1. Introduction

Echinacea preparations are frequently used to treat upper respiratory tract infections [

1]. A different line of evidence suggests that in addition, they have psychotropic effects. Particularly, certain extracts of Echinacea angustifolia decreased anxiety in both laboratory and human studies [2-4]. A recent study, however, reported antidepressant and wellbeing-enhancing effects for the same preparation administered in similar doses, but no effects on anxiety [

5]. The reason for this discrepancy is unknown.

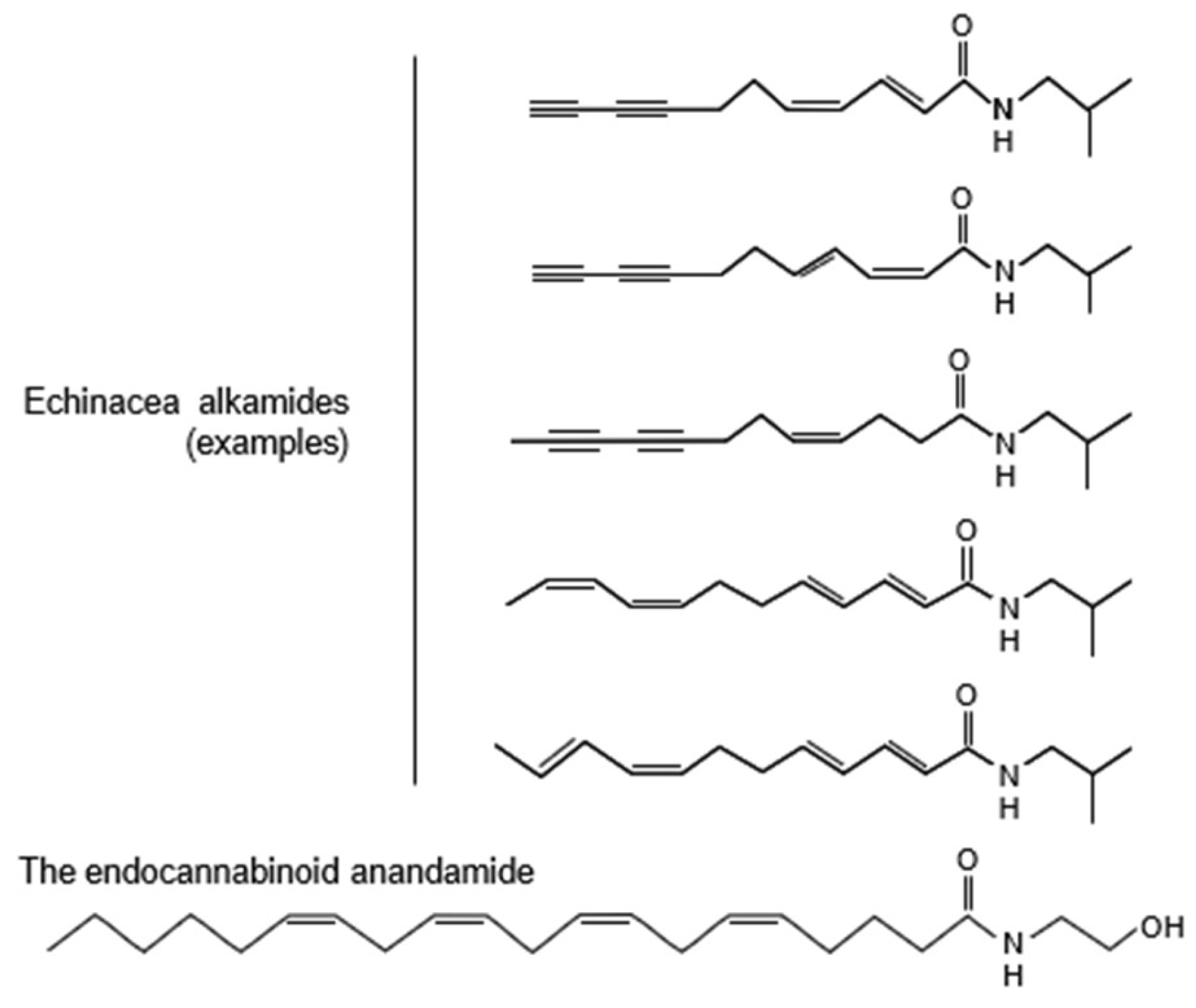

The psychotropic effects of Echinacea extracts may be explained by the alkamides that they contain. These affect cannabinoid signaling, which in its turn is involved in both the control of anxiety and depression [6-9]. Echinacea alkamides are markedly similar to the endocannabinoid anandamide (Fig. 1) and bind to the brain CB1 cannabinoid receptor; in addition, they inhibit the fatty acid amid hydrolase (FAAH) enzyme, which degrades anandamide [

10]. Isolated alkamides were also studied in [35S]GTPcS-binding experiments involving rat brain membrane preparations [

11]. Significant inverse agonist effects were detected with certain alkamides, while others had partial agonist effects. Echinacea alkamides also interacted with the effects of the CB1 agonist reference compound arachidonyl-20-chloroethylamide. Taken together, these molecular findings show that Echinacea alkamides affect endocannabinoid signaling.

Figure 1.

Structural similarities between the endocannabinoid anandamide and Echinacea alkamides. The latter were shown as examples; all Echinacea alkamides have highly similar structures. For more information on alkamide structure and their presence in various plants see Boonen et al. 2012 [

12].

Figure 1.

Structural similarities between the endocannabinoid anandamide and Echinacea alkamides. The latter were shown as examples; all Echinacea alkamides have highly similar structures. For more information on alkamide structure and their presence in various plants see Boonen et al. 2012 [

12].

In electrophysiological studies, an Echinacea angustifolia root extract suppressed excitatory synaptic transmission in hippocampal slices without changing inhibitory synaptic transmission [

13]. In addition, the Echinacea extract reduced the spiking activity of CA1 pyramidal cells at doses compatible with brain levels reached after oral administration [

14]. As the hippocampus is involved in the control of anxiety and it was suggested that anxiety disorders may result from hippocampal hyperactivity [15-17], the reduction of hippocampal excitatory synaptic transmission by Echinacea is consistent with an anxiolytic effect.

Anxiolytic effects were more directly studied by behavioral pharmacological methods in rodents. The same extract that affected molecular mechanisms in the hippocampus also reduced anxiety-like behavior in four anxiety tests. It increased open arm exploration and social interactions in the elevated plus-maze and social interaction tests, respectively, and reduced stress-induced social avoidance and conditioned fear [2-3]. The effective dose range was surprisingly low (3-8 mg/kg) and comparable to that observed with the benzodiazepine chlordiazepoxide and the selective serotonin reuptake blocker fluoxetine, which were tested as comparators in the same studies under similar conditions [2-3].

The anxiolytic potential of Echinacea was also investigated in human studies. These studies used the same extract that was investigated in the molecular, electrophysiological, and behavioral pharmacological studies briefly presented above. The reason was that the anxiolytic potential was not a general property of Echinacea extracts. On the contrary, most extracts were ineffective in laboratory tests of anxiety [

2]. After this early study that compared 5 different extracts, we investigated other 12. Unpublished studies found just one other extract that showed an anxiolytic potential. Based on a series of studies with various extracts and isolated alkamides it was established that the anxiolytic potential of Echinacea preparations depended on their specific alkamide fingerprint. A proprietary standardization process involving over ten Echinacea production sites ensured the stability of this fingerprint. The inhouse code for this proprietary alkamide fingerprint was EP107

TM, which term was first used in a publication by Lopresti and Smith [

5].

Two of the three human studies published so far – a dose-control and another, double-blind, placebo-controlled study – evaluated anxiety by the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [

18] and reported a significant anxiolytic effect that developed within a few days [3-4]. In the study by Lopresti and Smith [

5], anxiety was evaluated by the Clinically Useful Anxiety Outcome Scale (CUXOS) [

19]. In this study, anxiety decreased, but this was statistically similar in the placebo and EP107

TM-Echinacea groups. However, antidepressant-like, and wellbeing-enhancing effects were observed with two tests that were not employed in earlier studies, particularly the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule and Short Form-36 Health Survey.

It was repeatedly shown that the performance of anxiety screening methods is variable and depends on a variety of factors [20-21]. Of particular interest are findings showing that the STAI revealed anxiolytic effects more readily than other tests of anxiety, e.g., the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) or the visual analog scale for anxiety [22-23].

To test the putative anxiolytic effects of the EP107

TM-Echinacea extract further, here we investigated its effects on human subjects studied by means of inventories that have not been used earlier to this purpose. Particularly, we employed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety Subscale (HADS-A) [

24] and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) [

25]. The items of the former are exclusively related to psychic signs, whereas those of the latter focus mainly on physical signs of anxiety. The study was randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind and multicenter.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

We studied 26 middle-aged subjects (43.3±1.9 years); 7 were males and 19 were females. Gender ratio corresponded to the European gender distribution of anxiety disorders [

26]. Although the investigational product was in use for several years in the US, there are no previous human data in the studied indication available to support a formal sample size calculation. A sample size of 12 participants per group was chosen in this investigation. The justifications for this sample size were based on rationale about feasibility; precision about the mean and variance; and regulatory considerations as described by Julious [

27]. We screened 27 potential participants to account for potential dropouts.

The study was approved by the National Institute of Pharmacy (Budapest, Hungary) under the registration number OGYI/23775-6/2010. It was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, applicable Hungarian legislation on human studies and medical data protection, and the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice. This study was registered in the EU Clinical Trials Register (EudraCT Number: 2010-020431-33, Protocol Number: ANX001).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) age 18 to 60 years (inclusive). (ii) Diagnosis of GAD according to DSM-IV criteria at the screening (recruiting) visit. (iii) Total HAM-A score between 17 and 25 points at the screening visits. (iv) Total Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score lower than 10. (v) Good physical health, defined as no clinically relevant symptomatology identified by detailed medical history, as well as a full physical examination including sitting blood pressure and heart rate measurement. (vi) Ability and willingness to comply with study procedures as confirmed by a signed informed consent form.

Subjects were excluded if they (i) had any DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis within the 6 months that preceded the study (e.g. any anxiety disorder other than generalized anxiety, any depressive disorder, anorexia, bulimia, alcohol or substance abuse or dependence, schizophrenia, etc.). (ii) Showed any Axis II disorder (e.g. antisocial or borderline personality disorder); (iii) Presented serious suicidal risk according to the clinical investigator's judgment. (iv) Currently used psychotropic medications that could not be discontinued prior to randomization (3 months for benzodiazepines, 5 weeks for fluoxetine and 14 days for monoamine oxidase inhibitors). (v) Currently used drugs, supplements, prescription or nonprescription, or foods that have psychoactive properties. (vi) Were subjects of formal psychotherapy within 3 months prior to screening. (vii) Had positive drug tests at screening or randomization visits for any of the following: amphetamines, barbiturates, opiates, benzodiazepines, sedatives and hypnotics, cocaine, phencyclidine, cannabinoids. (viii) Had a history of allergies or intolerance to any Echinacea product. (ix) Were treated with Echinacea within 60 days preceding the first dose of trial medication. Women had to be non-lactating, and non-pregnant as checked by pregnancy tests, and had to use hormonal or barrier method of contraception or be postmenopausal.

2.2. Study design and treatments

This was a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, multi-site, Phase 2, placebo controlled fixed-dose study of EP107

TM-Echinacea root extract and placebo in outpatients with generalized anxiety disorder. It was performed under the management of Accelsiors CRO (

https://accelsiors.com).

Treatments consisted of 7mm diameter, round, biconvex tablets administered two times a day (in the morning and in the evening). Tablets either contained the proprietary Echinacea EP107

TM extract with a unique alkamide profile (20 mg per tablet, 40 mg per day), or its excipients only (placebo). Blinding was maintained with identical film-coated tablets, and emergency code envelopes were available for unblinding if needed. The pharmaceutical company ExtractumPharma Co (Budapest, Hungary) manufactured both types of tablets. The product was registered by the National Institute for Food and Nutrition Science (file No. 2249-4/2010 OÉTI). Dosage was based on a previous study showing that 2*20 mg but not 20 mg daily doses of a similar treatment ameliorated anxiety symptoms [

2].

Investigators were trained psychiatrists from the following four clinics: Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Hospital (Department of Psychiatry), Normental Medical and Organizational Limited Partnership Company, Semmelweis University (Institute of Behavioral Sciences and the Clinic of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy), and State Health Center (Department of Psychiatry). The study was run in late summer-autumn-winter (August-February).

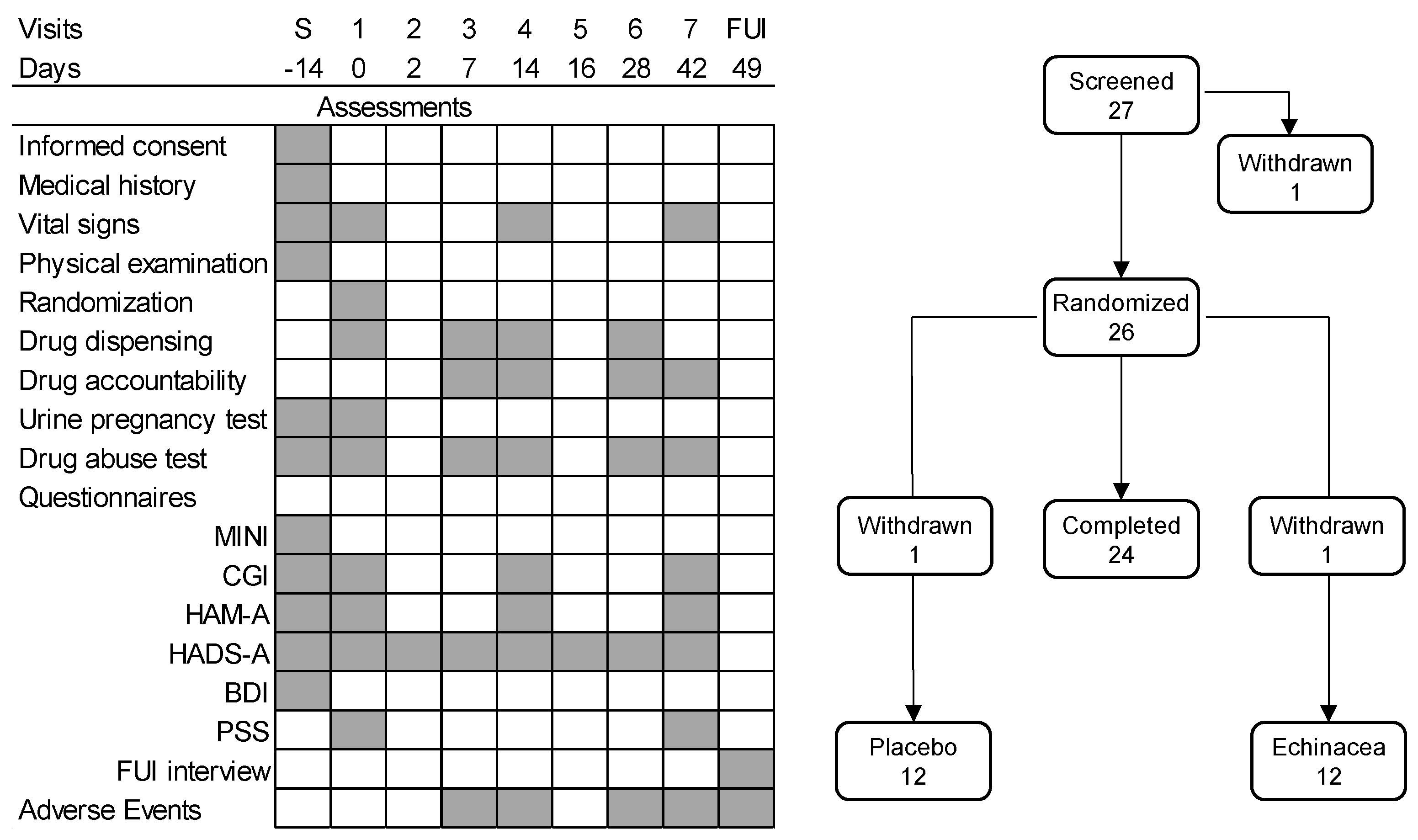

The design of the study was shown in Fig. 2. New patients arriving at the study sites were informed about the study in detail and were offered the opportunity to participate. Those willing signed an informed consent form, after which they underwent medical and psychiatric examination. The medical history of participants was checked; thereafter, they underwent a physical examination, and the psychometric tests shown in Fig. 2. Those who fulfilled the criteria listed above were asked to return after two weeks to start the study.

The six-week treatment phase started with the randomization visit when participants were examined again, were randomized for Echinacea or placebo treatments, and received the study drugs in the form of identical white tablets. Treatments started on the randomization day. Thereafter, drugs were dispensed on a weekly basis on days 7, 14, and 28 of the study. Treatment compliance was checked each time, and participants returned unused tablets. At each visit, participants underwent psychiatric testing as shown in Fig. 2. In addition, vital signs (see below) were checked at screening, at randomization, and on days 14 and 42. Drug abuse was checked at each study site visits. Urine pregnancy tests were performed at screening and at randomization; thereafter, this test was performed when participants reported the possibility of a new pregnancy. Adverse events were checked on days 7, 14, 28, and 42). The study ended on day 49 with a follow-up interview, which focused on adverse effects, and the putative necessity of further therapeutic interventions.

Figure 2.

The design of the study. Left-hand panel: the timing of assessments. Right-hand panel: the number of participants over the phases of the study. BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; FUI, follow-up interview; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety subscale; HAM-A, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; MINI, MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; withdrawn, the participant withdraw consent to participation. Note that the HADS-A is a self-reporting instrument, for which it was administered repeatedly, whereas the HAM-A is a clinician-administered instrument, filled only during visits to the study sites. The validity of HADS-A home administrations was studied on study days R and 2 as well as days 14 and 16, when the same inventory was filled in in the clinic and at home at two-day intervals.

Figure 2.

The design of the study. Left-hand panel: the timing of assessments. Right-hand panel: the number of participants over the phases of the study. BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; FUI, follow-up interview; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety subscale; HAM-A, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; MINI, MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; withdrawn, the participant withdraw consent to participation. Note that the HADS-A is a self-reporting instrument, for which it was administered repeatedly, whereas the HAM-A is a clinician-administered instrument, filled only during visits to the study sites. The validity of HADS-A home administrations was studied on study days R and 2 as well as days 14 and 16, when the same inventory was filled in in the clinic and at home at two-day intervals.

In earlier studies [3-4] the anxiolytic effects of -Echinacea EP107TM developed rather rapidly. To check for this phenomenon, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Anxiety subscale (HADS-A) was also completed repeatedly by participants at home, beginning with the 2nd day of treatment (Fig. 2). To check for the validity of home scoring, these followed clinical screening by two days on days 2 and 16 of the study. The two scores were highly similar, demonstrating that the results of home scoring were reliable. Note that such structured self-assessment diary techniques were employed earlier in a variety of disorders including anxiety [28-29].

2.3. Psychometric instruments

Diagnosis was established by the structured MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview [

30]. Anxiety was assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - Anxiety subscale (HADS-A) and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) (see below for details). (Depression symptoms and life events were assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [

31]. Note that depression was investigated at the screening visit only to rule out the accidental inclusion of depressed patients in the study. Stress perception was investigated by the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS). In addition, the severity of anxiety was also investigated by the Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI).

The HADS-A is a self-reporting questionnaire designed to evaluate the severity of anxiety symptoms [

24]. This test provides a valid measure of anxiety and is widely used in clinical practice [

32]. It consists of 7 items, which are scored on a 4-point scale from 0 (not present) to 3 (considerable). The item scores are added, giving scores from 0 to 21. Cutoff scores for normal, moderate, and severe anxiety are 0-7, 8-10, and 11-21, respectively. The HAM-A is a clinician-administered scale that measures the severity of anxiety symptoms [

25]. It was one of the first rating scales developed and is still widely used in both clinical and research settings [

33]. The scale consists of 14 items, each defined by a series of symptoms. Cutoff scores for normal, mild, moderate and severe anxiety are 0-9, 10-15, 16-24, and 25-42, respectively. The BDI identifies the presence and severity of symptoms consistent with depression criteria of DSM-IV. The scale was used only in the eligibility assessment of patients and was completed during the screening visit only. The PSS is a measure of the degree to which life situations are appraised as stressful [

34]. This widely used psychological instrument was designed to determine how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded respondents find their lives. The 10-item version was employed. No cutoff scores are available for this test. The CGI is a 7-point scale on which the clinician rates the severity of the patient's illness – anxiety in this study – relative to personal experience with patients with a similar diagnosis. The following ratings can be assigned: 1, not ill; 2, borderline mentally ill; 3, mildly ill; 4, moderately ill; 5, markedly ill; 6, severely ill; 7, extremely ill. Anxiety severity ratings correlate well with established and validated measures of anxiety [35-36].

We used the validated Hungarian versions of all tests (MINI [

37]; HADS-A [

38]; HAM-A [

39]; BDI [

40]; PSS [

41]).

2.4. Other measures

The following vital signs were evaluated after at least 5 min rest at the screening and randomization visits: body temperature, sitting blood pressure, respiratory rate, and pulse rate. Physical condition was evaluated by a trained physician, and covered the external assessment of head, eyes, ears, nose and throat, lungs, cardiovascular system, breast, abdomen, musculoskeletal system, skin, lymph nodes, and central nervous system (e.g., Achilles reflex). Body weight was also recorded. Physical condition was checked again on the last day of the study. Pregnancy – an exclusion criterion – was evaluated by a clinical urine pregnancy test performed at the local lab. Suspected pregnancies that occurred during the study were checked in a similar fashion. Drug abuse was evaluated by routine laboratory tests for the following drug classes: amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine. Adverse events, e.g., any undesirable signs, symptoms or medical conditions that occurred after the start of the treatment, were recorded even if not considered to be related to treatment. Such events may have been reported by participants, discovered by investigators or detected through physical examination, laboratory test or other means. Serious adverse events would have led to the discontinuation of treatment, and treatment until they receded. No such instances occurred during the study. Note that safety assessments consisted of monitoring and recording adverse events, vital signs, physical condition, and body weight changes.

2.5. Statistics

The main objective of the study was to conduct a preliminary evaluation of the safety and efficacy of EP107TM-Echinacea as compared to placebo for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, and to provide an estimate of the variance, which may be used in a formal sample size calculation in subsequent studies. Sample sizes were described above, and statistics were made on the per protocol subset (PP).

Data were shown as mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM), except for categorical data, which were shown as ratios (e.g., male/female ratio). These were compared by crosstabulation. Psychometric scores were evaluated by two-factor repeated measures ANOVA where the repeated measures factor was time (visits as levels), and factor 2 was treatment (levels: Echinacea and placebo). Unexpectedly, however, there was a significant change in HADS-A scores between screening and randomization (Fig. 3A). Particularly, HADS-A scores increased in the Echinacea group, and slightly decreased in the placebo group. To correct this pre-treatment difference, HADS-A data were evaluated by repeated measure ANCOVA. The categorical factors of this analysis were treatment and time, whereas the continuous predictor was the randomization day. The Duncan test was used for post-hoc comparisons. Discrete data of a narrow range (e.g., individual items of the HAM-A) were compared by Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA. To evaluate effect sizes, the Hedges’ g was calculated. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

All patients were Caucasian; their age was between 24 and 59 years. Baseline psychometric scores were summarized in

Table 1. In total, 15 female patients (both groups) were potentially able to bear children; all urine pregnancy tests were negative. None of the participants used drugs from the following drug classes: amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, cocaine, opiates, phencyclidine. Drug tests were negative throughout. No abnormality was detected during the study except for those observed at screening (

Table 1).

3.2. Effects on anxiety

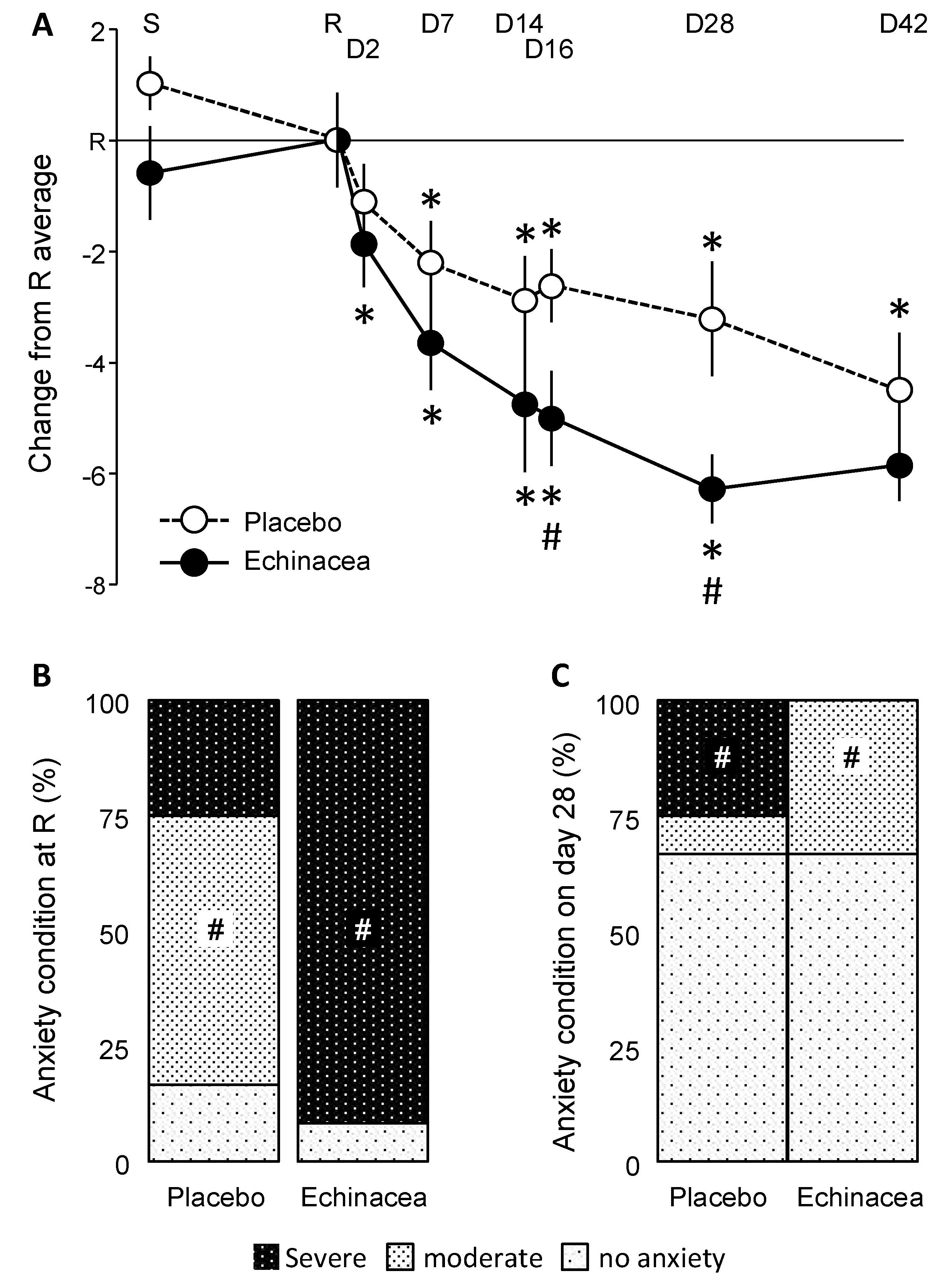

HADS-A scores depended on the interaction between factors (Wilk’s lambda= 0.419; Finteraction(7, 14) = 2.77; p< 0.05). Significant decreases in HADS-A scores were observed on day 2 and day 7 in the Echinacea and placebo groups, respectively (Fig. 3A). Note that for clarity, data were presented as differences from the day of randomization, but statistics were done on raw data. A significant group difference emerged on days 16 and 28, when Hedges’ g values were 0.899 and 1.034, respectively. These values fall into the "large" range based on common benchmarks for Hedges's g.

Figure 3.

The impact of EP107TM-Echinacea on HADS-A scores. A. HADS-A scores over the experimental period. Both treatments decreased anxiety compared to the randomization visit; however, the effects of Echinacea developed faster and were larger. Noteworthy, ANCOVA was performed on raw data; differences compared to the randomization visit were presented only for clarity. B and C. The anxiety state of participants on the randomization day and on the 28th day of the treatment. Anxiety state was established based on established cutoff scores (see Methods). For more explanations see text. D, study day; R, randomization visit; S, screening visit; #, significant Echinacea/placebo difference; *, significant difference from randomization visit, same group (p< 0.05 at least).

Figure 3.

The impact of EP107TM-Echinacea on HADS-A scores. A. HADS-A scores over the experimental period. Both treatments decreased anxiety compared to the randomization visit; however, the effects of Echinacea developed faster and were larger. Noteworthy, ANCOVA was performed on raw data; differences compared to the randomization visit were presented only for clarity. B and C. The anxiety state of participants on the randomization day and on the 28th day of the treatment. Anxiety state was established based on established cutoff scores (see Methods). For more explanations see text. D, study day; R, randomization visit; S, screening visit; #, significant Echinacea/placebo difference; *, significant difference from randomization visit, same group (p< 0.05 at least).

The frequency distribution of anxiety states was similar at the screening visit (χ2 = 7.64; p > 0.1). At randomization, however, the two groups diverged (χ2 = 11,90; p < 0.036) (Fig. 3B). In the placebo group, most participants showed moderate anxiety, whereas severe anxiety was dominant in the Echinacea group. This pre-treatment difference was in line with temporal changes observed in HADS-A scores (see above). Despite the pre-treatment dominance of severe anxiety, this state disappeared on the 28th day of treatment in the Echinacea but not in the placebo group (Fig. 3C). 25% of participants still showed severe anxiety in the placebo group, whereas 8% showed moderate anxiety. By contrast, no severe anxiety was observed in the Echinacea group; those who did not recover showed moderate anxiety. On day 42, severe anxiety disappeared from both groups, and HADS-A scores of most patients fell below the threshold of anxiety (χ2= 1.35; p> 0.4). Taken together, however, Echinacea treatment decreased anxiety more rapidly and efficiently than placebo, despite the strong effects of the latter.

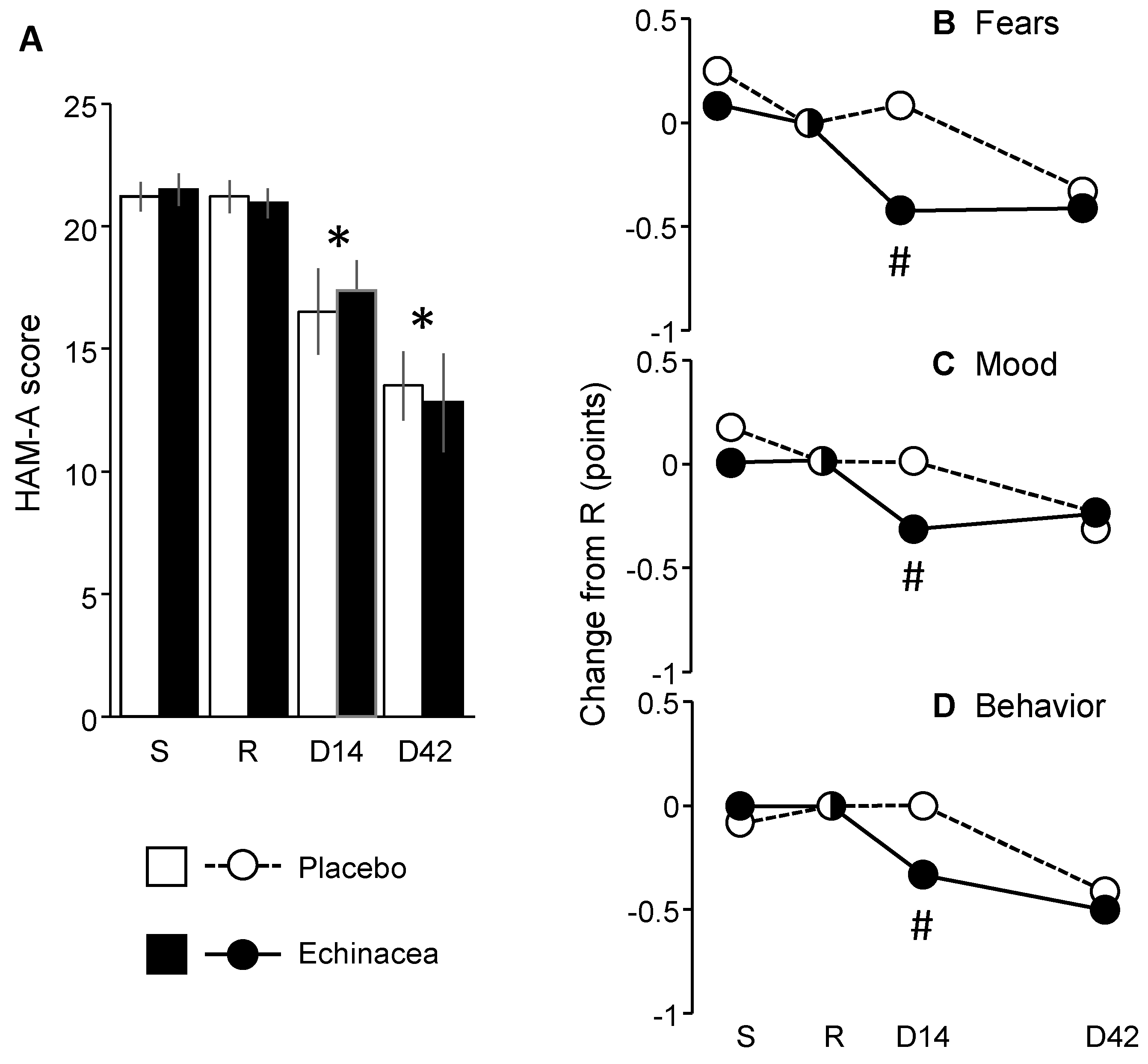

HAM-A scores did not change in the pretreatment period and decreased significantly thereafter irrespective to the treatment received (Fig. 4A) (Fgroup (1,22)= 0.01; p> 0.9; Ftime (3,66)= 36.27; p< 0.0001; Finteraction (3,66)= 0.41; p> 0.7). Scores were consistent with moderate anxiety at screening and randomization visit and with mild anxiety by the end of the treatment period. Exploratory analyses showed, however, that three items of HAM-A underwent treatment-dependent changes over time (Fig. 4B-D). Particularly, the scores of fears (item 3), depressed mood (item 6) and behavior at interview (item 14) were more favorably affected by Echinacea than by placebo (fears: H(1, N= 24)= 5.63; p< 0.01; depressed mood: H(1, N= 24)= 4.83 p< 0.05; behavior at interview: H(1, N= 24)= 4.73; p< 0.05). Thus, the decrease in HAM-A scores did not depend on treatment, but a few placebo-Echinacea differences suggest that some psychic anxiety item scores improved more rapidly in the EP107TM-Echinacea as compared to the placebo group.

Figure 4.

The impact of EP107TM-Echinacea on HAM-A scores.A. HAM-A over the treatment period. B-D. In exploratory analyses, three psychic anxiety items of the HAM-A showed larger improvements in the EP107TM-Echinacea as compared to the placebo group. D, day of the study; R, randomization visit; S, screening visit; #, significant Echinacea/placebo difference; *, within-group significant difference from randomization visit (p< 0.05 at least).

Figure 4.

The impact of EP107TM-Echinacea on HAM-A scores.A. HAM-A over the treatment period. B-D. In exploratory analyses, three psychic anxiety items of the HAM-A showed larger improvements in the EP107TM-Echinacea as compared to the placebo group. D, day of the study; R, randomization visit; S, screening visit; #, significant Echinacea/placebo difference; *, within-group significant difference from randomization visit (p< 0.05 at least).

CGI scores decreased from around 4 (Placebo, randomization visit: 4.15±0.10; Echinacea, randomization visit: 4.08±0.14) to around 3 by the end of the study (Placebo, day 28: 2.92±0.24; Echinacea, day 28; 2.77±0.34). Thus, the experimenter-estimated clinical state of participants improved from moderately ill to mildly ill, but the improvement was independent of treatment (Ftreatment(1,94)= 0.02; p< 0.9; Ftime(3,94)= 16.96; p< 0.001; Finteraction(3,94)= 0.15; p< 0.9). PSS scores did not change significantly (data not shown).

3.3. Adverse events

Two patients withdrew from the study. One was from the placebo, while the other was from the EP107TM-Echinacea group. Four patients reported 9 adverse effects. Two patients were on placebo, while the other two were on EP107TM-Echinacea group. Concerning severity, all events were assessed mild except for one that was considered moderate intensity. This was depressive mood reported by a patient from the placebo group. None of the adverse events required any treatment and all resolved spontaneously. Concerning physical examinations, there were five patients with abnormal physical findings (e.g. hypertension). Two were from the EP107TM-Echinacea group, while three were from the placebo group. Thus, the frequency of adverse events was similar in the placebo and EP107TM-Echinacea groups.

4. Discussion

EP107TM Echinacea decreased anxiety more efficiently than placebo according to the HADS-A. Anxiolysis developed more rapidly and was stronger than in placebo. By contrast, HAM-A scores decreased irrespective of the treatment received. However, the effects of Echinacea were stronger in the case of three psychic anxiety items as compared to placebo. The CGI did not differentiate treatments although it was able to reveal improvements over the treatment period. The incidence and severity of adverse events was similar in the two treatment groups.

The effects of placebo were surprisingly strong in this study. In an earlier one, which also was placebo-controlled and double blind, the effects of placebo were considerably weaker and transient only [

4]. We hypothesize that strong placebo effects were due to the conditions under which the present study was performed. Although not fully understood, it was shown that placebo effects increase when patients perceive the healing environment as optimal, site visits are frequent and when patient expectations are high due to a meaningful doctor-patient relationship [42-45]. In the study by Haller et al. [

4], visits were less frequent than in the present one, and the study site was a health center for ambulatory treatment for various diseases, which included, but were not restricted to, psychiatric disorders. By contrast, the present study was performed in leading psychiatric clinics of Budapest or psychiatric departments of leading clinics. The investigators were well-known academics, including professors of the Semmelweis University, which is one of the most prestigious medical universities of Hungary. This environment may account for the differences in placebo effects observed in the present and the earlier study.

Meta-analyses suggest that in the case of psychiatric disorders, the placebo effect is nearly as large as, and contributes substantially to, the effect of active medications [45-46]. It was suggested that placebo effects should be encouraged in the clinic by creating an optimal treatment environment that enhances them [44-45]. In a research context, however, placebo effects decrease the chance of identifying true medication effects. In our study, EP107TM-Echinacea proved superior to placebo according to HADS-A. As such, it may be considered as an active medication for anxiety.

However, Echinacea did not surpass placebo in the case of HAM-A, a standard and frequently used measure of anxiety. Regarding this discrepancy, one can formulate several hypotheses. As the ability of various tests to detect the anxiolytic effects of agents is variable [20-23], one can hypothesize that the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and the HADS-A are, whereas the HAM-A, and the CUXOS are not appropriate to test the anxiolytic effects of Echinacea. This assumption is supported by this and earlier studies. A second hypothesis would suggest that HAM-A scores were not improved by Echinacea because placebo alone abolished HAM-A anxiety, which could not be exceeded by active treatment. In support of this assumption, placebo decreased CUXOS scores below the cutoff score for anxiety in the study by Lopresti and Smith [

5]. Again, abolished anxiety cannot be improved further. In this context, positive findings with HADS-A may be because this is a self-assessment instrument, and as such, it could be administered more frequently, which allowed the detection of early effects when placebo alone did not yet abolish anxiety.

An alternative explanation is that Echinacea was effective against psychic but ineffective against somatic signs of anxiety. Lopresti and Smith [

5] already mentioned this possibility when comparing their findings with those of Haller et al. [

4]. They pointed out that all 40 items of the STAI investigate psychic anxiety, whereas 70% of CUXOS items investigate somatic anxiety. There is a similar difference between HADS-A and HAM-A. The former exclusively investigates psychic anxiety, whereas most items of the latter ask about somatic complaints elicited by anxious feelings. As such, one can hypothesize that Echinacea is effective against psychic anxiety and ineffective against somatic symptoms. This assumption is strengthened by the positive effects of Echinacea on three psychic items of HAM-A.

The two main limitations of the study are related to sample size and the large placebo effect. The necessary sample size was calculated according to accepted principles (see above), and in conformity to the expectations, the sample size was sufficient to evidence significant changes over the trial. However, the sample size was well below those generally employed by studies on the efficacy of anxiolytics, and additional trials in larger study populations are required to support the validity of the findings reported here. Placebo effects were surprisingly strong in this study. By the end of the treatment period, anxiety decreased substantially in both groups; moreover, the anxiety scores were similar in the placebo and Echinacea groups by the end of the treatment period (day 42). Additional studies are required to investigate whether faster, and larger effects at early phases of investigation also benefit the patients in the long run. This may be achieved by studying the decay of effect after washout periods of various lengths.

In conclusion, we found that EP107TM-Echinacea decreased anxiety more efficiently than placebo. The effect developed on the background of a favorable side-effect profile. Inconsistencies between anxiety tests are explained by a primordially psychic anxiety-decreasing effect of Echinacea. This suggests that the preparation is effective in mild forms or incipient phases of anxiety when somatic symptoms are not yet strong.

Anxiety disorders as well as anxieties associated with somatic illnesses frequently exhibit a variable course [47-51]. It has been proposed that patients experiencing fluctuating anxiety levels might benefit from fast acting therapy, particularly with benzodiazepines [47-49, 52-53]. On the other hand, a significant proportion of individuals with psychiatric disorders, particularly those experiencing depression and anxiety, opt for alternative therapies instead of conventional treatments [54-56]. The motivations for choosing non-conventional approaches are varied, encompassing personal beliefs about maintaining a healthy lifestyle and concerns about the potential side effects of standard medical treatments [54-57]. The results of our study indicate that the combined demand for fast-acting anxiolytics and the preference for non-conventional therapies can be addressed through the E. angustifolia extract evaluated in this research and previous studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JH, TFF; investigation, IB, GF, GK, GP; resources, JH, ZF; data curation, JH; writing—original draft preparation JH; writing—review and editing, JH, IB, GF, GK, GP, ZF, TFF; visualization, JH, ZF; supervision, JH, TFF; project administration, HJ, ZF; funding acquisition, JH, TFF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by an NKTH Jedlik Ányos grant to Anxiofit Ltd. represented by that time by JH and TFF.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, applicable Hungarian legislation on human studies and medical data protection, and the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice. It was approved by the National Institute of Pharmacy (Budapest, Hungary) under registration number OGYI/23775-6/2010.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data presented in this study are openly available in Zenodo at [DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.14261331]. Any additional inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the professional work performed by the team of Accelsiors CRO and its director Mihály Juhász. The authors also thank Eva Kertesz for her help in editing the final version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

TFF and JH are owners of Hungarian patent application No. P0600489, PCT patent application No. PCT/HU2007/000052, European patent application No. EP 07733869.7; US patent application No. 12/304 558 and Hong Kong patent application 09109349.0 concerning the use of Echinacea preparations for the treatment of anxiety. The funding source did not contribute to the study design, it was not involved in investigation, data collection, handling, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Aucoin M, Cooley K, Saunders PR, Carè J, Anheyer D, Medina DN, Cardozo V, Remy D, Hannan N, Garber A. The effect of Echinacea spp. on the prevention or treatment of COVID-19 and other respiratory tract infections in humans: A rapid review. Adv Integr Med. 2020 Dec;7(4):203-217. [CrossRef]

- Haller J, Hohmann J, Freund TF. The effect of Echinacea preparations in three laboratory tests of anxiety: comparison with chlordiazepoxide. Phytother Res. 2010 Nov;24(11):1605-13. [CrossRef]

- Haller J, Freund TF, Pelczer KG, Füredi J, Krecsak L, Zámbori J. The anxiolytic potential and psychotropic side effects of an echinacea preparation in laboratory animals and healthy volunteers. Phytother Res. 2013 Jan;27(1):54-61. [CrossRef]

- Haller J, Krecsak L, Zámbori J. Double-blind placebo controlled trial of the anxiolytic effects of a standardized Echinacea extract. Phytother Res. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lopresti AL, Smith SJ. An investigation into the anxiety-relieving and mood-enhancing effects of Echinacea angustifolia (EP107™): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2021 Oct 1;293:229-237. [CrossRef]

- Huang WJ, Chen WW, Zhang X. Endocannabinoid system: Role in depression, reward and pain control (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2016 Oct;14(4):2899-903. [CrossRef]

- Pertwee RG. Targeting the endocannabinoid system with cannabinoid receptor agonists: pharmacological strategies and therapeutic possibilities. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012 Dec 5;367(1607):3353-63. [CrossRef]

- Petrie GN, Nastase AS, Aukema RJ, Hill MN. Endocannabinoids, cannabinoids and the regulation of anxiety. Neuropharmacology. 2021 Sep 1;195:108626. [CrossRef]

- Piomelli D. The endocannabinoid system: a drug discovery perspective. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005 Jul;6(7):672-9. PMID: 16044662.

- Woelkart K, Xu W, Pei Y, Makriyannis A, Picone RP, Bauer R. The endocannabinoid system as a target for alkamides from Echinacea angustifolia roots. Planta Med. 2005 Aug;71(8):701-5. [CrossRef]

- Hohmann J, Rédei D, Forgo P, Szabó P, Freund TF, Haller J, Bojnik E, Benyhe S. Alkamides and a neolignan from Echinacea purpurea roots and the interaction of alkamides with G-protein-coupled cannabinoid receptors. Phytochemistry. 2011 Oct;72(14-15):1848-53. [CrossRef]

- Boonen J, Bronselaer A, Nielandt J, Veryser L, De Tré G, De Spiegeleer B. Alkamid database: Chemistry, occurrence and functionality of plant N-alkylamides. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012 Aug 1;142(3):563-90. [CrossRef]

- Hajos N, Holderith N, Németh B, Papp OI, Szabó GG, Zemankovics R, Freund TF, Haller J. The effects of an Echinacea preparation on synaptic transmission and the firing properties of CA1 pyramidal cells in the hippocampus. Phytother Res. 2012 Mar;26(3):354-62. [CrossRef]

- Woelkart K, Frye RF, Derendorf H, Bauer R, Butterweck V. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of dodeca-2E,4E,8E,10E/Z-tetraenoic acid isobutylamides after oral administration in rats. Planta Med. 2009 Oct;75(12):1306-13. [CrossRef]

- McNaughton N. Cognitive dysfunction resulting from hippocampal hyperactivity--a possible cause of anxiety disorder? Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997 Apr;56(4):603-11. [CrossRef]

- Bremner JD. Brain imaging in anxiety disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004 Mar;4(2):275-84. [CrossRef]

- Engin E, Treit D. The role of hippocampus in anxiety: intracerebral infusion studies. Behav Pharmacol. 2007 Sep;18(5-6):365-74. [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., & Lushene, R. E. (1970). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press.

- Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D, Dalrymple K. A clinically useful anxiety outcome scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010 May;71(5):534-42. [CrossRef]

- Hallgren JD, Morton JR, Neher JO. Clinical inquiries. What's the best way to screen for anxiety and panic disorders? J Fam Pract. 2007 Jul;56(7):579-80.

- Nelson HD, Cantor A, Pappas M, Weeks C. Screening for Anxiety in Adolescent and Adult Women: A Systematic Review for the Women's Preventive Services Initiative. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jul 7;173(1):29-41. [CrossRef]

- Hansen MV, Halladin NL, Rosenberg J, Gögenur I, Møller AM. Melatonin for pre- and postoperative anxiety in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 9;2015(4):CD009861. [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka LS, Atallah AN, Soares BG. Valerian for anxiety disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Oct 18;(4):CD004515. [CrossRef]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983 Jun;67(6):361-70. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50-5. [CrossRef]

- Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jönsson B, Olesen J, Allgulander C, Alonso J, Faravelli C, Fratiglioni L, Jennum P, Lieb R, Maercker A, van Os J, Preisig M, Salvador-Carulla L, Simon R, Steinhausen HC. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011 Sep;21(9):655-79. [CrossRef]

- Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study, Pharmaceutical Statistics, 2005, Vol 4, pp. 287–291.

- Bakker A, van Dyck R, Spinhoven P, van Balkom AJ. Paroxetine, clomipramine, and cognitive therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999 Dec;60(12):831-8. [CrossRef]

- Thewissen V, Bentall RP, Oorschot M, A Campo J, van Lierop T, van Os J, Myin-Germeys I. Emotions, self-esteem, and paranoid episodes: an experience sampling study. Br J Clin Psychol. 2011 Jun;50(2):178-95. [CrossRef]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 20:22-33. PMID: 9881538.

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961 Jun;4:561-71. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale--a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997 Jan;42(1):17-41. [CrossRef]

- Möller HJ. Standardised rating scales in psychiatry: methodological basis, their possibilities and limitations and descriptions of important rating scales. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(1):6-26. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 1983; 24(4), 385-396.

- Dunlop BW, Gray J, Rapaport MH. Transdiagnostic Clinical Global Impression Scoring for Routine Clinical Settings. Behav Sci (Basel). 2017 Jun 27;7(3):40. [CrossRef]

- Matza LS, Morlock R, Sexton C, Malley K, Feltner D. Identifying HAM-A cutoffs for mild, moderate, and severe generalized anxiety disorder. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010 Dec;19(4):223-32. [CrossRef]

- Balázs J. A M.I.N.I. és a M.I.N.I. PLUSZ kérdoív magyar nyelvu változatának kidolgozása és alkalmazása a gyakorlatban - öngyilkossági kísérletet elkövetett személyek vizsgálata. PhD thesis, Semmelweis University, 2002.

- Muszbek K., Szekely a., Balogh E. M., Molnar M. et al.: Validation of the Hungarian translation of Hospital anxiety and depression scale. Qual Life Res 15: 761–766, 2006.

- Rózsa S., Szádóczky E., Schmidt V., Füredi J.: a Hamilton depresszió skála pszichometriai jellemzői depressziós betegek körében. Psychiatria Hungarica XViii: 251–262, 2003.

- Kopp M., Skrabski Á., Czakó L.: Összehasonlító mentálhigiénés vizsgálatokhoz ajánlott módszertan. Végeken 1: 4–24, 1990.

- Stauder A., Konkoly Thege B.: Az észlelt stressz kérdőív (Pss) magyar verziójának jellemzői. Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika 7: 203–216, 2006.

- Colloca L, Jonas WB, Killen J, Miller FG, Shurtleff D. Reevaluating the placebo effect in medical practice. Z Psychol. 2014;222(3):124-127. [CrossRef]

- Enck P, Klosterhalfen S. The placebo response in clinical trials-the current state of play. Complement Ther Med. 2013 Apr;21(2):98-101. [CrossRef]

- Jonas WB. Reframing placebo in research and practice. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011 Jun 27;366(1572):1896-904. [CrossRef]

- Moerman DE, Explanatory mechanisms for placebo effects: cultural influences and the meaning response. In: Guess HA, Kleinman A, Kusek JW, Engel LW (eds) The Science of the Placebo: Toward an Interdisciplinary Research Agenda. London, BMJ Publishing Group, 2002.

- Wampold BE, Minami T, Tierney SC, Baskin TW, Bhati KS. The placebo is powerful: estimating placebo effects in medicine and psychotherapy from randomized clinical trials. J Clin Psychol. 2005 Jul;61(7):835-54. [CrossRef]

- Imlah N. W. The episodic nature of anxiety and its treatment with oxazepam. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 1978 58(S274), 94–98. [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, L. (1984). Benzodiazepines in the treatment of acute anxiety. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 1984 8(sup4), 115–119. [CrossRef]

- Rickels, Karl, and Edward Schweizer. The clinical presentation of generalized anxiety in primary-care settings: practical concepts of classification and management. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 1997 PMID: 9363042.

- Brenes, G. A., Guralnik, J. M., Williamson, J. D., Fried, L. P., Simpson, C., Simonsick, E. M., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. The Influence of Anxiety on the Progression of Disability. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 2005 53(1), 34–39. [CrossRef]

- Cukor, D., Coplan, J., Brown, C., Friedman, S., Newville, H., Safier, M., … Kimmel, P. L. (2008). Anxiety Disorders in Adults Treated by Hemodialysis: A Single-Center Study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 2008 52(1), 128–136. [CrossRef]

- Rickels, K., & Schweizer, E. The spectrum of generalised anxiety in clinical practice: the role of short-term, intermittent treatment∗. British Journal of Psychiatry, 1998 173(S34), 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Rouillon, F. (2004). Long term therapy of generalized anxiety disorder. European Psychiatry, 1998 19(2), 96–101. [CrossRef]

- Astin, J. A. Why Patients Use Alternative Medicine. JAMA, 1998 279(19), 1548. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Arye, E., Frenkel, M., Klein, A., & Scharf, M. Attitudes toward integration of complementary and alternative medicine in primary care: Perspectives of patients, physicians and complementary practitioners. Patient Education and Counseling, 2008 70(3), 395–402. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, J., Garcia, M.K., Boatwright, D., Klein, K. Complementary and alternative medicine in mainstream public health: a role for research in fostering integration. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 2003 9(3), 441-445. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, G., Issakidis, C., & Carter, G. Shortfall in mental health service utilisation. British Journal of Psychiatry, 2001 179(05), 417–425. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).