1. Introduction

With the rising global demand for clean energy, solar power has gained significant attention as a reliable, green, and sustainable energy source. Photovoltaic (PV) cells, the core components of PV power generation systems, are interconnected in series and parallel to form PV modules, which are further grouped into PV panels [

1]. Hotspot effects, characterized by localized overheating, can reduce the power output of PV modules, increase operational costs. In severe cases, it causes fires that pose serious safety risks to solar power plants [

2,

3]. Handheld thermal imaging devices are commonly used to monitor the status of PV modules. However, the widespread distribution of PV power plants across diverse environments, such as ground installations, water surfaces, and rooftops, makes manual inspection both time-consuming and inefficient [

4]. Infrared thermal imaging, which converts thermal radiation into temperature-based images, offers a rapid and effective method for identifying surface temperature anomalies on PV panels. However, the accurate detection of hot spots is complicated by challenges such as background noise, the small size of the targets, and environmental variability, emphasizing the need for more robust and precise detection algorithms [

5,

6].

1.1. Related Works

Benefited from the development of the machine learning theories, researches on PV panel hotspot detection using infrared images has explored both shallow and deep learning methods. Dotenko et al. [

7] utilized Grubbs’ hypothesis test and Dixon’s hypothesis test to identify components containing hot spots, leveraging features such as median component temperature and histogram projections. Similarly, Jiang Lin et al. [

8] addressed the challenge of random noise in infrared images by introducing a B-spline least squares method based on grayscale histograms, combined with the Canny operator for hotspot detection. The shallow learning methods rely on handcrafted features, thus are limited by their susceptibility to noise and environmental variability. In contrast, deep learning-based detectors, including Faster R-CNN [

9], SSD [

10], and YOLO [

11], demonstrate significant potential.

The environment of PV power stations is inherently complex. Due to the limited spatial resolution of infrared images and the challenges of long-distance imaging, PV hot spots often appear as small targets. Furthermore, as network depth increases in deep learning models, feature information tends to degrade, reducing feature discrimination under interference from complex backgrounds [

12]. As a result, directly applying models like YOLO and Faster R-CNN for detecting PV hot spots in infrared images frequently leads to missed detections and false positives. To address the these challenges, Zhao et al. [

13] developed two end-to-end modules: the Neighborhood Correlation Feature Module (NCFM) for multi-scale feature learning and the Scale-aware Attention Mechanism (SAM) for enhanced feature utilization. Hao et al. [

14] introduced a hotspot detection algorithm combining a feature pyramid with a high-resolution network. While these methods improve feature extraction, some researchers believed the non-photovoltaic regions such as the normal PV arrays have an impact on detection accuracy. By accounting for the array regions, Qian et al. [

15] devised a stepwise fault diagnosis strategy, combining segmentation and detection to focus the algorithm on hotspot areas. Likewise, Yu et al. [

16] presented a Deeplab-YOLO detection method that integrates an optimized Deeplabv3+ model with YOLO v5. The primary limitation of the two-stage approach lies in its reliance on the quality of array segmentation results from the first stage, which significantly impacts overall detection accuracy.

To summarize, developing highly efficient and precise hotspot detection algorithms remains the following challenges. First, the diverse background characteristics of PV power stations, combined with low-resolution images, small target size, and blurred boundaries, present significant challenges for deep learning models to generalize effectively [

17]. Second, while considering the positional relationship between PV arrays and hotspot defects can improve detection rates, the two-stage strategy by segmenting arrays first and detecting hot spots afterward introduces a detection bottleneck [

18]. Effectively modeling the interrelationship between arrays and hot spots is crucial for enhancing detection performance. Third, PV arrays are large-scale targets with high sample volumes, while hot spots are small-scale targets with low sample volumes. Addressing the challenges of class imbalance and target size disparity is another key for designing hotspot detection models.

1.2. Motivations and Novelties

To address the aforementioned three challenges, we propose a dual-branch PV arrays and hotspot defect detection model. The motivations and contributions of the proposed model are emphasized in this section.

1.2.1. Motivations

To begin with, let us demonstrate the necessity of localizing PV arrays. On one hand, in practical operations and maintenance, localizing PV arrays allows maintenance personnel to quickly pinpoint the geographic location of hotspot defects [

19,

20]. On the other hand, PV hotspot defects are always located on arrays, making the modeling of this positional dependency a potential way for improving model robustness. However, existing studies often treat array detection and hotspot detection as independent tasks, limiting their ability to exploit the dependency. Consequently, the first motivation of this study is to process array and hotspot detection collaboratively. To achieve this, we propose a dual-branch detection model consisting of two detection branches: one for PV arrays and the other for hotspot defects. Both branch share a common backbone network to leverage shared low-level semantic features from the image. Each branch, however, is equipped with an independent detection head tailored to its specific task. The array detection head performs binary classification and rotated bounding box regression tasks, and the defect detection head handles multi-class classification and small bounding box regression tasks. The dual-branch architecture allows the model to resolve the class imbalance and scale disparity issues by designing attribute-specific modules.

The second motivation arises from the need to design specialized detection heads for each branch: one for detecting large, rotated array targets and another for detecting small hotspot targets. Existing methods based on Faster R-CNN and YOLO series, struggle to handle multiscale and rotated targets due to their fixed-scale anchor proposals. To address the anchor issue, Chen et al. proposed DiffusionDet [

21], a method that applies diffusion models to object detection, achieving competitive performance compared to established detectors. DiffusionDet formulates object detection as a denoising diffusion process by transforming noisy boxes into object boxes, which requires neither heuristic object priors nor learnable queries. The anchor-free property makes it promising for overcoming the low angle sensitivity issue in array detection, and the target-scale adaptation issue in defect detection.

The final motivation is to explicitly represent the dependency relationship between PV arrays and hotspot defects. Beyond sharing low-level image information at the feature level, we incorporate the array-defect dependencies directly into the model’s loss function. The dependency can be abstracted by

where

represent defect and array regions. As observed from (

1), our intention is to model the conditional distribution with a specifically defined inside-awareness loss. This loss function is designed to penalize cases where hotspot defects are detected outside array regions, while simultaneously encouraging the model to generate small-scale and consistent-scale bounding boxes for hotspots.

1.2.2. Novelties

Based on the aforementioned motivations, we propose a dual-branch photovoltaic array and hotspot collaborative detection model. The key contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

A dual-branch detection network architecture is proposed. The proposed network includes two branches—one for PV arrays and the other for hotspot defects. The branches share low-level image features to model their correlations, while possess independent detection heads to learn high-level semantic features. This separable architecture enhances the flexibility of the network, alleviating the class imbalance and scale disparity issues between arrays and hotspots.

A diffusion-based rotated bounding box detection branch is introduced for photovoltaic arrays, alongside a small-object detection branch for hotspot defects. The anchor-free nature of the diffusion-based approach improves sensitivity to rotation angles and adaptability to varying target scales.

The inside-awareness loss function is developed for the dual-branch model to explicitly models the dependency distribution between arrays and defects. This loss function penalizes deviation in their internal and external relationships, guiding the model to learn bounding boxes for hotspot defects located within arrays. The inside-awareness loss comprises two components: Inside IoU and Union-over-Convex-Hull loss. These terms guide the model to generate bounding boxes with compact scales and consistent scale ratios. Experimental results demonstrate that this loss significantly enhances the robustness of the detection model.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Diffusion Theory

The denoising diffusion probabilistic model [

22] and its variants [

23,

24,

25,

26] are a series of generative models consisting of the forward diffusion process and the reversing denoising process. The diffusion process projects natural distributions into a prior distribution, typically a Gaussian, by iteratively adding noise. Formally, given a data sample

, its state at timestamp

t, denoted as

, is generated as:

where

is an empirical parameter controlling noise variance at timestep

t. The denoising process learns to reverse the forward process, i.e., starting from pure noise and gradually removing noise to restore the original data distributions. Mathematically, the reverse process aims to learn the conditional probability distribution

:

where

and

represent the mean and covariance, respectively, and are parameterized by

, often implemented using neural networks. By modeling and training these two processes, diffusion models are capable of generating high-quality data samples from noise.

2.2. Tailored Diffusion in Object Detection

Recent studies [

21,

27,

28,

29,

30] have shown promising results by adapting diffusion processes for object detection. This success can be attributed to two key factors. First, the iterative denoising process provides fine-grained control over generation steps, which aligns seamlessly with the iterative nature of object detection—progressively refining bounding boxes and classifications. Second, diffusion models are highly effective at modeling complex data distributions without the need for adversarial training, which is often unstable. This strength makes them particularly well-suited for detecting objects in diverse and intricate scenes. DiffusionDet [

21] frames the object detection task as a denoising diffusion process. During training, the model begins with random noise bounding boxes

and gradually learns to transform these noisy boxes into accurate object boxes through a trained neural network

. In the inference phase, DiffusionDet starts with randomly initialized bounding boxes sampled from

and applies the learned

to iteratively refine the predicted boxes. Likewise, DiffAD [

28] and Diff3D [

30] employ specialized networks to model the denoising diffusion process. DiffAD predicts the ground truth from a randomly sampled action distribution, while Diff3D focuses on predicting the 3D target box.

While existing studies have achieved success in detecting general objects, actions, and 3D objects, research on detecting small or oriented objects remains blank. In this work, we propose a dual-branch diffusion pipeline to address small and oriented object detection tasks simultaneously. The bounding boxes of the defect samples and the array samples are predicted using a shared image encoder and their respective denoising decoder and , where the random and are sampled from their respective prior distributions.

3. Dual-Branch Photovoltaic Diagnose Network

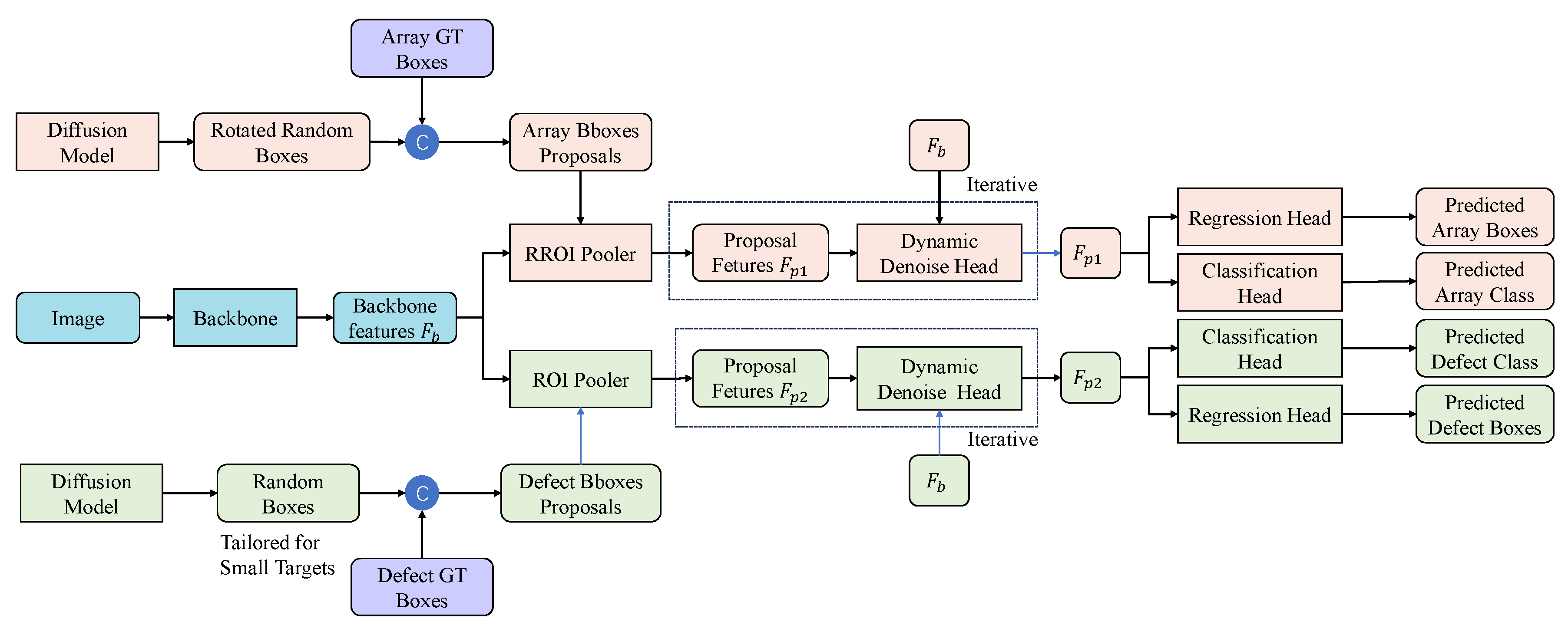

This section outlines the proposed dual-branch photovoltaic diagnostic network. The framework is illustrated in

Figure 1.

Section 3.1 presents the overall structure of the dual-branch architecture.

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.3 detail the array branch and defect branch, respectively.

3.1. Dual-Branch Architecture

Image Encoder: In the context of object detection, the denoising process in the Diffusion architecture corresponds to the iterative refinement of bounding boxes. As described in DiffusionDet, we employ Bounding Box Alignment on the feature maps extracted by the image encoder to perform this refinement, thereby avoiding the high computational cost of directly iterating on the image. Both the array and defect branches share the same image encoder to emphasize their common characteristics. However, photovoltaic defects, being small targets, are particularly vulnerable to the loss of low-level texture information caused by down-sampling operations in multiple convolutional layers. To mitigate this, we incorporate a feature pyramid structure (FPN) into the encoder backbone to preserve low-level features. In the subsequent network, the shallow features p2 and p3 from FPN are utilized as inputs to the defect branch, while the semantic features p4, p5, and p6 are fed into the array branch.

Denoising Decoder: The denoising decoder’s role is to capture the fine-grained, branch-specific features unique to each detection task. The decoder for the array branch takes the semantic features from FPN and the proposal features aligned by the Rotated Region of Interest (RROI) Pooler for randomly rotated bounding boxes as input. It employs a multi-layer dynamic denoising head to iteratively refine these representations. Similarly, the decoder for the defect branch uses the shallow features from the FPN and the proposal features aligned by the ROI Pooler for randomly small bounding boxes as input. This decoder also employs multi-layer denoising heads, but its weights are not shared with the array branch. To further integrate texture features into the decoders, particularly for the defect branch, each denoising head incorporates the corresponding FPN features as part of its input.

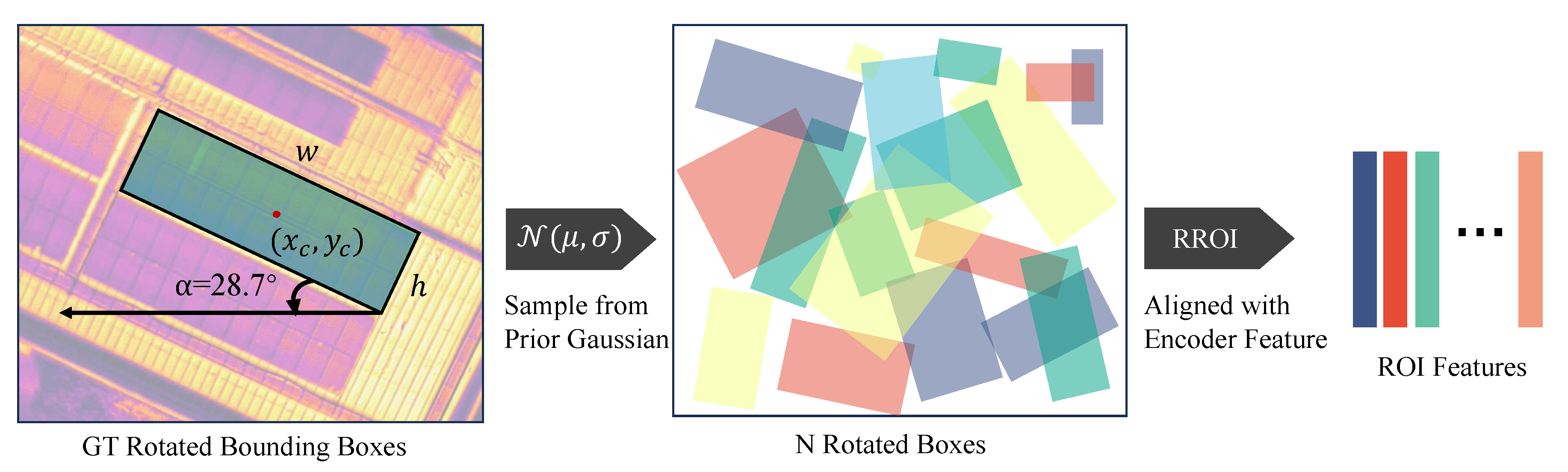

3.2. The Array Branch

The array branch primarily consists of randomly rotated bounding boxes generated by the diffusion process, an RROI module, a denoising decoder, a rotation box regression head, and a binary classification head. Unlike the horizontal bounding boxes used in [

21], each rotated bounding box is represented as a five-dimensional vector

, including an additional rotation parameter

. The rotation angle

, as illustrated in

Figure 2, is normalized to

to facilitate Gaussian sampling. The random rotated bounding boxes are passed to the RROI module, which aligns the encoder features with the corresponding regions. The aligned RROI feature are then passed to denoising decoder and the functional heads.

Following the offset regression for object detection, we formulate the regression target of the rotated bounding box as:

where

and

represent the ground truth offsets for the bounding box center,

w and

h denote the width and height offsets.

represents the target offset vector. These regression targets are normalized to account for variations in scale and ensure stable training. The rotation box regression head and the binary classification head take the output features of the denoising decoder as their inputs. During the training phase of the array branch, the loss function is a combination of three components: Smooth-L1 loss [

9] for regression, generalized Intersection over Union (gIoU) loss [

31] for bounding box alignment, and Binary Cross-Entropy Loss (BCELoss) for classification. The loss function of the array branch is computed by

where

are empirical parameters.

3.3. The Defect Branch

Similar to the array branch, the defect branch consists of diffusion process, an ROI module, a unique denoising decoder, a regression head and a multi-class classification head. As mentioned earlier, PV defects are typically small targets. To better simulate the randomness of defects during the generation of random boxes, the standard deviation of the Gaussian distribution for the width and height parameters is reduced, ensuring that most generated random boxes correspond to small targets. The primary distinction between the array branch and the defect branch lies in the loss function. In addition to the Smooth-L1 loss, gIoU loss, and multi-class cross-entropy loss, the defect branch introduces an inside-awareness loss. An important observation is that PV defects are always located on PV arrays, whereas PV arrays do not necessarily contain defects. This dependency relationship constrains the conditions for defect detection, thereby improving the robustness of the detection model. The inside-awareness loss in the defect branch is specifically designed to capture this dependency.

Given a bounding box proposal

and a matching defect-array ground truth pair

, the inside-awareness loss is formulated by

where ∩ and ∪ represents the interaction and union between the input boxes,

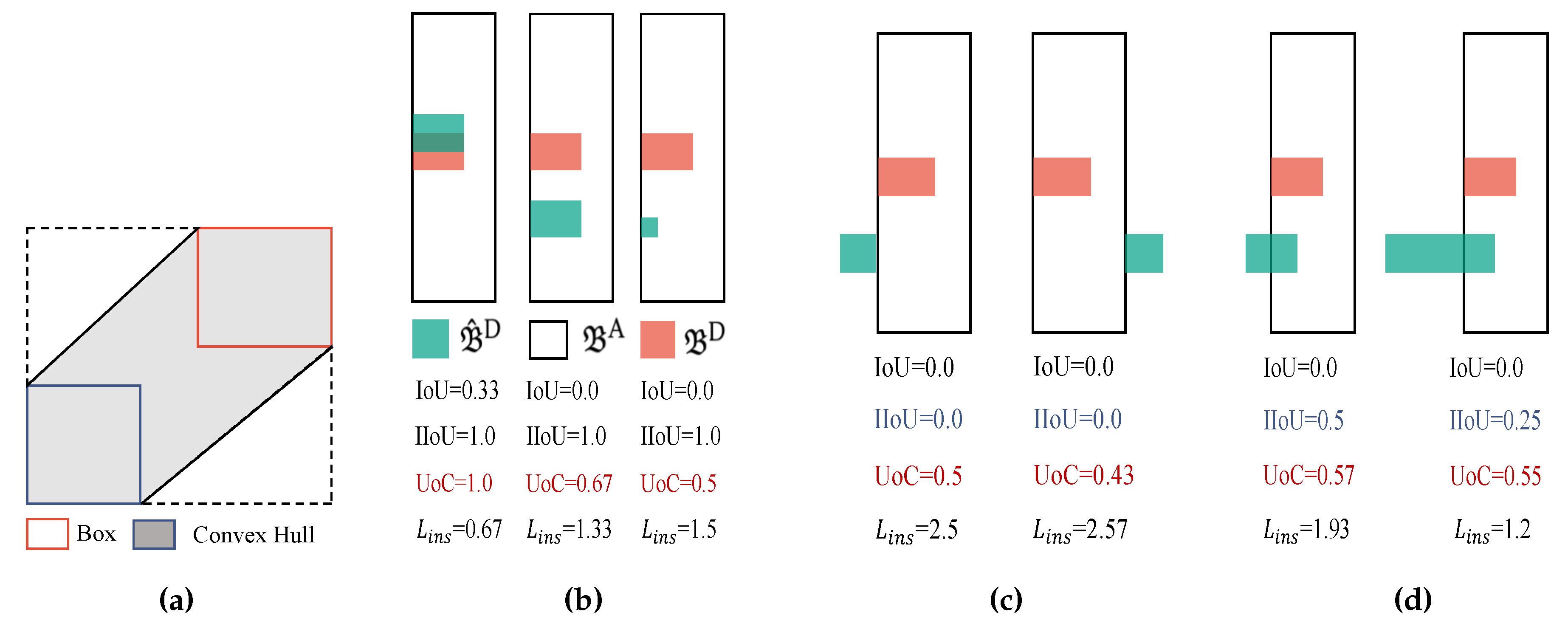

indicates the convex hull occupied by the input vertices, IIoU and UoC are abbreviations of Inside IoU and Union over Convex hull. According to (

6), IIoU focuses on the internal overlap between the defect detection box

and the array box

. It is defined as the ratio of the intersection area to the area of

. The advantages of IIoU can be summarized as follows:

Emphasizing internal inclusion. Unlike standard IoU, IIoU explicitly emphasizes whether is located inside , enhancing the model’s understanding of the internal layout of the bounding box.

Focusing on small target boxes. By using as the denominator, IIoU inherently guides the model to prioritize learning small target boxes. This aligns with the nature of defect detection, where defects are generally small targets.

Figure 3 provides examples of IoU, IIoU, UoC, and

. From

Figure 3b and

Figure 3c, it can be observed that IIoU effectively guides the model to learn bounding boxes (green solid boxes) that are located within the array box (black box).

Figure 3d further demonstrates IIoU’s preference for small target boxes: given the same overlapping area, the model favors the smaller bounding box on the left (

) over the larger bounding box on the right (

).

According to Equation (

6), UoC (Union over Convex Hull) is defined as the ratio of the union of

and

to the convex hull of

. As illustrated in

Figure 3a, the convex hull represents the smallest convex shape that fully encloses both

and

. UoC measures the degree of external expansion of the defect box

relative to the array box

. The advantages of UoC include:

Suppressing external expansion: UoC penalizes excessive outward expansion of the defect box, guiding the model to suppress such behavior. As shown in

Figure 3b and

Figure 3c, UoC decreases as the predicted box (green solid box) deviates farther from the ground truth (orange solid box). This, in turn, causes

to increase, strengthening the penalization effect.

Encouraging scale consistency: Leveraging the properties of the convex hull, UoC guides the model to predict boxes that are consistent in scale with the ground truth. For example, in

Figure 3b, under the same outside position, the middle case whose

with a scale matching

(

) outperforms the right case with smaller predicted box (

). Similarly, in

Figure 3d, the left case with scale consistency (

) is preferred over the right case(

).

IIoU and UoC, together with the standard IoU, form a complementary set of metrics that assess bounding boxes from the perspectives of internal inclusion and external boundary interaction. These metrics address IoU’s limitations in photovoltaic array and defect detection. To summarize, the loss function of the defect branch is formulated by

where

are empirical parameters.

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted extensive evaluations on a practical PV dataset and performed a comprehensive comparison with state-of-the-art hotspot defect detection methods.

Section 4.1 describes the dataset, evaluation metrics, and implementation details of the proposed method.

Section 4.2 presents a qualitative analysis, highlighting the method’s detection effectiveness across various complex backgrounds and defect types.

Section 4.3 offers a quantitative analysis, using established metrics to evaluate the overall performance of the method.

Section 4.4 conducts a comparative analysis of the proposed method and existing techniques, combining qualitative and quantitative evaluations.

4.1. Experimental Settings

4.1.1. Dataset

The experimental dataset in this study was collected from PV power stations in ground and water scenarios. The infrared images were captured using a DJI Zenmuse H20T thermal camera mounted on a drone. The drone flied at an altitude of approximately 50 meters, and images were captured during the period 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM to ensure adequate lighting conditions. There are total of 3360 images with resolution of

. The challenges of the dataset lie in the complex backgrounds, the presence of reflective phenomena, and the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the images, etc. The annotations of the PV arrays and hotspots are manually labeled using the LabelMe tool [

32]. The annotation detail of the dataset are reported in

Table 1. Accordingly, the challenges of the dataset lie in the complex backgrounds, the presence of reflective phenomena, class imbalance and scale disparity.

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

The detection performance is evaluated by precision-recall curve, where precision and recall are defined by:

where

,

,

represent number of correct detection, false alarms, and miss detection. Noting that hotspots are small targets with an area not exceeding 1200, an IoU threshold of 0.1 is adopted for hotspots, while an IoU threshold of 0.5 is used for arrays, which are generally large targets. Detection results are determined using a score threshold of 0.25, along with the aforementioned IoU thresholds of 0.1 for hotspots and 0.5 for arrays. Detection performance across different categories is evaluated using the average precision (AP) metric, derived from the precision-recall curve. To assess overall detection performance, the mean AP (mAP) is calculated. The mAP@a:b metric is employed to evaluate detection robustness, where a:b represents the range of IoU thresholds (varying from a to b at an interval of 0.1). The mAP is averaged over all thresholds within this range. Additionally, the number of model parameters, and frames per second (FPS) are used to evaluate the model volume and efficiency.

4.1.3. Implementation Details

The model adopts ResNet101 and FPN as the default backbone. Pre-trained weights from ImageNet-1K are used for ResNet backbones, while Swin backbones leverage pre-trained weights from ImageNet-21K. Photovoltaic Array Branch For the photovoltaic array branch, the random rotated bounding box is generated with the rotation angle where representing horizontal arrays and representing vertical arrays. The remaining parameters are independently sampled from . For the hotspot defect branch, the random bounding box is generated as follows: , and , emphasizing the creation of small-scale bounding boxes. Both the array and defect branches generate 500 random proposals. Each detection head includes three denoising heads, with the following coefficients: . The dataset is split into training and testing sets with a ratio of 0.9:0.1. During training, the model uses the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of , and a batch size of 16. The model is implemented using PyTorch and deployed on a machine equipped with Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6248 CPU a single Nvidia A100 GPU with 32 GB RAM.

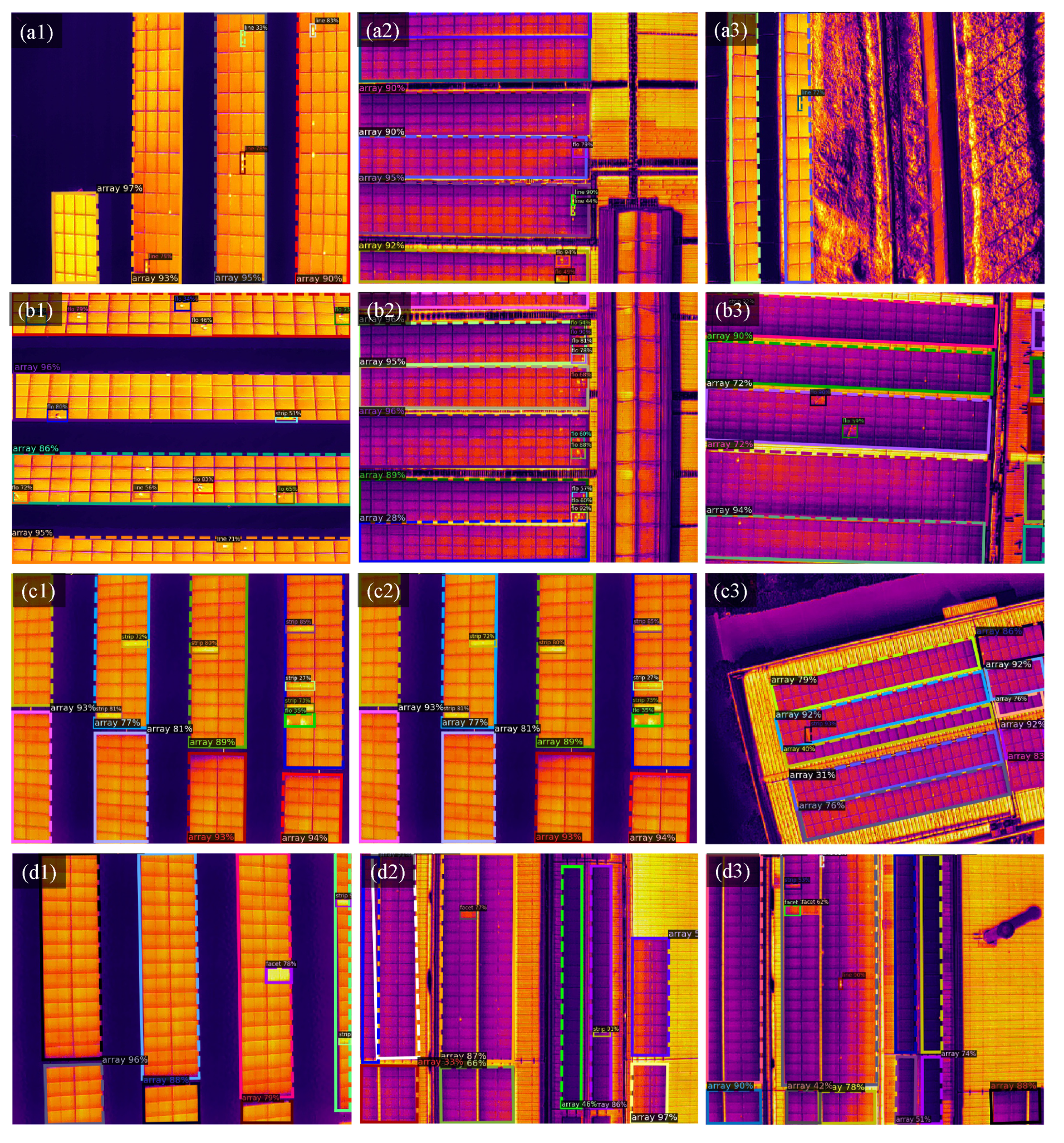

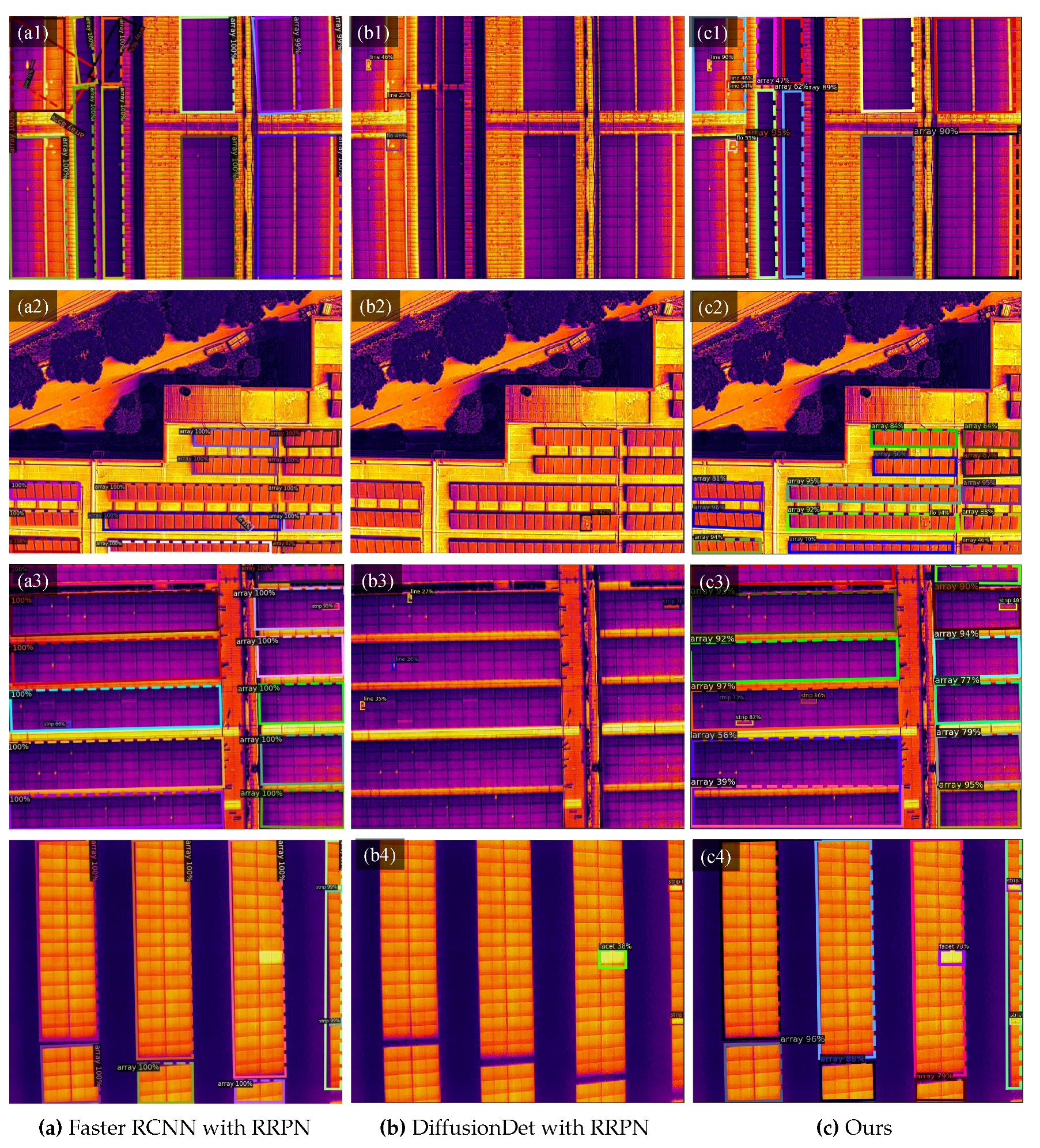

4.2. Qualitative Analysis

To intuitively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method, detection results for different scenarios and various hotspot defect types are presented in

Figure 4. The imagery highlights distinct defect types with corresponding detection scores across various photovoltaic (PV) power station scenarios, including water, roof, and ground. These line-shaped defects appear as continuous dots arranged in linear patterns, often indicating potential thermal or electrical connectivity issues. They are generally small targets, each comprising fewer than 100 pixels, making them some of the most challenging defects to detect. As shown in

Figure 4(a1)-(a4), the proposed method accurately detects the line-shaped hotspots across all three scenarios. The bounding boxes closely match the actual shapes of the hotspots, demonstrating the robustness of the detection system for small, challenging anomalies. The flocculant hotspots are characterized by diffuse and irregular heat patterns, generally caused PV module rapture. Flocculant hotspots, characterized by diffuse and irregular heat patterns caused by PV module ruptures, typically appear as small targets with sizes around

pixels. These defects exhibit diverse patterns in infrared images, such as uneven heating or diffuse hotspots. As shown in

Figure 4(b1)-(b3), the proposed method achieves high detection scores for flocculant hotspots, with bounding boxes closely aligning with the actual shapes of the anomalies. The detection results for strip-shaped and facet-shaped hotspots are presented in

Figure 4(c1)-(c3) and

Figure 4(d1)-(d4), respectively. Compared to line-shaped and flocculant-shaped defects, these hotspot types are more regular in shape, enabling our method to achieve higher detection accuracy and more precise bounding box regression.

Figure 4 also illustrates the detection results for PV arrays, which show significant variations in their arrangements across different scenarios. The proposed method demonstrates consistently high detection scores, mostly greater than 90%, and precise bounding box regression for PV arrays with varying arrangements and rotation angles. The presented results validate the proposed method’s ability to generalize across various defect types and environmental conditions.

4.3. Quantitative Analysis

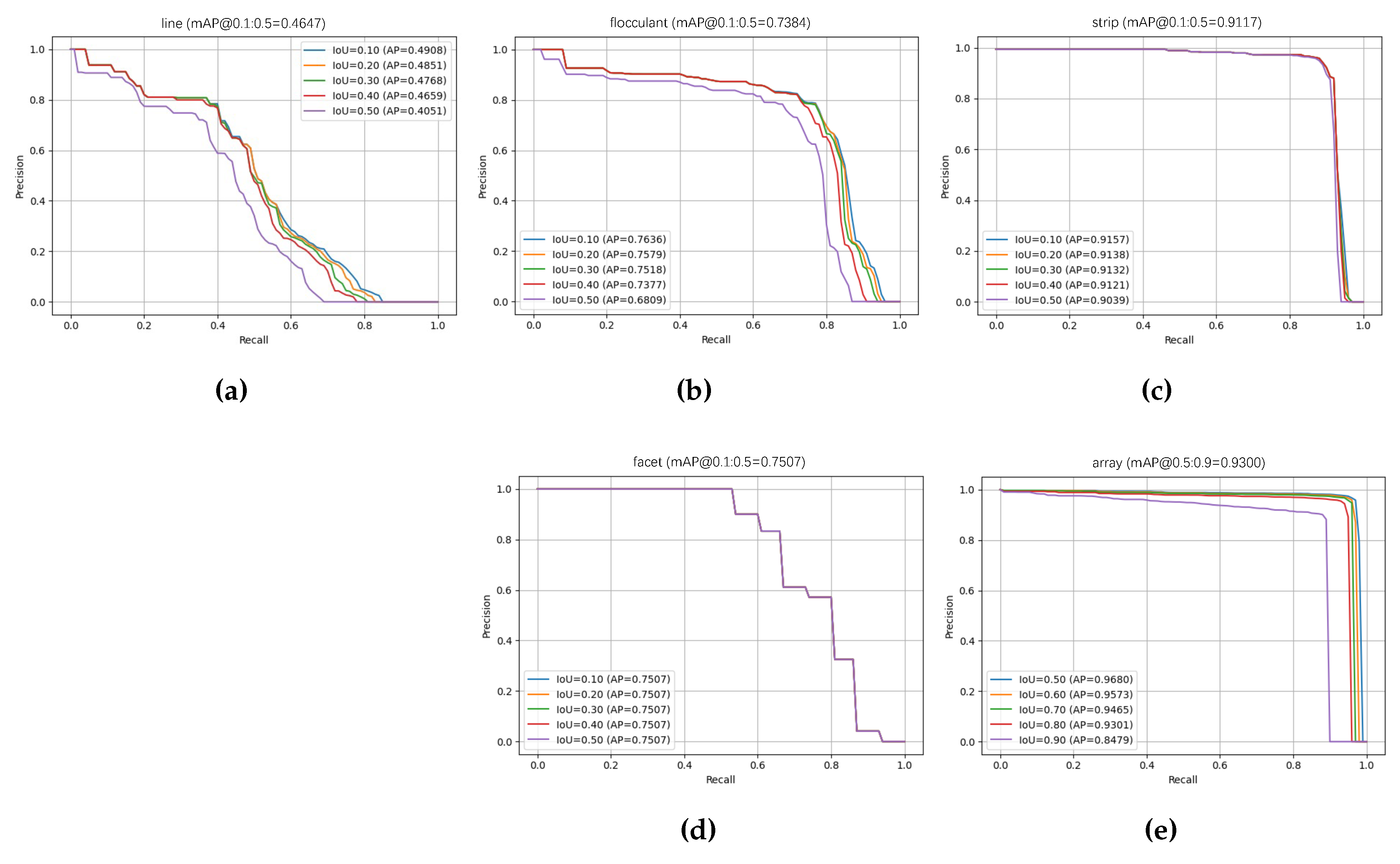

To conduct a comprehensive quantitative analysis of the proposed method, we evaluated the precision-recall (PR) curves for various hotspot types and PV arrays under different IoU thresholds, along with derived metrics.

Figure 5 presents the PR curves for each hotspot type at varying IoU thresholds, and the corresponding metrics are summarized in

Table 2. As shown in

Figure 5a, the average precision (AP) for line-shaped hotspots decreases gradually as the IoU threshold increases from 0.1 to 0.5, dropping from 0.4908 to 0.4051. Precision decreases from 0.6091 at IoU=0.1 to 0.5556 at IoU=0.5, while recall declines from 0.4900 to 0.4400. These results suggest that line-shaped hotspot detection performs better at lower IoU thresholds, as higher thresholds reduce accuracy due to the complexity of elongated structures. The PR curve for flocculant-shaped hotspots, shown in

Figure 5b, exhibits a smoother downward trend, with relatively high AP values across IoU thresholds. AP decreases from 0.7636 at IoU=0.1 to 0.6809 at IoU=0.5.

Table 2 shows precision and recall values of 0.7873 and 0.7700, respectively, at IoU=0.1, outperforming linear hotspots. These results indicate that the distinctive characteristics of flocculant targets allow the model to detect them more reliably. As shown in

Figure 5c, the PR curve for strip-shaped hotspots remains nearly consistent across IoU thresholds, with AP values ranging from 0.9039 to 0.9157.

Table 2 shows precision and recall values of 0.9325 and 0.8900, respectively, at IoU=0.5. The high precision and recall rates for strip-shaped targets are attributed to their geometric regularity, which is easier for the model to capture. The PR curve for facet-shaped hotspots, shown in

Figure 5d, demonstrates stable performance, with AP values remaining consistent at 0.7507 across all IoU thresholds.

Table 2 reports precision and recall values of 0.8333 and 0.6600, respectively, at IoU=0.1. The weaker performance compared to strip-shaped hotspots can be attributed to the smaller number of facet-shaped hotspot samples (168) in the dataset, compared to 3377 for strip-shaped hotspots. Among the different categories of hotspots, the strip-shaped hotspots achieve the highest detection performance, with AP@0.1:0.5 = 0.9117, significantly outperforming line-shaped (0.4647) and facet-shaped (0.7507) hotspots. In contrast, line-shaped and facet-shaped hotspot detection is more affected by complex backgrounds, target morphology, and sample size.

The PR curve for PV arrays, shown in

Figure 5e, highlights stable AP values under higher IoU thresholds (0.5 to 0.9), ranging from 0.8479 to 0.9680. The model achieves exceptional performance, with Precision@0.5 = 0.9671, Recall@0.5 = 0.9600, and AP@0.5:0.9 = 0.9300. These results demonstrate the model’s robustness in detecting PV arrays despite their rotational and morphological diversity. The smoothness of the PR curve further reflects the model’s ability to generalize effectively in complex scenarios, such as deserts and roof areas.

The results demonstrate that the proposed model effectively balances precision and recall across various hotspot types and scenarios, even under the challenges of small target sizes, complex backgrounds, and diverse array rotations. The high detection performance for PV arrays further validates the model’s robustness, adaptability, and generalization ability across diverse environmental conditions.

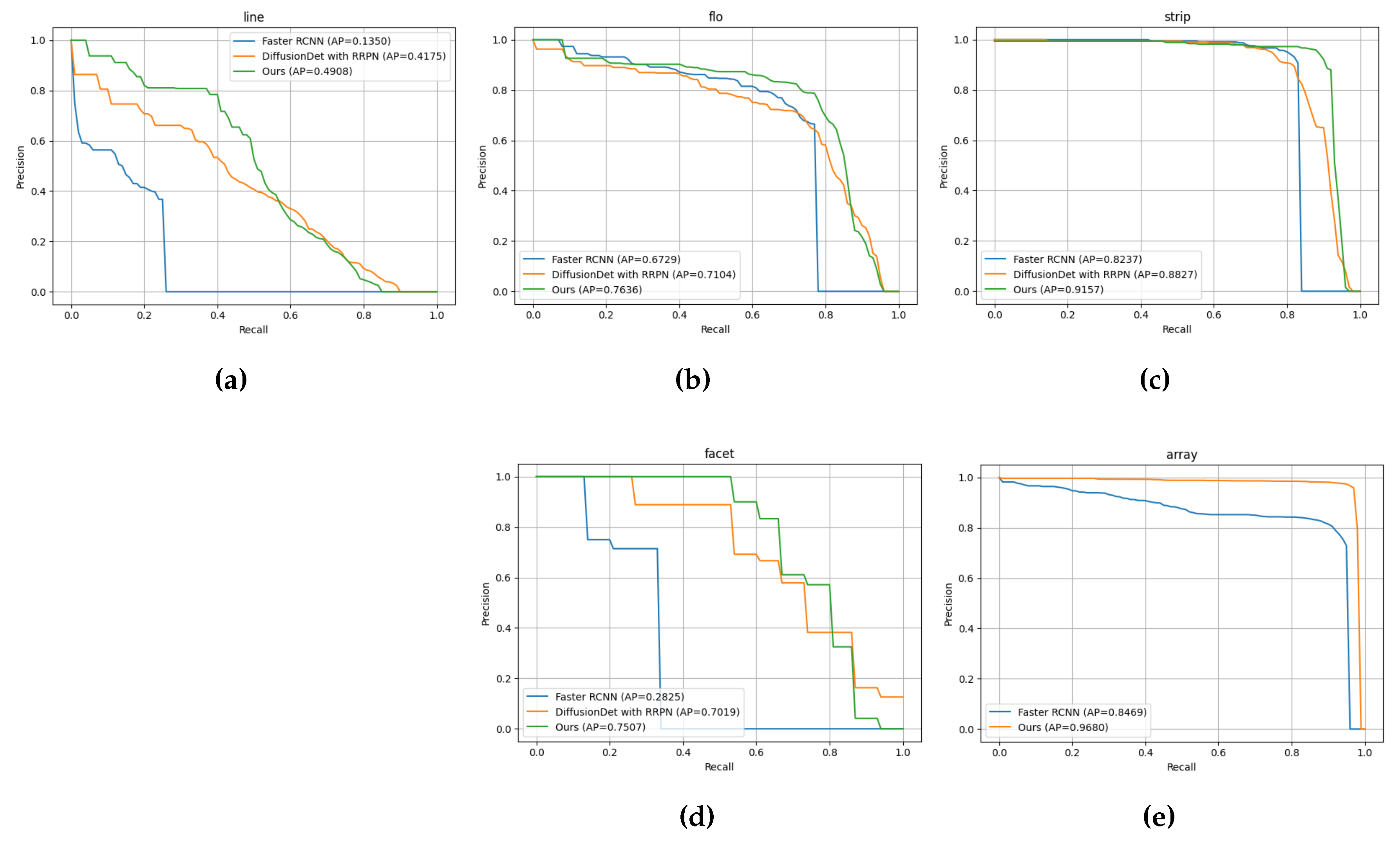

4.4. Comparative Analysis

To evaluate the advancements of the proposed detection method, Faster R-CNN with RRPN [

9] and DiffusionDet with RRPN (DiffusionDet-RRPN) are adopted as baseline methods. Both comparison methods adopt a pre-trained ResNet-50 as the backbone. Faster R-CNN with RRPN predicts rotated bounding boxes for five categories, including four types of hotspot defects and PV arrays. DiffusionDet-RRPN is a two-stage variation of [

21], which integrates RRPN into the backbone network. It performs initial binary classification and rotated bounding box regression for PV arrays. Diffusion-based random bounding boxes are generated within proposal regions, which are then fed into a denoising decoder, consistent with the one used in the proposed method.

4.4.1. Qualitative Comparison

DiffusionDet-RRPN predicts bounding boxes for the four hotspot defect types. The detection performance is evaluated through qualitative and quantitative comparisons, as well as model volume and inference efficiency. The qualitative results are illustrated in

Figure 6, which demonstrates the detection outcomes for various hotspot defects and PV arrays. In the first row of

Figure 6, three line-shaped hotspots are presented. Faster R-CNN fails to detect any of the targets, reflecting its difficulty in identifying small, elongated targets. DiffusionDet-RRPN successfully detects the most prominent line-shaped hotspot in the upper-left corner but fails to detect the other two weaker targets. In contrast, the proposed method accurately detects all three line-shaped targets. The second row contains a flocculant-shaped hotspot. Both DiffusionDet-RRPN (

Figure 6(b2)) and the proposed method (

Figure 6(b3)) detect the target with precision, while Faster R-CNN (

Figure 6(b1)) roughly identifies the defect location but fails to regress the bounding box accurately. The third row presents three strip-shaped hotspots, where Faster R-CNN (

Figure 6(c1)) and DiffusionDet-RRPN (

Figure 6(c2)) detect only one of the targets. The proposed method, however, correctly detects all three strip-shaped hotspots. Similarly, in the fourth row featuring a facet-shaped hotspot, both DiffusionDet-RRPN (

Figure 6(ad2)) and the proposed method (

Figure 6(d3)) successfully detect the target, whereas Faster R-CNN (

Figure 6(d1)) fails.

For PV arrays, Faster R-CNN with RRPN reliably detects regular, non-rotated arrays. However, it struggles with rotated arrays due to its insensitivity to angular variations, leading to significant prediction errors, as shown in

Figure 6(a1). In contrast, the proposed method effectively leverages the anchor-free properties of diffusion and the sensitivity of independent detection heads to angular learning, enabling robust detection of rotated PV arrays with diverse shapes and orientations.

From the qualitative comparison, it is evident that the proposed method outperforms existing comparative methods in detecting small targets, adapting to complex rotation scenarios, and achieving higher bounding box regression accuracy and robustness.

4.4.2. Quantitative Comparison

Figure 7 illustrates the precision-recall (PR) curves for different hotspot defect types and PV arrays across various detection methods, with the corresponding average precision (AP) results provided in

Table 3.

For line-shaped hotspots, the proposed method demonstrates clear superiority, achieving an AP@0.1:0.5 of 0.4647, compared to 0.3843 for DiffusionDet with RRPN and 0.1069 for Faster R-CNN with RRPN. The PR curve in

Figure 7a shows that the proposed method effectively detects small line-shaped targets, even at low recall rates, while the performance of the other methods drops significantly under these conditions. This underscores the proposed method’s enhanced capability for modeling small-scale targets. For flocculant-shaped hotspots, the proposed method achieves an AP@0.1:0.5 of 0.7384, surpassing DiffusionDet with RRPN (0.6851) and Faster R-CNN with RRPN (0.6456). The PR curve in

Figure 7b indicates that DiffusionDet with RRPN performs second best but experiences a rapid decline in precision at high recall rates. In contrast, Faster R-CNN struggles significantly under these conditions. These results highlight the robustness of the proposed method in detecting targets with fuzzy boundaries and complex backgrounds. For strip-shaped hotspots, the proposed method achieves an AP@0.1:0.5 of 0.9117, outperforming DiffusionDet with RRPN (0.8120) and Faster R-CNN (0.8733). The PR curve in

Figure 7c confirms the stability of the proposed method under high recall conditions, demonstrating its ability to effectively capture the geometric features of strip-shaped targets. For facet-shaped hotspots, the proposed method achieves an AP@0.1:0.5 of 0.7507, significantly higher than DiffusionDet with RRPN (0.6663) and Faster R-CNN (0.2825). The PR curve in

Figure 7d shows that Faster R-CNN’s performance declines sharply when the recall rate exceeds 0.2, whereas the proposed method and DiffusionDet with RRPN maintain high precision across all recall ranges.

Table 3 summarizes the overall detection performance, showing that the proposed method achieves an average AP@0.1:0.5 of 0.7164, outperforming DiffusionDet with RRPN (0.6523) and Faster R-CNN (0.4618). Additionally, the proposed method achieves an AP@0.5:0.9 of 0.3986, further demonstrating its robustness under stricter IoU conditions, compared to DiffusionDet with RRPN (0.3447) and Faster R-CNN (0.2402). These results emphasize the proposed method’s balanced performance across multiple target types, excelling in small target detection, handling complex backgrounds, and accommodating diverse target shapes.

For PV arrays, DiffusionDet with RRPN fails to detect array regions, leaving the comparison to the proposed method and Faster R-CNN. The proposed method achieves an AP@0.5:0.9 of 0.9300, far exceeding Faster R-CNN’s 0.7782. These advantages are primarily due to the anchor-free diffusion mechanism and the sensitivity of the independent detection heads to angular learning, enabling precise detection of rotated PV arrays across complex backgrounds.

The model volume and inference efficiency are compared in

Table 4. DiffusionDet with RRPN has the lowest parameter number, while Faster R-CNN with RRPN contains 85.817M parameters. The proposed method has the highest parameter number at 111.8674M, primarily due to the integration of a more complex diffusion mechanism and independent detection heads. Despite this, the increased parameters contribute to enhanced detection performance. In terms of inference speed, DiffusionDet with RRPN achieves the highest FPS at 19, followed closely by the proposed method at 18 FPS, with Faster R-CNN lagging significantly at 12 FPS. These results demonstrate that the proposed method delivers nearly the same inference efficiency as DiffusionDet with RRPN while achieving substantially better detection performance, significantly surpassing Faster R-CNN.

In conclusion, the proposed method strikes a balance between moderate increases in parameter number, efficient inference speed, and superior detection performance. It outperforms comparative methods across all evaluation metrics, particularly in detecting small targets, handling diverse rotations, and achieving high regression precision under strict IoU thresholds.

5. Discussion

The proposed method effectively addresses the challenges of detecting hotspot defects and PV arrays under varying conditions. Compared to Faster R-CNN with RRPN and DiffusionDet with RRPN, the model demonstrates superior capability in detecting small-scale, rotated, and morphologically diverse targets, particularly in scenarios with complex backgrounds. The integration of diffusion-based rotated bounding boxes enhances sensitivity to angular variations, which is critical for accurate PV array detection. Additionally, the incorporation of the inside-awareness loss function in the defect branch effectively captures the intrinsic relationship between PV arrays and defects, significantly improving detection robustness. Our findings build on prior advancements in PV system defect detection, while extending the state of the art through the adoption of anchor-free mechanisms and a dual-branch structure. The model’s high inference speed and efficient parameter utilization further highlight its potential for real-time industrial deployment. However, there remains certain limitations, such as the need for larger datasets to improve generalization across diverse environmental conditions. In the future research, we will focus on integrating temporal data from video sequences to improve temporal consistency and expanding the model’s adaptability to novel defect types. Moreover, reducing computational overhead without compromising detection precision remains a promising direction for further exploration.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a novel dual-branch detection framework for PV array and hotspot defect detection. By leveraging anchor-free diffusion mechanisms and an inside-awareness loss function, the proposed model effectively addresses key challenges, including small target sizes, diverse rotation angles, and complex backgrounds. Compared to baseline methods, it consistently achieves superior precision, recall, and robustness across various scenarios. The findings underscore the model’s potential for real-time applications in diverse PV monitoring environments, representing a significant advancement in automated solar energy management.

Author Contributions

Methodology, software, writing—original draft preparation, Ruide Li; writing—review and editing, supervision, Wenjun Yan, validation, Chaoqun Xia.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Key Research and Development Projects of “Vanguard” and “Leading Goose” in Zhejiang Province under Grant 2023C01129.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In this section you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Čabo, F.G.; Marinić-Kragić, I.; Garma, T.; Nižetić, S. Development of thermo-electrical model of photovoltaic panel under hot-spot conditions with experimental validation. Energy 2021, 230, 120785. [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Yang, R.; He, Y.; Wang, F.; Huang, S. Nondestructive inspection, testing and evaluation for Si-based, thin film and multi-junction solar cells: An overview. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 78, 1117–1151. [CrossRef]

- Shengxue, T.; Yue, X.; Li, C.; Xiao, S.; Fang, Y. STUDY ON SUPPRESSING STRATEGY OF HOT SPOT IN SOLAR CELL SERIES. Acta Energiae Solaris Sinica 2022, 43, 226.

- Michail, A.; Livera, A.; Tziolis, G.; Candás, J.L.C.; Fernandez, A.; Yudego, E.A.; Martínez, D.F.; Antonopoulos, A.; Tripolitsiotis, A.; Partsinevelos, P.; et al. A comprehensive review of unmanned aerial vehicle-based approaches to support photovoltaic plant diagnosis. Heliyon 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lofstad-Lie, V.; Marstein, E.S.; Simonsen, A.; Skauli, T. Cost-Effective Flight Strategy for Aerial Thermography Inspection of Photovoltaic Power Plants. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2022, 12, 1543–1549. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.K.V.; Aghaei, M.; Rüther, R. Automatic Inspection of Photovoltaic Power Plants Using Aerial Infrared Thermography: A Review. Energies 2022, 15. [CrossRef]

- Dotenco, S.; Dalsass, M.; Winkler, L.; Würzner, T.; Brabec, C.; Maier, A.; Gallwitz, F. Automatic detection and analysis of photovoltaic modules in aerial infrared imagery. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 2016, pp. 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Su, J.; Li, X. Hot spots detection of operating PV arrays through IR thermal image using method based on curve fitting of gray histogram. In Proceedings of the Matec web of conferences. EDP Sciences, 2016, Vol. 61, p. 06017.

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2016; Leibe, B.; Matas, J.; Sebe, N.; Welling, M., Eds., Cham, 2016; pp. 21–37.

- Terven, J.; Córdova-Esparza, D.M.; Romero-González, J.A. A Comprehensive Review of YOLO Architectures in Computer Vision: From YOLOv1 to YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 2023, 5, 1680–1716. [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; Changyu, L.; Hogan, A.; Diaconu, L.; Ingham, F.; Poznanski, J.; Fang, J.; Yu, L.; et al. ultralytics/yolov5: v3. 1-bug fixes and performance improvements. Zenodo 2020.

- Wu, X.; Hao, X. SK-FRCNN: A Fault Detection Method for Hot Spots on Photovoltaic Panels. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 121379–121386. [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Li, J.; Ma, X.; Sun, S.; Tian, Z.; Li, T.; Hou, Y. A Photovoltaic Hot-Spot Fault Detection Network for Aerial Images Based on Progressive Transfer Learning and Multiscale Feature Fusion. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Shen, W.; Xu, W.S. Hotspot defect detection for photovoltaic modules under complex backgrounds. Multimedia systems 2023, 29, 3245–3258. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Wang, X.; Guan, A.H. Deeplab-YOLO: a method for detecting hot-spot defects in infrared image PV panels by combining segmentation and detection. Journal of Real-Time Image Processing 2024, 21, 52.1–52.11. [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Hao, S.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Sun, S.; Yang, C. APM²Det: A Photovoltaic Hot-Spot Fault Detection Network Based on Angle Perception and Model Migration. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2024, 31, 2938–2946. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yan, P.; Yao, C.; Xiao, B.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, R. A lightweight joint metric detection approach on YOLO for hot spots in photovoltaic modules. Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy 2024, 16, 053503, [https://pubs.aip.org/aip/jrse/article-pdf/doi/10.1063/5.0232136/20217699/053503_1_5.0232136.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Q.; Lin, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yan, J. Enhancing PV panel segmentation in remote sensing images with constraint refinement modules. Applied Energy 2023, 350, 121757. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhuang, Z.; Tan, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Lin, Z.; Shang, W.L.; Zhang, H.; Yan, J. Accurate and generalizable photovoltaic panel segmentation using deep learning for imbalanced datasets. Renewable Energy 2023, 219, 119471. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Sun, P.; Song, Y.; Luo, P. DiffusionDet: Diffusion Model for Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), October 2023, pp. 19830–19843.

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H.; Ranzato, M.; Hadsell, R.; Balcan, M.; Lin, H., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020, Vol. 33, pp. 6840–6851.

- Song, J.; Meng, C.; Ermon, S. Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models, 2022, [arXiv:cs.LG/2010.02502].

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis With Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2022, pp. 10684–10695.

- Karras, T.; Aittala, M.; Aila, T.; Laine, S. Elucidating the Design Space of Diffusion-Based Generative Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave, D.; Cho, K.; Oh, A., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2022, Vol. 35, pp. 26565–26577.

- Ding, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Z.J. CCDM: Continuous Conditional Diffusion Models for Image Generation, 2024, [arXiv:cs.CV/2405.03546].

- Wyatt, J.; Leach, A.; Schmon, S.M.; Willcocks, C.G. AnoDDPM: Anomaly Detection With Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models Using Simplex Noise. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) Workshops, June 2022, pp. 650–656.

- Nag, S.; Zhu, X.; Deng, J.; Song, Y.Z.; Xiang, T. DiffTAD: Temporal Action Detection with Proposal Denoising Diffusion. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), October 2023, pp. 10362–10374.

- Shi, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wei, P.; Xian, X.; Chen, T.; Lin, L. Diff-Mosaic: Augmenting Realistic Representations in Infrared Small Target Detection via Diffusion Prior. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Hou, J.; Yao, T.; Liang, D.; Liu, Z.; Zou, Z.; Ye, X.; Cheng, J.; Bai, X. Diffusion-Based 3D Object Detection with Random Boxes. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Ma, Z.; Zheng, W.; Zha, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Ji, R., Eds., Singapore, 2024; pp. 28–40.

- Rezatofighi, H.; Tsoi, N.; Gwak, J.; Sadeghian, A.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. Generalized Intersection Over Union: A Metric and a Loss for Bounding Box Regression. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), June 2019.

- Russell, B.C.; Torralba, A.; Murphy, K.P.; Freeman, W.T. LabelMe: A Database and Web-Based Tool for Image Annotation. International Journal of Computer Vision 2008, 77. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The framework of the proposed dual-branch photovoltaic diagnostic network.

Figure 1.

The framework of the proposed dual-branch photovoltaic diagnostic network.

Figure 2.

The diffusion process and RROI pooler of the array branch. The rotation angle is determined by rotating the rectangle counterclockwise, aligning the longer side w with the x-axis for the first time.

Figure 2.

The diffusion process and RROI pooler of the array branch. The rotation angle is determined by rotating the rectangle counterclockwise, aligning the longer side w with the x-axis for the first time.

Figure 3.

Diagrams of the proposed inside awareness loss. (

a) Convex hull of two rectangles. IoU, IIoU, UoC, and

defined by (

6) for cases of (

b) proposal box

inside the array box

, (

c) proposal box

outside the array box

, (

d) proposal box

interacts with the array box

. A larger IoU, IIoU, UoC indicates better instances, while a larger

means worse cases.

Figure 3.

Diagrams of the proposed inside awareness loss. (

a) Convex hull of two rectangles. IoU, IIoU, UoC, and

defined by (

6) for cases of (

b) proposal box

inside the array box

, (

c) proposal box

outside the array box

, (

d) proposal box

interacts with the array box

. A larger IoU, IIoU, UoC indicates better instances, while a larger

means worse cases.

Figure 4.

Representative photovoltaic (PV) array and hotspot defect detection results are shown for different PV power station scenarios, including water, roof, and ground installations. The images illustrate various hotspot defect shapes: (a1)-(a3) line-shaped hotspots, (b2)-(b3) flocculant-shape hotspots, (c1)-(c3) strip-shaped hotspots, and (d1)-(d3) facet-shaped hotspots. The percentage around the text label represents the detection score.

Figure 4.

Representative photovoltaic (PV) array and hotspot defect detection results are shown for different PV power station scenarios, including water, roof, and ground installations. The images illustrate various hotspot defect shapes: (a1)-(a3) line-shaped hotspots, (b2)-(b3) flocculant-shape hotspots, (c1)-(c3) strip-shaped hotspots, and (d1)-(d3) facet-shaped hotspots. The percentage around the text label represents the detection score.

Figure 5.

Precision-recall (PR) curves of different IoU thresholds derived by the proposed detection method. (a) PR curves of the line-shaped defect. (b) PR curves of the flocculant-shaped defect. (c) PR curves of the strip-shaped defect. (d) PR curves of the facet-shaped defect. (e) PR curves of the PV array. AP indicates the area under the PR curve, and mAP indicates the average AP results for different IoU thresholds.

Figure 5.

Precision-recall (PR) curves of different IoU thresholds derived by the proposed detection method. (a) PR curves of the line-shaped defect. (b) PR curves of the flocculant-shaped defect. (c) PR curves of the strip-shaped defect. (d) PR curves of the facet-shaped defect. (e) PR curves of the PV array. AP indicates the area under the PR curve, and mAP indicates the average AP results for different IoU thresholds.

Figure 6.

Visualization comparison for different models. The four rows demonstrate line-shaped, flocculant-shaped, strip-shaped, and facet-shaped hotspot detection performance, successively.

Figure 6.

Visualization comparison for different models. The four rows demonstrate line-shaped, flocculant-shaped, strip-shaped, and facet-shaped hotspot detection performance, successively.

Figure 7.

Precision-recall (PR) curves of different objects with specific IoU thresholds derived by the different detection models. (a) PR curves of the line-shaped defect. (b) PR curves of the flocculant-shaped defect. (c) PR curves of the strip-shaped defect. (d) PR curves of the facet-shaped defect. (e) PR curves of the PV array. AP indicates the area under the PR curve.

Figure 7.

Precision-recall (PR) curves of different objects with specific IoU thresholds derived by the different detection models. (a) PR curves of the line-shaped defect. (b) PR curves of the flocculant-shaped defect. (c) PR curves of the strip-shaped defect. (d) PR curves of the facet-shaped defect. (e) PR curves of the PV array. AP indicates the area under the PR curve.

Table 1.

The annotation information of the dataset.

Table 1.

The annotation information of the dataset.

| Category |

Description |

#Instances |

Size |

Rotation*

|

| Line |

Hotspot caused by PV module shielding, bubble, delamination, dirt, gate line fracture. |

2283 |

Small target within or

|

- |

| Flocculant |

Hotspot caused by PV module occlusion, dirt, rupture |

3310 |

Small target within

|

- |

| Strip |

Hotspot caused by PV module occlusion, dirt, diode failure, bracket deformation |

3377 |

Small target within or

|

- |

| Facet |

Hotspot caused by PV module fragmentation, module failure, module disconnected |

168 |

Small target within or

|

- |

| Array |

A complete power-generating unit, consisting of any number of PV modules and panels |

32960 |

Rotated rectangles with various sizes |

|

Table 2.

Precision and recall metrics of different categories for the proposed detection method.

Table 2.

Precision and recall metrics of different categories for the proposed detection method.

| Categories |

Precision@0.1 |

Precision@0.5 |

Recall@0.1 |

Recall@0.5 |

AP@0.1:0.5 |

AP@0.5:0.9 |

| Line Hotspot |

0.6091 |

0.5556 |

0.4900 |

0.4400 |

0.4647 |

0.1650 |

| Flo Hotspot |

0.7873 |

0.7302 |

0.7700 |

0.7200 |

0.7384 |

0.3697 |

| Strip Hotspot |

0.9219 |

0.9325 |

0.9000 |

0.8900 |

0.9117 |

0.5665 |

| Facet Hotspot |

0.8333 |

0.8333 |

0.6600 |

0.6600 |

0.7507 |

0.4930 |

| Average |

0.7879 |

0.7050 |

0.7629 |

0.6775 |

0.7164 |

0.3986 |

| PV Array |

0.9754 |

0.9671 |

0.9700 |

0.9600 |

0.9773 |

0.9300 |

Table 3.

Comparison of performance metrics for different models and categories.

Table 3.

Comparison of performance metrics for different models and categories.

| Categories |

Models |

AP@0.1:0.5 |

AP@0.5:0.9 |

|

Faster RCNN with RRPN |

0.1069 |

0.0114 |

| Line Hotspot |

DiffusionDet with RRPN |

0.3843 |

0.1242 |

| |

Ours |

0.4647 |

0.1650 |

|

Faster RCNN with RRPN |

0.6456 |

0.3091 |

| Flo Hotspot |

DiffusionDet with RRPN |

0.6851 |

0.3336 |

| |

Ours |

0.7384 |

0.3697 |

|

Faster RCNN with RRPN |

0.8733 |

0.5360 |

| Strip Hotspot |

DiffusionDet with RRPN |

0.8120 |

0.4921 |

| |

Ours |

0.9117 |

0.5665 |

|

Faster RCNN with RRPN |

0.2825 |

0.1495 |

| Facet Hotspot |

DiffusionDet with RRPN |

0.6663 |

0.3365 |

| |

Ours |

0.7507 |

0.4930 |

|

Faster RCNN with RRPN |

0.4618 |

0.2402 |

| Average |

DiffusionDet with RRPN |

0.6523 |

0.3447 |

| |

Ours |

0.7164 |

0.3986 |

|

Faster RCNN with RRPN |

0.8581 |

0.7782 |

| PV Array |

DiffusionDet with RRPN |

/ |

/ |

| |

Ours |

0.9773 |

0.9300 |

Table 4.

Comparison of model parameters, inference time, and FPS.

Table 4.

Comparison of model parameters, inference time, and FPS.

| Models |

Parameters (M) |

Time (s) |

FPS |

| Faster RCNN with RRPN |

85.817 |

0.0833 |

12 |

| DiffusionDet with RRPN |

70.0398 |

0.0513 |

19 |

| Ours |

111.8674 |

0.0571 |

18 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).