Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

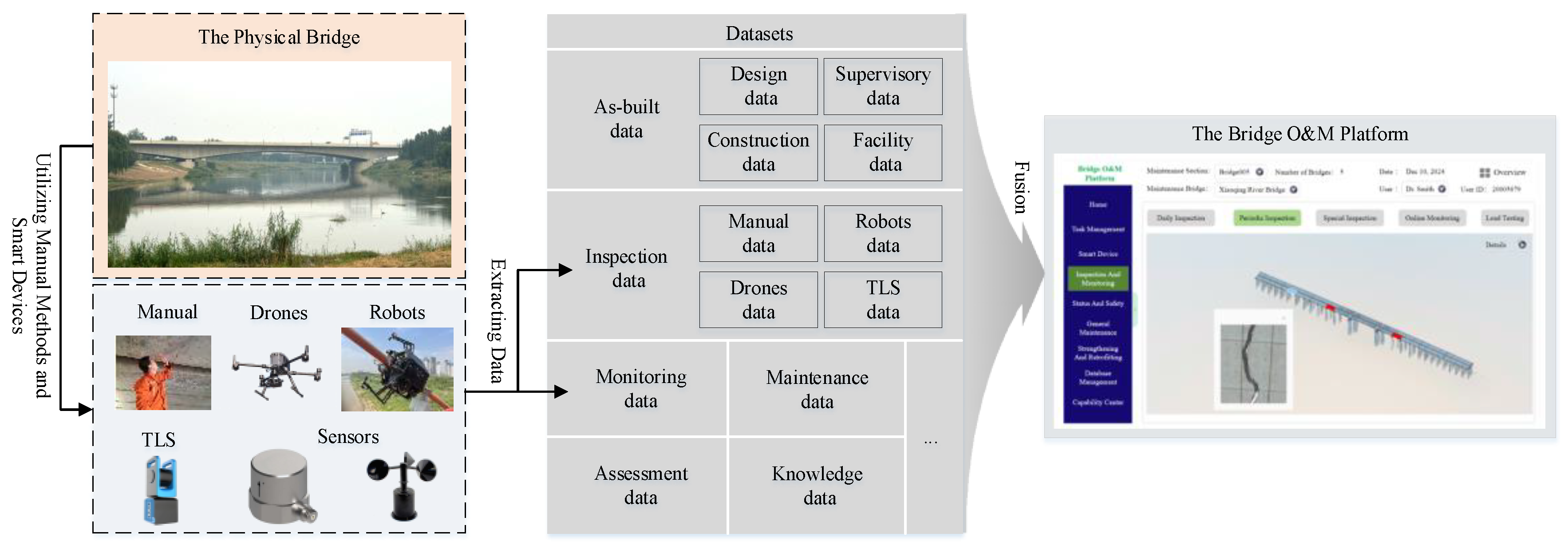

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Digital Twin

2.2. IFC and COBie

2.2.1. IFC

2.2.2. COBie

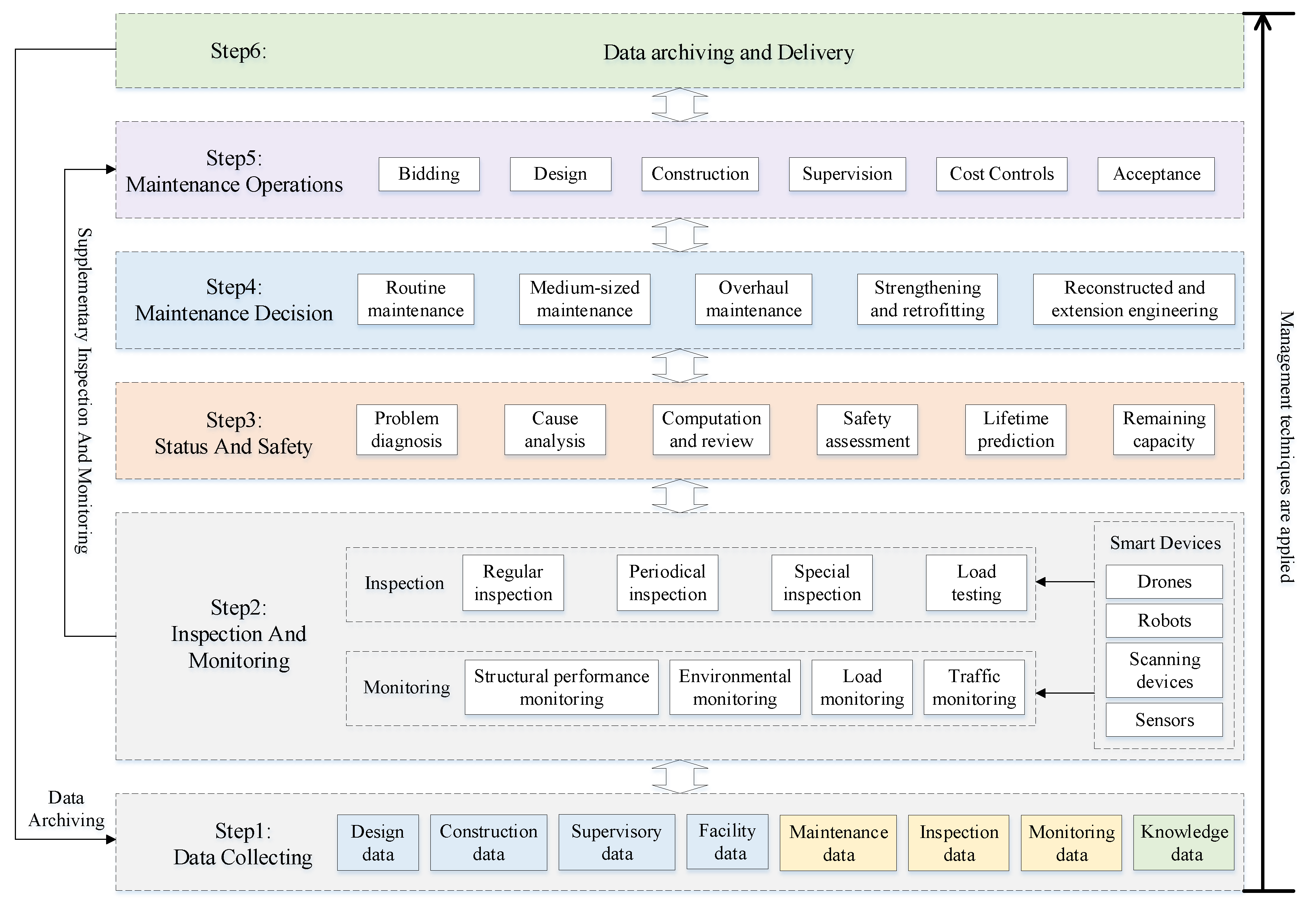

3. The Architecture for the Platform

3.1. The Maintenance Workflow

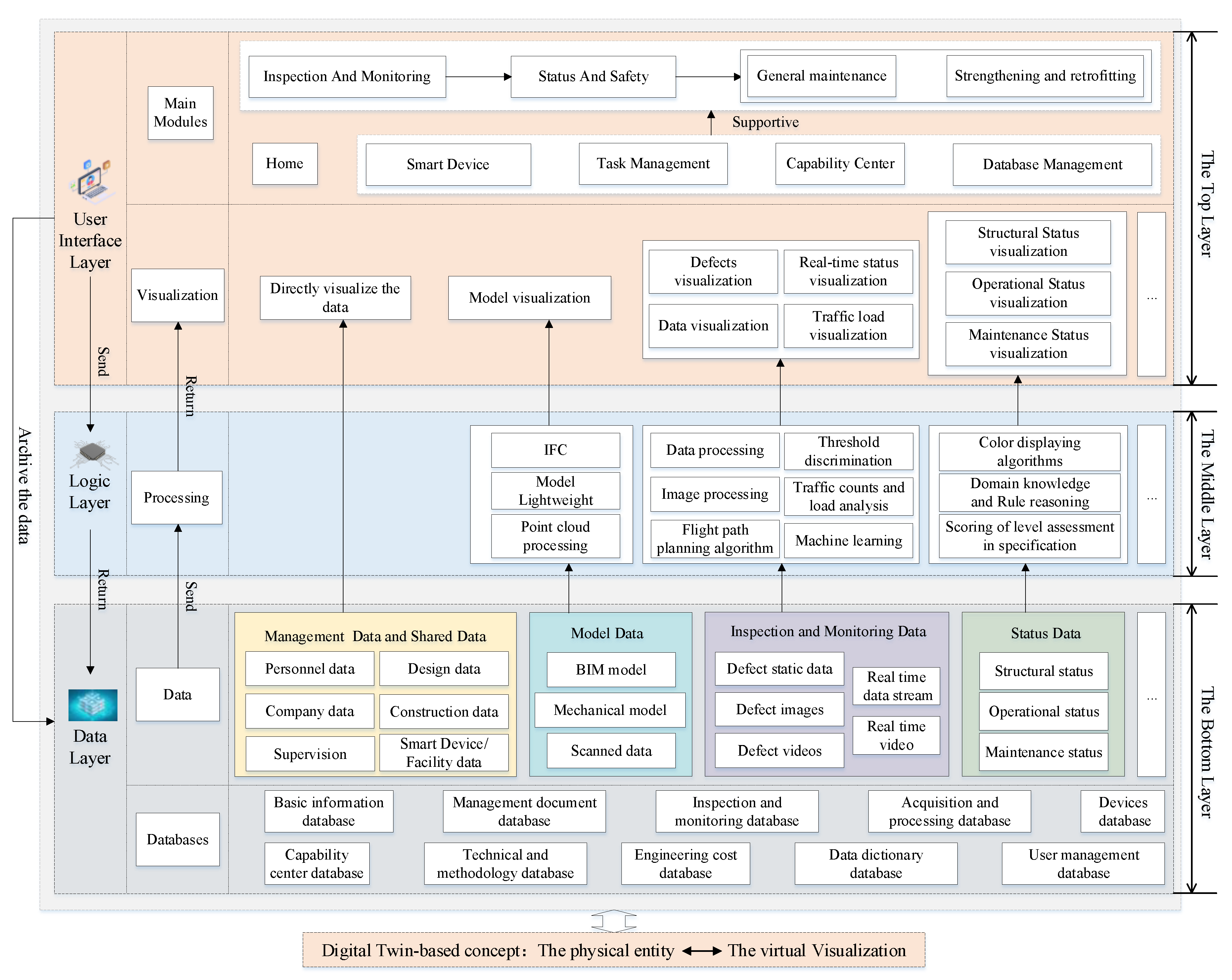

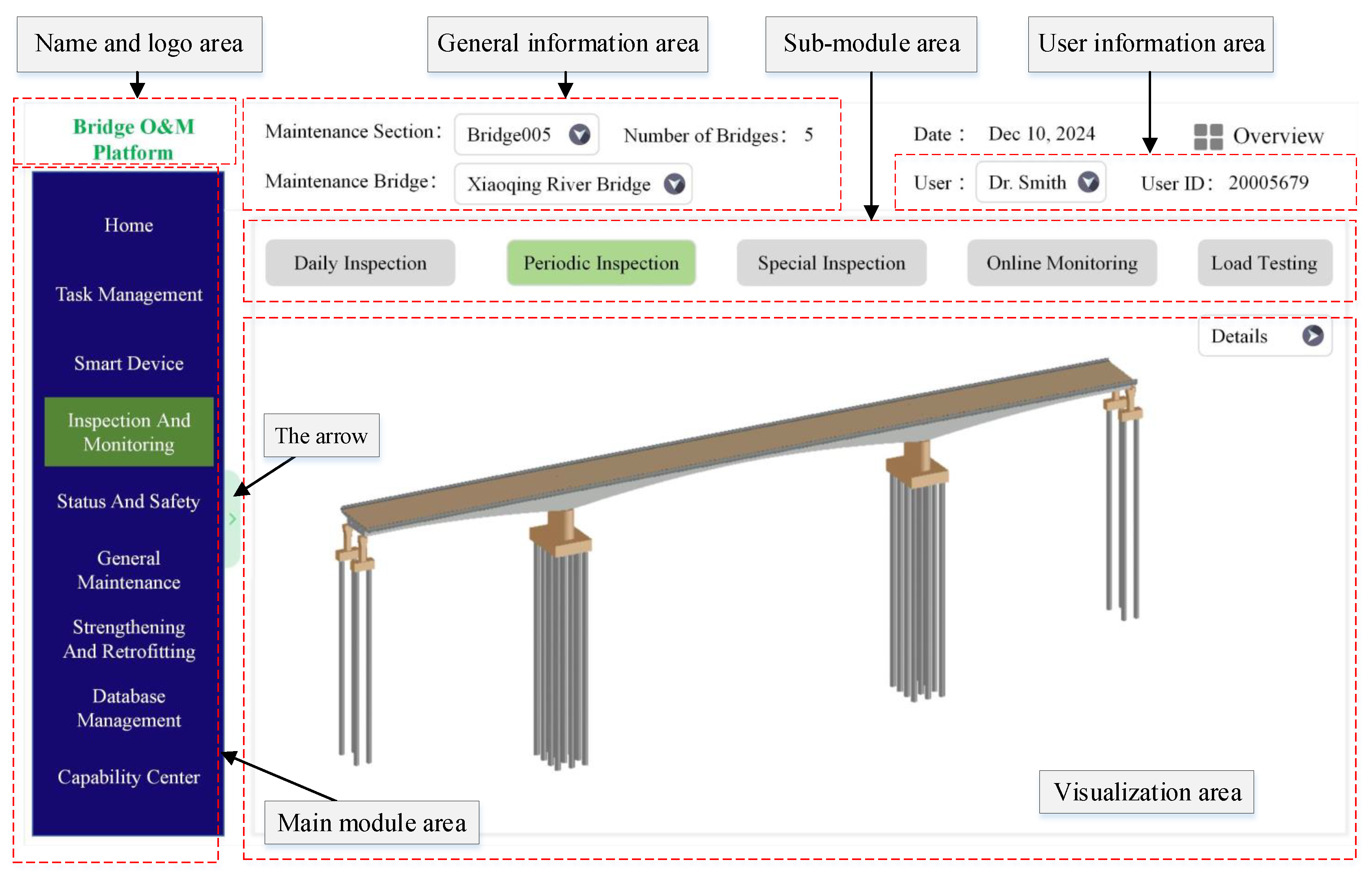

3.2. The Architecture, Data Processing and Visualization, and Front-End Modules for the Platform

3.2.1. The Three-Layer Architecture

3.2.2. Data Processing and Visualization

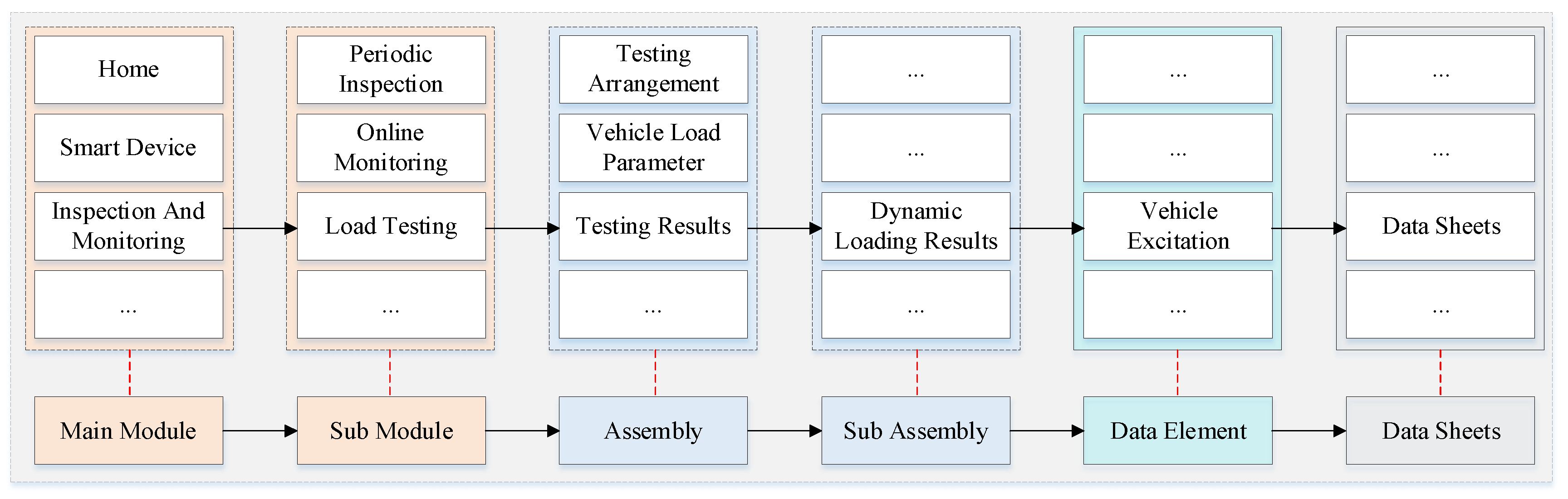

3.2.3. The Hierarchical Structure of the Front-End Modules

4. The Data Structure for the Platform

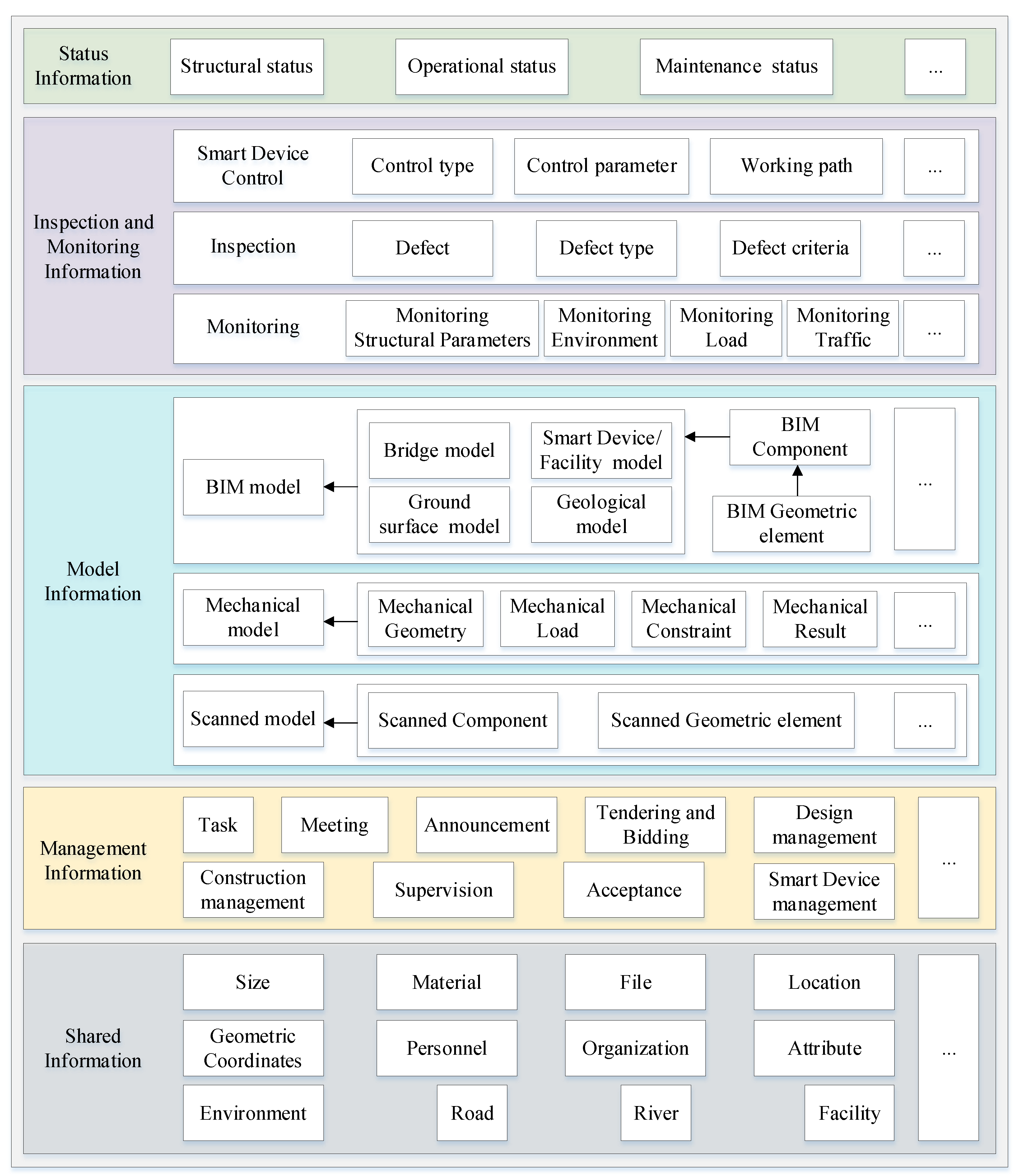

4.1. The Classification of the Data

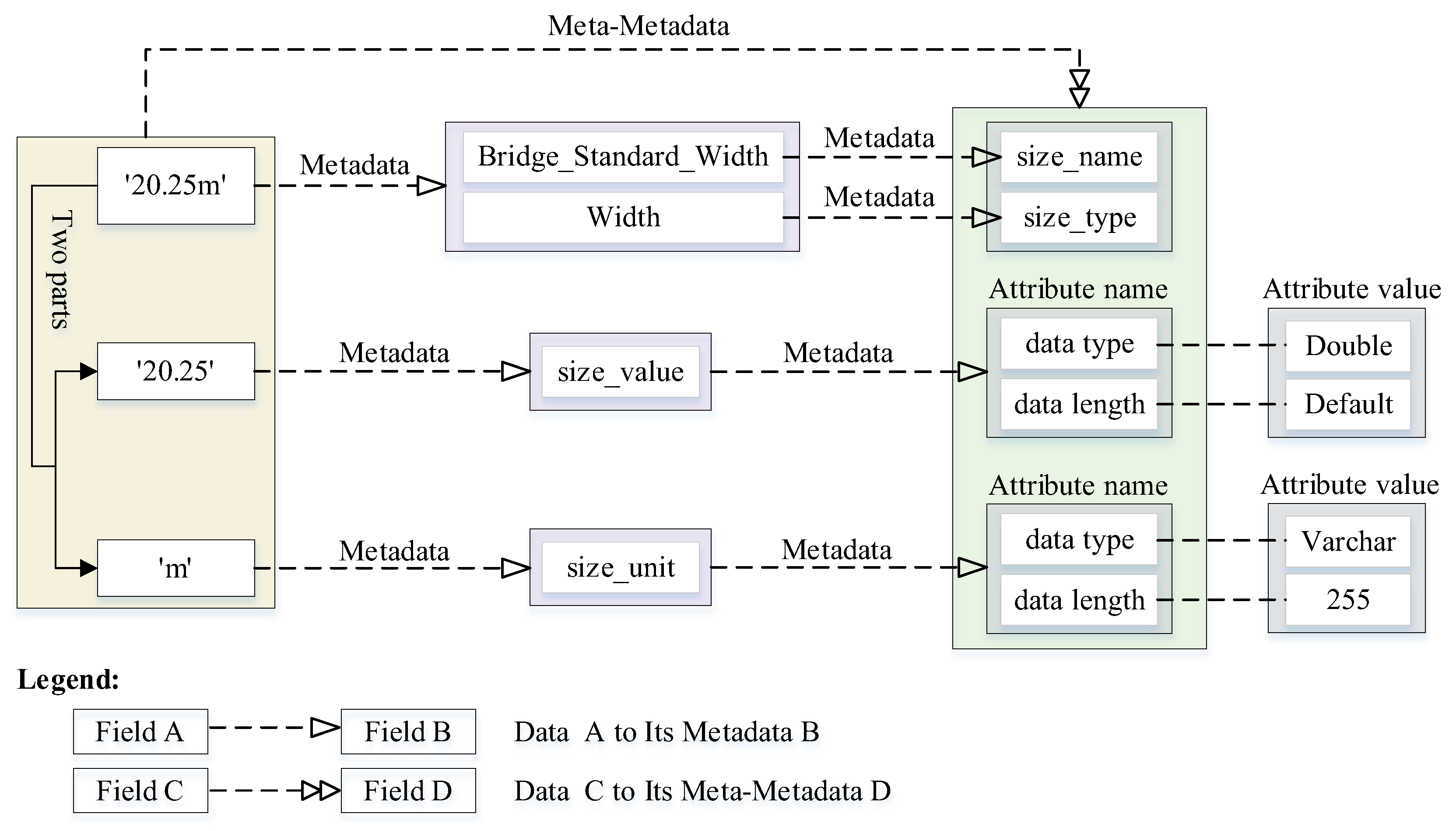

4.2. The Organization of the Data Structure

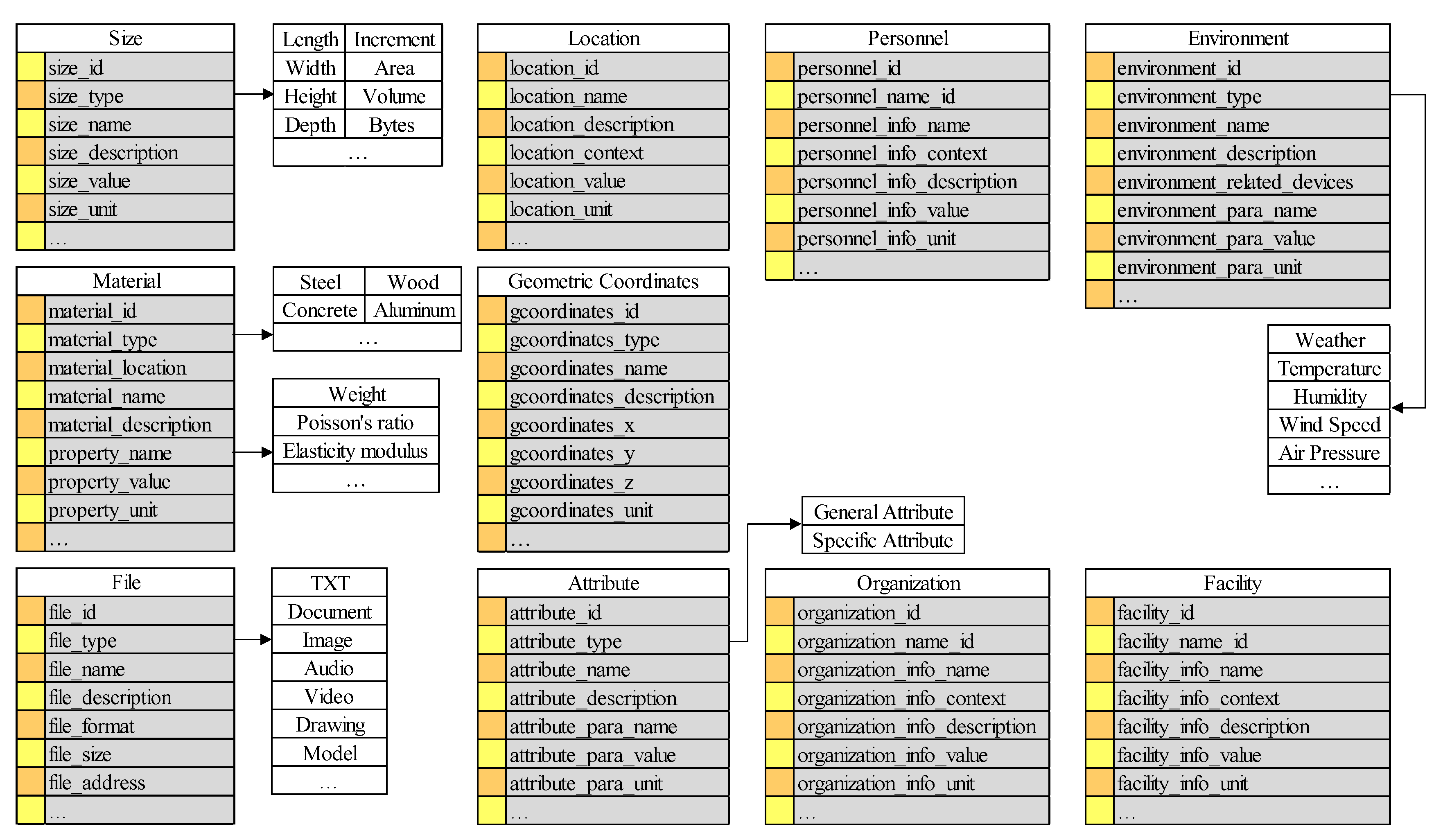

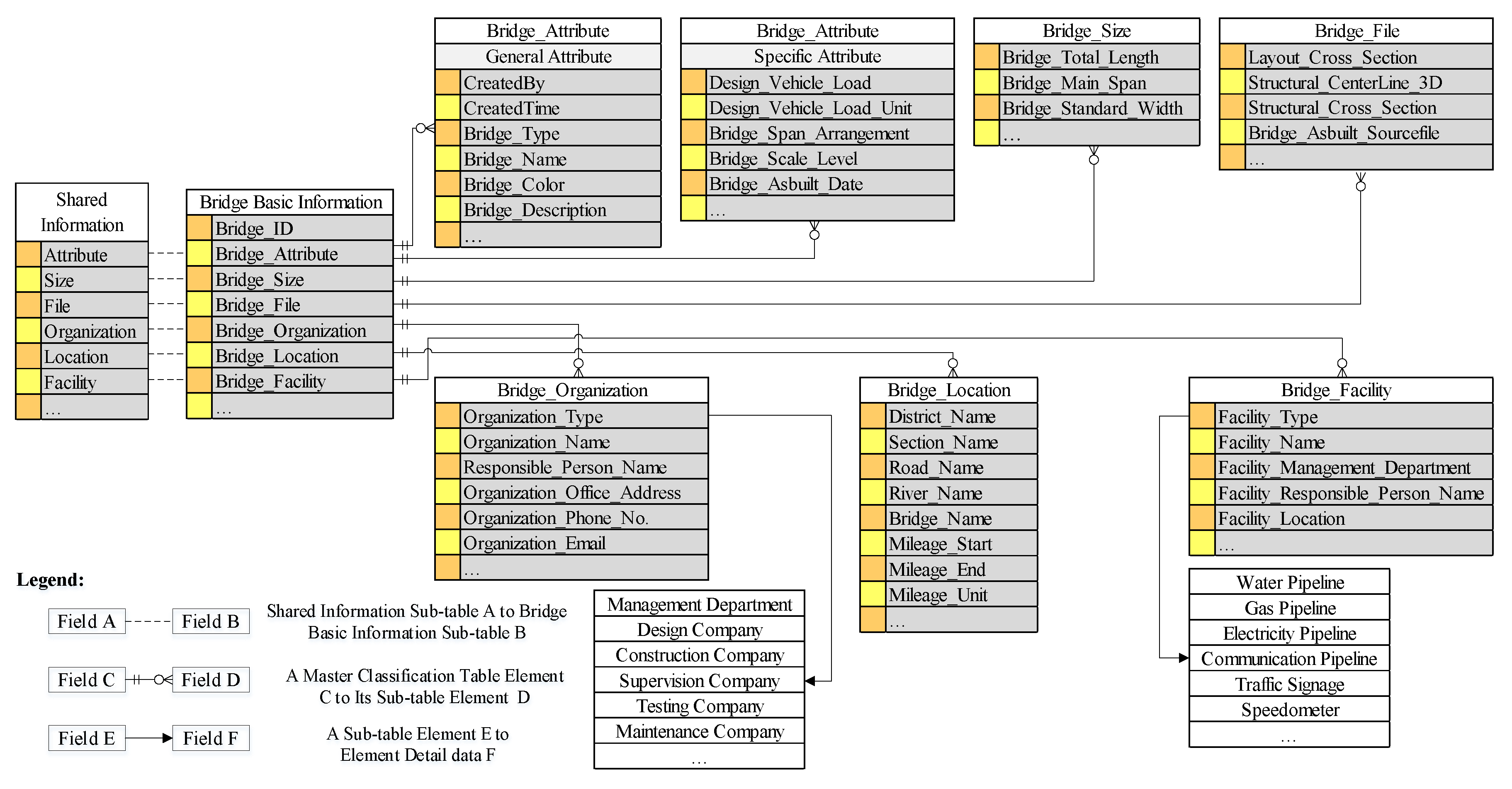

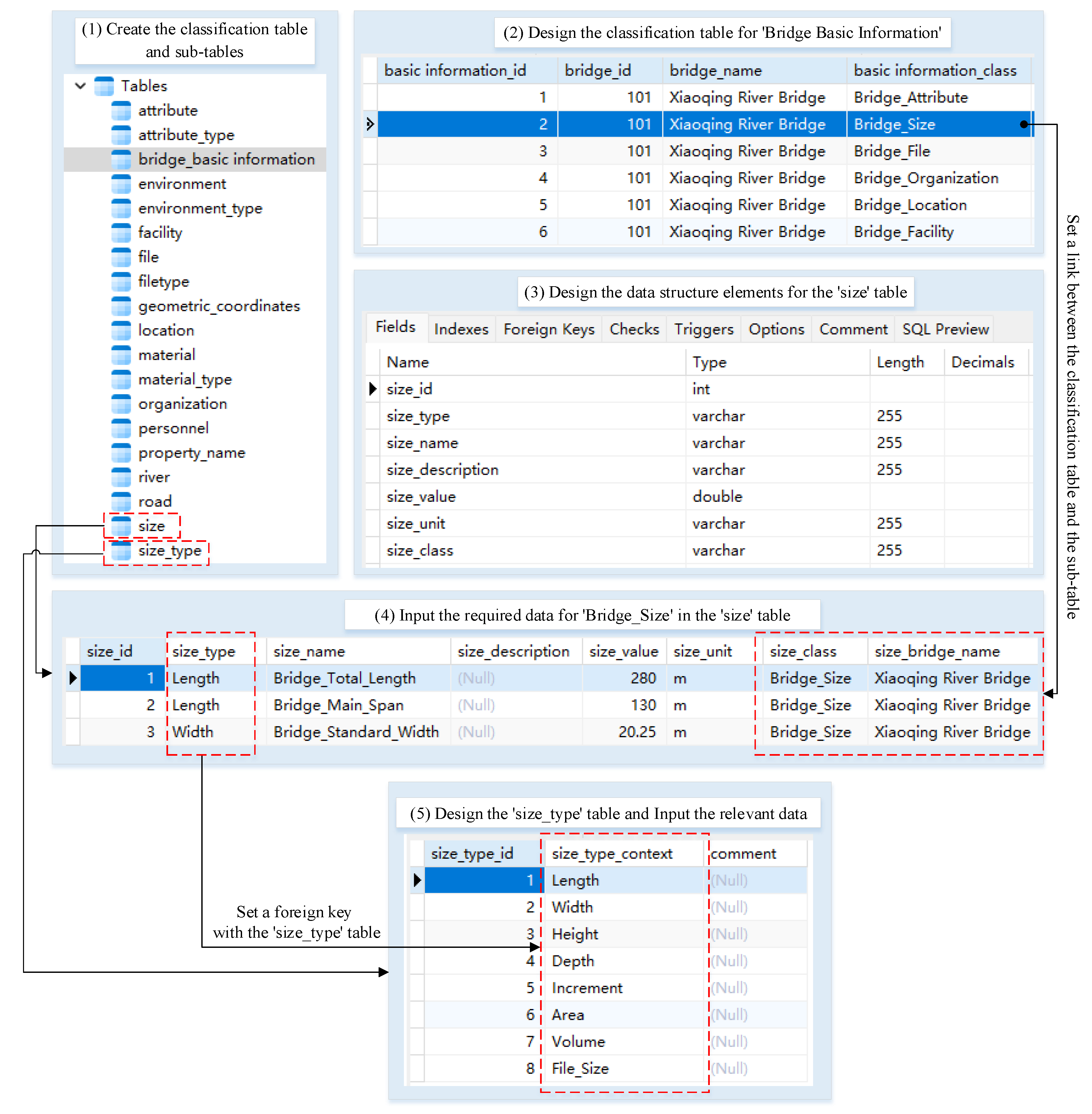

4.2.1. The Data Structure of Shared Information

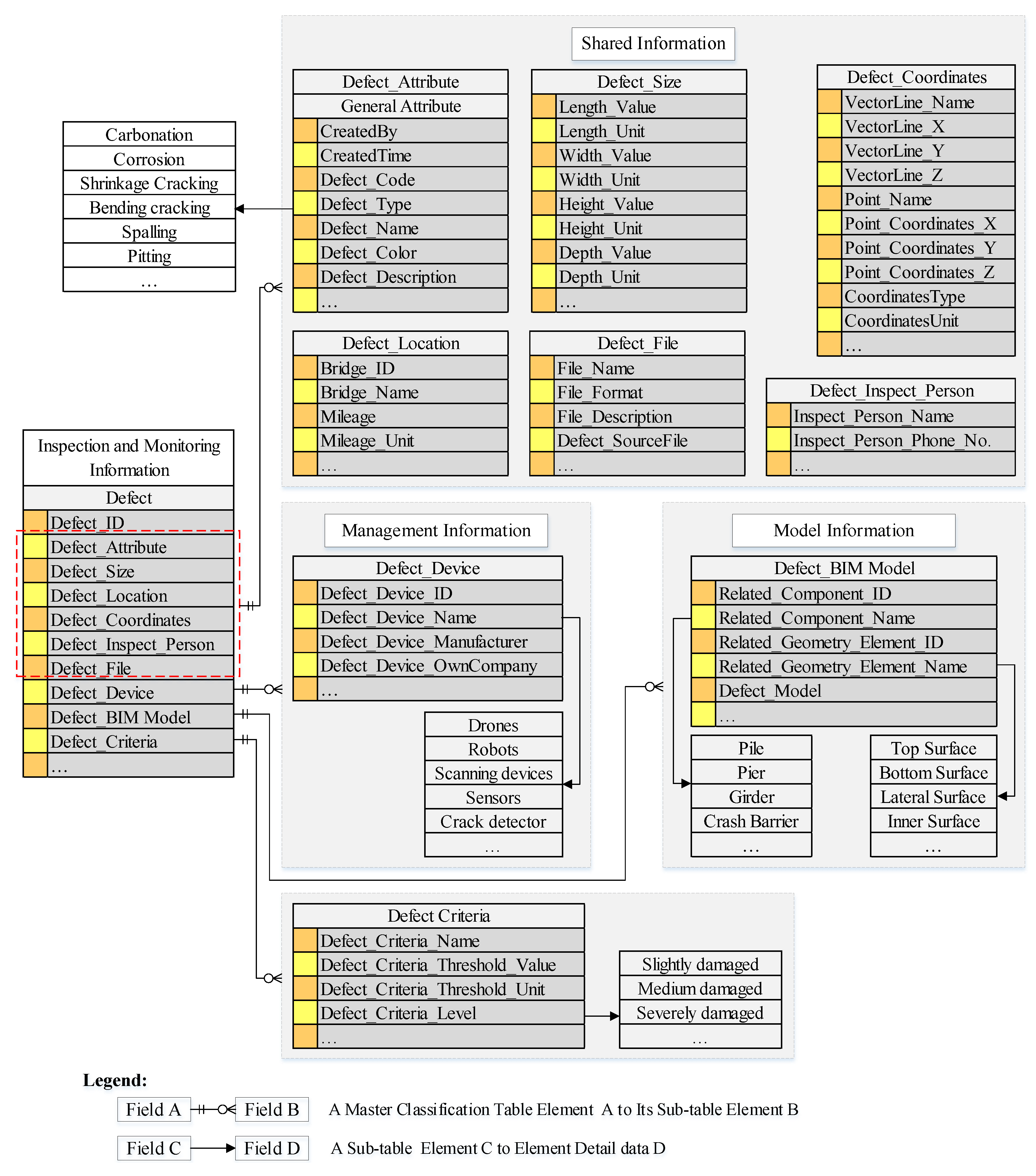

4.2.2. The Data Structure of the Defect

5. Case Study

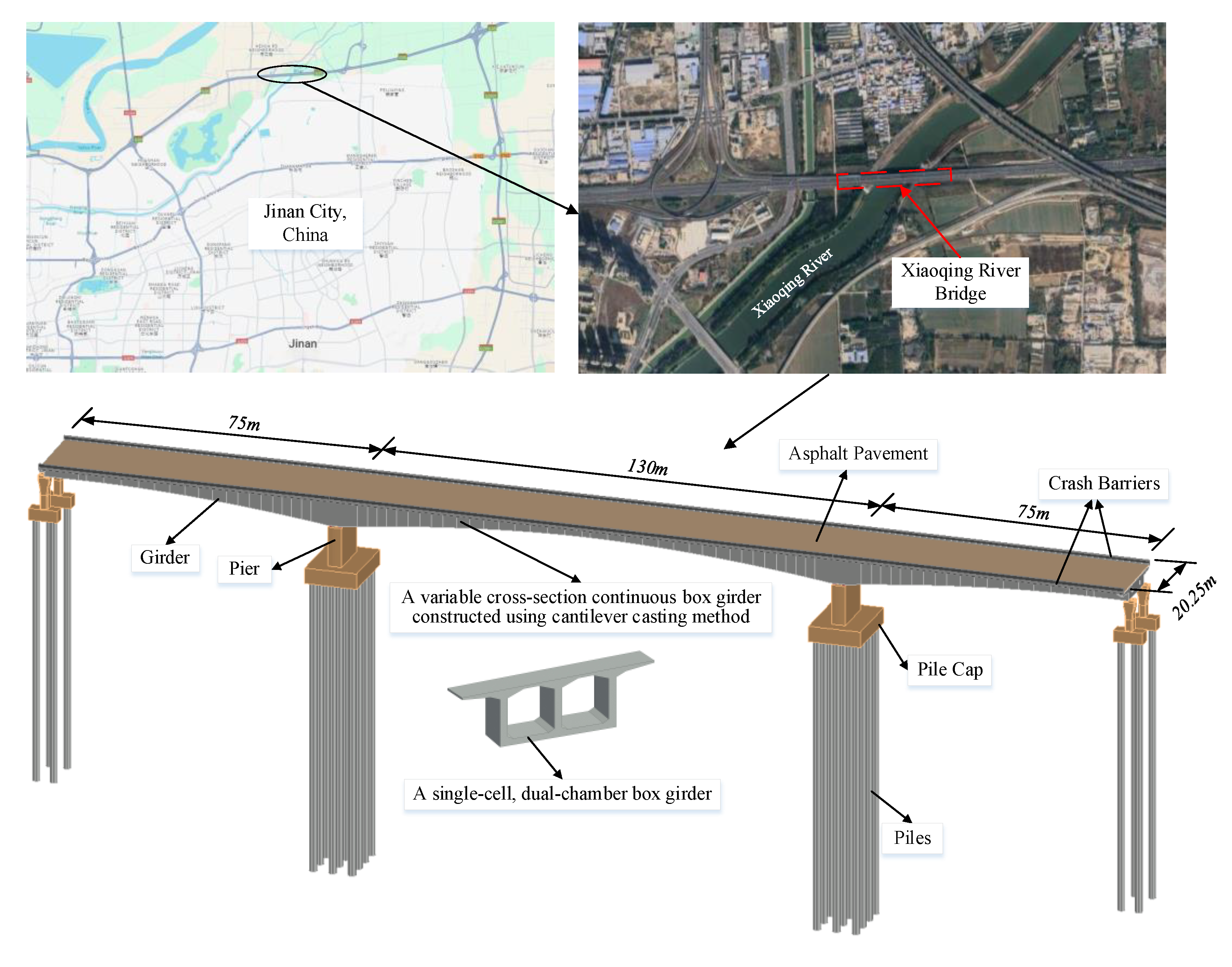

5.1. General Information About the Bridge

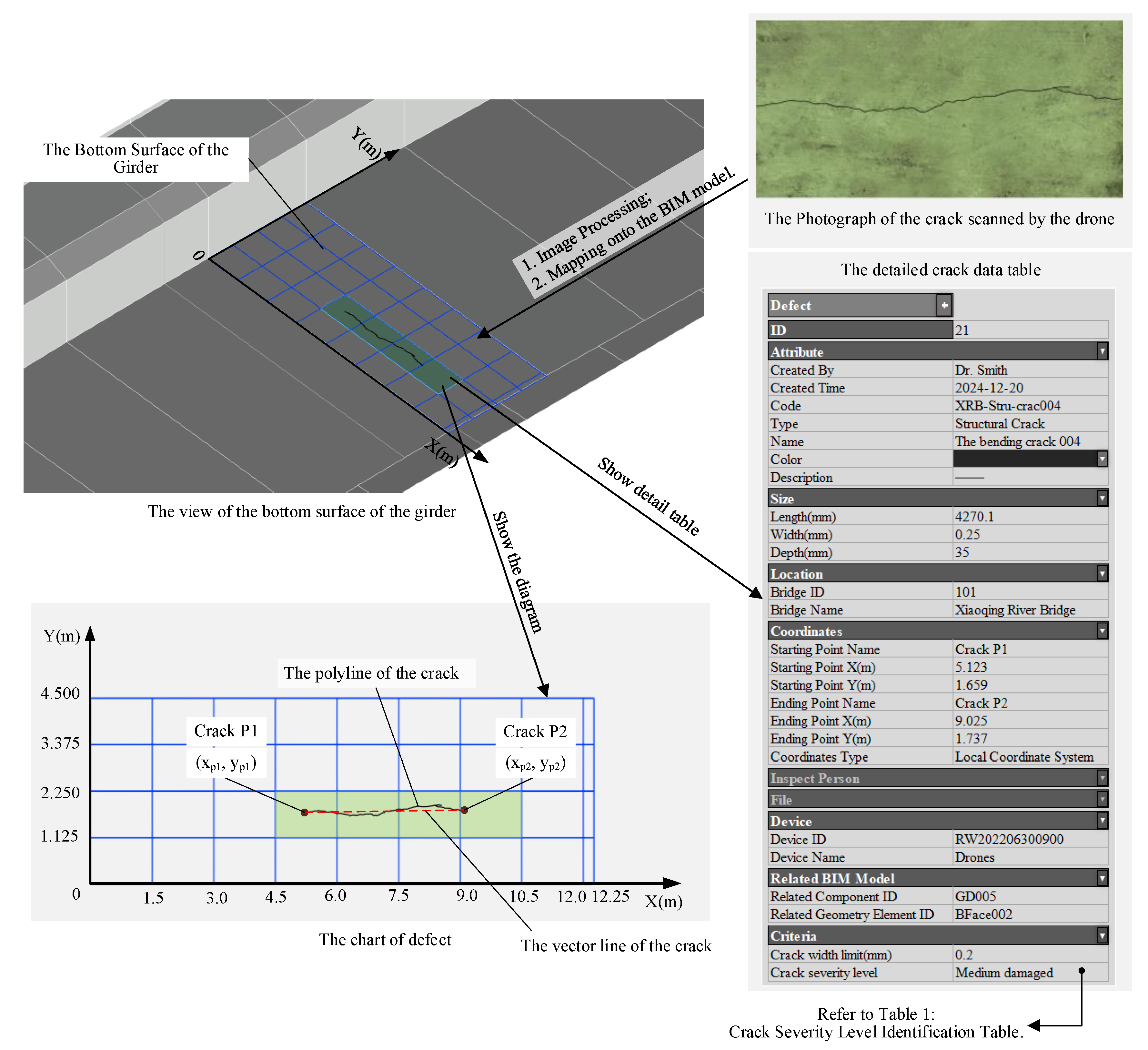

5.2. The Details of the Bridge Crack

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Kang, J. S.; Chung, K.; Hong, E. J. , Multimedia knowledge-based bridge health monitoring using digital twin. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2021, 80, (26–27), 34609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Mo, T. J.; Yang, J. X.; Jiang, S. X.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. M. , Ontologies-Based Domain Knowledge Modeling and Heterogeneous Sensor Data Integration for Bridge Health Monitoring Systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2021, 17, (1), 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X. L.; Yang, H. L.; Wang, L. B.; Miao, Y. H. , The Development and Field Evaluation of an IoT System of Low-Power Vibration for Bridge Health Monitoring. Sensors 2019, 19, (5), 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, H. J.; Xiong, G. Y.; Song, H. H. , AIoT-informed digital twin communication for bridge maintenance. Automation in Construction 2023, 150, 104835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, C. S.; Dang, N. S.; Lon, S.; Jeon, C. H. , Development of a bridge maintenance system for prestressed concrete bridges using 3D digital twin model. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering 2019, 15, (10), 1319–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, C. S.; Jeon, C. H.; Kang, H. R.; Dang, N. S.; Lon, S. , Definition of Digital Twin Models for Prediction of Future Performance of Bridges. KIBIM Magazine 2018, 8, (4), 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Z. J.; Lin, D. M.; Zhang, T. R.; Han, L. , Development of a BIM-based bridge maintenance system (BMS) for managing defect data. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, (1), 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, C. H.; Shim, C. S.; Lee, Y. H.; Schooling, J. , Prescriptive maintenance of prestressed concrete bridges considering digital twin and key performance indicator. Engineering Structures 2024, 302, 117383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, Z. Q.; Wang, J.; Tian, J. B.; Wang, J. , A Cloud Platform for Bridge Health Monitoring Based on BIM plus GIS. CICTP 2020: Advanced Transportation Technologies and Development-Enhancing Connections, 1507. [Google Scholar]

- 006 1-2 Research on Web-based Technology for Finite Element Modelling and Result Visualisation Methods.pdf.

- Bao, J. S.; Guo, D. S.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. , The modelling and operations for the digital twin in the context of manufacturing. Enterprise Information Systems 2019, 13, (4), 534–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Z.; Mahadevan, S.; Ling, Y.; Choze, S.; Wang, L. P. , Dynamic Bayesian Network for Aircraft Wing Health Monitoring Digital Twin. AIAA Journal 2017, 55, (3), 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L. F.; Ren, W. X.; Guo, C. R. , A Physics-Data Hybrid Framework to Develop Bridge Digital Twin Model in Structural Health Monitoring. International Journal of Structural Stability and Dynamics 2023, 23, (16N18), 2340037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ding, Y. L.; Song, Y. S.; Geng, F. F.; Wang, Z. W. , An architecture of lifecycle fatigue management of steel bridges driven by Digital Twin. Struct Monit Maint 2021, 8, (2), 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski, M.; Lazinski, P.; Piotrowski, D. , The Concept of Creating Digital Twins of Bridges Using Load Tests. Sensors 2023, 23, (17), 7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X. Y.; Fang, S. E. , Digital twin based lifecycle modeling and state evaluation of cable-stayed bridges. Eng. Comput. 2024, 40, (2), 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, R.; Blyth, A.; Glisic, B. , Virtual Environments for Visualizing Structural Health Monitoring Sensor Networks, Data, and Metadata. Sensors 2018, 18, (1), 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tita, E. E.; Watanabe, G.; Shao, P. L.; Arii, K. , Development and Application of Digital Twin-BIM Technology for Bridge Management. Appl Sci-Basel 2023, 13, (13), 7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. C.; Nguyen, T. Q.; Jin, R. Y.; Jeon, C. H.; Shim, C. S. , BIM-based mixed-reality application for bridge inspection and maintenance. Constr Innov-Engl 2022, 22, (3), 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, A.; Amir, Z.; Salman, B.; Sanaei, P.; Lojano-Quispe, E.; Maher, A.; Schaefer, R. , A Digital Twin Framework for Bridges. Computing in Civil Engineering 2023-Visualization, Information Modeling, and Simulation.

- Schatz, Y.; Domer, B. , Semi-automated creation of IFC bridge models from point clouds for maintenance applications. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 1375873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafipour, M. S.; Vilgertshofer, S.; Borrmann, A. , Automated geometric digital twinning of bridges from segmented point clouds by parametric prototype models. Automation in Construction 2023, 156, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Rashidi, M.; Mousavi, V.; Karami, A.; Yu, Y.; Samali, B. , Quality Evaluation of Digital Twins Generated Based on UAV Photogrammetry and TLS: Bridge Case Study. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, (17), 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y. H.; Yau, N. J.; Tabor, J. M. M. , A Big Data Approach for Investigating Bridge Deterioration and Maintenance Strategies in Taiwan. Sustainability 2023, 15, (2), 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsialiamanis, G.; Wagg, D. J.; Dervilis, N.; Worden, K. , On generative models as the basis for digital twins. Data-Centric Eng. 2021, 2, (e11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, G. F.; Liang, Z. Q.; Hu, Y. R.; Long, G. X.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, P. , Modeling the Optimal Maintenance Strategy for Bridge Elements Based on Agent Sequential Decision Making. Appl Sci-Basel 2024, 14, (1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewunruen, S.; Sresakoolchai, J.; Ma, W. T.; Phil-Ebosie, O. , Digital Twin Aided Vulnerability Assessment and Risk-Based Maintenance Planning of Bridge Infrastructures Exposed to Extreme Conditions. Sustainability 2021, 13, (4), 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z. J.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, C. P.; Zhang, Z. M.; Li, W.; Wang, X. J.; Wang, L.; Wang, L. B. , A digital twin approach for tunnel construction safety early warning and management. Comput. Ind. 2023, 144, 103783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futai, M. M.; Bittencourt, T. N.; Carvalho, H.; Ribeiro, D. M. , Challenges in the application of digital transformation to inspection and maintenance of bridges. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering 2022, 18, (10–11), 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauwels, P.; Zhang, S. J.; Lee, Y. C. , Semantic web technologies in AEC industry: A literature overview. Automation in Construction 2017, 73, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boje, C.; Guerriero, A.; Kubicki, S.; Rezgui, Y. , Towards a semantic Construction Digital Twin: Directions for future research. Automation in Construction 2020, 114, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H. H.; Yang, G.; Li, H. J.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, A. N. , Digital twin enhanced BIM to shape full life cycle digital transformation for bridge engineering. Automation in Construction 2023, 147, 104736. [Google Scholar]

- Rios, A. J.; Plevris, V.; Nogal, M. , Bridge management through digital twin-based anomaly detection systems: A systematic review. Front. Built Environ. 2023, 9, 1176621. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, V.; Rashidi, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Samali, B. , Evolution of Digital Twin Frameworks in Bridge Management: Review and Future Directions. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, (11), 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. I.; Park, J.; Kim, B. G.; Lee, S. H. , Improving Applicability for Information Model of an IFC-Based Steel Bridge in the Design Phase Using Functional Meanings of Bridge Components. Appl Sci-Basel 2018, 8, (12), 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Y.; Wu, P.; Shou, W. C.; Liu, C. , A Parameter-Driven Method for Modeling Bridge Defects through IFC. J. Comput. Civil. Eng. 2022, 36, (4), 04022015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S.; Almasi, A.; Song, J. , Bridge damage: Detection, IFC-based semantic enrichment and visualization. Automation in Construction 2020, 112, 103088. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, X. F.; Chen, H. A.; Wang, Y. J.; Wu, H. Y. , A Bridge Damage Visualization Technique Based on Image Processing Technology and the IFC Standard. Sustainability 2023, 15, (11), 8769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. I.; Lee, S. H.; Almasi, A.; Song, J. H. , Extended IFC-based strong form meshfree collocation analysis of a bridge structure. Automation in Construction 2020, 119, 103364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekhuizen, M.; Kalogianni, E.; van Oosterom, P. , BIM/IFC as input for registering apartment rights in a 3D Land Administration Systems - A prototype webservice. Land Use Pol. 2025, 148, 107368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altwassi, E. J.; Aysu, E.; Ercoskun, K.; Abu Raed, A. , From Design to Management: Exploring BIM's Role across Project Lifecycles, Dimensions, Data, and Uses, with Emphasis on Facility Management. Buildings-Basel 2024, 14, (3), 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Teo, A. L. E. , Development of a rule-based system to enhance the data consistency and usability of COBie datasheets. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2021, 8, (1), 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Moon, H.; Shin, J. , BIM-Based Maintenance Data Processing Mechanism through COBie Standard Development for Port Facility. Appl Sci-Basel 2022, 12, (3), 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, Y.; Mao, Z. Y.; Hu, M.; Sugumaran, V.; Wang, Y. K. , A digital twin-based decision analysis framework for operation and maintenance of tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 116, 104125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housing and urban-rural development of the People's Republic of China. 2017. "Technical standard of maintenance for city bridge." CJJ 99-2017. Beijing: China Architecture Press.

- Chen, W. , Xu, J., Long P., et al. (2010). "Bridge Maintenance and Management." Beijing: China Communication Press.

- Ministry of Transport of the People's Republic of China. 2021. "Unified Standard for Application of Building Information Modeling in Highway Engineering." JTG/T 2420-2021. Beijing: China Communication Press.

- Administration for Market Regulation of Sichuan Province. 2023. "Highway Engineering Information Model Specification-Part 1: Unified Technical Standards." DB51/T 3092-2023.

- Administration for Market Regulation of Sichuan Province. 2023. "Highway Engineering Information Model Specification-Part 2: Design Technical Standards." DB51/T 3093-2023.

- Administration for Market Regulation of Sichuan Province. 2023. "Highway Engineering Information Model Specification-Part 3: Construction Technical Standards." DB51/T 3094-2023.

- Administration for Market Regulation of Sichuan Province. 2023. "Highway Engineering Information Model Specification-Part 4: Maintenance Technical Standards." DB51/T 3095-2023.

- Administration for Market Regulation of Qinghai Province. 2023. "Guidelines for the Construction and Application of Structural Health Monitoring Systems for Long-Span Highway Bridges." DB63/T 2222-2023.

- Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Department of Transportation. 2022. "Guide to classification and format of structured data sources for highway bridge health monitoring." DBJT45/T 044-2022.

- Dan, DH. 2021. "Intelligent Monitoring of Bridge Engineering Structures: Theory and Practice." Beijing: China Machine Press.

| No. | Crack width range (mm) | Crack Length to Surface Width Ratio | Structural Crack (Yes/No) | Crack Severity Level | Recommendation | |

| 1 | < 0.2 | < 1/3 | - | Slightly damaged | No immediate action is needed, monitor periodically. | |

| 2 | 0.2 to 0.5 | 1/3 to 1/2 | Yes | Medium damaged | Inspection is required and may need repair or reinforcement. | |

| 3 | > 0.5 | >1/2 | Yes | Severely damaged | Immediate action is required, and repair or reinforcement is necessary. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).