Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

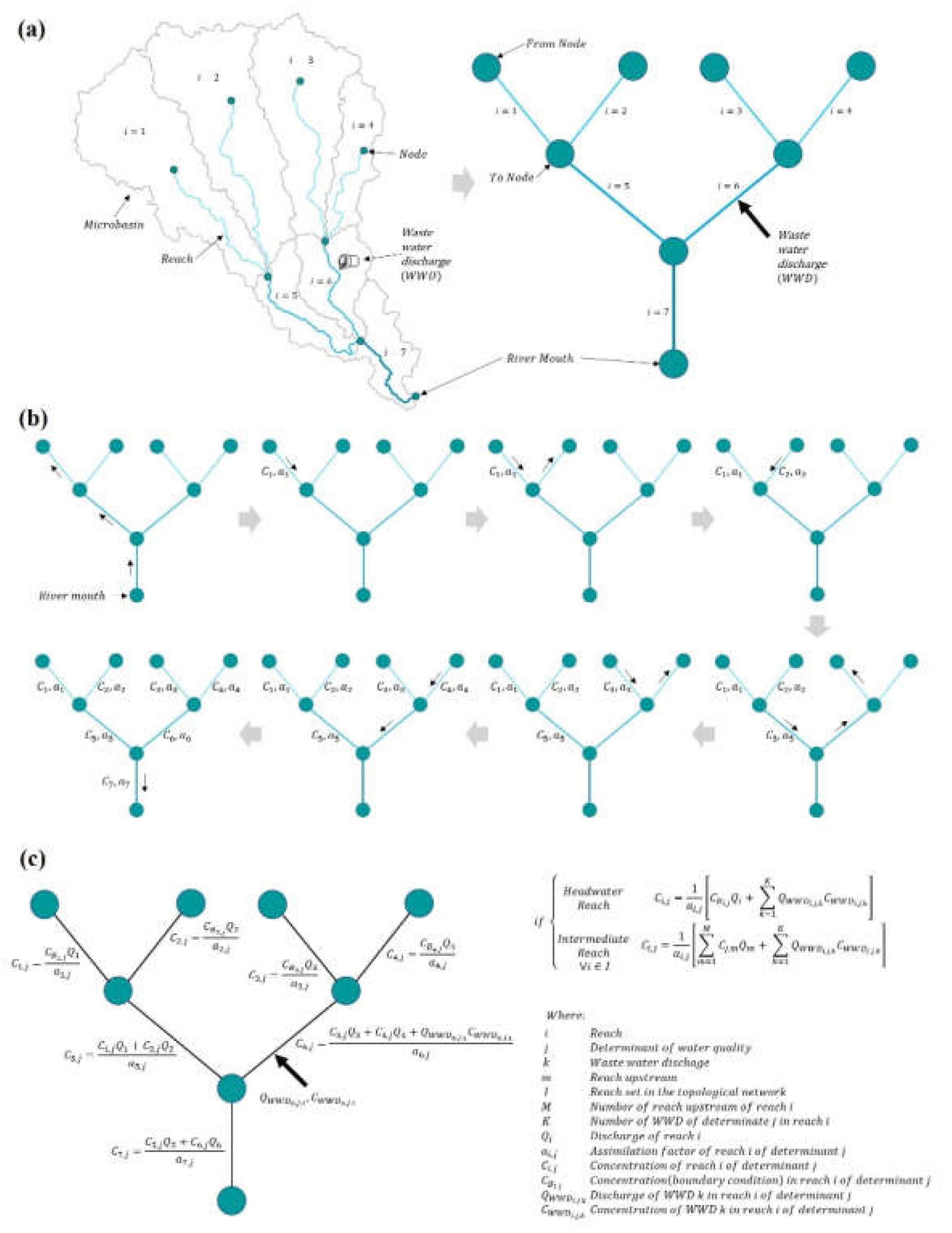

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

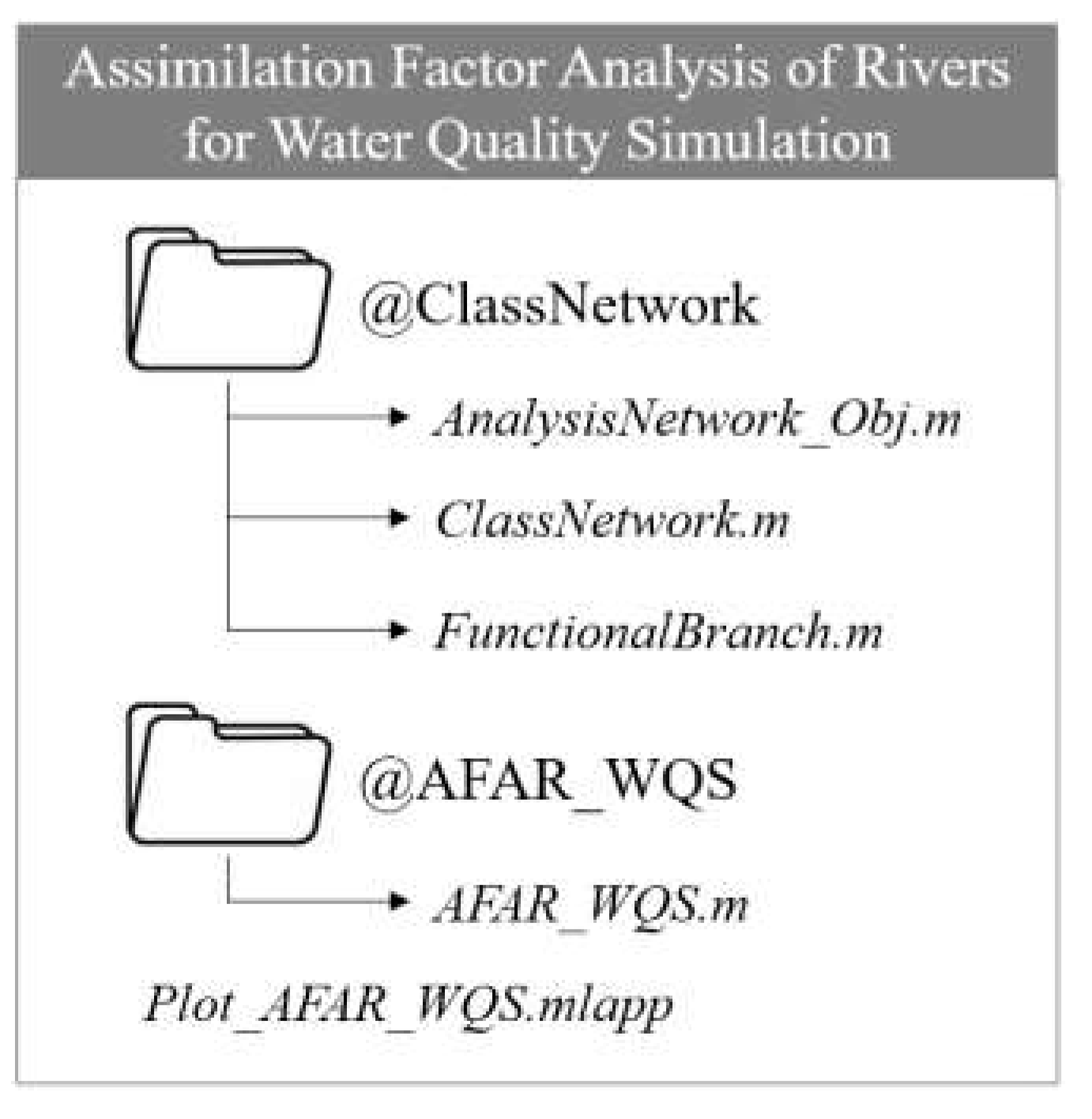

3.1. Toolbox Structure

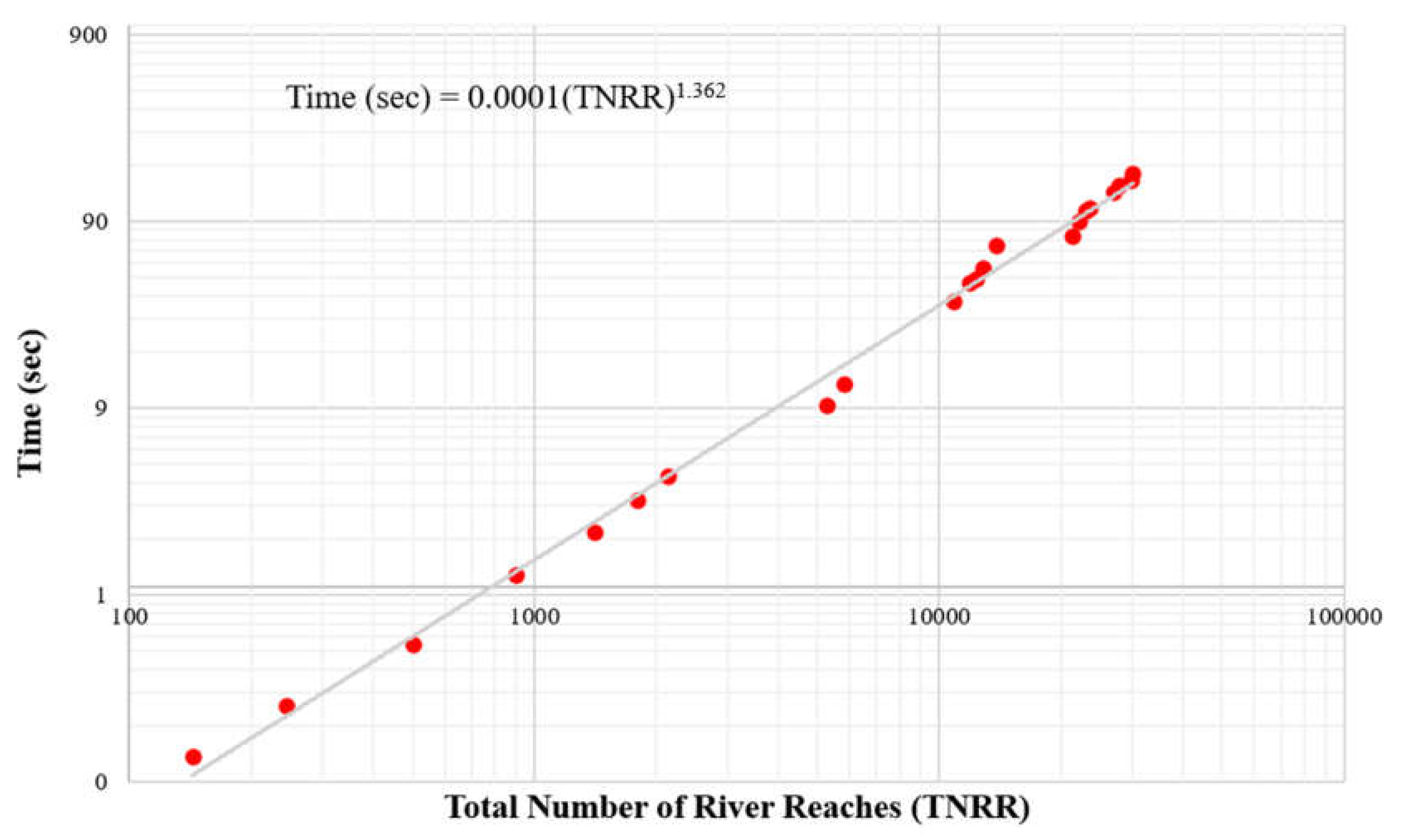

3.2. Computational Performance

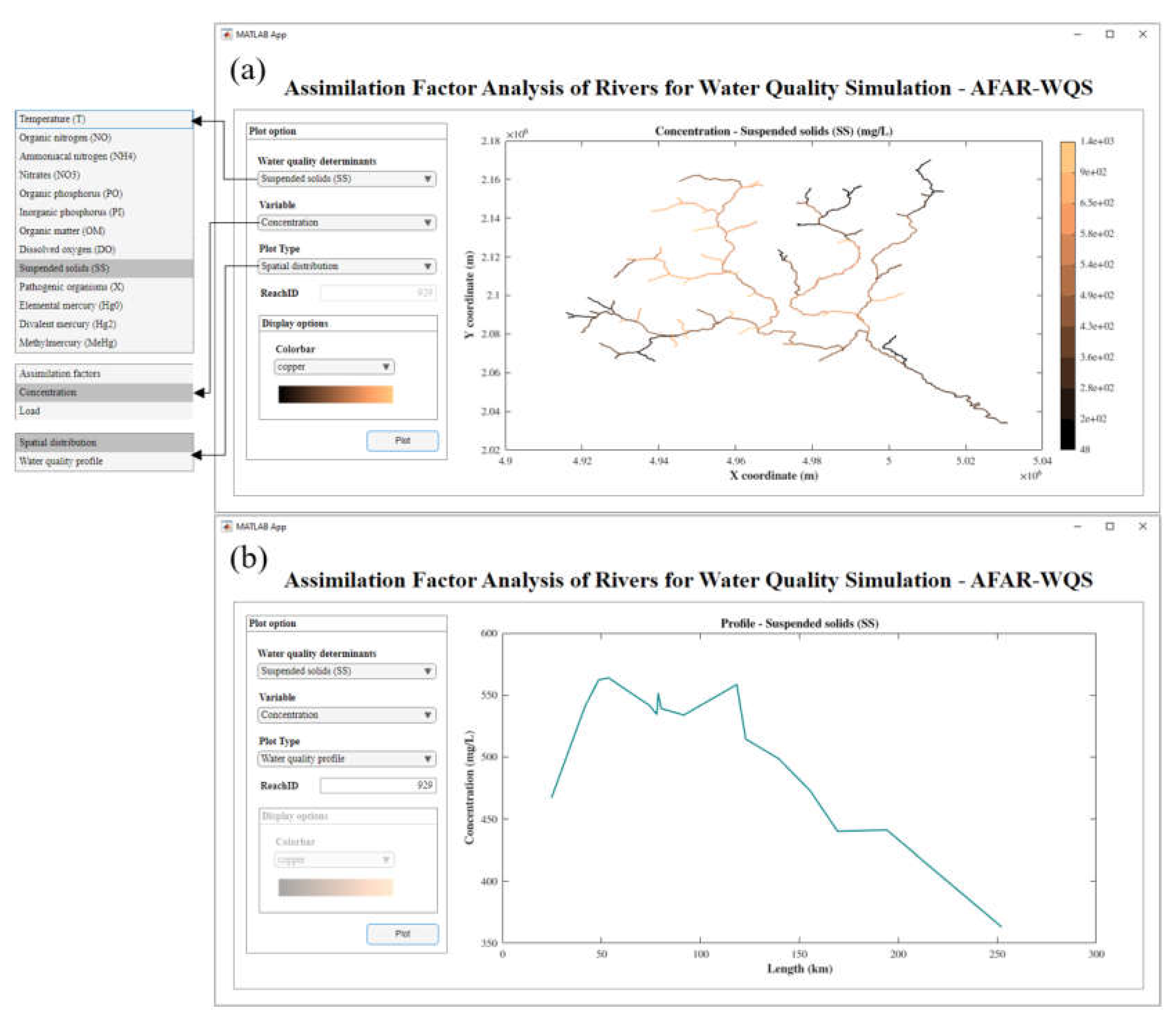

3.3. Outputs and Visualization Options

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Software Availability

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tao, Y.; Tao, Q.; Qiu, J.; Pueppke, S.G.; Gao, G.; Ou, W. Integrating Water Quantity- and Quality-Related Ecosystem Services into Water Scarcity Assessment: A Multi-Scenario Analysis in the Taihu Basin of China. Applied Geography 2023, 160, 103101. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; Park, S.H.; Song, C.M. A Study on an Integrated Water Quantity and Water Quality Evaluation Method for the Implementation of Integrated Water Resource Management Policies in the Republic of Korea. Water (Basel) 2020, 12, 2346. [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, S.; Koehler, J.; Charles, K.J. Including Water Quality Monitoring in Rural Water Services: Why Safe Water Requires Challenging the Quantity versus Quality Dichotomy. NPJ Clean Water 2020, 3, 14. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, M.; Usma, C.; Posada, D.; Ramírez, J.; Rogéliz, C.A.; Nogales, J.; Spiro-Larrea, E. Planning and Evaluating Nature-Based Solutions for Watershed Investment Programs with a SMART Perspective Using a Distributed Modeling Tool. Water (Basel) 2023, 15, 3388.

- Talukdar, P.; Kumar, B.; Kulkarni, V. V. A Review of Water Quality Models and Monitoring Methods for Capabilities of Pollutant Source Identification, Classification, and Transport Simulation. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2023, 22, 653–677. [CrossRef]

- Dr. Amit Krishan; Dr. Shweta Yadav; Ankita Srivastava Water Pollution’s Global Threat to Public Health : A Mini-Review. Int J Sci Res Sci Eng Technol 2023, 321–334. [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, A. Persistent Degradation: Global Water Quality Challenges and Required Actions. One Earth 2022, 5, 129–131. [CrossRef]

- Rajak, P.; Ganguly, A.; Nanda, S.; Mandi, M.; Ghanty, S.; Das, K.; Biswas, G.; Sarkar, S. Toxic Contaminants and Their Impacts on Aquatic Ecology and Habitats. In Spatial Modeling of Environmental Pollution and Ecological Risk; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 255–273.

- Benedini, M.; Tsakiris, G. Water Quality Modelling for Rivers and Streams; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013; Vol. 70; ISBN 978-94-007-5508-6.

- Ejigu, M.T. Overview of Water Quality Modeling. Cogent Eng 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Darji, J.; Lodha, P.; Tyagi, S. Assimilative Capacity and Water Quality Modeling of Rivers: A Review. Journal of Water Supply: Research and Technology-Aqua 2022, 71, 1127–1147. [CrossRef]

- Beven, K. How to Make Advances in Hydrological Modelling. Hydrology Research 2019, 50, 1481–1494. [CrossRef]

- Hofstra, N.; Kroeze, C.; Flörke, M.; van Vliet, M.T. Editorial Overview: Water Quality: A New Challenge for Global Scale Model Development and Application. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 2019, 36, A1–A5. [CrossRef]

- Natural Capital Project InVEST 3.13.0.Post6+ug.G6b07b42 User’s Guide.; 2022;

- Yen, H.; Daggupati, P.; White, M.; Srinivasan, R.; Gossel, A.; Wells, D.; Arnold, J. Application of Large-Scale, Multi-Resolution Watershed Modeling Framework Using the Hydrologic and Water Quality System (HAWQS). Water (Basel) 2016, 8, 164. [CrossRef]

- Rogéliz, C.A.; Vigerstol, K.; Galindo, P.; Nogales, J.; Raepple, J.; Delgado, J.; Piragauta, E.; González, L. WaterProof—A Web-Based System to Provide Rapid ROI Calculation and Early Indication of a Preferred Portfolio of Nature-Based Solutions in Watersheds. Water (Basel) 2022, 14, 3447.

- Nogales, J.; Rogéliz-Prada, C.; Cañon, M.A.; Vargas-Luna, A. An Integrated Methodological Framework for the Durable Conservation of Freshwater Ecosystems: A Case Study in Colombia’s Caquetá River Basin. Front Environ Sci 2023, 11, 1264392. [CrossRef]

- Chapra, S.C. Surface Water-Quality Modeling; 15th ed.; Waveland press: Illinois, 2008;

- Chapra, S.C. Surface Water Quality Modelling. Mc Graw Hill. ; 1997;

- Rojas, A. Aplicación de Factores de Asimilación Para La Priorización de La Inversión En Sistemas de Saneamiento Hídrico En Colombia. Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá D.C., 2011.

- Navas, A. Factores de Asimilación de Carga Contaminante En Ríos - Una Herramienta Para La Identificación de Estrategias de Saneamiento Hídrico En Países En Desarrollo, 2016.

- Mamani, J.A. Desarrollo de Un Modelo Numérico de Calidad Del Agua En Un Marco Probabilístico de Soporte a Las Decisiones a Escala Nacional. Thesis, Univerdad de los Andes: Bogotá D.C, 2022.

- Correa-Caselles, D. Metodología Para La Estimación Del Destino y Transporte de Mercurio Presente En Los Ríos de Colombia. Thesis, Univerdad de los Andes: Bogotá D.C, 2022.

- Rivera Gutiérrez, J.V. Evaluation of the Kinetics of Oxidation and Removal of Organic Matter in the Self-Purification of a Mountain River. Dyna (Medellin) 2015, 82, 183–193. [CrossRef]

- Hopcroft, J.; Tarjan, R. Algorithm 447: Efficient Algorithms for Graph Manipulation. Commun ACM 1973, 16, 372–378. [CrossRef]

- Tangi, M.; Schmitt, R.; Bizzi, S.; Castelletti, A. The CASCADE Toolbox for Analyzing River Sediment Connectivity and Management. Environmental Modelling & Software 2019, 119, 400–406. [CrossRef]

- Schwanghart, W.; Scherler, D. Short Communication: TopoToolbox 2 – MATLAB-Based Software for Topographic Analysis and Modeling in Earth Surface Sciences. Earth Surface Dynamics 2014, 2, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- ESRI, M.D. ArcHydro: GIS for Water Resources 2013.

- Winchell, M.; Srinivasan, R.; Di Luzio, M.; Arnold, J.G. ArcSWAT 2.3. 4 Interface For SWAT2005. Grassland, soil and research service, Temple, TX 2009.

- Flores, A.N.; Bledsoe, B.P.; Cuhaciyan, C.O.; Wohl, E.E. Channel-reach Morphology Dependence on Energy, Scale, and Hydroclimatic Processes with Implications for Prediction Using Geospatial Data. Water Resour Res 2006, 42, 6412. [CrossRef]

- Wohl, E.; Merritt, D. Prediction of Mountain Stream Morphology. Water Resour Res 2005, 41. [CrossRef]

- González, R. Determinación Del Comportamiento de La Fracción Dispersiva En Ríos Característicos de Montaña, UNAL: Bogotá D.C. , 2008.

- Schmitt, R.J.P.; Bizzi, S.; Castelletti, A. Tracking Multiple Sediment Cascades at the River Network Scale Identifies Controls and Emerging Patterns of Sediment Connectivity. Water Resour Res 2016, 52, 3941–3965. [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, G. V.; Parker, G. Physical Basis for Quasi-Universal Relationships Describing Bankfull Hydraulic Geometry of Sand-Bed Rivers. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 2011, 137, 739–753. [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Wilcock, P.R.; Paola, C.; Dietrich, W.E.; Pitlick, J. Physical Basis for Quasi-Universal Relations Describing Bankfull Hydraulic Geometry of Single-Thread Gravel Bed Rivers. J Geophys Res Earth Surf 2007, 112. [CrossRef]

| Attributes | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ReachID | - | Unique positive integer numeric identifier of each reach in the topological network |

|

FromNode |

- |

Positive integer numeric identifier of the initial node of a reach of the topological network. |

|

ToNode |

- |

Positive integer numerical identifier of the end node of a reach of the topological network. |

|

ReachType |

- |

Identifies whether the reach represents a plain or mountain river. If false is specified, the tool will assume that the reach represents a plain river. To define whether a river is a plain or a mountain river, a first criterion may be to assume that the former is limited by capacity (slope ≤0.025 m/m) and the latter by supply (slope >0.025 m/m), this, following the slope thresholds defined by [30]. A second criterion may be to use the slope threshold defined by [31] to define whether a river is mountain (slope >0.002 m/m) or plain (slope <0.002 m/m). |

|

RiverMouth |

- |

Identifies the river reach that corresponds to the basin closure point. If the value is false, it is considered not to be a closure point reach. |

|

** |

dimensionless |

The tool estimates the dispersive fraction following the criteria of [32]. For the sections of the topological network representing mountain rivers, an overall value of 0.27 is considered, while for plain rivers it is 0.40. |

|

|

day |

is solute velocity (m/s); β is the effective delay coefficient. According to [32] the effective delay coefficient for mountain rivers has an overall magnitude of 1.10 while for plain rivers it is 2.0. |

|

** |

day |

|

|

** |

day |

|

|

L |

m |

River length representing the reach in the topological network |

|

Z |

m.a.s.l |

Average elevation of the river representing the reach in the topological network |

|

A |

m2 |

Drainage area of the river representing the reach in the topological network, accumulated up to the ToNode of the reach |

|

Q |

m3/s |

Average discharge of the river representing the reach in the topological network, for a selected discharge scenario |

|

W |

m |

Average width of the river's cross-section representing the reach in the topological network, for the selected discharge scenario. The width can be estimated from the DEM, satellite imagery [26,33], physically-based relationships [34,35], field studies, or global datasets. |

| H | m | Average depth of the water column in the river representing the reach in the topological network, for the selected discharge scenario. The depth can be estimated from physically-based relationships [34,35], field studies, or global datasets. |

|

U |

m/s |

Average velocity of the water column in the river representing the reach in the topological network, for the selected discharge scenario. The velocity can be derived by continuity or through physically-based relationships [34,35] as well as from field studies or global datasets. |

|

S |

m/m |

Slope of the river representing the reach in the topological network. The slope can be estimated from the DEM, field studies, or global datasets. |

|

T |

°C |

Average river water temperature representing the reach of the topological network. |

|

Load_T |

°C |

Average temperature of the wastewater discharges entering the river representing the reach of the topological network. |

|

Load_SS* |

mg/d |

The load of solids entering the river reach. |

|

Load_X* |

MPN/day |

Total coliform load entering the river reach. |

|

Load_NO* |

mg/day |

Organic nitrogen load entering the river reach. |

|

Load_NH4* |

mg/day |

Ammonia nitrogen load entering the river reach. |

|

Load_NO3* |

mg/day |

Nitrates load entering the river reach. |

|

Load_PO* |

mg/day |

Organic phosphorus load entering the river reach. |

|

Load_PI* |

mg/day |

Inorganic phosphorus load entering the river reach. |

| Load_OM* | mg/day | Organic matter load entering the river reach. |

| Load_DO* | mg/day | The load of dissolved oxygen entering the river reach. |

| Load_Hg0* | mg/day | Elemental mercury load entering the river reach. |

| Load_Hg2* | mg/day | Divalent mercury load entering the river reach. |

| Load_MeHg* | mg/day | Methylmercury load entering the river reach. |

| Water Quality Determinants | Parameter | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | No parameters | - | - |

|

Suspended Solids |

|

m/day |

Sedimentation velocity |

|

Pathogenic Organisms |

|

dimensionless |

Constant decay of pathogenic organisms (mortality) |

| dimensionless | Fraction of pathogenic organisms adsorbed on solid particles | ||

| m/day | Sedimentation velocity of the adsorbed fraction of pathogens on solid particles | ||

|

Organic Nitrogen |

|

1/day |

Decay rate by hydrolysis of organic nitrogen |

| m/day | Sedimentation velocity of organic nitrogen | ||

|

Ammoniacal Nitrogen |

|

1/day |

Nitrification decay rate |

|

Nitrates |

|

1/day |

Denitrification rate |

| dimensionless | Factor considering the effect of low oxygen on denitrification | ||

|

Organic Phosphorus |

|

1/day |

Organic phosphorus hydrolysis decay rate |

| m/day | Organic phosphorus sedimentation velocity | ||

|

Inorganic Phosphorus |

|

m/day |

Inorganic phosphorus sedimentation velocity |

|

Organic Matter |

|

1/day |

Organic matter oxidation decay rate |

| dimensionless | Factor considering the effect of low oxygen on organic matter | ||

|

Oxygen Deficit |

|

1/day |

Reaeration rate |

|

Elemental Mercury |

|

m/day |

Elemental mercury volatilization velocity |

| 1/day | Elemental mercury oxidation reaction rate | ||

| 1/day | Oxidation decay rate of mercury | ||

|

Divalent Mercury |

|

1/day |

Adsorbed divalent mercury methylation rate |

| 1/day | Dissolved divalent mercury methylation rate | ||

| dimensionless | Fraction of divalent mercury adsorbed on solid particles | ||

| m/day | Sedimentation velocity of divalent mercury | ||

|

Methyl mercury |

|

dimensionless |

Fraction of methyl mercury adsorbed on solid particles |

| m/day | Sedimentation velocity of methyl mercury |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).