Introduction

The lack of credible pathways in limiting global warming below the 1.5 degrees preindustrial level has led to several climate intervention proposals such as Solar geoengineering (used in this paper interchangeably as “geoengineering”). For context, Solar geoengineering is summarily seen as temporal ‘hypermodern technofix’ in addressing global warming while exploring a permanent solution to climate change and its impact (Finus and Furini, 2022). It is seen as a "premeditated large-scale interference in the natural earth systems using human-made strategies and scientific competencies, and technology to alter the climate either temporarily or permanently" (Patrick 2021:21). While the viability of a geoengineering solution has been largely unclear, debates surrounding its use have generated numerous opposing views, especially in the global North (Lawrence et al., 2018; Kravitz & MacMartin, 2020).

The central arguments on geoengineering underlined the need for more research as the implication of its applications is widely unknown (Kravitz & MacMartin, 2020); its impact is uneven across geographical spaces (Trisos, 2018); as well as the issue of governance (Talberg et al., 2018; McLaren & Corry, 2021); ethics and justice (McLaren, 2018; Hourdequin, 2019; Pamplany, Gordijn, & Brereton, 2020) among many others. While there are opposing views on Solar geoengineering in general, the need to explore how its engagements should be tailored going forward is important for policy and developmental agendas. As the United States’ Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) (2023) opined, the decision on whether and how such geoengineering engagements will happen "should be based upon an understanding of the risks and benefits to human health and well-being of its implementation relative to those anticipated under the current climate change trajectory" (OSTP, 2023:6).

It is pertinent to note that geoengineering is a highly controversial topic. While some groups support more research on geoengineering to better understand it and inform policy (Morrow, 2020: Keith, 2021), others are totally against both the research and potential engagement of geoengineering (Biermann et al., 2022). While there are few public participations concerning geoengineering (Bellamy and Lezaun, 2015), such engagements has been mostly in the global North (Carvalho and Riquito, 2022) with few exceptions like Winickoff et al. (2015), Carr (2015), and Whyte (2018). Interestingly, the debate on geoengineering seems unpopular among policymakers and researchers from the Global South, especially in Africa (Rahman et al., 2018; Patrick, 2021). The unpopularity of this subject matter in Africa could be traced to what Patrick (2020) refers to as the 'reactionary rather than proactive' nature and tendencies of policymakers and stakeholders within the continent in addressing public issues. There is also a general lack of awareness and limited involvement of African scientists on the subject matter (Patrick, 2021).

In view of the above summations, the recent/ongoing Covid-19 pandemic in terms of individual, government, and public health responses to its impact and adaptive responses presents lessons to consider for geoengineering engagements. Our attempt in this paper is not to equate 'geoengineering' in the same form or shape with the Covid-19 virus or the eventual pandemic. We hope we can deduce lessons from the Covid-19 pandemic that could be useful in our engagement with solar geoengineering as an emerging discourse. The paper's discourse on geoengineering encompasses all aspects of geoengineering (Solar Radiation Management (SRM) and Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR)). Also, by 'engagement,' we mean all the activities relating to Solar geoengineering, from research to public involvement and interactions, government policy formation and eventual deployment.

This paper provides a descriptive summary overview of Covid-19 adaptive responses as possible points to consider for Solar geoengineering engagement. The rationale is to examine the extent to which vertical and horizontal

i reactions and public opinions influence policy response and actions for Covid-19 adaptation and coping mechanisms as a lesson for Solar geoengineering engagement. While the author understands the magnitude of the controversial nature of Solar geoengineering in terms of research and possible engagement, the paper does not support or oppose the subject matter. It, however, proffers ways to examine the subject matter in terms of lessons from another contemporary global issue. In this sense, a focus on how public opinion influences policy and how policy influences public opinion using the Covid-19 pandemic response as a case presents a template for geoengineering engagement.

Methodology

The paper adopts a descriptive desktop review approach (See Manolakis and Kennedy, 2012; Webb et al., 2015). Secondary data were sourced using a convenience random sampling technique to gather literature from online sources. These were then coded and analyzed for relevance to the subject of discourse. The scope years for the inclusion and exclusion criteria was a target on studies published between 2010 and 2023. Factoring in the convenience random sampling criteria, we assessed how the identified sample paper to be reviewed fits the study's criteria (see

Sharma, 2017). Using search engines such as ISI, ProQuest, Scopus and Google Scholar, keywords such as 'Covid-19,' 'geoengineering,' 'public engagement,' and 'governance' were search individually and collectively. As

Table 1 indicated, from the 489,869 articles found on Covid-19, and 2,222 articles found on Geoengineering, only 7 articles came up when 'Covid-19' and 'geoengineering' were combined as a search theme

ii.

Interestingly, only 1 article (Radunsky & Cadman, 2021) appeared in the combined search for Covid-19, geoengineering, and governance, while no article was found in the search of the combined theme of "Covid-19, geoengineering, and public engagement". The combined themes of "geoengineering and governance" produced a result of 257 articles, while only 25 articles came up in the combination of "geoengineering, governance, and public engagement.” Using convenience random sampling, 89 articles were selected and analyzed for relevance to the aim of the paper.

Synopsis of COVID 19

A brief discussion on the Covid-19 pandemic is crucial to provide an appropriate context for the discourse provided in this paper. Summarily, the novel coronavirus (popularly referred to as Covid-19) was first discovered in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 and declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 (WHO, 2020). The swiftness of its spread brought the world to a standstill, affecting all facets of life and livelihood in a matter of weeks (Patrick, Abiolu & Abiolu 2021). Many countries' immediate policy responses involved lockdowns and border closures to curtail the rapid spread of the disease and avert its catastrophic damages (Asayama et al., 2021). As public opinion and science solidified, these policy responses evolved into mask mandates, social distancing, and vaccine requirements, among others (Patrick et al., 2021). An important point to note is the unknown nature of the Covid-19 pandemic at its inception in terms of global awareness and readiness of individuals, households, and national economies to adapt. This led to panic-like decisions and misinformation. However, as information increased, general awareness and coping strategies for the pandemic increased considerably.

COVID-19 and Solar Geoengineering Correlations

To establish a correlation, an assessment of the swiftness in terms of spread, impact, governance, and general awareness of Covid-19 pandemic and by inference, Solar geoengineering as an intervention option is critical. The rationale is not to establish a clear-cut correlation but to show descriptive similarities and differences between the Covid-19 pandemic and Solar geoengineering engagements in terms of methodologies.

It is an irrefutable fact that the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic was comparatively swift in comparison to other historical global pandemics, largely due to the advancement in globalization and the movement of people and goods (Teoh et al., 2020; Patrick et al., 2021a,b,c). The rate of spread in the few days and weeks that followed after its initial discovery in December 2019 was alarming, leading to its declaration as a global pandemic in March 2020, about three months later (WHO, 2021). The implication of a World Health Organization's declaration as a global pandemic implies that the disease had become a global concern with a global non-discriminatory impact that was felt across nations, economic, political, and social sectors concurrently. In the same vein, climate intervention strategies such as geoengineering have been proposed as a temporal fix to climate change impact (Finus and Furini, 2022). However, if left unchecked, is expected to have a swift global impact across space. From this premise, we can argue that the obvious similarity between Covid-19 and Solar geoengineering is the borderless nature of their impact. Regardless of where either commences, it is apparent that the impact will cut across countries and regions in different climes.

Furthermore, in the case of Covid-19 impact, the literature is filled with various discourses and prisms on the impact of the pandemic on life and livelihood as it affects all aspects of the human ecosystem. These included, among others, discuss of the impact of covid on education and curriculum changes (Patrick et al., 2021a); Entertainment and sports (Patrick, Omoge, & Usman, 2021); Human security (Poudel et al., 2020; Patrick et al., 2021c); Economy (Hevia, & Neumeyer, 2020); Health (Teoh et al., 2020) among others. While the impact of the pandemic is felt globally, the actual impact is relative in terms of the adaptive capacities and coping mechanisms available across geographical spaces, leading to disproportionate positive and negative impacts on different people and places. In the same vein, unabated and unmitigated climate change will produce impacts that will affect all facets of life and livelihood (Barrage, 2020). While the impact of Solar geoengineering application upon implementation is largely unknown (Kravitz and MacMartin, 2020; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2021), the assumption is that it is also expected to alter future livelihoods in disproportionate terms (Hourdequin, 2019; Patrick, 2021).

It is also pertinent to note that just as the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic produced both positive and negative effects across different spaces (Zambrano-Monserrate, Ruano, and Sanchez-Alcalde, 2020), the same negative and positive impact is expected for Solar geoengineering applications (Bal et al., 2019). These assumptions are complicated and present serious governance and ethical issues for the entire geoengineering research and application. In this sense, the immediate challenge is determining the positive and negative impact of Solar geoengineering applications in the face of different regions' possible advantages and disadvantages to such applications. Interestingly, the major proponents and opposition to Solar geoengineering engagements are based on these possible disproportionate global and regional advantages and disadvantages (Morrow, 2020: Keith, 2021; Biermann et al., 2022). While some schools of thought see the need to understand Solar geoengineering as a viable option in mitigating climate change impact (Morrow, 2020: Keith, 2021), others argue for the need for the complete abolishment of the entire endeavor due to issues such as moral injustices and the unknown implication of such deliberate climate alteration among others (Biermann et al., 2022).

Interestingly, the Covid-19 pandemic also shows a similar resemblance in terms of its disproportional impact on the poor due to their weak coping mechanism, among others. This is also true of the tentative implication of geoengineering applications, as scholars argued that its impact would be disproportionate across regions but particularly negative for the poor (Talberg et al., 2018; Trisos, 2018). A case in point on the disproportional impact of the Covid-19 was felt in the global vaccine distribution. This was tilted more to the global North's advantage than the poor global South countries, as well as the loss of means of livelihood and human security concerns for poor households (Patrick et al., 2021).

COVID-19 Responses and Lessons for Solar Geoengineering

The immediate policy response of governments globally in the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic was the enactment of lockdown protocols and border closures (McCartney, 2021). Notably, this "panic-like" policy action was influenced by expert opinion and the observance of global actions at that time. The rationale was an effort to curtail the virus's rapid spread as little was known of the virus. The government's subsequent policy protocols were also influenced by prevailing public opinion, experts' assessment of the current situation, and global practices. The immediate lesson is that the governments' actions were not isolated or taken independently. They were influenced by a global action taken individually by states (in terms of border closure and national lockdowns), public opinion, and expert opinion (from WHO and other public health experts). The point of note here is that each state actor's actions were influenced by broad consultation within its territory and the observation of prevailing international best practices. This is fundamental for Solar geoengineering applications as there is a need for synergy in government responses going forward. In this stance, the influence of public and experts' opinions in view of global happenings is vital. There is a need for national public engagements to ascertain public opinion in the form of surveys and deliberative dialogues and the coordination of global actions by states within the global arena in determining Solar geoengineering trajectories.

The influence of the media and the use of media sensitization across space was another vital response to curtaining the public health disaster of Covid-19. Considering the novelty of the pandemic, the media was extensively used in the dissemination and flow of information (real and fake news) across space from the global to local levels, not only by the government but ordinary citizens on the seriousness of the disease (Haroon and Rizvi, 2020), mode of transmission (Olapegba et al., 2020), best practices in terms of washing of hands, social distance, etc. to curtain individual spread (Oosterhoff and Palmer, 2020), among many others. These media awareness strategies led to increased knowledge and practice transformation in relation to the pandemic. In this sense, the initial fear and panic that greeted the pandemic due to lack of information were gradually sprinkled down. This also led to better coping and adaptation measures by citizens and government alike.

In view of the media investment response measure taken for Covid-19, the need for media investment in Solar geoengineering cannot be ignored. As Buck et al. (2020) opined, while the challenges of Covid-19 and climate change can be argued to be different and within separate timescales, the responses to both climate change and Covid-19 as global crises have the same resemblance as they happen within a similar media ecosystem and political landscape. The Covid-19 pandemic provides a viable opportunity to understand the nexus between media policies and the science environment during emergencies. Understanding these dynamics is important for geoengineering engagement as a viable route for curtailing the climate change crisis.

Considering the generally low awareness of Solar geoengineering as a climate intervention strategy by many people globally (Felgenhauer, Horton, and Keith, 2021), the need to educate communities and policymakers on geoengineering is critical. This was also the case with Covid-19, as the generally low awareness of the pandemic was swiftly replaced with media campaigns due to the synergy of media, policy, and science. In this sense, media sensitization will also be crucial in debunking organized distortion and misinformation on Solar geoengineering. Like Covid-19, unless the information is disseminated and strategically domesticated for community awareness, the panic and misinformation

iii that greeted the Covid-19 pandemic will also apply to Solar geoengineering engagements.

Furthermore, the subtle global political and power struggle (geopolitics) evident in the Covid-19 new order presents a relevant lesson for consideration in geoengineering governance. While several scholars have contributed to this debate, Patrick et al. (2021d) argued that global actors tend to concern themselves with ensuring strategic advantage at the detriment of collective global security as a response to the Covid-19 pandemic. In essence, actors were more concerned with taking actions that could benefit themselves regardless of the detriment of such action on the collective security of the whole. This is supported by Buck et al. (2020), who argued that the divergent responses of different countries to the Covid-19 pandemic demonstrate the delusion of a "single global society" as each country (both state and non-state actors) have differing interests, priorities, and goals. This was evident in the struggle for the "first to produce" vaccine politics (Patrick et al., 2021d). The rationale is premised on the idea (among others) that who controls vaccine production would have a strategic geopolitical advantage in terms of the global power dynamics (Navari, 2016; Patrick et al., 2021d). Other evident actions include the media shaming of China as the Covid-19 origin (Bonfiglioli, 2021; Jia and Lu, 2021); China's masks diplomacy as a push to promote itself as a global leader in fighting the Covid-19 pandemic (Wong, 2020), etc. While these actions could be analyzed independently, the correlation with Solar geoengineering becomes clearer once compared with the politics associated with greenhouse gas emission reduction and a lack of clear-cut agreement as to the way forward for 'green politics." With Covid-19, the geopolitical actions of global actions were subsequently conditioned by the need for global survival (Navari, 2016). This led to some level of corroborative engagement in the production of vaccines and regulatory protocols for the adaptive response of states (Fry et al., 2020). This 'spirit of cooperation, as exhibited in the global actions to curb Covid-19 impact, must be encouraged and replicated for Solar geoengineering research and engagements in the current and future. According to White et al. (2020) and Lemos et al. (2018), this will ensure a complimentary knowledge overlap necessary for problem-solving.

Another vital lesson the Covid-19 pandemic presents is the authentication and revelation of the unequal nature of the world. This inequality is evident on individual, local, national, and regional scales (Alvaredo et al., 2018). In this sense, the adaptive capacities of individuals, households, communities, and nations to the Covid-19 impact were relative in terms of governmental preparedness, economic standing, livelihood options, and geographical location (Asayama et al., 2021). These factors reflect the world's preexisting social and economic unequal conditions (Zinn, 2020; Asayama et al., 2021). Hence, an argument can be made that while the pandemic was universal, its impact depended on the relative characteristics of individuals, households, and community configurations. The relativity of the Covid-19 impact is crucial for Solar geoengineering engagement. In this sense, the argument that geoengineering applications will be beneficial and negative for some regions and livelihood options can be analyzed differently going forward. The technological and adaptive inequality of the world presents a situation whereby climate impacts ordinarily will present relatively unequal impacts across geographical spaces. In this sense, this supports the argument that regardless of Solar geoengineering's impact, we must realize that we can never have climate equality across space and time. There will always be beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries alike of both current climate change impacts and future Solar geoengineering solutions. In view of this, as with the Covid-19 pandemic, the need for research on the relative impact of Solar geoengineering and other factors of inequality from global, regional, national, and local scales becomes critical.

Takeaway Points from the COVID-19 Responses

Given the observed responses by all stakeholders to the Covid-19 pandemic at all levels of society, a central underlining lesson is that the "winning hearts and minds" in the sense of collective engagement for problem diagnosis and solution should be the underlining objective in the engagement processes for Solar geoengineering. In view of this, the following points should be considered. However, we do not claim that these points are all-encompassing, as the engagement process must always be localized to the immediate needs of the communities in question. This is also a support or opposition for geoengineering engagement rather a contribution to the policy and practice discourse on geoengineering in general.

There is a need to develop a strategic partnership among the various stakeholders for Solar geoengineering engagements: This paper conceptualizes "stakeholders" to include the science community, government, and all the communities, groups, and individuals whose lives and livelihood options may be affected by various climate intervention strategies proposed to be adopted. The premise of how large, small, or precise this "stakeholder" group will be is a subject of another discussion. To achieve this, conceptualizing the role of such strategic partnership in terms of each stakeholder's responsibility and further engagement is critical. It is also crucial that such partnership is seen as an avenue for learning for all stakeholders (Government, research community, and local community) rather than a top-down information-sharing approach typically assumed from the government/research community to the local communities. This is important as engagement protocols designed with the community rather than for the community elicit better community response and success rate. In this sense, an engagement protocol designed with the community will imply the co-production of knowledge whereby the community is involved as an active stakeholder in the design and decision-making process for seeking solutions to the community-centered challenges. As Risse (2023) puts it in the discourse on the need for indigenous community voices and involvement in scientific and policy discussions, the discussion on geoengineering must not be separated from the topics and solutions these indigenous communities value. Rather, indigenous viewpoints must be taken in a broader context and systematically interrogated globally.

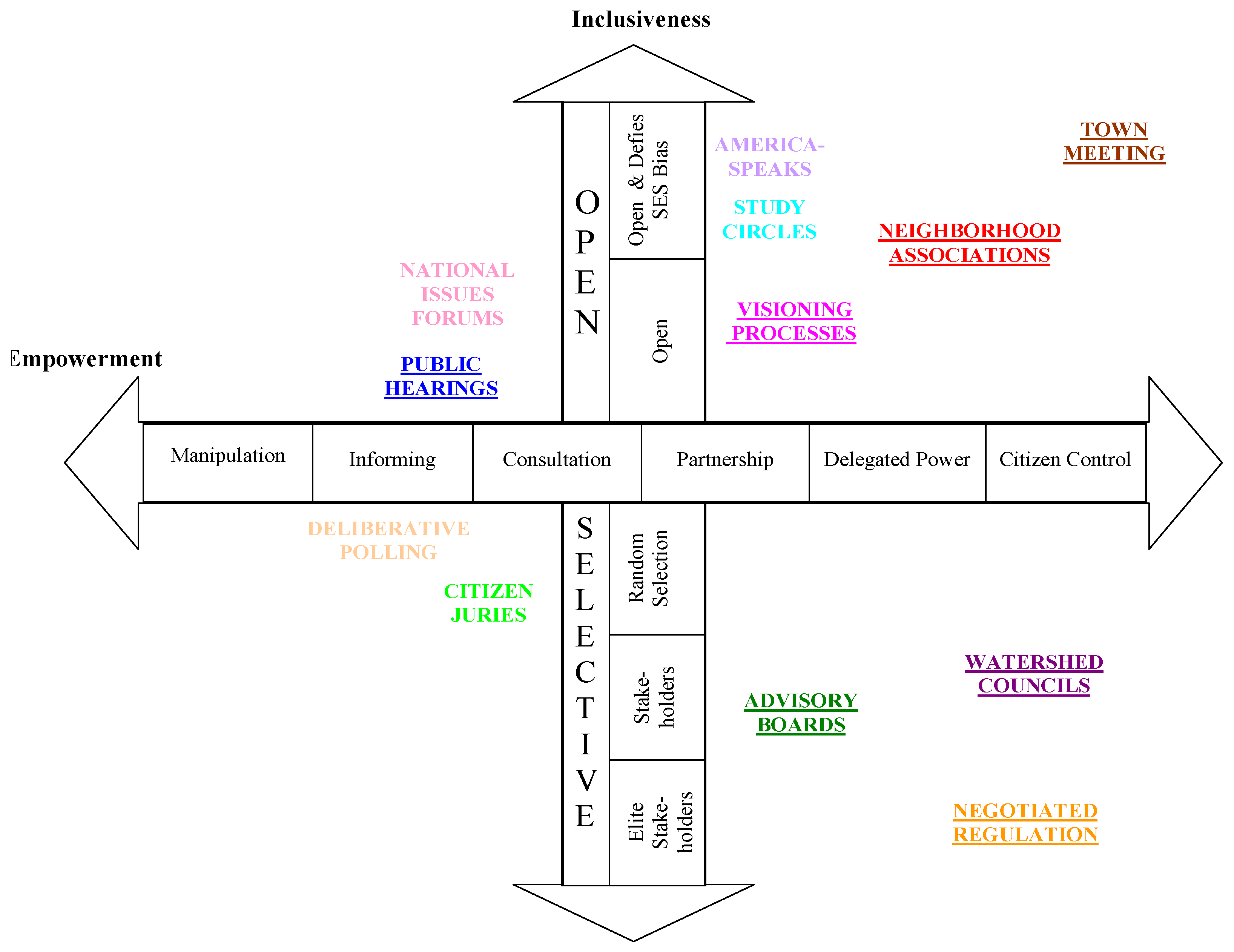

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine's (2021) Participatory technology assessment model makes perfect sense in relation to this recommendation. Here, it allows for the integration of 'new voices into science policy discussion' by incorporating public deliberative techniques such as citizens' juries, citizens' assembles, consensus conferences, and workshops, among others. Bearing this in mind, as seen in

Figure 1 below, Williamson and Fung's (2005) map of deliberative venues brings to bear several templates for deliberative engagement for community empowerment and inclusivity. The figure presents empowerment templates from 'manipulation' by the research team or government in a top-down approach to informing, consultation, partnership, delegated power, and citizen control. Within these many suggestive templates for engagement, designing engagement protocols that are situated within the ambits of consultation and partnership while taking into cognizance open discussion and a flow between elite purposive (those with in-depth knowledge of the topic) and randomized selection (those with little or no knowledge on the topic) of stakeholders will be an ideal template for public engagement on geoengineering issue.

It is also important that the engagement protocol is designed to allow a level playing field for interaction by all stakeholders. This provides a strategic deliberative atmosphere where equitability is a guiding principle for engagement (Mach et al., 2020). In view of this, a 'save space' for engagement that allows less power play in terms of the influence of one stakeholder over another should be the design goal. In the same vein, the exercise should be designed to allow for interactive and strategic engagement in gathering all perspectives rather than for planning or forecasting. In this sense, there is a need for all stakeholders to be involved in the design from the outset, leading to an improved understanding of the process, support for the Policy as well as research efficacy (Mach et al., 2020)

- 2.

Closely related to strategic partnership is the need by the government and research community to closely align research objectives in line with the community's needs and peculiarities. Understanding the community's needs and peculiarity will inform which climate intervention strategy and direction will benefit the community. For instance, the peculiarities of a temperate region coupled with the livelihood options of such a community should influence the type of geoengineering/climate intervention strategies in terms of research and eventual deployment pathways. This supports Mach et al.'s (2020:5) argument that the underlining research goal should be to address societal challenges in such a manner that allows the production of "usable information" through stakeholders' interaction. This assertion is also supported by Lemos et al.'s (2018) postulation on the growing notion that such collaboration will increase usability in policymaking and practice. AS the NASEM (2021) participatory technology assessment noted, a collaborative engagement with the community minimizes the chance of the research team missing latent areas of public concern, leading to integration in knowledge created from the problem-framing phase to result integration. In this sense, the interest of public good is pursued rather than self-exploration on the part of the researchers/elite community.

As observed in the Covid-19 response, governmental policies should be designed in view of public opinion while closely aligning such policies with expert views and global best practices. This strategy is important for Solar geoengineering public engagement as it presents a hybrid public engagement protocol influenced by both public and expert views. While risk is perceived from empirical evidence, the public perceives risk based on popular opinion. This perceived risk is generally high due to the insufficiency of the accuracy of the information available on the issues at hand (Paek, 2016). This was particularly true in the early period of the Covid-19 pandemic. Public perception of the risk of Covid-19 was high and on the verge of instilling panic globally. The same can be said of Solar geoengineering research and application as the public knowledge of Solar geoengineering is generally low and, in some quarters, largely nonexistent. Therefore, for geoengineering engagement, it is pertinent that the design of a hybrid public engagement protocol takes into cognizance the level of community knowledge on geoengineering.

Given this, expert opinion and knowledge must be strategically communicated with less jargon for the community's use. Again, while community needs, views, and perspectives are seriously considered, there is a need for community learning whereby experts' views guide public engagement's direction, leading to a controlled form of knowledge co-production. This is supported by White et al.'s (2015) postulation on collaborative work as a two-way communication process that allows for the fusion of scientists and community ideas.

- 3.

Considering the moral dilemma geoengineering application emanates from the premise of sustainable development and climate justice, among others, especially from the perspectives of public opinion, the need to consider the ethics of practice for geoengineering engagement cannot be over-emphasized. In this sense, all necessary immediate, short, and long-term protocols must be carefully considered. The research needs to understand the potential/risks of Solar geoengineering engagement in future 'emergency' situations (Parker and Irvine, 2018). Also, Solar geoengineering engagement should be motivated and guided by the need to address societal needs (Morrow, 2020) rather than ambitious attempts by science to satisfy a hypothesis or scientific fantasies. As observed in the Covid-19 response, science, research, and policy responses were guided by the need to meet immediate and long-term solutions in curtailing the pandemic impact while being mindful of public opinion. Similarly, public opinion and the need to meet societal needs must guide Solar geoengineering engagements.

In the same vein, for a successful Solar geoengineering engagement, the involvement of religious and social structures is critical. This includes religious institutions such as churches/mosques, local NGOs, community leaders, and social influencers, among others, as these groups have access to the general community (Clingerman and O'Brien, 2014; Jinnah, Nicholson, and Flegal, 2018). The engagement must be designed to allow for transparency by all stakeholders involved, bearing in mind the need to consider divergent views seriously.

- 4.

Like other science and human engagements, Solar geoengineering research and application require monitoring and governance to avoid the stakeholders' excesses (Bas and Mahajan, 2019). The WHO role at the peak of the pandemic in terms of leadership and direction is a viale example in this regard. The recent case of the Stratospheric Aerosol Transport and Nucleation (SATAN) equipment test in September 2022 by some U.K. researchers (Temple, 2023) as well as the American start-up company 'Make Sunsets' balloons launch into the stratosphere to release sulfur dioxide (Ricke, 2023) begs for urgent need for governance mechanism on geoengineering. The lack of a governance mechanism in place would explains why these attempts were possible without regulations.

The need for a governance framework on the modus operandi of geoengineering research and application is important to curtail this trend and the imminent crisis that may ensue should countries take unilateral actions based on their power dynamics. Hence, there is a need to design a global governance structure resembling the United Nations (see Armeni and Redgwell, 2015). This, on a minimum, can be in the form of a loosely coordinated international program by multiple independent teams working coordinately to access issues such as standards of ethics, research integrity, and management of risks. This aligns with Lawrence and Schafer's (2019:830) suggestion on the need for "functioning sets of democratic global institutions rather than clinging to fantasies about centralized, detached steering" should global warming exceed 2

0C. This will allow for national commitments and consideration in designing and implementing future Solar geoengineering research and engagement. It will also allow for a general observance of necessary protocols for approval and monitoring of geoengineering engagements, which will allow for necessary 'save' glocal

iv engagements. This kind of country-level governance protocol will not only set regulations and transparency but ensure state and non-state actors' engagement in Solar geoengineering.

- 5.

The Covid-19 pandemic response strategies show that media influence and sensitization cannot be ignored. While the media provided platforms for public engagement and sensitization, it also allowed for the spread of disinformation and fake news (Fallis, 2014; Christensen, 2022). In this case, we may ask, 'What constitutes too much or too little media coverage in terms of geoengioneering?'

The media was instrumental in information sharing, alleviating panic trends, and guiding research and policy formation throughout the pandemic. Noting that geoengineering research and engagement are still unpopular across several quarters (Rahman et al., 2018; Patrick, 2021), it is impossible to engage the communities in a topic they know little or nothing about. The engagement of uninformed people poses a risk to themselves and others when given the power to decide on an unknown subject matter. This is dangerous and presents a case whereby persuasive orators can easily sway people in any direction, even against their benefits. This assertion is supported by Mach et al. (2017), who argued that unstructured group interaction could be subject to groupthink and other confirmatory biases. In this sense, there is a need for intensive and intentional Solar geoengineering media engagements to help educate the public on Solar geoengineering in general. These media engagements will help put Solar geoengineering discussions on the table of public engagement and will be beneficial when public opinion and engagement become necessary.

Conclusion

This paper explored the Covid-19 pandemic responses to draw lessons for Solar geoengineering engagement. While there has been relevant scholarship on public engagement relating to geoengineering (See Carret al., 2013; Bellamy and Lezaun, 2015; Bellamy, Chilvers and Vaughan, 2016; Burns et al., 2016; Bellamy, Lezaun, and Palmer, 2017), this paper provides a reflection on possible lessons from Covid-19 in terms of society’s vertical and horizontal adaptive and coping mechanism during the peak of the pandemic. We inferred that the adaptive responses to the Covid-19 pandemic buttress the need for more transdisciplinary global engagement in terms of anticipatory governance and research in leu of future global emergencies. In this vein, climate intervention strategies such as solar geoengineering requires proactiveness rather than reactiveness. In view of this, as a lesson for effective geoengineering engagement, there is a need to develop strategic partnerships among various stakeholders, create an alignment between research objectives and the community's needs and peculiarities, consider the ethics of practice and develop a monitoring and governance framework to avoid the stakeholders' excesses. In this sense, intensity in engagements in terms of finding appropriate standards of practice and governance, enquiring on the general perception of people on research and outdoor experiments, viability, and implication of application, among others, become essential. Given this, there is the need for a bottom-up approach to these engagements, as seen in the vertical and horizontal Covid-19 adaptive responses. The widespread engagement during the Covid-19 pandemic led to a robost coping mechanism and popular acceptance of the pandemic's need to move past ordeals. This engagement protocol is also necessary for geoengineering engagement.

Reference

[i] By Vertical, we mean Government to Community

relations (Top-down approach). Horizontal implies relationships at same level

(Communities/individuals to Communities/Individuals; Government to Government).

[ii] The 7 articles were

Buck et al., 2020; Radunsky & Cadman, 2021; Sarnoff, 2020; 2021 Murray

& DiGiorgio, 2021; Cathcart & Finkl, 2022; and Polo, Quirós, &

Felicísimo, 2021.

[iii] By this, we mean all forms of

misinformation and distortion of facts (conspiracy theories). A popular

distortion is that the disease was an elite agenda to amass wealth at the

detriment of the general masses by introducing a virus and the attendant

vaccine for economic reasons. Another is that the disease was a political

agenda to ensure power transfer and or maintenance (This may explain the

argument around China’s mask diplomacy and the continuous Trump accusation of

China as the virus ground Zero). Also, there are misinformation that the

disease is the disease of the rich. Hence, poor people are immune from

contracting the virus. Another is the obvious denial on the existence of the

virus.

[iv] By “glocal,” we mean the

consideration of local dynamics in the implementation and application of a

globalized phenomenon. In this case, while solar geoengineering application

should be considered from a global impact perspective, the local impact for

communities and households must also be taken into serious consideration.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Alvaredo, F.; Chancel, L.; Piketty, T.; Saez, E. ; ZucmanG. (2018) The elephant curve of global inequality and growth. In AEA Papers and Proceedings (Vol. 108, pp. 103–08).

- Armeni, C.; Redgwell, C. (2015) International legal and regulatory issues of climate geoengineering governance: rethinking the approach. Arts and Humanities Research Council: Swindon, U.K.

- Asayama, S.; Emori, S.; Sugiyama, M.; Kasuga, F.; Watanabe, C. (2021) Are we ignoring a black elephant in the Anthropocene? Climate change and global pandemic as the crisis in health and equality. Sustainability Science.

- Bal, P.K.; Pathak, R.; Mishra, S.K.; Sahany, S. (2019) Effects of global warming and Solar geoengineering on precipitation seasonality. Environmental Research Letters, 14(3), p.034011. [Google Scholar]

- Barrage, L. (2020) The Fiscal Costs of Climate Change. In AEA Papers and Proceedings (Vol. 110, pp. 107–12).

- Bellamy, R.; Chilvers, J.; Vaughan, N.E. Deliberative mapping of options for tackling climate change: citizens and specialists' open up'appraisal of geoengineering. Public Understanding of Science 2016, 25, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamy, R.; Lezaun, J.; Palmer, J. Public perceptions of geoengineering research governance: An experimental deliberative approach. Global Environmental Change 2017, 45, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Oomen, J.; Gupta, A.; Ali, S.H.; Conca, K.; Hajer, M.A.; Kashwan, P.; Kotzé, L.J.; Leach, M.; Messner, D.; Okereke, C. (2022) Solar geoengineering: The case for an international non-use agreement. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, e754.

- Bonfiglioli, C. (2021) Global Media Ethics and the Covid-19 Pandemic. In Handbook of Global Media Ethics (pp. 823–843). Springer, Cham.

- Buck, H.; Geden, O.; Sugiyama, M.; Corry, O. Pandemic politics—lessons for Solar geoengineering. Communications Earth & Environment 2020, 1, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, E.T.; Flegal, J.A.; Keith, D.W.; Mahajan, A.; Tingley, D.; Wagner, G. What do people think when they think about Solar geoengineering? A review of empirical social science literature, and prospects for future research. Earth's Future 2016, 4, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, W.A.; Preston, C.J.; Yung, L.; Szerszynski, B.; Keith, D.W.; Mercer, A.M. Public engagement on solar radiation management and why it needs to happen now. Climatic change 2013, 121, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cathcart, R.B. ; Finkl CW (2022) Prospective Aquatic Brandscaping Megaproject Addressing Climate Change Coronavirus of the Coastal Californias: The Intersection of Natural Anthropic 2020, A.D. Impacts. In COVID-19 and a World of Ad Hoc Geographies (pp. 2211–2228). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Clingerman, F.; O'Brien, K.J. Playing God: Why religion belongs in the climate engineering debate. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 2014, 70, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felgenhauer, T. , Horton, J., Keith, D. (2021) Solar geoengineering research on the U.S. policy agenda: when might its time come? Environmental Politics, 1-21.

- Framework Related to Solar Radiation Modification. Office of Science and Technology Policy, Washington, DC, USA.

- Fry, C.V.; Cai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wagner, C.S. Consolidation in a crisis: Patterns of international collaboration in early COVID-19 research. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0236307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hans, G. (2020). Macron warns E.U. could 'collapse' over coronavirus – 'The whole of Europe will fall. Express. https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/1273663/EU-coronavirus-latest-updates-Emmanuel-Mac ron-France-Germany-Italy-bailout. Accessed 30 May 2022.

- Haroon, O. , Rizvi, S.A.R. COVID-19: Media coverage and financial markets behavior—A sectoral inquiry. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 2020, 27, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevia, C.; Neumeyer, A. (2020) A conceptual framework for analyzing the economic impact of COVID-19 and its policy implications. UNDP Lac COVID-19 Policy Documents Series.

- Hourdequin, M. Geoengineering justice: the role of recognition. Science, Technology, & Human Values 2019, 44, 448–477. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, W.; Lu, F. (2021) U.S. media's coverage of China's handling of COVID-19: Playing the role of the fourth branch of government or the fourth estate? Global Media and China.

- Jinnah, S.; Nicholson, S.; Flegal, J. Toward legitimate governance of Solar geoengineering research: a role for sub-state actors. Ethics, Policy & Environment 2018, 21, 362–381. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, D.W. Toward constructive disagreement about geoengineering. Science 2021, 374, 812–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, B.; MacMartin, D.G. Uncertainty and the basis for confidence in Solar geoengineering research. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2020, 1, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, M.; Crutzen, P.J. (2021) Was Breaking the Taboo on Research on Climate Engineering via Albedo Modification a Moral Hazard, or a Moral Imperative? (2016/2017). In Paul J. Crutzen and the Anthropocene: A New Epoch in Earth's History (pp. 253–265). Springer, Cham.

- Lemos, M.C.; Arnott, J.C.; Ardoin, N.M.; Baja, K.; Bednarek, A.T.; Dewulf, A.; Fieseler, C.; Goodrich, K.A.; Jagannathan, K.; Klenk, N.; Mach, K.J. To co-produce or not to co-produce. Nature Sustainability 2018, 1, 722–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, I.D.; Oppenheimer, M. On the design of an international governance framework for geoengineering. Global Environmental Politics 2014, 14, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, K.J.; Lemos, M.C.; Meadow, A.M.; Wyborn, C.; Klenk, N.; Arnott, J.C.; Ardoin, N.M.; Fieseler, C.; Moss, R.H.; Nichols, L.; Stults, M. Actionable knowledge and the art of engagement. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2020, 42, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, K.J.; Mastrandrea, M.D.; Freeman, P.T.; Field, C.B. Unleashing expert judgment in assessment. Global Environmental Change 2017, 44, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolakis, S.; Kennedy, R.J. (2012). Liveable city project: Desktop review of liveability indices.

- McCartney, G. The impact of the coronavirus outbreak on Macao. From tourism lockdown to tourism recovery. Current Issues in Tourism 2021, 24, 2683–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, D.; Corry, O. Clash of Geofutures and the Remaking of Planetary Order: Faultlines underlying Conflicts over Geoengineering Governance. Global Policy 2021, 12, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, D.P. Whose climate and whose ethics? Conceptions of justice in Solar geoengineering modelling. Energy Research & Social Science 2018, 44, 209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, I. Political perspectives on geoengineering: navigating problem definition and institutional fit. Global Environmental Politics 2020, 20, 57–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, D.R. (2020) A mission-driven research program on Solar geoengineering could promote justice and legitimacy. Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2021) Pathways to Discovery in Astronomy and Astrophysics for the 2020s. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Navari, C. (2016) Hans Morgenthau and the National Interest. Ethics and International Affairs. [CrossRef]

- Olapegba, P.O.; Ayandele, O.; Kolawole, S.O.; Oguntayo, R.; Gandi, J.C.; Dangiwa, A.L.; Ottu, I.F.; Iorfa, S.K. (2020) A preliminary assessment of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) knowledge and perceptions in Nigeria. Available at SSRN 358 4408.

- Oosterhoff, B.; Palmer, C.A. (2020) Psychological correlates of news monitoring, social distancing, disinfecting, and hoarding behaviors among U.S. adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- OSTP. (2023). Congressionally Mandated Research Plan and an Initial Research Governance.

- Paek, H. J. (2016) Effective risk governance requires risk communication experts" Epidemiology and health, 38, 1-2.

- Pamplany, A.; Gordijn, B.; Brereton, P. The ethics of geoengineering: a literature review. Science and Engineering Ethics 2020, 26, 3069–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.; Irvine, P.J. The risk of termination shock from Solar geoengineering. Earth's Future 2018, 6, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, H.O. (2021) Review of Solar geoengineering from a Social Science Viewpoint: A Discourse on the Impact on Policy and Livelihood for the Developing World. African Journal of Inter/Multidisciplinary Studies. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, H.O.; Abiolu, R.T.I.; Abiolu, O.A. (2021a) Covid-19 and the viability of curriculum adjustment and delivery options in the South African educational space. Journal of Transformation in Higher Education. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, H.O.; Khalema, E.N.; Ijatuyi, E.J.; Abiolu, O.A.; Abiolu, R.T.I. (2021b). South Africa's multiple vulnerabilities, food security, and livelihood options in the Covid-19 new order: An Annotation. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, H.O.; Omoge, O.; Usman, H. (2021c) An Appraisal of the Multifaceted Effects of Coronavirus on the Sport Industry. African Journal of Sociological and Psychological Studies. 1. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, H.O.; Khalema, E.; Abiolu, R.T.I.; Mbara, G. (2021d) National Interest and Collective Security: Assessing the 'Collectivity' of Global Security in the Covid-19 Era. Humanities and Social Sciences Review. [CrossRef]

- Polo, M.E.; Quirós, E.; Felicísimo, Á.M. Geoengineering Education for Management of Geospatial Data in University Context. Journal of Surveying Engineering 2021, 147, 05021001.Murray, E. G., DiGiorgio, A. L. (2021). Will individual actions do the trick? Comparing climate change mitigation through geoengineering versus reduced vehicle emissions. Earth's Future, 9(3), e2020EF001734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, P.B.; Poudel, M.R.; Gautam, A.; Phuyal, S.; Tiwari, C.K.; Bashyal, N.; Bashyal, S. COVID-19 and its global impact on food and agriculture. Journal of Biology and Today's World 2020, 9, 221–225. [Google Scholar]

- Radunsky, K.; Cadman, T. (2021). Addressing Climate Change Risks: Importance and Urgency. In Handbook of Climate Change Management: Research, Leadership, Transformation (pp. 1405–1431). Cham: Springer International Publishing. Sarnoff, J. D. Negative-emission technologies. and patent rights after COVID-19. Climate Law 2020, 10, 225.

- Rahman, A.A.; Artaxo, P.; Asrat, A.; Parker, A. (2018) Developing countries must lead on Solar geoengineering research.

- Ricke, K. Solar geoengineering is scary-that's why we should research it. Nature 2023, 614, 391–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnoff, J.D. Negative-emission technologies and patent rights after COVID-19. Carbon Capture and Storage in International Energy Policy and Law 2021, 205–231. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, L.M. (2021) The politics of green taxation. In Handbook on the Politics of Taxation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Sharma, G. Pros and cons of different sampling techniques. International journal of applied research 2017, 3, 749–752. [Google Scholar]

- Talberg, A.; Thomas, S.; Christoff, P.; Karoly, D. How geoengineering scenarios frame assumptions and create expectations. Sustainability Science 2018, 13, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J. (2023) Researchers launched a Solar geoengineering test flight in the U.K. last fall. MIT Technology Review. technologyreview.com/2023/03/01/1069283/researchers-launched-a-solar-geoengineering-test-flight-in-the-uk-last-fall/.

- Teoh, J.Y.C.; Ong, W.L.K.; Gonzalez-Padilla, D.; Castellani, D.; Dubin, J.M.; Esperto, F.; Campi, R.; Gudaru, K.; Talwar, R.; Okhunov, Z.; Ng, C.F. A global survey on the impact of COVID-19 on urological services. European urology 2020, 78, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trisos, C.H.; Gabriel, C.; Robock, A.; Xia, L. (2018) Ecological, Agricultural, and Health Impacts of Solar geoengineering. In Resilience (pp. 291–303). Elsevier.

- Webb, J.A.; Miller, K.A.; Stewardson, M.J.; de Little, S.C.; Nichols, S.J.; Wealands, S.R. An online database and desktop assessment software to simplify systematic reviews in environmental science. Environmental Modelling & Software 2015, 64, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.L.; Sutton, A.E.; Salguero-Gómez, R.; Bray, T.C.; Campbell, H.; Cieraad, E.; Geekiyanage, N.; Gherardi, L.; Hughes, A.C.; Jørgensen, P.S.; Poisot, T. The next generation of action ecology: novel approaches towards global ecological research. Ecosphere 2015, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A.; Fung, A. (2005) Mapping public deliberation. A report for the William and Flora Hewlitt Foundation.

- World Health Organization. (2021) Global research on coronavirus disease (COVID-19. World Health Organization. ttps://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/global-research-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov.

- Zambrano-Monserrate, M.A.; Ruano, M.A.; Sanchez-Alcalde, L. Indirect effects of COVID-19 on the environment. Science of the total environment 2020, 728, 138813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinn, J.O. A monstrous threat': how a state of exception turns into a 'new normal. Journal of Risk Research 2020, 23, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallis, D. The varieties of disinformation. The philosophy of information quality 2014, 135–161. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, M. Disinformation and the return of mass society theory. Canadian Journal of Communication 2022, 47, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| i |

By Vertical, we mean Government to Community relations (Top-down approach). Horizontal implies relationships at same level (Communities/individuals to Communities/Individuals; Government to Government). |

| ii |

The 7 articles were Buck et al., 2020; Radunsky & Cadman, 2021; Sarnoff, 2020; 2021 Murray & DiGiorgio, 2021; Cathcart & Finkl, 2022; and Polo, Quirós, & Felicísimo, 2021. |

| iii |

By this, we mean all forms of misinformation and distortion of facts (conspiracy theories). A popular distortion is that the disease was an elite agenda to amass wealth at the detriment of the general masses by introducing a virus and the attendant vaccine for economic reasons. Another is that the disease was a political agenda to ensure power transfer and or maintenance (This may explain the argument around China’s mask diplomacy and the continuous Trump accusation of China as the virus ground Zero). Also, there are misinformation that the disease is the disease of the rich. Hence, poor people are immune from contracting the virus. Another is the obvious denial on the existence of the virus. |

| iv |

By “glocal,” we mean the consideration of local dynamics in the implementation and application of a globalized phenomenon. In this case, while solar geoengineering application should be considered from a global impact perspective, the local impact for communities and households must also be taken into serious consideration. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).