1. Introduction

The detection of small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) within cluttered visual scenes is a critical requirement for airspace security and military defense. Unlike standard object detection tasks, UAV detection poses unique challenges due to the diminutive size of targets in imagery, which can appear as just a few pixels or even single-pixel entities when observed from long distances. These targets are sparsely distributed across expansive backgrounds that may include sky, urban structures, forests, ground surfaces, and streets, leading to an extreme imbalance between target and non-target areas. The complex nature of these backgrounds, characterized by significant noise and low signal-to-clutter ratios (SCR), further complicates the task, making it easy for tiny UAVs to be overshadowed or missed entirely.

Traditional approaches [

1,

2,

3] to tiny UAV detection have primarily relied on physical countermeasures such as radar, radio frequency analysis, and acoustic methods. However, traditional radar systems show limited effectiveness in detecting small UAVs, especially in complex terrains and urban environments where numerous reflections and interferences occur. Radio frequency and acoustic detection systems, while typically low-cost and easy to deploy, are highly susceptible to electromagnetic interference and environmental noise in urban settings. Consequently, these limitations underscore the necessity for advanced solutions capable of addressing the intricacies of UAV detection.

Deep learning has emerged as a transformative force in computer vision, offering significant improvements over conventional techniques. Deep models possess the capability to adaptively learn features directly from data, thereby providing robustness against complex backgrounds. Nonetheless, current research [

4,

5,

6] often employs heavy models as baselines, which may not be suitable for embedded equipment due to computational constraints. Moreover, even with lightweight models, the specific demands of tiny UAV detection—such as precise localization and identification—may not be fully met.

To address these challenges, this paper presents the Enhanced Tiny UAV-target YOLOv6n Network (ET-YOLOv6n). Our approach incorporates several innovations in the Backbone, Neck, and Head of the network designed to enhance detection accuracy while maintaining a lightweight model architecture. Specifically, with YOLOv6n as our baseline, we introduce a C2f-Star Module in the Backbone to enhance the extraction of tiny target features. In the Neck, a Cross-Two-Layer BiFPN is proposed to integrate features across vertical and horizontal directions of the network graph. Additionally, an extra P2 Head layer boosts the prediction of extremely small objects. Experimental results demonstrate superior performance compared to existing YOLO-based methods, with reduced false alarms and increased precision, underscoring ET-YOLOv6n’s potential for practical application.

Our contributions can be summarized as follows:

We propose a novel C2f-Star Module in the Backbone, employing Star Operation to increase feature dimensions while reducing the number of parameters.

We introduce Cross-Two-Layer BiFPN for feature fusion in both vertical and horizontal directions, effectively incorporating semantic and geometric features and preventing information loss.

We add a P2 layer to improve the detection of minuscule UAV instances, enhancing the model’s ability to detect tiny UAV objects.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work in improvements of tiny target detection.

Section 3 outlines the proposed ET-YOLOv6n architecture.

Section 4 provides experimental results and analysis. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future work.

2. Related Work

2.1. Feature Pyramid Networks (FPN)

In the field of computer vision, constructing effective feature representations is crucial for improving the performance of object detection and recognition tasks. Traditional convolutional neural network (CNN) methods typically employ a single-scale feature extraction strategy, where input images are resized to a fixed scale, which limits the effectiveness of detecting objects at different scales [

7,

8].

To address this issue, researchers have proposed the concept of feature pyramids, aiming to enhance the multi-scale adaptability of models by generating a set of feature maps with varying resolutions [

9]. These feature maps can be achieved not only by directly downsampling the original image or utilizing outputs from different layers of the convolutional network but also by incorporating top-down pathways and lateral connections to fuse features from different levels [

10]. Specifically:

1) Semantic Information: Deeper feature maps cover larger receptive fields, capturing more complex patterns such as the overall shape, texture, or category-specific identifiers of objects. These high-level abstract features facilitate object category recognition [

11,

12].

2) Positional Information: Shallower feature maps tend to retain more local details and edge information, which aids in precisely localizing object positions and boundaries [

13,

14].

As a concrete implementation of the feature pyramid concept, Feature Pyramid Networks (FPN) introduce a top-down pathway and lateral connections, enabling each level to acquire both high-resolution detailed information and low-resolution semantic information [

9]. FPN enhances feature representation through the following mechanisms:

1) Top-Down Pathway: Allows information to be progressively propagated from higher-level feature maps to lower levels, thereby supplementing semantic information that may be lost in lower-level feature maps [

9,

15].

2) Lateral Connections: Combine feature maps of the same scale but from different levels through addition or concatenation, preserving finer details and providing rich spatial information [

9,

16].

This design ensures that feature maps at each scale possess both detailed localization capabilities and robust classification abilities, significantly improving performance in tasks such as object detection and semantic segmentation [

9,

17]. For instance, in object detection tasks, deep semantic features are required to identify object categories, while shallow positional information is necessary to accurately localize object bounding boxes [

8,

14].

In summary, feature pyramids and their variants have been widely adopted in various computer vision tasks, achieving remarkable success and becoming an indispensable component of modern computer vision systems, driving continuous advancements in the field [

9,

17]. The successful application of FPN underscores the importance of integrating semantic and positional information from different levels, providing valuable insights for future research [

15,

16].

2.2. Attention Mechanism

In the field of computer vision, particularly in object detection tasks, the application of attention mechanisms has significantly enhanced model performance [

18,

19]. Traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs) process images through fixed feature extraction methods, which struggle to effectively capture targets under varying scales and complex backgrounds [

7]. Attention mechanisms enable models to dynamically focus on the most relevant information, thereby improving detection accuracy and robustness [

20,

21].

2.2.1. Enhancing Feature Representation

The core idea of attention mechanisms is to mimic the human ability to selectively focus on specific parts of data, allocating more “attention” to certain regions rather than treating all inputs equally [

22]. This allows models to more effectively capture information that is most useful for the current task [

23]. In object detection, attention mechanisms are implemented through three key components: Query, Key, and Value. The Query is used to search for relevant information, the Key matches the Query to determine which regions require more attention, and the Value represents the information to be weighted and aggregated [

24,

25].

Spatial attention and channel attention mechanisms enhance the focus on different regions and feature channels, respectively [

26,

27]. Spatial attention enables models to adaptively adjust their focus on different regions of an image based on task requirements, such as enhancing high-resolution information in shallow feature maps for small object detection [

10]. Channel attention mechanisms learn weights for each feature channel, allowing the model to filter information across different feature dimensions, emphasizing features critical to the task while suppressing irrelevant noise [

20,

28].

When integrated with feature pyramid networks, attention mechanisms facilitate information exchange between feature maps of different scales, further improving multi-scale feature fusion [

9,

28]. Through top-down pathways and lateral connections, FPNs preserve positional information from shallow feature maps while enhancing semantic information from deeper layers [

12]. Attention mechanisms can dynamically adjust the contribution of feature maps at each level based on task requirements, ensuring optimal feature representation [

15,

20].

2.2.2. Improving Small Object Detection Performance

Attention mechanisms provide strong support for the challenging problem of small object detection [

29,

30]. Since small objects may become blurred or even invisible in low-resolution feature maps, attention mechanisms help models focus more precisely on these regions, improving detection accuracy [

31]. By enhancing spatial information in shallow feature maps and combining it with high-level semantic information, models can maintain high resolution while achieving stronger classification capabilities [

14,

32].

In summary, the application of attention mechanisms in object detection has not only improved the ability of models to detect targets under varying scales and complex backgrounds but has also driven continuous progress in the field through enhanced feature representation and optimized small object detection [

18,

19]. As research advances and technology evolves, attention mechanisms will continue to bring new breakthroughs to computer vision tasks [

24,

25].

2.3. StarNet

In recent years, as the scale of deep learning models continues to expand, the design of efficient and compact neural network architectures has become a research focus. In this context, element-wise multiplication (“the star operation”) has gradually garnered widespread attention as a simple yet powerful operation. Xu et al. [

33] systematically investigated the theoretical foundations and practical applications of the star operation. Through theoretical analysis, they demonstrated that the star operation can implicitly map inputs to high-dimensional, non-linear feature spaces, akin to kernel tricks in traditional machine learning(e.g., polynomial kernel functions [

33]). This implicit high-dimensional mapping allows the star operation to significantly enhance the expressive power of models while maintaining network compactness.

Building on this theoretical foundation, the authors propose StarNet, a network architecture characterized by its minimalistic design and high efficiency. By stacking multiple star operation modules, StarNet achieves the construction of implicit high-dimensional feature spaces without increasing the network width. Experimental results show that StarNet delivers outstanding performance on benchmark datasets such as ImageNet-1K, outperforming several state-of-the-art efficient models (e.g., MobileNetv3 [

34], EdgeViT [

35], FasterNet [

36]), while also demonstrating faster inference speeds on mobile devices and GPUs. The authors further investigated the application of the star operation in activation-free network architectures, demonstrating its capability to sustain high performance levels without the reliance on traditional activation functions. This finding suggests promising directions for the development of novel network designs in future research.

The study by Xu et al. [

33] establishes a robust theoretical framework for the star operation while substantiating its practical significance in the development of efficient neural network architectures. Their findings reveal that the star operation represents a novel methodology for constructing computationally efficient and structurally compact neural networks. Furthermore, this research delineates several promising avenues for future investigation, including but not limited to: the development of activation-free network architectures, the enhancement of self-attention mechanisms, and the optimization of coefficient distributions in implicit high-dimensional spaces.

3. Methodology

3.1. Overall Architecture

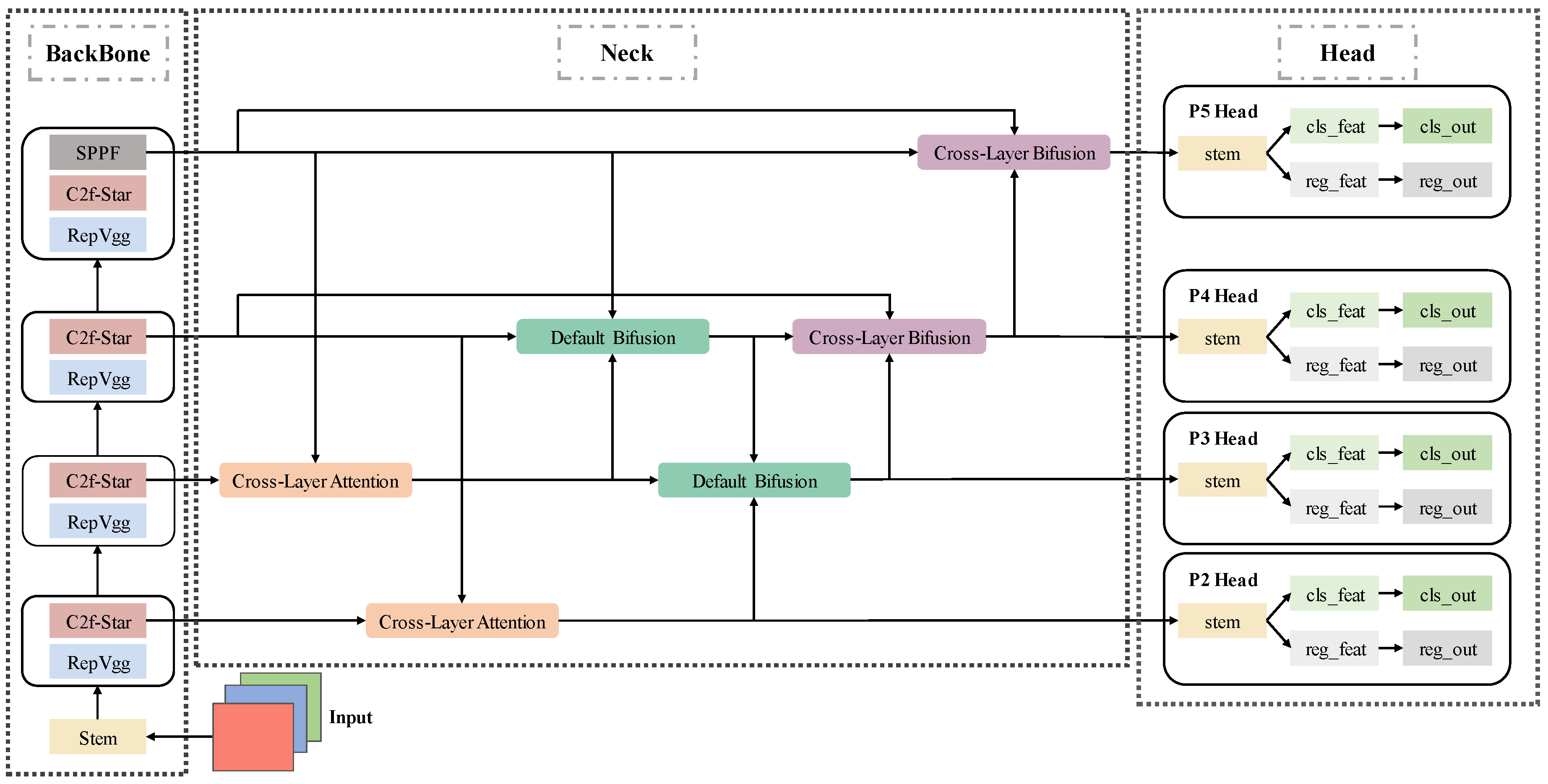

The workflow of the proposed method is illustrated in

Figure 1. An RGB image serves as input to a backbone network enhanced with the C2f-Star Module, wherein the traditional basic block within the C2f Module is replaced by the Star Operation Block. This configuration facilitates superior extraction of essential features from tiny objects, even against complex backgrounds. In the neck stage, we adopt an advanced Cross-Two-Level BiFPN (Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network) structure, which integrates multi-scale information more comprehensively than conventional BiFPN designs. Specifically, this enhanced architecture enables bidirectional feature fusion across layers separated by two levels through our proposed Cross-Layer Attention Module and Cross-Layer Bifusion Module. These modules ensure that features from different scales are effectively aggregated and refined, enhancing the representation of multi-scale information. Following the neck’s fusion process, the resulting feature maps—comprising the most detailed geometric information at stride 4 along with three higher-resolution feature maps—are fed into the head layer respectively. By incorporating a P2 Head, the model gains the capability to detect more tiny objects. The addition of the P2 Head not only enriches the feature extraction for tiny objects but also improves multi-scale representation, providing more detailed feature maps for detection tasks. These enhancements collectively contribute to significantly improved detection accuracy for tiny objects, demonstrating the architecture’s effectiveness in handling complex and diverse scenarios. The integration of advanced feature extraction, multi-scale aggregation, and specialized detection heads ensures that the proposed method can robustly identify small objects across various environments.

3.2. Enhancements to Backbone

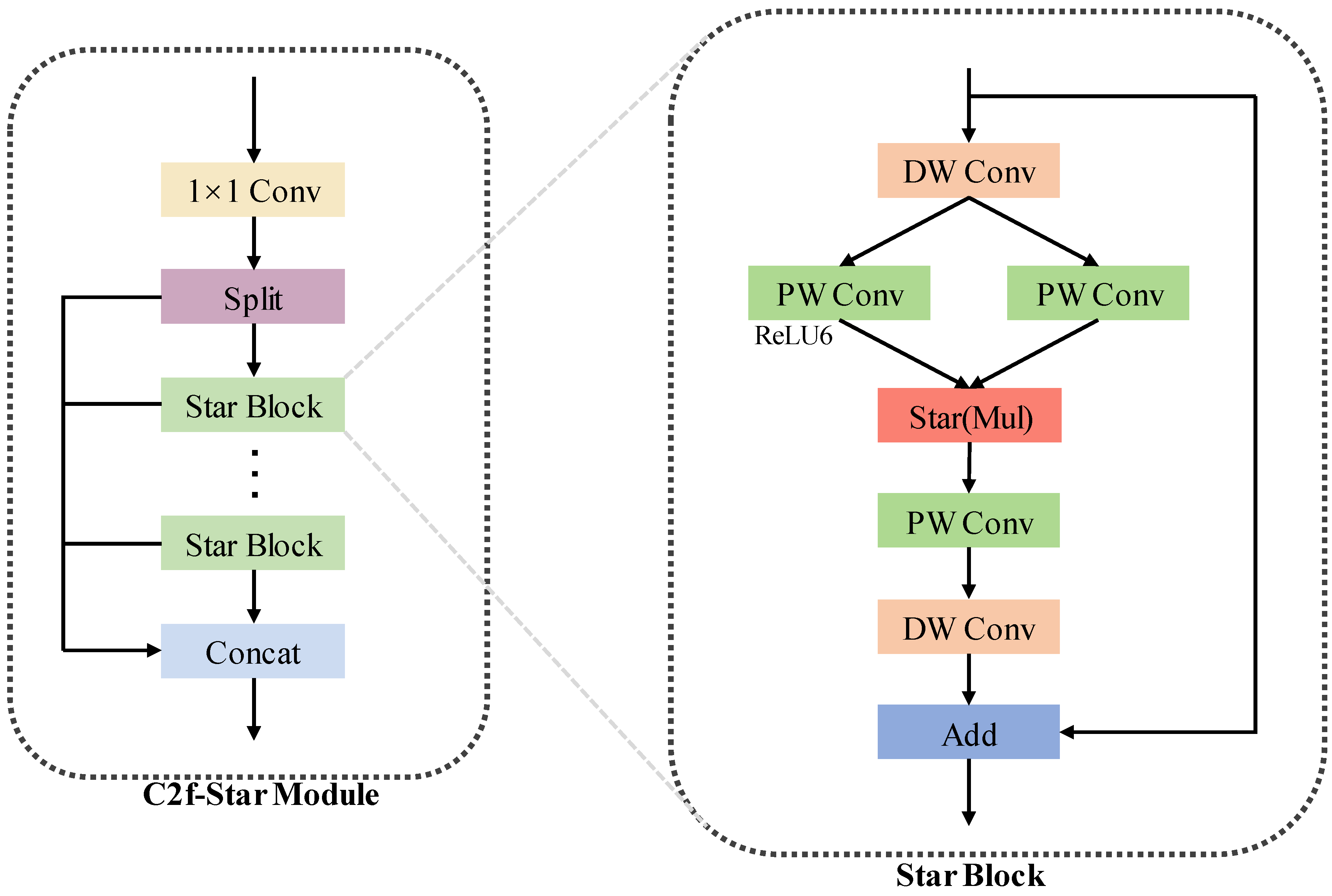

The backbone of YOLOv6n consists of a sequence of stem layers followed by repeated RepBlocks. While these straightforward RepBlocks account for a significant portion of YOLOv6n’s parameters, they are not well-suited for extracting features from tiny objects. To address this limitation, we introduce the C2f-Star Module. The C2f-Star Module retains the overall structure of the traditional C2f Module but replaces the basic block with a Star Operation Block. The Star Operation Block serves as a fundamental building block in the proposed module. As shown in

Figure 2, it integrates depthwise separable convolutions and multi-layer perceptron (MLP)-inspired transformations to enhance feature representation. Specifically, it applies a depthwise convolution followed by two parallel 1x1 convolutions that expand the feature space, combines their outputs using element-wise multiplication (Star Operation) after ReLU6 activation, and projects back to the original dimension via another 1x1 convolution. A final depthwise convolution is applied before adding the transformed features to the input through a residual connection, with an optional drop path for regularization. This design facilitates robust local and global feature extraction while maintaining computational efficiency.The Star Operation [

33] maps features into high-dimensional non-linear spaces, enhancing the model’s ability to detect tiny objects against complex backgrounds.

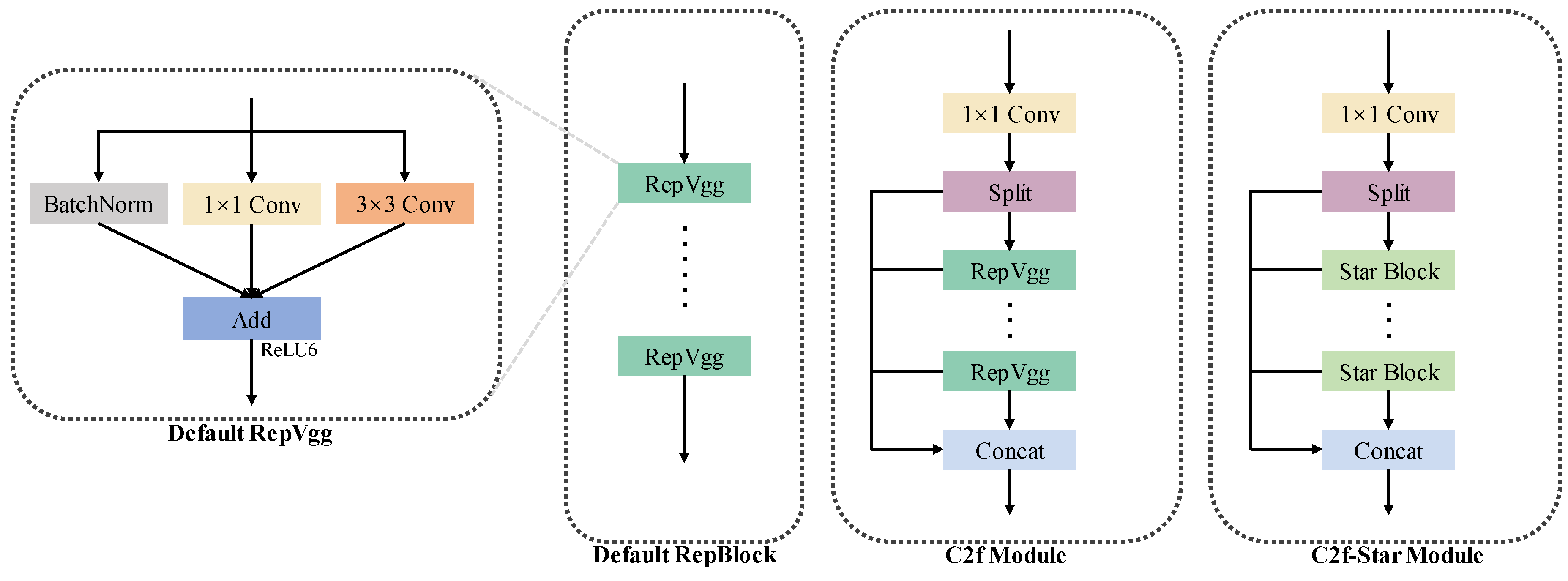

As illustrated in

Figure 3, the C2f structure is generally more advanced than the simple three-parallel-branch RepBlock design. Moreover, the Star Operation Block exhibits superior feature extraction capabilities compared to ordinary convolutions, making the C2f-Star Module significantly more effective than its C2f counterpart. This enhancement allows the C2f-Star Module to better capture intricate details of small objects, leading to improved detection accuracy without substantially increasing the model’s complexity. The proposed architecture thus strikes a balance between efficiency and performance, particularly in challenging scenarios involving tiny objects.

3.3. Enhancements to Neck

Tiny objects in images pose a significant challenge for object detection systems due to their limited representation in terms of both quantity and quality of features. This scarcity of effective features means that geometric information associated with these targets can easily become negligible during the feature fusion process. Despite YOLOv6n’s adoption of a BiFPN structure in the neck, which integrates features from upper-level, current-level, and lower-level layers, it still struggles with effectively combining geometric details with the semantic context from higher layers, resulting in suboptimal performance in detecting small objects within complex scenes.

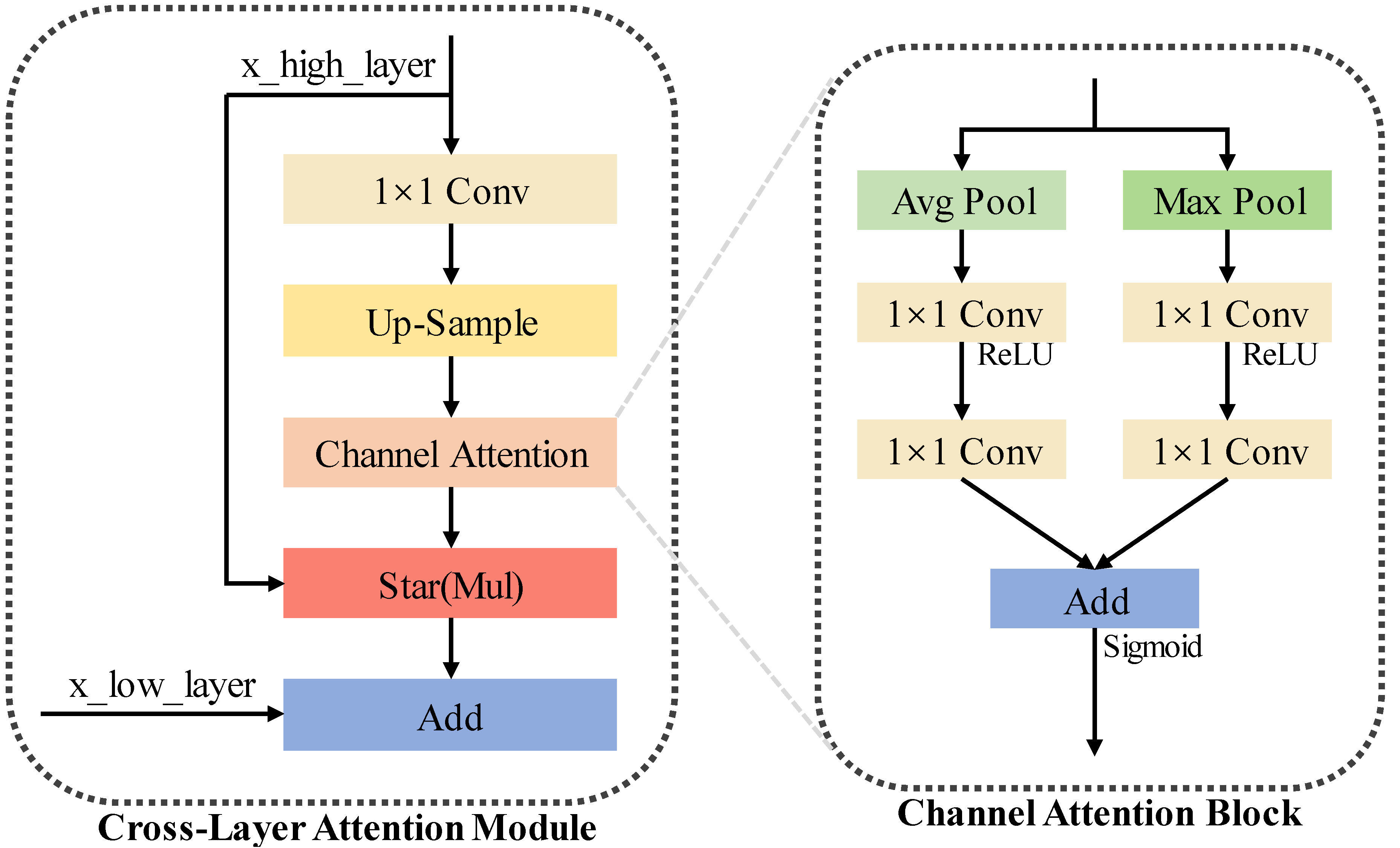

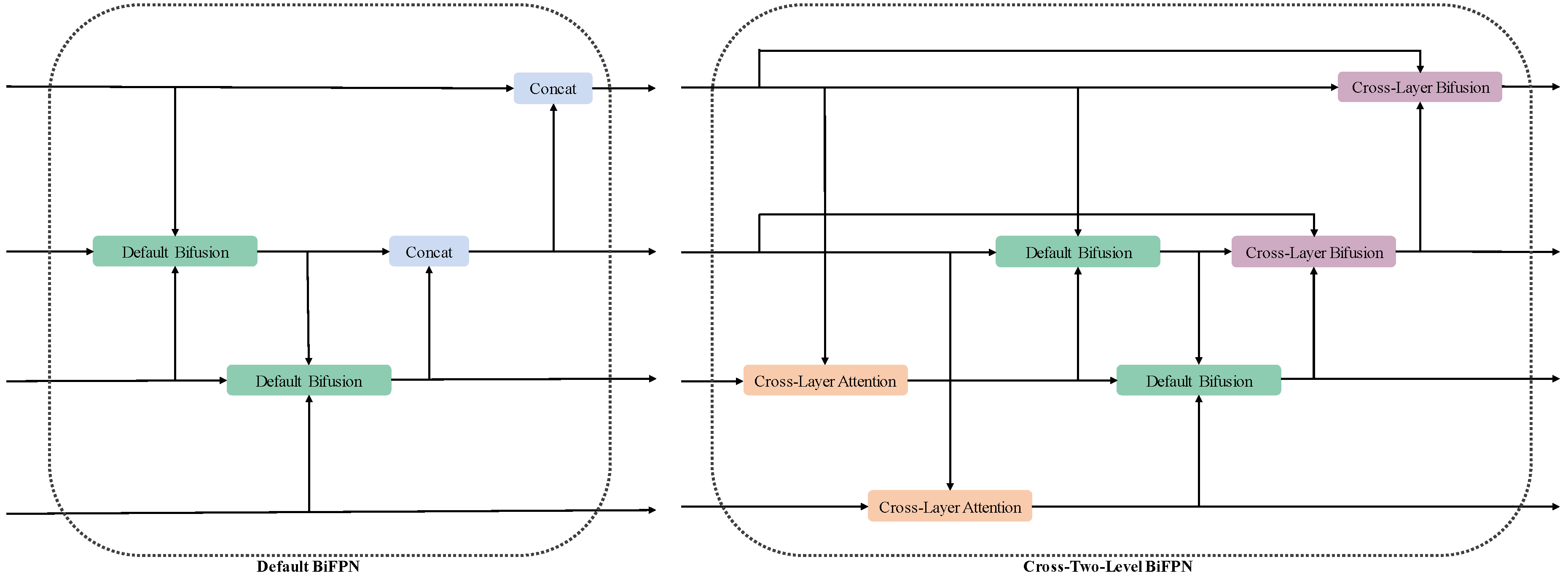

To address this issue, we introduce the Cross-Two-Level BiFPN structure, designed to generate attentions from semantic layers and then fuse with the geometric layers, enhancing feature fusion capabilities and improving the detection of tiny objects. As illustrated in

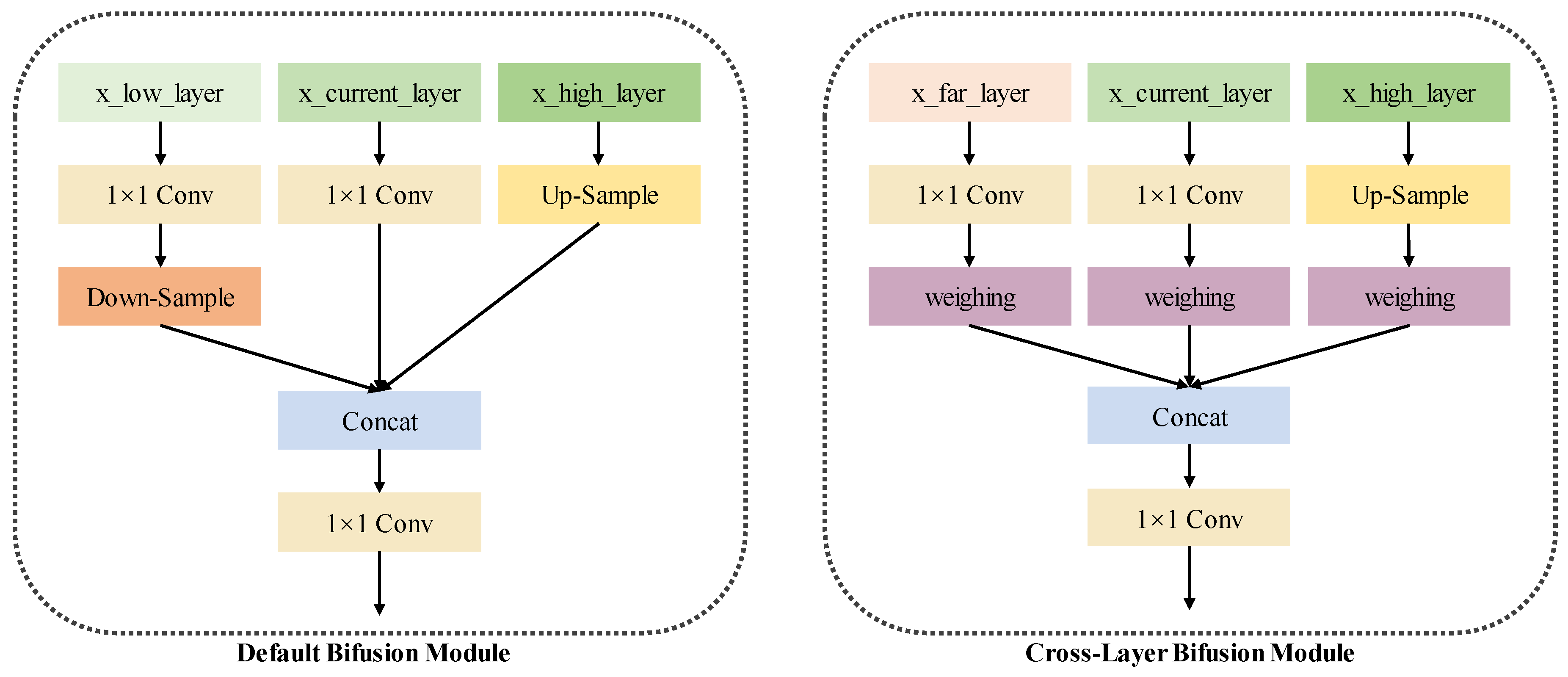

Figure 4, the Cross-Two-Level BiFPN extends the traditional BiFPN by incorporating features from two layers away in both vertical and horizontal directions within the network graph.

In the vertical direction, the Cross-Two-Level BiFPN facilitates the transfer and integration of high-level features to lower-level feature maps while incorporating channel-wise attention via Cross-Layer Attention Block. As shown in

Figure 5, the Cross-Layer Attention Block processes higher-resolution feature maps through depthwise convolutions to adjust their dimensionality to match those of lower-resolution maps, followed by bilinear upsampling to align spatial dimensions. Channel-wise attention mechanisms refine these upsampled feature maps by emphasizing important channels. The attended higher-resolution features are then element-wise multiplied with their attention maps and added to the lower-resolution maps, enriching them with high-level context. This design enhances the network’s ability to capture detailed information across different scales, improving feature representation and detection accuracy for tiny objects.

In the horizontal direction, we re-emphasize the original features by integrating input features into output features via concatenation and convolution. A weighted fusion mechanism, Cross-Layer Bifusion Module, is employed to integrate multi-scale feature maps. As shown in

Figure 6, the Cross-Layer Bifusion Module accepts three input feature maps with varying channel dimensions and initializes a learnable weight vector to assign adjustable importance factors to each input map during the fusion process. During the forward pass, normalized weights scale the respective input feature maps according to their learned importance. The scaled feature maps are concatenated along the channel dimension and passed through a 1x1 convolutional layer, reducing the total number of channels. This design allows for effective aggregation of multi-scale information while enabling the network to dynamically adjust the contribution of each scale, thereby enhancing overall feature representation and model performance.

Through these enhancements, the Cross-Two-Level BiFPN structure significantly improves the detection of tiny objects by effectively integrating geometric details with rich semantic context, leading to superior performance in complex scenarios.

3.4. Enhancements to Head

To further enhance the detection of tiny objects, we introduce an additional P2 layer into the detection head of our architecture. This augmentation is specifically designed to address the limitations encountered in detecting small targets that are often missed or inaccurately represented in standard architectures. Unlike YOLOv6n’s head that typically operate on three layers (P3, P4, P5), our architecture benefits from the enriched multi-scale representation provided by the inclusion of the P2 layer.

The integration of the P2 layer into the detection head is achieved by modifying the feature pyramid construction process to incorporate this finer-grained level. Specifically, the lowest-level input from the neck network is incorporated into the neck’s output, resulting in four outputs instead of the traditional three. The P2 layer receives features from this lowest-level input, allowing it to focus on the highest-resolution details, which are critical for detecting small objects. Similar to the higher levels, the P2 layer undergoes initial processing through a corresponding stem layer, enhancing its representation for subsequent tasks. The processed feature map is then branched into two streams: one for classification and the other for regression. Each stream is processed through specialized convolutional layers tailored to their respective tasks, culminating in refined classification and regression outputs.

While the addition of the P2 head increases computational requirements, it significantly improves the detection of tiny objects by leveraging earlier-stage features that contain richer spatial information. This enhancement addresses the inherent limitations of standard architectures, which may overlook smaller objects due to insufficient resolution at higher layers. By incorporating the P2 layer, our model can effectively capture detailed information across multiple scales, leading to more accurate and robust detection of small objects within complex scenes.

4. Experiment

This section outlines our experimental methodology, starting with the experimental setup, which encompasses the dataset, experimental environment, and evaluation metrics. Subsequently, to evaluate the innovations introduced in this paper, ablation study is conducted to prove the contributions of their individual effects. Furthermore, the ET-YOLOv6 model is compared with other mainstream YOLO series algorithms on the DUT Anti-UAV dataset to validate the effectiveness of the proposed enhancements.

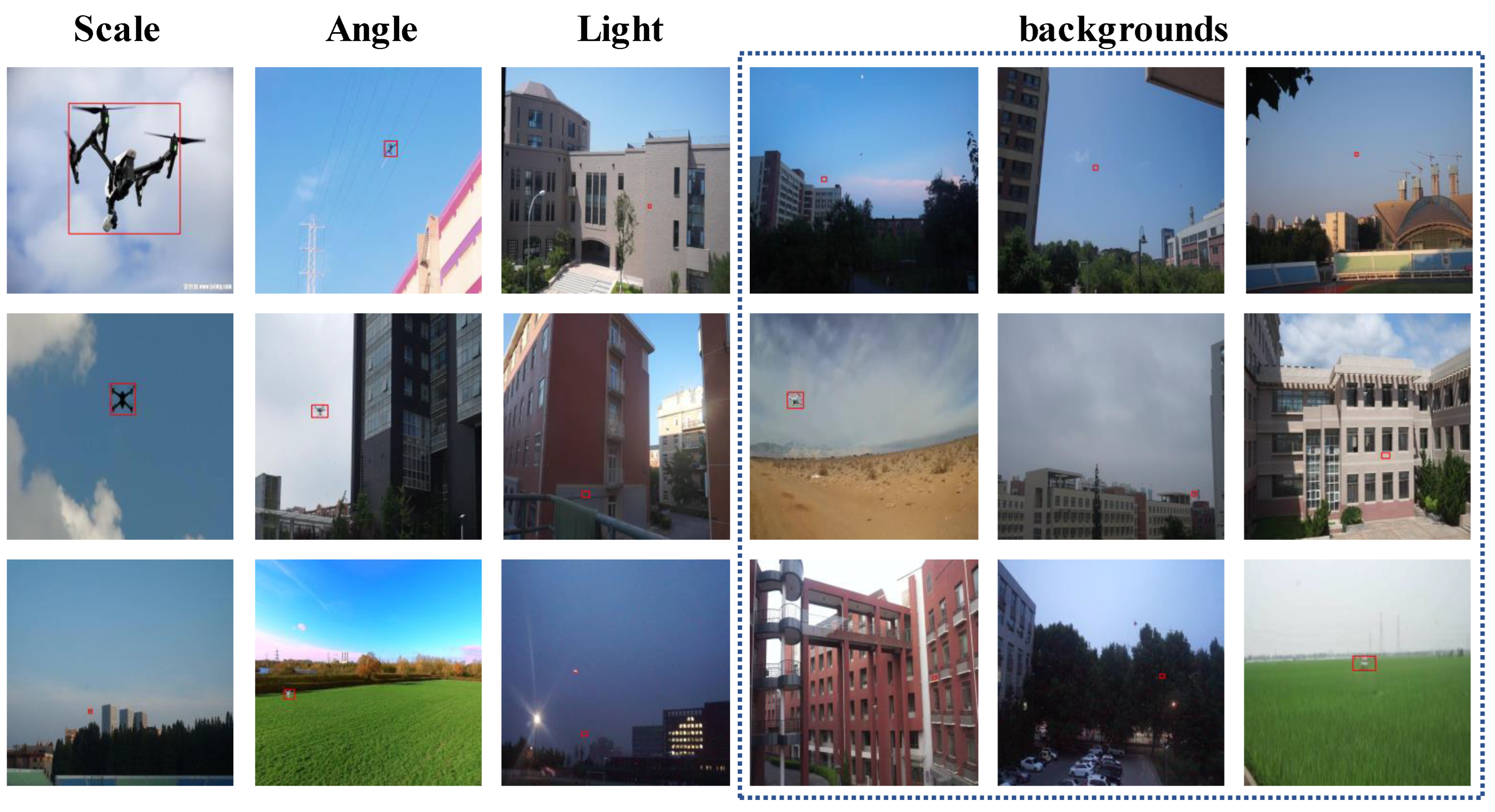

4.1. Dataset

To evaluate the performance of the improved algorithm (ET-YOLOv6) in detecting tiny unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), this study utilized the DUT Anti-UAV dataset for training and validation. This dataset comprises annotations for 10,109 UAV instances, characterized by a high degree of variability in scale, orientation, lighting conditions, and background complexity. The dataset is particularly challenging due to its inclusion of numerous small UAV targets embedded within intricate backgrounds, making it an ideal benchmark for assessing the robustness of detection algorithms on tiny objects.

Figure 7 provides a visual overview of the dataset’s attributes.

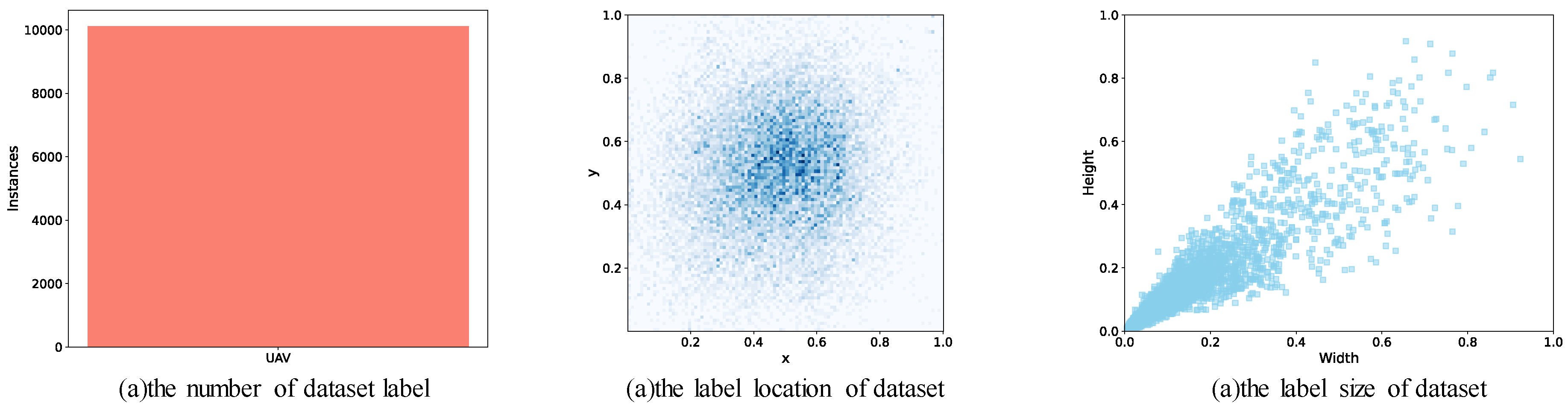

Figure 8 is an attribute visualization result of the dataset.

Figure 8a illustrates the distribution of labels within the dataset.

Figure 8b depicts the central coordinate positions of the annotated UAVs.

Figure 8c highlights the size distribution of the objects. These visualizations confirm that the dataset offers a diverse range of object sizes and placements, ensuring that it can adequately challenge and validate the capabilities of the ET-YOLOv6 algorithm in detecting tiny objects under various conditions. The comprehensive nature of the dataset supports thorough training and rigorous verification of the proposed method, thereby substantiating its effectiveness in real-world applications involving complex and varied scenarios.

4.2. Experiment Environment

Experiments were conducted on a server with Ubuntu 20.04.6 LTS, featuring an Intel® Xeon(R) Gold 6248 CPU @2.50GHz × 80 cores and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU with 128 GB GDDR6X memory. We used PyTorch (version 2.5.0) with CUDA 12.4 for GPU-accelerated training. Models were trained using mini-batch SGD over 300 epochs with a batch size of 32 images. All other parameters were set to YOLOs’ defaults.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

In the field of object detection, common evaluation metrics include precision, recall, Average Precision (AP), mean Average Precision (mAP), model parameters, Floating Point Operations per second (FLOPs), and inference time. These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of an algorithm’s performance in terms of accuracy and efficiency.

Given that mAP provides a more robust measure of accuracy compared to precision and recall alone, especially under varying levels of Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds, we opted for mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 as primary indicators of our algorithm’s effectiveness. Additionally, to evaluate the computational complexity and real-time performance, we also consider the number of model parameters, FLOPs, and inference time. This combination of metrics allows us to thoroughly assess both the accuracy and efficiency of our proposed method.

4.4. Ablation Experiments

Table 1 presents an ablation study of the proposed ET-YOLOv6n architecture on the DUT Anti-UAV dataset. The table compares the performance metrics of different improvement configurations of the model, highlighting the impact of individual components on the overall detection accuracy and computational efficiency. The baseline model is YOLOv6n, which serves as the starting point for our enhancements. We then evaluate the contributions of specific architectural improvements, including head enhancement, neck enhancement, backbone enhancement, and a combination of head, neck and backbone enhancements.

When only the Head is enhanced, the model achieves an increase in mAP@0.5 from 0.857 to 0.881 and mAP@0.5:0.95 from 0.549 to 0.572, indicating that refining the Head significantly improves the model’s detection accuracy. Enhancing only the Neck results in a more modest improvement, with mAP@0.5 increasing from 0.857 to 0.869 and mAP@0.5:0.95 from 0.549 to 0.556. Conversely, enhancing only the Backbone leads to a slight decrease in performance, with mAP@0.5 dropping from 0.857 to 0.842 and mAP@0.5:0.95 from 0.549 to 0.538. Integrating both Head and Neck enhancements, however, yields substantial improvements, with mAP@0.5 rising from 0.857 to 0.899 and mAP@0.5:0.95 from 0.549 to 0.582. This combination leverages the strengths of both components for superior overall performance.

Ultimately, the full ET-YOLOv6n model integrates all these enhancements, resulting in significant gains in detection accuracy compared to the baseline. Specifically, mAP@0.5 increases from 0.857 to 0.906 and mAP@0.5:0.95 from 0.549 to 0.588. Notably, the ET-YOLOv6n model achieves these performance gains while reducing the number of parameters and computational FLOPs by over 30% compared to the YOLOv6n baseline. These results underscore the effectiveness of our proposed enhancements in improving detection accuracy, particularly for small objects, while ensuring computational efficiency. The integrated design of ET-YOLOv6n thus represents a significant advancement in object detection architectures tailored for challenging datasets like DUT Anti-UAV.

4.5. Comparison with Other YOLO Algorithms

The YOLO series has consistently set benchmarks in object detection, achieving impressive results in both accuracy and efficiency. We compare our ET-YOLOv6n model against several prominent versions of YOLO, including YOLOv6, YOLOv7, YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, and YOLOv11, as detailed in

Table 2. Among these, YOLOv6-Tiny represents the latest lightweight variant of YOLOv6, optimized for resource-constrained environments. YOLOv8-v11 is one of the most recent algorithms in the YOLO family, offering robust performance across diverse detection scenarios. Despite its lightweight design, ET-YOLOv6n outperforms these models on the tiny UAV dataset, achieving superior detection accuracy and speed without increasing parameter count or computational cost.

To further highlight the advantages of ET-YOLOv6n, we also compare it with medium-sized variants of YOLO, which typically offer higher accuracy due to increased model complexity. As shown in

Table 2, ET-YOLOv6n surpasses YOLOv6m, YOLOv8m, and YOLOv10m in terms of detection accuracy and speed. Notably, compared to YOLOv9m and YOLOv11m, ET-YOLOv6n achieves comparable detection accuracy using significantly much fewer parameters and resources. Overall, ET-YOLOv6n demonstrates superior performance relative to other YOLO variants, validating the effectiveness and efficiency of our proposed improvements. This underscores the feasibility and reliability of our method, particularly for applications requiring high accuracy and low computational overhead.

5. Conclusion

We have addressed the significant challenges of detecting tiny Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in complex environments by introducing the Enhanced Tiny UAV-target YOLOv6n network (ET-YOLOv6n). This model builds upon the YOLOv6n baseline with targeted innovations to improve detection accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency. To enhance performance, we made several key modifications. In the backbone, we introduced the C2f-Star Module, which replaces conventional blocks with Star Operation Blocks to efficiently extract features from tiny targets while reducing computational overhead. This module increases feature dimensions and decreases parameters, leading to more robust feature representation. In the neck, we proposed a Cross-Two-Layer BiFPN that integrates features across both vertical and horizontal directions within the network graph. This design ensures robust multi-scale feature fusion, preventing information loss during downsampling and enhancing the detection of small objects. Finally, in the head, we added an extra P2 layer that leverages detailed geometric information from the P2 feature map to predict extremely small objects more accurately. These enhancements collectively improve the model’s ability to detect tiny UAVs without significantly increasing its complexity. Empirical evaluations on the DUT Anti-UAV dataset demonstrated that ET-YOLOv6n achieves competitive and often superior performance compared to existing YOLO-based approaches, including smaller and medium-sized models. Specifically, comparing with YOLOv6n as a baseline, ET-YOLOv6n improved mAP@0.5 from 0.857 to 0.906 and mAP@0.5:0.95 from 0.549 to 0.588, with over 30% fewer parameters and reduced computational requirements. These results underscore the effectiveness of our proposed method in real-world applications.

References

- Li, Y.; Fu, M.; Sun, H.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, Y. Radar-based UAV swarm surveillance based on a two-stage wave path difference estimation method. IEEE Sensors Journal 2022, 22, 4268–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Chee, J.H.; Feroskhan, M. Real-time multi-drone detection and tracking for pursuit-evasion with parameter search. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanström, F.; Englund, C.; Alonso-Fernandez, F. Real-time drone detection and tracking with visible, thermal and acoustic sensors. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR). IEEE; 2021; pp. 7265–7272. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Wang, X.; Liao, Z.; Chang, Y.; Yan, L. A real-time anti-distractor infrared UAV tracker with channel feature refinement module. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, pp.1240–1248.

- Xu, B.; Hou, R.; Bei, J.; Ren, T.; Wu, G. Jointly modeling association and motion cues for robust infrared UAV tracking. The Visual Computer, 2024, pp. 1–12.

- Fang, H.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Chang, Y.; Yan, L. Online infrared UAV target tracking with enhanced context-awareness and pixel-wise attention modulation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.B.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.B.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S.J. Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path Aggregation Network for Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.B. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the ICCV; 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.B.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.B.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Qi, J.; Jia, J. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2019; pp. 2881–2890. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.J.L.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic Image Segmentation With Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2018, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Identity Mappings in Deep Residual Networks. In Proceedings of the ECCV; 2017; pp. 630–645. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS; 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; Krähenbühl, P. Non-local Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2020; pp. 7794–7803. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Albanie, S.; Sun, G.; Wu, E. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the ECCV; 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Heess, N.; Graves, A.; Kavukcuoglu, K. Recurrent Models of Visual Attention. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS; 2014; pp. 2204–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Goodfellow, I.J.; Metaxas, D.; Odena, A. Self-Attention Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the ICML; 2019; pp. 7354–7363. [Google Scholar]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the ECCV; 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the ICLR; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Wu, Y.; Yao, Y. Dual Attention Network for Scene Segmentation. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2019; pp. 3146–3154. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, B.; Li, P.; Chen, Y. ECA-Net: Efficient Channel Attention for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2020; pp. 11531–11539. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Peng, Z.; Li, W.; Cui, L.; Xiao, T.; Wei, F.; Wen, S.; Li, H.; Luo, J. Transformer-based Feature Pyramid Network for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the ICCV; 2021; pp. 3575–3584. [Google Scholar]

- Kisantal, M.; Riess, C.; Wirkert, S.; Denzler, J. Augmentation for Small Object Detection. In Proceedings of the CVPR Workshops; 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Lu, X.; Shen, H.; Zhang, L. Small Object Detection in Optical Remote Sensing Images via Modified Faster R-CNN. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 829. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the ECCV; 2020; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.B.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the ICCV; 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Shawe-Taylor, J.; Cristianini, N. Kernel Methods for Pattern Analysis; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the ICCV; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J.; Bulat, A.; Tan, F.; Zhu, X.; Dudziak, L.; Li, H.; Tzimiropoulos, G.; Martinez, B. EdgeViTs: Competing Light-weight CNNs on Mobile Devices with Vision Transformers. In Proceedings of the ECCV; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; hong Kao, S.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.H.; Chan, S.H.G. Run, Don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPS for Faster Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2023. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).