Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Example of Translation: Incipit

3. Total Statistics

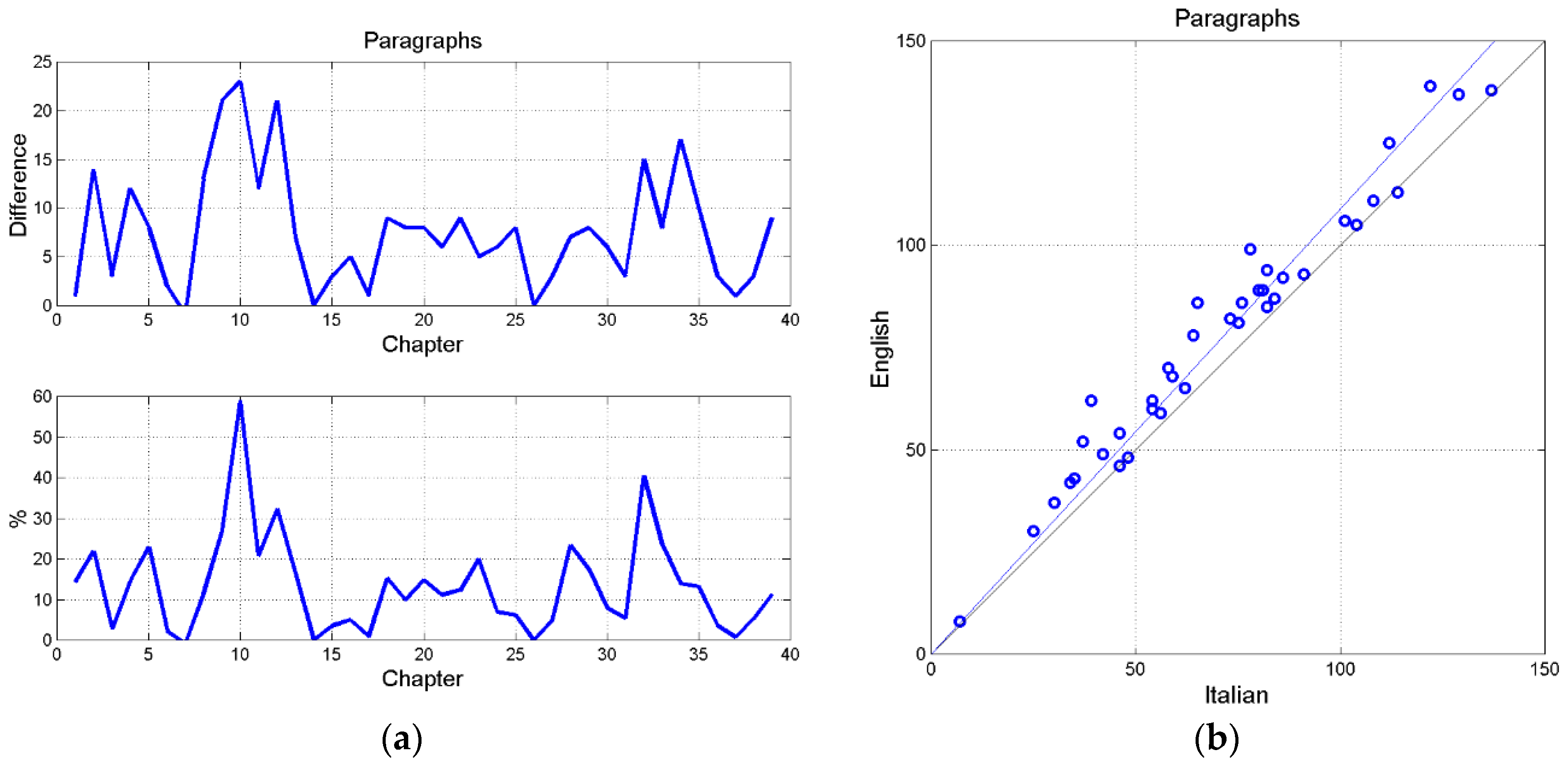

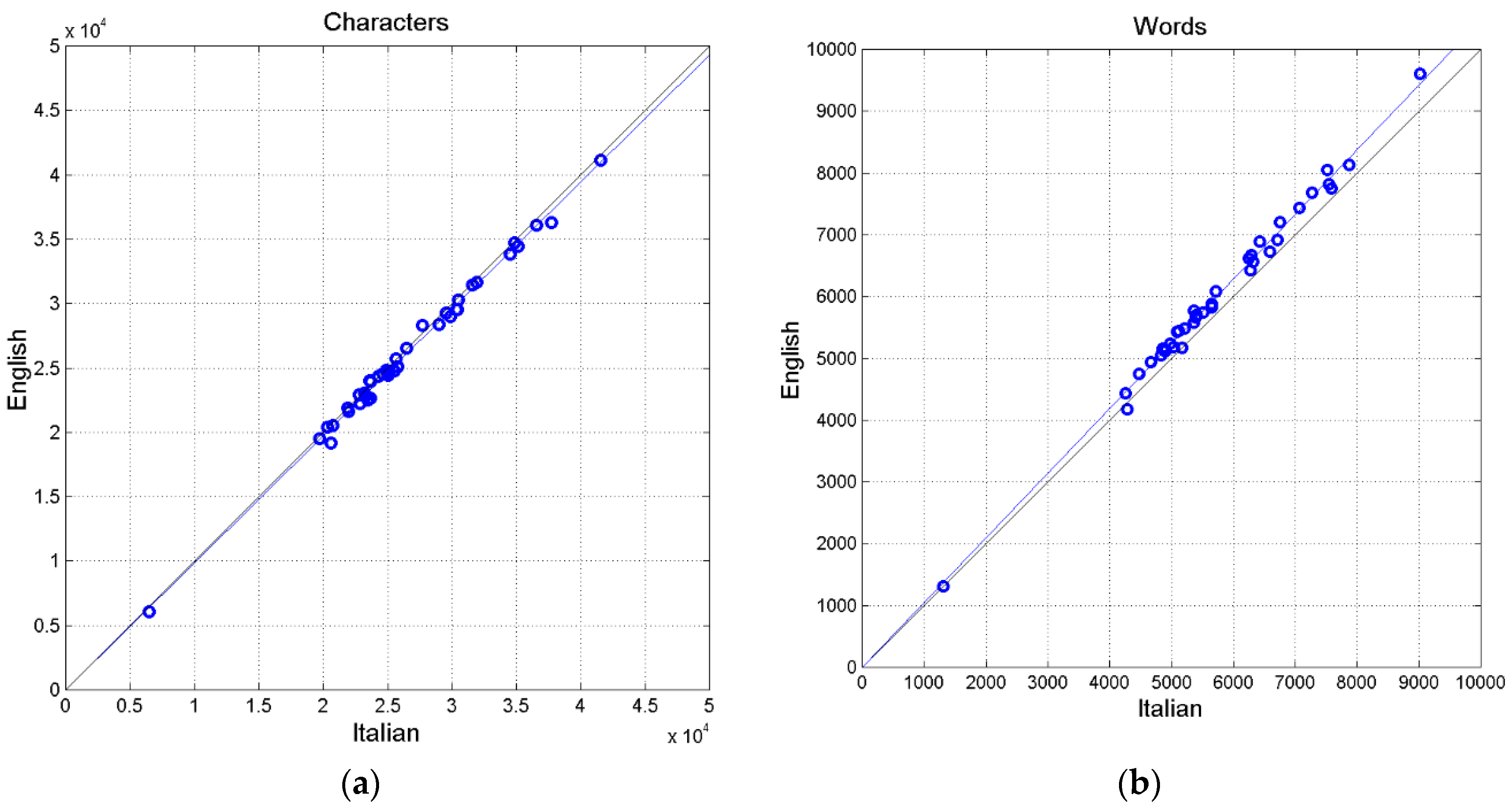

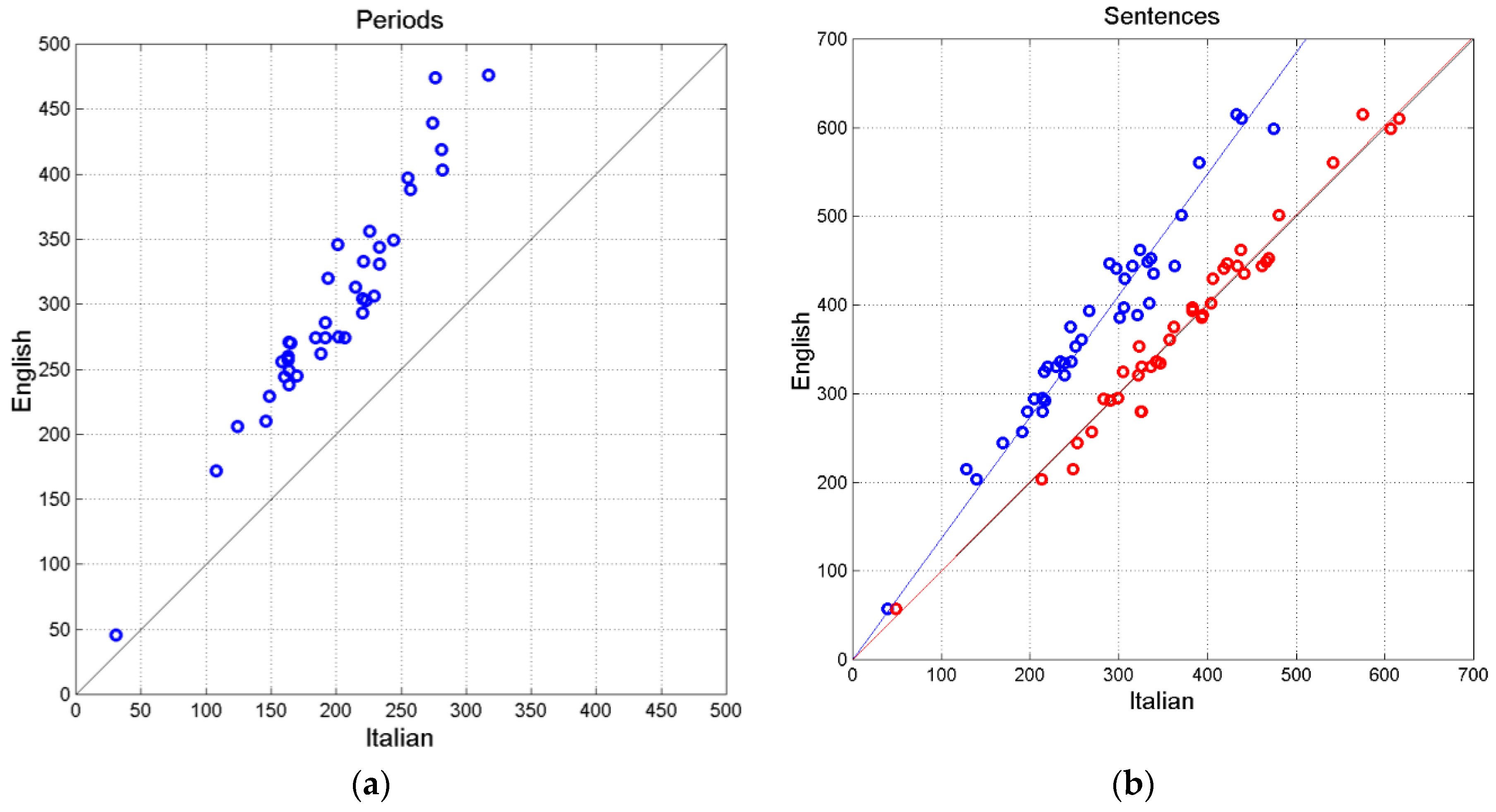

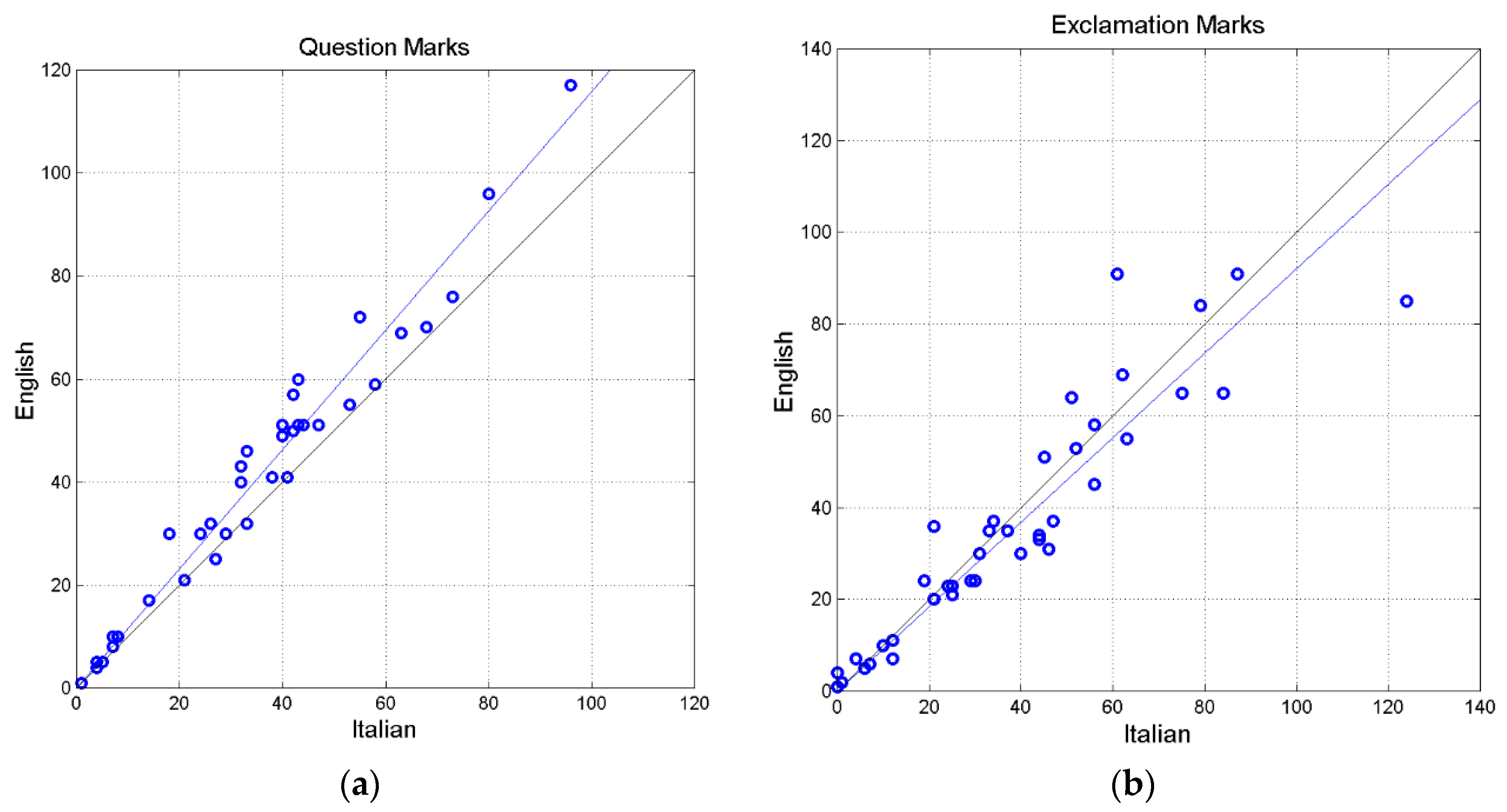

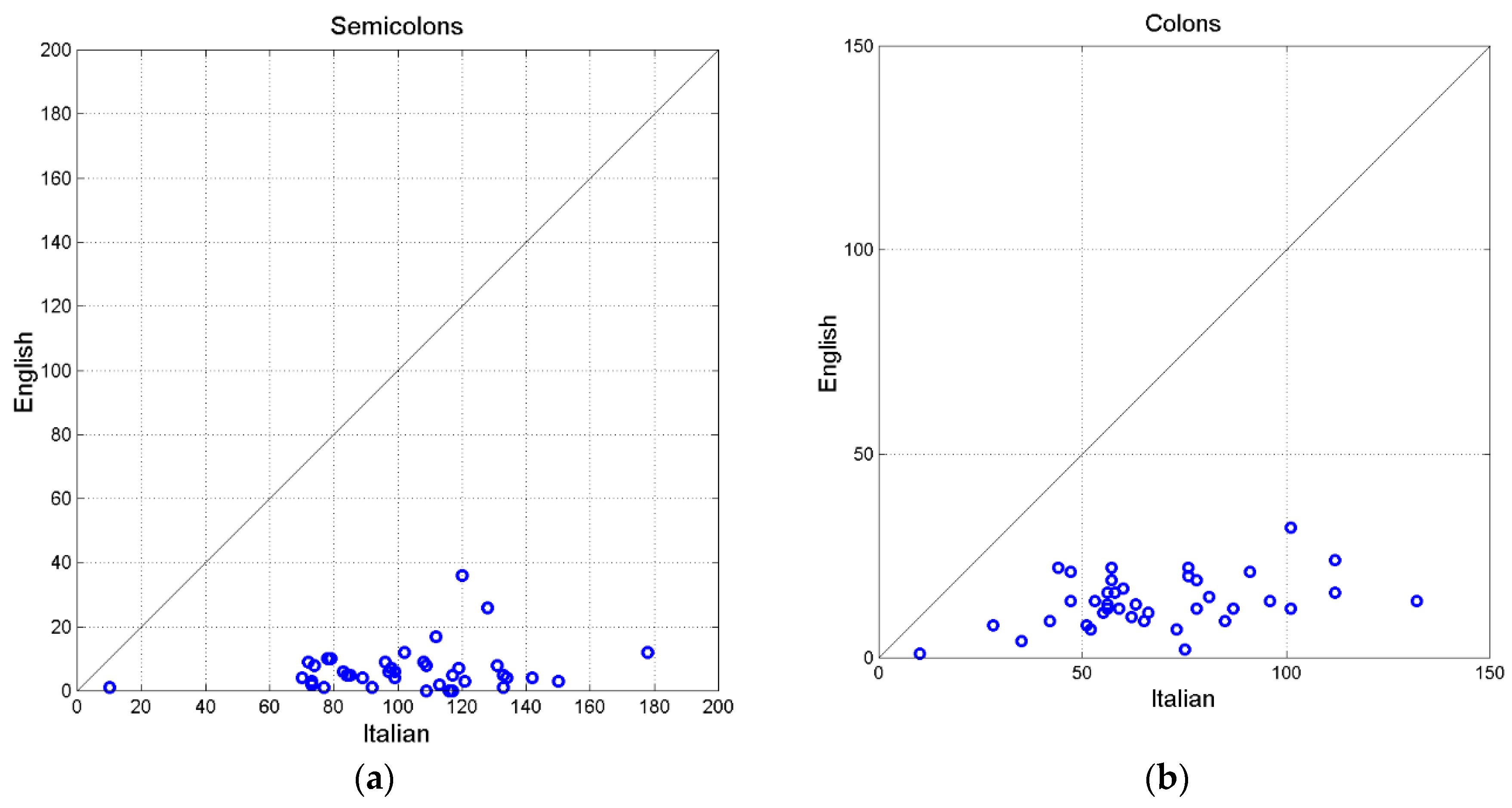

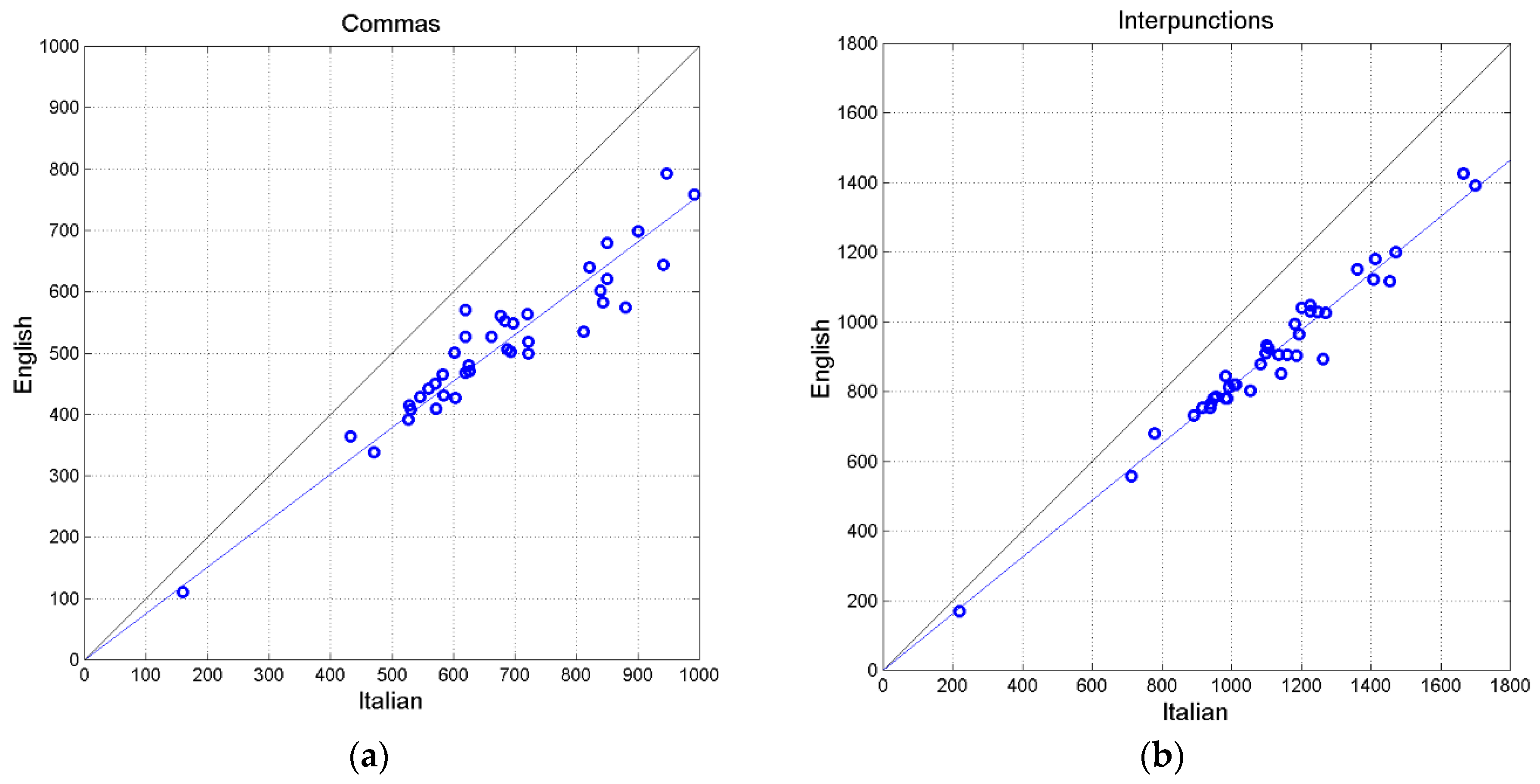

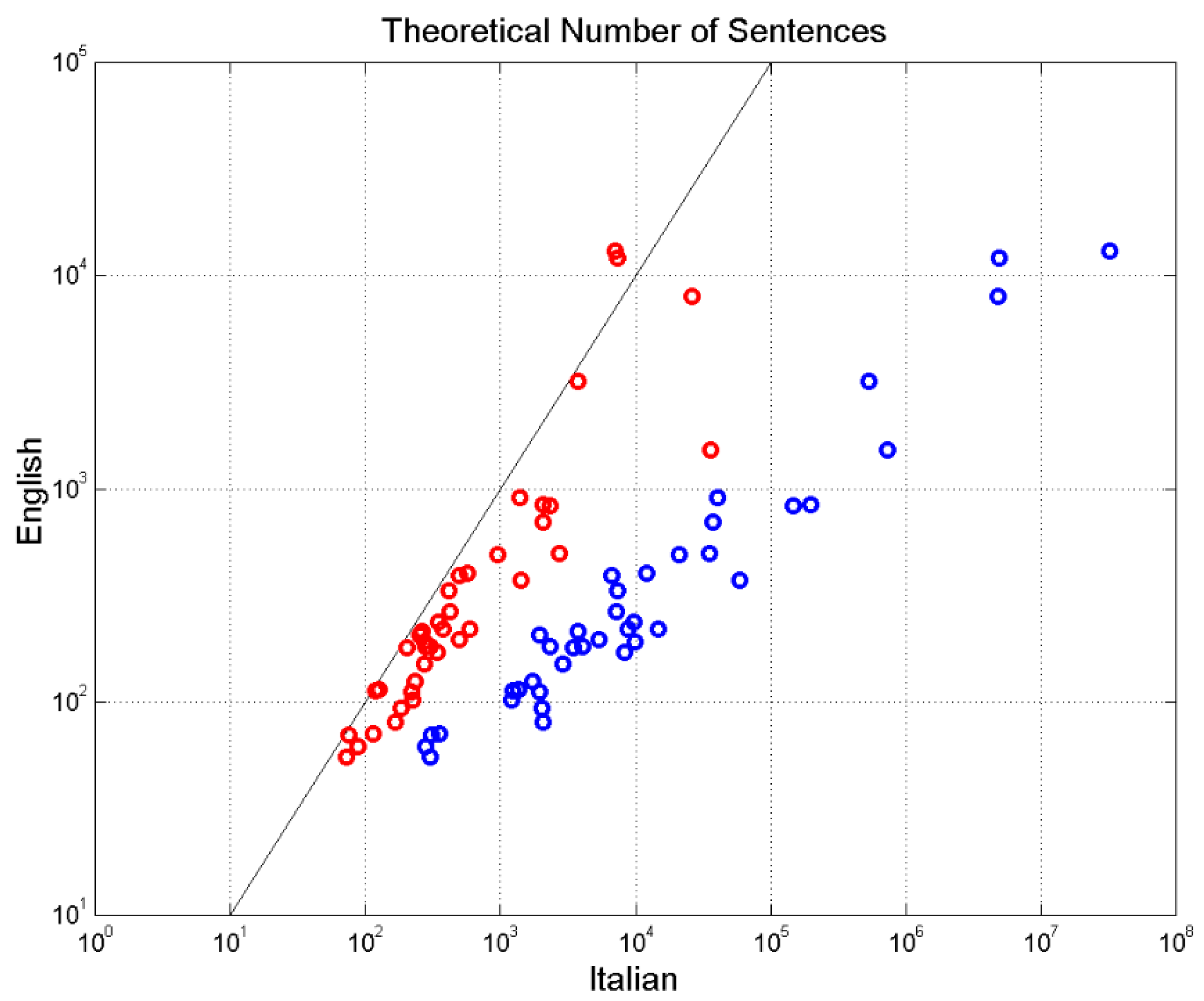

4. Exploratory Data Analysis: Relationships Between Italian and English Linguistic Variables

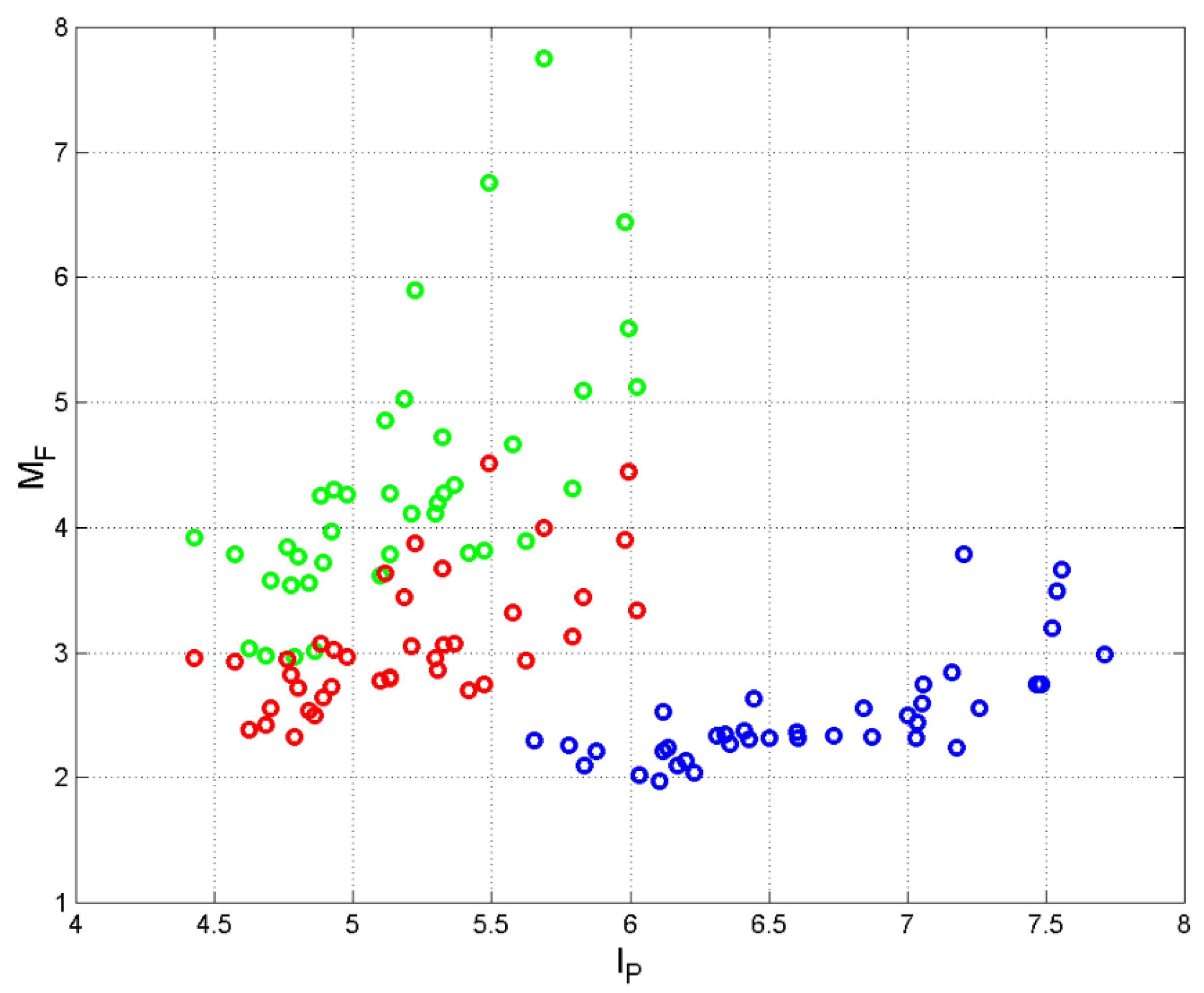

5. Deep–Language Variables

- a)

- is very similar in both languages, for the reason recalled in Section 4.

- b)

- in Italian is, as expected, quite larger than in English. It becomes smaller and very similar to that in English only if semicolons are replaced by periods (Italian-E).

- c)

- is significantly smaller in Italian than in English, due to the large number of interpunctions present in Italian. This parameter does not depend on the type of interpunctions, therefore it is the same also in Italian-E.

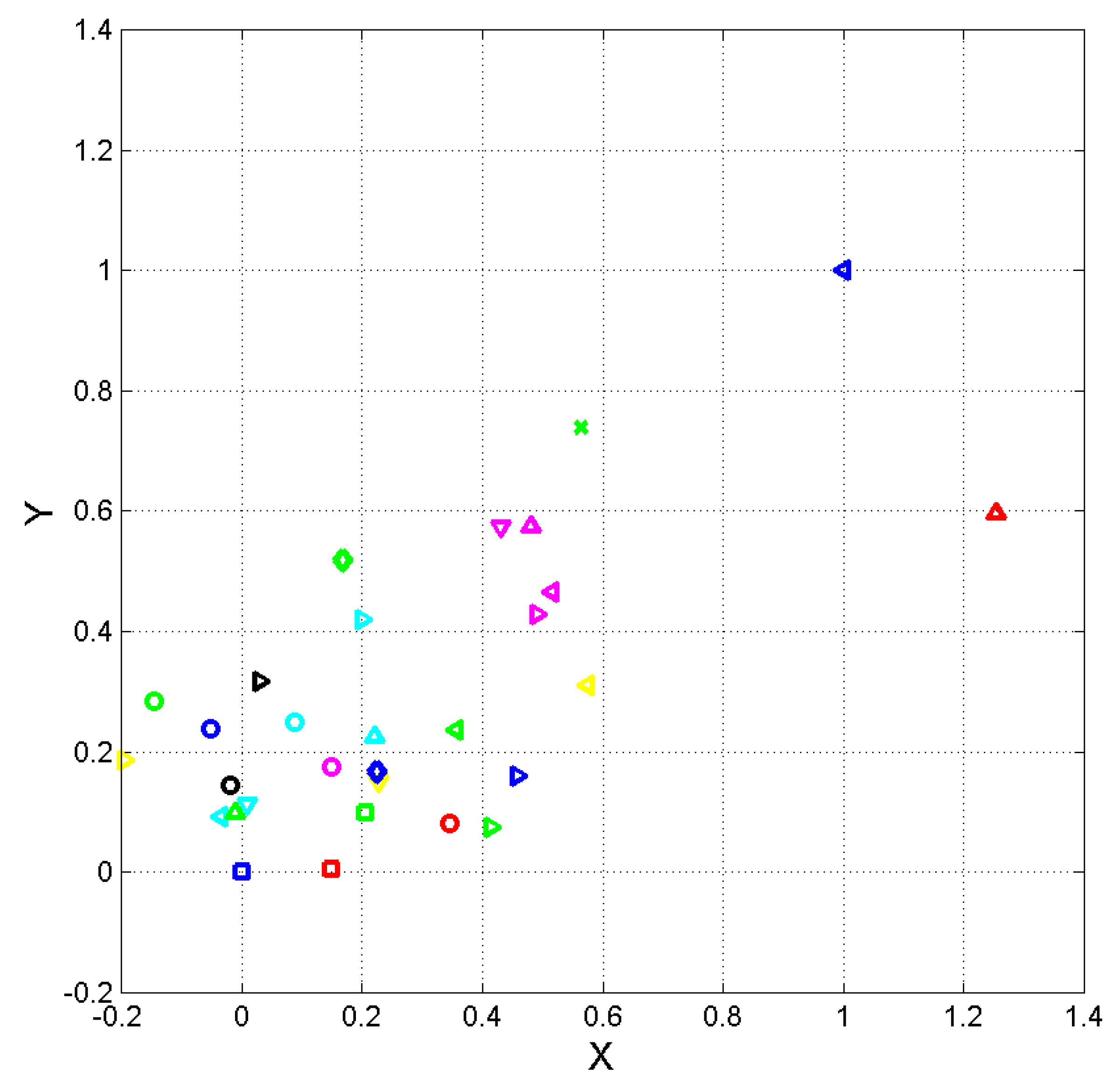

6. Geometrical Representation of Alphabetical Texts

6.1. Vector Representation of Texts

6.2. Error Probability

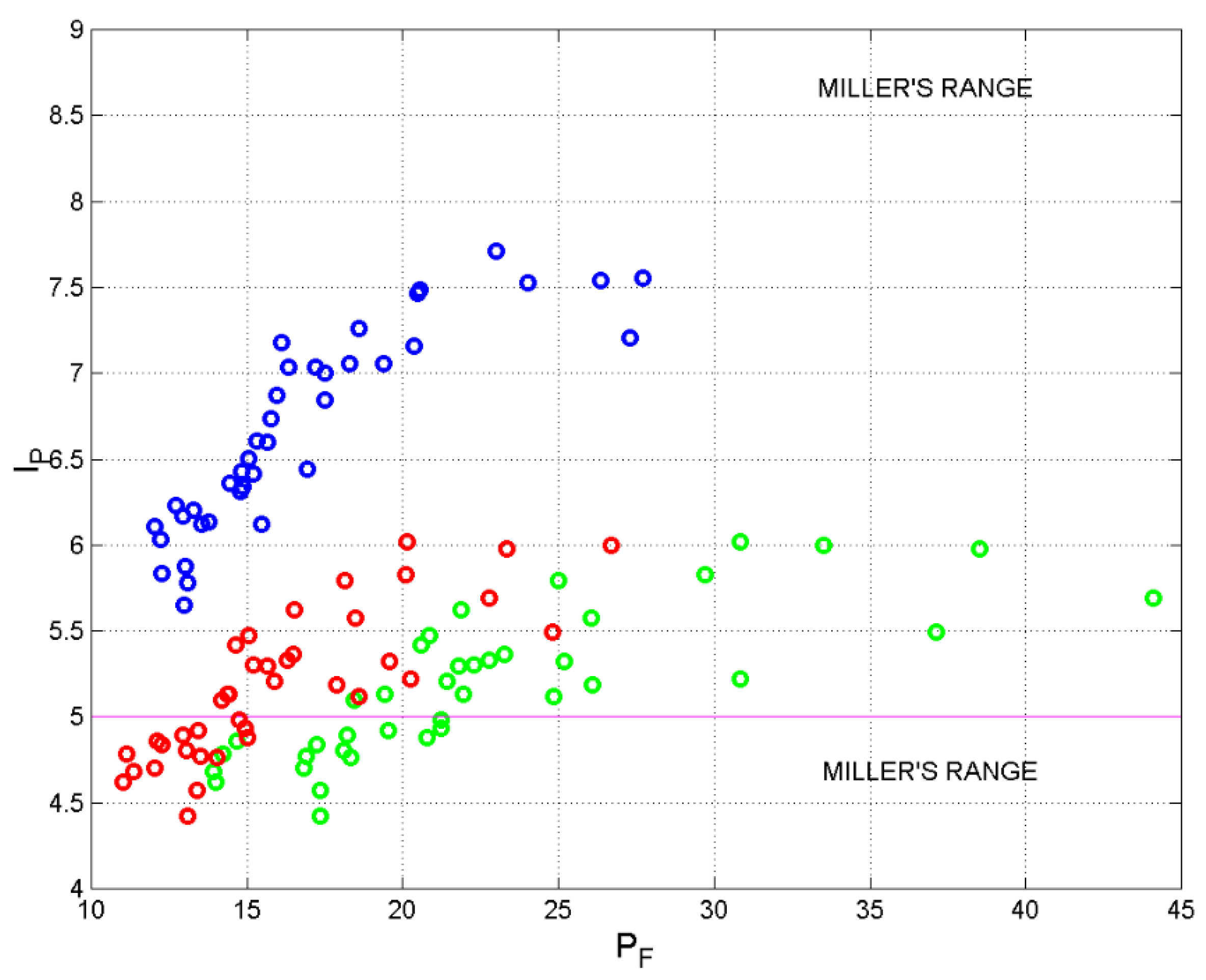

7. Short−Term Memory of Writers/Readers

- a)

- ranges approximately in Miller’s bounds.

- b)

- As the number of words in a sentence, increases, can increase but not linearly, because the first buffer cannot hold, approximately, a number of words larger than that empirically predicted by Miller’s Law, therefore saturation must occur. Scatterplots like that shown in Figure 9 give an insight into the short−term memory capacity engaged in reading/writing a text, because a writer is also a reader of his/her own text.

8. Linguistic Channels

8.1. Linguistic Channels

- (a).

- Sentence channel (S–channel)

- (b).

- Interpunctions channel (I–channel)

- (c).

- Word interval channel (WI–channel)

- (d).

- Characters channel (C–channel).

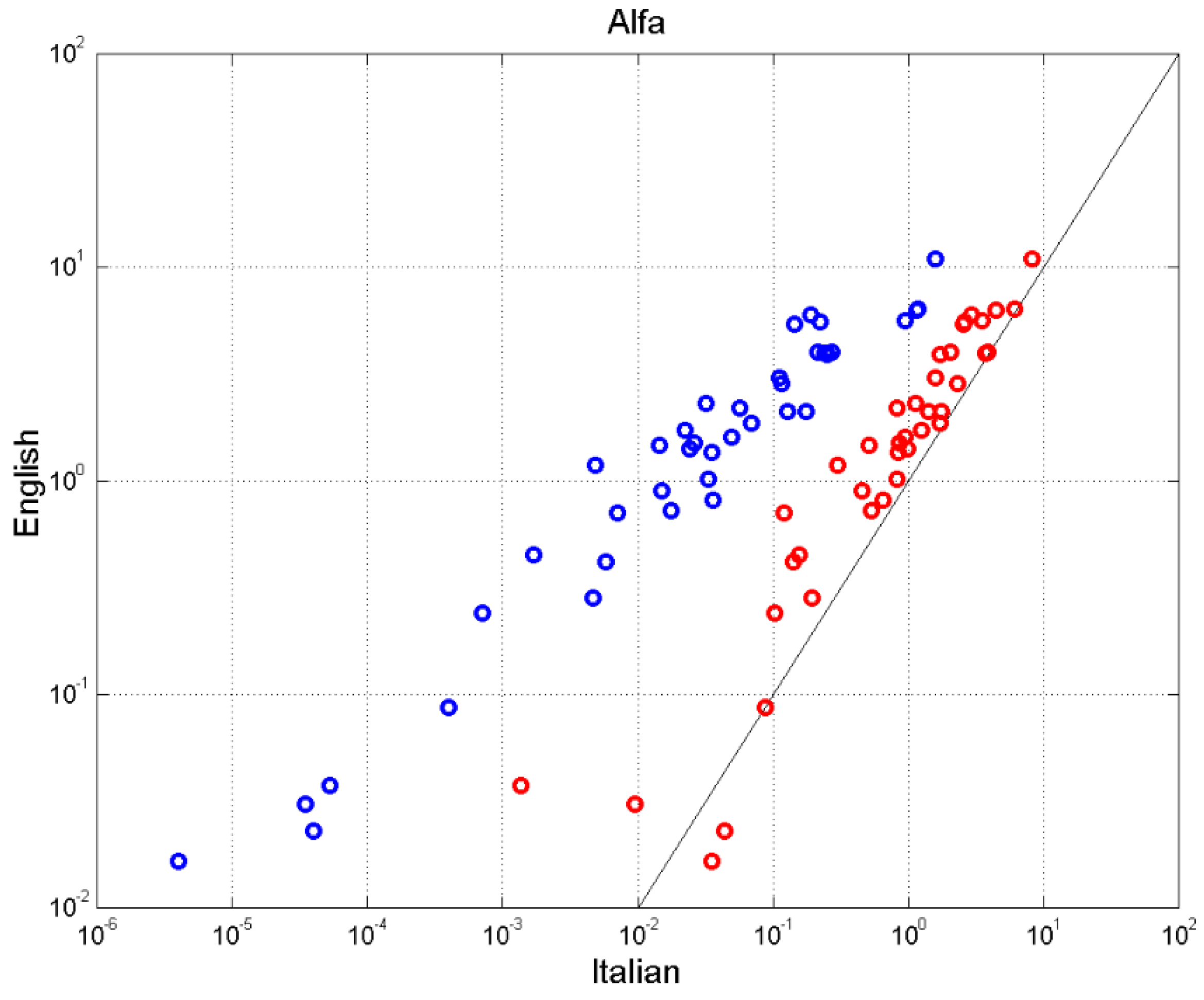

8.2. General Theory of Linear Channels

8.3. The Channel with a Single Scatterplot: One–to–One Correspondence

8.4. Performance of Linguistic Channels in Italian and in English

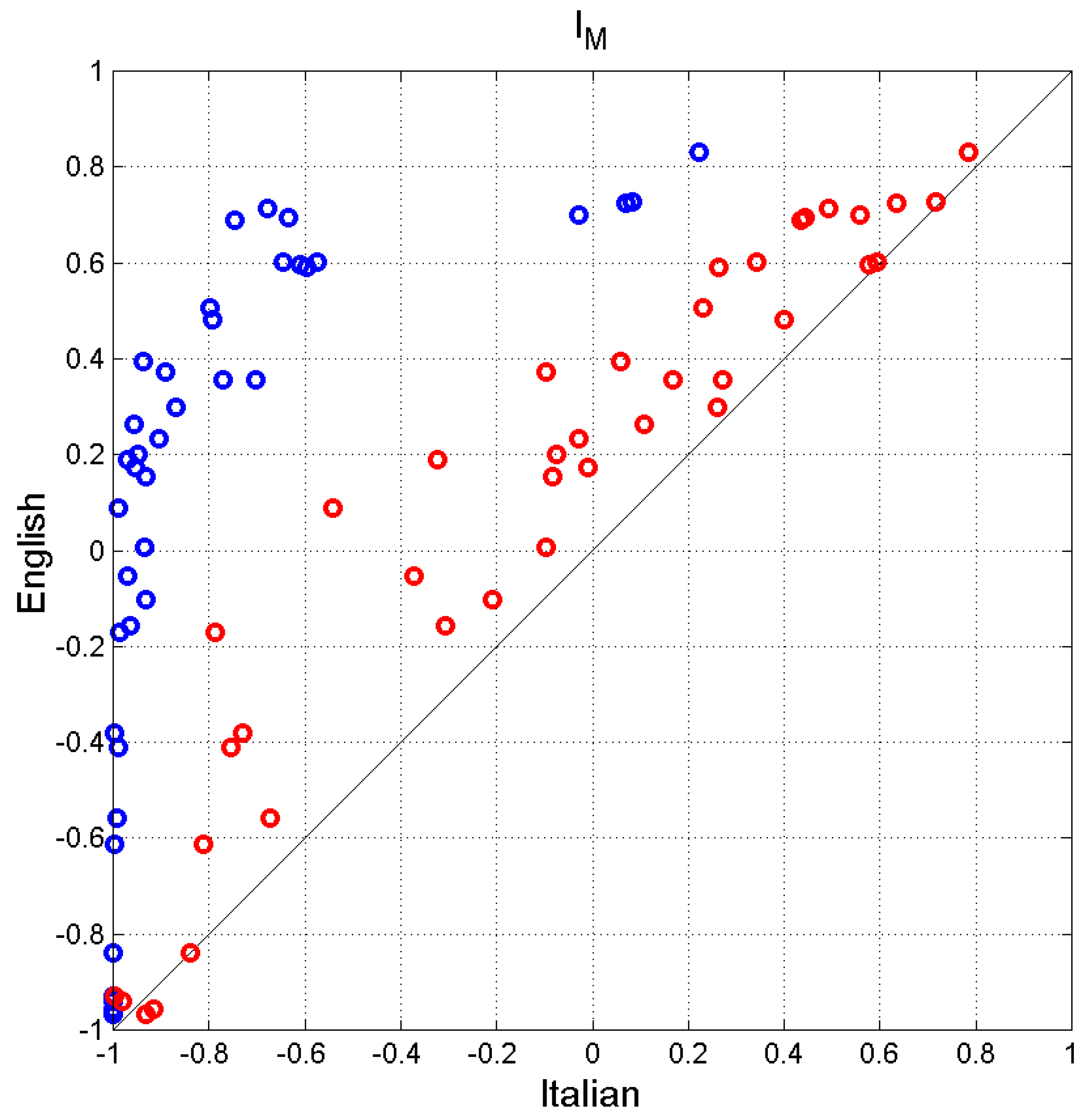

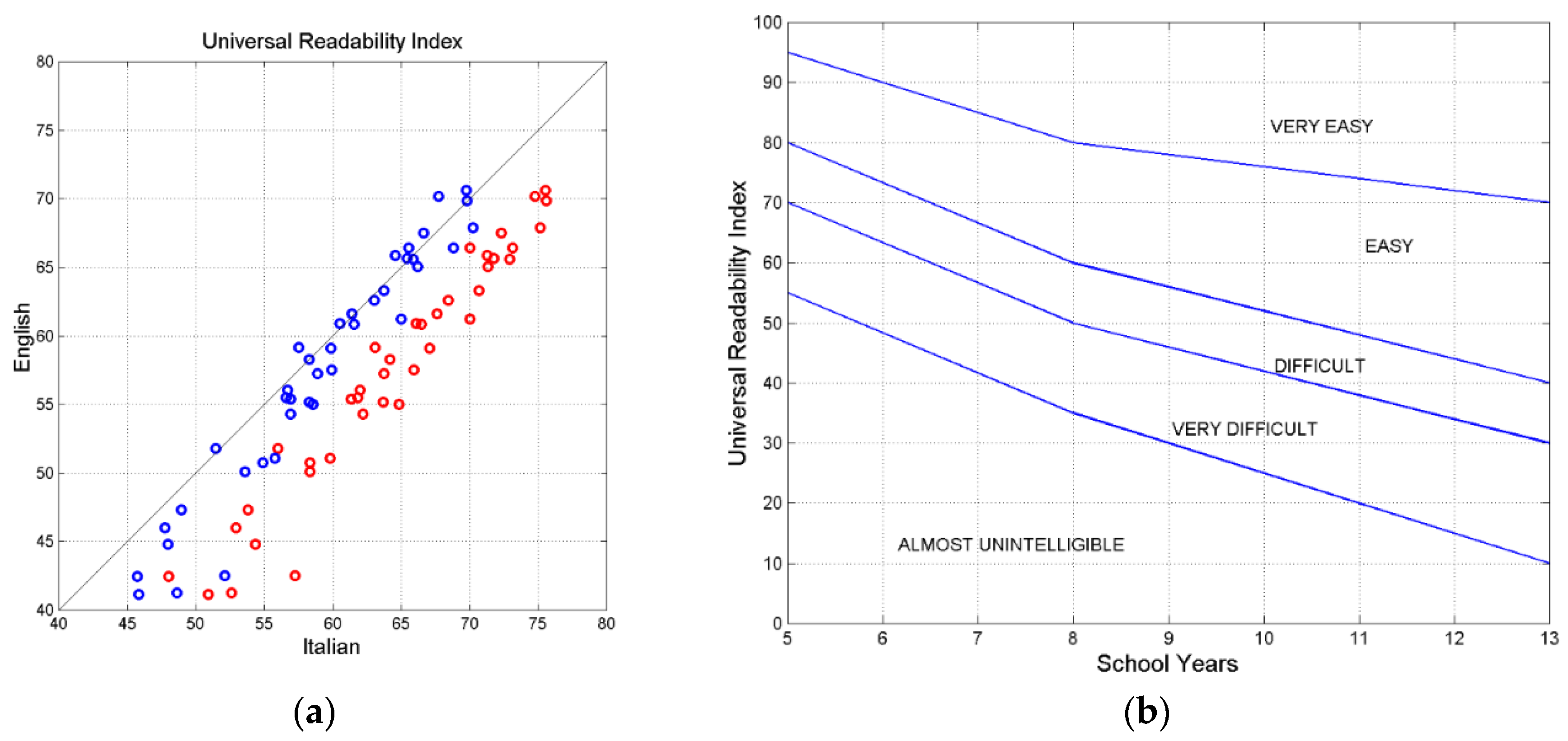

9. Universal Readability Index

- a)

- For , the readability of English is less than Italian; for the two values agree more, they align more with the 45° line (in Italian, in this range, the lower values of balance in Eq. (32) the larger values of ).

- b)

- If semicolons are replaced by periods, the Italian-E text would be much more readable than English, becasue is noticeably reduced while does not change.

10. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Incipit paragraph

Appendix B. Example of Texts

Appendix C. List of Mathematical Symbols and Meaning

| Symbol | Definition |

| Characters per word | |

| Universal readability index | |

| Mismatch index | |

| Word interval | |

| Word intervals per sentence | |

| Words per sentence | |

| Noise–to–signal ratio | |

| Regression noise–to–signal ratio | |

| Correlation noise–to–signal ratio | |

| Total number of sentences | |

| Total number of words | |

| Number of characters | |

| Number of words | |

| Number of sentences | |

| Number of interpunctions | |

| Number of word intervals | |

| Signal–to–noise ratio | |

| Signal–to–noise ratio (dB) | |

| Slope of regression line of text versus text | |

| Correlation coefficient between text and text |

Appendix D. Inequalities

References

- Matricciani, E. Deep Language Statistics of Italian throughout Seven Centuries of Literature and Empirical Connections with Miller’s 7 ∓ 2 Law and Short−Term Memory. Open J. Stat. 2019, 9, 373–406. [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. A Statistical Theory of Language Translation Based on Communication Theory. Open J. Stat. 2020, 10, 936–997. [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Multiple Communication Channels in Literary Texts. Open J. Stat. 2022, 12, 486–520. [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Linguistic Mathematical Relationships Saved or Lost in Translating Texts: Extension of the Statistical Theory of Translation and Its Application to the New Testament. Information 2022, 13, 20. [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Capacity of Linguistic Communication Channels in Literary Texts: Application to Charles Dickens’ Novels. Information 2023, 14, 68. [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Linguistic Communication Channels Reveal Connections between Texts: The New Testament and Greek Literature. Information 2023, 14, 405. [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Is Short−Term Memory Made of Two Processing Units? Clues from Italian and English Literatures down Several Centuries. Information 2024, 15, 6. [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. A Mathematical Structure Underlying Sentences and Its Connection with Short–Term Memory. Appl. Math 2024, 4, 120−142. [CrossRef]

- Catford J.C.; A linguistic theory of translation. An Essay in Applied Linguistics. 1965, Oxford Univeristy Press.

- Munday, J.; Introducing Translation studies. Theories and applications, 2008, Routledge, New York.

- Proshina, Z., Theory of Translation, 2008, Far Eastern University Press.

- Warren, R. (ed.), The Art of Translation: Voices from the Field, 1989, Boston, MA: North-eastern University Press.

- Wilss, W., Knowledge and Skills in Translator Behaviour, 1996, Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication, The Bell System Technical Journal, 1948, 27, p.379–423, and p. 623–656.

- Hyde, G.M., Literary Translation, Hungarian Studies in English, 1991, 22 , 39-47.

- Yousef, T. Literary Translation: Old and New Challenges, International Journal of Arabic-Eng lish Studies (IJAES), 2012, 13, 49-64.

- Nũñez, K.J., Literary translation as an act of mediation between author and reader, Estudios de Traducción, 2012, 2, 21-31.

- Bernaerts, L., De Bleeker, L., De Wilde, J., Narration and translation, Language and Literature, 2014, 23(3) 203–212. [CrossRef]

- Ghazala, H.S., Literary Translation from a Stylistic Perspective, Studies in English Language Teaching, 2015, 3, 2, 124-145.

- Suo, X., A New Perspective on Literary Translation. Strategies Based on Skopos Theory, Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2015, 5, 1, 176-183. [CrossRef]

- Munday, J. (Editor), The Routledge Companion to Translation Studies, 2009, Routledge, New York.

- Munday, J., Introducing Translation Studies.Theories and applications, 2016, Routledge, New York.

- Panou, D. Equivalence in Translation Theories: A Critical Evaluation, Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 2013, 3, 1, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Saule, B., Aisulu, N. Problems of translation theory and practice: original and translated text equivalence, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014,136, 119-123. [CrossRef]

- Krein- Kühle, M., Translation and Equivalence, in House, J (Ed.), Translation: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 2014, Palgrave Advances in Language and Linguistics.

- Matricciani, E. Multi–Dimensional Data Analysis of Deep Language in J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis Reveals Tight Mathematical Connections. AppliedMath 2024, 4, 927–949. [CrossRef]

- Venuti, L., The Translator’s Invisibility. A History of Translation, 1995, Routledge, New York.

- Manzoni, A. The Betrothed, translated and with an Introduction by Michael F. Moore, 2022, New York: The Modern Library.

- Cella, R., Storia dell'italiano, Bologna: Società Editrice Il Mulino, 2015.

- Frare, P., Una struttura in movimento: sulla forma artistica dei «I promessi sposi». The Italianist, 1996, 16(1), 62–75. [CrossRef]

- Raboni, G., La scrittura purgata: sulla cronologia della seconda minuta dei Promessi sposi, Filologia italiana, 2008, 5, Istituti editoriali e poligrafici internazionali;

- Frare, P., La scrittura dell'inquietudine: saggio su Alessandro Manzoni, 2006, Firenze : L.S. Olschki.

- Frare, P., Salvioli, M., Prodigi di misericordia e forza del linguaggio. Sui capitoli XXI e XXIII dei «Promessi sposi», Munera, 2016; 3, 109-119.

- Bruthiaux, P., The Rise and Fall of the Semicolon: English Punctuation Theory and English Teaching Practice, Applied Linguistics, 1995, 16, 1, 1-14.

- Duncan, M., Whatever Happened to the Paragraph? College English, 2007, 69, 5, 470-495.

- Watson, C., Points of Contention: Rethinking the Past, Present, and Future of Punctuation, Critical Inquiry, 2012, 38, 3, 649-672. [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Readability Indices Do Not Say It All on a Text Readability. Analytics 2023, 2, 296−314. [CrossRef]

- Papoulis, A.; Probability & Statistics, 1990, Prentice Hall, 1990.

- Lindgren, B.W. Statistical Theory, 2nd ed.; 1968, MacMillan Company: New York, NY, USA.

- Miller, G.A.; The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two. Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information, Psychological Review, 1955, 343−352.

- Crowder, R.G. Short–term memory: Where do we stand?, 1993, Memory & Cognition, 21, 142–145. [CrossRef]

- Lisman, J.E., Idiart, M.A.P. Storage of 7 ± 2 Short–Term Memories in Oscillatory Subcycles, 1995, Science, 267, 5203, 1512– 1515. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N., The magical number 4 in short−term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2000, 87−114. [CrossRef]

- Bachelder, B.L. The Magical Number 7 ± 2: Span Theory on Capacity Limitations. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2001, 24, 116–117. [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L., Ozdemir, M.S., Why the Magic Number Seven Plus or Minus Two, Mathematical and Computer Modelling, 2003, 233−244. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, N., Hitch, G.J. A revised model of short–term memory and long–term learning of verbal sequences, 2006, Journal of Memory and Language, 55, 627–652. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.T.E, Measures of short–term memory: A historical review, 2007, Cortex, 43, 5, 635–650. [CrossRef]

- Mathy, F., Feldman, J. What’s magic about magic numbers? Chunking and data compression in short−term memory, Cognition, 2012, 346−362. [CrossRef]

- Melton, A.W., Implications of Short–Term Memory for a General Theory of Memory, 1963, Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 2, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R.C., Shiffrin, R.M., The Control of Short–Term Memory, 1971, Scientific American, 225, 2, 82–91.

- Murdock, B.B. Short–Term Memory, 1972, Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 5, 67–127.

- Baddeley, A.D., Thomson, N., Buchanan, M., Word Length and the Structure of Short−Term Memory, Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 1975, 14, 575−589. [CrossRef]

- Case, R., Midian Kurland, D., Goldberg, J. Operational efficiency and the growth of short–term memory span, 1982, Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 33, 386–404. [CrossRef]

- Grondin, S. A temporal account of the limited processing capacity, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2000, 24, 122−123. [CrossRef]

- Pothos, E.M., Joula, P., Linguistic structure and short−term memory, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2000, 124, 138−139.

- Conway, A.R.A., Cowan, N., Michael F. Bunting, M.F., Therriaulta, D.J., Minkoff, S.R.B., A latent variable analysis of working memory capacity, short−term memory capacity, processing speed, and general fluid intelligence, Intelligence, 2002, 163−183. [CrossRef]

- Jonides, J., Lewis, R.L., Nee, D.E., Lustig, C.A., Berman, M.G., Moore, K.S., The Mind and Brain of Short–Term Memory, 2008 Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 193–224. [CrossRef]

- Potter, M.C. Conceptual short–term memory in perception and thought, 2012, Frontiers in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Jones, G, Macken, B., Questioning short−term memory and its measurements: Why digit span measures long−term associative learning, Cognition, 2015, 1−13. [CrossRef]

- Chekaf, M., Cowan, N., Mathy, F., Chunk formation in immediate memory and how it relates to data compression, Cognition, 2016, 155, 96−107. [CrossRef]

- Norris, D., Short–Term Memory and Long–Term Memory Are Still Different, 2017, Psychological Bulletin, 143, 9, 992–1009.

- Houdt, G.V., Mosquera, C., Napoles, G., A review on the long short–term memory model, 2020, Artificial Intelligence Review, 53, 5929–5955. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M., Sarkar, A., Hossain, M., Ahmed, M., Ferdous, A. Prediction of Attention and Short–Term Memory Loss by EEG Workload Estimation. Journal of Biosciences and Medicines, 2023, 304–318. [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Readability across Time and Languages: The Case of Matthew’s Gospel Translations. AppliedMath 2023, 3, 497–509. [CrossRef]

- Abramovitz, M.; Stegun, I.A., Handbook of Mathematical Formulas, Dover publications, 1972, New York, 9th ed.

| Paragraphs | Words | Periods (Sentences) |

Commas | Semicolons | Colons | |

| Italian | 1 | 682 | 9 | 103 | 9 | 5 |

| English | 5 | 701 | 23 | 58+8 | 1 | 0 |

| Paragraphs | Words per paragraph |

Characters | Characters per word |

Words |

Words per sentence |

Sentences | |

| Italian | 2732 | 82.1 | 1,036,560 | 4.62 | 224,234 | 21.1 | 10627 |

| Italian–E | 2732 | 82.1 | 1,036,560 | 4.62 | 224,234 | 15.3 | 14647 |

| English | 3029 | 77.5 | 1,022,239 | 4.36 | 234,646 | 16.0 | 14676 |

| English-I | 3029 | 77.5 | 1,022,239 | 4.36 | 234,646 | 30.6 | 7672 |

| Periods | Question Marks | Exclamation Marks | Commas |

Semicolons | Colons | Interpunctions | |

| Italian | 7795 | 1335 | 1497 | 26316 | 4020 | 2633 | 43596 |

| English | 11692 | 1558 | 1426 | 20003 | 263 | 540 | 35482 |

| Linguistic Variable | Correlation Coefficient | Slope |

| Characters | 0.9973 | 0.9861 |

| Paragraphs | 0.9809 | 1.0897 |

| Words | 0.9967 | 1.0470 |

| Sentences | 0.9771 | 1.3704 |

| Sentences (Italian-E) | 0.9868 | 1.0047 |

| Question Marks | 0.9820 | 1.1581 |

| Exclamation Marks | 0.9237 | 0.9215 |

| Commas | 0.9477 | 0.7572 |

| Interpunctions | 0.9826 | 0.8143 |

| Italian | 4.62 0.12 |

22.7 6.24 |

5.18 0.41 |

4.34 1.03 |

| Italian–E | 4.62 0.12 |

16.01 -- |

5.18 0.41 |

3.07 -- |

| English | 4.36 0.15 |

16.82 4.56 |

6.66 0.56 |

2.50 0.43 |

| English-I | 4.36 0.15 |

30.30 -- |

6.66 0.56 |

4.53 -- |

| Text | S–Channel Sentences vs Words |

I-Channel Words vs Interpunctions |

WI–Channel Word Intervals vs Sentences |

C–Channel Characters vs Words |

||||

| Correlation Coefficient | Slope | Correlation Coefficient | Slope | Correlation Coefficient |

Slope | Correlation Coefficient |

Slope | |

| Italian | 0.5978 | 0.0470 | 0.9357 | 5.1220 | 0.7863 | 3.9374 | 0.9926 | 4.6263 |

| Italian-E | 0.6980 | 0.0649 | 0.9357 | 5.1220 | 0.8573 | 2.9070 | 0.9926 | 4.6263 |

| English | 0.7106 | 0.0623 | 0.9322 | 6.5785 | 0.8932 | 2.3587 | 0.9884 | 4.3560 |

| S-Channel | I-Channel | WI-Channel | C-Channel | |||||||||

| Ita | Ita-M | Eng | Ita | Ita-M | Eng | Ita | Ita-M | Eng | Ita | Ita-M | Eng | |

| Italian | ∞ | 10.69 | 11.35 | ∞ | ∞ | 13.09 | ∞ | 8.11 | 2.50 | ∞ | ∞ | 23.08 |

| Italian-E | 7.48 | ∞ | 26.81 | ∞ | ∞ | 13.09 | 11.13 | ∞ | 12.04 | ∞ | ∞ | 23.08 |

| English | 8.36 | 27.22 | ∞ | 10.91 | 10.91 | ∞ | 7.56 | 14.06 | ∞ | 23.71 | 23.71 | ∞ |

| Variable | (dB) | |

| Characters | 22.62 | 182.97 |

| Paragraphs | 12.62 | 18.27 |

| Words | 20.23 | 105.49 |

| Sentences | 6.45 | 4.42 |

| Sentences (Italian-E) | 15.65 | 36.75 |

| Question Marks | 11.27 | 13.40 |

| Exclamation Marks | 8.17 | 6.57 |

| Commas | 9.07 | 8.07 |

| Interpunctions | 12.35 | 17.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).