Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

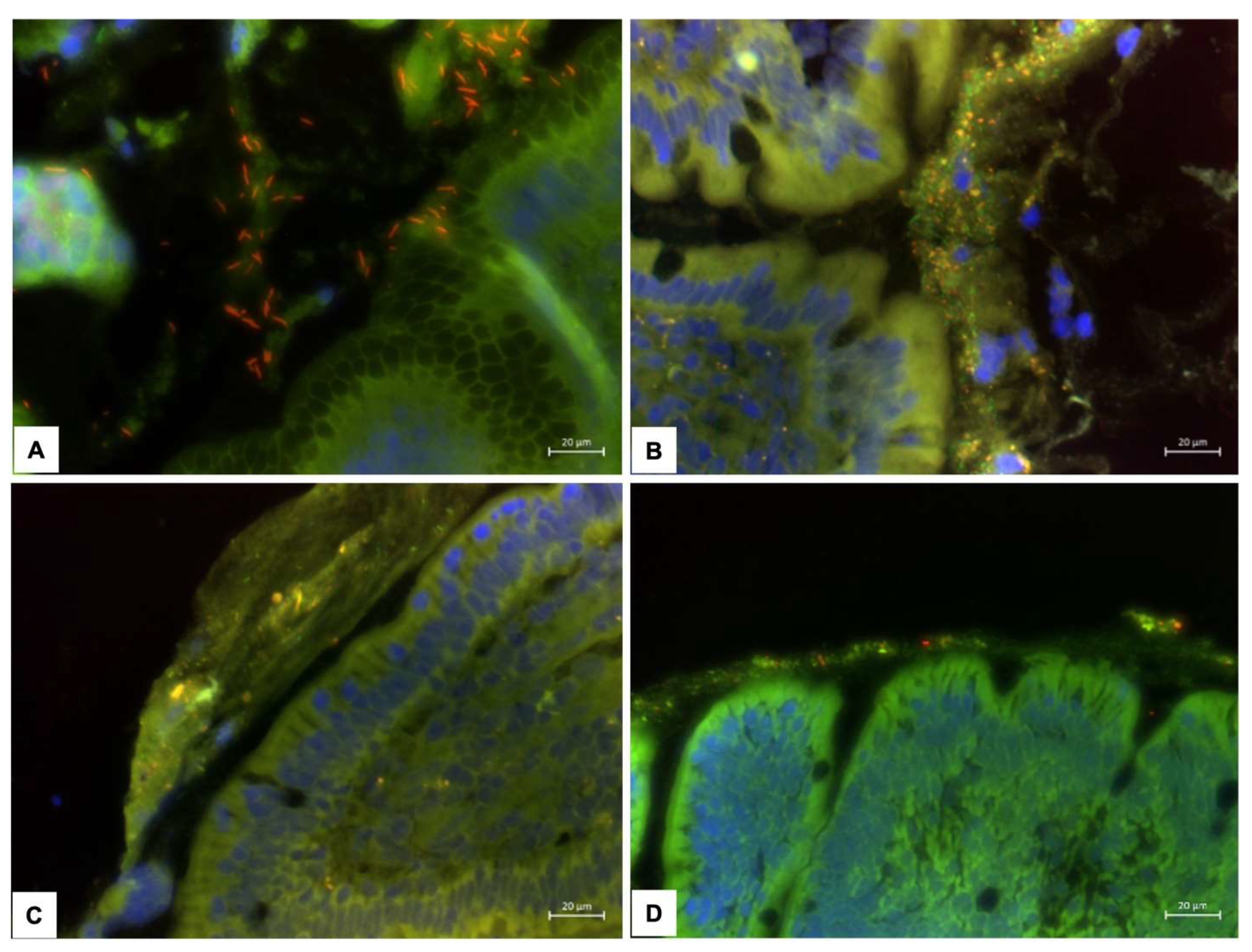

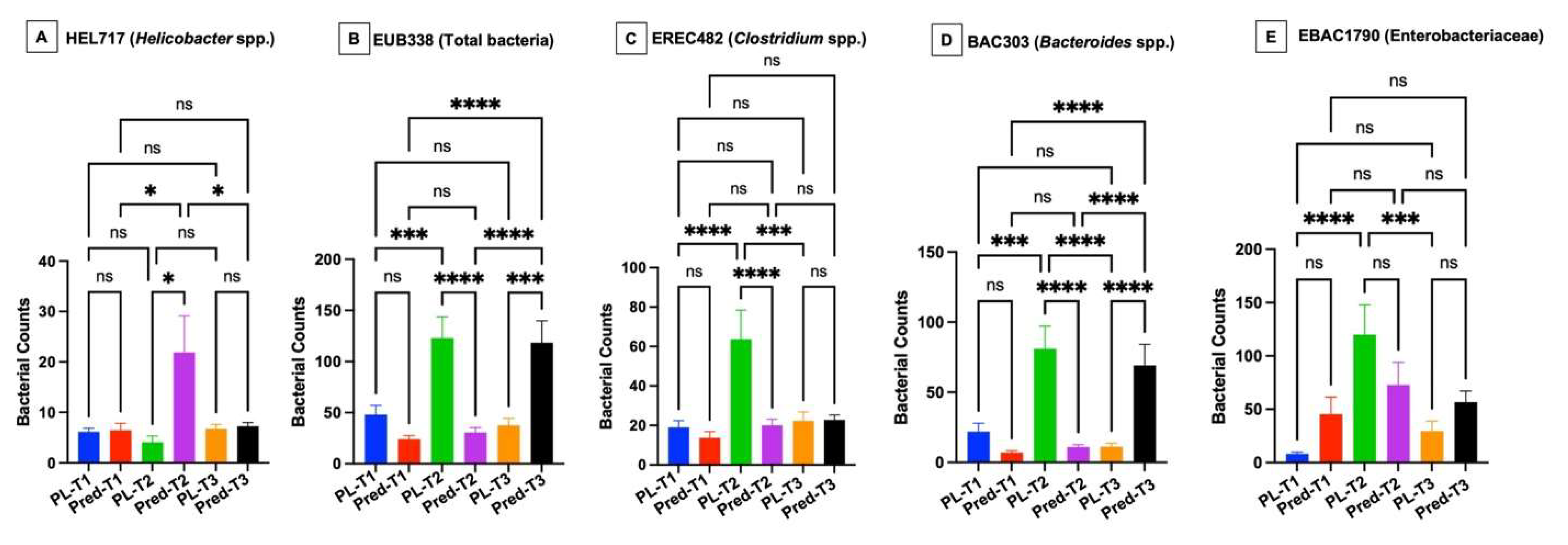

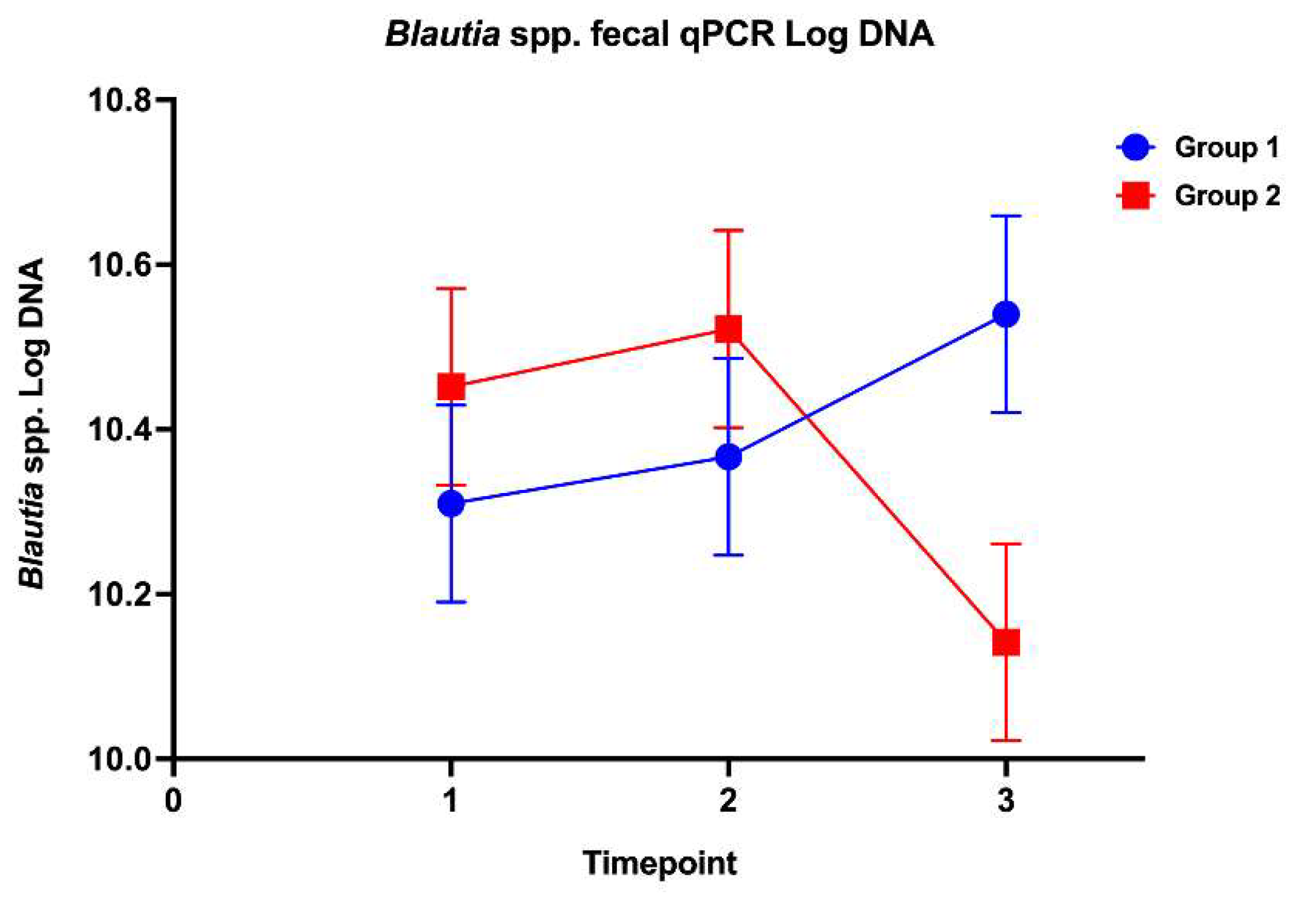

The effects of high-dose glucocorticoids on the gastrointestinal microbiota of healthy dogs are unknown. This study’s aim was to investigate the effects of immunosuppressive doses of prednisone on the fecal microbiota and the gastric and duodenal mucosal microbiota in healthy dogs. Twelve healthy adult dogs were enrolled into a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Dogs were evaluated on days 0, 14, and 28 following treatments with either prednisone (2 mg/kg/d) or placebo. Outcome measures included: 1) composition and abundance of the fecal microbiota (via high throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene and qPCR-based dysbiosis index [DI]) and 2) spatial distribution of the gastric and duodenal mucosal microbiota using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). No significant difference in alpha and beta diversity or amplicon sequence variants of the fecal microbiota was observed between treatment groups. Blautia spp. concentrations via qPCR were significantly decreased between prednisone group timepoints 2 and 3. Compared to placebo group dogs, prednisone group dogs showed significantly increased gastric mucosal helicobacters and increased mucosal associated total bacteria and Bacteroides in duodenal biopsies over the treatment period. Results indicate that immunosuppressive dosages of prednisone alter the mucosal microbiota of healthy dogs in a time-dependent manner which may disrupt mucosal homeostasis.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Mucosal Microbiome Analysis

2.4. Fecal Microbiome Analysis

2.5. Statistical and Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Animals

3.2. Mucosal Microbiota

3.3. Fecal Microbiota

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Viviano, K. R. Glucocorticoids, Cyclosporine, Azathioprine, Chlorambucil, and Mycophenolate in Dogs and Cats: Clinical Uses, Pharmacology, and Side Effects. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice 2022, 52(3), 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkholly, D. A.; Brodbelt, D. C.; Church, D. B.; Pelligand, L.; Mwacalimba, K.; Wright, A. K.; O’Neill, D. G. Side Effects to Systemic Glucocorticoid Therapy in Dogs Under Primary Veterinary Care in the UK. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filaretova, L.; Podvigina, T.; Bagaeva, T.; Morozova, O. From gastroprotective to ulcerogenic effects of glucocorticoids: role of long-term glucocorticoid action. Curr Pharm Des 2014, 20(7), 1045–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrer, C. R.; Hill, R. C.; Fischer, A.; Fox, L. E.; Schaer, M.; Ginn, P. E.; Casanova, J. M.; Burrows, C. F. Gastric hemorrhage in dogs given high doses of methylprednisolone sodium succinate. American journal of veterinary research 1999, 60(8), 977–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukamoto, A.; Ohno, K.; Maeda, S.; Nakashima, K.; Fukushima, K.; Fujino, Y.; Hori, M.; Tsujimoto, H. Effect of mosapride on prednisolone-induced gastric mucosal injury and gastric-emptying disorder in dog. J Vet Med Sci 2012, 74(9), 1103–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rak, M. B.; Moyers, T. D.; Price, J. M.; Whittemore, J. C. Clinicopathologic and gastrointestinal effects of administration of prednisone, prednisone with omeprazole, or prednisone with probiotics to dogs: A double-blind randomized trial. J Vet Intern Med 2023, 37(2), 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Bhattacharjee, M.; Banerjee, R. K. Hydroxyl radical is the major causative factor in stress-induced gastric ulceration. Free Radic Biol Med 1997, 23(1), 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tena-Garitaonaindia, M.; Arredondo-Amador, M.; Mascaraque, C.; Asensio, M.; Marin, J. J. G.; Martínez-Augustin, O.; Sánchez de Medina, F. Modulation of intestinal barrier function by glucocorticoids: Lessons from preclinical models. Pharmacol Res 2022, 177, 106056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schepper, J. D.; Collins, F.; Rios-Arce, N. D.; Kang, H. J.; Schaefer, L.; Gardinier, J. D.; Raghuvanshi, R.; Quinn, R. A.; Britton, R.; Parameswaran, N. Involvement of the gut microbiota and barrier function in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2020, 35(4), 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Yang, L.; Jiang, J.; Ni, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Q.; Lu, X.; Fu, Z. Chronic glucocorticoid treatment induced circadian clock disorder leads to lipid metabolism and gut microbiota alterations in rats. Life Sciences 2018, 192, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Kong, X.; Shao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, C. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota Associated With Promoting Efficacy of Prednisone by Bromofuranone in MRL/lpr Mice. Frontiers in microbiology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E. Y.; Inoue, T.; Leone, V. A.; Dalal, S.; Touw, K.; Wang, Y.; Musch, M. W.; Theriault, B.; Higuchi, K.; Donovan, S. Using corticosteroids to reshape the gut microbiome: implications for inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2015, 21(5), 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, M.; Lu, C.; Han, J.; Tang, S.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Ming, T.; Wang, Z. J.; Su, X., Tuna bone powder alleviates glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis via coregulation of the NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways and modulation of gut microbiota composition and metabolism. Molecular nutrition & food research 2020, 64 (5), 1900861.

- Qi, X.-Z.; Tu, X.; Zha, J.-W.; Huang, A.-G.; Wang, G.-X.; Ling, F., Immunosuppression-induced alterations in fish gut microbiota may increase the susceptibility to pathogens. Fish & Shellfish Immunology 2019, 88, 540-545.

- Tourret, J.; Willing, B. P.; Dion, S.; MacPherson, J.; Denamur, E.; Finlay, B. B. Immunosuppressive treatment alters secretion of ileal antimicrobial peptides and gut microbiota, and favors subsequent colonization by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Transplantation 2017, 101(1), 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Chang, H.; Ma, S.; Guo, J.; She, G.; Zhang, F.; Li, L.; Li, X.; Lu, Y. Tiansi liquid modulates gut microbiota composition and tryptophan–kynurenine metabolism in rats with hydrocortisone-induced depression. Molecules 2018, 23(11), 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, G.; Pengo, G.; Caldin, M.; Palumbo Piccionello, A.; Steiner, J. M.; Cohen, N. D.; Jergens, A. E.; Suchodolski, J. S. Comparison of microbiological, histological, and immunomodulatory parameters in response to treatment with either combination therapy with prednisone and metronidazole or probiotic VSL#3 strains in dogs with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. PloS one 2014, 9(4), e94699. [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi, H.; Maeda, S.; Ohno, K.; Horigome, A.; Odamaki, T.; Tsujimoto, H. Effect of oral administration of metronidazole or prednisolone on fecal microbiota in dogs. PloS one 2014, 9(9), e107909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, J. C.; Mooney, A. P.; Price, J. M.; Thomason, J. Clinical, clinicopathologic, and gastrointestinal changes from aspirin, prednisone, or combination treatment in healthy research dogs: A double-blind randomized trial. J Vet Intern Med 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassmann, E.; White, R.; Atherly, T.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Khoda, S.; Mosher, C.; Ackermann, M.; Jergens, A. Alterations of the Ileal and Colonic Mucosal Microbiota in Canine Chronic Enteropathies. PLoS One 2016, 11(2), e0147321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jergens, A. E.; Pressel, M.; Crandell, J.; Morrison, J. A.; Sorden, S. D.; Haynes, J.; Craven, M.; Baumgart, M.; Simpson, K. W. Fluorescence in situ hybridization confirms clearance of visible Helicobacter spp. associated with gastritis in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med 2009, 23(1), 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, D. K.; Allenspach, K.; Mochel, J. P.; Parker, V.; Rudinsky, A. J.; Winston, J. A.; Bourgois-Mochel, A.; Ackermann, M.; Heilmann, R. M.; Köller, G.; Yuan, L.; Stewart, T.; Morgan, S.; Scheunemann, K. R.; Iennarella-Servantez, C. A.; Gabriel, V.; Zdyrski, C.; Pilla, R.; Suchodolski, J. S.; Jergens, A. E., Synbiotic-IgY Therapy Modulates the Mucosal Microbiome and Inflammatory Indices in Dogs with Chronic Inflammatory Enteropathy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Veterinary sciences 2022, 10 (1).

- Garcia-Mazcorro, J. F.; Suchodolski, J. S.; Jones, K. R.; Clark-Price, S. C.; Dowd, S. E.; Minamoto, Y.; Markel, M.; Steiner, J. M.; Dossin, O. Effect of the proton pump inhibitor omeprazole on the gastrointestinal bacterial microbiota of healthy dogs. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2012, 80(3), 624–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchodolski, J. S.; Camacho, J.; Steiner, J. M. Analysis of bacterial diversity in the canine duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon by comparative 16S rRNA gene analysis. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2008, 66(3), 567–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchodolski, J. S. Companion animals symposium: microbes and gastrointestinal health of dogs and cats. J Anim Sci 2011, 89(5), 1520–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassmann, E.; White, R.; Atherly, T.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Khoda, S.; Mosher, C.; Ackermann, M.; Jergens, A. Alterations of the Ileal and Colonic Mucosal Microbiota in Canine Chronic Enteropathies. PloS one 2016, 11(2), e0147321–e0147321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.; Atherly, T.; Guard, B.; Rossi, G.; Wang, C.; Mosher, C.; Webb, C.; Hill, S.; Ackermann, M.; Sciabarra, P.; Allenspach, K.; Suchodolski, J.; Jergens, A. E. Randomized, controlled trial evaluating the effect of multi-strain probiotic on the mucosal microbiota in canine idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut microbes 2017, 8(5), 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShawaqfeh, M. K.; Wajid, B.; Minamoto, Y.; Markel, M.; Lidbury, J. A.; Steiner, J. M.; Serpedin, E.; Suchodolski, J. S., A dysbiosis index to assess microbial changes in fecal samples of dogs with chronic inflammatory enteropathy. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2017, 93 (11).

- Sung, C.-H.; Pilla, R.; Chen, C.-C.; Ishii, P. E.; Toresson, L.; Allenspach-Jorn, K.; Jergens, A. E.; Summers, S.; Swanson, K. S.; Volk, H.; Schmidt, T.; Stuebing, H.; Rieder, J.; Busch, K.; Werner, M.; Lisjak, A.; Gaschen, F. P.; Belchik, S. E.; Tolbert, M. K.; Lidbury, J. A.; Steiner, J. M.; Suchodolski, J. S. Correlation between Targeted qPCR Assays and Untargeted DNA Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing for Assessing the Fecal Microbiota in Dogs. Animals 2023, 13(16), 2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K. R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Australian journal of ecology 1993, 18(1), 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, J. C.; Mooney, A. P.; Price, J. M.; Thomason, J. Clinical, clinicopathologic, and gastrointestinal changes from administration of clopidogrel, prednisone, or combination in healthy dogs: A double-blind randomized trial. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2019, 33(6), 2618–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeVine, D. N.; Goggs, R.; Kohn, B.; Mackin, A. J.; Kidd, L.; Garden, O. A.; Brooks, M. B.; Eldermire, E. R. B.; Abrams-Ogg, A.; Appleman, E. H.; Archer, T. M.; Bianco, D.; Blois, S. L.; Brainard, B. M.; Callan, M. B.; Fellman, C. L.; Haines, J. M.; Hale, A. S.; Huang, A. A.; Lucy, J. M.; O’Marra, S. K.; Rozanski, E. A.; Thomason, J. M.; Walton, J. E.; Wilson, H. E. ACVIM consensus statement on the treatment of immune thrombocytopenia in dogs and cats. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2024, 38(4), 1982–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jergens, A. E.; Heilmann, R. M. Canine chronic enteropathy-Current state-of-the-art and emerging concepts. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 923013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swann, J. W.; Garden, O. A.; Fellman, C. L.; Glanemann, B.; Goggs, R.; LeVine, D. N.; Mackin, A. J.; Whitley, N. T. ACVIM consensus statement on the treatment of immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2019, 33(3), 1141–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, R. C.; Johnson, L. R. Canine chronic inflammatory rhinitis. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2006, 21(2), 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoades, A. C.; Vernau, W.; Kass, P. H.; Herrera, M. A.; Sykes, J. E. Comparison of the efficacy of prednisone and cyclosporine for treatment of dogs with primary immune-mediated polyarthritis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2016, 248(4), 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saridomichelakis, M. N.; Favrot, C.; Jackson, H. A.; Bensignor, E.; Prost, C.; Mueller, R. S. A proposed medication score for long-term trials of treatment of canine atopic dermatitis sensu lato. The Veterinary record 2021, 188(5), e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, B.; Maggs, D. The use of corticosteroids to treat ocular inflammation. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2004, 34(3), 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilla, R.; Gaschen, F. P.; Barr, J. W.; Olson, E.; Honneffer, J.; Guard, B. C.; Blake, A. B.; Villanueva, D.; Khattab, M. R.; AlShawaqfeh, M. K.; Lidbury, J. A.; Steiner, J. M.; Suchodolski, J. S. Effects of metronidazole on the fecal microbiome and metabolome in healthy dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2020, 34(5), 1853–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stübing, H.; Suchodolski, J. S.; Reisinger, A.; Werner, M.; Hartmann, K.; Unterer, S.; Busch, K., The Effect of Metronidazole versus a Synbiotic on Clinical Course and Core Intestinal Microbiota in Dogs with Acute Diarrhea. Veterinary sciences 2024, 11 (5).

- Hooper, L. V.; Wong, M. H.; Thelin, A.; Hansson, L.; Falk, P. G.; Gordon, J. I., Molecular analysis of commensal host-microbial relationships in the intestine. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2001, 291 (5505), 881-4.

- Hooda, S.; Minamoto, Y.; Suchodolski, J. S.; Swanson, K. S. Current state of knowledge: the canine gastrointestinal microbiome. Anim Health Res Rev 2012, 13(1), 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziese, A. L.; Suchodolski, J. S. Impact of Changes in Gastrointestinal Microbiota in Canine and Feline Digestive Diseases. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice 2021, 51(1), 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honneffer, J. B.; Minamoto, Y.; Suchodolski, J. S. Microbiota alterations in acute and chronic gastrointestinal inflammation of cats and dogs. World journal of gastroenterology 2014, 20(44), 16489–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Mazcorro, J. F.; Lanerie, D. J.; Dowd, S. E.; Paddock, C. G.; Grützner, N.; Steiner, J. M.; Ivanek, R.; Suchodolski, J. S. Effect of a multi-species synbiotic formulation on fecal bacterial microbiota of healthy cats and dogs as evaluated by pyrosequencing. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2011, 78(3), 542–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Mazcorro, J. F.; Dowd, S. E.; Poulsen, J.; Steiner, J. M.; Suchodolski, J. S. Abundance and short-term temporal variability of fecal microbiota in healthy dogs. Microbiologyopen 2012, 1(3), 340–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minamoto, Y.; Minamoto, T.; Isaiah, A.; Sattasathuchana, P.; Buono, A.; Rangachari, V. R.; McNeely, I. H.; Lidbury, J.; Steiner, J. M.; Suchodolski, J. S. Fecal short-chain fatty acid concentrations and dysbiosis in dogs with chronic enteropathy. J Vet Intern Med 2019, 33(4), 1608–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenoulis, P. G.; Palculict, B.; Allenspach, K.; Steiner, J. M.; Van House, A. M.; Suchodolski, J. S. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial communities imbalances in the small intestine of dogs with inflammatory bowel disease. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 2008, 66(3), 579–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchodolski, J. S.; Xenoulis, P. G.; Paddock, C. G.; Steiner, J. M.; Jergens, A. E., Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in duodenal biopsies from dogs with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Vet Microbiol 2010, 142 (3-4), 394-400.

- Suchodolski, J. S.; Dowd, S. E.; Wilke, V.; Steiner, J. M.; Jergens, A. E. 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing reveals bacterial dysbiosis in the duodenum of dogs with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. PloS one 2012, 7(6), e39333–e39333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craven, M.; Mansfield, C. S.; Simpson, K. W. Granulomatous colitis of boxer dogs. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice 2011, 41(2), 433–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, C. S.; James, F. E.; Craven, M.; Davies, D. R.; O’Hara, A. J.; Nicholls, P. K.; Dogan, B.; MacDonough, S. P.; Simpson, K. W. Remission of histiocytic ulcerative colitis in Boxer dogs correlates with eradication of invasive intramucosal Escherichia coli. J Vet Intern Med 2009, 23(5), 964–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giaretta, P. R.; Suchodolski, J. S.; Jergens, A. E.; Steiner, J. M.; Lidbury, J. A.; Cook, A. K.; Hanifeh, M.; Spillmann, T.; Kilpinen, S.; Syrjä, P.; Rech, R. R. Bacterial Biogeography of the Colon in Dogs With Chronic Inflammatory Enteropathy. Veterinary pathology 2020, 57(2), 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atherly, T.; Rossi, G.; White, R.; Seo, Y.-J.; Wang, C.; Ackermann, M.; Breuer, M.; Allenspach, K.; Mochel, J. P.; Jergens, A. E., Glucocorticoid and dietary effects on mucosal microbiota in canine inflammatory bowel disease. PloS one 2019, 14 (12).

- Alverdy, J.; Aoys, E. The effect of glucocorticoid administration on bacterial translocation. Evidence for an acquired mucosal immunodeficient state. Ann Surg 1991, 214(6), 719–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitz, J.; Hecht, G.; Taveras, M.; Aoys, E.; Alverdy, J. The effect of dexamethasone administration on rat intestinal permeability: the role of bacterial adherence. Gastroenterology 1994, 106(1), 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, C. C.; Gillilland, M., 3rd; Sun, X.; El-Zaatari, M.; Huffnagle, G. B.; Young, V. B.; Zhang, J.; Hong, S. C.; Chang, Y. M.; Gumucio, D. L.; Owyang, C.; Kao, J. Y., Stress-induced corticotropin-releasing hormone-mediated NLRP6 inflammasome inhibition and transmissible enteritis in mice. Gastroenterology 2013, 144 (7), 1478-87, 1487.e1-8.

- Clarke, G.; Grenham, S.; Scully, P.; Fitzgerald, P.; Moloney, R. D.; Shanahan, F.; Dinan, T. G.; Cryan, J. F. The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Mol Psychiatry 2013, 18(6), 666–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crumeyrolle-Arias, M.; Jaglin, M.; Bruneau, A.; Vancassel, S.; Cardona, A.; Daugé, V.; Naudon, L.; Rabot, S. Absence of the gut microbiota enhances anxiety-like behavior and neuroendocrine response to acute stress in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 42, 207–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudo, N.; Chida, Y.; Aiba, Y.; Sonoda, J.; Oyama, N.; Yu, X. N.; Kubo, C.; Koga, Y. Postnatal microbial colonization programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system for stress response in mice. J Physiol 2004, 558 (Pt 1) Pt 1, 263–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagnerová, K.; Vodička, M.; Hermanová, P.; Ergang, P.; Šrůtková, D.; Klusoňová, P.; Balounová, K.; Hudcovic, T.; Pácha, J. Interactions Between Gut Microbiota and Acute Restraint Stress in Peripheral Structures of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis and the Intestine of Male Mice. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareau, M. G.; Jury, J.; MacQueen, G.; Sherman, P. M.; Perdue, M. H. Probiotic treatment of rat pups normalises corticosterone release and ameliorates colonic dysfunction induced by maternal separation. Gut 2007, 56(11), 1522–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutgendorff, F.; Akkermans, L. M.; Söderholm, J. D. The role of microbiota and probiotics in stress-induced gastro-intestinal damage. Curr Mol Med 2008, 8(4), 282–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, S. M.; Marchesi, J. R.; Scully, P.; Codling, C.; Ceolho, A. M.; Quigley, E. M.; Cryan, J. F.; Dinan, T. G. Early life stress alters behavior, immunity, and microbiota in rats: implications for irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric illnesses. Biol Psychiatry 2009, 65(3), 263–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Jian, S.; Wen, C.; Guo, D.; Liao, P.; Wen, J.; Kuang, T.; Han, S.; Liu, Q.; Deng, B. Gallnut Tannic Acid Exerts Anti-stress Effects on Stress-Induced Inflammatory Response, Dysbiotic Gut Microbiota, and Alterations of Serum Metabolic Profile in Beagle Dogs. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 847966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilla, R.; Suchodolski, J. S. The Role of the Canine Gut Microbiome and Metabolome in Health and Gastrointestinal Disease. Frontiers in veterinary science 2020, 6, 498–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).