1. Introduction

As a medium of material transportation, sea surface current (SSC) serves as a vital conduits for the materials exchange within marine ecosystems [

1]. It mediates the transfer of heat and moisture between the ocean and the atmosphere, thereby influencing weather patterns [

2]. SSC also plays a critical role in coastal areas by shaping coastal landscapes [

3], influencing larval dispersion [

4], pollutant distribution [

5], affecting maritime activities such as shipping and human engineering [

6], and so forth. Accurately deriving SSC is crucial both for better understanding global climate change and optimizing coastal management strategies.

Though traditional method, such as surface drifters [

7] and Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP) [

8] provides reliable SSC measurements, their observation range is often limited. High-frequency (HF) radars can effectively monitor coastal SSC by measuring backscattered radar signals [

9,

10], global HF radar network were established to improve coastal management [

11], but its mapping area is still inadequate to monitor global coastline since its deployment and maintenance can be hard in remote and extreme environments [

12]. Satellite altimetry has also been widely utilized to calculate wide-range ocean current base on geostrophic balance [

13,

14], however, it can only retrieve geostrophic current [

15], while realistic ocean surface current was also affected by tidal current, wind-driven current (Ekman current), Stokes drift and other ageostrophic components. Moreover, current retrieved from altimeter is rather unreliable due to the distortion and contamination in altimeter waveforms in coastal region [

15,

16,

17].

The movement of ocean surface features such as Chlorophyll

a (Chl

-a), Total Suspended Matter (TSM) and Sea Surface Temperature (SST) can effectively indicate the SSC structure [

18], making feature tracking an effective method to retrieve SSC with sequential thermal or ocean color images. Ever since Emery et al. [

19] first applied the Maximum Cross Correlation (MCC) approach, which is commonly used in image registration and cloud motion detection, to advanced very high-resolution radiometer (AVHRR) images and extracted SSC in coastal ocean of Colombia, MCC has been widely used to retrieve SSC in various sea areas with different satellite images. Taniguchi et al. [

20] derived the surface velocity in Lombok Strait using hourly Himawari-8 SST data. Liu et al. [

12] investigated SSC in the California coast by merging MCC results from different surface tracers including SST, Chl

-a concentration and Remote Sensing Reflectance (

). Yang et al. [

21] derived SSC in the U.S. East and Gulf coasts by utilizing overlap area of Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer (VIIRS) and compared SSC products generated by different tracer images. Ren et al. [

22] applied MCC to X-band synthetic aperture radar (SAR) image to derive high resolution tidal current in Hangzhou Bay and Amrum Island. Apart from MCC, various other approaches have been implemented on sequential satellite images to obtain SSC, including optical flow [

23,

24], Doppler shift [

25,

26], inter-band time-lag [

27], displaced frame central difference equation [

28], etc.

During the process of feature tracking, inconsistencies in spatial resolution and band settings is inevitable for multi-sensor images. However, geostationary satellite can avoid these issues and stably generate consecutive images. Korean Geostationary Ocean Color Imager (GOCI) provides hourly images in the time range of UTC 0:00–7:00, making it one of the most commonly used sensors in SSC extraction. Yang et al. [

29] analyzed the diurnal variation of SSC and the eddy structures in the west coast and East Sea of Korea, using GOCI-derived TSM and Chl

-a as tracers for the MCC technique. Based on GOCI image, Jiang et al. [

30] comprehensively tested different parameters for best performance of MCC in Bohai Sea, validation with ADCP, HF radar and numerical model both shows good results. Hu et al. [

31] tested the Particle image velocimetry (PIV) method on GOCI-derived TSM and Chl

-a to derive SSC in East China sea and Japan Sea, achieving solid performance especially in eddy area with strong rotational and deformation. Using five years of GOCI Level-2 (L2) products and optimal interpolation, Liu et al. [

32] extracted SSC in entire GOCI’s observation range and analyzed annual and seasonal mean flows.

The aforementioned studies mainly focus on sea areas where surface tracers have distinct gradient and stable structure. In shallow nearshore area such as the Yangtze River estuary (YRE) and Korean Coastal Sea (KCS), land boundaries are much more intricate, horizontal transport and vertical mixing are jointly influenced by river discharge, tidal current and wind, which lead to a more complex and dynamic current structure and surface tracers [

33,

34], causing obstacles in precise high-resolution SSC estimation. However, due the tide-dominance characteristic in these areas [

35,

36], surface total current direction can be highly consistent with tidal current during the flooding and ebbing phases, when the tidal current magnitude is large [

30,

37].

The objective of our study is to fill the gaps in SSC estimation in coastal and estuary areas, an improved MCC workflow, called the Tide Restricted Maximum Cross Correlation (TRMCC) is developed by integrating the FES2014 tide model and applied to GOCI-II ocean color data from 2021 to 2023. Cross-comparisons are performed between SSC estimation results, buoy data, HF Radar and numerical model. High-resolution SSC structures in multiple regions are revealed. Our study provides new insight in SSC estimation in coastal areas via ocean color remote sensing.

The structure of this article is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the data used in this study.

Section 3 explains the methodology of our research.

Section 4 presents the SSC estimation performance over both long-term and short-term with cross-comparison to SSC data obtained from GOCI-II L2 product, numerical model product, HF Radar and buoy. TRMCC’s ability to reveal high-resolution SSC structures in turbid coastal areas at different time scale is also tested. Finally, discussions and conclusions are presented in

Section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. GOCI-II Data

Sequential images with both high spatial resolution and short time interval are the cornerstone of retrieving SSC from ocean color data. GOCI-II (Geostationary Ocean Color Imager II) was mounted on Korean satellite GEO-KOMPSAT-2B that was launched in February 2020, it has a spatial resolution of 250 meters, and 12 bands in the visible and near-infrared range, covering most of the sea areas of Korea, Japan and China. It is capable of conducting 10 observations per day, from UTC 23:30 to 8:30, with an interval of 1 hour, perfect for the extraction of SSC. GOCI-II data can be obtained from Korea Ocean Satellite Center (KOSC) website (

https://kosc.kiost.ac.kr/, accessed on 06 January 2024). Since a full scene of GOCI-II image consists of 12 sub-images obtained by step and stare method, data from two different slots were used in this study: Slot S007 that covers Korean Sea and Slot S010 that covers East China Seas (

Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Area of interest (AOI) of this study. Orange and green square represents the observation range of GOCI- II data in two different slots (named by S010 and S007). White dashed line is the isobath in the AOI. Stars and red dashed border represent location of buoys and HF Radars. (b) Valid data time range of ocean color data (blue), Korean buoy (green) and Chinese buoy (orange). (c) Underground topography of the YRE, black solid line represents the location of Deep-Water Channel Project.

Figure 1.

(a) Area of interest (AOI) of this study. Orange and green square represents the observation range of GOCI- II data in two different slots (named by S010 and S007). White dashed line is the isobath in the AOI. Stars and red dashed border represent location of buoys and HF Radars. (b) Valid data time range of ocean color data (blue), Korean buoy (green) and Chinese buoy (orange). (c) Underground topography of the YRE, black solid line represents the location of Deep-Water Channel Project.

For case in Korean Sea, previous studies have proved that Chl

-a can be a suitable tracer in sea areas with relatively low turbidity such as California Coast and Korean Sea [

29,

31,

38,

39]. Therefore, GOCI-II L2 Chl

-a product of slot S007 (green square in

Figure 1a) was selected as tracer data to derive SSC in the sea area of Korean Peninsula. This product is generated based on L2 Atmospheric Corrected

Rrs product using Ocean Color Index (OCI) algorithm [

40]. Full data from 2021 to 2023 was used, adding up to a total of 10407 scenes.

For case in East China Seas, due to the shallow topography and abundant terrestrial sediment input from the Yangtze River and Yellow River, optical properties in East China Seas are strongly influenced by suspended sediment, creating obstacles for accurately deriving Chl

-a [

41,

42]. Therefore, in these area, TSM has been widely used in SSC estimation [

31,

43,

44,

45]. However, in extremely turbid nearshore and estuary areas such as the YRE, the official atmospheric correction method of GOCI-II performs poorly, resulting in large blank area in ocean color product of slot S010. Therefore, high-quality Level 1B Top-of-Atmosphere Radiance product of slot S010 (orange square in

Figure 1a) from 2021 to 2023 was manually filtered (

Figure 1b), adding up to a total of 5445 scenes in 573 days. Rayleigh correction was performed with an atmospheric vector radiative transfer model [

46,

47]. Cloud areas were then masked based on an improved cloud masking method [

48]. Atmospheric correction was performed with XGB-CW [

49], a new atmospheric correction algorithm especially designed for highly turbid waters, which combines a coupled ocean-atmosphere model with the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). After

Rrs was obtained, TSM was derived by a semi-empirical radiative transfer model [

50] and was selected as tracer data to derive SSC in the East China Sea areas.

Moreover, GOCI-II official L2 SSC data products of slot S007 and S010 from 2021 to 2023 were also downloaded for cross comparison. These SSC data were developed by using L2 Chl

-a product as tracer image, and a primitive MCC algorithm based on Barton et al [

51] and Emery et al [

19]. This product has gone through a quality control process using global mean ocean surface velocities calculated from 30 years of satellite-tracked surface drifter data.

2.1.2. Buoy Data

In order to exam the accuracy of retrieved SSC, hourly SSC data of 14 buoys from 2021 to 2023 was collected to be seen as Ground Truth (GT), 8 of which are located in KCS (as shown in

Figure 1a) and 6 of which are located in the YRE, China (as shown in

Figure 1c). Korean buoys data which includes surface current speed and direction was downloaded from Korea Hydrographic and Oceanographic Agency website (

http://www.khoa.go.kr/, accessed on 10 February 2024), 4 of them was located in outer sea (KG_0021, KG0024, KG0025, KG0028), and 4 of them was located in the coastal sea with lower water depth and more intricate land boundaries (TW_0069, TW_0079, TW_0080, TW_0081). Moreover, six buoys were deployed in the YRE, located in the North Channel, North Passage and South Passage (as shown in

Figure 1c), capable of providing current speed and direction of vertical water column. In order to reduce noise, current data in the depth of 0 to 2 meters were averaged and seen as SSC. The available time range of 14 buoys can be seen in

Figure 1b.

2.1.3. High Frequency Radar Data

Data of four High Frequency (HF) radar sites (as shown in

Figure 1a) were also downloaded from Korea Hydrographic and Oceanographic Agency website (

http://www.khoa.go.kr/, accessed on 12 February 2024) to perform accuracy verification of retrieved SSC. These HF radar sites are located in different geographical environments (e.g., shallow coast, water bay, deep sea), with resolution ranging from 0.75 to 3 km, and operating frequency ranging from 13 to 25 MHz and band width ranging from 50 to 200 kHz [

52]. Additionally, buoy KG_0024 is located in the observation range of HF radar site HF_0041, which makes it possible to make a cross comparison between SSC retrieved by different method.

2.1.4. Numerical Model Data

CMEMS (Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service) products has been widely used to study coastal ocean dynamics [

53,

54]. In this study, SSC data from CMEMS product “GLOBAL_ANALYSISFORECAST_PHY_001_024” was used for cross comparison. The product is based on version 3.6 of NEMO (Nucleus for European Modelling of the Ocean) ocean model, coupled with new data assimilation method and observation data [

55], and is capable of providing hourly SSC with a resolution of 1/12°. This product is available at Copernicus Marine Data Store (

https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/products, accessed on 06 February 2024).

2.1.5. Tide Model

In this study, Finite Element Solution (FES) tide model was utilized to simulate surface tidal current and tidal height. As the latest version of FES tide model, FES2014 has a higher horizontal resolution of 1/16°, a more accurate bathymetry and shoreline grid in shallow water areas, an expanded altimetry and tidal gauges assimilation database and more advanced data assimilation method [

56]. FES2014 tide model can be downloaded from Archiving, Validation and Interpretation of Satellite Oceanographic (Aviso) website (

https://www.aviso.altimetry.fr/en/data/products/auxiliary-products/global-tide-fes.html, accessed on 04 December 2023). Previous studies have pointed out that FES2014 provides a more reliable result than other ocean tide model in both East China Seas [

57,

58] and coastal sea of Korean Peninsula [

59].

2.2. Methods

Considering above mentioned obstacles in SSC estimation and the notable contribution of tidal current in coastal sea, we proposed an improved MCC workflow called the Tide Restricted Maximum Cross Correlation (TRMCC). It is capable of producing high-resolution and high-accuracy SSC result especially in coastal sea area. The workflow diagram of the TRMCC can be seen in

Figure 2, and its main improvements are as follows.

Figure 2.

Workflow diagram of TRMCC. Blue part represents the process of Tide-Restriction. Red part is the circulation to decide a reference window size by evaluating feature in the reference window. Green part is the Masked Normalized Cross-Correlation technique.

Figure 2.

Workflow diagram of TRMCC. Blue part represents the process of Tide-Restriction. Red part is the circulation to decide a reference window size by evaluating feature in the reference window. Green part is the Masked Normalized Cross-Correlation technique.

2.2.1. Normalized Cross-correlation in Fourier Domain

Invalid data in data window can greatly influence the SSC deriving result. In order to minimize the influence caused by land or cloud cover, a Masked Normalized Cross-Correlation (NCC) technique [

60] was adopted to evaluate the cross correlation between reference window and suspected target window. This is an image registration method originally developed for medical imaging, by introducing masked area into the Fourier-Merlin algorithm, it can effectively avoid influence caused by masked area, which in our case is invalid data caused by land and cloud cover. The NCC can be calculated as:

where NCC is the normalized cross-correlation,

and

represent Fourier and inverse Fourier transform,

and

is two image windows,

and

is the Fourier transformed image windows,

M1 and

M2 is the Fourier transformed mask of two image. More details can be seen in [

60].

2.2.2. Restricted Angular Search Range

In Coastal seas, tidal current can be the dominant current component rather than geostrophic current, wind-driven current and so on. Genuine current’s direction can be significantly affected by tidal current. As shown in the density plot (

Figure 3) of over 630,000 data pair between simulated tidal current and genuine current observed by buoys, a clear pattern between tidal current magnitude (

) and angular difference of genuine current and tidal current (

) can be concluded. The larger the

, the smaller the angular difference between genuine current and tidal current. 63.3% of

distributes in the range of 5 to 75 cm/s, while the angular difference distributes in the range of 0 to 30. Therefore, in this study, we defined a variable

which stand for the angular difference between simulated tidal current direction and the genuine current direction and assume

has a functional relationship with

that can be expressed as a linear combination of exponential functions as follows:

where

is the angular difference,

is the tidal current magnitude, a, b, c and d are undetermined coefficients.

Figure 3.

Scatter density plot between tidal current magnitude and angular difference of genuine current and tidal current. Red line indicates the curve of .

Figure 3.

Scatter density plot between tidal current magnitude and angular difference of genuine current and tidal current. Red line indicates the curve of .

Based on vast number of data-pair between simulated tidal current and genuine current, four coefficients in Eq.(2) were obtained by using Gaussian Kernel Density Estimation (GKDE) to model the distribution of

and

, and an optimization algorithm to ensure the resulting function can cover at least 99% of the data-pair while minimizing the angular difference. Finally, the functional relationship between

and

can be expressed as:

where

is the angular difference, and

is the tidal current magnitude.

During the workflow of the TRMCC (as shown in

Figure 4), tidal current magnitude (

) and direction (

) between the time range of two sequential images was generated by tide model, the mean value (

and

) will be seen as the tidal current vector corresponding to the estimation time.

was decided by

based on Eq.(3), and the angular restriction range can be defined as [

. As shown in

Figure 4, taking two Chl

-a images from 8:30 to 9:30 (UTC+9) on April 25, 2021, as an example, suspected vector (gray arrow) that is outside the restriction range was discarded even though it has a higher NCC.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of angular restriction range, taking Chl-a images from 8:30 to 9:30 (UTC+9) on April 25, 2021, as an example. Vector and window border in green and gray represents search result after and before Tide-Restriction.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of angular restriction range, taking Chl-a images from 8:30 to 9:30 (UTC+9) on April 25, 2021, as an example. Vector and window border in green and gray represents search result after and before Tide-Restriction.

2.2.3. Adaptive Reference Window Size

In the workflow of conventional MCC approach, size of the Reference Window (

) significantly influences the accuracy of SSC estimation and can be various depend on the research area. For example, previous study that apply MCC on GOCI data to derive SSC,

varies from 10 to 22 km [

29,

32,

39,

45,

61]. However, in coastal sea area such as the YRE, SSC shows a much finer structure and can be dissimilar even in an area of 10×10 km, not to mention the inner estuary where the width of the river channel can be less than 6 km. When implementing MCC on different areas,

should be decided based on the feature scale and signal abundance of surface tracer, since an excessively large window size cannot reflect the fine structure of SSC [

22].

Therefore, we bought in the coefficient of variation (

) into the workflow (as shown in

Figure 2) to evaluate the signal abundance.

of an image window can be computed as:

where SD and MN are standard deviation and mean value of a window.

With an initial of 15 pixels (3.75 km), if the is less than a threshold of 15% and the invalid data percentage is less than 20%, will be expanded for 2 pixels and repeat this process until reaches the threshold or exceeds 61 pixels (15.25 km). After this cycle, an optimal can be decided ensuring a suitable amount tracer signal while assuring an acceptable invalid data percentage.

2.2.4. Accuracy Evaluation Metrics

Following previous research [

28,

62,

63], Average Angular Error (AAE) and Average Magnitude Error (AME) were used to evaluate the performance of SSC estimation. AAE, AE, AME, and ME can be calculated as follow:

where

is the current vector that’s being evaluated, and

is the ground truth (buoy) vector.

3. Results

3.1. Validation Using Buoy Data

To thoroughly verify TRMCC’s in different sea area, SSC in 14 buoys’ location from 2021 to 2023 was derived based on GOCI-II data. In order to demonstrate the effect of Tide-Restriction, a reference data group without the process of Tide-Restriction is also generated. The performance of Tide Restricted method (TRMCC), Unrestricted method and GOCI-II official method were shown in

Table 1 (8 Korean buoys) and

Table 2 (6 Chinese buoys).

Table 1.

Comparison of different SSC results in Korean Coastal Sea in 3 years.

Table 1.

Comparison of different SSC results in Korean Coastal Sea in 3 years.

| Type |

Buoy ID |

Tide Restricted |

Unrestricted |

Official SSC Product |

| AME |

AAE(°) |

Count |

AME |

AAE(°) |

Count |

AME |

AAE(°) |

Count |

| OffShore |

KG_0021 |

0.481 |

35.472 |

340 |

0.48 |

35.605 |

340 |

0.584 |

38.937 |

146 |

| KG_0024 |

0.429 |

39.562 |

1326 |

0.429 |

39.353 |

1329 |

0.528 |

55.835 |

361 |

| KG_0025 |

0.46 |

34.45 |

1340 |

0.46 |

34.512 |

1340 |

0.519 |

55.747 |

334 |

| KG_0028 |

0.571 |

33.56 |

960 |

0.573 |

34.764 |

964 |

0.504 |

53.879 |

396 |

| Mean/Sum |

0.48525 |

35.761 |

3966 |

0.4855 |

36.0585 |

3973 |

0.53375 |

51.0995 |

1237 |

| NearShore |

TW_0069 |

0.546 |

29.375 |

819 |

0.554 |

38.126 |

842 |

0.835 |

80.53 |

41 |

| TW_0079 |

0.394 |

26.072 |

1132 |

0.396 |

28.543 |

1144 |

0.806 |

75.479 |

37 |

| TW_0080 |

0.544 |

33.447 |

1056 |

0.534 |

40.52 |

1078 |

0.868 |

101.846 |

36 |

| TW_0081 |

0.409 |

33.347 |

1226 |

0.412 |

35.144 |

1235 |

0.795 |

101.245 |

54 |

| Mean/Sum |

0.47325 |

30.5603 |

4233 |

0.474 |

35.5833 |

4299 |

0.826 |

89.775 |

168 |

In the offshore area of Korean Sea, though the accuracy of official SSC product is only slightly lower than our method, it yields only about one-third the amount of valid data of our method. Considering that both three results were based on the same L2 Chl-a data, it is possible that the production process of the SSC product can’t deal with invalid data caused by cloud cover. The difference between Tide Restricted method and Unrestricted method is very small, since in offshore area is relatively smaller than nearshore area. According to Eq.(3), need to be greater than 26.1 cm/s, or the will be over 180°, under this circumstance, the angular search range is still [0,360], which means the Tide-Restriction didn’t take effect.

Table 2.

Comparison of different SSC results in the YRE in 3 years.

Table 2.

Comparison of different SSC results in the YRE in 3 years.

| Buoy ID |

Tide Restricted |

Unrestricted |

| AME |

AAE(°) |

Count |

AME |

AAE(°) |

Count |

| ECNU_01 |

0.612 |

41.801 |

134 |

0.646 |

44.105 |

134 |

| ECNU_02 |

0.647 |

23.607 |

562 |

0.746 |

39.458 |

743 |

| ECNU_03 |

0.563 |

34.114 |

578 |

0.857 |

79.771 |

710 |

| ECNU_04 |

0.528 |

35.473 |

464 |

0.587 |

78.665 |

547 |

| ECNU_05 |

0.651 |

22.195 |

307 |

0.695 |

67.113 |

513 |

| ECNU_06 |

0.437 |

33.672 |

477 |

0.858 |

89.789 |

566 |

| Mean/Sum |

0.573 |

31.810333 |

2522 |

0.7315 |

66.4835 |

3213 |

Whereas in the nearshore area, the advantage of our method began to take shape. While official SSC product shows poor accuracy and few valid data count, Unrestricted results which utilize adaptive reference window size and masked technique achieved valid observation of 4299, with a good accuracy of 35.6° in angular error and relative magnitude error of 0.47. The AAE was further improved by 14.1% on average under the effect of Tide-Restriction, this improvement varies on the location of buoy, with a best improvement of 23.0% at TW_0069, and a least improvement of 5.1% at TW_0081. However, the improvement in AME is relatively small.

In the YRE where water is much shallower than that in the KCS, Tide-Restriction yielded huge improvement both in AME and AEE. On average, AME were improved by 21.7% and AAE were improved by 52.2%. This improvement is most obvious in ECNU_03 and ECNU_06, each are improved by 34.3% and 49.1% in AME, 57.2% and 62.5% in AAE, respectively. However, valid vector count was dropped by 21.5% on average, indicating a failure in finding a target vector that matches correlation limit while staying in the angular restriction range. Moreover, official SSC product completely loses its’ effectiveness, with no valid data in the YRE, since the official atmospheric correction method hardly works in highly turbid water of the YRE, and the inability of official SSC extraction methods to deal with invalid data.

3.2. Cross-Comparison of SSC Derived from Satellite, Numerical Model and HF Radar

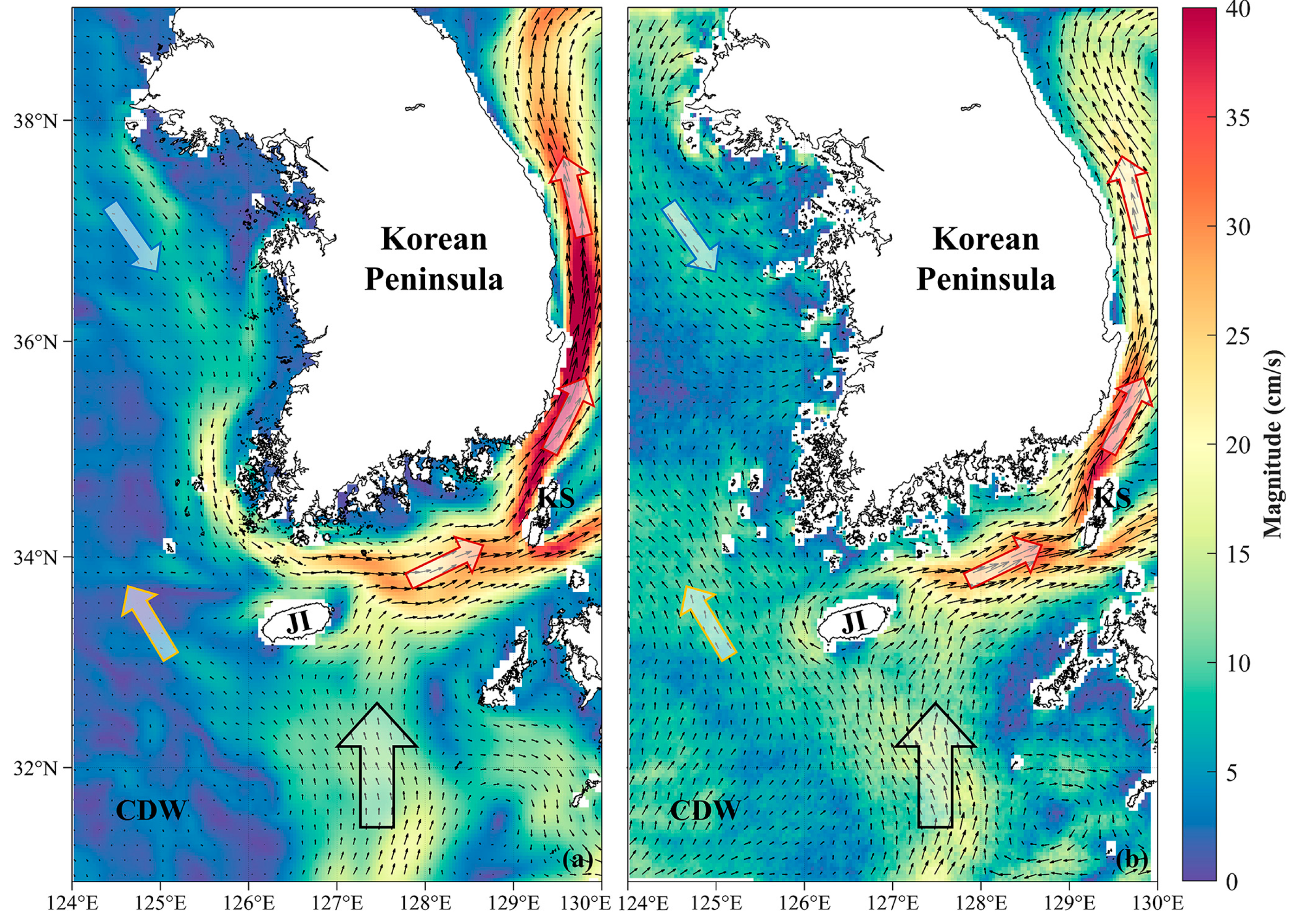

To further investigate SSC pattern in a larger spatial scale, mean SSC of CMEMS product and TRMCC results from 2021 to 2023 can be seen in

Figure 5. Overall, both results show similar current structure. After Kuroshio (black arrow) arrive at the Jeju Island, it was divided into Yellow Sea Warm Current (YSWC, yellow arrow) and East Korea Warm Current (EKWC, red arrow). EKWC was bifurcated by Korean Strait (KS) and flow into the Sea of Japan. However, differences exist in distribution of SSC magnitude. CMEMS product shows a higher magnitude in EKWC than TRMCC results, while in YSWC and area of Changjiang (Yangtze) Diluted Water (CDW), TRMCC results shows a higher magnitude.

Figure 5.

Mean SCC obtained by CMEMS product (a) and TRMCC (b) from 2021 to 2023 in the sea area of Korean Peninsula, overlaying with average current magnitude. Arrow in black, red, blue and yellow border represents the Kuroshio, East Korea Warm Current, Korean Coastal Current and Yellow Sea Warm Current. KS: Korean Strait. JI: Jeju Island. CDW: Changjiang (Yangtze) Diluted Water.

Figure 5.

Mean SCC obtained by CMEMS product (a) and TRMCC (b) from 2021 to 2023 in the sea area of Korean Peninsula, overlaying with average current magnitude. Arrow in black, red, blue and yellow border represents the Kuroshio, East Korea Warm Current, Korean Coastal Current and Yellow Sea Warm Current. KS: Korean Strait. JI: Jeju Island. CDW: Changjiang (Yangtze) Diluted Water.

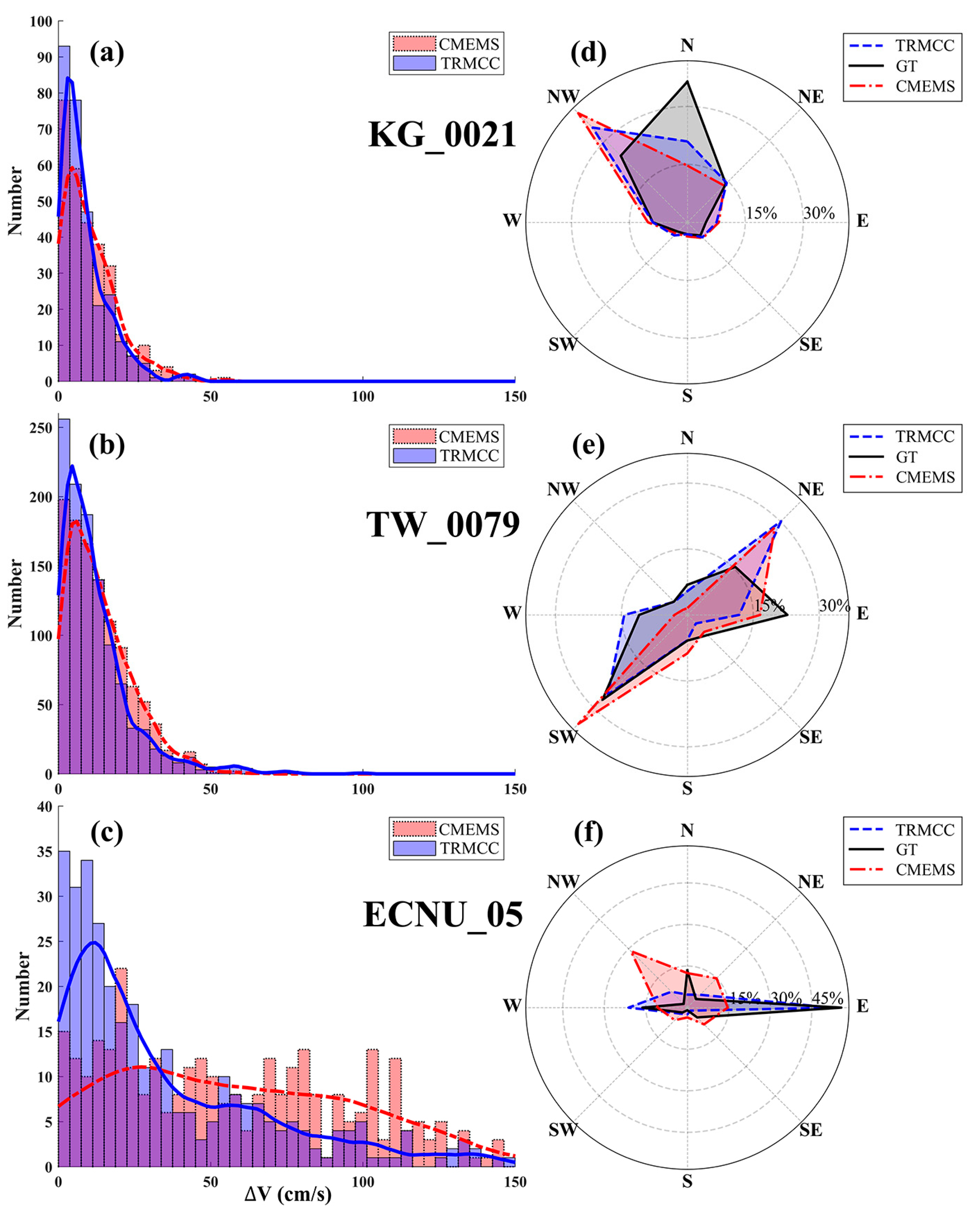

In order to examine the differences between CMEMS product and TRMCC results, three representative buoys were selected, and their magnitude differences and the direction distribution can be seen in

Figure 6. For buoy KG_0021 (115m in depth) located in outer sea, as shown in

Figure 6a,d, both results match the actual situation that SSC mainly flows to the north and northwest, while TRMCC results yields a relatively higher accuracy in magnitude. For buoy TW_0079 (25m in depth) located in the west coast of Korea, as shown in

Figure 6a,e, SSC mainly flows to the southwest, both results slightly overestimated the flow in the northeast, but TRMCC results still shows a higher an accuracy in magnitude. However, for ECNU_05 (5m in depth) located in the shallow YRE, as shown in

Figure 6c,f, CMEMS product shows a rather poor performance both in magnitude and direction. SSC in the YRE were confined by river channel and highly influenced by runoff and tidal current, resulting in a reciprocal flow pattern in west and east direction, TRMCC results correspond well with buoy data while preserving a relatively good accuracy in magnitude.

Figure 6.

(a-c) Distribution of magnitude differences between TRMCC results, CMEMS product and buoy data. (d-f) Distribution of velocity direction between TRMCC results, CMEMS product and buoy data.

Figure 6.

(a-c) Distribution of magnitude differences between TRMCC results, CMEMS product and buoy data. (d-f) Distribution of velocity direction between TRMCC results, CMEMS product and buoy data.

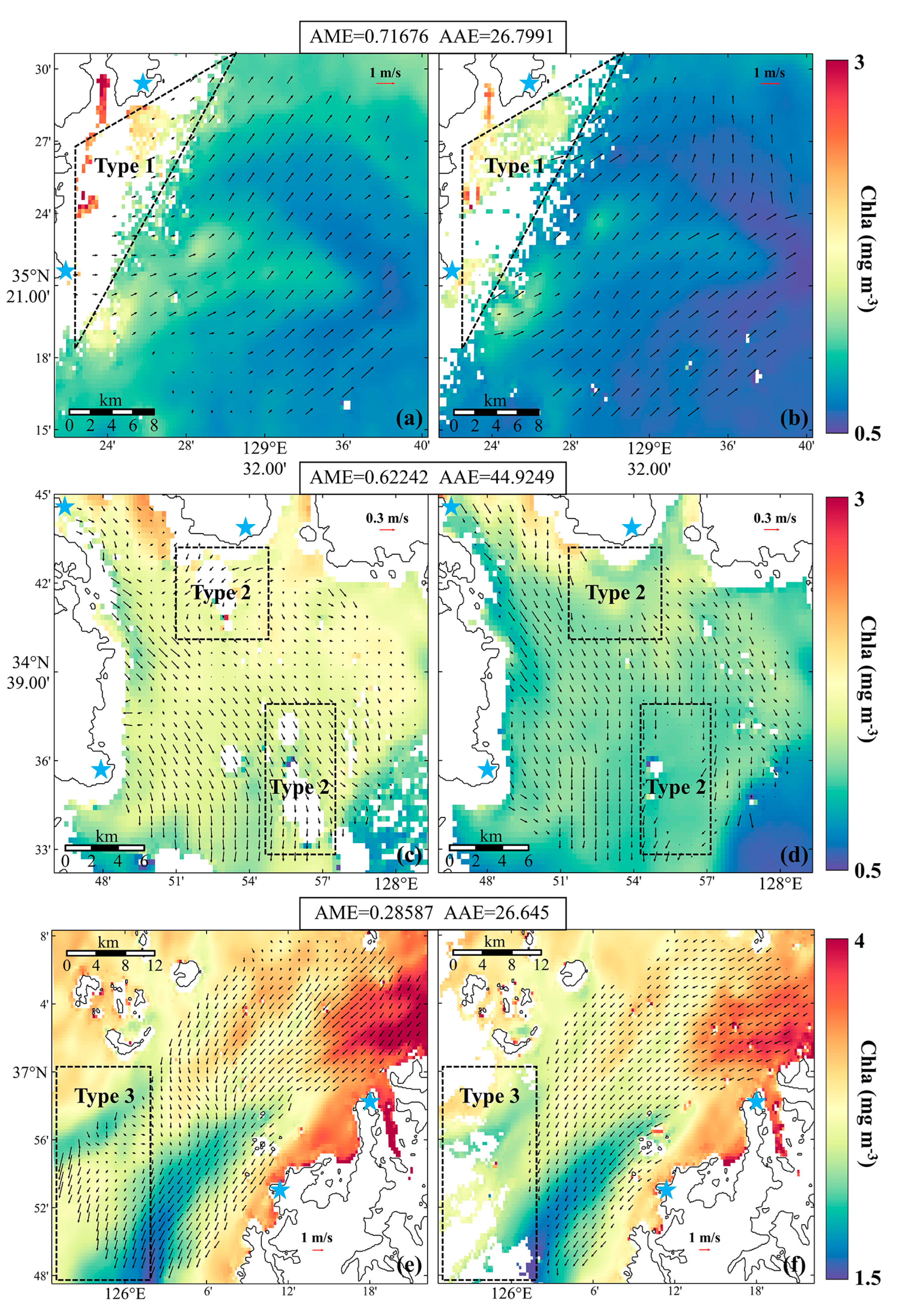

Furthermore, data from three HF Radar sites located in different water depth was selected to demonstrate TRMCC’s performance in costal sea and the influence caused by invalid data in sequential images. TRMCC results was resampled into corresponding resolution of HF Radar, and the results are presented in

Figure 7. It can be seen that TRMCC results generally agrees well with SSC observed by HF Radar both in direction and velocity. However, extremely fine scale structure of SSC in coastal area can still be neglect, for example, in the northwest part of HF_0065 (

Figure 7c) and the west part of HF_0070 (

Figure 7e), where HF Radar depicts a more detailed current structure. Moreover, since GOCI-II L2 Chl

-a product was used as tracer image, invalid data exists in L2 product due to failure of atmospheric correction in turbid water (e.g., Type 1 in

Figure 7a,b and Type 3 in

Figure 7e,f) and cloud cover (e.g., Type 2 in

Figure 7c,d). Though the TRMCC is able to ignore certain amount of invalid data by Masked NCC technique, information loss caused by huge blank area can still inevitably lead to a failure in the TRMCC process.

Figure 7.

SSC derived by HF Radar (left) and TRMCC (right) at 9:00 (UTC+9) in 24 Oct 2022, overlaying with the GOCI-II Chl-a product at 8:30 (left) and 9:30 (right). (a) HF_0063. (c) HF_0065. (e) HF_0070. Blue star represents the location of radar sites. SCC derived by TRMCC outside the observation range of HF Radar was removed for better visualization.

Figure 7.

SSC derived by HF Radar (left) and TRMCC (right) at 9:00 (UTC+9) in 24 Oct 2022, overlaying with the GOCI-II Chl-a product at 8:30 (left) and 9:30 (right). (a) HF_0063. (c) HF_0065. (e) HF_0070. Blue star represents the location of radar sites. SCC derived by TRMCC outside the observation range of HF Radar was removed for better visualization.

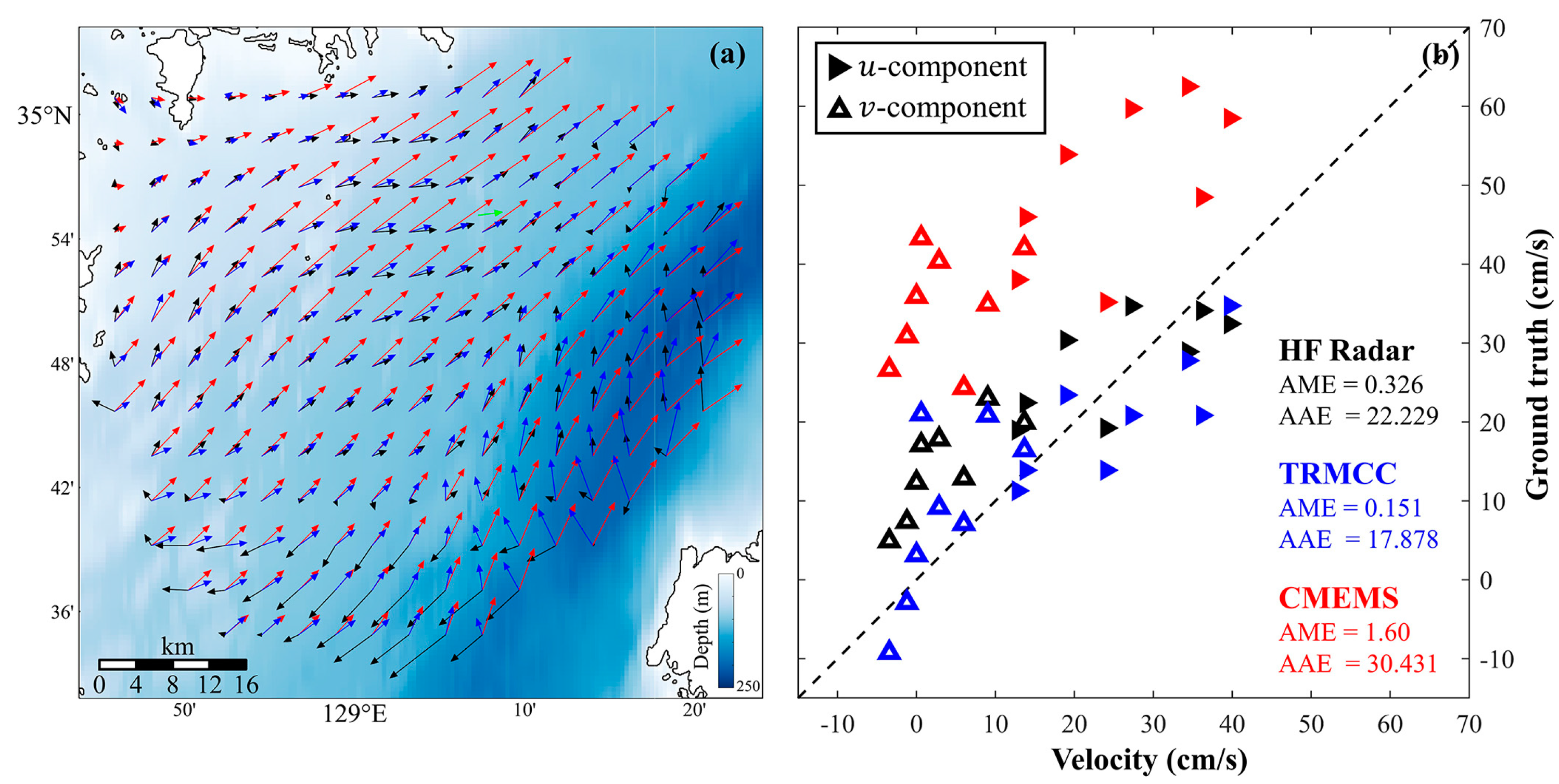

To thoroughly investigate the performance of different SSC results, data from a buoy located in Korean Strait was regard as ground truth, SSC from HF Radar, CMEMS product and TRMCC results were resampled into resolution of 4 km, daily average SSC of different data can be seen in

Figure 8a. In the northwest part where water depth is around 50 meters, three SSC data correspond well in direction, with CMEMS product overestimated the velocity magnitude. However, in south part and area with high water depth, TRMCC results agrees well with CMEMS product that SSC mainly flows in a northeasterly direction, while HF Radar depicts a completely opposite direction. Furthermore, eastward and northward component of flow vector from 9:00 to 16:00 (UTC+9) in three different data was compared with buoy data. It can be seen in

Figure 8b that though vector direction from CMEMS product agrees well with ground truth with AAE being 30.431°, it overestimated the velocity, resulting in a AME of 1.6. Vector derived by HF Radar and TRMCC, on the other hand, shows a better accuracy both in velocity and direction, with a AME of 0.326 and AAE of 22.229° for HF Radar, and even better results from TRMCC, with AME and AEE being 0.151 and 17.878°.

Figure 8.

(a) Average SSC in Korean Strait from 9:00 to 16:00 (UTC+9) on May 5, 2022. Green, black, blue and red vector represents current derived by buoy, HF Radar, TRMCC and CMEMS, respectively. SCC derived by TRMCC and CMEMS that are outside the observation range of HF Radar was removed for better visualization. (b) Comparison between HF Radar (black), TRMCC (blue), CMEMS (red) and ground truth (buoy). Solid triangle represents eastward component (u) and hollow triangle represents northward component (v).

Figure 8.

(a) Average SSC in Korean Strait from 9:00 to 16:00 (UTC+9) on May 5, 2022. Green, black, blue and red vector represents current derived by buoy, HF Radar, TRMCC and CMEMS, respectively. SCC derived by TRMCC and CMEMS that are outside the observation range of HF Radar was removed for better visualization. (b) Comparison between HF Radar (black), TRMCC (blue), CMEMS (red) and ground truth (buoy). Solid triangle represents eastward component (u) and hollow triangle represents northward component (v).

3.3. Fine-scale SSC Seasonal Variation in Bohai Sea

As one of the biggest shelf seas in the world, East China Sea is known for its shallow water depth and abundant terrestrial sediment input, making it hard for altimeter and numerical model to retrieve SSC. However, sediment floating on the sea surface can also be a perfect tracer, facilitating the extraction of SSC by feature tracking.

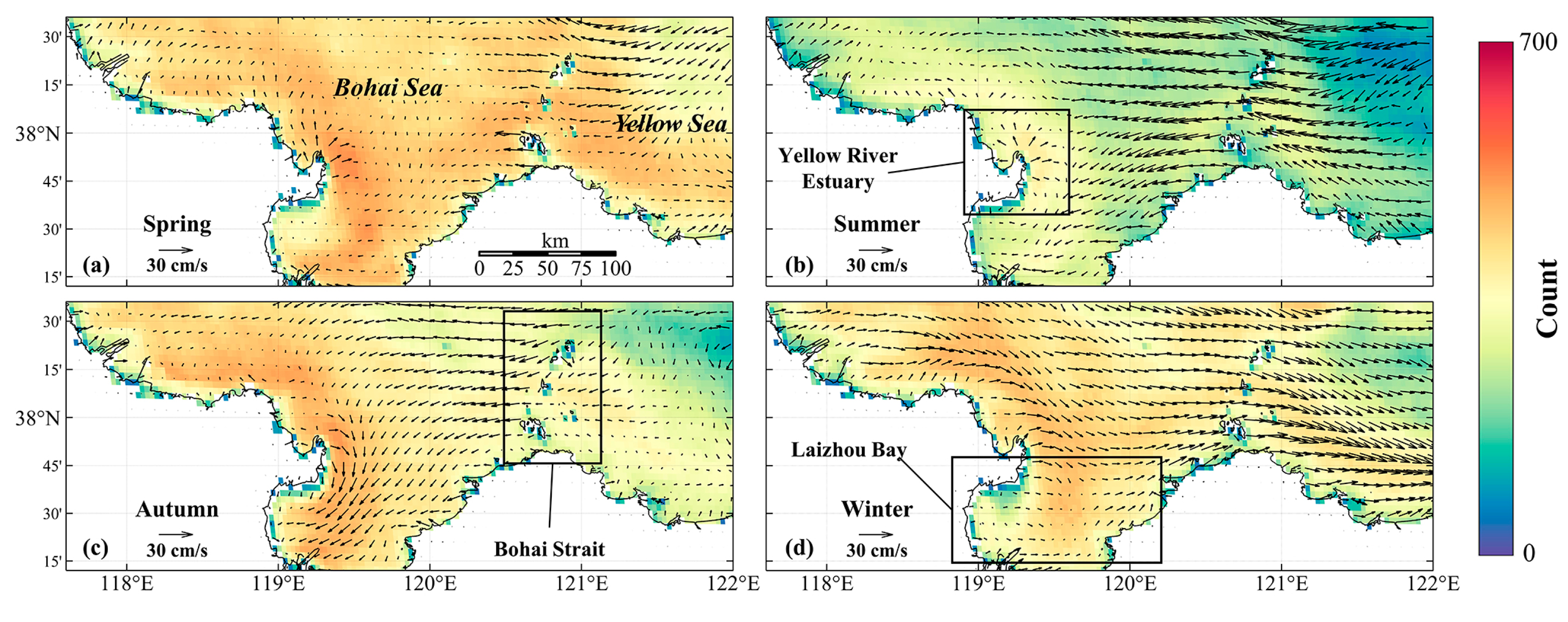

Taking Bohai Sea (BS) as an example, seasonal mean SSC was derived by the TRMCC based on TSM images from 2021 to 2023, and the result can be seen in

Figure 9. Due to the dominance southeast and northwest wind in summer and winter, it can be seen that in Bohai Strait, SSC flows from Yellow Sea (YS) to BS in summer and the contrary in winter, with a mean velocity of around 30 cm/s. SSC around the Yellow River Estuary shows a consistent outward diffusion pattern in every season due to the runoff of Yellow River and converge into the Laizhou Bay in autumn under the influence of the north wind. The number of valid vectors reach up to around 500 for each season in the inner Bohai Sea where the water is rich in sediment. But the number is generally lower in summer due to a higher cloud cover rate.

Figure 9.

Seasonal mean SSC from 2021 to 2023 in Bohai Sea, overlaying with valid vector data count. (a) Spring. (b) Summer. (c) Autumn. (d) Winter.

Figure 9.

Seasonal mean SSC from 2021 to 2023 in Bohai Sea, overlaying with valid vector data count. (a) Spring. (b) Summer. (c) Autumn. (d) Winter.

3.4. Fine-scale SSC Diurnal Variation in Yangtze River Estuary

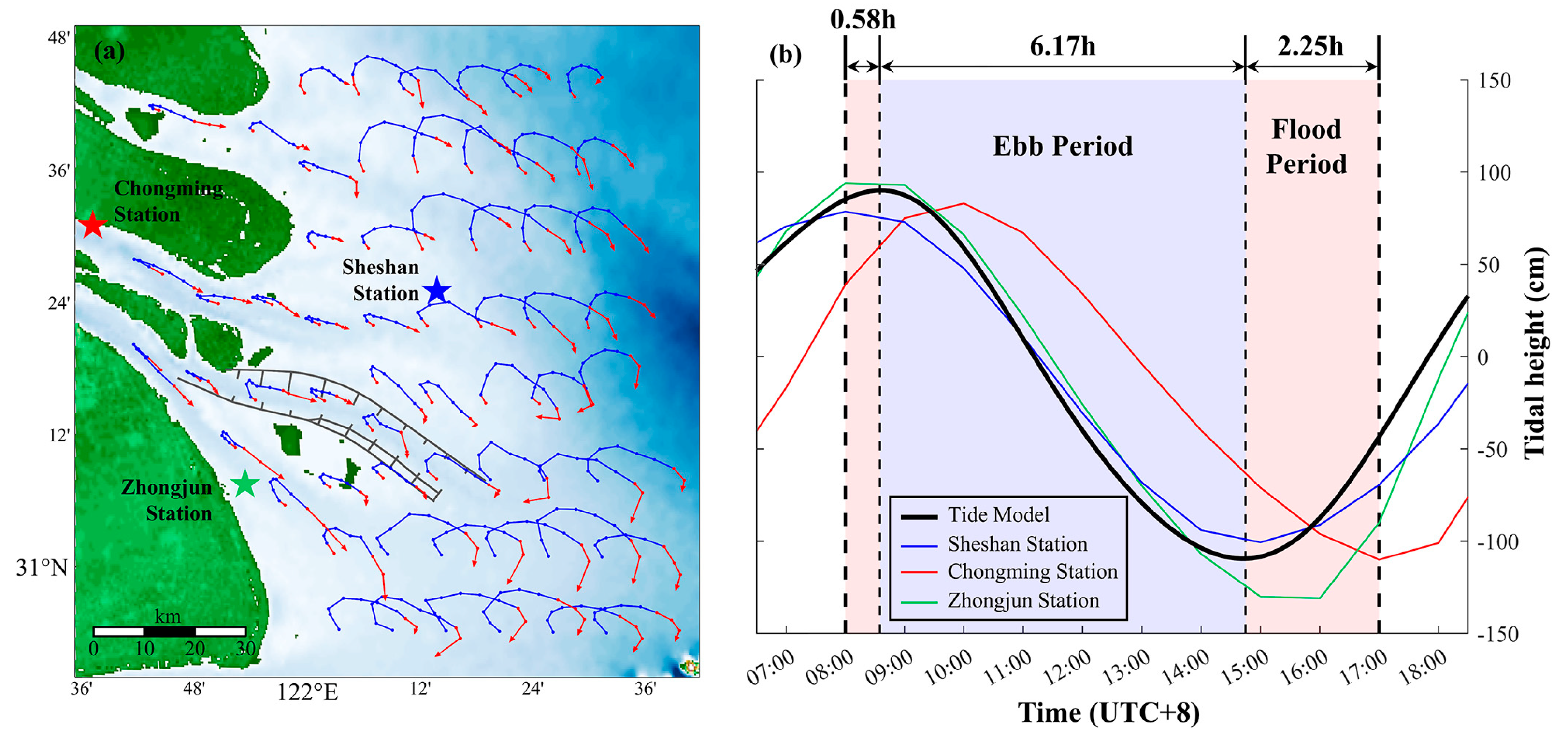

Another example to show TRMCC’s ability to retrieve high-resolution SSC is given in

Figure 10. Hydrological condition in the YRE is very complex under the joint influence of runoff, tidal current, wind and human activities [

64], making it hard to accurately retrieve SSC. Since in-situ measurements methods such as buoy and ADCP has a limited observation range, previous research that studies SSC in the YRE generally utilize numerical model that requires reliable boundary condition and initial filed [

65,

66]. Therefore, by applying the TRMCC on GOCI-II TSM images, we retrieved SSC in the YRE via satellite images for the first time. Since the nature of the TRMCC is feature tracking, surface flow trajectories can be observed in Lagrange method rather than fix-point observation such as fixed-buoy which is Euler method. Firstly, tidal height in the YRE was simulated by tide model and compared with tidal height observed by three tide-gauge station, the result can be seen in

Figure 10b. The simulated tidal height agrees well with observed data, based on it, trajectories consist of nine consequential vectors in various location of the YRE are shown in

Figure 10a. Each vector was colored in red (Flood Period) and blue (Ebb Period) according to local tidal phase, and SSC characteristic in the YRE can be vividly depicted.

It can be indicated in

Figure 10a that SSC mainly shows a rotational flow style, with an elliptical trajectory in the outer estuary and gradually transformed into a reciprocal flow style. Moreover, since the observation time of GOCI-II have encompassed half of a tide period in the YRE, the responding mechanism between SSC and tide can also be interpreted based on these trajectories. In the inner estuary, during 8:00 to 11:00, north-westly current that flows into the YRE slowly decelerate and turning to south-east and flows to the outer sea, although tidal current already began ebbing in 9:00, it takes 2 hours of delay for the actual SSC to change its direction. From 11:00 to 15:00, south-eastly current gradually accelerate during ebb phase, and keeps accelerating from 15:00 to 17:00 when the tide began to rise. Overall, current in the estuary that is strongly influenced by runoff often postpones to response to the variation of tidal current, while in the outer estuary where the water is deeper, tidal variation mostly influence the current direction instead of velocity, in the whole observation period, current direction gradually changes from northwest to southeast.

Figure 10.

(a) SSC trajectories in YRE from 8:00 to 17:00 (UTC+8) on Jun 6, 2021. Color of trajectories represents the concurrent tidal phase, red and blue represents flood and ebb period, respectively. Stars represents location of tide-gauge stations. (b) Tidal height in the YRE on Jun 6, 2021. Black line represents average tidal height simulated by tide model, blue, red and green line represents tidal height measured by Sheshan, Chongming and Zhongjun tide-gauge station. Red and blue background represents the flood and ebb period decided by simulated tidal height.

Figure 10.

(a) SSC trajectories in YRE from 8:00 to 17:00 (UTC+8) on Jun 6, 2021. Color of trajectories represents the concurrent tidal phase, red and blue represents flood and ebb period, respectively. Stars represents location of tide-gauge stations. (b) Tidal height in the YRE on Jun 6, 2021. Black line represents average tidal height simulated by tide model, blue, red and green line represents tidal height measured by Sheshan, Chongming and Zhongjun tide-gauge station. Red and blue background represents the flood and ebb period decided by simulated tidal height.

4. Discussion

In this study, an improved MCC workflow called the TRMCC is proposed. By assimilating tidal current data, adaptive reference window size and Masked Normalized Cross-Correlation technique, TRMCC is able to retrieve high-resolution SSC in coastal sea area with a good accuracy, providing a new insight for SSC estimation in coastal area. The performance of the TRMCC was toughly examined by cross comparison with SSC data obtained by multiple methods in various spatial and temporal scale. On a long timescale, TRMCC remains a high accuracy in a total of 10,721 data pairs from 14 buoys located in Korean Seas and the YRE, with an average AME of 0.51 and AAE of 32.58° on average (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Surface current system such as Kuroshio, East Korea Warm Current and Korean Coastal Current can be depicted with a higher accuracy than CMEMS product (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), and the seasonal pattern of SSC were analyzed in Bohai Sea (

Figure 9). On a short timescale, TRMCC is capable of revealing SSC trajectories in a shallow estuary like the YRE during GOCI-II’s observation time (

Figure 10), SSC’s response to tidal current can also be analyzed by combining SSC results and simulated tidal height. In general, TRMCC exhibits a promising result in SSC estimation in coastal sea and estuary, but room for improvement still exists in various aspects.

In the process of Tide-Restriction, equation to calculate angular difference using tidal current magnitude was determined by statistical analysis, ensuring that 99% of genuine current can be covered in angular restriction range. The results shows that Tide-Restriction significantly improves the accuracy of SSC estimation in coastal sea, especially in the tide-dominated YRE where AME was improved by 21.7% and AAE by 52.2% on average. Tidal current data were independently pre-generated by FES2014 tide model, facilitating the process of the TRMCC workflow. However, though FES2014 has a proven accuracy in coastal sea due to its high horizontal resolution and fine shoreline grid, for estuaries with more complex land boundaries, error still exists in simulated tidal current. Therefore, in these areas, regional tidal model that can produce a more accurate tide data can be considered to replace FES2014 in the TRMCC workflow.

Besides from SSC estimation methods, previous studies have showed that erroneous vectors exist in SSC derived and are possible to be identified and eliminated by applying additional filter methods such as reciprocal filter [

51] and nearest neighbor filter [

12,

67]. Moreover, the performance of derived SSC can be further improved by applying optimization method such as optimal interpolation (OI) [

32,

68]. Since our research mainly focus on exploiting the potential of integrating tidal current into the process of SSC estimation, these filtering and reconstructing methods are not considered in this study.

When it comes to the selection of tracer images, GOCI-II can be the perfect candidate for its temporal resolution of one-hour, spatial resolution of 250 meters and its capability to acquire 10 images per day. But apart from GOCI-II, TRMCC’s application on other satellite images is not yet tested. Satellite with an even better temporal resolution such as Himawari-8 (20 minutes) and GF-4 (up to 20 seconds) can further reduce the influence caused by vertical exchange and mixing of surface tracer, thus provides a better SSC estimation. Moreover, as a sensor running in the geostationary orbit, GOCI-II’s observation range is limited to the western Pacific. In other regions, as long as two images have a short time interval, such as MODIS and VIIRS [

12], Landsat 8 and Sentinel 2 [

23], two different bands of Sentinel-2 that have inter-band time lag [

27], can also be selected as tracer images. Furthermore, tracer images are not limited to ocean color data, SAR images [

69], Sea Surface Temperature data [

68] or any other surface parameters that can reflect the displacement of surface water can be a potential tracer.

The SSC is an important physical property for understanding material exchange, biogeochemical processes and ocean-atmosphere interaction in estuaries and coastal areas. Conventional methods for deriving coastal SSC have their own limitation, such as in-situ observation methods like fixed-buoy and ADCP has a limited observation range, satellite altimeter are unreliable due to waveform contamination, and numerical model requires complex boundary condition and initial filed. Deriving SSC from sequential ocean color images offers a new approach that has lower computational costs and higher timeliness. Previous studies that utilize ocean color images such as Chl-a, TSM and Rrs obtained by GOCI, VIIRS and AVHRR, to derive SSC rarely involve estuary and coastal area, due to obstacles posed by intricate land boundaries and complex dynamic environments.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we propose an SSC estimation method called the TRMCC that can overcome the aforementioned obstacles and implemented it on ocean color data obtained from GOCI-II. Validation using in-situ current data obtained from 14 buoys located in different water areas from 2021 to 2023 showed that TRMCC is capable of deriving high-accuracy SSC even in turbid coastal areas, with an average AME of 0.51 and an AAE of 32.58°. Additionally, it was shown that estimation accuracy can be significantly improved by integrating tidal current data into the MCC process. Cross-comparisons were made between TRMCC results, HF Radar observations, CMEMS numerical model products, and buoy observations, showing that both large-scale surface circulation patterns and fine-scale current structures can be extracted by TRMCC. Seasonal SSC structure in the Bohai Sea and diurnal SSC variation in the YRE were depicted via satellite methods for the first time. By combining hourly ocean color data from GOCI-II, TRMCC can provide new insights into studying sea surface currents in highly turbid water areas with intricate land boundaries, expanding our understanding of complex physical processes in these regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and F.S.; methodology, S.C. and F.S.; software, S.C. and R.L.; validation, S.C., R.L. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, S.C. and R.L.; investigation, S.C.; resources, S.C. and R.L.; data curation, S.C. and R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C. and F.S.; writing—review and editing, S.C. and F.S.; visualization, S.C., R.L.; supervision, F.S.; project administration, F.S.; funding acquisition, F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No.42271348].

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Korea Ocean Satellite Center for providing satellite data, the Korea Hydrographic and Oceanographic Agency for providing buoy and High-frequency Radar data, the Archiving, Validation and Interpretation of Satellite Oceanographic for providing the FES2014 tide model, and the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service for providing the numerical model product.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Portela, E.; Kolodziejczyk, N.; Gorgues, T.; Zika, J.; Perruche, C.; Mignot, A. The Ocean’s Meridional Oxygen Transport. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 2024, 129, e2023JC020259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, D.; Kwon, Y.; Frankignoul, C.; Danabasoglu, G.; Yeager, S.; Kim, W.M. The Respective Roles of Ocean Heat Transport and Surface Heat Fluxes in Driving Arctic Ocean Warming and Sea Ice Decline. J. Clim. 2024, 37, 1431–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wang, N.; Zhou, L.; Yu, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y. Inversion of Tidal Flat Topography Based on the Optimised Inundation Frequency Method—A Case Study of Intertidal Zone in Haizhou Bay, China. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina-Alvarez, A.; Weidberg, N.; Aiken, C.; Navarrete, S. Larval transport in the upwelling ecosystem of central Chile: The effects of vertical migration, developmental time and coastal topography on recruitment. Prog. Oceanogr. 2018, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazoyer, C.; Vanneste, H.; Dufresne, C.; Ourmières, Y.; Magaldi, M.G.; Molcard, A. Impact of wind-driven circulation on contaminant dispersion in a semi-enclosed bay. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 2020, 233, 106529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, C.; Chen, W.; Gu, J.; He, L. Comprehensive analysis on the sediment siltation in the upper reach of the deepwater navigation channel in the Yangtze Estuary. J. Hydrodyn. 2014, 26, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzenreiter, K.; Mao, M.; Xia, M. Characteristics of Surface Currents in a Shallow Lagoon–Inlet–Coastal Ocean System Revealed by Surface Drifter Observations. Estuaries Coasts. 2022, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rypina, I.; Kirincich, A.; Peacock, T. Horizontal and vertical spreading of dye in the coastal ocean of the northern Mid-Atlantic bight. Cont. Shelf Res. 2021, 230, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, D.; Evans, M.; Weber, B. Ocean Surface Currents Mapped by Radar. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1977, 198, 138–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georges, T.M.; Harlan, J.A.; Lematta, R.A. Large-scale mapping of ocean surface currents with dual over-the-horizon radars. Nature 1996, 379, 434–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roarty, H.; Cook, T.; Hazard, L.; George, D.; Harlan, J.; Cosoli, S.; Wyatt, L.; Alvarez Fanjul, E.; Terrill, E.; Otero, M.; et al. The Global High Frequency Radar Network. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Emery, W.; Wu, X.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, L. Computing Coastal Ocean Surface Currents from MODIS and VIIRS Satellite Imagery. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W, J.E.; D., G.B.; D., K.M. Sampling the mesoscale ocean surface currents with various satellite altimeter configurations. Ieee Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing. 2004, 42, 795–803. [CrossRef]

- Carret, A.; Birol, F.; Estournès, C.; Zakardjian, B. Assessing the capability of three different altimetry satellite missions to observe the Northern Current by using a high-resolution model. Ocean Sci. 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio, M.; Santoleri, R.; Bourdalle-Badie, R.; Griffa, A.; Piterbarg, L.; Taburet, G. Improving the Altimeter-Derived Surface Currents Using High-Resolution Sea Surface Temperature Data: A Feasability Study Based on Model Outputs. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2016, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O.B.; Scharroo, R. Vignudelli, S., Kostianoy, A.G., Cipollini, P., Benveniste, J., Eds.; Range and Geophysical Corrections in Coastal Regions: And Implications for Mean Sea Surface Determination. In Coastal Altimetry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 103–451. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, F.; Deng, X.; Shen, Y. Assessment of Sentinel-6 SAR mode and reprocessed Jason-3 sea level measurements over global coastal oceans. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 311, 114287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, K.A. The influence of winds and topography on the sea surface temperature patterns over the northern California slope. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 1985, 90, 11783–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, W.J.; Thomas, A.C.; Collins, M.J.; Crawford, W.R.; Mackas, D.L. An objective method for computing advective surface velocities from sequential infrared satellite images. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 1986, 91, 12865–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, N.; Kida, S.; Sakuno, Y.; Mutsuda, H.; Syamsudin, F. Short-Term Variation of the Surface Flow Pattern South of Lombok Strait Observed from the Himawari-8 Sea Surface Temperature. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Arnone, R.; Jolliff, J. Estimating advective near-surface currents from ocean color satellite images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 158, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y, R.; X., M.L.; G., G.; T., E.B. Derivation of Sea Surface Tidal Current From Spaceborne SAR Constellation Data. Ieee Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing. 2017, 55, 3236–47. [CrossRef]

- Osadchiev, A.; Sedakov, R. Spreading dynamics of small river plumes off the northeastern coast of the Black Sea observed by Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 221, 522–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, D.L.; Negahdaripour, S. Implementation of the Optical Flow to Estimate the Propagation of Eddies in the South Atlantic Ocean. Remote Sensing, Vol. 15, 2023.

- Moiseev, A.; Johnsen, H.; Hansen, M.W.; Johannessen, J.A. Evaluation of Radial Ocean Surface Currents Derived From Sentinel-1 IW Doppler Shift Using Coastal Radar and Lagrangian Surface Drifter Observations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 2020, 125, e2019JC015743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseev, A.; Johnsen, H.; Johannessen, J.A.; Collard, F.; Guitton, G. On Removal of Sea State Contribution to Sentinel-1 Doppler Shift for Retrieving Reliable Ocean Surface Current. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 2020, 125, e2020JC016288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurovskaya, M.; Kudryavtsev, V.; Chapron, B.; Collard, F. Ocean surface current retrieval from space: The Sentinel-2 multispectral capabilities. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 234, 111468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. Surface Velocity Estimation From Satellite Imagery Using Displaced Frame Central Difference Equation. Ieee Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing. 2012, 50, 2791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Choi, J.; Park, Y.; Han, H.; Ryu, J. Application of the Geostationary Ocean Color Imager (GOCI) to estimates of ocean surface currents. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 2014, 119, 3988–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L, J.; M., W. Diurnal Currents in the Bohai Sea Derived From the Korean Geostationary Ocean Color Imager. Ieee Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing. 2017, 55, 1437–50. [CrossRef]

- Z, H.; H., Z.; D., W. A Novel Approach for Estimating Sea Surface Currents From Numerical Models and Satellite Images: Validation and Application. Ieee Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing. 2024, 62, 1–8.

- Liu, J.; Emery, W.J.; Wu, X.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Zhang, L. Computing Ocean Surface Currents From GOCI Ocean Color Satellite Imagery. Ieee Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing. 2017, 55, 7113–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; He, Q.; Wang, Z.; Weltje, G.J.; Zhang, J. Dynamics and spatial variability of near-bottom sediment exchange in the Yangtze Estuary, China. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2010, 86, 322–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Chen, S.; Yan, X.; Bai, Y.; Bu, J. Study on High-Resolution Suspended Sediment Distribution under the Influence of Coastal Zone Engineering in the Yangtze River Mouth, China. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, D.; Hart, D.E. Tidal current classification insights for search, rescue and recovery operations in the Yellow and East China Seas and Korea Strait. Cont. Shelf Res. 2022, 232, 104632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, D.; Hart, D.E. Tidal current classification insights for search, rescue and recovery operations in the Yellow and East China Seas and Korea Strait. Cont. Shelf Res. 2022, 232, 104632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Savenije, H.H.G.; Wu, H.; Kong, Y.; Zhu, J. Analytical solution for salt intrusion in the Yangtze Estuary, China. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2011, 91, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, R.I.; Matthews, D.K.; Emery, W.J.; Baldwin, D.G. Computing Coastal Ocean Surface Currents From Infrared and Ocean Color Satellite Imagery. Ieee Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing. 2007, 45, 435–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.A.; Quartly, G.D.; Shutler, J.D.; Miller, P.I.; Yoshikawa, Y. Estimation of ocean surface currents from maximum cross correlation applied to GOCI geostationary satellite remote sensing data over the Tsushima (Korea) Straits. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 2016, 121, 6993–7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Lee, Z.; Franz, B. Chlorophyll aalgorithms for oligotrophic oceans: A novel approach based on three-band reflectance difference. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Zhou, Y.; Li, D.; Zhu, W.; Suhyb Salama, M. Medium resolution imaging spectrometer (MERIS) estimation of chlorophyll-a concentration in the turbid sediment-laden waters of the Changjiang (Yangtze) Estuary. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 4635–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Yu, M.; Yan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, S. HY-1C/D Reveals the Chlorophyll-a Concentration Distribution Details in the Intensive Islands’ Waters and Its Consistency with the Distribution of Fish Spawning Ground. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Pan, D.; He, X.; Bai, Y. Diurnal Variability of Turbidity Fronts Observed by Geostationary Satellite Ocean Color Remote Sensing. Remote Sensing (Basel, Switzerland). 2016, 8, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, D.P.; Pan, D.; He, X.; Miyazawa, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, D.; Gong, F. Mapping surface tidal currents and Changjiang plume in the East China Sea from Geostationary Ocean Color Imager. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 2016, 121, 1563–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yin, W.; Guo, Z.; Xuan, J. The Ocean Surface Current in the East China Sea Computed by the Geostationary Ocean Color Imager Satellite. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Pan, D.; Bai, Y.; Gong, F. A general purpose exact Rayleigh scattering look-up table for ocean color remote sensing. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2006, 25, 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Bai, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Gong, F. A vector radiative transfer model of coupled ocean–atmosphere system using matrix-operator method for rough sea-surface. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer. 2010, 111, 1426–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; He, M.; He, S.; He, S.; Pan, Y.; Wenbin, Y.; Li, P. An Improved Cloud Masking Method for GOCI Data over Turbid Coastal Waters. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Shen, F.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, S. Identification and Diurnal Variation of Algal Bloom Types Using Goci-Ii Data.

- Shen, F.; Verhoef, W.; Zhou, Y.; Salama, M.; Liu, X. Satellite Estimates of Wide-Range Suspended Sediment Concentrations in Changjiang (Yangtze) Estuary Using MERIS Data. Estuaries and Coasts 33 ( 2010) 6. 2010, 33. [CrossRef]

- Barton, I.J. Ocean Currents from Successive Satellite Images: The Reciprocal Filtering Technique. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2002, 19, 1677–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Heron, M.L.; Kim, K.; Lai, J.; Lee, S.; Wu, X.; Wu, X.; Wyatt, L.R.; Yang, W. An overview of developments and applications of oceanographic radar networks in Asia and Oceania countries. Ocean Sci. J. 2013, 48, 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Arcilla, A.; Staneva, J.; Cavaleri, L.; Badger, M.; Bidlot, J.; Sorensen, J.T.; Hansen, L.B.; Martin, A.; Saulter, A.; Espino, M.; et al. CMEMS-Based Coastal Analyses: Conditioning, Coupling and Limits for Applications. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirooznia, M.; Raoofian Naeeni, M.; Tourian, M.J. Modeling total surface current in the Persian Gulf and the Oman Sea by combination of geodetic and hydrographic observations and assimilation with in situ current meter data. Acta Geophys. 2023, 71, 2839–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lellouche, J.; Greiner, E.; Galloudec, O.; Garric, G.; Regnier, C.; Drevillon, M.; Mounir, B.; Testut, C.; Bourdalle-Badie, R.; Gasparin, F.; et al. Recent updates to the Copernicus Marine Service global ocean monitoring and forecasting real-time 1/12∘ high-resolution system. Ocean Sci. 2018, 14, 1093–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyard, F.H.; Allain, D.J.; Cancet, M.; Carrere, L.; Picot, N. FES2014 global ocean tide atlas: design and performance. Ocean Sci. 2021, 17, 615–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Tang, Q. Accuracy assessment of global ocean tide models in the South China Sea using satellite altimeter and tide gauge data. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Gao, Y.; Guo, H.; Lu, J. Analysis of Characteristics of Tide and Tidal Current in the east China Seas. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2486, 12039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Lee, M. Effect of Open Boundary Conditions and Bottom Roughness on Tidal Modeling around the West Coast of Korea. Water. 2020, 12, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padfield, D. Masked Object Registration in the Fourier Domain. Ieee Transactions On Image Processing: A Publication of the Ieee Signal Processing Society 2011, 21, 2706–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Pan, D.; He, X.; Song, D.; Huang, N.; Bai, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Gong, F. Assessment of the MCC method to estimate sea surface currents in highly turbid coastal waters from GOCI. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 572–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Mied, R.P.; Gao, B.; Wagner, E. Surface Velocities From Multiple-Tracer Image Sequences. Ieee Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2012, 9, 769–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Chen, J.; Cao, Z.; Huang, H.; Gong, F. A Novel Multi-Candidate Multi-Correlation Coefficient Algorithm for GOCI-Derived Sea-Surface Current Vector with OSU Tidal Model. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Chen, S.; Yan, X.; Bai, Y.; Bu, J. Study on High-Resolution Suspended Sediment Distribution under the Influence of Coastal Zone Engineering in the Yangtze River Mouth, China. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Ding, P.; Chen, C.; Hu, S.; Fu, G.; Wu, L. An integrated East China Sea–Changjiang Estuary model system with aim at resolving multi-scale regional–shelf–estuarine dynamics. Ocean Dyn. 2013, 63, 881–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Ge, J. Long-term response of an estuarine ecosystem to drastic nutrients changes in the Changjiang River during the last 59 years: A modeling perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarstefano, G.; Poulain, P.; Mauri, E. Estimation of Surface Currents in the Adriatic Sea from Sequential Infrared Satellite Images. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2008, 25, 271–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F, Y.; Z., H.; D., P. An Optimization Method Based on Decorrelation Scales Analysis for Improving Surface Currents Retrieval From Sea Surface Temperature. Ieee Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing. 2024, 62, 1–17.

- W, A.Q.; W., J.E.; B., F. Computing Ocean Surface Currents Over the Coastal California Current System Using 30-Min-Lag Sequential SAR Images. Ieee Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing. 2014, 52, 7559–80. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).