3. Implementation and Experimental Evaluation of Clustering Techniques

This section explores the application and testing of various clustering techniques to evaluate their performance in partitioning datasets into distinct clusters. The analysis is performed independent of compression objectives, focusing on how effectively each method segments data and adapts to varying configurations. By examining how these techniques respond to changes in parameter values, the study reveals their strengths and limitations in adapting to data patterns.

Figure 1 illustrates the legend used for clustering-related visualizations. It assigns specific colors to each cluster (Cluster 1 through Cluster 10), with additional markers for centroids (red star), noisy data points (black dot), and unclustered points (black solid).

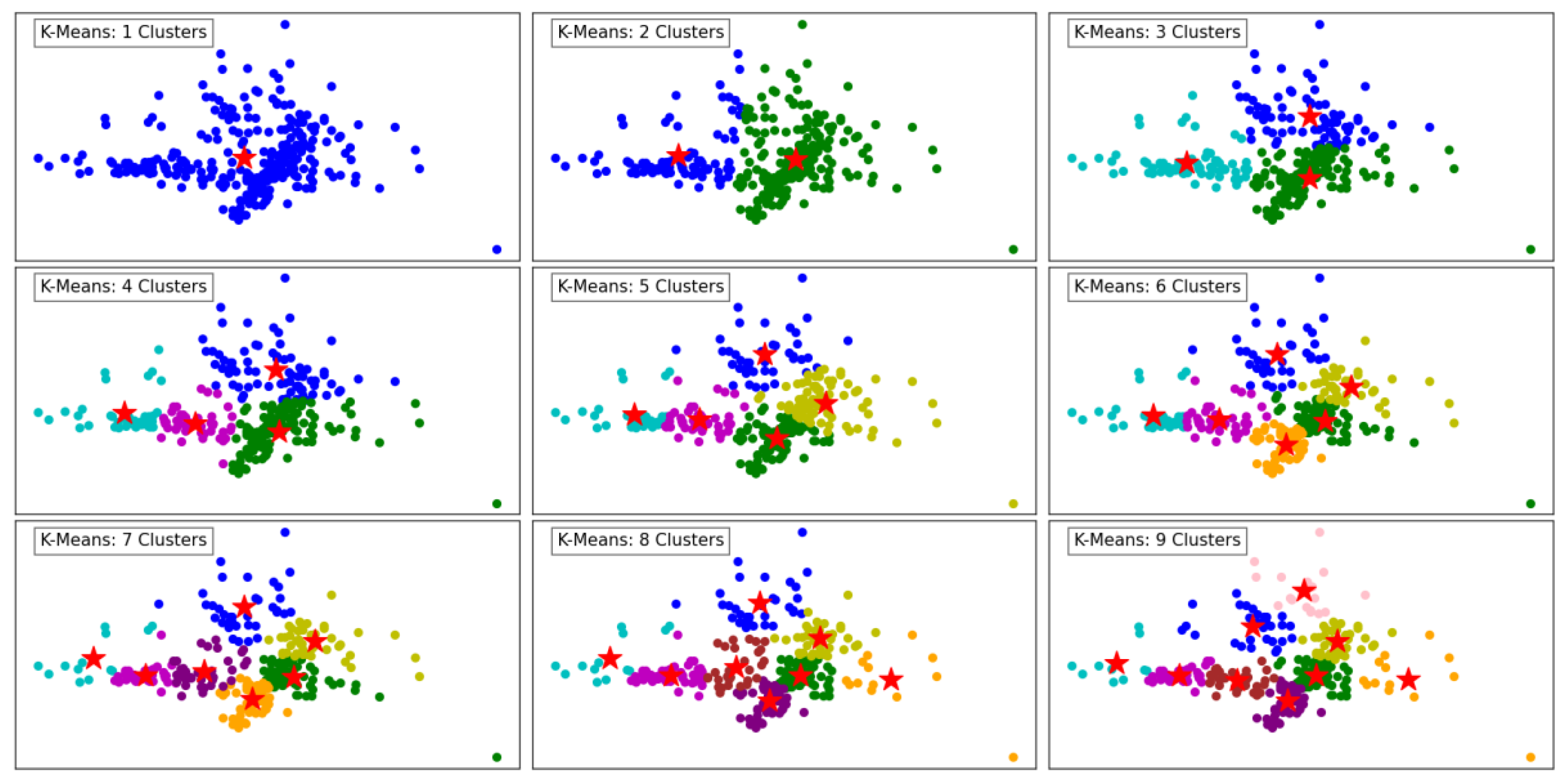

Figure 2 demonstrates the performance of the K-Means clustering algorithm across varying numbers of clusters, ranging from 1 to 9. In the first panel, with a single cluster, all data points are grouped together, resulting in a simplistic representation with limited separation between different regions. As the number of clusters increases to 2 and 3, a more distinct segmentation emerges, reflecting K-Means' ability to partition the data into groups that minimize intra-cluster variance.

At 4 and 5 clusters, the algorithm begins to capture finer structures in the dataset, effectively separating points based on their proximity and density. This segmentation reflects the algorithm's ability to balance between over-simplification and over-segmentation. As the number of clusters increases further to 6, 7, and beyond, the algorithm divides the data into smaller, more granular groups. This results in more localized clusters, potentially overfitting if the dataset does not naturally support such fine granularity.

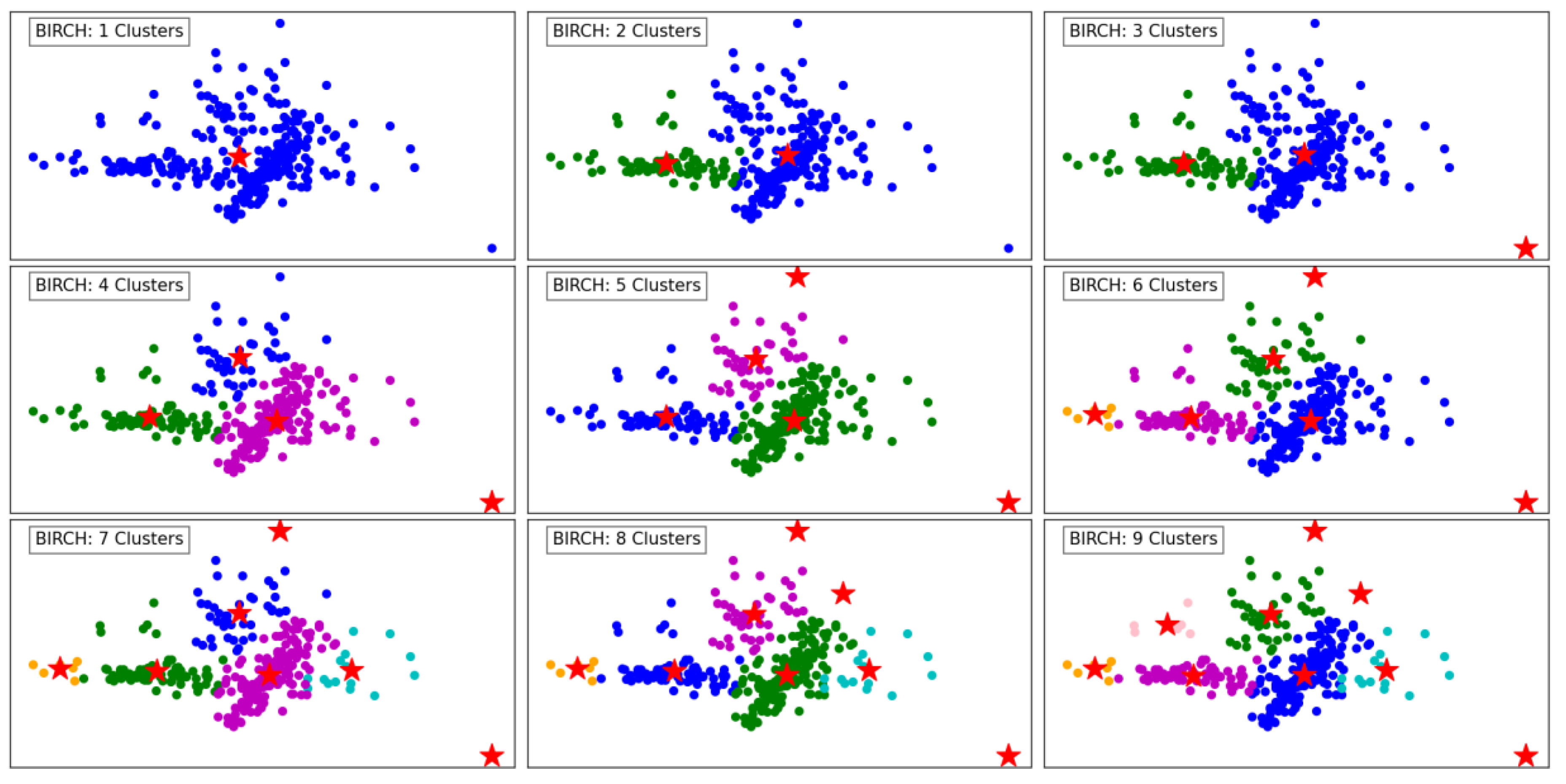

Figure 3 illustrates the performance of the BIRCH algorithm as the number of clusters increases from 1 to 9. With a single cluster, all data points are aggregated into one group, offering no segmentation and overlooking the underlying structure of the data. As the number of clusters increases to 2 and 3, the algorithm begins to create more meaningful separations, delineating regions of the data based on density and distribution.

With 4 and 5 clusters, the segmentation becomes more refined, capturing the natural groupings within the dataset. BIRCH effectively identifies cohesive regions, even in the presence of outliers, as indicated by isolated points in the scatterplot. The hierarchical nature of BIRCH is evident as it progressively organizes the data into clusters, maintaining balance and reducing computational complexity.

At higher cluster counts, such as 7, 8, and 9, the algorithm demonstrates its capacity to detect smaller, more localized clusters. However, this can lead to over-segmentation, where naturally cohesive groups are divided into sub-clusters. The presence of outliers remains well-managed, with some points clearly designated as noise. Overall, BIRCH shows its strength in clustering data hierarchically, balancing efficiency and accuracy, especially for datasets with varying densities and outliers.

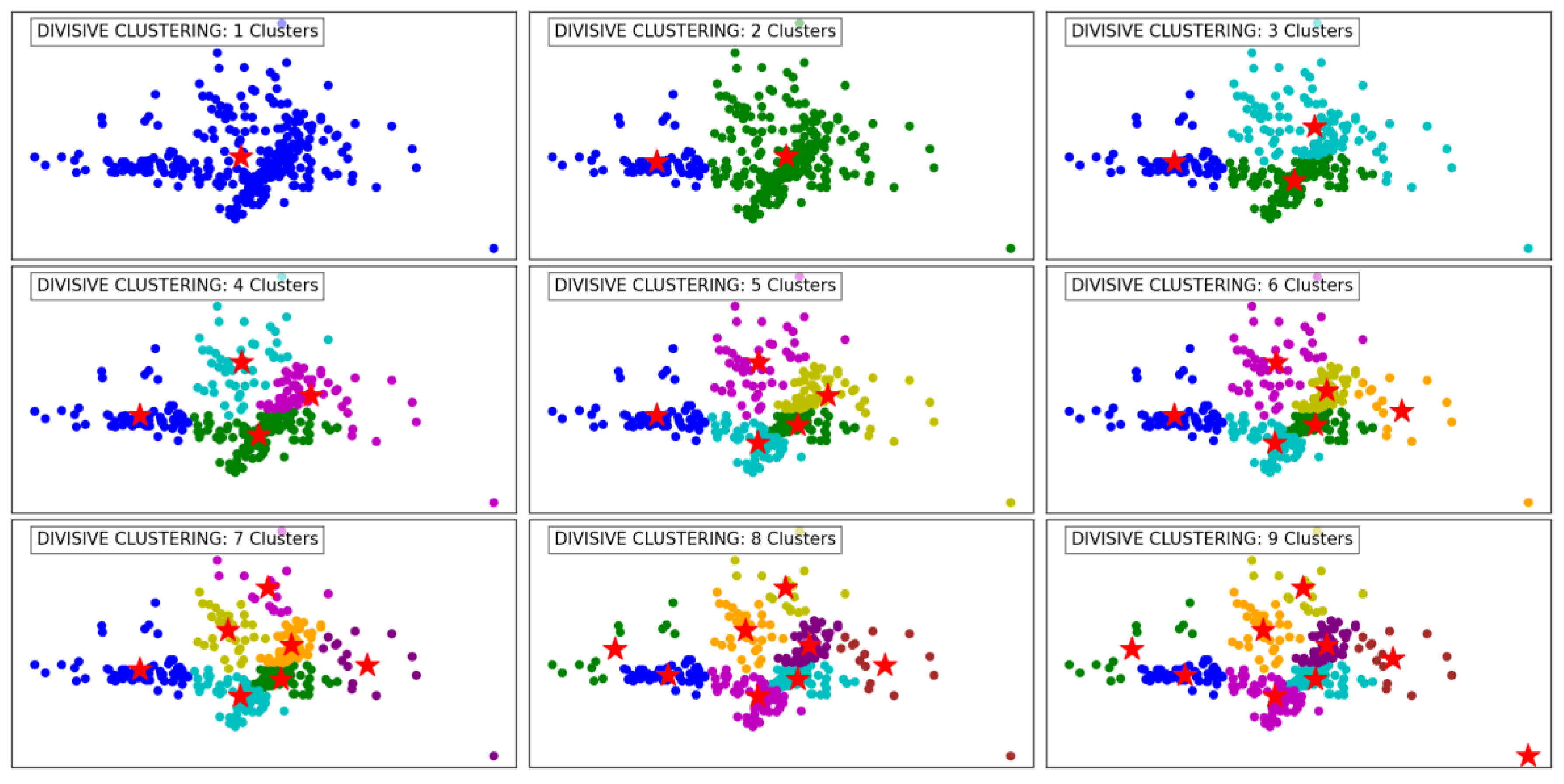

Figure 4 demonstrates the progression of the Divisive Clustering algorithm as it separates the data into an increasing number of clusters, from 1 to 9. Initially, with a single cluster, all data points are grouped together, ignoring any inherent structure in the data. This provides no meaningful segmentation and highlights the starting point of the divisive hierarchical approach.

As the number of clusters increases to 2 and 3, the algorithm begins to partition the data into distinct groups based on its inherent structure. These initial divisions effectively segment the data into broad regions, capturing the overall distribution while maintaining cohesion within the clusters.

With 4 to 6 clusters, the algorithm refines these groupings further, identifying smaller clusters within the larger ones. This refinement captures finer details in the dataset's structure, ensuring that densely populated areas are segmented appropriately. At this stage, Divisive Clustering demonstrates its ability to split clusters hierarchically, providing meaningful separations while maintaining a logical hierarchy.

At higher cluster counts, such as 7 to 9, the algorithm continues to divide existing clusters into smaller subgroups. This leads to a granular segmentation, effectively capturing subtle variations within the data. However, as the number of clusters increases, there is a risk of over-segmentation, where cohesive clusters are fragmented into smaller groups. Despite this, the algorithm handles outliers effectively, ensuring that isolated points are not erroneously grouped with larger clusters. Overall, Divisive Clustering effectively balances granularity and cohesion, making it well-suited for hierarchical data exploration.

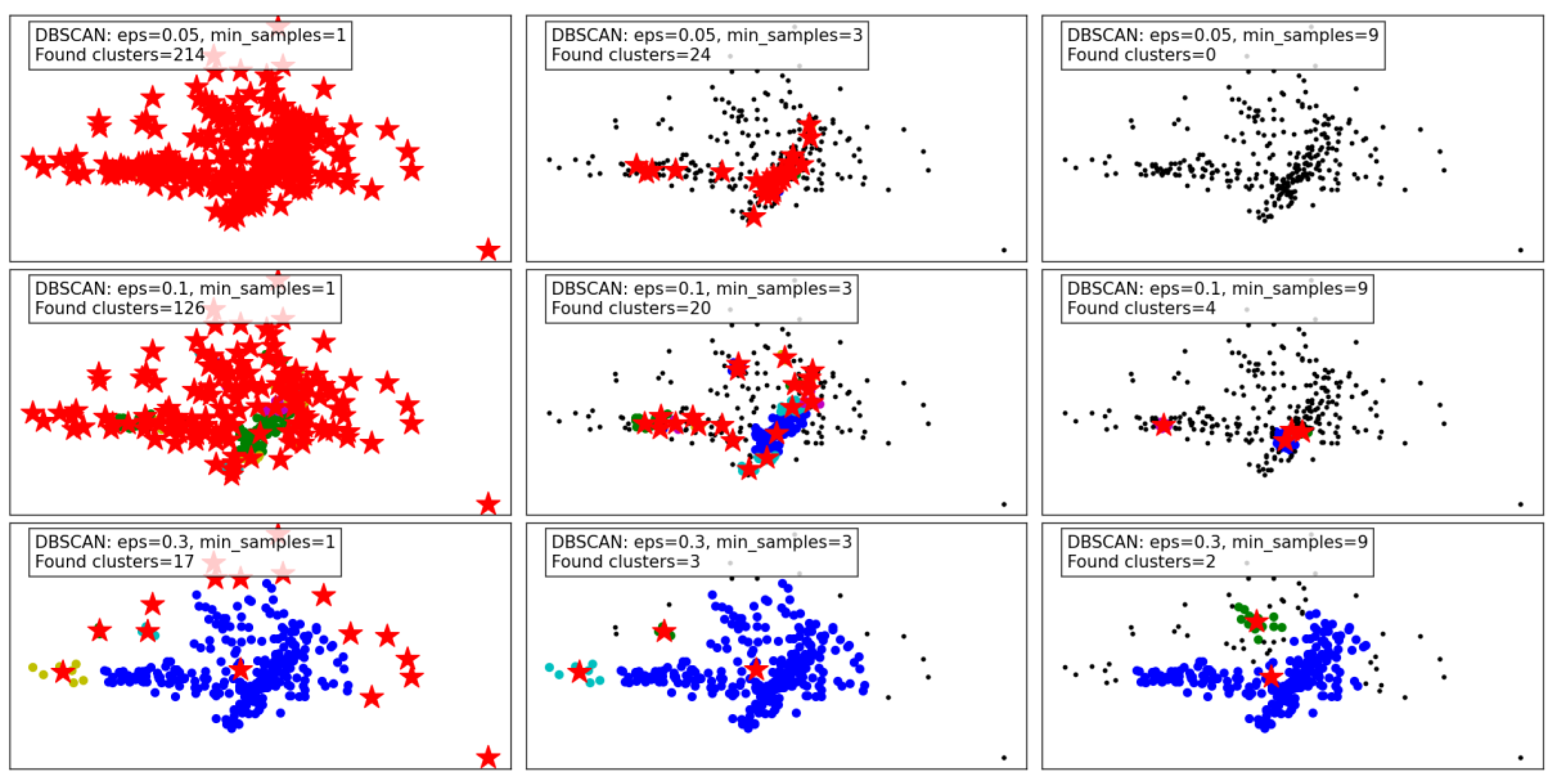

Figure 5 illustrates the performance of the DBSCAN algorithm under varying eps and

min_samples parameter configurations. DBSCAN's ability to detect clusters of varying density and its handling of noise are evident in the results.

With a small eps of 0.05 and min_samples (or minPts) set to 1, the algorithm identifies a large number of clusters (214), as the tight neighborhood criterion captures even minor density variations. This leads to over-segmentation and a significant amount of noise classified as individual clusters, reducing the interpretability of the results. Increasing min_samples to 3 under the same eps reduces the number of clusters (24) by merging smaller groups, though many data points remain unclustered. At min_samples 9, no clusters are identified, as the eps is too restrictive to form valid clusters.

When eps is increased to 0.1, the algorithm becomes less restrictive, capturing larger neighborhoods. For min_samples 1, the number of clusters decreases to 126, reflecting better grouping of data points. At min_samples 3, the results improve further, with fewer clusters (20) and more cohesive groupings. However, at min_samples 9, only 4 clusters are detected, with many points treated as noise.

With the largest eps value of 0.3, the algorithm identifies very few clusters, as the larger neighborhood radius groups most points into a few clusters. At min_samples 1, only 17 clusters are found, indicating over-generalization. For min_samples 3, the clusters reduce to 3, with most noise eliminated. Finally, at min_samples 9, only 2 clusters remain, demonstrating high consolidation but potentially missing finer details.

In summary, DBSCAN's clustering performance is highly sensitive to eps and min_samples. Smaller eps values capture local density variations, leading to over-segmentation, while larger values risk oversimplifying the data. Higher min_samples values improve robustness by eliminating noise but can under-cluster sparse regions. The results highlight DBSCAN's flexibility but emphasize the importance of parameter tuning for optimal performance.

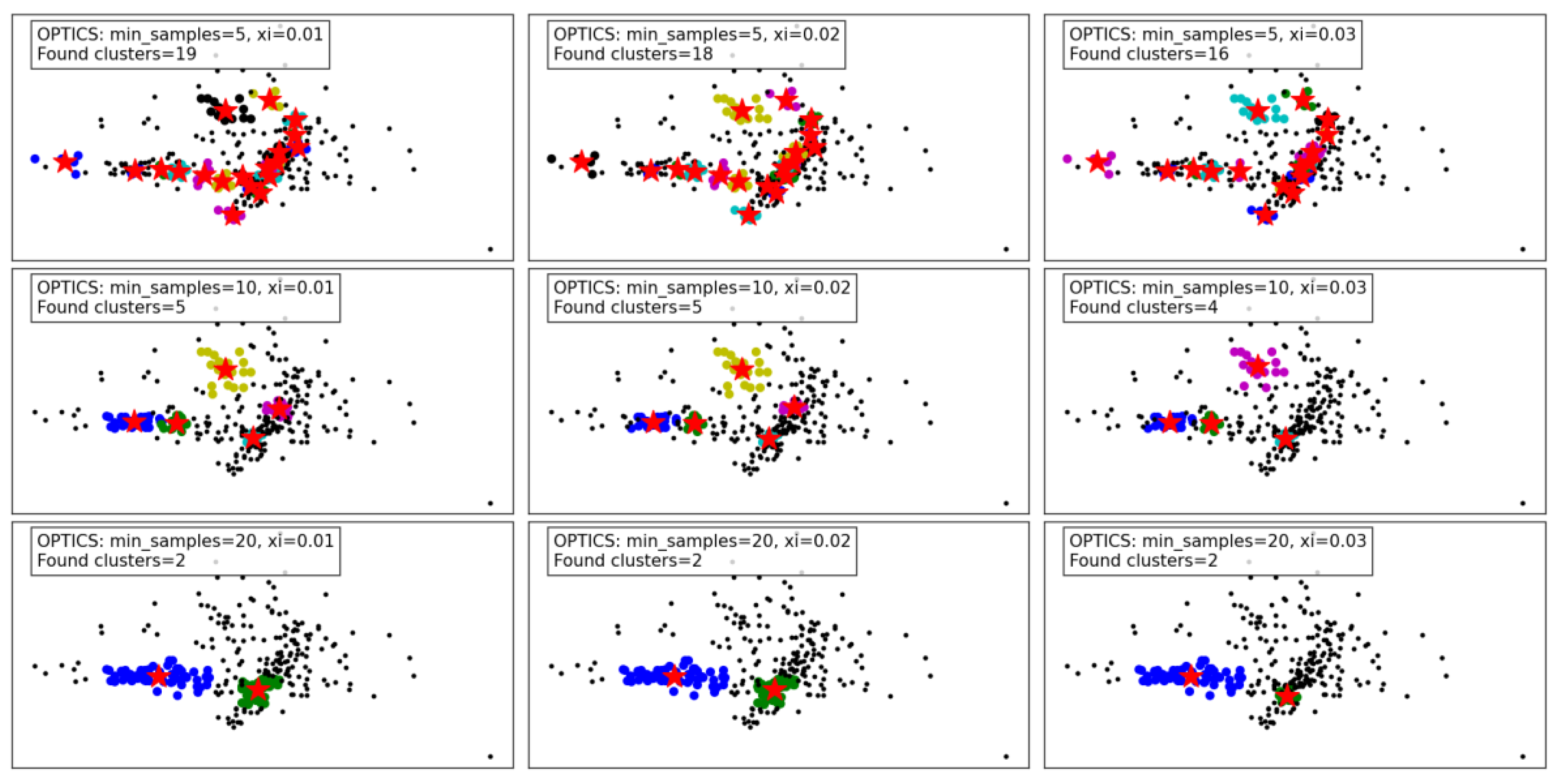

Figure 6 demonstrates the performance of the OPTICS algorithm under varying

min_samples and

xi parameters. OPTICS, known for its ability to detect clusters of varying densities and hierarchical structures, shows its versatility and sensitivity to parameter adjustments.

For min_samples set to 5 and xi varying from 0.01 to 0.03, the algorithm identifies a relatively large number of clusters. At xi = 0.01, 19 clusters are detected, capturing fine density variations. As xi increases to 0.02 and 0.03, the number of clusters decreases slightly to 18 and 16, respectively. This reflects OPTICS' tendency to merge smaller clusters as the threshold for cluster merging becomes more lenient. Despite this reduction, the algorithm still captures intricate cluster structures and maintains a high level of detail.

When min_samples increases to 10, the number of clusters decreases significantly. At xi = 0.01, only 5 clusters are found, reflecting stricter density requirements for forming clusters. As xi increases to 0.02 and 0.03, the cluster count further decreases to 5 and 4, respectively, with some finer details being lost. This highlights the impact of min_samples in reducing noise sensitivity but at the cost of losing smaller clusters.

For min_samples set to 20, the clustering results are highly simplified. Across all xi values, only 2 clusters are consistently detected, indicating a significant loss of detail and overgeneralization. While this reduces noise and improves cluster compactness, it risks oversimplifying the dataset and merging distinct clusters.

Overall, the results show that OPTICS performs well with low min_samples and small xi values, capturing fine-grained density variations and producing detailed cluster structures. However, as these parameters increase, the algorithm shifts towards merging clusters and simplifying the structure, which may lead to a loss of critical information in datasets with complex density variations. These findings emphasize the importance of careful parameter tuning to balance detail retention and noise reduction.

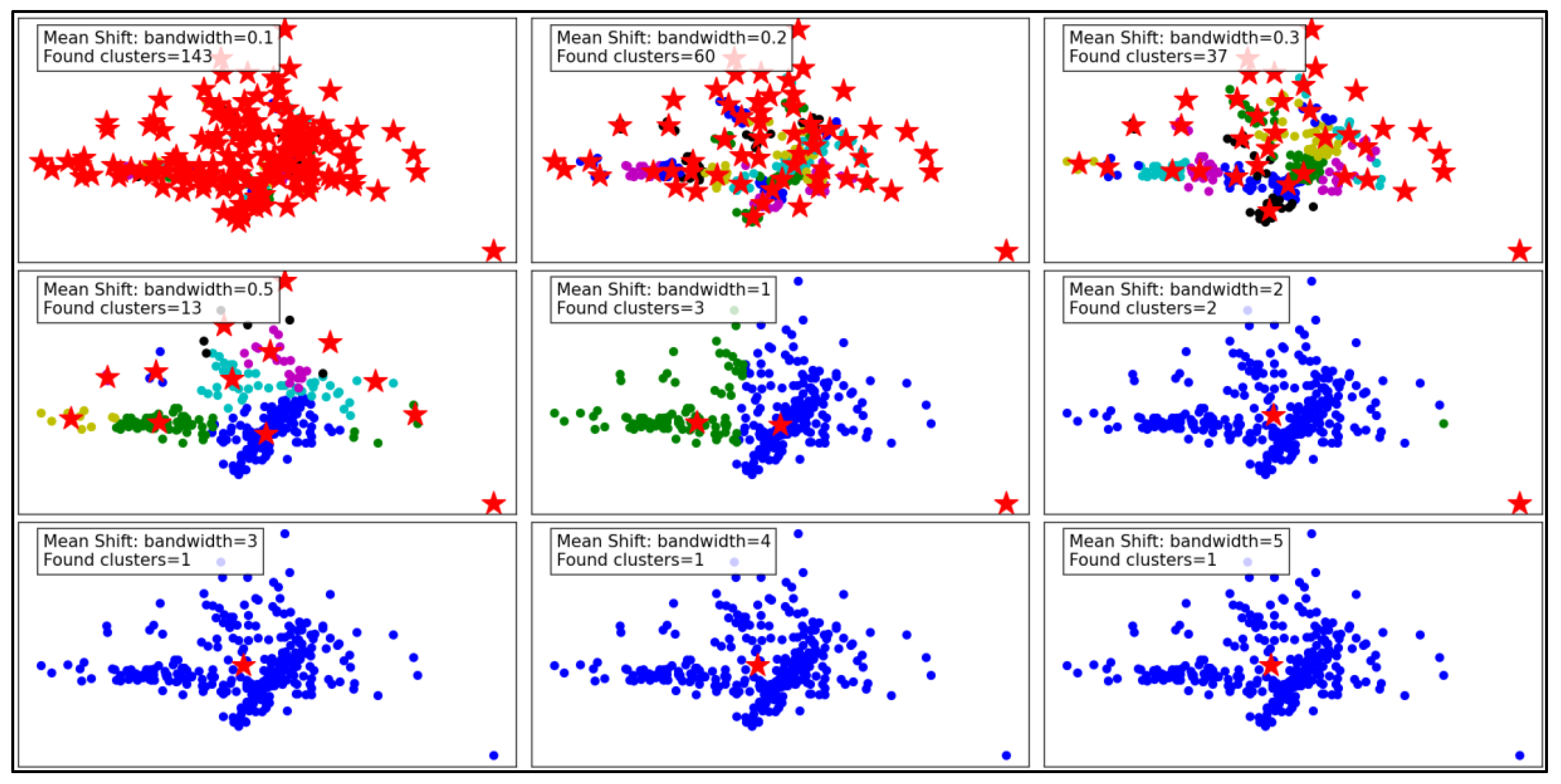

Figure 7 illustrates the performance of the Mean Shift clustering algorithm applied to the dataset, with varying bandwidth values from 0.1 to 5. Mean Shift is a non-parametric clustering method that groups data points based on the density of data in a feature space. The bandwidth parameter, which defines the kernel size used to estimate density, plays a critical role in determining the number and quality of clusters.

At a small bandwidth of 0.1, the algorithm detects 143 clusters, indicating a high sensitivity to local density variations. This results in many small clusters, capturing fine details in the dataset. However, such granularity may lead to over-segmentation, with clusters potentially representing noise rather than meaningful groupings. As the bandwidth increases to 0.2 and 0.3, the number of clusters decreases to 60 and 37, respectively. The algorithm begins merging smaller clusters, creating a more structured and meaningful segmentation while still retaining some level of detail.

With a bandwidth of 0.5, the cluster count drops sharply to 13, showing a significant reduction in granularity. The clusters become larger and less detailed, which may improve computational efficiency but risks oversimplifying the dataset. As the bandwidth continues to increase to 1 and beyond (e.g., 2, 3, 4, and 5), the number of clusters reduces drastically to 2 or even 1. At these high bandwidths, the algorithm generalizes heavily, resulting in overly simplistic cluster structures. This can lead to the loss of critical information and may render the clustering ineffective for datasets requiring fine-grained analysis.

In summary, the Mean Shift algorithm's clustering performance is highly dependent on the bandwidth parameter. While smaller bandwidths allow for detailed and fine-grained clustering, they may result in over-segmentation and sensitivity to noise. Larger bandwidths improve generalization and computational efficiency but at the cost of significant loss of detail and potential oversimplification. Optimal bandwidth selection is essential to balance the trade-off between capturing meaningful clusters and avoiding over-generalization.

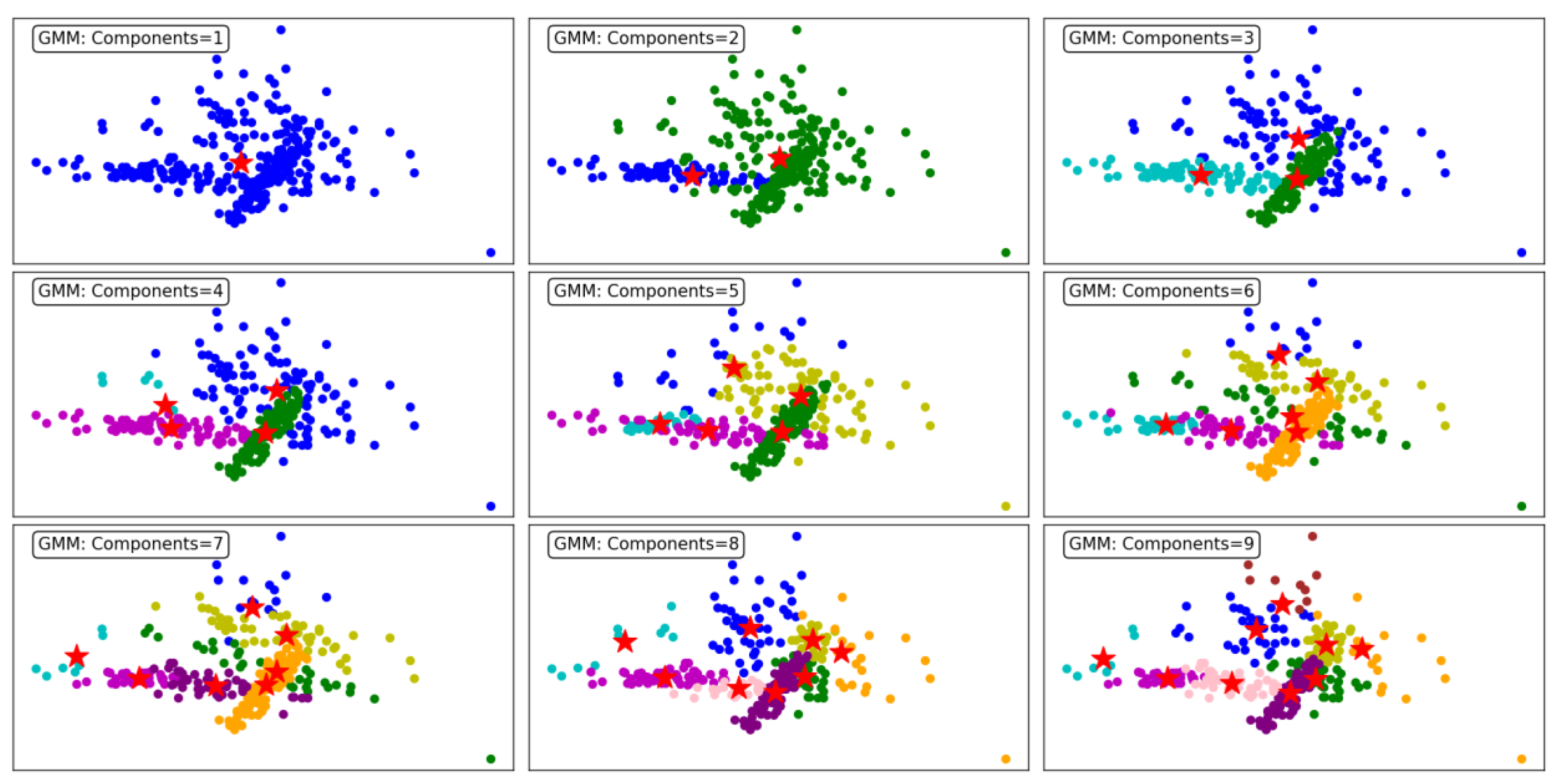

Figure 8 demonstrates the performance of the GMM clustering algorithm, evaluated across different numbers of components, ranging from 1 to 9. GMM is a probabilistic model that assumes data is generated from a mixture of several Gaussian distributions, making it flexible for capturing complex cluster shapes. The number of components directly determines the number of clusters.

With a single component, the GMM produces a single, undifferentiated cluster, resulting in poor segmentation. All data points are grouped together, reflecting the model's inability to distinguish underlying structures in the dataset. As the number of components increases to 2 and 3, the algorithm begins to form meaningful clusters, capturing distinct groupings in the data. However, overlapping clusters are still evident, indicating limited separation.

At 4 components, the clustering becomes more refined, and distinct patterns start emerging. The data points are grouped more accurately into cohesive clusters, demonstrating the ability of GMM to model underlying structures. As the number of components increases to 5, 6, and 7, the algorithm continues to improve in capturing finer details and separating overlapping clusters. This results in a more accurate representation of the dataset, as observed in the clearer segmentation of the clusters.

By 8 and 9 components, the clustering is highly granular, with minimal overlap between clusters. However, the increased number of components may lead to overfitting, where the algorithm begins to model noise as separate clusters. This trade-off highlights the importance of carefully selecting the number of components to balance accuracy and generalizability.

In summary, GMM effectively models the dataset's underlying structure, with improved clustering performance as the number of components increases. However, excessive components can lead to overfitting, underscoring the need for optimal parameter selection. This makes GMM a versatile and robust choice for applications requiring probabilistic clustering.

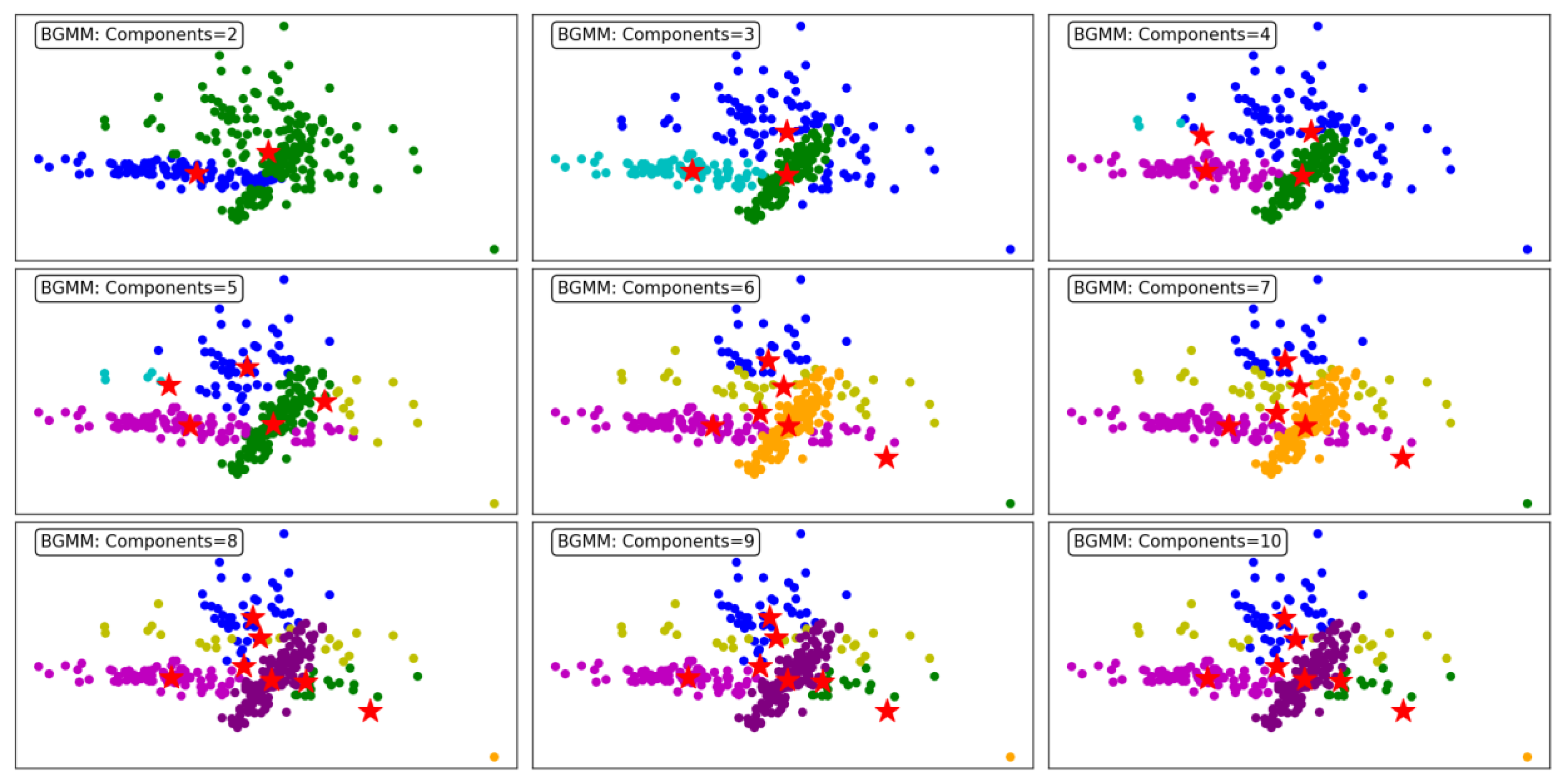

Figure 9 illustrates the clustering performance of the BGMM clustering algorithm across a range of component counts from 2 to 10. BGMM, unlike GMM, incorporates Bayesian priors to determine the optimal number of components, providing a probabilistic framework for clustering. This makes BGMM robust to overfitting, as it naturally balances the trade-off between model complexity and data representation.

At the lower component counts (2 to 3 components), BGMM effectively identifies broad clusters in the dataset. For 2 components, the algorithm forms two distinct clusters, offering a coarse segmentation of the data. Increasing the components to 3 enhances granularity, with the addition of a third cluster capturing finer details within the dataset.

As the number of components increases to 4, 5, and 6, BGMM achieves progressively finer segmentation, forming clusters that better align with the underlying data structure. Each additional component introduces greater specificity in capturing subgroups within the data, reflected in well-defined clusters. The transitions between clusters are smooth, indicating the algorithm's ability to probabilistically assign points to clusters, even in overlapping regions.

From 7 to 9 components, BGMM continues to refine the clustering process, but the benefits of additional components start to diminish. At 9 and 10 components, the model begins to overfit, with some clusters capturing noise or forming redundant groups. Despite this, the clusters remain relatively stable, showcasing BGMM's ability to avoid drastic overfitting compared to GMM.

In conclusion, BGMM demonstrates robust clustering performance across varying component counts. While the algorithm effectively captures complex data structures, it benefits from the Bayesian prior that discourages excessive components. This makes BGMM particularly suited for scenarios where a balance between precision and generalizability is crucial.

Figure 9 emphasizes the importance of selecting an appropriate number of components to maximize clustering efficiency and accuracy.

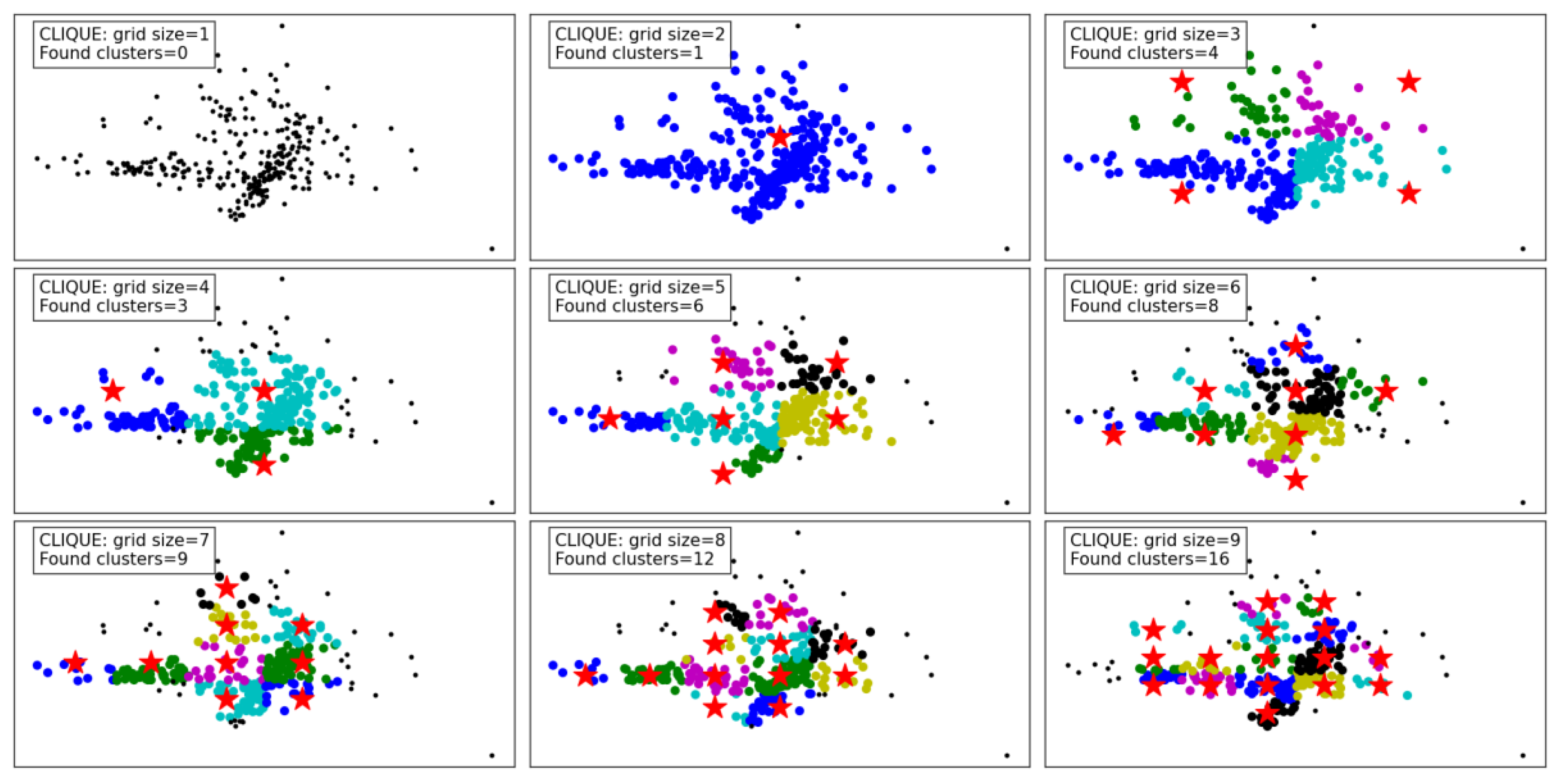

Figure 10 demonstrates the clustering results of the CLIQUE algorithm under varying grid sizes, showcasing its performance and adaptability. At a grid size of 1, no clusters are detected, which indicates that the granularity is too coarse to capture meaningful groupings in the dataset. As the grid size increases to 2 and 3, the algorithm begins to detect clusters, albeit sparingly, with one and four clusters identified, respectively. This improvement in cluster detection shows that a finer grid allows the algorithm to better partition the space and identify denser regions.

From grid size 4 to 6, there is a steady increase in the number of clusters found, reaching up to eight clusters. The results reveal that moderate grid sizes provide a balance between capturing meaningful clusters and avoiding excessive noise or fragmentation in the data. Notably, the identified clusters at these grid sizes appear well-separated and align with the data's inherent structure.

For larger grid sizes, such as 7 to 9, the number of clusters continues to grow, with up to 16 clusters detected. However, these finer grids risk over-partitioning the data, potentially splitting natural clusters into smaller subgroups. While the increase in clusters reflects a more detailed segmentation of the data, it might not always represent the most meaningful groupings, especially in practical applications.

Overall, the CLIQUE algorithm demonstrates its ability to adapt to different grid sizes, with the grid size playing a critical role in balancing cluster resolution and interpretability. Lower grid sizes result in under-detection of clusters, while excessively high grid sizes may lead to over-fragmentation. Moderate grid sizes, such as 4 to 6, seem to strike the optimal balance, capturing the data's underlying structure without overcomplicating the clustering.

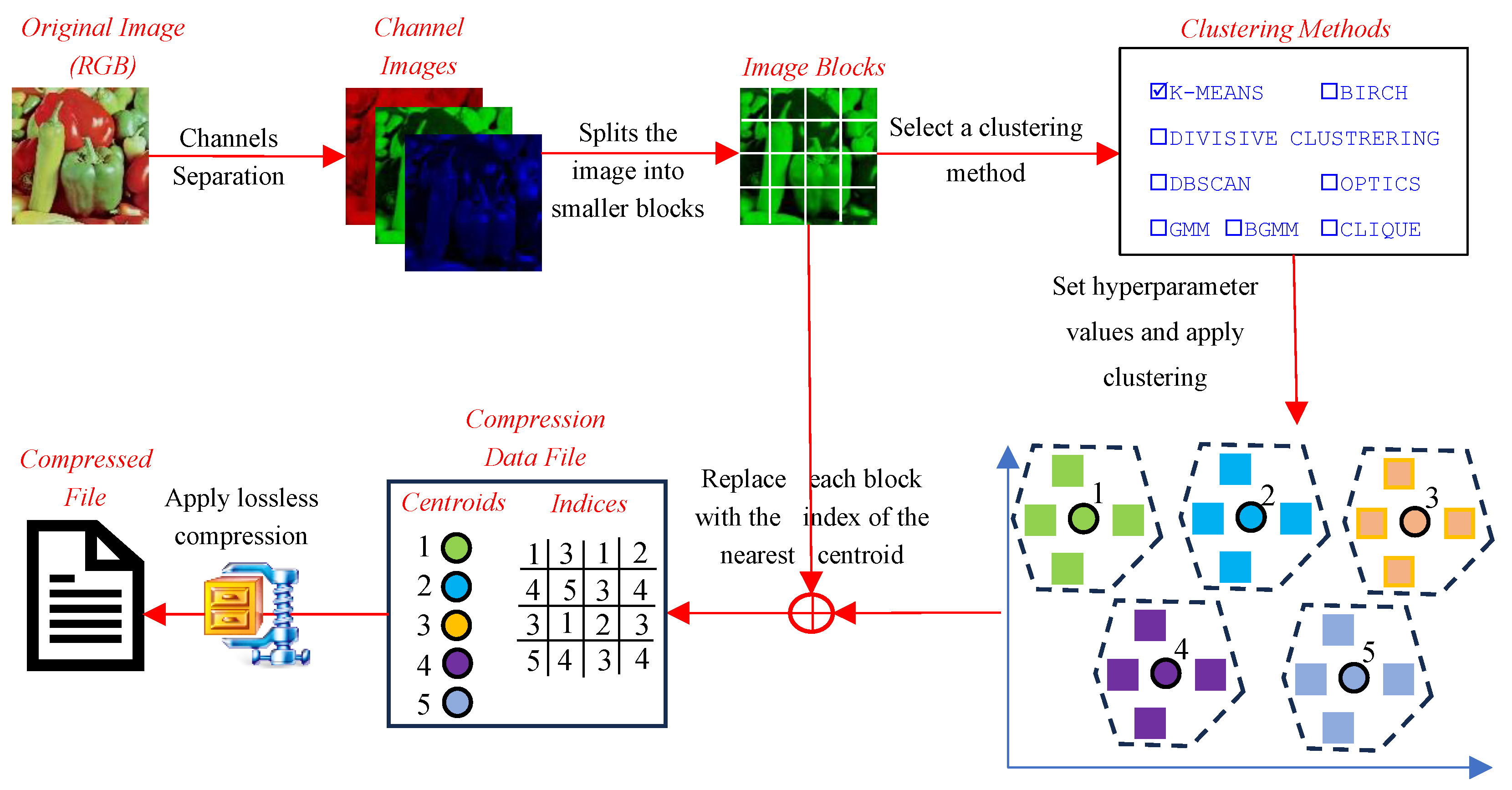

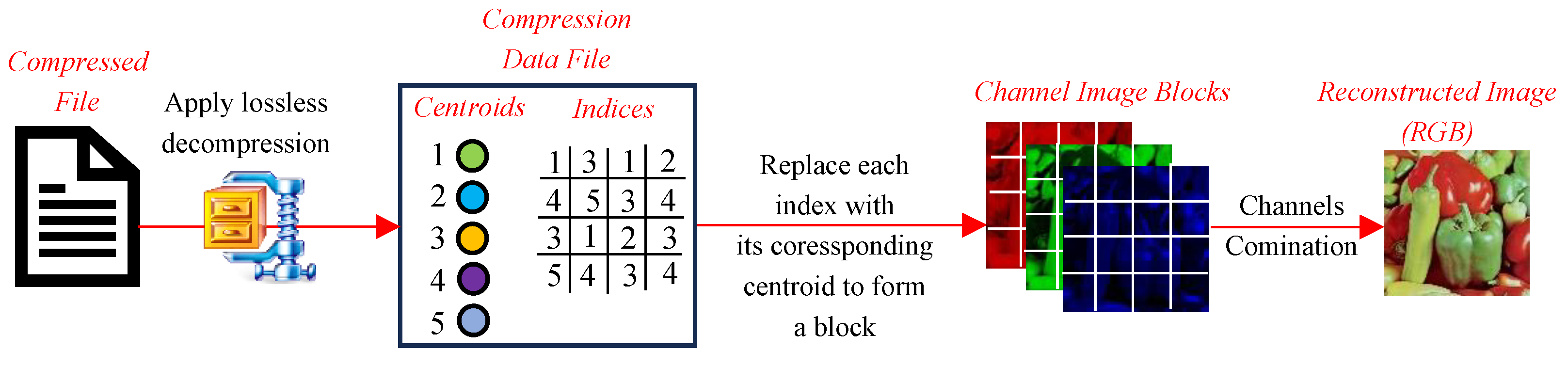

6. Comprehensive Performance Analysis of Clustering Techniques in Image Compression

This section presents the performance evaluation of various clustering-based image compression techniques. Each method was applied to compress images using the proposed framework, followed by quantitative and qualitative assessments of the reconstructed images. Metrics such as CR, BPP, and SSIM were calculated to gauge the trade-offs between compression efficiency and image quality. The results highlight the strengths and limitations of each method, offering insights into their suitability for different compression scenarios. The findings are summarized and analyzed in the subsequent subsections.

The initial experimental results for image compression presented in this section utilized the widely recognized "Peppers" image (

Figure 13), obtained from the Waterloo dataset [

52], a benchmark resource for image processing research.

6.1. Kmeans Clustering for Compression

Figure 14 illustrates the results of image compression using the K-Means clustering algorithm with different block sizes and numbers of clusters. Starting with the smallest block size of 2x2 pixels, the images exhibit high SSIM values, close to 1, indicating a strong similarity to the original image. This high SSIM is expected because the small block size allows for finer granularity in capturing image details. However, as the number of clusters increases from 31 to 255, there is a noticeable trade-off between CR and BPP. When the number of clusters is low, the CR is relatively high (14.14) but the BPP is low (1.70), indicating efficient compression. As the number of clusters increases, the CR decreases significantly (6.13), while the BPP increases to 3.91. This indicates that the image quality is maintained at the cost of compression efficiency, as more clusters mean more distinct pixel groups, which reduces the compression ratio.

When the block size is increased to 4x4 pixels, the reconstructed images still maintain high SSIM values, though slightly lower than with the 2x2 block size. This decrease in SSIM is due to the larger block size capturing less fine detail, making the reconstruction less accurate. The compression ratio improves significantly, reaching as high as 48.09 when using 31 clusters. However, as with the 2x2 block size, increasing the number of clusters leads to a reduction in the compression ratio (down to 18.30 with 255 clusters) and an increase in BPP, indicating that more data is needed to preserve the image quality. The images with 4x4 blocks and a higher number of clusters show a good balance between compression and quality, making this configuration potentially optimal for certain applications where moderate image quality is acceptable with better compression efficiency.

The 8x8 block size introduces more noticeable artifacts in the reconstructed images, particularly as the number of clusters increases. Although the compression ratio remains high, the SSIM values start to drop, especially as we move to higher cluster counts. The BPP values are also lower compared to smaller block sizes, indicating higher compression efficiency. However, this comes at the expense of image quality, as larger blocks are less effective at capturing the fine details of the image, leading to a more pixelated and less accurate reconstruction. The trade-off is evident here: while the compression is more efficient, the image quality suffers, making this configuration less desirable for applications requiring high visual fidelity.

Finally, the largest block size of 16x16 pixels shows a significant degradation in image quality, particularly when a high number of clusters are used. The SSIM values decrease noticeably, reflecting the loss of detail and the introduction of more visible artifacts. The compression ratios are very high, with a maximum CR of 48.20, but the images appear much more pixelated and less recognizable compared to those with smaller block sizes. This indicates that while large block sizes are highly efficient for compression, they are not suitable for scenarios where image quality is a priority. The BPP values also vary significantly, with lower cluster counts resulting in very low BPP, but as clusters increase, the BPP rises, indicating that the image quality improvements come at the cost of less efficient compression.

In summary, the

Figure 14 demonstrates that the K-Means clustering algorithm's effectiveness for image compression is highly dependent on the choice of block size and the number of clusters. Smaller block sizes with a moderate number of clusters offer a good balance between image quality and compression efficiency, making them suitable for applications where both are important. Larger block sizes, while more efficient in terms of compression, significantly degrade image quality and are less suitable for applications requiring high visual fidelity. The results highlight the need to carefully select these parameters based on the specific requirements of the application, whether it prioritizes compression efficiency, image quality, or a balance of both.

6.2. BIRCH Clustering for Compression

Figure 15 displays a series of reconstructed images using the BIRCH clustering algorithm applied to image compression. Starting with the block size of 2x2, the images exhibit varying levels of quality depending on the threshold and branching factor used. For a block size of 2x2, with a threshold of 0.1 and a branching factor of 10, the SSIM values range around 0.219 to 0.241, indicating a moderate similarity to the original image. The CR is low, around 1.75 to 1.85, and the BPP is high, ranging from 12.94 to 13.74, reflecting a lower compression efficiency and a higher level of detail retention. However, as the threshold increases to 0.5, while keeping the branching factor constant at 10, the SSIM decreases significantly, with values dropping to as low as 0.163 to 0.184, indicating a deterioration in image quality. Despite this, the CR slightly improves, suggesting that more aggressive compression is taking place at the expense of image quality.

When increasing the branching factor to 50, the SSIM values decrease even further, especially for the higher threshold of 0.5, where the SSIM drops to 0.036 and 0.126. This indicates that the reconstructed images lose significant detail and structure, becoming almost unrecognizable. The BPP remains high, suggesting that although a large amount of data is being retained, it is not contributing positively to the image quality. The CR does not show significant improvement, which suggests that the BIRCH algorithm with these parameters might not be efficiently clustering the blocks in a way that balances compression with quality.

Moving to a block size of 4x4, the images generally show a deterioration in SSIM compared to the smaller block size, with SSIM values dropping to below 0.1 in several cases, particularly when the threshold is set to 0.5. The CR slightly improves in some cases, but the BPP increases, indicating that even though more bits are used per pixel, the quality does not improve and, in some cases, worsens significantly. For example, with a threshold of 0.5 and a branching factor of 50, the SSIM is 0.219, which is slightly better than other configurations with the same block size, but still low.

In summary, the BIRCH algorithm appears to struggle with balancing compression and image quality in this context, especially with larger block sizes and higher thresholds. The SSIM values suggest that as the threshold and branching factor increase, the algorithm fails to maintain structural similarity, leading to poor-quality reconstructions. The CR and BPP metrics indicate that while compression is occurring, it is not efficiently capturing the important details needed to reconstruct the image well. This suggests that BIRCH may not be the optimal clustering method for this type of image compression, particularly with larger block sizes and more aggressive parameter settings.

6.3. Divisive Clustering for Compression

Figure 16 presents the results of applying the Divisive clustering method to compress and reconstruct an image. Starting with a block size of 2x2, the images exhibit high SSIM values, close to 1, across different cluster sizes. This indicates that the Divisive method is able to preserve the structural similarity of the image well, even when the number of clusters increases from 31 to 255. However, as the number of clusters increases, the CR decreases, which is expected since a higher number of clusters typically requires more data to represent the image. For instance, with 31 clusters, the CR is 14.22, while with 255 clusters, it drops to 6.58. The BPP also increases with the number of clusters, reflecting the trade-off between compression and quality. Despite the increased BPP, the SSIM remains high, suggesting that the Divisive method is efficient in maintaining image quality at smaller block sizes.

When the block size is increased to 4x4, the CR improves significantly, reaching as high as 49.64 with 31 clusters, which is nearly three times higher than the CR for the 2x2 block size with the same number of clusters. This indicates that the Divisive method becomes more effective in compressing the image as the block size increases. However, there is a slight reduction in SSIM, especially when the number of clusters is increased. For instance, with 255 clusters, the SSIM drops to 0.996, still high but slightly lower than the smaller block sizes. The BPP remains low, which indicates that the larger block size allows for more efficient compression without a significant loss in quality.

At an 8x8 block size, the trend of improving CR continues, with the highest CR reaching 93.01 for 31 clusters. This is an impressive result, showing that the Divisive method is particularly well-suited for compressing images with larger block sizes. However, the SSIM begins to show more noticeable reductions, particularly as the number of clusters increases. The SSIM drops to 0.991 with 255 clusters, which, while still high, indicates that some quality loss is occurring. The BPP remains low, demonstrating that the method is efficient in compressing the image at this block size.

Finally, at a 16x16 block size, the CR reaches its maximum of 48.66 with 31 clusters, but the SSIM drops to 0.952, indicating a more significant loss in image quality compared to smaller block sizes. With 255 clusters, the CR decreases to 23.74, and the SSIM improves slightly to 0.991, suggesting that increasing the number of clusters can help recover some of the lost image quality, albeit at the cost of lower compression efficiency. The BPP also increases, reflecting the need for more data to represent the larger block sizes with higher cluster counts.

In conclusion, the Divisive clustering method shows a strong ability to compress images effectively while maintaining high image quality, particularly at smaller block sizes. As the block size increases, the method becomes more efficient in terms of compression (higher CR), but this comes with a slight reduction in SSIM, especially when the number of clusters is high. The method demonstrates a good balance between CR, BPP, and SSIM, making it a viable option for applications where both compression efficiency and image quality are important. However, care should be taken when choosing the block size and the number of clusters to ensure that the desired balance between compression and quality is achieved.

6.4. DBSCAN and OPTICS Clustering for Compression

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 represent the results of image compression using two clustering techniques: DBSCAN and OPTICS. Both methods are designed to identify clusters of varying densities and can handle noise effectively, which makes them particularly suitable for applications where the underlying data distribution is not uniform. However, the results demonstrate distinct differences in how each method processes the image blocks, especially under varying parameter settings, such as eps for DBSCAN and xi for OPTICS, along with the

min_samples parameter common to both.

DBSCAN's performance across different block sizes and parameter configurations shows a stark contrast in image quality and compression metrics. At smaller block sizes (2x2), DBSCAN tends to find a very high number of clusters when the eps parameter is low, such as 0.1, and

min_samples is set to 1. This results in an extremely high cluster count (e.g., 46,142 clusters found), but this comes at the cost of poor CR and BPP, as seen in

Figure 17. The SSIM value remains high, indicating a good structural similarity, but the practical usability of such a high cluster count is questionable, as it results in high computational overhead and potentially overfitting the model to noise.

As the eps value increases (e.g., from 0.1 to 0.3) and min_samples rises, the number of clusters decreases significantly, which is accompanied by a drop in SSIM and an increase in CR and BPP. For instance, when eps is 0.3 and min_samples is 4, DBSCAN produces far fewer clusters, leading to much more compressed images but with significantly degraded quality, as evidenced by the low SSIM values. At larger block sizes (e.g., 4x4), DBSCAN's performance diminishes drastically, with the number of clusters dropping to nearly zero in some configurations. This results in almost no useful information being retained in the image, reflected in the SSIM dropping to zero, indicating a total loss of image quality.

OPTICS, which is similar to DBSCAN but provides a more nuanced approach to identifying clusters of varying densities, shows a different pattern in image processing. Like DBSCAN, the effectiveness of OPTICS is highly dependent on its parameters (

xi and

min_samples).

xi complements

min_samples by further refining how clusters are separated based on density changes.

Figure 18 shows that, regardless of the block size, OPTICS identifies a very small number of clusters (often just 1), especially when

xi is set to 0.3 and

min_samples is varied. This leads to extremely high CR and very low BPP, but at the cost of significant image distortion and loss, as seen in the brownish, almost entirely abstract images produced.

One notable observation is that OPTICS tends to retain minimal useful image information even when identifying a single cluster, leading to highly compressed images with very high CR but nearly zero SSIM. This suggests that OPTICS, under these settings, compresses the image to the point of obliterating its original structure, making it less suitable for tasks where preserving image quality is essential.

When comparing DBSCAN and OPTICS, it becomes clear that while both methods aim to find clusters in data, their behavior under similar parameter settings leads to vastly different results. DBSCAN's flexibility in finding a large number of small clusters can either be an advantage or a hindrance depending on the parameter configuration, whereas OPTICS, in this particular case, consistently produces fewer clusters with more significant compression but at the cost of image quality. For instance, both techniques perform poorly with larger block sizes, but DBSCAN's sensitivity to eps and min_samples allows for more granular control over the number of clusters and the resulting image quality. On the other hand, OPTICS, while theoretically offering advantages in handling varying densities, does not seem to leverage these advantages effectively in this context, leading to overly aggressive compression. The images produced by DBSCAN with lower eps values and small min_samples show that it can maintain a relatively high SSIM while achieving reasonable compression, although this comes with a high computational cost due to the large number of clusters. In contrast, OPTICS, even with different settings, fails to preserve the image structure, resulting in images that are visually unrecognizable.

6.5. Mean Shift Clustering for Compression

Figure 19 presents the results of compressing an image using the Mean Shift clustering algorithm with varying block sizes and bandwidth parameters. In the first row of the figure, the block size is set to 2x2 pixels, and the results for different bandwidth values (0.1, 0.3, 1, and 2) are displayed. When the bandwidth is set to 0.1, the algorithm identifies 46,142 clusters, resulting in a high CR of 1.36 and a BPP of 17.61. The SSIM value, which indicates the structural similarity between the original and compressed image, remains at 1.000, suggesting perfect reconstruction.

As the bandwidth increases to 0.3, the number of clusters remains the same at 46,142, but there is no significant change in CR, BPP, or SSIM, indicating that a small change in bandwidth does not significantly affect the results for this block size.

When the bandwidth increases to 1, the number of clusters found decreases significantly to 30,598. This reduction in clusters is reflected in a slight increase in CR to 1.50 and a decrease in BPP to 16.05. The SSIM remains perfect at 1.0, indicating that the image quality is still maintained despite the reduction in clusters.

Further increasing the bandwidth to 2 results in a more noticeable reduction in the number of clusters to 14,686. This leads to a more substantial improvement in the compression ratio, which increases to 2.12, and a further reduction in BPP to 11.33. Again, the SSIM remains at 1.000, showing that the structural quality of the image is preserved even with a higher level of compression.

In the second row, the block size is increased to 4x4 pixels, and the impact of different bandwidth values is analyzed. For a bandwidth of 0.1, the algorithm identifies 16,261 clusters. The CR and BPP are slightly better than the 2x2 block size, with a CR of 1.48 and BPP of 16.21, and the SSIM remains perfect at 1.000.

Increasing the bandwidth to 0.3 results in a marginal decrease in the number of clusters to 16,242, with the CR and BPP remaining almost the same as before. This suggests that the Mean Shift algorithm's sensitivity to bandwidth is relatively low for this particular block size and image.

With a bandwidth of 1, the number of clusters remains at 16,261, with no change in CR, BPP, or SSIM compared to the lower bandwidth settings. This implies that the algorithm has reached a level of stability where changes in bandwidth do not significantly impact the clustering outcome or compression efficiency.

When the bandwidth is increased to 2, the number of clusters slightly decreases to 16,042. However, this reduction has minimal impact on the CR and BPP, which stay at 1.49 and 16.16, respectively. The SSIM remains perfect, indicating that the image quality is not compromised even with a moderate bandwidth.

Comparing the results across different block sizes and bandwidth settings, it is evident that Mean Shift is highly sensitive to the bandwidth parameter, particularly when the block size is small (2x2). The algorithm tends to identify a very high number of clusters when the bandwidth is small, leading to lower compression ratios and higher bits per pixel. However, the image quality remains high, as indicated by the perfect SSIM scores.

As the bandwidth increases, the number of clusters decreases significantly, resulting in higher compression ratios and lower bits per pixel, without compromising the image quality. This trend is more pronounced at smaller block sizes, where the impact of bandwidth on the number of clusters and compression efficiency is more evident.

At larger block sizes (4x4), the impact of bandwidth on the algorithm's performance is less pronounced. The number of clusters identified by Mean Shift does not change significantly across different bandwidth settings, resulting in only minor variations in CR, BPP, and SSIM. This suggests that the Mean Shift algorithm becomes less sensitive to bandwidth as the block size increases, making it a more stable choice for image compression with larger block sizes.

6.6. GMM and BGMM Clustering for Compression

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 present the results of compressing an image using the GMM and BGMM clustering methods. Starting with the GMM results, we can observe how the block size impacts the compression performance and image quality. For smaller block sizes of 2x2, increasing the number of clusters from 31 to 255 shows a consistent decrease in CR from 12.63 to 5.88. This is expected, as more clusters should theoretically capture finer details, reducing compression effectiveness but improving image quality, as indicated by the rise in SSIM values from 0.972 to 0.989. However, as block size increases to 4x4 and 8x8, the CR improves significantly. For example, with a 4x4 block size, CR increases from 36.76 to 17.98 as the number of clusters grows from 31 to 255. However, this comes with a trade-off in image quality, where SSIM values drop from 0.842 to 0.956 as block size increases, suggesting that larger blocks and more clusters lead to overfitting, capturing more noise and thus reducing SSIM.

In contrast, BGMM results show a slightly different trend. At a block size of 2x2, the CR decreases similarly to GMM when increasing clusters, but BGMM appears to provide slightly better SSIM values at the cost of a slightly higher BPP. For instance, at 2x2 block size, the SSIM values range from 0.974 to 0.982 across cluster settings, indicating that BGMM retains better structural similarity at the cost of higher BPP, which ranges from 1.99 to 2.78. However, as the block size increases to 4x4 and 8x8, BGMM seems to outperform GMM in retaining image quality, especially in SSIM values, which are relatively stable, though it still suffers from an increase in CR and BPP.

Interestingly, at a block size of 16x16, both methods show signs of overfitting, with CR values increasing dramatically while SSIM values tend to plateau or decrease slightly. The BPP values for both GMM and BGMM increase with block size, indicating that while more data is being captured, it may not contribute positively to perceived image quality, as reflected in SSIM values.

A key observation is that GMM exhibits more pronounced changes in image quality across different block sizes and cluster settings compared to BGMM. BGMM, due to its probabilistic nature, likely provides more stable but less extreme results, which may explain why it performs better in retaining SSIM but at a higher BPP and often slightly worse CR.

Overall, the results indicate that both GMM and BGMM are effective clustering methods for image compression, but their performance is highly dependent on block size and the number of clusters. BGMM tends to provide more consistent image quality but at a higher cost in BPP, while GMM offers more aggressive compression but may lead to more noticeable degradation in quality at higher block sizes and cluster counts.

6.7. CLIQUE Clustering for Compression

Figure 22 presents the results of the CLIQUE clustering method applied for image compression with varying grid sizes, ranging from 1 to 8.5. The block size used in all experiments is fixed at 2x2, and the grid size controls the number of clusters and consequently affects compression performance and quality.

For grid sizes 1.5 and 2.0, the algorithm identifies only 1 and 16 clusters, respectively. These settings result in poor visual quality, as evidenced by the low SSIM values (0.014 and 0.864, respectively) and the inability to retain structural details in the image. The CR values are exceptionally high (4572.59 and 59.10), but this comes at the cost of extreme data loss, as depicted by the highly distorted or gray images.

Increasing the grid size from 2.5 to 4.5 results in more clusters (81 to 256), which improves the image's visual quality. The SSIM steadily increases, reaching 0.956 at a grid size of 4.5, indicating a good retention of structural similarity compared to the original image. Correspondingly, the CR values drop significantly (32.84 to 22.15), reflecting a more balanced trade-off between compression and quality. The images become visually more acceptable as the grid size increases, with better preservation of object edges and colors.

At grid sizes 5.0 to 6.0, the number of clusters increases drastically (625 and 1296), resulting in improved image quality. The SSIM values rise further (0.972 to 0.981), indicating near-perfect structural similarity. The BPP also increases moderately (1.38 to 1.65), demonstrating a slight trade-off in compression efficiency. The images exhibit finer details, and color fidelity is well-preserved, making these grid sizes suitable for high-quality compression scenarios.

As the grid size increases from 6.5 to 8.5, the number of clusters grows exponentially (2401 to 4096). The SSIM approaches near-perfection (0.986 to 0.989), and the BPP increases significantly (1.92 to 2.04). These results reflect excellent image reconstruction quality with minimal perceptual differences from the original image. However, the CR values continue to decrease (12.53 to 11.74), highlighting the trade-off between compression efficiency and quality. These grid sizes are ideal for applications requiring minimal quality loss, even at the expense of reduced compression efficiency.

The performance of the CLIQUE method is highly dependent on the grid size, with a direct relationship between grid size and the number of clusters. Lower grid sizes result in fewer clusters, leading to higher compression ratios but significantly compromised image quality, as evidenced by low SSIM values and poor visual results. Medium grid sizes, such as 4.5 to 6.0, strike a balance between compression efficiency and image quality, maintaining good structural integrity while offering reasonable compression ratios. On the other hand, higher grid sizes (e.g., 6.5 to 8.5) generate more clusters, yielding near-perfect SSIM values and visually indistinguishable images from the original but at the cost of reduced compression efficiency.

6.8. Discussion

The evaluation of the nine clustering techniques highlights the diverse strengths and limitations of each method in the context of image compression. Each technique offers unique trade-offs between compression efficiency, image quality, and computational complexity, making them suitable for different applications depending on the specific requirements.

K-Means stands out as a robust and versatile method for image compression, demonstrating a good balance between compression efficiency and image quality across various block sizes and cluster configurations. Its ability to produce consistent results with high SSIM values and moderate compression ratios makes it a strong candidate for applications requiring both visual fidelity and reasonable storage savings. However, its performance diminishes slightly with larger block sizes, where fine-grained image details are lost, leading to visible artifacts.

BIRCH, on the other hand, struggles to balance compression and quality, particularly with larger block sizes and higher thresholds. Its tendency to lose structural similarity at higher parameter settings indicates its limitations in preserving critical image features. While BIRCH may excel in other data clustering contexts, its application in image compression appears less effective compared to other techniques.

Divisive Clustering showcases excellent adaptability, particularly with smaller block sizes, where it maintains high SSIM values and reasonable compression ratios. As the block size increases, it achieves impressive compression efficiency with only a slight compromise in image quality. Its hierarchical nature enables it to provide granular control over the clustering process, making it well-suited for scenarios requiring a balance between compression and quality.

Density-based methods like DBSCAN and OPTICS highlight the challenges of applying these techniques to image compression. DBSCAN's performance varies significantly with its parameters (eps and min_samples), often producing high SSIM values at the cost of computational overhead and impractical cluster counts. OPTICS, while theoretically advantageous for handling varying densities, shows limited effectiveness in this application, often leading to excessive compression at the expense of image structure. Both methods illustrate the importance of parameter tuning and the potential challenges of adapting density-based clustering for image compression.

Mean Shift emerges as a stable technique, particularly for smaller block sizes and lower bandwidth settings. Its non-parametric nature allows it to adapt well to the data, resulting in high SSIM values and moderate compression ratios. However, as block sizes increase, the sensitivity of Mean Shift to its bandwidth parameter diminishes, leading to less pronounced variations in results. This stability makes it an attractive option for applications where consistency across different settings is desirable.

GMM and BGMM provide complementary perspectives on probabilistic clustering for image compression. GMM demonstrates more pronounced changes in performance across block sizes and cluster counts, offering high compression ratios but at the cost of noticeable quality degradation for larger block sizes. In contrast, BGMM delivers more consistent image quality with slightly higher BPP, making it a reliable choice for scenarios prioritizing visual fidelity over extreme compression efficiency.

Finally, CLIQUE, a grid-based clustering method, demonstrates the importance of balancing grid size with block size to achieve optimal results. While smaller grid sizes lead to significant compression, they often produce highly distorted images. Medium grid sizes strike a balance, maintaining reasonable compression ratios and good image quality, whereas larger grid sizes yield near-perfect SSIM values at the expense of reduced compression efficiency. CLIQUE's grid-based approach offers a unique perspective, emphasizing the interplay between spatial granularity and compression performance.

In summary, the comparative analysis of these techniques underscores the necessity of selecting a clustering method tailored to the specific requirements of the application. Techniques like K-Means, Divisive Clustering, and BGMM excel in maintaining a balance between compression efficiency and image quality, making them suitable for general-purpose applications. Methods such as CLIQUE and Mean Shift provide specialized advantages, particularly when specific parameter configurations are carefully tuned. On the other hand, techniques like DBSCAN and OPTICS highlight the challenges of adapting density-based clustering to this domain, while BIRCH's limitations in this context emphasize the importance of evaluating clustering methods in their intended use cases.

7. Validation of Compression Results Using CID22 Benchmark Dataset

The CID22 dataset [

53] is a diverse collection of high-quality images specifically designed for evaluating image compression and other computer vision algorithms. It offers a wide range of visual content, including dynamic action scenes, intricate textures, vibrant colors, and varying levels of detail, making it an ideal choice for robust validation.

For this study, eight representative images were selected, as shown in

Figure 23, covering diverse categories such as sports, mechanical objects, food, landscapes, macro photography, artwork, and natural phenomena like cloud formations. This selection ensures comprehensive testing across different types of visual data, capturing various challenges like high-frequency details, smooth gradients, and complex patterns. The dataset's diversity allows for a thorough assessment of the clustering-based compression techniques, providing insights into their performance across real-world scenarios.

Figure 24 and

Table 4 show the results of compressing the benchmark images using the nine clustering techniques. K-Means consistently delivers a balanced performance across all image categories. For instance, in sports and vehicles, it achieves high CR values (22.20 and 27.05, respectively) while maintaining excellent SSIM values (0.993 and 0.994). This indicates its effectiveness in preserving structural details while achieving reasonable compression. However, for more intricate scenes such as macro photography, the CR increases to 30.58, suggesting its adaptability for detailed data. Overall, K-Means achieves a good balance between compression efficiency and image quality, making it versatile for a variety of image types.

BIRCH exhibits low performance in both CR and SSIM across all image types. For example, in food photography and macro photography, it achieves SSIM values of -0.004 and -0.032, respectively, with CR values of 1.67 and 3.39. These results indicate significant quality loss and inefficiency in compression. The method struggles to adapt to the complexities of natural scenes or high-detail photography. BIRCH's weak performance suggests it may not be suitable for image compression tasks where quality retention is critical.

Divisive Clustering achieves high CR and SSIM values across most categories, particularly in sports and vehicles, with CR values of 23.45 and 28.34 and SSIM values of 0.993 and 0.994, respectively. These results show that the method preserves image quality effectively while achieving efficient compression. For macro photography, it performs similarly well, achieving an SSIM of 0.996. Divisive Clustering emerges as one of the top-performing techniques, maintaining a balance between efficiency and visual quality.

DBSCAN's performance is highly dependent on parameter settings and image content. It achieves perfect SSIM values (1.0) for several categories, such as food photography and vehicles, but at the cost of extremely low CR values (e.g., 2.77 for macro photography). This indicates over-segmentation, leading to inefficiencies in practical compression. In outdoor scenes and artwork, the method shows reduced CR values but still retains high SSIM, demonstrating its adaptability for specific types of data. However, its tendency to overfit or underperform depending on parameter tuning makes it less reliable overall.

OPTICS performs poorly in terms of compression efficiency and image quality. For most categories, such as sports and food photography, it achieves very high CR values (266.06 and 154.21) but with significantly degraded SSIM values (-0.113 and 0.530). The images reconstructed using OPTICS often exhibit severe distortions and fail to retain meaningful structural details. The method's performance suggests it is not well-suited for image compression tasks where preserving visual quality is important.

Mean Shift shows significant limitations in terms of compression efficiency. Despite achieving perfect SSIM values (1.0) across several categories (e.g., sports, food photography, and vehicles), its CR values are consistently low (e.g., 1.50 to 2.91). This indicates poor compression efficiency, making Mean Shift unsuitable for practical image compression tasks where achieving a high CR is essential. While it preserves image quality well, its limited efficiency renders it a less favorable choice for real-world applications.

GMM achieves a strong balance between compression and quality, particularly in vehicles and sports, with CR values of 24.44 and 21.02 and SSIM values of 0.978 and 0.941, respectively. However, it struggles slightly with macro photography, where SSIM drops to 0.933. While GMM performs well overall, its performance is slightly less consistent compared to Divisive Clustering or K-Means. Nonetheless, it remains a strong option for applications requiring good compression and quality balance.

BGMM exhibits stable performance across all categories, retaining higher SSIM values than GMM in most cases. For instance, in vehicles and macro photography, BGMM achieves SSIM values of 0.928 and 0.921, respectively. The CR values are also competitive, with a maximum of 25.33 in sports. However, BGMM tends to have slightly higher BPP compared to GMM, which may limit its efficiency for applications requiring aggressive compression. Its probabilistic nature ensures stable and reliable results across diverse image types.

CLIQUE emerges as a good performing method, combining high compression efficiency with excellent quality retention. In sports and vehicles, it achieves CR values of 14.39 and 14.40 and SSIM values of 0.992. In macro photography, it maintains a strong balance, achieving an SSIM of 0.963 while maintaining a reasonable CR of 29.29. CLIQUE adapts well to a wide range of image complexities and demonstrates consistent performance, making it a strong competitor to K-Means and Divisive Clustering.

In summary, K-Means, Divisive Clustering, and CLIQUE stand out as the most reliable methods for image compression, offering consistent performance across diverse image types. These methods effectively balance compression efficiency (high CR) and image quality (high SSIM), making them suitable for a wide range of applications. GMM and BGMM also provide good results but may require careful parameter tuning to achieve optimal performance. Mean Shift, despite its ability to retain image quality, is limited by poor compression efficiency, making it unsuitable for most compression scenarios. BIRCH, DBSCAN, and OPTICS exhibit significant limitations in either quality retention or compression efficiency, rendering them less favorable for practical applications.

Image compression is a crucial aspect of digital media management, enabling efficient storage, transmission, and accessibility of large-scale image data. With the growing demand for high-quality visual content in applications ranging from healthcare to entertainment, the development of effective compression methods is more important than ever. Clustering techniques offer a promising approach to image compression by grouping pixel data based on similarity, allowing for reduced storage requirements while maintaining structural fidelity. In this paper, we systematically evaluated nine clustering techniques—K-Means, BIRCH, Divisive Clustering, DBSCAN, OPTICS, Mean Shift, GMM, BGMM, and CLIQUE—for their performance in compressing images.

The findings highlight the versatility and efficacy of clustering-based approaches, with K-Means, Divisive Clustering, and CLIQUE emerging as the most reliable methods. K-Means demonstrated exceptional adaptability, balancing compression efficiency and image quality, making it a go-to technique for various image types and complexities. Divisive Clustering, with its hierarchical methodology, proved adept at preserving structural integrity while achieving substantial compression, particularly for larger block sizes. CLIQUE, leveraging its grid-based strategy, offered a unique combination of high CR and SSIM values, placing it as a strong contender alongside K-Means and Divisive Clustering. While GMM and BGMM were effective in retaining structural details, their compression efficiency was slightly lower than the top-performing techniques. Mean Shift preserved image quality but suffered from low CR, limiting its practicality. Techniques like BIRCH, DBSCAN, and OPTICS struggled to balance compression and quality, often yielding distorted images or suboptimal CR values.

Building on the findings of this paper, future research can explore several avenues to further enhance clustering-based image compression. One promising direction is the development of hybrid clustering techniques that integrate the strengths of multiple methods. For example, combining the adaptability of K-Means with the density-awareness of CLIQUE or DBSCAN could produce more robust algorithms capable of balancing compression efficiency and quality effectively. Another promising area is the application of clustering-based techniques to video compression, where temporal consistency between frames adds complexity and opportunity. Developing approaches that exploit temporal redundancies could significantly enhance compression performance.