Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

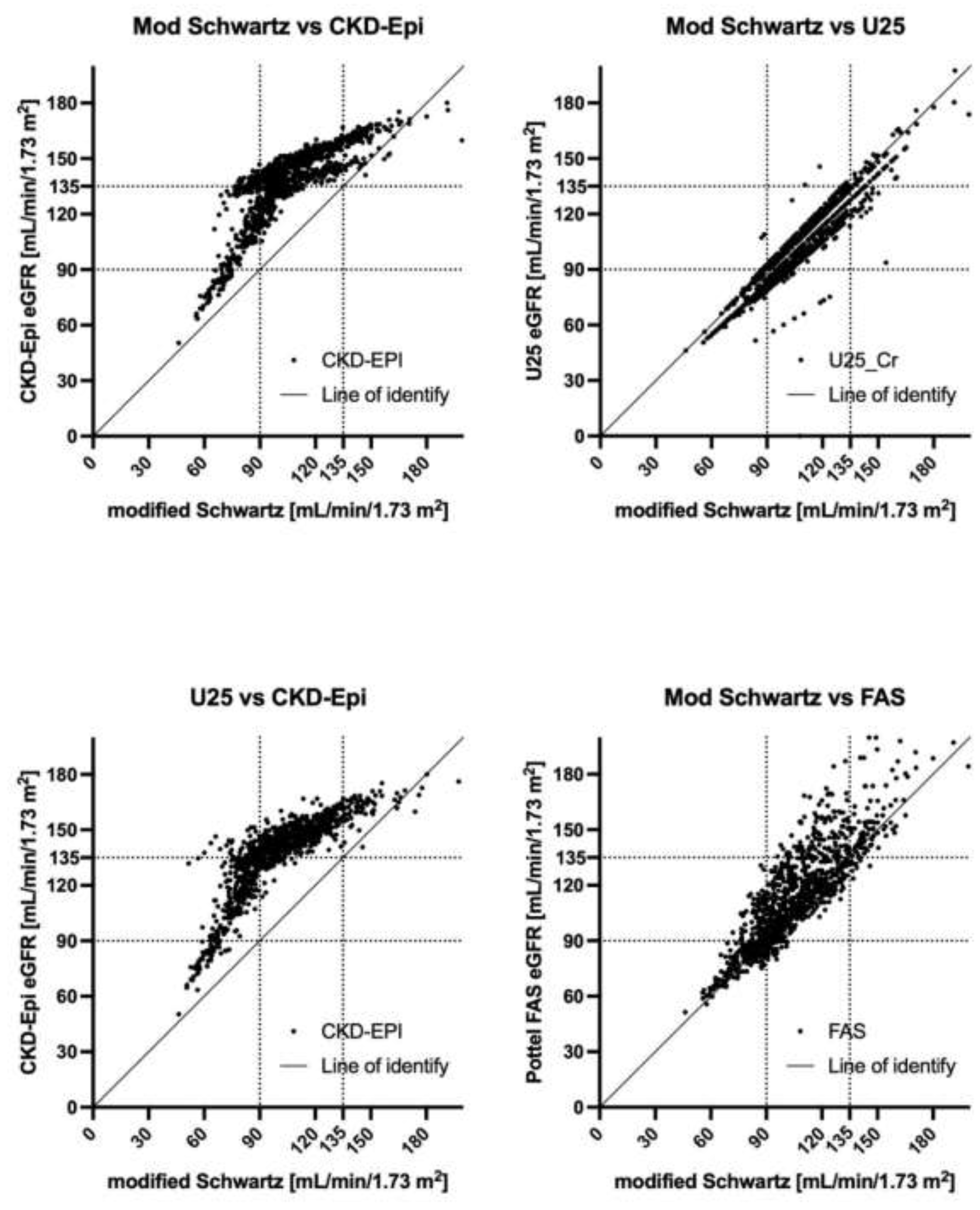

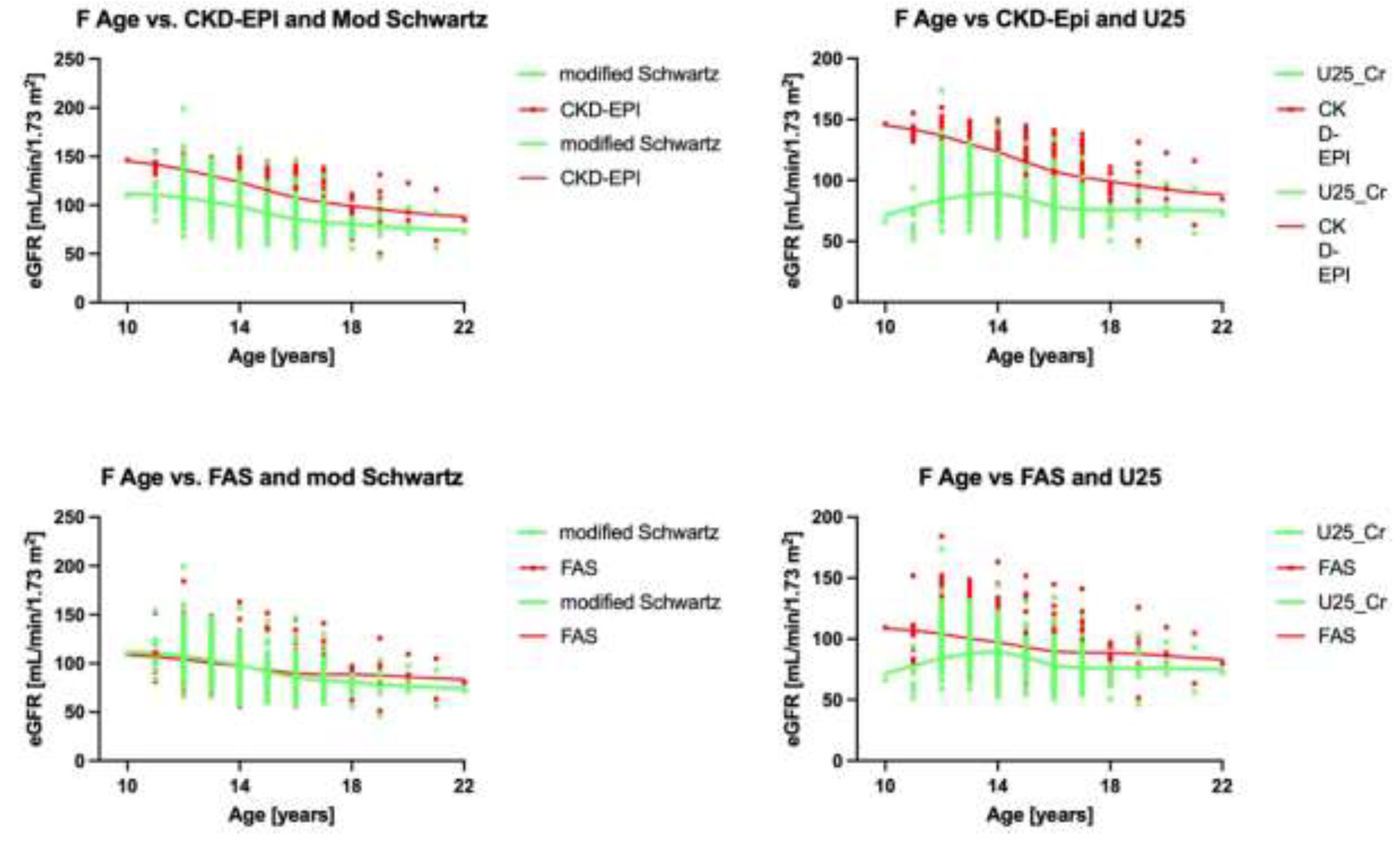

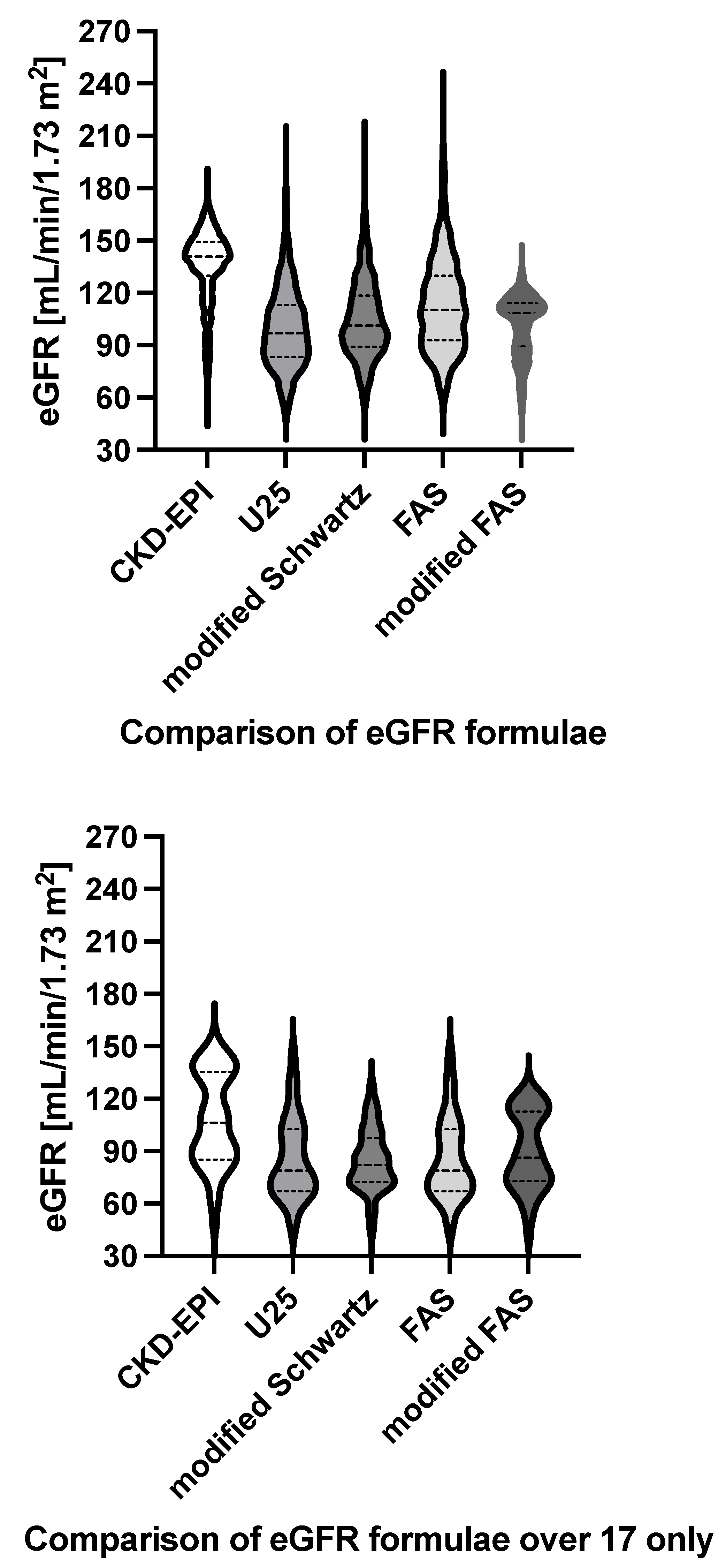

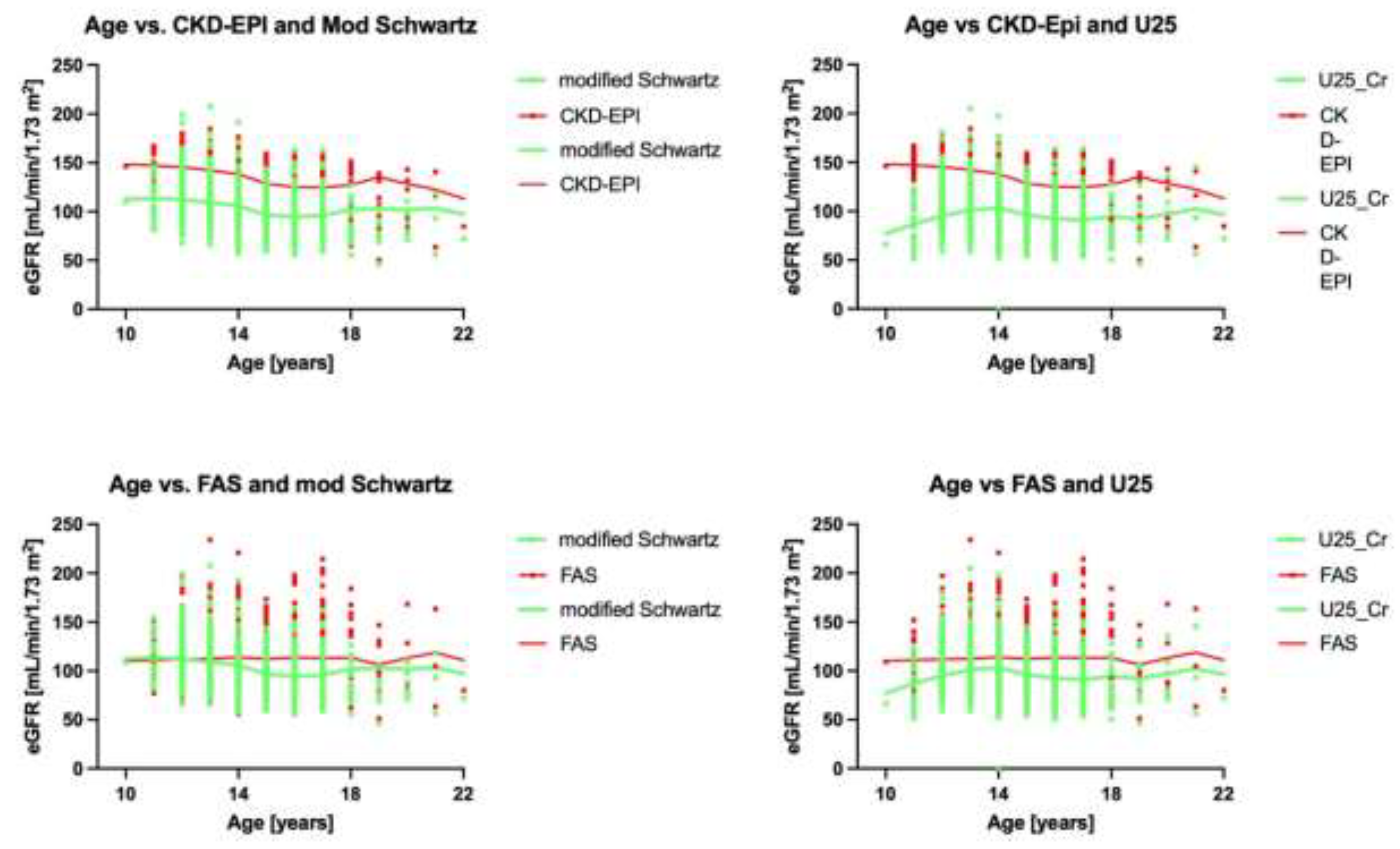

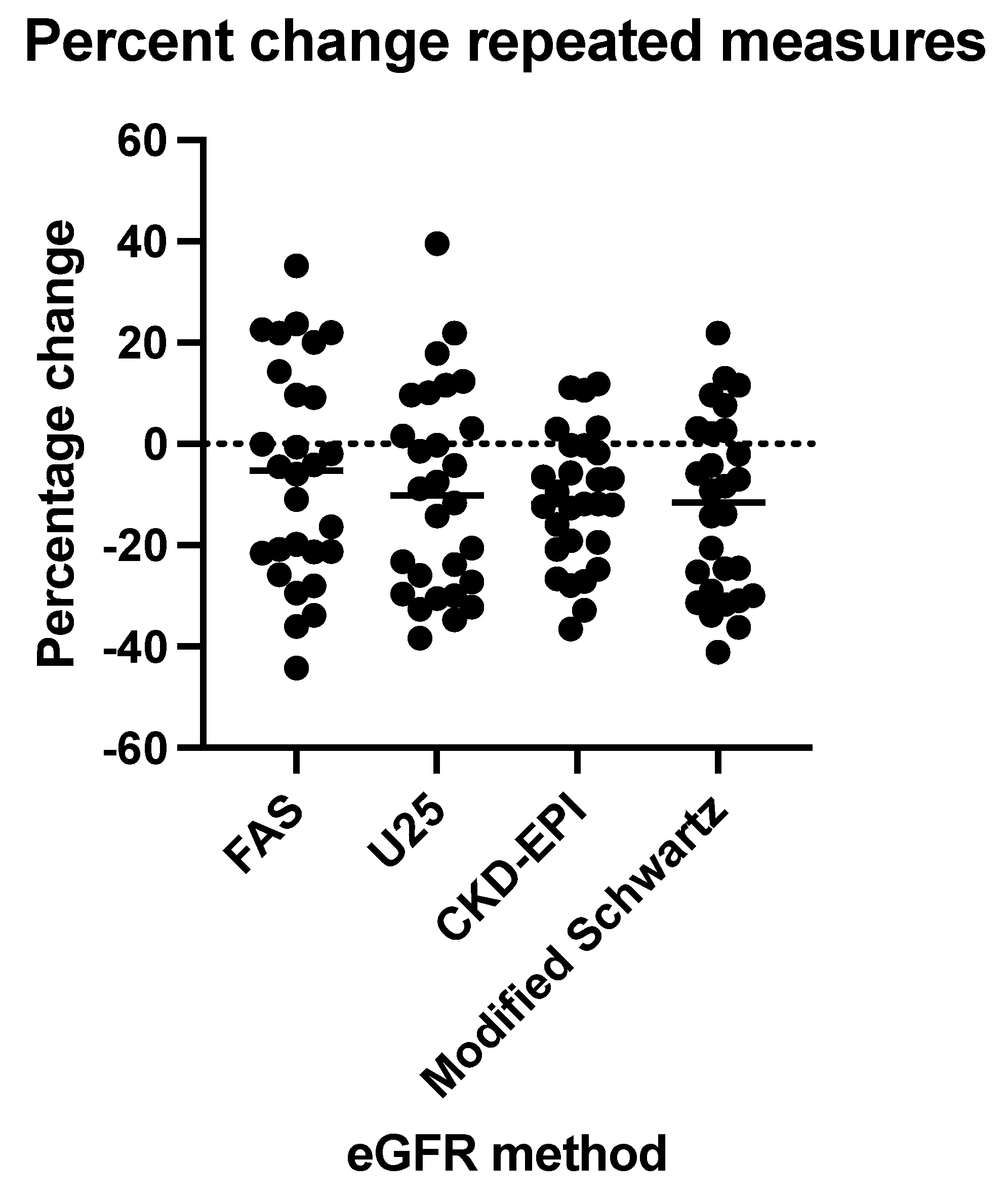

Background: Guidelines recommend switching the glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) estimation from the CKiD-U25 to the CKD-EPI formula at age 18. We investigated how this would affect chronic kidney disease (CKD) classification. Methods: Serum creatinine was enzymatically measured in 1061 samples from 914 community-based 10-23-year-olds from Tlaxcala, Mexico, a region where urinary biomarkers demonstrated early kidney damage associated with exposure to inorganic toxins in a pediatric population. We calculated their eGFR using CKiD-U25, modified Schwartz, the first and modified Pottel full-age spectrum (FAS), and CKD-EPI formulae. Correlation analysis characterized the CKD stage stratified by age and sex. Results: At baseline, the median age was 13 (IQR:12,15) years, and 55% were female. Median CKiD-U25 eGFR was 96.9 (IQR:83.3,113.3) mL/min/1.73m2, significantly lower than the CKD-EPI eGFR which was 140.8 (IQR:129.9,149.3) mL/min/1.73m2 (p<0.0001, Wilcoxon rank test). The mean bias was 36.9912.89 mL/min/1.73 m2. Pearson correlation was r=0.8296 (95% confidence interval 0.0898-0.8474). There was a better correlation between the modified Schwartz (r=0.9421(0.9349,0.9485)) and the Pottel FAS (r=0.9299(0.9212,0.9376)) formulae. Agreement was deficient when the eGFR was >75mL/min/1.73 m2 in younger age and female sex. Modified Schwartz identified 281(26.4%) measurements as having CKD 2 and 3 (2+), U25 identified 401 (37.7%) measurements as having CKD 2+, FAS identified 267 (25.1%) and modified FAS identified 282 (30%) measurements as having CKD 2+, and CKD-EPI identified 51 (4.8%) measurements as having CKD 2+, respectively. Conclusions: In this population, there needed to be better agreement between the various eGFR formulae. CKD-EPI identifies substantially fewer at-risk participants as having CKD.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Setting, Participants, Ethics, and Funding

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Analysis of all GFR Estimations

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.4. Analysis by Age

3.5. Classification of CKD Stages

3.6. Subgroup Analysis for ≥18 Years of Age Only

3.7. Subgroup Analysis for Hyperfiltration

3.8. Subgroup Analysis of Longitudinal eGFR Measurements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of interest and funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Filler, G.; Ferris, M.; Gattineni, J. Assessment of Kidney Function in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. In Pediatr Nephrol; Emma, F., Goldstein, S., Bagga, A., Bates, C.M., Shroff, R., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Margalit, R.; Golan, E.; Twig, G.; Leiba, A.; Tzur, D.; Afek, A.; Skorecki, K.; Vivante, A. History of Childhood Kidney Disease and Risk of Adult End-Stage Renal Disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingelfinger, J.R. A Disturbing Legacy of Childhood Kidney Disease. The New England journal of medicine 2018, 378, 470–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyckx, V.A.; Shukha, K.; Brenner, B.M. Low nephron number and its clinical consequences. Rambam Maimonides medical journal 2011, 2, e0061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, B.M.; Lawler, E.V.; Mackenzie, H.S. The hyperfiltration theory: A paradigm shift in nephrology. Kidney Int. 1996, 49, 1774–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, E.T.; Wuhl, E.; Trivelli, A.; Picca, S.; Litwin, M.; Peco-Antic, A.; et al. Strict blood-pressure control and progression of renal failure in children. The New England journal of medicine 2009, 361, 1639–50. [Google Scholar]

- Filler, G.; Yasin, A.; Medeiros, M. Methods of assessing renal function. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2013, 29, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Romero, M.; Jiménez-Córdova, M.I.; Barrera-Hernández, Á.; Sepúlveda-González, M.E.; Narvaez-Morales, J.; Aguilar-Madrid, G.; Juárez-Pérez, C.A.; Del Razo, L.M.; Cruz-Angulo, M.D.C.; Mendez-Hernández, P.; et al. Relationship between urinary biomarkers of early kidney damage and exposure to inorganic toxins in a pediatric population of Apizaco, Tlaxcala, Mexico. J. Nephrol. 2023, 36, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou-Meda, R.; Alvarez-Elías, A.C.; Bonilla-Félix, M. Mesoamerican Endemic Nephropathy (MeN): A Disease Reported in Adults That May Start Since Childhood? Seminars in nephrology 2022, 42, 151337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.J.; Tilde]Oz, A.M.; Schneider, M.F.; Mak, R.H.; Kaskel, F.; Warady, B.A.; Furth, S.L.; Muñoz, A. New Equations to Estimate GFR in Children with CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, C.B.; Muñoz, A.; Ng, D.K.; Warady, B.A.; Furth, S.L.; Schwartz, G.J. Age- and sex-dependent clinical equations to estimate glomerular filtration rates in children and young adults with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2020, 99, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.K.; Pierce, C.B. Kidney Disease Progression in Children and Young Adults With Pediatric CKD: Epidemiologic Perspectives and Clinical Applications. Semin. Nephrol. 2021, 41, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Castro, A.F., 3rd; Feldman, H.I.; et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Annals of internal medicine 2009, 150, 604–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyman, U.; Björk, J.; Berg, U.; Bökenkamp, A.; Dubourg, L.; Goffin, K.; Grubb, A.; Hansson, M.; Larsson, A.; Littmann, K.; et al. The Modified CKiD Study Estimated GFR Equations for Children and Young Adults Under 25 Years of Age: Performance in a European Multicenter Cohort. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 80, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster-Clark, M.; Jaeger, B.; Zhong, Y.; Filler, G.; Alvarez-Elias, A.; Franceschini, N.; de Ferris, M.E.D.-G. Low agreement between modified-Schwartz and CKD-EPI eGFR in young adults: a retrospective longitudinal cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2018, 19, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selistre, L.; Rabilloud, M.; Cochat, P.; de Souza, V.; Iwaz, J.; Lemoine, S.; et al. Comparison of the Schwartz and CKD-EPI Equations for Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate in Children, Adolescents, and Adults: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1001979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottel, H.; Björk, J.; Courbebaisse, M.; Couzi, L.; Ebert, N.; Eriksen, B.O.; et al. Development and Validation of a Modified Full Age Spectrum Creatinine-Based Equation to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate : A Cross-sectional Analysis of Pooled Data. Annals of internal medicine 2021, 174, 183–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filler, G.; Ahmad, F.; Bhayana, V.; Díaz Gonzáles de Ferris, M.; Sharma, A.P. Limitations of U25 CKiD and CKD-EPI eGFR formulae in patients 2-20 years of age with measured GFR>60 mL/min/1.73 m2 – A cross-sectional study. Pediatr Nephrol. in press. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pottel, H.; Hoste, L.; Dubourg, L.; Ebert, N.; Schaeffner, E.; Eriksen, B.O.; Melsom, T.; Lamb, E.J.; Rule, A.D.; Turner, S.T.; et al. An estimated glomerular filtration rate equation for the full age spectrum. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2016, 31, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottel, H.; Adebayo, O.C.; Nkoy, A.B.; Delanaye, P. Glomerular hyperfiltration: part 1 - defining the threshold - is the sky the limit? Pediatr Nephrol. 2023, 38, 2523–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Lee, G.-H.; Kim, H.; Yang, H.S.; Hur, M. Application of the European Kidney Function Consortium Equation to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate: A Comparison Study of the CKiD and CKD-EPI Equations Using the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES 2008–2021). Medicina 2024, 60, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, D.K.; Schwartz, G.J.; Schneider, M.F.; Furth, S.L.; Warady, B.A. Combination of pediatric and adult formulas yield valid glomerular filtration rate estimates in young adults with a history of pediatric chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2018, 94, 170–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottel, H.; Björk, J.; Bökenkamp, A.; Berg, U.; Åsling-Monemi, K.; Selistre, L.; Dubourg, L.; Hansson, M.; Littmann, K.; Jones, I.; et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate at the transition from pediatric to adult care. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellekens, P.; Verjans, M.; Janssens, P.; Dachy, A.; De Rechter, S.; Breysem, L.; Allegaert, K.; Bammens, B.; Vennekens, R.; Vermeersch, P.; et al. Low agreement between various eGFR formulae in pediatric and young adult ADPKD patients. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2023, 38, 3043–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaebe, K.; White, C.A.; Mahmud, F.H.; Scholey, J.W.; Elia, Y.T.; Sochett, E.B.; Cherney, D.Z. Evaluation of novel glomerular filtration rate estimation equations in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes. J. Diabetes its Complicat. 2021, 36, 108081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.P.; Yasin, A.; Garg, A.X.; Filler, G. Diagnostic Accuracy of Cystatin C–Based eGFR Equations at Different GFR Levels in Children. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 1599–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björk, J.; Nyman, U.; Larsson, A.; Delanaye, P.; Pottel, H. Estimation of the glomerular filtration rate in children and young adults by means of the CKD-EPI equation with age-adjusted creatinine values. Kidney Int. 2020, 99, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, O.C.; Nkoy, A.B.; Heuvel, L.P.v.D.; Labarque, V.; Levtchenko, E.; Delanaye, P.; Pottel, H. Glomerular hyperfiltration: part 2—clinical significance in children. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2022, 38, 2529–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.-H.S.; Sharma, A.P.; Yasin, A.; Lindsay, R.M.; Clark, W.F.; Filler, G. Hyperfiltration Affects Accuracy of Creatinine eGFR Measurement. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filler, G.; Lepage, N. Should the Schwartz formula for estimation of GFR be replaced by cystatin C formula? Pediatr Nephrol. 2003, 18, 981–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, O.Z.; Bhayana, V.; Kadour, M.; Lepage, N.; Gowrishankar, M.; Filler, G. Improving the translation of novel biomarkers to clinical practice: The story of cystatin C implementation in Canada: A professional practice column. Clin Biochem. 2017, 50, 380–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE Evidence Reviews Collection. Evidence reviews for cystatin C based equations to estimate GFR in adults, children and young people: Chronic kidney disease: Evidence review M. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Copyright © NICE 2021.; 2021.

- Filler, G.; Torres-Canchala, L.; Sharma, A.P.; Diaz Gonzalez de Ferris, M.E.; Restrepo, J.M. What to do with kidney length and volumes in large individuals? Pediatr Nephrol. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filler, G. Editorial: There Is Still a Need for Kidney Volume Reference Intervals in Large Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Can. J. Kidney Heal. Dis. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filler, G.; de Ferris, M.E.D.G.; Medeiros, M. Ideal rather than actual weight for glomerular filtration rate measurement: an issue to be clarified. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2024, 39, 2537–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inker, L.A.; Tighiouart, H.; Adingwupu, O.M.; Ng, D.K.; Estrella, M.M.; Maahs, D.; Yang, W.; Froissart, M.; Mauer, M.; Kalil, R.; et al. Performance of GFR Estimating Equations in Young Adults. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 83, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | n = 914 |

|---|---|

| Age, years (median, IQR) | 13 (12 – 15) |

| Female Male |

503 (55.0) 411 (45.0) |

| Anthropometry | |

|

Height cm (median, IQR) BMI, n (%) Low weight Normal weight Overweight Obesity |

158 (152, 160) 20 (2.2) 608 (66.5) 171 (18.7) 115 (12.6) |

| BMI kg/m2, (median, IQR) | 21.0 (18.9 – 24.2) |

| WHtR, (median, IQR) | 0.47 (0.44 – 0.52) |

| High blood pressure, n (%) | 82 (8.97) |

| Premature birth <36 weeks gestational, n (%) | 110 (12.04) |

|

Poverty, n (%) No Moderate Extreme |

392 (42.89) 458 (50.11) 64 (7) |

| Kidney parameters | |

| Serum creatinine mg/dL (median, IQR) | 0.62 (0.53 – 0.72) |

| ACR mg/g, (median, IQR) | 4.94 (<LOD – 22.53) |

| ACR mg/g, n (%) < 30 30 - 300 > 300 |

741 (81-07) 169 (18.49) 4 (0.44) |

| CKD-EPI [mL/min/1.73 m2] | U25_Cr [mL/min/1.73 m2] | modified Schwartz [mL/min/1.73 m2] | FAS [mL/min/1.73 m2] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of values | 1061 | 1061 | 1061 | 1061 |

| Minimum | 50.4 | 46.3 | 46.2 | 51.4 |

| 25% Percentile | 129.9 | 83.35 | 89.1 | 92.85 |

| Median | 140.8 | 96.9 | 101.3 | 110.2 |

| 75% Percentile | 149.3 | 113.2 | 118.6 | 129.9 |

| Maximum | 184.4 | 205.2 | 207.9 | 234.1 |

| Range | 134 | 158.9 | 161.7 | 182.7 |

| Mean | 136.2 | 99.34 | 104.7 | 113 |

| Std. Deviation | 20.58 | 22.7 | 22.3 | 26.82 |

| Std. Error of Mean | 0.6318 | 0.6969 | 0.6847 | 0.8233 |

| Lower 95% CI of geo. mean | 133 | 95.5 | 101.2 | 108.4 |

| Upper 95% CI of geo. mean | 135.8 | 98.15 | 103.8 | 111.5 |

| Skewness | -1.179 | 0.6179 | 0.6355 | 0.6794 |

| Kurtosis | 1.356 | 0.7329 | 0.7623 | 0.7172 |

| First measurement | Second measurement | ||||

| CKD stage 1 | CKD stage 2+ | CKD stage 1 | CKD stage 2+ | ||

| Modified Schwartz | 14 | 14 | 7 | 21 | |

| U25 | 12 | 17 | 6 | 22 | |

| FAS | 15 | 13 | 10 | 18 | |

| CKD-EPI | 22 | 6 | 20 | 8 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).