Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Analytical Mechanism of SERS

2.1. Basic Theory of SERS

2.2. Raman Signal Acquisition

2.3. SERS Superiority

2.4. Spectral Statistics Characteristics

3. Sensitizing Effect of Nanostructures Toward SERS Assay

3.1. Classification and Preparation of Nanostructures in SERS

3.1.1. Classification of Nanostructures for Enhancing SERS Signals

3.1.2. Preparation of Nanostructure-Sensitized SERS Substrates

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

3.2. Enhancement Behavior of Nanostructure-Sensitized SERS

3.2.1. Electromagnetic Enhancement Mechanism

3.2.2. Chemical Enhancement Mechanism

3.2.3. “Hot Spots” Formation

3.2.4. Nanostructural Morphology and Composition on Signal Enhancement

3.2.5. Multi-Modal Analysis on Signal Enhancement

4. Nanostructure-Sensitized SERS toward Harmful Substances in Food

4.1. Nanostructure-Sensitized SERS Toward Microbial Contamination in Food

4.1.1. Sensing Toward Foodborne Pathogens

4.1.2. Sensing Toward Fungi, Molds, and Their Toxins

4.1.3. Sensing Toward Viruses

4.2. Nanostructure-Sensitized SERS toward Chemical Contamination in Food

4.2.1. Sensing Toward Pesticide Residues

4.2.2. Sensing Toward Veterinary Drug Residues

4.2.3. Sensing Toward Heavy Metals

4.2.4. Sensing Toward Food Additives and Illicit Adulterants

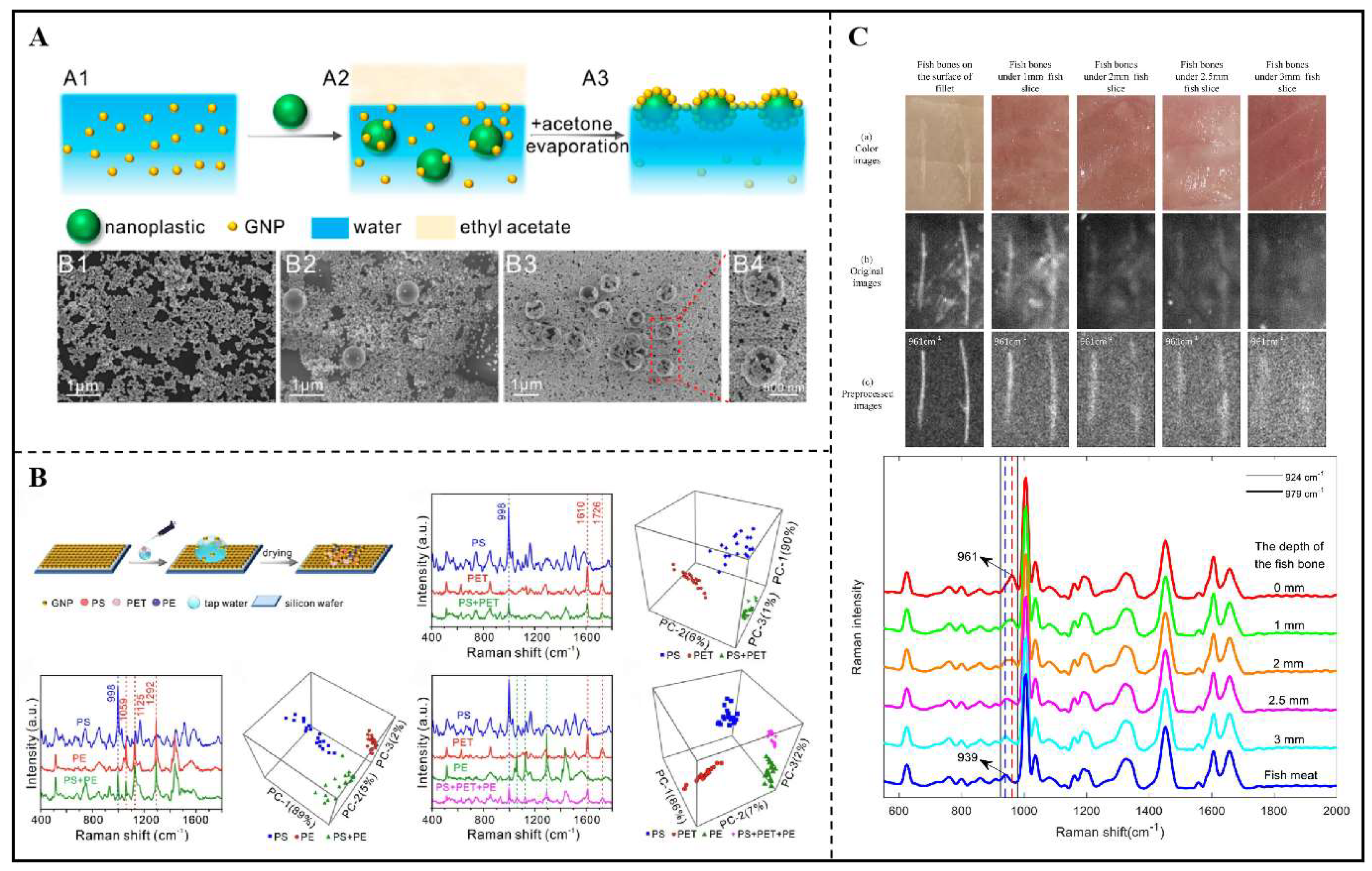

4.3. Nanostructure-Sensitized SERS Toward Physical Contamination in Food

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- W. Jiang, Q. Wang, et al., Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy substrates for monitoring antibiotics in dairy products: Mechanisms, advances, and prospects[J], Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety (2024) 23(6). [CrossRef]

- L. Wu, Y. Li, et al., A dual-mode optical sensor for sensitive detection of saxitoxin in shellfish based on three-in-one functional nanozymes[J], Journal of Food Composition and Analysis (2024) 130. [CrossRef]

- G. Wu, H. Qiu, et al., Nanomaterials-based fluorescent assays for pathogenic bacteria in food-related matrices[J], Trends in Food Science & Technology (2023) 142. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, Y. Lou, et al., Aroma characteristics of volatile compounds brought by variations in microbes in winemaking[J], Food Chemistry (2023) 420. [CrossRef]

- S.-H. Song, Z.-F. Gao, et al., Aptamer-Based Detection Methodology Studies in Food Safety[J], Food Analytical Methods (2019) 12(4) 966-990. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, Y. Zhu, et al., Characteristic substance analysis and rapid detection of bacteria spores in cooked meat products by surface enhanced Raman scattering based on Ag@AuNP array substrate[J], Analytica Chimica Acta (2024) 1308. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guo, M. Wang, et al., Label-free surface enhanced Raman scattering spectroscopy for discrimination and detection of dominant apple spoilage fungus[J], International Journal of Food Microbiology (2021) 338. [CrossRef]

- O.M. Atta, S. Manan, et al., Biobased materials for active food packaging: A review[J], Food Hydrocolloids (2022) 125. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Nasiru, E.B. Frimpong, et al., Dielectric barrier discharge cold atmospheric plasma: Influence of processing parameters on microbial inactivation in meat and meat products[J], Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety (2021) 20(3) 2626-2659. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, W. Zhang, et al., Impedimetric aptasensor based on highly porous gold for sensitive detection of acetamiprid in fruits and vegetables[J], Food Chemistry (2020) 322. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guo, P. Chen, et al., Detection of Heavy Metals in Food and Agricultural Products by Surface-enhanced Raman Spectroscopy[J], Food Reviews International (2021) 39(3) 1440-1461. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guo, P. Chen, et al., Determination of lead in food by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy with aptamer regulating gold nanoparticles reduction[J], Food Control (2022) 132. [CrossRef]

- Y. Rong, S. Ali, et al., Development of a bimodal sensor based on upconversion nanoparticles and surface-enhanced Raman for the sensitive determination of dibutyl phthalate in food[J], Journal of Food Composition and Analysis (2021) 100. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Y. Zhou, et al., Switchable aptamer-fueled colorimetric sensing toward agricultural fipronil exposure sensitized with affiliative metal-organic framework[J], Food Chemistry (2023) 407. [CrossRef]

- W. Wu, W. Ahmad, et al., An upconversion biosensor based on inner filter effect for dual-role recognition of sulfadimethoxine in aquatic samples[J], Food Chemistry (2024) 437. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yue, X. Liu, et al., Reducing microplastics in tea infusions released from filter bags by pre-washing method: Quantitative evidences based on Raman imaging and Py-GC/MS[J], Food Chemistry (2024) 445. [CrossRef]

- F. Yu, C. Qu, et al., Liquid Interfacial Coassembly of Plasmonic Arrays and Trace Hydrophobic Nanoplastics in Edible Oils for Robust Identification and Classification by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy[J], Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry (2023) 71(39) 14342-14350. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shi, L. Yi, et al., Visual characterization of microplastics in corn flour by near field molecular spectral imaging and data mining[J], Science of The Total Environment (2023) 862. [CrossRef]

- C. Xie, W. Zhou, A Review of Recent Advances for the Detection of Biological, Chemical, and Physical Hazards in Foodstuffs Using Spectral Imaging Techniques[J], Foods (2023) 12(11). [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, M. Zhang, et al., Multifunctional Metal–Organic Frameworks Driven Three-Dimensional Folded Paper-Based Microfluidic Analysis Device for Chlorpyrifos Detection[J], Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry (2024) 72(25) 14375-14385. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zou, Y. Shi, et al., Quantum dots as advanced nanomaterials for food quality and safety applications: A comprehensive review and future perspectives[J], Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety (2024) 23(3). [CrossRef]

- M. Mehedi Hassan, P. He, et al., Rapid detection and prediction of chloramphenicol in food employing label-free HAu/Ag NFs-SERS sensor coupled multivariate calibration[J], Food Chemistry (2022) 374. [CrossRef]

- Z. Dong, J. Lu, et al., Antifouling molecularly imprinted membranes for pretreatment of milk samples: Selective separation and detection of lincomycin[J], Food Chemistry (2020) 333. [CrossRef]

- J. Mei, F. Zhao, et al., A review on the application of spectroscopy to the condiments detection: from safety to authenticity[J], Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition (2021) 62(23) 6374-6389. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, M.M. Hassan, et al., A solid-phase capture probe based on upconvertion nanoparticles and inner filter effect for the determination of ampicillin in food[J], Food Chemistry (2022) 386. [CrossRef]

- C. Pan, B. Zhu, et al., A Dual Immunological Raman-Enabled Crosschecking Test (DIRECT) for Detection of Bacteria in Low Moisture Food[J], Biosensors (2020) 10(12). [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, L. Zhu, et al., Recent Advances in Nanomaterials-Based Sensing Platforms for the Determination of Multiple Bacterial Species: A Minireview[J], Analytical Letters (2023) 57(6) 920-939. [CrossRef]

- S. Wu, J.P. Hulme, Recent Advances in the Detection of Antibiotic and Multi-Drug Resistant Salmonella: An Update[J], International Journal of Molecular Sciences (2021) 22(7). [CrossRef]

- S. Wu, N. Duan, et al., Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopic–based aptasensor for Shigella sonnei using a dual-functional metal complex-ligated gold nanoparticles dimer[J], Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces (2020) 190. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, Z. Hu, et al., Non-thermal Microbial Inactivation of Honey Raspberry Wine Through the Application of High-Voltage Electrospray Technology[J], Food and Bioprocess Technology (2022) 15(1) 177-189. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, L. Huang, et al., Magnetic surface-enhanced Raman scattering (MagSERS) biosensors for microbial food safety: Fundamentals and applications[J], Trends in Food Science & Technology (2021) 113 366-381. [CrossRef]

- R. Lu, Z. Liu, et al., Nitric Oxide Enhances Rice Resistance to Rice Black-Streaked Dwarf Virus Infection[J], Rice (2020) 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie, X. Du, et al., Seasonal occurrence and abundance of norovirus in pre- and postharvest lettuce samples in Nanjing, China[J], Lwt (2021) 152. [CrossRef]

- E.Y. Park, S. Maehata, et al., Signal-amplified surface-enhanced Raman scattering using core/shell satellite nanoparticles for norovirus detection[J], Microchimica Acta (2024) 191(9). [CrossRef]

- M. Song, I.M. Khan, et al., Research Progress of Optical Aptasensors Based on AuNPs in Food Safety[J], Food Analytical Methods (2021) 14(10) 2136-2151. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, N.A. Serwah Boateng, et al., Unravelling the fruit microbiome: The key for developing effective biological control strategies for postharvest diseases[J], Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety (2021) 20(5) 4906-4930. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Hassan, X. Yi, et al., Recent advancements of optical, electrochemical, and photoelectrochemical transducer-based microfluidic devices for pesticide and mycotoxins in food and water[J], Trends in Food Science & Technology (2023) 142. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guo, C. Guo, et al., Identification of the apple spoilage causative fungi and prediction of the spoilage degree using electronic nose[J], Journal of Food Process Engineering (2021) 44(10). [CrossRef]

- X. Shi, C. He, et al., Mo-doped Co LDHs as Raman enhanced substrate for detection of roxarsine[J], Analytica Chimica Acta (2024) 1318. [CrossRef]

- M. Liang, G. Zhang, et al., Paper-Based Microfluidic Chips for Food Hazard Factor Detection: Fabrication, Modification, and Application[J], Foods (2023) 12(22). [CrossRef]

- C. Li, M. Song, et al., Selection of aptamer targeting levamisole and development of a colorimetric and SERS dual-mode aptasensor based on AuNPs/Cu-TCPP(Fe) nanosheets[J], Talanta (2023) 251. [CrossRef]

- D. Liang, Y. Xu, et al., Plasmonic metal NP-bismuth composite film with amplified SERS activity for multiple detection of pesticides and veterinary drugs[J], Chemical Engineering Journal (2023) 474. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, M. Mehedi Hassan, et al., Investigation of nonlinear relationship of surface enhanced Raman scattering signal for robust prediction of thiabendazole in apple[J], Food Chemistry (2021) 339. [CrossRef]

- T. Jiao, M. Mehedi Hassan, et al., Quantification of deltamethrin residues in wheat by Ag@ZnO NFs-based surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy coupling chemometric models[J], Food Chemistry (2021) 337. [CrossRef]

- M. Marimuthu, K. Xu, et al., Safeguarding food safety: Nanomaterials-based fluorescent sensors for pesticide tracing[J], Food Chemistry (2025) 463. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, X. Hong, et al., Ultrasensitive monitoring strategy of PCR-like levels for zearalenone contamination based DNA barcode[J], Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture (2021) 101(11) 4490-4497. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, W. Ahmad, et al., Landing microextraction sediment phase onto surface enhanced Raman scattering to enhance sensitivity and selectivity for chromium speciation in food and environmental samples[J], Food Chemistry (2020) 323. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Hassan, W. Ahmad, et al., Rapid detection of mercury in food via rhodamine 6G signal using surface-enhanced Raman scattering coupled multivariate calibration[J], Food Chemistry (2021) 358. [CrossRef]

- W. Lu, X. Dai, et al., Fenton-like catalytic MOFs driving electrochemical aptasensing toward tracking lead pollution in pomegranate fruit[J], Food Control (2025) 169. [CrossRef]

- A.G. Mukherjee, K. Renu, et al., Heavy Metal and Metalloid Contamination in Food and Emerging Technologies for Its Detection[J], Sustainability (2023) 15(2). [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, X. Hu, et al., A simple and sensitive electrochemical sensing based on amine-functionalized metal–organic framework and polypyrrole composite for detection of lead ions in meat samples[J], Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization (2024) 18(7) 5813-5825. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, C. Huang, et al., Allosteric switch for electrochemical aptasensor toward heavy metals pollution of Lentinus edodes sensitized with porphyrinic metal-organic frameworks[J], Analytica Chimica Acta (2023) 1278. [CrossRef]

- A.N. Dominguez, L.E. Jimenez, et al., Rapid detection of pyraclostrobin fungicide residues in lemon with surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy[J], Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization (2023) 17(6) 6350-6362. [CrossRef]

- D. Balram, K.-Y. Lian, et al., Ultrasensitive detection of cytotoxic food preservative tert-butylhydroquinone using 3D cupric oxide nanoflowers embedded functionalized carbon nanotubes[J], Journal of Hazardous Materials (2021) 406. [CrossRef]

- F. Sun, P. Li, et al., Carbon nanomaterials-based smart dual-mode sensors for colorimetric and fluorescence detection of foodborne hazards[J], Trends in Food Science & Technology (2024) 152. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Hassan, Y. Xu, et al., Recent advances of nanomaterial-based optical sensor for the detection of benzimidazole fungicides in food: a review[J], Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition (2021) 63(16) 2851-2872. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, M. Li, et al., Necklace-like Te-Au reticula platform with three dimensional hotspots Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) sensor for food hazards analysis[J], Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy (2024) 311. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, X. Jing, et al., Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering-Active Plasmonic Metal Nanoparticle-Persistent Luminescence Material Composite Films for Multiple Illegal Dye Detection[J], Analytical Chemistry (2021) 93(25) 8945-8953. [CrossRef]

- E.S. Okeke, T.P.C. Ezeorba, et al., Analytical detection methods for azo dyes: A focus on comparative limitations and prospects of bio-sensing and electrochemical nano-detection[J], Journal of Food Composition and Analysis (2022) 114. [CrossRef]

- N. Rong, S. He, et al., Coupled magnetic nanoparticle-mediated isolation and single-cell image recognition to detect Bacillus’ cell size in soil[J], European Journal of Soil Science (2022) 73(3). [CrossRef]

- J. Dai, M. Bai, et al., Advances in the mechanism of different antibacterial strategies based on ultrasound technique for controlling bacterial contamination in food industry[J], Trends in Food Science & Technology (2020) 105 211-222. [CrossRef]

- S. Song, Z. Liu, et al., Detection of fish bones in fillets by Raman hyperspectral imaging technology[J], Journal of Food Engineering (2020) 272. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, N. Zhang, et al., Competitive immunosensor for sensitive and optical anti-interference detection of imidacloprid by surface-enhanced Raman scattering[J], Food Chemistry (2021) 358. [CrossRef]

- D. Thapliyal, M. Karale, et al., Current Status of Sustainable Food Packaging Regulations: Global Perspective[J], Sustainability (2024) 16(13). [CrossRef]

- N.R. Abdul Halim, H. Hashim, et al., Food safety regulations implementation and their impact on food security level in Malaysia: A review[J], International Food Research Journal (2024) 31(1) 20-31. [CrossRef]

- A.-A. Cioca, L. Tušar, et al., Food Risk Analysis: Towards a Better Understanding of “Hazard” and “Risk” in EU Food Legislation[J], Foods (2023) 12(15). [CrossRef]

- F.J. Díaz-Galiano, M. Murcia-Morales, et al., Economic poisons: A review of food contact materials and their analysis using mass spectrometry[J], TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry (2024) 172. [CrossRef]

- Y.-X. Gu, T.-C. Yan, et al., Recent developments and applications in the microextraction and separation technology of harmful substances in a complex matrix[J], Microchemical Journal (2022) 176. [CrossRef]

- E.D. Tsochatzis, J. Alberto Lopes, et al., Development and validation of a multi-analyte GC-MS method for the determination of 84 substances from plastic food contact materials[J], Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2020) 412(22) 5419-5434. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, J. Yang, et al., A facile molecularly imprinted column coupled to GC-MS/MS for sensitive and selective determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and study on their migration in takeaway meal boxes[J], Talanta (2022) 243. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, Q. Chen, et al., Insights into chemometric algorithms for quality attributes and hazards detection in foodstuffs using Raman/surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy[J], Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety (2021) 20(3) 2476-2507. [CrossRef]

- H. Jiang, Y. He, et al., Quantitative Detection of Acid Value During Edible Oil Storage by Raman Spectroscopy: Comparison of the Optimization Effects of BOSS and VCPA Algorithms on the Characteristic Raman Spectra of Edible Oils[J], Food Analytical Methods (2021) 14(9) 1826-1835. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen, Y. Sun, et al., Facile synthesis of Au@Ag core–shell nanorod with bimetallic synergistic effect for SERS detection of thiabendazole in fruit juice[J], Food Chemistry (2022) 370. [CrossRef]

- R. Fakhlaei, A.A. Babadi, et al., Application, challenges and future prospects of recent nondestructive techniques based on the electromagnetic spectrum in food quality and safety[J], Food Chemistry (2024) 441. [CrossRef]

- A. Hassane Hamadou, J. Zhang, et al., Modulating the glycemic response of starch-based foods using organic nanomaterials: strategies and opportunities[J], Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition (2022) 63(33) 11942-11966. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, W. Sheng, et al., Recent advances in rare earth ion-doped upconversion nanomaterials: From design to their applications in food safety analysis[J], Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety (2023) 22(5) 3732-3764. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Z. Wang, et al., H-Bond Modulation Mechanism for Moisture-driven Bacteriostat Evolved from Phytochemical Formulation[J], Advanced Functional Materials (2023) 34(13). [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Z. Wang, et al., Competitive electrochemical sensing for cancer cell evaluation based on thionine-interlinked signal probes[J], The Analyst (2023) 148(4) 912-918. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Y. Zhou, et al., Energy difference-driven ROS reduction for electrochemical tracking crop growth sensitized with electron-migration nanostructures[J], Analytica Chimica Acta (2024) 1304. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, X. Zhang, et al., Multiomics analysis reveals that peach gum colouring reflects plant defense responses against pathogenic fungi[J], Food Chemistry (2022) 383. [CrossRef]

- J. Qiu, H. Gu, et al., A diverse Fusarium community is responsible for contamination of rice with a variety of Fusarium toxins[J], Food Research International (2024) 195. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Hassan, M. Zareef, et al., SERS based sensor for mycotoxins detection: Challenges and improvements[J], Food Chemistry (2021) 344. [CrossRef]

- Z. Chen, R. Tan, et al., SERS detection of triazole pesticide residues on vegetables and fruits using Au decahedral nanoparticles[J], Food Chemistry (2024) 439. [CrossRef]

- Y.-H. Wang, C. Huang, et al., 3D hot spot construction on the hydrophobic interface with SERS tags for quantitative detection of pesticide residues on food surface[J], Food Chemistry (2025) 463. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, X. Huang, et al., Bioinspired nanozyme enabling glucometer readout for portable monitoring of pesticide under resource-scarce environments[J], Chemical Engineering Journal (2022) 429. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Z. Wang, et al., Uniform stain pattern of robust MOF-mediated probe for flexible paper-based colorimetric sensing toward environmental pesticide exposure[J], Chemical Engineering Journal (2023) 451. [CrossRef]

- B. Hu, D.-W. Sun, et al., A dynamically optical and highly stable pNIPAM @ Au NRs nanohybrid substrate for sensitive SERS detection of malachite green in fish fillet[J], Talanta (2020) 218. [CrossRef]

- K. Chao, S. Dhakal, et al., Raman and IR spectroscopic modality for authentication of turmeric powder[J], Food Chemistry (2020) 320. [CrossRef]

- B. Li, S. Liu, et al., Nanohybrid SERS substrates intended for food supply chain safety[J], Coordination Chemistry Reviews (2023) 494. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, X. Huang, et al., Characterization of the volatile flavor profiles of Zhenjiang aromatic vinegar combining a novel nanocomposite colorimetric sensor array with HS-SPME-GC/MS[J], Food Research International (2022) 159. [CrossRef]

- A. Ali, E.E. Nettey-Oppong, et al., Miniaturized Raman Instruments for SERS-Based Point-of-Care Testing on Respiratory Viruses[J], Biosensors (2022) 12(8). [CrossRef]

- R. Beeram, K.R. Vepa, et al., Recent Trends in SERS-Based Plasmonic Sensors for Disease Diagnostics, Biomolecules Detection, and Machine Learning Techniques[J], Biosensors (2023) 13(3). [CrossRef]

- J. Chen, H. Lin, et al., Improving the detection accuracy of the dual SERS aptasensor system with uncontrollable SERS “hot spot” using machine learning tools[J], Analytica Chimica Acta (2024) 1307. [CrossRef]

- M. Usman, J.-W. Tang, et al., Recent advances in surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy for bacterial pathogen identifications[J], Journal of Advanced Research (2023) 51 91-107. [CrossRef]

- L. Lin, X. Bi, et al., Surface-enhanced Raman scattering nanotags for bioimaging[J], Journal of Applied Physics (2021) 129(19). [CrossRef]

- M. Petersen, Z. Yu, et al., Application of Raman Spectroscopic Methods in Food Safety: A Review[J], Biosensors (2021) 11(6). [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, Y. Wang, et al., Surface-enhanced Raman scattering-based strategies for tumor markers detection: A review[J], Talanta (2024) 280. [CrossRef]

- X. Bi, D.M. Czajkowsky, et al., Digital colloid-enhanced Raman spectroscopy by single-molecule counting[J], Nature (2024) 628(8009) 771-775. [CrossRef]

- L. Cai, G. Fang, et al., Label-Free Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopic Analysis of Proteins: Advances and Applications[J], International Journal of Molecular Sciences (2022) 23(22). [CrossRef]

- R. Pilot, R. Signorini, et al., A Review on Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering[J], Biosensors (2019) 9(2). [CrossRef]

- F. Pisano, M. Masmudi-Martín, et al., Vibrational fiber photometry: label-free and reporter-free minimally invasive Raman spectroscopy deep in the mouse brain[J], Nature Methods (2024). [CrossRef]

- Harshita, H.F. Wu, et al., Recent advances in nanomaterials-based optical sensors for detection of various biomarkers (inorganic species, organic and biomolecules)[J], Luminescence (2022) 38(7) 954-998. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, On the Measurements of the Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Spectrum: Effective Enhancement Factor, Optical Configuration, Spectral Distortion, and Baseline Variation[J], Nanomaterials (2023) 13(23). [CrossRef]

- E.C. Le Ru, B. Auguié, Enhancement Factors: A Central Concept during 50 Years of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy[J], ACS Nano (2024) 18(14) 9773-9783. [CrossRef]

- T. Guan, H. Yang, et al., Storage period affecting dynamic succession of microbiota and quality changes of strong-flavor Baijiu Daqu[J], Lwt (2021) 139. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang, A. Wang, et al., Nondestructive measurement of kiwifruit firmness, soluble solid content (SSC), titratable acidity (TA), and sensory quality by vibration spectrum[J], Food Science & Nutrition (2020) 8(2) 1058-1066. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, L. Zhang, et al., Rapid qualitative detection of titanium dioxide adulteration in persimmon icing using portable Raman spectrometer and Machine learning[J], Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy (2023) 290. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu, X. Liang, et al., Non-Destructive Techniques for the Analysis and Evaluation of Meat Quality and Safety: A Review[J], Foods (2022) 11(22). [CrossRef]

- N. Baig, I. Kammakakam, et al., Nanomaterials: a review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges[J], Materials Advances (2021) 2(6) 1821-1871. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Y. Zhou, et al., Simple-easy electrochemical sensing mode assisted with integrative carbon-based gel electrolyte for in-situ monitoring of plant hormone indole acetic acid[J], Food Chemistry (2025) 467. [CrossRef]

- Z.-B. Chen, H.-H. Jin, et al., Recent advances on bioreceptors and metal nanomaterials-based electrochemical impedance spectroscopy biosensors[J], Rare Metals (2022) 42(4) 1098-1117. [CrossRef]

- M. Shoaib, H. Li, et al., Emerging MXenes-based aptasensors: A paradigm shift in food safety detection[J], Trends in Food Science & Technology (2024) 151. [CrossRef]

- M.W. Iqbal, T. Riaz, et al., Fucoidan-based nanomaterial and its multifunctional role for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications[J], Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition (2022) 64(2) 354-380. [CrossRef]

- S.S. Ali, M.S. Moawad, et al., Efficacy of metal oxide nanoparticles as novel antimicrobial agents against multi-drug and multi-virulent Staphylococcus aureus isolates from retail raw chicken meat and giblets[J], International Journal of Food Microbiology (2021) 344. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tian, D. Xu, et al., Highly ordered nanocavity as photonic-plasmonic-polaritonic resonator for single molecule miRNA SERS detection[J], Biosensors and Bioelectronics (2024) 254. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tian, Z. Zhang, Photonic–plasmonic resonator for SERS biodetection[J], The Analyst (2024) 149(11) 3123-3130. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ying, Z. Tang, et al., Material design, development, and trend for surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrates[J], Nanoscale (2023) 15(26) 10860-10881. [CrossRef]

- K. Chang, Y. Zhao, et al., Advances in metal-organic framework-plasmonic metal composites based SERS platforms: Engineering strategies in chemical sensing, practical applications and future perspectives in food safety[J], Chemical Engineering Journal (2023) 459. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guo, Y. Zheng, et al., Flexible Au@AgNRs/MAA/PDMS-based SERS sensor coupled with intelligent algorithms for in-situ detection of thiram on apple[J], Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical (2024) 404. [CrossRef]

- B. Hu, D.-W. Sun, et al., Rapid nondestructive detection of mixed pesticides residues on fruit surface using SERS combined with self-modeling mixture analysis method[J], Talanta (2020) 217. [CrossRef]

- K. Wang, D.-W. Sun, et al., Two-dimensional Au@Ag nanodot array for sensing dual-fungicides in fruit juices with surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy technique[J], Food Chemistry (2020) 310. [CrossRef]

- L. Ma, Q. Xu, et al., Surface-enhanced Raman scattering sensor based on cysteine-mediated nucleophilic addition reaction for detection of patulin[J], Microchemical Journal (2024) 204. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, N. Zhou, et al., A dual-signaling surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy ratiometric strategy for ultrasensitive Hg2+ detection based on Au@Ag/COF composites[J], Food Chemistry (2024) 456. [CrossRef]

- Q. Ding, J. Wang, et al., Quantitative and Sensitive SERS Platform with Analyte Enrichment and Filtration Function[J], Nano Letters (2020) 20(10) 7304-7312. [CrossRef]

- X. Gao, Y. Liu, et al., A facile dual-mode SERS/fluorescence aptasensor for AFB1 detection based on gold nanoparticles and magnetic nanoparticles[J], Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy (2024) 315. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen, X. Cao, et al., Functionalized MXene (Ti3C2TX) Loaded with Ag Nanoparticles as a Raman Scattering Substrate for Rapid Furfural Detection in Baijiu[J], Foods (2024) 13(19). [CrossRef]

- Z. Wu, D.-W. Sun, et al., Ti3C2Tx MXenes loaded with Au nanoparticle dimers as a surface-enhanced Raman scattering aptasensor for AFB1 detection[J], Food Chemistry (2022) 372. [CrossRef]

- X. Hu, B. Yang, et al., One-Pot Synthesis of a Three-Dimensional Au-Decorated Cellulose Nanocomposite as a Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Sensor for Selective Detection and in Situ Monitoring[J], ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering (2021) 9(8) 3324-3336. [CrossRef]

- P. Hu, X. Zhang, et al., A SERS-based point-of-care testing approach for efficient determination of diquat and paraquat residues using a flexible silver flower-coated melamine sponge[J], Food Chemistry (2024) 454. [CrossRef]

- L. Liu, Y. Wang, et al., Research progress of dual-mode sensing technology strategy based on SERS and its application in the detection of harmful substances in foods[J], Trends in Food Science & Technology (2024) 148. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, L. Shi, et al., SERS-Active Composites with Au–Ag Janus Nanoparticles/Perovskite in Immunoassays for Staphylococcus aureus Enterotoxins[J], ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces (2022) 14(2) 3293-3301. [CrossRef]

- X. Tang, Q. Hao, et al., Exploring and Engineering 2D Transition Metal Dichalcogenides toward Ultimate SERS Performance[J], Advanced Materials (2024) 36(19). [CrossRef]

- H. Ma, S.-Q. Pan, et al., Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy: Current Understanding, Challenges, and Opportunities[J], ACS Nano (2024) 18(22) 14000-14019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hang, A. Wang, et al., Plasmonic silver and gold nanoparticles: shape- and structure-modulated plasmonic functionality for point-of-caring sensing, bio-imaging and medical therapy[J], Chemical Society Reviews (2024) 53(6) 2932-2971. [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, X. Zheng, et al., Research advances of SERS analysis method based on silent region molecules for food safety detection[J], Microchimica Acta (2023) 190(10). [CrossRef]

- M. Chen, J. Zhang, et al., Hybridizing Silver Nanoparticles in Hydrogel for High-Performance Flexible SERS Chips[J], ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces (2022) 14(22) 26216-26224. [CrossRef]

- H. Dong, W. Bai, et al., Fabrication of Raman reporter molecule–embedded magnetic SERS tag for ultrasensitive immunochromatographic monitoring of Cd ions and clenbuterol in complex samples[J], Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects (2024) 702. [CrossRef]

- L. Jiang, W. Wei, et al., A tailorable and recyclable TiO2 NFSF/Ti@Ag NPs SERS substrate fabricated by a facile method and its applications in prohibited fish drugs detection[J], Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization (2022) 16(4) 2890-2898. [CrossRef]

- R. Liu, J. Wang, et al., Reusable Ag SERS substrates fabricated by tip-based mechanical lithography[J], Optical Materials (2024) 156. [CrossRef]

- J. Peng, P. Liu, et al., Templated synthesis of patterned gold nanoparticle assemblies for highly sensitive and reliable SERS substrates[J], Nano Research (2022) 16(4) 5056-5064. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, S. Yang, Highly sensitive, reproducible, and stable core–shell MoN SERS substrate synthesized via sacrificial template method[J], Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy (2025) 327. [CrossRef]

- M.-C. Yang, T.-Y. Chien, et al., Reproducible SERS substrates manipulated by interparticle spacing and particle diameter of gold nano-island array using in-situ thermal evaporation[J], Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy (2023) 303. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhou, A. Xie, et al., Vacuum-assisted thermal evaporation deposition for the preparation of AgNPs/NF 3D SERS substrates and their applications[J], New Journal of Chemistry (2023) 47(46) 21225-21231. [CrossRef]

- N. Zhang, L. Cui, et al., Fabrication of blue silver substrate with 10 nm grains by an electrochemical deposition and application in SERS[J], Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry (2023) 946. [CrossRef]

- R. Peng, T. Zhang, et al., Self-Assembly of Strain-Adaptable Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Substrate on Polydimethylsiloxane Nanowrinkles[J], Analytical Chemistry (2024) 96(26) 10620-10629. [CrossRef]

- H. Yang, H. Mo, et al., Observation of single-molecule Raman spectroscopy enabled by synergic electromagnetic and chemical enhancement[J], PhotoniX (2024) 5(1). [CrossRef]

- B. Yang, G. Chen, et al., Chemical Enhancement and Quenching in Single-Molecule Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy[J], Angewandte Chemie International Edition (2023) 62(13). [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, Y. Tang, et al., A new semiconductor heterojunction SERS substrate for ultra-sensitive detection of antibiotic residues in egg[J], Food Chemistry (2024) 431. [CrossRef]

- B. Yin, W.K.H. Ho, et al., Magnetic-Responsive Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Platform with Tunable Hot Spot for Ultrasensitive Virus Nucleic Acid Detection[J], ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces (2022) 14(3) 4714-4724. [CrossRef]

- K. Yang, K. Zhu, et al., Ti3C2Tx MXene-Loaded 3D Substrate toward On-Chip Multi-Gas Sensing with Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) Barcode Readout[J], ACS Nano (2021) 15(8) 12996-13006. [CrossRef]

- Q. Hao, Y. Chen, et al., Mechanism Switch in Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering: The Role of Nanoparticle Dimensions[J], The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters (2024) 15(28) 7183-7190. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, X. Huang, et al., Applications of surface functionalized Fe3O4 NPs-based detection methods in food safety[J], Food Chemistry (2021) 342. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, L. Shi, et al., “Add on” Dual-Modal Optical Immunoassay by Plasmonic Metal NP-Semiconductor Composites[J], Analytical Chemistry (2021) 93(6) 3250-3257. [CrossRef]

- J. Yao, Z. Jin, et al., Electroactive and SERS-Active Ag@Cu2O NP-Programed Aptasensor for Dual-Mode Detection of Tetrodotoxin[J], ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces (2023) 15(7) 10240-10249. [CrossRef]

- H. He, D.-W. Sun, et al., A SERS-Fluorescence dual-signal aptasensor for sensitive and robust determination of AFB1 in nut samples based on Apt-Cy5 and MNP@Ag-PEI[J], Talanta (2023) 253. [CrossRef]

- S. Tang, B. He, et al., A dual-signal mode electrochemical aptasensor based on tetrahedral DNA nanostructures for sensitive detection of citrinin in food using PtPdCo mesoporous nanozymes[J], Food Chemistry (2024) 460. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, S. Lu, et al., Hydrogel/MOF Dual-Modified Photoelectrochemical Biosensor for Antibiofouling and Biocompatible Dopamine Detection[J], Langmuir (2024) 40(20) 10718-10725. [CrossRef]

- H. Yan, B. He, et al., Electrochemical aptasensor based on CRISPR/Cas12a-mediated and DNAzyme-assisted cascade dual-enzyme transformation strategy for zearalenone detection[J], Chemical Engineering Journal (2024) 493. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, X. Zhou, et al., The Effects of Carbendazim on Acute Toxicity, Development, and Reproduction in Caenorhabditis elegans[J], Journal of Food Quality (2020) 2020 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, C. Zhao, et al., Ultrasensitive Analysis of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Based on Immunomagnetic Separation and Labeled Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering with Minimized False Positive Identifications[J], Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry (2024) 72(40) 22349-22359. [CrossRef]

- Y. Suzuki, H. Shimizu, et al., Simultaneous detection of various pathogenic Escherichia coli in water by sequencing multiplex PCR amplicons[J], Environmental Monitoring and Assessment (2023) 195(2). [CrossRef]

- M. Gao, F. Tan, et al., Rapid detection method of bacterial pathogens in surface waters and a new risk indicator for water pathogenic pollution[J], Scientific Reports (2024) 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Z. Wu, Y. Chen, et al., Endoprotein-activating DNAzyme assay for nucleic acid extraction- and amplification-free detection of viable pathogenic bacteria[J], Biosensors and Bioelectronics (2024) 266. [CrossRef]

- R. Deng, J. Bai, et al., Nanotechnology-leveraged nucleic acid amplification for foodborne pathogen detection[J], Coordination Chemistry Reviews (2024) 506. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhao, S. Yang, et al., Ultrasensitive dual-enhanced sandwich strategy for simultaneous detection of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus based on optimized aptamers-functionalized magnetic capture probes and graphene oxide-Au nanostars SERS tags[J], Journal of Colloid and Interface Science (2023) 634 651-663. [CrossRef]

- L. Huang, D.-W. Sun, et al., Reproducible, shelf-stable, and bioaffinity SERS nanotags inspired by multivariate polyphenolic chemistry for bacterial identification[J], Analytica Chimica Acta (2021) 1167. [CrossRef]

- J. Olvera-Aripez, S. Camacho-López, et al., Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by fungi and its potential in SERS[J], Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering (2024) 47(9) 1585-1593. [CrossRef]

- J. Wei, Y. He, et al., Satellite nanostructures composed of CdTe quantum dots and DTNB-labeled AuNPs used for SERS-fluorescence dual-signal detection of AFB1[J], Food Control (2024) 156. [CrossRef]

- G. Xie, L. Liu, et al., Development of tri-mode lateral flow immunoassay based on tailored porous gold nanoflower for sensitive detection of aflatoxin B1[J], Food Bioscience (2024) 61. [CrossRef]

- R. Peng, W. Qi, et al., Development of surface-enhanced Raman scattering-sensing Method by combining novel Ag@Au core/shell nanoparticle-based SERS probe with hybridization chain reaction for high-sensitive detection of hepatitis C virus nucleic acid[J], Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2024) 416(10) 2515-2525. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, X. Chen, et al., Low-Temperature Substrate: Detection of Viruses on Cold Chain Food Packaging Based on Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy[J], ACS Materials Letters (2024) 6(10) 4649-4657. [CrossRef]

- T. Chen, W. Liang, et al., Screening and identification of unknown chemical contaminants in food based on liquid chromatography–high-resolution mass spectrometry and machine learning[J], Analytica Chimica Acta (2024) 1287. [CrossRef]

- Q. Sun, Y. Dong, et al., A review on recent advances in mass spectrometry analysis of harmful contaminants in food[J], Frontiers in Nutrition (2023) 10. [CrossRef]

- X. Su, Z. Chen, et al., Ratiometric immunosensor with DNA tetrahedron nanostructure as high-performance carrier of reference signal and its applications in selective phoxim determination for vegetables[J], Food Chemistry (2022) 383. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ding, Y. Sun, et al., SERS-Based Biosensors Combined with Machine Learning for Medical Application**[J], ChemistryOpen (2023) 12(1). [CrossRef]

- Y. Dong, J. Hu, et al., Advances in machine learning-assisted SERS sensing towards food safety and biomedical analysis[J], TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry (2024) 180. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, M. Zou, et al., Ultrasensitive and selective detection of sulfamethazine in milk via a Janus-labeled Au nanoparticle-based surface-enhanced Raman scattering-immunochromatographic assay[J], Talanta (2024) 267. [CrossRef]

- X. He, S. Yang, et al., Microdroplet-captured tapes for rapid sampling and SERS detection of food contaminants[J], Biosensors and Bioelectronics (2020) 152. [CrossRef]

- W. Hu, L. Xia, et al., Fe3O4-WO3−X@AuNPs for magnetic separation, enrichment and surface-enhanced Raman scattering analysis all-in-one of albendazole and streptomycin in meat samples[J], Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical (2024) 402. [CrossRef]

- J. Tu, T. Wu, et al., Introduction of multilayered magnetic core–dual shell SERS tags into lateral flow immunoassay: A highly stable and sensitive method for the simultaneous detection of multiple veterinary drugs in complex samples[J], Journal of Hazardous Materials (2023) 448. [CrossRef]

- L. Jiang, M.M. Hassan, et al., Evolving trends in SERS-based techniques for food quality and safety: A review[J], Trends in Food Science & Technology (2021) 112 225-240. [CrossRef]

- P. Yue, M. Zhang, et al., Eco-friendly epoxidized Eucommia ulmoides gum based composite coating with enhanced super-hydrophobicity and corrosion resistance properties[J], Industrial Crops and Products (2024) 214. [CrossRef]

- X. Xia, C. Zhou, et al., Tb3+-nucleic acid probe-based label-free and rapid detection of mercury pollution in food[J], Food Science and Human Wellness (2024) 13(2) 993-998. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, H. Liu, et al., Ultrasensitive label-free electrochemical aptasensor for Pb2+ detection exploiting Exo III amplification and AgPt/GO nanocomposite-enhanced transduction[J], Talanta (2024) 276. [CrossRef]

- Q. Chen, J. Tang, et al., SERS scaffold based on silver nanoparticles with multi-ingredient heavy metal ligands for the determination of Mn(II)[J], Colloid and Polymer Science (2023) 301(8) 949-956. [CrossRef]

- P. Chen, L. Yin, et al., Green reduction of silver nanoparticles for cadmium detection in food using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy coupled multivariate calibration[J], Food Chemistry (2022) 394. [CrossRef]

- M. Shaban, In-Situ SERS Detection of Hg2+/Cd2+ and Congo Red Adsorption Using Spiral CNTs/Brass Nails[J], Nanomaterials (2022) 12(21). [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun, H. Tang, et al., Raman spectroscopy for food quality assurance and safety monitoring: a review[J], Current Opinion in Food Science (2022) 47. [CrossRef]

- K. Ramachandran, A. Hamdi, et al., Synergism induced sensitive SERS sensing to detect 2,6-Di-t-butyl-p-hydroxytoluene (BHT) with silver nanotriangles sensitized ZnO nanorod arrays for food security applications[J], Surfaces and Interfaces (2022) 35. [CrossRef]

- Z. Lu, W. Wei, et al., Improved SERS performance of a silver triangular nanoparticle/TiO2 nanoarray heterostructure and its application for food additive detection[J], New Journal of Chemistry (2022) 46(15) 7070-7077. [CrossRef]

- L. Xu, H. Liu, et al., Fabrication of SERS substrates by femtosecond LIPAA for detection of contaminants in foods[J], Optics & Laser Technology (2022) 151. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, C. Wang, et al., Preparation of SERS substrate with 2D silver plate and nano silver sol for plasticizer detection in edible oil[J], Food Chemistry (2023) 409. [CrossRef]

- B.S. Michaels, T. Ayers, et al., Potential for Glove Risk Amplification via Direct Physical, Chemical, and Microbiological Contamination[J], Journal of Food Protection (2024) 87(7). [CrossRef]

- M. Pakdel, A. Olsen, et al., A Review of Food Contaminants and Their Pathways Within Food Processing Facilities Using Open Food Processing Equipment[J], Journal of Food Protection (2023) 86(12). [CrossRef]

- A. Thakali, J.D. MacRae, et al., Composition and contamination of source separated food waste from different sources and regulatory environments[J], Journal of Environmental Management (2022) 314. [CrossRef]

| Classification | Specific Materials | Characteristics |

Metal Nanostructures[7,120]

|

Au, Ag, Metal Alloy | Widely used in SERS substrates due to their excellent LSPR property. |

Core-Shell Structure [13,121,122]

|

Au@Ag, Ag@Au | Optimizing SERS signals by adjusting the properties of the outer layer metal. |

Porous Materials[39,123,124]

|

Porous carbon (PC), Porous silicon (PS), Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) | High specific surface area and good molecular sieving effects, effectively adsorbing target molecules and enhancing SERS signals. |

Semiconductor Nanostructures[13,125]

|

Titanium dioxide (TiO2), Zinc oxide (ZnO) | Weak in SERS activity on their own, but can enhance signal strength when combined with metal nanoparticles. |

Carbon-Based Nanostructures[126,127]

|

Graphene and its derivatives (e.g., reduced graphene oxide) | Excellent conductivity and large specific surface area, effectively enhancing SERS signals. |

Polymer-Based Nanostructures[128]

|

Functionalized polymers (e.g., PMMA, PDMS) | Combining with metal nanoparticles to form composition for enhancing SERS signals. |

Biomass-Based Nanostructures[129]

|

Natural polymers (e.g., chitosan, gelatin) | Biocompatibility and tunability allow them to combine with metal nanoparticles for enhancing signals. |

Composite Nanostructures[13,123,124,130,131]

|

Combination of different nanostructures (e.g., metals with semiconductors, metals with porous materials) | Achieving synergistic effects to further enhance SERS signals. |

| Advantage | Description | Advantage | Description |

| High Sensitivity Detection |

SERS technology uses the surface plasmon resonance of metal nanoparticles to significantly enhance the Raman signals of adsorbed molecules, enabling highly sensitive detection of trace hazardous substances in food. |

Real-Time Monitoring Capability | Combined with portable devices, SERS technology can achieve real-time monitoring of hazardous substances during food processing and storage. |

| Rapid Response | SERS technology can provide rapid assay results, which is crucial for immediate response and management of food safety incidents. | Data Traceability | The Raman spectra provided by SERS have unique fingerprint characteristics, aiding in tracing contamination sources and food safety traceability. |

| No Need for Labeling andPretreatment | SERS detection does not require complex sample pre-treatment or labeling; it can directly test food samples, simplifying operational process. | Strong Environmental Adaptability | Nanostructures can be used under various environmental conditions, enhancing the application potential of SERS technology in diverse food testing scenarios. |

| High Selectivity | SERS technology exhibits high selectivity, enabling the rapid quantitative or qualitative detection of hazardous substances in complex food matrices. | Cost-Effectiveness | Although the initial investment may be high, SERS technology reduces the costs associated with repeated testing and erroneous results, making it cost-effective in the long run. |

| Multiplex Detection Capability |

SERS technology is capable of detecting multiple hazardous substances simultaneously, enhancing the efficiency and scope of detection. |

Biocompatibility | Selecting appropriate nanostructures ensures that SERS detection is safe for both food and operators, avoiding secondary contamination. |

| Classification | Sources | |

| Foreign matter contamination |  |

Metal fragments, glass fragments, plastic fragments, stones, sand particles, and more. May originate from wear of processing equipment or packaging materials, environmental pollution during raw material collection or processing. |

| Radioactive contamination |  |

Contamination caused by radioactive substances, which may enter the food chain through soil and water sources. |

| Noise pollution |  |

Long-term exposure to noise may impact the work efficiency and psychological health of food processing personnel, indirectly affecting food quality. |

| Light pollution |  |

Excessive lighting may affect food storage conditions, leading to spoilage or a decrease in nutritional value. |

| Thermal pollution |  |

Inappropriate temperatures may cause food spoilage during storage and transportation. |

| Mechanical impurities |  |

Lubricating oils, metal shavings, and other substances from mechanical equipment may be mixed into food. |

| Packaging material contamination |  |

Certain chemicals from packaging materials may migrate into food, causing physical contamination. |

| Natural impurities |  |

Naturally occurring impurities in food raw materials, such as small stones in grains, small insects in fruits and vegetables, etc. |

| Human negligence |  |

During food processing, tools, equipment parts, and other foreign objects may be inadvertently mixed into food due to human error. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).