Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

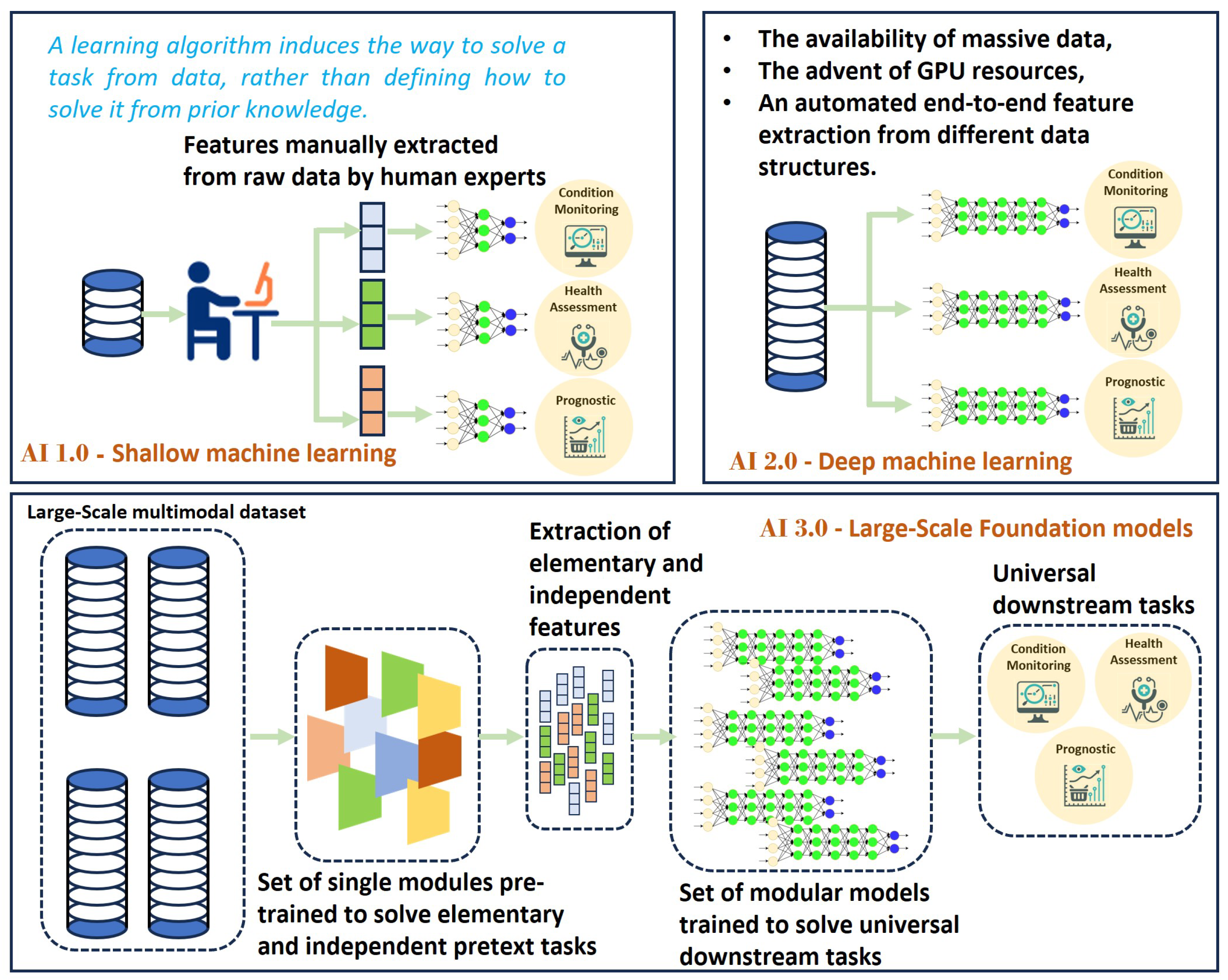

2. From Shallow Machine Learning to Foundation Models

2.1. Shallow Machine Learning

2.2. Deep Machine Learning

2.3. The Emergence of a New Concept, the Foundation Models

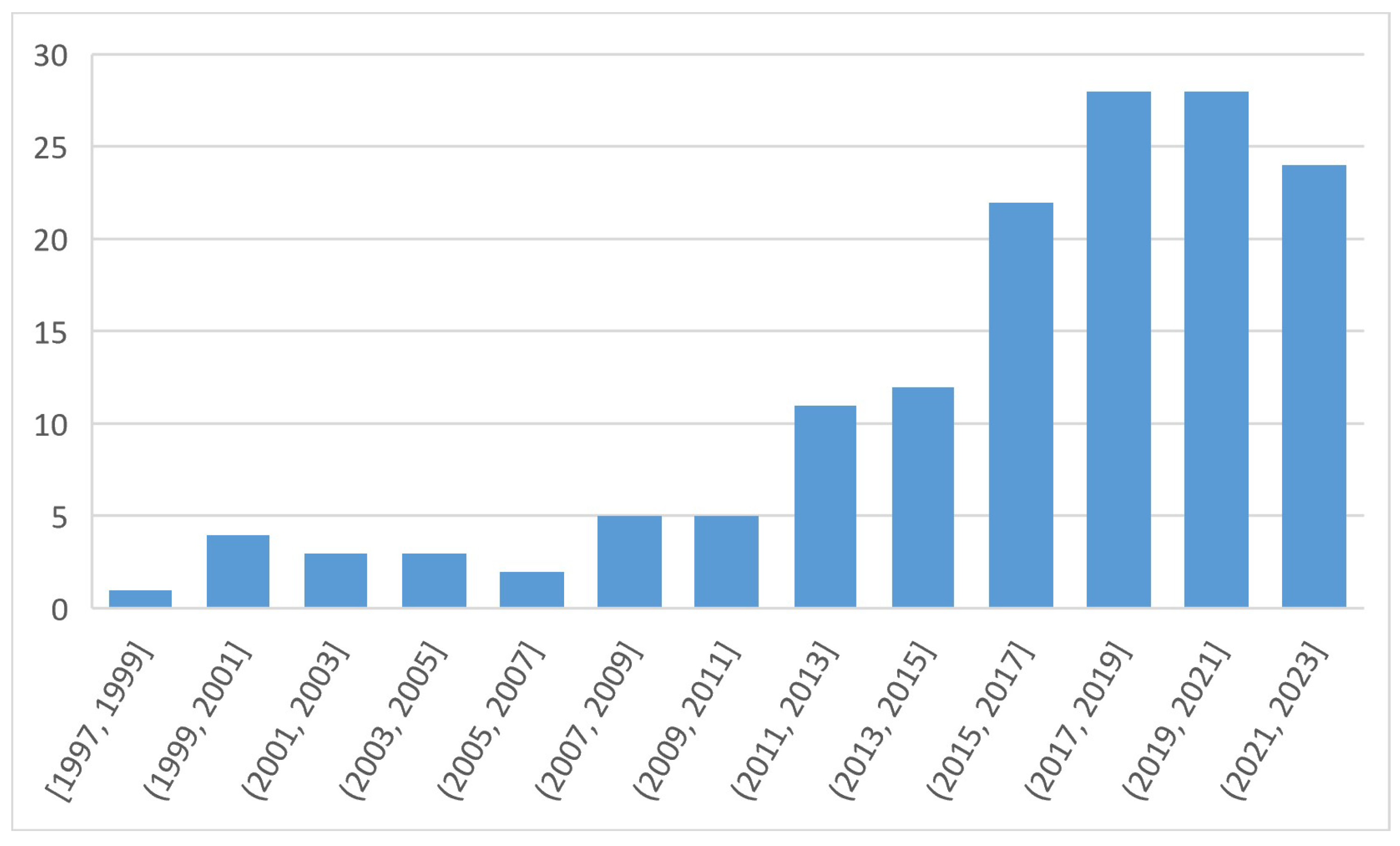

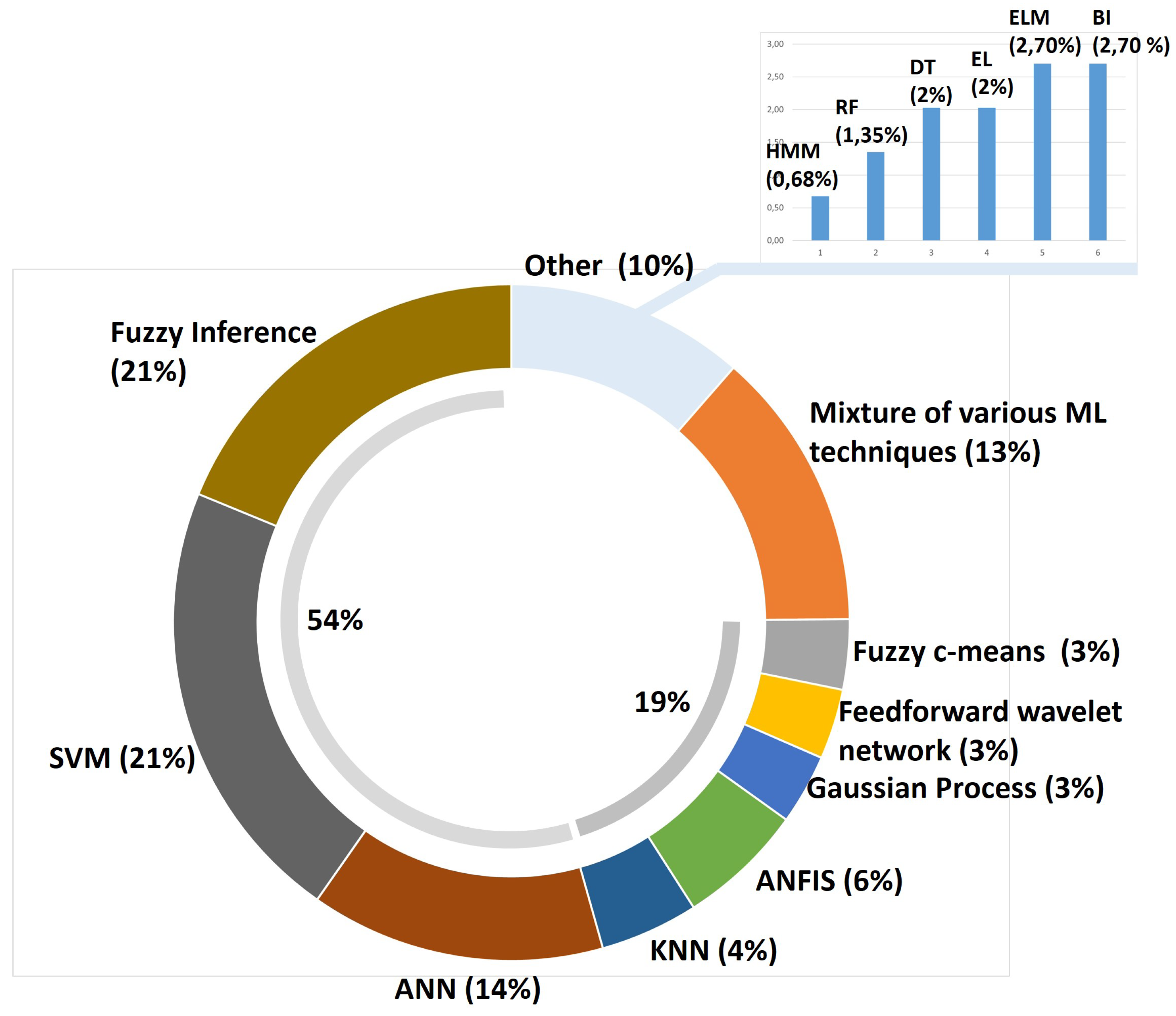

3. Classic ML Techniques

3.1. Artificial Neural Networks

3.2. Fuzzy Inference System

3.3. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

3.4. Summary of Work Using Classic ML methods

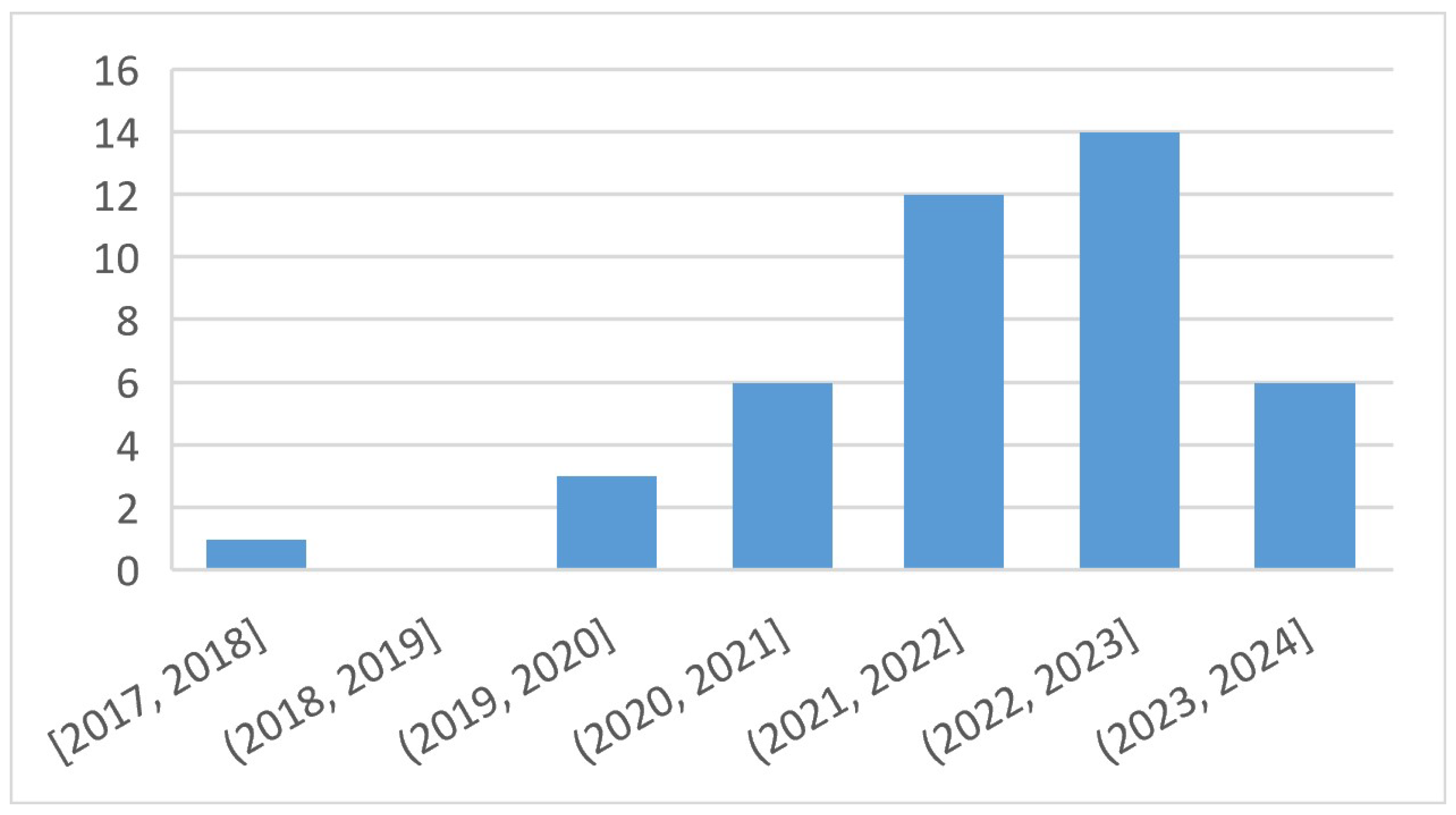

4. Deep Learning Architectures

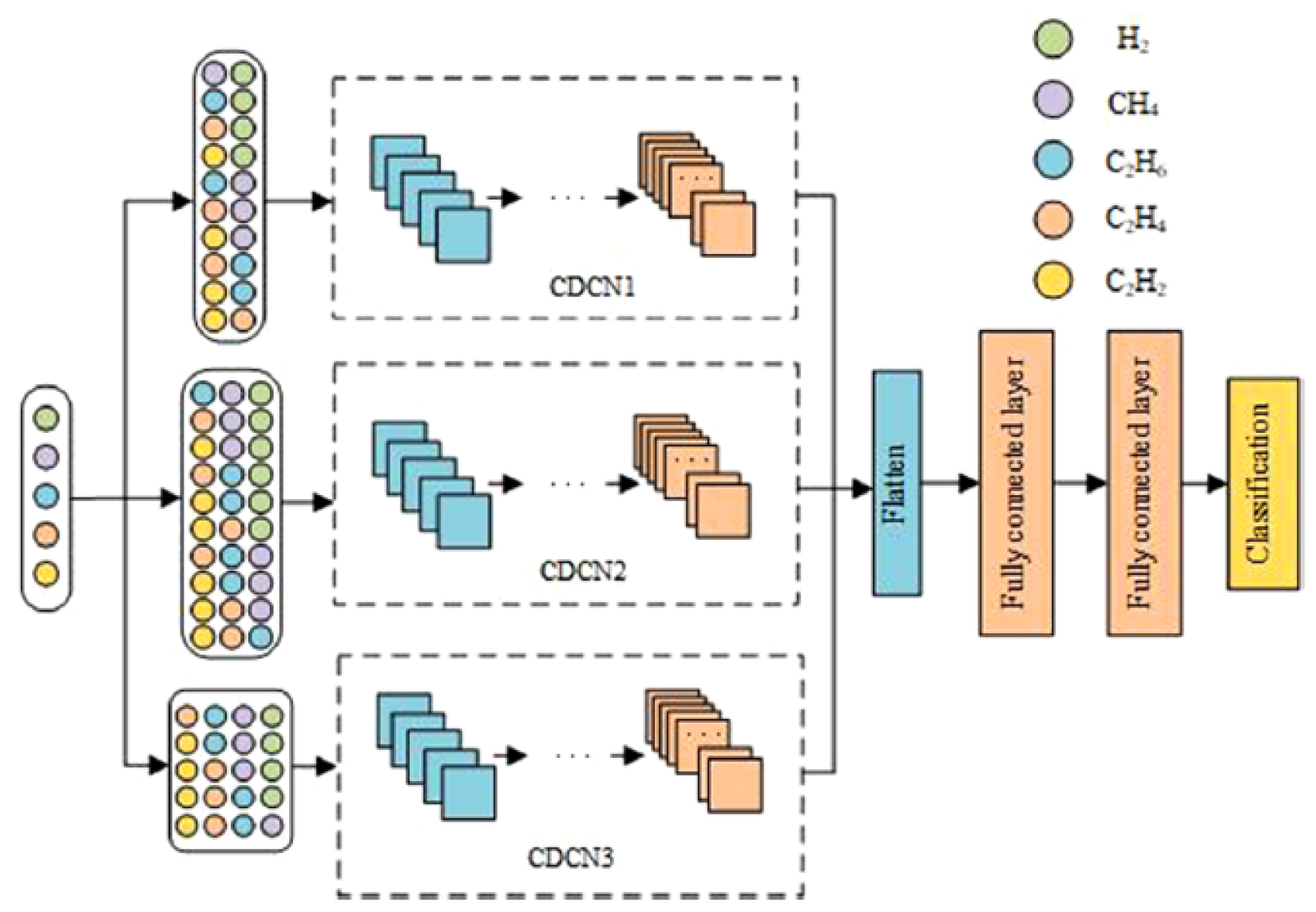

4.1. Convolutional Neural Networks

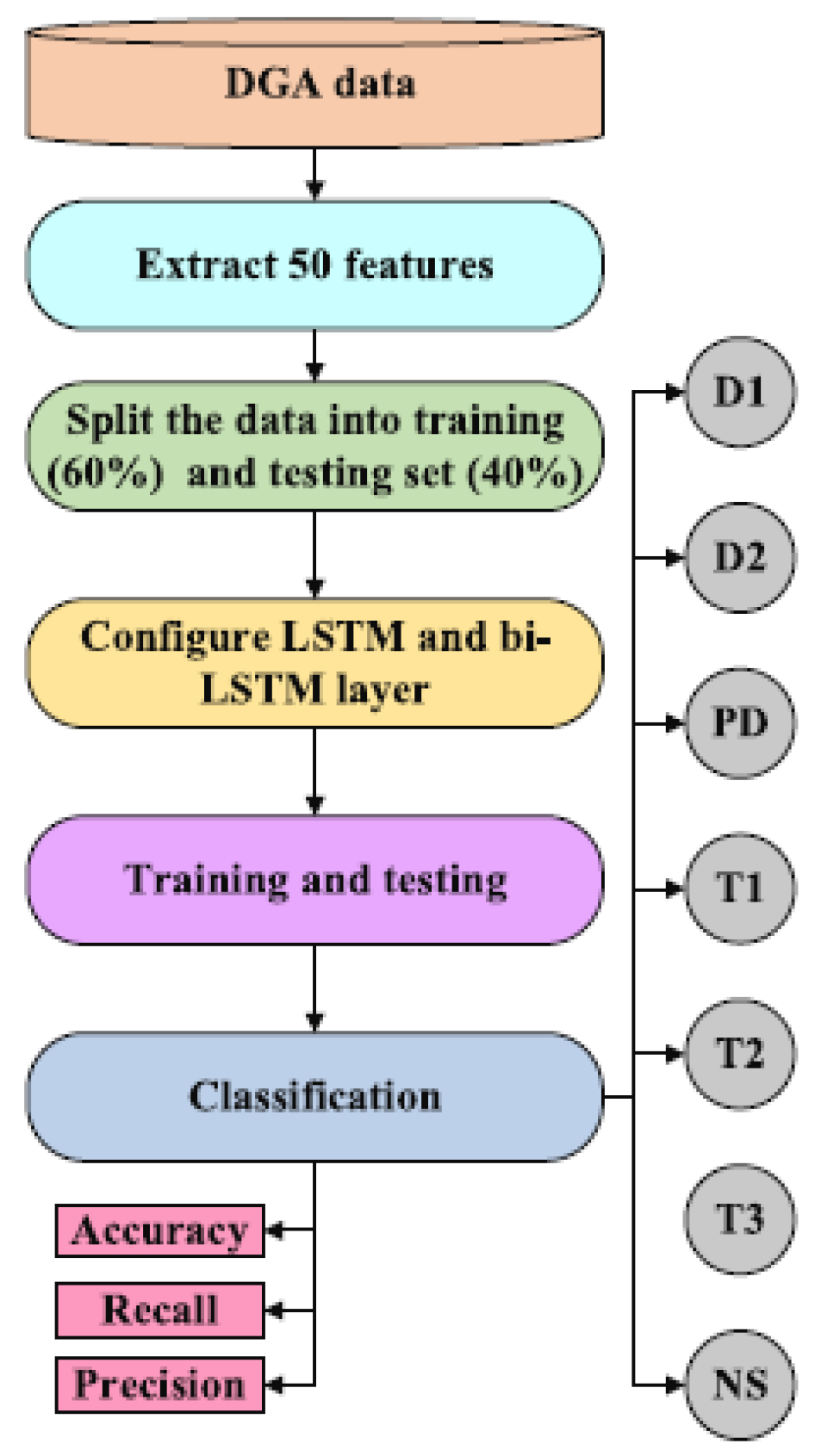

4.2. Recurrent Neural Network

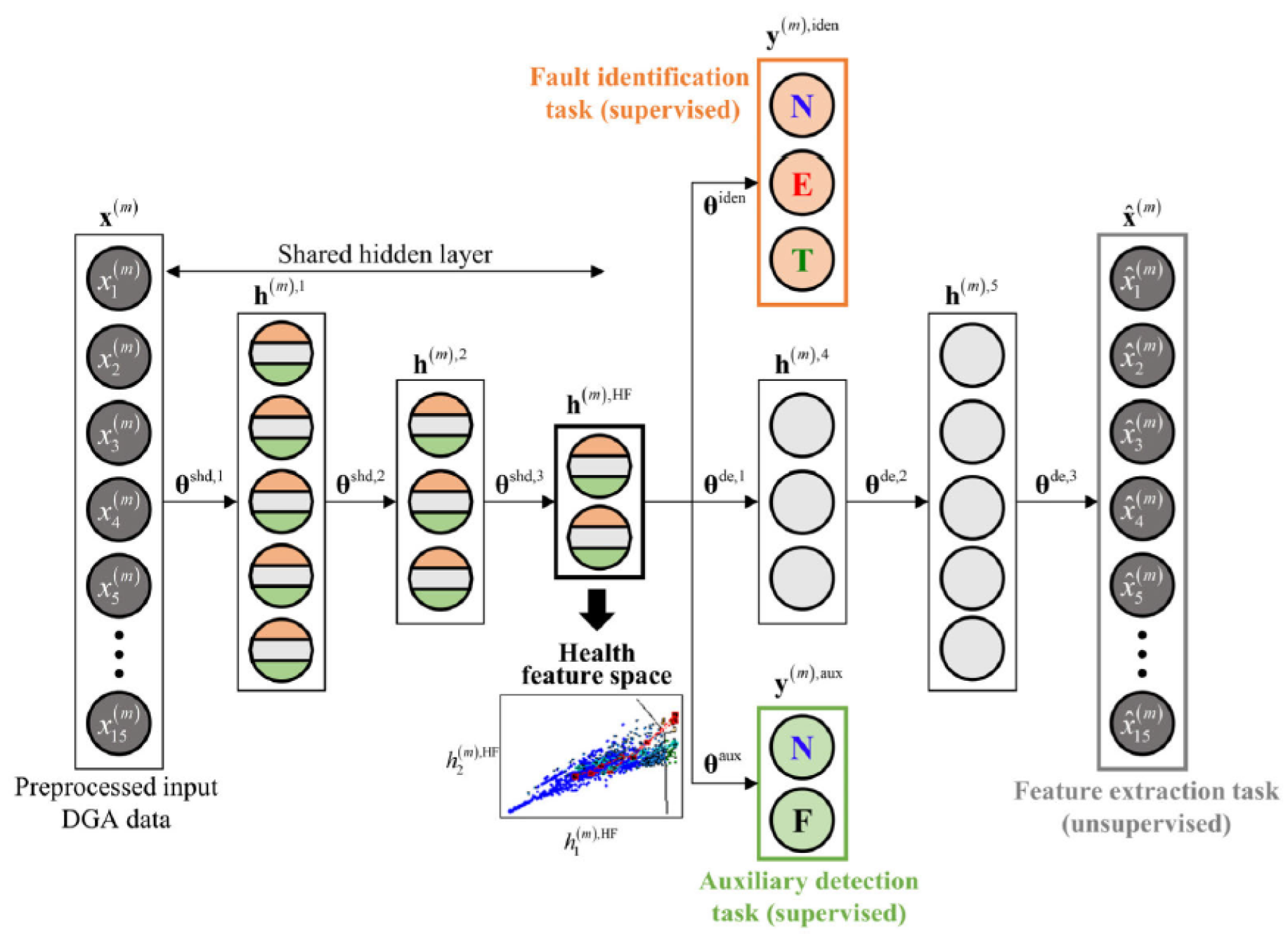

4.3. Auto-Encoders

4.4. Attention Mechanism

4.5. Graph Neural Networks

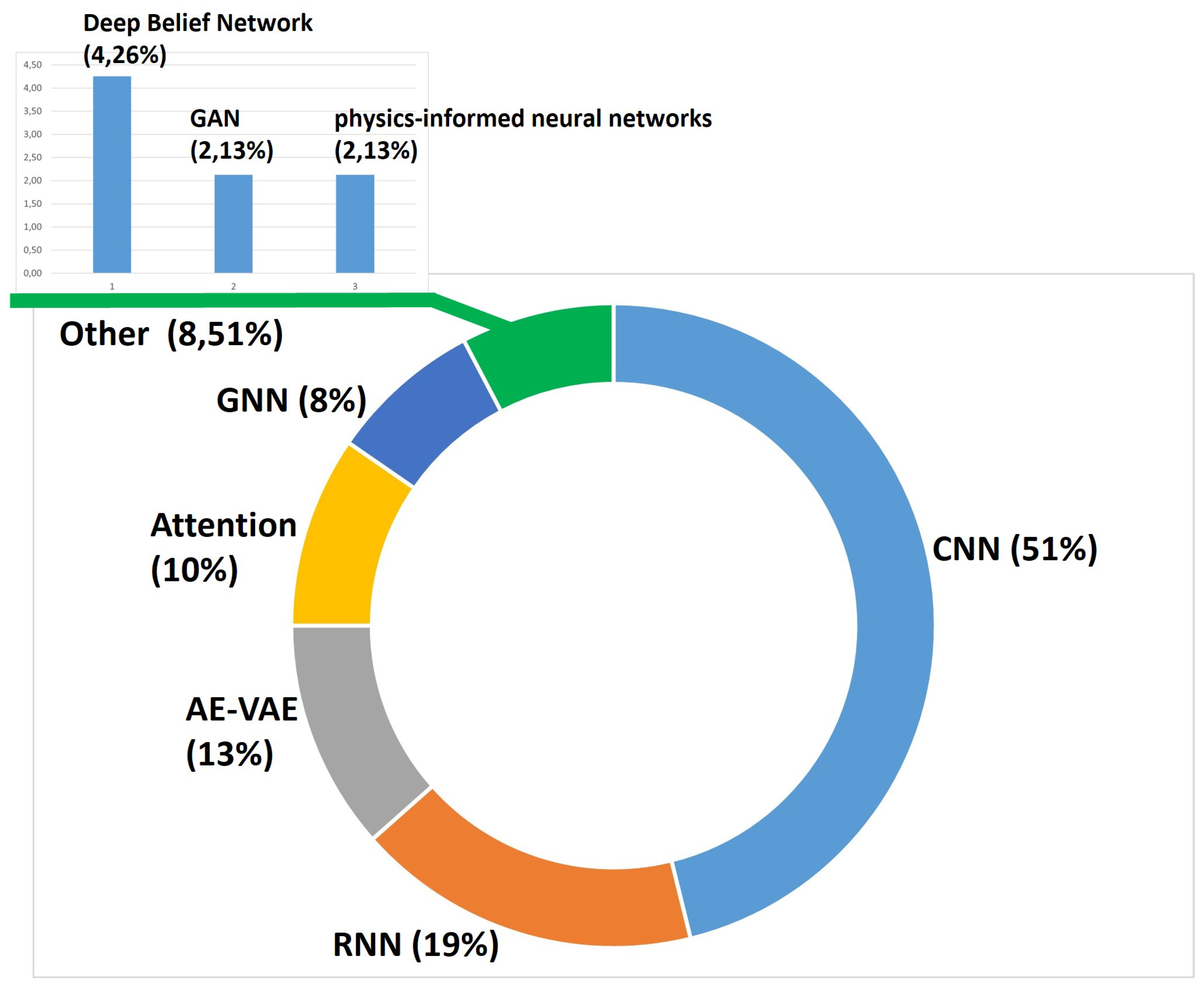

4.6. Summary of Work Using Deep Learning Architectures

| DL techniques | Task | Data | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | FDD | DGA | [174,175,176,177,178,179,180] |

| FDD | Other | [172,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188] | |

| HI | DGA | [189] | |

| HI | DGA+ | [190,191] | |

| Pred. | DGA | [192,193] | |

| Pred. | Other | [194,195,196] | |

| RNN | FDD | DGA | [197] |

| Pred. | DGA | [192,193,198,199] | |

| FDD | Other | [172,188] | |

| Pred. | Other | [195,196] | |

| AE-VAE | FDD | DGA | [180,200,201,202,203] |

| Pred. | DGA | [204] | |

| Attention | FDD | DGA | [177,179] |

| FDD | Other | [188] | |

| Pred. | DGA | [192] | |

| Pred. | Other | [196] | |

| GNN | FDD | DGA | [175] |

| HI | DGA+ | [205] | |

| Pred. | DGA | [193,206] | |

| DBN | FDD | DGA | [207,208] |

| GAN | FDD | DGA | [209] |

| PINNs | Pred. | Other | [210] |

5. What are the trends in AI and where do we need to go for the prognostics and the health management?

5.1. Modular Learning

- The learning module management phase which must meet the training, management and storage objectives of the modules.

- The routing phase which aims to define the way in which the modules are chosen and activated in order to meet a specific objective.

- The aggregation phase whose objective is to construct the final response from the responses of the various modules requested by the routing.

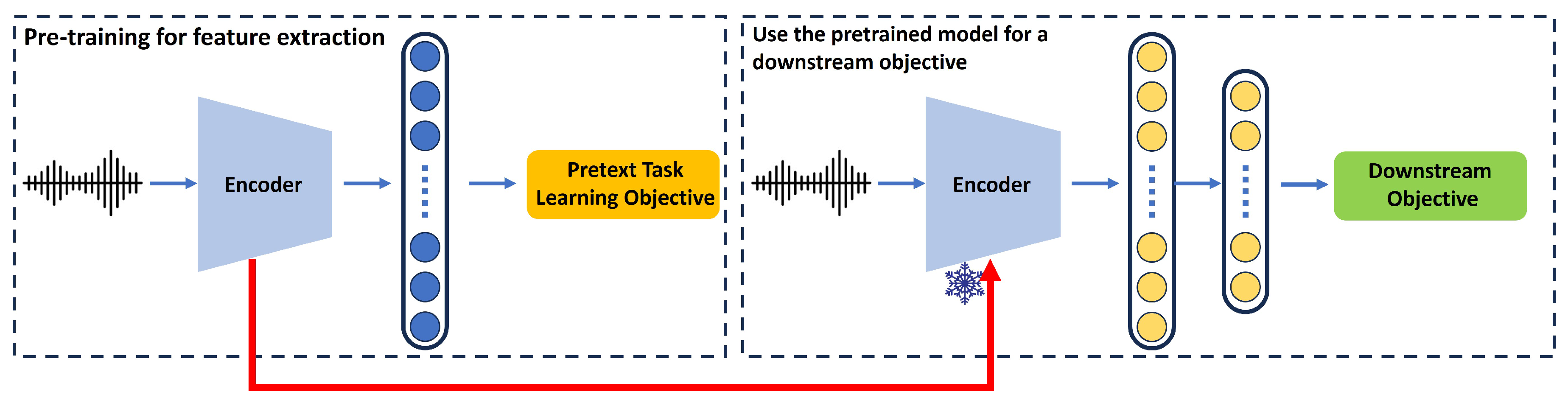

5.2. Self-Supervised Learning

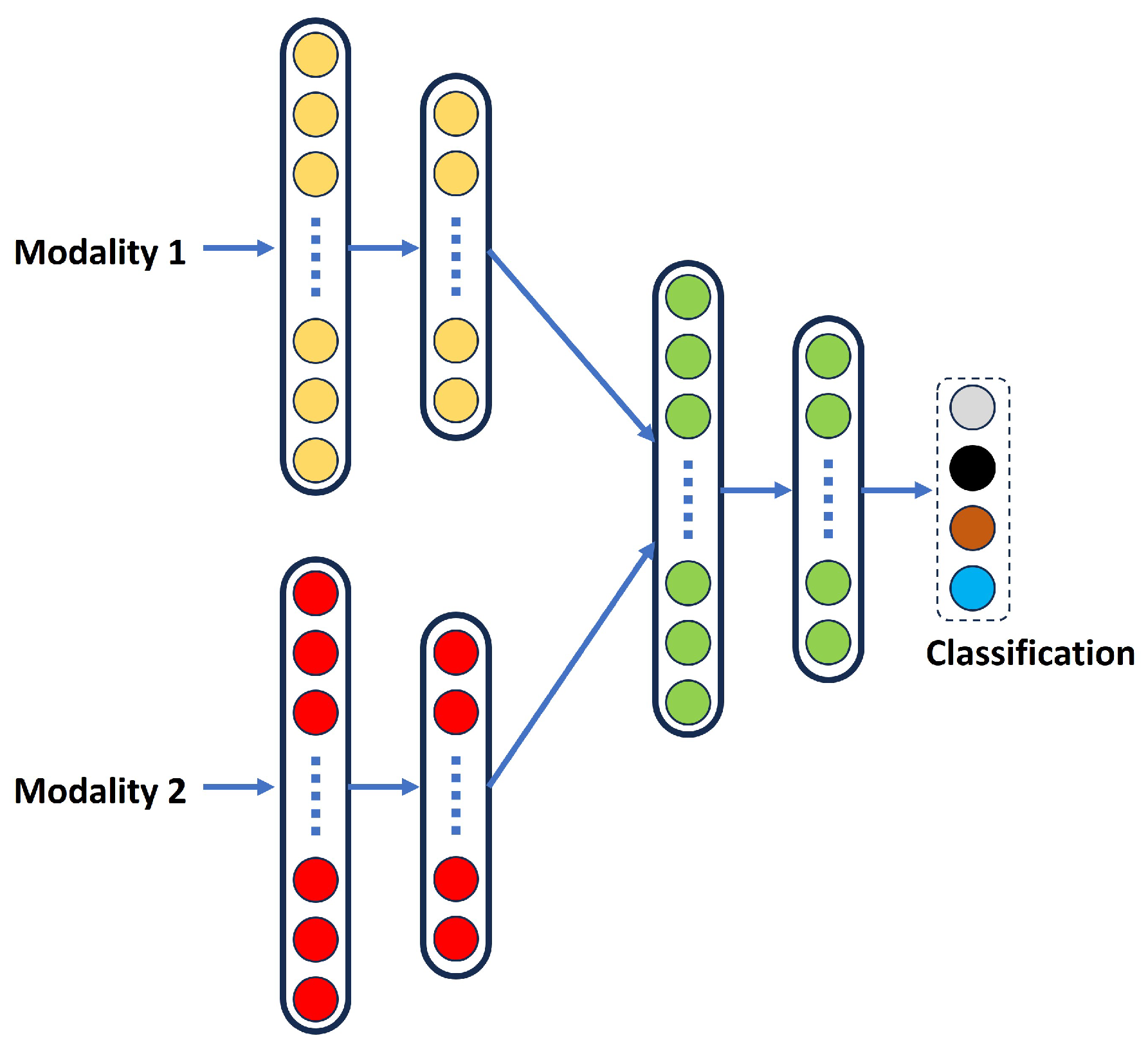

5.3. Multimodal Fusion

5.4. Towards the Foundation Models

6. What Are the Challenges?

6.1. Modularity of the LSF Models

6.2. Reliability of the LSF Models

- Quantifying uncertainty. Quantifying prediction uncertainty allows practitioners to know when to trust model predictions. Various metrics can be used to quantify the quality of uncertainty, such as expected calibration error, which measures how well confidence in the model matches its accuracy. Quantifying uncertainty also helps improve decision making; a popular framework is selective prediction, where a model can refer its prediction to human experts when it is uncertain. Another popular task is open-set recognition, where the model encounters inputs from new classes at test time that were not seen during training, and the goal is to reliably detect that these inputs belong to one of the training classes.

- Robust generalization. Robust generalization involves making an estimate or prediction about something that is not seen. Prediction quality is typically measured in terms of accuracy (e.g., top-1 error for classification problems and root mean square error for regression problems) and appropriate scoring rules such as log-likelihood and Brier score. In the real world, we are interested not only in measurements on new data from the same distribution on which the model was trained, but also in robustness, measured by measurements on data subject to non-distributional changes, such as changes in covariates or subpopulations.

- Adaptation. Adaptation consists of testing the capabilities of the model during its learning process. Benchmarks typically evaluate static datasets with a predefined split between training and testing. In many applications, however, we are interested in models that can quickly adapt to new data and learn efficiently with as few labeled examples as possible. Examples include few-shot learning, where the model learns from a small set of examples; active learning, where the model not only learns but also participates in the acquisition of the data from which it learns; and lifelong learning, where the model learns during a sequence of tasks and must not forget information relevant to previous tasks.

6.3. Explainability of the LSF Models

7. Conclusion

Abbreviations

| AE | Auto-Encoder |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANFIS | Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems |

| BI | Bayesian Inference |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DBN | Deep Belief Network |

| DGA | Dissolved Gas Analysis |

| DML | Deep Machine Learning |

| DNN | Deep Neural Networks |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| EL | Ensemble Learning |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| FDD | Fault Detection and diagnosis |

| FIS | Fuzzy Inference Systems |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| GP | Gaussian Proocess |

| HI | Health Index |

| HMM | Hidden Markov model |

| KNN | K-Nearnrest Neighbors |

| LSF | Large-scale foundation models |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MMF | Multimodal Fusion |

| MNN | Modular neural networks |

| MTL | Multi-Task Learning |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PHM | Prognostics and Health Management |

| PINN | Physics-Informed Neural Networks |

| PT | Power transformers |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SSL | Self Supervised Learning |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| VAE | Variational Auto-Encoder |

| WN | Wavelet Networks |

| XAI | eXplainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Dong, M.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, K.; Yao, S.; Kou, X.; Ding, G.; Guo, L. A Novel Maintenance Decision Making Model of Power Transformers Based on Reliability and Economy Assessment. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 28778–28790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Saha, T.K.; Ekanayake, C.; Martin, D. Smart Transformer for Smart Grid—Intelligent Framework and Techniques for Power Transformer Asset Management. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2015, 6, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziel, S.; Hilber, P.; Westerlund, P.; Shayesteh, E. Investments in data quality: Evaluating impacts of faulty data on asset management in power systems. Applied Energy 2021, 281, 116057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Sun, H.C. Dissolved gas analysis of mineral oil for power transformer fault diagnosis using fuzzy logic. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2013, 20, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.C.; Huang, Y.C.; Huang, C.M. Fault Diagnosis of Power Transformers Using Computational Intelligence: A Review. Energy Procedia 2012, 14, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Yu, T. Dissolved Gas Analysis Principle-Based Intelligent Approaches to Fault Diagnosis and Decision Making for Large Oil-Immersed Power Transformers: A Survey. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Z. Fault diagnosis of transformer using artificial intelligence: A review. Frontiers in Energy Research 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Littler, T.; Liu, X. Hybrid AI model for power transformer assessment using imbalanced DGA datasets. IET Renewable Power Generation 2023, 17, 1912–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Tian, Y. Self-Supervised Visual Feature Learning With Deep Neural Networks: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2021, 43, 4037–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, X.; Wei, M. A Review on Deep Learning Applications in Prognostics and Health Management. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 162415–162438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.B.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M.S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; et al. On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models. CoRR 2021, abs/2108.07258, [2108.07258]. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. 2019; arXiv:cs.CL/1810.04805]. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. 2020; arXiv:cs.CL/2005.14165]. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. 2021; arXiv:cs.CV/2103.00020]. [Google Scholar]

- Alqudsi, A.; El-Hag, A. Application of Machine Learning in Transformer Health Index Prediction. Energies 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohmad, A.; Shapiai, M.I.; Shamsudin, M.S.; Abu, M.A.; Hamid, A.A. Investigating performance of transformer health index in machine learning application using dominant features. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2021, 2128, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinoddini-Meymand, H.; Kamel, S.; Khan, B. An Efficient Approach With Application of Linear and Nonlinear Models for Evaluation of Power Transformer Health Index. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 150172–150186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, S.S.M.; Taha, I.B.M. Comparative Study of Full and Reduced Feature Scenarios for Health Index Computation of Power Transformers. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 181326–181339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Si, J.; Tylavsky, D. Prediction of top-oil temperature for transformers using neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2000, 15, 1205–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolgindachbaporn, A.; Callender, G.; Lewin, P.L.; Simonson, E.; Wilson, G. Data Driven Transformer Thermal Model for Condition Monitoring. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2022, 37, 3133–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardado, J.; Naredo, J.; Moreno, P.; Fuerte, C. A comparative study of neural network efficiency in power transformers diagnosis using dissolved gas analysis. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2001, 16, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F.R.; Almeida, O.M.; Braga, A.P.; Amora, M.A.; Cartaxo, S.J. Application of an artificial neural network in the use of physicochemical properties as a low cost proxy of power transformers DGA data. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2012, 19, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, D.; Bansal, R.K.; Gupta, H.O. Function analysis based rule extraction from artificial neural networks for transformer incipient fault diagnosis. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2012, 43, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.T.; Hu, L.S. Intelligent fault types diagnostic system for dissolved gas analysis of oil-immersed power transformer. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2013, 20, 2317–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, S.S.M.; Taha, I.B.M.; Elkalashy, N.I. Integrated ANN-based proactive fault diagnostic scheme for power transformers using dissolved gas analysis. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2016, 23, 1838–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illias, H.A.; Chai, X.R.; Abu Bakar, A.H. Hybrid modified evolutionary particle swarm optimisation-time varying acceleration coefficient-artificial neural network for power transformer fault diagnosis. Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation 2016, 90, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, R.M.A.; Lara, J.V.M. Root cause analysis improved with machine learning for failure analysis in power transformers. Engineering Failure Analysis 2020, 115, 104684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, I.B.M.; Dessouky, S.S.; Ghoneim, S.S.M. Transformer fault types and severity class prediction based on neural pattern-recognition techniques. Electric Power Systems Research 2021, 191, 106899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.A.; Sanaye-Pasand, M. A Robust Multi-Layer Framework for Online Condition Assessment of Power Transformers. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2022, 37, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souahlia, S.; Bacha, K.; Chaari, A. MLP neural network-based decision for power transformers fault diagnosis using an improved combination of Rogers and Doernenburg ratios DGA. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2012, 43, 1346–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thango, B.A. On the Application of Artificial Neural Network for Classification of Incipient Faults in Dissolved Gas Analysis of Power Transformers. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 2022, 4, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappey, A.J.C.; Trappey, C.V.; Ma, L.; Chang, J.C.M. Intelligent engineering asset management system for power transformer maintenance decision supports under various operating conditions. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2015, 84, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidedin Mousavi, S.; Hekmati, A.; Sedighizadeh, M.; Bigdeli, M.; Bazargan, A. ANN based temperature compensation for variations in polarization and depolarization current measurements in transformer. Thermal Science and Engineering Progress 2020, 20, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setayeshmehr, A.; Akbari, A.; Borsi, H.; Gockenbach, E. On-line monitoring and diagnoses of power transformer bushings. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2006, 13, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigatos, G.; Siano, P. Power transformers’ condition monitoring using neural modeling and the local statistical approach to fault diagnosis. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2016, 80, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Lee, G.; Hettiwatte, S.N. Application of a general regression neural network for health index calculation of power transformers. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2017, 93, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Khan, R.; Das, S.K.; Sarker, S.K.; Islam, M.M.; Akter, M.; Muyeen, S.M. Power transformer health condition evaluation: A deep generative model aided intelligent framework. Electric Power Systems Research 2023, 218, 109201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappey, A.J.C.; Trappey, C.V.; Ma, L.; Chang, J.C. Integrating Real-Time Monitoring and Asset Health Prediction for Power Transformer Intelligent Maintenance and Decision Support. In Proceedings of the Engineering Asset Management - Systems, Professional Practices and Certification; Tse, P.W.; Mathew, J.; Wong, K.; Lam, R.; Ko, C., Eds., Cham; 2015; pp. 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhmed, K.; Mooman, A.; Younes, A.; Shaban, K.; El-Hag, A. Feature Selection for Effective Health Index Diagnoses of Power Transformers. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2018, 33, 3223–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, A.; El-Hag, A. Assessing the power transformer insulation health condition using a feature-reduced predictor mode. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2018, 25, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ding, Z.; Fan, X.; Geng, C.; Song, B.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y. A BPNN Model-Based AdaBoost Algorithm for Estimating Inside Moisture of Oil–Paper Insulation of Power Transformer. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2022, 29, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshmand, R.A.; Parastegari, M.; Forghani, Z. Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system approach for simultaneous diagnosis of the type and location of faults in power transformers. IEEE Electrical Insulation Magazine 2012, 28, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Equbal, M.D.; Islam, T. A comprehensive comparative study of DGA based transformer fault diagnosis using fuzzy logic and ANFIS models. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2015, 22, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, T.; Gao, W.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Mo, W.; Wang, Y.; Luan, L. An integrated method of ANFIS and Dempster-Shafer theory for fault diagnosis of power transformer. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2018, 25, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, F.; Sun, Q.; Bin, F.; Liang, F.; Xiao, X. Hybrid RVM–ANFIS algorithm for transformer fault diagnosis. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2017, 11, 3637–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezami, M.M.; Equbal, M.D.; Khan, S.A.; Sohail, S. An ANFIS Based Comprehensive Correlation Between Diagnostic and Destructive Parameters of Transformer’s Paper Insulation. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2021, 46, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, R.D.; Zaldivar, D.A.; Romero, A.A.; Zuñiga, J.; Mombello, E.E. A fuzzy inference-based approach for estimating power transformers risk index. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 209, 108004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasojo, R.A.; Diwyacitta, K.; Suwarno. ; Gumilang, H. Transformer Paper Expected Life Estimation Using ANFIS Based on Oil Characteristics and Dissolved Gases (Case Study: Indonesian Transformers). Energies 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thango, B.A.; Bokoro, P.N. A Technique for Transformer Remnant Cellulose Life Cycle Prediction Using Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System. Processes 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, R.; Mehta, B. Diagnosis and prognosis of incipient faults and insulation status for asset management of power transformer using fuzzy logic controller & fuzzy clustering means. Electric Power Systems Research 2023, 220, 109256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganyun, L.; Haozhong, C.; Haibao, Z.; Lixin, D. Fault diagnosis of power transformer based on multi-layer SVM classifier. Electric Power Systems Research 2005, 74, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.; Zheng, H.; Grzybowski, S.; Yang, L. Particle swarm optimization-least squares support vector regression based forecasting model on dissolved gases in oil-filled power transformers. Electric Power Systems Research 2011, 81, 2074–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacha, K.; Souahlia, S.; Gossa, M. Power transformer fault diagnosis based on dissolved gas analysis by support vector machine. Electric Power Systems Research 2012, 83, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Tang, W.; Wu, Q. Dissolved gas analysis method based on novel feature prioritisation and support vector machine. IET Electric Power Applications 2014, 8, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, K.; Sun, J.; Xie, L. A Novel Integrated Method to Diagnose Faults in Power Transformers. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wei, H.; Zhao, J.; Liao, R. A novel model based on wavelet LS-SVM integrated improved PSO algorithm for forecasting of dissolved gas contents in power transformers. Electric Power Systems Research 2018, 155, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Q.; Yu, F.; Xuan, M. Transformer fault diagnosis method based on improved whale optimization algorithm to optimize support vector machine. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmahamed, Y.; Kherif, O.; Teguar, M.; Boubakeur, A.; Ghoneim, S.S.M. Accuracy Improvement of Transformer Faults Diagnostic Based on DGA Data Using SVM-BA Classifier. Energies 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, X.; Cheng, L. A Power Transformer Fault Diagnosis Method-Based Hybrid Improved Seagull Optimization Algorithm and Support Vector Machine. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 17268–17286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmahamed, Y.; Teguar, M.; Boubakeur, A. Application of SVM and KNN to Duval Pentagon 1 for transformer oil diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2017, 24, 3443–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhini, A.; Surjandari, I.; Kusumoputro, B.; Faqih, A.; Kusiak, A. Data-driven Fault Diagnosis of Power Transformers using Dissolved Gas Analysis (DGA). International Journal of Technology 2020, 11, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, T.; Gao, W.; Zhao, D.; Abiderexiti, K.; Mo, W.; Wang, Y.; Luan, L. Hybrid feature selection approach for power transformer fault diagnosis based on support vector machine and genetic algorithm. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2018, 12, 5672–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illias, H.A.; Zhao Liang, W. Identification of transformer fault based on dissolved gas analysis using hybrid support vector machine-modified evolutionary particle swarm optimisation. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Saha, T.K.; Ekanayake, C. Predictive learning and information fusion for condition assessment of power transformer. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting; 2011; pp. 1–9925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thango, B.A. Dissolved Gas Analysis and Application of Artificial Intelligence Technique for Fault Diagnosis in Power Transformers: A South African Case Study. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xu, G.; Sun, S.; Wang, E.; Pang, Y. A fault diagnostic method for oil-immersed transformer based on multiple probabilistic output algorithms and improved DS evidence theory. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2022, 137, 107828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shahidehpour, M.; Wu, M. A novel SVM-based decision framework considering feature distribution for Power Transformer Fault Diagnosis. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 9392–9401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Paramane, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Rao, U.M. Accurate Identification of Transformer Faults From Dissolved Gas Data Using Recursive Feature Elimination Method. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2023, 30, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Huang, F. A novel intelligent fault diagnosis method for electrical equipment using infrared thermography. Infrared Physics & Technology 2015, 73, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Tang, C.; Zhou, Q.; Xu, L.; Gui, Y.; Yao, C. Identification of Power Transformer Winding Mechanical Fault Types Based on Online IFRA by Support Vector Machine. Energies 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A. Power Transformer Condition Monitoring and Diagnosis. The Institution of Engineering and Technology: Stevenage, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Prasojo, R.A.; et al. Power transformer paper insulation assessment based on oil measurement data using SVM-classifier. International Journal on Electrical Engineering and Informatics 2018, 10, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, A.; Maria, L.D.; Valecillos, B.; Bartalesi, D.; Garatti, S.; Bittanti, S. A Machine Learning approach to fault detection in transformers by using vibration data. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2020, 53, 13656–13661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H. Moisture Prediction of Transformer Oil-Immersed Polymer Insulation by Applying a Support Vector Machine Combined with a Genetic Algorithm. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias Velásquez, R.M. Support vector machine and tree models for oil and Kraft degradation in power transformers. Engineering Failure Analysis 2021, 127, 105488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, Z.; Naseri, F.; Yazdi, M.; Farjah, E. An EKF-SVM machine learning-based approach for fault detection and classification in three-phase power transformers. IET Science, Measurement & Technology 2021, 15, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkezari, A.D.; Ma, H.; Saha, T.K.; Cui, Y. Investigation of feature selection techniques for improving efficiency of power transformer condition assessment. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2014, 21, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Sharkawy, R.; Temraz, H.; Salama, M. Selection criteria for oil transformer measurements to calculate the Health Index. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2016, 23, 3397–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, R.; Meena, V.S.; Negi, A.S.; Jarial, R. Ranking of power transformers on the basis of their health index and fault detection on the basis of DGA results using support vector machine (SVM). Int. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. Appl. Sci 2017, 5, 393–397. [Google Scholar]

- Wijethunge, T.; Tharkana, P.; Wimalaweera, A.; Wijayakulasooriya, J.; Kumara, S.; Bandara, K.; Fernando, M. A Machine Learning Approach for FDS Based Power Transformer Moisture Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena (CEIDP); 2021; pp. 539–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Saha, T.K.; Ekanayake, C. Statistical learning techniques and their applications for condition assessment of power transformer. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2012, 19, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Ekanayake, C.; Saha, T.K. Power transformer fault diagnosis under measurement originated uncertainties. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2012, 19, 1982–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahri, Z.; Yusof, R.; Watada, J. FINNIM: Iterative Imputation of Missing Values in Dissolved Gas Analysis Dataset. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2014, 10, 2093–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkezari, A.D.; Ma, H.; Saha, T.K.; Ekanayake, C. Application of fuzzy support vector machine for determining the health index of the insulation system of in-service power transformers. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2013, 20, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ge, Z.; Abu-Siada, A.; Yang, L.; Li, S.; Wakimoto, K. A New Technique to Estimate the Degree of Polymerization of Insulation Paper Using Multiple Aging Parameters of Transformer Oil. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 157471–157479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.; Ribeiro, M.; Leitão, A.; Guimarães, L.; Carvalho, L.; Matos, M.A.; Bessa, R.J. An unsupervised approach for fault diagnosis of power transformers. Quality and Reliability Engineering International 2021, 37, 2834–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, T.; Kim, S.; Kwak, N.; Kweon, D. Artificial Intelligent Fault Diagnostic Method for Power Transformers using a New Classification System of Faults. Journal of Electrical Engineering & Technology 2019, 14, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanfilyeva, D.V.; Tanfyev, O.V.; Kazantsev, Y.V. K-nearest neighbor method for power transformers condition assessment. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 643, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kherif, O.; Benmahamed, Y.; Teguar, M.; Boubakeur, A.; Ghoneim, S.S.M. Accuracy Improvement of Power Transformer Faults Diagnostic Using KNN Classifier With Decision Tree Principle. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 81693–81701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanfak, A.; Eke, S.; Meghnefi, F.; Fofana, I.; Ngaleu, G.M.; Kom, C.H. Hybrid DGA Method for Power Transformer Faults Diagnosis Based on Evolutionary k-Means Clustering and Dissolved Gas Subsets Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2023, 30, 2421–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbaji, M.; Shaban, K.; El-Hag, A. Classification of common partial discharge types in oil-paper insulation system using acoustic signals. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2015, 22, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunicki, M.; Wotzka, D. A Classification Method for Select Defects in Power Transformers Based on the Acoustic Signals. Sensors 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.C.; Yang, H.T.; Huang, C.L. Developing a new transformer fault diagnosis system through evolutionary fuzzy logic. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 1997, 12, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mofizul Islam, S.; Wu, T.; Ledwich, G. A novel fuzzy logic approach to transformer fault diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2000, 7, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Mi, C.; Lai, L.; Austin, P. A fuzzy dissolved gas analysis method for the diagnosis of multiple incipient faults in a transformer. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2000, 15, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H. A novel extension method for transformer fault diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2003, 18, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, R.; Sharma, V.; Vashisth, M. An Integrated Neural Fuzzy Approach for Fault Diagnosis of Transformers. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2008, 23, 2017–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, J.; Gholami, A.; Shayanfar, H.A.; Dezhamkhooy, A. Dissolved gas analysis of transformers using fuzzy logic approach. European Transactions on Electrical Power 2010, 20, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Siada, A.; Hmood, S. A new fuzzy logic approach to identify power transformer criticality using dissolved gas-in-oil analysis. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2015, 67, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irungu, G.K.; Akumu, A.O.; Munda, J.L. A new fault diagnostic technique in oil-filled electrical equipment; the dual of Duval triangle. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2016, 23, 3405–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, M.; Effatnejad, R.; Hajihosseini, P. Using dissolved gas analysis results to detect and isolate the internal faults of power transformers by applying a fuzzy logic method. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2017, 11, 2721–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, R.M.A.; Lara, J.V.M. Principal Components Analysis and Adaptive Decision System Based on Fuzzy Logic for Power Transformer. Fuzzy Information and Engineering 2017, 9, 493–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, N.; Samimi, M.H.; Mohseni, H. Experiences with transformer diagnosis by DGA: case studies. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2019, 13, 5431–5439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.A.; Gupta, D.; Farooque, M.U.; Khan, S.A. Multiple incipient fault classification approach for enhancing the accuracy of dissolved gas analysis (DGA). IET Science, Measurement & Technology 2019, 13, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žarković, M.; Stojković, Z. Analysis of artificial intelligence expert systems for power transformer condition monitoring and diagnostics. Electric Power Systems Research 2017, 149, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Galil, T.; Sharkawy, R.; Salama, M.; Bartnikas, R. Partial discharge pattern classification using the fuzzy decision tree approach. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2005, 54, 2258–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secue, J.; Mombello, E. Sweep frequency response analysis (SFRA) for the assessment of winding displacements and deformation in power transformers. Electric Power Systems Research 2008, 78, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Siada, A.; Lai, S.P.; Islam, S.M. A Novel Fuzzy-Logic Approach for Furan Estimation in Transformer Oil. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2012, 27, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejmert, D.; Rebizant, W.; Schiel, L. Transformer differential protection with fuzzy logic based inrush stabilization. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2014, 63, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, G.M.; de Aquino, R.R.B.; Lira, M.M.S. Thermography and artificial intelligence in transformer fault detection. Electrical Engineering 2018, 100, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Fan, X.; Liu, J.; Li, J. Prediction of Moisture and Aging Conditions of Oil-Immersed Cellulose Insulation Based on Fingerprints Database of Dielectric Modulus. Polymers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, G.C.; Ballal, M.S.; Tutakne, D. Health index based condition monitoring of distribution transformer. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Dec 2016, Drives and Energy Systems (PEDES); pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Ranga, C.; Chandel, A.K.; Chandel, R. Fuzzy Logic Expert System for Optimum Maintenance of Power Transformers. International Journal on Electrical Engineering & Informatics 2016, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Ranga, C.; Chandel, A.K.; Chandel, R. Expert system for condition monitoring of power transformer using fuzzy logic. Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranga, C.; Chandel, A.K.; Chandel, R. Condition assessment of power transformers based on multi-attributes using fuzzy logic. IET Science, Measurement & Technology 2017, 11, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Quete, A.A.; Gómez, H.D.; Molina, J.D.; Moreno, G. A Practical method for risk assessment in power transformer fleets. Dyna 2017, 84, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadim, E.J.; Azis, N.; Jasni, J.; Ahmad, S.A.; Talib, M.A. Transformers Health Index Assessment Based on Neural-Fuzzy Network. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.P. Pandey, V.C., Pandey, P.M., Garg, S.K., Eds.; Regression Approach to Power Transformer Health Assessment Using Health Index. In Proceedings of the Advances in Electromechanical Technologies; Singapore, 2021; pp. 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, R.; Zheng, H.; Grzybowski, S.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Y. An Integrated Decision-Making Model for Condition Assessment of Power Transformers Using Fuzzy Approach and Evidential Reasoning. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2011, 26, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Elanien, A.E.B.; Salama, M.M.A.; Ibrahim, M. Calculation of a Health Index for Oil-Immersed Transformers Rated Under 69 kV Using Fuzzy Logic. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2012, 27, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.; Goulermas, J.Y.; Wu, Q.H.; Richardson, Z.J.; Fitch, J. A Probabilistic Classifier for Transformer Dissolved Gas Analysis With a Particle Swarm Optimizer. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2008, 23, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizpurua, J.I.; Catterson, V.M.; Stewart, B.G.; McArthur, S.D.J.; Lambert, B.; Ampofo, B.; Pereira, G.; Cross, J.G. Power transformer dissolved gas analysis through Bayesian networks and hypothesis testing. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2018, 25, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ma, H.; Saha, T.; Wu, G. Bayesian information fusion for probabilistic health index of power transformer. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2018, 12, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarajcev, P.; Jakus, D.; Vasilj, J.; Nikolic, M. Analysis of Transformer Health Index Using Bayesian Statistical Models. In Proceedings of the 2018 3rd International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech); 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Odongo, G.; Musabe, R.; Hanyurwimfura, D. A Multinomial DGA Classifier for Incipient Fault Detection in Oil-Impregnated Power Transformers. Algorithms 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A.G.C.; Araujo, M.M.; Almeida, O.M.; Barbosa, F.R.; Braga, A.P.S. Induction of Decision Trees to Diagnose Incipient Faults in Power Transformers. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2022, 29, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarakhsh, J. The power transformer differential protection using decision tree. Bulletin de la Société Royale des Sciences de Liège 2017, 86, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Pan, C.; Yun, Y.; Liu, Y. Wavelet Networks in Power Transformers Diagnosis Using Dissolved Gas Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2009, 24, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C.; Huang, C.M. Evolving wavelet networks for power transformer condition monitoring. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2002, 17, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.C. A new data mining approach to dissolved gas analysis of oil-insulated power apparatus. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2003, 18, 1257–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, R.P.; Costa, F.B. A Wavelet-Based Transformer Differential Protection With Differential Current Transformer Saturation and Cross-Country Fault Detection. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2018, 33, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Elkhatib, M.; Salama, M.; Shaban, K.B. Transformer Health Index estimation using Orthogonal Wavelet Network. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Electrical Power and Energy Conference (EPEC), Oct 2015; pp. 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Yang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L. A Novel Transformers Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Probabilistic Neural Network and Bio-Inspired Optimizer. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Littler, T.; Liu, X. Gaussian Process Multi-Class Classification for Transformer Fault Diagnosis Using Dissolved Gas Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2021, 28, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Dong, Z.Y.; Wang, D.H.; Wong, K.P. A Self-Adaptive RBF Neural Network Classifier for Transformer Fault Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2010, 25, 1350–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Lee, G.; Hettiwatte, S.N.; Williams, K. Calculating a Health Index for Power Transformers Using a Subsystem-Based GRNN Approach. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2018, 33, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M. A Data-driven Long-Term Dynamic Rating Estimating Method for Power Transformers. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2021, 36, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, S.S.M.; Farrag, T.A.; Rashed, A.A.; El-Kenawy, E.S.M.; Ibrahim, A. Adaptive Dynamic Meta-Heuristics for Feature Selection and Classification in Diagnostic Accuracy of Transformer Faults. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 78324–78340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F.; Yu, D.; Zhang, C.; Gao, L. Fault Diagnosis of Oil-Immersed Power Transformer Based on Difference-Mutation Brain Storm Optimized Catboost Model. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 168767–168782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M. Transformer Dissolved Gas Analysis for Highly-Imbalanced Dataset Using Multiclass Sequential Ensembled ELM. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2023, 30, 2353–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, N.; Jamshed, A.; Chatterjee, K.; Chatterjee, S. Accurate Sensing of Power Transformer Faults From Dissolved Gas Data Using Random Forest Classifier Aided by Data Clustering Method. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 5902–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, Q.; Yang, J.; Xie, T.; Wu, P.; Liang, J. Transformer Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Incomplete Data and TPE-XGBoost. Applied Sciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, R.; Chen, M.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C. Dynamic Fault Prediction of Power Transformers Based on Hidden Markov Model of Dissolved Gases Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2019, 34, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhai, J. Fault diagnosis for oil-filled transformers using voting based extreme learning machine. Cluster Computing 2019, 22, 8363–8370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Ma, S.; Shi, Z.; An, G.; Du, Z.; Zhao, C. Transformer Fault Diagnosis Technology Based on Maximally Collapsing Metric Learning and Parameter Optimization Kernel Extreme Learning Machine. IEEJ Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Engineering 2022, 17, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Ma, S.; Shi, Z.; An, G.; Du, Z.; Zhao, C. A Novel Power Transformer Fault Diagnosis Model Based on Harris-Hawks-Optimization Algorithm Optimized Kernel Extreme Learning Machine. Journal of Electrical Engineering & Technology 2022, 17, 1993–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Huang, S.; Ma, S.; An, G.; An, Q.; Du, Z.; He, P. Fault diagnosis method for transformer based on NCA and CapSA-RELM. Electrical Engineering 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illias, H.A.; Chan, K.C.; Mokhlis, H. Hybrid feature selection–artificial intelligence–gravitational search algorithm technique for automated transformer fault determination based on dissolved gas analysis. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2020, 14, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shintemirov, A.; Tang, W.; Wu, Q.H. Power Transformer Fault Classification Based on Dissolved Gas Analysis by Implementing Bootstrap and Genetic Programming. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews) 2009, 39, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, V.; Castro, A. Improving the IEC table for transformer failure diagnosis with knowledge extraction from neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2005, 20, 2509–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraisamy, V.; Devarajan, N.; Somasundareswari, D.; Vasanth, A.A.M.; Sivanandam, S. Neuro fuzzy schemes for fault detection in power transformer. Applied Soft Computing 2007, 7, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiz, J.; Soleimani, M. Assessment of computational intelligence and conventional dissolved gas analysis methods for transformer fault diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2018, 25, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, U.M.; Fofana, I.; Rajesh, K.N.V.P.S.; Picher, P. Identification and Application of Machine Learning Algorithms for Transformer Dissolved Gas Analysis. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2021, 28, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoussaoui, M.E.A.; Brahami, M.; Fofana, I. Combining and comparing various machine-learning algorithms to improve dissolved gas analysis interpretation. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2018, 12, 3673–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Shi, C.; Fu, H.; Xu, Y. Research on transformer fault diagnosis based on ISOMAP and IChOA-LSSVM. IET Electric Power Applications 2023, 17, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, K.N.V.P.S.; Rao, U.M.; Fofana, I.; Rozga, P.; Paramane, A. Influence of Data Balancing on Transformer DGA Fault Classification With Machine Learning Algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2023, 30, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rediansyah, D.; Prasojo, R.A. ; Suwarno. In Study on Artificial Intelligence Approaches for Power Transformer Health Index Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICEEI); 2021; pp. 1–6830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinoddini-Meymand, H.; Vahidi, B. Health index calculation for power transformers using technical and economical parameters. IET Science, Measurement & Technology 2016, 10, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizpurua, J.I.; McArthur, S.D.J.; Stewart, B.G.; Lambert, B.; Cross, J.G.; Catterson, V.M. Adaptive Power Transformer Lifetime Predictions Through Machine Learning and Uncertainty Modeling in Nuclear Power Plants. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2019, 66, 4726–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunicki, M.; Borucki, S.; Cichoń, A.; Frymus, J. Modeling of the Winding Hot-Spot Temperature in Power Transformers: Case Study of the Low-Loaded Fleet. Energies 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, F.; Arcos, H.; Quilumba, F. Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for the Prediction of Mechanical Stress in Three-Phase Power Transformer Winding Conductors. Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering 2021, 2021, 4657696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. H. Wei, W.H.T.; Wu, Q.H. A Hybrid Least-square Support Vector Machine Approach to Incipient Fault Detection for Oil-immersed Power Transformer. Electric Power Components and Systems 2014, 42, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.A.; Rana, A.S.; Sohail, S.; Rahman, O.; Parveen, S.; Khan, S.A. Advances in DGA based condition monitoring of transformers: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 149, 111347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kari, T.; Gao, W.; Tuluhong, A.; Yaermaimaiti, Y.; Zhang, Z. Mixed Kernel Function Support Vector Regression with Genetic Algorithm for Forecasting Dissolved Gas Content in Power Transformers. Energies 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaiselvi, T.; Sriramakrishnan, P.; Somasundaram, K. Survey of using GPU CUDA programming model in medical image analysis. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked 2017, 9, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smistad, E.; Falch, T.L.; Bozorgi, M.; Elster, A.C.; Lindseth, F. Medical image segmentation on GPUs – A comprehensive review. Medical Image Analysis 2015, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eklund, A.; Dufort, P.; Forsberg, D.; LaConte, S.M. Medical image processing on the GPU – Past, present and future. Medical Image Analysis 2013, 17, 1073–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems - Volume 1, USA, 2012; NIPS’12; pp. 1097–1105.

- Lopes, S.M.d.A.; Flauzino, R.A.; Altafim, R.A.C. Incipient fault diagnosis in power transformers by data-driven models with over-sampled dataset. Electric Power Systems Research 2021, 201, 107519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlakić, D.; Nikolovski, S.; Majdandžić, L. Deep learning method and infrared imaging as a tool for transformer faults detection. Journal of Electrical Engineering 2018, 6, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Afrasiabi, S.; Afrasiabi, M.; Parang, B.; Mohammadi, M. Designing a composite deep learning based differential protection scheme of power transformers. Applied Soft Computing 2020, 87, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Paramane, A.; Rao, U.M.; Chatterjee, S.; Kumar, K.S. Corrosive Dibenzyl Disulfide Concentration Prediction in Transformer Oil Using Deep Neural Network. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2023, 30, 1608–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, Y.; Xing, Z.; Duan, J. Transformer fault diagnosis based on improved deep coupled dense convolutional neural network. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 209, 107969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Tian, J.; Li, J. A Semi-Supervised Fault Diagnosis Method for Transformers Based on Discriminative Feature Enhancement and Adaptive Weight Adjustment. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2024, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Fan, X.; Zhang, D. Improved multi-grained cascade forest model for transformer fault diagnosis. CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems 2022, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; He, Y.; Xing, Z. Dissolved Gas Analysis for Power Transformer Fault Diagnosis Based on Deep Zero-shot Learning. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2024, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ma, J.; Zhu, J. Hierarchical Federated Learning for Power Transformer Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, C.; Zhu, Q. Multichannel consecutive data cross-extraction with 1DCNN-attention for diagnosis of power transformer. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems 2024, 158, 109951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, J.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Y. Data augmentation for fault diagnosis of oil-immersed power transformer. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Jin, M.; Huang, H. Transformer Winding Fault Diagnosis Using Vibration Image and Deep Learning. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2021, 36, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, S.; Sun, S.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Ouyang, J.; Ni, X. Partial Discharge Pattern Recognition of Transformers Based on MobileNets Convolutional Neural Network. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Yu, L.; Chen, B.; Chen, G.; Chen, Y. Research on Pattern Recognition Method of Transformer Partial Discharge Based on Artificial Neural Network. Security and Communication Networks 2022, 2022, 5154649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.D.; Tuyet-Doan, V.N.; Cho, Y.S.; Sun, J.H.; Kim, Y.H. Convolutional-Neural-Network-Based Partial Discharge Diagnosis for Power Transformer Using UHF Sensor. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 207377–207388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, Y.; Xing, Z.; Wang, L.; Shao, K.; Lei, L.; Li, Z. Vibration Signal-Based Fusion Residual Attention Model for Power Transformer Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Sensors Journal 2024, 24, 17231–17242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; He, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Du, B.; He, L.; Liu, X. Vibration-Signal-Based Deep Noisy Filtering Model for Online Transformer Diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2023, 19, 11239–11251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, C.; Qi, Z.; Luo, C. LA YOLOv8s: A lightweight-attention YOLOv8s for oil leakage detection in power transformers. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2024, 92, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

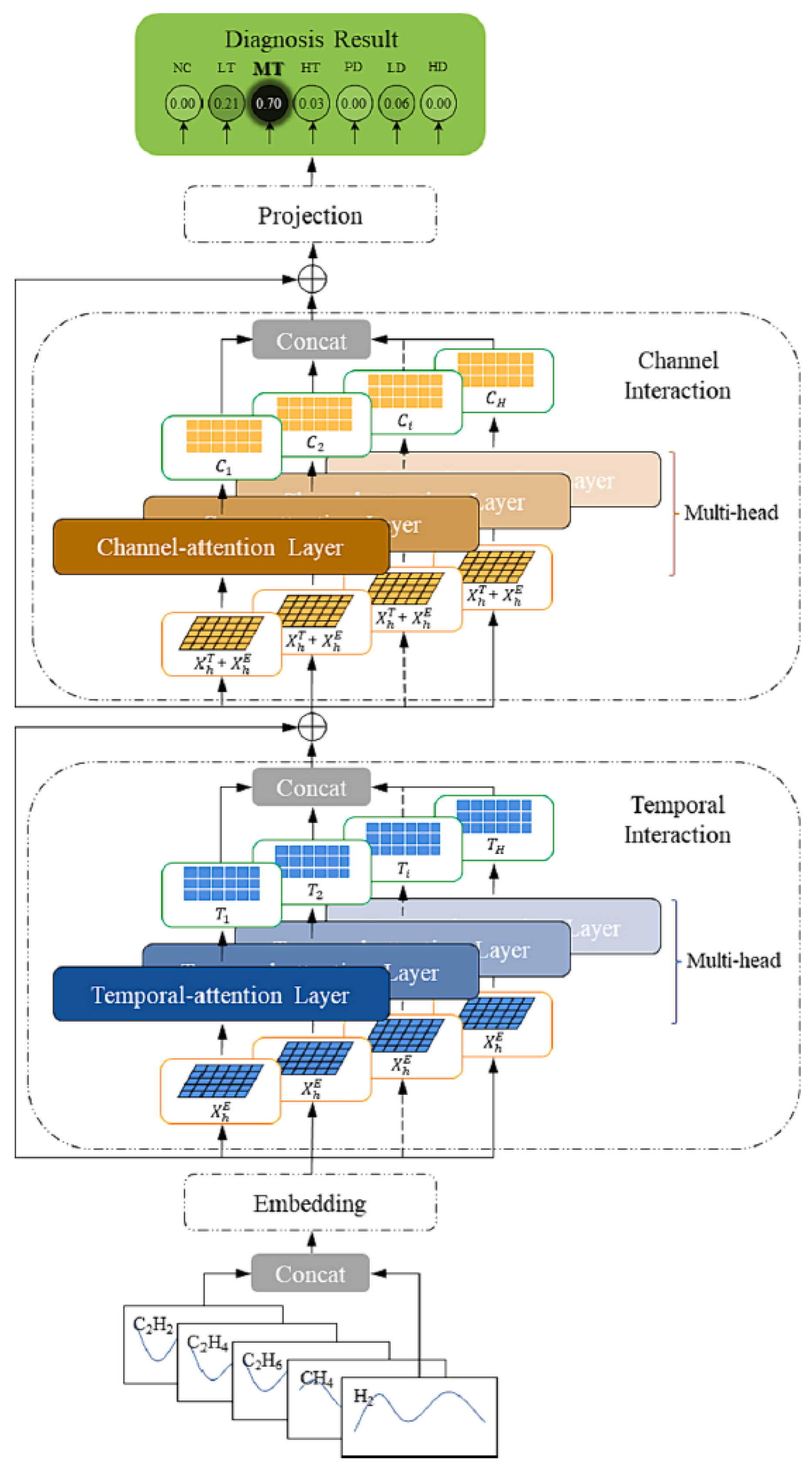

- Xing, Z.; He, Y. Multi-modal information analysis for fault diagnosis with time-series data from power transformer. International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems 2023, 144, 108567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Kim, D.; Chan, K.Y.; Abu-Siada, A. Deep Machine Learning-Based Asset Management Approach for Oil- Immersed Power Transformers Using Dissolved Gas Analysis. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 27794–27809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; He, Y. Multimodal Mutual Neural Network for Health Assessment of Power Transformer. IEEE Systems Journal 2023, 17, 2664–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; He, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Du, B. Health evaluation of power transformer using deep learning neural network. Electric Power Systems Research 2023, 215, 109016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Cao, Y.; He, G.; Feng, L.; Tan, Z.; Mo, W.; Fan, J. Dissolved gas in transformer oil forecasting for transformer fault evaluation based on HATT-RLSTM. Electric Power Systems Research 2023, 221, 109431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Chen, W.; Fang, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, K. GRU-AGCN model for the content prediction of gases in power transformer oil. Frontiers in Energy Research 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, X. A Deep Learning Approach to the Transformer Life Prediction Considering Diverse Aging Factors. Frontiers in Energy Research 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Miao, X.; Chen, J.; Xiao, S.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, H. Forecasting thermal parameters for ultra-high voltage transformers using long- and short-term time-series network with conditional mutual information. IET Electric Power Applications 2022, 16, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, Z. A Transformer Vibration Amplitude Prediction Method Via Fusion Of Multi-Signals. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 5th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2); 2021; pp. 3268–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Paramane, A.; Chatterjee, S.; Rao, U.M. Sensing Incipient Faults in Power Transformers Using Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory Network. IEEE Sensors Letters 2023, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Littler, T.; Liu, X. Dynamic Incipient Fault Forecasting for Power Transformers Using an LSTM Model. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2023, 30, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Hu, H.; Shang, Y. A New Method for Transformer Fault Prediction Based on Multifeature Enhancement and Refined Long Short-Term Memory. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2021, 70, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Yi, S.; Fan, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, G.; Cao, Y.; Feng, L.; Tan, Z.; Mo, W. Power transformer fault diagnosis based on a self-strengthening offline pre-training model. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 126, 107142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, J.F.; Castro, A.R.G. Diagnosing Faults in Power Transformers With Variational Autoencoder, Genetic Programming, and Neural Network. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 30529–30545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jo, S.H.; Kim, W.; Park, J.; Jeong, J.; Han, Y.; Kim, D.; Youn, B.D. A Semi-Supervised Autoencoder With an Auxiliary Task (SAAT) for Power Transformer Fault Diagnosis Using Dissolved Gas Analysis. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 178295–178310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Xie, J.; Yang, B.; Zhao, B. Fault Diagnosis of Power Transformer Based on Stacked Sparse Auto-Encoders and Broad Learning System. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Robotics and Automation Engineering (ICRAE); 2021; pp. 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, B.; Shin, J.; Kim, T.; Youn, B.D. Missing data imputation using an iterative denoising autoencoder (IDAE) for dissolved gas analysis. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 212, 108642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Xi, R.; Che, L.; He, H. Health condition assessment of transformers based on cross message passing graph neural networks. Frontiers in Energy Research 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

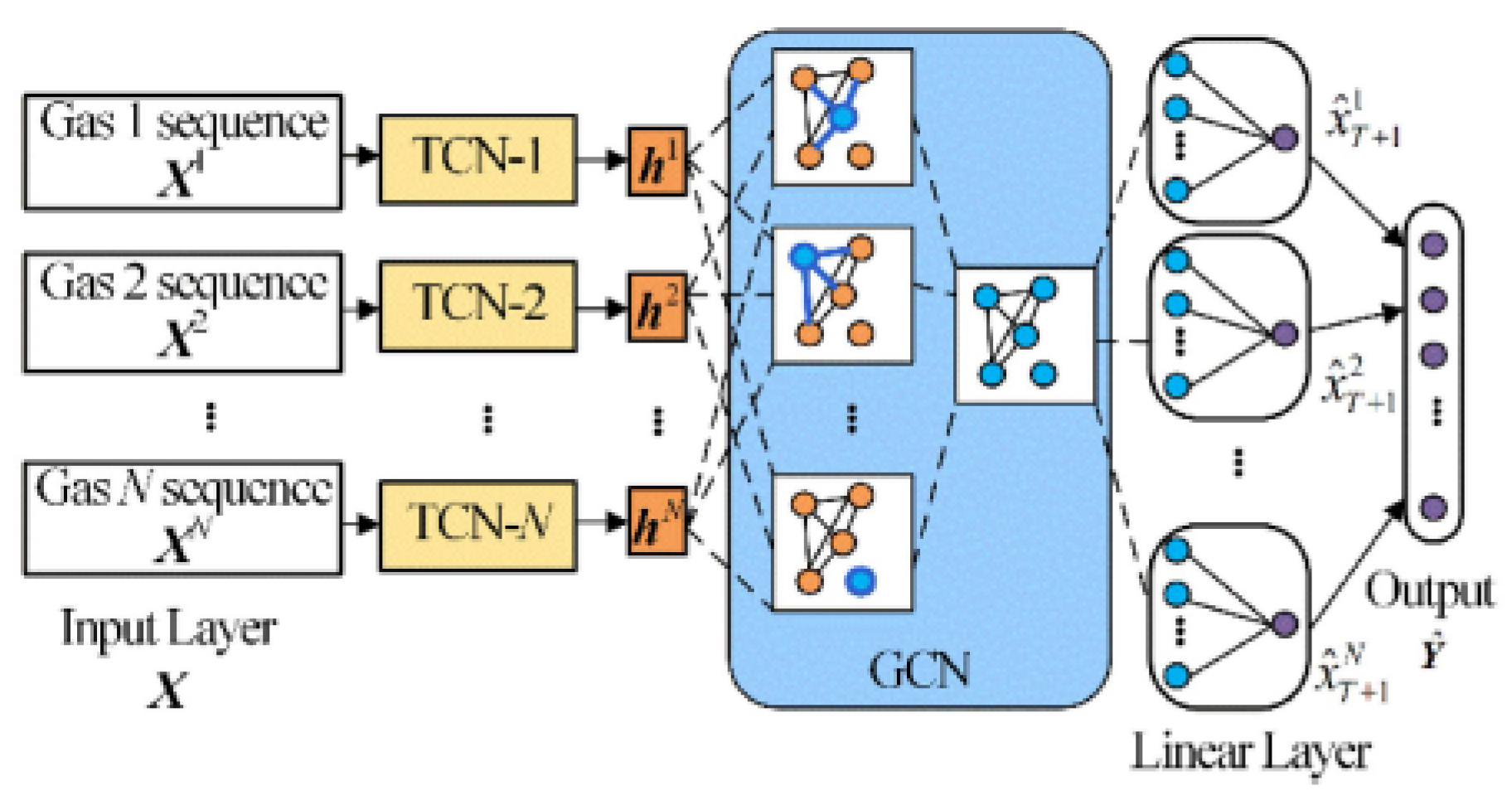

- Luo, D.; Fang, J.; He, H.; Lee, W.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zai, H.; Chen, W.; Zhang, K. Prediction for Dissolved Gas in Power Transformer Oil Based On TCN and GCN. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2022, 58, 7818–7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Song, H.; Sheng, G.; Jiang, X. Dissolved gas analysis of insulating oil for power transformer fault diagnosis with deep belief network. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2017, 24, 2828–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Li, Z.; Quan, H.; Peng, Q.; Wang, S.; Hong, Z.; Dai, W.; Zhou, T.; Yin, J. Transformer fault classification for diagnosis based on DGA and deep belief network. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zang, Y.; Li, J.; Song, Z.; Zhao, K. Transformer fault diagnosis method based on two-dimensional cloud model under the condition of defective data. Electrical Engineering 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragone, F.; Morozovska, K.; Hilber, P.; Laneryd, T.; Luvisotto, M. Physics-informed neural networks for modelling power transformer’s dynamic thermal behaviour. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 211, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Herrera, F.; Hwang, K. Cognitive Computing: Architecture, Technologies and Intelligent Applications. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 19774–19783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M., S.; Murugappan, A.; T., M. Cognitive computing technological trends and future research directions in healthcare — A systematic literature review. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2023, 138, 102513. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zheng, P.; Li, X.; Gao, R.; Wang, L. Toward cognitive predictive maintenance: A survey of graph-based approaches. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2022, 64, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cui, P.; Zhu, W. Deep Learning on Graphs: A Survey. CoRR 2018, abs/1812.04202, [1812.04202]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesgaran, M.; Hamza, A.B. A graph encoder–decoder network for unsupervised anomaly detection. Neural Computing and Applications 2023, 35, 23521–23535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lyu, F.; Hu, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, X. Encoder-Decoder Architecture for Supervised Dynamic Graph Learning: A Survey. 2022, arXiv:cs.LG/2203.10480]. [Google Scholar]

- Bacciu, D.; Errica, F.; Micheli, A.; Podda, M. A gentle introduction to deep learning for graphs. Neural Networks 2020, 129, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khemani, B.; Patil, S.; Kotecha, K.; Tanwar, S. A review of graph neural networks: concepts, architectures, techniques, challenges, datasets, applications, and future directions. Journal of Big Data 2024, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, J.; Alippi, C.; Ding, S.X.; Shardt, Y.; Peng, T.; Yang, C. Graph neural network-based fault diagnosis: a review. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhou, Z.; Li, S.; Sun, C.; Yan, R.; Chen, X. The emerging graph neural networks for intelligent fault diagnostics and prognostics: A guideline and a benchmark study. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2022, 168, 108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Cui, G.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Sun, M. Graph neural networks: A review of methods and applications. AI Open 2020, 1, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wei, Z.; Huang, Z.; Ding, B.; Li, Y. Simple and Deep Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning; III, H.D.; Singh, A., Eds. PMLR, 13–18 Jul 2020, Vol. 119, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp.

- Ruiz, L.; Gama, F.; Ribeiro, A. Gated Graph Recurrent Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2020, 68, 6303–6318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennard, V.; Nikolentzos, G.; Vazirgiannis, M. Benito, R.M., Cherifi, C., Cherifi, H., Moro, E., Rocha, L.M., Sales-Pardo, M., Eds.; Graph Auto-Encoders for Learning Edge Representations. In Proceedings of the Complex Networks & Their Applications IX; Cham, 2021; pp. 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, J.; Ruder, S.; Vulić, I.; Ponti, E.M. Modular Deep Learning. 2023, arXiv:cs.LG/2302.11529]. [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman, N.; Weiss, M.; Träuble, F.; Locatello, F.; Lacoste, A.; Bengio, Y.; Pal, C.; Li, L.E.; Schölkopf, B. A General Purpose Neural Architecture for Geospatial Systems. 2022, arXiv:cs.LG/2211.02348]. [Google Scholar]

- Jaegle, A.; Borgeaud, S.; Alayrac, J.; Doersch, C.; Ionescu, C.; Ding, D.; Koppula, S.; Zoran, D.; Brock, A.; Shelhamer, E.; et al. Perceiver IO: A General Architecture for Structured Inputs & Outputs. CoRR 2021, abs/2107.14795, [2107.14795]. [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman, N.; Weiss, M.; Locatello, F.; Pal, C.; Bengio, Y.; Schölkopf, B.; Li, L.E.; Ballas, N. Neural Attentive Circuits. 2022, arXiv:cs.LG/2210.08031]. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Ding, P.; Jia, M. Self-supervised pretraining via contrast learning for intelligent incipient fault detection of bearings. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 2022, 218, 108126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, R.; Chen, J.; Xia, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, W. Deep Self-Supervised Domain Adaptation Network for Fault Diagnosis of Rotating Machine With Unlabeled Data. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, J.; Deng, C.; Wei, M.; Xu, X. Self-supervised learning for intelligent fault diagnosis of rotating machinery with limited labeled data. Applied Acoustics 2022, 191, 108663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Liang, X. Self-Supervised Deep Domain-Adversarial Regression Adaptation for Online Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Rolling Bearing Under Unknown Working Condition. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2023, 19, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Lü, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, K.; Zhang, B.; Snoussi, H. A Multihead Attention Self-Supervised Representation Model for Industrial Sensors Anomaly Detection. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2024, 20, 2190–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, Z. Self-Supervised Deep Tensor Domain-Adversarial Regression Adaptation for Online Remaining Useful Life Prediction Across Machines. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, M. Self-Supervised Defect Representation Learning for Label-Limited Rail Surface Defect Detection. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 29235–29246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Meng, Z.; Sun, D.; Liu, J.; Fan, F. 2MNet: Multi-sensor and multi-scale model toward accurate fault diagnosis of rolling bearing. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 2021, 216, 108017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Su, J.; Feng, X. A Residual Multihead Self-Attention Network Using Multimodal Shallow Feature Fusion for Motor Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Sensors Journal 2023, 23, 29131–29142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Huang, H. Knowledge distillation-optimized two-stage anomaly detection for liquid rocket engine with missing multimodal data. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 2024, 241, 109676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Jia, S.; Noman, K. Physics-inspired multimodal machine learning for adaptive correlation fusion based rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Information Fusion 2024, 108, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tao, J.; Sun, G.; Wu, T.; Yu, L.; Zhao, X. A novel digital twin approach based on deep multimodal information fusion for aero-engine fault diagnosis. Energy 2023, 270, 126894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounta, C.A.K.A.; Kamsu-Foguem, B.; Noureddine, F.; Tangara, F. Multimodal deep learning for predicting the choice of cut parameters in the milling process. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2022, 16, 200112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Bu, L.; Han, S. AI-enabled and multimodal data driven smart health monitoring of wind power systems: A case study. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2023, 56, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhong, X.; Shao, H.; Han, T.; Shen, C. Multi-sensor gearbox fault diagnosis by using feature-fusion covariance matrix and multi-Riemannian kernel ridge regression. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 2021, 216, 108018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Qin, G.; Huang, S.; Song, D.; Shao, H.; Wu, G. Motor fault diagnosis using attention mechanism and improved adaboost driven by multi-sensor information. Measurement 2021, 170, 108718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Bao, S.; Shao, H.; Shi, P. A multi-sensor fused incremental broad learning with D-S theory for online fault diagnosis of rotating machinery. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2024, 60, 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Yan, X.; Jiang, D.; Xiang, L.; Chen, N. MIFDELN: A multi-sensor information fusion deep ensemble learning network for diagnosing bearing faults in noisy scenarios. Knowledge-Based Systems 2024, 284, 111294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Qian, W.; Wang, J. A novel multi-sensor hybrid fusion framework. Measurement Science and Technology 2024, 35, 086105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, W. Multi-head spatio-temporal attention based parallel GRU architecture: a novel multi-sensor fusion method for mechanical fault diagnosis. Measurement Science and Technology 2023, 35, 015111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Shen, J.; Song, D.; Xu, F. A vibro-acoustic signals hybrid fusion model for blade crack detection. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2023, 204, 110815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Shen, J.; Song, D.; Xu, F. Multi-sensor and multi-level information fusion model for compressor blade crack detection. Measurement 2023, 222, 113622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Mao, Z.; Liu, F.; Kong, X.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Z. Multi-sensor signals multi-scale fusion method for fault detection of high-speed and high-power diesel engine under variable operating conditions. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 126, 106912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Liu, C.; Zheng, J.; Pan, H. Multi-sensor information fusion and coordinate attention-based fault diagnosis method and its interpretability research. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 124, 106614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, J.; Ren, Z.; Ni, Q.; Wen, B. Multi-sensor open-set cross-domain intelligent diagnostics for rotating machinery under variable operating conditions. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2023, 191, 110172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; He, Q.; Zhen, D.; Gu, F.; Ball, A.D. Multi-sensor data fusion for rotating machinery fault detection using improved cyclic spectral covariance matrix and motor current signal analysis. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 2023, 230, 108969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Xia, M.; Williams, D.; de Silva, C.W. A New Multisensor Partial Domain Adaptation Method for Machinery Fault Diagnosis Under Different Working Conditions. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xie, F.; Zhang, Q.; Lyu, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, S. A multisensory time-frequency features fusion method for rotating machinery fault diagnosis under nonstationary case. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Zhu, J.; Cao, S.; Li, P.; Xu, C. Bearing Fault Diagnosis Under Multisensor Fusion Based on Modal Analysis and Graph Attention Network. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Li, T.; Fang, B.; Yan, K.; Hong, J.; Li, X. Bearing Fault Diagnosis Based on Multisensor Information Coupling and Attentional Feature Fusion. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, K.; Ma, H.; Yu, K.; Ren, Z.; Liu, Z. MMFNet: Multisensor Data and Multiscale Feature Fusion Model for Intelligent Cross-Domain Machinery Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; He, Q.; Zhen, D.; Gu, F.; Ball, A.D. Multiscale cyclic frequency demodulation-based feature fusion framework for multi-sensor driven gearbox intelligent fault detection. Knowledge-Based Systems 2024, 283, 111203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Wang, H.; Sun, M. ChatGPT-like large-scale foundation models for prognostics and health management: A survey and roadmaps. Reliability Engineering and System Safety 2024, 243, 109850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.B.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M.S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; et al. On the Opportunities and Risks of Foundation Models. CoRR 2021, abs/2108.07258, [2108.07258]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Li, Q.; Li, C.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhang, K.; Ji, C.; Yan, Q.; He, L.; et al. A Comprehensive Survey on Pretrained Foundation Models: A History from BERT to ChatGPT. 2023, arXiv:cs.AI/2302.09419]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. Modularity in deep learning. Theses, Université Paris-Saclay, 2023.

- Goyal, A.; Bengio, Y. Inductive Biases for Deep Learning of Higher-Level Cognition. CoRR 2020, abs/2011.15091, [2011.15091]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitty-Venkata, K.T.; Emani, M.; Vishwanath, V.; Somani, A.K. Neural Architecture Search for Transformers: A Survey. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 108374–108412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, A.; Xu, C.; Xu, Y.; et al. A Survey on Vision Transformer. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2023, 45, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, N.; Lu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Yang, G.; Huo, Y.; Wen, J.; Lu, H.; Song, R.; Gao, X.; Xiang, T.; et al. Towards artificial general intelligence via a multimodal foundation model. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, V.; Satayeva, M.; Frej, J.; Bossy, T.; Vogels, T.; Jaggi, M.; Käser, T.; Hartley, M.A. Oh, A., Neumann, T., Globerson, A., Saenko, K., Hardt, M., Levine, S., Eds.; MultiMoDN—Multimodal, Multi-Task, Interpretable Modular Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc., 2023; Vol. 36, pp. 28115–28138. [Google Scholar]

- Siddharth, N.; Paige, B.; van de Meent, J.W.; Desmaison, A.; Goodman, N.D.; Kohli, P.; Wood, F.; Torr, P.H.S. Learning Disentangled Representations with Semi-Supervised Deep Generative Models. 2017, arXiv:stat.ML/1706.00400]. [Google Scholar]

- Hristov, Y.; Angelov, D.; Burke, M.; Lascarides, A.; Ramamoorthy, S. Disentangled Relational Representations for Explaining and Learning from Demonstration. CoRR 2019, abs/1907.13627, [1907.13627]. [Google Scholar]

- Berrevoets, J.; Kacprzyk, K.; Qian, Z.; van der Schaar, M. Causal Deep Learning. 2023, arXiv:cs.LG/2303.02186]. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, J.; Ruder, S.; Vulić, I.; Ponti, E.M. Modular Deep Learning. 2023, arXiv:cs.LG/2302.11529]. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D.; Liu, J.; Dusenberry, M.W.; Phan, D.; Collier, M.; Ren, J.; Han, K.; Wang, Z.; Mariet, Z.; Hu, H.; et al. Plex: Towards Reliability using Pretrained Large Model Extensions. 2022, arXiv:cs.LG/2207.07411]. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, S.; Adeel, M.; Iqbal, M.; Namoun, A.; Tufail, A.; Kim, K.H. Deep learning methods utilization in electric power systems. Energy Reports 2023, 10, 2138–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymann, F.; Quest, H.; Lopez Garcia, T.; Ballif, C.; Galus, M. Reviewing 40 years of artificial intelligence applied to power systems – A taxonomic perspective. Energy and AI 2024, 15, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, L.; Brcic, M.; Cabitza, F.; Choi, J.; Confalonieri, R.; Ser, J.D.; Guidotti, R.; Hayashi, Y.; Herrera, F.; Holzinger, A.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) 2.0: A manifesto of open challenges and interdisciplinary research directions. Information Fusion 2024, 106, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machlev, R.; Heistrene, L.; Perl, M.; Levy, K.Y.; Belikov, J.; Mannor, S.; Levron, Y. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques for energy and power systems: Review, challenges and opportunities. Energy and AI 2022, 9, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V.; Sant, A.; Sharma, P.; Nayak, M.; Khatri, H. An explainable artificial intelligence based approach for the prediction of key performance indicators for 1 megawatt solar plant under local steppe climate conditions. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2024, 131, 107809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titz, M.; Pütz, S.; Witthaut, D. Identifying drivers and mitigators for congestion and redispatch in the German electric power system with explainable AI. Applied Energy 2024, 356, 122351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classic ML | Task | Data | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLP | FDD | DGA | [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] |

| FDD | DGA+ | [33,34] | |

| FDD | [35,36] | ||

| HI | DGA | [37,38] | |

| HI | DGA+ | [39,40,41] | |

| Pred. | Other | [42] | |

| ANFIS | FDD | DGA | [43,44,45,46] |

| FDD | DGA+ | [47,48] | |

| FDD | Other | [49,50,51] | |

| Clustering | |||

| x SVM | FDD | DGA | [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69] |

| FDD | Other | [2,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] | |

| HI | DGA+ | [78,79,80] | |

| Pred. | [81] | ||

| x Fc-m | FDD | DGA | [82,83,84] |

| HI | DGA | [85] | |

| Pred. | Other | [86] | |

| x KNN | FDD | DGA | [87,88,89,90,91] |

| FDD | Other | [92,93] | |

| FIS | FDD | DGA | [51,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105] |

| FDD | Other | [106,107,108,109,110,111,112] | |

| HI | DGA+ | [48,113,114,115,116,117,118,119] | |

| HI | Other | [120,121] | |

| BI | FDD | DGA | [122,123] |

| HI | DGA+ | [124,125] | |

| DT | FDD | DGA | [126,127] |

| FDD | Other | [128] | |

| WN | FDD | DGA | [129,130,131] |

| FDD | Other | [132] | |

| HI | DGA+ | [133] | |

| GP | FDD | DGA | [134,135,136] |

| HI | DGA+ | [137] | |

| Pred. | Other | [138] | |

| EL | FDD | DGA | [139,140,141] |

| RF | FDD | DGA | [142,143] |

| HMM | FDD | DGA | [144] |

| ELM | FDD | DGA | [145,146,147,148] |

| Mix. ML | FDD | DGA | [149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157] |

| HI | DGA+ | [16,17,18,19,158,159] | |

| Pred. | Other | [20,21,160,161,162] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).