108481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovski, G.; Al Khalaf, F.; Campbell, J.; Umer, F.; Almajaly, D.; Hamdan, M.; Hussain, K. One-year experience of hybrid closed-loop system in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes previously treated with multiple daily injections: drivers to successful outcomes. Acta Diabetol. 2021, 58, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, S.A.; Lee, M.H.; Paldus, B.; Vogrin, S.; de Bock, M.I.; Abraham, M.B.; et al.; Australian JDRF Closed-Loop Research Group Six Months of Hybrid Closed-Loop Versus Manual Insulin Delivery With Fingerprick Blood Glucose Monitoring in Adults With Type 1 Diabetes: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care. 2020, 43, 3024–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobry, E.C.; Kanapka, L.G.; Cengiz, E.; Carria, L.; Ekhlaspour, L.; Buckingham, B.A.; et al.; iDCL Trial Research Group Health-Related Quality of Life and Treatment Satisfaction in Parents and Children with Type 1 Diabetes Using Closed-Loop Control. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2021, 23, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benioudakis, E.; Karlafti, E.; Kalaitzaki, A.; Kaiafa, G.; Savopoulos, C.; Didangelos, T. Technological Developments and Quality of Life in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Patients: A Review of the Modern Insulin Analogues, Continuous Glucose Monitoring and Insulin Pump Therapy. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2022, 18, e031121197657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Service (NHS) Digital. National Diabetes Audit 2021-22, type 1 Diabetes – overview. Available on: https://digital. nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/national-diabetes-audit-type-1-diabetes/nda-type-1-2021-22-overview (accessed ). 24 November.

- Foster, N.C.; Beck, R.W.; Miller, K.M.; Clements, M.A.; Rickels, M.R.; DiMeglio, L.A.; et al. State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016-2018. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019, 21, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejera-Pérez, C.; Chico, A.; Azriel-Mira, S.; Lardiés-Sánchez, B.; Gomez-Peralta, F.; Área de Diabetes-SEEN. Connected Insulin Pens and Caps: An Expert's Recommendation from the Area of Diabetes of the Spanish Endocrinology and Nutrition Society (SEEN). Diabetes Ther. 2023, 14, 1077–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimri, R.; Nir, J.; Phillip, M. Insulin Pump Therapy. Am J Ther. 2020, 27, e30–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cernea, S.; Raz, I. Insulin Therapy: Future Perspectives. Am J Ther. 2020, 27, e121–e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Trawley, S.; Kubilay, E.; Mohammad Alipoor, A.; Vogrin, S.; Fourlanos, S.; et al. Closed-Loop Insulin Delivery Effects on Glycemia During Sleep and Sleep Quality in Older Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: Results from the ORACL Trial. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2022, 24, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobry, E.C.; Karami, A.J.; Meltzer, L.J. Friend or Foe: a Narrative Review of the Impact of Diabetes Technology on Sleep. Curr Diab Rep. 2022, 22, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, R.; Park, M.; Wroblewski, K.; Quinn, L.; Tasali, E.; Cinar, A. Sleep quality and glycaemic variability in a real-life setting in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2021, 64, 2159–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Irsheed, G.; Martyn-Nemeth, P.; Baron, K.G.; Reutrakul, S. Sleep Disturbances in Type 1 Diabetes and Mitigating Cardiovascular Risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024, 109, 3011–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilliard, M.E.; Levy, W.; Anderson, B.J.; Whitehouse, A.L.; Commissariat, P.V.; Harrington, K.R.; et al. Benefits and Barriers of Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Young Children with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019, 21, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaser, S.S.; Foster, N.C.; Nelson, B.A.; Kittelsrud, J.M.; DiMeglio, L.A.; Quinn, M.; Willi, S.M.; Simmons, J.H. T1D Exchange Clinic Network. Sleep in children with type 1 diabetes and their parents in the T1D Exchange. Sleep Med. 2017, 39, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sguanci, M.; Mancin, S.; Gazzelloni, A.; Diamanti, O.; Ferrara, G.; Morales Palomares, S.; Parozzi, M.; Petrelli, F.; Cangelosi, G. The Internet of Things in the Nutritional Management of Patients with Chronic Neurological Cognitive Impairment: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcio, G.; Tempesta, D.; Scarlata, S.; Marzano, C.; Moroni, F.; Rossini, P.M.; Ferrara, M.; De Gennaro, L. Validity of the Italian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Neurol Sci. 2013, 34, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medtronic. Care link report. Available on: https://www.medtronicdiabetes.com/customer-support/carelink-software-support/ carelink-reports (access ). 30 November.

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019, 13 (Suppl 1), S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelino T, Danne T, Bergenstal RM, et al. Clinical Targets for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data Interpretation: Recommendations From the International Consensus on Time in Range. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1593-1603. [CrossRef]

- Passanisi S, Lombardo F, Mameli C, Bombaci B, Macedoni M, Zuccotti G, Dovc K, Battelino T, Salzano G, and Delvecchio M. Safety, Metabolic and Psychological Outcomes of Medtronic MiniMed 780GTM in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Brandt R, Park M, Wroblewski K, Quinn L, Tasali E, and Cinar A. Sleep Quality and Glycaemic Variability in a Real-Life Setting in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetologia. 2021; 64: (10):, 2159–69. [CrossRef]

- Martyn-Nemeth P, Phillips SA, Mihailescu D, Farabi SS, Park C, Lipton R, Idemudia E, and Quinn L. Poor Sleep Quality Is Associated with Nocturnal Glycaemic Variability and Fear of Hypoglycaemia in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2018; 74 (10): 2373–80. [CrossRef]

- Mehrdad M, Azarian M, Sharafkhaneh A, Alavi A, Zare R, Hassanzadeh Rad R, and Dalili S. Association Between Poor Sleep Quality and Glycemic Control in Adult Patients with Diabetes Referred to Endocrinology Clinic of Guilan: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2021; 20 (1): 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Angelino S, Longo M, Caruso P, Scappaticcio L, Di Martino N, Di Lorenzo C, Forestiere D, et al. Sleep Quality and Glucose Control in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes during the Seasonal Daylight Saving Time Shifts. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, . 2024; 217 (August): 111859. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Derivation for a given period |

|---|---|

| Sensor usage (%) | (Number of CGM measurements / (Number of minutes in the period of interest / 5) * 100 |

| SG mean, SD, and CV | Mean, SD, and CV of CGM measurements |

| TIR metrics | (Number of CGM measurements in the range of interest / Number of CGM measurements) * 100 |

| Summary Statistic |

Total (N = 41) |

|

|---|---|---|

| PSQI | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) |

| Mean ± SD | 6.0 ± 4.1 | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-8.0) | |

| Min-Max | 1.0 - 17.0 | |

| Sleep quality | ||

| Poor sleepers (PSQI greater than 5) | % (n/Available Measures) | 36.6% (15/41) |

| Good sleepers (PSQI lower or equal to 5) | % (n/Available Measures) | 63.4% (26/41) |

| SummaryStatistic | Total(N = 41) | Poor sleepers(N = 15) | Good sleepers(N = 26) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs.) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.850 |

| Mean ± SD | 51.9 ± 11.6 | 52.2 ± 12.3 | 51.7 ± 11.5 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 51.0 (43.0-63.0) | 51.0 (43.0-63.0) | 50.5 (42.0-64.0) | ||

| Min-Max | 26.0 - 72.0 | 26.0 - 72.0 | 29.0 - 70.0 | ||

| Female | % (n/Available Measures) | 41.5% (17/41) | 46.7% (7/15) | 38.5% (10/26) | 0.745 |

| Diabetes duration (yrs.) | Available Measures (%) | 39 (95.1%) | 15 (100.0%) | 24 (92.3%) | 0.058 |

| Mean ± SD | 25.1 ± 14.6 | 19.2 ± 12.0 | 28.8 ± 15.1 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 25.0 (14.0-34.0) | 17.0 (10.0-32.0) | 27.0 (21.5-37.0) | ||

| Min-Max | 1.0 - 61.0 | 1.0 - 40.0 | 5.0 - 61.0 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Available Measures (%) | 39 (95.1%) | 15 (100.0%) | 24 (92.3%) | 0.516 |

| Mean ± SD | 25.0 ± 4.1 | 25.6 ± 3.6 | 24.6 ± 4.4 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 24.9 (21.7-28.7) | 24.9 (23.0-28.7) | 24.6 (20.7-28.6) | ||

| Min-Max | 18.0 - 32.4 | 19.8 - 32.2 | 18.0 - 32.4 | ||

| Smoking habit | |||||

| Current smoker | % (n/Available Measures) | 22.5% (9/40) | 26.7% (4/15) | 20.0% (5/25) | 0.204 |

| Former smoker | % (n/Available Measures) | 15.0% (6/40) | 26.7% (4/15) | 8.0% (2/25) | |

| Non-smoker | % (n/Available Measures) | 62.5% (25/40) | 46.7% (7/15) | 72.0% (18/25) | |

| Device | |||||

| MiniMedTM 780G | % (n/Available Measures) | 68.3% (28/41) | 60.0% (9/15) | 73.1% (19/26) | 0.492 |

| Medtronic Smart MDI | % (n/Available Measures) | 31.7% (13/41) | 40.0% (6/15) | 26.9% (7/26) |

| SummaryStatistic | Total(N = 41) | Poor sleepers(N = 15) | Good sleepers(N = 26) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG mean (mg/dL) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.310 |

| Mean ± SD | 153.9 ± 18.3 | 157.5 ± 20.4 | 151.8 ± 17.1 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 150.7 (142.0-168.6) | 159.0 (142.0-172.4) | 149.0 (142.0-162.9) | ||

| Min-Max | 117.0 - 197.5 | 120.8 - 194.5 | 117.0 - 197.5 | ||

| SG SD (mg/dL) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.228 |

| Mean ± SD | 47.4 ± 10.7 | 49.4 ± 12.1 | 46.3 ± 9.8 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 44.9 (40.0-51.4) | 49.5 (42.5-53.5) | 42.1 (39.9-48.9) | ||

| Min-Max | 29.9 - 81.2 | 29.9 - 81.2 | 35.3 - 77.3 | ||

| SG CV (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.598 |

| Mean ± SD | 30.7 ± 5.0 | 31.2 ± 5.6 | 30.4 ± 4.6 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 30.2 (27.3-32.4) | 30.6 (26.1-33.6) | 29.2 (27.3-31.7) | ||

| Min-Max | 21.6 - 44.8 | 23.2 - 44.8 | 21.6 - 43.6 | ||

| TBR2 (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.250 |

| Mean ± SD | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.8 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.1 (0.0-0.3) | 0.0 (0.0-0.4) | 0.1 (0.0-0.3) | ||

| Min-Max | 0.0 - 3.9 | 0.0 - 1.0 | 0.0 - 3.9 | ||

| TBR1 (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.167 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 1.9 | 1.3 ± 2.1 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.8 (0.2-1.7) | 0.4 (0.1-1.4) | 1.0 (0.4-2.0) | ||

| Min-Max | 0.0 - 7.5 | 0.0 - 6.9 | 0.0 - 7.5 | ||

| TBR (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.137 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.7 ± 2.4 | 1.5 ± 2.4 | 1.9 ± 2.4 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.9 (0.2-2.1) | 0.5 (0.1-1.8) | 1.1 (0.5-2.3) | ||

| Min-Max | 0.0 - 11.4 | 0.0 - 7.5 | 0.0 - 11.4 | ||

| TIR (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.473 |

| Mean ± SD | 72.0 ± 11.5 | 70.0 ± 13.1 | 73.2 ± 10.6 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 73.3 (65.0-81.7) | 70.3 (59.3-81.9) | 75.5 (68.4-81.7) | ||

| Min-Max | 43.5 - 92.7 | 43.5 - 92.7 | 44.9 - 85.8 | ||

| TAR1 (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.490 |

| Mean ± SD | 21.3 ± 7.9 | 22.2 ± 9.2 | 20.8 ± 7.2 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 21.3 (15.7-26.9) | 23.2 (16.3-30.5) | 21.2 (15.7-25.9) | ||

| Min-Max | 5.3 - 36.2 | 5.3 - 36.2 | 6.7 - 34.2 | ||

| TAR2 (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.120 |

| Mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 5.5 | 6.3 ± 6.2 | 4.1 ± 5.0 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 2.6 (1.4-6.5) | 5.1 (1.7-8.4) | 2.4 (1.0-4.9) | ||

| Min-Max | 0.1 - 20.7 | 0.1 - 20.3 | 0.1 - 20.7 | ||

| TAR (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.365 |

| Mean ± SD | 26.2 ± 12.3 | 28.5 ± 14.0 | 24.9 ± 11.3 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 23.7 (17.2-35.0) | 29.7 (17.9-40.5) | 23.6 (16.9-31.0) | ||

| Min-Max | 5.4 - 56.1 | 5.4 - 56.1 | 7.3 - 54.9 |

| SummaryStatistic | Total(N = 41) | Poor sleepers(N = 15) | Good sleepers(N = 26) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SG mean (mg/dL) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.379 |

| Mean ± SD | 153.0 ± 22.5 | 157.5 ± 24.5 | 150.5 ± 21.3 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 147.5 (141.0-164.5) | 150.5 (142.0-174.0) | 147.1 (135.3-161.0) | ||

| Min-Max | 121.3 - 213.9 | 121.3 - 204.5 | 122.0 - 213.9 | ||

| SG SD (mg/dL) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.113 |

| Mean ± SD | 44.1 ± 12.6 | 48.1 ± 13.5 | 41.7 ± 11.6 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 41.4 (35.5-49.8) | 49.8 (34.4-54.9) | 40.1 (35.5-45.8) | ||

| Min-Max | 26.8 - 84.6 | 27.8 - 72.9 | 26.8 - 84.6 | ||

| SG CV (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.091 |

| Mean ± SD | 28.7 ± 5.9 | 30.6 ± 7.3 | 27.5 ± 4.8 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 28.3 (24.2-31.6) | 29.9 (24.2-35.0) | 28.0 (23.7-29.5) | ||

| Min-Max | 17.4 - 42.5 | 17.4 - 42.5 | 19.0 - 39.6 | ||

| TBR2 (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.977 |

| Mean ± SD | 0.3 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 0.9 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0-0.1) | 0.0 (0.0-0.1) | 0.0 (0.0-0.2) | ||

| Min-Max | 0.0 - 4.2 | 0.0 - 1.9 | 0.0 - 4.2 | ||

| TBR1 (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.691 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.2 ± 2.2 | 1.5 ± 3.1 | 1.0 ± 1.5 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.5 (0.0-1.2) | 0.4 (0.0-0.9) | 0.6 (0.0-1.4) | ||

| Min-Max | 0.0 - 9.9 | 0.0 - 9.9 | 0.0 - 5.5 | ||

| TBR (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.711 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.5 ± 2.8 | 1.8 ± 3.8 | 1.4 ± 2.2 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.5 (0.0-1.3) | 0.4 (0.0-1.0) | 0.6 (0.0-1.7) | ||

| Min-Max | 0.0 - 11.8 | 0.0 - 11.8 | 0.0 - 9.5 | ||

| TIR (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.163 |

| Mean ± SD | 73.7 ± 15.7 | 69.6 ± 16.9 | 76.0 ± 14.9 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 77.3 (66.8-85.3) | 71.0 (60.1-84.2) | 78.7 (70.3-86.5) | ||

| Min-Max | 32.6 - 95.3 | 37.8 - 95.1 | 32.6 - 95.3 | ||

| TAR1 (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.636 |

| Mean ± SD | 20.2 ± 10.8 | 21.8 ± 12.7 | 19.2 ± 9.6 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 19.1 (12.1-26.2) | 19.5 (12.1-30.1) | 17.9 (12.1-24.0) | ||

| Min-Max | 3.8 - 53.6 | 3.8 - 53.6 | 4.6 - 43.6 | ||

| TAR2 (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.013 |

| Mean ± SD | 4.6 ± 6.7 | 6.7 ± 7.2 | 3.3 ± 6.2 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 1.8 (0.5-5.6) | 4.9 (1.4-10.6) | 1.1 (0.5-2.8) | ||

| Min-Max | 0.0 - 27.7 | 0.3 - 27.7 | 0.0 - 27.3 | ||

| TAR (%) | Available Measures (%) | 41 (100.0%) | 15 (100.0%) | 26 (100.0%) | 0.310 |

| Mean ± SD | 24.8 ± 16.0 | 28.5 ± 17.7 | 22.6 ± 14.9 | ||

| Median (IQR) | 20.6 (13.2-33.2) | 24.5 (13.5-39.9) | 19.8 (12.6-27.0) | ||

| Min-Max | 4.1 - 65.0 | 4.1 - 61.2 | 4.7 - 65.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).