1. Introduction

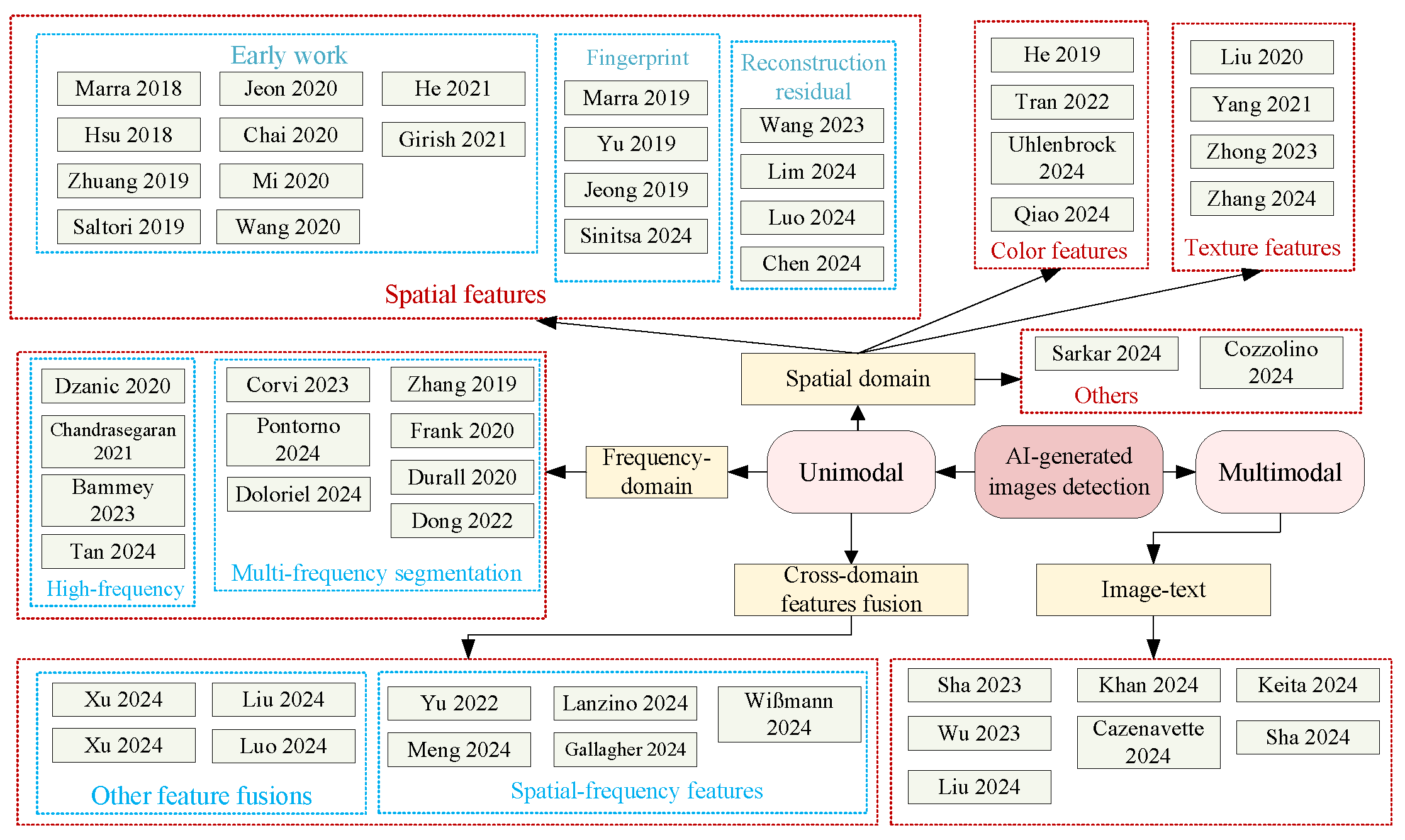

In recent years, the rapid development of technology has significantly improved AI-created visual content techniques in terms of visual quality, semantic complexity, and operational efficiency. People can easily obtain high-quality images and videos by simply clicking a mouse or entering a text description. However, this unprecedented technology has also raised concerns about the spread of false information. Therefore, developing effective tools for AI-created visual content detection has become increasingly important. In this survey, we focus on deep learning-based AI-generated images detection techniques and deepfake detection technologies. AI-created visual content detection techniques are categorized based on different methods, as shown in

Figure 1.

The current AI-generated images detection methods can be primarily divided into two categories: image classification tasks and image attribution tasks. Image classification tasks treat AI-generated images detection as a binary classification problem, where the detector learns to differentiate between real and fake images by identifying distinct features, thus outputting different labels to detect fake images. Image attribution tasks, on the other hand, leverage unique fingerprints and other characteristics specific to different generative models, matching them with the input image features to identify the generating model of fake images. Some studies also explore which aspects are more beneficial for detecting AI-generated images. Currently, most AI-generated images detection methods are based on image classification tasks. Starting with the simplest classifiers, the field has progressed to using deep neural networks (DNNs), convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and other neural networks for AI-generated images detection by incorporating spatial, frequency, texture, and other features. Later advancements involved cross-domain feature fusion and the use of image-text methods. AI-generated images detection technology has rapidly developed in recent years. Even though high-quality generated images may be indistinguishable from real ones to the human eye, statistical characteristics of the images still exhibit differences from real images. These differences enable detectors to distinguish between real and fake images. With the development of deep learning techniques, computers are now capable of learning these differences and performing effective detection.

In AI-created visual content technologies, deepfake technology allows the amazingly accurate modification of faces, sounds, or whole scenarios. This includes modifying facial expressions, swapping faces, adjusting lip-syncing in films, and more [

1]. In 2017, a Reddit user named "Deepfake" used deep learning techniques to create and spread a pornographic video of Gal Gadot, marking the beginning of this technology’s tremendous rise. In 2022, a video of Ukrainian President Zelensky urging soldiers to surrender went viral, with over 250,000 viewers. In 2024, South Korea experienced a surge in deepfake-related sexual crimes, with potentially up to 220,000 victims, including many adolescent students and even minors. According to a security report by QAX in 2024, AI-based deepfake frauds surged 30 times in 2023, and AI-driven phishing emails increased 10 times. While deepfake technology does have some positive applications, its abuse has posed significant threats to national security, social media, and public trust. To address these challenges, researchers have focused on deepfake detection tasks, improving robustness and generalizability, and developing advanced methods. Among these, deep learning-based approaches have shown clear superiority in detection performance, so this survey primarily focuses on deep learning-based methods.

In the past few years, several surveys on AI-generated images detection technologies have been published. Hu et al. [

2] outlined the mainstream frameworks of neural networks, briefly introduced the applications of deep learning in generative image and natural image forensics, and finally pointed out the challenges and future prospects of deep learning in this field. Deng et al. [

3] studied research on defending against AI-generated visual media attacks. They summarized existing attack methods and defense strategies, and within a unified passive and active framework, reviewed mainstream defense-related tasks, evaluating their robustness and fairness. Additionally, they summarized commonly used evaluation datasets, standards, and metrics, but noted that there is limited research on AI-generated images detection methods. Guo et al. [

4] categorized AI-generated images into active forensics and passive forensics, discussing the superiority of active forensics over passive forensics. However, most generative models do not embed watermarks in generated images, making this method highly limited. Lin et al. [

5] conducted an extensive survey on AI-generated content detection, but the AI-generated images detection methods they reviewed were all from 2023, without analyzing or reviewing earlier methods. This survey briefly introduces generative models used for image generation, provides a comprehensive review of AI-generated images detection methods, and compares their advantages and disadvantages.

Several recent reviews have systematically summarized the existing deepfake detection techniques. Rana et al. [

6] analyzed 112 relevant papers and categorized their methods into four types: deep learning-based techniques, classical machine learning-based methods, statistical techniques, and blockchain-based techniques. However, this paper does not delve into future trends. Seow et al. [

7] provided a detailed introduction to deepfake generation, including the types of deepfakes and some available forgery tools. They reviewed existing deepfake detection work from two perspectives: traditional methods and deep learning-based methods. Gong and Li [

8] grouped the surveyed methods into four categories: traditional CNN-based detection, CNN backbone with semi-supervised detection, transformer-based detection, and biological signal detection, according to their feature extraction methods and network architectures. Heidari et al. [

9] focused on deep learning-based detection methods, providing a detailed study of four applications: video detection, image detection, audio detection, and hybrid multimedia detection. They also highlighted several unresolved issues that require further attention. Sandotra and Arora [

10] focused on the generation of deepfakes, covering topics such as face manipulation methods, open-source tools, and so on. It classified forgery detection methods from the perspectives of space, time, and frequency features. Kaur et al. [

11] provided a detailed classification of detection methods while discussing some challenges in the field, which are summarized into three categories: data challenges, training challenges, and reliability challenges. They also highlighted some of the main differences between deepfake image detection and video detection. Finally, it offered an outlook on future opportunities. The above reviews have conducted an in-depth analysis of past work, but none of them summarize detection methods from the perspective of the features used. Therefore, this review will start with feature selection and provide a discussion and analysis of existing deepfake detection algorithms.

The remainder of this survey is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides the fundamentals of AI-generated images detection and deepfake detection, including datasets, basic detection frameworks, evaluation metrics, and more.

Section 3 presents the state-of-the-art methods in AI-generated images detection.

Section 4 discusses the state-of-the-art deepfake detection technologies, with a focus on the differences in feature selection approaches.

Section 5 offers future research directions of AI-created visual content detection and conclusions.

4. Deepfake Detection Based on Feature Selection

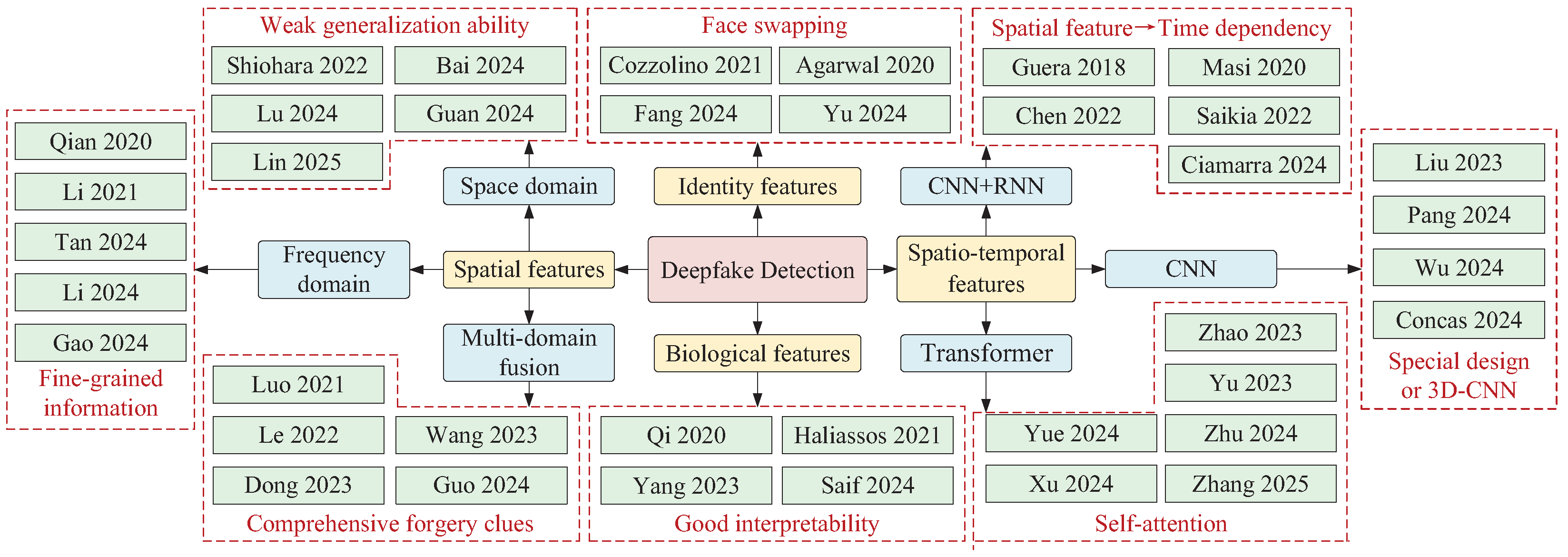

Deepfake detection methods can be broadly classified into four categories based on the feature information utilized, including methods based on spatial features, spatiotemporal features, biological features, and identity features. Among these, spatial features and spatio-temporal features can be considered general features, while biological features and identity features are considered special features, typically requiring specialized network architectures for extraction. Therefore, this section will present an article review in these four directions, and we have also summarized and organized the selected articles, as shown in

Figure 7.

4.1. Spatial Features-Based

The initial deepfake detection methods primarily relied on spatial features, including texture features, tampering artifacts, etc. These methods focused on single-frame analysis, achieving simple and effective detection by extracting forgery clues from different domains. Based on the source of information, these methods can be categorized into space domain-based, frequency domain-based, and multi-domain fusion approaches.

4.1.1. Space Domain Information-Based

In the field of deepfake detection, the space domain is a commonly used source of information. Many researchers have improved model performance by designing network architectures, applying image preprocessing techniques, or leveraging specific spatial inconsistencies. As an earlier method, Afchar et al. [

144] used a shallow convolutional network to extract mid-level features from images for forgery detection and achieved video-level detection through image aggregation. Li et al. [

145] proposed Face X-ray, which detects the blending boundary in forged faces through synthetic data training. It performs classification while also locating the blending areas, but this approach does not apply to completely synthesized fake images. Bonettini et al. [

146] used EfficientNetB4 as the backbone network and incorporated attention layers and siamese training mechanisms, highlighting the role of these mechanisms through ablation studies.

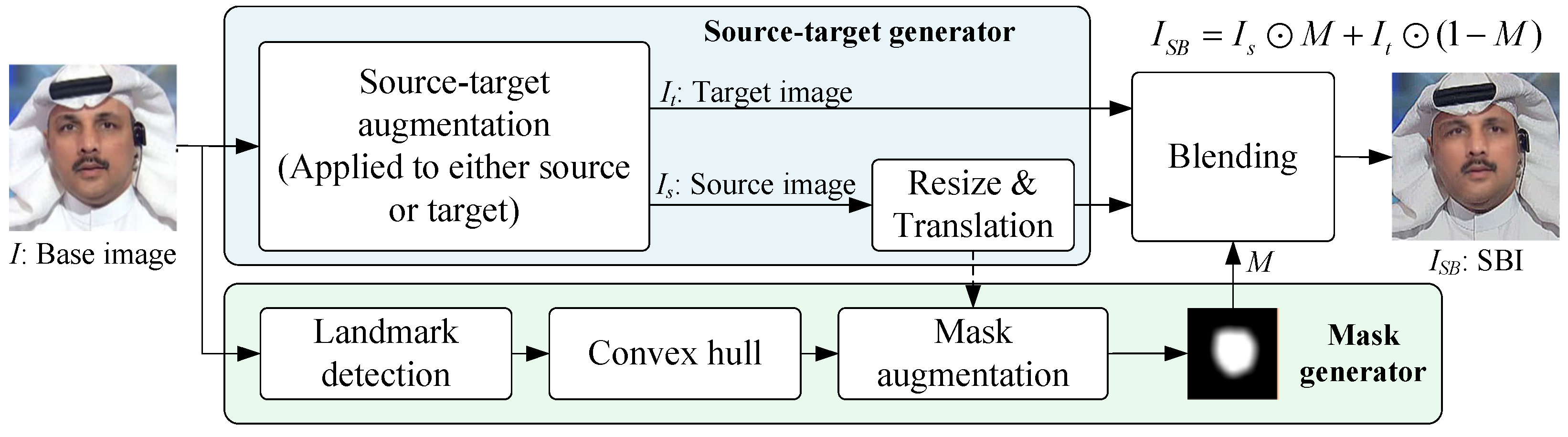

To address the issue of limited generalization due to the commonly used fake data, researchers have proposed the idea of synthetic data, which helps make the trained models more generalizable. Shiohara and Yamasaki [

147] proposed self-blended images (SBI) to prevent the model from overfitting to specific forgery methods. By using a data synthesis strategy to reproduce general forgery artifacts, they improved the model’s generalization ability. The general synthesis process of SBI is shown in

Figure 8. The basic idea is to generate the target image and the pseudo source image from the base image, and then blend the two images using a face mask, thereby creating general visual artifacts. Chen et al. [

148] also employed data synthesis methods, but they enriched the diversity of synthetic data by introducing multi-configuration strategies and used adversarial training to enable the model to learn more robust feature representations. Lin et al. [

149] designed self-shifted blending images to simply fuse temporal artifacts, searching for a suitable augmentation scheme during training. Their curriculum learning-based training strategy further enhanced model performance. Guan et al. [

150] introduced a gradient regularization term into the original loss function to reduce the model’s sensitivity to texture features. The new loss function improved the model’s robustness to shallow feature statistical perturbations and could be combined with existing backbone networks or methods to further enhance detection performance.

Additionally, Gao et al. [

151] proposed separating texture and artifact information in the features and performing face and background separation using estimated masks obtained through self-supervised learning strategies. This allowed for the extraction of more detailed texture information, which was then combined with artifacts for detection. Lu et al. [

152] proposed a long-distance attention mechanism based on fine-grained classification and designed spatial and temporal attention modules to obtain local region attention maps from single and consecutive frames. To address the generalization issue, Zheng et al. [

153] combined unsupervised-supervised contrastive learning for deepfake detection. They mined features from both original and data-augmented images, performed multi-scale fusion, and applied contrastive loss constraints between individual samples and diverse class features, achieving effective and stable detection. Since forgeries disrupt the consistency of regional noise, Bai et al. [

154] proposed a method that leverages the noise pattern differences between the face and background regions. They performed noise enhancement and multi-scale integration to effectively detect forged images. Ma et al. [

155] utilized incremental learning strategies to improve the model’s generalization performance with limited samples and combined human perception saliency with self-attention to highlight important regions. Lu et al. [

156] designed a multi-scale texture feature extraction module using central difference convolution, effectively enhancing the quality of texture features. They also introduced region-specific separable self-consistency loss to constrain the representation learning of different regions and emphasize important areas.

Table 11 summarizes these methods from three aspects: key idea, backbone, and dataset.

4.1.2. Frequency Domain Information-Based

Space domain-based detection methods can achieve good detection performance; however, when subjected to common attacks such as noise or compression, the forgery clues become harder to detect. Additionally, the traces left by different forgery methods vary, which limits further improvement in generalization performance. On the other hand, the frequency domain information of an image, especially high-frequency components, contains edges and other fine details that are more resilient to attacks. Furthermore, different forgery methods tend to generate unnatural artifacts in the frequency domain, which makes it possible to detect forgery traces that are difficult to identify in the space domain. Therefore, incorporating frequency domain information can enhance the robustness and generalization of the detection model.

In these methods, common frequency domain information extraction techniques include FFT, DCT, and discrete wavelet transform (DWT). Peng et al. [

158] designed a high-frequency residual extraction module based on the Laplacian pyramid, utilizing the high-frequency components of shallow features to extract visual artifacts. Qian et al. [

159] used DCT for domain transformation and integrated frequency-aware decomposition images and local frequency statistics through a dual-stream collaborative learning framework to mine forgery clues. Li et al. [

160] restructured DCT coefficients across different frequency bands while preserving the original spatial relationships, allowing the use of convolutional networks for frequency feature extraction. They also employed a single-center loss to compress intra-class variations and expand inter-class differences. Gao et al. [

161] addressed the difficulty of detecting compressed data by proposing a high-frequency enhancement framework that integrates comprehensive frequency-domain information from block-wise DCT and DWT. Using a two-stage cross-fusion strategy, they effectively merged information and achieved high accuracy on highly compressed data.To address the limitation of self-attention in capturing subtle clues, Miao et al. [

162] introduced the central difference operators to extract fine-grained feature details and used DWT to supplement local high-frequency information, achieving strong accuracy and robustness. To supplement fine-grained information in transformer, Li et al. [

163] embedded wavelet transforms into self-attention and designed down-sampling strategies for information enhancement across stages. Through optimal data augmentation, they effectively improved generalization performance. Hasanaath et al. [

164] extracted discriminative generic features from self-blended images using DWT and fed them into a CNN for deepfake classification. Zhao et al. [

165] introduced an adaptive fourier neural operator to learn frequency-domain forgery clues and applied an efficient attention mechanism to enhance detailed information while reducing the computation.

A comparison of these methods is shown in

Table 12.

Table 12 describes the methods from three aspects: frequency domain information extraction methods, backbone and datasets.

4.1.3. Multi-Domain Information Fusion-Based

To leverage complementary information from different domains, many researchers have fused multi-domain features to obtain more comprehensive feature representations.

Table 13 compares the multi-domain information fusion-based methods in terms of information sources, fusion methods, backbone, and datasets.

Wang et al. [

166] calculated the residual between the original grayscale image and the low-frequency components of the DWT to obtain the mid-high frequency image, which was then concatenated with the RGB image and fed into a convolution network for classification. Wang et al. [

167] integrated deep-frequency domain information extracted from residual maps reflecting facial edge information with wavelet frequency domain and RGB domain information. Zhou et al. [

168] fused multi-scale RGB features with frequency-domain-aware features based on FFT. Le and Woo [

169] used attention distillation to transfer high-frequency components learned by a teacher model trained on high-quality data to a student model, enhancing feature discrimination under low-quality data conditions. To restore the model’s attention to compressed artifacts, Wang et al. [

170] designed a spatial-frequency feature fusion architecture and also employed knowledge distillation to transfer feature representations from a teacher model to a student model. Most existing methods focus on improving traditional convolutional backbones, but Guo et al. [

171] designed a new space-frequency interactive convolution module that integrates space domain information and high-frequency information through interaction, resulting in more refined feature representations.

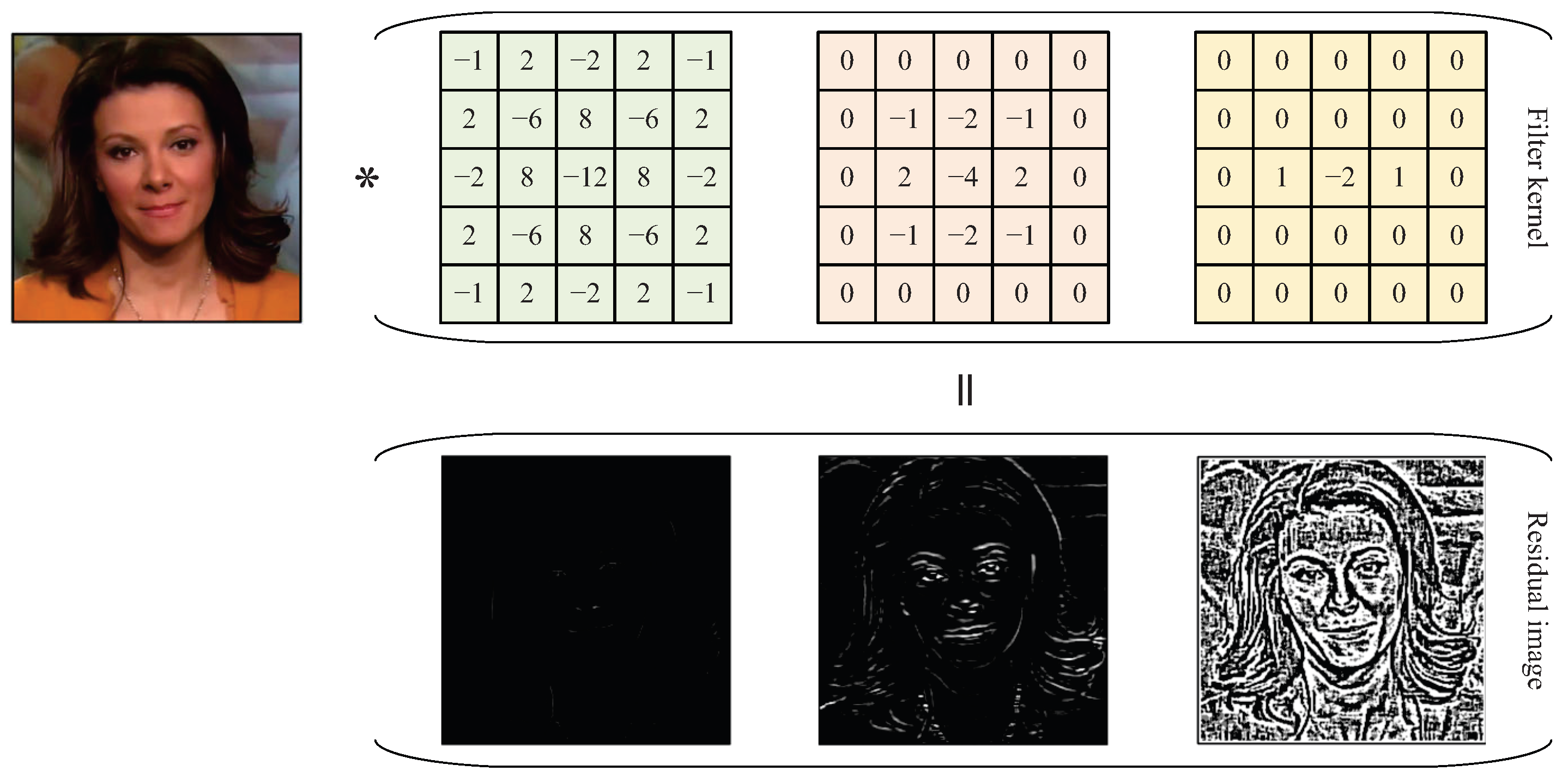

High-pass filters in spatial rich model (SRM) can extract high-frequency noise from images, removing color textures and revealing the differences between the real and forgery regions. The three commonly used filtering kernels and their resulting noise residual images are shown in

Figure 9. Based on this observation, Luo et al. [

172] used SRM to extract multi-scale high-frequency residuals as an information branch and generated residual attention maps to highlight forgery clues in the RGB branch features. Their cross-modal fusion achieved efficient utilization of the dual-branch information. Zhang et al. [

173] also fused high-frequency noise with spatial texture features and used local attention to enhance forgery traces. Fei et al. [

174] supplemented noise features while calculating first and second order local anomaly maps in the RGB branch, magnifying and learning the local anomaly information of forged images for more generalizable detection. Dong et al. [

175] treated SRM high-frequency noise as data augmentation and employed supervised contrastive learning to minimize the positive pair distance, improving the generalization performance of the model.

4.2. Spatio-Temporal Features-Based

The consecutive frames of an original video have natural consistency, but deepfake videos are composed of individual forged images linked together, which disrupts the original spatio-temporal consistency and introduces forgery traces in the temporal domain. Spatial feature-based detection methods fail to account for this disruption, making them unsuitable for video-level detection. As a result, some researchers have started designing frameworks for extracting spatio-temporal features. The backbone networks used in these methods mainly include CNN, recurrent neural networks (RNN), and transformer, so these methods can be divided into three categories: CNN-based, CNN+RNN-based, and transformer-based.

4.2.1. CNN-Based

CNN-based methods typically involve special designs for feature extraction or the use of 3D CNNs. Liu et al. [

176] integrated RGB domain and frequency domain information, utilizing locally sensitive regions to enhance forgery features, and employed a 3D CNN to supplement temporal domain information. Concas et al. [

177] proposed an innovative method for extracting forgery artifacts by performing facial quality estimation on the face region of single-frame or consecutive-frame images and generating a quality feature matrix that is input into a CNN for forgery detection. Existing methods tend to capture spatio-temporal information with fixed time steps, rarely focusing on the extraction of dynamic spatio-temporal inconsistencies. Pang et al. [

178] designed a video sampling strategy, BGS, which used different sampling rates to obtain multiple video frame sets and extracted short-term and long-term spatio-temporal information in subsequent networks, enabling full utilization of forgery clues. Zhang et al. [

179] proposed a frame sampling strategy with temporal diversification and used self-contrastive learning to extract short-term and long-term temporal artifacts, reducing the model’s sensitivity to binary labels. Yu et al. [

180] applied multi-path dynamic inconsistency magnification to multiple groups of sampled frames to extract local-consecutive fine-grained features, used graph convolution network (GCN) to obtain global temporal views across multiple groups and designed a domain alignment module to improve generalization performance.

To fill the gap in frequency domain spatio-temporal information for deepfake detection, Wang et al. [

181] proposed a frequency domain forgery clue augmentation strategy based on DCT. They first enhanced the high-frequency components of the DCT spectrum, then divided it into multiple blocks along the spatial dimension, replacing the original spectrum with the maximum response to reduce computational complexity. The attention map obtained from the frequency temporal attention module enhanced temporal clues. Wu et al. [

182] designed patch-wise decomposable DCT to extract finer-grained high-frequency clues and extracted comprehensive spatio-temporal representations of both RGB and frequency branches in stages. An interaction module was used to eliminate cross-modality feature inconsistencies, achieving effective feature fusion.

The state-of-the-art CNN-based deepfake detection methods are described in

Table 14.

Table 14 describes the methods from three aspects: improved methods, backbone, and dataset.

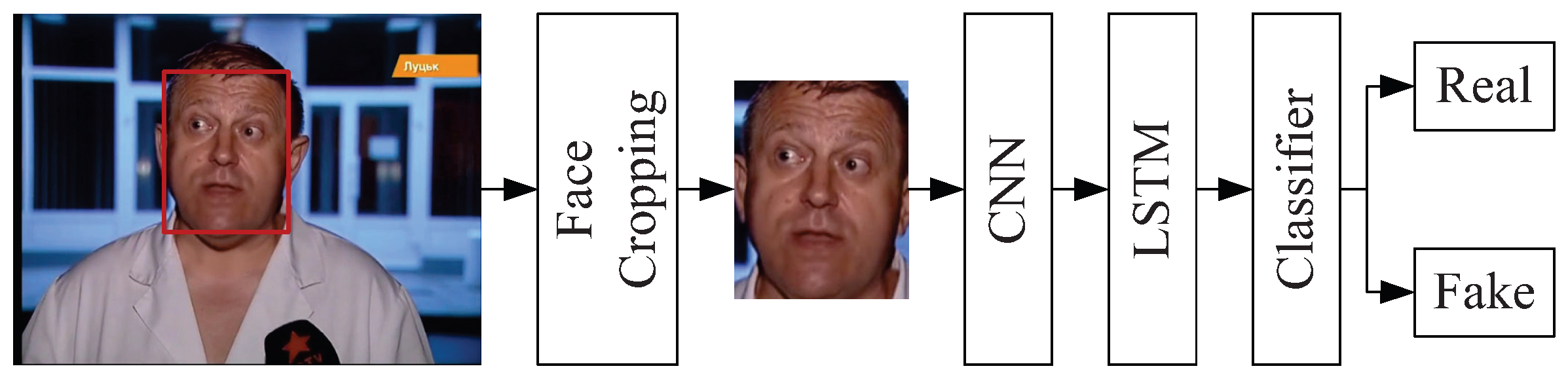

4.2.2. CNN+RNN-Based

Since CNNs are primarily used for extracting spatial information from images and are not effective at capturing temporal dependencies, applying RNNs for temporal modeling of the features extracted by CNNs has become an effective solution. RNNs, especially long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, are well-suited for modeling sequential data and capturing the temporal relationships between frames in video, which helps improve the detection of temporal inconsistencies in deepfake videos. By combining CNNs for spatial feature extraction with RNNs for temporal sequence modeling, such hybrid approaches can better leverage both spatial and temporal information for more accurate and robust deepfake detection.

The general process of using a CNN and RNN hybrid model for detection is shown in

Figure 10. In this process, the CNN extracts spatial features from the facial image, the RNN performs temporal modeling on the spatial features, and finally, classification is performed. Based on this process, Guera and Delp [

183] used InceptionV3 to extract frame features and input them into an LSTM to learn inter-frame inconsistencies, achieving video-level classification. Saikia et al. [

184] utilized optical flow from consecutive face frames and fed it into a hybrid model of CNN and LSTM to extract temporal information. Chen et al. [

185] introduced a spatio-temporal attention mechanism to enhance the temporal correlation between frames, and the augmented frames were input into Xception and ConvLSTM to extract spatial and temporal inconsistencies. K and M [

186] optimized network weights using the spotted hyena optimizer during the hybrid model training. Amerini and Caldelli [

187] used image prediction errors as inputs to incorporate temporal information; however, the increase in complexity led to a decrease in generalization ability. Masi et al. [

188] proposed a dual-stream network, with one branch extracting RGB features and the other using the laplacian of gaussian (LoG) operator to suppress facial visual content and extract high-frequency edge information. They also designed a new loss function based on the concept of one-class classifiers, which pulls positive samples closer while pushing negative samples further apart. Since deepfake videos often fail to preserve the inherent features left during the camera capture process, Ciamarra et al. [

189] used UprightNet to estimate camera orientation and generate surface frames. They leveraged temporal anomalies in these frames to detect forgery.

4.2.3. Transformer-Based

Transformer was first applied to natural language processing (NLP) tasks and achieved significant improvements [

190]. To extend their application to vision tasks, researchers designed the vision transformer (ViT) [

191] and swin transformer (SwinT) [

192], utilizing self-attention mechanisms to capture long-distance dependencies between different frames.

Given their powerful spatio-temporal modeling capabilities, many researchers have started applying these models to the field of deepfake detection. Yu et al. [

193] designed a multi-view modeling strategy based on transformer, where for multiple groups of consecutive frames, they first establish local spatio-temporal fusion features for each set and then connect them along the temporal channel to create global spatio-temporal fusion features. Huang and Zhang [

194] introduced an improved meta-learning approach to the spatio-temporal backbone, effectively enhancing generalization to unseen forgery methods. Zhao et al. [

195] decomposed the computation of self-attention, using a self-subtract mechanism to make the model focus more on inter-frame distortions based on feature residuals, thus reducing redundant information. Inspired by correlation propagation algorithms, they also designed a visualization algorithm to improve the interpretability of the transformer. Liu et al. [

196] used RGB images and motion flow to provide spatio-temporal information, modeling spatio-temporal feature connections with SwinT, and designed identity-decoupling attention to extract more general spatio-temporal feature representations that are independent of identity, thus effectively improving the model’s generalization ability. Yue et al. [

197] used UniformerV2 as the backbone to extract global features and leveraged local frequency dynamic information, generated region-of-interest (ROI) attention maps by local region alignment, guided the global features to extract more refined forgery clues. Zhu et al. [

198] employed knowledge distillation to transfer fine-grained spatial-frequency knowledge and spatio-temporal structural knowledge to the student model, effectively improving the model’s robustness to compression. Zhang et al. [

199] proposed a self-supervised learning approach to learn the natural consistency representation of real face videos and used the fact that the consistency of deepfake videos is disrupted to distinguish authenticity, designing corresponding natural consistency enhancement strategies to improve detection accuracy.

In addition to the aforementioned methods, some studies detect deepfakes by preprocessing data or utilizing special information. Choi et al. [

200] found temporal variations in the style latent vectors of generated facial videos, so they used a StyleGRU module to capture the style latent vector and established a style flow based on the differences for subsequent input. Tian et al. [

201] extracted rich and robust forgery information by leveraging the temporal variation of local and global lighting information and the dynamic spatio-temporal inconsistencies of intra-frame/inter-frame forgery cues. Tu et al. [

202] employed optical flow difference algorithms to locate key facial expression frames as input, which, compared to using the entire video sequence, improved accuracy while reducing training time by nearly 75%. To reduce computational requirements, Xu et al. [

203] designed a thumbnail layout method that transforms consecutive frames into a predefined layout while preserving the original spatio-temporal relationships. After embedding modified positions, it effectively utilizes the transformer to learn spatio-temporal information.

Finally, we summarize the transformer-based methods, including three aspects: whether transformer network architecture design, whether input design, and datasets were performed, as shown in

Table 15.

4.3. Biological Features-Based

The detection methods based on general features have achieved good performance, but they suffer from a significant lack of interpretability. In contrast, biological features, due to their inherent regularity, are much easier to interpret when subjected to forgery distortion. They provide a more intuitive understanding and align better with human cognition. Therefore, detection methods based on biological features represent a promising research direction.

Next, some methods based on biological features are introduced. Yang et al. [

204] trained a classifier using the head pose differences between real and fake facial images for deepfake detection. Haliassos et al. [

205] detected fakes by exploiting the high-level semantic irregularities of mouth movements in forged videos, and their method is robust to most data corruptions. Demir and Ciftci [

206] extensively analyzed features related to eyes and gaze, integrating visual, geometric, and temporal information, achieving superior detection results compared to methods based on a single biological feature. Peng et al. [

207] aggregated gaze direction, facial attributes, and texture information as spatio-temporal features to enhance the model’s ability to mine discriminative information. He et al. [

208] proposed GazeForensics, which incorporates MSE and applies constraints on general spatial features using 3D gaze features, achieving an accuracy of 0.9942 on the CDF dataset. Qi et al. [

209] introduced remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) into deepfake detection by observing the heart rate differences between real and fake facial videos, enhancing facial detail information with eulerian video magnification. Wu et al. [

210] extracted multi-region rPPG maps and highlighted significant information using local attention, with adjacent features input into a transformer to extract temporal knowledge. Yang et al. [

211] used CPPG signals to provide temporal information, supplementing spatial information through correlations between image pixels reflected by AR coefficients, extracting pixel-level discriminative features for forgery detection. Motion in deepfake videos often contains apparent errors; to capture this anomaly for forgery detection, Saif et al. [

212] constructed spatio-temporal graphs from facial landmarks in both single frames and across frames, using GCNs for detection, which is parameter-efficient and computationally effective. Zhang et al. [

213] used facial landmarks and face region information as nodes for GCNs, effectively identifying anomalous regions by analyzing both explicit and latent geometric relationships.

Table 16 describes these methods from three aspects: biosignal type, backbone, and datasets.

4.4. Identity Features-Based

Certain forgery methods can cause identity discrepancies in video subjects. Therefore, using identity-aware frameworks to extract such identity features can help leverage this anomaly information for deepfake detection. Agarwal et al. [

218] enabled the model to learn spatio-temporal biological behavioral features related to identity, distinguishing between different individuals and achieving face-swapping detection. Cozzolino et al. [

219] introduced adversarial training to generate feature vectors consistent with the input individual’s identity information, using a temporal ID network as a discriminator for identity recognition. Ramachandran et al. [

220] trained face recognition models with multiple loss functions to extract identity features. To address the identity representation bias in the extracted features, Fang et al. [

221] designed a bias rectification module and implemented attention-based feature fusion, also utilizing the inconsistency between reference-query images. Additionally, Fang et al. [

222] proposed a knowledge distillation framework, supervising the identity extractor with region-sensitive spatial features and cross-modality audio’s temporal representations to obtain rich spatio-temporal information. Attribute bias can cause errors in the extracted identity features, and Yu et al. [

223] aligned reference and test images to the same attribute space to extract identity differences, quantifying pixel differences to discern authenticity. The key ideas of several methods and their AUC scores comparison on the FF++, CDF and DFDCp datasets are shown in

Table 17.

5. Future Research Directions and Conclusions

5.1. Future Research Directions

The previous sections of this survey provide a comprehensive overview of AI-created visual content detection, including generation technologies, datasets, and related detection methods, along with a detailed classification of detection techniques, offering essential guidance for future researchers. Based on the study of existing challenges, this section will discuss the future directions for AI-created visual content detection.

Regarding AI-generated images detection algorithms, although there has been some development in this area, challenges such as low generalization ability and poor robustness still persist. The fundamental issue in AI-generated images detection is the design of a detector that can effectively identify the differences between real and fake images, while also maintaining strong generalization on unknown generative models. Since the performance of AI-generated images detection algorithms based on deep learning largely depends on the specific generative models in the training datasets, their performance typically drops significantly when tested on samples from different generative models. This necessitates a deeper analysis of the intrinsic relationships between different generated images and improvements in network architectures to learn more effective, generalized features. When images are subjected to certain post-processing attacks (such as scaling, rotation, or JPEG compression), the model’s ability to detect general features of generated images also diminishes. In the future, many methods are likely to focus on extracting universal features of generated images from multiple domain-specific features of images. Some methods aim to design detectors that do not require training on fake images, thus avoiding the reliance on specific generative data and offering higher generalization. With the development of image-text models such as CLIP, some research is inclined towards using both images and text for detecting generated images.

For deepfake detection, firstly, existing detection methods have achieved good performance within datasets, but due to the differences in datasets and various forgery techniques, the generalization performance remains insufficient. Therefore, it is necessary to explore methods to improve generalization, such as applying learning strategies like meta-learning and incremental learning, combining data augmentation techniques, or utilizing self-supervised learning to enhance generalization. These are promising directions for future research. Secondly, most current detection technologies are based on a single modality, limited to video and image data. However, many forgery techniques also involve multimodal data such as audio and text. Relying solely on single-modality information may limit detection performance. It is crucial to effectively integrate multimodal knowledge and perform multimodal collaborative learning to fully leverage forgery cues, thereby improving detection performance. Thirdly, with the widespread dissemination of deepfake content across social media, news reports, and live streaming, deepfake detection will move towards real-time online detection to meet practical demands. However, most current methods focus primarily on improving detection accuracy, with little attention given to model efficiency and lightweight design. This gap remains to be addressed in future research. Finally, in addition to passive detection of forged content, researchers are beginning to focus on active defense methods, such as adding watermarks or noise through preprocessing techniques to make images and videos resistant to forgeries or easily detectable when forged, fundamentally preventing the generation and spread of deepfake content.

5.2. Conclusions

In this review, we provide an overview of existing research on AI-created visual content detection, include AI-generated images detection techniques and deepfake image forensics based on deep learning.

For AI-generated images detection, the key approach is to train detectors to explore distinctive feature patterns between real and fake images. In this investigation, we analyze and review the latest techniques for AI-generated images detection based on deep learning. First, we introduce a deep learning-based framework for AI-generated images detection, which includes evaluation metrics and commonly used datasets. Based on the type of detection features, AI-generated images detection methods can be classified into three categories: spatial-domain-based detection methods, frequency-domain-based detection methods, cross-domain feature fusion detection methods, and image-text-based detection methods. Next, we compare and analyze the state-of-the-art algorithms from three aspects: detection methods, advantages, and limitations. Finally, we address the challenges in current AI-generated images detection algorithms and explore future research directions.

In deepfake detection, we conducted a comprehensive study of existing detection technologies and summarized these methods into four categories based on feature selection: spatial features-based, spatio-temporal features-based, biological features-based, and identity features-based. Methods based on spatial features focus on mining forgery cues within single-frame images, and they can be further subdivided into space domain-based, frequency domain-based, and multi-domain fusion methods. These approaches generally lack generalization ability and overlook temporal information between video frames, making them unsuitable for detecting dynamic content. Methods based on spatio-temporal features integrate temporal information to enable video-level detection. Depending on the backbone network used, these can be classified into CNN-based, CNN+RNN-based, and transformer-based methods. Among these, transformer-based methods have stronger spatio-temporal modeling capabilities, and most current spatio-temporal methods use transformer networks as the backbone. Both the aforementioned categories are based on general features. While they achieve good detection performance, they lack interpretability. To address this, biological features-based methods have been introduced. These methods leverage the biological regularities inherent in faces, such as mouth movement, gaze direction, and heart rate, to detect deepfakes. They are more interpretable and easier to understand. Additionally, some forgery techniques alter the identity features of the video subject, prompting researchers to use facial recognition models for identity consistency verification to detect deepfakes. Several improvements have been made in this area, but these methods rely on identity differences, so they are not suitable for detecting forgery techniques that do not change the identity. Finally, based on the existing challenges, a brief analysis of future directions for deepfake detection is provided.

Figure 1.

The basic categories of AI-created visual content detection.

Figure 1.

The basic categories of AI-created visual content detection.

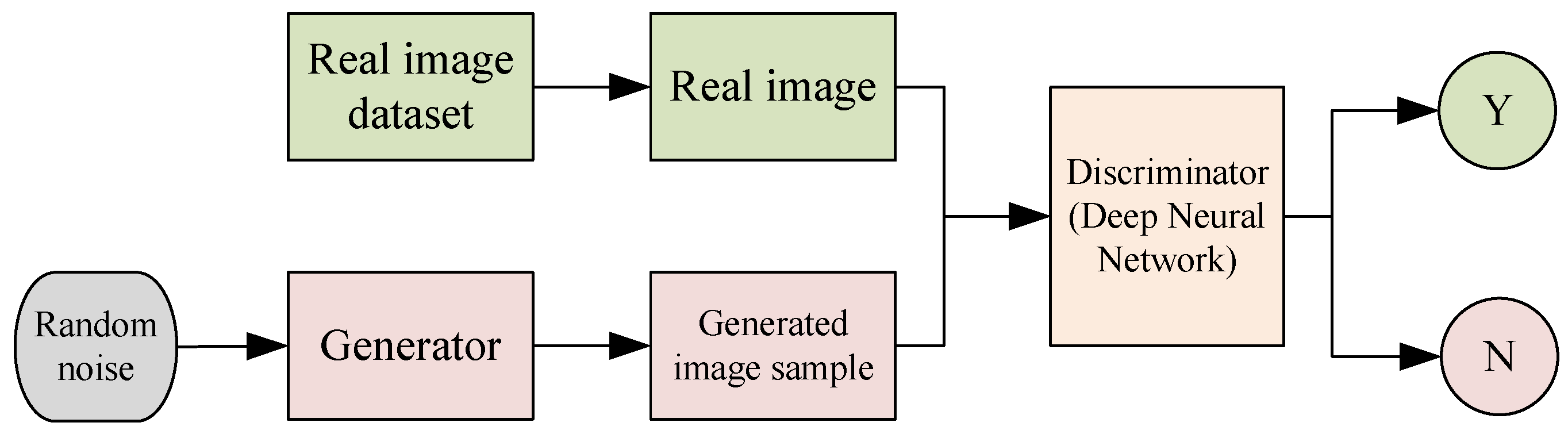

Figure 2.

Basic framework of generative adversarial network.

Figure 2.

Basic framework of generative adversarial network.

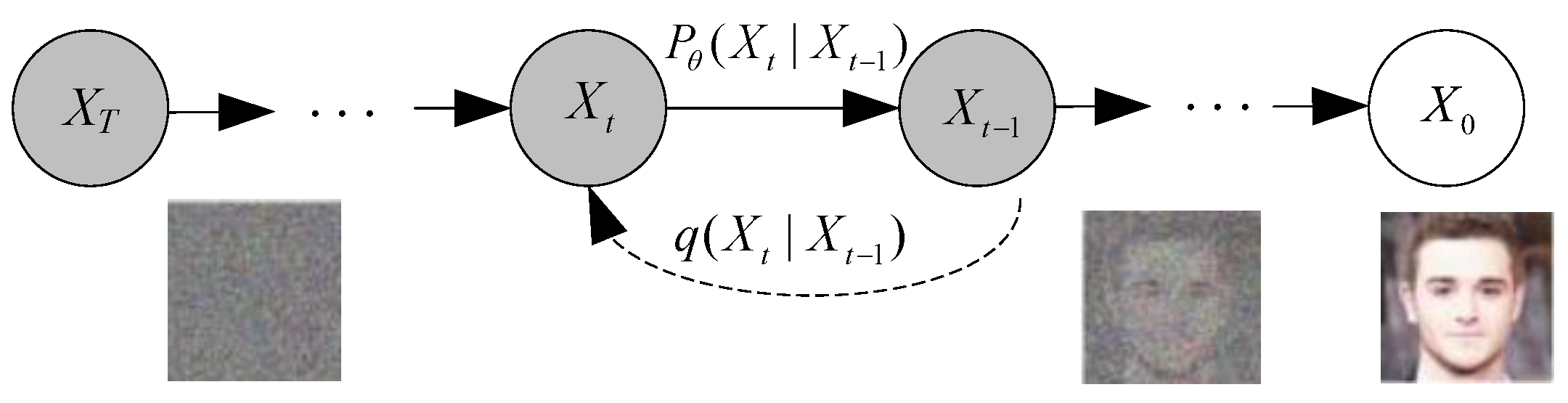

Figure 3.

Basic framework of diffusion model.

Figure 3.

Basic framework of diffusion model.

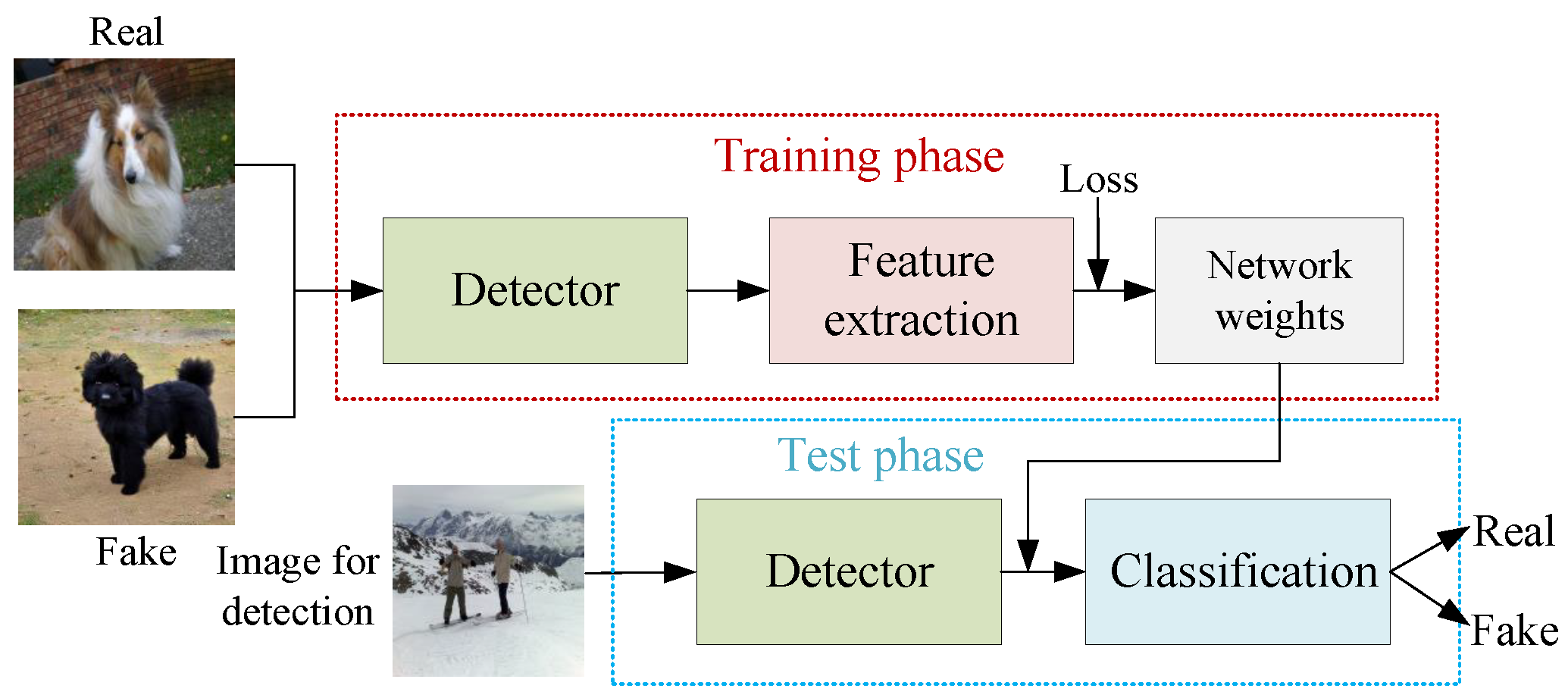

Figure 4.

Basic framework of AI-generated images detection on deep learning.

Figure 4.

Basic framework of AI-generated images detection on deep learning.

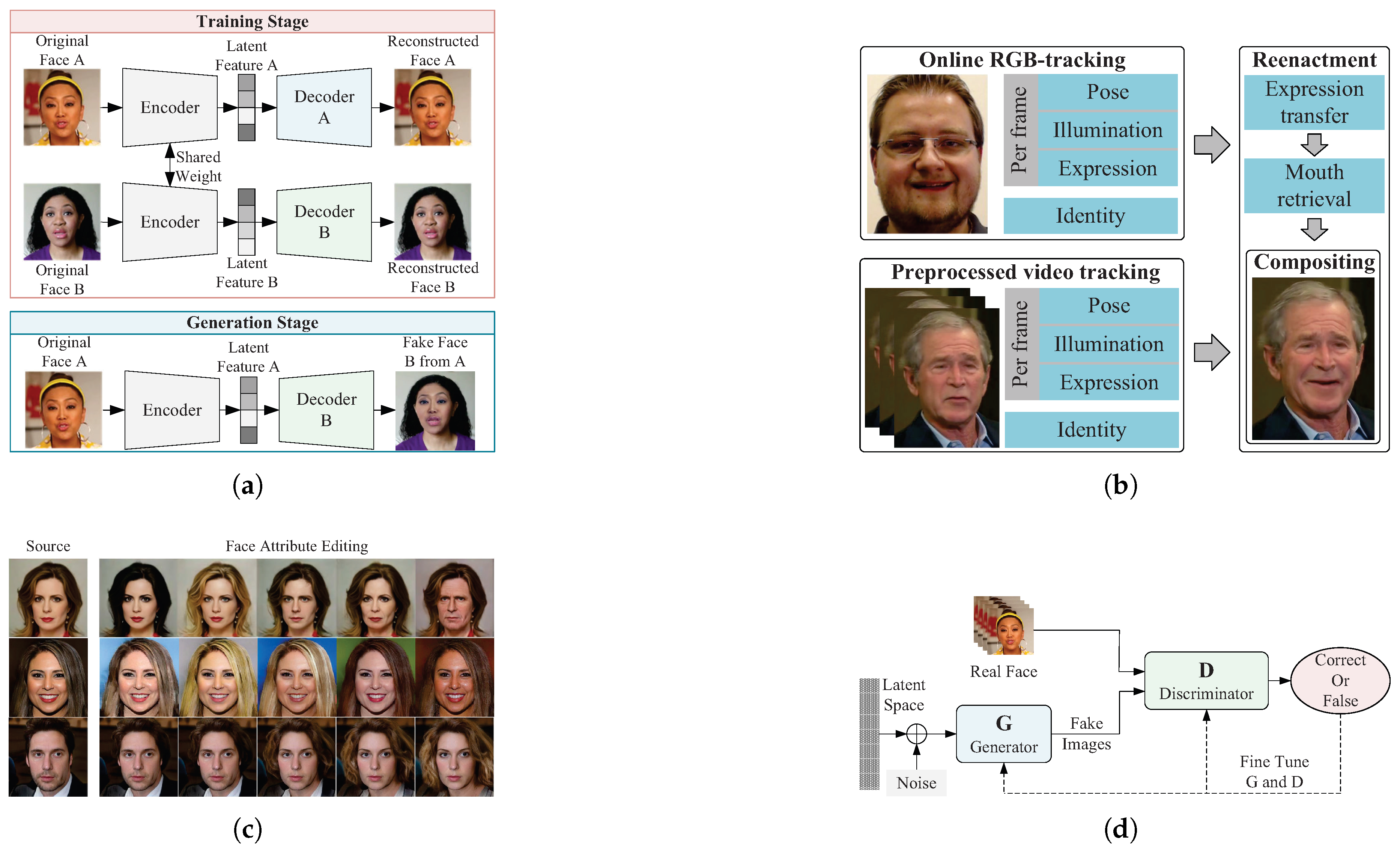

Figure 5.

Examples of the generation process or forged faces for the four forgery types: (

a) Deepfakes [

47] forgery technique based on encoder-decoder architecture, belongs to faceswap; (

b) Synthesis framework for Face2Face [

48] in face reenactment, where the expression of the source face is modified; (

c) Some examples of fake faces with attribute editing, where the hairstyle, gender or age has been modified; (

d) General architecture for virtual face generation.

Figure 5.

Examples of the generation process or forged faces for the four forgery types: (

a) Deepfakes [

47] forgery technique based on encoder-decoder architecture, belongs to faceswap; (

b) Synthesis framework for Face2Face [

48] in face reenactment, where the expression of the source face is modified; (

c) Some examples of fake faces with attribute editing, where the hairstyle, gender or age has been modified; (

d) General architecture for virtual face generation.

Figure 6.

Taxonomy of AI-generated images detection methods based on deep learning.

Figure 6.

Taxonomy of AI-generated images detection methods based on deep learning.

Figure 7.

Taxonomy of deepfake detection methods based on feature selection.

Figure 7.

Taxonomy of deepfake detection methods based on feature selection.

Figure 8.

The general synthesis process of SBI. ⨀ denote element-wise multiplication operation.

Figure 8.

The general synthesis process of SBI. ⨀ denote element-wise multiplication operation.

Figure 9.

Three commonly used high-pass filtering kernels in SRM and their resulting noise residual images.

Figure 9.

Three commonly used high-pass filtering kernels in SRM and their resulting noise residual images.

Figure 10.

The general detection process based on the CNN and RNN hybrid model.

Figure 10.

The general detection process based on the CNN and RNN hybrid model.

Table 1.

Datasets for AI-generated images detection.

Table 1.

Datasets for AI-generated images detection.

| Datasets |

Year |

Generator |

Number of images (k) |

| Fake |

Ture |

| CNNSpot [69] |

2020 |

GANs |

362 |

262 |

| Diffusiondb [40] |

2022 |

DMs |

14000 |

0 |

| DE-Fake [136] |

2023 |

DMs |

20 |

60 |

| Artifact [41] |

2023 |

GANs, DMs |

1522 |

962 |

| Cifake [42] |

2024 |

DMs |

60 |

60 |

| Genimage [43] |

2024 |

GANs, DMs, Others |

133 |

1350 |

| Fake2M [44] |

2024 |

GANs, DMs, Others |

2000 |

0 |

| Wildfake [45] |

2024 |

GANs, DMs, Others |

2577 |

1313 |

Table 2.

A summary of existing deepfake datasets, including their modality, real/fake numbers and generation techniques.

Table 2.

A summary of existing deepfake datasets, including their modality, real/fake numbers and generation techniques.

| Dataset |

Year |

Modality |

Real/Fake |

Source |

Generation Technique |

| UADFV |

2018 |

Video |

49 / 49 |

YouTube |

FakeAPP |

| Deepfake TIMIT |

2018 |

Video |

320 / 640 |

VidTIMIT |

FaceSwap |

| FF++ |

2019 |

Video |

1000 / 5000 |

YouTube |

Deepfakes, Face2Face, NeuralTextures, FaceSwap, FaceShifter |

| DFD [54] |

2019 |

Video |

363 / 3068 |

Live Action |

Deepfakes |

| DFDC |

2020 |

Video |

23,654 / 104,500 |

Live Action |

FaceSwap, NTH, FSGAN, StyleGAN |

| DFo [55] |

2020 |

Video |

11,000 / 48,475 |

YouTube |

FaceSwap |

| CDF-(v1, v2) [56] |

2020 |

Video |

590 / 5639 |

YouTube |

DeepFake |

| WDF |

2020 |

Video |

3805 / 3509 |

Internet |

Internet |

| KoDF [57] |

2021 |

Image |

175,776 / 62,166 |

Live Action |

FaceSwap, DeepFaceLab, FSGAN, FOMM, ATFHP, Wav2Lip |

| OpenForensics [58] |

2021 |

Image |

45473 / 70325 |

Google Open Images |

GAN |

| FFIW10k [59] |

2021 |

Video |

10,000 / 10,000 |

Live Action |

FaceSwap, FSGAN, DeepFaceLab |

| DFDM [60] |

2022 |

Video |

590 / 6450 |

YouTube |

Facewap |

| DF-Platter [61] |

2023 |

Video |

764 / 132,496 |

YouTube |

FSGAN, FaceSwap, FaceShifter |

| Diffusion Deepfake [62] |

2024 |

Image |

94120 / 112,627 |

DiffusionDB |

Diffusion Model |

Table 3.

Confusion matrix.

Table 3.

Confusion matrix.

|

Prediction Label |

Positive |

Negative |

| True Label |

|

| Positive |

True Positive () |

False Negative () |

| Negative |

False Positive () |

True Negative () |

Table 4.

A comparison of spatial features-based methods.

Table 4.

A comparison of spatial features-based methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Method |

Advantage |

Deficiency |

| Yu et al. [65] |

2019 |

Fingerprint attribution |

Trace the image back to the specific generative model |

More complex computation when there are many models |

| Wang et al. [69] |

2020 |

Data

augmentation |

The generalization ability of GAN-generated images is good |

Poor generalization ability on diffusion models |

| Jeon et al. [70] |

2020 |

Teacher-student

model |

Transferable model and good detection accuracy |

Poor generalization ability on diffusion models |

| Chai et al. [71] |

2020 |

Image patch |

Extracting

local features of the image |

Ignoring global information |

| Mi et al. [72] |

2020 |

Self-attention mechanism |

Focus on the artifact regions of the features |

Some generative models do not use upsampling operations |

| Girish et al. [75] |

2021 |

Fingerprint

attribution |

Good generalization to unseen GANs |

As the number of generative models increases, the computational cost grows |

| Liu et al. [76] |

2022 |

Noise pattern |

Good

generalization |

The noise information in the compressed image affect detection performance |

| Jeong et al. [77] |

2022 |

Fingerprint recognition |

Only real images are needed for training, avoiding data dependency |

As the number of generative models increases, the computational load grows |

| Tan et al. [81] |

2023 |

Gradient feature |

Excellent detection performance on GAN-generated images |

Poor detection performance on non-GAN generated images |

| Ojha et al. [82] |

2023 |

CLIP model |

CLIP

demonstrates good generalization capability in detecting generated images |

The method is simple, and the accuracy is not high |

| Wang et al. [84] |

2023 |

Reconstruction

error |

Performs well in detecting on diffusion models |

Performs poorly on non-diffusion models |

| Tan et al. [88] |

2024 |

Pixel correlation |

Simple to compute, with good generalization |

Relies on upsampling operations, with limitations |

| Lim et al. [89] |

2024 |

Reconstruction error |

Lightweight network, faster computation |

Has limitations for diffusion models |

| Yan et al. [90] |

2024 |

Data augmentation |

The method can be combined with other networks to improve generalization |

It causes the computation time of other networks to increase |

| Chen et al. [92] |

2024 |

Image reconstruction |

The method can be combined with other detectors |

Additional reconstruction dataset is required |

Table 5.

A comparison of color feature-based methods.

Table 5.

A comparison of color feature-based methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Method |

Advantage |

Deficiency |

| He et al. [99] |

2019 |

Chrominance components |

Strong robustness |

Limited generalization |

| Chandrasegaran et al. [100] |

2022 |

Relevance

statistic |

Discover that color is a critical feature in universal detectors |

Images generated by diffusion models are similar to real images in terms of color |

| Uhlenbrock et al. [101] |

2024 |

Color statistics |

High accuracy |

Not tested on GAN datasets |

| Qiao et al. [102] |

2024 |

Co-occurrence matrix |

Exhibits strong robustness |

The experiment is simple |

Table 6.

A comparison of texture features-based methods.

Table 6.

A comparison of texture features-based methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Method |

Advantage |

Deficiency |

| Liu et al. [103] |

2019 |

Texture

differences |

Using texture differences for generated image detection |

Limited generalization |

| Yang et al. [104] |

2021 |

Multi-scale

texture |

Extract multi-scale and deep texture information from the image |

The network

is complex and computationally intensive |

| Zhong et al. [105] |

2023 |

Texture contrast |

Good generalization ability |

Dependent on the high-frequency components of the image |

| Zhang et al. [106] |

2024 |

Deep LBP network |

Extract depth texture information |

The experiment is simple and unable to validate the performance of the method |

Table 7.

A comparison of other methods.

Table 7.

A comparison of other methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Method |

Advantage |

Deficiency |

| Lorenz et al. [107] |

2023 |

Local intrinsic dimensionality |

Good performance in diffusion models |

Dependent on data augmentation |

| Lin et al. [108] |

2023 |

Genetic

programming |

Can improve accuracy to some extent |

Limited generalization ability |

| Sarkar et al. [109] |

2024 |

Projective geometry |

Having some level of generalization |

Lacks effective defense against some attacks |

| Cozzolino et al. [110] |

2024 |

Coding cost |

Good generalization ability |

Weak robustness |

Table 8.

A comparison of frequency domain-based methods.

Table 8.

A comparison of frequency domain-based methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Method |

Advantage |

Deficiency |

| Zhang et al. [112] |

2019 |

Frequency artifacts |

Detect frequency differences between real and fake images |

Limited generalization |

| Frank et al. [113] |

2020 |

2D-DCT |

Discover that color is a critical feature in universal detectors |

Images

generated by diffusion models are similar to real images in terms of color |

| Durall et al. [114] |

2020 |

High-frequency

fourier modes |

Transferable model and good detection accuracy |

Poor generalization

ability on diffusion models |

| Corvi et al. [119] |

2023 |

Training DM’s images |

Enhancing the performance of detecting diffusion model images |

With the emergence of new generative models, updates are continuous |

| Tan et al. [123] |

2024 |

Frequency learning |

It can learn features unrelated to the generative model, enhancing the model’s generalization ability |

High computational cost and time-consuming |

| Doloriel et al. [124] |

2024 |

Frequency mask |

Less

dependence on detector data |

The mask size affects the performance of the detector |

Table 9.

A comparison of cross-domain features fusion methods.

Table 9.

A comparison of cross-domain features fusion methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Method |

Advantage |

Deficiency |

| Yu et al. [126] |

2022 |

Channel and spectrum difference |

Effectively mine intrinsic features |

Limited

generalization ability |

| Luo et al. [128] |

2024 |

Reconstruction error |

Able to extract refined features from images |

Poor performance on non-diffusion models |

| Lanzino et al. [129] |

2024 |

Three types of

feature fusion |

Capture multiple features of the image with a simple network |

Weak

resistance to adversarial attacks |

| Xu et al. [133] |

2024 |

Deep trace feature fusion |

Good generalization performance |

Complex network with long computation time |

| Leporoni et al. [134] |

2024 |

RGB-depth

integration |

RGB features capable of extracting depth |

Weak resistance to adversarial

attacks |

Table 10.

A comparison of image-text-based methods.

Table 10.

A comparison of image-text-based methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Method |

Advantage |

Deficiency |

| Wu et al. [137] |

2024 |

Contrastive learning |

Transform the synthetic image detection problem into a recognition problem |

Text description affects the performance of the detector |

| Liu et al. [138] |

2024 |

Forgery aware adaptive |

Strong generalization ability |

Computationally intensive and time-consuming |

| Cazenavette et al. [139] |

2024 |

Inverting

stable diffusion |

Good detection accuracy |

Limited in the context of stable diffusion |

| Keita et al. [141] |

2024 |

Technical

optimizations |

Combining BLIP and LoRA to enhance accuracy |

Computationally intensive and time-consuming |

| Sha et al. [143] |

2024 |

Image reconstruction |

Requires no large training data and has good robustness |

Mainly focused on diffusion models, with certain limitations |

Table 11.

A comparison of space domain information-based deepfake detection methods.

Table 11.

A comparison of space domain information-based deepfake detection methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Key Idea |

Backbone |

Dataset |

| Shiohara et al.[147] |

2022 |

Synthetic data |

EfficientNetB4 |

FF++, CDF, DFD, DFDCp [157], DFDC, FFIW10k

|

| Bai et al.[154] |

2024 |

Regional noise inconsistency |

Xception |

FF++, CDF, DFDC |

| Gao et al.[151] |

2024 |

Feature decomposition |

Convolution layer |

FF++, WDF, CDF, DFDC |

| Lu et al.[152] |

2024 |

Long-distance attention |

Xception |

FF++, CDF |

| Lin et al.[149] |

2024 |

Synthetic data, curriculum learning |

Transformer |

FF++, CDF, DFDCp, DFDC, WDF |

Table 12.

A comparison of frequency domain information-based deepfake detection methods.

Table 12.

A comparison of frequency domain information-based deepfake detection methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Transform Type |

Backbone |

Dataset |

| Qian et al.[159] |

2020 |

DCT |

Xception |

FF++ |

| Li et al.[160] |

2021 |

DCT |

Xception |

FF++ |

| Miao et al.[162] |

2023 |

DWT |

Transformer |

FF++, CDF, DFDC, Deepfake TIMIT |

| Zhao et al.[165] |

2023 |

FFT |

Convolution and attention layer |

FF++-Deepfakes, FFHQ, CelebA |

| Gao et al.[161] |

2024 |

DCT, DWT |

Convolution and fusion layer |

FF++, CDF, OpenForensics |

| Hasanaath et al.[164] |

2024 |

DWT |

EfficientNetB5 |

FF++, CDF |

| Li et al.[163] |

2024 |

DWT |

Transformer |

FF++, CDF, DFDC, Deepfake TIMIT, DFo |

Table 13.

A comparison of multi-domain information fusion-based deepfake detection methods.

Table 13.

A comparison of multi-domain information fusion-based deepfake detection methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Information Source |

Fusion Method |

Backbone |

Dataset |

| Luo et al. [172] |

2021 |

RGB, SRM noise |

Concatenation |

Xception |

FF++, DFD, DFDC, CDF, DFo |

| Fei et al. [174] |

2022 |

RGB, SRM noise |

Attention-guided |

ResNet-18 |

FF++, CDF, DFD |

| Wang et al. [166] |

2023 |

RGB, DWT |

Concatenation |

Xception |

FF++, CDF, UADFV |

| Guo et al. [171] |

2024 |

RGB, High-frequency |

Interaction, concatenation |

ResNet-26 |

HFF , FF++, DFDC, CDF |

| Wang et al. [170] |

2024 |

RGB, DCT |

Attention-guided |

Xception |

FF++, CDF |

| Wang et al. [167] |

2024 |

RGB, DWT, Residual feature |

Attention-guided |

ResNet-34 |

FF++, CDF, UADFV, DFD |

| Zhang et al. [173] |

2024 |

RGB, SRM noise |

Attention-guided |

EfficientNet |

FF++, DFDC, CDF, WDF |

| Zhou et al. [168] |

2024 |

RGB, FFT |

Multihead-attention |

EfficientNetB4 |

FF++, CDF, WDF |

Table 14.

Summary of methods for extracting spatio-temporal features using CNNs.

Table 14.

Summary of methods for extracting spatio-temporal features using CNNs.

| Ref. |

Year |

Improved method |

Backbone |

Dataset |

| Liu et al.[176] |

2023 |

Local attention augmentation |

3D ResNet-50 |

FF++, CDF, DFDC |

| Pang et al.[178] |

2023 |

Sampling strategy |

ResNet-34 |

FF++, CDF, DFDC, WDF |

| Wang et al.[181] |

2023 |

Attention augmentation |

ResNet-50 |

FF++, CDF, WDF, DeepfakeNIR |

| Concas et al.[177] |

2024 |

Quality feature |

Convolution layer |

FF++ |

| Yu et al.[180] |

2024 |

Multilevel spatio-temporal features |

ResNet-50, GCN |

FF++, DFD, DFDC, CDF, DFo |

| Zhang et al.[179] |

2024 |

Sampling strategy |

EfficientNetB3 |

FF++, CDF, DFDC, WDF |

Table 15.

A summary of Transformer-based methods.

Table 15.

A summary of Transformer-based methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Network Architecture Design |

Input Design |

Dataset |

| Yu et al.[193] |

2023 |

✕ |

✔ |

FF++, DFD, DFDC, DFo, CDF, WDF |

| Zhao et al.[195] |

2023 |

✔ |

✕ |

FF++, CDF, DFDC |

| Choi et al.[200] |

2024 |

✕ |

✔ |

FF++, DFo, CDF, DFD |

| Liu et al.[196] |

2024 |

✕ |

✔ |

DFGC, FF++, DFo, CDF, DFD, UADFV |

| Tian et al.[201] |

2024 |

✕ |

✔ |

FF++, CDF, DFDC |

| Tu et al.[202] |

2024 |

✕ |

✔ |

FF++ |

| Xu et al.[203] |

2024 |

✔ |

✔ |

FF++, CDF, DFDC, DFo, WDF, KoDF, DLB |

| Yue et al.[197] |

2024 |

✕ |

✔ |

FF++, CDF, DFDC, DiffFace, DiffSwap |

Table 16.

A comparison of biological features-based deepfake detection methods.

Table 16.

A comparison of biological features-based deepfake detection methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Biosignal Type |

Backbone |

Dataset |

| Yang et al. [204] |

2019 |

Head poses |

SVM |

UADFV, DARPA GAN [214] |

| Qi et al. [209] |

2020 |

rPPG |

DNN, GRU |

FF++, DFDCp |

| Demir and Ciftci [206] |

2021 |

Eye, gaze |

DNN |

FF++, DF Datasets [215], CDF, DFo |

| Haliassos et al. [205] |

2021 |

Mouth movements |

ResNet-18, MS-TCN |

FF++, CDF, DFDC |

| Yang et al. [211] |

2023 |

CPPG |

ACBlock-based DenseNet |

FF++, FF, DFDC, CDF, FakeAVCeleb [216] |

| Peng et al. [207] |

2024 |

Gaze |

ResNet-34,ResNet-50, Res2Net-101 |

FF++, WDF, CDF, DFDCp |

| He et al. [208] |

2024 |

Gaze |

ResNet-18 |

FF++, WDF, CDF |

| Saif et al. [212] |

2024 |

Facial landmarks |

GCN |

FF++, CDF, DFDC |

| Wu et al. [210] |

2024 |

rPPG |

MLA, Transformer |

FF++, CDF |

| Zhang et al. [213] |

2024 |

Facial landmarks, informative regions |

GCN |

FF++, CDF, WDF, DFDCp, DFD, DFo, ForgeryNIR [217] |

Table 17.

The AUC score comparison of identity-based methods on the FF++, CDF and DFDCp datasets.

Table 17.

The AUC score comparison of identity-based methods on the FF++, CDF and DFDCp datasets.

| Ref. |

Year |

Key Idea |

FF++ |

CDF |

DFDCp |

| Cozzolino et al. [219] |

2021 |

Adversarial training |

— |

0.840 |

0.910 |

| Fang et al. [221] |

2024 |

Identity bias rectification |

0.996 |

0.945 |

0.983 |

| Fang et al. [222] |

2024 |

Multi-modal knowledge distillation |

0.958 |

0.921 |

0.994 |

| Yu et al. [223] |

2024 |

Attribute alignment |

0.991 |

0.911 |

— |