1. Introduction

With an estimated yearly cost of over 750 billion dollars, hearing loss (HL) is the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide. It affects society and the economy and causes social isolation, loneliness, stigma, lower standard of living and a reduction in personal productivity, endangering family prosperity and job stability [

1,

2]. Hearing loss has been associated with the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB), primarily due to the ototoxic effects of the medications used. Studies show that aminoglycosides (AGs) such as kanamycin and amikacin are among the most ototoxic drugs used in DR-TB regimens, causing irreversible damage to the inner ear’s sensory cells, particularly with prolonged exposure and higher doses [

3]. This ototoxic effect is dose-dependent, with cumulative exposure increasing the risk of permanent hearing impairment [

4]. Studies indicate that the prevalence of hearing loss among patients receiving these treatments can be as high as 41% to 50% [

5,

6,

7]. A study in Nigeria found that 89.5% of patients treated for drug-resistant tuberculosis experienced hearing impairment after three months of treatment, with a significant increase from a baseline prevalence of 73.7% [

8]. Additionally, second-line drugs, including linezolid, although less ototoxic, have also been associated with auditory side effects, indicating a need for comprehensive ototoxicity assessment in DR-TB patients. The mechanism of ototoxicity is linked to the damage these drugs inflict on the sensory hair cells in the cochlea, particularly affecting high-frequency hearing first, which can progress to lower frequencies over time [

9,

10]. Research comparing the effects of different treatment regimens has shown that patients on kanamycin (G-KCIN) experience significant sensorineural HL, with over 73% showing worsening hearing thresholds [

11]. In contrast, patients treated with bedaquiline (G-BDQ), a newer drug, did not demonstrate statistically significant changes in hearing function, with only 7% reporting tinnitus. This suggests that bedaquiline may be a safer alternative for preserving hearing function during DR-TB treatment [

11].

Ototoxicity is the term used to describe the functional damage of inner hair cells and nerves brought on by particular drugs and chemicals [

2]. It is one of the most commonly reported adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in DR-TB management, with an increased risk in patients taking HIV treatment, thereby affecting the quality of life, treatment adherence, and hence treatment outcomes [

12,

13,

14]. The cumulative dose of aminoglycosides has also been associated with an increased risk of HL, indicating that dose management is critical in preventing ototoxicity. Early detection through audiometry assessments and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) may prevent the risk of permanent damage [

15]. Khosa-Shangese and Stirk, [

16] identified a gap concerning the audiometry assessments and management of ototoxicity in cases where it has been identified. The availability of evidence-based management protocols was lacking. A current study by Stevenson et al. [

17] revealed similar findings of the need to reassess current guidelines and protocols to be more appropriate for community-based ototoxicity programs.

Following the reported cases of high prevalence of ototoxicity associated with aminoglycosides (AGs), the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended the replacement of AGs with bedaquiline (G-BDG) and linezolid (Lzd) -based regimens. These newer DR-TB drugs are known to be less associated with HL [

18]. Given the risks associated with AG treatment, recent studies advocate regular audiometric assessments for DR-TB patients throughout their treatment course to detect early signs of HL and allow for timely intervention. Monitoring can help detect HL early, allowing for timely adjustments to treatment regimens to mitigate further auditory damage [

15,

19,

20]. Implementing alternative treatment options, such as newer, less ototoxic drugs like bedaquiline and delamanid, may also help mitigate the risk of HL while maintaining treatment efficacy [

21]. Early results suggest that these medications may be safe alternatives, particularly for high-risk patients, although their long-term effectiveness and safety are still under evaluation. The primary objectives of this study are to identify significant risk factors for hearing loss (HL) in this population and to determine the frequency and severity of hearing loss in patients receiving treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB). The specific aims of the study include examining the impact of demographic factors such as age and gender on hearing outcomes, assessing the influence of lifestyle factors like smoking, alcohol consumption, and occupational noise exposure on hearing impairment, and evaluating the effects of clinical variables, including DR-TB classification (e.g., multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR)), treatment outcomes, and comorbid conditions (e.g., HIV, hypertension, and diabetes). Furthermore, this study seeks to explore how the combination of these risk factors may heighten the susceptibility to hearing loss during DR-TB therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

The research investigation evaluated auditory outcomes in individuals receiving drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) treatment to determine the prevalence of auditory deficits, associated risk factors, and concurrent comorbidities from January 2018 to December 2020. This investigation was carried out across four tuberculosis (TB) clinics and a one-referral hospital in the Oliver Reginald Tambo District Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. These selected clinics were identified as crucial primary care establishments for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis (TB), with a particular emphasis on hearing loss in drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) patients in rural and underprivileged communities experiencing a significant disease burden. The referral hospital was incorporated into the research due to its specialized function in managing intricate DR-TB cases, which often involve severe comorbid conditions and necessitate the application of advanced diagnostic methodologies. The research methodology encompasses data gathering, selection of variables, and statistical analysis aimed at thoroughly examining the risk factors for hearing impairment among patients with DR-TB, emphasizing the impact of age, treatment outcomes, comorbidities, and lifestyle determinants on auditory health.

2.1. Study Population and Data Collection

Patients diagnosed with DR-TB and treated at designated healthcare facilities over a specified study period were included. Inclusion criteria required that patients had completed both DR-TB treatment and audiometric assessments before, during, or after treatment. Patients with incomplete audiometric records were excluded. Patient demographic and clinical data were collected from electronic health records (EHRs) including age, gender, DR-TB classification (e.g., MDR, XDR), treatment outcome, comorbidities (e.g., HIV, hypertension, diabetes), and lifestyle factors such as smoking and alcohol use.

2.2. Operational Definition

The following definitions were adapted from Faye et al. [

22]:

Rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (RR-TB): TB resistant to rifampicin but susceptible to isoniazid.

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB): TB resistant to both isoniazid and rifampin.

Pre-extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (pre-XDR-TB): A type of MDR TB resistant to isoniazid, rifampin, and either a fluoroquinolone or a second-line injectable.

Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB): type of MDR TB resistant to isoniazid, rifampin, fluoroquinolone, and either a second-line injectable or additional drugs like bedaquiline or linezolid.

Isoniazid resistant tuberculosis (INH-R-TB): resistant to isoniazid but susceptible to rifampicin.

2.3. Audiometric Testing

Audiometric assessments were performed by a clinician using standardized hearing tests, measuring hearing thresholds across a range of frequencies. Testing was conducted at baseline (before starting DR-TB treatment) and post-treatment to monitor changes in hearing function. Based on audiometric results, patients were categorized as having either positive results (indicating hearing impairment) or negative results (indicating no hearing impairment).

2.4. Variable Selection and Interaction Analysis

Key variables selected for analysis included age, gender, DR-TB type (e.g., RR, MDR, pre-XDR), treatment outcome, comorbidities (HIV, hypertension, diabetes), and lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol use). These were identified as potential risk factors influencing hearing outcomes. The study incorporated interaction terms in statistical models to explore the combined effect of variables on hearing outcomes. Specific interactions analyzed included social history with patient category, comorbidities with social history, and patient category with HIV status.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive Statistics: Frequencies, proportions, and means were calculated for demographic and clinical characteristics, with audiometry results summarized by age group, gender, DR-TB type, and comorbidity status. A chi-square test of independence was used to determine the association between treatment outcomes and audiometry results. The significance threshold was set at p < 0.05. Logistic regression was conducted to identify factors associated with hearing impairment, adjusting for covariates and including interaction terms. A decision tree model was developed to identify key variables and decision paths predicting positive audiometry results. Gini index values were used to assess node purity and guide variable selection in the tree model. Random Forest Variable importance was used to assess the relative importance of predictors, ranking variables by their influence on hearing outcomes.

2.7. Data Visualization and Model Performance

Gini values across decision tree levels and variable importance rankings from the Random Forest model were visualized using scatter and bar plots. Audiometry results were also stratified by treatment outcomes and DR-TB types to identify trends. Model performance was evaluated using precision, recall, and ROC-AUC scores. Confusion matrices were constructed to examine true and false positive rates, informing the model’s sensitivity and specificity in predicting hearing impairment.

3. Results

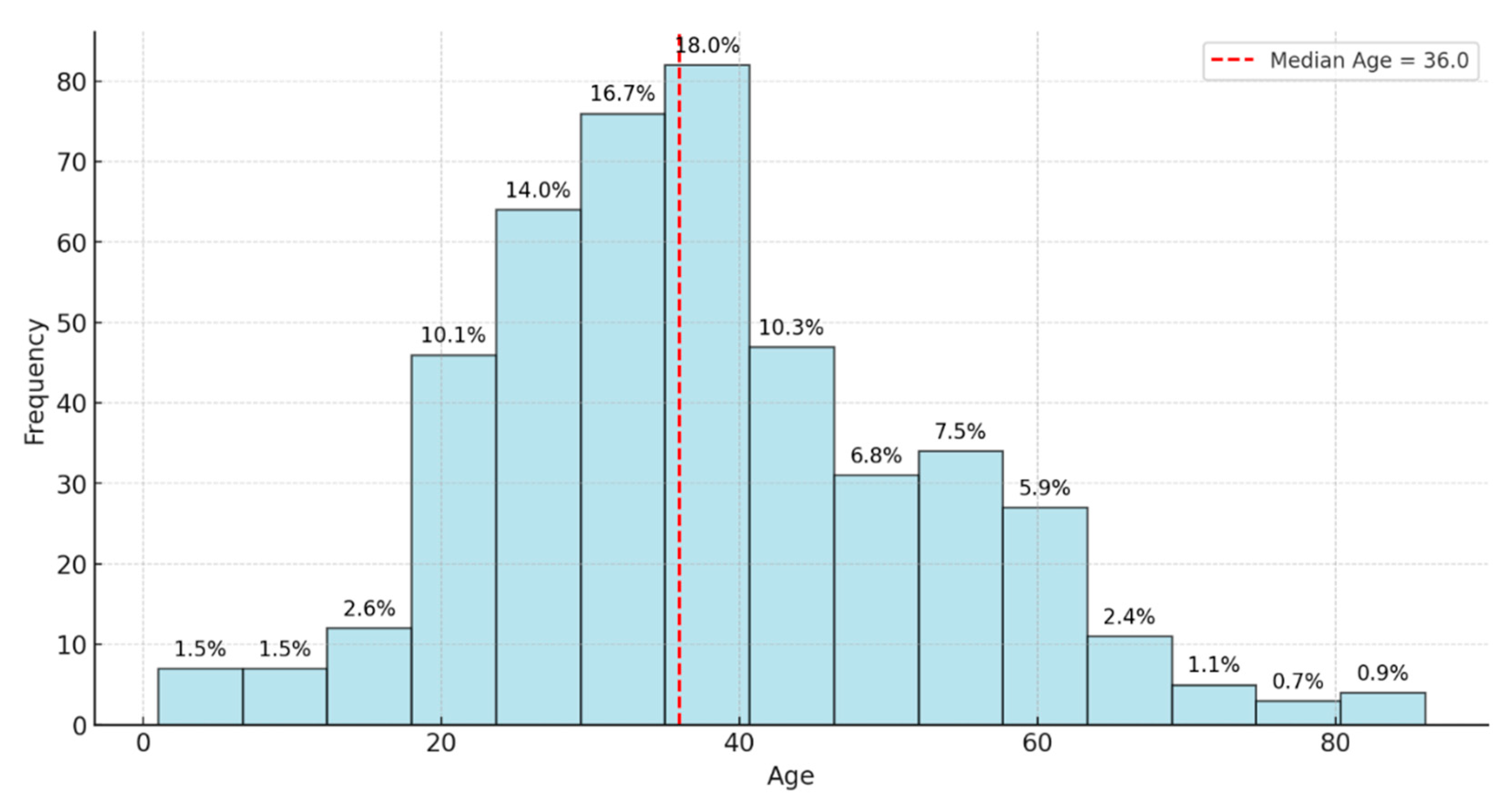

This study reviewed records of 456 patients with DR-TB. Among these, 18 were excluded because of incomplete data on audiometry testing. Thus, 438 participants were selected and retained for the final analysis. Of the 438 participants whose records were reviewed, the prevalence of Hearing Loss (HL) was 37.2%. The study participant’s mean age (±SD) was 37.8 (±14.8) years; the median age was 36 years, with ages ranging between 1 and 86 years (

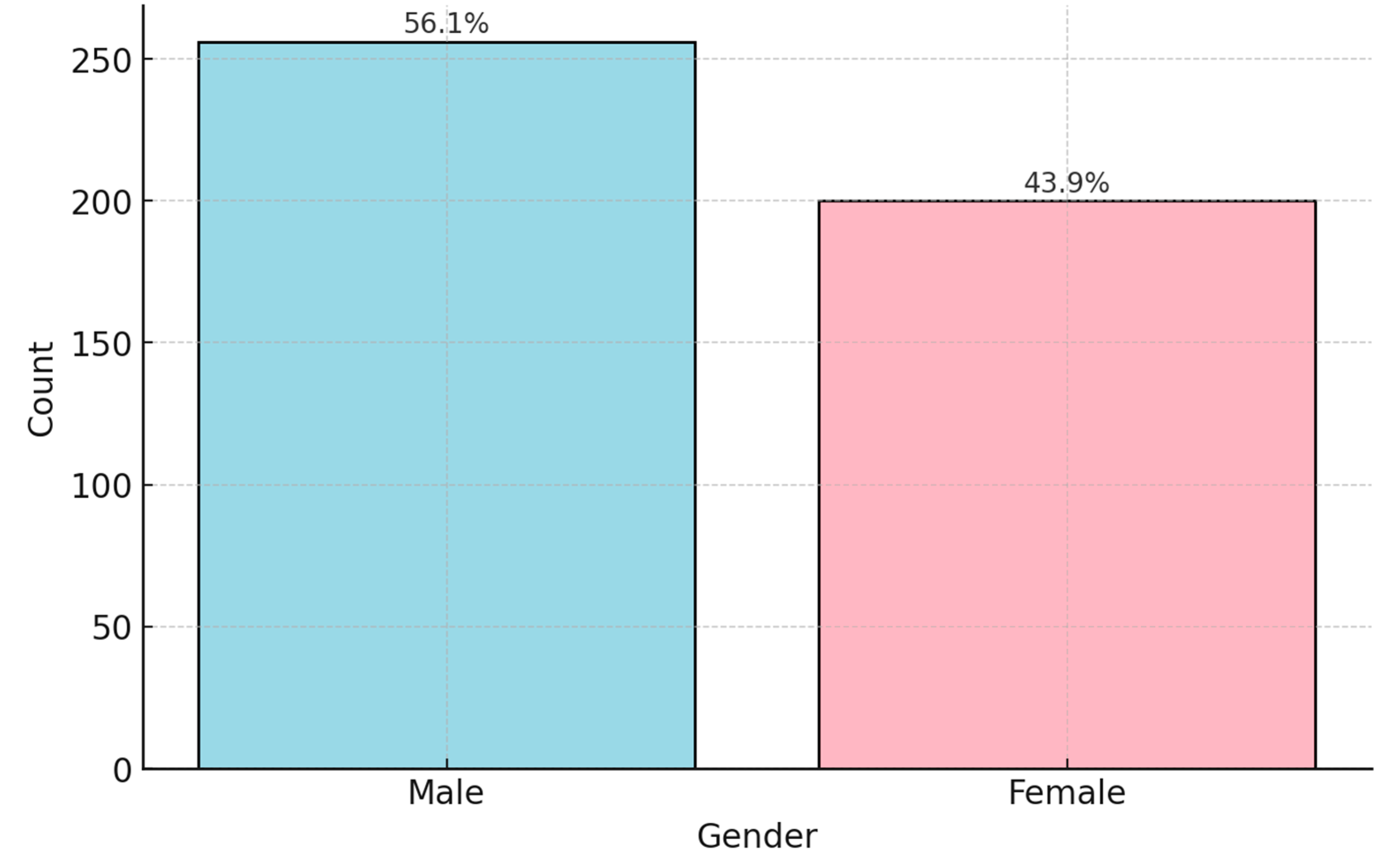

Figure 1). Almost half of the patients were aged between 30 and 49 years (48.2%). Of the participants positive for HL,56.1% were males and 43.9% were females (

Figure 2).

Ages were grouped into age bands for analysis. Analyzing audiometric test results across different age bands reveals distinct trends in hearing health. In the 0-29 age group, out of 141 individuals tested, 53 (approximately 37.6%) showed positive results, while 88 (approximately 62.4%) were negative, indicating that most in this group do not face significant hearing issues. Similarly, the 30-49 age band, which included 211 tested individuals, had 79 positive results (about 37.4%) and 132 negative results (62.6%), demonstrating a comparable distribution where most do not exhibit audiometric concerns, but a notable minority does. This suggests that hearing issues become noticeable but remain consistent with the younger cohort, signaling the potential onset of hearing challenges. In the 50-69 age group, the trend shifts slightly; among 76 tested individuals, 25 (32.9%) had positive results, and 51 (67.1%) were negative. This shows that while the majority still do not have hearing problems, the proportion of individuals with concerns remains significant, pointing toward an age-related increase in hearing concerns. The most notable shift occurs in the 70+ age band, with only 10 individuals tested but yielding 6 positive results (60.0%) and 4 negative results (40.0%) (

Table 1). The most dramatic shift is seen in the 70+ age band, where out of 10 tests, 6 individuals (60.0%) tested positive. This sharp rise underscores the correlation between advancing age and the prevalence of hearing issues, emphasizing the importance of proactive hearing health measures and frequent assessments in this older population. Overall, these results emphasize a gradual increase in positive audiometric outcomes with age, particularly pronounced in the oldest group.

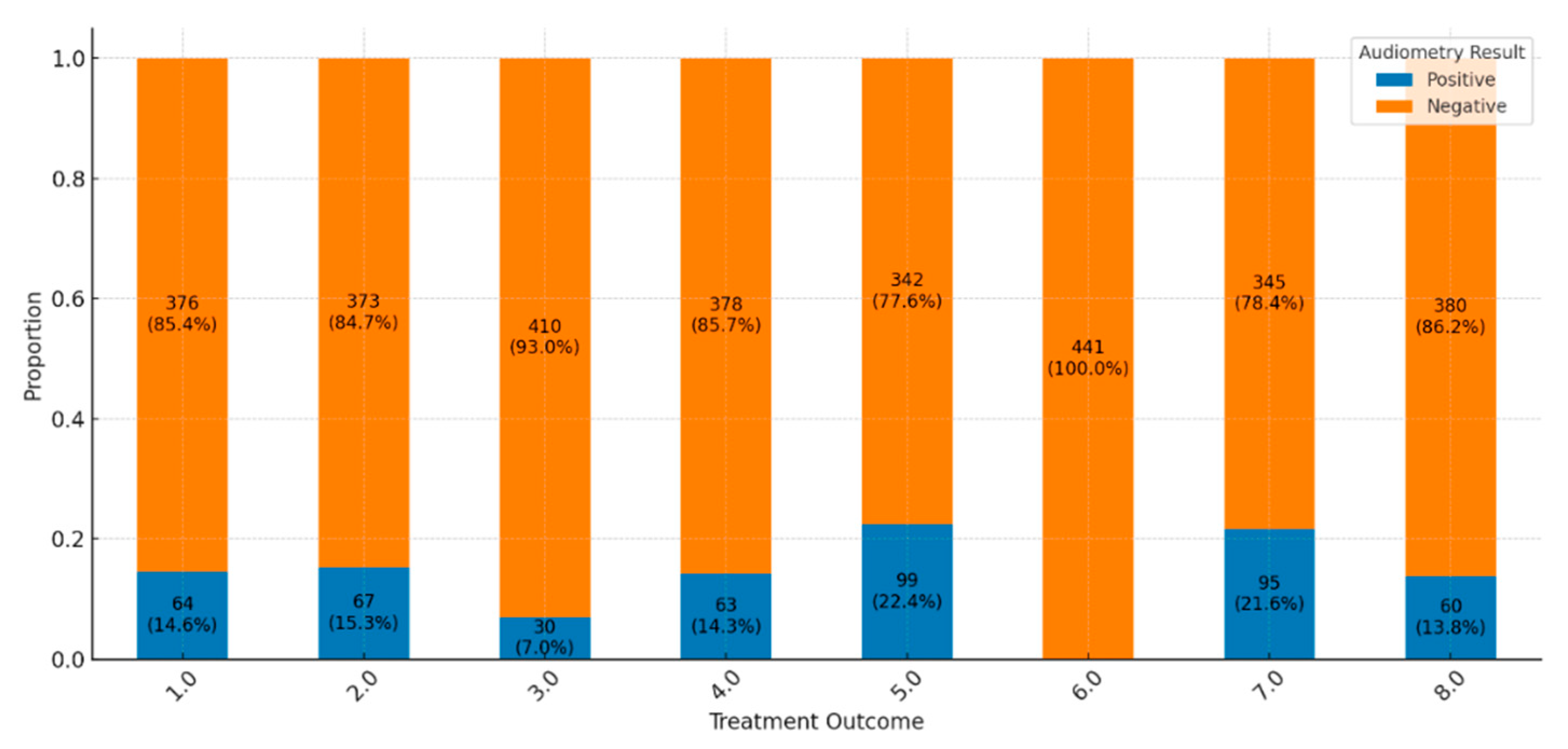

Across the spectrum of treatment outcomes, the majority of patients exhibit negative audiometry results, suggesting a low prevalence of hearing impairment overall. Favorable outcomes, such as “Cured” and “Treatment Completed,” show particularly high proportions of negative results (85.4% and 84.7%, respectively), indicating that HL is generally uncommon among these groups (

Figure 3). Positive audiometry findings, indicating hearing impairment, are present but represent a minority across most outcomes. For instance, only 14.6% of cases in the “Cured” group display positive results, pointing to a small subset of patients who experience hearing impairment post-treatment. There is notable variability in results based on treatment outcomes. Groups like “LTFU” (Lost to Follow-Up), “Moved Out,” and “Transferred Out” show lower frequencies of positive results, such as a 7% positive rate in “Moved Out,” which may reflect reduced data collection or follow-up in these cases due to non-completion or treatment interruption. More severe outcomes, including “Treatment Failed” and “Died,” also show positive results, though not as prominently, possibly because other health complications are more immediate in these cases. Patients “Still on Treatment” primarily exhibit negative results, with 78.4% showing no signs of hearing impairment. This outcome might indicate that ongoing treatment has not yet led to significant audiometric issues, although hearing outcomes for this group may evolve by the end of their treatment. This distribution of results highlights a general trend of minimal hearing impairment among patients with favorable treatment outcomes, while specific groups with incomplete treatment show variability that could be influenced by factors such as data collection limitations or other health priorities.

The chi-square test of independence was used to determine if there is a statistically significant association between two categorical variables: treatment outcome and audiometry result (positive or negative). The results (chi-square statistics = 19.26, degrees of freedom = 7, p-value = 0.0074) indicate a statistically significant association between treatment outcomes and audiometry results. The p-value, 0.0074, is below the common significance threshold of 0.05, indicating that the distribution of hearing impairment (positive audiometry results) and no impairment (negative results) depends on treatment outcomes. This finding confirms that different treatment outcomes are meaningfully related to hearing status, suggesting that certain treatment results may be associated with a higher or lower prevalence of hearing impairment.

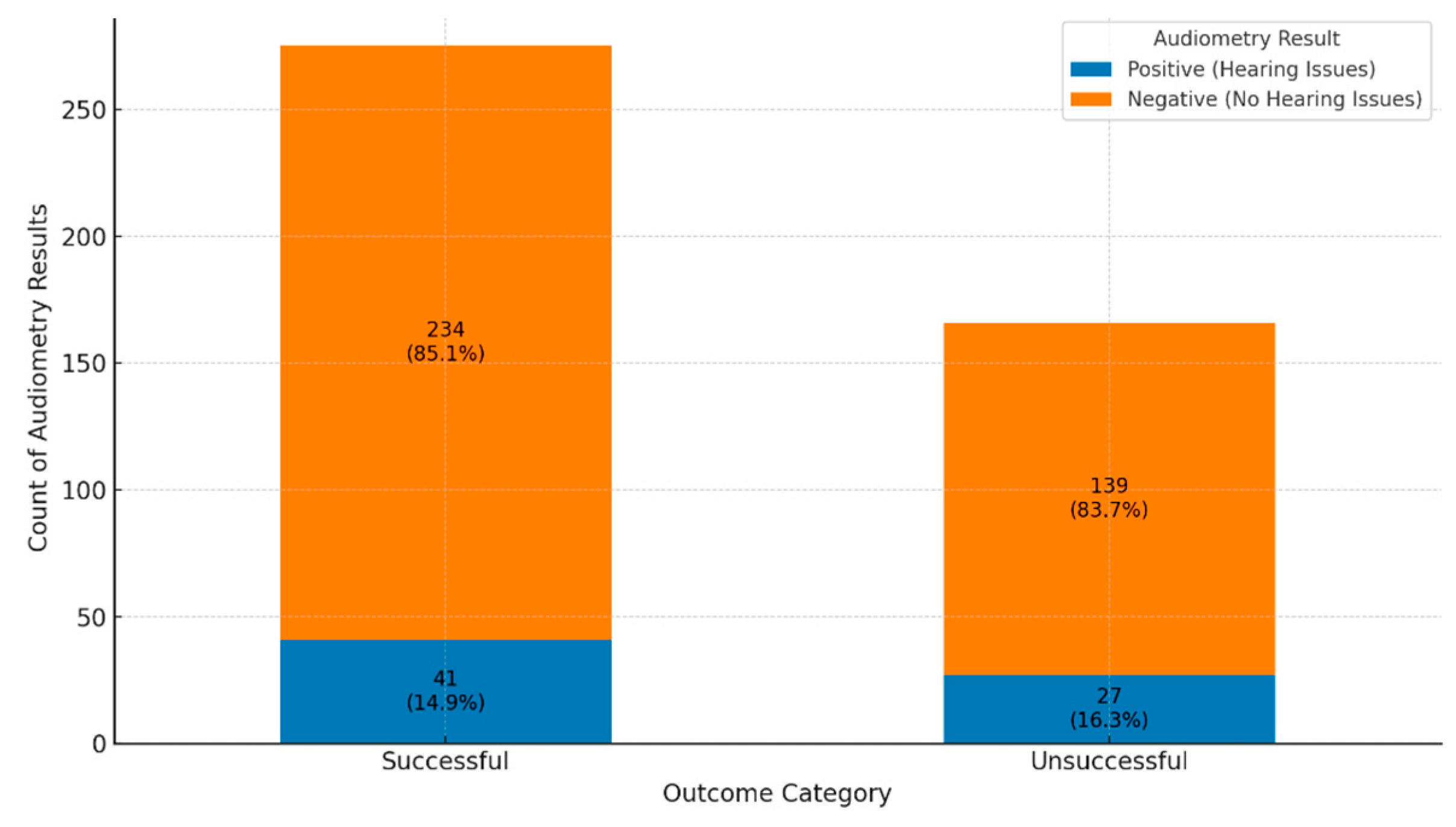

A comparison of audiometry assessment in successful versus unsuccessful treatment outcomes shows no hearing impairment in 85.1% compared to 83.7% respectively (

Figure 4). The proportional analysis highlights that while hearing issues are not the majority outc ome across all treatment groups, they appear more frequently in unsuccessful outcomes than successful ones. This suggests a potential link between unsuccessful treatment and an increased risk of audiometric issues, emphasizing the importance of comprehensive care and monitoring in these patients.

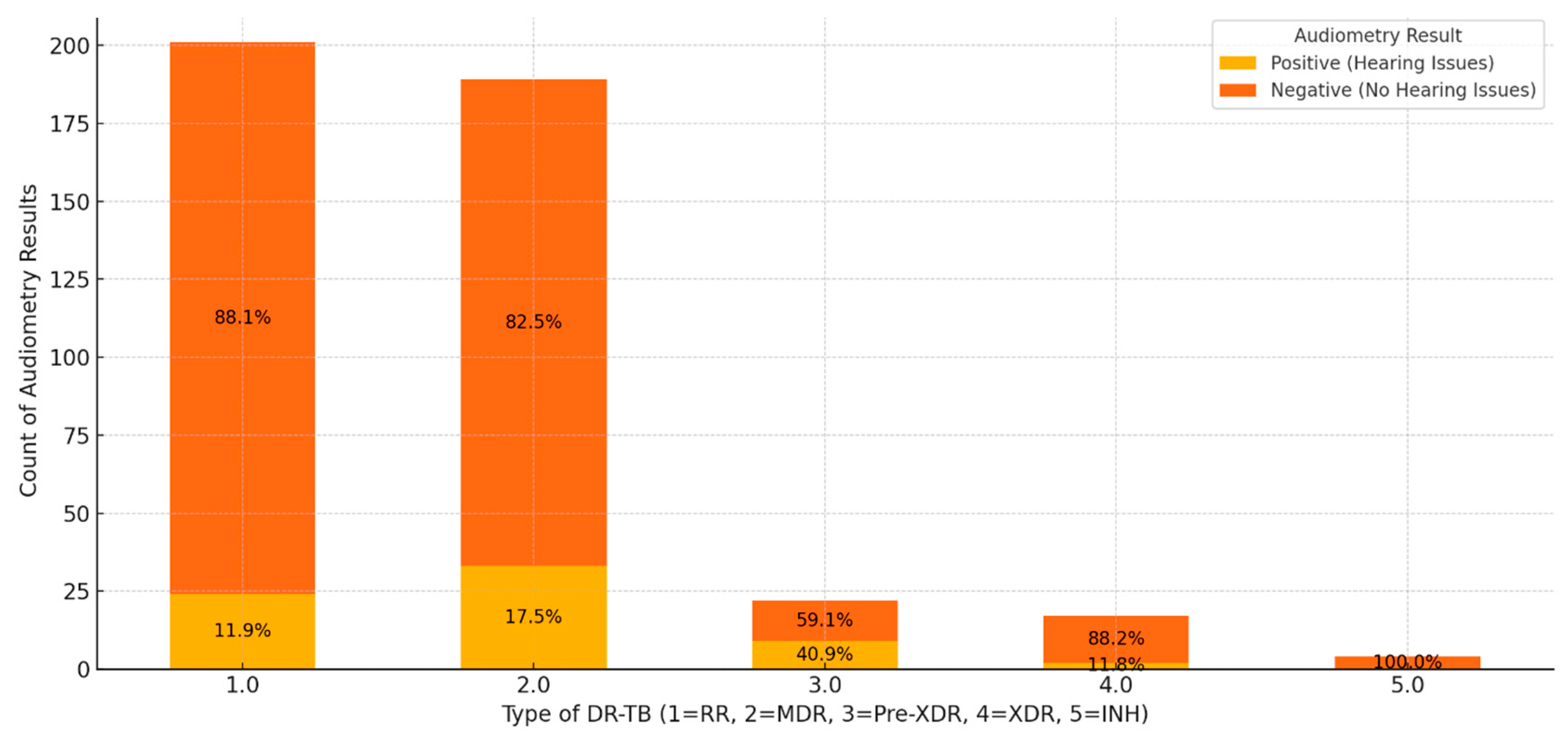

The combined results of audiometry assessments across different types of DR-TB highlight distinct trends in hearing outcomes. Among patients with RR-TB, 88.1% had negative audiometry results, suggesting that hearing issues are relatively rare in this group, with only 11.9% showing positive results (

Figure 5). This indicates that while HL is present, it is not prevalent, though monitoring remains important. Patients with MDR-TB exhibited a higher proportion of positive results at 17.5%, with 82.5% showing no hearing issues, implying an increased risk of hearing impairment potentially linked to treatment intensity or disease impact. In pre-XDR cases, 59.1% of patients had negative results, while 40.9% showed positive results, signifying a substantial risk of HL in nearly half of the patients. This suggests that intensive monitoring and preventive measures are crucial for these patients. XDR-TB cases showed an 88.2% rate of negative results and an 11.8% rate of positive results, similar to RR-TB cases, indicating that while HL exists, it is not as pronounced. Notably, in INH-R-TB, all patients showed negative results, suggesting that this type poses minimal risk to hearing, possibly due to the nature of the resistance or fewer reported cases.

These findings imply that MDR and pre-XDR groups warrant close monitoring for HL during treatment, as these types exhibit higher rates of positive audiometry results. The substantial portion of positive results in pre-XDR patients highlights the need for early hearing assessments and potential treatment adjustments to minimize ototoxic effects. Conversely, RR- and INH-TB patients may find reassurance in the lower prevalence or absence of hearing issues. Overall, negative audiometry results are predominant across most DR-TB types, indicating that significant hearing issues are uncommon. However, special attention should be given to patients with MDR and pre-XDR TB to mitigate the risk of hearing impairment through personalized observation and treatment strategies.

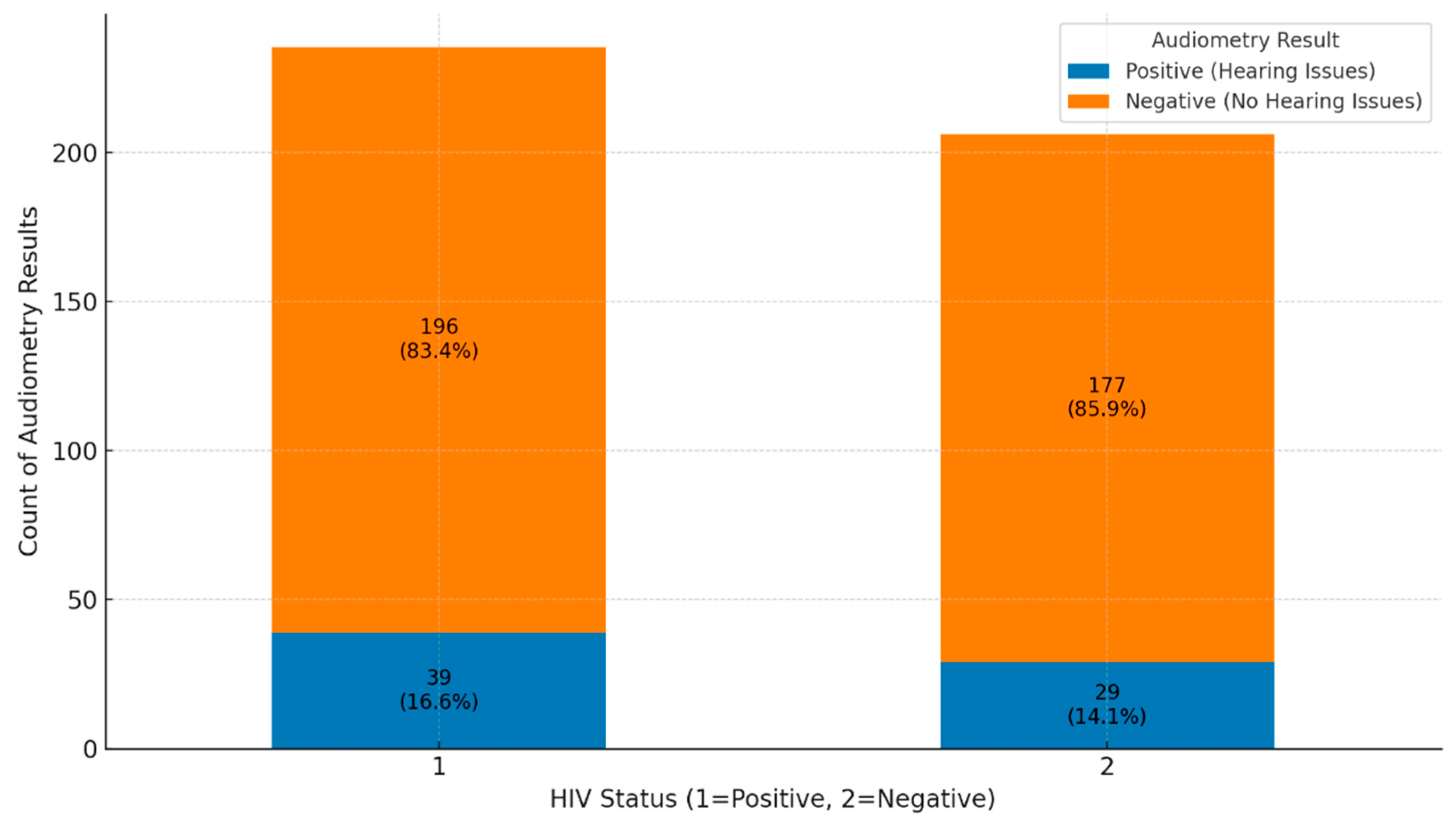

The analysis of audiometry results for HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups reveals important findings regarding hearing health. In the HIV-positive group, 196 out of 235 individuals (83.4%) had negative audiometry results, indicating no significant hearing issues, while 39 individuals (16.6%) had positive results, showing some level of hearing impairment (

Figure 6). This suggests that while most HIV-positive individuals do not experience hearing problems, there is a notable portion that does. In the HIV-negative group, 177 out of 206 individuals (85.9%) also had negative results, with 29 individuals (14.1%) showing positive results. This indicates a similar trend where most HIV-negative individuals do not face hearing issues, although the percentage of HL is slightly lower than in the HIV-positive group. Overall, both groups show that most individuals do not suffer from hearing issues, as negative audiometry results dominate. However, the proportion of positive results is somewhat higher in the HIV-positive group (16.6%) compared to the HIV-negative group (14.1%). This suggests that HIV status may contribute to a slightly increased risk of hearing impairment, emphasizing the importance of custom-made hearing assessments and monitoring, especially for individuals with HIV.

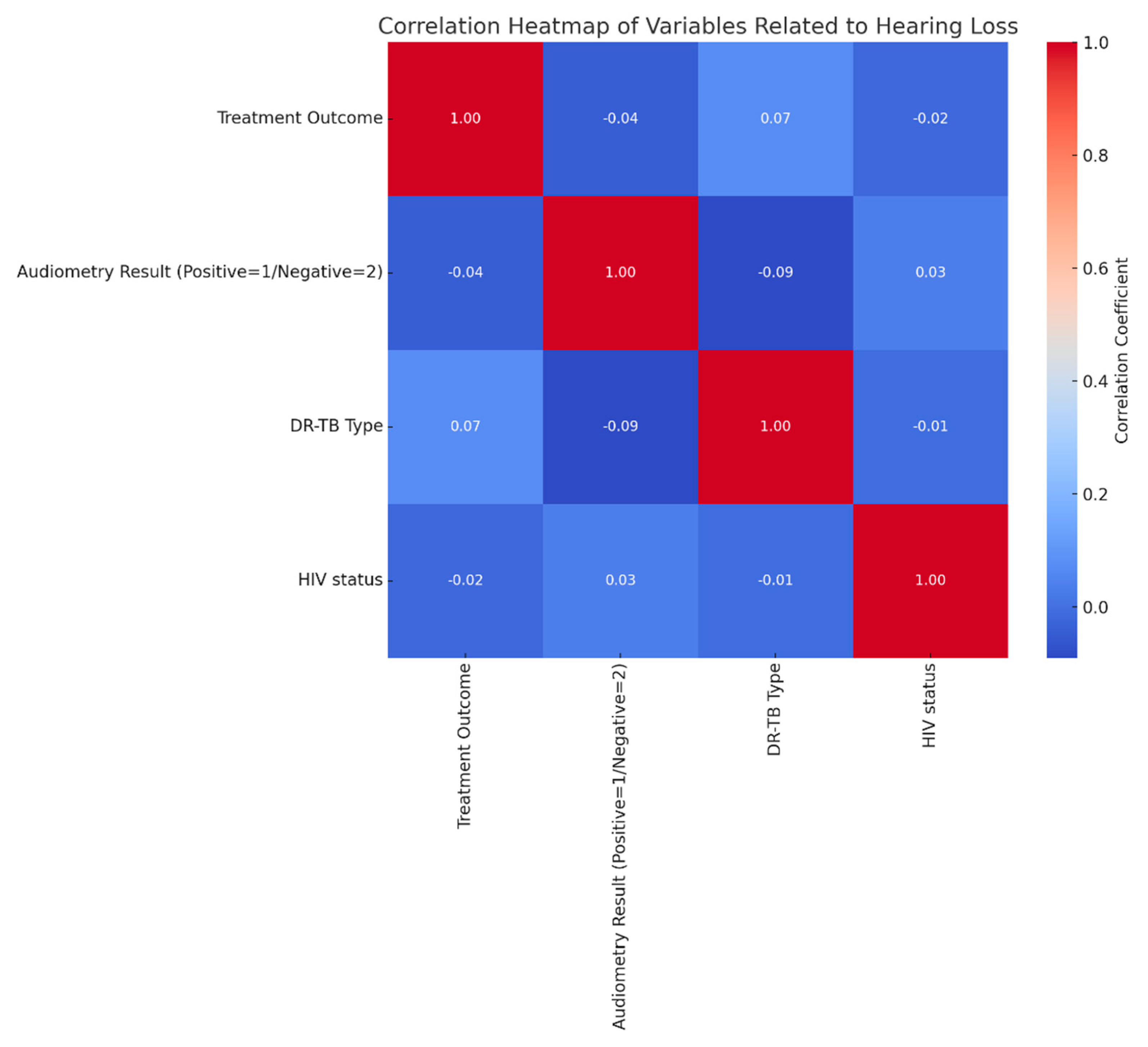

The correlation heatmap provides insight into the relationship between factors potentially related to HL, such as treatment outcome, audiometry results, DR-TB type, and HIV status. The color gradient, ranging from dark blue (indicating strong negative correlation) to dark red (strong positive correlation), helps visualize these association, with lighter shades near zero suggesting minimal or no correlation. Correlation coefficients range from -1 (perfect negative correlation) to 1 (perfect positive correlation), with values close to zero showing little to no relationship. The minimal correlation between audiometry results and other variables. Audiometry results, indicating either positive (1) or negative (2) hearing status, show weak or near-zero correlations with treatment outcome, DR-TB type, and HIV status. Specifically, the correlation with treatment outcome is minimal, suggesting that HL is not strongly associated with treatment success or failure. Similarly, DR-TB type and HIV status show almost negligible correlations with audiometry results, implying that HL does not significantly correlate with these clinical variables in this dataset. There is a slight positive correlation (r≈0.07) between treatment outcome and DR-TB type, hinting at a minor relationship between TB type and treatment success, though the connection remains weak. HIV status shows minimal correlation with treatment outcome and DR-TB type, suggesting it does not closely interact with these clinical factors in this context.

Figure 7.

Correlation of variables related to hearing loss.

Figure 7.

Correlation of variables related to hearing loss.

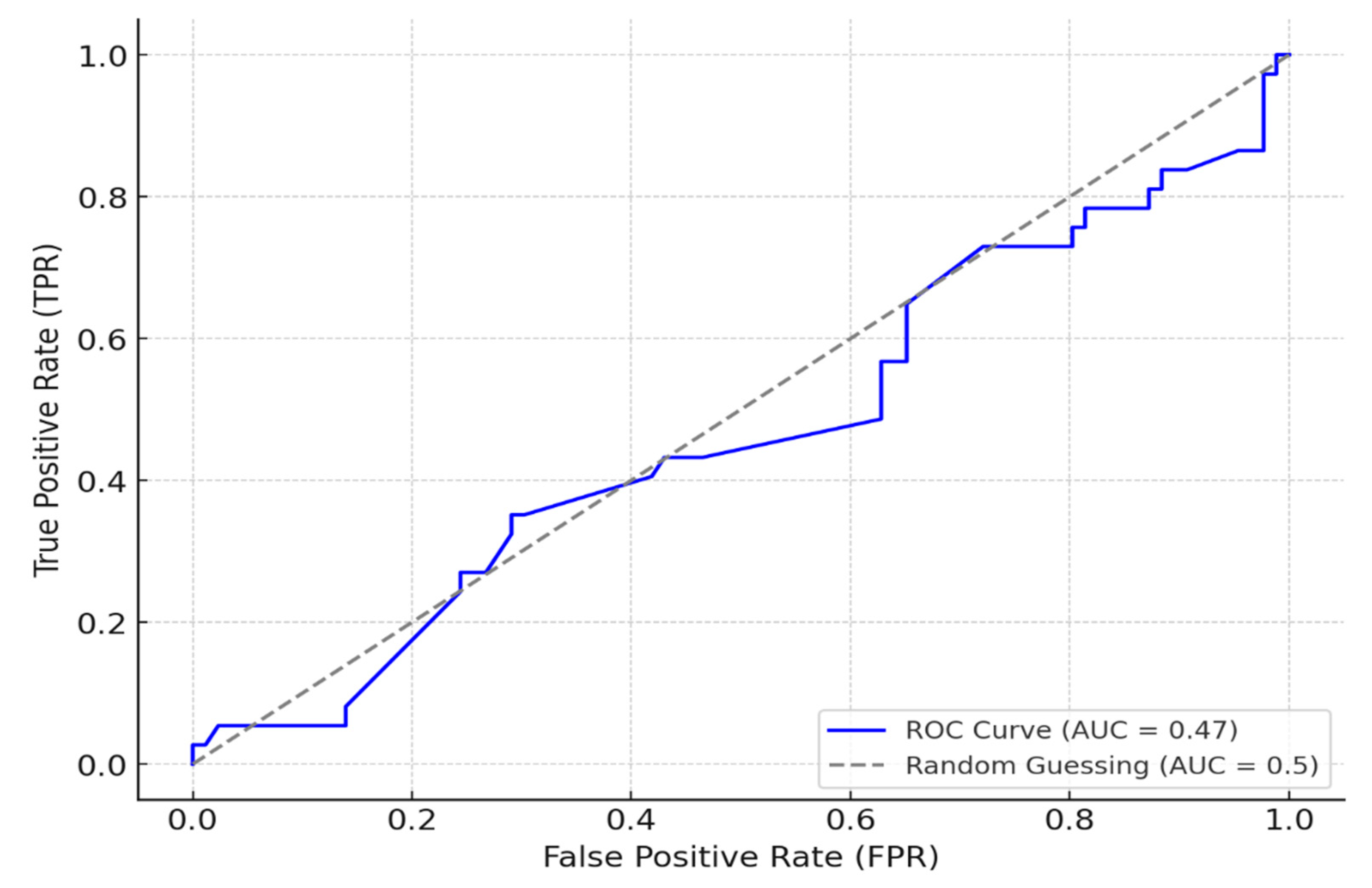

A logistic regression model was constructed to quantify the influence of key variables on hearing outcomes, including interaction terms to capture combined effects. The logistic regression model incorporating interaction terms provided insights into hearing impairment prediction and influential risk factors. The model successfully identified 80 true positive cases, accurately predicting hearing impairment, though it encountered challenges with 35 false positives and 6 false negatives. This imbalance suggests the model is sensitive in detecting hearing impairment but struggles with reliable non-case identification. Performance metrics further highlight these tendencies, with a precision of 0.70 for positive cases and a recall of 0.93, indicating strong sensitivity. However, the ROC-AUC score of 0.47 reveals moderate discriminatory power between positive and negative cases, suggesting potential room for improvement in overall classification reliability (

Figure 8). Additionally, the model revealed significant interaction terms that contribute to hearing impairment risk. Notably, interactions between social history and patient category indicated that high-risk social behaviors, especially when combined with advanced TB categories, significantly elevated the likelihood of hearing impairment. Similarly, the interaction between comorbidities (such as hypertension and liver disease) and risky social behaviors was associated with a heightened risk of impairment. The combined effect of advanced TB categories and HIV-positive status further underscored the compounded risk, demonstrating a marked increase in hearing impairment likelihood for these patients. These interactions highlight complex, multifaceted risk dynamics and the importance of accounting for both medical and social factors in predicting hearing impairment.

Exploring Variable Interactions on Hearing Impairment Risk was done using a multifaceted methodology that allowed for a comprehensive assessment of how complex interactions among lifestyle, TB status, comorbidities, HIV, and occupational exposure jointly contribute to hearing impairment risk. The methodology for this analysis involved exploring interactions among key variables to understand their combined effects on hearing impairment risk. First, we investigated the Interaction between social history and patient category, aiming to identify whether specific combinations of lifestyle behaviors and TB classifications correlate with an increased likelihood of hearing impairment. Subgroups were created based on varying social history and patient category levels, and the proportion of positive audiometry results was calculated within each subgroup. This analysis assessed whether high-risk lifestyle behaviors, such as smoking and substance use, compounded by advanced TB categories (e.g., relapse or treatment failure), are linked to greater hearing impairment. Next, we examined the effect of comorbidities by social history to determine if the presence of comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) combined with certain lifestyle factors impact hearing outcomes more significantly than either factor alone. Patients were stratified by comorbidities and social history, and positive audiometry result rates were calculated within each subgroup. This aimed to identify high-risk groups where lifestyle behaviors could exacerbate comorbidity-related hearing risks. We also explored the interaction between patient category and HIV status to understand how different TB categories and HIV status together influence hearing outcomes. Subgroups based on patient category and HIV status were analyzed to assess whether HIV-positive patients in advanced TB categories show a higher incidence of hearing impairment, highlighting a potential need for closer monitoring in these cases. Finally, we analyzed the comparison of patient work history and social history to investigate whether specific occupational exposures (e.g., healthcare or prison environments), when combined with lifestyle factors, contribute to heightened hearing impairment risk. Patients were segmented by work history and social history to calculate the prevalence of positive audiometry results within each subgroup, aiming to reveal whether occupational exposure combined with lifestyle behaviors increases hearing impairment risk.

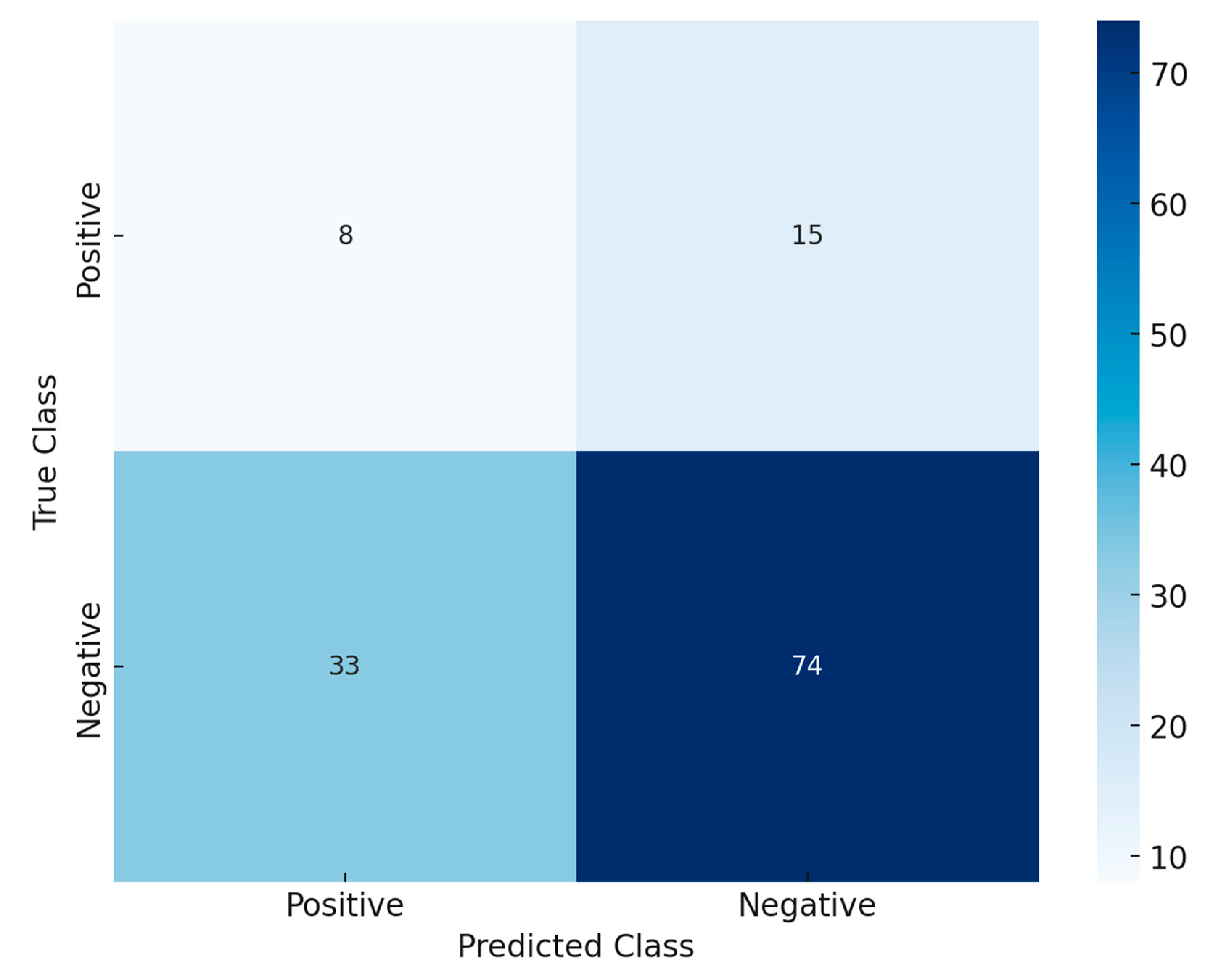

The confusion matrix,

Figure 9 provides critical insights into the performance of the Random Forest model in predicting hearing impairment. The confusion matrix is structured to represent the relationship between actual and predicted classifications. The rows indicate the true class labels, with the top row representing actual “Positive” cases (e.g., individuals with hearing impairment) and the bottom row representing actual “Negative” cases (e.g., individuals without hearing impairment). The columns represent the predicted class, where the left column corresponds to “Positive” predictions and the right column to “Negative” predictions. Key metrics derived from the matrix include True Positives (TP), which are correctly predicted positive cases (top-left cell: 8); False Positives (FP), which are negative cases incorrectly predicted as positive (bottom-left cell: 33); True Negatives (TN), which are correctly predicted negative cases (bottom-right cell: 74); and False Negatives (FN), which are positive cases incorrectly predicted as negative (top-right cell: 15).

Sensitivity and Specificity was calculated by:

Sensitivity (Recall or True Positive Rate), this measured the ability of the model to correctly identify positive cases.

Specificity (True Negative Rate), this measured the ability of the model to correctly identify negative cases.

The model correctly identifies 8 true positive cases and 74 true negative cases, reflecting its ability to correctly classify individuals with and without hearing impairment. However, the sensitivity (34.7%) indicates that the model struggles to detect true positives, as 15 cases of hearing impairment are incorrectly predicted as negative. On the other hand, the specificity (69.2%) is relatively better, showing that the model is more effective in identifying those without hearing impairment. With a significant number of false positives (33), the model tends to overpredict hearing impairment, potentially due to class imbalance or suboptimal threshold settings. While the model demonstrates moderate specificity, the low sensitivity highlights its limitations in identifying true positive cases.

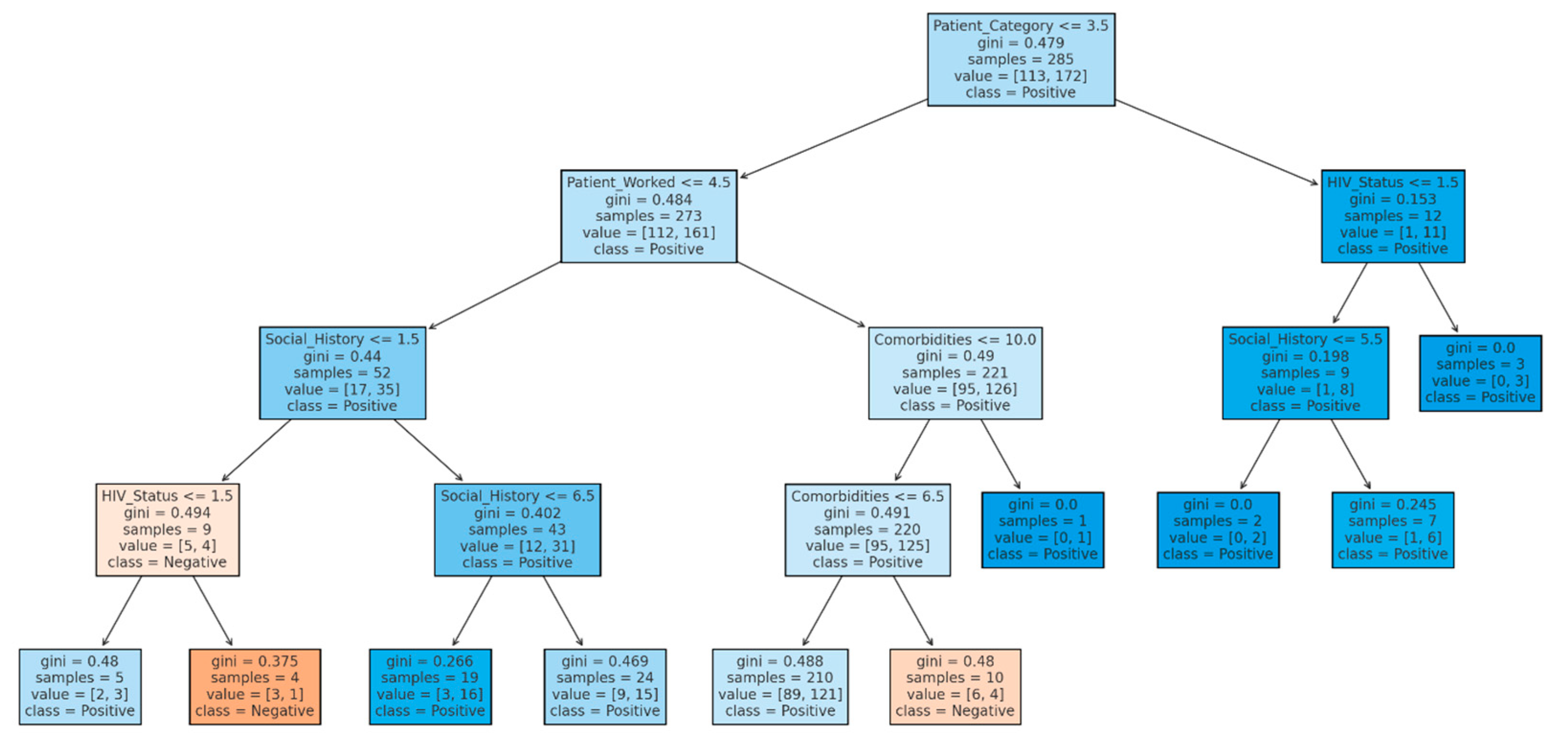

The decision tree analysis provides insight into the factors influencing audiometry outcomes by splitting the dataset into nodes that predict whether a patient’s audiometry result will be positive (indicating hearing issues) or negative (indicating no hearing issues). The decision tree analysis for audiometry result patterns highlights key factors influencing the classification of patients’ audiometry results as positive or negative for hearing impairment. The decision tree analysis begins with a split on the variable patient category at the root node, highlighting its significance in the initial classification process (

Figure 10). This primary division suggests that the Patient category is critical in determining outcomes within this dataset. Following this initial split, additional variables such as social history, HIV status, and comorbidities further refine the classification. For instance, when the Patient category is less than or equal to 3.5, the tree examines the patient’s work status as the next relevant feature, influencing the likelihood of a “positive” classification outcome. Each node includes a Gini index value throughout the tree, which measures the node’s impurity or diversity. Nodes with lower Gini values are more homogeneous, meaning they predominantly classify patients into a single category (positive or negative). In contrast, higher Gini values indicate mixed classifications within a node. Therefore, nodes with Gini values closer to zero represent strong indicators for classification, as they are almost entirely composed of one class. This progression from broader to more specific classifications, with decreasing Gini values in lower-level nodes, refines the model’s predictive accuracy by isolating homogeneous patient groups.

The Gini index, or Gini impurity, is a metric used in decision trees to quantify the “impurity” or diversity of a dataset within a node, measuring how often a randomly chosen element would be misclassified if randomly labeled according to the node’s class distribution. Lower Gini values indicate “purer” nodes, where the samples predominantly belong to a single class. For binary classifications, the Gini index is calculated using the formula:

where pi is the probability of a sample being in class iii.

For instance, a node with 80% “positive” and 20% “negative” samples has a Gini index of 0.32, reflecting moderate purity. The range of Gini values provides insight into node purity: a Gini value of 0 represents perfect purity (all samples in the node are of one class), a value around 0.5 indicates high impurity (an even class mix), and values close to 1 (rare in binary classification) indicate maximum impurity. In decision tree construction, the Gini index is essential as it helps to evaluate and select the best splits, aiming to reduce impurity and increase homogeneity in child nodes. The algorithm iteratively selects splits that minimize the Gini index, optimizing the tree structure for clearer, more certain classifications. The Gini index is widely used in decision trees, especially in CART (Classification and Regression Trees), due to its computational efficiency and effectiveness in producing interpretable trees. It provides a straightforward and powerful measure to guide the tree toward higher classification purity, ultimately enhancing predictive accuracy.

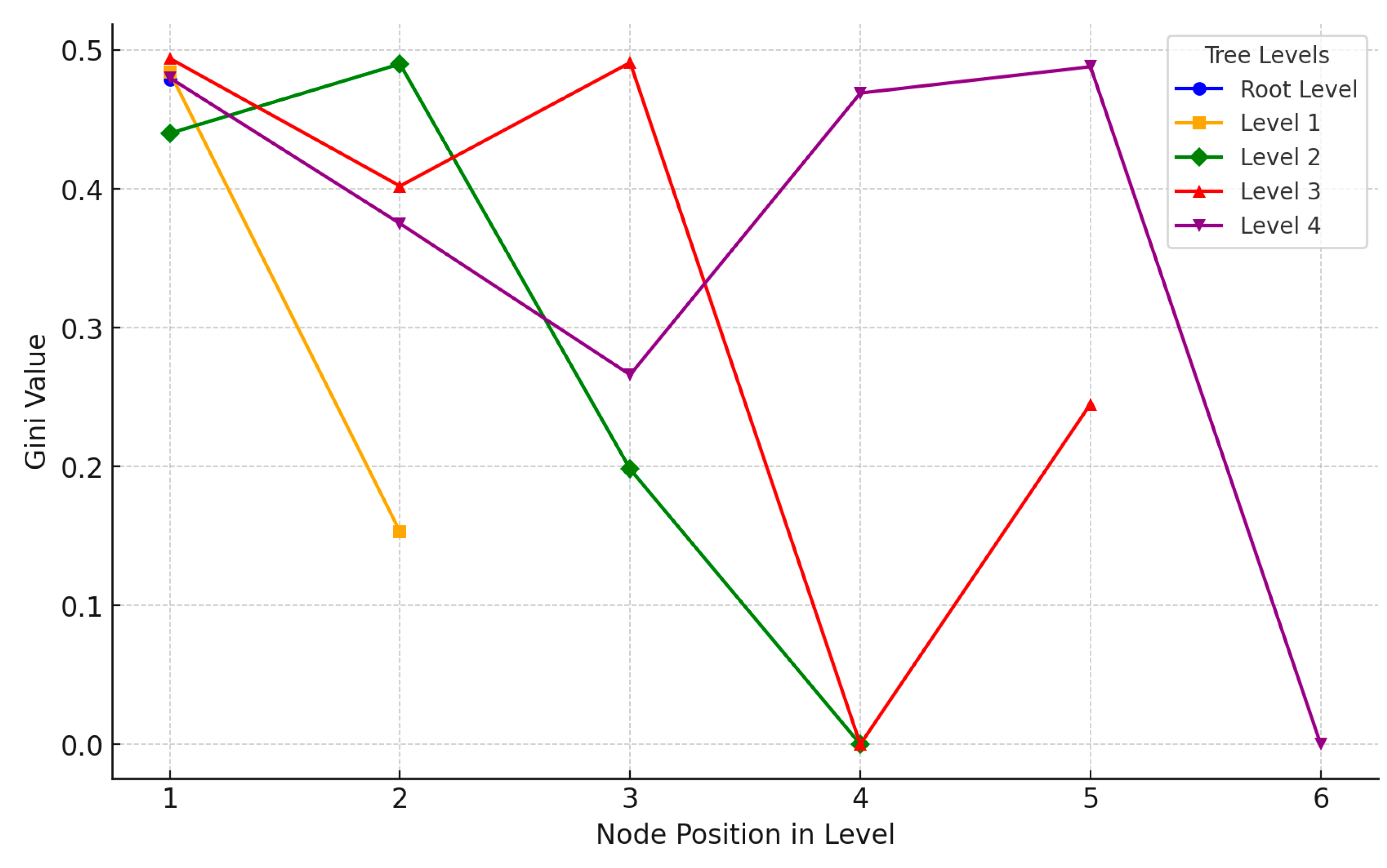

The visualization of Gini values across different levels of the decision tree illustrates the progression of classification purity at each stage (

Figure 11). At the Root Level (blue), the Gini value is around 0.479, indicating a moderately mixed classification at the outset. Moving to Level 1 (orange), there is a significant reduction in Gini for one node, reaching 0.153, which reflects a more homogeneous split along one path. Level 2 (green) shows varied Gini values, including a zero, signifying a highly pure classification in one of its paths. Mixed Gini values appear in Level 3 (red), but one node reaches zero, achieving complete homogeneity in that classification. Finally, Level 4 (purple) displays a range of Gini values from high to low, indicating diverse purity levels in the classifications at this deeper stage. This visualization highlights how the tree incrementally improves classification purity, with certain paths achieving very low Gini values, marking effective separation and more confident classification at specific nodes.

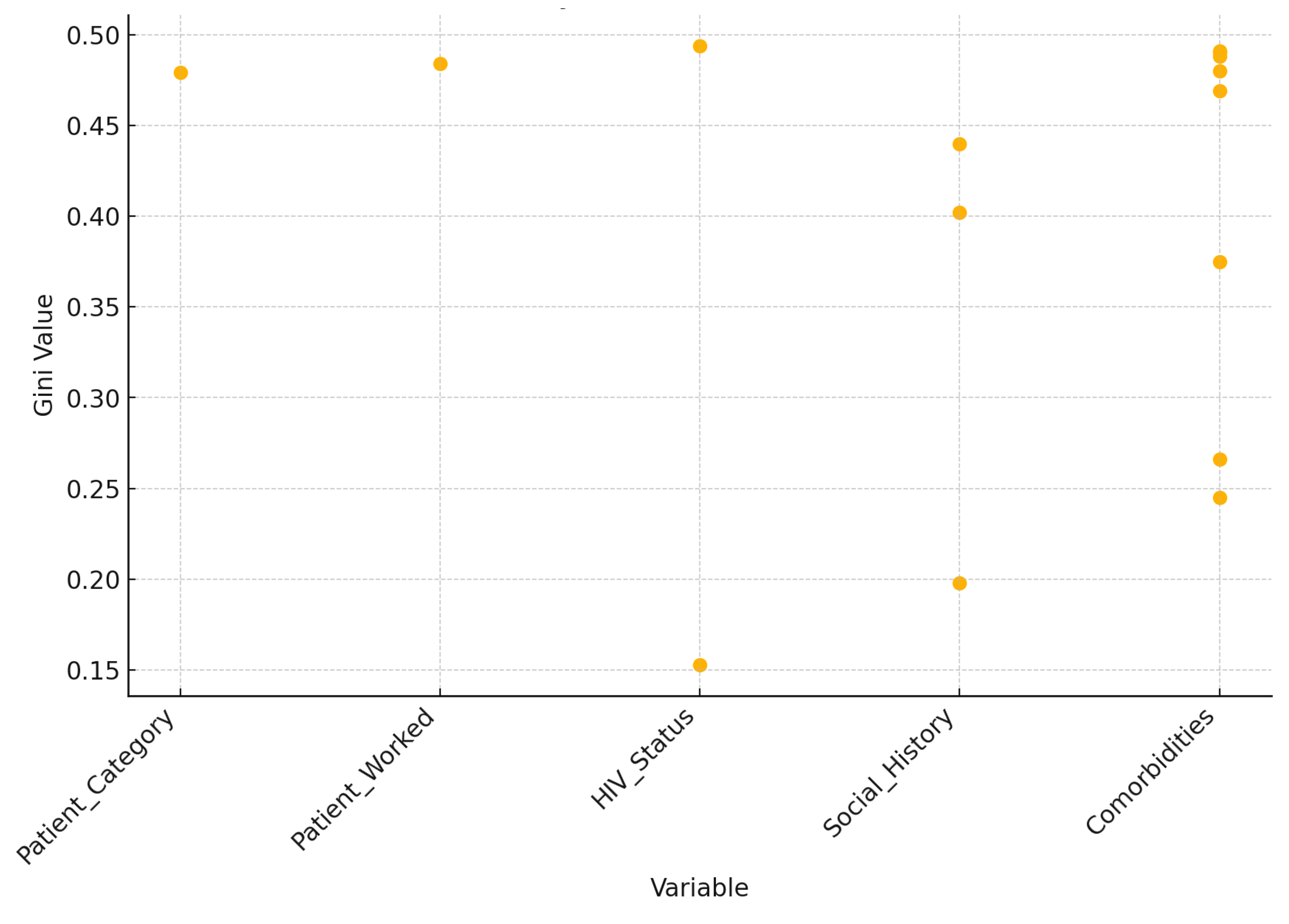

The scatter plot illustrates the Gini values associated with each variable used in the decision tree, revealing insights into their roles in classification (

Figure 12). Patient category and Patient worked exhibit relatively high Gini values (around 0.479 and 0.484, respectively), indicating a more mixed classification at nodes likely positioned higher in the tree. HIV status demonstrates a broad range of Gini values, from as low as 0.153 to as high as 0.494, signifying its importance at both early and later stages of the tree, contributing to varying degrees of classification purity. Social history and comorbidities are used extensively across the tree, with diverse Gini values that reflect their roles in refining classifications at deeper levels. Notably, certain nodes split by comorbidities achieve very low Gini values, effectively forming more homogeneous groups. This analysis underscores how each variable contributes uniquely to achieving different levels of classification purity, with some variables influencing broad initial splits and others refining classifications in lower branches.

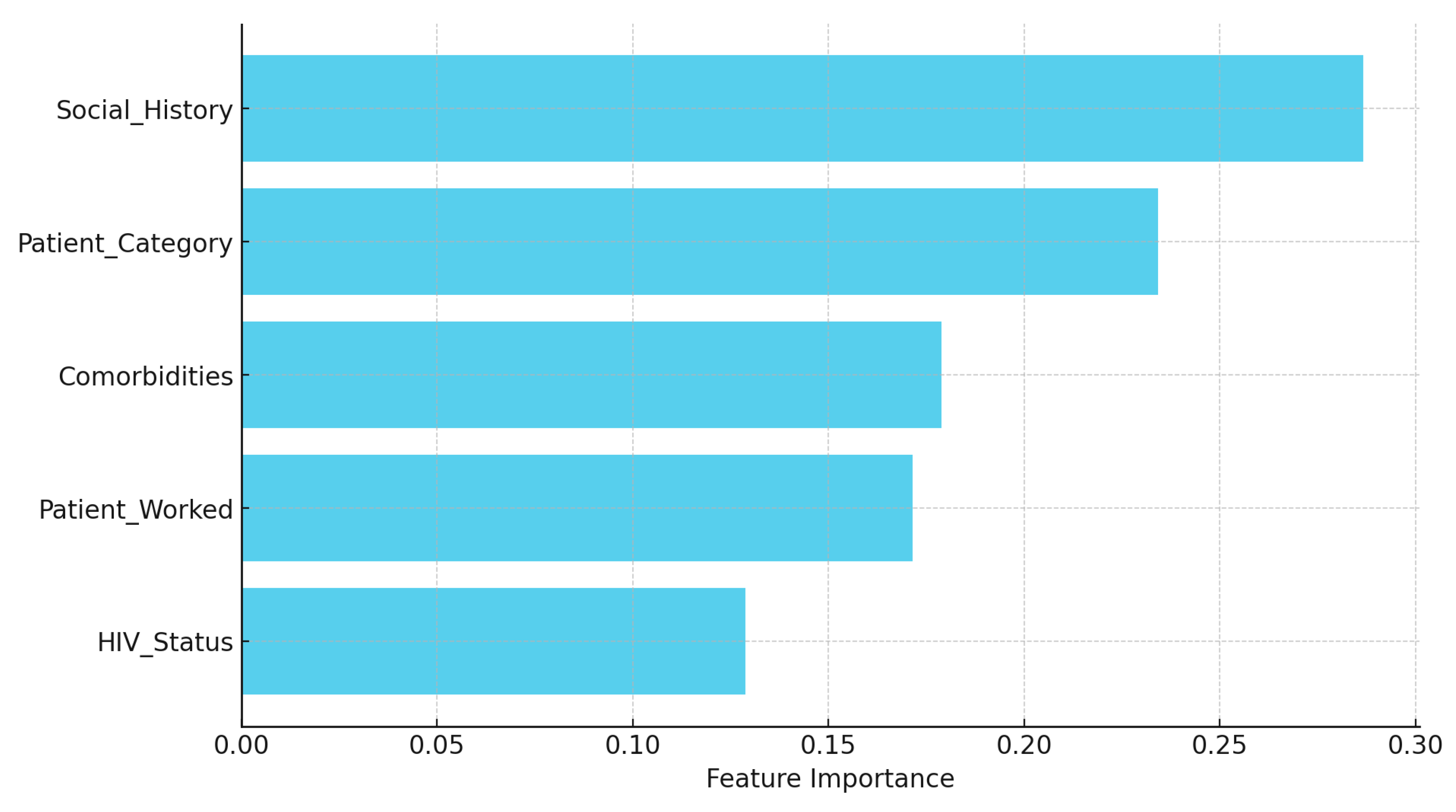

The variable importance analysis from the Random Forest model provides insights into factors contributing to hearing impairment predictions among TB patients (

Figure 13). Social history emerged as the most influential predictor (28.7%), highlighting that lifestyle behaviors, such as smoking, drinking, and substance use, play a significant role in hearing outcomes. This suggests that lifestyle choices may heavily influence hearing health, especially when compounded by other health and occupational factors. Patient category followed closely with 23.4% importance, reflecting how TB classification (e.g., new case, relapse, treatment failure) impacts hearing, likely due to variations in treatment regimens or disease severity. Comorbidities, with a 17.9% importance, emphasized that additional health issues—such as hypertension, diabetes, and liver disease—can increase hearing impairment risk, possibly due to combined treatment effects and overall health burden. Patient work history contributed 17.1% to prediction importance, indicating that occupational exposure, particularly in high-risk environments like healthcare or prison, interacts with health status to elevate hearing impairment risk. Lastly, HIV status, while having the lowest importance at 12.9%, still contributed meaningfully, suggesting its impact on hearing may be more indirect or dependent on interactions with other factors. This ranking underscore the complex interplay of lifestyle, health conditions, and occupational factors in predicting hearing outcomes for TB patients. Visualized in a bar chart, these findings highlight that lifestyle factors (social history) and TB classification (Patient category) are critical in predicting hearing outcomes, with additional health conditions (comorbidities) and occupational exposures (Patient work history) also playing significant roles. HIV status, while impactful, ranks lower, indicating its effect is less direct but nonetheless relevant. These insights reinforce the importance of considering lifestyle, TB classification, and health conditions in assessing hearing impairment risk.

4. Discussion

This study investigated HL prevalence and risk factors in patients undergoing DR-TB treatment, offering insights into age, treatment outcomes, DR-TB type, and comorbid conditions associated with audiometric outcomes in rural Eastern Cape, South Africa.

Baseline audiometric evaluations are frequently not carried out in resource-constrained nations like South Africa before ototoxic damage is expected to develop [

17,

23], which results in an underdiagnosis of pre-existing HL [

15]. Testing conducted at baseline to evaluate pre-existing comorbidities before treatment initiation showed 5.5% of participants with pre-existing HL [

2]. Aminoglycoside (AG)-induced HL was detected in about a third (37.2%) of our participants. The findings of this study is evidenced by other reports suggesting the prevalence of pre-existing loss in the DR-TB patient cohort in South Africa. The study by Hong et al. [

15] conducted in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal reported a 60% pre-existing HL before treatment, while another study conducted in the Western Cape of South Africa detected HL in 57% of patients [

24]. Patients presenting with pre-existing HL before starting DR-TB treatment are particularly vulnerable to further HL loss after using AG regimen. Hence the prevalence of pre-existing HL is a crucial factor for consideration in the South African Ototoxicity Monitoring Plans (OMPs) [

17]. The increased risk of aminoglycoside-induced HL in DR-TB patients with pre-existing HL is confirmed by the results of the current study, which indicated that patients presenting with a pre-existing HL at the time of the baseline assessment had an increase in hearing deterioration up to 8 times higher than those with no pre-existing HL hear.

There is a clear age-dependent increase in HL prevalence. Younger age groups (0-49) have predominantly negative audiometric results, indicating good hearing health, while those over 50, particularly the 70+ age group, show a dramatic rise in positive audiometry results, with HL affecting over half of this demographic. This pattern reflects age-related hearing deterioration, underscoring the need for proactive monitoring and early intervention in older DR-TB patients. The CONSTANCE study, a large cohort study conducted in France involving over 186,000 participants, found that the prevalence of HL significantly increases with age. HL rates rose from 3.4% in individuals aged 18-25 to 73.3% in those aged 71-75 [

25]. Consistent with our findings on the prevalence of HL in DR-TB patients over 50 years old, other studies support the observation that older age groups, particularly those over 50, experience a dramatic rise in hearing impairment. Age-related HL (ARHL), or presbycusis, is prevalent among older adults, with nearly one in three people between ages 65 and 74 experiencing HL, and this figure increases to nearly half for those over 75. particularly affecting over half of individuals in their 70s. ARHL is the most common sensory deficit in the elderly and typically presents as a progressive bilateral HL primarily affecting higher frequencies [

26,

27]. However, some studies emphasize variability due to genetic and socioeconomic factors such as education level and access to healthcare may mitigate or exacerbate age-related declines in auditory health, suggesting that not all older adults will experience severe hearing impairments [

28,

29]. Understanding these nuances is critical for developing targeted interventions for different age groups within DR-TB populations to enhance their overall treatment outcomes and quality of life.

The study links treatment success with better hearing outcomes. Patients who achieved “Cured” or “Treatment Completed” status had higher rates of negative audiometry results, suggesting minimal hearing impairment post-treatment. In contrast, groups with unsuccessful outcomes (e.g., “Lost to Follow-Up,” “Treatment Failed,” and “Died”) showed a higher incidence of HL, possibly due to prolonged illness, insufficient treatment, or disease complications. A study conducted on patients with ENT tuberculosis found that those who achieved a cured or treatment-completed status had significantly better hearing outcomes. Among 200 patients, those who were cured showed higher rates of normal audiometry results compared to those who experienced treatment failure. The study emphasized the importance of regular audiological assessments for patients undergoing anti-tuberculosis treatment, particularly those on ototoxic medications like aminoglycosides. This supports the notion that successful treatment correlates with better auditory health post-treatment [

20]. A different study, however, found that regardless of the outcome of treatment, a considerable percentage of MDR-TB patients receiving large doses of aminoglycosides acquired HL. The ototoxic nature of the medications used in their regimen put even patients who had effective treatment outcomes at risk for auditory damage, as 70% of patients had some form of hearing impairment [

15,

30]. These results indicate that patients who achieve clinical success may experience substantial HL, thus challenging the belief that successful treatment is always associated with better hearing outcomes. This underscores the need for balance with careful monitoring and management strategies to mitigate auditory risks while ensuring effective TB treatment.

While most HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals maintained normal hearing, the HIV-positive group showed a slightly higher rate of HL. This difference suggests a marginal increase in risk associated with HIV, emphasizing the importance of regular hearing assessments in HIV-positive DR-TB patients. According to the prospective case-control study from Cameroon on the Effect of HIV infection and highly active antiretroviral therapy on hearing function, HL is more frequent in HIV-infected patients compared with uninfected patients. The HIV-positive patients presented with otologic symptoms such as hearing loss, dizziness, tinnitus, and otalgia than HIV-negative patients, which difference was statistically significant. 27.2% of HL in the HIV-positive group, as compared to 5.6% in the HIV-negative group were reported. Compared with HIV-negative individuals, the odds of hearing loss were higher among HIV-infected HAART-naive patients, patients receiving first-line HAART, and patients receiving second-line HAART [

31]. However, in the current study, we did not report on the ART being taken by the HIV-positive participants.

The decision tree model emphasized Patient Category, Social History, and HIV Status as primary factors influencing hearing outcomes. The Gini index analysis of tree nodes revealed distinct classification purity levels, with low Gini values identifying patient subgroups with homogeneous hearing status. However, challenges in model sensitivity, particularly in predicting positive hearing outcomes, suggest a need for refined data balancing or algorithm adjustments to improve positive case prediction. The application of decision tree models and other predictive modeling techniques has proven valuable in understanding the factors influencing treatment outcomes in DR-TB. Ma et al. [

32] developed a clinical prediction model for unsuccessful treatment outcomes in patients with MDR-Pulmonary TB. It identified key factors such as no health education, advanced age, male gender, and larger lung involvement using logistic regression and decision tree methods. The model demonstrated good predictive performance, with the area under the curve of the model being 0.757, and the concordance index (C-index) was 0.75, indicating that these social and demographic factors significantly influence treatment success. Another study identified individual risk factors for TB patients’ treatment adherence using machine learning approaches, such as decision trees. It emphasized several predictive variables, such as patient age, HIV status, and socioeconomic characteristics like ownership of a medical facility. The significance of these parameters in treatment results was highlighted by the study’s conclusion that machine learning could successfully distinguish between adherent and non-adherent patients [

33]. Furthermore, Hosu et al. [

34] applied decision tree models to predict successful treatment outcomes. The study emphasized the utility of incorporating lifestyle factors and HIV status into the predictive models to enhance accuracy and provide insights into patient management strategies. The model performed well in predicting successful treatment outcomes with a high recall (92%) and a balanced F1-score (78%). While a lot of research supports the use of machine learning models, such as decision trees, to predict treatment outcomes, some studies draw attention to issues including overfitting and the requirement for a large amount of clinical data to increase model accuracy. The variation in outcomes depending on various populations implies that although decision trees can identify significant factors, their suitability may fluctuate depending on the context.