1. Introduction

Autonomous vehicles (AVs), also known as self-driving vehicles, are at the forefront of technological innovation with the potential to transform and revolutionize transportation by improving road user safety, efficiency, accessibility, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions [

1,

2]. At the core of their operation lies the sophisticated capability to perceive, analyze, and respond to highly dynamic and complex driving environments in real time with minimal to no human intervention. AV’s perception system relies on the integration of advanced proprioceptive and exteroceptive sensors, robust processing power, complex machine learning (ML) algorithms, and decision-making systems to analyze and interpret complex traffic situations, navigate through unpredictable conditions, and make real-time critical driving decisions autonomously [

2]. In our previous research [

3], we investigated the architecture of an autonomous driving system from both functional and technical perspectives; highlighting the key components and subsystems that facilitate AVs to operate efficiently based on system design and operational capabilities, specifically in the perception stage of self-driving solutions.

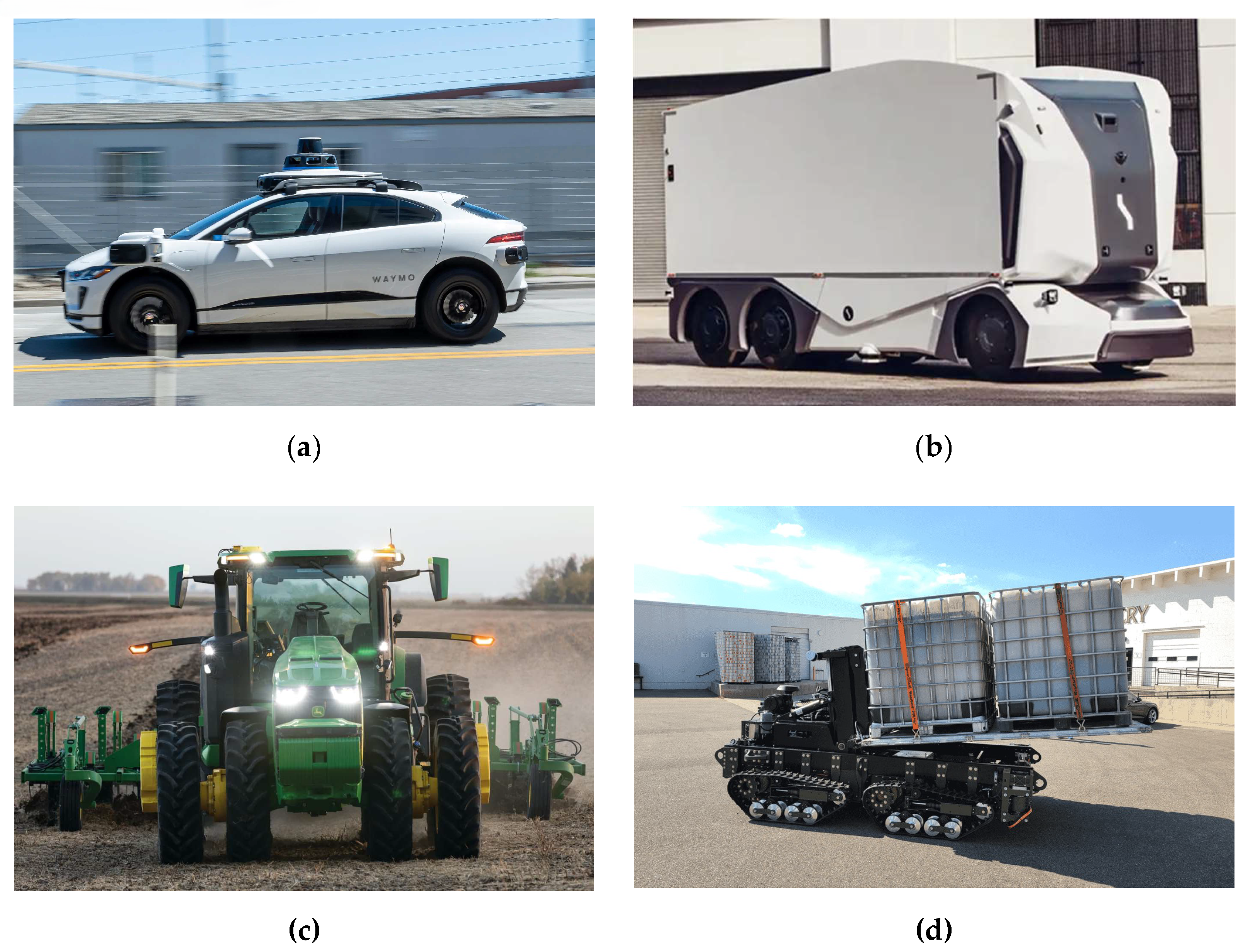

AVs are not limited to on-road applications such as highway driving and navigation or urban driving, nor to off-road environments in industries like agriculture, mining, and construction [

4,

5,

6]. It extends to a broader range of domains, including maritime settings, where AVs are applied to manage self-navigating vessels, automated container handling and logistic operations in container port terminals, et cetera; hence, improving the safety and efficiency of port activities [

7,

8]. Whether operating in structured urban settings with well-defined road networks, navigating unstructured and rugged off-road terrains, or coordinating day-to-day logistical tasks within dynamic maritime settings, AVs face diverse operational challenges that demand advanced solutions. All these challenges require efficient and robust multi-sensor fusion and decision-making algorithms to ensure effective and reliable performance.

In AVs, sensors play a pivotal role in perceiving its surroundings and localization of the vehicle within its environment to perform dynamic driving tasks such as obstacle detection and avoidance, path planning, environmental awareness, response to unexpected road situations, et cetera [

9,

10]. It involves real-time collection and interpretation of large volumes of data (or measurements) from multiple proprioceptive and exteroceptive sensors, including vision cameras, radar, Lidar, ultrasonic sensor, Global Positioning System (GPS), Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), et cetera.

Table 1 below provides a summary of the commonly adopted proprioceptive and exteroceptive sensors in an AV. It outlines the specific types of sensor that are frequently used in autonomous driving systems to enable robust perception and localization across various operational contexts [

11,

12].

However, the composition of the sensor suite, which refers to the collection of sensors that are integrated into an AV, can vary significantly based on the intended use cases and its specific operational demands. In addition, the specific operational environment of AVs – whether it is on-road, off-road, or in specialized industrial settings – affects the type and arrangement of the sensors that are required to facilitate the perception, localization, and decision-making processes in an autonomous driving system. For example, on-road AVs such as self-driving cars [

13] or trucks [

14] that operate predominantly on highways and within urban environments often rely heavily on a combination of vision cameras, radar, and Lidars to ensure high-resolution and 360-degree environmental mapping; which are vital in environments where dense traffic and high-speed motion are involved. These sensors must be able to detect and track moving objects, interpret traffic signals, and respond to unpredictable behaviors from other road users.

In contrast, off-road AVs such as autonomous tractor and tillage (agriculture), autonomous pallet loader (military and warehousing), automated rail mounted gantry (RMG) cranes (shipping yards), et cetera [

15,

16,

17] may employ different sensor configuration that incorporates robustness due to rugged environment, uneven surfaces, low-visibility conditions, or lack of clear infrastructures. In such cases, off-road AVs often incorporate specialized sensors like infrared cameras or thermal cameras to enhance visibility in dusty or low-light conditions [

18].

Figure 1 below presents a visual depiction of various examples of AVs specifically designed for both on-road and off-road applications. The imagery exemplifies the diversity present within the category of AVs, highlighting how different designs and functionalities are tailored to meet the unique requirements of different operational environments.

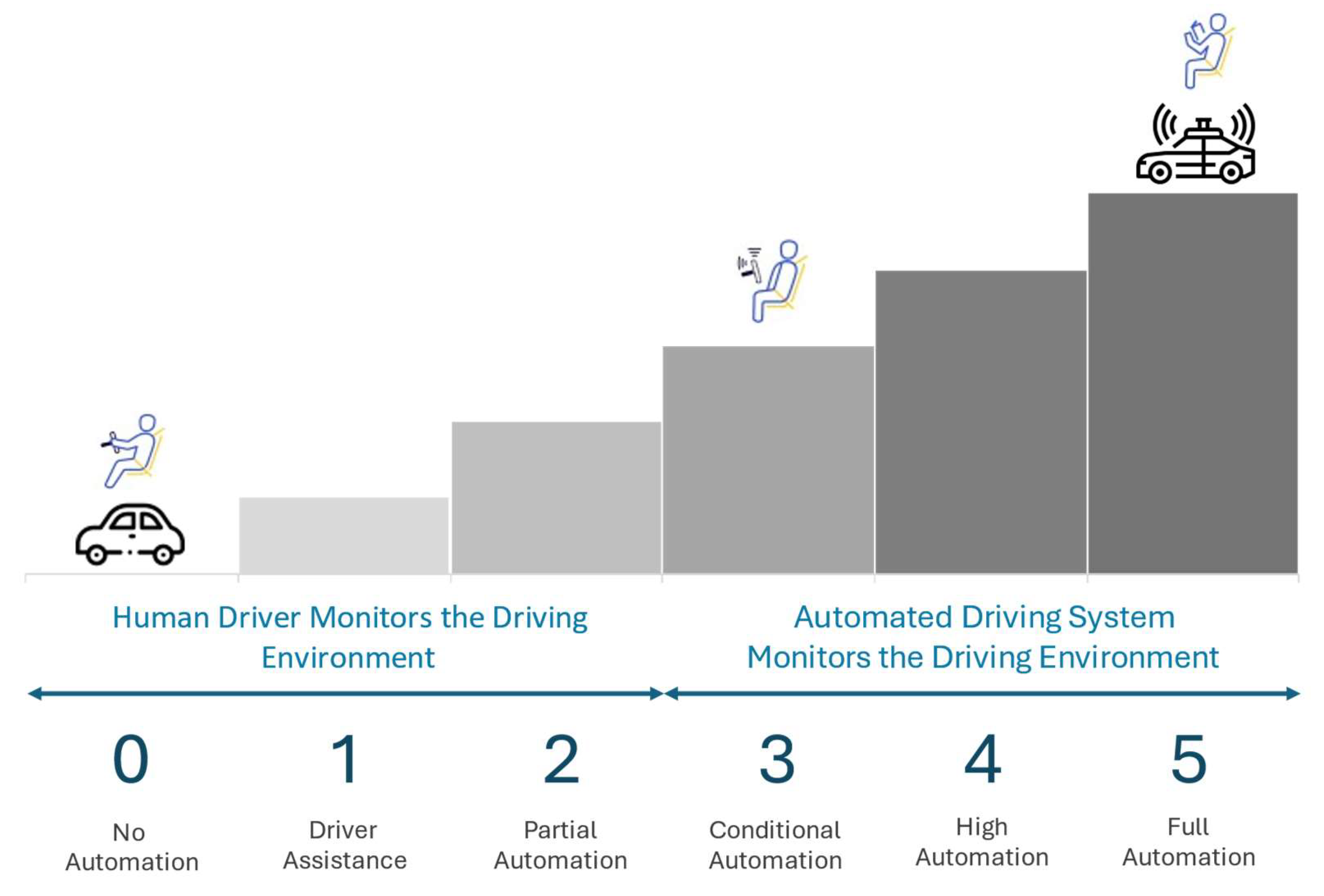

The Society of Automation Engineers (SAE) introduced a standardized guideline to eliminate terminological confusion used to describe the varying levels of vehicle automation. It aims to promote clearer communication across industries, enhance risk assessment during system design, support the development of safety and regulatory frameworks, and build public trust and understanding of AV technologies [

10,

20]. Hence, its initiative has led to the publication of the SAE J3016 standard in 2014, which clearly classifies the levels of driving automation ranging from Level 0 (no automation) to Level 5 (full automation) [

21], as illustrated in

Figure 2. Current automation driving technologies have yet to reach its full potential and have remained at Level 2 (partial automation) for several years [

10]. Nonetheless, it is important to highlight that Level 3 (conditional automation) automated driving systems are now being initiated into regular production [

22] and some manufacturers, such as Waymo’s commercial self-driving ride-sharing services [

23], claim to have built vehicles with autonomy that are equivalent to Level 4 (high automation) as described in the SAE J3016 standard. In both on-road and off-road applications, the adoption of this standardized classification supports more coherent development pathways for multi-sensor fusion and explainable artificial intelligence (XAI), as it provides a clearer understanding of the driving system’s intended level of autonomy, decision-making responsibilities, and operational limitations.

A shared characteristic of an autonomous driving system, applicable to both on-road and off-road applications, is their reliance on multi-sensor fusion, a method that involves integration data from multiple sensor types. This approach is essential for improving the overall perception and situational awareness of AVs, as it helps to address the limitations inherent in individual sensors operating in isolation and mitigate detection uncertainties. For instance, Lidar sensors are highly effective at providing precise, high-resolution depth information, they are susceptible to adverse weather conditions. In contrast, radar sensors are more capable of detecting objects through fog or rain but may offer lower spatial resolution [

11]. By integrating data from diverse sensor modalities such as exteroceptive sensors and proprioceptive sensors, multi-sensor fusion significantly enhances the accuracy, reliability, and robustness of the vehicle’s perception capabilities. Thus, such an approach enables AVs to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the surroundings, facilitating more effective navigation in complex and dynamic environments [

27,

28].

Nonetheless, as the complexity of autonomous driving systems increases, especially with the integration of multiple sensor modalities, the decision-making processes guided by complex deep learning (DL) and ML algorithms often lead to a significant lack of transparency. While these DL and ML models are highly effective at generalizing across a wide range of driving scenarios and are renowned for their powerful ability to model complex patterns through sophisticated data representation, their inner workings and its underlying decision-making logic often results in an inexplainable system [

29]. Such systems are concerning in safety-critical applications, such as AVs, where the consequences of erroneous or suboptimal decisions can be severe. For example, in scenarios involving novel conditions or sophisticated driving environments, the inability to understand how or why an autonomous system has made a particular decision can lead to significant risks, including system failures, accidents, or even the loss of human life [

30,

31]. Hence, it is important to integrate

explainability into the design of complex autonomous systems to enhance transparency, traceability, accountability, and trust among stakeholders [

32].

This paper builds upon and extends the research presented in our previous publication [

11], broadening the scope to deliver an in-depth analysis of the intersection between multi-sensor fusion and XAI in the context of AV systems. In this extended review study, we aim to systematically review state-of-the-art multi-sensor fusion techniques alongside emerging XAI methodologies that contribute to the development of more transparent and interpretable AV systems without compromising safety and perception accuracy.

Section 2 presents an overview of the latest advancements in multi-sensor fusion techniques and provides insight into how multi-sensor fusion methodologies are used to create a unified understanding of the vehicle’s surrounding environment. In addition, this section evaluates their respective strengths and weaknesses as well as the challenges associated in real-world autonomous driving applications.

Section 3 outlines the core principles and frameworks of XAI and presents an overview of emerging XAI techniques and tools that can be adopted to enhance the interpretability, transparency, and trustworthiness of an AV system. Besides, this section explores the role of XAI in AVs and emphasizes the critical importance of implementing explainability into the decision-making processes and its challenges to provide clear and interpretable insights into how and why specific driving decisions are made. Lastly,

Section 4 presents a summary overview of the key findings and insights presented throughout the research and highlights future research directions that could contribute to the development of more reliable, interpretable, and trustworthy autonomous driving systems.

2. Multi-Sensor Fusion in Autonomous Vehicles

In AV systems, multi-sensor fusion serves as a cornerstone process in constructing a precise and dependable model of the driving environment. It enables the AV to interpret, predict, and respond to diverse and complex road conditions without little to no human intervention. Unlike traditional vehicles, which rely exclusively on human drivers to perceive and respond to road conditions, AV systems employ a range of sensor types, including cameras, Lidar, radar, and ultrasonic sensors, that capture unique aspects of the driving environment for safe navigations and decision-making [

11].

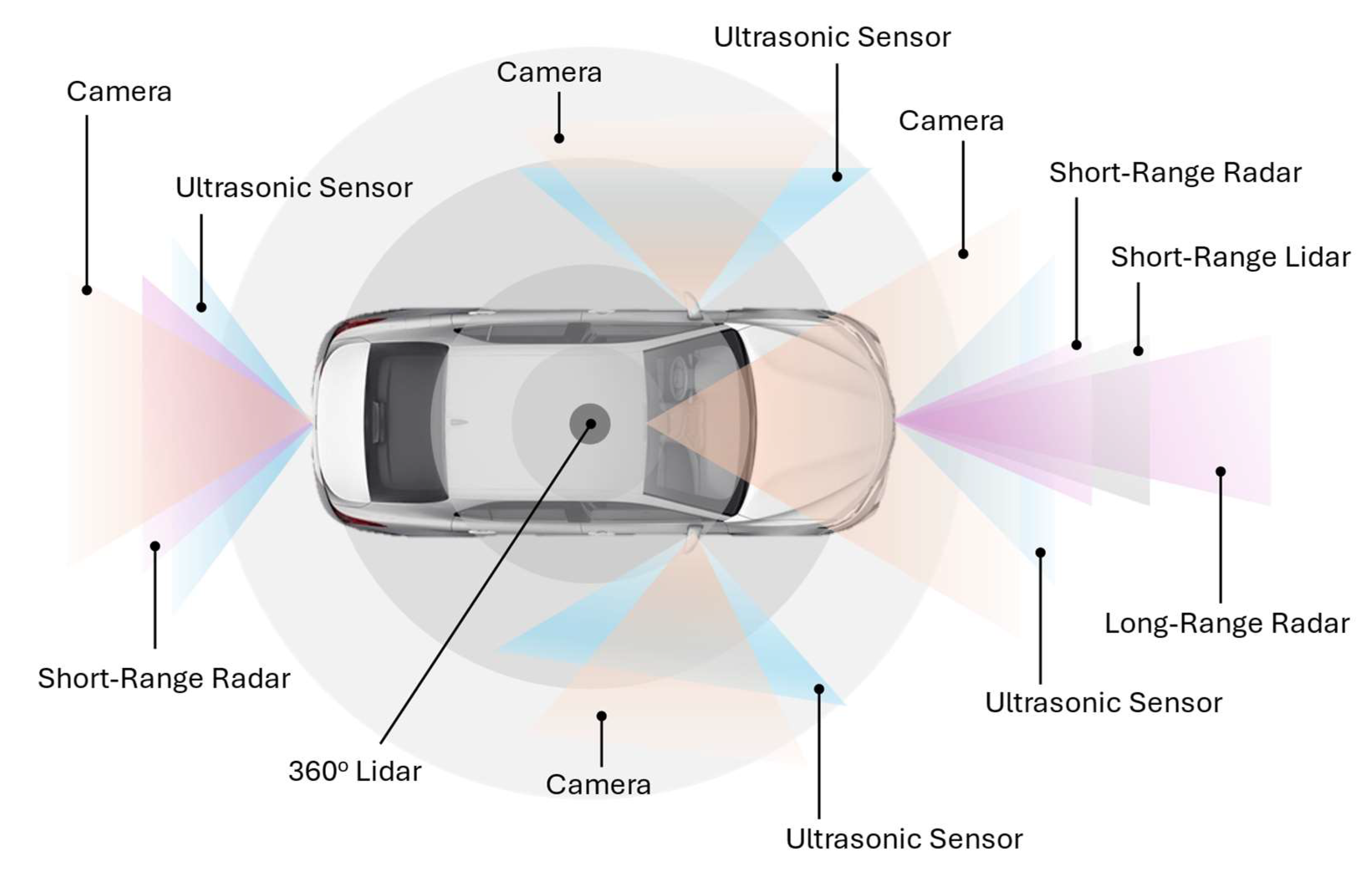

Figure 3 below provides an illustrative example of a standard sensor configuration for environment perception in AV systems. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the arrangement and integration of various sensors can differ significantly based on the specific application scenarios and operational requirements of the AV [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

However, each sensor type carries specific limitations that can compromise its reliability in isolation. For example, cameras deliver high-resolution images that are invaluable for capturing texture and color details and object recognition, but their effectiveness decreases in low light, glare, or adverse weather conditions. Lidar sensors generate detailed depth maps of the surrounding driving environment that enhance spatial awareness, but their performances can degrade under heavy fog or rainy weather conditions [

38,

39,

40]. Radar sensors, on the other hand, offer reliable distance and velocity measurements without weather condition constraints, but they lack the resolution needed to capture finer details or identify static objects with precision. Lastly, ultrasonic sensors complement the perception suite in AV systems by providing short-range object detection capabilities, which are critical for close-proximity maneuvers such as parking, yet their capabilities are limited in their short operational range and are not suitable for use in high-speed driving scenarios, where higher-resolution data and broader spatial awareness are indispensable [

11,

41,

42]. Therefore, integrating multiple sensor data streams using multi-sensor fusion techniques is imperative for overcoming the limitations that arise when sensors are employed independently. In addition, the multi-sensor fusion process significantly enhances the overall robustness and accuracy of perception in AV systems, which is vital for their performance in dynamic, unpredictable, and safety-critical driving scenarios.

Table 2 below presents a summary of advantages and limitations associated with exteroceptive sensors – cameras, Lidar, radar, and ultrasonic sensors [

43,

44]. It highlights the strengths and weaknesses of the sensors, offering valuable insights into their performance across different operational requirements and environmental or illumination conditions.

In the context of multi-sensor fusion, several distinct strategies were introduced and adopted to integrate data from multiple sensor modalities to improve the overall perception and decision-making capabilities of AV systems [

46]. These strategies can be broadly categorized into three primary approaches: (a)

low-level fusion, (b)

mid-level fusion, and (c)

high-level fusion. Each of these approaches presents a distinct technique for integrating sensor data, designed to optimize the trade-offs between data richness, real-time processing requirements, and computational efficiency. By strategically integrating data at different stages within the sensor data processing pipeline, these fusion techniques aim to address the inherent limitations and uncertainties of individual sensor modalities to create a more robust and resilient perception and navigation model in AV systems. This, in turn, allows AV systems to achieve a higher level of situational awareness, improving the reliability of decision-making and ensuring safer navigation, even in complex and challenging driving environments [

11,

46,

47,

48].

2.1. Multi-Sensor Fusion Approaches

2.1.1. Low-Level Fusion

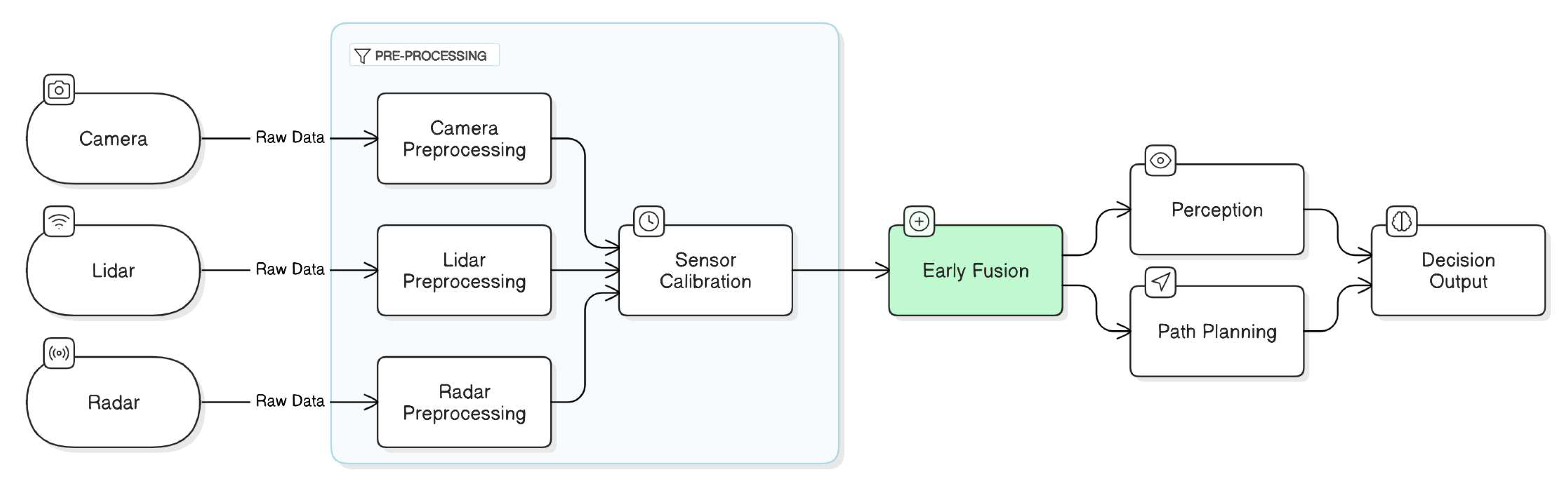

Low-Level Fusion (LLF), also known as data-level fusion or early fusion [

48,

49,

50], represents the most granular approach to integrating sensor data in AV systems, where data from multiple sensor types is integrated at the lowest abstraction level, before any significant preprocessing, filtering, or feature extraction occurs. In essence, the LLF approach to multi-sensor fusion utilizes raw features or unprocessed sensor inputs, such as raw radar reflections, camera pixel data, or Lidar point clouds, to create a comprehensive, high-resolution representation of the driving environment. One of the key advantages of LLF approach is its capability to retain the fine-grained information captured by each individual sensor, which maximizes the amount of information available for further analysis including small objects or minute changes in the driving scene. As a result, LLF approach plays an essential role in enhancing the precision and reliability of object detection and environmental awareness in AV’s perception system, specifically in dynamic or complex driving scenarios where capturing and preserving fine-grained information is critical for accurate decision-making and ensuring safe navigation [

51].

In AV systems, the LLF strategy is often employed in scenarios where high precision and fine-grained detail are indispensable, especially in tasks such as object detection, classification, and tracking. For instance, a recent study by [

52] demonstrated that integrating high-resolution camera images and Lidar 3D point clouds at the raw data level substantially improves the accuracy of image depth estimation. It involves projecting Lidar point clouds onto the image plane, otherwise known as sparse depth maps, and further refines into dense depth maps utilizing a depth completion method [

53] to transform camera features into a bird’s-eye view (BEV) space for long-range high-definition (HD) map generation; thereby improving the precision of object detection and overall spatial awareness. In addition, the study referenced in [

54] introduced a novel camera-radar fusion transformer framework to integrate spatial and contextual information from both the radar and camera sensors using an innovative Spatio-Contextual Fusion Transformer (SCFT) model and a Soft Polar Association (SPA) module. It leverages the complementary strengths of each sensor and the associated polar coordinates between radar points and vision-based object proposals for object detection, classification, and tracking. Such approach achieved state-of-the-art performance on the nuScenes test dataset [

55] and outperforming other existing camera-radar fusion methods in terms of accuracy and reliability.

Figure 4 below illustrates the concept and architecture of LLF approach to multi-sensor fusion. It visually demonstrates a high-level overview of the step-by-step fusion processes, emphasizing on how raw data streams from an array of sensor modalities are pre-processed including spatial-temporal calibration [

11], prior to being integrated into a unified dataset for further perception and navigation analysis [

56,

57]. While LLF is advantageous in providing a comprehensive, detailed view of the surrounding environment, it is not without its challenges and drawbacks. LLF requires high computational resources and memory bandwidth to manage and process large volumes of raw data from multiple sensors simultaneously, specifically at high resolutions. It leads to increased latency and may negatively impact the processing capabilities, which are not suitable in complex, dynamic environments where real-time decision-making is essential. Besides, LLF is susceptible to errors in the spatial-temporal calibration of the sensors operating at different frequencies. In safety-critical AV systems, the sensor misalignments can lead to inaccuracies in detecting objects and predicting object distances and trajectories; thus, compromising the reliability and safety of the AV systems. In addition, LLF approach exhibits limited flexibility in scenarios where a sensor fails or malfunctions, as the tightly coupled architecture relies heavily on synchronized inputs from all sensors. Thus, such dependencies reduce the robustness of the system and can pose significant challenges in maintaining the operational safety of the AV system in real-world conditions [

56,

57,

58].

2.1.2. Mid-Level Fusion

In contrast to LLF, which integrates raw data to build a comprehensive and detailed representation of the surrounding driving environment, Mid-Level Fusion (MLF) utilizes the extracted salient features from individual sensor types to construct a more refined and computationally efficient perception of the surroundings. MLF, otherwise known as feature level fusion, intermediate fusion [

57], or middle-fusion [

59], integrates the high-level features obtained from individual sensors, such as depth estimations – Lidar, motion trajectories – radar, object boundaries – camera, and et cetera, to develop a more abstract yet informative representation of the environment [

48]. MLF approach to multi-sensor fusion lies in its ability to balance perception accuracy with computation efficiency, especially in real-time decision-making scenarios. It offers a pragmatic solution for AV systems by optimizing the allocation of resources and reducing the computational complexity of sensor data processing while maintaining the precision of situational awareness for effective and safe navigation in dynamic, real-world driving conditions [

60].

MLF approach is often adopted to achieve a balance between high-accuracy perception and computational efficiency in real-time data processing for object detection, classification, and tracking. In their study, [

61] introduced

ContextualFusion, an environmental-based fusion network, that leverages domain-specific knowledge about the limitations of camera and Lidar sensors, as well as the contextual information about the environment to enhance the perception capabilities. It utilizes the MLF approach to integrate features extracted from the sensors and environmental contextual data, i.e., illumination conditions – daytime and night-time, and rainy weather condition to detect objects in adverse operating conditions, achieving state-of-the-art detection performance on the nuScenes dataset [

55] at night-time. In [

62], the scholars presented the concept of an end-to-end perception architecture that leverages the MLF strategy in its deep fusion network to create a shared representation of the surroundings. Its fusion network incorporates the features obtained from individual sensor encoders, as well as the temporal dimensions to develop a unified latent space that is sensitive to the nuances of spatial relationships and temporal dynamics for subsequent perception tasks, including object detection, localization, and mapping. By utilizing the unified latent space, the network allows interdependent learning across various perception tasks to minimize redundant data processing; hence, optimizing resource utilization and computational efficiency.

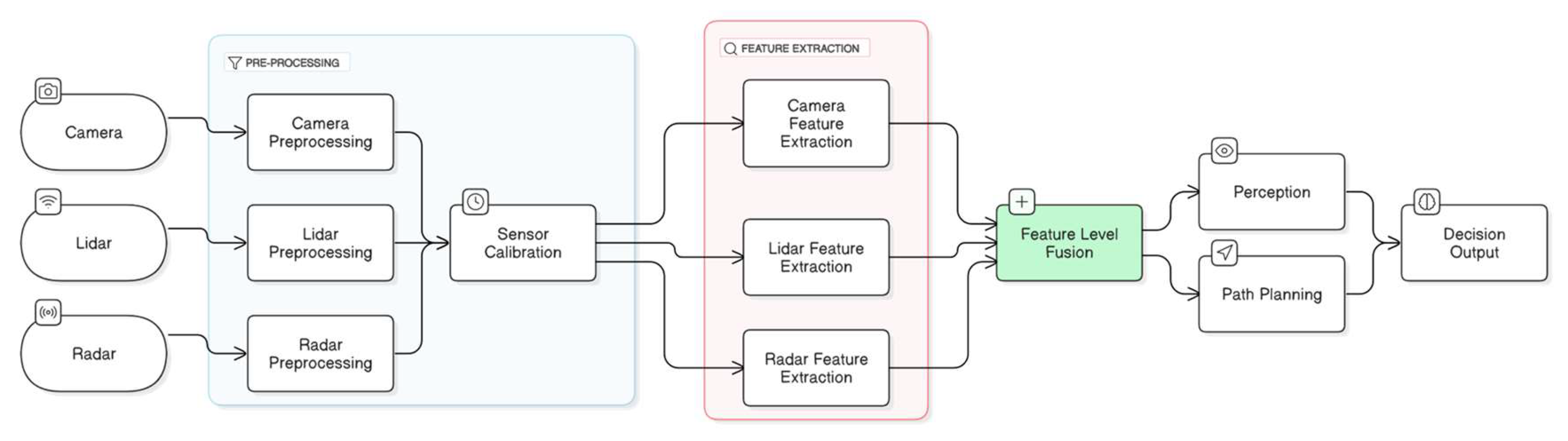

Figure 5 below depicts the concept and architecture of MLF approach to multi-sensor fusion. It illustrates a high-level overview of the sequential fusion processes, emphasizing on how distinct features are initially extracted from individual sensor types prior to being integrated into a shared feature space for subsequent perception and navigation analysis [

56,

57]. Although MLF offers significant benefits in optimizing resource utilization while maintaining high object detection accuracy, it also presents certain challenges and limitations. MLF requires robust feature extraction algorithms to accurately synthesize the relevant information from disparate sensor sources. It relies on precise feature extraction and is vulnerable to sensor failures, noise, and inconsistencies, which can lead to information loss and resulting in degraded performance in critical perception tasks [

48]. Additionally, MLF requires precise multi-sensor spatio-temporal calibration to ensure data consistency during the fusion process. It also requires substantial computational resources to integrate large feature subsets from multiple sensors, which can be challenging in real-time safety-critical systems due to concerns about data latency [

11]. Furthermore, as noted in [

63], the MLF strategy may not be adequate to support the realization of SAE Level 4 or 5 AVs, as it struggles to handle unexpected scenarios based on predefined feature sets and may fail to retain critical contextual information.

2.1.3. High-Level Fusion

High-Level Fusion (HLF), also referred to as decision-level fusion or late fusion [

57], represents the highest level of abstraction to integrating multi-sensor data in AV systems. In contrast to LLF and MLF, HLF incorporates individual sensor outputs or decision-making results to construct a comprehensive understanding of the environment. It focuses on integrating the final interpretations or outcomes derived from the analysis performed by individual sensors, such as, location coordinates, velocity vectors, motion trajectories, predicted bounding boxes, classifications of detected objects, et cetera, to establish a reliable, unified, and accurate informed decision [

59,

64]. One of the key benefits of HLF approach is its modular structure that allows seamless integration of new sensors or updates to existing multi-sensor fusion system without significant changes to the overall fusion framework. As a result, it can be easily adapted to incorporate additional sensing modalities or to accommodate multiple sensor configurations, thereby supporting the scalability of the autonomous driving system [

57]. Besides, HLF enhances computational efficiency by focusing on the integration of high-level decisions from individual sensor modalities, which significantly reduces computational complexity compared to raw sensor data, as the processed, abstracted information requires fewer resources, making it beneficial for low latency applications in AV [

65]. HLF also promotes robustness and fault tolerance due to its approach to sensor fusion, which allows the system to maintain effective operation when one or more sensors fail or provide erroneous data – no interdependence at the feature or raw data levels.

HLF approach is often adopted to optimize computational efficiency while maintaining effective decision-making capabilities and overall system performance, specifically in real-time, safety-critical applications such as autonomous driving. In their study, [

66] introduced a

Multi-modal Multi-class Late Fusion (MMLF) architecture, which integrates object-level information from various sensor modalities and quantifies the uncertainty associated with the classification results. It involves integrating bounding boxes (spatial locations of objects) from the detectors and a non-zero Intersection over Union (IoU) values to obtain multi-class features for uncertainty estimation. As a result, the integration leads to improved precision and reliability in object detection, achieving substantial performance improvements on the KITTI [

67] validation and test datasets. In [

68], the researchers presented a late fusion architecture that leverages

Deep Neural Network (DNN) models to detect pedestrian detection during night-time conditions by utilizing data inputs from RGB and thermal camera images. It involves integrating the outputs, i.e., bounding boxes and detection confidence scores, from individual detection models and applying a

Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) method [

69] to eliminate redundant detections of the same object and refine the final detection outputs. As a result, the architecture enhances the precision and reliability of pedestrian detection in night-time conditions while ensuring an optimal balance between detection accuracy and low response time during real-time inferencing.

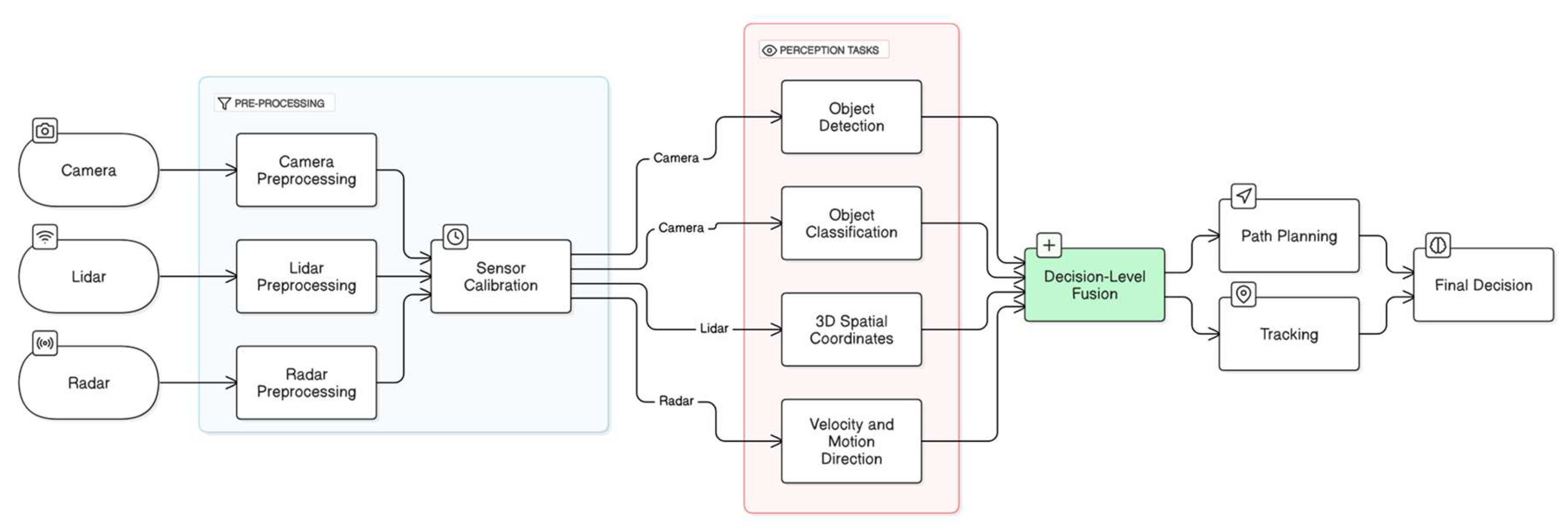

Figure 6 below demonstrates the concept of HLF approach to multi-sensor fusion. It visualizes the high-level overview of the HFL processes, where the outputs generated by individual sensor data analysis are integrated to achieve enhanced situational awareness and reliable informed decisions in dynamic driving scenarios [

56,

57]. While HLF strategy is advantageous in terms of its computational efficiency and modularity, it is not without its challenges and drawbacks. One notable drawback is the potential loss of detailed contextual information that is often available in raw or feature-level data. HLF may overlook the fine-grained details that are crucial for precise decision-making, especially in dynamic and complex driving environments. The omission of these details can result in erroneous or suboptimal decisions, which can negatively impact the overall performance and safety of the autonomous driving system [

59]. Besides, HLF approach relies significantly on the precision and reliability of each individual sensor’s interpretation of the surroundings. In other words, any inaccuracies, misclassifications, or failures in the data from a single sensor can propagate through the AV system, which can lead to misinterpretation of objects or incorrect assessments of driving conditions [

48].

From a computational perspective, sensor fusion can also be categorized into: (a)

centralized fusion, (b)

decentralized fusion, and (c)

distributed fusion. Each of these categories defines the architecture and the specific locus of where the fusion process occurs within the system [

70]. In centralized fusion, raw data from each individual sensor is transmitted to a central processing unit, where it is integrated to produce a cohesive and comprehensive representation of the surroundings. In other words, the central processor handles a range of critical tasks in autonomous driving, including data filtering, feature extraction, decision-making, and oversees system control functions, to ensure safe and efficient autonomous driving. In contrast to centralized fusion, decentralized fusion distributes the fusion process across multiple local nodes, where each sensor or subsystem independently processes its data and performs local fusion or analysis before transmitting the processed results to a central unit or other nodes for further integration. In distributed fusion, the concept of decentralization is further extended to allow each sensor or node to share intermediate or partially fusion results across the system without relying on a single central processing unit for final decision-making.

Table 3 below highlights the advantages and drawbacks of centralized fusion, decentralized fusion, and distributed fusion [

70,

71,

72,

73].

In summary, by strategically integrating sensor data at different stages of the multi-sensor processing pipeline, these multi-sensor fusion approaches aim to leverage the complementary strengths of diverse sensors and the architectural designs of the autonomous driving systems. As discussed, multi-sensor fusion can occur at both the

abstraction level, i.e., HLF, MLF, and LLF, and

computational level, i.e., centralized fusion, decentralized fusion, and distributed fusion. On the one hand, the sensor fusion approaches at the abstraction level dictate the timing of when data from individual sensors are integrated. In other words, it addresses the question of “when should the multi-sensor fusion occur?”. On the other hand, the fusion approaches at the computational level emphasis on the location of where the fusion process occurs to optimize system performance. In essence, it addresses the question of “where should the multi-sensor fusion occur?”. Nonetheless, it is vital for readers to learn that sensor fusion can also occur at the

competition level, which addresses the question of “what should the fusion do?” [

70,

72,

74] (detailed discussion of the fusion approaches at the competition level, i.e., competitive fusion, coordinated fusion, and complementary fusion is beyond the scope of this manuscript). Ultimately, selecting the most suitable sensor fusion approach depends on the specific use cases and requirements of the AV systems, including scalability, computational resources, fault tolerance, and real-time performance.

2.2. Fusion Techniques and Algorithms

In AVs, the multi-sensor fusion methods and algorithms serve as the cornerstone for building robust and precise systems that enable reliable perception, accurate localization, and efficient navigation. It supports the integration of data from various sensor types such as GPS, camera, Lidar, and radar sensors, to construct a more comprehensive understanding of the surroundings, thereby, enhancing situational awareness in the highly dynamic and complex driving environment. Over the years, the sensor fusion techniques and algorithms have been studied significantly and well-established in the literature [

49,

57,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84]. Fusion techniques and algorithms can be classified into: (a)

traditional approaches and (b)

advanced approaches. In traditional approaches, the algorithm utilizes well-established mathematical frameworks, such as deterministic rules, probabilistic theories, and optimization-based criteria, to combine data from multiple sensors. It offers robust, efficient, and interpretable solutions to multi-sensor fusion, specifically in scenarios where the systems require transparency in its decision-making processes and has limited computational resources. Nonetheless, traditional approaches can pose a challenge in nonlinear, highly dynamic, and unstructured environments. Its reliance on predefined models or assumptions about the data distribution may result in suboptimal performance when the assumptions are inaccurate or violated [

76].

Conversely, algorithms in advanced approaches leverage complex DL techniques to process, analyze, and integrate data from various sensors. It represents a significant shift towards data-driven methodologies as it employs a multi-layered structure of algorithms (also known as deep neural networks [

85,

86]) and big data to learn the complex representations, nonlinear relationships, and intricate patterns between multiple sensor inputs for multi-sensor fusion. Essentially, these algorithms are designed to adapt to complex, high-dimensional, and unstructured data, such as camera images, which enables the algorithms to generalize effectively across diverse and dynamic real-world driving environments. As a result, the algorithms provide enhanced perception and navigation capabilities, ensuring reliable performance in challenging and dynamic driving conditions. Nevertheless, as algorithms in advanced approaches continue to advance, their lack of interpretability presents significant challenges in ensuring safety, trust, transparency in its decision-making processes, and accountability, particularly in critical applications such as AV. Besides, DL techniques are computational complex due to its intricate underlying architecture, which can lead to increased latency and resource consumption [

11,

76,

87].

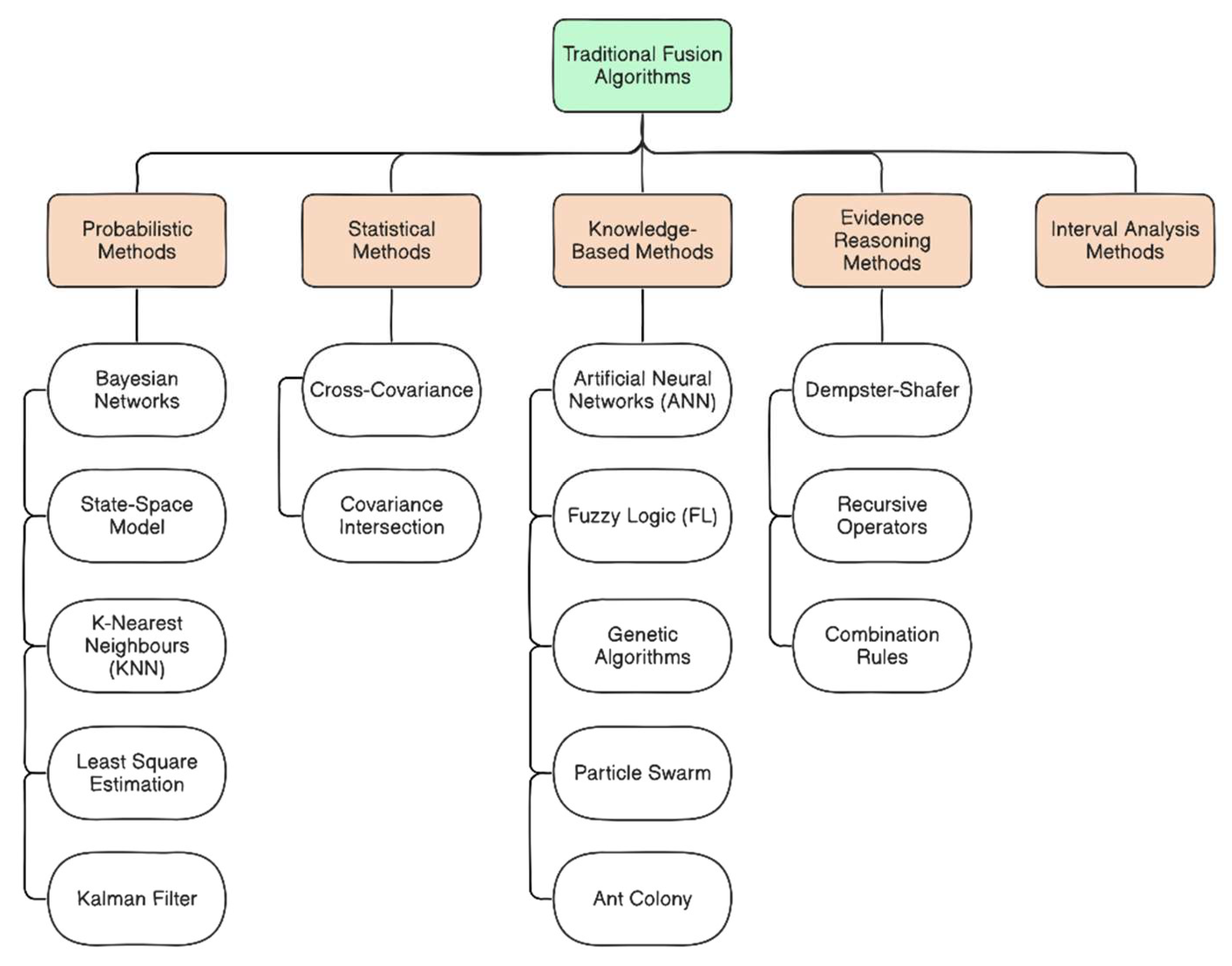

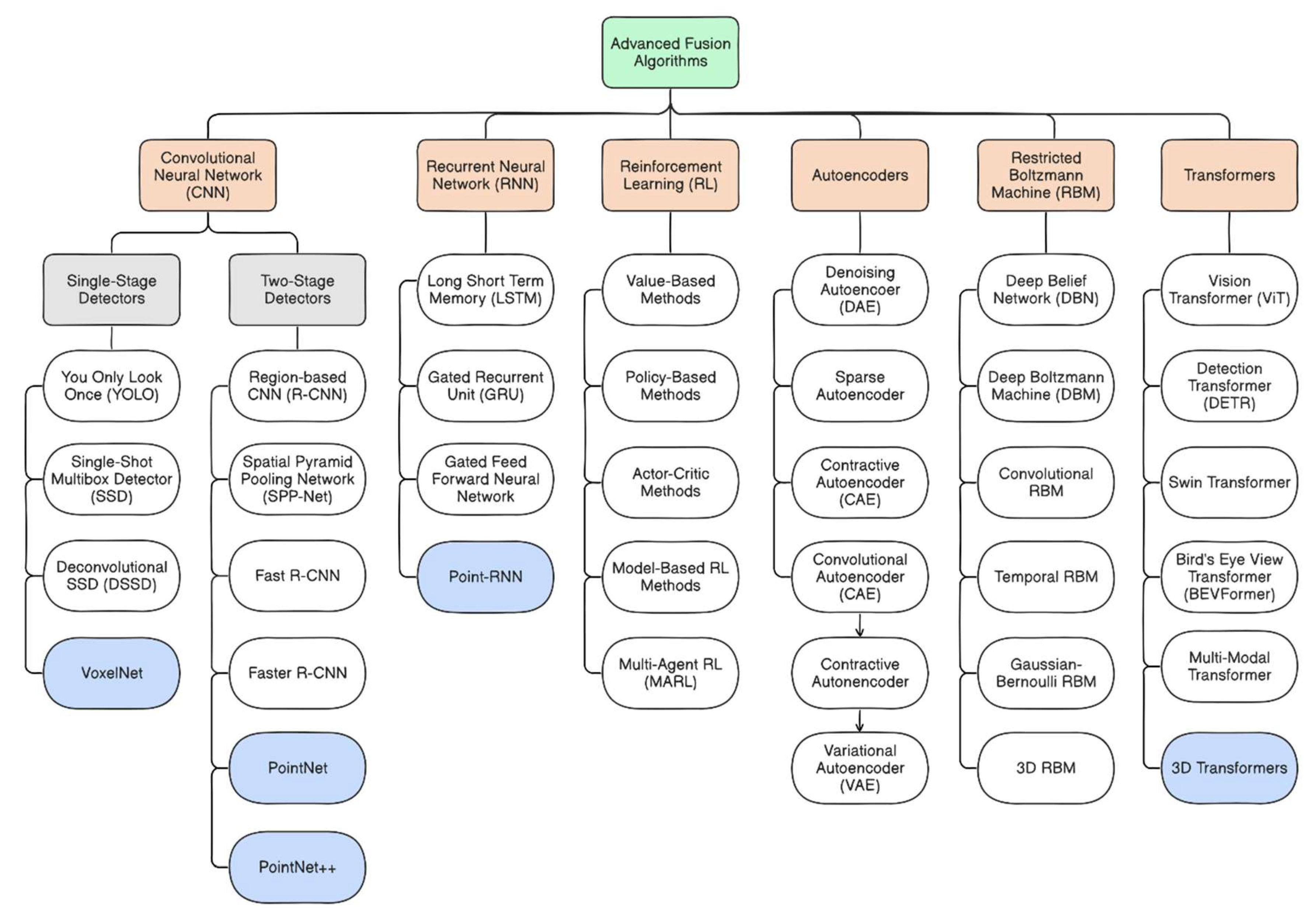

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 below demonstrate the traditional and advanced approaches, respectively, highlighting examples of techniques and algorithms that are commonly used in AV systems for tasks such as object detection, localization, and navigation.

Figure 7 exemplifies the traditional fusion algorithms, which include well-established techniques that rely on mathematical models, statistical approaches, knowledge-based theory, and probabilistic frameworks. These techniques are often adopted in scenarios where the dynamics of a system are well understood, and the noise characteristics are predictable [

76]. In [

88], the scholar utilized the

Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) algorithm, an adaptation of the Kalman Filter (KF) algorithm for nonlinear state estimation [

89], to incorporate GNSS absolute positioning values and real-time IMU input data. It addresses the potential drift inherent in IMU data during sensor fusion processes, ensuring accurate and reliable estimates of the vehicle’s position and orientation and ultimately improving the robustness and precision of the navigation system in AVs.

Figure 8 depicts the advanced fusion algorithms, which leverage modern DL approaches such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Restricted Boltzmann Machine (RBM), Transformers, Reinforcement Learning (RL), and Autoencoders [

57,

75,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99]. These techniques are effective in processing complex, high-dimensional input data and are designed to adapt to the dynamic and unpredictable characteristics of real-time driving environments. For example, the scholar in [

100] contributed to a novel multi-object tracking system that utilizes three trained

Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) models to perform data association, tracking updates, and object position estimation. LSTM model is an RNN-based technique that is designed to capture long-term dependencies in sequential data, which is ideal for tasks like time-series prediction of an object trajectory or vehicle motion prediction [

101].

In complex applications like autonomous driving systems, traditional and advanced fusion algorithms are commonly utilized in tandem to leverage the strengths of each approach, also known as the hybrid approach [

102,

103]. This synergistic integration is critical for achieving optimal performance in diverse tasks, such as environmental perception and motion trajectory estimation, where the robustness and efficiency of traditional methods complement the adaptability and learning capabilities of advanced DL algorithms. In [

104], the authors proposed a hybrid approach to develop a parameter-free state estimation framework for GPS-based maneuvering-target tracking and localization in AV applications. It features a parameter learning module that integrates a

transformer encoder architecture with an

LSTM network to effectively capture the motion characteristics of the system from offline state measurement data. In addition, the framework incorporates the

Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm, which is a well-established statistical approach for parameter estimation in probabilistic models [

105]. The EM algorithm estimates the measurement and dynamic characteristics of moving targets in real-time and refines the system parameters based on the outputs of the learning module. Lastly, a

KF algorithm is used to deliver precise statement estimations, thereby enhancing the accuracy of trajectory tracking predictions. This synergistic integration of traditional algorithms and advanced learning techniques provides a robust solution to estimate state and track trajectory of maneuvering-targets in real time. Hence, it effectively mitigates the impact of sensor noise e.g., Doppler shift, occlusion, and flicker, and eliminates the need to explicitly model the complex dynamics and measurement characteristics of the system.

In [

106], the authors introduced YOLO-ACN, a novel and efficient detection framework specifically developed to improve detection precision and overcome the challenges of detecting small targets and occluded objects within complex environments. It includes a lightweight feature extraction network with an attention mechanism, built upon the architecture of the

You Only Look Once (YOLO) neural network, particularly YOLOv3 [

107], to improve focus on small target detection. YOLO is a single-stage detector that simultaneously predicts multiple bounding boxes (detected objects) and class probabilities on an image in real-time [

108]. In addition, the network features a modified variant of the NMS classical algorithm, referred to as

Soft-NMS, within its post-processing phase to eliminate redundant bounding boxes while reducing the likelihood of discarding occluded objects, especially in densely populated environments. Unlike traditional NMS, which eliminates overlapping bounding boxes that exceed the predefined IoU threshold, Soft-NMS retains overlapping boxes with adjusted confidence scores; thereby, improving detection performance in complex scenarios [

109,

110]. As a result, this synergistic integration has significantly enhanced detection performance and robustness, particularly in recognizing small targets and occluded objects within complex environments, such as urban areas with high pedestrian density.

Ultimately, the selection of the most suitable techniques for the hybrid approach depends on the specific requirements and use cases of the intended application. In complex and dynamic scenarios, leveraging a combination of traditional and advanced algorithms has become a preferred strategy to capitalize on their complementary strengths. This combination not only enhances overall performance but also improves the precision and reliability of the system, ensuring that it is optimized to address the distinct challenges associated with each driving task.

Table 4 below provides an overview of the advantages and weaknesses of both traditional and advanced learning algorithms utilized in multi-sensor fusion systems for AV applications, such as the

UKF,

Particle Filter (PF),

YOLO,

Dempster-Shafe Theory (DST),

PointNet, and

Faster R-CNN [

11,

76,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129]. Besides, this table focuses on their applications to dynamic driving tasks, such as object detection, tracking, and localization and mapping, which are essential for the safe and efficient operation of autonomous driving in complex and dynamic driving settings. For a comprehensive discussion of traditional and advanced learning methods for object detection in 3D point cloud data (out of scope in this manuscript), readers are recommended to refer to [

57,

94,

97,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136].

2.3. Challenges in Multi-Sensor Fusion

In AVs, integrating multiple sensor data, otherwise known as multi-sensor fusion, is a cornerstone for implementing precise and robust systems capable of achieving high levels of perception, localization, and mapping essential for autonomous operations. By synergistically integrating information from complementary sensor modalities, multi-sensor fusion allows AVs to construct a comprehensive and dynamic understanding of their environment. In addition, by leveraging unique strengths of various sensors and traditional and advanced fusion algorithms, multi-sensor fusion significantly enhances the capability of AVs to detect obstacles, interpret traffic patterns, and navigate effectively through complex and unpredictable driving environment. Nonetheless, while multi-sensor fusion has revolutionized the capability of AVs to interact effectively with their surroundings, it also introduces several critical technical, operational, and interpretability challenges that need to be addressed for the successful deployment of reliable, safe, scalable, and interpretable (transparent) autonomous systems in real-world applications.

One of the primary challenges is sensor noise, which refers to inaccuracies, inconsistencies, or irrelevant data introduced by individual sensors due to a combination of external interference, hardware limitations, and environmental conditions, such as rain, snow, or dense fog. In [

139], the authors presented a comprehensive overview of the challenges associated with radar technologies in autonomous driving systems. A major issue identified is the occurrence of spurious observations, also known as clutter, which arises due to multiple reflections off surfaces in the surroundings, a phenomenon commonly known as multipath. In some cases, such clutter can be difficult to distinguish from real detections, leading to false positive detections in learned radar-based detection models. This, in turn, can significantly undermine the overall system performance and the ability to make precise, reliable, and trustworthy decisions. In our previous exploratory research [

11]

(Figure 4), we observed multiple instances of false-positive and inconsistent detections within the off-road testing environment, which includes metal objects with corrugated surfaces, traffic cones, and guardrails. These issues were caused by multipath propagation, which distorts sensor signals and leads to inaccurate and unreliable detections in complex environments [

140]. A study in [

141] showed that Lidar sensors can generate false-positive detections in rainy weather due to reflections from raindrops, and wet surfaces may cause laser beams to scatter, resulting in artifacts such as mirrored objects appearing below the actual ground surface. Therefore, these factors can undermine the accuracy and reliability of the sensor outputs, posing significant challenges for ensuring reliability and precision of autonomous driving operations.

In addition, the heterogeneity of sensor modalities and the ensuing system complexity represent another major challenge in multi-sensor fusion. AVs are generally equipped with a diverse set of sensor types, including cameras, Lidar, radar, ultrasonic sensor, and GPS, each with distinct operational attributes that contribute to their strengths and weaknesses. For example, radar is resilient in poor weather but offers lower spatial resolution; Lidar offers high-resolution depth information but is computationally intensive; and cameras capture rich visual detail but are sensitive to lighting and weather conditions. Nonetheless, integrating these diverse sensor types introduces significant complexity in algorithmic design and computational processing. It requires sophisticated and innovative fusion algorithms that can handle differences in sensor data format, resolution, and spatial-temporal synchronization [

11] while maintaining the overall AV system performance and reliability. Moreover, the complexity of the fusion systems escalates as additional sensors are incorporated to enhance the robustness of perception and support real-time decision-making. It results in the generation of big data, imposing significant demands on computational resources and necessitating innovative real-time processing capabilities to maintain timely and accurate responses. Furthermore, it also intensifies the difficulties associated with testing and validation as rigorous evaluations across varying driving scenarios and environmental conditions are essential to minimize failure risks and ensure dependable and safe operation in real-world contexts [

142,

143].

In AVs, the volume of data generated by multi-sensor fusion systems is significantly extensive, highlighting the complexity and sophistication of sensor suite employed to perceive and navigate the environment. The continuous operation of these sensors generates high-dimensional, multi-modal data streams, with throughput often reaching multiple gigabytes per second or even terabytes per hour, depending on system configuration (how many sensors are integrated into the system), sensor resolution, refresh rates, and operating conditions [

144,

145]. This immense data volume is essential for robust perception, localization, and decision-making, but it introduces significant challenges in implementing low-latency data processing pipelines and optimizing the utilization of computational resources. In the event of delays or latency within the data processing pipeline, the AV may fail to respond to dynamic changes in its surroundings, such as unforeseen objects or pedestrians entering the roadway [

146]. Besides, the limitations of computational resources in embedded systems that are often utilized in AVs require deliberate trade-offs between accuracy and computational efficiency, needing the optimization of complex fusion algorithms to operate within hardware constraints. Moreover, safety-critical autonomous systems require multi-sensor output verification and cross-validation to address the potential risks of sensor noise, malfunction, or environmental interference; hence, posing significant challenges in its computational load [

147]. As a result, addressing these challenges necessitates innovative approaches, such as leveraging parallel processing, hardware accelerators, e.g., Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) or Tensor Processing Units (TPUs), and optimized fusion frameworks [

148,

149,

150].

In addition, multi-sensor fusion systems in AVs are susceptible to malicious attacks, which pose significant risks to the integrity and reliability of their autonomous operation. AVs rely on seamless integration of multiple sensor modalities, but are vulnerable to different forms of adversarial interference, such as spoofing, jamming, and signal manipulation. For example, attackers may broadcast incorrect yet plausible GPS signals to mislead the AV about its true location and leading to navigation inaccuracies [

151]. Similarly, adversaries exploit the vulnerabilities of deep neural networks and introduce subtle perturbations to images that are often imperceptible to the human eye, otherwise known as adversarial images. It causes the trained model to produce erroneous predictions or classifications [

152]. Moreover, attackers may target the underlying software or communication infrastructure of the multi-sensor fusion system through cyberattacks to overload the system, disrupt data transmission, or manipulate sensor inputs. Thus, these attacks compromise the robustness and reliability of decision-making processes and endanger its overall safety during autonomous operations [

153]. In recent years, the

Zero Trust framework has emerged as a key approach in the design and implementation of multi-sensor fusion systems in AVs. It challenges the traditional assumption of inherent trust within the ecosystem and operates under the core principle that no component or node in the autonomous system should be automatically trusted [

154,

155]. For a comprehensive exploration of the different attack models and their associated defense strategies (out of scope in this manuscript), readers are encouraged to refer to the research established in [

152,

153,

154,

156,

157,

158,

159,

160,

161].

In complex fusion algorithms, the lack of interpretability and explainability presents significant challenges in ensuring transparency and accountability in autonomous operations. One crucial aspect of this challenge is the necessity to provide clear and comprehensible explanations to stakeholders regarding the decisions and actions made by the autonomous system. For example, end-users often require comprehensible explanations to foster trust and confidence in the reliability of autonomous driving technologies, particularly in safety-critical applications such as AVs. Similarly, regulatory authorities seek comprehensive insights into the decision-making processes to evaluate compliance with well-established safety protocols, legal standards, and ethical guidelines [

162]. Additionally, the necessity for explainability is critical for fostering user acceptance of autonomous driving technologies. A lack of clarity in explaining the rationale behind specific actions taken by autonomous systems, especially in situations involving errors or unanticipated outcomes, can significantly undermine user trust and hinder the acceptance of autonomous driving technologies [

163,

164,

165]. Consequently, overcoming these challenges necessitates a focused effort to design and implement multi-sensor fusion methods and models that strike a balance between complexity and transparency by leveraging XAI techniques to provide valuable insights into how inputs from various sensors are processed and integrated. By enhancing the transparency of decision-making processes, developers can facilitate regulatory approval, enhance confidence and trust among stakeholders, and ensure that autonomous driving systems are reliable and accountable in real-world applications.

3. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI)

XAI, or Explainable Artificial Intelligence, is a specialized domain within the broader discipline of AI that focuses on designing and developing techniques and models that are interpretable and comprehensible to all stakeholders. These stakeholders include, but are not limited to, (a)

researchers and

academics aiming to advance the field through theoretical and applied insights; (b)

developers and

engineers responsible for developing and maintaining autonomous systems; (c)

end-users and

consumers who interact with autonomous systems; (d)

regulators and

policymakers to ensure compliance with established standards and safety requirements; and (e)

business leaders and

industry professionals focused on utilizing AI to drive commercial and operational success [

166,

167,

168]. XAI is vital in enhancing transparency, trust, accountability, and safety, especially in safety-critical applications such as autonomous driving. It emphasizes five core principles that serve as foundational pillars, ensuring that such systems conform to transparency, accountability, and user trust standards while achieving their intended functionalities. XAI principles include interpretability, explainability, justifiability, traceability, and transparency, as exemplified in

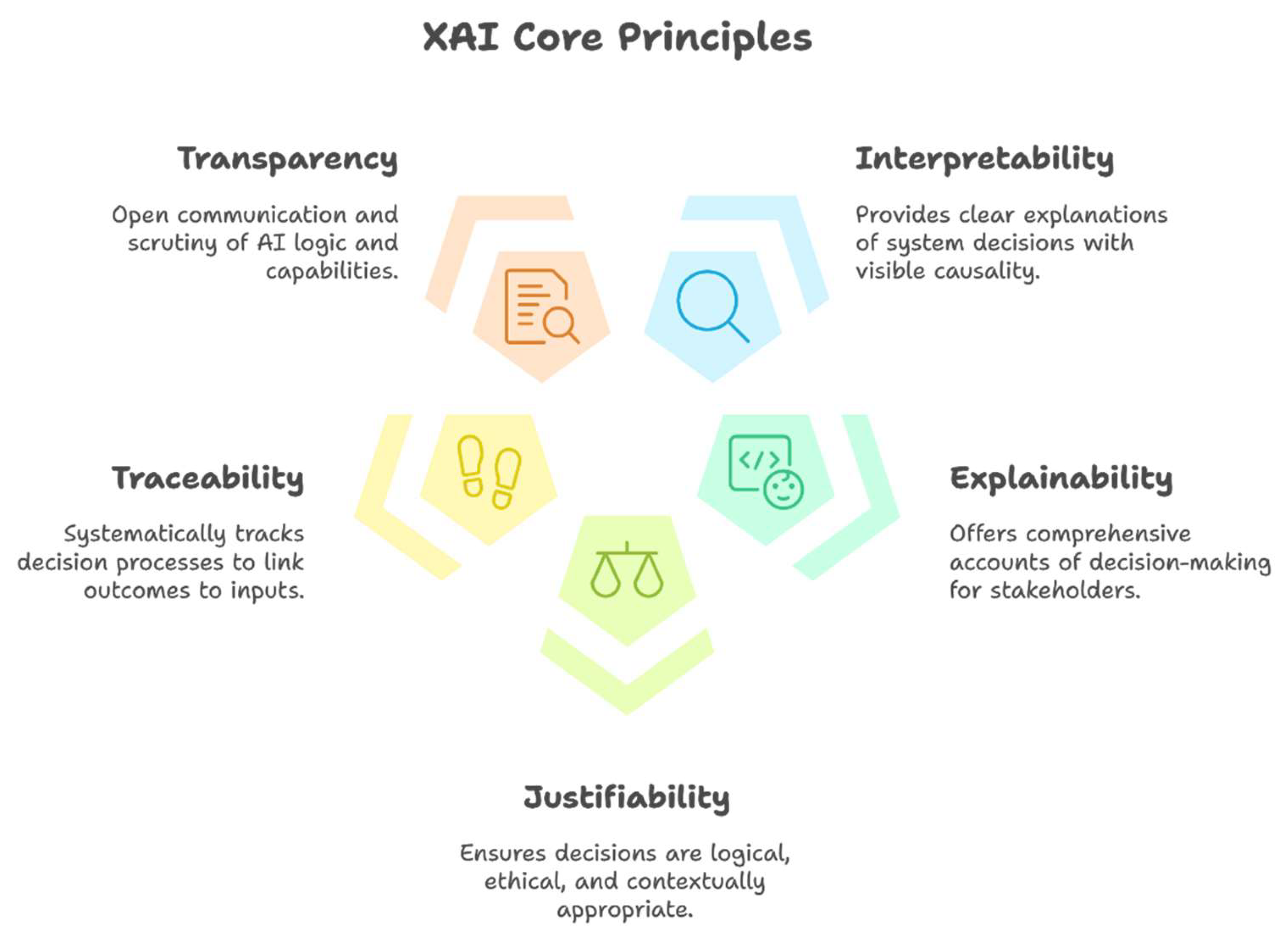

Figure 9 below [

169,

170]. It is important for readers to learn that additional XAI principles can encompass fairness, robustness, satisfaction, stability, and responsibility [

171] (comprehensive exploration of these principles is beyond the scope of this manuscript).

Interpretability. It is defined as the ability to explain or to provide clear and comprehensible explanations of the actions and decisions made by the autonomous driving system to relevant stakeholders. It is often deliberated that interpretable systems are more suitable for safety-critical applications, as such systems provide a clear and observable chain of casualties that explains the decision-making processes [

173].

Explainability. It is associated with the concept of explanation as a means of providing an interface between humans and a decision-making system that is both an accurate representation of the decision-making process and comprehensive to stakeholders [

174]. In essence, explainable systems can provide a clear and detailed account of how and why the decision was made.

Justifiability. It signifies the capability of an artificial intelligence (AI) system to provide logical, ethical, and contextually appropriate reasons for its decisions (outcome) and ensuring alignment with ethical guidelines, user trusts, and accountability [

175]. In essence, justifiability ensures that the AI decision made are justifiable and reasonable based on the given data and context. Several approaches can be used to achieve justifiability, including utilizing interpretable models, incorporating post-hoc explanation tools, and involving human experts to review and validate AI decisions [

175].

Traceability. It refers to the systematic tracking and documentation of the entire decision-making process of an AI system, ensuring that each action or outcome is traceable to its corresponding inputs, processing steps, reasoning, and outcomes. As a result, any anomalies or errors can be precisely identified and addressed, which is particularly essential in critical situations such as collisions or near-miss events.

Transparency. It involves designing and developing an AI system where the underlying logic, rules, and algorithms governing the decision-making process can be scrutinized and comprehended by all stakeholders. It also involves open and clear communication with stakeholders about the decision-making criteria, functions, capabilities, and limitations of an AI system, e.g., autonomous driving system.

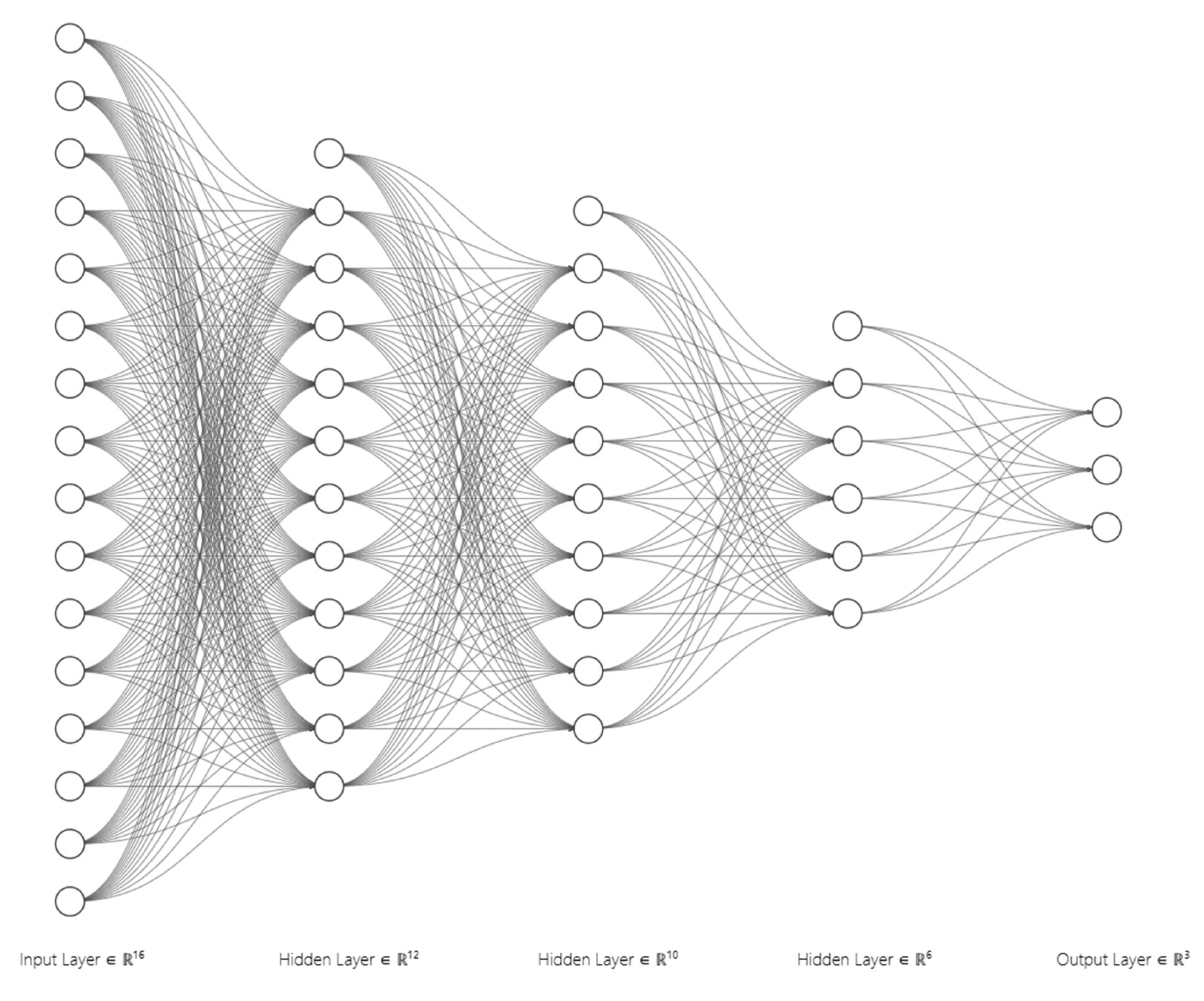

The rapid evolution of ML and DL techniques and algorithms has driven substantial advancements in cutting-edge autonomous applications, such as self-driving vehicles and humanoid robots [

176,

177]. These advancements underscore the transformative potential of ML and DL technologies in creating systems capable of performing highly sophisticated tasks, such as autonomous driving, with unparalleled precision and efficiency. However, the growing complexity and sophistication of the underlying algorithms pose significant challenges in ensuring transparency and interpretability within complex autonomous systems. In other words, the internal mechanisms of modern ML and DL models, particularly large-scale neural networks, or DNNs, and ensemble methods, are characterized by their opaque nature. Its underlying structure, i.e., multiple hidden layers and extensive parameterization, depicted in

Figure 10 below [

178], reflect the difficulties stakeholders encounter in comprehending the internal workings and decision-making processes of these models, resulting in their classification as

black-box models or systems [

179]. Besides, the black-box nature of DNN models introduces additional risks, including the potential propagation of biases and the complexities in diagnosing errors or unintended outcomes. In DNN models, the propagation of biases refers to the amplification or continuation of pre-existing biases embedded in the training data or unintentionally introduced during the design and implementation phases of the DNN models. This issue often arises from imbalances in training datasets, e.g., underrepresentation of specific scenarios, demographic groups, or weather conditions, as well as from implicit assumptions and inconsistencies in labeling practices and feature selection [

180]. For example, underlying biases in perception algorithms to detect objects and interpret road signs may lead to disastrous outcomes. As a result, developers use post-hoc analysis techniques to elucidate the decision-making processes of black-box models. However, such methods can be resource intensive, time consuming, and may not always yield definitive explanations, especially when the sources of biases are deeply embedded in complex data or algorithmic structures [

171,

181,

182,

183,

184].

In contrast to the black-box model, which operates an opaque system with decision-making processes that are difficult to understand, the

white-box model provides enhanced transparency and offers greater insight into its internal mechanisms. It emphasizes utilizing simple and self-explanatory methods, where the decision-making processes are comprehensible and transparent to human stakeholders. A white-box model is designed with simpler underlying structure and often adopts linear or rule-based traditional algorithms such as, Decision Trees, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Linear Regression, et cetera, which explicitly outline the relationship between inputs and outputs. In linear models, the predicted result can be mathematically expressed as a weighted sum of all its feature inputs, where each feature contributes to the final decision based on its assigned weight [

167]. As a result, the white-box model allows a clear and direct understanding and explanation of the decision-making processes. In autonomous driving vehicles, the decision made to decelerate in response to pedestrians crossing the road can be traced and explained through a white-box model. It would generate an audit trail that outlines the rationale behind the action, including factors such as the detection of the pedestrian’s location, vehicle’s proximity to the pedestrian, and the calculated necessity to decelerate to avoid a potential collision [

185]. However, the simplicity and interpretability of white-box models may struggle to attain the same level of predictive accuracy required for handling complex and dynamic real-world autonomous driving tasks, such as object detection. In addition, white-box models are often limited in their ability to effectively handle intricate and unseen scenarios, such as identifying subtle road hazards or reacting to unpredictable driver behavior [

167,

170,

186].

In [

169] (Figure 3), the authors presented a comprehensive discussion of the various levels of transparency that represent distinct aspects of interpretability and understanding in ML models. It consists of three distinct levels of transparency: (a)

simulatability, (b)

decomposability, and (c)

algorithmic transparency, which serve as quintessence frameworks for understanding how the internal mechanisms of ML models can be made explainable and accessible to human stakeholders. Within transparency:

Simulatability denotes the ability to simulate the behavior of an ML model through interactive experimentation or human understanding. It enables users to replicate or anticipate the decisions made without necessitating in-depth technical knowledge of its underlying mechanisms or internal architecture. In this aspect, a model is considered simulatable if it can be effectively presented to stakeholders utilizing text, visualizations, or other accessible representations. Furthermore, a simulatable model enables users to reasonably anticipate its outputs based on a given set of inputs, fostering a more intuitive grasp of its decision-making processes [

187].

Decomposability refers to the ability to disaggregate an ML model into smaller and interpretable components, such as inputs, parameters, and computations. In essence, decomposability signifies the capability to explain the functioning of a model by examining its constituent elements, providing clarity about how specific inputs influence the outputs, how parameters are optimized, and how intermediate calculations are carried out to reach a final decision. For example, decomposability enables engineers to isolate and explain the contribution of individual subcomponents in autonomous driving, including object detection, trajectory planning, and control systems, which is critical for technical debugging, model refinement, and ensuring compliance with legal and ethical standards. However, in practice, achieving decomposability in intricate ML models, such as DNNs, can be challenging due to their non-linear relationships and the distributed nature of their data representations [

169,

188].

Algorithmic transparency, as the name suggests, pertains to the extent to which the internal workings and decision-making processes of an algorithm can be clearly understood, elucidated, and scrutinized. In essence, it emphasizes the visibility of how an algorithm operates, from its initial design through to its decision outputs. In practical terms, algorithmic transparency ensures that the reasoning behind the algorithm decisions can be traced back to its underlying mathematical or computational principles, which are indispensable in identifying and rectifying potential biases, addressing embedded biases, and uncovering unintended behaviors that could compromise the precision and integrity of an ML system. In autonomous driving, understanding the decision-making processes of algorithms, such as how a vehicle decides when to stop or how it identifies and avoids obstacles, is vital in ensuring safety and adherence to regulatory standards. However, the main limitation of algorithmically transparent models is that these models must be fully accessible for analysis using mathematical methods, which is challenging for deep architectures due to the opaque nature of their loss landscapes (multiple interconnected hidden layers) [

169,

189,

190,

191,

192].

The advancement of AI models (ML and DL models) has significantly amplified the need for explainability and interpretability, particularly in safety-critical domains such as autonomous driving. In these domains, it is imperative for AI systems to not only demonstrate high predictive accuracy but also deliver transparent and comprehensible explanations for their decisions to ensure safety, reliability, and adherence to regulatory and ethical guidelines. In XAI, the distinctions between black-box and white-box models underscores a fundamental trade-off in AI models development, i.e., achieving an optimal balance between interpretability and predictive performance. As discussed, black-box models are known for their ability to process complex scenarios with high accuracy but often lack transparency in understanding the underlying processes behind their decision-making. In contrast, white-box models emphasize interpretability and explainability, offering clear and understandable decision-making processes, but may face limitations in managing complex tasks.

However, both paradigms play a pivotal role in addressing the interpretability challenges inherent in cutting-edge, sophisticated AI models, significantly contributing to enhanced accountability and transparency in ML and DL technologies. Besides, both paradigms are instrumental in fostering trust among human stakeholders, which is critical in ensuring the responsible and ethical implementation of autonomous systems within real-world environments. Therefore, addressing interpretability and explainability challenges in autonomous systems has become a primary focus within XAI research, which seeks to develop tools and techniques that can elucidate the decision-making processes of opaque systems and provide human stakeholders with actionable insights into their operations.

3.1. XAI Strategies and Techniques

XAI is an emerging field of research that aims to provide clear, comprehensible, and human-centered explanations for the decisions generated by AI systems. Recent research has investigated several strategies and methodologies designed to elucidate the decision-making processes of intricate and opaque black-box models. XAI methods can be categorized into three main categories: (a)

explanation level, (b)

implementation level, and (c)

model dependency [

193]. Such categories offer a systematic framework for understanding the diverse approaches designed to enhance the interpretability and explainability of sophisticated ML and DL systems, especially in contexts where transparency is imperative. It enables researchers and practitioners to select appropriate methods or strategies tailored to specific applications and requirements.

Explanation level refers to the scope and depth of insights delivered, addressing either the overarching behavior of the model or the rationale behind specific individual instances. This concept is subdivided into (a)

global explanations and (b)

local explanations. In

global explanations, the emphasis is on providing a detailed overview of the model’s decision-making processes (at macro-level). In essence, this approach delivers a holistic understanding of the model’s behavior and how it operates across different inputs and conditions. In turn, it enhances the interpretability of the model, offering insights into its underlying operational structure and the factors that influence its overall performance during the decision-making processes [

193]. Generalized Additive Model (GAM) are among the XAI methodologies that provide insights into a model’s decision-making process at a global level [

194]. GAM is a statistical modeling method designed to capture and analyze non-linear relationships between dependent and independent variables utilizing smooth functions to model the effects of each predictor [

195]. For instance, the research shown in [

196] utilized the GAM method to examine the relationships between kinematic variables of vehicles, such as position, velocity, and acceleration, during overtaking maneuvers. In contrast,

local explanations aim to elucidate the rationale underlying specific predictions made by the model for individual instances. It is particularly valuable in situations where understanding individual predictions is important, such as analyzing specific driving scenarios in AVs. Therefore, this approach fosters trust in high-stakes autonomous systems, ensuring safety and accountability [

162,

193]. Grad-CAM or Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping is one of the prominent XAI techniques designed to interpret the decision-making process of AI models at a local level. It is often adopted to visualize and elucidate localized decisions made by CNN-based models, particularly in image recognition and classification tasks [

197]. For instance, [

199] adopted the Grad-CAM technique to analyze DL detection models by generating heatmaps that visually explain the road semantic segmentation outputs, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of the relevance of their outcomes. Nevertheless, Grad-CAM may generate heatmaps that highlight regions unrelated to the detected objects in detection tasks, as its approach prioritizes feature importance without accounting for spatial sensitivity [

198].

Implementation level refers to the stage at which interpretability and explainability are incorporated into AI models, focusing on when and how these aspects are integrated into the design and implementation of these models. This concept can be subdivided into (a)

ante-hoc explanations and (b)

post-hoc explanations.

Ante-hoc explanation, also known as intrinsic explanation or pre-hoc explanation, refers to the interpretability mechanism that is inherently integrated into the design of the model during its development phase. Such explanations are designed to embed transparency and understandability into the model’s decision-making processes from the outset, ensuring that its operation remains explainable and transparent from the initial stage [

193,

199]. Bayesian Rule Lists (BRL) represent a prominent example of an ante-hoc explanations method. It leverages Bayesian principles to achieve an optimal balance between simplicity and predictive performance. BRL operates by composing probabilistic models that derive decision rules (IF-THEN rules) based on observed data, with a focus on selecting rules that jointly maximize the posterior probability of class labels. Therefore, BRL ensures that the resulting rule lists remain explainable and grounded in a robust statistical framework [

183,

200].

Figure 11 below depicts an example of how BRL can be used to explain the pedestrian crossing detection. In this instance, the model derives IF-THEN rule lists based on the input features, such as, vehicle speed, distance to pedestrians, weather conditions, and road type, to inform the decision-making process, determining whether the vehicle must stop, decelerate, or proceed with caution when detecting a potential pedestrian crossing scenario [

11]. Contrarily, p

ost-hoc explanations are applied after AI models, such as DNN or ensemble methods, have been trained. It aims to provide insights into the decision-making processes by analyzing how input features are translated into output decisions in opaque black-box models. Post-hoc explanation is critical for applications requiring model transparency, trust, and accountability, specifically when the model’s complexity hinders direct interpretation [

199]. Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) is a well-known post-hoc explanation technique that approximates the decision-making processes of black-box models by constructing explainable and simplified models within the local vicinity of a specific prediction, thereby allowing stakeholders to gain insight into the reasons behind a model’s decision for a particular input. For example, [

201] demonstrated a trust-aware approach for selecting AVs to participate in model training, aiming to ensure system performance and reliability. They utilized the LIME method to calculate the trust values and highlight key features that influenced the selection of each AV during the model training process.

Model dependency, as the name implies, pertains to the extent to which an explanation method is designed for a particular type of ML or DL model, or whether it possesses the versatility to be adopted across various model architectures. This concept can be subdivided into: (a)

model-agnostic technique and (b)

model-specific technique.

Model-agnostic techniques are designed to provide interpretability independent of the underlying architecture of AI models. Model-agnostic methods are extensively utilized owing to their remarkable flexibility and adaptability, which enable them to interpret diverse models and use cases. These methods often provide post-hoc explanations and operate by examining the inputs and outputs of an AI model without requiring access to its internal parameters or structures [

193,

202]. Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) serves as a prominent example of model-agnostic explanations method. SHAP provides valuable insights into the contribution of individual input features to the output of an AI model. Moreover, it facilitates detailed and granular explanations that can either focus on specific individual predictions (local explanations) or provide an overall summary of feature importance across multiple predictions (global explanations) [

203]. For instance, [

204] proposed WhONet, a wheel odometry neural network that provides continuous positioning information using GNSS data with wheel encoders measurements from the vehicle. The SHAP method was adopted to interpret the predictions of vehicle positioning, thereby enhancing its reliability and ensuring greater transparency and accountability. Contrarily,

model-specific techniques are designed to the unique characteristics and architecture of a specific ML or DL model. These methods leverage the intrinsic properties or mathematical properties of the model to provide detailed explanations of its decision-making processes. In other words, model-specific explanation methods require modifications to the explanation framework when applied to different models [

199]. Saliency maps exemplify a model-specific interpretability technique that provides pixel-level insights into the significance of input features. This method leverages gradient-based information to identify and highlight the regions of an input (image) that most significantly influence the decision-making processes of an AI model by assigning a salience score to each pixel or region [

205]. In other words, a saliency map represents a heatmap that highlights the most visually prominent objects or regions within a given scene. It is imperative to learn that certain studies consider that saliency maps can be generalized to operate in a model-agnostic manner by altering their computation to the model’s input-output behavior rather than its internal gradients [

206,

207,

208]. An illustrative application of saliency maps can be found in [

209], where the authors proposed a saliency-based object detection algorithm to detect unknown obstacles in autonomous driving environments. This approach integrates the saliency map method into the detection algorithm to amplify image features, thereby emphasizing both known and unknown objects in the environment.

Table 5 and 6 below provide a detailed overview of various interpretation techniques that are commonly employed in XAI to improve the interpretability and explainability of AI models.

Table 5 categorizes these techniques based on their interpretability level (e.g., local or global), their classification within XAI (e.g., model-agnostic, model-specific, ante-hoc, and post-hoc), and the types of data they are designed to support.

Table 6 presents a comparative analysis, outlining the strengths and limitations of each interpretation technique. By consolidating this information, the tables offer valuable guidance for researchers and practitioners in identifying the most suitable techniques for specific applications. For a more in-depth exploration of additional interpretation methods (out of scope in this manuscript), readers are encouraged to refer to [

167,

171,

179,

183,

184,

193,

194,

199,

210,

211,

212,

213,

214,

215,

216].

3.2. Roles of XAI in Autonomous Vehicles and its Challenges

AVs are inherently complex systems, incorporating advanced and intricate AI algorithms to perceive, navigate, and make real-time decisions in dynamic, often unpredictable environments. These decisions necessitate careful consideration of numerous factors, including prevailing traffic conditions, potential road hazards, and interactions with various road users – pedestrians, cyclists, and other vehicles. However, the inherent opacity of sophisticated ML and DL models, often described as the black-box nature of AI, poses significant challenges in translating complex decision-making processes into transparent and understandable explanations, particularly in contexts where trustworthiness, safety, reliability, and accountability are imperative. For example, the rationale behind the decisions to apply brakes or swerve to avoid obstacles during autonomous driving might remain obscure to human stakeholders and may undermine the confidence in its reliability and ethical alignment. As a result, the integration of XAI holds paramount importance in addressing these challenges, as it directly impacts critical factors that are essential for the successful deployment, operation, and societal acceptance of these technologies [

170].

XAI serves as a critical bridge between advanced AI-driven technologies and human understanding, providing explainable insights into the underlying decision-making processes of AI-driven systems, especially in safety-critical domains such as AVs. One of the primary roles of XAI is to improve transparency, which is a quintessence quality that enables human stakeholders to understand and evaluate the rationale behind the decisions made by autonomous driving systems. It demystifies the black-box nature of intricate AI algorithms and elucidates how inputs, such as sensor data, predetermined rules, and environmental conditions influence the decisions of acceleration, braking (deceleration), or navigating through complex traffic scenarios. These explanations are often presented using natural language depictions or visualizations, making the decision-making processes of autonomous driving systems more accessible and easier to interpret for diverse audiences [