Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

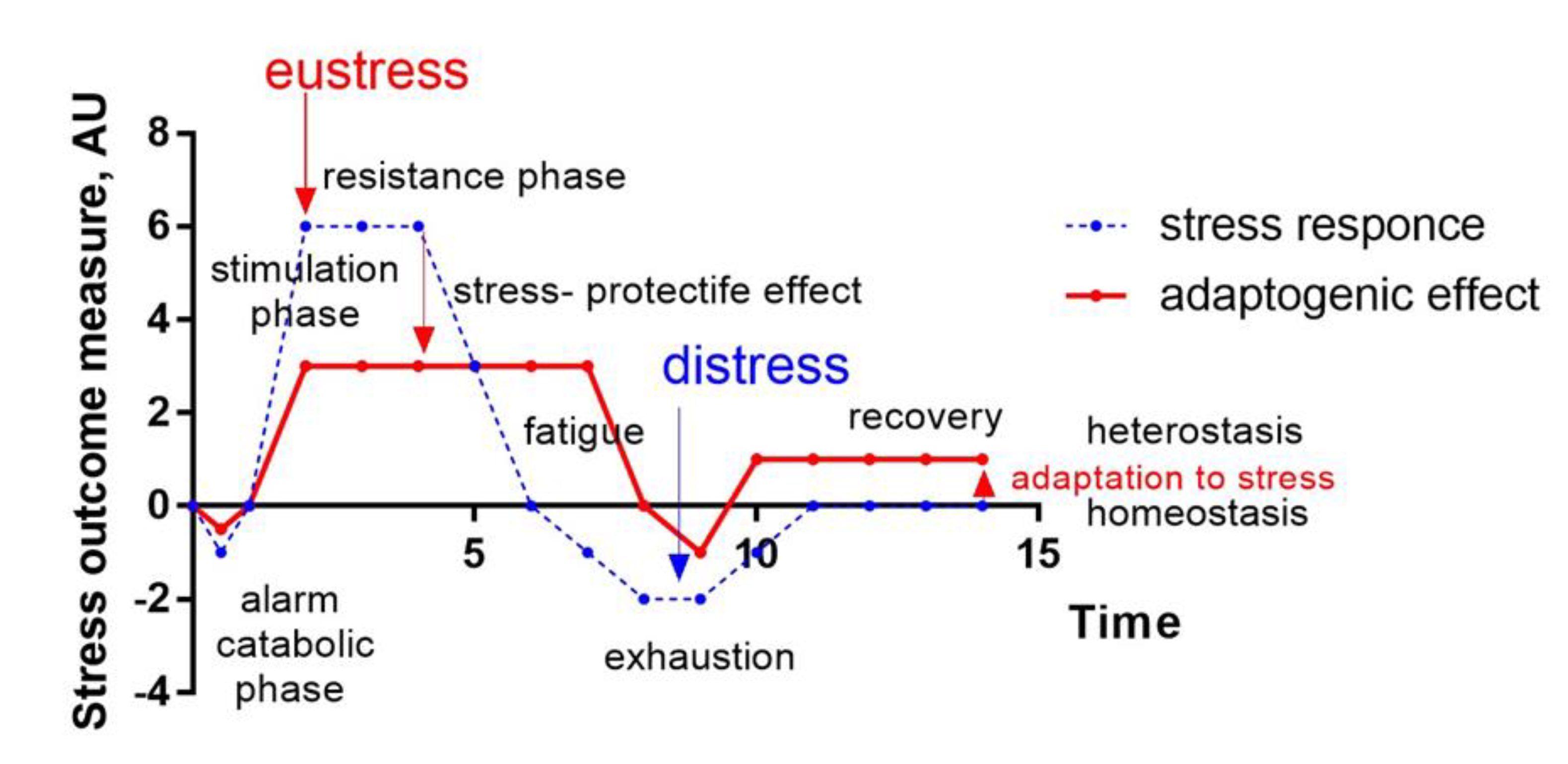

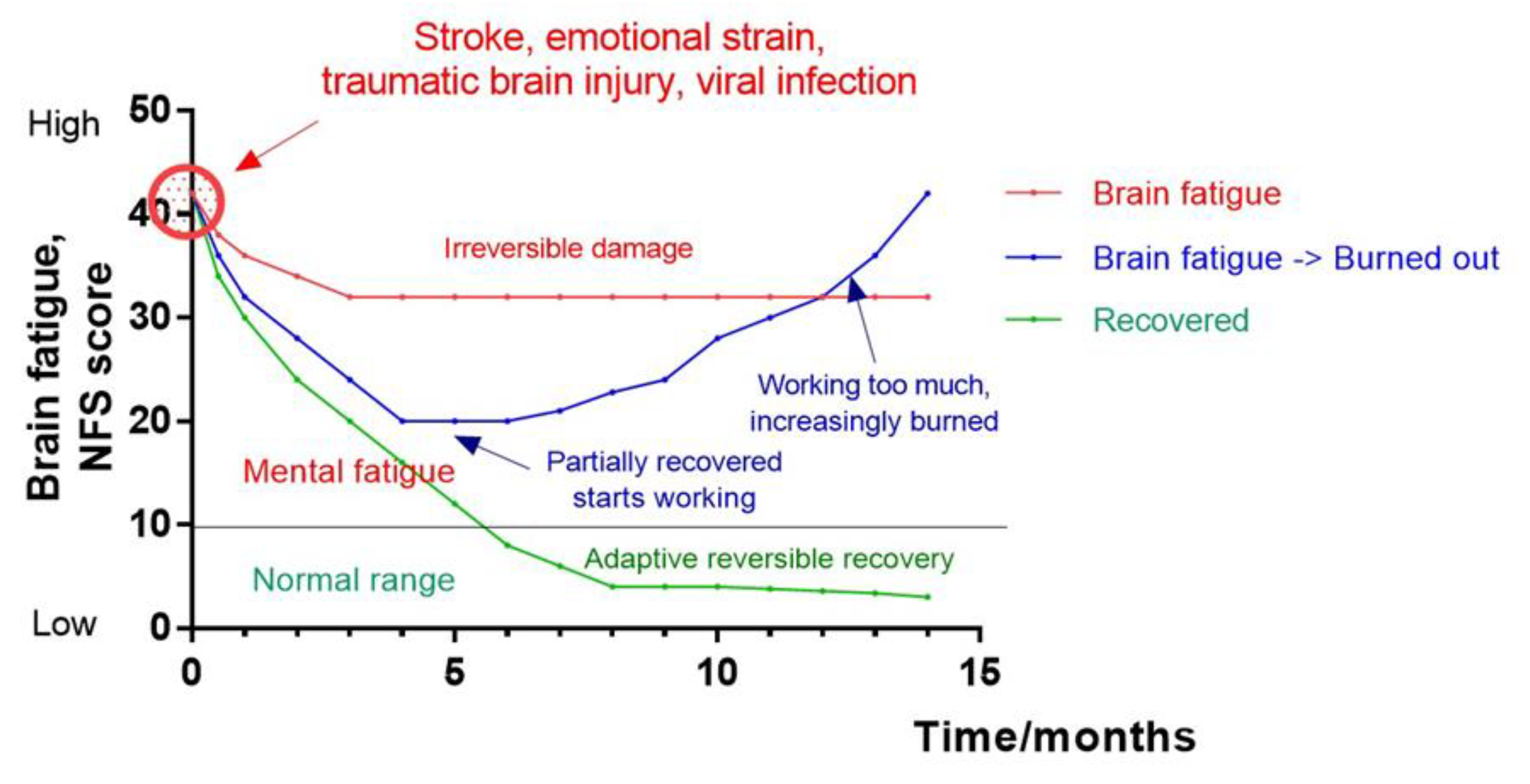

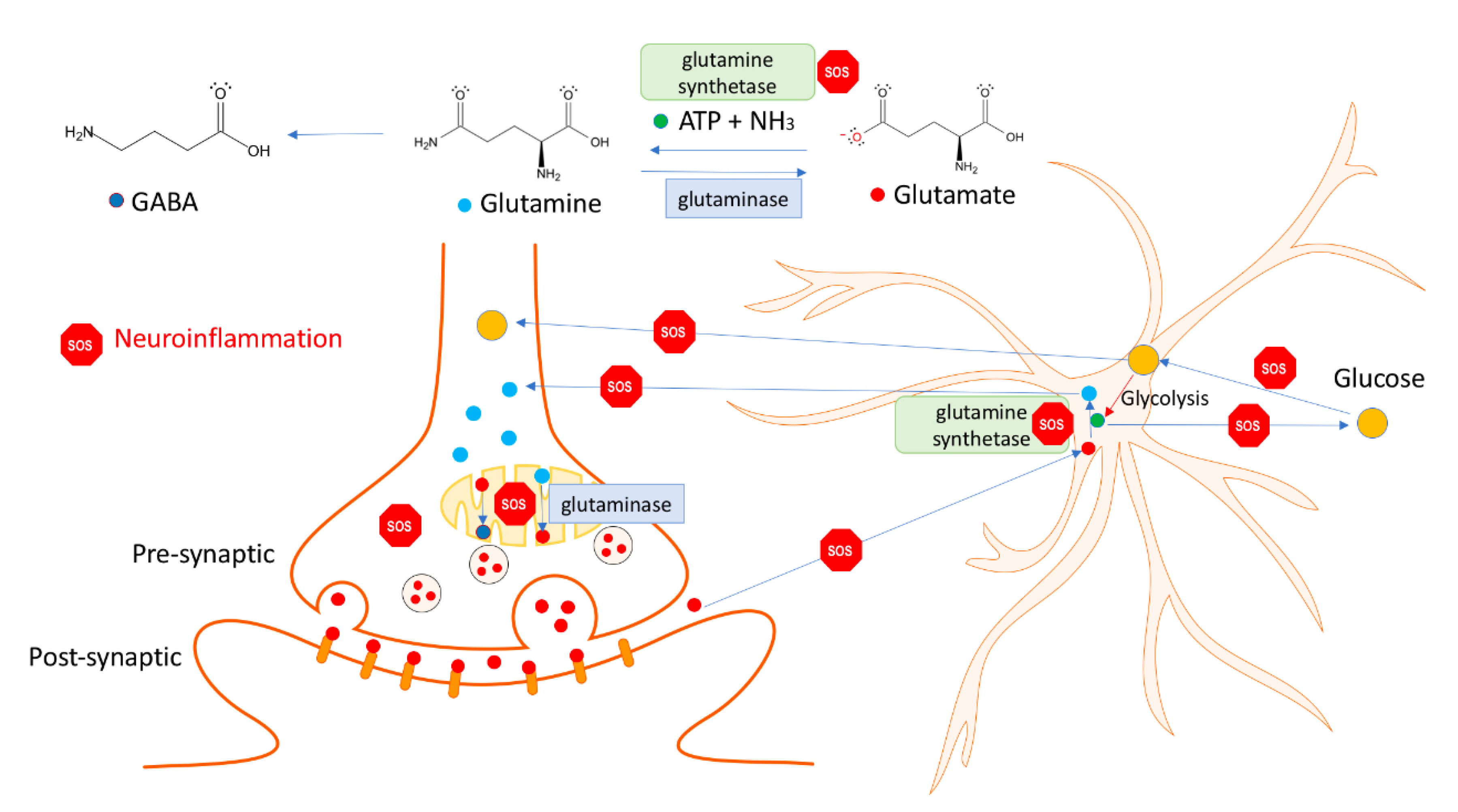

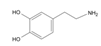

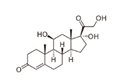

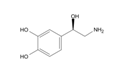

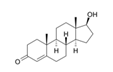

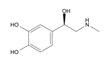

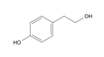

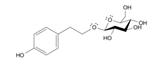

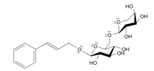

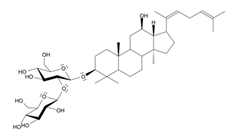

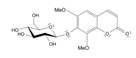

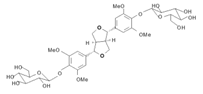

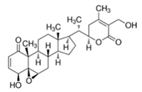

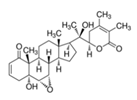

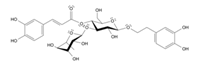

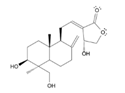

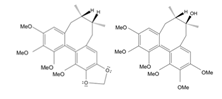

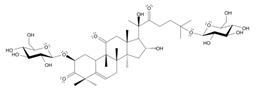

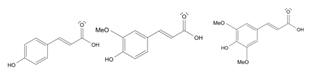

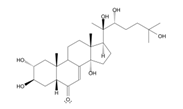

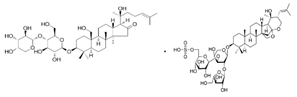

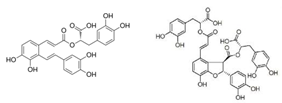

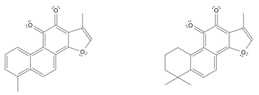

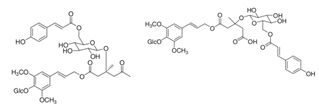

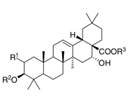

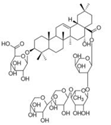

Long-lasting brain fatigue is a consequence of stroke or traumatic brain injury associated with emotional, psychological, and physical overload, distress in hypertension, atherosclerosis, viral infection, and aging-related chronic low-grade inflammatory disorders. The pathogenesis of brain fatigue is linked to disrupted neurotransmission, the glutamate-glutamine cycle imbalance, glucose metabolism, and ATP energy supply, which are associated with multiple molecular targets and signaling pathways in neuroendocrine-immune and blood circulation systems. Regeneration of damaged brain tissue is a long-lasting multistage process, including spontaneously regulating hypothalamus-pituitary (HPA) axis-controlled anabolic–catabolic homeostasis to recover harmonized sympathoadrenal system (SAS)-mediated function, brain energy supply, and deregulated gene expression in rehabilitation. The driving mechanism of spontaneous recovery and regeneration of brain tissue is a cross-talk of mediators of neuronal, microglia, immunocompetent, and endothelial cells collectively involved in neurogenesis and angiogenesis, which plant adaptogens can target. Adaptogens are small molecules of plant origin that increase the adaptability of cells and organisms to stress by interaction with the HPA-axis and SAS of the stress system (neuroendocrine immune and cardiovascular complex), targeting multiple mediators of adaptive GPCR signaling pathways. Two major groups of adaptogens comprise (i) phenolic phenethyl and phenylpropanoid derivatives and (ii) tetracyclic and pentacyclic glycosides, whose chemical structure can be distinguished as related correspondingly to (i) -monoamine neurotransmitters of SAS (epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine), and (ii) - steroid hormones (cortisol, testosterone, and estradiol). In this narrative review, we discuss (i) the multitarget mechanism of integrated pharmacological activity of botanical adaptogens in stress overload, ischemic stroke, and long-lasting brain fatigue, (ii) - time-dependent dual response of physiological regulatory systems to adaptogens to support homeostasis in chronic stress and overload, and (iii) - dual dose depending reversal (hormetic) effect of botanical adaptogens. This narrative review shows that the adaptogenic concept cannot be reduced and rectified to the various effects of adaptogens on selected molecular targets or specific modes of action without estimating their interactions within the networks of mediators of the neuroendocrine-immune complex that, in turn, regulates other pharmacological systems (cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, reproductive systems) due to numerous intra- and extracellular communications and feedback regulations. These interactions result in polyvalent action and the pleiotropic pharmacological activity of adaptogens, essential for characterizing adaptogens as distinct types of botanicals. They trigger the defense adaptive stress response that leads to the extension of the limits of resilience to overload, inducing brain fatigue and mental disorders. For the first time, this review justifies the neurogenesis potential of adaptogens, particularly botanical hybrid preparation (BHP) of Arctic Root and Ashwagandha, providing a rationale for potential use in individuals experiencing long-lasting brain fatigue. The review provided insight into future research on network pharmacology of adaptogens in preventing and rehabilitating long-lasting brain fatigue following stroke, trauma, and viral infections.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Stress, Mental Fatigue, and the Effect of Adaptogens

3. Brain Fatigue

3.1. Symptoms and Methods of Assessment of Brain/Mental Fatigue and Brain Energy

3.2. Treatment of Long-Lasting Brain Fatigue in Rehabilitation of Stroke and Post-Traumatic Brain Injury

3.3. Pathophysiology and Biochemistry of Brain Fatigue and Brain Energy

3.3.1. Glutamate Neurotransmission Imbalance, Glucose Depletion, and Energy Shortage Hypothesis

3.3.2. Brain Energy Resources and Utilization in Brain Fatigue

3.3.3. Brain energy supply and metabolism in stress, stroke, obesity, diabetes, and aging disorders

4. Overview of Stress-Protective and Anti-Fatigue Effects of Adaptogens

4.1. Adaptogens and Adaptive Stress Response

4.2. Multitarget and Pleiotropic Effects of Adaptogens

4.2.1. Effects of Adaptogens on Neuroinflammation Signaling Pathways

4.2.2. The dose Matters: Hormetic Dose-Dependent Reversal Effects of Adaptogens

4.3. Antifatigue of Adaptogens

5. Neuroprotective Activity of Adaptogens for Promoting Adult Neurogenesis in Aging Neurodegeneration, Post-Stroke, Traumatic Brain Injury, and Brain Fatigue

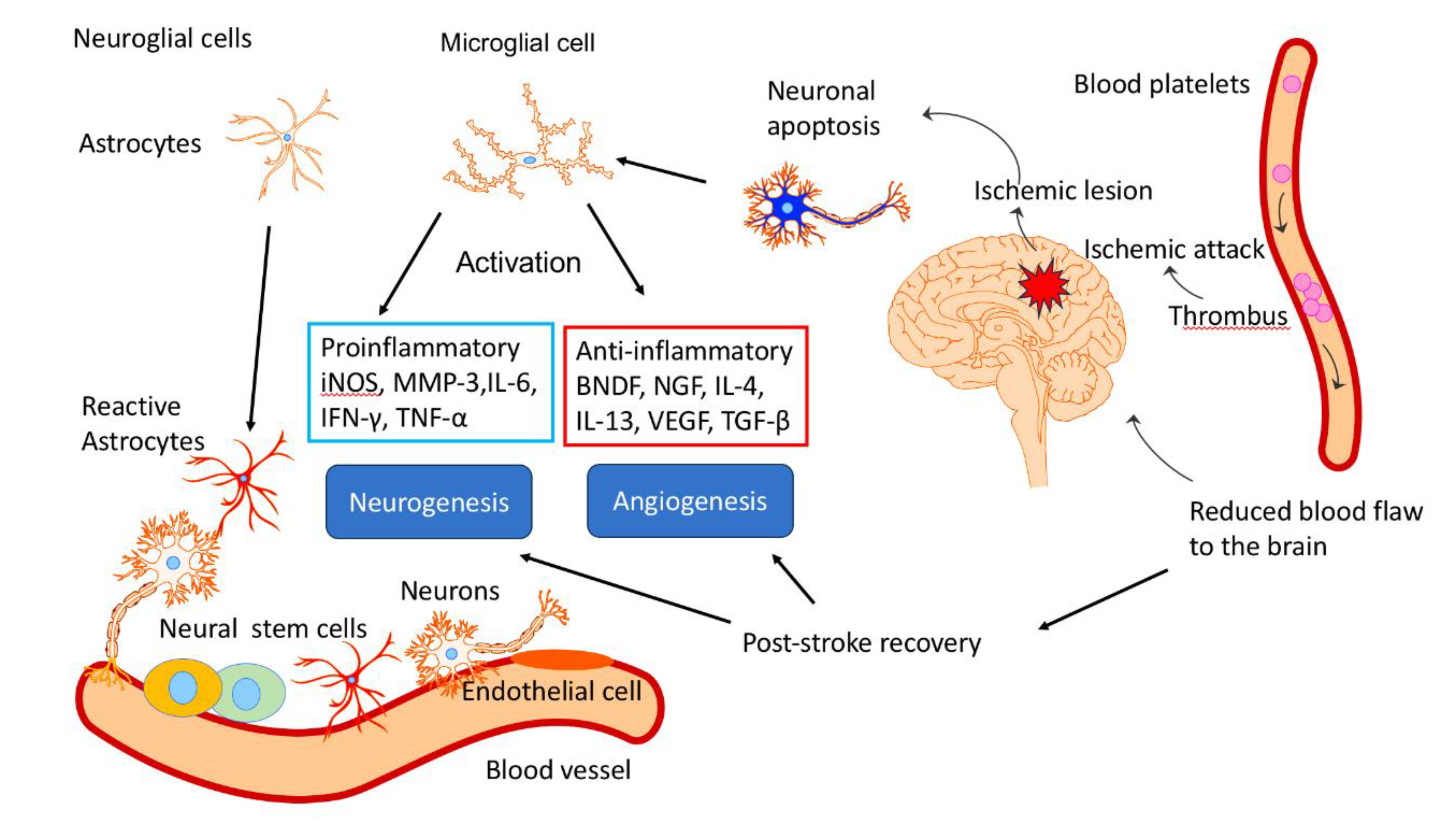

5.1. Essential Role of Neurogenesis in Post-Stroke Recovery for Brain Fatigue

5.2. Botanicals for Promoting Neurogenesis and Angiogenesis and Recovery of Ischemic Stroke

5.2.1. Adaptogenic Botanicals Used in TCM for the Treatment of Stroke

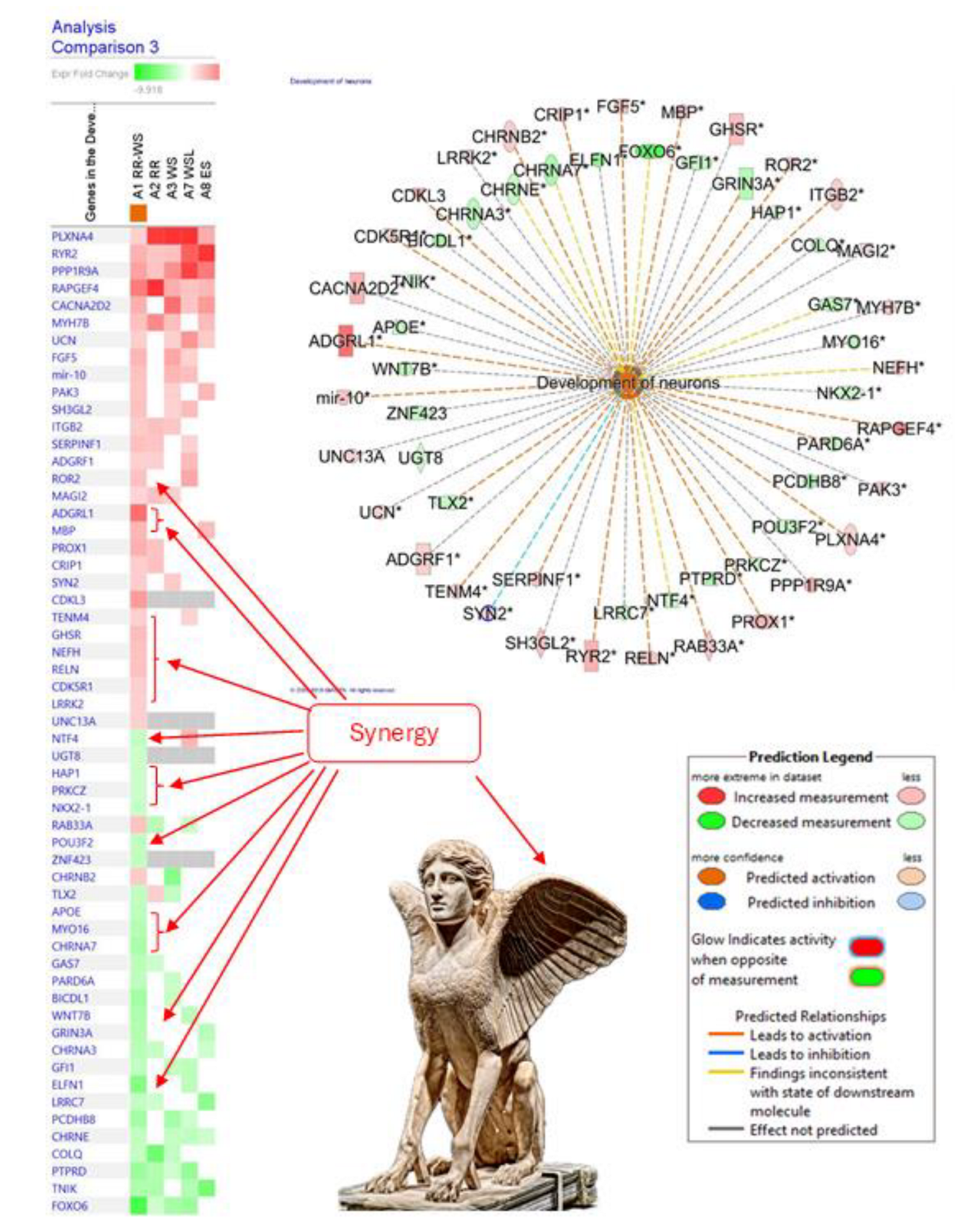

5.2.2. Rhodiola and Withania for Neuroprotection in Stroke and Their Synergistic Effect on Neurogenesis

6. Discussion

6.1. The Review’s Highlights

6.2. Future Perspectives in the Treatment of Brain Fatigue

6.3. Where do We Go in Drug Discovery?

6.4. Critical appraisal, Limitations, and Challenges in Network Pharmacology Studies

7. Conclusions

Funding

Author contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Gaillard A., W. (1993). Comparing the concepts of mental load and stress. Ergonomics, 36(9), 991–1005. [CrossRef]

- Kunasegaran, K. , Ismail, A. M. H., Ramasamy, S., Gnanou, J. V., Caszo, B. A., & Chen, P. L. (2023). Understanding mental fatigue and its detection: a comparative analysis of assessments and tools. PeerJ, 11, e15744. [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, I. e: Business-Economy Published on 28/09/2024 - 7:10 GMT+2•Updated 16:14, 2024.

- Chaudhuri, A. , & Behan, P. O. ( 363(9413), 978–988. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. , Andréll, P., Mannheimer, C., Rönnbäck, L. (2022). Hjärntrötthet – ett osynligt gissel. Brain fatigue – an invisible scourge, [Mental fatigue - possible explanations, diagnostic methods and possible treatments]. Lakartidningen, 119, 21073. https://lakartidningen. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rönnbäck, L. , & Johansson, B. (2022). Long-Lasting Pathological Mental Fatigue After Brain Injury-A Dysfunction in Glutamate Neurotransmission? Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 15, 791984. [CrossRef]

- Brain Fatigue. https://brainfatigue.se/en/homepage/. 2020. 17 March.

- Gulati, A. (2015). Understanding neurogenesis in the adult human brain. Indian journal of pharmacology, 47(6), 583–584. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A. A. , Amruta, N., Pinteaux, E., & Bix, G. J. (2021). Neurogenesis After Stroke: A Therapeutic Perspective. Translational stroke research, 12(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ceanga, M. , Dahab, M., Witte, O. W., & Keiner, S. (2021). Adult Neurogenesis and Stroke: A Tale of Two Neurogenic Niches. Frontiers in neuroscience, 15, 700297. [CrossRef]

- Cuartero, M. I. , García-Culebras, A., Torres-López, C., Medina, V., Fraga, E., Vázquez-Reyes, S., Jareño-Flores, T., García-Segura, J. M., Lizasoain, I., & Moro, M. Á. (2021). Post-stroke Neurogenesis: Friend or Foe?. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology, 9, 657846. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan M, Kushwaha R, Acharya BS, Kumar A, Chakravarty S. Cerebral stroke-induced neurogenesis: insights and therapeutic implications. Explor Neuroprot Ther. 2024;4:172–97. [CrossRef]

- Niklison-Chirou, M.V.; Agostini, M.; Amelio, I.; Melino, G. Regulation of Adult Neurogenesis in Mammalian Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, K.M. , Song, H., & Ming, G. Biochemistry of Neurogenesis, Metabolism Vitamins and Hormones, Encyclopedia of Biological Chemistry, 2013, 196-201. [CrossRef]

- Shabani, Z. , Mahmoudi, J. ( 51(4), 287–296. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culig, L. , Chu, X., & Bohr, V. A. (2022). Neurogenesis in aging and age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing research reviews, 78, 101636. [CrossRef]

- Darbinyan, V. , Aslanyan, G., Amroyan, E., Gabrielyan, E., Malmström, C., & Panossian, A. (2007). Clinical trial of Rhodiola rosea L. extract SHR-5 in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Nordic journal of psychiatry, 61(5), 343–348. [CrossRef]

- Darbinyan, V. , Kteyan, A., Panossian, A., Gabrielian, E., Wikman, G., & Wagner, H. (2000). Rhodiola rosea in stress induced fatigue--a double blind cross-over study of a standardized extract SHR-5 with a repeated low-dose regimen on the mental performance of healthy physicians during night duty. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 7(5), 365–371. [CrossRef]

- Amsterdam, J. D. , & Panossian, A. G. ( 23(7), 770–783. [CrossRef]

- Aslanyan, G. , Amroyan, E., Gabrielyan, E., Nylander, M., Wikman, G., & Panossian, A. (2010). Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised study of single dose effects of ADAPT-232 on cognitive functions. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 17(7), 494–499. [CrossRef]

- Hovhannisyan A, Nylander M, Wikman G, Panossian A (2015) Efficacy of Adaptogenic Supplements on Adapting to Stress: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Athl Enhancement 4:4. [CrossRef]

- Mariage, P. A. , Hovhannisyan, A., & Panossian, A. G. (2020). Efficacy of Panax ginseng Meyer Herbal Preparation HRG80 in Preventing and Mitigating Stress-Induced Failure of Cognitive Functions in Healthy Subjects: A Pilot, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 13(4), 57. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, E. M. , von Schéele, B., & Panossian, A. G. (2009). A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of the standardised extract shr-5 of the roots of Rhodiola rosea in the treatment of subjects with stress-related fatigue. Planta medica, 75(2), 105–112. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. 2024. A: Herba Sideritis, 1005; 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. G. , Efferth, T., Shikov, A. N., Pozharitskaya, O. N., Kuchta, K., Mukherjee, P. K., Banerjee, S., Heinrich, M., Wu, W., Guo, D. A., Wagner, H. (2020). Evolution of the adaptogenic concept from traditional use to medical systems: Pharmacology of stress- and aging-related diseases. Medicinal research reviews, 41(1), 630–703. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Amsterdam J. Chapter 8: Adaptogens in psychiatric practice. In: Gerbarg PL, Muskin PR, Brown RP, eds. Complementary and Integrative Treatments in Psychiatric Practice. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2017:155-181.

- Panossian, A. , Hambardzumyan M, Hovhanissyan A, Wikman G. The adaptogens rhodiola and schizandra modify the response to immobilization stress in rabbits by suppressing the increase of phosphorylated stress-activated protein kinase, nitric oxide and cortisol. Drug Target Insights. 2007;2:39-54. Epub 2007 Feb 16. PMCID: PMC3155223. [PubMed]

- Panossian, A. , Nikoyan, N., Ohanyan, N., Hovhannisyan, A., Abrahamyan, H., Gabrielyan, E., Wikman, G. (2008). Comparative study of Rhodiola preparations on behavioral despair of rats. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 15(1-2), 84–91. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Wikman, G., Kaur, P., & Asea, A. (2009). Adaptogens exert a stress-protective effect by modulation of expression of molecular chaperones. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 16(6-7), 617–622. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Wikman G, Kaur P, Asea A. Molecular chaperones as mediators of stress protective effect of plant adaptogens. In: Asea AAA, Pedersen BK, eds. Heat Shock Proteins and Whole Body Physiology. Vol 5. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London, New York: Springer; 2010:351-364.

- Panossian, A. , Wikman, G. (2009). Evidence-based efficacy of adaptogens in fatigue and molecular mechanisms related to their stress-protective activity. Current clinical pharmacology, 4(3), 198–219. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Wikman, G. (2010). Effects of Adaptogens on the Central Nervous System and the Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Their Stress-Protective Activity. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 3(1), 188–224. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A.G. , 2003. Adaptogens: tonic herbs for fatigue and stress. Altern. Compliment. Ther. 9: 327–332. https://www.researchgate. 2448. [Google Scholar]

- Panossian, A.G. , 2013. Adaptogens in mental and behavioral disorders. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 36(1), 49–64. [CrossRef]

- Goyvaerts, B. , & Bruhn, S. (2012). Rhodiola rosea special extract SHR-5 in burnout and fatigue syndrome. Erfahrungsheilkunde, 61, 79–83. [CrossRef]

- Ishaque, S. , Shamseer, L., Bukutu, C., & Vohra, S. (2012). Rhodiola rosea for physical and mental fatigue: a systematic review. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 12, 70. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. G. , Cho, J. H., Yoo, S. R., Lee, J. S., Han, J. M., Lee, N. H., Ahn, Y. C., & Son, C. G. (2013). Antifatigue effects of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. PloS one, 8(4), e61271. [CrossRef]

- Lekomtseva, Y. , Zhukova, I., & Wacker, A. (2017). Rhodiola rosea in Subjects with Prolonged or Chronic Fatigue Symptoms: Results of an Open-Label Clinical Trial. Complementary medicine research, 24(1), 46–52. [CrossRef]

- Lu, G. , Liu, Z., Wang, X., & Wang, C. (2021). Recent Advances in Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer as a Herb for Anti-Fatigue: An Effects and Mechanisms Review. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 10(5), 1030. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J. K. , & Müller, W. E. (2024). Multi-target drugs for the treatment of cognitive impairment and fatigue in post-COVID syndrome: focus on Ginkgo biloba and Rhodiola rosea. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996), 131(3), 203–212. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. J. , Lopresti, A. L., & Fairchild, T. J. (2023). Exploring the efficacy and safety of a novel standardized ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) root extract (Witholytin®) in adults experiencing high stress and fatigue in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 37(11), 1091–1104. [CrossRef]

- Spasov, A. A. , Wikman, G. K., Mandrikov, V. B., Mironova, I. A., & Neumoin, V. V. (2000). A double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the stimulating and adaptogenic effect of Rhodiola rosea SHR-5 extract on the fatigue of students caused by stress during an examination period with a repeated low-dose regimen. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 7(2), 85–89. [CrossRef]

- Teitelbaum, J. , & Goudie, S. (2021). An Open-Label, Pilot Trial of HRG80™ Red Ginseng in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Fibromyalgia, and Post-Viral Fatigue. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 15(1), 43. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. , Li, Y., Chau, C. I., Shi, J., Chen, X., Hu, H., & Ung, C. O. L. (2023). Efficacy and safety of traditional Chinese medicine for cancer-related fatigue: a systematic literature review of randomized controlled trials. Chinese medicine, 18(1), 142. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova Stojcheva, E. , & Quintela, J. C. (2022). The Effectiveness of Rhodiola rosea L. Preparations in Alleviating Various Aspects of Life-Stress Symptoms and Stress-Induced Conditions-Encouraging Clinical Evidence. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 27(12), 3902. [CrossRef]

- Esmaealzadeh, N. , Iranpanah, A., Sarris, J., & Rahimi, R. (2022). A literature review of the studies concerning selected plant-derived adaptogens and their general function in body with a focus on animal studies. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 105, 154354. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. , & Rauf, A. (2017). Adaptogenic herb ginseng (Panax) as medical food: Status quo and future prospects. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 85, 120–127. [CrossRef]

- Chan S., W. (2012). Panax ginseng, Rhodiola rosea and Schisandra chinensis. International journal of food sciences and nutrition, 63 Suppl 1, 75–81. [CrossRef]

- Todorova, V. , Ivanov, K. ( 11(1), 64. [CrossRef]

- Todorova, V. , Ivanov, K., Delattre, C., Nalbantova, V., Karcheva-Bahchevanska, D., & Ivanova, S. (2021). Plant Adaptogens-History and Future Perspectives. Nutrients, 13(8), 2861. [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, L. , & Perfumi, M. (2007). Rhodiola rosea L. extract reduces stress- and CRF-induced anorexia in rats. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 21(7), 742–750. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Z. , Huang, B. K., Ye, Q., & Qin, L. P. (2011). Bioactivity-guided fractionation for anti-fatigue property of Acanthopanax senticosus. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 133(1), 213–219. [CrossRef]

- Dimpfel, W. (2014). Neurophysiological effects of Rhodiola rosea extract containing capsules (A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study). 3 157–165. https://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/article/10.11648/j.ijnfs.20140303.

- Dimpfel, W. , Mariage, P. A., & Panossian, A. G. (2021). Effects of Red and White Ginseng Preparations on Electrical Activity of the Brain in Elderly Subjects: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Three-Armed Cross-Over Study. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 14(3), 182. [CrossRef]

- Dimpfel, W. , Schombert, L., Keplinger-Dimpfel, I. K., & Panossian, A. (2020). Effects of an Adaptogenic Extract on Electrical Activity of the Brain in Elderly Subjects with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Two-Armed Cross-Over Study. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 13(3), 45. [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A. F. , Derosa, G., Brillante, R., Bernardi, R., Nascetti, S., & Gaddi, A. (2004). Effects of Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus maxim.) on elderly quality of life: a randomized clinical trial. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. Supplement, (9), 69–73. [CrossRef]

- Reay, J. L. , Kennedy, D. B. ( 19(4), 357–365. [CrossRef]

- Reay, J. L. , Kennedy, D. O., & Scholey, A. B. (2006). Effects of Panax ginseng, consumed with and without glucose, on blood glucose levels and cognitive performance during sustained 'mentally demanding' tasks. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 20(6), 771–781. [CrossRef]

- Tardy, A. L. , Bois De Fer, B., Cañigueral, S., Kennedy, D., Scholey, A., Hitier, S., Aran, A., & Pouteau, E. (2021). Reduced Self-Perception of Fatigue after Intake of Panax ginseng Root Extract (G115®) Formulated with Vitamins and Minerals-An Open-Label Study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(12), 6257. [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, P. J. , Kennedy, D. O., & Stahl, S. (2021). Mental energy: plausible neurological mechanisms and emerging research on the effects of natural dietary compounds. Nutritional neuroscience, 24(11), 850–864. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Hamm, R., Kadioglu, O., Wikman, G., Efferth, T. (2013). Synergy and Antagonism of Active Constituents of ADAPT-232 on Transcriptional Level of Metabolic Regulation of Isolated Neuroglial Cells. Frontiers in neuroscience, 7, 16. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Hamm, R., Wikman, G., Efferth, T. (2014). Mechanism of action of Rhodiola, salidroside, tyrosol and triandrin in isolated neuroglial cells: an interactive pathway analysis of the downstream effects using RNA microarray data. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 21(11), 1325–1348. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Abdelfatah, S., & Efferth, T. (2021). Network Pharmacology of Red Ginseng (Part I): Effects of Ginsenoside Rg5 at Physiological and Sub-Physiological Concentrations. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 14(10), 999. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Abdelfatah, S., & Efferth, T. (2021). Network Pharmacology of Ginseng (Part II): The Differential Effects of Red Ginseng and Ginsenoside Rg5 in Cancer and Heart Diseases as Determined by Transcriptomics. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 14(10), 1010. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Abdelfatah, S., & Efferth, T. (2022). Network Pharmacology of Ginseng (Part III): Antitumor Potential of a Fixed Combination of Red Ginseng and Red Sage as Determined by Transcriptomics. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 15(11), 1345. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Efferth, T. ( 15(9), 1051. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Seo, E. J., Efferth, T. (2018). Novel molecular mechanisms for the adaptogenic effects of herbal extracts on isolated brain cells using systems biology. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 50, 257–284. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Seo, E. J., & Efferth, T. (2019). Effects of anti-inflammatory and adaptogenic herbal extracts on gene expression of eicosanoids signaling pathways in isolated brain cells. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 60, 152881. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Lemerond, T., Efferth, T. (2024). State-of-the-Art Review on Botanical Hybrid Preparations in Phytomedicine and Phytotherapy Research: Background and Perspectives. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 17(4), 483. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. , Jiang, T., Huang, H., & Zeng, J. (2023). Post-stroke fatigue: a review of development, prevalence, predisposing factors, measurements, and treatments. Frontiers in neurology, 14, 1298915. [CrossRef]

- Hao, D. L. , Li, J. M., Xie, R., Huo, H. R., Xiong, X. J., Sui, F., & Wang, P. Q. (2023). The role of traditional herbal medicine for ischemic stroke: from bench to clinic-A critical review. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 109, 154609. [CrossRef]

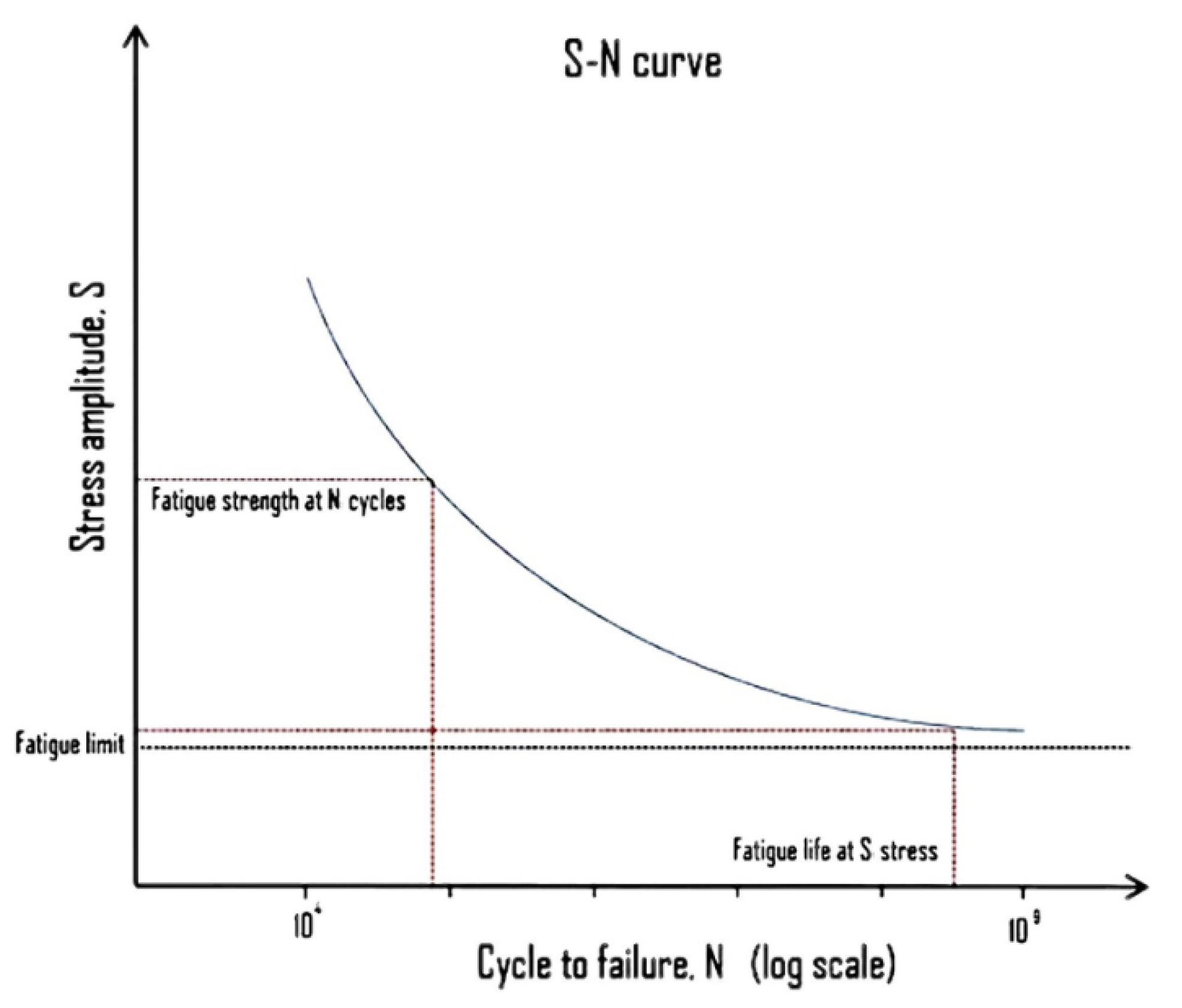

- What is Fatigue Life – S-N Curve – Woehler Curve – Definition. https://material-properties.org/what-is-fatigue-life-s-n-curve-woehler-curve-definition/?utm_content=cmp-true. (assessed ). 17 January.

- Sadek, Prof. J. Bergström, Dr. N. Hallbäck, Dr. C. Burman, 2020. Fatigue Strength and Fracture Mechanisms in theVery-High-Cycle-Fatigue Regime of Automotive Steels. Steel Research Int. 2020, 91, 2000060. [CrossRef]

- Stress. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/stress. (assessed ). 17 January.

- Fatigue. https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/psychosocial/fatigue.pdf. (assessed ). 17 January.

- Cannon, WB. Stresses and strains of homeostasis. Am J Med Sci. 1935;189:1-14.

- Selye, H. Confusion and controversy in the stress field. J. Human Stress 1, 37–44 (1975).

- Selye, H. Stress without distress. Brux. Med. 56, 205–210 (1976).

- Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The concept of stress system disorders: overview of behavioral and physical homeostasis. JAMA. 1992;267:1244-1252.

- Chrousos G., P. (2009). Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nature reviews. Endocrinology, 5(7), 374–381. [CrossRef]

- Stratakis, C. A. , & Chrousos, G. P. ( 771, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Phillips M., R. (2009). Is distress a symptom of mental disorders, a marker of impairment, both or neither?. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 8(2), 91–92.

- Bienertova-Vasku, J. , Lenart, P., & Scheringer, M. (2020). Eustress and Distress: Neither Good Nor Bad, but Rather the Same?. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology, 42(7), e1900238. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. , Zhou, L., Zhang, X., Yang, X., Niedermann, G., & Xue, J. (2022). Psychological distress and eustress in cancer and cancer treatment: Advances and perspectives. Science advances, 8(47), eabq7982. [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. Stress (1950). Acta Medical Publisher: Montreal: 1-127.

- Fink, G. 2000. Encyclopedia of Stress. Vols. 1–3. New York: Academic Press. eBook ISBN: 9780080569772. https://shop.elsevier. 0569. [Google Scholar]

- Panossian, A. , 2017. Understanding adaptogenic activity: specificity of the pharmacological action of adaptogens and other phytochemicals. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1401(1), 49–64. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Wagner, H. (2005). Stimulating effect of adaptogens: an overview with particular reference to their efficacy following single dose administration. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 19(10), 819–838. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H. , Nörr, H., & Winterhoff, H. (1994). Plant adaptogens. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 1(1), 63–76. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, H.R. , 2011. Mental energy and fatigue: science and the consumer. In: Kanarek, R.B., Lieberman, H.R. (Eds.), Diet, Brain, Behavior: Practical Implications. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 1–6.

- Mizuno, K. , Tanaka, M., Yamaguti, K., Kajimoto, O., Kuratsune, H., & Watanabe, Y. (2011). Mental fatigue caused by prolonged cognitive load associated with sympathetic hyperactivity. Behavioral and brain functions : BBF, 7, 17. [CrossRef]

- Boksem, M. A. , & Tops, M. (2008). Mental fatigue: costs and benefits. Brain research reviews, 59(1), 125–139. [CrossRef]

- Craik F., I. (2014). Effects of distraction on memory and cognition: a commentary. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 841. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M. , Ishii, A., & Watanabe, Y. (2014). Neural effects of mental fatigue caused by continuous attention load: a magnetoencephalography study. Brain research, 1561, 60–66. [CrossRef]

- Billones, R. , Liwang, J. K., Butler, K., Graves, L., & Saligan, L. N. (2021). Dissecting the fatigue experience: A scoping review of fatigue definitions, dimensions, and measures in non-oncologic medical conditions. Brain, behavior, & immunity - health, 15, 100266. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, J. A. , Caldwell, J. R. ( 96, 272–289. [CrossRef]

- Palm, S. , Ronnback, L., Johansson, B., 2017. Long-term mental fatigue after traumatic brain injury and impact on employment status. J. Rehabil. Med. 49 (3), 228–233. [CrossRef]

- Kluger, B. M. , Krupp, L. B., & Enoka, R. M. (2013). Fatigue and fatigability in neurologic illnesses: proposal for a unified taxonomy. Neurology, 80(4), 409–416. [CrossRef]

- Rönnbäck L and Johansson, B. (2020). https://brainfatigue.se/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Leaftlet-About-Brain-Fatigue. 17 March.

- Mental fatigue / Brain fatigue. https://www.gu.se/forskning/mental-trotthet-hjarntrotthet. 17 March.

- Cantor, J. B. , Gordon, W., & Gumber, S. (2013). What is post TBI fatigue?. NeuroRehabilitation, 32(4), 875–883. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Arias, L. A. , Yeshokumar, A. K., Glassberg, B., Sumowski, J. F., Easton, A., Probasco, J. C., & Venkatesan, A. (2021). Fatigue in Survivors of Autoimmune Encephalitis. Neurology(R) neuroimmunology & neuroinflammation, 8(6), e1064. [CrossRef]

- Hiploylee, C. , Dufort, P. A., Davis, H. S., Wennberg, R. A., Tartaglia, M. C., Mikulis, D., Hazrati, L. N., & Tator, C. H. (2017). Longitudinal Study of Postconcussion Syndrome: Not Everyone Recovers. Journal of neurotrauma, 34(8), 1511–1523. [CrossRef]

- Pearce AJ, Tommerdahl M, King DA. Neurophysiological abnormalities in individuals with persistent post-concussion symptoms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;408:272-81.

- Stålnacke, B. M. , Elgh, E., & Sojka, P. (2007). One-year follow-up of mild traumatic brain injury: cognition, disability and life satisfaction of patients seeking consultation. Journal of rehabilitation medicine, 39(5), 405–411. [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson LG, Julin P, Norén T. Inflammation, long-term fatigue and pain - updating the state of knowledge. The medical journal. 2020;117:20008.

- Pietrzak, P. , & Hanke, W. (2024). The long COVID and its mental health manifestations - the review of literature. International journal of occupational medicine and environmental health, 37(3), 360–380. [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J. D. , Russo, S. J., Gallagher, R., & Simon, N. M. (2024). Acute and long-term effects of COVID-19 on brain and mental health: A narrative review. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 123, 928–945. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B. W. J. H. , Benros, M. E., Klein, R. S., & Vinkers, C. H. (2022). How COVID-19 shaped mental health: from infection to pandemic effects. Nature medicine, 28(10), 2027–2037. [CrossRef]

- Campos, M. C. , Nery, T., Starke, A. C., de Bem Alves, A. C., Speck, A. E., & S Aguiar, A. (2022). Post-viral fatigue in COVID-19: A review of symptom assessment methods, mental, cognitive, and physical impairment. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 142, 104902. [CrossRef]

- Ceban, F. , Ling, S., Lui, L. M. W., Lee, Y., Gill, H., Teopiz, K. M., Rodrigues, N. B., Subramaniapillai, M., Di Vincenzo, J. D., Cao, B., Lin, K., Mansur, R. B., Ho, R. C., Rosenblat, J. D., Miskowiak, K. W., Vinberg, M., Maletic, V., & McIntyre, R. S. (2022). Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 101, 93–135. [CrossRef]

- Irestorm E, Tonning Olsson I, Johansson B, Ora I. Cognitive fatigue in relation to depressive symptoms after treatment for childhood cancer. BMC Psychology. 2020;8(1):31. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. , Starmark, A., Berglund, P., Rödholm, M., & Rönnbäck, L. (2010). A self-assessment questionnaire for mental fatigue and related symptoms after neurological disorders and injuries. Brain injury, 24(1), 2–12. [CrossRef]

- Johansson B, Rönnbäck L. Evaluation of the mental fatigue scale and its relation to cognitive and emotional functioning after traumatic brain injury or stroke. Int J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;2(1):182. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. Mental fatigue after mild traumatic brain injury in relation to cognitive tests and brain imaging methods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist, G. , & Malmgren, H. ( 373, 5–17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, B. , Berglund, P., & Rönnbäck, L. (2009). Mental fatigue and impaired information processing after mild and moderate traumatic brain injury. Brain injury, 23(13-14), 1027–1040. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. , & Rönnbäck, L. ( 27(7), 1047–1055. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federico, F. , Marotta, A., Adriani, T., Maccari, L., & Casagrande, M. (2013). Attention network test--the impact of social information on executive control, alerting and orienting. Acta psychologica, 143(1), 65–70. [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. , Tran, Y. ( 49(4), 574–582. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi P, Ru H, Gao L, Zhang X, Zhou T, Tian Y, Thakor N, Bezerianos A, Li J, Sun Y. 2019. Neuralmechanisms of mental fatigue revisited: new insights from the brain connectome. Engineering 5(2):276–286 DOI 10.1016/j.eng.2018.11.025.

- Tran, Y. , Craig, A., Craig, R., Chai, R., & Nguyen, H. (2020). The influence of mental fatigue on brain activity: Evidence from a systematic review with meta-analyses. Psychophysiology, 57(5), e13554. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka M, Ishii A, Watanabe Y. 2015. Effects of mental fatigue on brain activity and cognitive performance: a magnetoencephalography study. Anatomy & Physiology: Current Research S4:1–4 DOI 10.4172/2161-0940.S4-002.

- Duke JW, Rubin DA, Daly W, Hackney AC (2007) Influence of prolonged exercise on the 24-hour free testosterone-cortisol ratio hormonal profile. Med Sport 11: 48-50. PMCID: PMC8555934. [PubMed]

- Viru, A. , & Viru, M. (2004). Cortisol--essential adaptation hormone in exercise. International journal of sports medicine, 25(6), 461–464. [CrossRef]

- Adlercreutz, H. , Härkönen, M. ( 7 Suppl 1, 27–28. [CrossRef]

- Urhausen, A. , Gabriel, H. ( 20(4), 251–276. [CrossRef]

- Urhausen, A. , & Kindermann, W. ( 8(5), 305–308. [CrossRef]

- Fry, R. W. , Morton, A. ( 12(1), 32–65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeli, A. , Minetto, M., Dovio, A., & Paccotti, P. (2004). The overtraining syndrome in athletes: a stress-related disorder. Journal of endocrinological investigation, 27(6), 603–612. [CrossRef]

- Urhausen, A. , Kullmer, T., & Kindermann, W. (1987). A 7-week follow-up study of the behaviour of testosterone and cortisol during the competition period in rowers. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology, 56(5), 528–533. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman H., R. (2006). Mental energy: Assessing the cognition dimension. Nutrition reviews, 64(7 Pt 2), S10–S13. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman H., R. (2007). Cognitive methods for assessing mental energy. Nutritional neuroscience, 10(5-6), 229–242. [CrossRef]

- Kuczenski, R. , & Segal, D. S. (1997). Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine: comparison with amphetamine. Journal of neurochemistry, 68(5), 2032–2037. [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N. D. , Wang, G., Fowler, J. S., Logan, J., Gerasimov, M., Maynard, L., Ding, Y., Gatley, S. J., Gifford, A., & Franceschi, D. (2001). Therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate significantly increase extracellular dopamine in the human brain. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 21(2), RC121. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Z. , Guo, Y. D., Li, H. M., Wang, R. Z., Guo, S. G., & Du, Y. F. (2017). Protection against cerebral infarction by Withaferin A involves inhibition of neuronal apoptosis, activation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, and reduced intimal hyperplasia via inhibition of VSMC migration and matrix metalloproteinases. Advances in medical sciences, 62(1), 186–192. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. , Andréll, P., Rönnbäck, L., & Mannheimer, C. (2020). Follow-up after 5.5 years of treatment with methylphenidate for mental fatigue and cognitive function after a mild traumatic brain injury. Brain injury, 34(2), 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. , Wentzel, A. ( 29(6), 758–765. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M. K. L. , Johansson, B., Carlsson, M. L., Schuit, R. C., & Rönnbäck, L. (2020). Effect of the monoaminergic stabiliser (-)-OSU6162 on mental fatigue following stroke or traumatic brain injury. Acta neuropsychiatrica, 32(6), 303–312. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. , Bjuhr, H., & Rönnbäck, L. (2012). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) improves long-term mental fatigue after stroke or traumatic brain injury. Brain injury, 26(13-14), 1621–1628. [CrossRef]

- Berginström, N. , Nordström, P., Schuit, R., & Nordström, A. (2017). The Effects of (-)-OSU6162 on Chronic Fatigue in Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation, 32(2), E46–E54. [CrossRef]

- Ulrichsen, K. M. , Kaufmann, T., Dørum, E. S., Kolskår, K. K., Richard, G., Alnæs, D., Arneberg, T. J., Westlye, L. T., & Nordvik, J. E. (2016). Clinical Utility of Mindfulness Training in the Treatment of Fatigue After Stroke, Traumatic Brain Injury and Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 912. [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P. , Kappos, L., Gensicke, H., D'Souza, M., Mohr, D. C., Penner, I. K., & Steiner, C. (2010). MS quality of life, depression, and fatigue improve after mindfulness training: a randomized trial. Neurology, 75(13), 1141–1149. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. , Bjuhr, H., Karlsson, M., Karlsson, J.-O., & Rönnbäck, L. (2015). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) delivered live on the Internet to individuals suffering from mental fatigue after an acquired brain injury. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1356–1365. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, B. , Carlsson, A., Carlsson, M. L., Karlsson, M., Nilsson, M. K., Nordquist-Brandt, E., & Rönnbäck, L. (2012). Placebo-controlled cross-over study of the monoaminergic stabiliser (-)-OSU6162 in mental fatigue following stroke or traumatic brain injury. Acta neuropsychiatrica, 24(5), 266–274. [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, K. L. , Ponsford, J. M. ( 28(4), 303–313. [CrossRef]

- Alarie, C. , Gagnon, I., Quilico, E., Teel, E., & Swaine, B. (2021). Physical Activity Interventions for Individuals With a Mild Traumatic Brain Injury:: A Scoping Review. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation, 36(3), 205–223. [CrossRef]

- Magistretti, P. J. , & Allaman, I. ( 86(4), 883–901. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rönnbäck, L. , and Hansson, E. (2004). On the potential role of glutamate transport in mental fatigue. J. Neuroinflamm. 1:22. [CrossRef]

- Mergenthaler, P. , Lindauer, U., Dienel, G. A., & Meisel, A. (2013). Sugar for the brain: the role of glucose in physiological and pathological brain function. Trends in neurosciences, 36(10), 587–597. [CrossRef]

- Prins, M. , Greco, T., Alexander, D., & Giza, C. C. (2013). The pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury at a glance. Disease models & mechanisms, 6(6), 1307–1315. [CrossRef]

- Abbott NJ, Rönnbäck L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(1):41-53. [CrossRef]

- Korte, S. M. , & Straub, R. H. (2019). Fatigue in inflammatory rheumatic disorders: pathophysiological mechanisms. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 58(Suppl 5), v35–v50. [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J. L. , Ngwenya, L. B., & McCullumsmith, R. E. (2019). Neurotransmitter changes after traumatic brain injury: an update for new treatment strategies. Molecular psychiatry, 24(7), 995–1012. [CrossRef]

- Hansson, E. , & Rönnbäck, L. (1995). Astrocytes in glutamate neurotransmission. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 9(5), 343–350. [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, C. J. , & Garfinkel, D. ( 123(2), 211–218. [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, A. M. , and Quastel, J. H. (1972). Locations of amino acids in brain slices from the rat. Tetrodotoxin-sensitive release of amino acids. Biochem. J. 128, 631–646. [CrossRef]

- Ottersen, O. P. , Zhang, N., & Walberg, F. (1992). Metabolic compartmentation of glutamate and glutamine: morphological evidence obtained by quantitative immunocytochemistry in rat cerebellum. Neuroscience, 46(3), 519–534. [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, P. (2001). Why is L-glutamine metabolism important to cells of the immune system in health, postinjury, surgery or infection?. The Journal of nutrition, 131(9 Suppl), 2515S–4S. [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, P. , Lima, M. M., Procopio, J., Pithon-Curi, T. C., Doi, S. Q., Bazotte, R. B., & Curi, R. (2003). Glutamine and glutamate as vital metabolites. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas, 36(2), 153–163. [CrossRef]

- Rothman, D. L. , Sibson, N. R., Hyder, F., Shen, J., Behar, K. L., & Shulman, R. G. (1999). In vivo nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of the relationship between the glutamate-glutamine neurotransmitter cycle and functional neuroenergetics. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 354(1387), 1165–1177. [CrossRef]

- Yudkoff, M. , Nissim, I., Daikhin, Y., Lin, Z. P., Nelson, D., Pleasure, D., & Erecinska, M. (1993). Brain glutamate metabolism: neuronal-astroglial relationships. Developmental neuroscience, 15(3-5), 343–350. [CrossRef]

- Choi D., W. (1992). Excitotoxic cell death. Journal of neurobiology, 23(9), 1261–1276. [CrossRef]

- Hertz, L. , and Zielke, H. R. (2004). Astrocytic control of glutamatergic activity: astrocytes as stars of the show. Trends Neurosci. 27, 735–743. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. , & Danbolt, N. C. (2014). Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the healthy brain. Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996), 121(8), 799–817. [CrossRef]

- Norenberg, M. D. , & Martinez-Hernandez, A. ( 161(2), 303–310. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Arellano, J. J. , Parpura, V., Zorec, R., & Verkhratsky, A. (2016). Astrocytes in physiological aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience, 323, 170–182. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J. V. , Jakobsen, E., Westi, E. W., Lie, M. E. K., Voss, C. M., Aldana, B. I., Schousboe, A., Wellendorph, P., Bak, L. K., Pinborg, L. H., & Waagepetersen, H. S. (2020). Extensive astrocyte metabolism of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) sustains glutamine synthesis in the mammalian cerebral cortex. Glia, 68(12), 2601–2612. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. , Hua, Z., & Li, Z. (2024). The role of glutamate and glutamine metabolism and related transporters in nerve cells. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics, 30(2), e14617. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, S. , Nakamura, T., Nidaira, T., Nakamura, K., Ooashi, N., Ito, E., Watase, K., Tanaka, K., Wada, K., Kudo, Y., & Miyakawa, H. (1999). Optical detection of synaptically induced glutamate transport in hippocampal slices. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 19(7), 2580–2588. [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, J. D. , Dykes-Hoberg, M. F. ( 16(3), 675–686. [CrossRef]

- Kim, A. Y. , & Baik, E. J. ( 44(1), 147–153. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J. V. , Markussen, K. H., Jakobsen, E., Schousboe, A., Waagepetersen, H. S., Rosenberg, P. A., & Aldana, B. I. (2021). Glutamate metabolism and recycling at the excitatory synapse in health and neurodegeneration. Neuropharmacology, 196, 108719. [CrossRef]

- Harris JJ, Jolivet R, Attwell D. Synaptic energy use and supply. Neuron. 2012 Sep 06;75(5):762-77.

- Dienel G., A. (2019). Brain Glucose Metabolism: Integration of Energetics with Function. Physiological reviews, 99(1), 949–1045. [CrossRef]

- Mink, J. W. , Blumenschine, R. J., & Adams, D. B. (1981). Ratio of central nervous system to body metabolism in vertebrates: its constancy and functional basis. The American journal of physiology, 241(3), R203–R212. [CrossRef]

- Dunn J, Grider MH. Physiology, Adenosine Triphosphate. [Updated 2023 Feb 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 5531.

- Meurer, F. , Do, H. T., Sadowski, G., & Held, C. (2017). Standard Gibbs energy of metabolic reactions: II. Glucose-6-phosphatase reaction and ATP hydrolysis. Biophysical chemistry, 223, 30–38. [CrossRef]

- Attwell, D. , & Laughlin, S. B. (2001). An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 21(10), 1133–1145. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N. S. , Tuteja, R. ( 452(1), 55–68. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H. Extracellular ATP and other nucleotides-ubiquitous triggers of intercellular messenger release. Purinergic Signal. 2016 Mar;12(1):25-57. [CrossRef]

- Kamenetsky, M. , Middelhaufe, S., Bank, E. M., Levin, L. R., Buck, J., & Steegborn, C. (2006). Molecular details of cAMP generation in mammalian cells: a tale of two systems. Journal of molecular biology, 362(4), 623–639. [CrossRef]

- Cunnane, S. C. , Trushina, E., Morland, C., Prigione, A., Casadesus, G., Andrews, Z. B., Beal, M. F., Bergersen, L. H., Brinton, R. D., de la Monte, S., Eckert, A., Harvey, J., Jeggo, R., Jhamandas, J. H., Kann, O., la Cour, C. M., Martin, W. F., Mithieux, G., Moreira, P. I., Murphy, M. P., … Millan, M. J. (2020). Brain energy rescue: an emerging therapeutic concept for neurodegenerative disorders of ageing. Nature reviews. Drug discovery, 19(9), 609–633. [CrossRef]

- Peters, A. , Sprengell, M., & Kubera, B. (2022). The principle of 'brain energy on demand' and its predictive power for stress, sleep, stroke, obesity and diabetes. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 141, 104847. [CrossRef]

- Canguilhem, G. Essai sur quelques problèmes concernant le normal et le pathologique. 1943. In: Fawcett CR, Cohen RS, trans. The Normal and the Pathological. New York: Zone Books; 1991. www.thelancet.com Vol 373 , 2009; https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(09)60456-6.pdf; https://www.cairn.info/le-normal-et-le-pathologique--9782130619505.htm ; [PDF] Le Normal et le Pathologique | Semantic Scholar; https://www.undergroundbooks. 7 March 1155. [Google Scholar]

- Selye, H. Experimental evidence supporting the conception of "adaptation energy". Am J Physiol. 1938;123:758-765.

- Panossian, A. , Wikman, G., Wagner, H. 1999. Plant adaptogens. III. Earlier and more recent aspects and concepts on their mode of action. Phytomedicine 6: 287–300. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Wikman, G. Effect of adaptogens on the central nervous system. Arq. Bras. Fitomed. Cient. 2005, 2, 108–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis,W. H., 2nd ed.; Lewis, W.H., Elwin-Lewis, M.P.F., Eds.; JohnWiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brekhman, I. I. , & Dardymov, I. V. ( 9, 419–430. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Gerbarg P. Potential use of plant adaptogens in age-related disorders. In: Lavretsky H, Sajatovic M, Reynolds CF, III, eds. Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Interventions in Mental Health and Aging. 1: New York: Oxford University Press; 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EMEA/HMPC/102655/2007. Reflection paper on the adaptogenic concept. London; 2008. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document…/WC500003646.

- Panossian, A. , Brendler, T. 2020. The Role of Adaptogens in Prophylaxis and Treatment of Viral Respiratory Infections. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 13(9), 236. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Wikman, G. ( 6, 6. [CrossRef]

- Rosas, P. C. , Nagaraja, G. M., Kaur, P., Panossian, A., Wickman, G., Garcia, L. R., Al-Khamis, F. A., & Asea, A. A. (2016). Hsp72 (HSPA1A) Prevents Human Islet Amyloid Polypeptide Aggregation and Toxicity: A New Approach for Type 2 Diabetes Treatment. PloS one, 11(3), e0149409. [CrossRef]

- Asea, A. , Kaur, P., Panossian, A., & Wikman, K. G. (2013). Evaluation of molecular chaperons Hsp72 and neuropeptide Y as characteristic markers of adaptogenic activity of plant extracts. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 20(14), 1323–1329. [CrossRef]

- Borgonetti, V. , Governa, P., Biagi, M., Dalia, P., & Corsi, L. (2020). Rhodiola rosea L. modulates inflammatory processes in a CRH-activated BV2 cell model. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 68, 153143. [CrossRef]

- Lee, F. T. , Kuo, T. T. ( 37(3), 557–572. [CrossRef]

- Yavropoulou MP, Sfikakis PP, Chrousos GP. Immune System Effects on the Endocrine System. [Updated 2023 Nov 8]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 2791.

- Sugama, S. , & Kakinuma, Y. (2020). Stress and brain immunity: Microglial homeostasis through hy-pothalamus-pituitary-adrenal gland axis and sympathetic nervous system. Brain, behavior, & immunity - health, 7, 100111. [CrossRef]

- Tsigos C, Kyrou I, Kassi E, & Chrousos, G. P. Stress: Endocrine Physiology and Pathophysiology. [Updated 2020 Oct 17]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 2789.

- Xia, N. , Li, J., Wang, H., Wang, J., & Wang, Y. (2016). Schisandra chinensis and Rhodiola rosea exert an anti-stress effect on the HPA axis and reduce hypothalamic c-Fos expression in rats subjected to repeated stress. Experimental and therapeutic medicine, 11(1), 353–359. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q. G. , Zeng, Y. S., Qu, Z. Q., Tang, J. Y., Qin, Y. J., Chung, P., Wong, R., & Hägg, U. (2009). The effects of Rhodiola rosea extract on 5-HT level, cell proliferation and quantity of neurons at cerebral hippocampus of depressive rats. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 16(9), 830–838. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. , Wang, Y., Li, H., Xiong, R., Zhao, Z., Chu, X., Li, Q., Sun, S., & Chen, S. (2016). Neuroprotective effects of salidroside through PI3K/Akt pathway activation in Alzheimer's disease models. Drug design, development and therapy, 10, 1335–1343. [CrossRef]

- Stancheva, S.L. , Mosharrof, A., 1987. Effect of the extract of Rhodiola rosea L. on the content of the brain biogenic monoamines. Med. Physiol. CR Acad. Bulg. Sci. 40, 85–87.

- Chiang, H. M. , Chen, H. C., Wu, C. S., Wu, P. Y., & Wen, K. C. (2015). Rhodiola plants: Chemistry and biological activity. Journal of food and drug analysis, 23(3), 359–369. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L. , Wei, T., Gao, J., Chang, X., He, H., Miao, M., & Yan, T. (2015). Salidroside attenuates lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced serum cytokines and depressive-like behavior in mice. Neuroscience letters, 606, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Moise, G. , Jîjie, A. R., Moacă, E. A., Predescu, I. A., Dehelean, C. A., Hegheș, A., Vlad, D. C., Popescu, R., & Vlad, C. S. (2024). Plants' Impact on the Human Brain-Exploring the Neuroprotective and Neurotoxic Potential of Plants. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 17(10), 1339. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Gabrielian, E., & Wagner, H. (1999). On the mechanism of action of plant adaptogens with particular reference to cucurbitacin R diglucoside. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 6(3), 147–155. [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M. P. , & Cheng, A. (2006). Neurohormetic phytochemicals: Low-dose toxins that induce adaptive neuronal stress responses. Trends in neurosciences, 29(11), 632–639. [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M. P. , Son, T. G., & Camandola, S. (2007). Viewpoint: mechanisms of action and therapeutic potential of neurohormetic phytochemicals. Dose-response : a publication of International Hormesis Society, 5(3), 174–186. [CrossRef]

- Mattson M., P. (2008). Dietary factors, hormesis and health. Ageing research reviews, 7(1), 43–48. [CrossRef]

- Son, T. G. , Camandola, S. P. ( 10(4), 236–246. [CrossRef]

- Rizzarelli, E. , & Calabrese, E. J. ( 1822(5), 753–783. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, A. (2018). Non-specific protein modifications may be novel mechanism underlying bioactive phytochemicals. Journal of clinical biochemistry and nutrition, 62(2), 115–123. [CrossRef]

- Dhabhar F., S. (2018). The short-term stress response - Mother nature's mechanism for enhancing protection and performance under conditions of threat, challenge, and opportunity. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology, 49, 175–192. [CrossRef]

- Mattson M., P. (2008). Hormesis and disease resistance: activation of cellular stress response pathways. Human & experimental toxicology, 27(2), 155–162. [CrossRef]

- Mattson M., P. (2015). WHAT DOESN"T KILL YOU.... Scientific American, 313(1), 40–45. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese E., J. (2014). Hormesis: a fundamental concept in biology. Microbial cell (Graz, Austria), 1(5), 145–149. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E. J. , & Mattson, M. P. (2024). The catabolic - anabolic cycling hormesis model of health and resilience. Ageing research reviews, 102, 102588. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese E., J. (2021). Hormesis Mediates Acquired Resilience: Using Plant-Derived Chemicals to Enhance Health. Annual review of food science and technology, 12, 355–381. [CrossRef]

- Saratikov, A.S. , Krasnov, E.A., 2004. Rhodiola rosea (Golden root) Fourth edition, Revised and Enlarged. Tomsk State University Publishing House, pp. 22–41.

- Panossian, A. , Wikman, G. (2008). Pharmacology of Schisandra chinensis Bail.: an overview of Russian research and uses in medicine. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 118(2), 183–212. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Wikman, G., Sarris, J. (2010). Rosenroot (Rhodiola rosea): traditional use, chemical composition, pharmacology and clinical efficacy. Phytomedicine: international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 17(7), 481–493. [CrossRef]

- Winston, D. Adaptogens: Herbs for Strength, Stamina, and Stress Relief; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Winston, D. Maimes, S: Adaptogens. Herbs for Strength, Stamina, and Stress Relief; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yance, DR. Adaptogens in herbal herbalism, Adaptogens in Medical Herbalism: Elite Herbs and Natural Compounds for Mastering Stress, Aging, and Chronic Disease. Healing Arts Press. 2013, pp.672. ISBN-13: 978-1-62055-100-4; https://adaptogensbook.

- Brown RP, Gerbarg PL, Graham B. The Rhodiola revolution: Transform Your Health with the Herbal Breakthrough of the 21st Century 2005,. https://www.amazon. 1594.

- Kuhn MA, Winston D. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 28 Mar 2012 - Medical - 592 pages; 2000 - Medical - 430 pages; https://books.google.se/books/about/Herbal_Therapy_and_Supplements.html?

- Der Marderosian A, Beutler JA. The review of Natural Products, 6th Edition Wolters; Kluwer Health Kluwer, 2010. 1672 pages.

- Samuelsson G, Bohlin L. Drugs of Natural Origin: A Treatise of Pharmacognosy. 6th ed. Stockholm: Swedish Academy of Pharmaceutical Sciences; 2009:776.

- Heinrich M, Barnes J, Prieto-Garcia J, Gibbons S, Williamson EM. Fundamentals of Pharmacognosy and Phytotherapy. 2nd Edition, Elsevier, 2012, pp 340. 9: 4th Edition, Elsevier, 2023, ISBN: 9780323834346; eBook ISBN, 2023.

- Bone K, Mills S. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. 2nd Edition - , 2012; 1056 pages. eBook ISBN: 9780702052972; https://www.sciencedirect. 31 December 9780.

- EMA/HMPC/232100/2011. Assessment report on Rhodiola rosea L., rhizoma et radix. Based on Article 16d (1), Article 16f and Article 16h of Directive 2001/83/EC as amended traditional use). Final. 27 March.

- EMA/HMPC/24177/2023. European Union herbal monograph on Rhodiola rosea L., rhizoma et radix. Draft – Revision 1. Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC), , pp.1-6. 19 July.

- EMA/HMPC/321232/2012. Assessment report on Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer, radix. Based on Article 16d (1), Article 16f and Article 16h of Directive 2001/83/EC as amended (traditional use). Final. 25 March.

- EMA/HMPC/680615/2013. Assessment report on Eleutherococcus senticosus (Rupr. et Maxim.) Maxim., radix. Based on Article 16d (1), Article 16f and Article 16h of Directive 2001/83/EC as amended (traditional use). Final. 25 March.

- Panossian, A. , 2023. Challenges in phytotherapy research. Frontiers in pharmacology, 14, 1199516. [CrossRef]

- Tao, H. , Wu, X., Cao, J., Peng, Y., Wang, A., Pei, J., Xiao, J., Wang, S., & Wang, Y. (2019). Rhodiola species: A comprehensive review of traditional use, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicity, and clinical study. Medicinal research reviews, 39(5), 1779–1850. [CrossRef]

- Dar, N. J. , Hamid, A., & Ahmad, M. (2015). Pharmacologic overview of Withania somnifera, the Indian Ginseng. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS, 72(23), 4445–4460. [CrossRef]

- Dar, N. J. , & Muzamil Ahmad (2020). Neurodegenerative diseases and Withania somnifera (L.): An update. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 256, 112769. [CrossRef]

- Zahiruddin, S. , Basist, P., Parveen, A., Parveen, R., Khan, W., Gaurav, & Ahmad, S. (2020). Ashwagandha in brain disorders: A review of recent developments. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 257, 112876. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S. , Chakraborty, S., Anand, U., Dey, S., Nandy, S., Ghorai, M., Saha, S. C., Patil, M. T., Kandimalla, R., Proćków, J., & Dey, A. (2021). Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal (Ashwagandha): A comprehensive review on ethnopharmacology, pharmacotherapeutics, biomedicinal and toxicological aspects. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 143, 112175. [CrossRef]

- Mikulska, P. , Malinowska, M., Ignacyk, M., Szustowski, P., Nowak, J., Pesta, K., Szeląg, M., Szklanny, D., Judasz, E., Kaczmarek, G., Ejiohuo, O. P., Paczkowska-Walendowska, M., Gościniak, A., & Cielecka-Piontek, J. (2023). Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera)-Current Research on the Health-Promoting Activities: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceutics, 15(4), 1057. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A. K. , Chatterjee, S. S., & Kumar, V. (2014). Adaptogenic potential of andrographolide: An active principle of the king of bitters (Andrographis paniculata). Journal of traditional and complementary medicine, 5(1), 42–50. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Gabrielian, E. ( 4(1), 85–99. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokoska, L. , & Janovska, D. (2009). Chemistry and pharmacology of Rhaponticum carthamoides: a review. Phytochemistry, 70(7), 842–855. [CrossRef]

- Kokoska, L. , & Janovska, D. (2009). Chemistry and pharmacology of Rhaponticum carthamoides: a review. Phytochemistry, 70(7), 842–855. [CrossRef]

- Rai, D. , Bhatia, G. K. ( 75(4), 823–830. [CrossRef]

- Valotto Neto, L. J. , Reverete de Araujo, M., Moretti Junior, R. C., Mendes Machado, N., Joshi, R. K., Dos Santos Buglio, D., Barbalho Lamas, C., Direito, R., Fornari Laurindo, L., Tanaka, M., & Barbalho, S. M. (2024). Investigating the Neuroprotective and Cognitive-Enhancing Effects of Bacopa monnieri: A Systematic Review Focused on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Apoptosis. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 13(4), 393. [CrossRef]

- Chien MY, Chuang CH, Chern CM, Liou KT, Liu DZ, Hou YC, et al. Salvianolic acid A alleviates ischemic brain injury through the inhibition of inflammation and apoptosis and the promotion of neurogenesis in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. (2016) 99:508–19. [CrossRef]

- Shu, T. , Pang, M. ( 153(1), 233–241. [CrossRef]

- Su, C. Y. , Ming, Q. L., Rahman, K., Han, T., & Qin, L. P. (2015). Salvia miltiorrhiza: Traditional medicinal uses, chemistry, and pharmacology. Chinese journal of natural medicines, 13(3), 163–182. [CrossRef]

- Chu, R. , Zhou, Y., Ye, C., Pan, R., & Tan, X. (2024). Advancements in the investigation of chemical components and pharmacological properties of Codonopsis: A review. Medicine, 103(26), e38632. [CrossRef]

- Guo, H. , Lou, Y. ( 15, 1415147. [CrossRef]

- Wróbel-Biedrawa, D. , & Podolak, I. (2024). Anti-Neuroinflammatory Effects of Adaptogens: A Mini-Review. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 29(4), 866. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.L. Network pharmacology: The next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Regenmortel, M.H. Reductionism and complexity in molecular biology. Scientists now have the tools to unravel biological and overcome the limitations of reductionism. E.M.B.O. Rep. 2004, 5, 1016–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fliri, A.F.; Loging, W.T.; Volkmann, R.A. Cause-effect relationships in medicine: A protein network perspective. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2010, 31, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klipp, E.; Wade, R.C.; Kummer, U. Biochemical network-based drug-target prediction. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Seo, E. J., Wikman, G., & Efferth, T. (2015). Synergy assessment of fixed combinations of Herba Andrographidis and Radix Eleutherococci extracts by transcriptome-wide microarray profiling. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 22(11), 981–992. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T. , Kawai, T., 2014. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front. Immunol. 5, 461. [CrossRef]

- Segalés, J. , Perdiguero, E., Muñoz-Cánoves, P., 2016. Regulation of muscle stem cell functions: a focus on the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 4. [CrossRef]

- Michael, J. , Marschallinger, J., Aigner, L., 2019. The leukotriene signaling pathway: a druggable target in Alzheimer's disease. Drug Discov. Today 24, 505–516. [CrossRef]

- Manev, H. , Uz, T., Sugaya, K., & Qu, T. (2000). Putative role of neuronal 5-lipoxygenase in an aging brain. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 14(10), 1464–1469. [CrossRef]

- Panossian, A. , Hovhannisyan A, Abrahamyan H, Gabrielyan E, Wikman G. Pharmacokinetics of active constituents of Rhodiola rosea SHR-5 extract. In: Gupta VK (ed.). Comprehensive bioactive natural products. Vol. 2: Efficacy, safety & clinical evaluation I. Studium press, Houston 2010, 307-329.

- Guo, N. , Zhu, M., Han, X., Sui, D., Wang, Y., & Yang, Q. (2014). The metabolism of salidroside to its aglycone p-tyrosol in rats following the administration of salidroside. PloS one, 9(8), e103648. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. , Sun, H. ( 54(7), 1166–1170. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E. J. , Dhawan, G., Kapoor, R., Agathokleous, E., & Calabrese, V. (2023). Rhodiola rosea and salidroside commonly induce hormesis, with particular focus on longevity and neuroprotection. Chemico-biological interactions, 380, 110540. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V. , Cornelius, C., Dinkova-Kostova, A. T., Calabrese, E. J., & Mattson, M. P. (2010). Cellular stress responses, the hormesis paradigm, and vitagenes: novel targets for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disorders. Antioxidants & redox signaling, 13(11), 1763–1811. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese E., J. (2020). Hormesis and Ginseng: Ginseng Mixtures and Individual Constituents Commonly Display Hormesis Dose Responses, Especially for Neuroprotective Effects. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 25(11), 2719. [CrossRef]

- Butterweck, V. , & Nahrstedt, A. (2012). What is the best strategy for preclinical testing of botanicals? A critical perspective. Planta medica, 78(8), 747–754. [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, L. , Funari, C. ( 23(2), 130–142. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattioli, L. , & Perfumi, M. ( 25(3), 411–420. [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, L. , & Perfumi, M. ( 25(3), 402–410. [CrossRef]

- Perfumi, M. , & Mattioli, L. (2007). Adaptogenic and central nervous system effects of single doses of 3% rosavin and 1% salidroside Rhodiola rosea L. extract in mice. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 21(1), 37–43. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z. Q. , Zhou, Y., Zeng, Y. S., Li, Y., & Chung, P. (2009). Pretreatment with Rhodiola rosea extract reduces cognitive impairment induced by intracerebroventricular streptozotocin in rats: implication of anti-oxidative and neuroprotective effects. Biomedical and environmental sciences : BES, 22(4), 318–326. [CrossRef]

- Bhakta-Guha D, Efferth, T. (2015). Hormesis: Decoding Two Sides of the Same Coin. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 8(4), 865–883. [CrossRef]

- Szabadi, E. (1977). A model of two functionally antagonistic receptor populations activated by the same agonist. Journal of theoretical biology, 69(1), 101–112. [CrossRef]

- Ratiani, L. , Pachkoria, E., Mamageishvili, N., Shengelia, R., Hovhannisyan, A., & Panossian, A. (2023). Efficacy of Kan Jang® in Patients with Mild COVID-19: A Randomized, Quadruple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 16(9), 1196. [CrossRef]

- Karosanidze, I. , Kiladze, U., Kirtadze, N., Giorgadze, M., Amashukeli, N., Parulava, N., Iluridze, N., Kikabidze, N., Gudavadze, N., Gelashvili, L., Koberidze, V., Gigashvili, E., Jajanidze, N., Latsabidze, N., Mamageishvili, N., Shengelia, R., Hovhannisyan, A., & Panossian, A. (2022). Efficacy of Adaptogens in Patients with Long COVID-19: A Randomized, Quadruple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 15(3), 345. [CrossRef]

- Dye, L.; Billington, J.; Lawton, C.; Boyle, N. A combination of magnesium, B vitamins, green tea and rhodiola attenuates the negative effects of acute psychosocial stress on subjective state in adults. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa067_023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, N. B. , Billington, J. ( 25(9), 1845–1859. [CrossRef]

- Boyle, N. B. , Dye, L. ( 9, 935001. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noah, L. , Morel, V., Bertin, C., Pouteau, E., Macian, N., Dualé, C., Pereira, B., & Pickering, G. (2022). Effect of a Combination of Magnesium, B Vitamins, Rhodiola, and Green Tea (L-Theanine) on Chronically Stressed Healthy Individuals-A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutrients, 14(9), 1863. [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G. , Noah, L., Pereira, B., Goubayon, J., Leray, V., Touron, A., Macian, N., Bernard, L., Dualé, C., Roux, V., & Chassain, C. (2023). Assessing brain function in stressed healthy individuals following the use of a combination of green tea, Rhodiola, magnesium, and B vitamins: an fMRI study. Frontiers in nutrition, 10, 1211321. [CrossRef]

- Cropley, M. , Banks, A. P., & Boyle, J. (2015). The Effects of Rhodiola rosea L. Extract on Anxiety, Stress, Cognition and Other Mood Symptoms. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 29(12), 1934–1939. [CrossRef]

- Schutgens, F. W. , Neogi, P., van Wijk, E. P., van Wijk, R., Wikman, G., & Wiegant, F. A. (2009). The influence of adaptogens on ultraweak biophoton emission: a pilot experiment. Phytotherapy research: PTR, 23(8), 1103–1108. [CrossRef]

- Wing, S. L. , Askew, E. W., Luetkemeier, M. J., Ryujin, D. T., Kamimori, G. H., & Grissom, C. K. (2003). Lack of effect of Rhodiola or oxygenated water supplementation on hypoxemia and oxidative stress. Wilderness & environmental medicine, 14(1), 9–16. [CrossRef]

- De Bock, K. , Eijnde, B. ( 14(3), 298–307. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abidov, M. , Grachev, S., Seifulla, R. D., & Ziegenfuss, T. N. (2004). Extract of Rhodiola rosea radix reduces the level of C-reactive protein and creatinine kinase in the blood. Bulletin of experimental biology and medicine, 138(1), 63–64. [CrossRef]

- Walker, T. B. , Altobelli, S. A., Caprihan, A., & Robergs, R. A. (2007). Failure of Rhodiola rosea to alter skeletal muscle phosphate kinetics in trained men. Metabolism: clinical and experimental, 56(8), 1111–1117. [CrossRef]

- Shevtsov, V. A. , Zholus, B. I., Shervarly, V. I., Vol'skij, V. B., Korovin, Y. P., Khristich, M. P., Roslyakova, N. A., & Wikman, G. (2003). A randomized trial of two different doses of a SHR-5 Rhodiola rosea extract versus placebo and control of capacity for mental work. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 10(2-3), 95–105. [CrossRef]

- Fintelmann, V. , & Gruenwald, J. ( 24(4), 929–939. [CrossRef]

- Bystritsky, A. , Kerwin, L. D. ( 14(2), 175–180. [CrossRef]

- Yu HL, Zhang PP, Zhang C, Zhang X, Li ZZ, Li WQ, Fu AS. Effects of rhodiola rosea on oxidative stress and negative emotional states in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2019 Oct;33(10):954-957. Chinese. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarpanska-Stejnborn, A. , Pilaczynska-Szczesniak, L., Basta, P., & Deskur-Smielecka, E. (2009). The influence of supplementation with Rhodiola rosea L. extract on selected redox parameters in professional rowers. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 19(2), 186–199. [CrossRef]

- Parisi, A. , Tranchita, E., Duranti, G., Ciminelli, E., Quaranta, F., Ceci, R., Cerulli, C., Borrione, P., & Sabatini, S. (2010). Effects of chronic Rhodiola Rosea supplementation on sport performance and antioxidant capacity in trained male: preliminary results. The Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 50(1), 57–63.

- Goyvaerts, B. , & Bruhn, S. (2012). Rhodiola rosea special extract SHR-5 in burnout and fatigue syndrome. Erfahrungsheilkunde, 61, 79–83. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D. , Heufelder, A., & Zimmermann, A. (2012). Therapeutic effects and safety of Rhodiola rosea extract WS® 1375 in subjects with life-stress symptoms--results of an open-label study. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 26(8), 1220–1225. [CrossRef]

- Noreen, E. E. , Buckley, J. J. ( 27(3), 839–847. [CrossRef]

- Mao, J. J. , Li, Q. S., Soeller, I., Xie, S. X., & Amsterdam, J. D. (2014). Rhodiola rosea therapy for major depressive disorder: a study protocol for a randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled trial. Journal of clinical trials, 4, 170. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M. J. , & Clarke, N. D. (2014). The Effect of Acute Rhodiola rosea Ingestion on Exercise Heart Rate, Substrate Utilisation, Mood State, and Perceptions of Exertion, Arousal, and Pleasure/Displeasure in Active Men. Journal of sports medicine (Hindawi Publishing Corporation), 2014, 563043. [CrossRef]

- Punja, S. , Shamseer, L., Olson, K., & Vohra, S. (2014). Rhodiola rosea for mental and physical fatigue in nursing students: a randomized controlled trial. PloS one, 9(9), e108416. [CrossRef]

- Shanely, R. A. , Nieman, D. M. ( 39, 204–210. [CrossRef]

- Mao, J. J. , Xie, S. X., Zee, J., Soeller, I., Li, Q. S., Rockwell, K., & Amsterdam, J. D. (2015). Rhodiola rosea versus sertraline for major depressive disorder: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 22(3), 394–399. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M. , Henson, D. A. ( 2, 24. [CrossRef]

- Thu, O. K. , Spigset, O. ( 72(3), 295–300. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasper, S. , & Dienel, A. (2017). Multicenter, open-label, exploratory clinical trial with Rhodiola rosea extract in patients suffering from burnout symptoms. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 13, 889–898. [CrossRef]

- Lekomtseva, Y. , Zhukova, I., & Wacker, A. (2017). Rhodiola rosea in Subjects with Prolonged or Chronic Fatigue Symptoms: Results of an Open-Label Clinical Trial. Complementary medicine research, 24(1), 46–52. [CrossRef]

- Concerto, C. , Infortuna, C., Muscatello, M. R. A., Bruno, A., Zoccali, R., Chusid, E., Aguglia, E., & Battaglia, F. (2018). Exploring the effect of adaptogenic Rhodiola Rosea extract on neuroplasticity in humans. Complementary therapies in medicine, 41, 141–146. [CrossRef]

- Jówko, E. , Sadowski, J. ( 7(4), 473–480. [CrossRef]

- Timpmann, S. , Hackney, A. C., Tamm, M., Kreegipuu, K., Unt, E., & Ööpik, V. (2018). Influence of Rhodiola rosea on the heat acclimation process in young healthy men. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme, 43(1), 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Ballmann, C. G. , Maze, S. B., Wells, A. C., Marshall, M. M., & Rogers, R. R. (2019). Effects of short-term Rhodiola Rosea (Golden Root Extract) supplementation on anaerobic exercise performance. Journal of sports sciences, 37(9), 998–1003. [CrossRef]

- Gao, L. , Wu, C., Liao, Y., & Wang, J. (2020). Antidepressants effects of Rhodiola capsule combined with sertraline for major depressive disorder: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Journal of affective disorders, 265, 99–103. [CrossRef]

- Koop, T. , Dienel, A., Heldmann, M., & Münte, T. F. (2020). Effects of a Rhodiola rosea extract on mental resource allocation and attention: An event-related potential dual task study. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 34(12), 3287–3297. [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. D. , Langley, H. N., Roberson, C. C., Rogers, R. R., & Ballmann, C. G. (2021). Effects of Short-Term Golden Root Extract (Rhodiola rosea) Supplementation on Resistance Exercise Performance. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(13), 6953. [CrossRef]

- Hung, S. K. , Perry, R., & Ernst, E. (2011). The effectiveness and efficacy of Rhodiola rosea L.: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Phytomedicine : international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology, 18(4), 235–244. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L. , Qin, Y., Wang, Q., Zhang, L., Liu, Y., Wang, T., Huang, L., Wu, L., & Xiong, H. (2014). The efficacy and safety of Chinese herbal medicine, Rhodiola formulation in treating ischemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complementary therapies in medicine, 22(4), 814–825. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, C. , Boyd, C., & Deuster, P. A. (2021). Dietary Supplement Ingredients for Optimizing Cognitive Performance Among Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.), 27(11), 940–958. [CrossRef]

- Li, X. , Chen, W., Xu, Y., Liang, Z., Hu, H., Wang, S., & Wang, Y. (2021). Quality Evaluation of Randomized Controlled Trials of Rhodiola Species: A Systematic Review. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM, 2021, 9989546. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. , Deng, B., Xu, L., Liu, H., Song, Y., & Lin, F. (2022). Effects of Rhodiola Rosea Supplementation on Exercise and Sport: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in nutrition, 9, 856287. [CrossRef]

- Lu Y, Deng B, Xu L, Liu H, Song Y, Lin F. Corrigendum: Effects of Rhodiola Rosea Supplementation on Exercise and Sport: A Systematic Review. Front Nutr. 2022 Jun 20;9:928909. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H. , Lei, T., Su, X., Zhang, L., Feng, Z., Dong, M., Hou, Z., Guo, H., & Liu, J. (2023). Efficacy and safety of three species of Rhodiola L. in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in pharmacology, 14, 1139239. [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Barrio, P. M. , Noreen, E. E., Gilsanz-Estebaranz, L., Lorenzo-Calvo, J., Martínez-Ferrán, M., & Pareja-Galeano, H. (2023). Rhodiola rosea supplementation on sports performance: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 37(10), 4414–4428. [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Barrio, P. M. , Noreen, E. E., Gilsanz-Estebaranz, L., Lorenzo-Calvo, J., Martínez-Ferrán, M., & Pareja-Galeano, H. (2023). Rhodiola rosea supplementation on sports performance: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Phytotherapy research : PTR, 37(10), 4414–4428. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M. , Lankatillake, C., Dias, D. A., Docea, A. O., Mahomoodally, M. F., Lobine, D., Chazot, P. L., Kurt, B., Tumer, T. B., Moreira, A. C., Sharopov, F., Martorell, M., Martins, N., Cho, W. C., Calina, D., & Sharifi-Rad, J. (2020). Impact of Natural Compounds on Neurodegenerative Disorders: From Preclinical to Pharmacotherapeutics. Journal of clinical medicine, 9(4), 1061. [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V. L. , Forouzanfar, M. H., Krishnamurthi, R., Mensah, G. A., Connor, M., Bennett, D. A., Moran, A. E., Sacco, R. L., Anderson, L., Truelsen, T., O'Donnell, M., Venketasubramanian, N., Barker-Collo, S., Lawes, C. M., Wang, W., Shinohara, Y., Witt, E., Ezzati, M., Naghavi, M., Murray, C., … Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2010 (GBD 2010) and the GBD Stroke Experts Group (2014). Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990-2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (London, England), 383(9913), 245–254. [CrossRef]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause of Death 2018–2022 on CDC WONDER Database. Accessed , 2024. (https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/data-research/facts-stats/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/facts.htm ). 3 May.

- Alghamdi, I. , Ariti, C., Williams, A., Wood, E., & Hewitt, J. (2021). Prevalence of fatigue after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European stroke journal, 6(4), 319–332. [CrossRef]

- Zedlitz, A. M. , Rietveld, T. C., Geurts, A. C., & Fasotti, L. (2012). Cognitive and graded activity training can alleviate persistent fatigue after stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke, 43(4), 1046–1051. [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C. N. , Gupta, S. K., Perretti, M., Godson, C., Brennan, E., Li, Y., Soehnlein, O., Shimizu, T., Werz, O., Chiurchiù, V., Azzi, A., Dubourdeau, M., Gupta, S. S., Schopohl, P., Hoch, M., Gjorgevikj, D., Khan, F. M., Brauer, D., Tripathi, A., Cesnulevicius, K., … Wolkenhauer, O. (2020). The Atlas of Inflammation Resolution (AIR). Molecular aspects of medicine, 74, 100894. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J. , Xie, D., Bhatia, T. N., Leak, R. K., Hu, X., & Jiang, X. (2021). Microglial/Macrophage polarization and function in brain injury and repair after stroke. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics, 27(5), 515–527. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. , Xuan, W., Zhu, Z. Y., Li, Y., Zhu, H., Zhu, L., Fu, D. Y., Yang, L. Q., Li, P. Y., & Yu, W. F. (2018). The evolving role of neuro-immune interaction in brain repair after cerebral ischemic stroke. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics, 24(12), 1100–1114. [CrossRef]

- Immordino-Yang MH, Antonio D. We feel, therefore we learn: the relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind Brain Educ. 2007;1:3–10.

- Salmeron KE, Maniskas ME, Edwards DN, Wong R, Rajkovic I, Trout A, et al. Interleukin 1 alpha administration is neuroprotective and neuro-restorative following experimental ischemic stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16(1):222. [CrossRef]

- Kiyota T, Ingraham KL, Swan RJ, Jacobsen MT, Andrews SJ, Ikezu T. AAV serotype 2/1-mediated gene delivery of anti-inflammatory interleukin-10 enhances neurogenesis and cognitive function in APPPS1 mice. Gene Ther. 2012;19:724–33. [CrossRef]

- Paro, M. R. , Chakraborty, A. R., Angelo, S., Nambiar, S., Bulsara, K. R., & Verma, R. (2022). Molecular mediators of angiogenesis and neurogenesis after ischemic stroke. Reviews in the neurosciences, 34(4), 425–442. [CrossRef]

- An, C. , Shi, Y., Li, P., Hu, X., Gan, Y., Stetler, R. A., Leak, R. K., Gao, Y., Sun, B. L., Zheng, P., & Chen, J. (2014). Molecular dialogs between the ischemic brain and the peripheral immune system: dualistic roles in injury and repair. Progress in neurobiology, 115, 6–24. [CrossRef]

- Ludhiadch, A. , Sharma, R., Muriki, A., & Munshi, A. (2022). Role of Calcium Homeostasis in Ischemic Stroke: A Review. CNS & neurological disorders drug targets, 21(1), 52–61. [CrossRef]

- Darsalia, V. , Heldmann, U., Lindvall, O., & Kokaia, Z. (2005). Stroke-induced neurogenesis in aged brain. Stroke, 36(8), 1790–1795. [CrossRef]

- Nygren J, Wieloch T, Pesic J, Brundin P, Deierborg T. Enriched environment attenuates cell genesis in subventricular zone after focal ischemia in mice and decreases migration of newborn cells to the striatum. Stroke. 2006;37:2824–9.

- Jin, K. , Wang, X., Xie, L., Mao, X. O., Zhu, W., Wang, Y., Shen, J., Mao, Y., Banwait, S., & Greenberg, D. A. (2006). Evidence for stroke-induced neurogenesis in the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(35), 13198–13202. [CrossRef]

- Thored P, Arvidsson A, Cacci E, Ahlenius H, Kallur T, Darsalia V, et al. Persistent production of neurons from adult brain stem cells during recovery after stroke. Stem Cells. 2006;24(3):739–47. [CrossRef]

- Zhang RL, Zhang ZG, Zhang L, Chopp M. Proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells in the cortex and the subventricular zone in the adult rat after focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2001;105:33–41. [CrossRef]

- Tonchev, A. B. , Yamashima, T. ( 23(2), 292–301. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, K. , Minami, M. A. ( 98(8), 4710–4715. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A. A. , Amruta, N., Pinteaux, E., & Bix, G. J. (2021). Neurogenesis After Stroke: A Therapeutic Perspective. Translational stroke research, 12(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Louissaint, A. , Jr, Rao, S. A. ( 34(6), 945–960. [CrossRef]

- Moon, S. , Chang, M. K. ( 22(16), 8543. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn HG, Toda T, Gage FH. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis: a coming-of-age story. J Neurosci. 2018;38:10401–10.